Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Freudian Group Psychology Perspective on the Psychological Mechanisms in South Korean Elite Sports Teams: Implications for Mental Health

1 Department of Sport & Leisure Studies, Division of Arts & Health Care, Myongji College, Seoul, 03656, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Mental Coaching & Creative Leadership, Graduate School, Sogang University, Seoul, 04107, Republic of Korea

3 Department of eSports, Division of Culture & Arts, Osan University, Osan-si, 18119, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Yeon-Hee Choi. Email: ; Young-Vin Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(4), 451-468. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.060896

Received 12 November 2024; Accepted 18 February 2025; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

Objectives: In this study, we examined the psychological impact of hierarchical and authoritarian structures in elite sports teams in South Korea on the ego formation and mental health of athletes. We aimed to analyze how these environments shape psychological well-being in athletes, drawing on Freud’s group psychology theory, while integrating perspectives from the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Social Identity Theory (SIT). Methods: We applied a qualitative case-study approach, with data collected through in-depth interviews with eight retired elite table tennis players from South Korea. These athletes shared their experiences with psychological mechanisms in their teams and how those mechanisms impacted their mental health throughout their careers. We analyzed the collected data using thematic analysis. Results: The investigated psychological mechanisms significantly influenced the ego development and psychological well-being in athletes. In hierarchical and authoritarian environments, identification and ego idealization suppressed the autonomy of the athletes. Hierarchical order and obedience to authority figures exert significant pressure on athletes to conform, impeding the development of an independent ego. Furthermore, group pressure exacerbates ego erosion and psychological stress, while corporal punishment reinforces psychological pressure and hinders ego integrity. The integration of the SDT highlights the need for autonomy-supportive environments to mitigate such risks, while the SIT emphasizes balancing individual identity with group cohesion to address identity conflicts and psychological tension. Conclusion: Hierarchical structures and authoritarian dynamics in South Korean elite sports teams critically suppress autonomy in athletes, leading to psychological distress and identity conflicts. This study highlights the urgent need for systemic interventions to reform coaching practices and foster autonomy-supportive environments. These results contribute to the global discourse on the mental health of athletes in elite sports and offer actionable strategies for improving long-term well-being. Finally, this study provides practical recommendations adaptable to diverse cultural and sporting contexts, enhancing athlete mental health worldwide.Keywords

South Korea’s elite sports have long been symbols of national pride and international achievement. This was particularly evident during the 2024 Summer Olympics, where South Korean athletes excelled in multiple sports and reaffirmed the nation’s global standing. However, these achievements have been overshadowed by systemic issues that cannot be resolved solely through athletic performance. Reports of human rights violations and widespread psychological problems within South Korea’s elite sports groups have raised significant concerns in the sports community [1–3]. These issues are not limited to individual cases but are deeply embedded in the elite sports system [3]. A key concern is the mental health of athletes, as the psychological pressures inherent in elite sports systems have been found to cause a myriad of mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, and burnout [4]. Addressing these challenges requires an in-depth examination of both the structural characteristics of elite sports and psychological mechanisms influencing athletes’ mental health.

The challenges within South Korea’s elite sports groups are deeply tied to their hierarchical and authoritarian structures, where coaches and senior athletes exert significant influence over younger athletes. Several studies on South Korean sports culture have documented how this structure impacts athletes’ mental well-being [3–5]. These groups are characterized by strict hierarchies that pressure athletes to achieve high performance [6–8]. From a young age, athletes undergo rigorous training and immense performance pressure, which is often exacerbated by the inherent hierarchical and authoritarian structures. As such, young athletes in South Korea’s elite sports systems face immense psychological pressures that influence their development and mental health [4,5]. The cultural emphasis on conformity and performance over individual well-being further compounded these challenges, which reinforces the authority of coaches and senior athletes [6]. This dynamic of internalizing group pressures has been shown to suppress athletes’ autonomy, contributing to long-term psychological distress, including anxiety and burnout [7,8].

Freud’s concept of group psychology provides a critical theoretical framework for understanding these issues. Freud explored how individuals identify with authority figures within a group and how this shapes their ego, behavior, and psychological structure. According to Freud, group dynamics can intensify identification with authority figures, suppressing autonomy and increasing conformity. This phenomenon is particularly relevant to hierarchical environments, such as South Korea’s elite sports teams [9,10], where hierarchical and authoritarian structures exacerbate psychological conflicts, as athletes navigate the tension between group conformity and personal identity. These mechanisms not only hinder personal development but also exacerbate mental health problems, such as depression and emotional instability. The persistence of hierarchical pressures and the normalization of conformity within these teams reflects Freud’s concept of “repression”, where individual desires are subordinated to group demands, leading to long-term psychological strain [9,10]. The psychological issues observed in these groups are not merely personal vulnerabilities or temporary phenomena; instead, they are reinforced and reproduced through psychological mechanisms within the group [11].

Existing research supports the idea that athletes in such environments experience distinct psychological challenges. The normalization of authoritarian coaching styles and hierarchical structures in South Korea’s elite sports teams significantly influences athletes’ psychological well-being [4,12]. For instance, Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic violence highlights how cultural and systemic pressures can perpetuate authority structures, impacting athletes’ autonomy and identity [12]. Additionally, repetitive exposure to high-pressure environments leads to emotional exhaustion and burnout, particularly among young athletes [3,4]. In South Korea, collectivist values and societal expectations reinforce hierarchical authority and conformity in elite sports teams, highlighting the need to explore how group pressure and hierarchical authority dynamics shape athletes’ psychological experiences.

Freud’s framework, developed in the early 20th century, provides foundational insights into group dynamics in hierarchical settings, making it highly relevant to South Korea’s elite sports teams. Nevertheless, Freud’s framework has limitations in addressing contemporary challenges, such as evolving coaching styles and the interplay of physical and psychological stressors. To address these gaps, modern theories such as Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Social Identity Theory (SIT) complement Freud’s psychoanalytic approach by offering empirically grounded perspectives on athlete well-being. SDT underscores the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in promoting psychological health and intrinsic motivation [13,14]. Autonomy-supportive environments are reported to enhance resilience and mitigate burnout in elite athletes. Meanwhile, SIT explores the balance between individual identity and group cohesion, highlighting the risks of over-conformity to group norms in undermining mental health [15,16].

This study aimed to examine how hierarchical and authoritarian structures in South Korea’s elite sports teams influence athletes’ psychological well-being and their ability to manage performance pressures, using Freud’s Group Psychology theory and complementing it with SDT and SIT. By integrating SDT and SIT, this study expands Freud’s framework to better address the psychological challenges faced by athletes in modern elite sports. This approach not only bridges theoretical insights but also provides actionable strategies for improving athlete mental health in hierarchical sports environments. Considering the abovementioned concerns, the key research questions guiding this study are:

Research Question 1: How does group pressure affect ego formation among athletes in South Korean elite sports teams?

Research Question 2: How do hierarchical authority dynamics influence the mental health of athletes in South Korean elite sports teams?

Through these research questions, this study seeks to bridge theoretical insights with practical interventions, providing a nuanced understanding of how hierarchical and authoritarian structures influence the psychological well-being of athletes. This approach will contribute to the development of support systems that prioritize mental health alongside athletic performance.

2.1 Freud’s Group Psychology and Athletes’ Mental Health

Freud’s theory of group psychology offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how hierarchical dynamics influence individual behaviors and psychological structures. At its core, Freud’s theory highlights identification and ego idealization, which explain how individuals internalize the values and expectations of authority figures. In high-pressure environments such as South Korean elite sports teams, these mechanisms are particularly pronounced. Athletes often face intense pressures to align their behaviors with authority figures, such as coaches and senior athletes, which may suppress autonomy and increase dependency [11,17].

Freud’s theory of leadership within group dynamics helps explain this process. In hierarchical settings, athletes internalize authority figures’ values and expectations, potentially causing psychological stress, anxiety, and long-term mental health challenges. Coaches often act as paternal authority figures, exerting a significant influence over athletes’ self-concept and ego development [13]. This dynamic reflects Freud’s concept of ego repression, wherein personal desires are subordinated to group demands. Such repression, while fostering group cohesion, exacerbates mental health issues, including anxiety, burnout, and identity confusion [17,18].

2.2 Integrating Freud with Modern Theories: SDT and SIT

SDT and SIT offer complementary perspectives that can bridge the gap between Freud’s framework and contemporary issues in elite sports. SDT emphasizes the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—as critical to mental well-being and intrinsic motivation [13,14]. In hierarchical sports environments, where conformity is prioritized over individuality, athletes often experience chronic autonomy suppression. This lack of autonomy has been linked to emotional exhaustion and burnout, aligning with Freud’s concept of ego repression while providing measurable constructs for empirical investigation [13,19]. Promoting autonomy and mental well-being in high-performance sports is crucial to enhancing athletes’ resilience and supporting their long-term psychological health [20].

SIT focuses on the interplay between individual identity and group membership, which is particularly relevant in collectivist cultures such as those in South Korea. Athletes who overly identify with group norms may suppress their individuality, leading to psychological tension and diminished mental health [15,16]. This aligns with observations that group psychology suppresses individual critical faculties, leading to autonomy loss and increased dependency on authority figures [21,22]. SIT-based interventions, such as team programs emphasizing individuality within a cohesive group framework, can mitigate these effects and foster psychological resilience [15].

2.3 Cultural Context and Modern Perspectives

South Korea’s elite sports environment exemplifies how collectivist cultures prioritize group harmony and hierarchical conformity, often sacrificing individual autonomy and psychological well-being [23]. This hierarchical structure, combined with intense group conformity, fosters significant psychological transformations in athletes and undermines their mental health and personal autonomy [11,18]. Freud’s concept of ego idealization explains how athletes, through intensified identification with authority figures (like coaches), lose their critical perspective and develop psychological structures that are overly dependent on external validation [9,11]. This resonates with the observation that group psychology can suppress the critical faculties of individual members, resulting in a loss of autonomy and increased dependency on authority figures [21,22]. Freud’s concept of group pressure aligns with the societal emphasis on conformity and hierarchy in South Korean sports teams. Integrating SDT and SIT offers strategies to address these systemic pressures. For example, SDT-based coaching strategies can enhance autonomy, while SIT-informed team programs balance personal identity with group cohesion. These approaches provide a nuanced understanding of how systemic pressures shape athletes’ psychological outcomes.

This integration also provides a robust lens to analyze mental health challenges in hierarchical sports. Freud’s theory highlights unconscious dynamics, while SDT and SIT introduce empirically validated constructs for practical interventions. By fostering autonomy and balancing identity within groups, this integrated framework offers strategies to enhance resilience and support athletes’ long-term mental health in high-performance sports.

This study investigates the psychological impact of authority and hierarchy in elite sports, integrating Freud’s theory of group dynamics with principles from SDT and SIT. Freud’s concepts of ego repression and group identification inform the exploration of hierarchical group dynamics, while SDT and SIT provide complementary perspectives on autonomy, competence, and group identity. Given the complex and multidimensional psychological mechanisms being studied (e.g., identification, ego idealization, and ego repression), the case study method was considered suitable for this study. This method is a well-established qualitative research approach and is particularly effective in gaining an in-depth understanding of specific social or psychological phenomena within particular groups or settings [24,25]. It allows researchers to conduct a detailed examination of individual cases and derive broader theoretical insights, thus contributing to the development of a more generalized theoretical framework [26].

This research adopted an interpretive paradigm, emphasizing the understanding of human experiences from the participants’ perspectives. Ontologically, it assumes that social reality is subjective and constructed through individual interactions within South Korean elite sports teams. Epistemologically, it posits that knowledge is co-constructed by researchers and participants, with the researcher interpreting participants’ perspectives within a broader socio-cultural context. This paradigm enables a holistic exploration of the psychological mechanisms and dynamics in hierarchical, high-performance sports settings. The case study design followed these steps: defining the research problem, selecting participants, conducting interviews, analyzing recurring themes, and integrating findings with Freud’s theoretical framework, alongside SDT and SIT. Methodological rigor was maintained by mitigating potential biases and enhancing data credibility. For example, Freud’s concepts were integrated with SDT’s focus on autonomy and SIT’s emphasis on group identity to ensure a balanced and comprehensive perspective on the participants’ experiences.

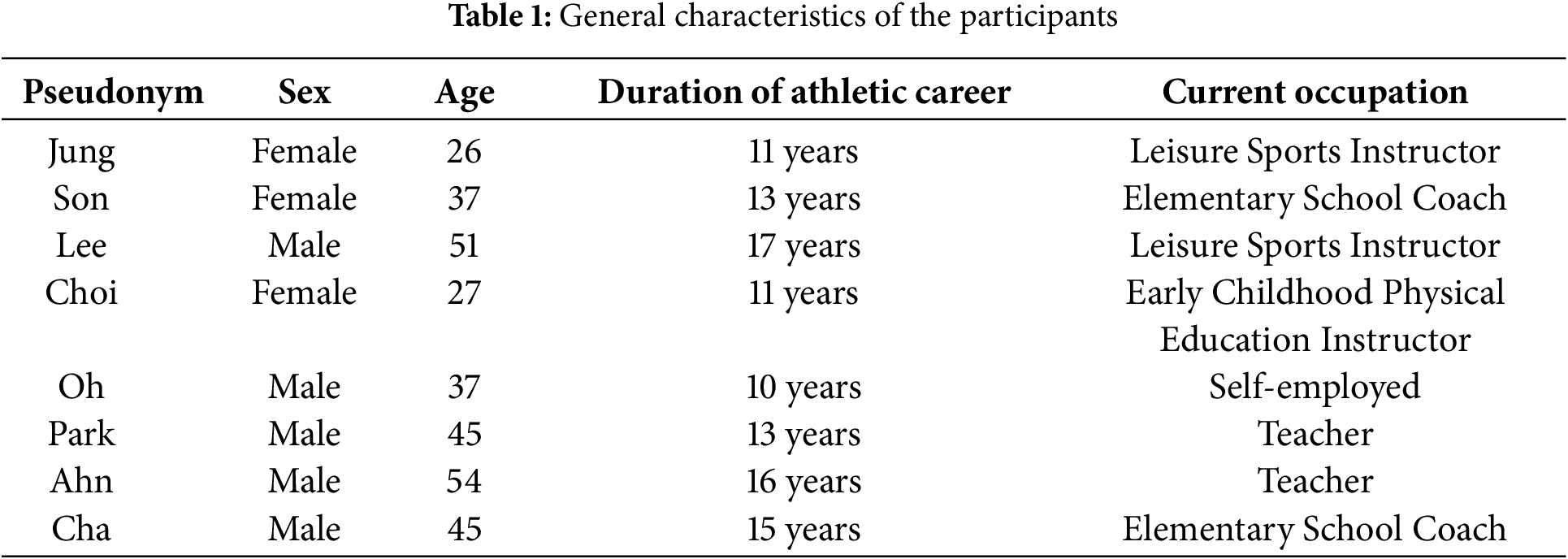

The participants comprised eight retired elite table tennis players who competed at national or international levels in South Korea. Participant selection employed purposeful sampling [27], focusing on individuals with direct experience of hierarchical pressure, authority dynamics, and mental health challenges in elite sports. Purposeful sampling ensured the representation of broader trends in South Korean elite sports and allowed for a nuanced exploration of the shared psychological dynamics and hierarchical pressures. Efforts to enhance diversity included capturing varied experiences reflective of cultural and organizational shifts in elite sports. Data collection adhered to Creswell saturation principles [26], ceasing once no new insights emerged. Participants, aged 26 to 54, reflected a diverse range of athletic experiences across generational cohorts.

To address the selection bias inherent in snowball sampling, professional networks, and sports organizations were used for additional recruitment. This strategy enhanced participant diversity while retaining relevance to elite sports experiences. Variability due to the wide age range was systematically analyzed. Generational differences in coaching practices and socio-cultural expectations were examined to ensure the findings accounted for temporal and organizational shifts in South Korean elite sports. For instance, younger participants in their mid-20s described athlete-centered coaching, whereas older participants recounted exposure to authoritarian methods prevalent in earlier decades.

After retiring from elite sports, the participants pursued various professional paths, such as leisure sports instructor, elementary school table tennis coach, early childhood physical education instructor, self-employment, and physical education teacher. This diversity in post-retirement careers provided a rich set of perspectives on the long-term impact of elite sports experiences on athletes’ mental health and ego development. The participants’ detailed reflections on their athletic careers and subsequent life choices added depth to the research findings and revealed how early experiences in elite sports shaped their psychological growth and mental health. Table 1 presents the general characteristics of these participants.

Data collection occurred between April and June 2022 and involved 3–4 in-depth, one-on-one interviews with each participant, lasting 60–90 min per session. Semi-structured interview guides ensured consistency while allowing flexibility for emerging themes [28]. Multiple sessions fostered trust and enabled participants to share richer and more reflective narratives, accommodating individual differences in communication styles and openness.

Interview questions addressed Freudian mechanisms, such as identification and ego idealization, alongside SDT dimensions—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—and SIT’s focus on balancing individual and group identity. Participants reflected on how team dynamics, authority figures, and hierarchical pressures influenced their sense of self, autonomy, and psychological well-being. Questions explored experiences with conformity, the role of coaches and senior athletes, and the mental health impacts of these dynamics.

To ensure participants felt safe sharing sensitive experiences, such as corporal punishment or mental health struggles, interviews were conducted empathetically, with prior consent and the option to skip questions. Psychological support resources were offered after each interview, although none were used.

All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and validated through follow-up correspondence to minimize recall bias. This process ensured the comprehensive capture of participants’ perspectives while triangulating insights with existing literature on South Korean sports culture. By integrating Freud’s framework with SDT and SIT constructs, the data collection facilitated an in-depth exploration of the psychological mechanisms in hierarchical sports environments.

Thematic analysis was employed to identify and examine patterns in the data, focusing on psychological constructions such as ego development, group dynamics, and mental health. This approach aligns with thematic analysis principles, emphasizing flexibility and rigor in identifying recurring themes in qualitative data [29]. The coding scheme integrated Freudian mechanisms, such as identification and ego repression, alongside SDT dimensions of autonomy and competence and SIT constructs of group identity vs. individual identity balance. For example, the theme “loss of autonomy due to hierarchical authority” was analyzed through SDT, whereas “identity tension within team dynamics” was interpreted using SIT. This multi-framework approach ensured a comprehensive analysis of the psychological mechanisms in hierarchical sports teams.

Initial coding was conducted by two independent researchers, prioritizing themes such as “ego repression due to hierarchical pressure” and “impact of group conformity on mental health”. These themes emerged iteratively through constant comparison across transcripts, ensuring that the analysis captured the shared experiences of participants. To ensure methodological rigor, the analysis adhered to the principles outlined by Krippendorff [30] and Saldana [31], which highlight the importance of consistency and reliability in qualitative coding. The inter-coder agreement was established through multiple rounds of coding comparisons, where discrepancies were resolved collaboratively. This systemic and iterative process aligns with the recommendations, enhancing accuracy and relevance in qualitative research [32].

The validation of themes was guided by Creswell et al., emphasizing alignment with the research framework and participant accounts [33]. For example, the theme “ego repression due to hierarchical pressure” was substantiated by participants’ descriptions of how hierarchical authority suppressed their desires and shaped their behaviors. These narratives were cross validated with broader cultural studies, ensuring relevance beyond the specific dataset. Triangulation with existing literature on South Korean sports culture enhanced the credibility of the findings. This approach aligns with the emphasis on contextual validation to strengthen analytic conclusions [34]. For instance, recurring patterns of authority-driven conformity and its psychological consequences were supported by participant narratives and existing studies, ensuring theme reliability.

To address challenges in qualitative data reliability, the study incorporated rigorous peer debriefing and iterative review, ensuring the final themes accurately represented the data. While thematic analysis does not rely on quantitative measures, future research could integrate standardized psychological assessments, such as anxiety or burnout scales, for a more comprehensive understanding of hierarchical sports environments.

3.5 Integrity and Ethical Considerations

Several strategies were employed to ensure integrity and ethical rigor. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured of their right to withdraw at any stage. Anonymity was maintained by using pseudonyms and removing all identifying details from the data. Sensitive topics, such as corporal punishment and mental health struggles, were approached cautiously, with interview protocols emphasizing respect and empathy to minimize distress. Psychological support resources were offered, but no participants reported needing additional assistance during or after the interviews.

The study adopted member reflection to foster collaboration and reduce power imbalances between researchers and participants. This approach enabled participants to contribute actively to the interpretation of findings, enhancing the study’s credibility [30,35]. Peer debriefing and triangulation reinforced trustworthiness, aligning with qualitative research recommendations [33].

Additionally, strict data security measures were implemented, including password-protected data files and secure storage of all research materials. Furthermore, this study adhered to the highest ethical standards and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Sogang University, Seoul, Korea (SGUIRB-A- 2204-17).

This study examined the psychological mechanisms that shape athletes’ ego formation and mental health in South Korean elite sports teams, integrating Freud’s theory of group psychology with insights from SDT and SIT. The findings revealed four major constructs illustrating psychological forces in hierarchical, high-pressure environments: identification and ego idealization, hierarchical order and obedience, group pressure, and ego erosion, and the role of corporal punishment.

4.1 Manifestation of Identification and Ego Idealization

Participants frequently described internalizing the values and expectations of authority figures, such as coaches and senior athletes. These identification and ego idealization processes shaped their sense of self and ego development, revealing both positive and challenging psychological dimensions.

Oh described how his coach’s emphasis on perseverance became a defining part of his identity. He recounted enduring rigorous training from a young age:

“I have this perseverance, you know, until we decide we’re done. I’ve endured tough training since elementary school, even when I didn’t want to. That endurance still feels like a part of who I am now.”

This quote demonstrates that Oh internalized his coach’s values, particularly perseverance, as core elements of his identity. Freud’s theory of identification explains how athletes internalize authority figures’ values, making them central to their ego. Oh’s account underscores how his coach’s emphasis on perseverance became a critical aspect of his self-concept. However, SDT suggests that such alignment with external values may suppress personal autonomy, potentially contributing to emotional strain if the athlete’s aspirations are not adequately addressed.

Park offered another perspective, reflecting on how his coach’s encouragement shaped his motivation and self-concept:

“He was a teacher I could respect. Whether in training or personal life, he always encouraged us, saying, ‘You’re the best, you’ll succeed.’ I loved those words and kept trying not to give up, just as he used to say.”

Freud posited that idealized authority figures shape individual identity by reinforcing motivation and resilience. Park’s experience illustrates this, as his coach’s affirmations became a source of personal strength. However, SIT highlights the tension that can arise when athletes prioritize group cohesion or the expectation of authority figures over personal identity, potentially causing identity conflicts in high-pressure environments.

Jung recounted her admiration for a senior athlete, which inspired her to emulate their behavior.

“I saw her train alone, even outside of team practice. So, I tried to do more personal training, wanting to become an ace like her. I realized that becoming an ace doesn’t just happen on its own.”

Freud’s framework explains how identifying with role models reshapes ego structures as athletes align their behaviors with admired figures. Jung’s actions reflect this process, demonstrating how role models influence athletes to adopt external values. From an SIT perspective, such alignment may enhance group cohesion but can create psychological tension if personal goals are overshadowed by group norms.

These findings reveal the influence of identification and ego idealization in shaping athletes’ behaviors and psychological development in South Korean elite sports teams. While these processes foster group cohesion and resilience, they pose risks of autonomy suppression and identity conflict. Integrating insights from SDT and SIT underscores the need for a balanced approach that supports individual autonomy and identity within team dynamics.

4.2 Impact of Hierarchical Order and Obedience on Ego Formation

Participants reported that hierarchical structures imposed strict expectations, significantly influencing their autonomy and self-concept. These pressures often suppress individual autonomy.

Jung recounted the pressures stemming from hierarchical structures:

“The seniors were more intimidating than the coaches. We had no choice but to follow their orders. We did not even have time to think differently. All we wanted was to get along with them.”

This testimony underscores the psychological toll of conformity in hierarchical environments. Freud’s theory posits that such pressures compel individuals to suppress personal desires and align their behaviors with group norms, a dynamic illustrated by Jung’s account. The relentless demand for conformity limited her autonomy, fostering an environment where adherence to senior athletes’ authority superseded personal expression.

Oh shared his experience of compliance to avoid punishment:

“The team was incredibly strict. In the first week of training, I was late by just five minutes, but the seniors punished me severely. After that, I made sure I was always ready on time. There was no other way to avoid punishment.”

This account reveals the fear-driven compliance enforced by hierarchical systems. Freud’s framework suggests that such compliance reshapes the ego, prioritizing submission to external authority over personal autonomy. Internalizing fear as a behavioral motivator demonstrates the deep psychological impact of hierarchical discipline.

Ahn described the continued use of hierarchical punishment within his team:

“At our school, the seniors administered corporal punishment. The coach would leave early, and the team captain would take over. The punishment would continue down the line. If the coach left early, we would all be on edge.”

Ahn’s narrative reflects how hierarchical structures enforce conformity and perpetuate punishment systems that suppress individual autonomy. While fostering discipline, such systems often result in long-term psychological consequences, including heightened anxiety and diminished self-esteem.

Cha offered a stark depiction of his experience with strict obedience:

“It was like living in darkness. From the very beginning, it was hell.”

This quote highlights the psychological cost of strict obedience, which often leads to the suppression of autonomy. Freud’s theory explains that such dynamics enforce conformity and alter ego development, as athletes subordinate their desires to the needs of the group.

The findings reveal that hierarchical structures in South Korean elite sports teams exert substantial pressure on athletes to conform to authority figures. This conformity suppresses autonomy and reshapes athletes’ identities to align with external expectations. The process, as outlined in Freud’s theory, links hierarchical pressure to ego repression, resulting in long-term psychological consequences, such as reduced self-esteem and heightened anxiety. To address these issues, fostering an environment that balances authority with autonomy is critical to mitigating the adverse psychological impacts of hierarchical systems.

4.3 Effect of Group Pressure on Ego Erosion and Mental Health

Son’s account illustrates the detrimental impact of group pressure on mental health. Freud’s theory posits that group norms and external expectations suppress personal desires, fostering ego erosion and increased vulnerability to mental health challenges, such as anxiety and depression.

Cha reflected on the long-term effects of group expectations:

“I felt like I had no choice but to succeed in table tennis. I couldn’t keep up with my schoolwork, and I had no confidence. Eventually, I just thought, ‘I have to focus on table tennis.’ It became my only choice.”

Cha’s narrative underscores how intense group expectations reshaped his ego, forcing him to prioritize sports over academic or personal aspirations. This suppression of autonomy aligns with Freud’s theory, which explains that conformity to group demands reduces the space for individual growth and fosters identity conflicts.

In a supplementary interview, Cha elaborated on the psychological toll of hierarchical living arrangements:

“Living with seniors, training, and sharing a dorm with them... It was like living in darkness. Eventually, the bullying became so intense that I had to transfer to another school.”

This testimony highlights the psychological strain caused by hierarchical group dynamics. Freud’s framework explains that persistent exposure to oppressive group norms and authority figures exacerbates ego erosion, leading to issues such as social isolation, identity confusion, and chronic stress.

Jung offered a perspective on the emotional consequences of group pressure:

“As a table tennis player, I became increasingly self-conscious. I started to feel small and lost confidence.”

Jung’s experience reflects how group expectations weakened her self-concept and autonomy, diminishing her confidence and exacerbating self-doubt. Freud’s concept of ego repression supports these findings, emphasizing that suppressing personal desires to conform to group norms can have lasting negative effects on ego development and mental health.

The findings reveal that group pressure within elite sports teams compels athletes to internalize collective norms and values, often at the expense of their identity. This suppression of personal aspirations results in long-term ego erosion and contributes to mental health issues such as depression, identity confusion, and chronic stress. These outcomes underscore the need for interventions that promote individual autonomy and psychological resilience in hierarchical team environments.

4.4 Role of Corporal Punishment in Identification and Ego Idealization

Corporal punishment was a key factor in enforcing conformity and reshaping identity among participants. This disciplinary method imposed physical and psychological strain, fostering obedience at the expense of autonomy and long-term mental health.

Son shared her experience of corporal punishment:

“The seniors were extremely strict. We were frequently disciplined, and the seniors would continue the punishment even after the coach left. That period was very tough, both physically and mentally.”

Son’s testimony highlights the dual impact of corporal punishment: it enforced conformity while suppressing autonomy. Freud’s theory of ego repression suggests these practices inhibit personal desires, fostering internal conflict and long-term psychological distress.

Oh shared a similar experience, describing how corporal punishment shaped his behavior:

“Even if it wasn’t my mistake, my coach always punished me. We were hit a lot, and it seemed to work. That’s why the school had such a strong reputation.”

Oh’s account reflects the immediate efficacy of punishment in enhancing performance but underscores its psychological cost. While fear-based methods may achieve short-term compliance, Freud’s framework warns that they foster internalized conflict and contribute to lasting ego distortion.

Choi’s experience portrayed corporal punishment as a tool for not only discipline but also psychological control:

“We would be suddenly beaten, and it was terrifying. It had a mental toll on us. I felt that I performed better because I was afraid of being punished.”

Choi’s narrative illustrates how fear-driven discipline suppresses autonomy, aligning behavior with the expectations of authority figures. Freud’s theory posits that this suppression leads to the restructuring of the ego, often resulting in diminished self-identity and heightened psychological stress.

Lee elaborated on how fear influenced his performance:

“The coach was terrifying, and that fear made us more focused. We practiced more, and, of course, our skills improved. Somehow, getting hit made us better.”

Lee’s account acknowledges the short-term performance benefits of corporal punishment but aligns with Freud’s caution regarding its long-term costs. Persistent fear undermines resilience, fostering anxiety and a loss of autonomy.

The findings reveal that corporal punishment in South Korean elite sports teams serves as both a disciplinary tool and a mechanism for reshaping ego. While enforcing conformity and temporarily enhancing performance, Freud’s framework highlights its detrimental effects on mental health, including anxiety, diminished self-identity, and chronic insecurity. These outcomes emphasize the need for supportive coaching methods that maintain discipline while prioritizing athletes’ psychological well-being and autonomy.

This study examined the psychological mechanisms underlying athletes’ ego formation and mental health in South Korean elite sports teams, using Freud’s theory of group psychology as the primary theoretical framework. The findings highlight how identification, ego idealization, hierarchical obedience, and group pressure shape athletes’ psychological experiences within high-performance, hierarchical environments. These mechanisms erode personal autonomy and exacerbate mental health challenges, such as anxiety, burnout, and identity conflicts [20,36]. To address these challenges, integrating Freud’s insights with contemporary theories like SDT and SIT offers a more holistic understanding of how group dynamics influence mental health outcomes.

First, our results showed that identification and ego idealization are key psychological mechanisms that shape the egos of South Korean elite athletes. Aligning with Freud’s theory of identification [36], athletes tend to internalize the values, behaviors, and expectations of authority figures such as coaches and senior teammates. This internalization fosters dependency on external validation, often at the expense of personal autonomy. One participant noted how aligning their identity with their coach’s expectations became central to their self-concept, reinforcing Freud’s notion that identification suppresses individual desires and fosters conformity to authority figures [37].

In hierarchical sports environments, identification is reinforced by group pressure to conform to shared norms and expectations. This dynamic appeared in participants’ accounts of modeling their behavior on idealized authority figures. Freud’s concept of the group leader as a “father figure” underscores the psychological influence of authority figures in shaping ego development [11]. However, such environments often suppress personal growth and autonomy, increasing athletes’ reliance on external expectations [38,39].

SDT emphasizes that environments fostering autonomy are crucial for psychological well-being [20]. Athletes’ accounts revealed how hierarchical dynamics limited their autonomy, increasing psychological tension and vulnerability to mental health challenges. Rice et al. [20] emphasized that elite athletes in such environments face heightened risks of anxiety and depression, aligning with Freud’s assertion that identification leads to internal conflict and mental strain.

In addition to Freud’s framework, SIT provides valuable insights into the identity tension athletes experience. SIT posits that excessive alignment with group norms can diminish individuality and increase psychological stress [13]. Participants described the emotional toll of prioritizing team cohesion over personal aspirations, highlighting the interplay between identification and group identity as a source of psychological tension.

Overall, these findings underscore the need for targeted interventions that address the psychological challenges associated with identification and ego idealization. Programs promoting autonomy in ego development, reducing dependency on external expectations, and fostering psychological resilience are essential [36,40]. By integrating insights from SDT and SIT, such interventions can provide a comprehensive approach to enhancing mental health and well-being in hierarchical sports settings.

Second, our results showed that hierarchical structures and obedience (particularly athletes’ relationships with their coaches and seniors) play a crucial role in shaping their ego formation. Freud’s theory of group psychology emphasizes that obedience to authority suppresses individual autonomy and leads to heightened psychological pressure. Hierarchical settings compel individuals to align their behaviors with external expectations, reinforcing conformity at the expense of personal autonomy [11,41].

SDT emphasizes that hierarchical sports environments hinder basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—diminishing intrinsic motivation and increasing psychological distress [13]. Similarly, SIT highlights how conformity to group norms creates identity conflicts, forcing athletes to prioritize group cohesion over personal identity, and exacerbating mental health challenges [15]. This study found group pressure and corporal punishment to be closely intertwined. Group pressure drives athletes to suppress autonomy and conform to collective expectations, while corporal punishment enforces conformity, creating a cycle of obedience and dependency. Freud’s theory of ego repression suggests these dynamics contribute to anxiety and identity conflicts by suppressing personal desires [20].

Testimonies from participants, such as Park and Oh, illustrate how hierarchical settings suppress autonomy and reinforce conformity through fear and strict discipline, leading to long-term psychological challenges such as anxiety and diminished self-concept [37,42]. From an SDT perspective, these environments amplify stress and mental health risks by inhibiting autonomy and competence, while SIT explains how prioritizing group norms over individual identity increases psychological tension [13,15]. Accounts from Ahn and Choi highlight the role of corporal punishment in reinforcing obedience, eroding independence, and fostering internal conflict, aligning with SDT’s assertion that autonomy suppression heightens the risk of burnout and mental distress [13].

Freud’s theory of obedience explains how excessive conformity to authority figures distorts the ego and contributes to mental health problems, such as identity confusion and anxiety [43]. Freud’s ideas have provided a foundation for understanding how these issues are exacerbated by group dynamics, particularly those in hierarchical settings [10,11]. Empirical evidence also supports this notion by highlighting that the burden of conforming and performance expectations in elite sports exacerbates mental health issues [7,20]. By integrating SDT and SIT, this study emphasizes the need for interventions in hierarchical sports environments to prioritize autonomy-supportive practices and balance individual identity with team cohesion. These frameworks emphasize that fostering intrinsic motivation and aligning athletes’ identities within group dynamics can alleviate the psychological burden of hierarchical conformity [13,15].

Overall, there is an urgent need for psychological interventions that mitigate the negative effects of hierarchical structures on athletes’ autonomy and mental health. These interventions should reduce excessive reliance on authority figures, foster autonomy, and promote healthy coping mechanisms to manage the psychological burden of conforming [7,8,43]. SDT-informed approaches enhance athletes’ autonomy and competence, while SIT-based strategies foster team environments valuing individual identities alongside collective goals, reducing identity conflict and promoting mental well-being [13,15].

Third, our results showed the salient role of group pressure in ego formation in South Korean elite sports teams. Freud’s theory suggests that group pressure is a strong force for ego repression, as it pushes individuals to conform to external norms and expectations [40,44]. Freud explained that group dynamics undermine individual autonomy. Over time, this continuous pressure erodes athletes’ autonomy and propagates psychological conflict, stress, and long-term mental health issues [11,37,45].

Purcell et al. [46] found that young elite athletes are particularly vulnerable to long-term mental health problems due to the intense performance pressures they face early in their careers. These early pressures shape their ego development and often lead to identity confusion and ego suppression, which can persist into adulthood. In South Korean elite sports teams, such pressures are exacerbated by hierarchical structures that demand conformity from a young age, mirroring Freud’s concept of ego repression. External pressures during key developmental stages inhibit autonomous ego formation, deteriorating one’s mental health over time.

Pervasive group pressure in hierarchical sports forces athletes to prioritize team expectations over autonomy. As pressure builds, athletes’ ability to maintain a distinct personal identity is suppressed. SDT highlights that autonomy suppression contributes to emotional exhaustion, burnout, and decreased intrinsic motivation [13]. Autonomy-supportive interventions can alleviate these effects by enabling athletes to make self-directed decisions. SIT underscores that excessive group identification at the expense of personal identity results in identity conflicts and psychological tension [15].

Feddersen et al. [47] found that hierarchical structures in elite sports exacerbate pressures through fear, punishment, and isolation, enforcing group conformity. These findings parallel the dynamics in South Korean elite sports, where constant pressure to conform, coupled with the fear of punishment or exclusion, intensifies the psychological toll on athletes, suppresses their autonomy, and represses their ego.

Son’s and Cha’s experiences exemplify Freud’s theory of ego repression, where external pressures erode autonomy, increase anxiety, and suppress personal identity under group expectations. Purcell et al. [46] argued that early experiences of pressure, particularly in youth, increase vulnerability to mental health problems in later life. Freud’s theory aligns with this, suggesting that autonomy suppression causes long-term psychological tension and conflict. SDT complements these insights by emphasizing that environments failing to satisfy basic psychological needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, significantly impair mental well-being [13].

Choi’s case also demonstrated how group pressure stifles ego independence. As a table tennis athlete, she struggled to meet external expectations, which hampered her self-esteem and increased mental health risks. This reflects Freud’s view that group conformity fosters psychological tension and conflict [43]. SIT highlights how Choi’s experience illustrates the detrimental effects of prioritizing team norms over individual identity, causing unresolved identity tension. Team-building programs that celebrate individuality can help mitigate these risks [15].

Feddersen et al. [47] reported that destructive sports environments, particularly those with hierarchical dynamics, create conditions in which athletes’ autonomy is continuously eroded, causing burnout, anxiety, and depression. Purcell et al. [46] further emphasized that young athletes exposed to these pressures without adequate mental health support are at a heightened risk of long-term psychological issues (e.g., burnout and identity confusion) as they transition to adulthood. Furthermore, Kumar et al. [8] warned that unresolved group pressure can not only cause mental health problems (e.g., depression and burnout) but also affect athletic performance.

Integrating SDT and SIT offers practical pathways for interventions. SDT approaches should foster autonomy and intrinsic motivation, while SIT strategies should balance individual and group identities to enhance psychological resilience. Effective interventions should include mental training programs to strengthen athletes’ resilience and promote autonomy. Coaching practices must shift from authoritarian models to foster psychological safety and encourage individuality. These efforts could mitigate group pressure’s psychological effects and support athletes’ mental health and well-being [47,48].

Fourth, our results showed that corporal punishment significantly influences athletes’ ego formation in South Korea’s elite sports groups. A review of mental health risk factors identified corporal punishment as a key environmental risk factor that exacerbates psychological stress and undermines autonomy [48]. Freud suggested that authority figures (such as coaches) can suppress personal autonomy, contributing to heightened psychological stress [11,49]. This suppression extends beyond physical discipline and functions as a form of psychological repression, significantly influencing ego development [37].

Corporal punishment in hierarchical sports settings exacerbates the psychological strain on athletes, reinforcing group conformity. Athletes are conditioned to comply with strict norms, using corporal punishment as a tool to enforce conformity. This suppresses autonomy and distorts athletes’ sense of self as they align their behavior with authority figures’ expectations. From an SDT perspective, punitive environments suppress the fulfillment of basic psychological needs, particularly autonomy and competence, which are essential for mental well-being [13]. SIT posits that coercive conformity through corporal punishment amplifies identity conflicts, forcing athletes to prioritize group cohesion over personal authenticity [15].

Son’s experience illustrated that corporal punishment not only has a physical impact but also induces psychological pressure. This pressure forces athletes to internalize fear, which compels them to align their egos with the expectations of authority figures. Consequently, their autonomy is suppressed. This aligns with the findings of previous studies showing that harsh disciplinary practices increase the risk of long-term psychological issues in athletes, thus necessitating targeted interventions [50]. Similarly, Oh’s case demonstrated that recurrent corporal punishment forces athletes to conform to external standards and modify their ego to meet these expectations. Over time, this erodes their autonomy, as individuals over-identify with the authority figure [21,44,51].

Choi’s experience further exemplified that corporal punishment is a powerful tool for psychological repression. Because of fear, athletes are compelled to conform to the demands of coaches and senior athletes. This process not only impacts immediate behavior but also has long-term mental health consequences, such as anxiety, internal conflict, and depression [8,43]. SDT emphasizes that coercive practices undermine intrinsic motivation and emotional well-being. Similarly, SIT suggests that such environments heightened dependence on group validation, amplifying the psychological toll of hierarchical conformity [13,15]. These examples emphasize that corporal punishment can severely impact both ego development and mental health, reinforcing Freud’s theory that repression under external pressure leads to psychological distress. Integrating SDT and SIT, these findings highlight that fear-driven, coercive environments undermine the psychological resilience required for long-term mental health [13,15].

Overall, our findings demonstrate that identification, ego idealization, hierarchical obedience, group pressure, and corporal punishment significantly shape athletes’ mental health in South Korean elite sports teams. These mechanisms, especially in high-performance, hierarchical environments, suppress autonomy and heighten mental health risks. Freud’s framework provides foundational insights into unconscious group dynamics, while SDT and SIT offer strategies to foster autonomy and balance individual and group identities. SDT emphasizes autonomy, competence, and relatedness, offering a framework to alleviate psychological pressures in hierarchical sports settings. Similarly, SIT highlights the importance of balancing team cohesion with individual identity to mitigate identity conflicts and promote psychological well-being [13,15].

Our study highlights the urgent need for interventions to address group pressure and corporal punishment in elite sports. Psychological support programs are needed to promote autonomy, resilience, and long-term mental health. These programs can help athletes manage the psychological dynamics of identification and ego idealization, offering a pathway to improved well-being [20,36]. Additionally, the replacement of corporal punishment with supportive coaching practices that prioritize psychological safety, mental well-being, and autonomy is urgently needed. Coaches should receive training to develop supportive relationships with athletes and to promote an environment that enhances both independent ego formation and mental health [11,45,47,49].

This study, despite its contributions, has several limitations. The small sample size and retrospective data limit the findings’ generalizability. Future research should use larger, more diverse samples and longitudinal designs to explore the long-term psychological impacts of hierarchical structures and disciplinary practices. Integrating quantitative mental measures, such as validated anxiety or burnout scales, would enhance the findings’ robustness. Extending the study to various sports contexts could provide broader insights into how hierarchical dynamics affect athletes in different settings.

This study examined the effects of identification, ego idealization, hierarchical order, obedience, group pressure, ego erosion, and corporal punishment on the ego formation and mental health of athletes in South Korea’s elite sports groups using Freud’s theory of group psychology. The findings illustrate that these elements play a critical role in shaping the psychological development and well-being of athletes. Identification and ego idealization in hierarchical environments were found to suppress athletes’ autonomy, while group pressure and corporal punishment exacerbated psychological distress, anxiety, and identity erosion.

To address these challenges, systematic psychological support programs tailored to the unique pressures faced by elite athletes are urgently needed. These programs should include regular individual counseling and team-based workshops to build psychological resilience and foster autonomy. Structured discussions on managing external pressures and improving self-awareness can empower athletes to navigate hierarchical environments. Coaching practices must shift from punitive approaches to autonomy-supportive strategies that prioritize athletes’ psychological safety and well-being. Coaches should be trained to offer constructive feedback, involve athletes in decisions about training and competition schedules, and reduce fear-based discipline. These strategies align with SDT, which emphasizes fulfilling athletes’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Additionally, interventions rooted in SIT should balance individual identity with group cohesion. Team-building activities integrating personal goals with collective objectives can foster a sense of belonging while preserving individual identity. For instance, group workshops could focus on enhancing mutual respect among team members while allowing athletes to articulate and pursue their aspirations within the team dynamic. Finally, corporal punishment should be replaced with reinforcement methods that respect athletes’ dignity and promote psychological well-being. Coaches should learn alternative disciplinary strategies, such as positive reinforcement and goal-setting, to create a psychologically safe and supportive environment. For example, replacing punishment with incentives for teamwork and effort can motivate athletes without compromising their mental health.

This study underscores the urgent need for systemic changes in elite sports culture and practices. Evidence-based psychological interventions and supportive coaching can help sports organizations promote athletic success and long-term psychological well-being.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Study design: Hyunkyun Ahn; conceptualization: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi; study conduct: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi, Young-Vin Kim; data collection: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi; data analysis: Hyunkyun Ahn, Young-Vin Kim; data interpretation: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi, Young-Vin Kim; drafting the manuscript: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi, Young-Vin Kim; revising manuscript content: Hyunkyun Ahn, Yeon-Hee Choi, Young-Vin Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Sogang University, Seoul, Korea (SGUIRB-A-2204-17). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hong D. Establishing new sports paradigm and future task through the sports reform committee policy documents analysis in South Korea. Korean J Phys Educ. 2020;59(2):285–302. (In Korean). doi:10.23949/kjpe.2020.3.59.2.285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kim H, Hong DK. Achievements and challenges of a national organization for the protection and promotion of human rights in sport: a case of the ‘Special Investigation task force on human rights in sports’ in the national human rights commission of Korea. Korean J Phys Educ. 2022;61(4):323–42 (In Korean). doi:10.23949/kjpe.2022.11.61.6.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Choi NY, Kim YV, Ahn H. Utilizing topic modeling to establish sustainable public policies by analyzing Korea’s sports human rights over the last two decades. Sustainability. 2024;16(3):1323. doi:10.3390/su16031323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Song J, Kim H. Socioeconomic factors on Korean student athletes’ mental health: FGI research. J Sports Psychol Res. 2023;45(3):215–30. doi:10.58445/rars.2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kim Y, Han M, Lee JH. Sport and exercise psychology in Korea: three decades of growth. Asian J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2021;1(1):36–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajsep.2021.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yim YS, Hong DK. An exploration for the prevention of human rights violation in elite sports. Korean Assoc Sport Pedagog. 2021;26(3):57–76 (In Korean). doi:10.15831/JKSSPE.2021.26.3.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pilkington V, Rice SM, Walton CC, Gwyther K, Olive L, Butterworth M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental health symptoms and well-being among elite sport coaches and high-performance support staff. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):89. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00479-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar S, Devi G. Sports performance and mental health of athletes. Sports Sci Health Adv. 2023;1(1):46–9. doi:10.60081/SSHA.1.1.2023.46-49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Holowchak MA. Freud on play, games, and sports fanaticism. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2011;39(4):695–715. doi:10.1521/jaap.2011.39.4.695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Khushk A, Zengtian Z, Hui Y, Atamba C. Understanding group dynamics: theories, practices, and future directions. Malays E Com J. 2022;6(1):1–8. doi:10.26480/mecj.01.2022.01.08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Freud S. Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. In: Strachey J, editor. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 18. London, UK: Hogarth Press; 1955. p. 65–144. [Google Scholar]

12. Stempel C. Sport, social class, and cultural capital: building on Bourdieu and his critics. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2018;53(2):151–68. doi:10.31219/osf.io/5np83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol. 2008;49(3):182–5. doi:10.1037/a0012801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;61(3):101860. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. p. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

16. Haslam SA, Reicher SD, Platow MJ. The new psychology of leadership: identity, influence, and power. 2nd ed. London, UK: Routledge; 2020. doi:10.4324/9781351108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee SK. A study on ‘Masse’ of Sigmund Freud: focusing on Freud’s ‘Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse (1921)’ [dissertation]. Yemyung: Yemyung Graduate University; 2022 (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

18. Poucher ZA, Tamminen KA, Kerr G, Cairney J. A commentary on mental health research in elite sport. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2021;33(1):60–82. doi:10.1080/10413200.2019.1668496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sarı İ, Bayazıt B. The relationship between perceived coaching behaviours, motivation and self-efficacy in wrestlers. J Hum Kinet. 2017;57(1):239–51. doi:10.1515/hukin-2017-0065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rice SM, Purcell R, De Silva S, Mawren D, McGorry PD, Parker AG. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. Sports Med. 2016;46(9):1333–53. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lee KW, Lee JS. Psychological mechanism of perseverance of corporal punishment in the athletic group: focusing on S. Freud’s ‘Collective Psychology’. Korean Soc Sports Sci. 2023;32(4):123–34 (In Korean). doi:10.35159/kjss.2023.08.32.4.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bion WR. Experiences in groups and other papers. London, UK: Tavistock Publications; 1961. p. 139–52. doi:10.4324/9780203359075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Park JW, Lim SY, Bretherton P. Exploring the truth: a critical approach to the success of Korean elite sport. J Sports Soc Issues. 2012;36(3):245–67. doi:10.1177/0193723511433864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2014. p. 16–9. doi:10.3138/cjpe.30.1.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 1995. 33 p. [Google Scholar]

26. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2018. p. 185–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2015. p. 265–76. [Google Scholar]

28. Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 1996. p. 124–8. [Google Scholar]

29. Maguire M, Delahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J. 2017;8(3):3351–64. [Google Scholar]

30. Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA,USA: Sage Publications; 2004. p. 125–46. [Google Scholar]

31. Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2016. p. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

32. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2020. p. 107–21. [Google Scholar]

33. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2018. p. 255–8, 330–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Carter S. Case study method and research design: flexibility or ambiguity for the novice researcher? In: van Rensburg H, Neill SO, editors. Inclusive theory and practice in special education. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

35. Smith B, McGannon KR. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2017;11(1):101–21. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–22. doi:10.2307/3090197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Vereshchagina AV, Gafiatulina NK, Kumykov AM, Stepanov OV, Samygin SI. Gender analysis of social health of students. Rev Eur Stud. 2015;7(7):123–30. doi:10.5539/res.v7n7p223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bauman NJ. The stigma of mental health in athletes: are mental toughness and mental health seen as contradictory in elite sport? Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(3):135–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Souter G, Lewis R, Serrant L. Men, mental health and elite sport: a narrative review. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):57. doi:10.1186/s40798-018-0175-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gucciardi DF, Hanton S, Fleming S. Are mental toughness and mental health contradictory concepts in elite sport? a narrative review of theory and evidence. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(3):307–11. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Mageau GA, Vallerand RJ. The coach-athlete relationship: a motivational model. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(11):883–904. doi:10.1080/0264041031000140374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kline P. Psychology and Freudian theory: an introduction. 2nd ed. London, UK: Routledge; 2014. p. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

43. Fadare SA, Mae IL, Ermalyn LP, Kharen MG, Ken PL. Athletes’ health and well-being: a review of psychology’s state of mind. Am J Multidis Res Innov. 2022;1(4):44–50. doi:10.54536/ajmri.v1i4.551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Pavón-Cuéllar D. Introduction to the special issue: the 100th anniversary of Sigmund Freud’s group psychology. Psychother Polit Int. 2021;19(3):e1599. doi:10.1002/ppi.1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Reinboth M, Duda JL, Ntoumanis N. Dimensions of coaching behavior, need satisfaction, and the psychological and physical welfare of young athletes. Motiv Emot. 2004;28(3):297–313. doi:10.1023/B:MOEM.0000040156.81924.b8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Purcell R, Henderson J, Tamminen KA, Frost J, Gwyther K, Kerr G, et al. Starting young to protect elite athletes’ mental health. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(8):439–40. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Feddersen NB, Morris R, Littlewood MA, Richardson DJ. The emergence and perpetuation of a destructive culture in an elite sport in the United Kingdom. Sport Soc. 2019;23(6):1004–22. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1680639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi:10.1017/S0033291714000129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bartholomew KJ, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C. Self-determination theory and the darker side of athletic experience: the role of interpersonal control and need thwarting. Sport Exerc Psychol Rev. 2011;7(2):23–7. doi:10.53841/bpssepr.2011.7.2.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kuettel A, Larsen CH. Risk and protective factors for mental health in elite athletes: a scoping review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2020;13(1):231–65. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2019.1689574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Capitão CG. Freud’s theory and the group mind theory: formulations. Open J Med Psychol. 2014;3(1):24–35. doi:10.4236/ojmp.2014.31003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools