Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Associations between Work Schedule Type and Physical Activity with Mental Health and Job Stress among Seoul Metro Employees

1 Department of Health and Fitness, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, 01811, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Sport Science, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, 01811, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jonghwa Lee. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Improving Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) Through Promoting Health-Related Behaviors)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1949-1960. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072560

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Shift-based occupations have been consistently linked to adverse psychological outcomes; however, limited research has examined how work schedule type and physical activity are jointly associated with mental health and job stress in public transportation employees, a population frequently exposed to irregular hours and safety-critical responsibilities. This study investigated the associations between work schedule type and physical activity with mental health indicators and job stress among Seoul Metro employees. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was administered to 298 full-time male employees of Seoul Metro. Participants were categorized by work schedule (shift vs. regular) and physical activity level (regular, irregular, none) following American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines. Mental health (sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, loneliness) was assessed using validated binary indicators, and job stress was measured with the Korean Occupational Stress Scale–Short Form (KOSS-SF). Group differences were analyzed using chi-square tests, t-tests, and one-way ANOVA with effect sizes, and binary logistic and multiple regression analyses were conducted to identify predictors. Results: Shift workers reported significantly higher sleep disturbance and anxiety compared to regular daytime workers (p < 0.05). Employees who participated in regular physical activity had lower odds of sleep disturbance and depression (p < 0.05) and showed lower job stress scores compared with inactive workers. Work schedule type and physical activity were independently associated with mental health and job stress among transit employees. Conclusion: These findings underscore the dual influence of work schedule and physical activity on the psychological and occupational well-being of public transit employees. Promoting regular physical activity may buffer occupational stress among employees engaged in shift-based work. Workplace interventions that support physical activity participation and improve shift planning may enhance employee well-being.Keywords

Rapid urbanization and the increasing demand for uninterrupted public services have led to a global rise in nonstandard work arrangements, particularly shift work. In transportation, healthcare, and security sectors, employees are frequently required to work irregular schedules that extend beyond traditional daytime hours. In South Korea, shift work has become a structural necessity in essential public operations such as the Seoul Metro system, which operates nearly 24 h a day to meet the mobility needs of more than seven million daily commuters. Maintaining continuous service requires a large portion of metro employees to work rotating schedules, night shifts, or extended duty hours.

Shift work disrupts biological functioning by interfering with circadian rhythms and sleep–wake cycles, which regulate neuroendocrine responses and psychological stability [1,2,3]. A growing body of research has linked shift work to sleep disorders, chronic fatigue, cardiovascular disease, and impaired cognitive performance [4,5,6,7]. In addition to physiological strain, shift work is consistently associated with adverse psychological consequences, including depression, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion [8,9]. The World Health Organization has identified disrupted sleep and occupational stress as major risk factors contributing to the global mental health burden among working adults [10].

However, the extent to which shift work influences psychological outcomes may differ depending on occupational context, work structure, and coping resources available to employees. The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model provides a useful framework for understanding this variability [11]. According to the JD-R model, work environments characterized by high job demands (e.g., workload, time pressure, irregular scheduling) and low job resources (e.g., autonomy, supervisor support) are more likely to result in psychological strain and job stress [12]. Shift workers often experience elevated psychological demands due to irregular working hours, safety-critical responsibilities, and high public service expectations, which may increase exposure to stress-related mental health problems [13]. In parallel, Effort–Recovery Theory (E-RT) suggests that repeated exposure to demanding work schedules without adequate recovery impairs psychological resilience and increases stress vulnerability over time [14].

Despite well-established links between shift work and mental strain, the role of modifiable behavioral factors that may reduce psychological risk in shift workers remains underexplored. One promising factor is physical activity, which has consistently been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, enhance emotional regulation, and buffer stress responses [15,16,17,18]. The stress-buffering hypothesis posits that physical activity enhances physiological recovery and emotional coping capacity, thereby protecting individuals from the detrimental effects of occupational stress [19]. Evidence indicates that physically active workers report lower job stress and better psychological well-being than their sedentary peers [20,21]. However, relatively few studies have examined whether physical activity can mitigate the psychological burden of shift work in high-demand public service occupations such as metro transportation [22].

Although previous studies have examined the negative consequences of shift work on workers’ health, most research has focused on either sleep problems or general occupational stress in isolation, without considering broader psychological outcomes such as depression, anxiety, or loneliness [23,24]. Existing studies have also emphasized medical and physiological outcomes but have paid limited attention to emotional health indicators that are highly relevant to quality of life and long-term well-being. Furthermore, the interactive or combined associations between work schedule type and physical activity have rarely been investigated in the same model, particularly in safety-sensitive occupations such as metro operations.

Another key limitation in the literature is the lack of empirical research conducted in Asian work environments, especially within collectivist cultures such as South Korea. Cultural characteristics may shape occupational stress responses and coping behaviors [25]. For example, Korean employees often experience strong professional role identity and collectivist team dynamics, which can influence emotional expression and perceived social support at work. Therefore, findings from Western occupational studies may not generalize to Korean public transportation workers [26].

In addition, studies that include both work-related and health-related lifestyle factors are still scarce [27]. While shift work is typically considered a non-modifiable occupational exposure, physical activity represents a modifiable behavioral factor that may serve as a protective resource within the JD-R framework [28]. Engaging in regular physical activity may enhance psychological resilience, reduce job strain, and promote better mental health among employees exposed to high job demands. However, limited research has examined whether physical activity can buffer the adverse associations between shift work and mental health in public transportation settings [29,30].

Correctively, there is a clear need for research that simultaneously examines work schedule type and physical activity as correlates of workers’ mental health and job stress. In addition, research is particularly warranted in occupations where shift work is unavoidable and job safety demands are high, such as in metro systems.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the associations between work schedule type, physical activity, and mental health indicators among Seoul Metro employees. Grounded in the JD-R model and the stress-buffering hypothesis, this study also explored whether physical activity may serve as a protective resource against job stress among employees exposed to demanding work schedules.

Accordingly, this study addressed the following research objectives: (1) To compare mental health outcomes (sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, loneliness) and job stress across work schedule types (shift vs. regular work), (2) To compare mental health outcomes and job stress across physical activity levels, (3) To examine whether work schedule type and physical activity predict mental health and job stress among metro employees.

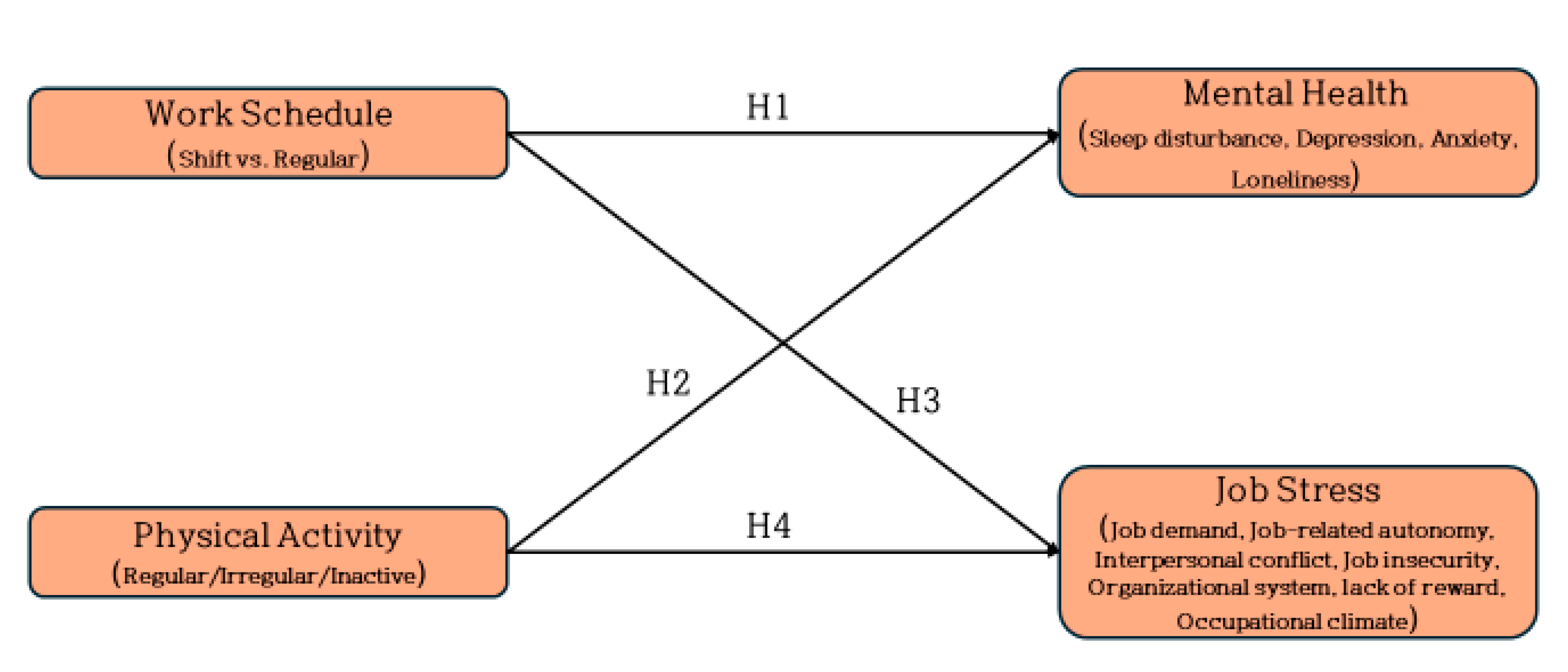

Based on the literature and theoretical framework, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Shift workers will report higher levels of mental health problems (sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, loneliness) than regular workers.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Employees who participate in regular physical activity will report lower levels of mental health problems than physically inactive employees.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Shift workers will experience higher levels of job stress than regular workers.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Regular physical activity will be negatively associated with job stress among metro employees.

Fig. 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study, illustrating the hypothesized associations among work schedule type, physical activity, mental health, and job stress.

Figure 1: Hypothesized conceptual framework of the study.

2.1 Study Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to examine the associations between work schedule type and physical activity with mental health and job stress among employees of Seoul Metro. Participants were recruited from train operation, maintenance, and station management departments. A total of 298 full-time employees (mean age = 42.1, standard deviation [SD] = 8.4) participated in the study. All participants in this study were male, which reflects the demographic structure of the Seoul Metro workforce, where over 90% of frontline operational staff are male due to historical recruitment patterns and job characteristics. Although this enhances occupational relevance, it limits the generalizability of findings to female employees, which is acknowledged as a study limitation. A convenience sampling strategy was used due to restricted access to metro personnel and the operational requirements of the transportation system that prevented random sampling. This approach is commonly used in occupational field research when access to specific professional populations is required [31]. To minimize potential selection bias, recruitment was conducted across multiple departments and work sites. Additionally, the survey was conducted anonymously, and no identifiable personal information was collected. Participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential and would not impact their employment status. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. All procedures adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were fully informed of the study’s objectives and provided written informed consent. The study protocol (IRB No. 2025-0057-02) received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Seoul National University of Science and Technology.

Table 1: The general characteristics of the study participants.

| Variables | Category | Participants (n = 298) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | ≤35 | 10 | 3.4 |

| 36–40 | 68 | 22.8 | |

| 41–45 | 131 | 44.0 | |

| 46–50 | 54 | 18.1 | |

| 51–55 | 35 | 11.7 | |

| Career (yrs) | ≤5 | 11 | 3.7 |

| 6–10 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 11–15 | 122 | 40.9 | |

| 16–20 | 116 | 38.9 | |

| 21–25 | 34 | 11.4 | |

| >25 | 14 | 4.7 | |

| Physical activity | Regular exerciser | 64 | 21.8 |

| Irregular exerciser | 193 | 64.8 | |

| Non-exerciser | 39 | 13.4 | |

| Working schedule type | Shift work | 150 | 50.3 |

| Regular work | 148 | 49.7 |

To classify the participants’ work schedule types, participants were asked to indicate whether they engaged in shift-based work (e.g., rotating, night, or 24-h shifts) or regular daytime work. Based on responses, participants were categorized into either a “shift work” group or a “regular daytime work” group.

Physical activity was classified based on expert panel guidance and criteria from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) [32]. Participants were categorized into three groups: non-exercisers (no physical activity), irregular exercisers (occasional activity not meeting ACSM recommendations), and regular exercisers (engaging in moderate-intensity activity for ≥150 min or vigorous-intensity activity for ≥75 min per week).

2.2.3 Mental Health Indicators

Four mental health indicators were evaluated: sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Each indicator was measured using a validated single-item binary scale (yes/no) commonly applied in public workforce surveillance. The survey items were: “do you experience difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep due to work-related fatigue or irregular schedule?” (sleep disturbance), “during the last two weeks, have you felt persistent sadness or loss of interest in daily activities?” (depression), “do you feel nervous, tense, or worried due to work responsibilities?” (anxiety), and “do you often feel isolated despite being around others at work or home?” (loneliness). Binary mental health items have been used in large-scale occupational surveys for feasibility in time-constrained work environments and have shown acceptable screening validity (Cronbach’s α = 0.762) [33]. Although multi-item psychometric tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) are commonly used, brief binary indicators are appropriate for occupational field research requiring rapid assessment among on-duty employees.

Job stress was measured using the short-form Korean Occupational Stress Scale (KOSS-SF) [34], which includes 23 items across seven subscales: job demand, job-related autonomy, interpersonal conflict, job insecurity, organizational system, lack of reward, and occupational climate. Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Prior psychometric validation supports the scale’s reliability and multidimensional structure (KMO = 0.747; Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Exploratory factor analysis for the job stress scale.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational system 2 | 0.777 | −0.264 | 0.154 | 0.056 | −0.122 | −0.102 | −0.065 | |

| Organizational system 1 | 0.731 | −0.301 | 0.147 | 0.013 | −0.105 | −0.156 | −0.053 | |

| Organizational system 3 | 0.618 | −0.183 | 0.013 | 0.056 | −0.237 | −0.152 | −0.195 | |

| Organizational system 4 | 0.564 | 0.007 | 0.134 | 0.115 | −0.210 | −0.135 | −0.229 | |

| Job insecurity 1 | −0.203 | 0.795 | −0.035 | −0.031 | 0.097 | 0.205 | 0.007 | |

| Job insecurity 2 | −0.297 | 0.777 | 0.066 | −0.013 | 0.103 | 0.197 | 0.129 | |

| Job-related autonomy 1 | 0.071 | 0.062 | 0.764 | 0.072 | −0.195 | 0.069 | −0.038 | |

| Job-related autonomy 3 | 0.264 | −0.025 | 0.540 | 0.328 | −0.117 | −0.046 | −0.148 | |

| Job-related autonomy 2 | −0.039 | −0.003 | 0.483 | 0.127 | −0.224 | 0.236 | −0.015 | |

| Job-related autonomy 4 | 0.209 | 0.080 | 0.360 | 0.253 | −0.105 | −0.143 | −0.030 | Excluded |

| Interpersonal conflict 1 | 0.080 | −0.087 | 0.147 | 0.768 | −0.117 | −0.048 | −0.122 | |

| Interpersonal conflict 2 | −0.082 | 0.088 | 0.099 | 0.558 | −0.198 | 0.037 | −0.197 | |

| Interpersonal conflict 3 | 0.118 | 0.048 | 0.216 | 0.509 | −0.155 | −0.079 | −0.134 | |

| Lack of reward 2 | 0.172 | −0.076 | 0.186 | 0.175 | −0.809 | −0.061 | −0.243 | |

| Lack of reward 3 | 0.396 | −0.140 | 0.362 | 0.223 | −0.565 | −0.116 | −0.339 | |

| Lack of reward 1 | 0.320 | −0.108 | 0.165 | 0.345 | −0.459 | −0.148 | −0.210 | |

| Job demand 2 | −0.198 | 0.238 | 0.021 | −0.081 | 0.069 | 0.665 | 0.222 | |

| Job demand 1 | −0.163 | 0.201 | 0.138 | −0.062 | −0.068 | 0.614 | 0.228 | |

| Job demand 4 | −0.060 | 0.010 | 0.042 | −0.127 | 0.101 | 0.596 | 0.178 | |

| Job demand 3 | −0.100 | 0.095 | 0.036 | 0.066 | 0.009 | 0.531 | 0.034 | |

| Occupational climate 4 | −0.099 | 0.079 | −0.080 | −0.096 | 0.197 | 0.136 | 0.748 | |

| Occupational climate 3 | −0.140 | 0.064 | −0.040 | −0.274 | 0.186 | 0.204 | 0.746 | |

| Occupational climate 2 | −0.237 | 0.092 | −0.032 | −0.184 | 0.290 | 0.160 | 0.663 | |

| Occupational climate 1 | −0.084 | −0.094 | −0.027 | −0.100 | 0.139 | 0.125 | 0.465 | |

| Eigenvalue | 4.202 | 2.473 | 2.200 | 1.633 | 1.432 | 1.346 | 1.150 | |

| % of Variance | 17.507 | 10.304 | 9.167 | 6.804 | 5.968 | 5.609 | 4.793 | |

| Cumulative % | 17.507 | 27.812 | 36.979 | 43.783 | 49.751 | 55.360 | 60.153 | |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.764 | 0.767 | 0.596 | 0.622 | 0.666 | 0.691 | 0.744 |

Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to summarize participant characteristics. Group differences in mental health and job stress by work schedule type and physical activity level were examined using crosstab analysis with chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Effect sizes were calculated to complement significance testing, with Cohen’s d reported for t-tests and eta squared (η2) for ANOVA results, following conventional interpretation guidelines [35]. Prior to regression analyses, statistical assumptions were tested. Normality was assessed using skewness and kurtosis values (acceptable range ±2.0). Multicollinearity was examined using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), with all values below 2.0 indicating no concern. Independence of residuals was evaluated using the Durbin–Watson statistic. Finally, binary logistic regression was conducted to identify predictors of mental health outcomes, while multiple linear regression was used to analyze the impact of work schedule and physical activity on the various dimensions of job stress. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with the significance level set at p < 0.05.

3.1 Differences in Mental Health by Work Schedule and Physical Activity

As shown in Table 3, a crosstab analysis revealed significant differences in mental health based on work schedule type. Shift workers reported higher rates of sleep disturbances (χ2 = 9.22, p < 0.01) and anxiety (χ2 = 6.68, p < 0.05) compared to regular workers. As detailed in Table 4, all four mental health indicators showed statistically significant differences based on physical activity.

Table 3: Mental health by the working schedule types.

| Variables | Answer | Working Schedule Types | Total | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift | Regular | ||||

| Sleep disturbances | Yes | 81 (27.2) | 54 (18.1) | 135 (45.3) | 9.22** |

| No | 69 (23.2) | 94 (31.5) | 163 (54.7) | ||

| Depression | Yes | 61 (20.5) | 50 (16.8) | 111 (37.2) | 1.51 |

| No | 89 (29.9) | 98 (32.9) | 187 (62.8) | ||

| Anxiety | Yes | 102 (34.2) | 79 (26.5) | 181 (60.7) | 6.68* |

| No | 48 (16.1) | 69 (23.2) | 117 (39.3) | ||

| Loneliness | Yes | 55 (18.5) | 46 (15.4) | 101 (33.9) | 1.04 |

| No | 95 (31.9) | 102 (34.2) | 197 (66.1) | ||

Table 4: Mental health by physical activity.

| Variables | Answer | Physical Activity | Total | χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Irregular | No | ||||

| Sleep disturbances | Yes | 12 (4.0) | 83 (27.9) | 40 (13.4) | 135 (45.3) | 11.11** |

| No | 28 (9.4) | 110 (36.9) | 25 (8.4) | 163 (54.7) | ||

| Depression | Yes | 8 (2.7) | 71 (23.8) | 32 (10.7) | 111 (37.2) | 9.10* |

| No | 32 (10.7) | 122 (40.9) | 33 (11.1) | 187 (62.8) | ||

| Anxiety | Yes | 21 (7.0) | 112 (37.6) | 48 (16.1) | 181 (60.7) | 6.42* |

| No | 19 (6.4) | 81 (27.2) | 17 (5.7) | 117 (39.3) | ||

| Loneliness | Yes | 6 (2.0) | 66 (22.1) | 29 (9.7) | 101 (33.9) | 9.72** |

| No | 34 (11.4) | 127 (42.6) | 36 (12.1) | 197 (66.1) | ||

3.2 Differences in Job Stress by Work Schedule and Physical Activity

Table 5 indicates that shift workers reported significantly higher levels of job demand (t = 3.62, p < 0.001) and job insecurity (t = 6.99, p < 0.001). Furthermore, as shown in Table 6, ANOVA results revealed significant differences across physical activity levels for job demand (F = 16.64, p < 0.001) and occupational climate (F = 9.51, p < 0.001).

Table 5: Job stress by working schedule types.

| Variables | Working Schedule Types | t (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shift | Non-Shift | ||

| Job demand | 2.56 ± 0.39 | 2.39 ± 0.38 | 3.62*** |

| Job-related autonomy | 2.53 ± 0.42 | 2.48 ± 0.40 | 0.95 |

| Interpersonal conflict | 2.84 ± 0.32 | 2.88 ± 0.37 | −0.78 |

| Job insecurity | 3.04 ± 0.42 | 2.67 ± 0.50 | 6.99*** |

| Organizational system | 2.14 ± 0.45 | 2.34 ± 0.35 | −4.32*** |

| Lack of reward | 2.24 ± 0.49 | 2.39 ± 0.46 | −2.68** |

| Occupational climate | 2.34 ± 0.38 | 2.33 ± 0.40 | 0.20 |

Table 6: Job stress by physical activity.

| Variables | Physical Activity | F | Scheffé | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular (A) | Irregular (B) | No (C) | |||

| Job demand | 2.18 ± 0.33 | 2.49 ± 0.38 | 2.61 ± 0.39 | 16.64*** | A < B, A < C |

| Job-related autonomy | 2.42 ± 0.42 | 2.53 ± 0.42 | 2.50 ± 0.36 | 1.22 | |

| Interpersonal conflict | 2.83 ± 0.31 | 2.87 ± 0.36 | 2.84 ± 0.35 | 0.33 | |

| Job insecurity | 2.78 ± 0.63 | 2.86 ± 0.48 | 2.91 ± 0.45 | 0.88 | |

| Organizational system | 2.30 ± 0.27 | 2.20 ± 0.44 | 2.31 ± 0.41 | 2.00 | |

| Lack of reward | 2.35 ± 0.40 | 2.31 ± 0.49 | 2.31 ± 0.50 | 0.14 | |

| Occupational climate | 2.09 ± 0.28 | 2.38 ± 0.39 | 2.34 ± 0.39 | 9.51*** | A < B, A < C |

3.3 Relationships of Work Schedule and Physical Activity with Mental Health and Job Stress

A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of mental health indicators (Table 7). Shift work was a significant predictor of sleep disturbance (odds ratio [OR] = 2.04, 95% CI [1.27, 3.28], p < 0.01) and anxiety (OR = 1.86, 95% CI [1.15, 3.00], p < 0.05). Regular physical activity was associated with lower odds of sleep disturbance (OR = 0.28, 95% CI [0.12, 0.65], p < 0.01) and depression (OR = 0.26, 95% CI [0.11, 0.66], p < 0.01). However, no significant predictors were found for loneliness.

Table 7: Relationships of the working schedule types and physical activity with mental health.

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | B | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||||||

| Sleep disturbances | Working schedule types | Shift | 0.71 | 0.24 | 8.68 | 0.003** | 2.04 | 1.27 | 3.28 |

| Physical activity | Regular | −1.28 | 0.44 | 8.64 | 0.003** | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.65 | |

| Irregular | −0.79 | 0.30 | 6.94 | 0.008** | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.82 | ||

| Depression | Working schedule types | Shift | 0.26 | 0.25 | 1.15 | 0.284 | 1.30 | 0.81 | 2.10 |

| Physical activity | Regular | −1.33 | 0.47 | 8.11 | 0.004** | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.66 | |

| Irregular | −0.52 | 0.29 | 3.17 | 0.075 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 1.05 | ||

| Anxiety | Working schedule types | Shift | 0.62 | 0.24 | 6.47 | 0.011* | 1.86 | 1.15 | 3.00 |

| Physical activity | Regular | −0.89 | 0.43 | 4.32 | 0.038* | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.95 | |

| Irregular | −0.75 | 0.32 | 5.29 | 0.024* | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.90 | ||

| Loneliness | Working schedule types | Shift | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.75 | 2.01 |

| Physical activity | Regular | −1.50 | 0.51 | 8.67 | 0.003** | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.61 | |

| Irregular | −0.44 | 0.29 | 2.29 | 0.130 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.14 | ||

A multiple regression analysis was performed to investigate predictors of job stress (Table 8). Work schedule (β = −0.19, p < 0.01) and physical activity (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) together explained 12% of the variance in job demand (Adjusted R2 = 0.12). Work schedule alone was a strong predictor, accounting for 14% of the variance in job insecurity (Adjusted R2 = 0.14, β = −0.37, p < 0.001) and 5% of the variance in perceptions of the organizational system (Adjusted R2 = 0.05, β = 0.25, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, physical activity independently accounted for 3% of the variance in occupational climate (Adjusted R2 = 0.03, β = 0.19, p < 0.01).

Table 8: Relationships of the working schedule types and physical activity with job stress.

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | T | F | adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job demand | Working schedule types | −0.19 | −3.51** | 21.00*** | 0.12 |

| Physical activity | 0.29 | 5.27*** | |||

| Job-related autonomy | Working schedule types | −0.05 | −0.91 | 0.74 | −0.01 |

| Physical activity | 0.04 | 0.76 | |||

| Interpersonal conflict | Working schedule types | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.31 | −0.01 |

| Physical activity | −0.01 | −0.01 | |||

| Job insecurity | Working schedule types | −0.37 | −6.93*** | 25.00*** | 0.14 |

| Physical activity | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| Organizational system | Working schedule types | 0.25 | 4.34*** | 9.54*** | 0.05 |

| Physical activity | 0.04 | 0.71 | |||

| Lack of reward | Working schedule types | 0.15 | 2.66** | 3.61* | 0.02 |

| Physical activity | −0.01 | −0.25 | |||

| Occupational climate | Working schedule types | −0.01 | −0.03 | 5.38** | 0.03 |

| Physical activity | 0.19 | 3.26** |

The purpose of this study was to examine the associations between work schedule type and physical activity with mental health and job stress among employees working in the Seoul Metro system. Consistent with previous findings, the current findings indicated that shift workers reported significantly higher levels of sleep disturbance and anxiety compared to regular daytime workers, supporting the notion that irregular work schedules disrupt circadian alignment and increase psychological strain [36,37]. Recent studies have further confirmed that prolonged exposure to shift work correlates with a higher incidence of mood disorders, especially in middle-aged and older workers [38]. Poor sleep quality has been identified as a key mediator in the relationship between shift work and adverse psychological outcomes, underscoring the importance of sleep hygiene interventions [39]. Moreover, cross-national research indicates that supportive supervision and predictable scheduling can significantly buffer stress-related outcomes among public service workers [40]. In contrast, no significant differences were found in depression or loneliness between work schedule types, suggesting that certain emotional outcomes may be influenced by occupational or social factors beyond work timing alone [6,14,16]. This discrepancy may be attributable to contextual factors specific to the Seoul Metro workforce, such as strong organizational cohesion, team-based work structures, or a sense of psychological resilience stemming from job stability. Future qualitative investigations could help elucidate the protective mechanisms that may buffer against mood disorders in this specific setting.

Moreover, the current findings found that physical activity emerged as a robust protective factor. The participants engaging in regular physical activity exhibited significantly lower odds of all four mental health indicators (i.e., sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, and loneliness) and reported more favorable perceptions of job stress. Notably, the protective effects of regular physical activity were consistently stronger than those of irregular activity, suggesting a threshold of engagement required to generate meaningful mental health benefits. These results reinforce the accumulating evidence supporting exercise as a transdiagnostic intervention for emotional and occupational resilience [41]. Previous studies indicated that physical activity was positively associated with reduced perceived job demand and a more favorable occupational climate, lending support to the stress-buffering hypothesis [22,24]. In particular, the strong association between physical activity and improved occupational climate suggests that promoting an active lifestyle could also yield secondary benefits in organizational culture [19,20,21,22,23].

This study indicated that working types and physical activity were the significant predictors in explaining job stress. Specifically, shift work negatively affects job demands and job insecurity, while regular physical activity positively influences them. It is plausible to explain that shift work was associated with elevated job demands and job insecurity, which are commonly cited precursors to burnout and emotional exhaustion [9,17,18]. Interestingly, shift workers reported more favorable perceptions of their organizational systems and reward structures, possibly reflecting institutional efforts to standardize and incentivize nonstandard scheduling. Such dual effects underscore the complex psychosocial landscape of shift-based employment and highlight the importance of holistic policy approaches.

These findings obtained from the current study highlight that both work schedule type and physical activity emerged as independent predictors of mental health and job stress, suggesting the need for integrated approaches to employee health promotion in occupational settings. Theoretically, it is plausible to be interpreted within the framework of the JD-R model. According to this model, occupations with high job demands and insufficient recovery resources lead to increased stress and adverse mental health outcomes [12]. Shift work represents a critical job demand because irregular schedules disrupt biological rhythms, increase fatigue, and reduce opportunities for recovery. This explains why shift workers in this study reported higher sleep disturbance and anxiety—both early indicators of strain in the JD-R process. Furthermore, the E-RT supports these findings by suggesting that workers require adequate time and conditions for physiological and psychological recovery [14]. However, shift workers often experience restricted recovery opportunities, resulting in cumulative fatigue and heightened vulnerability to psychological distress. This mechanism provides a theoretical explanation for the association between shift work and higher job stress observed in this study.

These findings might also be interpreted within the cultural and occupational context of South Korea. Korean work culture is characterized by long working hours, hierarchical organizational structures, and strong professional duty norms, particularly in public service sectors. In metro operations, employees are responsible for public safety and system reliability, which may increase job-related vigilance demands and contribute to elevated job stress. Despite this, levels of depression and loneliness did not differ significantly between shift and non-shift workers in this study, possibly due to strong team cohesion and collectivist workplace support found in Korean occupational environments.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents causal interpretation of findings. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine temporal relationships between work schedule, physical activity, and mental health. Second, mental health indicators were measured using binary screening items. Although this approach is consistent with occupational field survey practices, future research would benefit from using validated multi-item psychological measures such as the PHQ-9, GAD-7, or Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21). Third, the sample consisted only of male metro employees, which limits generalizability. Future studies should include female workers and employees from diverse occupational sectors. Finally, future research should consider mixed-method approaches to explore contextual and organizational factors influencing worker stress and resilience in greater depth.

This study highlights the profound influence of work schedule and physical activity on the mental health and job stress of employees in the public transit sector. Shift work was associated with higher sleep disturbance, anxiety, and job stress, whereas regular physical activity showed protective associations with mental health and reduced job stress. These findings indicate that both occupational demands and individual behavioral factors contribute to employee psychological well-being. This study extends previous research by integrating work schedule type and physical activity within the JD-R framework, demonstrating that physical activity may serve as a personal resource that buffers job stress. The results contribute to occupational health literature by emphasizing the importance of combining job design strategies with employee wellness promotion. Practically, the current study suggests that organizations employing shift workers should implement fatigue management strategies, optimize shift scheduling, and support accessible physical activity programs. Such interventions may protect mental health and reduce job stress among employees working in safety-sensitive sectors.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Youngho Kim. Data collection: Jonghwa Lee. Formal analysis and manuscript writing: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Seoul National University of Science and Technology (2025-0057-02). All procedures adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were fully informed of the study’s objectives and provided written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kecklund G , Axelsson J . Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016; 355: i5210. doi:10.1136/bmj.i5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Booker LA , Spong J , Hodge B , Deacon-Crouch M , Bish M , Mills J , et al. Differences in shift and work-related patterns between metropolitan and regional/rural healthcare shift workers and the occupational health and safety risks. Aust J Rural Health. 2024; 32( 1): 141– 51. doi:10.1111/ajr.13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chang WP , Peng YX . Meta-analysis of differences in sleep quality based on actigraphs between day and night shift workers and the moderating effect of age. J Occup Health. 2021; 63( 1): e12262. doi:10.1002/1348-9585.12262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Huang G , Lee TY , Banda KJ , Pien LC , Jen HJ , Chen R , et al. Prevalence of sleep disorders among first responders for medical emergencies: a meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2022; 12: 04092. doi:10.7189/jogh.12.04092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Merkus SL , Van Drongelen A , Holte KA , Labriola M , Lund T , Van Mechelen W , et al. The association between shift work and sick leave: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2012; 69( 10): 701– 12. doi:10.1136/oemed-2011-100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Brown JP , Martin D , Nagaria Z , Verceles AC , Jobe SL , Wickwire EM . Mental health consequences of shift work: an updated review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020; 22( 3): 1– 7. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-1131-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shin MG , Kim YJ , Kim TK , Kang D . Effects of long working hours and night work on subjective well-being depending on work creativity and task variety, and occupation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18( 12): 6371. doi:10.3390/ijerph18126371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Torquati L , Mielke GI , Brown WJ , Burton NW , Kolbe-Alexander TL . Shift work and poor mental health: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. America J Public Health. 2019; 109( 11): e13– 20. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Askari A , Feyzi V , Farhadi A , Dashti A , Poursadegiyan M , Salehi Sahi Abadi A . Examining the impact of occupational stress and shift work schedules on cognitive functions among firefighters. Work. 2025; 81( 2): 2662– 9. doi:10.1177/10519815251320268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. World Health Organization . The World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) (WHO-UCN-MSD-MHE-2024.01) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/WHO-UCN-MSD-MHE-2024.01. [Google Scholar]

11. Bakker AB , Demerouti E . Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017; 22( 3): 273– 85. doi:10.1037/ocp0000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bakker AB , Demerouti E . Job demands–resources theory: ten years later. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023; 10: 25– 53. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Barger LK , Lockley SW , Rajaratnam SM , Landrigan CP . Neurobehavioral, health, and safety consequences associated with shift work. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009; 9( 2): 155– 64. doi:10.1007/s11910-009-0024-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Albulescu P , Macsinga I , Rusu A , Sulea C , Bodnaru A , Tulbure BT . “Give me a break!” a systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of micro-breaks for increasing well-being and performance. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 8): e0272460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Okechukwu CE , Colaprico C , Di Mario S , Oko-Oboh AG , Shaholli D , Manai MV , et al. The relationship between working night shifts and depression among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare. 2023; 11( 7): 937. doi:10.3390/healthcare11070937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Morrissette DA . Twisting the night away: a review of the neurobiology, genetics, diagnosis, and treatment of shift work disorder. CNS Spectr. 2013; 18( S1): 42– 54. doi:10.1017/S109285291300076X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. World Health Organization . Mental health atlas 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. 68 p. [Google Scholar]

18. Godin I , Kittel F , Coppieters Y , Siegrist J . A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5( 1): 67. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-5-67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Grose-Fifer J , Spielman RM , Dumper K , Jenkins W , Lacombe A , Lovett M , et al. Stress and Illness. Brain and Behavior [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 12]. Available from: https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/psy320/chapter/stress-and-illness/. [Google Scholar]

20. Pourabdian S , Lotfi S , Yazdanirad S , Golshiri P , Hassanzadeh A . Evaluation of the effect of fatigue on the coping behavior of international truck drivers. BMC Psychol. 2020; 8( 1): 1– 10. doi:10.1186/s40359-020-00440-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Firth J , Solmi M , Wootton RE , Vancampfort D , Schuch FB , Hoare E , et al. A meta-review of ‘lifestyle psychiatry’: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19( 3): 360– 80. doi:10.1002/wps.20773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Onyeaka H , Zambrano J , Szlyk H , Celano C , Baiden P , Muoghalu C , et al. Is engagement in physical activity related to its perceived mental health benefits among people with depression and anxiety? America J Lifestyle Med. 2025; 19( 1): 129– 37. doi:10.1177/15598276221116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rosenbaum S , Tiedemann A , Sherrington C , Curtis J , Ward PB . Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014; 75( 9): e964– 74. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang X , Telama R , Hirvensalo M , Hintsanen M , Hintsa T , Pulkki-Råback L , et al. The benefits of sustained leisure-time physical activity on job strain. Occup Med. 2010; 60( 5): 369– 75. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqq019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Park J , Han G . Collectivism and the development of indigenous psychology in South Korea. In: Asia-pacific perspectives on intercultural psychology. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2018. p. 53– 74. doi:10.4324/9781315158358-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jung J , Ko K , Park JB , Lee KJ , Cho YH , Jeong I . Association between commuting time and subjective well-being in relation to regional differences in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2023; 38( 15): e118. doi:10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu QJ , Sun H , Wen ZY , Zhang M , Wang HY , He XH , et al. Shift work and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of epidemiological studies. JCSM. 2022; 18( 2): 653– 62. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mazzetti G , Robledo E , Vignoli M , Topa G , Guglielmi D , SchauFeli WB . Work engagement: a meta-analysis using the job demands-resources model. Psychol Rep. 2023; 126( 3): 1069– 107. doi:10.1177/00332941211051988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gerber M , Pühse U . Do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand J Public Health. 2009; 37( 8): 801– 19. doi:10.1177/1403494809350522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu M , Yin X , Gong Y . Lifestyle factors in the association of shift work and depression and anxiety. JAMA Netw Open. 2023; 6( 8): e2328798. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.28798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Golzar J , Noor S , Tajik O . Convenience sampling. Lit Numer Stud. 2022; 1( 2): 72– 7. doi:10.22034/ijels.2022.162981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Arvidson E , Börjesson M , Ahlborg G , Lindegård A , Jonsdottir IH . The level of leisure time physical activity is associated with work ability. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 855. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kim YH . Korean adolescents’ health risk behaviors and their relationships with the selected psychological constructs. J Adolesc Health. 2001; 29( 4): 298– 306. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00218-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chang SJ , Koh SB , Kang D , Kim SA , Kang MG , Lee CG , et al. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2005; 17( 4): 297– 317. doi:10.35371/kjoem.2005.17.4.297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cohen J . Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2013. 567 p. doi:10.4324/9780203771587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kervezee L , Kosmadopoulos A , Boivin DB . Metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of shift work: the role of circadian disruption and sleep disturbances. Eur J Neurosci. 2020; 51: 396– 412. doi:10.1111/ejn.14216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. James TA , Weiss-Cowie S , Hopton Z , Verhaeghen P , Dotson VM , Duarte A . Depression and episodic memory across the adult lifespan: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2021; 147( 11): 1184– 214. doi:10.1037/bul0000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gao N , Zheng Y , Yang Y , Huang Y , Wang S , Gong Y , et al. Association between shift work and health outcomes in the general population in China: a cross-sectional study. Brain Sci. 2024; 14( 2): 145. doi:10.3390/brainsci14020145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Safieh S , Shochat T , Srulovici E . The mediating role of sleep quality in the relationship between quick-return shift work schedules and work-family conflict: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Res. 2025; 33( 2): e378. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chiang NT , Kao RH , Ma HY , Cho CC . The impact of after-hours messaging on job stress and burnout among Taiwan’s border police: the roles of social support and coping strategies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2025; 12: 587. doi:10.1057/s41599-025-04827-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Solmi M , Basadonne I , Bodini L , Rosenbaum S , Schuch FB , Smith L , et al. Exercise as a transdiagnostic intervention for improving mental health: an umbrella review. J Psychiatr Res. 2025; 184: 91– 181. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2025.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools