Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Alienation and Life Satisfaction: Mediation Effects of Social Identity and Hope among University Students

1 Department of Electrical and Mechanical Technology, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500208, Taiwan

2 Graduate Institute of Technology Management, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City, 40244, Taiwan

3 Center for Teacher Education, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500207, Taiwan

4 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500207, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Yao-Chung Cheng. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1907-1927. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068264

Received 24 May 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Interpersonal alienation has increasingly been recognized as a salient risk factor affecting university students’ psychological adjustment and life satisfaction. Guided by Social Identity and Self-Categorization theories, this study examines how alienation influences life satisfaction through the mediating roles of social identity and hope. Methods: This study surveyed 492 Taiwanese undergraduate students (53.7 percent female, mean age 21.08 years) from 60 universities using convenience sampling in May 2023. Data were collected through an online questionnaire distributed via faculty-managed teaching media platforms. Measures included perceived social identity, state hope, interpersonal alienation, and life satisfaction. All instruments were adapted from validated scales, translated into traditional Chinese through back-translation, and reviewed by experts to ensure content validity and cultural relevance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20 and SmartPLS 4.0. Results: Harman’s single-factor test indicated no significant common method bias. Measurement model analyses demonstrated satisfactory reliability, convergent validity, and absence of multicollinearity. All four hypothesized paths were supported: interpersonal alienation negatively predicted life satisfaction, with perceived social identity and hope serving as individual and sequential mediators. The model explained 10.5% of the variance in social identity, 25.3% in hope, and 49.6% in life satisfaction. Group comparisons revealed that male students reported significantly higher hope and life satisfaction than females, and first-year students experienced greater alienation than upper-level peers. Conclusion: This study elucidates how interpersonal alienation undermines life satisfaction among university students and highlights the protective roles of social identity and hope. Findings underscore the importance of fostering psychological resources that promote resilience and well-being. The results offer practical implications for designing educational programs that enhance students’ sense of belonging, optimism, and emotional strength. These insights contribute to a deeper theoretical understanding of the mechanisms linking alienation and life satisfaction and inform strategies to support student adaptation and flourishing in higher education.Keywords

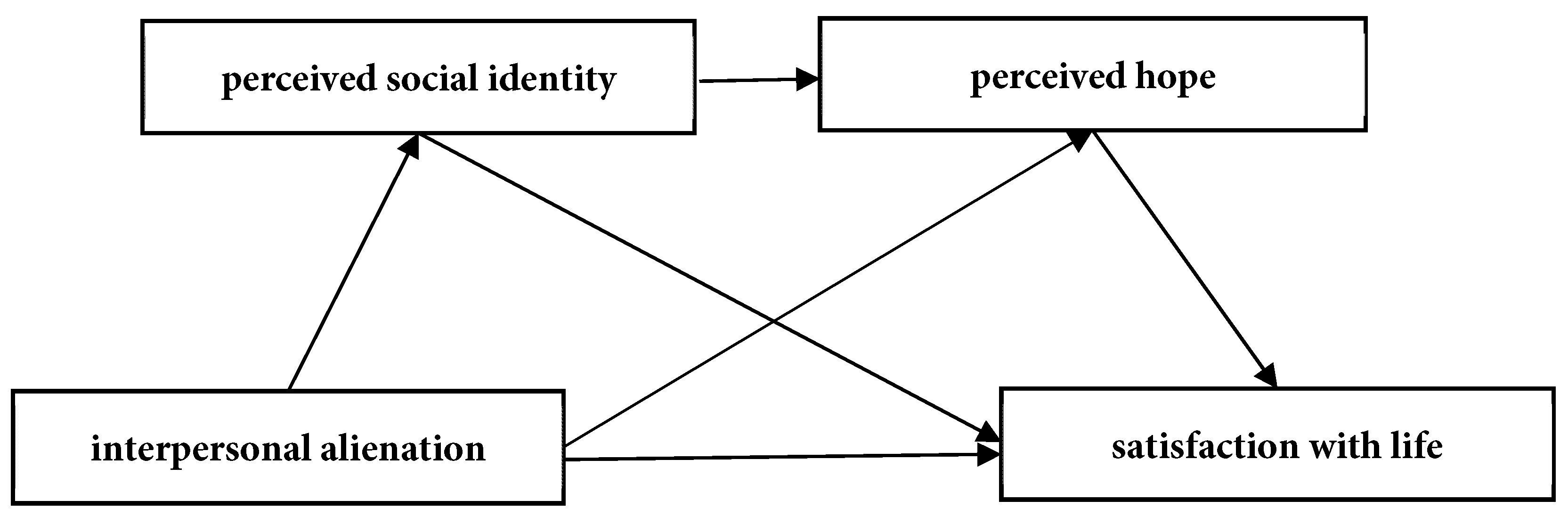

Social Identity Theory explains how group membership shapes self-perception and behavior [1]. Self-Categorization Theory further highlights how group identification dynamically influences cognition and actions [2]. These theories inform our framework linking alienation, social identity, hope, and life satisfaction. Interpersonal alienation has emerged as a serious issue for mental health and adaptation [3,4,5]. It is linked with self-perception and trust in others [6]. Among university students, alienation often stems from barriers with instructors, coursework, and peers [7], and these stressors reduce life satisfaction [8,9,10]. The COVID-19 pandemic further heightened alienation through remote learning and social distancing [5,7], with adverse effects on psychological health and life satisfaction [11,12]. These conditions highlight the importance of protective psychological resources. Recent studies emphasize social identity as a key factor explaining loneliness and alienation [13]. Isolation during online learning transitions weakened social identity, intensifying loneliness [13]. Social identity promotes connectedness and meaning [14], and interventions confirm its role in reducing loneliness and depression [15]. Perceptions of social standing and hope relate to lower alienation and higher life satisfaction [6,16]. Online social activities can enhance support and self-worth, improving life satisfaction [17]. Loneliness has also been linked to resilience and Internet addiction [18], suggesting that stronger social bonds may benefit psychological health. Despite growing evidence, debates remain about whether well-being shapes social identity formation. Following theory and prior findings, we conceptualize alienation as an antecedent that reduces social identity and life satisfaction. We therefore test direct, indirect, and sequential mediation pathways. Positive emotions are essential in building hope and life satisfaction [19]. Hope has been identified as a key link between group identification and group status [20]. Support and reduced hopelessness further buffer negative events, reinforcing hope’s role in resilience [12]. Supportive academic settings, social ties, and hope are critical for improving student well-being [21,22,23,24]. These insights suggest educators should promote belonging and future-oriented thinking [23,24]. In summary, prior work has examined alienation, social identity, hope, and life satisfaction separately, but rarely within one framework. The present study integrates these variables, tests sequential mediation (alienation → social identity → hope → life satisfaction), and provides evidence from Taiwanese university students, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Research framework model for the current study.

2 Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1 Theoretical Foundations: Social Identity, Self-Categorisation, and the Role of Interpersonal Alienation

Social Identity Theory posits that individuals derive their self-concept from personal characteristics and their membership in social groups, such as those defined by nationality, gender, or organizational affiliation [25,26,27]. This sense of group identification substantially influences self-esteem and psychological well-being, shaping attitudes and behaviors toward both in-groups and out-groups. Social comparison processes, where individuals emphasize their group’s superiority while derogating other-groups, are central mechanisms that enhance self-worth and social identity.

Building upon these principles, Self-Categorisation Theory further explains how individuals classify themselves into social categories in response to situational cues, with the salience of particular identities dynamically shaping cognition, emotion, and behavior [27,28]. Together, these theories provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the formation of self-identity within social environments and offer essential context for exploring psychological health issues among university students.

Recent research has increasingly focused on loneliness and alienation as prominent psychological concerns for university students. From the perspective of social identity theory, difficulties in integrating into social groups can intensify feelings of loneliness and alienation, with negative consequences for mental health. Conversely, stronger social identification has been shown to buffer these adverse effects [29]. Empirical studies further support this theoretical view; for example, research on Finnish university students revealed that uncertainty about future social roles and low group identification significantly heighten experiences of loneliness and alienation [30]. In African contexts, a lack of belonging and experiences of social exclusion among young university students have been linked to higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation [31]. Notably, the global COVID-19 pandemic, despite advances in digital interaction and artificial intelligence, has not replaced the psychological support derived from fundamental social interactions and identity affirmation [32].

According to Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorisation Theory, group identification is gradually internalized through interpersonal interactions and a sense of belonging [25,27,28]. However, experiences of self-alienation within these interactions may diminish motivation and capacity for group affiliation, thereby impeding social identity development [33]. Persistent exposure to exclusion or marginalization can foster self-categorisation as an outsider, which in turn lowers self-esteem and exacerbates psychological distress. This body of evidence positions interpersonal alienation as an antecedent in the pathway toward social identity construction, particularly within campus contexts. For example, feelings of separation have been shown to predict alienation and low belonging among university students [34].

In contrast, higher levels of social and psychological alienation are associated with reduced emotional stability and lower academic engagement [35]. Differences in social identity markers such as ethnicity, gender, and religion further influence interpersonal interactions and group belonging, with greater in-group similarity facilitating more positive relations [36,37]. Although some studies have suggested a bidirectional predictive relationship between social identity and interpersonal alienation, the evidence more strongly supports the antecedent role of alienation [38,39]. These findings highlight the critical importance of strengthening and diversifying social identities as protective factors for mental health and life satisfaction [40]. Interdisciplinary research also shows that open community activities such as campus art and sports can foster group identity and reduce loneliness and alienation [41]. That cross-cultural mobility and digital community participation exhibit robust bidirectional predictive relationships between identity and loneliness or alienation [38,39].

Synthesizing this literature reveals that individual characteristics and structural factors, including social identity positioning, group support, and experiences of identity mobility, shape loneliness and alienation among university students. The present study builds on these theoretical foundations by employing structural equation modeling to examine the interconnected pathways among Taiwanese undergraduates’ self-alienation, social identity, hope, and life satisfaction, thereby addressing gaps in East Asian higher education research and informing future policy and practice.

When examining the impact of social relationships on mental health, it is essential to distinguish conceptually and operationally between interpersonal alienation, loneliness, and social isolation. Interpersonal alienation is a subjective experience of detachment in interactions with others, characterized by estrangement, indifference, or loss of connection, often resulting from diminished trust, fractured identification, or role confusion [42]. In contrast, loneliness represents a subjective emotional state arising from dissatisfaction with the quality or quantity of one’s social relationships, even within a sufficient social network [43]. On the other hand, social isolation denotes an objective lack of social network, measured by indicators such as frequency of social contact, household size, or social activity participation [44]. Although these constructs can coexist, each is associated with distinct psychological outcomes. For instance, interpersonal alienation and existential isolation more strongly predict conspiracy beliefs and social distrust than loneliness does [42], and social isolation can occur without loneliness, and vice versa, underscoring the need for differentiated measurement and conceptual clarity [45].

In light of these distinctions, this study adopts the Interpersonal Alienation Scale [46], developed for Chinese adolescents and validated in university contexts, to capture subjective experiences of disconnection. This approach distinguishes interpersonal alienation from the more structural Contextual Alienation Scale [47], which emphasizes powerlessness and institutional alienation, making the former more appropriate for the present focus on interpersonal disconnection among Taiwanese students.

2.2 The Relationship between Interpersonal Alienation and Satisfaction with Life

Interpersonal alienation is increasingly recognized as a critical factor undermining life satisfaction, particularly among university students navigating rapid social and cultural transitions. Although numerous studies have examined the antecedents and consequences of alienation, psychological factors have consistently emerged as more influential than physical or environmental aspects. For example, Ahern and Norris [48] demonstrated that psychological elements are the primary drivers of interpersonal alienation in residential environments, rather than physical factors. Similarly, Chen et al. [49] identified a negative correlation between alienation and life satisfaction, highlighting the psychological roots of alienation.

A growing body of research underscores the influence of broader social changes in shaping both alienation and life satisfaction. For instance, globalization has intensified cross-cultural interactions and conflicts, exacerbating alienation through increased cultural barriers and reducing life satisfaction in multicultural contexts [3,4,5]. These findings highlight the need to consider individual psychological factors and macro-social influences when examining the link between alienation and well-being.

Hope is a crucial protective factor in the psychological mechanisms mediating this relationship. Merolla et al. [50] found that deficits in hope are significantly associated with increased conflict and weakened social ties, ultimately diminishing life satisfaction. Bonetti et al. [20] further demonstrated that hope can enhance low-status members’ life satisfaction by reinforcing in-group identification. Chang and Caino [19] argued that positive emotions nurture hope, elevating adult life satisfaction. Turan et al. [51] confirmed that the positive effect of mental health on life satisfaction is strengthened when hope acts as a mediator.

Self-perception and social interaction patterns also play significant roles in this context. Caselman and Self [6] reported that negative self-perceptions promote social avoidance, lowering life satisfaction. The detrimental impact of alienation on psychological health has been well documented: Haslam et al. [52] linked alienation with adverse psychological outcomes, and Kneipp et al. [53] identified anxiety and depression related to alienation as primary factors reducing life satisfaction, particularly among first-year university students.

These findings highlight the complex and multifaceted pathways connecting interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction. While the literature documents robust associations across diverse populations and contexts, the present study extends this inquiry by focusing on Taiwanese university students exposed to distinctive cultural and educational pressures. Integrating cross-cultural and psychological perspectives, the current research seeks to clarify how interpersonal alienation, hope, and social identity influence life satisfaction in this setting.

Hypothesis 1: There is a negative correlation between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction.

2.3 The Mediation Role of Social Identity in the Relationship between Feelings of Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

Social identity has been identified as a pivotal mechanism through which individuals mitigate the adverse effects of interpersonal alienation, especially in culturally diverse and dynamic environments. A substantial body of research demonstrates that perceived social identity is a psychological buffer, reducing feelings of estrangement arising from cultural differences and facilitating greater well-being [3,4]. For instance, Ahern and Norris [48] identified social identity as a critical factor in alleviating alienation within multicultural contexts, providing empirical support for the notion that a strong sense of group belonging fosters resilience against exclusion and marginalization.

Theoretical perspectives further highlight the role of social identity. Seeman [54] emphasized that robust social identities can substantially reduce alienation during stressful periods, underscoring the protective value of group identification against psychological strain. This function extends beyond stress to broader domains of psychological health. Recent studies indicate that social support networks, frequently grounded in shared social identities, foster altruistic behavior and trust, which are essential for sustaining life satisfaction [24,55].

The modern complexity of this relationship is further illustrated through the interplay between online behaviors, self-evaluation, and social identity. Qian et al. [17] showed that online social engagement can positively influence life satisfaction by enhancing perceived social support and core self-evaluation, highlighting the evolving nature of social identity in digital contexts. In contrast, Yuan et al. [56] associated lower self-esteem with increased loneliness and social avoidance, underscoring the protective role of social identity for psychological well-being. Additional evidence suggests that individuals with higher levels of hope and self-esteem are more likely to form positive interpersonal connections, leading to increased life satisfaction [57]. Conversely, diminished hope correlates with everyday conflict, relational discord, and weakened social bonds, intensifying alienation [50].

Educational environments represent a particularly salient context for observing these effects. Alienation within schools and universities, evident through low student engagement, poor well-being, destructive behaviors, and reduced academic performance, has eroded life satisfaction [58,59]. Caselman and Self [6] further highlighted the centrality of self-perception and interpersonal trust in shaping social interactions and subjective well-being. Building on this, Snyder et al. [60] and Engeström and Sannino [61] emphasized overcoming alienation through active social participation and cultivating perceived social identity, identifying these strategies as effective means for enhancing students’ life satisfaction.

These findings indicate that social identity functions not merely as a static sense of group belonging but as a dynamic and multifaceted mediator actively shaping the relationship between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction. By examining this mediation mechanism in Taiwanese university students, the present study seeks to deepen the understanding of how social identity may be leveraged to support psychological health and resilience in increasingly complex social contexts.

Hypothesis 2: Perceived social identity mediates the relationship between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction.

2.4 The Mediation Role of Perceived Hope in the Relationship between Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

Perceived hope is increasingly recognized as a central psychological resource that can buffer individuals against the adverse effects of alienation and promote life satisfaction. Recent research underscores the importance of social support systems, particularly those based on community-oriented moral identity, in reducing feelings of alienation and fostering perceived hope through peer recognition and validation [24]. This highlights the importance of social environments that actively nurture hope to address social disconnection.

At the interpersonal level, Afridi et al. [55] demonstrated that interpersonal trust is closely linked to altruistic behaviors, suggesting that supportive social interactions mitigate alienation and bolster perceived hope. These findings suggest that hope is not simply an individual trait but co-constructed through reciprocal relationships and trust within social networks.

Within educational settings, the mediating effect of hope becomes particularly pronounced. Stephanou and Athanasiadou [62] demonstrated that teachers who exhibit high hope tend to enhance students’ interpersonal relationships, psychological resilience, and social engagement. Furthermore, Liu et al. [12] found that perceived social support and lower levels of hopelessness mediate the impact of adverse life events on self-identity formation, emphasizing hope’s critical role in psychological adjustment.

Emotional intelligence is another attribute closely associated with hope. Zhao et al. [11] Higher emotional intelligence enhances students’ interpersonal competence and reduces anxiety, directly improving life satisfaction and highlighting hope’s central role in psychological well-being.

Empirical evidence also supports hope’s role in mitigating academic and social stressors. For example, Stephanou and Athanasiadou [62] showed that perceived hope can reduce academic stress, increase learning motivation, and promote positive social interactions. Additionally, Barber et al. [63] and Skinner et al. [64] emphasized that hope substantially improves life satisfaction by fostering feelings of success and belonging. Ji et al. [23] provided further support by showing that individuals with higher levels of hope are more likely to adopt proactive coping strategies, receive greater social support, and ultimately experience increased life satisfaction.

Collectively, these findings illustrate that perceived hope mediates the adverse effects of interpersonal alienation and serves as a dynamic resource for adaptive coping, psychological resilience, and fulfillment in academic and social domains. Investigating this mediating pathway among Taiwanese university students, the current study extends the literature by highlighting hope as a critical mechanism for promoting life satisfaction amid alienation.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived hope mediates the relationship between interpersonal alienation and satisfaction with life.

2.5 The Sequential Mediation Role of Social Identity and Perceived Hope in the Relationship between Feelings of Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

A more complete understanding of the relationship between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction can be achieved by considering the sequential mediating roles of perceived social identity and hope. Social identity is a foundation for psychological safety and social connectedness, enabling individuals to feel part of a larger collective, thus fostering positive emotions, reducing loneliness, and mitigating interpersonal alienation [7,8,16,49,52]. Developing a strong group identity provides greater belonging and psychological resources that help buffer against stress and isolation.

Such positive social connections foster higher expectations for the future and greater motivation to engage actively in social environments [6]. Empathetic interactions and peer validation are also critical, fulfilling emotional needs and significantly enhancing life satisfaction [65]. Within educational contexts, strong student–teacher–peer relationships are essential for improving academic achievement, psychological well-being, and hope, especially when students encounter academic and developmental challenges [66,67,68,69].

Enhancing social support through positive relationships promotes altruistic behaviors, reinforces a sense of group moral identity, and fosters reciprocity and mutual recognition within the community [24]. This interplay between social identity and social support significantly strengthens perceived hope, as students benefit from positive peer acknowledgment and robust community support [23].

Recent studies have clarified the interconnected roles of these mediators. For example, Pei and Zaki [21] highlighted the essential role of supportive relationships in promoting mental health and happiness, cautioning that young adults underestimating their peers’ empathy may withdraw from meaningful interactions, thereby exacerbating alienation. Similarly, Hou et al. [22] found that a strong sense of meaning in life reduces depression through a sequential process: first, by decreasing interpersonal alienation, and subsequently, by increasing life satisfaction, thus illustrating the joint influence of social identity and hope.

Building upon the evidence for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, perceived social identity plays a primary role in reducing interpersonal alienation and enhancing psychological health while facilitating the development of perceived hope. Hope, as a representation of positive expectations for the future, not only directly improves life satisfaction but also serves as a critical buffer against the adverse effects of alienation [6,61,62,64]. The proposed model, therefore, conceptualizes the pathway from interpersonal alienation to life satisfaction as a sequential process in which social identity and hope function as key psychological mediators.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived social identity and perceived hope sequentially mediate the relationship between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction.

3.1 Participants and Procedures

The participants in this study were exclusively undergraduate students holding Taiwanese citizenship and enrolled in 126 universities across Taiwan in 2023; international students were not included in the sample. The study specifically targeted domestic students to ensure cultural consistency and class-based identity relevance in Taiwanese higher education. Any implications of this sampling criterion for the generalizability of the findings are discussed in the Limitations section.

Sample size estimation was conducted during the research planning phase to minimize Type I and Type II errors [70]. Using G*Power 3.1.9.6 and parameters including four latent variables, eighteen observed variables, a significance level of 0.05, power of 0.80, and an effect size of 0.10 [71], the minimum required sample size was calculated as 125 participants. Data collection took place in May 2023 via convenience sampling, a common approach in academic research with specific populations, characterized by voluntary participation and high accessibility [72,73]. The online survey was distributed through social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and LINE groups managed by university faculty and digital education platforms.

This research was conducted according to the ethical standards of institutional and national research committees, the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, or comparable ethical standards. Before participating, all respondents were required to read and electronically sign an informed consent form, which detailed the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, confidentiality measures, and data withdrawal options. All survey items were mandatory, with built-in validation to ensure data completeness and accuracy. A rigorous data screening process excluded 32 invalid responses (e.g., duplicates, patterned answers), resulting in a final valid sample of 492 undergraduate students from 60 universities. This sample size adhered to recommendations by Gorsuch [74], including a minimum of 100 valid cases.

The participants included 228 males (46.3%) and 264 females (53.7%); 84 freshmen (17.1%), 104 sophomores (21.1%), 138 juniors (28.0%), and 166 seniors (33.7%). Study fields were divided into natural sciences and medicine with 83 participants (16.9%), humanities and social sciences with 191 participants (38.8%), and other fields with 218 participants (44.3%). The age range of participants was 18 to 26 years, with an average age of 21.08 years.

The questionnaire was adapted from instruments published in international academic journals. All scales were formally translated and back-translated into traditional Chinese by bilingual professors, following a standardized back-translation protocol [75]. Subsequently, five subject-matter experts reviewed and revised the translations to ensure content equivalence, cultural appropriateness, and clarity. This translation process aligns with best practices in cross-cultural research. Table 1 shows all items for the primary constructs measured in this study.

3.2.1 Perceived Social Identity Scale

This study operationalizes perceived social identity as class identity, given its contextual salience in Taiwanese higher education. This operationalization is grounded in evidence showing that social class plays a central role in shaping students’ educational experiences and peer interactions within Taiwan’s higher education system. The class-based grouping of students reflects broader social structures and functions as a key site of educational inequality and socialization. Research has shown that despite the massification of higher education, social class continues to influence access to quality education and institutional resources, highlighting class as a meaningful and salient dimension of student identity in university contexts [76]. Furthermore, Li [77] found that students’ perceptions of their school experiences are shaped by their family’s socioeconomic background, affecting peer relationships and personal identity formation, reinforcing the relevance of class identity as an operative and observable form of social identity in university life. The scale, revised by Wang et al. [78], includes three items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores reflect stronger perceived class identity.

“Perceived social identity” in this research refers specifically to class identity, consistent with the class-centered group organization in Taiwanese universities. The study’s limitations further discuss this operationalization.

Table 1: Measure models for measures (N = 492).

| Scale | Item No. | Item | FL | VIF | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Alienation Scale [46] | IA1 | I feel very lonely. | 0.887 | 2.605 | 0.868 | 0.909 | 0.715 |

| IA2 | I often feel left out of things that others are doing. | 0.886 | 2.394 | ||||

| IA3 | I feel that my family is not as close to me as I would like. | 0.711 | 1.578 | ||||

| IA4 | I often feel alone when I am with other people. | 0.885 | 2.463 | ||||

| Perceived Social Identity Scale [78] | SI1 | My position as a member of my class is very important to me. | 0.843 | 1.727 | 0.821 | 0.893 | 0.736 |

| SI2 | I am the type of person who likes to engage with my class. | 0.876 | 2.013 | ||||

| SI3 | Class activities play an important part in my life. | 0.855 | 1.845 | ||||

| The State Hope Scale [79] | SH1 | If I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to escape it. | 0.774 | 2.071 | 0.902 | 0.925 | 0.672 |

| SH2 | At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals. | 0.838 | 2.761 | ||||

| SH3 | There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now. | 0.812 | 2.304 | ||||

| SH4 | Right now, I see myself as being pretty successful. | 0.784 | 1.742 | ||||

| SH5 | I can think of many ways to reach my current goals. | 0.879 | 3.084 | ||||

| SH6 | At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself. | 0.827 | 2.766 | ||||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale [80] | SL1 | In most ways, my life is close to my ideal. | 0.865 | 2.479 | 0.897 | 0.924 | 0.710 |

| SL2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | 0.792 | 2.065 | ||||

| SL3 | I am satisfied with my life. | 0.910 | 3.586 | ||||

| SL4 | So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. | 0.860 | 2.567 | ||||

| SL5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | 0.780 | 1.899 |

The State Hope Scale, revised by Snyder et al. [79], measures perceived hope and consists of six items rated on an 8-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 8 = strongly agree). Higher total scores indicate greater hopefulness.

3.2.3 Interpersonal Alienation Scale

The Interpersonal Alienation subscale of the Adolescent Alienation Scale, developed by Yang et al. [46], was employed to assess subjective feelings of interpersonal alienation. This scale contains four items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores denoting greater alienation. The Chinese version has demonstrated good reliability and validity in local student populations.

3.2.4 Satisfaction with Life Scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale [80], revised for Chinese-speaking university students, includes five items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores reflect higher life satisfaction.

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were computed using SPSS 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to describe the sample’s demographic characteristics. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships among research variables. Differences in categorical variables (e.g., gender, academic year) were assessed using independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA.

Standard method bias was assessed via Harman’s single-factor test following Podsakoff et al. [81]. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was conducted using SmartPLS 4.0, chosen for its suitability for prediction-oriented research [82]. PLS-SEM analyses followed a two-step approach: (1) measurement model assessment, including reliability (Cronbach’s α), convergent validity (average variance extracted), and multicollinearity diagnostics using variance inflation factor (VIF); and (2) structural model evaluation for hypothesis testing and predictive validity. In PLS-SEM, VIF is primarily used to check for multicollinearity and ensure construct independence within the model.

4.1 Assessment of the Extent of Common Method Variance

Harman’s single-factor test used unrotated exploratory factor analysis to assess potential standard method bias. Four factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted. The first factor accounted for 42.62% of the total variance, which is below the recommended threshold of 50% [81]. This finding suggests that common method bias was not a significant concern in this study [83].

Model testing was conducted in three steps. First, item reliability was examined by maintaining a threshold of 0.70 for factor loadings [84]. Second, convergent validity was assessed by analyzing the average variance extracted (AVE), with a recommended threshold of 0.50 [85]. Third, internal consistency reliability was evaluated to ensure that the composite reliability (CR) scores exceeded 0.70 [84,85]. Based on these criteria, Table 1 presents the results of the measurement model.

Additionally, each item’s VIF was calculated to assess multicollinearity. VIF measures the degree to which an indicator is explained by other indicators within the same construct, with values greater than 5 indicating potential collinearity issues [82,86]. In the context of PLS-SEM, low VIF values suggest that the measurement items do not overlap excessively in their explanation of the latent variable, thereby supporting the discriminant validity of the scale. In this study, all item VIF values were below 5, indicating the absence of problematic collinearity in the measurement model.

4.3 Structural Model Fit Indices

Table 2 shows the overall fit indices of the structural equation model. The listed indices are Chi-square, degrees of freedom (df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to established criteria, an RMSEA value less than 0.08 [87,88], a CFI greater than 0.90 [87,88], and an SRMR below 0.08 [87] are generally regarded as indicative of an acceptable model fit. For the GFI, a value above 0.90 is commonly cited as the threshold for acceptable fit [87,88,89]; however, recent literature suggests that GFI should be interpreted cautiously due to its sensitivity to sample size and model complexity. In the present analysis, the estimated model achieved an RMSEA of 0.075, a CFI of 0.935, a GFI of 0.904, and an SRMR of 0.054. All reported indices fall within the recommended thresholds, indicating satisfactory fit of the structural equation model and supporting the model’s suitability for subsequent structural analysis, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Model Fit Indices (N = 492).

| Fit Index | Estimated Model | Recommended Criteria | Scholarly References |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 483.374 | - | - |

| df | 129 | - | - |

| p-value | < 0.001 | - | - |

| χ2/df | 3.747 | - | - |

| RMSEA | 0.075 | <0.080 | Hu & Bentler, 1999 [87]; Kline, 2023 [89] |

| CFI | 0.935 | >0.900 | Hu & Bentler, 1999 [87]; Kline, 2023 [89] |

| GFI | 0.904 | >0.900 | Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993 [89] |

| SRMR | 0.054 | <0.080 | Hu & Bentler, 1999 [87] |

Discriminant validity was tested using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) approach [90]. According to the guidelines, an HTMT value above 0.85 may indicate inadequate discriminant validity [88]. As shown in Table 3, all HTMT values were below this threshold, indicating sufficient discriminant validity among the constructs.

Table 3: Discriminant validity Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) of correlations (N = 492).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. interpersonal alienation | ||||

| 2. perceived hope | 0.312 | |||

| 3. satisfaction with life | 0.503 | 0.664 | ||

| 4. social identity | 0.366 | 0.545 | 0.596 |

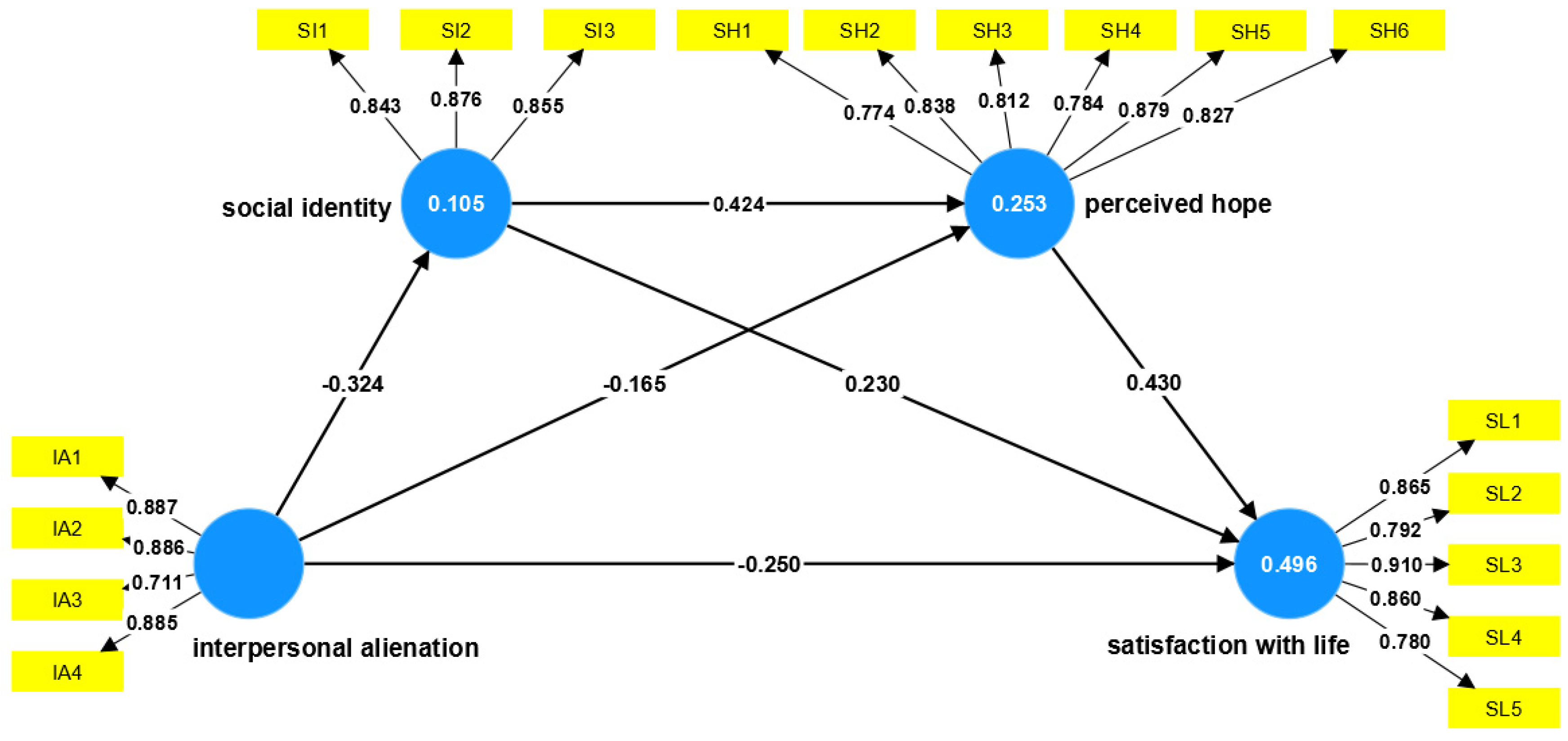

Structural model analysis and hypothesis testing were performed using SmartPLS 4.0. Path coefficients and their statistical significance were evaluated using the bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples [91]. As shown in Fig. 2 and detailed in Table 4, the results provide empirical support for all four hypothesized relationships. Specifically, interpersonal alienation was significantly and negatively associated with life satisfaction (β = −0.454, t = 11.525, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 1; perceived social identity mediated this relationship (β = −0.074, t = 4.237, p < 0.001) [92], confirming Hypothesis 2; perceived hope also mediated the relationship (β = −0.071, t = 3.397, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 3; and social identity and hope sequentially mediated the effect (β = −0.059, t = 5.163, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2: Structural model (N = 492). Note: values on the arrows from latent variables to indicators represent standardized factor loadings. Values on the paths among latent variables indicate standardized path coefficients. Numbers inside the circles show each endogenous construct’s explained variance (R2).

Table 4: Path coefficients and significances for the hypothesis (N = 492).

| Hypothesis | β | SE | t | p | CIs | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 97.50% | ||||||

| Hypothesis 1: interpersonal alienation → satisfaction with life | −0.454 | 0.039 | 11.525 | <0.001 | −0.531 | −0.375 | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2: interpersonal alienation → social identity → satisfaction with life | −0.074 | 0.018 | 4.237 | <0.001 | −0.112 | −0.043 | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3: interpersonal alienation → perceived hope → satisfaction with life | −0.071 | 0.021 | 3.397 | 0.001 | −0.115 | −0.032 | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4: interpersonal alienation → social identity → perceived hope → satisfaction with life | −0.059 | 0.011 | 5.163 | <0.001 | −0.059 | −0.039 | Supported |

4.6 Explanatory Power of the Model

Fig. 2 shows the R2 values calculated via the PLS algorithm, which were used to examine the model’s explanatory power. All R2 values exceeded the threshold of 0.10 [93]. Specifically, R2 was 0.105 for perceived social identity, 0.253 for perceived hope, and 0.496 for satisfaction with life, indicating that the model explained a substantial portion of variance in the dependent variables.

4.7 Predictive Power of the Model

Based on the recommendations of Shmueli et al. [94], this study evaluated predictive power using PLS-Predict. The Q2 value for “satisfaction with life” was 0.201, indicating good predictive relevance. As shown in Table 5, all item-level Q2 values are greater than zero, and RMSE values for the PLS model are consistently lower than those of the linear model, demonstrating strong predictive performance. RMSE is generally preferred for accuracy, with mean absolute error (MAE) as a complement if errors are skewed. In this study, RMSE values for all PLS items were lower than for the linear model, confirming robust predictive power.

Table 5: PLS-predict result.

| Item | PLS | LM | PLS-LM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | Q2 Predict | |

| SL1 | 1.246 | 1.010 | 1.247 | 1.014 | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.174 |

| SL2 | 1.271 | 1.017 | 1.276 | 1.020 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.093 |

| SL3 | 1.318 | 1.068 | 1.327 | 1.072 | −0.009 | −0.004 | 0.191 |

| SL4 | 1.525 | 1.229 | 1.532 | 1.233 | −0.007 | −0.004 | 0.136 |

| SL5 | 1.744 | 1.448 | 1.753 | 1.453 | −0.009 | −0.005 | 0.106 |

4.8 Comparison of Differences in Gender, Grade, and Major on the Measures

As shown in Table 6, significant differences were observed in perceived hope and life satisfaction by gender: males reported higher hope (Mean = 5.623, SD = 1.353; t = 3.180, p < 0.01) and life satisfaction (Mean = 4.763, SD = 1.286; t = 2.290, p < 0.01) than females. Grade level affected interpersonal alienation (F = 4.009, p < 0.01), with first-year students reporting higher alienation than other years, indicating decreased alienation over time. No significant differences were found in social identity, hope, or life satisfaction across grades, suggesting these variables remain stable throughout university.

Table 6: Differences in measure scores among the research sample based on demographic variables (N = 492).

| Demographic Variables | N | Interpersonal Alienation Scale | Perceived Social Identity Scale | The State Hope Scale | Satisfaction with Life Scale | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| 1. Male | 228 | 3.089 | 1.487 | 1.343 | 3.339 | 1.080 | 0.916 | 5.623 | 1.353 | 3.180** | 4.736 | 1.286 | 2.290** |

| 2. Female | 264 | 3.906 | 1.533 | 3.251 | 1.039 | 5.237 | 1.329 | 4.469 | 1.277 | ||||

| Grade | |||||||||||||

| 1. Freshman | 84 | 3.354 | 1.470 | 4.009** 1 > 3 | 3.174 | 0.964 | 0.865 | 5.134 | 1.357 | 1.821 | 4.273 | 1.303 | 2.212 |

| 2. Sophomore | 104 | 3.163 | 1.493 | 3.224 | 1.069 | 5.365 | 1.245 | 4.594 | 1.194 | ||||

| 3. Junior Year | 138 | 2.688 | 1.534 | 3.384 | 1.029 | 5.478 | 1.345 | 4.687 | 1.231 | ||||

| 4. Senior Year | 166 | 2.951 | 1.490 | 3.317 | 1.119 | 5.539 | 1.410 | 4.675 | 1.363 | ||||

| Major | |||||||||||||

| 1. A | 83 | 2.919 | 1.419 | 1.558 | 3.433 | 0.979 | 1.180 | 5.473 | 1.179 | 0.766 | 4.547 | 1.209 | 0.240 |

| 2. B | 191 | 2.870 | 1.551 | 3.305 | 1.111 | 5.487 | 1.430 | 4.642 | 1.353 | ||||

| 3. C | 218 | 3.125 | 1.510 | 3.226 | 1.038 | 5.331 | 1.346 | 4.560 | 1.260 | ||||

This study aimed to elucidate the sequential mediation effects of social identity and hope in the link between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction among university students. By investigating these associations, the research clarified how psychological and social factors shape student well-being. While this study establishes significant associations among variables, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences.

5.1 The Association between Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

Findings show a significant negative correlation between interpersonal alienation and satisfaction with life, supporting Hypothesis 1. This aligns with social support theory; for example, Ahern and Norris [48] noted that limited social support is closely related to lower life satisfaction. Engeström and Sannino [61] further identified that interpersonal alienation is associated with increased internal conflict and reduced motivation to participate in social activities, which is linked with diminished happiness. Caselman and Self [6] found that negative self-image and avoidance of social interactions are correlated with stronger feelings of alienation and lower quality of life. Cross-cultural research by Ma and Zhan [5] and Klomegah [3] also reported that reduced interpersonal contact is associated with heightened alienation in diverse environments. Recent work by Sun et al. [24] emphasized that perceived social support is related to higher altruism and a stronger sense of group belonging. Zhao et al. [11] demonstrated that life satisfaction is closely related to students’ psychological adjustment, particularly under stress. Pei and Zaki [21] observed that a lack of meaningful social connections is linked with intensified emotional distress and poorer mental health among young people. Similarly, Ji et al. [23] indicated that higher hope is correlated with greater proactive coping and life satisfaction. These results suggest that strengthening social ties and fostering connectedness may reduce feelings of alienation and improve well-being.

5.2 The Mediating Role of Social Identity in the Association between Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

Results indicate that perceived social identity mediates the association between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction, confirming Hypothesis 2. Prior studies highlight the importance of social identity for psychological health and adaptation [52]. Ahern and Norris [48] emphasized that group identity is linked with psychological comfort and satisfaction, particularly for those experiencing isolation. Ma and Zhan [5], Klomegah [3], and Pepanyan et al. [4] discussed how social identity alleviates discomfort in diverse settings. Qian et al. [17] found that the benefits of online social interaction on well-being are significantly related to perceived support and social identity. Yuan et al. [56] reported that low self-esteem and loneliness are associated with social avoidance and decreased happiness, underscoring the protective role of social identity. Yu [95] and Ma and Miller [96] suggested that reinforcing community identity enhances self-worth and satisfaction. These studies underscore the value of enhancing perceived social identity to support student well-being.

5.3 The Mediating Role of Perceived Hope in the Association between Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

The data demonstrate a significant mediating role of perceived hope, supporting Hypothesis 3. Previous research shows that alienation negatively correlates with life satisfaction [96,97], but hope is a key psychological resource associated with resilience and optimism [98]. Hope helps cope with loneliness and exclusion and maintain a positive outlook [98]. Zhao et al. [11] found that emotional intelligence improves relationships and anxiety management, with hope as a crucial mediator. Liu et al. [12] reported that social support and reduced hopelessness foster healthier self-identity. Other studies link hope with better emotion regulation and lower depression and anxiety [99,100]. Merolla et al. [50] noted that low hope correlates with greater conflict and weaker social bonds. Overall, fostering hope may lessen the negative impact of alienation on life satisfaction.

5.4 The Sequential Mediation Role of Social Identity and Hope in the Association between Interpersonal Alienation and Life Satisfaction

The findings further support Hypothesis 4, revealing that social identity and hope sequentially mediate the relationship between interpersonal alienation and life satisfaction. Social identity first buffers the effects of alienation [5,48]. García et al. [101] found that social identity enhances self-esteem and hope, boosting life satisfaction. Engeström and Sannino [61] argued that active group participation resolves internal conflict. In turn, hope elevates life satisfaction and amplifies the benefits of social identity [96,98]. Pei and Zaki [21] highlighted that early adult social ties foster stress resilience and mental health. Hou et al. [22] observed that a strong sense of meaning reduces depression by decreasing alienation and increasing life satisfaction. Passion and hope repeatedly link to resilience and lower alienation [100,102]. These insights reinforce the importance of interventions that promote social identity and hope as resources for well-being.

5.5 Consideration of Alternative Theoretical Models

Although this study tested a model in which interpersonal alienation influences life satisfaction through the sequential mediation of social identity and hope, alternative models could be considered. For instance, social identity or hope might function as antecedents rather than mediators, or life satisfaction could influence levels of alienation or hope. Previous research has proposed that social identity can precede hope and satisfaction, or that greater life satisfaction may reinforce group belonging and hope [52,95]. However, theoretical and empirical evidence support the sequential mediation model linking alienation with psychological distress, social identification, hope, and life satisfaction [5,61,98].

5.6 Gender, Grade, and Major Differences in Alienation, Hope, and Satisfaction

This study also identified significant group differences in perceived hope, life satisfaction, and alienation by demographic characteristics. Consistent with Liu et al. [12], group-specific factors affect identity formation and adjustment. Zhao et al. [11] noted similar demographic patterns. Male students reported higher hope and life satisfaction, aligning with Seeman [54]. First-year students reported higher alienation, likely due to limited integration, while seniors had higher satisfaction [48]. Students in natural sciences, engineering, and medicine reported less alienation, possibly owing to collaborative environments, whereas humanities and social science students reported more alienation, perhaps due to solitary study habits. Afridi et al. [55] found that interpersonal trust reduces alienation and enhances happiness. Universities can recognize these distinctions by developing targeted support programs for first-year and humanities students [5]. Future research should examine how academic environments relate to psychological well-being [95].

The present study not only supports but also extends several influential theoretical frameworks, including social support theory [48], psychological capital theory [98], and activity theory [61]. The results reinforce the argument that perceived social identity functions as a psychological buffer, providing individuals with a sense of safety and directly enhancing life satisfaction [48]. Concurrently, the role of hope as a core dimension of psychological capital receives further empirical support, underlining its capacity to counteract the adverse effects of interpersonal alienation [98].

A notable contribution of this research is its synthesis and expansion of recent theoretical developments. For instance, prior studies by Li et al. [18], Qian et al. [17], and Zhao et al. [11] have emphasized the interplay between loneliness, perceived social support, emotional intelligence, and hope in shaping psychological well-being. This study further integrates perspectives such as the importance of social connection [21] and the pursuit of meaning in life to reduce alienation [22]. By proposing and validating a sequential mediation model encompassing social identity and hope, the present research offers a more comprehensive understanding of psychological resilience and life satisfaction processes, particularly within multicultural environments [5]. Future research is encouraged to investigate these variables among culturally and demographically diverse populations, thereby refining and extending current theoretical models.

From a practical standpoint, the findings offer concrete recommendations for universities in shaping student support and intervention programs. Given the protective effects of social identity and hope in reducing alienation and promoting life satisfaction, higher education institutions are encouraged to foster campus environments that cultivate strong support networks. Initiatives such as empathy-based programs can facilitate the formation of meaningful social ties, thereby mitigating feelings of alienation [21]. In line with the findings of Liu et al. [12], it is also vital to reinforce support mechanisms for students who have encountered adversity, as these interventions can significantly enhance resilience.

Furthermore, regular workshops and seminars on developing students’ emotional intelligence can improve interpersonal skills and alleviate anxiety, contributing to greater life satisfaction [11]. When designing these interventions, universities need to account for differences in gender, academic year, and academic discipline, as these factors may shape students’ needs and experiences. Special attention should be directed towards first-year students and those from diverse cultural backgrounds, who may be especially susceptible to alienation [5,61]. Policymakers are also encouraged to consider extending such interventions to earlier stages of education, including primary and secondary school, by introducing resilience and identity-building programs to strengthen psychological well-being from a young age [100].

7 Limitations and Scope for Future Research

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, convenience sampling was used, so the findings may not be fully generalizable to all university students in Taiwan or elsewhere, as this approach can introduce certain biases [103]. Moreover, the sample consisted only of local Taiwanese students, excluding international students. This limits the external validity of the results and means that the associations observed here may not apply to students from different cultural or international backgrounds. Another limitation is the reliance on self-reported data, which may be influenced by social desirability or recall bias [104].

Future studies could use probability sampling to enhance representativeness and generalizability [105]. Including local and international students would help clarify whether the observed associations hold across diverse student populations. Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches could also yield a more nuanced understanding of the issues [106]. Additionally, cross-cultural comparative research may help verify whether the proposed model is robust across different cultural contexts and explore how cultural differences may be related to concepts such as alienation, social identity, hope, and life satisfaction [11,12,107]. Pursuing these directions would strengthen the theoretical and practical significance of future research.

Through a careful analysis of Taiwanese university students, this research has unpacked the complex relationships among interpersonal alienation, perceived social identity, perceived hope, and life satisfaction. Our findings confirm that social identity and hope buffer the adverse effects on life satisfaction. This conclusion fits well with the perspectives of Pei and Zaki [21] on social connection, Hou et al. [22] on life meaning, and Zhao et al. [11] on the power of emotional intelligence, all highlighting the importance of these pathways for building psychological resilience and satisfaction.

Even though this study has some limitations, such as relying on convenience sampling and self-reports, the practical implications are clear. Universities should develop programs that target students’ social identity, hope, emotional intelligence, and social connectedness, accounting for demographic differences, to help students adapt and thrive. Ultimately, this work adds a new theoretical understanding of how alienation and life satisfaction interact while offering concrete ideas for educational practice to build stronger psychological resilience among students.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the partial support of the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, grant number NSTC 113-2410-H-018-027, granted to the corresponding author, Dr. Yao-Chung Cheng.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Shu-Hsuan Chang: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision; Der-Fa Chen: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing; Jing-Tang Sie: Data Curation, Investigation, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Kai-Jie Chen: Data Curation, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Zhe-Wei Liao: Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft; Tai-Lung Chen: Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft; Yao-Chung Cheng: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Yao-Chung Cheng, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was conducted according to the ethical standards of institutional and national research committees, the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling | |

| Average Variance Extracted | |

| Composite Reliability | |

| Variance Inflation Factor | |

| Predictive Relevance (Q-square) | |

| Factor Loading | |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | |

| Comparative Fit Index | |

| Goodness of Fit Index | |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual | |

| Degree of Freedom | |

| Standard Error | |

| Confidence Interval | |

| Mean Absolute Error | |

| Root Mean Square Error | |

| Standardized Regression Coefficient | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha |

References

1. Turner JC , Brown RJ , Tajfel H . Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1979; 9( 2): 187– 204. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420090207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hogg MA , Turner JC . Intergroup behaviour, self stereotyping and the salience of social categories. Br J Soc Psychol. 1987; 26( 4): 325– 40. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1987.tb00795.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Klomegah RY . Social factors relating to alienation experienced by international students in the United States. Coll Stud J. 2006; 40( 2): 303– 15. [Google Scholar]

4. Pepanyan M , Meacham S , Logan S . International students’ alienation in a US higher education institution. J Multicult Educ. 2019; 13( 2): 122– 39. doi:10.1108/JME-10-2017-0057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ma Y , Zhan N . To mask or not to mask amid the COVID-19 pandemic: how Chinese students in America experience and cope with stigma. Chin Sociol Rev. 2022; 54( 1): 1– 26. doi:10.1080/21620555.2020.1833712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Caselman TD , Self PA . Adolescent perception of self as a close friend: culture and gendered contexts. Soc Psychol Educ. 2007; 10: 353– 73. doi:10.1007/s11218-007-9018-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jones C . An investigation into barriers to student engagement in higher education: evidence supporting ‘the psychosocial and academic trust alienation theory’. Adv Educ Res Eval. 2021; 2( 2): 153– 65. doi:10.25082/AERE.2021.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Misra R , McKean M . College students’ academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management, and leisure satisfaction. Am J Health Stud. 2000; 16( 1): 41– 51. [Google Scholar]

9. Solomon Y . Not belonging? What makes a functional learner identify in undergraduate mathematics? Stud High Educ. 2007; 32( 1): 79– 96. doi:10.1080/03075070601099473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Loizzo J , Thurman RA , Siegel DJ . Sustainable happiness: the mind science of well being, altruism, and inspiration. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2012. doi:10.4324/9780203854815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao Y , Sang B , Ding C . How emotional intelligence influences students’ life satisfaction during university lockdown: the chain mediating effect of interpersonal competence and anxiety. Behav Sci. 2024; 14( 11): 1059. doi:10.3390/bs14111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu L , Li J , Li Y . Mediating roles of perceived social support and hopelessness in the relationship between negative life events and self-identity acquisition among Chinese college students with left-behind and/or migrant experiences. Front Psychol. 2025; 16: 1530107. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1530107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Evans O , Cruwys T , Cárdenas D , Wu B , Cognian AV . Social identities mediate the relationship between isolation, life transitions, and loneliness. Behav Change. 2022; 39( 3): 191– 204. doi:10.1017/bec.2022.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Haslam SA , Haslam C , Cruwys T , Jetten J , Bentley SV , Fong P , et al. Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: implications for loneliness and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022; 43: 161– 5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Haslam C , Cruwys T , Haslam SA , Dingle G , Chang MXL . Groups 4 health: evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J Affect Disord. 2016; 194: 188– 95. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Allen R , Ye Y . Why deteriorating relations, xenophobia, and safety concerns will deter Chinese international student mobility to the United States? J Int Stud. 2021; 11( 2): i– vii. doi:10.32674/jis.v11i2.3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qian L , Hu W , Jiang M . The impact of online social behavior on college student’s life satisfaction: chain-mediating effects of perceived social support and core self-evaluation. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023; 16: 4677– 83. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S433156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li R , Fu W , Liang Y , Huang S , Xu M , Tu R . Exploring the relationship between resilience and internet addiction in Chinese college students: the mediating roles of life satisfaction and loneliness. Acta Psychol. 2024; 248: 104405. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chang EC , Caino PCG . Examining the integrated broaden-and-build model of positive emotions involving hope in a community sample of Argentinian adults: a selective test among victims of interpersonal aggression. Pers Individ Dif. 2024; 216: 112419. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2023.112419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bonetti C , Rossi F , Caricati L . Ingroup identification, hope and system justification: testing hypothesis from social identity model of system attitudes (SIMSA) in a sample of LGBTQIA+ individuals. Curr Psychol. 2023; 42: 7397– 402. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02062-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pei R , Zaki J . Connecting with others: how social connections improve the happiness of young adults. In: Helliwell JF , Layard R , Sachs JD , De Neve JE , Aknin LB , Wang S , editors. World happiness report 2025. New York, NY, USA: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2025. [Google Scholar]

22. Hou X , Hu J , Liu Z . Meaninglessness makes me unhappy: examining the role of a sense of alienation and life satisfaction in the relationship between the presence of meaning and depression among Chinese high school seniors. Front Psychiatry. 2025; 16: 1494074. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1494074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ji J , Zhou L , Wu Y , Zhang M . Hope and life satisfaction among Chinese shadow education tutors: the mediating roles of positive coping and perceived social support. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 929045. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.929045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun D , Lin Y , Liao C , Pan L . Online interpersonal trust and online altruistic behavior in college students: the chain mediating role of moral identity and online social support. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1452066. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1452066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hogg M . Social identity theory. In: van Lange PAM , Kruglanski AW , Higgins ET , editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 3– 17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29869-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hornsey M . Social identity theory and self categorization theory: a historical review. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2008; 2( 1): 204– 22. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Trepte S , Loy L . Social identity theory and self-categorization theory. In: Ritzer G , editor. Wiley blackwell encyclopedia of social theory. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 1– 13. doi:10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Turner JC , Oakes PJ , Haslam SA , McGarty C . Self and collective: cognition and social context. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1994; 20( 5): 454– 63. doi:10.1177/0146167294205002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Stecz P , Slezackova A , Millova K . Hope and mental health among Czech and Polish adults in a macrosocial perspective and religiosity context. In: Krafft AM , Guse T , Slezáčková A , editors. Hope across cultures: a comparative perspective. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 267– 85. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-24412-4_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Simpanen AL . Imagining the future in today’s China: university students’ images of the future [ master’s thesis]. Turku, Finland: University of Turku; 2025. [Google Scholar]

31. White M , Hungwe C . ‘It’s a lot of things’: Zimbabwean university students’ perceptions on the causes of suicide ideation and suicidality among youths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2024; 19( 1): 112– 24. doi:10.1080/17450128.2024.2326422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Adewale MD , Muhammad UI . From virtual companions to forbidden attractions: the seductive rise of artificial intelligence love, loneliness and intimacy—a systematic review. J Technol Behav Sci. 2025; 10( 3): 441– 57. doi:10.1007/s41347-025-00549-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zahavi D . Second-person engagement, self-alienation, and group-identification. Topoi. 2016; 38: 251– 60. doi:10.1007/s11245-016-9444-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Adam F . Self dissociation as a predictor of alienation and sense of belonging in university students. J Fam Couns Educ. 2023; 8( 4): 334– 45. doi:10.32568/jfce.1328750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Slimani M . Psychological and social alienation of the university student. Int J Humanit Educ Res. 2023; 5( 18): 96– 110. doi:10.47832/2757-5403.18.31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bekele D . The relationship between social identity and interpersonal relationship of Addis Ababa University students: the case of main campus [ master’s thesis]. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

37. Teshome W . The roles of social identity on students’ interpersonal interaction among Dire Dawa University students in Eastern Ethiopia: social psychological perspectives. Res Humanit Soc Sci. 2018; 8( 1): 42– 50. [Google Scholar]

38. Xu X , Zhao M , Wang MY , editors. Chinese social media II: insider, intercultural and interdisciplinary perspectives. 1st ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2025. doi:10.4324/9781003596516-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. The Migration Conference Team . The Migration Conference 2025 abstracts. Conference Ser. 36. London, UK: Transnational Press London; 2025. [Google Scholar]

40. Haslam SA , Cruwys C , Dingle T . The new psychology of health: unlocking the social cure. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2018. doi:10.4324/9781315648569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hengstenberg J . Playscaping the city: the potential of integrating urban action sports in public spaces as planning tool for social cohesion [ dissertation]. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Galgali MS , Helm PJ , Arndt J . Isolated but not necessarily lonely. J Individ Differ. 2024; 45( 1): 36– 45. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Rokach A . Loneliness then and now: reflections on social and emotional alienation in everyday life. Curr Psychol. 2004; 23( 1): 24– 40. doi:10.1007/s12144-004-1006-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Debnath A , Roy P . Social isolation and loneliness among urban older people: a study of Cooch Behar municipal town, West Bengal, India. Work Older People. 2019; 24( 2): 61– 71. doi:10.1108/WWOP-04-2019-0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cacioppo JT , Hawkley LC . Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009; 13( 10): 447– 54. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yang J , Zhang X , Huang X . Adolescent students’ sense of alienation: theoretical construct and scale development. Acta Psychol Sin. 2002; 34( 4): 77– 83. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2002.00077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Burbach HJ . The development of a contextual measure of alienation. Pac Sociol Rev. 1972; 15( 2): 225– 34. doi:10.2307/1388444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ahern NR , Norris AE . Examining factors that increase and decrease stress in adolescent community college students. J Pediatr Nurs. 2011; 26( 6): 530– 40. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2010.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Chen N , Jing Y , Pang Y . Relation between parent and child or peer alienation and life satisfaction: the mediation roles of mental resilience and self-concept clarity. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 1023133. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1023133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Merolla J , Bernhold Q , Peterson C . Pathways to connection: an intensive longitudinal examination of state and dispositional hope, day quality, and everyday interpersonal interaction. J Soc Pers Relat. 2021; 38( 7): 1961– 86. doi:10.1177/02654075211001933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Turan GB , Özer Z , Yanmış S . The effects of spiritual well-being on life satisfaction in hematologic cancer patients aged 65 and older in Turkey: mediating role of hope. Psychogeriatrics. 2024; 24( 5): 1149– 59. doi:10.1111/psyg.13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Haslam N , Jetten SA , Cruwys C , Haslam T , Bentley J . The social cure: identity, health and well-being. Psychol Health. 2012; 27( 3): 367– 86. doi:10.1080/08870446.2011.585305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Kneipp LB , Kelly KE , Cyphers B . Feeling at peace with college: religiosity, spiritual well-being, and college adjustment. Indiv Differ Res. 2009; 7( 3): 188– 96. doi:10.65030/idr.07018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Seeman M . Alienation studies. Annu Rev Sociol. 1975; 1: 91– 123. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.01.080175.000515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Afridi SA , Rehman K , Hussain A , Khan FB , Haider M . Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees’ extra-role behaviors: moderating role of ethical corporate identity and interpersonal trust. Corp Soc Responsib Env Manag. 2023; 30( 2): 991– 1004. doi:10.1002/csr.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Yuan Y , Yang Z , Zhou Z , Wang Y , Shen H , Song Y , et al. The relationship between self-esteem and happiness of college students in China: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Health Med. 2024; 29( 4): 721– 31. doi:10.1080/13548506.2023.2190985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Chan SCY , Huang QL . The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between hope and life satisfaction among university students during a global health crisis. Health Sci Rep. 2024; 7( 8): e2311. doi:10.1002/hsr2.2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Brown MR , Higgins K , Paulsen K . Adolescent alienation: what is it and what can educators do about it? Interv Sch Clin. 2003; 39( 1): 3– 9. doi:10.1177/10534512030390010101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Tarquin K , Cook Cottone C . Relationships among aspects of student alienation and self-concept. Sch Psychol Q. 2008; 23( 1): 50– 66. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Snyder M , Shorey CR , Cheavens D , Pulvers AJ , Adams V , Wiklund C . Hope and academic success in college students. J Educ Psychol. 2002; 94( 4): 820– 6. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Engeström Y , Sannino A . Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings, and future challenges. Educ Res Rev. 2010; 5( 1): 1– 24. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Stephanou G , Athanasiadou K . Interpersonal relationships: cognitive appraisals, emotions, and hope. Eur J Psychol Educ Res. 2020; 3( 1): 13– 38. doi:10.12973/ejper.3.1.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Barber K , Stolz HE , Olsen JA . Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2005; 70( 4): 1– 137. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Skinner EA , Kindermann TA , Furrer CJ . A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ Psychol Meas. 2009; 69( 3): 493– 525. doi:10.1177/0013164408323233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Degges White S , Turner KH , Kepic M , Randolph A , Killam W . Grandparent alienation: a mixed method exploration of life satisfaction and help seeking experiences of grandparents alienated from their grandchildren. Fam J. 2024: 10664807241282432. doi:10.1177/10664807241282432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Morinaj J , Hascher T . School alienation and student well being: a cross lagged longitudinal analysis. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2019; 34: 273– 94. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0381-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Van Ryzin MJ , Gravely AA , Roseth CJ . Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well being. J Youth Adolesc. 2009; 38: 1– 12. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9257-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Croft A , Grove M , editors. Transitions in undergraduate mathematics education. Birmingham, UK: The Higher Education Academy; 2015. [Google Scholar]

69. Newman B , Newman P . Group identity and alienation: giving the we its due. J Youth Adolesc. 2001; 30: 515– 38. doi:10.1023/A:1010480003929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. McKillup S . Statistics explained: an introductory guide for life scientists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139047500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Faul F , Erdfelder E , Buchner A , Lang AG . Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009; 41: 1149– 60. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Leavy P . Research design: quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts based, and community based participatory research approaches. New York, NY, USA: Guilford; 2022. [Google Scholar]

73. Stratton SJ . Population research: convenience sampling strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021; 36( 4): 373– 4. doi:10.1017/S1049023X21000649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Gorsuch RL . Three methods for analyzing limited time-series (N of 1) data. Behav Assess. 1983; 5: 141– 54. [Google Scholar]

75. Brislin RW . Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970; 1( 3): 185– 216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Chou C , editor. Who benefits from Taiwan’s mass higher education? Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2015. p. 231– 43. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12673-9_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Li J . School experience in Taiwan: social class and gender differences [ dissertation]. Los Angeles, CA, USA: University of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

78. Wang YS , Wang YM , Yang YF , Ye SY . What drives students’ knowledge withholding intention in management education? An empirical study in Taiwan. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2014; 13( 4): 547– 68. doi:10.5465/amle.2013.0066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Snyder CR , Sympson SC , Ybasco FC , Borders TF , Babyak MA , Higgins RL . The development and validation of the state hope scale. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996; 70( 2): 321– 35. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Diener E , Emmons RA , Larsen RJ , Griffin S . The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985; 49( 1): 71– 5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Podsakoff PM , MacKenzie SB , Lee JY , Podsakoff NP . Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003; 88( 5): 879– 903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Hair JF Jr , Howard MC , Nitzl C . Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J Bus Res. 2020; 109: 101– 10. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Podsakoff PM , MacKenzie SB , Podsakoff NP . Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012; 63( 1): 539– 69. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Hair JF , Risher JJ , Sarstedt M , Ringle CM . When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019; 31( 1): 2– 24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Fornell C , Larcker DF . Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981; 18( 1): 39– 50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]