Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Well-Being through Psychological Resilience and Social Capital: An Empirical Study of Female Entrepreneurs in the Long-Term Care Industry

Department of Gerontology and Health Care Management, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan, 33303, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chia-Hui Hou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Social and Behavioral Determinants of Mental Health: From Theory to Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 2007-2022. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073748

Received 24 September 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: With the rapid aging of populations worldwide, the long-term care (LTC) industry has become a critical arena for both social welfare and entrepreneurial development, particularly among women who play a leading role in caregiving enterprises. However, female LTC entrepreneurs often face emotional strain and limited social resources that affect their professional well-being. This study investigates the effects of psychological resilience and social capital on the well-being of female entrepreneurs in the long-term care (LTC) industry and examines the mediating role of entrepreneurial competence. Methods: A mixed-methods design was employed. Quantitative data were collected from 73 female LTC entrepreneurs in Taiwan through structured questionnaires, and correlation, regression, and mediation analyses were conducted. Complementary qualitative interviews with eight entrepreneurs provided deeper insights into how resilience and social resources are mobilized in entrepreneurial practice. Results: Psychological resilience and social capital were positively associated with well-being (β = 0.41, p < 0.001; β = 0.36, p = 0.002), jointly explaining 47% of its variance. Entrepreneurial competence partially mediated the resilience–well-being relationship (indirect effect = 0.18, 95% CI [0.07, 0.32]). These effects were statistically and practically meaningful. Conclusion: Psychological resilience and social capital jointly enhance the well-being of female LTC entrepreneurs, with entrepreneurial competence serving as a partial mediator. The results suggest that fostering both inner strength and social connectedness can promote sustainable well-being and professional growth in the long-term care sector.Keywords

1.1 Population Aging and the Long-Term Care Industry

The world is entering an aging society at an unprecedented pace. According to the World Health Organization [1], by 2030, one in six people worldwide will be over the age of 60. Taiwan is no exception: In 2023, the population aged 65 and above had already reached 18% of the total population, and it is projected to exceed 21% by 2026, formally entering the stage of a super-aged society [2]. This demographic transformation directly increases the demand for long-term care (LTC) and brings multiple social and industrial challenges.

Since 2017, Taiwan has promoted the “LTC 2.0” policy, focusing on home- and community-based services, the establishment of ABC LTC service stations, and the innovation of diversified service models [3]. By the end of 2022, the national LTC service coverage rate had exceeded 68%, showing that both demand and supply are expanding simultaneously. Related studies also indicate that the development of the LTC industry is not merely an extension of medical and social welfare policies but an emerging field that integrates entrepreneurship, health care, and social innovation [4].

In this context, the role of female entrepreneurs has become increasingly prominent. According to the GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) Report [5], the proportion of women entrepreneurs has risen significantly over the past decade, particularly in the service sector and socially oriented industries. Internationally, women’s entrepreneurial activity continues to grow, especially across Asia. According to the Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs (MIWE) [6]. However, LTC entrepreneurship differs from other industries in that its challenges not only stem from financial and operational risks but also involve emotional labor and social responsibility [7]. Therefore, female LTC entrepreneurs need additional psychological resources and social support to sustain their businesses and maintain well-being. Despite these developments, limited research has examined how female entrepreneurs navigate the challenges of the LTC industry, highlighting the need for focused scholarly attention.

1.2 Women’s Entrepreneurship and the LTC Context

Women’s entrepreneurship has become a global trend. Brush and Cooper [8] argue that women’s entrepreneurship emphasizes not only economic benefits but also social value and community engagement. Henry et al. [9] suggest that women’s entrepreneurship should be understood within the context of gender roles and culture, as challenges often arise from resource constraints and social stereotypes. Recent research shows that women entrepreneurs are more likely to enter socially oriented and care-related industries [10], with LTC being one such field.

In Taiwan, LTC entrepreneurs often come from professional backgrounds such as nursing, social work, and caregiving. They transform their expertise into entrepreneurial energy by establishing day care centers, home care service agencies, and community-based care stations [4]. These entrepreneurial models combine commercial and social functions, not only addressing the needs of an aging population but also promoting healthy aging and community inclusion. Research also highlights that women entrepreneurs often pursue both social missions and innovative models, thereby advancing the diversified development of the health care industry [11,12].

Importantly, many women in LTC entrepreneurship are motivated by necessity-driven conditions such as family caregiving responsibilities or limited employment opportunities, rather than being purely opportunity-driven. This necessity orientation amplifies their exposure to financial, emotional, and social risks, increasing the need for additional support. Consequently, their psychological resilience and social capital become crucial resources that enable them to overcome constraints, sustain entrepreneurship, and maintain well-being [13,14].

1.3 Psychological Resilience and Well-Being

Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s ability to adapt and recover when facing stress or adversity [15]. In the field of entrepreneurship, resilience is regarded as core psychological capital, helping entrepreneurs maintain motivation, focus, and persistence in highly uncertain environments [16]. Recent studies further point out that resilience is closely related to entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being, playing a significant role in alleviating stress and preventing burnout [17].

With the emergence of the post-pandemic era and economic instability, new empirical evidence has continued to accumulate. Nguyen et al. [18] propose that resilience and optimism are critical factors explaining entrepreneurial well-being and call for the establishment of more comprehensive frameworks. Dzomonda [19] finds that resilience moderates the relationship between stress-coping strategies and subjective well-being, showing its buffering effect. Woo et al. [20], through a cross-national analysis, indicate that research on entrepreneurial well-being has been growing over the past five decades, with resilience identified as a key factor affecting life satisfaction. Malak et al. [21] also verifies that the four dimensions of psychological capital—hope, optimism, confidence, and resilience—have positive effects on micro-entrepreneurs’ success and well-being.

In the context of women’s entrepreneurship, resilience is especially important. Female LTC entrepreneurs often need to balance business operations and family caregiving responsibilities, which easily lead to role conflicts and psychological stress [13]. Studies show that women entrepreneurs with higher resilience not only sustain entrepreneurship more effectively but also report significantly higher life satisfaction and well-being [22,23]. Chatterjee et al. [24] further point out that for grassroots women entrepreneurs, resilience enables them to maintain a positive attitude even under resource-constrained conditions, gaining psychological empowerment and well-being from entrepreneurship. Accordingly, this study conceptualizes resilience as a core psychological resource in shaping well-being among female LTC entrepreneurs.

1.4 Social Capital and Well-Being

Social capital refers to the resources individuals acquire through social networks, including trust, reciprocity, and cooperation [25]. In entrepreneurship research, social capital provides financial, informational, and emotional support, exerting significant influence on both entrepreneurial performance and well-being [26]. Crowley and Barlow [27] argue that social capital enhances entrepreneurs’ well-being and social integration. Jalil et al. [28] also find that psychological and social capital jointly promote women entrepreneurs’ business expansion intentions.

In the context of female LTC entrepreneurship, social capital is even more critical. Studies show that women entrepreneurs can effectively reduce feelings of isolation and improve well-being by building professional networks and community trust [14]. Newman et al. [29] further highlight that entrepreneurs benefit not only from accessing business resources through networks but also from improved subjective well-being. Thus, social capital is not only a business resource but also a protective factor for well-being, warranting closer examination in the LTC entrepreneurial context.

1.5 The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Competence

Although entrepreneurial competence and social capital directly influence well-being, their effects may also be indirectly realized through psychological resilience. Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s capacity to adapt, recover, and sustain functioning under stress or adversity [15]. In the context of entrepreneurship, resilience enables female entrepreneurs to convert both personal skills such as opportunity recognition, planning, and risk management [30] and external resources such as social capital into enhanced well-being and sustainable business outcomes [23].

Prior research also indicates that while entrepreneurial competence contributes to performance and success [31,32], and is often constrained by gender roles and caregiving responsibilities [10], it is resilience that ultimately determines whether these resources can be transformed into psychological well-being. In this sense, entrepreneurial competence and social capital may strengthen resilience, which in turn improves mental health and life satisfaction among female LTC entrepreneurs.

Accordingly, this study conceptualizes psychological resilience as the key mediating mechanism that channels both individual-level resources (entrepreneurial competence) and external resources (social capital) into the well-being of female entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial motivation, though not the central focus of this study, is included as an exploratory variable to further compare its relative influence on well-being.

1.6 Research Gaps and Objectives

In summary, prior research has demonstrated that resilience, social capital, and entrepreneurial competence are associated with well-being. However, two major gaps remain. First, most studies have focused on general entrepreneurship or SMEs, while empirical evidence on female entrepreneurs in the LTC industry is scarce. Given Taiwan’s transition to a super-aged society, it is crucial to examine this unique population. Second, although the resilience–well-being relationship has been widely acknowledged, few studies have established an integrated framework that explicitly incorporates resilience as a mediating mechanism linking both entrepreneurial competence and social capital to entrepreneurial well-being.

Accordingly, this study has the following objectives:

- 1.To examine the effects of psychological resilience, entrepreneurial competence, and social capital on the well-being of female LTC entrepreneurs.

- 2.To test whether psychological resilience mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial competence, social capital, and well-being.

- 3.To complement quantitative analysis with qualitative interviews, providing in-depth insights into how female LTC entrepreneurs demonstrate resilience and utilize social capital in their entrepreneurial journeys.

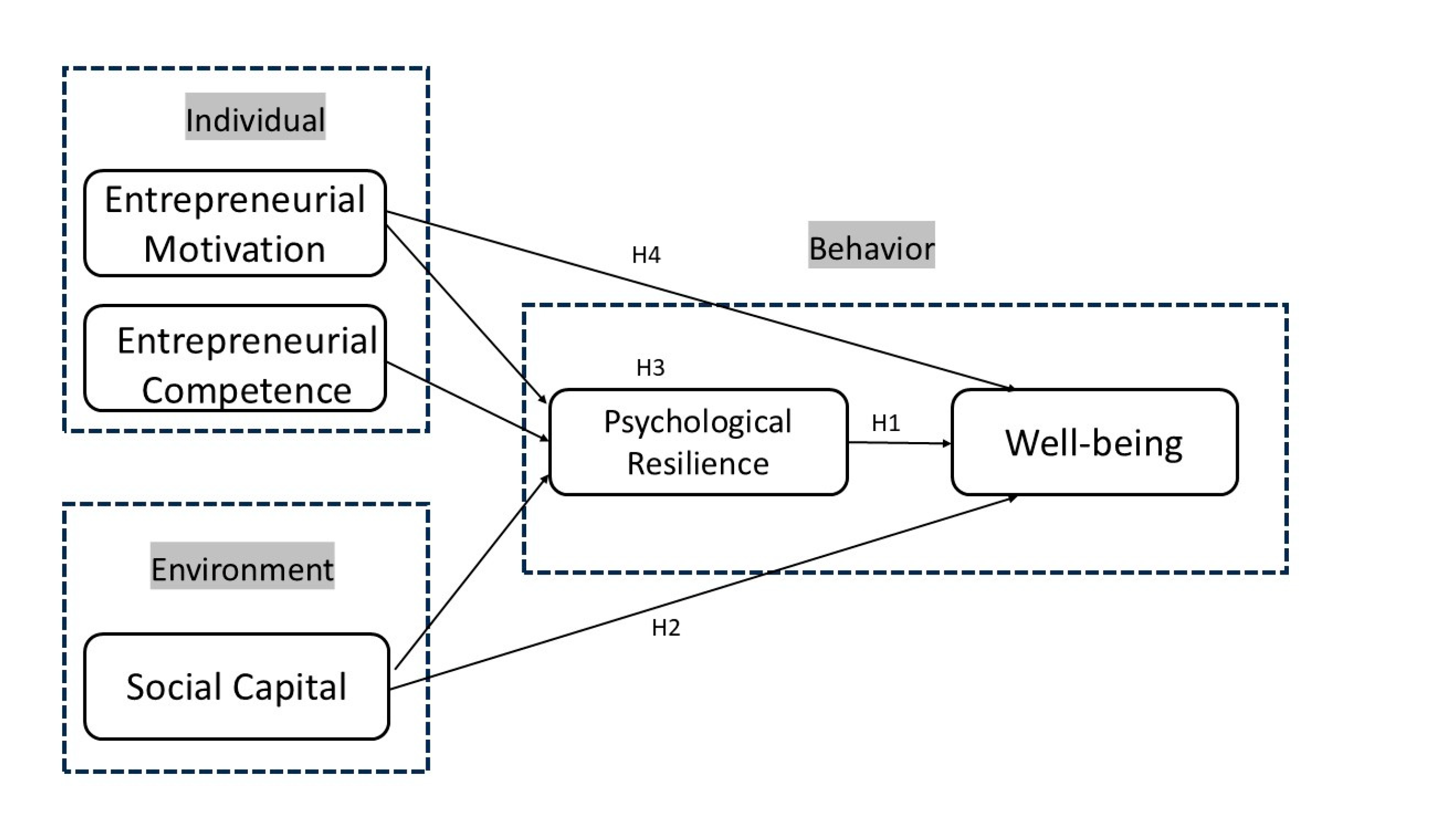

Based on these objectives, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Psychological resilience is positively associated with well-being.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Social capital is positively associated with well-being.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Psychological resilience mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial competence, social capital, and well-being.

Hypothesis 4 (H4) (exploratory): Entrepreneurial motivation is positively associated with well-being.

This study therefore contributes to the literature by addressing both a population gap (female LTC entrepreneurs) and a theoretical gap (resilience as a mediating mechanism), offering empirical evidence and policy-relevant insights to empower female entrepreneurs, strengthen their mental health, and promote sustainable development of the LTC sector.

This study aimed to examine the effects of psychological resilience and social capital on the well-being of female entrepreneurs in the LTC industry, and to test the mediating role of entrepreneurial competence. A mixed-method design was employed, combining the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The quantitative component utilized a structured questionnaire survey to verify the relationships among the variables, while the qualitative component involved in-depth interviews to explore the psychological processes and resource utilization within entrepreneurial experiences. To enhance validity and reliability, methodological triangulation was applied across methods, data sources, and researchers [33].

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the research framework specifies psychological resilience and social capital as independent variables, well-being as the dependent variable, and entrepreneurial competence as the mediating variable. This framework highlights how psychological and environmental resources, when expressed through entrepreneurial competence, influence the well-being of female LTC entrepreneurs.

A purposive sampling strategy was adopted. A total of 76 questionnaires were distributed to female LTC entrepreneurs in Taiwan. Three questionnaires with more than 30% missing responses were excluded as invalid, resulting in 73 valid cases for quantitative analysis. For the qualitative component, eight entrepreneurs were recruited for semi-structured interviews, providing rich narrative data that complemented and validated the quantitative findings.

Figure 1: Research framework.

The study participants were female entrepreneurs in the LTC sector in Taiwan, whose business operations included home care services, day care centers, community-based integrated care stations, nursing institutions, and other innovative LTC service units.

- 1.Quantitative research: Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, using channels such as the Ministry of Economic Affairs Women Entrepreneurship Flying Geese Program, the LTC Alliance Platform, the Taiwan Home Nursing and Care Services Association, and lists of LTC-related agencies provided by local governments. A total of 76 questionnaires were distributed. Responses with more than 30% missing data were excluded as invalid (n = 3), resulting in 73 valid questionnaires, which formed the basis for statistical analyses.

- 2.Qualitative research: Participants were recruited through snowball sampling, with 8 female LTC entrepreneurs selected from diverse entrepreneurial backgrounds. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted to complement the survey data and to explore how resilience and social capital were manifested in their entrepreneurial journeys.

The study was conducted in two stages:

- 1.Quantitative stage: An online and paper-based survey was administered between May and June 2025. Ethical approval for the study was secured from the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 202301922B0). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Invalid responses were excluded, and valid data were archived for analysis.

- 2.Qualitative stage: In-depth interviews were conducted between June and July 2025. Each interview lasted approximately 60–90 min. With participants’ informed consent, all interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded for thematic analysis. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and they were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without consequence.

Data was collected using both in-depth interviews and structured questionnaires. The questionnaire was developed based on the research framework and relevant literature, and consisted of six sections:

- 1.Demographics: Age, education, marital status, type of business, location, etc.

- 2.Entrepreneurial Motivation Scale (EMS): Adapted from Benjamin and Philip [34] and Horng et al. [35], covering intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, with 10 items (Cronbach’s α = 0.70–0.83).

- 3.Psychological Resilience Scale (PRS): Based on the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; [15]) and a localized version, with 25 items across five dimensions (equanimity, perseverance, confidence, meaningfulness, self-satisfaction), Cronbach’s α = 0.79–0.92.

- 4.Social Capital Scale (SCS): Adapted from Jalil et al. [36] and Dai et al. [37], comprising internal and external social capital dimensions, with 10 items (Cronbach’s α = 0.84–0.92).

- 5.Entrepreneurial Competence Scale (ECS): Based on Mawson et al. [38] and Hsieh et al. [39], covering five dimensions (opportunity, commitment, concept, resources, operation), with 16 items (overall Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

- 6.Well-Being Scale (WHO-5): Using the WHO-5 Well-Being Index [40], consisting of 5 items rated on a 6-point scale to assess positive emotions and life satisfaction over the past two weeks (Cronbach’s α = 0.82–0.90).

All instruments were reviewed by experts to ensure content validity. Item analysis, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted to test construct validity, demonstrating that the research tools possessed strong reliability and validity.

This study employed a mixed-method approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative analyses to ensure the comprehensiveness and depth of the findings.

For the quantitative analysis, descriptive statistics were first conducted to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics and to calculate the means and standard deviations of the main variables. Reliability and validity tests were then performed to examine the internal consistency and construct validity of the measurement instruments. Next, correlation analyses were conducted to explore linear relationships among the variables. Multiple regression analyses were used to test the research hypotheses, specifically examining the direct and indirect effects of entrepreneurial motivation, psychological resilience, and social capital on entrepreneurial competence and well-being.

Mediation analysis was further performed to test whether entrepreneurial competence mediated the relationships between resilience, social capital, and well-being. The mediation analysis used SPSS 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and PROCESS Macro v4.0. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with p < 0.10 considered marginally significant.

For the qualitative analysis, semi-structured in-depth interviews were transcribed verbatim and subjected to systematic coding and thematic analysis. Open coding, axial coding, and selective coding were employed to inductively identify core themes that aligned with the research framework. Special attention was given to how participants described their entrepreneurial motivations, demonstrated resilience in the face of challenges, and mobilized social capital for support, as well as how these experiences shaped their entrepreneurial competence and overall well-being.

Finally, triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings was conducted to enhance the credibility and validity of the results and to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced interpretation of the empirical evidence.

3.1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants

As shown in Table 1, all participants were female (100.0%). Most were married (75.3%) and held a college degree or below (72.6%). The majority operated home care service agencies (42.5%) and more than half managed their businesses as sole proprietorships (54.8%). In terms of professional background, nursing-related fields were most common (34.2%), followed by social work, multi-disciplinary, and other fields.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 73).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 73 (100.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 55 (75.3) |

| Unmarried | 9 (12.3) |

| Divorced | 8 (11.0) |

| Widowed | 1 (1.4) |

| Education level | |

| College or below | 53 (72.6) |

| Graduate or above | 20 (27.4) |

| Type of organization | |

| Home care service agency | 31 (42.5) |

| Day care center | 9 (12.3) |

| Multiple-service types | 13 (17.8) |

| Other types | 20 (27.4) |

| Ownership type | |

| Sole proprietorship | 40 (54.8) |

| Partnership | 31 (42.5) |

| Other forms | 2 (2.7) |

| Professional background | |

| Nursing-related | 25 (34.3) |

| Social work | 10 (13.6) |

| Multi-disciplinary | 13 (17.8) |

| Other | 25 (34.3) |

3.2 Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables

Descriptive statistics for the five main study variables are presented in Table 2. Among the 73 participants, entrepreneurial motivation showed a mean of 3.31 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.66), reflecting a moderate level of motivation toward entrepreneurship in the long-term care sector. By contrast, entrepreneurial competence (Mean = 4.03, SD = 0.54), social capital (Mean = 4.14, SD = 0.55), and psychological resilience (Mean = 4.17, SD = 0.44) were all relatively high, suggesting that respondents generally perceived themselves as capable, socially well connected, and resilient in facing challenges. Well-being also exhibited a high mean (Mean = 4.24, SD = 0.63), indicating that participants reported an overall positive sense of life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Taken together, these findings reveal that, except for entrepreneurial motivation, all other variables scored above the midpoint of the scale. This pattern suggests that while respondents’ motivational drive for entrepreneurship may be moderate, they nevertheless demonstrate strong competence, supportive social networks, and resilience, which in turn are reflected in higher levels of well-being.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of main variables (N = 73).

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Motivation | 3.31 | 0.66 | 1.40 | 5.00 |

| Entrepreneurial Competence | 4.03 | 0.54 | 2.94 | 5.00 |

| Social Capital | 4.14 | 0.55 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

| Psychological Resilience | 4.17 | 0.44 | 3.04 | 4.96 |

| Well-Being | 4.24 | 0.63 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

Pearson product-moment correlations among the five main study variables are reported in Table 3. Results indicated that entrepreneurial competence was significantly and positively correlated with psychological resilience (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), suggesting that respondents with higher competence tended to demonstrate stronger resilience and adaptability. Entrepreneurial competence was also positively associated with well-being (r = 0.44, p < 0.01), implying that higher competence contributes to greater satisfaction with life and work. In addition, social capital showed significant positive correlations with both psychological resilience (r = 0.41, p < 0.01) and well-being (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), indicating that participants with richer social support networks were more likely to exhibit stronger resilience and experience higher levels of well-being. Psychological resilience itself was also positively correlated with well-being (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), providing empirical support for its theoretical role as a mediator in the proposed model. By contrast, entrepreneurial motivation showed relatively low correlations with the other variables and did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that motivation alone may not be sufficient to directly influence resilience or well-being. Overall, these results provide preliminary support for the study hypotheses, underscoring the importance of entrepreneurial competence, social capital, and psychological resilience in the enhancement of well-being, and laying the foundation for subsequent regression and mediation analyses.

Notably, entrepreneurial motivation showed relatively low and non-significant correlations with the other variables, suggesting that motivation alone may not be sufficient to directly influence resilience or well-being. This non-significant result further supports the treatment of entrepreneurial motivation as an exploratory rather than a core predictor in the present framework. Consistent with the analytical strategy, significance was evaluated at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with p < 0.10 considered marginally significant.

Table 3: Correlation matrix of main variables (N = 73).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Entrepreneurial Motivation | - | ||||

| 2. Entrepreneurial Competence | 0.18 | - | |||

| 3. Social Capital | 0.12 | 0.36** | - | ||

| 4. Psychological Resilience | 0.09 | 0.52*** | 0.41** | - | |

| 5. Well-Being | 0.07 | 0.44** | 0.39** | 0.47*** | - |

3.4 Regression Analysis Predicting Psychological Resilience and Well-being

To examine the direct effects of the independent variables on well-being, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. In Step 1, demographic control variables (age and education) were entered; in Step 2, psychological resilience and social capital were added; and in Step 3, entrepreneurial competence and entrepreneurial motivation were included. The results are presented in Table 4.

Psychological resilience was a strong positive predictor of well-being (B = 0.417, β = 0.42, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Social capital also significantly predicted well-being (B = 0.214, β = 0.19, p < 0.05), providing support for H2. Entrepreneurial competence contributed positively to well-being (B = 0.292, β = 0.65, p < 0.01), indicating that competence enhances life satisfaction and psychological health, consistent with H3. By contrast, entrepreneurial motivation did not significantly predict well-being (B = −0.067, β = 0.07, no significance), confirming its exploratory rather than central role in the framework (H4 not supported).

The final model accounted for 69% of the variance in well-being (R2 = 0.69, Adj. R2 = 0.68, F(4, 65) = 36.75, p < 0.001), indicating a strong overall fit. Statistical significance was evaluated at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with p < 0.10 considered marginally significant.

Table 4: Multiple regression analysis results (N = 73).

| Predictor | Psychological Resilience (PR) | Well-Being (WB) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | |

| Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM) | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.07 | −0.067 |

| Entrepreneurial Competence (EC) | 0.532*** | 0.078 | 0.65*** | 0.292* |

| Social Capital (SC) | 0.150* | 0.078 | 0.19* | 0.214* |

| Psychological Resilience (PR) | - | - | 0.42*** | 0.417*** |

| R2 | 0.60 | 0.69 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.58 | 0.68 | ||

| F | 33.23*** | 36.75*** | ||

| df | (3, 66) | (4, 65) | ||

3.5 Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience in the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Competence, Social Capital, and Well-Being

Table 5 presents the results of hierarchical regression analyses conducted to examine the mediating role of psychological resilience in the relationship between entrepreneurial competence, social capital, and well-being.

In Model 1, entrepreneurial competence (β = 0.65, p < 0.001) and social capital (β = 0.19, p < 0.10) were regressed on psychological resilience. The model was significant, R2 = 0.60, F(2, 70) = 33.23, p < 0.001, indicating that entrepreneurial competence was a strong predictor of resilience, whereas social capital showed a marginally significant effect.

In Model 2, entrepreneurial competence (β = 0.44, p < 0.01) and social capital (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) were directly regressed on well-being, yielding a significant model (R2 = 0.52, F(2, 67) = 34.10, p < 0.001). This suggests that both predictors contributed positively to well-being when considered independently of psychological resilience.

In Model 3, psychological resilience was added as a mediator. Results showed that psychological resilience had a strong positive effect on well-being (β = 0.41, p < 0.001). In this model, the coefficients of entrepreneurial competence (β = 0.29, p < 0.05) and social capital (β = 0.21, p < 0.05) decreased in magnitude compared to Model 2, but remained significant, indicating partial mediation. The overall explanatory power of the model increased substantially to R2 = 0.69, F(4, 65) = 36.75, p < 0.001.

These findings provide empirical support for the mediating role of psychological resilience, suggesting that both entrepreneurial competence and social capital enhance well-being not only directly but also indirectly through resilience. Thus, H3 was supported, confirming psychological resilience as a partial mediator in the resilience–well-being nexus.

Table 5: Regression analyses testing the mediating effect of psychological resilience (M) on the relationship between entrepreneurial competence/social capital (X) and Well-being (Y) (N = 73).

| Variable | Psychological Resilience (Model 1) | Well-Being (Model 2) | Well-Being (Model 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Competence (X) | 0.65*** | 0.44** | 0.29* |

| Social Capital (X) | 0.19† | 0.39** | 0.21* |

| Psychological Resilience (M) | - | - | 0.41*** |

| R2 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.69 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.68 |

| F | 33.23*** | 34.10*** | 36.75*** |

| df | (2, 70) | (2, 67) | (4, 65) |

3.6 Qualitative Analysis Results

Through thematic analysis of in-depth interviews with eight female entrepreneurs in the long-term care (LTC) industry, four core themes were identified: entrepreneurial motivation, psychological resilience, social capital, and entrepreneurial competence. These themes highlight the multifaceted challenges and coping strategies encountered by female LTC entrepreneurs and complement the statistical associations identified in the quantitative analyses (Table 6).

Table 6: Themes and representative quotes from qualitative interviews.

| Theme | Subtheme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Motivation | Economic pressure | “I just wanted to be my own boss and earn money.” (A-01-01) |

| Social mission | “I saw the demand in rural areas, so I wanted to give back to my hometown.” (E-02-03) | |

| Professional transition | “My background in finance gave me an advantage in financial planning.” (B-01-02) | |

| Psychological Resilience | Regulatory challenges | “We had to comply with both LTC and disability regulations, which was very stressful.” (G-04-02) |

| Financial difficulties | “During the pandemic, our income decreased sharply, so I had to rely on my family’s support.” (E-04-03) | |

| Self-adjustment | “Exercise and reading helped me regain strength.” (F-05-01) | |

| Learning from failure | “Every failure pushes me to find a new method.” (A-07-01) | |

| Social Capital | Local networks | “I approached community leaders and local clinics for collaboration.” (E-08-01) |

| Association support | “The association helped us a lot with financial adjustments and administrative procedures.” (D-08-02) | |

| Family support | “At first they supported me, but later they didn’t understand why I was always so busy.” (A-09-01) | |

| Institutional gaps | “There were no government resources at all when we first started.” (A-10-01) | |

| Entrepreneurial Competence | Professional advantage | “I can adapt very quickly.” (A-12-02) |

| Managerial weakness | “I really need to improve my financial management.” (A-13-01); “Managing people is very difficult.” (H-06-01) |

Theme 1: Entrepreneurial Motivation

Entrepreneurial motivation reflected both economic necessity and social mission. Some participants described entering entrepreneurship primarily to ensure financial survival or gain autonomy (A-01-01), consistent with “necessity-driven entrepreneurship” [41]. Others emphasized mission-driven goals, such as addressing unmet needs in underserved areas (E-02-03), aligning with “opportunity-driven entrepreneurship”. Several participants highlighted cross-professional transitions (e.g., from finance to LTC), which introduced both advantages and regulatory challenges (B-01-02). This duality explains the quantitative finding that entrepreneurial motivation alone was not a significant predictor of well-being; unless internalized as a long-term mission, motivation may not translate into enhanced well-being [42].

Theme 2: Psychological Resilience

Psychological resilience emerged as a central resource for sustaining entrepreneurship. Participants frequently described pressures from complex regulations, limited funding, and workforce shortages (G-04-02; E-04-03). Yet they adopted adaptive strategies such as exercise, self-reflection, or short breaks to recover energy (F-05-01). Importantly, many viewed failures as learning opportunities: “Every failure pushes me to find a new method” (A-07-01). This finding echoes Ayala and Manzano [1], who argued that resilience enables entrepreneurs to persist under uncertainty, and Hartmann et al. [16], who emphasized resilience as a mechanism for transforming stress into growth.

Theme 3: Social Capital

Social capital was shown to be critical in both sustaining entrepreneurship and enhancing well-being. Participants relied heavily on local networks and professional associations for resource access and referrals (E-08-01; D-08-02). Family support was valuable at the initial stage but tended to diminish as entrepreneurial pressures increased (A-09-01). By contrast, institutional support from government and NGOs was generally perceived as inadequate (A-10-01). These patterns align with Davidsson and Honig [26] and Putnam [25], highlighting the role of bridging social capital in facilitating resource mobilization and psychological support when formal systems fall short.

Theme 4: Entrepreneurial Competence

Entrepreneurial competence demonstrated a clear pattern of professional strength but managerial weakness. Many participants expressed confidence in service provision and adaptability (A-12-02), but reported difficulties in financial and personnel management (A-13-01; H-06-01). This resonates with Mitchelmore and Rowley’s [43] framework, which emphasizes that entrepreneurial competence must encompass not only technical expertise but also managerial and financial skills. The findings also support the quantitative result that entrepreneurial competence partially mediated the effects of resilience and social capital on well-being.

Overall, the qualitative analysis deepened the quantitative results by showing that well-being is not achieved solely through entrepreneurial motivation. Instead, it requires the combined effects of psychological resilience and social capital, which are then transformed into tangible outcomes through entrepreneurial competence. In other words, the well-being of female LTC entrepreneurs is shaped by the interaction of motivation, resources, and competence. These findings validate the proposed conceptual framework and align with international research on female entrepreneurship and well-being [8], offering integrated evidence from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives.

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to examine the relationships among psychological resilience, social capital, entrepreneurial competence, and well-being among female entrepreneurs in the long-term care sector, and to test the mediating role of entrepreneurial competence. By integrating quantitative and qualitative findings, several key results and interpretations emerged.

4.1 The Central Role of Psychological Resilience in Fostering Well-Being

Quantitative analyses revealed a significant positive correlation between psychological resilience and well-being (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), and regression results confirmed that resilience is an important predictor of well-being. The qualitative data further supported this result, with participants repeatedly emphasizing “adjusting one’s mindset under pressure” and “finding new methods after failure”, indicating that resilience helps maintain emotional stability and, in turn, enhances well-being. This finding is consistent with recent studies identifying resilience as a core psychological resource that enables entrepreneurs to sustain mental health and satisfaction in uncertain contexts [44,45]. Thus, the present study verifies the critical role of resilience in the context of female entrepreneurship in long-term care and provides empirical support for its importance.

4.2 Multiple Sources of Well-Being and the Mediating Role of Resilience

The mediation analyses demonstrated that psychological resilience plays a significant mediating role between both entrepreneurial competence and well-being, and between social capital and well-being. This suggests that well-being does not stem solely from skills or interpersonal support, but rather emerges through the transformation and internalization of such resources via resilience. The qualitative findings further showed that participants, when describing their sense of well-being, often highlighted experiences such as “maintaining emotional stability” and “recovering from stress”. These results align with Jalil et al. [28], who reported that psychological and social capital can be transformed into greater well-being and future entrepreneurial intentions through attitudes and adaptive processes.

4.3 The Supportive Functions of Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Competence

Although the primary focus of this study was on resilience and well-being, both social capital and entrepreneurial competence also played supportive roles. Correlation analyses revealed a significant association between social capital and well-being (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), while the qualitative results highlighted the role of “peer support” and “local networks” in fostering psychological stability. However, the mediation results indicated that the effects of these external resources on well-being were largely channeled through resilience. Similarly, entrepreneurial competence showed limited direct effects on well-being in regression models, but demonstrated significant indirect effects via resilience. These findings are consistent with recent perspectives that view entrepreneurial competence as a bridge for transforming resources into outcomes [45].

This study proposes and validates an integrated framework centered on the “resilience-well-being” nexus. Unlike prior research that predominantly focused on entrepreneurial motivation or single social resources, this study emphasizes the central role of resilience in shaping well-being and reveals that well-being is the outcome of multiple interacting factors. This result echoes the literature review by Zhang and Chen [46], which noted that research on entrepreneurial well-being is shifting from single-factor models toward multi-dimensional and interactive frameworks. The present findings enrich this trend, particularly within the high-pressure context of female entrepreneurs in long-term care.

4.5 Practical and Policy Implications

The findings suggest that interventions aimed at improving the well-being of female long-term care entrepreneurs should prioritize resilience development. First, resilience-enhancing programs-such as stress management, cognitive reframing, and recovery planning-should be incorporated into entrepreneurship training and counseling. Second, professional associations and peer support networks should be further promoted to strengthen social capital, thereby indirectly improving well-being. Finally, targeted training in management and financial skills should be provided to address weaknesses in entrepreneurial competence, enabling entrepreneurs to better translate psychological and social resources into enhanced well-being and business outcomes.

4.6 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The study is limited by its focus on female long-term care entrepreneurs in Taiwan, restricting the generalizability of its findings. In addition, the qualitative data relied on self-reports, which may be subject to recall bias. Moreover, the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inference. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to trace the dynamic interplay between resilience and well-being over time, and conduct comparative analyses across gender, industries, and cultural contexts to test the broader applicability of the “resilience-well-being” framework.

This study, using both quantitative and qualitative approaches, demonstrated that psychological resilience plays a central role in fostering well-being among female entrepreneurs in the long-term care sector. The results revealed that resilience not only directly enhances well-being but also mediates the effects of social capital and entrepreneurial competence on well-being. This indicates that well-being is not simply the product of external resources or skills, but rather emerges through the transformation of these resources into internal psychological strengths.

The study makes three primary theoretical contributions. First, it introduces an integrative framework that places psychological resilience at the core of well-being, highlighting its mediating function in converting social capital and competence into psychological outcomes. Second, it responds to recent scholarly calls for greater attention to the mechanisms underlying well-being in entrepreneurship, addressing a gap in prior research that often overlooked psychological processes in favor of structural or motivational factors. Third, by adopting a mixed-methods design, the study not only validates the statistical relationships among variables but also uncovers how resilience is enacted in practice through the lived experiences of female entrepreneurs in long-term care.

The findings carry several practical and policy implications. (1) Resilience training: Entrepreneurship education and support programs should incorporate resilience-building strategies, including stress management, cognitive reframing, and recovery planning. (2) Strengthening social support networks: Government agencies and professional associations should develop local and cross-sector platforms to facilitate access to both informational and emotional resources. (3) Capacity building in management and finance: Addressing gaps in financial literacy and human resource management can enable entrepreneurs to more effectively transform resilience and social capital into sustainable well-being and business outcomes.

This study has certain limitations. The sample size was relatively small and limited to female entrepreneurs in Taiwan’s long-term care industry, which may restrict generalizability. The qualitative data were based on self-reports, which could be influenced by recall or social desirability bias. Moreover, the cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal inferences.

5.5 Future Research Directions

Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to examine how resilience and well-being evolve over time in entrepreneurial contexts. Comparative studies across gender, industries, and cultural settings would help test the robustness of the resilience-well-being model. Additionally, intervention-based research-such as evaluating the effects of resilience training or social capital-building programs-could provide more direct evidence of how targeted strategies improve the well-being of entrepreneurs.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author, [Chia-Hui Hou], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 202301922B0).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ayala JC , Manzano G . The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. J Econ Psychol. 2014; 42: 126– 35. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2014.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang M , Wang J , Su X . The impact of social support on entrepreneurial well-being: the role of entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial efficacy. Sage Open. 2024; 14( 4): 21582440241297232. doi:10.1177/21582440241297232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ministry of Health and Welfare . Long-term care 2.0 policy white paper. Taipei, Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2022. [Google Scholar]

4. Huang Y , Knight C . Social innovation in long-term care: entrepreneurship and community-based services in East Asia. J Aging Soc Policy. 2022; 34( 5): 543– 60. doi:10.1080/08959420.2022.2036178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) . Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023/2024 Global Report [Internet]. London, UK: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.gemconsortium.org/reports/latest-global-report. [Google Scholar]

6. Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs (MIWE) 2019 [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Mastercard; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.mastercard.com/news/media/yxfpewni/mastercard-index-of-women-entrepreneurs-2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Song J , Liu F , Li X , Qu Z , Zhang R , Yao J . The effect of emotional labor on presenteeism of Chinese nurses in tertiary-level hospitals: the mediating role of job burnout. Front Public Health. 2021; 9: 733458. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.733458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Brush CG , Cooper SY . Female entrepreneurship and economic development: an international perspective. Entrep Reg Dev. 2012; 24( 1–2): 1– 6. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.637340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Henry C , Foss L , Ahl H . Gender and entrepreneurship research: a review of methodological approaches. Int Small Bus J Res Entrep. 2016; 34( 3): 217– 41. doi:10.1177/0266242614549779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Saleem I , Arafat MY , Saleem A . Women entrepreneurs and changing social structure of KSA. Vikalpa J Decis Mak. 2025; 50( 1): 51– 68. doi:10.1177/02560909241304635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Austin J , Stevenson H , Wei-Skillern J . Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different, or both? Entrep Theory Pract. 2006; 30( 1): 1– 22. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Purushothama BN . Social entrepreneurship in health care: opportunities and challenges. Int J Manag Commer Innov. 2019; 7( 2): 1206– 1210. [Google Scholar]

13. Gupta VK , Turban DB , Wasti SA , Sikdar A . The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrep Theory Pract. 2009; 33( 2): 397– 417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00296.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pergelova A , Zwiegelaar J , Smale B . The eudaimonic well-being of entrepreneurs: a gendered perspective. J Small Bus Manag. 2025: 1– 37. doi:10.1080/00472778.2025.2490563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Connor KM , Davidson JRT . Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18( 2): 76– 82. doi:10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hartmann U , Breugst N , Patzelt H . Entrepreneurial resilience in times of crisis: the role of self-leadership. J Bus Ventur. 2022; 37( 2): 106123. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Conduah AK , Essiaw MN . Resilience and entrepreneurship: a systematic review. F1000Research. 2022; 11: 348. doi:10.12688/f1000research.75473.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nguyen HT , Le QV , Pham TT . Resilience, optimism, and entrepreneurial well-being: evidence from emerging economies. J Bus Ventur Insights. 2025; 18: e00325. [Google Scholar]

19. Dzomonda O , Neneh B , Jaiyeoba O . Coping strategies and subjective well-being among women entrepreneurs: the mediating role of psychological resilience. Dev South Afr. 2025; 42( 3): 442– 62. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2025.2474749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Woo GH , Kim H , Park J . The role of psychological capital in the relationship between authentic leadership and job performance: a study on the mediating effects of trust and resilience. Front Psychol. 2018; 9: 1696. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01696 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Malak SA , Raza A , Jariko MA . Entrepreneurs’ psychological capital as a mediator: a broaden-and-build perspective on burnout and psychological well-being. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13: 1179. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-03402-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rauch A , Frese M . Born to be an entrepreneur? Revisiting the personality approach to entrepreneurship. In: Baum JR , Frese M , Baron R , editors. The psychology of entrepreneurship. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. p. 41– 65. [Google Scholar]

23. Newman A , Obschonka M , Schwarz S , Cohen M , Nielsen I . Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: a systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J Vocat Behav. 2019; 110: 403– 19. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chatterjee S , Ghosh S , Bhattacharya A . Resilience and psychological empowerment of grassroots women entrepreneurs. J Enterprising Communities. 2022; 16( 5): 743– 63. doi:10.1108/JEC-01-2021-0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Putnam RD . Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster; 2000. doi:10.1145/358916.361990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Davidsson P , Honig B . The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J Bus Ventur. 2003; 18( 3): 301– 31. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Crowley M , Barlow J . Social capital and well-being among entrepreneurs: a systematic review. Small Bus Econ. 2022; 59( 3): 635– 58. doi:10.1007/s11187-021-00567-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jalil MF , Hassan T , Karim S . Psychological capital, social capital, and women entrepreneurs’ growth intentions. Int J Entrep Behav Res. 2023; 29( 2): 289– 309. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-02-2022-0215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Newman A , Sieger P , Zhao F . Social capital, network ties, and entrepreneurial well-being. Small Bus Econ. 2018; 51( 2): 425– 47. doi:10.1007/s11187-017-9925-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Man TWY , Lau T , Chan KF . The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: a conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. J Bus Ventur. 2002; 17( 2): 123– 42. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00058-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li J , Wu X , Wang Y . Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial competence, and firm performance: evidence from China. Asia Pac J Manag. 2021; 38( 3): 833– 57. doi:10.1007/s10490-019-09678-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hossain M , Dwivedi YK , Rana NP . Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: the mediating role of entrepreneurial competence. J Bus Res. 2020; 112: 178– 90. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Creswell JW , Plano Clark VL . Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Benjamin A , Philip N . Measuring entrepreneurial motivation: a psychometric approach. J Bus Ventur. 1986; 1( 2): 123– 136. [Google Scholar]

35. Chou SF , Horng JS , Liu CH , Huang YC , Zhang SN . The critical criteria for innovation entrepreneurship of restaurants: considering the interrelationship effect of human capital and competitive strategy a case study in Taiwan. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2020; 42: 222– 34. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jalil MF , Ali A , Kamarulzaman R . The influence of psychological capital and social capital on women entrepreneurs’ intentions: the mediating role of attitude. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2023; 10( 1): 393. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01908-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Dai W , Mao Z , Zhao X , Mattila AS . How does social capital influence the hospitality firm’s financial performance? The moderating role of entrepreneurial activities. Int J Hosp Manag. 2015; 51: 42– 55. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mawson S , Casulli L , Simmons EL . A competence development approach for entrepreneurial mindset in entrepreneurship education. Entrep Educ Pedagog. 2023; 6( 3): 481– 501. doi:10.1177/25151274221143146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hsieh CE . A study on entrepreneurial motivation, professional competence, entrepreneurial capital, entrepreneurial spirit, and entrepreneurial performance: evidence from Taiwan’s catering industry [ master’s thesis]. Taichung City, Taiwan: Asia University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. World Health Organization . Wellbeing measures in primary health care: the DepCare project. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

41. Hughes KD , Jennings JE , Brush C , Carter S , Welter F . Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrep Theory Pract. 2012; 36( 3): 429– 42. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00504.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Williams TA , Shepherd DA . Building resilience or providing sustenance: different paths of emergent ventures in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake. Acad Manag J. 2016; 59( 6): 2069– 102. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.0682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mitchelmore S , Rowley J . Entrepreneurial competencies: a literature review and development agenda. Int J Entrepreneurial Behav Res. 2010; 16( 2): 92– 111. doi:10.1108/13552551011026995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Simarasl N , Yaghoubi M , Karimi S . Resilience-building coping strategies and actionable tools for entrepreneurs. Bus Horiz. 2024; 67( 1): 89– 101. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2023.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Tisu L , Vîrgă D , Iliescu D . Entrepreneurial well-being and performance: a systematic review of antecedents and outcomes. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1123456. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rana T , Singh P . The influence of social capital on rural female entrepreneurs’ growth intention: the mediating role of human and psychological capital. J Dev Entrep. 2025; 30: 2550001. doi:10.1142/s1084946725500013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools