Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Importance of Optimism and School Belonging for Children’s Well-Being and Academic Achievement

1 Department of Sport Science, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, 16419, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Nursing, Kyungnam University, Changwon, 51767, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Ryewon Ma. Email: ; Heetae Cho. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: From Tradition to High-Intensity: Examining the Psychological and Emotional Impacts of Exercise Types)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1867-1882. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073087

Received 10 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Academic achievement is an important indicator of student development, and its pursuit should be considered alongside students’ mental health and overall quality of life. Traditional martial arts, as an educational activity that emphasizes self-discipline, communal values, and positive emotional experiences, may support key psychological factors related to learning, such as optimism, school belonging, and well-being. However, how these factors are connected to academic achievement has not been fully examined. Therefore, this study investigated the associations between these psychological resources and academic achievement among students participating in traditional martial arts training. Methods: Data were collected from 331 elementary school students in South Korea who were enrolled in school-based traditional martial arts (taekkyeon) classes. The survey was administered on-site between August and November 2024. Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling with 5000 bootstrap resamples were performed to evaluate the measurement model and test the hypothesized relationships. Results: The measurement model showed acceptable fit, and the structural model supported most of the hypothesized relationships. Optimism showed significant positive associations with school belonging, well-being, and academic achievement; well-being was positively related to academic achievement. However, the direct relationship between school belonging and academic achievement was not statistically significant, suggesting that its influence may operate indirectly through well-being. Conclusion: The findings indicate that participation in traditional martial arts training is related to positive psychological processes and academic outcomes. This study underscores the broader contributions of traditional martial arts to students’ well-being and academic adjustment, highlighting their relevance for school-based programs.Keywords

Education plays a decisive role in equipping students with the competencies necessary to participate in society, enabling them to realize their potential and contribute to broader social development [1]. Accordingly, education and psychology research have sought to gain an in-depth understanding of student development and learning processes by exploring various factors. For example, learning motivation, self-efficacy, academic resilience, and self-regulation [2,3,4,5,6]. Academic achievement is the most direct indicator of student development and educational effectiveness [7]. Beyond reflecting current educational outcomes, academic achievement is regarded as a critical predictor of students’ long-term learning trajectories and future development [8].

Academic achievement has been found to be associated with learning-related, psychological, relational, and emotional resources [9]. Among these resources, optimism, school belonging, and well-being represent the core constructs that describe how students adapt to challenges and thrive in academic environments [10,11]. Specifically, optimism enables students to maintain positive expectations even in the face of challenges and is tied to adaptive interpretations of setbacks, which correspond to stronger academic engagement [12]. School belonging fosters a sense of meaning and connectedness through supportive relationships with peers and teachers, and is connected with higher participation and engagement in learning [13,14]. Student well-being has been linked with effective stress regulation, while life satisfaction correlates with sustained learning motivation and higher achievement [15,16].

From this perspective, physical activity has been increasingly recognized as an educational intervention that strengthens students’ psychological and emotional resources, thereby facilitating their academic achievement [17,18]. In particular, traditional martial arts, unlike conventional forms of physical activity that primarily emphasize competition, skill development, and physical performance, represent a form of mind–body discipline that highlights self-discipline and character development grounded in philosophical and moral cultivation [19]. Moreover, they are distinguished by their emphasis on cultivating educational virtues, such as courtesy, self-discipline, respect, and a sense of community, making them a particularly meaningful form of physical activity that supports learning and personal growth [20,21]. In South Korea, taekkyeon—designated as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO—is a representative example of traditional martial arts characterized by fluid and rhythmic movements, courtesy, respect, and a philosophy of harmony that reflects the Korean cultural values of balance and interconnectedness [22]. The communal training culture and virtue-based discipline in martial arts are connected to relational experiences of acceptance, respect, and validation [23]. Furthermore, positive emotional experiences derived from practice have been associated with greater well-being and optimism [24,25]. These relational and communal processes correspond to a stronger collective identity and an increased sense of belonging. Moreover, it was found that participation in martial arts may exert a direct influence on academic achievement [26].

Although previous studies have addressed these issues, most have examined only specific associations between martial arts and psychological factors, such as optimism, school belonging, and well-being, without exploring how these factors are related to academic achievement [13,24]. In other words, the relationships among these variables cannot be adequately explained by a single factor or direct linear relationship. Instead, it may be better understood as part of a complex psychological process [27]. Therefore, this study examined the relationships between optimism, school belonging, well-being, and academic achievement among students practicing traditional martial arts. By doing so, it aimed to highlight the multidimensional educational value of traditional martial arts and provide an integrated perspective of the relationships between psychological resources and academic outcomes. While previous studies have applied these theories independently to explain motivational or emotional processes, few have integrated them to explain cross-domain psychological transfer from physical to academic contexts. This study extends the theoretical scope by combining relationship motivation theory [28], which explains social motivation through relatedness, with the dynamics of action theory [29] and the spillover theory [30], which together elucidate how motivational energy generated in one domain can carry over to another. By proposing this integrative framework, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how psychological resources cultivated through traditional martial arts may operate within educational settings.

Optimism refers to generalized outcome expectancies, defined as the tendency to believe that good things will happen across life events [31,32,33]. It can be conceptualized from two complementary perspectives [31,34]. Trait optimism reflects a stable and generalized tendency to expect favorable outcomes across life domains [31], whereas state optimism represents a dynamic, context-dependent belief in positive outcomes that may fluctuate over time or across situations. Given that martial arts training involves goal striving, feedback, and mastery experiences that vary across contexts, state optimism provides a more sensitive indicator of the short-term psychological changes fostered through such practice. Previous research has identified associations between optimism and multiple psychological indicators, including mental health, well-being, stress, and depression [35,36,37]. Although empirical evidence is limited, one early study reported that participation in traditional martial arts was associated with greater optimistic attitudes, a finding that has been cited in later reviews [24,38,39].

Optimism functions positively in interpersonal relationships by facilitating bond formation and maintenance, enhancing relationship satisfaction and adjustment, and contributing to social support and the expansion of networks; thus, serving as an important psychological resource [40,41,42]. Psychological resources can play a crucial role in shaping school belonging. Previous research noted that positive personal attributes, including optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and resilience, are significantly associated with school belonging [13], and these attributes collectively serve as important psychological resources [43,44,45]. Individuals with an optimistic disposition are more likely to experience higher levels of bonding and relational satisfaction with their peers, which, in turn, are linked to a stronger sense of school belonging.

Optimism is also related to well-being. Oriol and Miranda [46] found that optimism significantly affects both subjective and psychological well-being. In particular, adolescents with higher optimism tended to experience more positive and fewer negative emotions, suggesting possible links to emotion regulation and psychological adaptation. Thus, optimism functions as an important predictor of quality of life across different age groups and has been reported to enhance positive emotional experiences and mental health [47,48,49]. Duy and Yıldız [50] mentioned that optimism was indirectly associated with subjective well-being through self-esteem as a mediator, indicating optimistic individuals are more likely to form positive self-evaluations, enhancing their overall well-being.

Beyond well-being, optimism is related to academic achievement. El-Anzi [51] noted that students’ optimistic attitudes were linked to greater persistence and problem-solving abilities in personal situations, and a hopeful outlook toward the future may serve as a motivation for academic success. Furthermore, Tetzner and Becker [12] examined the relationships between optimism, self-esteem, and academic achievement and found that optimism serves as a significant predictor in academic contexts and that moderate levels of optimism appeared to be most beneficial for academic achievement. Previous studies have demonstrated that optimism is significantly associated with school belonging [13], well-being [46], and academic achievement [51]. Nevertheless, these relationships have rarely been explored within the context of traditional martial arts. To address this gap, this study examined whether the positive role of optimism observed in educational settings also emerges in this context and proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Optimism is positively associated with school belonging.

H2: Optimism is positively associated with well-being.

H3: Optimism is positively associated with academic achievement.

2.2 School Belonging and Well-Being

School belonging refers to the extent to which students feel psychologically connected to their school community, experience emotional bonds, and have a sense of security [13,52]. This sense of belonging is regarded as being closely related to relatedness, one of the basic psychological needs proposed in self-determination theory, and has been shown to be important for students’ emotional stability, self-efficacy, academic motivation, and social adjustment [13,53,54,55].

School belonging is also closely associated with well-being. Well-being is a key indicator of quality of life, which has become increasingly important in modern society [56,57]. In particular, childhood and adolescence are periods of rapid physical, psychological, and social changes, during which well-being serves as the foundation for healthy development and future life adaptation [58,59]. Tian et al. [60] and Arslan et al. [61] noted that the stronger a student’s sense of belonging at school, the higher their life satisfaction and levels of positive emotions, which ultimately leads to improvements in overall well-being. Both school belonging and student well-being have been found to be associated with traditional martial arts participation. Traditional martial arts emphasize etiquette, respect, and a culture of collective practice, thereby promoting students’ psychological bonding and social connectedness [21]. Such training methods foster relationships through interpersonal interactions and support community development. Moore et al. [24] reported that traditional martial arts training significantly enhanced well-being and alleviated internalized mental health problems (e.g., anxiety and depression), suggesting its potential as a sports-based psychological intervention. Building on previous studies indicating that traditional martial arts training may strengthen students’ sense of school belonging, this study examines the relationships between school belonging and well-being and proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: School belonging is positively associated with well-being.

One of the most important developmental tasks during the school years is academic achievement [62], which goes beyond grades, and has been recognized as having a decisive impact on future academic pathways and career choices [63]. School belonging has been identified as a critical predictor of academic achievement. Sakellariou [14] reported that school belonging is a major factor in enhancing learning attitudes and academic engagement and that intrinsic motivation and engagement are closely related to improved academic performance. Slaten et al. [11] also emphasized that school belonging (school engagement) and educational expectations are important predictors of students’ academic achievement [64].

Similarly, well-being has been found to be related to academic achievement. Previous research has demonstrated that well-being is closely associated with academic success [16]. For example, Cárdenas et al. [65] found that students’ subjective well-being significantly predicted subsequent academic achievement, with lower levels of depression and higher levels of positive emotions corresponding to better performance. Holzer et al. [15] indicated that optimism and perseverance, as subcomponents of well-being in the school context, were significantly related to academic achievement. Specifically, optimism helps students maintain positive expectations about the future during the learning process, whereas perseverance enables them to continue striving toward goals despite difficulties, thereby illustrating the association between well-being and academic success.

The benefits of traditional martial arts training may extend beyond the psychological effects to enhancing academic performance. Pinto-Escalona et al. [26] reported that a school-based intervention using karate, a form of traditional martial art, positively influenced students’ academic achievement, reduced behavioral problems, and improved physical fitness. Notably, children who participated in one year of karate classes showed significant improvements in average grades compared to the control group, providing empirical evidence that traditional martial arts experiences are related to academic benefits. Based on these findings, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H5: School belonging is positively associated with academic achievement.

H6: Well-being is positively associated with academic achievement.

2.4 Relationship Motivation Theory, Dynamics of Action Theory, and Spillover Theory

Relationship motivation theory, derived from self-determination theory, provides a framework for explaining the formation and strengthening of human motivation in social relationships [28]. The theory emphasizes the three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—while focusing on how these needs are satisfied in interpersonal interactions [28,54]. According to Deci and Ryan [28], fulfilling the need for relatedness enhances autonomy and well-being, promoting positive emotions and adaptive behaviors. In the school context, the satisfaction of relatedness is reflected in school belonging, whereby students experience emotional bonds with peers, teachers, and the broader school community [13]. School belonging has also been shown to influence well-being and academic achievement, functioning as a key mediator in these processes [66,67,68]. Optimism, a psychological resource closely associated with interpersonal functioning [40], may interact with school belonging to support students’ well-being. Accordingly, this study hypothesizes that school belonging mediates the relationship between optimism and well-being.

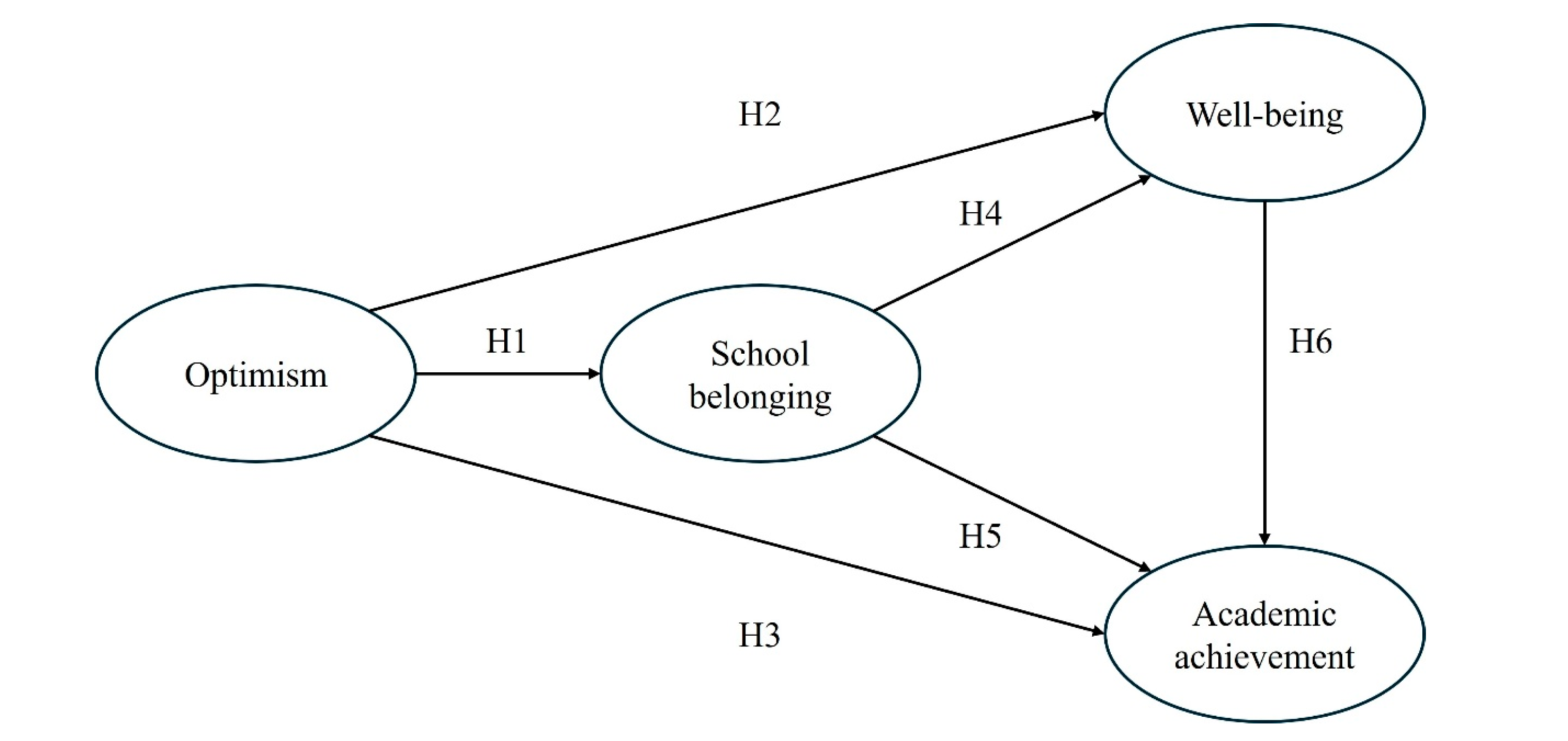

The dynamics of action theory, proposed by Atkinson and Birch [29], conceptualizes motivation as dynamic rather than fixed, shifting across activities over time. Although originally developed to explain short-term task switching in laboratory settings, the theory highlights that motivation continuously evolves as individuals engage in different activities, suggesting that motivation and emotions generated in one activity may influence subsequent behaviors over time [69]. Complementing this view, the spillover theory [30] posits that experiences and resources acquired in one life domain can transfer to other psychologically or functionally connected domains. Domains of life are interdependent, and emotions, motivation, and behavioral tendencies cultivated in one domain may shape attitudes and outcomes in another through shared psychological processes [30]. From this perspective, traditional martial arts training can be regarded as a real-world domain for examining motivational and emotional resources, and within the spillover framework, such resources may be conceptually linked to other domains [70]. In particular, optimism, school belonging, and well-being have been conceptually associated with the context of traditional martial arts, and these psychological resources may extend beyond the physical and social domains [21,24,26,38]. Such processes may be related to students’ academic achievement, reflecting potential positive spillover effects across life domains. Based on this theoretical background, the following hypotheses were proposed. Fig. 1 illustrates a research model.

H7: School belonging mediates the relationship between optimism and well-being.

H8: School belonging and well-being sequentially mediate the relationship between optimism and academic achievement.

Figure 1: A hypothesized model.

3.1 Participants and Procedures

This study targeted elementary school students enrolled in school-based traditional martial arts (i.e., taekkyeon) classes in Chungju, South Korea. Data were collected from four elementary schools that agreed to participate in this study. Data were gathered on-site in classrooms between August and November 2024 using self-report questionnaires. Students who did not return parental consent forms were excluded, and no additional exclusion criteria were applied. Prior to data collection, written informed consent was obtained from parents, and assent was obtained from all child participants. Students were informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, confidentiality safeguards, and voluntary participation. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sungkyunkwan University approved all study procedures (reference no. SKKU-2024-08-018), and no ethical concerns arose during the process. A total of 331 students ultimately participated in the study. The sample comprised 172 boys (52%) and 159 girls (48%), with a mean age of 8.34 years (SD = 0.58). The average duration of taekkyeon training was 0.79 years (SD = 0.46).

This study used the state optimism measure developed by Millstein et al. [34] to measure optimism. Given the contextual nature of this study, a state-level measure was employed to better capture participants’ situational and short-term motivational experiences that may fluctuate according to factors such as traditional martial arts training and school life. This scale consists of seven items with a single-factor structure and assesses an individual’s state-level optimism. For example, “I am feeling optimistic about my future”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

School belonging was measured using the School Belongingness Scale [71]. While the scale originally consisted of two subfactors (school acceptance and school exclusion), only the school acceptance dimension was employed in this study to assess the positive aspect of school belonging. For example, “I see myself as a part of this school”. Responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 4 = almost always).

Well-being was measured using the flourishing scale developed by Diener et al. [72]. This instrument assesses overall well-being and social functioning as a single dimension, and consists of eight items. For example, “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life”. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Academic achievement was assessed using a modified version of the goal orientation scale developed by Midgley et al. [73]. The original scale consisted of three dimensions (task, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance), while only the task goal orientation subscale was employed in this study. Although task goal orientation primarily reflects students’ motivational tendencies rather than direct academic outcomes, previous studies have demonstrated that mastery- or task-oriented goals are strongly associated with higher levels of academic achievement and performance [74,75]. Accordingly, task goal orientation was used as a proxy indicator of academic achievement, reflecting students’ motivation to master learning tasks that facilitate academic success. The scale includes six items, such as “I like schoolwork that I will learn from even if I make a lot of mistakes”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = very true).

First, we screened the data for violations of the assumptions. Cases with multivariate outliers were identified and excluded using the Mahalanobis distance [76]. Consequently, 27 multivariate outliers were excluded, leaving 304 valid responses for the final analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the measurement model. Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with acceptable thresholds set at CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.90 and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 [77]. After confirming an adequate model fit, construct reliability and validity were examined. Reliability was evaluated through factor loadings and composite reliability (CR), with CR values ≥ 0.70 considered acceptable [76]. Convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE), with values ≥ 0.50 regarded as satisfactory [76,78]. Discriminant validity was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT), with HTMT values < 0.85 indicating sufficient discriminant validity [79]. Subsequently, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to test the hypothesized relationships. Standard errors and confidence intervals were estimated using 5000 bootstrap resamples [80]. All analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The results of the CFA indicated that the measurement model showed an acceptable fit: χ2(293) = 620.41, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06. Next, the internal consistency of the measurement models was assessed. The CR values ranged from 0.845 for school belonging to 0.941 for well-being, indicating satisfactory reliability (CR ≥ 0.70). The AVE was 0.522 for school belonging and 0.665 for well-being, both exceeding the recommended threshold (AVE ≥ 0.50) (Table 1). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and correlation coefficients among the latent variables were computed, and the results are presented (Table 2). Finally, discriminant validity was supported (HTMT < 0.85) (Table 3).

Table 1: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | λ | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism (Opt) | Opt1 | 0.746 | 0.906 | 0.580 |

| Opt2 | 0.794 | |||

| Opt3 | 0.820 | |||

| Opt4 | 0.705 | |||

| Opt5 | 0.729 | |||

| Opt6 | 0.791 | |||

| Opt7 | 0.740 | |||

| School belonging (SB) | SB1 | 0.722 | 0.845 | 0.522 |

| SB2 | 0.731 | |||

| SB3 | 0.723 | |||

| SB4 | 0.692 | |||

| SB5 | 0.742 | |||

| Well-being (WB) | WB1 | 0.816 | 0.941 | 0.665 |

| WB2 | 0.852 | |||

| WB3 | 0.843 | |||

| WB4 | 0.817 | |||

| WB5 | 0.853 | |||

| WB6 | 0.825 | |||

| WB7 | 0.773 | |||

| WB8 | 0.739 | |||

| Academic achievement (AA) | AA1 | 0.827 | 0.911 | 0.632 |

| AA2 | 0.839 | |||

| AA3 | 0.740 | |||

| AA4 | 0.857 | |||

| AA5 | 0.750 | |||

| AA6 | 0.748 |

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and correlations among the constructs.

| Constructs | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Optimism | 4.07 | 0.83 | - | |||

| 2. School belonging | 4.06 | 0.88 | 0.592*** | - | ||

| 3. Well-being | 4.11 | 0.83 | 0.837*** | 0.778*** | - | |

| 4. Academic achievement | 3.92 | 0.97 | 0.734*** | 0.662*** | 0.818*** | - |

Table 3: HTMT analysis results.

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Optimism | ||||

| 2. School belonging | 0.598 | |||

| 3. Well-being | 0.845 | 0.783 | ||

| 4. Academic achievement | 0.744 | 0.655 | 0.809 |

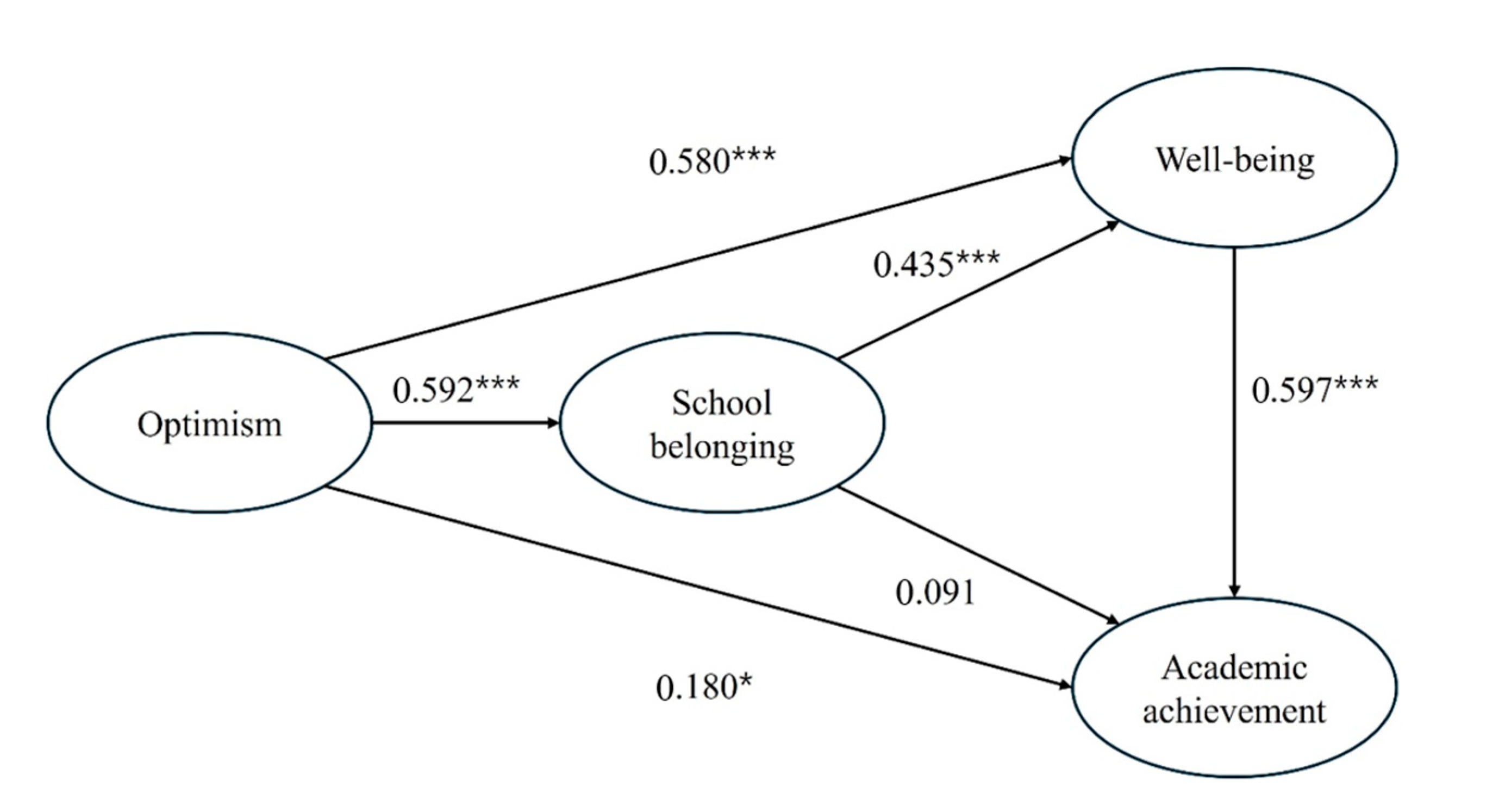

The results of the SEM indicated that the structural model showed an acceptable fit: χ2(293) = 620.41, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06. Hypothesis testing was evaluated based on path coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), z-statistics, and significance levels (p). First, optimism had a positive effect on school belonging (β = 0.592, SE = 0.071, z = 8.298, p < 0.001). Optimism positively influenced well-being (β = 0.580, SE = 0.061, z = 10.043, p < 0.001) and had a significant direct effect on academic achievement (β = 0.180, SE = 0.112, z = 2.038, p < 0.05). Thus, H1, H2, and H3 were supported. Next, school belonging showed a significant positive effect on well-being (β = 0.435, SE = 0.058, z = 7.987, p < 0.001), but no direct effect on academic achievement (β = 0.091, SE = 0.100, z = 1.157, p > 0.05). Therefore, H4 was supported, whereas H5 was rejected. Well-being positively affected academic achievement (β = 0.597, SE = 0.147, z = 4.837, p < 0.001). Hence, H6 was supported. Additionally, indirect effects were tested using bootstrapping. The results showed that the indirect effect of optimism on well-being through school belonging was significant, as the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. Finally, the sequential mediation effect of optimism on academic achievement through school belonging and well-being was significant as the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (Table 4). The standardized path coefficients of the final structural model are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: A structural model. Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Table 4: Results of structural equation modeling.

| Direct Effect | Path | β | SE | z-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Optimism → School belonging | 0.592 | 0.071 | 8.298*** |

| H2 | Optimism → Well-being | 0.580 | 0.061 | 10.043*** |

| H3 | Optimism → Academic achievement | 0.180 | 0.112 | 2.038* |

| H4 | School belonging → Well-being | 0.435 | 0.058 | 7.987*** |

| H5 | School belonging → Academic achievement | 0.091 | 0.100 | 1.157 |

| H6 | Well-being → Academic achievement | 0.597 | 0.147 | 4.837*** |

| Indirect Effect | Path | β | SE | 95% CI |

| H7 | Optimism → School belonging → Well-being | 0.257*** | 0.077 | 0.152, 0.458 |

| H8 | Optimism → School belonging → Well-being → Academic achievement | 0.153*** | 0.072 | 0.088, 0.386 |

The primary purpose of this study was to analyze the relationships among optimism, school belonging, well-being, and academic achievement in students who practiced traditional martial arts at school, based on relationship motivation theory [28], the dynamics of action theory [29,69], and the spillover theory [30]. Overall, seven of the eight hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H6, H7, and H8) were supported, indicating that belonging is associated with positive behaviors and well-being, and that motivation generated in one activity may transfer to another, ultimately relating to overall achievement. The findings advance theoretical understanding by integrating these three motivational frameworks into a unified explanatory model. Specifically, the results suggest that relatedness-based motivation and dynamic motivational shifts may jointly explain how psychological resources derived from traditional martial arts can spill over into academic contexts. This integrative approach extends the application of these theories beyond their traditional domains, highlighting the cross-domain dynamics of psychological and emotional processes in educational psychology.

Specifically, this study found that optimism was positively associated with school belonging among students who participated in traditional martial arts classes (H1). Optimism is known to facilitate positive emotions and social interactions, as well as support relationship maintenance [40,41]. These characteristics may have contributed to strengthening interpersonal bonds and enhancing belonging in the school context. The results also showed that optimism was positively associated with student well-being (H2). Previous research has reported that adolescents with optimistic dispositions experience higher life satisfaction and better psychological well-being, with fewer psychosocial problems [81]. For instance, Ho et al. [48] demonstrated that optimism was related to the positive aspects of well-being and reduced the negative aspects of the relationship between meaning in life and well-being among adolescents. These findings suggest that positive future expectations, happiness, and life satisfaction may contribute to the maintenance of mental health during adolescence. Furthermore, optimism was positively associated with academic achievement (H3). This result indicates that optimistic students tend to perceive academic tasks positively, show less discouragement in the face of failure, and sustain their motivation to learn [12]. These results are consistent with prior findings that optimism is linked to persistence and self-regulation in stressful academic contexts, thereby relating to achievement-related behaviors [51].

This study also explored the relationship between school belonging and student well-being. Consistent with the findings reported by Arslan et al. [61], the results of this study showed that school belonging was positively associated with student well-being. Moreover, school belonging appeared to function as a positive predictor of well-being (H4). Arslan [82] noted that school belonging enhanced well-being by reducing loneliness among students. Together, these results highlight that school belonging alleviates emotional isolation, thereby improving students’ overall quality of life.

In contrast, school belonging did not significantly predict academic achievement (H5). This outcome may be due to the inclusion of well-being in the model, as we found a strong positive association between well-being and academic achievement (H6). The pronounced link between well-being and academic achievement may have attenuated the apparent effect of school belonging. This result aligns with previous research demonstrating that well-being is a key psychological resource associated with academic [83,84,85]. Therefore, well-being appears to be an important psychological resource associated with academic achievement.

School belonging also significantly mediated the relationship between optimism and well-being (H7). This extends the original framework of relationship motivation theory, suggesting that optimistic individuals form positive interpersonal relationships at school and experience a greater sense of belonging, ultimately enhancing their overall well-being [13,28]. Previous studies have shown that optimism is associated with warm and proactive interpersonal styles that facilitate positive social interactions and support [86]. In the school context, school belonging (an indicator of positive social relationships) has been shown to mediate the link between well-being-related factors and well-being outcomes [66,67,68,87]. Thus, the findings empirically support the idea that optimism is related to well-being not only directly, but also indirectly through school belonging.

Finally, the sequential link from optimism to academic achievement through school belonging and well-being was supported (H8). This result aligns with the dynamics of action theory, which emphasizes the transfer of motivation across activities, showing that psychological resources and relational factors developed in one domain (traditional martial arts) can extend to another domain (academics) [29]. The spillover theory [30] suggests that emotions and motivation generated in one life domain can transfer to another that is psychologically or functionally connected. Likewise, Verfuerth et al. [88] highlighted that such cross-domain transfer depends on the integration of these experiences into one’s sense of self. In this regard, the findings resonate with those of Cho and Chiu [89], who reported that positive psychological resources developed during leisure activities can be transferred to academic motivation. Taken together, these results suggest that optimism, school belonging, and well-being are psychological factors that are each associated with academic development among elementary students with experience in traditional martial arts.

5.1 Theoretical and Practical Implications

Previous studies have examined the relationships between traditional martial arts training and students’ psychological variables [24] as well as academic achievement [26]. However, few studies have investigated the relationships among these variables. This study provided empirical evidence supporting the educational value of traditional martial arts training for students. In particular, the findings suggest that positive expectations for the future formed through martial arts experiences are related to higher levels of school belonging and well-being, which, in turn, are linked with better academic achievement. These findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological and social implications of traditional martial arts and the processes through which these effects may occur in educational settings.

Most previous studies have emphasized academic activities and environmental factors as predictors of academic achievement [90,91]. In contrast, this study identified that traditional martial arts experiences may be related to academic achievement, thereby providing new implications for theoretical discussion. Furthermore, this study focused on relatedness among basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness). The results revealed a pattern of associations in which optimism was related to well-being through the fulfillment of relatedness needs, and well-being was, in turn, associated with academic achievement. Importantly, this research extended the application of both relationship motivation theory [28], the dynamics of action theory [29], and the spillover theory [30], offering an integrated explanation of the relationships among the constructs and contributing to theoretical advancement in sports pedagogy and psychology.

This study also suggests that traditional martial arts practice may function as a meaningful pedagogical approach associated with both students’ well-being and academic achievement. Accordingly, schools should consider expanding the inclusion of traditional martial arts programs in physical education classes and extracurricular activities. In the long term, martial arts could be incorporated into the formal curriculum. Educators should design martial arts classes not merely as physical skill training, but as a platform that foster mutual respect, cooperation, and peer support. For instance, teachers may organize team-based tasks that encourage students to exchange feedback and build connectedness, which can, in turn, enhance their psychological security and motivation to learn [92]. Beyond these educational applications, the findings further indicate that the practice of traditional martial arts contributes to students’ mental health and overall quality of life, supporting the motivational transfer of positive resources to academic contexts. This study’s integrated theoretical framework provides a novel perspective that connects physical, emotional, and academic dimensions of student development, thereby clarifying the theoretical contribution of traditional martial arts research to the broader field of motivation and educational psychology.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study provided new insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a cross-sectional study, causal relationships between the variables cannot be demonstrated. In addition, potentially influential background factors, such as socioeconomic status, parental education level, initial motivation, and previous athletic experience, were not controlled, and students’ experiences in other extracurricular activities were not considered. Second, the participants were limited to South Korean elementary school students practicing taekkyeon, and variations in the duration and intensity of martial arts training were not examined due to the lack of standardized measures across programs, which may affect the generalizability and magnitude of the observed effects. Finally, academic achievement was assessed through self-reported measures; future studies should incorporate objective indicators such as grades, standardized test scores, or attendance records. To address these limitations, future research should employ longitudinal designs, include more diverse samples, and consider different types of physical activities and cultural contexts to more accurately examine the effects of traditional martial arts training.

This study examines how optimism, school belonging, and well-being are related to the academic achievement of elementary school students participating in traditional martial arts training, highlighting the broader developmental value of such participation. The findings suggest that these programs may cultivate affective resources that enhance students’ engagement and functioning within the school environment, thereby linking psychological states to academic-relevant orientations. By integrating key psychological constructs within a sport-based educational context, the study advances understanding of how culturally embedded physical activity contributes to students’ holistic development. Collectively, the results underscore the potential of traditional martial arts as a structured school activity that strengthens students’ sense of connection and capacity to pursue academic goals, providing an empirically grounded foundation for future research on how culturally meaningful physical education programs can promote both well-being and learning outcomes.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Geonho Na, Ryewon Ma, and Heetae Cho; methodology, Geonho Na; validation, Ryewon Ma and Heetae Cho; formal analysis, Geonho Na and Heetae Cho; data curation, Geonho Na and Heetae Cho; writing—original draft preparation, Geonho Na; writing—review and editing, Ryewon Ma and Heetae Cho; visualization, Ryewon Ma; supervision, Heetae Cho. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and during the current study are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Heetae Cho, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sungkyunkwan University (reference no. SKKU-2024-08-018).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from parents, and assent was obtained from all child participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. King RB , Wang H , McInerney DM . Students who want to contribute to society have optimal learning-related outcomes. J Exp Educ. 2024; 92( 3): 466– 84. doi:10.1080/00220973.2022.2146039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alemayehu L , Chen HL . The influence of motivation on learning engagement: the mediating role of learning self-efficacy and self-monitoring in online learning environments. Interact Learn Environ. 2023; 31( 7): 4605– 18. doi:10.1080/10494820.2021.1977962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang F , King RB , Fu L , Chai CS , Leung SO . Overcoming adversity: exploring the key predictors of academic resilience in science. Int J Sci Educ. 2024; 46( 4): 313– 37. doi:10.1080/09500693.2023.2231117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu H , Li S , Zheng J , Guo J . Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020; 25( 1): 1742964. doi:10.1080/10872981.2020.1742964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zheng B , Chang C , Lin CH , Zhang Y . Self-efficacy, academic motivation, and self-regulation: how do they predict academic achievement for medical students? Med Sci Educ. 2021; 31( 1): 125– 30. doi:10.1007/s40670-020-01143-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ng-Knight T , Gilligan-Lee KA , Massonnié J , Gaspard H , Gooch D , Querstret D , et al. Does Taekwondo improve children’s self-regulation? If so, how? A randomized field experiment. Dev Psychol. 2022; 58( 3): 522– 34. doi:10.1037/dev0001307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Basileo LD , Lyons ME , Toth MD . Leading indicators of academic achievement: investigating the predictive validity of an observation instrument in a large district. Sage Open. 2024; 14( 2): 21582440241261119. doi:10.1177/21582440241261119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang S , Luo B . Academic achievement prediction in higher education through interpretable modeling. PLoS One. 2024; 19( 9): e0309838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0309838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tindle R , Abo Hamza EG , Helal AA , Ayoub AEA , Moustafa AA . A scoping review of the psychosocial correlates of academic performance. Rev Educ. 2022; 10( 3): e3371. doi:10.1002/rev3.3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ling X , Chen J , Chow DHK , Xu W , Li Y . The “trade-off” of student well-being and academic achievement: a perspective of multidimensional student well-being. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 772653. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.772653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Slaten CD , Ferguson JK , Allen KA , Brodrick DV , Waters L . School belonging: a review of the history, current trends, and future directions. Educ Dev Psychol. 2016; 33( 1): 1– 15. doi:10.1017/edp.2016.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tetzner J , Becker M . Think positive? Examining the impact of optimism on academic achievement in early adolescents. J Pers. 2018; 86( 2): 283– 95. doi:10.1111/jopy.12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Allen K , Kern ML , Vella-Brodrick D , Hattie J , Waters L . What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educ Psychol Rev. 2018; 30( 1): 1– 34. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sakellariou C . Reciprocal longitudinal effects between sense of school belonging and academic achievement: quasi-experimental estimates using United States primary school data. Front Psychol. 2025; 15: 1478320. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1478320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Holzer J , Bürger S , Lüftenegger M , Schober B . Revealing associations between students’ school-related well-being, achievement goals, and academic achievement. Learn Individ Differ. 2022; 95: 102140. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kaya M , Erdem C . Students’ well-being and academic achievement: a meta-analysis study. Child Indic Res. 2021; 14( 5): 1743– 67. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09821-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Muntaner-Mas A , Morales JS , Martínez-de-Quel Ó , Lubans DR , García-Hermoso A . Acute effect of physical activity on academic outcomes in school-aged youth: a systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2024; 34( 1): e14479. doi:10.1111/sms.14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Watson A , Timperio A , Brown H , Best K , Hesketh KD . Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017; 14( 1): 114. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0569-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cox JC . Traditional Asian martial arts training: a review. Quest. 1993; 45( 3): 366– 88. doi:10.1080/00336297.1993.10484094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bowman P . Making martial arts history matter. In: Brown D , Jennings G , editors. Martial arts in Asia. London, UK: Routledge; 2016. p. 915– 33. doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1212842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Martinkova I , Parry J , Vágner M . The contribution of martial arts to moral development. Ido Mov Cult. 2019; 19( 1): 1– 8. doi:10.14589/ido.19.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Park JK , Tae HS , Ok G , Kwon SY . The heritagization and institutionalization of taekkyeon: an intangible cultural heritage. Int J Hist Sport. 2018; 35( 15–16): 1555– 66. doi:10.1080/09523367.2019.1620734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cao X , Lyu H . Motivational drivers and sense of belonging: unpacking the persistence in Chinese martial arts practice among international practitioners. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1403327. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1403327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Moore B , Dudley D , Woodcock S . The effect of martial arts training on mental health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2020; 24( 4): 402– 12. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.06.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Moore B , Woodcock S , Dudley D . Well-being warriors: a randomized controlled trial examining the effects of martial arts training on secondary students’ resilience. Br J Educ Psychol. 2021; 91( 4): 1369– 94. doi:10.1111/bjep.12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pinto-Escalona T , Gobbi E , Valenzuela PL , Bennett SJ , Aschieri P , Martin-Loeches M , et al. Effects of a school-based karate intervention on academic achievement, psychosocial functioning, and physical fitness: a multi-country cluster randomized controlled trial. J Sport Health Sci. 2024; 13( 1): 90– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2021.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pinto-Escalona T , Valenzuela PL , Martin-Loeches M , Martinez-de-Quel O . Individual responsiveness to a school-based karate intervention: an ancillary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022; 32( 8): 1249– 57. doi:10.1111/sms.14167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Deci EL , Ryan RM . Autonomy and need satisfaction in close relationships: relationships motivation theory. In: Weinstein N , editor. Human motivation and interpersonal relationships. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2014. p. 53– 73. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8542-6_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Atkinson JW , Birch D . On the dynamics of action. Tijdschr Voor De Psychol En Haar Grensgebieden. 1970; 25( 2): 83– 94. [Google Scholar]

30. Grzywacz JG , Marks NF . Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: an ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000; 5( 1): 111– 26. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Carver CS , Scheier MF , Segerstrom SC . Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30( 7): 879– 89. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kluemper DH , Little LM , DeGroot T . State or trait: effects of state optimism on job-related outcomes. J Organ Behav. 2009; 30( 2): 209– 31. doi:10.1002/job.591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Scheier MF , Carver CS . Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985; 4( 3): 219– 47. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Millstein RA , Chung WJ , Hoeppner BB , Boehm JK , Legler SR , Mastromauro CA , et al. Development of the state optimism measure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019; 58: 83– 93. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Asiamah N , Mensah HK , Ansah EW , Eku E , Ansah NB , Danquah E , et al. Association of optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience with life engagement among middle-aged and older adults with severe climate anxiety: sensitivity of a path model. J Affect Disord. 2025; 380: 607– 19. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2025.03.180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lee LO , James P , Zevon ES , Kim ES , Trudel-Fitzgerald C , Spiro A 3rd , et al. Optimism is associated with exceptional longevity in 2 epidemiologic cohorts of men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019; 116( 37): 18357– 62. doi:10.1073/pnas.1900712116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Man KH , Ho GWK . Associations between optimism and mental health in postradiotherapy cancer survivors: a cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open. 2025; 15( 7): e093983. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-093983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kurian M , Verdi MP , Caterino LC , Kulhavy RW . Relating scales on the children’s personality questionnaire to training time and belt rank in ATA taekwondo. Percept Mot Skills. 1994; 79( 2): 904– 6. doi:10.2466/pms.1994.79.2.904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Vertonghen J , Theeboom M . The social-psychological outcomes of martial arts practise among youth: a review. J Sports Sci Med. 2010; 9( 4): 528– 37. [Google Scholar]

40. Andersson MA . Dispositional optimism and the emergence of social network diversity. Sociol Q. 2012; 53( 1): 92– 115. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01227.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Carver CS , Scheier MF . Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014; 18( 6): 293– 9. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Rius-Ottenheim N , Kromhout D , van der Mast RC , Zitman FG , Geleijnse JM , Giltay EJ . Dispositional optimism and loneliness in older men. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012; 27( 2): 151– 9. doi:10.1002/gps.2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Harris PR , Richards A , Bond R . Individual differences in spontaneous self-affirmation and mental health: relationships with self-esteem, dispositional optimism and coping. Self Identity. 2023; 22( 3): 351– 78. doi:10.1080/15298868.2022.2099455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Karademas EC . Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: the mediating role of optimism. Pers Individ Differ. 2006; 40( 6): 1281– 90. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kleiman EM , Chiara AM , Liu RT , Jager-Hyman SG , Choi JY , Alloy LB . Optimism and well-being: a prospective multi-method and multi-dimensional examination of optimism as a resilience factor following the occurrence of stressful life events. Cogn Emot. 2017; 31( 2): 269– 83. doi:10.1080/02699931.2015.1108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Oriol X , Miranda R . The prospective relationships between dispositional optimism and subjective and psychological well-being in children and adolescents. Appl Res Qual Life. 2024; 19( 1): 195– 214. doi:10.1007/s11482-023-10237-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Daukantaitė D , Zukauskiene R . Optimism and subjective well-being: affectivity plays a secondary role in the relationship between optimism and global life satisfaction in the middle-aged women. longitudinal and cross-cultural findings. J Happiness Stud. 2012; 13( 1): 1– 16. doi:10.1007/s10902-010-9246-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ho MY , Cheung FM , Cheung SF . The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Pers Individ Differ. 2010; 48( 5): 658– 63. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ju H , Shin JW , Kim CW , Hyun MH , Park JW . Mediational effect of meaning in life on the relationship between optimism and well-being in community elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013; 56( 2): 309– 13. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Duy B , Ali Yıldız M . The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol. 2019; 38( 6): 1456– 63. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9698-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. El-Anzi FO . Academic achievement and its relationship with anxiety, self-esteem, optimism, and pessimism in Kuwaiti students. Soc Behav Pers. 2005; 33( 1): 95– 104. doi:10.2224/sbp.2005.33.1.95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Goodenow C . Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: relationships to motivation and achievement. J Early Adolesc. 1993; 13( 1): 21– 43. doi:10.1177/0272431693013001002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Anderman EM . School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. J Educ Psychol. 2002; 94( 4): 795– 809. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Deci EL , Ryan RM . The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000; 11( 4): 227– 68. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Acitelli LK , Josselson R . The space between us: exploring the dimensions of human relationships. J Marriage Fam. 1996; 58( 4): 1042. doi:10.2307/353994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Rogers DS , Duraiappah AK , Antons DC , Munoz P , Bai X , Fragkias M , et al. A vision for human well-being: transition to social sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2012; 4( 1): 61– 73. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2012.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ruggeri K , Garcia-Garzon E , Maguire Á , Matz S , Huppert FA . Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020; 18( 1): 192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Anderson NW , Eisenberg D , Halfon N , Markowitz A , Moore KA , Zimmerman FJ . Trends in measures of child and adolescent well-being in the US from 2000 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022; 5( 10): e2238582. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Kaçmaz C , Çelik OT . Life satisfaction in adolescence: a bibliometric analysis. Child Indic Res. 2025; 18( 5): 1927– 55. doi:10.1007/s12187-025-10249-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Tian L , Zhang L , Huebner ES , Zheng X , Liu W . The longitudinal relationship between school belonging and subjective well-being in school among elementary school students. Appl Res Qual Life. 2016; 11( 4): 1269– 85. doi:10.1007/s11482-015-9436-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Arslan G , Allen KA , Ryan T . Exploring the impacts of school belonging on youth wellbeing and mental health among Turkish adolescents. Child Indic Res. 2020; 13( 5): 1619– 35. doi:10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Crede J , Wirthwein L , McElvany N , Steinmayr R . Adolescents’ academic achievement and life satisfaction: the role of parents’ education. Front Psychol. 2015; 6: 52. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Rana R , Mahmood N . The relationship between test anxiety and academic achievement. Bull Educ Res. 2010; 32( 2): 63– 74. [Google Scholar]

64. Sirin SR , Rogers-Sirin L . Exploring school engagement of middle-class African American adolescents. Youth Soc. 2004; 35( 3): 323– 40. doi:10.1177/0044118x03255006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Cárdenas D , Lattimore F , Steinberg D , Reynolds KJ . Youth well-being predicts later academic success. Sci Rep. 2022; 12: 2134. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05780-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ahmadi F , Ahmadi S . School-related predictors of students’ life satisfaction: the mediating role of school belongingness. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2020; 24( 2): 196– 205. doi:10.1007/s40688-019-00262-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Baş G . How to improve academic achievement of students? The influence of academic emphasis on academic achievement with the mediating roles of school belonging, student engagement, and academic resilience. Psychol Sch. 2025; 62( 1): 313– 35. doi:10.1002/pits.23326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Palikara O , Castro-Kemp S , Gaona C , Eirinaki V . The mediating role of school belonging in the relationship between socioemotional well-being and loneliness in primary school age children. Aust J Psychol. 2021; 73( 1): 24– 34. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1882270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Kuhl J , Blankenship V . The dynamic theory of achievement motivation: from episodic to dynamic thinking. Psychol Rev. 1979; 86( 2): 141– 51. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.86.2.141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Yukhymenko-Lescroart MA . Sport-to-school spillover effects of passion for sport: the role of identity in academic performance. Psychol Rep. 2022; 125( 3): 1469– 93. doi:10.1177/00332941211006925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Arslan G , Duru E . Initial development and validation of the school belongingness scale. Child Indic Res. 2017; 10( 4): 1043– 58. doi:10.1007/s12187-016-9414-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Diener E , Wirtz D , Tov W , Kim-Prieto C , Choi DW , Oishi S , et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010; 97( 2): 143– 56. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Midgley C , Kaplan A , Middleton M , Maehr ML , Urdan T , Anderman LH , et al. The development and validation of scales assessing students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemp Educ Psychol. 1998; 23( 2): 113– 31. doi:10.1006/ceps.1998.0965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Senko C , Hulleman CS , Harackiewicz JM . Achievement goal theory at the crossroads: old controversies, current challenges, and new directions. Educ Psychol. 2011; 46( 1): 26– 47. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.538646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Steinmayr R , Spinath B . The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learn Individ Differ. 2009; 19( 1): 80– 90. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Hair JF , Black WC , Babin BJ , Anderson RE . Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

77. Kline RB . Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications; 2023. [Google Scholar]

78. Fornell C , Larcker DF . Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981; 18( 1): 39– 50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Henseler J , Ringle CM , Sarstedt M . A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015; 43( 1): 115– 35. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Hayes AF . Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

81. Rincón Uribe FA , Neira Espejo CA , da Silva Pedroso J . The role of optimism in adolescent mental health: a systematic review. J Happiness Stud. 2022; 23( 2): 815– 45. doi:10.1007/s10902-021-00425-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Arslan PD . School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness. Aust J Psychol. 2021; 73( 1): 70– 80. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Bücker S , Nuraydin S , Simonsmeier BA , Schneider M , Luhmann M . Subjective well-being and academic achievement: a meta-analysis. J Res Pers. 2018; 74: 83– 94. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Ng ZJ , E Huebner S , J Hills K . Life satisfaction and academic performance in early adolescents: evidence for reciprocal association. J Sch Psychol. 2015; 53( 6): 479– 91. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Suldo S , Thalji A , Ferron J . Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. J Posit Psychol. 2011; 6( 1): 17– 30. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.536774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Smith TW , Ruiz JM , Cundiff JM , Baron KG , Nealey-Moore JB . Optimism and pessimism in social context: an interpersonal perspective on resilience and risk. J Res Pers. 2013; 47( 5): 553– 62. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Arslan G , Allen KA . School victimization, school belongingness, psychological well-being, and emotional problems in adolescents. Child Indic Res. 2021; 14( 4): 1501– 17. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09813-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Verfuerth C , Jones CR , Gregory-Smith D , Oates C . Understanding contextual spillover: using identity process theory as a lens for analyzing behavioral responses to a workplace dietary choice intervention. Front Psychol. 2019; 10: 345. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Cho H , Chiu W . The role of leisure centrality in university students’ self-satisfaction and academic intrinsic motivation. Asia Pac Educ Res. 2021; 30( 2): 119– 30. doi:10.1007/s40299-020-00519-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Costa A , Moreira D , Casanova J , Azevedo  , Gonçalves A , Oliveira Í , et al. Determinants of academic achievement from the middle to secondary school education: a systematic review. Soc Psychol Educ. 2024; 27( 6): 3533– 72. doi:10.1007/s11218-024-09941-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Credé M , Kuncel NR . Study habits, skills, and attitudes: the third pillar supporting collegiate academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008; 3( 6): 425– 53. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00089.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Kaendler C , Wiedmann M , Rummel N , Spada H . Teacher competencies for the implementation of collaborative learning in the classroom: a framework and research review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2015; 27( 3): 505– 36. doi:10.1007/s10648-014-9288-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools