Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Understanding Young Adults’ Social Media Anxiety: Mediating Role of Upward Social Comparison and the Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience

1 Institute of Communication Studies, Communication University of China, Beijing, 100020, China

2 Department of Interactive Media, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong, 999077, China

* Corresponding Author: Jianhong Wu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Psychological Well-being and Psychopathology in the New Millennium: Evolving Paradigms, Challenges, and Resources)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1883-1896. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071306

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Platform algorithms driving content presentation are profoundly shaping the experience of younger users. While prior research has examined anxiety stemming from young adults’ social media usage, the link between upward social comparison and anxiety remains unclear. This study aims to investigate the mediating role of upward social comparison in this relationship and determine the moderating role of psychological resilience. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 562 young Chinese adults aged 18–35 (53% female). Data were collected via an online questionnaire employing validated measurement instruments, including scales for social media usage patterns, upward comparator behaviour (INCOM), anxiety levels (GAD-7), and psychological resilience (RSA). Correlation analysis, mediation analysis, and moderation analysis were conducted using SPSS 29.0. Results: As predicted, the results indicate that upward social comparison mediates the relationship between both active (β = −0.11, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.08]) and passive (β = 0.11, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.15]) social media use and anxiety. Furthermore, psychological resilience (βlow = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.14]; βhigh = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.09]) moderated the indirect effect of passive social media use on anxiety through upward social comparison. Conclusion: The findings indicate that upward social comparison significantly influences the anxiety experienced by young social media users, with psychological resilience playing a crucial moderating role. These results offer valuable insights for optimizing content recommendation algorithms on social media platforms to better support young adults’ mental health.Keywords

Since the early decades of the 21st century, digital hyperconnectivity has profoundly reshaped individuals’ experiences of identity, success, and emotional well-being [1]. This effect is particularly evident among the millennial generation immersed in social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok. Prolonged exposure to carefully curated and amplified content emphasizing idealized attributes—such as academic achievement, lifestyle, and physical appearance—systematically triggers comparison pressures that extend beyond users’ voluntary control. This phenomenon introduces new psychological challenges, notably anxiety related to involuntary upward social comparisons [2]. Moreover, platforms strategically employ algorithmic techniques to continuously present users with content highlighting others’ accomplishments and successes. This practice intensifies the frequency of upward social comparisons among young users, fostering persistent feelings of inadequacy. Consequently, it undermines their self-worth [3], thereby constituting a structural mental health problem [4].

Although extensive literature acknowledges the negative mental health consequences of social media use (SMU) [5], existing research predominantly focuses on individual usage patterns rather than the structural forces mediated by platforms. Most studies overlook how algorithmic content curation mechanisms amplify users’ exposure to idealized content, promoting repeated and involuntary upward comparisons that exacerbate anxiety associated with social media use. Furthermore, the role of psychological resilience in coping with social media–induced anxiety among young adults remains underexplored. This is especially true in collectivist contexts such as China, where family and community norms exert profound influences on individual psychological adaptation [6]. Unlike groups that primarily rely on individualistic coping strategies, Chinese young adults often depend on relational and interdependent coping mechanisms deeply rooted in Confucian traditions and family structures. These cultural scripts facilitate family-and peer-based co-regulation and shared meaning-making, serving as key resources for managing psychological stress [7,8,9].

To address these critical gaps, this study draws on Festinger’s social comparison theory and the culturally embedded psychological resilience framework [7,10,11]. It examines whether active and passive social media use influence anxiety through upward social comparison and whether psychological resilience moderates the anxiety caused by upward social comparison. In summary, this research adopts an interdisciplinary perspective to deepen our understanding of the pathways shaping social media–related anxiety among young adults. It also highlights the vital role of psychological resilience in maintaining young adults’ mental health within digital environments, offering insights to better support young adults’ well-being through digital technologies in the future.

In China’s mobile-first platform ecosystem, personalized recommendations have become the default gateway, and users interact around profiles, connections, and algorithmically assembled streams of user-generated content. This ecology increases content accessibility and exposure while reshaping the visible boundaries and interaction rules of everyday sociality. A considerable body of research has identified that the way social media is used can significantly influence psychological outcomes, particularly anxiety [12]. To precisely assess the psychological impact, social media use (SMU) is typically classified into two categories: active use, characterized by content creation, sharing, commenting, and engaging interactions; and passive use, involving browsing content without interactive participation [13].

Empirical evidence suggests divergent psychological consequences associated with these different usage patterns. Active SMU may enhance psychological well-being by fostering social capital accumulation, where reciprocal interactions (e.g., receiving likes, building support networks) reinforce a sense of belonging [12]. However, emerging evidence suggests that self-promotional active use (e.g., curating idealized self-presentations) can paradoxically heighten anxiety through impression management pressures [14]. This tension underscores the necessity of a nuanced operationalization of SMU types. Adopting an improved framework from Verduyn et al. [13], the present study aims to elucidate the different effects that active and passive social media use have on anxiety.

Thus, the existing evidence leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Active social media use negatively affects users’ anxiety levels.

Hypothesis 2: Passive social media use positively affects users’ anxiety levels.

2.2 Upward Social Comparison and Anxiety

Social comparison theory, first introduced by Festinger [10], argues that individuals have an inherent drive to evaluate their own abilities and opinions by comparing themselves with others. Particularly, upward social comparison—comparing oneself with individuals perceived as superior—often triggers negative emotional outcomes, such as reduced self-esteem and increased anxiety [15]. Although current studies suggest that upward social comparison with outstanding others can inspire individuals, provide role models, and enhance motivation [16], as well as boost users’ self-efficacy, thereby increasing motivation and engagement in physical activity [17]. But Diel et al. [18] found that persistent upward social comparison leads to greater self-improvement motivation but also more negative emotions. Moreover, Xu and Li [19] showed that such comparisons can further increase social anxiety among Chinese college students by triggering relative deprivation and rumination.

Despite this duality, upward social comparison has traditionally been situational and voluntary; social media platforms now reinforce and automate its negative emotional impact by continuously exposing users to algorithmically filtered content showcasing extraordinary achievements, idealized appearances, or desirable lifestyles [20].

Upward social comparison is particularly amplified by passive SMU, as passive users frequently encounter idealized portrayals without sufficient contextualization, leading to exaggerated negative self-assessments and heightened anxiety [21]. Conversely, active SMU potentially provides users a greater sense of control over the content they interact with, thereby decreasing the frequency of involuntary upward comparisons [22].

Thus, social comparison acts as a critical psychological mechanism through which different SMU types influence mental health. These considerations give rise to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Active social media use negatively influences users’ upward social comparison.

Hypothesis 4: Passive social media use positively influences users’ upward social comparison.

Hypothesis 5: Upward social comparison negatively mediates the relationship between active social media use and anxiety.

Hypothesis 6: Upward social comparison positively mediates the relationship between passive social media use and anxiety.

Given the complexity of the relationships between social media usage, social comparison, and anxiety, mediating and moderating variables must be considered. Psychological resilience, defined as an individual’s capacity to adapt positively despite adversity or stress, has emerged as a crucial moderator in buffering negative psychological outcomes [11]. Research has shown that positive parent-child relationships, secure attachment, and fewer negative interactions during childhood contribute to the development of psychological resilience in young adulthood [23]. Throughout the developmental process, social support from friends, family, and significant others also serves as a crucial source of resilience for young adults [24]. Resilience, in turn, can mitigate anxiety by enabling individuals to positively reframe stressful experiences and adopt adaptive coping strategies [25].

Importantly, resilience has cultural dimensions. In Western countries, particularly in Europe and North America, resilience tends to emphasize individualism, personal autonomy, and self-efficacy as its core components [26]. And in collectivist societies such as China, resilience is often relational and culturally embedded, drawing strength from interpersonal connections, community support, and traditional family values [27]. Cultural frameworks significantly shape how individuals interpret and cope with upward social comparison in digital contexts, as resilience is influenced by culturally embedded values and social norms that determine responses to stress [28]. This study adopts a contemporary cross-cultural perspective, conceptualizing psychological resilience primarily as a universal human capacity to endure and adapt to adversity [29], meaning that the pathways to cultivate this capacity, its manifestations, and its socio-ecological context are deeply embedded within specific cultures.

Resilient individuals are likely to cognitively reinterpret the idealized portrayals encountered online as performative or aspirational rather than realistic benchmarks. Such reinterpretations can significantly reduce anxiety derived from upward comparisons, especially when passively consuming content. Conversely, resilience can strengthen the positive effects of active SMU by reinforcing self-efficacy, narrative control, and adaptive emotional regulation strategies [25].

Therefore, psychological resilience is expected to moderate the mediating pathways involving upward social comparison between social media use and anxiety. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 7: Psychological resilience moderates the role of upward social comparison between active social media use and anxiety levels.

Hypothesis 8: Psychological resilience moderates the mediating role of upward social comparison between passive social media use and anxiety levels.

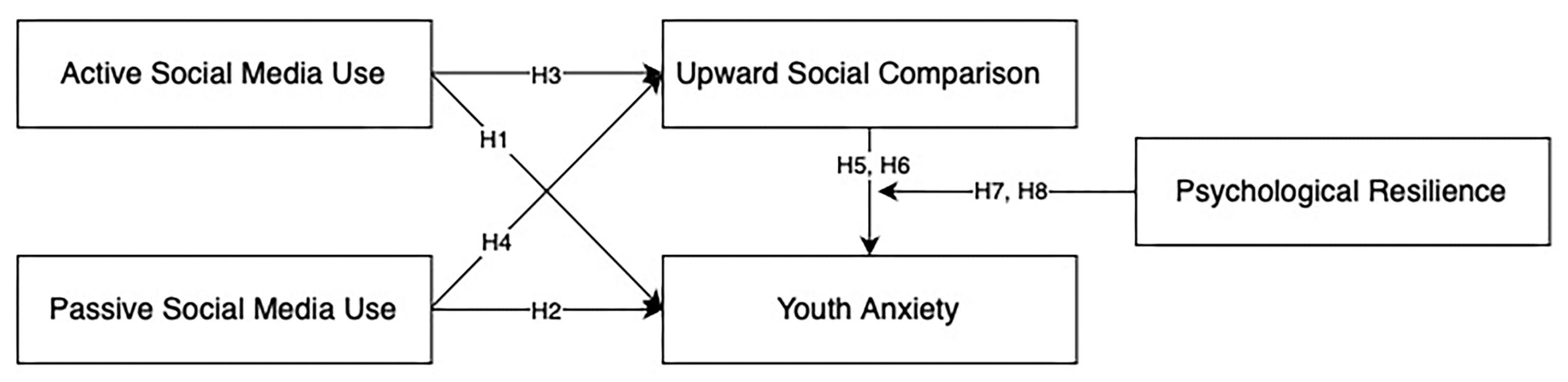

Overall, based on the above theoretical and empirical research, this study employs a moderated parallel mediation model for testing, as shown in Fig. 1. The findings can assist social media platforms in optimizing content recommendation algorithms, thereby fostering a healthier online environment for adolescent mental health.

Figure 1: Diagram of the research model.

This research employed a cross-sectional design. The data were collected through an online survey conducted by Question Star (Wenjuan Star) from 20 to 25 May 2025. Question Star is a widely used academic and market research platform in China. Prior to the formal survey, we conducted a pilot test of 50 participants (demographics matched the target population) from 17 to 19 May 2025, to evaluate the reliability and effectiveness of the questionnaire. Based on feedback from a panel of five experts in social media psychology and psychometrics, ambiguous or culturally insensitive items were revised to enhance clarity and contextual relevance. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Baptist University, approval No. COMM-AIDM-202425_001, on 13 May 2025. All participants provided informed consent before participation. All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the university’s ethical guidelines.

3.2 Participants and Inclusion Criteria

The study focused on young adults in China, as this group heavily relies on digital connectivity and is in a developmental stage characterized by identity exploration and goal evaluation within online environments. Based on previous research by Willmott et al. [30] and Arnett [31], participants were required to be between 18 and 35 years old and reside in China. To minimize the potential impact of gender differences on the results, a quota sampling method was adopted to ensure a balanced representation of genders.

The initial sample consisted of 603 participants; 6 blank submissions and 35 attention-check failures were removed, yielding 562 valid responses. All participants were aged between 18 and 35 and lived in China. Approximately 53% of the participants were female. Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 562).

| Category | Subcategory | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 264 | 47.0% |

| Female | 298 | 53.0% | |

| Age | 18–25 years | 241 | 42.9% |

| 26–35 years | 321 | 57.1% | |

| City Tier | Tier 1 (e.g., Beijing) | 152 | 27.0% |

| Tier 2 (e.g., Chengdu) | 224 | 39.9% | |

| Tier 3 and below | 186 | 33.1% | |

| Education Level | High School or Below | 64 | 11.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 387 | 68.9% | |

| Master’s or Above | 111 | 19.8% | |

| Annual Household Income | <100k RMB | 149 | 26.5% |

| 100k–300k RMB | 350 | 62.3% | |

| >300k RMB | 63 | 11.2% |

All scales were adapted from validated instruments and modified to align with China’s digital and cultural context. Response options were standardized to minimize cognitive load. In this study, active-passive social media use was the independent variable, upward social comparison was the mediating variable, anxiety level was the dependent variable, and psychological resilience was the moderating variable.

3.3.1 Active-Passive Social Media Use

Active SMU was measured using three items adapted from Li [33], originally derived from Pagani and Mirabello [34]. Example item: “I proactively search for content on social media to improve my academic or professional skills”. Passive SMU was assessed via three items [33], e.g., “I often scroll through social media feeds without a specific purpose”. Algorithmic Exposure Perception was added as a supplementary dimension, measured by two items (e.g., “I frequently encounter narratives about successful individuals on my social media homepage”). All items used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was 0.803 (active SMU) and 0.781 (passive SMU).

3.3.2 Upward Social Comparison

Upward social comparison (USC) was assessed using a six-item scale adapted for the Chinese context [35], focusing on comparison targets specific to social media platforms. Given that USC frequently occurs during passive browsing, items emphasized comparison with “other people on social networking sites”. For example, one statement read: “On social networking sites, I always like to compare myself with other people who perform better than me”. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), demonstrating high internal consistency (α = 0.908). This measurement approach aligns with prior studies that examined social comparison orientation in relation to passive social media use and emotional outcomes [36].

3.3.3 Psychological Resilience

The present study employed the culturally adapted Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) to measure psychological resilience [37]. This scale comprised six items, including the question, “I believe that I have the ability to cope with stressful messages on social media”. The scale incorporates Confucian relational dynamics, including items such as “My family helps me keep a balanced perspective on idealized social media portrayals”, and this multidimensionality allows the study to accurately capture subjects’ behavioural patterns and their psychological conditions in China’s unique digital ecosystem. The options are on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very inconsistent) to 5 (very consistent). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this latent variable was 0.875.

Anxiety symptoms were evaluated using a modified 5-item subset of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [38], tailored to social media contexts (e.g., “I cannot stop or control anxiety caused by social media”). To reduce respondent burden while preserving validity, we selected items covering core worry and physiological arousal domains. Short forms of the GAD-7 (2–6 items) retain strong diagnostic performance with cross-cultural generalizability [39]; moreover, brief GAD measures are validated in Chinese young-adult samples (e.g., GAD-2 in Chinese college students; GAD-7 shows excellent reliability and measurement invariance in Chinese medical university students) [40,41]. Responses ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), and the 5-item scale showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.789).

SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data management and analysis. The process comprised three steps: First, preliminary analyses were conducted to calculate descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for the variables. Second, regression analysis and mediation effect analysis were performed using Model 4 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro [42]. Finally, the moderation effect analysis was conducted using Model 14 within the PROCESS macro. All models employed the Bootstrap analyses (5000 resamples) to assess the significance of direct and indirect effects.

Prior to testing the mediation and moderation effects, correlation analyses were conducted. The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables are presented in Table 2. The results showed that active SMU was negatively correlated with passive SMU. Upward social comparison was positively correlated with passive SMU and negatively correlated with active SMU. Psychological resilience was negatively correlated with both passive SMU and upward social comparison but positively correlated with active SMU. Anxiety was positively correlated with passive SMU and upward social comparison and negatively correlated with both active SMU and psychological resilience. Furthermore, since age was not significantly correlated with any core variables, gender, cities classification, education level, and annual household income were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 2: Means, standard deviations (SD), and correlations among variables (n = 562).

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.53 | 0.50 | - | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 1.57 | 0.50 | 0.01 | - | ||||||||

| 3. CT | 2.06 | 0.77 | −0.05 | 0.02 | - | |||||||

| 4. Edu | 2.08 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | - | ||||||

| 5. AHI | 1.85 | 0.60 | −0.00 | 0.09* | −0.05 | 0.15** | - | |||||

| 6. PSMU | 3.33 | 1.08 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.11** | 0.02 | - | ||||

| 7. ASMU | 2.77 | 1.12 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.12** | 0.01 | −0.28** | - | |||

| 8. USC | 3.23 | 1.14 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.14** | −0.04 | 0.35** | −0.41** | - | ||

| 9. PR | 2.52 | 0.97 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10* | 0.12** | 0.09* | −0.49** | 0.36** | −0.43** | - | |

| 10. Anxiety | 1.6 | 0.81 | 0.13** | −0.04 | −0.18** | −0.12** | −0.08 | 0.33** | −0.41** | 0.49** | −0.52** | - |

4.2 Mediating Role of Upward Social Comparison

To test the mediating effects of upward social comparison, we conducted regression analyses using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5000 bootstrap resamples [42]. Unstandardized regression coefficients revealed significant direct effects:

Active social media use (Model 1, Table 3) negatively predicted anxiety levels (β = −0.18, p < 0.001) and upward social comparison tendencies (β = −0.40, p < 0.001), supporting Hypotheses 1 and 3. Passive social media use (Model 2, Table 3) positively predicted anxiety levels (β = 0.14, p < 0.001) and upward social comparison (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), supporting Hypotheses 2 and 4.

Table 3: Regression results for the mediation models.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upward Social Comparison | Anxiety (Y) | Upward Social Comparison | Anxiety (Y) | |

| Constant | 4.73*** | 1.62*** | 2.41*** | 0.59** |

| Controls | ||||

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.16* | 0.08 | 0.17** |

| Cities Classification | −0.00 | −0.18*** | 0.01 | −0.18*** |

| Education Level | −0.19* | −0.05 | −0.20* | −0.05 |

| Annual Household Income | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.10* |

| Predictors | ||||

| Active Social Media Use | −0.40*** | −0.18*** | - | - |

| Passive Social Media Use | - | - | 0.36*** | 0.14*** |

| Mediators | ||||

| Upward Social Comparison | - | 0.27*** | - | 0.30 |

| R2 = 0.17 | R2 = 0.34 | R2 = 0.14 | R2 = 0.32 | |

Bootstrap analyses further demonstrated significant indirect effects (Table 4) that, for active use, upward social comparison mediated the negative association between SMU and anxiety (indirect effect = −0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.08]), supporting Hypothesis 5. For passive use, upward social comparison mediated the positive association between SMU and anxiety (indirect effect = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.15]), supporting Hypothesis 6.

Table 4: Mediation Effect of Upward Social Comparison between Social Media Use and Anxiety.

| Path | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | ||||

| ASMU → Anxiety | −0.29 | 0.03 | −0.34 | −0.23 |

| PSMU → Anxiety | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.30 |

| Direct effect | ||||

| ASMU → Anxiety | −0.18 | 0.03 | −0.23 | −0.12 |

| PSMU → Anxiety | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.19 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| ASMU → USC → Anxiety | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.15 | −0.08 |

| PSMU → USC → Anxiety | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

4.3 Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience

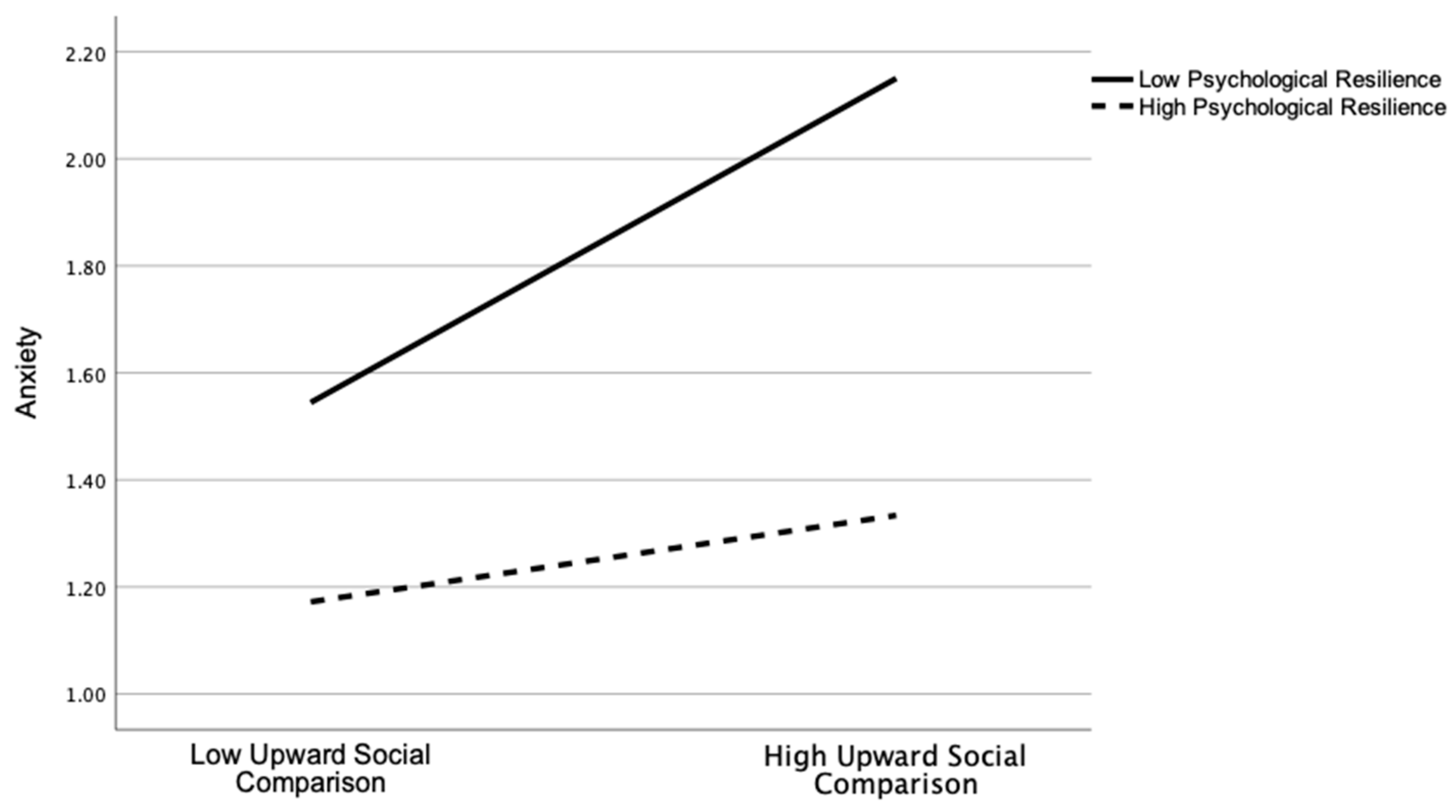

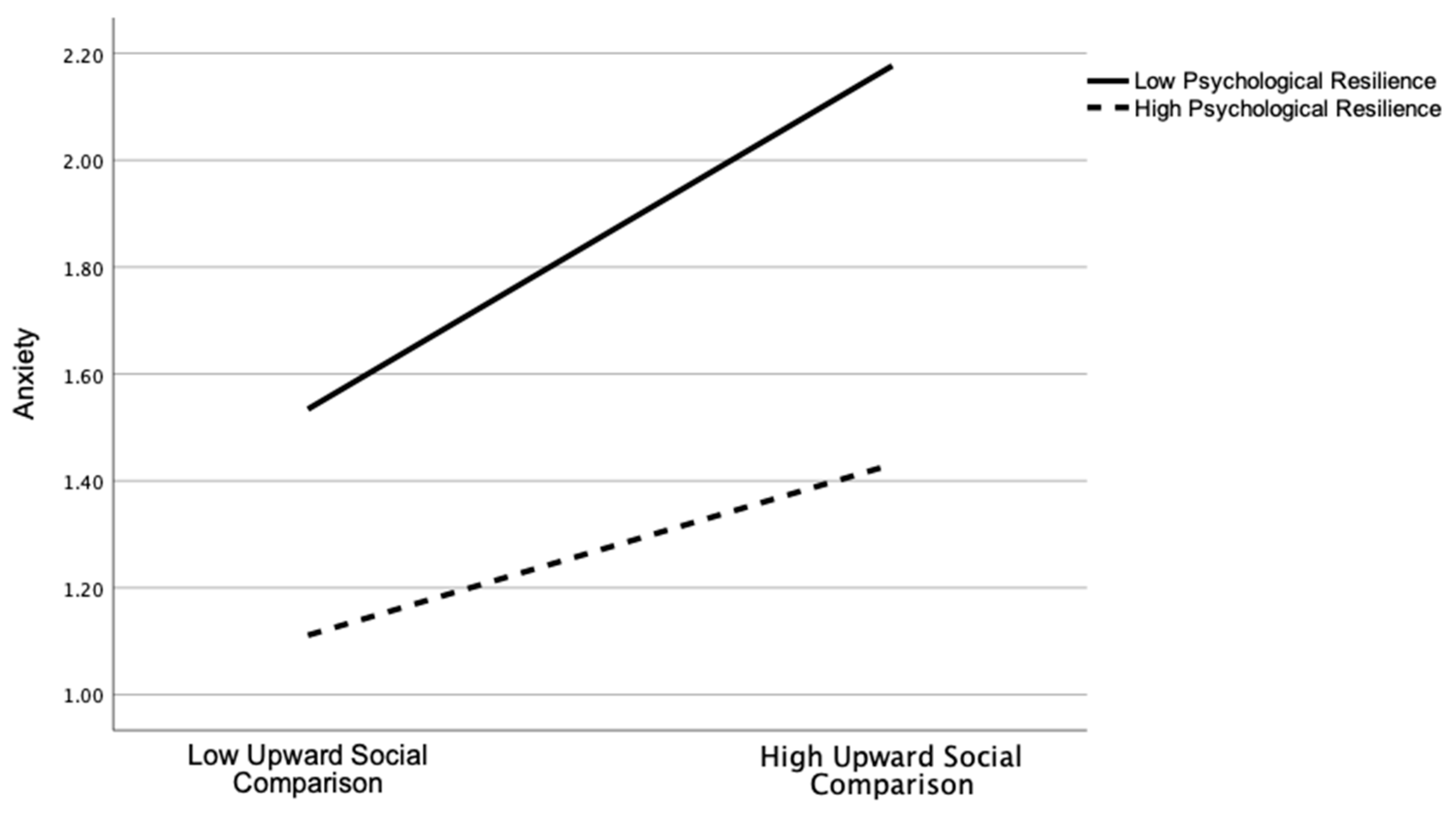

To examine the moderating effects of psychological resilience, we employed PROCESS macro (Model 14) with 5000 bootstrap iterations on SPSS 29.0 [42]. The results indicated that (Table 5), for active SMU (Fig. 2), the mediating effect of upward social comparison on anxiety was significant only among individuals with low resilience (indirect effect = −0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.07]), but nonsignificant for those with high resilience (indirect effect = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.07, 0.01]), partially supporting Hypothesis 7. For passive SMU (Fig. 3), the mediating effect remained significant across resilience levels but was attenuated among high-resilience individuals (low resilience: indirect effect = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.14]; high resilience: indirect effect = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.09]), supporting Hypothesis 8.

Table 5: Moderated Mediation Effect of Psychological Resilience.

| Path | PR | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean − SD (−1) | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| ASMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean − SD (0) | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| ASMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean + SD (1) | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| PSMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean − SD (−1) | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| PSMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean − SD (0) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| PSMU → USC → Anxiety | Mean + SD (1) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

Figure 2: For active social media use (SMU), upward social comparison predicts anxiety at low resilience, but not at high resilience (−1 SD vs. +1 SD; 95% CI).

Figure 3: For passive social media use (SMU), upward social comparison predicts anxiety at both levels, but is weaker at high resilience (−1 SD vs. +1 SD; 95% CI).

The study first confirms findings from a large body of research focusing on individual social media usage patterns. Specifically, passive social media use, which involves browsing with little direct interaction, is associated with higher anxiety among Chinese young adults. This aligns with Lai et al.’s [43] findings on social anxiety among Chinese university students. It is also consistent with Taylor et al.’s [44] research, which suggests that passive social media use is associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and stress among UK adults. In contrast, active social media use reduces anxiety. This result is consistent with Escobar-Viera et al.’s [45] study of adults in the United States. Furthermore, Koh et al.’s [46] scoping review supports that positive and purposeful social media use benefits mental health.

Building upon the foundation, our study introduces upward social comparison as an explanatory mechanism to reveal how platform algorithms reinforce these established pathways. The results showed that upward social comparison positively mediates the effect of passive social media use on anxiety. This suggests that algorithm-driven environments amplify comparison-based stress [20]. For example, algorithmic recommendation systems deployed by platforms like Xiaohongshu increase users’ exposure to elite and success-oriented content (e.g., “985 university admissions”, “million-dollar earnings”). While passively scrolling, users can unintentionally trigger a continuous stream of such content, leading to cognitive overload and unanticipated upward social comparisons [47]. These involuntarily triggered comparisons challenge a core assumption of Festinger’s social comparison theory—that individuals autonomously choose their targets for comparison [10].

By contrast, active social media use is associated with lower upward social comparison, which in turn is associated with lower anxiety. This mechanism operates through narrative agency and social support. Users who actively create content, such as sharing study notes, personal reflections, or creative work, reestablish a sense of agency by shifting their role from passive observer to active narrator. This process facilitates cognitive restructuring, enhances perceived control over one’s environment, and fosters a coherent sense of identity [13]. It can also trigger domain-specific social validation, such as academic encouragement, which strengthens collective belonging and mitigates the negative effects of upward comparison [48]. These findings suggest that not all social media use is harmful, and the nature of participation is critical in understanding psychosocial outcomes.

In addition, context collapse—where academic success and material wealth content (e.g., graduate school announcements alongside luxury brand unboxings) appear side by side—forces users into multi-domain comparisons [49]. This cross-dimensional exposure can exacerbate self-devaluation, particularly among young adults navigating identity formation in hyperconnected digital environments [50,51]. These platform-induced pressures represent a contemporary class of stressors in the new millennium. As such, our findings support calls to treat algorithmic environments as affective infrastructures that systematically generate emotional strain.

This study further examines the role of psychological resilience, revealing cognitive and cultural dimensions of the mediating mechanism. The results indicated that individuals with low resilience experience more anxiety from upward social comparison when actively using social media. In contrast, those with high resilience show reduced anxiety from upward comparison even during passive use. This may be because individuals with low resilience lack positive psychological capital [52] and are more prone to envy and shame when facing unfavorable comparisons [53], thereby worsening anxiety. In contrast, highly resilient individuals demonstrate stronger cognitive reappraisal abilities. They are more likely to interpret algorithm-recommended elite content as performance-based or inspirational, rather than as accurate depictions of peer success [54,55]. This cognitive difference helps maintain self-esteem despite repeated exposure to idealized content. Additionally, psychological resilience may also be shaped by sociocultural forces. In our sample of Chinese young adults (18–35), family-and peer-based support and collective meaning-making—salient in collectivist settings—serve as resources for coping with psychological stress [56]. We cautiously note that, in some circumstances, these relational resources may help reappraise upward exposure as aspirational rather than evaluative [57].

Translating this into practice, several targeted steps follow. To address anxiety triggered by passive content consumption, platforms could introduce user-controlled features that allow individuals to adjust their content exposure. For instance, digital nudging strategies have already been tested on platforms such as Instagram, where timely prompts co-designed with users have been shown to reduce overuse and promote well-being without compromising user autonomy or privacy [58]. These feedback-based mechanisms could be adapted to address content-related exposure. For example, prompting users to explore different themes after prolonged passive scrolling may help disrupt upward comparison cycles and alleviate emotional fatigue. Regarding the role of psychological resilience, young adult users are encouraged to shift from being passive consumers to active self-managers of their social media use. This involves consciously reducing aimless, passive browsing.

Furthermore, our study also offers direct implications for digital citizenship education. We suggest integrating the distinction between passive and active social media use into digital literacy curricula for school-aged youth. This content is particularly suitable for lessons on healthy digital habits. Specifically, educators can help students differentiate between these two usage patterns. Students can learn to understand their different impacts on psychology and emotion. This knowledge can empower them to adjust their own online behaviors. The goal is to shift from passive content consumption to active and meaningful social participation. Ultimately, this educational approach aims to strengthen self-awareness and agency among young users. It helps to build a foundation for their long-term digital well-being.

6 Limitations and Future Directions

Despite offering valuable insights, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and tests of temporal order. Beyond the pathway we tested (passive use → upward social comparison → anxiety), alternative sequences cannot be ruled out, for example, social media use → anxiety → upward social comparison, or pre-existing anxiety leading to greater passive use and upward comparison. Platform policies and recommendation weights also evolve over time; periodic tuning of sensitive-content exposure may alter users’ feeds, yet the durability of any psychological effects has not been established. Longitudinal designs are needed to assess how platform-level interventions shape mental health outcomes over time.

Second, reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential response biases and may underestimate actual behaviors [59]. Because all variables were collected from the same respondents at a single time point, common-method variance and single-source bias are possible. Objective data sources such as screen time analytics, clickstream logs, and eye-tracking technologies should be incorporated in future studies to enhance measurement accuracy and ecological validity [60]. In addition, our use of a brief 5-item anxiety measure should be complemented in future work by the full GAD-7 and, where feasible, clinical or interview-based assessments.

Third, while this study focused on the detrimental effects of upward social comparison, it did not account for the potential regulatory or compensatory role of downward comparisons—for example, deriving reassurance or self-esteem from observing others in less favorable situations. Future studies should also test boundary conditions under which upward exposure is motivational (e.g., attainable, self-relevant targets), alongside the risk pathway. Furthermore, future research could adopt a broader comparison framework to capture the full spectrum of comparison dynamics and their emotional consequences.

Additionally, our findings are based on a Chinese young adults sample aged 18–35, which may limit generalizability. The culturally embedded nature of collective resilience—rooted in Confucian familial values—raises important questions about cross-cultural transferability. Rather than assuming portability, future work should examine whether relationally scaffolded resilience can be distinguished from more individualistic coping models and whether similar moderation emerges in other East Asian settings with shared traditions. It also remains an open question whether design features that scaffold relational support (e.g., family-linked narrative threads or community-anchored feedback loops) reduce comparison stress outside China; these ideas warrant field evaluation before policy adoption.

Finally, comparative research across different platforms (e.g., Xiaohongshu, TikTok, Instagram) and cultural contexts is essential to identify how content typologies and platform architectures influence social comparison behaviors and anxiety. Such work will contribute to building a more culturally inclusive and structurally aware model of digital well-being in the 21st century.

This study examined anxiety related to social media use (SMU) among Chinese young adults, focusing on the mediating role of upward social comparison (USC) and the moderating role of psychological resilience (PR). A survey of 562 participants revealed three key findings. First, active SMU was associated with lower anxiety and less USC, while passive SMU was linked to higher levels of both. Second, USC negatively mediated the relationship between active SMU and anxiety, but positively mediated the relationship between passive SMU and anxiety. Third, for active SMU, USC predicted anxiety only when PR was low. For passive SMU, it predicted anxiety regardless of PR level. These findings enhance our understanding of social media anxiety from an algorithmic and platform perspective, providing an empirical basis for mental health education, targeted interventions, and healthier social media platform development.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Jinqian Li; methodology, Jinqian Li and Jianhong Wu; software, Jianhong Wu; formal analysis, Jinqian Li and Jianhong Wu; investigation, Jinqian Li; resources, Jinqian Li; writing—original draft preparation, Jinqian Li and Jianhong Wu; writing—review and editing, Jinqian Li and Jianhong Wu; supervision, Jinqian Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Baptist University, Approval No. COMM-AIDM-202425_001, on 13 May 2025. All participants gave informed consent before participation. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines of the university.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Vuorre M , Orben A , Przybylski AK . There is no evidence that associations between adolescents’ digital technology engagement and mental health problems have increased. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021; 9( 5): 823– 35. doi:10.1177/2167702621994549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fardouly J , Diedrichs PC , Vartanian LR , Halliwell E . Social comparisons on social media: the impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image. 2015; 13: 38– 45. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. McComb CA , Vanman EJ , Tobin SJ . A meta-analysis of the effects of social media exposure to upward comparison targets on self-evaluations and emotions. Medium Psychol. 2023; 26( 5): 612– 35. doi:10.1080/15213269.2023.2180647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Burke M , Kraut RE . The relationship between social capital and well-being on a social networking site. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2016; 21( 4): 265– 81. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Best P , Manktelow R , Taylor B . Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: a systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014; 41: 27– 36. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qi C , Yang N . An examination of the effects of family, school, and community resilience on high school students’ resilience in China. Front Psychol. 2024; 14: 1279577. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1279577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xie Q , Wong DFK . Culturally sensitive conceptualization of resilience: a multidimensional model of Chinese resilience. Transcult Psychiatry. 2021; 58( 3): 323– 34. doi:10.1177/1363461520951306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ji LJ , Yap S , Khei ZAM , Wang X , Chang B , Shang SX , et al. Meaning in stressful experiences and coping across cultures. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2022; 53( 9): 1015– 32. doi:10.1177/00220221221109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Paley B , Hajal NJ . Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2022; 25( 1): 19– 43. doi:10.1007/s10567-022-00378-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Festinger L . A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954; 7( 2): 117– 40. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Connor KM , Davidson JRT . Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18( 2): 76– 82. doi:10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Verduyn P , Ybarra O , Résibois M , Jonides J , Kross E . Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2017; 11( 1): 274– 302. doi:10.1111/sipr.12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Verduyn P , Gugushvili N , Kross E . Do social networking sites influence well-being? The extended active-passive model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2022; 31( 1): 62– 8. doi:10.1177/09637214211053637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shakya HB , Christakis NA . Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: a longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017; 185( 3): 203– 11. doi:10.1093/aje/kww189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Saiphoo AN , Vahedi Z . A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput Hum Behav. 2019; 101: 259– 75. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Andreeva I , Kim Y , Chung S . Inspiration by role models: the effect of source similarity, perceived goal attainability, and dispositional optimism. J Medium Psychol. 2024; 36( 6): 390– 6. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kim HM . Social comparison of fitness social media postings by fitness app users. Comput Hum Behav. 2022; 131: 107204. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Diel K , Hofmann W , Grelle S , Boecker L , Friese M . Prepare to compare: effects of an intervention involving upward and downward social comparisons on goal pursuit in daily life. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2025; 51( 9): 1523– 37. doi:10.1177/01461672231219378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xu L , Li L . Upward social comparison and social anxiety among Chinese college students: a chain-mediation model of relative deprivation and rumination. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1430539. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1430539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Appel H , Gerlach AL , Crusius J . The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016; 9: 44– 9. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lup K , Trub L , Rosenthal L . Instagram #instasad?: exploring associations among instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015; 18( 5): 247– 52. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ellison NB , Vitak J , Gray R , Lampe C . Cultivating social resources on social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2014; 19( 4): 855– 70. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kennison SM , Spooner VH . Childhood relationships with parents and attachment as predictors of resilience in young adults. J Fam Stud. 2023; 29( 1): 15– 27. doi:10.1080/13229400.2020.1861968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mecha P , Martin-Romero N , Sanchez-Lopez A . Associations between social support dimensions and resilience factors and pathways of influence in depression and anxiety rates in young adults. Span J Psychol. 2023; 26: e11. doi:10.1017/SJP.2023.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ungar M , Theron L , Murphy K , Jefferies P . Researching multisystemic resilience: a sample methodology. Front Psychol. 2021; 11: 607994. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Blessin M , Lehmann S , Kunzler AM , van Dick R , Lieb K . Resilience interventions conducted in western and eastern countries—a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19( 11): 6913. doi:10.3390/ijerph19116913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Panter-Brick C , Eggerman M . Understanding culture, resilience, and mental health: the production of hope. In: The social ecology of resilience. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2011. p. 369– 86. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Raghavan SS , Sandanapitchai P . Cultural predictors of resilience in a multinational sample of trauma survivors. Front Psychol. 2019; 10: 131. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Masten AS . Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Dev. 2014; 85( 1): 6– 20. doi:10.1111/cdev.12205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Willmott TJ , Pang B , Rundle-Thiele S , Badejo A . Weight management in young adults: systematic review of electronic health intervention components and outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2019; 21( 2): e10265. doi:10.2196/10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Arnett JJ . Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000; 55( 5): 469– 80. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. New First-Tier City Research Institute . City business attractiveness ranking released: Wuxi returns, Kunming falls out 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.datayicai.com/report/detail/1000009. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

33. Li Z . Psychological empowerment on social media: who are the empowered users? Public Relat Rev. 2016; 42( 1): 49– 59. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pagani M , Mirabello A . The influence of personal and social-interactive engagement in social TV web sites. Int J Electron Commer. 2011; 16( 2): 41– 68. doi:10.2753/JEC1086-4415160203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bai XJ , Liu X , Liu ZJ . The mediating effect of social comparison between achievement goals and academic self-efficacy in middle school students. Psychol Sci. 2013; 36( 6): 1413– 20. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Rozgonjuk D , Ryan T , Kuljus JK , Täht K , Scott GG . Social comparison orientation mediates the relationship between neuroticism and passive Facebook use. Cyberpsychol J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace. 2019; 13( 1): 2. doi:10.5817/cp2019-1-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Friborg O , Hjemdal O , Rosenvinge JH , Martinussen M . A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003; 12( 2): 65– 76. doi:10.1002/mpr.143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Spitzer RL , Kroenke K , Williams JBW , Löwe B . A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166( 10): 1092. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang F , Wu Y , Wang S , Du Z , Wu Y . Development of an optimal short form of the GAD-7 scale with cross-cultural generalizability based on Riskslim. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2024; 87: 33– 40. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2024.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wen LY , Shi LX , Zhu LJ , Zhou MJ , Hua L , Jin YL , et al. Associations between Chinese college students’ anxiety and depression: a chain mediation analysis. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 6): e0268773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang C , Wang T , Zeng P , Zhao M , Zhang G , Zhai S , et al. Reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the general anxiety disorder scale among Chinese medical university students. Front Psychiatry. 2021; 12: 648755. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.648755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hayes AF . Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018; 85( 1): 4– 40. doi:10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lai F , Wang L , Zhang J , Shan S , Chen J , Tian L . Relationship between social media use and social anxiety in college students: mediation effect of communication capacity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20( 4): 3657. doi:10.3390/ijerph20043657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Taylor Z , Yankouskaya A , Panourgia C . Social media use, loneliness and psychological distress in emerging adults. Behav Inf Technol. 2024; 43( 7): 1312– 25. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2023.2209797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Escobar-Viera CG , Shensa A , Bowman ND , Sidani JE , Knight J , James AE , et al. Passive and active social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018; 21( 7): 437– 43. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.0668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Koh GK , Ow Yong JQY , Lee ARYB , Ong BSY , Yau CE , Ho CSH , et al. Social media use and its impact on adults’ mental health and well-being: a scoping review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2024; 21( 4): 345– 94. doi:10.1111/wvn.12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Chiossi F , Haliburton L , Ou C , Butz AM , Schmidt A . Short-form videos degrade our capacity to retain intentions: effect of context switching on prospective memory. In: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2023 Apr 23–28; Hamburg, Germany. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 1– 15. doi:10.1145/3544548.3580778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ansari S , Iqbal N , Asif R , Hashim M , Farooqi SR , Alimoradi Z . Social media use and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2024; 27( 10): 704– 19. doi:10.1089/cyber.2024.0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Davis JL , Jurgenson N . Context collapse: theorizing context collusions and collisions. Inf Commun Soc. 2014; 17( 4): 476– 85. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2014.888458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Cingel DP , Carter MC , Krause HV . Social media and self-esteem. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022; 45: 101304. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Eslami M , Karahalios K , Sandvig C , Vaccaro K , Rickman A , Hamilton K , et al. First I “like” it, then I hide it: folk theories of social feeds. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2016 May 7–12; San Jose, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 2371– 82. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang W , Jiang F , Zhu Y , Zhang Q . Risks of passive use of social network sites in youth athletes: a moderated mediation analysis. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1219190. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1219190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Li Y . Upward social comparison and depression in social network settings: the roles of envy and self-efficacy. Internet Res. 2019; 29( 1): 46– 59. doi:10.1108/intr-09-2017-0358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Gross JJ . Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002; 39( 3): 281– 91. doi:10.1017/S0048577201393198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Papacharissi Z . Affective publics: sentiment, technology, and politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199999736.001.0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Morris AS , Silk JS , Steinberg L , Myers SS , Robinson LR . The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev. 2007; 16( 2): 361– 88. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Xin Y , Ren T , Chen X , Liu X , Wu Y , Jing S , et al. Understanding psychological symptoms among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 Omicron pandemic: findings from a national cross-sectional survey in 2023. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2024; 20: 100278. doi:10.1016/j.cpnec.2024.100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Purohit AK , Barev T , Schöbel S , Janson A , Holzer A . Designing for digital wellbeing on a smartphone: co-creation of digital nudges to mitigate instagram overuse. In: Bui TX , editor. Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2023); 2023 Jan 3–6; Maui, HI, USA. Honolulu, HI, USA: University of Hawai’i at Manoa; 2023. p. 4087– 96. doi:10.24251/hicss.2023.499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Schwarz N . Self-reports: how the questions shape the answers. Am Psychol. 1999; 54( 2): 93– 105. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.54.2.93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Orquin JL , Mueller Loose S . Attention and choice: a review on eye movements in decision making. Acta Psychol. 2013; 144( 1): 190– 206. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools