Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Specific Internet-Use Disorders among Indonesian College Students: Psychometric Evaluation of the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-Use Disorders (ACSID-11)

1 Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

2 Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, Population and Health Promotion, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

3 Department of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Padjadjaran, West Java, 45363, Indonesia

4 Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health Sciences, Christian University of Thailand, Nakhon Pathom, 73000, Thailand

5 Department of Educational Psychology and Counselling, Faculty of Education, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

6 Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511, USA

7 Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 Park St., New Haven, CT 06519, USA

8 Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, 100 Great Meadow Rd., Suite 704, Wethersfield, CT 06109, USA

9 Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine, 350 George St., New Haven, CT 06511, USA

10 Department of Neuroscience, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

11 Wu Tsai Institute, Yale University, 200 South Frontage Rd., SHM C-303, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

12 Institute of Allied Health Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

13 Biostatistics Consulting Center, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

14 School of Nursing, College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 807378, Taiwan

15 Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Siti Rahayu Nadhiroh. Email: ; Chung-Ying Lin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1847-1865. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072115

Received 19 August 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Problematic use of the internet (PUI) has been increasingly associated with various mental health issues, highlighting the need for accurate assessment tools. The Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorder (ACSID-11) is a validated psychometric instrument designed to measure distinct forms of PUI across multiple online activities. However, its applicability and validity have not yet been established within the Indonesian context. Therefore, this study aimed to translate and validate the ACSID-11 for use among Indonesian populations. Methods: The translation procedure of the ACSID-11 involved forward translation, back translation, and expert panel discussions. This research involved 600 undergraduate and post-graduate students from universities in Indonesia (mean [SD] age = 21.60 [2.74] years; 409 [68%] females). Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and McDonald’s Omega (ω) were used to measure the internal consistency of the ACSID-11. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used in testing the construct validity of the ACSID-11. Results: The ACSID-11 demonstrated validity and reliability in assessing different types of PUI in the present Indonesian sample (α = 0.67–0.96; ω = 0.68–0.96). The CFA results supported a four-factor structure for the Indonesian version of the ACSID-11. Conclusion: The findings suggest that the Indonesian version of the ACSID-11 is a valid and reliable tool for assessing specific forms of PUI among Indonesian students. Future research and clinical applications are encouraged to utilize the ACSID-11 for early identification, intervention, and prevention strategies targeting PUI within this population.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe digital era is characterized by technological advancements that have significantly enhanced various aspects of daily life [1]. Use of digital technologies is influencing people’s behaviors and cognitive processes, including among young individuals [2]. Internet use has become a prominent feature of modern societies, with college students using the internet extensively for social interactions, entertainment, and academic assignments [3]. While often beneficial, internet use may also lead to adverse outcomes such as mood disturbances, difficulties in controlling screen time, withdrawal symptoms when offline, reduced social interactions, decreased academic or work performance, and low self-esteem [4]. The mental health and functional consequences of problematic use of the internet use (PUI) are increasingly being recognized as a growing global public health concern [5].

PUI is a general term describing multiple potential activities that could be performed on the internet and may lead to concerns. However, considering that different online activities may have different impacts on people’s health, examining specific forms of PUI (e.g., gaming [6], shopping [7], pornography [8,9], social networking [10,11], and gambling [12]) separately may help better understand the health correlates of PUI.

PUI may be particularly relevant to Asia. Asia has a high prevalence of PUI, also referred to as internet use disorder, internet addiction, or problematic internet behaviors, particularly among teenagers and young adults [13]. A meta-analysis indicated that the regions with the highest prevalence of internet addiction included the Middle East (10.9%), North America (8.0%), and Asia (7.1%) [14]. Globally, Indonesia ranks fourth in internet usage, with approximately 64.8% of the population online. Internet use spans all age groups, but is especially prevalent among young adults, with 75.5% of individuals aged 18 to 25 years using the internet, particularly college students [15]. This widespread usage is supported by easy access, affordability, and the availability of diverse applications serving various purposes.

The Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11) is a psychometric tool developed to measure the severity of PUI across specific online activities, including gaming, shopping, pornography, social networking, and gambling [16]. The ACSID-11 is based on the diagnostic framework of the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) for gaming and gambling disorders. It provides a standardized approach for healthcare providers and researchers to assess various forms of PUI [17]. Developed through theoretical foundations and expert input, the ACSID-11 has been shown to exhibit a multifactorial structure involving four factors [17].

While several instruments have been developed to assess internet addiction, including specific tools like the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short Form (IGDS9-SF) and the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), these tools are limited to individual types of PUI. The IGDS9-SF evaluates Internet Gaming Disorder [18], while the BSMAS measures problematic use of social media [19]. In contrast, the ACSID-11 evaluates multiple forms of PUI simultaneously, considering both the intensity and frequency of use and aligning with ICD-11 diagnostic criteria [17]. Specifically, the ACSID-11 is a brief yet comprehensive screening instrument for assessing various forms of specific PUI in accordance with the ICD-11 criteria. Initially developed by Müller et al. [17], it has proven to be an appropriate, consistent, and efficient tool for evaluating symptoms related to online gaming, buying–shopping, pornography use, social networks use, and online gambling disorders/concerns. Subsequent validation studies have confirmed the reliability, validity, and cross-cultural applicability of the ACSID-11 across diverse populations. Oelker et al. [20] further demonstrated its robustness using a multi-trait–multi-method approach, while additional studies in Thailand [16], China [21], and in specific contexts such as Tinder and online pornography use [22] support its broad applicability. Collectively, these findings suggest that the ACSID-11 may be a reliable and versatile tool for both research and clinical practice.

In Indonesia, research investigating PUI has primarily relied on instruments such as the BSMAS, IGDS9-SF, and the Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS). However, these studies have limitations. For example, a study by Pramukti et al. [23] assessed social media and gaming-related PUI using the BSMAS and IGDS9-SF but did not evaluate other specific forms. Another study by Nurmala et al. [24] explored generalized PUI using the SABAS, without addressing specific types. Therefore, the ACSID-11 offers a valuable alternative by enabling a comprehensive assessment of multiple specific forms of PUI among Indonesian populations. Given this context, the present study aimed to translate the ACSID-11 into Indonesian and evaluate its psychometric properties among Indonesian young adult university students. Based on the initial study investigating the factor structure of the ACSID-11 [17], we hypothesized a four-factor (vs. one-factor) structure would be appropriate for the Indonesian ACSID-11.

This was a cross-sectional study recruiting university students including undergraduates and post-graduates from the public and private universities in Indonesia. Participants were recruited through online convenience sampling. A total of 600 university students participated with inclusion criteria of being an active student aged ≥18 years old studying in in Indonesia. Participants reported diverse majors at their universities. Data were collected using Google Forms, an online survey platform, and the present authors with Indonesian affiliations distributed the survey link to their students. Informed consent was provided in the questionnaire, and participants provided consent prior to data collection. To avoid having participants repeat the survey more than once, the participants were asked to login using their personal email address before the survey started. In addition, Google Forms was set to “limit to 1 response.”

The questionnaire asked about respondents’ age, sex, field of study, types of universities, average sleep over the past week, average outdoor activity over the past week, and average time playing games, using social media, and engaging in online learning over the past week.

2.2.2 Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-Use Disorders (ACSID-11)

The ACSID-11 is a brief measure assessing specific internet-use disorders via comprehensive concepts. It includes 11 items based on the ICD-11, covering the main diagnostic criteria: continuation/escalation (CE) of internet use despite negative consequences, increased priority (IP) given to online activities, and impaired control (IC) over online engagement. Each of these three domains is represented by three items. In addition, the questionnaire includes two further items assessing marked distress (MD) and functional impairment in daily life (FI) associated with individuals’ online activity.

Participants were asked to indicate (yes/no) whether they had engaged in specific online activities (i.e., other activities, gambling, social networking, pornography use, shopping, and online gaming) during the last 12 months. If “other” was endorsed, participants were instructed to specify the activity. For each endorsed activity, participants completed the ACSID-11 items. Subsequently, they rated the frequency of each symptom over the past 12 months (3 = often, 2 = sometimes, 1 = rarely, 0 = never). If they reported at least “rarely,” they were further asked to indicate the intensity of the experience (3 = intense, 2 = somewhat intense, 1 = somewhat not intense, 0 = not intense at all). Total scores are calculated by summing the frequency and intensity ratings for each endorsed activity, yielding a possible range of 0–33, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity for the specific online activity [17]. The original version demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.90 to 0.95 for frequency ratings and 0.89 to 0.94 for intensity ratings [17]. In the present study, the ACSID-11 showed acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.68 to 0.94 for frequency ratings and 0.67 to 0.94 for intensity ratings.

This research is a cross-sectional study translating and validating the ACSID-11 into Indonesian. The study period was from April to July 2023. Data collection was performed by creating an online survey link using Google Forms. Convenience sampling used the following procedures. First, we shared links on social media (for example, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp). Second, interested participants gave informed consent. Specifically, before participants began the survey, they received information about the study (e.g., research aims and inclusion criteria), including the right to withdraw at any time. Then they were required to provide electronic informed consent before continuing. Finally, participants were asked to click the “agree” icon if they wanted to continue the online survey. This survey questionnaire collected data regarding information on participant characteristics and the ACSID-11.

This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (Approval No. 2756-KEPK).

The ACSID-11 was translated from English to Indonesian. The ACSID-11 translation process used procedures and guidelines from [25]. The detailed translation procedure is described in Supplementary Materials. In brief, we used the following steps to ensure the linguistic validity of translation: (i) Translation team recruitment; (ii) forward translation (Supplementary Table S1); (iii) back translation (Supplementary Table S2); (iv) committee consolidation; (v) pilot testing and finalization.

Data were analyzed using Jeffrey’s Amazing Statistics Program (JASP) 2023. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the participants’ demographic information and to explore distributions of all ACSID-11 items. Reliability was assessed using internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients) and item-total correlation. The cut-off points of 0.7 (for both Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω) and 0.4 (for item-total correlation) were used to indicate acceptable internal consistency [26]. Moreover, we derived the factor loadings from the structure that fit the best with the data (i.e., the one-factor or the four-factor structure) in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the cut-off point of 0.4 indicated acceptable factor loadings [27]. CFA was used to examine the construct validity of the ACSID-11 (i.e., if the Indonesian ACSID-11 fit better with a one-factor structure or a four-factor structure) using Diagonally Weighted least Squares (DWLS) estimation. The fit indices and corresponding cut-off points used to indicate goodness of model fit included non-significant χ2 comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.09, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.09, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 McDonald’s ω [19].

The participants’ mean age was 21.60 years (standard deviation [SD] = 2.74, range = 18–55). Most were female (68%), undergraduate students (94%) and from state universities (87.7%), and the field of study was predominantly in the Professional and Applied Sciences (52.2%). Participants spent on average 3.6 (SD = 4.31) hours/day gaming and 5.02 (SD = 3.73) hours/day using social media. Regarding participants’ specific online activities, most engaged in gaming (n = 536), online shopping (n = 593), and social networks use (n = 600), with fewer reporting online pornography use (n = 164) and online gambling (n = 79) (Table 1). In item analyses, all ACSID-11 items demonstrated low mean (SD), skewness and kurtosis values for all specific online activities (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 1: The basic information of the 600 participants.

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.60 (2.74) | - |

| Sex | ||

| Male | - | 191 (32%) |

| Female | - | 409 (68%) |

| Types of Universities | ||

| Public University | - | 526 (87.7%) |

| Private University | - | 74 (12.3%) |

| Field of Study | ||

| Natural Sciences | - | 22 (3,7%) |

| Formal Sciences | - | 30 (5%) |

| Humanities | - | 46 (7.7%) |

| Religious Studies | - | 4 (0.7%) |

| Social Sciences | - | 185 (30.8%) |

| Professional and Applies Sciences | - | 313 (52.2%) |

| Student status | ||

| Undergraduate | - | 565 (94%) |

| Postgraduate | - | 35 (6%) |

| Daily hours spent gaming | 3.6 (4.31) | - |

| Daily hours using social media | 5.02 (3.73) | |

| ACSID-11 (Behaviors) | ||

| Online gaming | 536 (89%) | |

| Online shopping | 593 (99%) | |

| Online pornography | 164 (27%) | |

| Social networks use | 600 (100%) | |

| Online gambling | 79 (13%) |

All responses to questions assessing frequency and intensity of online gaming displayed factor loadings and item-total correlations above 0.4 and presented low mean (SD), skewness and kurtosis values (Table 2). Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values were more than 0.7 for both frequency rating and intensity ratings, ranging from 0.80–0.94 for frequency and 0.83–0.96 for intensity.

Table 2: Item-level of the psychometric properties for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11): online gaming.

| Item | Frequency Rating | Intensity Rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | |

| AC-IC | 0.866 | 0.863 | 0.900 | 0.901 | ||||||||||

| Item 1 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 1.90 (1.18) | −0.53 | −1.26 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.72 (1.22) | −0.29 | −1.52 | ||||

| Item 2 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 1.94 (1.17) | −0.64 | −1.12 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 1.77 (1.22) | −0.40 | −1.44 | ||||

| Item 3 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 1.77 (1.21) | −0.37 | −1.44 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 1.73 (1.24) | −0.32 | −1.53 | ||||

| AC-IP | 0.922 | 0.927 | 0.943 | 0.945 | ||||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 1.75 (1.20) | −0.38 | −1.40 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 1.65 (1.24) | −0.25 | −1.56 | ||||

| Item 5 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 1.60 (1.22) | −0.19 | −1.54 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 1.55 (1.26) | −0.11 | −1.63 | ||||

| Item 6 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 1.63 (1.22) | −0.20 | −1.54 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 1.53 (1.25) | −0.08 | −1.63 | ||||

| AC-CE | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.955 | 0.955 | ||||||||||

| Item 7 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.52 (1.26) | −0.04 | −1.65 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.50 (1.28) | −0.04 | −1.69 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 1.49 (1.25) | −0.003 | −1.63 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.44 (1.28) | 0.06 | −1.69 | ||||

| Item 9 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 1.53 (1.27) | −0.07 | −1.66 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.43 (1.28) | 0.06 | −1.68 | ||||

| AC-FI | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.831 | 0.831 | ||||||||||

| Item 10 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 1.73 (1.20) | −0.32 | −1.44 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1.69 (1.24) | −0.27 | −1.54 | ||||

| Item 11 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1.31 (1.27) | 0.22 | −1.64 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1.25 (1.28) | 0.30 | −1.63 | ||||

Factor loadings and item-total correlations for each question item relating to online shopping frequency and intensity demonstrated values higher than 0.4 (Table 3). All items presented low mean (SD), skewness and kurtosis values. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values were more than 0.6 for both frequency rating and intensity ratings, ranging from 0.73–0.91 for frequency and 0.67–0.92 for intensity.

Factor loadings and item-total correlations for online pornography use frequency and intensity demonstrated values higher than 0.4 (Table 4). All items presented low mean (SD) and skewness values. However, high values of kurtosis in intensity ratings were observed. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω were more than 0.7 for both frequency rating and intensity ratings, ranging from 0.87–0.95 for frequency and 0.85–0.94 for intensity.

Factor loadings and item-total correlations were higher than 0.4 for the use of social media (Table 5). All items presented low mean (SD), skewness, and kurtosis values. Cronbach’s α ranged between 0.68–0.90 for frequency and 0.68–0.91 for intensity. McDonald’s ω values ranged from 0.69–0.90 for frequency and 0.69–0.91 for intensity.

Factor loadings and item-total correlations were higher than 0.4 for online gambling (Table 6). All items presented low mean (SD) and high values of skewness and kurtosis for both frequency and intensity ratings. Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.83–0.92 for frequency and 0.81–0.93 for intensity. McDonald’s ω ranged from 0.85–0.92 for frequency and 0.82–0.93 for intensity.

Indexes of fit in the CFA of the ACSID-11 indicated the suitability of a four-factor model for both frequency and intensity of use (Table 7). CFI values ranged from 0.967 to 0.988, TLI values from 0.952 to 0.975, RMSEA values from 0.072 to 0.088, and SRMR values from 0.019 to 0.042, with the exception of the frequency rating for online gambling (CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.928, RMSEA = 0.138, SRMR = 0.042).

Table 8 shows intercorrelations among the total scores for the specific online activities. For frequency ratings, the intercorrelations among the five specific online activities were largely all positive and significant, with coefficients ranging from r = 0.11 (p < 0.01) to 0.54 (p < 0.001). The strongest correlation was observed between online gaming and online shopping (r = 0.54, p < 0.001), while the weakest significant association was between online shopping and online pornography use (r = 0.11, p < 0.01). However, there were no significant correlations between online shopping and online gambling (r = 0.08, p = 0.054) or social network use and online gambling (r = 0.07, p = 0.072).

Table 3: Item-level of the psychometric properties for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11): online shopping.

| Item | Frequency Rating | Intensity Rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | Factor loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | |

| AC-IC | 0.733 | 0.734 | 0.741 | 0.732 | ||||||||||

| Item 1 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.77 (0.88) | −0.35 | −0.53 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 1.65 (0.89) | −0.21 | −0.67 | ||||

| Item 2 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 1.69 (0.97) | −0.26 | −0.89 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 1.63 (0.93) | −0.20 | −0.80 | ||||

| Item 3 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 1.55 (0.96) | −0.14 | −0.92 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 1.53 (0.94) | −0.17 | −0.87 | ||||

| AC-IP | 0.835 | 0.836 | 0.858 | 0.860 | ||||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 1.38 (0.96) | −0.01 | −0.99 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 1.36 (0.97) | 0.04 | −1.01 | ||||

| Item 5 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 1.20 (0.98) | 0.19 | −1.09 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 1.25 (0.98) | 0.11 | −1.10 | ||||

| Item 6 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 1.24 (1.00) | 0.18 | −1.13 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 1.23 (0.97) | 0.16 | −1.07 | ||||

| AC-CE | 0.910 | 0.911 | 0.923 | 0.924 | ||||||||||

| Item 7 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.18 (1.01) | 0.28 | −1.08 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 1.15 (0.99) | 0.21 | −1.18 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 1.12 (1.01) | 0.35 | −1.10 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 1.10 (1.00) | 0.32 | −1.15 | ||||

| Item 9 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.09 (1.01) | 0.34 | −1.15 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 1.10 (1.01) | 0.34 | −1.16 | ||||

| AC-FI | 0.731 | 0.733 | 0.669 | 0.675 | ||||||||||

| Item 10 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 1.45 (0.96) | −0.02 | −0.96 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 1.42 (0.96) | −0.01 | −0.95 | ||||

| Item 11 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 1.02 (1.00) | 0.47 | −1.02 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 1.04 (1.02) | 0.41 | −1.15 | ||||

Table 4: Item-level of the psychometric properties for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11): online pornography use.

| Item | Frequency Rating | Intensity Rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Factor Loadings | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | *Factor Loadings | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | |

| AC-IC | 0.918 | 0.911 | 0.921 | 0.918 | ||||||||||

| Item 1 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.65 (0.89) | −0.21 | −0.67 | 0.910 | 0.86 | 0.32 (0.73) | 2.40 | 4.98 | ||||

| Item 2 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 1.63 (0.93) | −0.20 | −0.80 | 0.880 | 0.83 | 0.44 (0.92) | 1.94 | 2.30 | ||||

| Item 3 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.53 (0.94) | −0.17 | −0.87 | 0.898 | 0.85 | 0.40 (0.86) | 2.02 | 2.72 | ||||

| AC-IP | 0.920 | 0.916 | 0.924 | 0.923 | ||||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 1.36 (0.97) | 0.04 | −1.01 | 0.873 | 0.86 | 0.29 (0.72) | 2.48 | 5.20 | ||||

| Item 5 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 1.25 (0.98) | 0.11 | −1.10 | 0.911 | 0.89 | 0.34 (0.80) | 2.33 | 4.29 | ||||

| Item 6 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 1.23 (0.97) | 0.16 | −1.07 | 0.901 | 0.88 | 0.32 (0.77) | 2.43 | 4.80 | ||||

| AC-CE | 0.952 | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.942 | ||||||||||

| Item 7 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.15 (0.99) | 0.21 | −1.18 | 0.914 | 0.84 | 0.25 (0.68) | 2.82 | 7.21 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.10 (1.00) | 0.32 | −1.15 | 0.922 | 0.85 | 0.24 (0.66) | 2.81 | 7.15 | ||||

| Item 9 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.09 (1.01) | 0.34 | −1.16 | 0.924 | 0.85 | 0.28 (0.71) | 2.65 | 6.19 | ||||

| AC-FI | 0.869 | 0.869 | 0.854 | 0.854 | ||||||||||

| Item10 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 1.42 (0.96) | −0.01 | −0.95 | 0.866 | 0.86 | 0.33 (0.77) | 2.35 | 4.46 | ||||

| Item11 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 1.04 (1.02) | 0.41 | −1.15 | 0.860 | 0.86 | 0.33 (0.79) | 2.41 | 4.70 | ||||

Table 5: Item-level of the psychometric properties for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11): social networks use.

| Item | Frequency Rating | Intensity Rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | |

| AC-IC | 0.706 | 0.718 | 0.771 | 0.777 | ||||||||||

| Item 1 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 2.24 (0.92) | −0.99 | −0.02 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 2.16 (0.89) | −0.88 | −0.02 | ||||

| Item 2 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 2.00 (1.00) | −0.65 | −0.70 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 1.98 (0.98) | −0.64 | −0.62 | ||||

| Item 3 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.85 (1.03) | −0.48 | −0.91 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 1.85 (1.01) | −0.46 | −0.88 | ||||

| AC-IP | 0.826 | 0.834 | 0.844 | 0.849 | ||||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 1.85 (1.01) | −0.46 | −0.90 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 1.86 (1.01) | −0.48 | −0.87 | ||||

| Item 5 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 1.68 (1.08) | −0.26 | −1.20 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 1.65 (1.05) | −0.22 | −1.16 | ||||

| Item 6 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 1.65 (1.08) | −0.23 | −1.21 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 1.61 (1.08) | −0.18 | −1.24 | ||||

| AC-CE | 0.897 | 0.898 | 0.914 | 0.915 | ||||||||||

| Item 7 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 1.53 (1.12) | −0.07 | −1.35 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.52 (1.12) | −0.08 | −1.36 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.48 (1.13) | −0.02 | −1.38 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.45 (1.12) | −0.004 | −1.36 | ||||

| Item 9 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 1.47 (1.12) | −0.01 | −1.36 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.43 (1.11) | 0.04 | −1.35 | ||||

| AC-FI | 0.683 | 0.686 | 0.683 | 0.692 | ||||||||||

| Item 10 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 1.86 (1.05) | −0.43 | −1.04 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 1.85 (1.01) | −0.42 | −0.95 | ||||

| Item 11 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 1.34 (1.15) | 0.14 | −1.44 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 1.31 (1.17) | 0.17 | −1.47 | ||||

Table 6: Item-level of the psychometric properties for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11): online gambling.

| Item | Frequency Rating | Intensity Rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | Factor Loadings* | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | |

| AC-IC | 0.902 | 0.899 | 0.885 | 0.856 | ||||||||||

| Item 1 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.16 (0.56) | 3.76 | 13.74 | 0.901 | 0.85 | 0.13 (0.46) | 4.22 | 19.18 | ||||

| Item 2 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.20 (0.66) | 3.53 | 11.48 | 0.804 | 0.76 | 0.22 (0.69) | 3.26 | 9.45 | ||||

| Item 3 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.17 (0.59) | 3.87 | 14.45 | 0.853 | 0.80 | 0.19 (0.63) | 3.45 | 10.94 | ||||

| AC-IP | 0.880 | 0.856 | 0.929 | 0.928 | ||||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.11 (0.45) | 4.48 | 20.53 | 0.868 | 0.84 | 0.11 (0.44) | 4.20 | 17.96 | ||||

| Item 5 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.16 (0.58) | 3.93 | 15.05 | 0.926 | 0.89 | 1.15 (0.53) | 3.95 | 15.52 | ||||

| Item 6 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.15 (0.55) | 4.12 | 16.72 | 0.914 | 0.87 | 0.14 (0.52) | 4.24 | 17.97 | ||||

| AC-CE | 0.951 | 0.953 | 0.916 | 0.916 | ||||||||||

| Item 7 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.13 (0.52) | 4.48 | 19.99 | 0.879 | 0.79 | 0.01 (0.41) | 4.82 | 24.58 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.11 (0.46) | 4.78 | 23.84 | 0.871 | 0.78 | 0.09 (0.41) | 5.08 | 26.73 | ||||

| Item 9 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.11 (0.44) | 4.70 | 23.05 | 0.908 | 0.81 | 0.11 (0.46) | 4.65 | 22.17 | ||||

| AC-FI | 0.832 | 0.859 | 0.813 | 0.823 | ||||||||||

| Item10 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.11 (0.46) | 4.65 | 22.54 | 0.855 | 0.86 | 0.16 (0.56) | 3.76 | 13.74 | ||||

| Item11 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.16 (0.60) | 3.95 | 14.85 | 0.812 | 0.82 | 0.12 (0.47) | 4.40 | 19.85 | ||||

Table 7: Confirmatory factor analysis fitness for the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11).

| Domain | Frequency | Intensity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df) | p-Value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90%CI) | SRMR | χ2 (df) | p-Value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | |

| One-factor | ||||||||||||

| Online gaming | 145.46 (44) | <0.001 | 0.996 | 0.994 | 0.062 (0.051,0.074) | 0.054 | 147.31 (44) | <0.001 | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.063 (0.052,0.074) | 0.050 |

| Online shopping | 182.86 (44) | <0.001 | 0.983 | 0.978 | 0.073 (0.062,0.084) | 0.073 | 189.71 (44) | <0.001 | 0.983 | 0.979 | 0.075 (0.064,0.086) | 0.076 |

| Online pornography use | 36.04 (44) | 0.798 | 1.000 | 1.002 | 0.000 (0.000,0.019) | 0.063 | 20.39 (44) | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.007 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.050 |

| Social networks use | 181.75 (44) | <0.001 | 0.983 | 0.979 | 0.073 (0.062,0.084) | 0.074 | 198.61 (44) | <0.001 | 0.983 | 0.979 | 0.077 (0.066,0.088) | 0.078 |

| Online gambling | 21.26 (44) | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.020 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.086 | 11.39 (44) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.029 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.058 |

| Four-factor | ||||||||||||

| Online gaming | 48.38 (38) | 0.121 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.021 (0.000,0.038) | 0.031 | 45.99 (38) | 0.175 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.019 (0.000,0.036) | 0.028 |

| Online shopping | 42.65 (38) | 0.278 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.014 (0.000,0.033) | 0.035 | 46.43 (38) | 0.164 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.019 (0.000,0.036) | 0.037 |

| Online pornography use | 14.30 (38) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.008 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.040 | 10.50 (38) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.010 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.035 |

| Social networks use | 35.28 (38) | 0.596 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 (0.000,0.026) | 0.031 | 35.22 (38) | 0.599 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 (0.000,0.026) | 0.031 |

| Online gambling | 13.06 (38) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.026 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.068 | 5.83 (38) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.033 | 0.000 (0.000,0.000) | 0.041 |

Table 8: Intercorrelations between the total scores for specific online activities of the ACSID-11.

| Domain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | |||||

| Online gaming | - | ||||

| Online shopping | 0.54*** | - | |||

| Online pornography use | 0.26*** | 0.11** | - | ||

| Social network use | 0.51*** | 0.64*** | 0.23*** | - | |

| Online gambling | 0.17*** | 0.08 (0.054) | 0.39*** | 0.07 (0.072) | - |

| Intensity | |||||

| Online gaming | - | ||||

| Online shopping | 0.54*** | - | |||

| Online pornography use | 0.27*** | 0.12*** | - | ||

| Social network use | 0.49*** | 0.63*** | 0.23*** | - | |

| Online gambling | 0.14*** | 0.08 (0.053) | 0.23*** | 0.05 (0.197) | - |

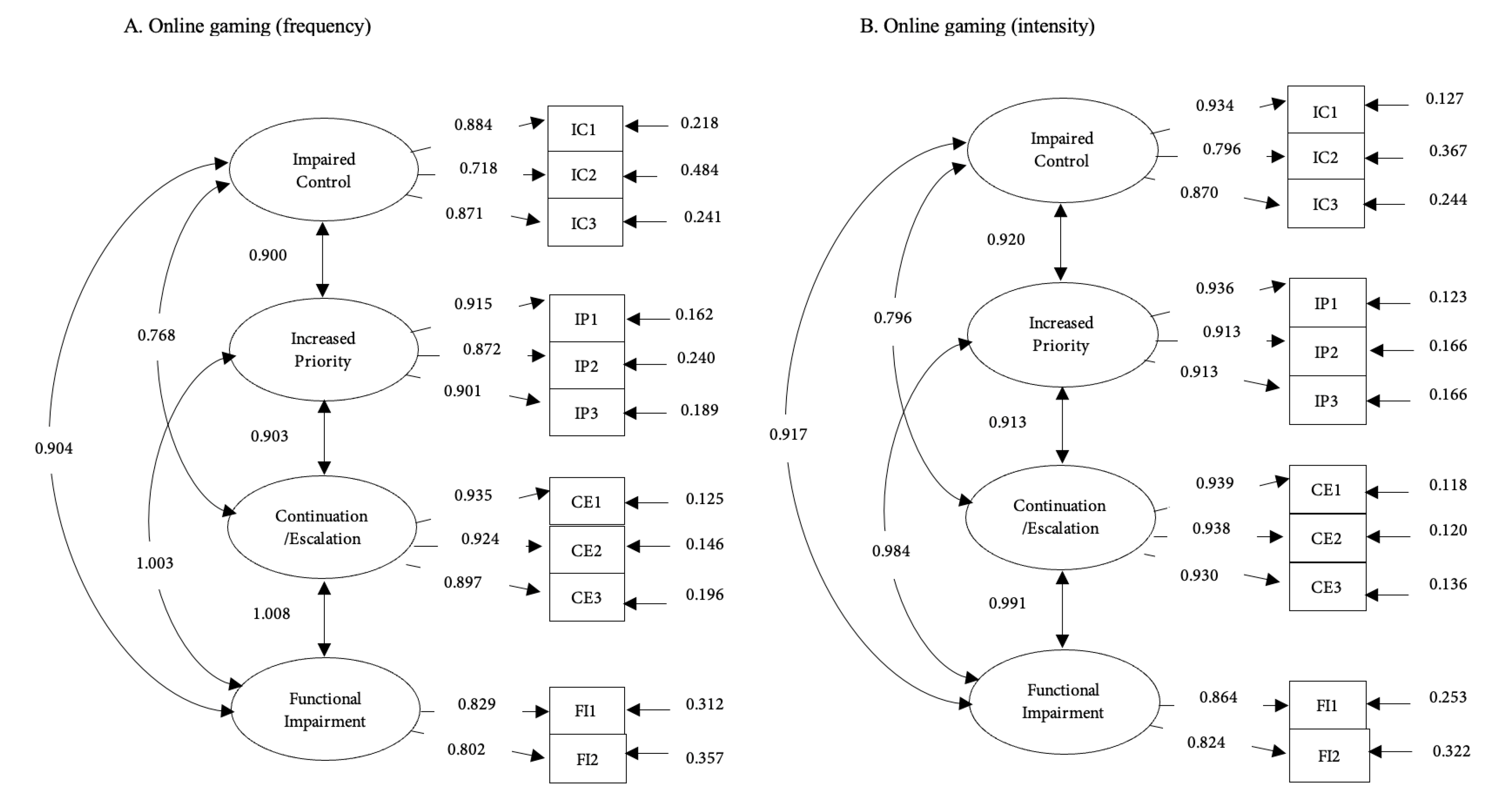

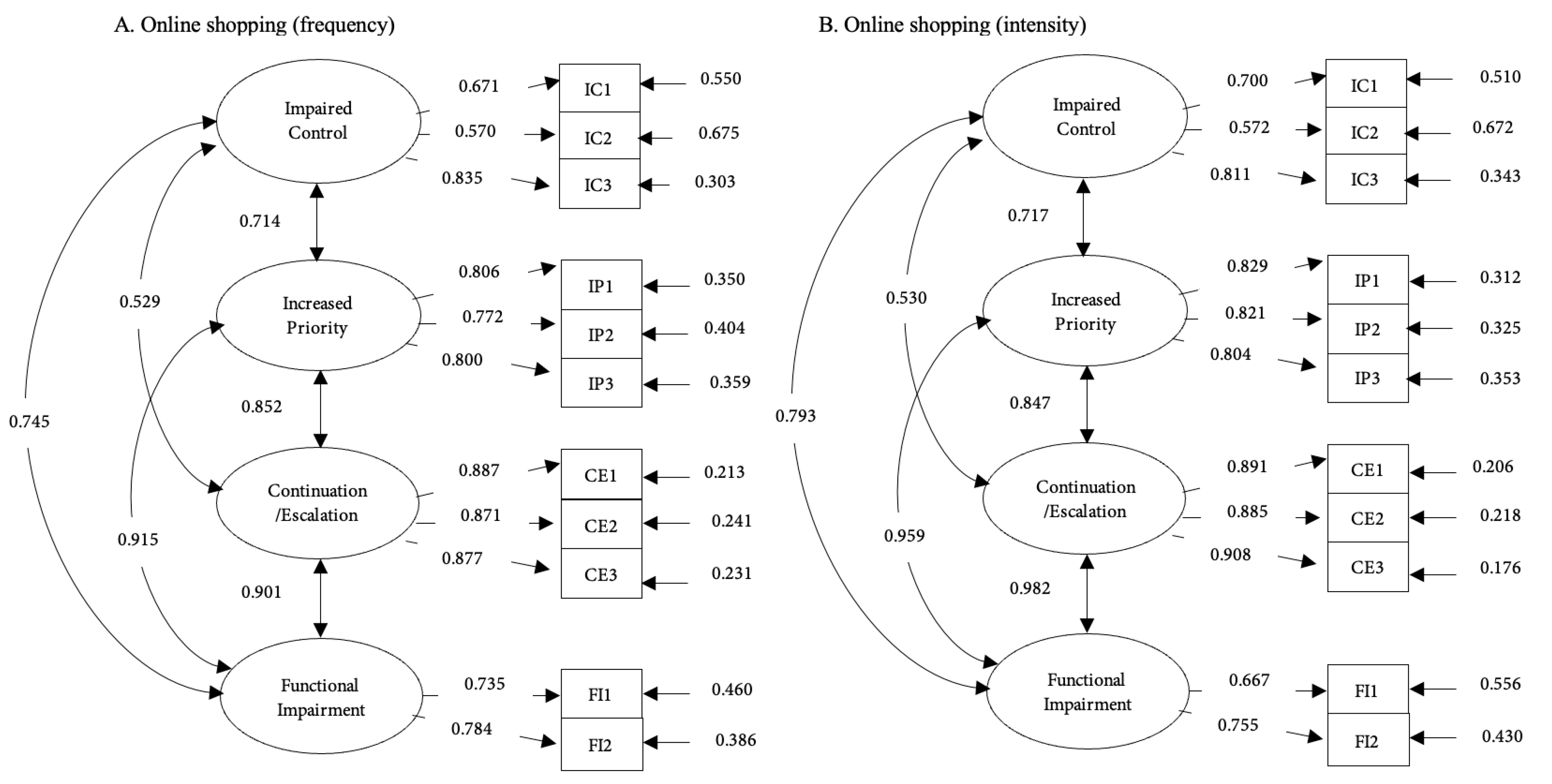

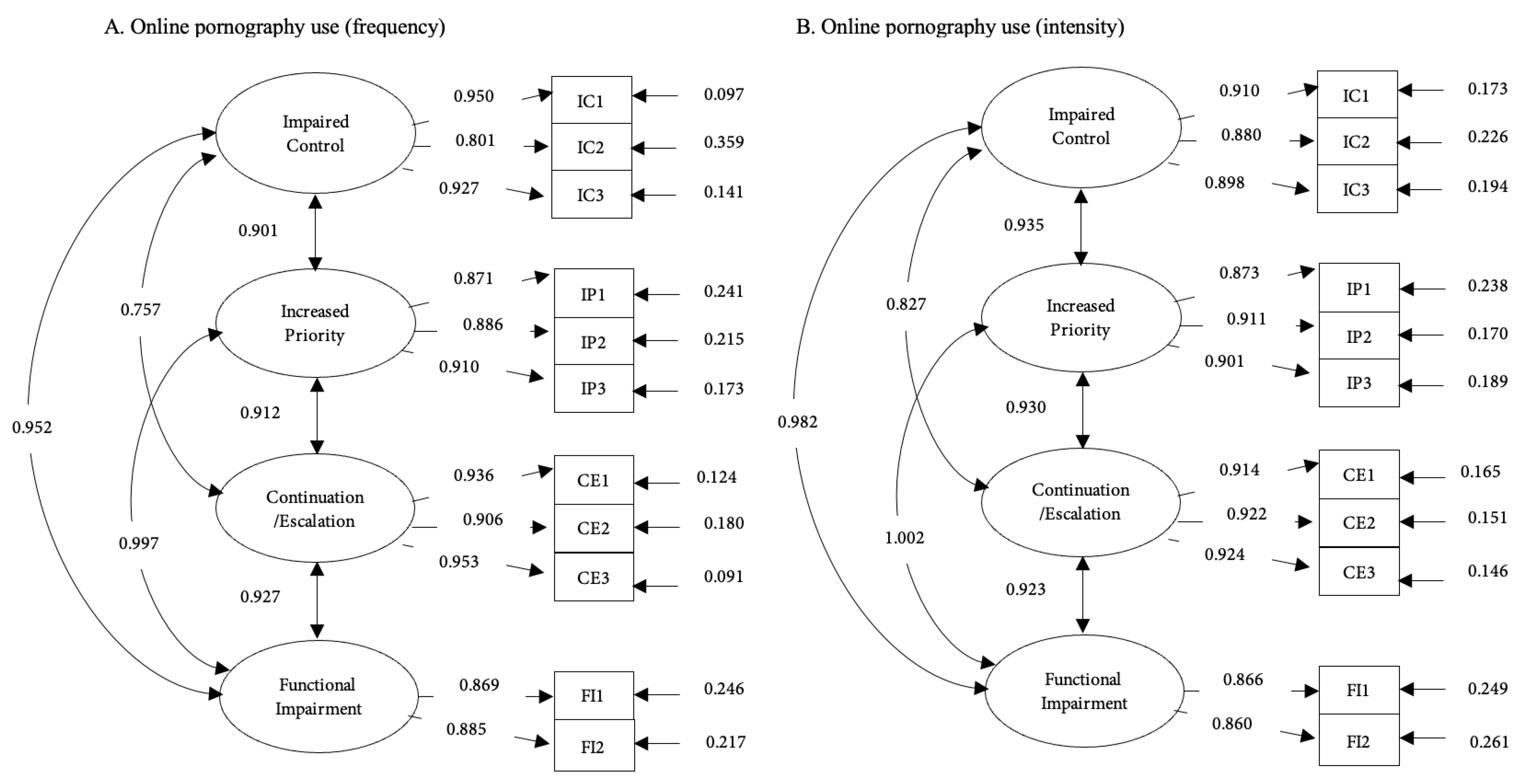

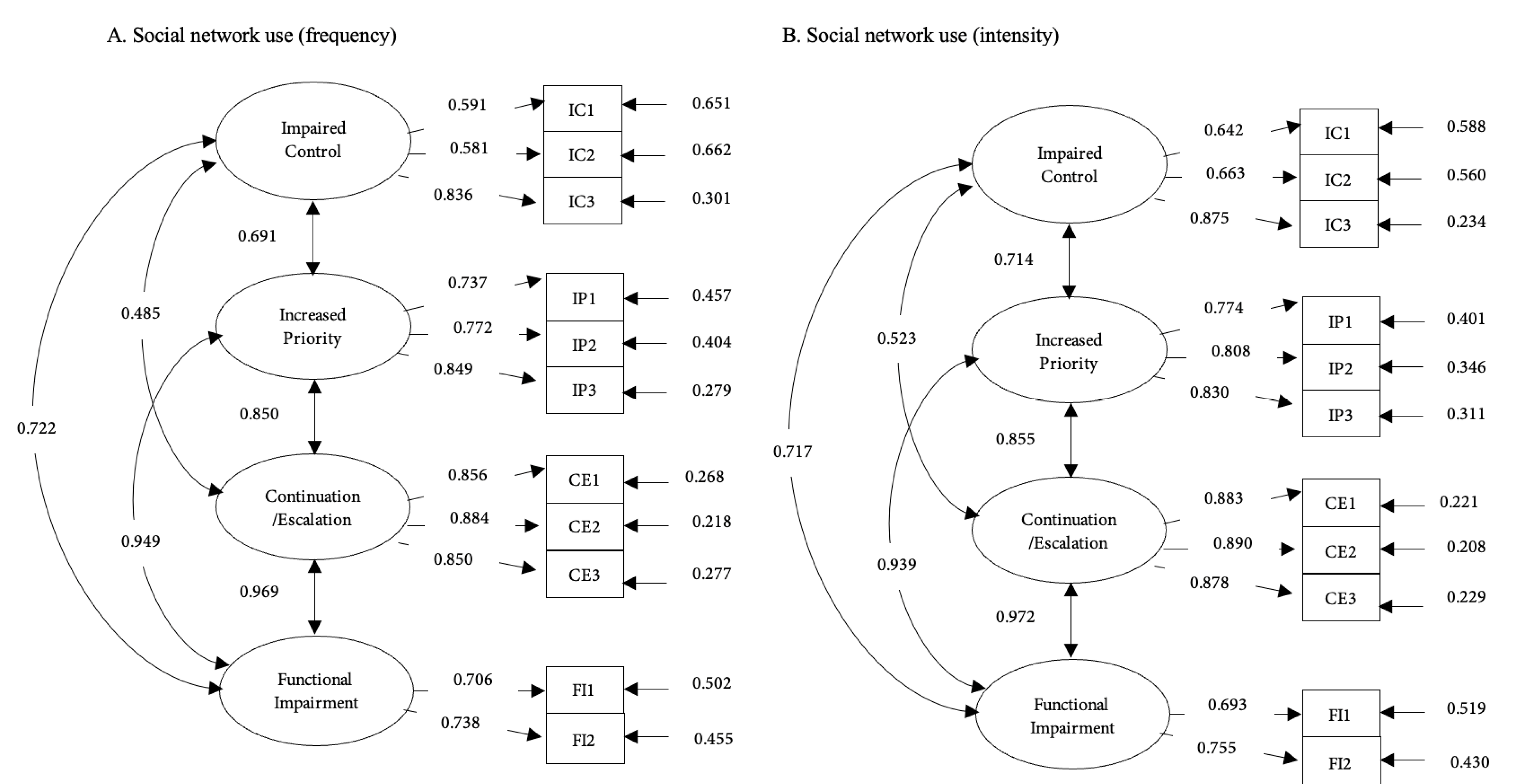

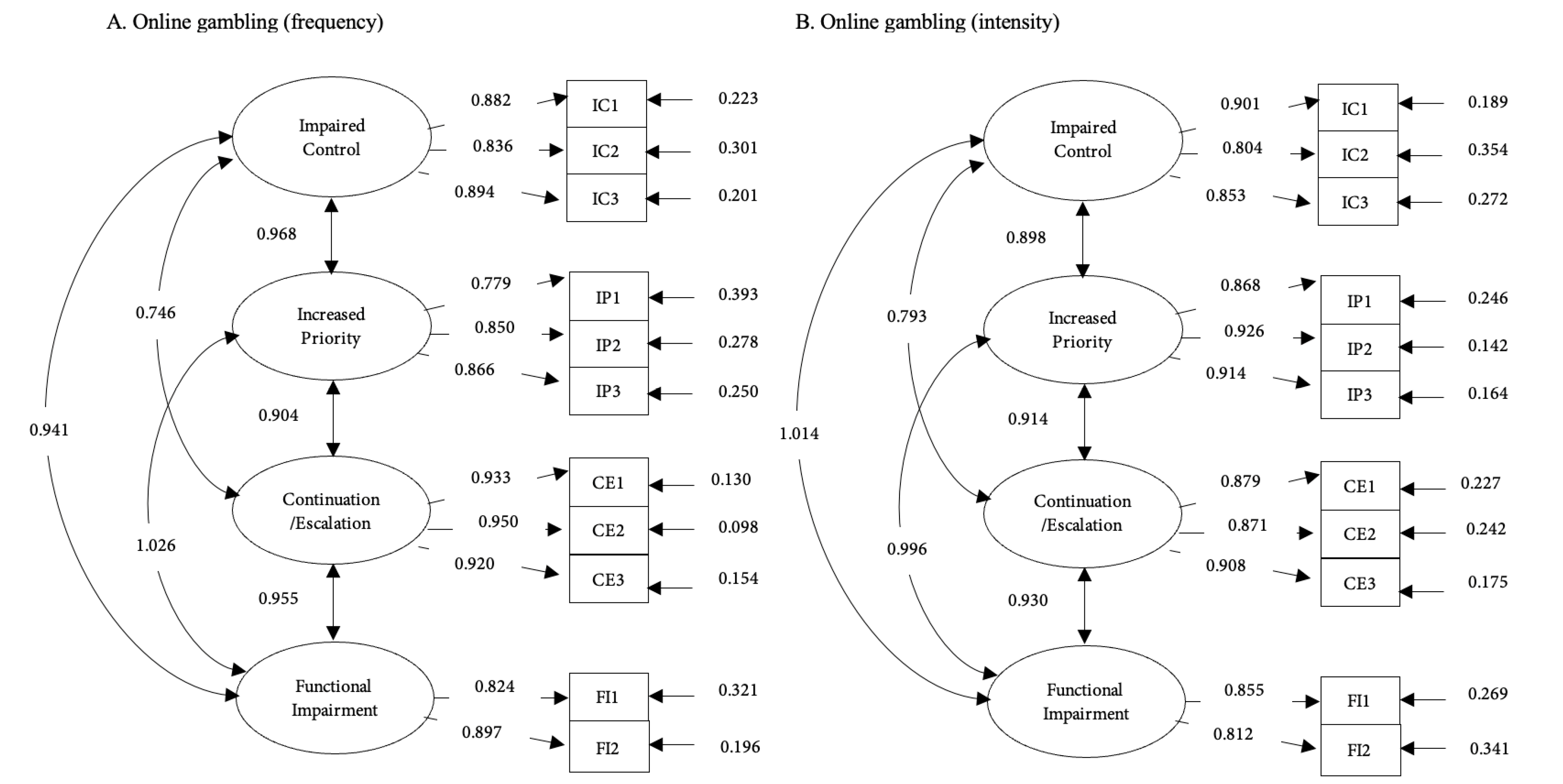

For intensity ratings, the intercorrelations among the five specific online activities were largely all positive and significant, with coefficients ranging from r = 0.12 (p < 0.001) to 0.54 (p < 0.001). The strongest correlation was observed between online gaming and online shopping (r = 0.54, p < 0.001), while the weakest significant association was between online shopping and online pornography use (r = 0.12, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant correlations between online shopping and online gambling (r = 0.08, p = 0.053) or social network use and online gambling (r = 0.05, p = 0.197). Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 present latent correlations of the four ACSID-11 factors and item factor loadings for both frequency and intensity.

Figure 1: Latent correlations of the four factors and item factor loadings for ACSID-11 online gaming, considering both frequency and intensity. (A) Online gaming (frequency); (B) Online gaming (intensity). Note: Values show factor correlations, standardized factor loadings, and residual covariances. Abbreviations: FI, functional impairment; CE, continuation/escalation; IP, increased priority; IC, impaired control.

Figure 2: Latent correlations of the four factors and item factor loadings for ACSID-11 for online shopping, considering both frequency and intensity. (A) Online shopping (frequency); (B) Online shopping (intensity). Note: Values show factor correlations, standardized factor loadings, and residual covariances. Abbreviations: FI, functional impairment; CE, continuation/escalation; IP, increased priority; IC, impaired control.

Figure 3: Latent correlations of the four factors and item factor loadings for ACSID-11 for online pornography use, considering both frequency and intensity. (A) Online pornography use (frequency); (B) Online pornography use (intensity). Note: Values show factor correlations, standardized factor loadings, and residual covariances. Abbreviations: FI, functional impairment; CE, continuation/escalation; IP, increased priority; IC, impaired control.

Figure 4: Latent correlations of the four factors and item factor loadings for ACSID-11 for social networks use, considering both frequency and intensity. (A) Social network use (frequency); (B) Social network use (intensity). Note: Values show factor correlations, standardized factor loadings, and residual covariances. Abbreviations: FI, functional impairment; CE, continuation/escalation; IP, increased priority; IC, impaired control.

Figure 5: Latent correlations of the four factors and item factor loadings for ACSID-11 for online gambling, considering both frequency and intensity. (A) Online gambling (frequency); (B) Online gambling (intensity). Note: Values show factor correlations, standardized factor loadings, and residual covariances. Abbreviations: FI, functional impairment; CE, continuation/escalation; IP, increased priority; IC, impaired control.

This study tested the psychometric properties of an Indonesian version of the ACSID-11. The study conducted translation and validation using cross-cultural methods. Systematic translation was performed using a standardized method [25], and this translation method was applied to ensure the linguistic validity of the Indonesian version of the ACSID-11. Next, the psychometric properties (aspects of construct validity) were examined among active college students in Indonesia. The ACSID-11 was developed based on the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for internet use disorders and concerns [17]. Internet use disorders and concerns may generate considerable adverse consequences, including in the domains of obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity and depression, anxiety, and global severity index [4]. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω results showed that the Indonesian ACSID-11 had good internal consistency, and the CFA indicated that the Indonesian ACSID-11 had a four-factor structure, agreeing with a previously reported factor structure of the ACSID-11 [17]. Similar to the present study’s findings, Yang et al. [16] conducted research on a student population in Thailand, showing that the four-factor structure model was adequate. Additionally, the promising psychometric results in this study support the use of the ACSID-11 to assess various types of internet addiction among Indonesian young adults, especially college students.

The reliability of the Indonesian ACSID-11 showed reliable results: both α and ω were ≥0.6, with some values close to 1 [28]. Considering α and ω coefficients range between 0 and 1, a value ≥ 0.7 has been suggested as demonstrating reliability [25,26]. However, based on Souza et al. [29], a research instrument is considered to be reliable if the Cronbach’s α value is >0.60. Thus, the Indonesian ACSID-11 may be considered reliable using the less stringent criteria. These results align with the original ACSID-11 [17], with Cronbach’s α similar to those in the current study (≥0.6). One possible reason for some low internal consistency values may involve the translation not precisely capturing the original meanings, even though standardized translation procedures were applied to help ensure scale items’ linguistic validity. As a result, translated scales may have internal consistency values lower than the original versions, as described elsewhere [19]. The Thai ACSID-11 also found low internal consistency in some domains [16]. However, other possible reasons for the relatively low Cronbach’s α (i.e., below 0.7) include the relatively few item numbers (i.e., each ACSID-11 domain contains only two or three items) and the relatively few participants engaging in some online activities (e.g., only 79 participants reported online gambling) [30].

Online gambling results may have been less satisfactory given the relatively small number of participants who reported engaging in online gambling (n = 79), similar to the results of the validation study of the Thai ACSID-11 [16]. The small number of participants may reflect the Indonesian prohibition of online gambling and its categorization as a criminal offense. Indonesia is also inhabited by mostly Muslims whose religion prohibits gambling. However, the prevalence of online gambling in Indonesia appears to be increasing. Therefore, further studies are needed with larger samples of individuals who gamble online to validate specific internet activities assessed with the ACSID-11.

The ACSID-11 assesses the domains of impaired control (IC), increased priority on online activities (IP), and continuation/escalation (CE) of internet use despite negative impacts, each of which is represented by three items. In addition, the questionnaire consists of two further items measuring functional impairment in daily life (FI) and marked distress (MD) due to online activities. The ACSID-11 instrument also considers intensity and frequency. The ACSID-11 offers practical value but requires completion of all 11 items for each relevant online activity, increasing participant burden compared with shorter, behavior-specific scales. The ACSID-11 provides a consistent, multi-dimensional assessment aligned with the ICD-11 framework, enabling cross-domain comparisons and identifying co-occurring problematic behaviors often missed by single-behavior instruments. Although more time-intensive, its capacity for standardized and holistic assessment offers significant added value for both clinical assessment and research applications.

Additionally, the ACSID-11 employs a dual-rating system assessing both the frequency and intensity of symptoms, which has important practical implications. Frequency reflects how often a symptom occurs, capturing the behavioral regularity of forms of PUI. On the other hand, intensity may reflect more the subjective severity or distress experienced. Separating the frequency and intensity of self-reported symptoms offers important insights into individuals’ daily health experiences [31]. This approach enables a more nuanced understanding of an individual’s PUI profile. For example, one person may demonstrate high-frequency but low-intensity behaviors (e.g., frequent yet mild social-media checking), while another may show low-frequency but high-intensity patterns (e.g., rare but severe gaming binges). Such distinctions may guide tailored interventions and support future research regarding which dimension may better predict adverse consequences or differentiates PUI subtypes.

PUI, generally and for specific purposes (e.g., social media use), often differs by age, sex and geographic region [32]. Findings suggest that internet use disorders may become more prevalent over time, with factors such as individualism, sociability, enculturation, and others warranting consideration as potentially moderating factors. Therefore, it is important to conduct more detailed studies into the possible consequences of increasing digitalization [33]. Specifically, future studies could further examine the validity of the Indonesian ACSID-11. The CFA conducted in the present study represents a first step in a validation process, providing initial evidence for the construct validity of the Indonesian ACSID-11. Future studies should investigate convergent and divergent validity by using the ACSID-11 in conjunction with other validated measures of internet addiction and other mental health dimensions. A multi-trait-multi-method approach may offer a strong framework for such studies [20]. Comparative psychometric tools should be considered in future research. Moreover, the Indonesian ACSID-11 needs to be evaluated if it can be associated with other measures on psychosocial health, given that the literature shows that behavioral addictions are associated with psychological distress [34,35,36], physical activity engagement [37], self-images [38,39], insomnia [40], learning outcomes [41,42], habituation [43], and executive functions [44,45].

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted among university students using a convenience sampling method, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, only a small number of participants reported engagement in online gambling activities. Given that online gambling is illegal in Indonesia and subject to religious restrictions, this likely contributed to the low response rate for this behavior. As a result, the assessment of reliability and validity for the online gambling component may be limited. Future research should aim to address these limitations by employing more representative sampling methods and exploring alternative strategies for assessing less commonly reported behaviors. Third, the sex ratio in the present study was imbalanced (68% female vs. 32% male). Therefore, future research should examine measurement invariance across sexes, as this is important for establishing the validity of the instrument across sex groups. Fourth, although 600 university students completed the ACSID-11, very few of the respondents reported online gambling. Therefore, the online gambling validation group was relatively small. Thus, the statistical power and reliability of the psychometric evaluation for this subgroup was limited, and future studies should examine the psychometric properties of the Indonesian ACSID-11 using larger samples of people who gamble online. Lastly and importantly, the present study did not collect data using other behavioral addiction measures (e.g., YouTube Addiction Scale [46] and South Oaks Gambling Screen [47]) or measures less relevant to behavioral addictions; therefore, the evaluation of concurrent and discriminant validity could not be conducted. Future studies should examine the concurrent and discriminant validity of the Indonesian ACSID-11.

The Indonesian ACSID-11 may be used to measure PUI concerns among university students in Indonesia. Future studies may use the ACSID-11 to explore intervention and preventive measures for specific forms of PUI. Other populations and samples should be examined to determine the generalizability of the findings beyond Indonesian university students. The Indonesian version of the ACSID-11 demonstrates promising validity and reliability for assessing specific forms of PUI among Indonesians. Researchers and healthcare practitioners are encouraged to employ the ACSID-11 to identify specific forms of PUI and to inform targeted interventions and preventive strategies within the Indonesian population.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study received support from Universitas Airlangga, in part by Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), and by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 112-2410-H-006-089-SS2).

Author Contributions: Siti Rahayu Nadhiroh: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Data Curation, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original version, Writing—Review & Editing, Approval of the final version. Ira Nurmala: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—Original version, Approval of the final version. Iqbal Pramukti: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original version, Approval of the final version. Kamolthip Ruckwongpatr: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing—Original version, Writing—Review & Editing, Approval of the final version. Laila Wahyuning Tyas: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original version, Approval of the final version. Afina Puspita Zari: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original version, Approval of the final version. Warda Eka Islamiah: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original version, Approval of the final version. Yan-Li Siaw: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Approval of the final version. Marc N. Potenza: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Approval of the final version. Chung-Ying Lin: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Approval of the final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The research data are available from the corresponding author upon justified request.

Ethics Approval: This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (Approval No. 2756-KEPK).

Informed Consent: Participants were informed prior to completing the questionnaire that their participation was voluntary and anonymous. They were also advised that they could withdraw at any time. All students consented to take part in the survey voluntarily.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose with respect to this study, as declared by the authors. MNP discloses that he has consulted for and advised Neurofinity and Boehringer Ingelheim; been involved in a patent application with Yale University and Novartis; received research support from the Mohegan Sun Casino and the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling; consulted for or advised legal, non-profit, healthcare and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control, internet use and addictive behaviors; performed grant reviews; edited journals/journal sections; given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events, and other clinical/scientific venues; and generated books or chapters for publishers of mental health texts.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072115/s1.

References

1. Dieris-Hirche J , Bottel L , Herpertz S , Timmesfeld N , te Wildt BT , Wölfling K , et al. Internet-based self-assessment for symptoms of Internet use disorder—impact of gender, social aspects, and symptom severity: German cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2023; 25: e40121. doi:10.2196/40121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dienlin T , Johannes N . The impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2020; 22( 2): 135– 42. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/tdienlin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Joseph J , Varghese A , Vr V , Dhandapani M , Grover S , Sharma S , et al. Prevalence of Internet addiction among college students in the Indian setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Psychiatr. 2021; 34( 4): e100496. doi:10.1136/gpsych-2021-100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kumar M , Mondal A . A study on Internet addiction and its relation to psychopathology and self-esteem among college students. Ind Psychiatry J. 2018; 27( 1): 61– 6. doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_61_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Fineberg NA , Demetrovics Z , Stein DJ , Ioannidis K , Potenza MN , Grünblatt E , et al. Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the internet. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018; 28( 11): 1232– 46. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wolgast M , Adler H , Nurali Wolgast S . Motives for social media use in adults: associations with platform-specific use, psychological distress, and problematic engagement. J Soc Media Res. 2025; 2( 3): 179– 94. doi:10.29329/jsomer.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang J , Zhang E , Cui S , Zhang L , Ren B , Jin Q , et al. Association of internet addiction severity with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation among civil aircrew members: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2025; 8( 3): 116– 24. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_302_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chew PK , Naidu KN , Shi J , Zhang MW . Validation of the internet gaming disorder scale–short-form and the gaming disorder test in Singapore. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2025; 8( 3): 125– 32. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_327_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kakul F , Javed S . Internet gaming disorder: an interplay of cognitive psychopathology. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2023; 6( 1): 36– 45. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_209_22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Stirnberg J , Margraf J , Precht LM , Brailovskaia J . Problematic smartphone use, depression symptoms, and fear of missing out: can reasons for smartphone use mediate the relationship? A longitudinal approach. J Soc Media Res. 2024; 1( 1): 3– 13. doi:10.29329/jsomer.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Brand M , Antons S , Bőthe B , Demetrovics Z , Fineberg NA , Jimenez Murcia S , et al. Current advances in behavioral addictions: from fundamental research to clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2025; 182( 2): 155– 63. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20240092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zare-Bidoky M , Baldacchino AM , Demetrovics Z , Fineberg N , Kamali M , Khazaal Y , et al. Problematic usage of the Internet: converging and diverging terminologies and constructs. J Behav Addict. 2025. doi:10.1101/2025.09.08.25335292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ariyadasa G , Jayawardane D , Jothipala D , Hettiwaththage CR . Prevalence of problematic Internet use and its risk factors among the adolescents in Colombo district, Sri Lanka. Am J Innov Sci Eng. 2023; 2( 1): 30– 7. doi:10.54536/ajise.v2i1.1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Islam MA , Hossin MZ . Prevalence and risk factors of problematic Internet use and the associated psychological distress among graduate students of Bangladesh. Asian J Gambl Issues Public Health. 2016; 6( 1): 11. doi:10.1186/s40405-016-0020-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dewi N , Primanita RY . Hubungan antara kecenderungan Internet addiction dan prokrastinasi akademik pada mahasiswa universitas negeri padang. Nusant J Ilmu Pengetah Sos. 2023; 10( 3): 1031– 41. [Google Scholar]

16. Yang YN , Su JA , Pimsen A , Chen JS , Potenza MN , Pakpour AH , et al. Validation of the Thai Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-Use Disorders (ACSID-11) among young adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23( 1): 819. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-05210-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Müller SM , Wegmann E , Oelker A , Stark R , Müller A , Montag C , et al. Assessment of criteria for specific internet-use disorders (ACSID-11): introduction of a new screening instrument capturing ICD-11 criteria for gaming disorder and other potential Internet-use disorders. J Behav Addict. 2022; 11( 2): 427– 50. doi:10.1556/2006.2022.00013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qin L , Cheng L , Hu M , Liu Q , Tong J , Hao W , et al. Clarification of the cut-off score for nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS9-SF) in a Chinese context. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11: 470. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kim H , Ku B , Kim JY , Park YJ , Park YB . Confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis for validating the phlegm pattern questionnaire for healthy subjects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016; 2016: 2696019. doi:10.1155/2016/2696019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Oelker A , Rumpf HJ , Brand M , Müller SM . Validation of the ACSID-11 for consistent screening of specific Internet-use disorders based on ICD-11 criteria for gaming disorder: a multitrait-multimethod approach. Compr Psychiatry. 2024; 132: 152470. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2024.152470 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Saffari M , Chen CY , Chen IH , Ruckwongpatr K , Griffiths MD , Potenza MN , et al. A comprehensive measure assessing different types of problematic use of the internet among Chinese adolescents: the Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-use Disorders (ACSID-11). Compr Psychiatry. 2024; 134: 152517. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2024.152517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liberacka-Dwojak M , Cruz GV , Wiłkość-Dębczyńska M , Rochat L , Khan R , Mueller SM , et al. Validation of the English Assessment of Criteria for Specific Internet-Use Disorders (ACSID-11) for tinder and online pornography use. Front Psychiatry. 2025; 16: 1595502. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1595502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pramukti I , Nurmala I , Nadhiroh SR , Tung SEH , Gan WY , Siaw YL , et al. Problematic use of Internet among Indonesia university students: psychometric evaluation of Bergen social media addiction scale and internet gaming disorder scale-short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2023; 20( 12): 1103– 11. doi:10.30773/pi.2022.0304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nurmala I , Nadhiroh SR , Pramukti I , Tyas LW , Zari AP , Griffiths MD , et al. Reliability and validity study of the Indonesian Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS) among college students. Heliyon. 2022; 8( 8): e10403. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cheung H , Mazerolle L , Possingham HP , Tam KP , Biggs D . A methodological guide for translating study instruments in cross-cultural research: adapting the ‘connectedness to nature’ scale into Chinese. Methods Ecol Evol. 2020; 11( 11): 1379– 87. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.13465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kalkbrenner MT . Alpha, omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: reviewing these options and when to use them. Couns Outcome Res Eval. 2023; 14( 1): 77– 88. doi:10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Acharya D , Thomas M , Cann R . Validation of a questionnaire to measure sexual health knowledge and understanding (Sexual Health Questionnaire) in Nepalese secondary school: a psychometric process. J Educ Health Promot. 2016; 5( 1): 18. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.184560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ravinder EB , Saraswathi AB . Literature review of Cronbach alpha coefficient (A) and McDonald’s omega coefficient (Ω). Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2020; 7( 6): 2943– 9. [Google Scholar]

29. de Souza AC , Alexandre NMC , de Brito Guirardello E , de Souza AC , Alexandre NMC , de Brito Guirardello E . Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiol E Serviços De Saúde. 2017; 26( 3): 649– 59. doi:10.5123/S1679-49742017000300022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bujang MA , Omar ED , Baharum NA . A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: a simple guide for researchers. Malays J Med Sci. 2018; 25( 6): 85– 99. doi:10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Schneider S , Stone AA . Distinguishing between frequency and intensity of health-related symptoms from diary assessments. J Psychosom Res. 2014; 77( 3): 205– 12. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Noel JK , Sammartino CJ , Johnson M , Swanberg J , Rosenthal SR . Smartphone addiction and mental illness in Rhode Island young adults. Rhode Isl Med J. 2023; 106( 3): 35– 41. [Google Scholar]

33. Lozano-Blasco R , Robres AQ , Sánchez AS . Internet addiction in young adults: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Comput Hum Behav. 2022; 130: 107201. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mitropoulou E . Exploration of the association between social media addiction, self-esteem, self-compassion and loneliness. J Soc Media Res. 2024; 1( 1): 25– 37. doi:10.29329/jsomer.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Brydevall M , Albertella L , Christensen E , Suo C , Yücel M , Lee RSC . The role of psychological distress in understanding the relationship between habitual decision-making and addictive behaviors. J Psychiatr Res. 2025; 184: 297– 306. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2025.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hou ACY , Pham Thi TD , Hou X . Understanding problematic TikTok use: cognitive absorption, nomophobia, and life stress. Acta Psychol. 2025; 260: 105536. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang P-C , Geusens F , Tu H-F , Fung XCC , Chen C-Y . Association between problematic social media use and physical activity: the mediating roles of nomophobia and the tendency to avoid physical activity. J Soc Media Res. 2024; 1( 1): 14– 24. doi:10.29329/jsomer.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bottaro R , Valenti GD , Faraci P . Internet addiction and psychological distress: can social networking site addiction affect body uneasiness across gender? A mediation model. Eur J Psychol. 2024; 20( 1): 41– 62. doi:10.5964/ejop.10273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Knight R , Preston C . What is the impact of viewing social media style images in different contexts on body satisfaction and body size estimation? J Soc Media Res. 2025; 2( 3): 164– 78. doi:10.29329/jsomer.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lin YC , Huang PC . Digital traps: How technology fuels nomophobia and insomnia in Taiwanese college students. Acta Psychol. 2025; 252: 104674. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Phetphum C , Keeratisiroj O , Prajongjeep A . The association between mobile game addiction and mental health problems and learning outcomes among Thai youths classified by gender and education levels. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2023; 6( 4): 196– 202. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_353_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Afrin S , Rahman NA , Tabassum TT . The Impact of internet addiction on academic performance among medical students in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study and the potential role of yoga. Ann Neurosci. 2023: 09727531241235999. doi:10.1101/2023.06.28.23292017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tan CN-L . Toward an integrated framework for examining the addictive use of smartphones among young adults. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2023; 6( 3): 119– 25. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_206_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kräplin A , Joshanloo M , Wolff M . The relationship between executive functioning and addictive behavior: new insights from a longitudinal community study. Psychopharmacology. 2022; 239( 11): 3507– 24. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06224-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chen CY , Chang HY , Lane HY , Liao YC , Ko HC . The executive function, behavioral systems, and heart rate variability in college students at risk of Mobile gaming addiction. Acta Psychol. 2025; 254: 104809. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Huang PC , Chen CY , Chen IH , Chen JK , Pramukti I , Yu RL , et al. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of video addiction scales: the Chinese YouTube addiction scale for Taiwan and Hong Kong. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2025; 28( 10): 672– 9. doi:10.1177/21522715251378312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhou Y , Cui Y , Shi S , Liu J , Wei Y , Zhang X , et al. Chinese South Oaks gambling screen: a study on reliability and validity in mainland China. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2025; 8( 1): 9– 14. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_250_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools