Open Access

Open Access

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Perceived Organisational Support and Job Satisfaction in Workers with Severe Mental Disorders: A Pilot Study

1 Faculty of Labour Sciences, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

2 Administration and Services Personnel Management Unit, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

3 Department of Sociology, Social Work and Public Health, Faculty of Labour Sciences, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

4 Safety and Health Posgraduate Programme, Universidad Espíritu Santo, Guayaquil, 092301, Ecuador

* Corresponding Author: Juan Gómez-Salgado. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(4), 507-515. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.063497

Received 16 January 2025; Accepted 20 March 2025; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

Background: Employment can support the recovery of individuals with Severe Mental Disorders by promoting autonomy, reducing hospital admissions and associated costs, fostering social connections, and providing structure to their daily lives. The objective of this pilot study was to analyse job satisfaction and perceived social support in people with severe mental disorders who are users of an Employment Guidance and Support Service in southern Spain. Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional pilot study was carried out with a sample of 39 workers with mental disorders from the province of Huelva (southern Spain) who were users of the Employment Guidance and Support Service of the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain). Perceived Organisational Support was assessed with the Spanish short version of the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support and the S10/12 Job Satisfaction Questionnaire. Results: As findings, 87.2% of the sample reported high levels of job satisfaction, and 61.5% of the subjects surveyed perceived high levels of support. Regarding the variable Perceived Support, 84% of workers from ordinary companies and 50% of those from Special Employment Centres (SECs) considered that they had sufficient support. There was a positive correlation between support and satisfaction (Spearman’s Rho = 0.423). Conclusion: The results suggest a positive relationship between support and satisfaction, warranting further longitudinal research with larger samples. This pilot study provides preliminary insights into the relationship between perceived organizational support and job satisfaction among workers with severe mental disorders.Keywords

Abbreviations

| SMD | Severe Mental Disorders |

| POS | Perceived Organizational Support |

| FAISEM | Andalusian Public Foundation for the Social Integration of People with Mental Illness |

| SEC | Special Employment Centre |

| SPOS | Survey of Perceived Organizational Support |

Employment is key to the integration and community participation of people with severe mental disorders (SMD), allowing for a normalised social role as workers and resulting in improved mental health and reduced hospitalisations [1,2]. However, research in this area remains limited, and it is important to consider factors such as the severity of the disorder, specific diagnoses, and the duration of employment, which may influence job satisfaction and perceived support.

Although working favors recovery, there are barriers (rigid social relations, stress, precariousness) and facilitators (social relations, improved health, usefulness, time structuring) that influence the work experience of this population group [3]. In Spain, 17.4% of persons with mental disabilities are of working age, but they have the lowest employment rate in the active population due to factors such as the evolution of the disease, the effects of treatment, and social barriers [4,5].

To promote work integration, various legal frameworks support initiatives such as Individualized Supported Employment and Sheltered Employment [4,6]. The latter represents a significant share of employment opportunities for people with disabilities in many countries. Sheltered employment organizations typically maintain a workforce with a high percentage of employees with disabilities and provide personal and social adjustment services through dedicated support units. These units play a crucial role in facilitating integration, career development, and long-term retention in the labor market for this population [6,7].

In addition, job satisfaction and perceived organizational support (POS) are essential following recruitment. Organizational support improves psychological well-being, job satisfaction, and performance and reduces stress [8–10]. Job satisfaction understood as a positive emotional response, depends on factors such as supervision, environmental conditions, and performance [11,12]. The present study aims to provide preliminary data to inform future larger-scale studies. This pilot study analyzed job satisfaction and perceived social support in people with severe mental disorders who were users of an employment service in southern Spain.

A quantitative, cross-sectional pilot and correlational study was carried out using a non-experimental and purposive design.

2.2 Description of the Centre of Data Collection

The Employment Guidance and Support Service of Huelva is part of FAISEM (the Andalusian Public Foundation for the Social Integration of People with Mental Illness). This entity provides services to individuals with mental disability resulting from SMD or other types of mental illnesses or intellectual disabilities who are actively seeking employment. These individuals may either remain in the labor market continuously or experience employment intermittently. In this way, users in the Huelva capital and province (southwest of Spain) receive services provided by five Community Mental Health Units in the area: County, Coast, Mountains, Huelva capital, and Andevalo.

In 2020, this service provided care to 398 people with mental disorders, 240 men and 158 women, 123 of whom found employment. 73 of the 123 were people with SMD belonging to one of the five Mental Health Units in Huelva and province and with a referral protocol to the Support Service from their Mental Health provider.

In order to obtain preliminary insights, a small sample of 39 participants was selected. In this sense, 39 people with SMD (10% of the study population) agreed to participate in the study. These participants were either employed or had been employed within the previous year (January–December 2020) in an ordinary company, a Special Employment Centre (SEC), or a Social Company. They were contacted by telematic means (telephone-WhatsApp) and/or in-person to explain the purpose of the questionnaire and to resolve any doubts and insist on the anonymity of the questionnaire.

Ultimately, 39 individuals with SMD (53.43% of the study population) agreed to participate in the study. These participants were either employed or had been employed within the previous year (January–December 2020) in an ordinary company, an SEC, or a social company.

Both instruments were linguistically adapted to enhance comprehension. In addition, the first items are used to collect socio-demographic and employment variables (age, sex, time of experience, place of work, etc.).

2.4.1 Perception of Organizational Support

Adapted into Spanish by Ortega in 2003 [13] from the short version of the original Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS) by Eisenberger et al. [14]. The instrument has 16 items with a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). In this shortened version, the questionnaire has ten items worded in the positive and six items worded in the negative. When analyzing these data, the negatively worded items were added up inversely. This scale was subjected to a reliability coefficient test, obtaining a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93, which shows the reliability of this version [14].

The S10/12 Job Satisfaction Questionnaire developed by Meliá et al. [12] was used, which consists of 12 items and has a 7-point Likert scale: (1 = Very dissatisfied, 7 = Very satisfied). This third revision has been reduced to these 12 items, is simpler and shorter to administer, and still maintains an adequate degree of homogeneity and reliability, with a reliability coefficient of 0.88 (Cronbach’s alpha). The questionnaire consists of three dimensions: Satisfaction with the Environment (first five items), Satisfaction with Supervision (the next five items), and Satisfaction with the company’s performance (the last two items) [12].

For data collection, an Employment Technician from the Employment Support Service, along with one of the researchers, disseminated the questionnaire, provided explanations, and assisted participants in completing it. Data collection was carried out between September and October 2021. The data were recorded anonymously so that data protection regulations were respected.

Descriptive statistics are presented as percentages and frequencies. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether the data showed normality. Descriptive statistics and correlation of variables were performed, using Spearman’s Rho to measure the degree of association between two variables. SPSS statistical data analysis software, version 28.0, was used.

Participants voluntarily answered the questionnaire and accepted the informed consent. The questionnaire explained the study topic in detail and included the participant’s consent. Participants’ responses were recorded anonymously, and the information was treated confidentially.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ‘Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects’ contained in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki (amended by the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). It was also approved by the Ethics and Deontological Commission of the Association of University Schools of Labour Relations of Andalusia, whose acceptance was signed on 15 January 2020.

The data collected during the study were processed in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

3.1 Characteristics of the Sample

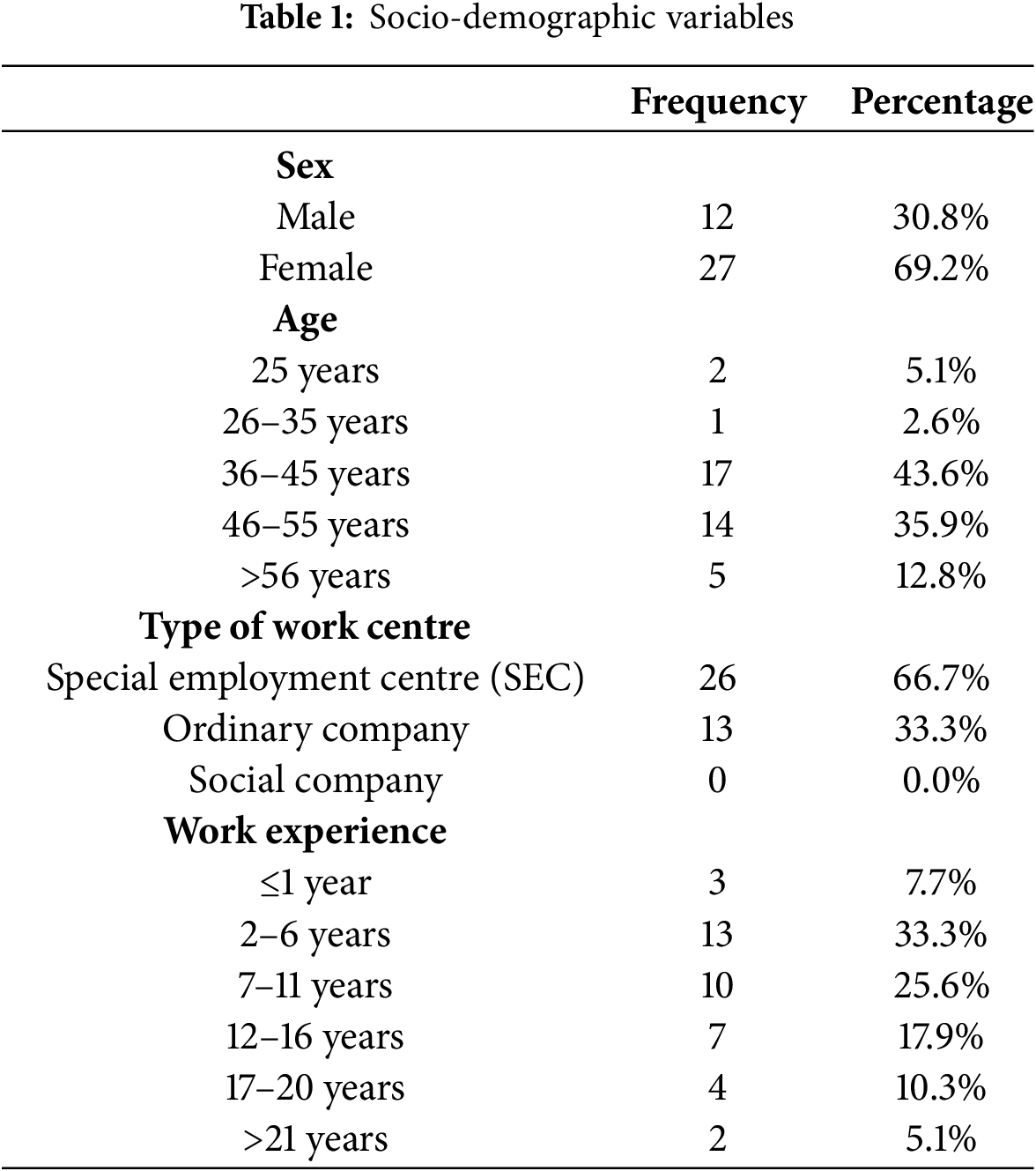

Firstly, socio-demographic data were analyzed: age, sex, work experience, and place of work (Table 1).

Regarding age, 79.5% of the sample was between 36 and 55 years of age, with a minimum age of 25 years and a maximum of 59 years. In addition, there was a greater representation of women 69.2% compared to men, who accounted for 30.8% of the sample. There was also a greater number of workers whose work center was an SEC or social company (66.7%). 13 participants worked in a common company, and no participants were working in a social company.

In terms of years of experience in the labor market, 43.5% of the workers had between 7 and 16 years of experience. In this sense, those with fewer years of experience corresponded to the youngest in age.

3.2 Results of the Job Satisfaction and Perceived Organisational Support Scales

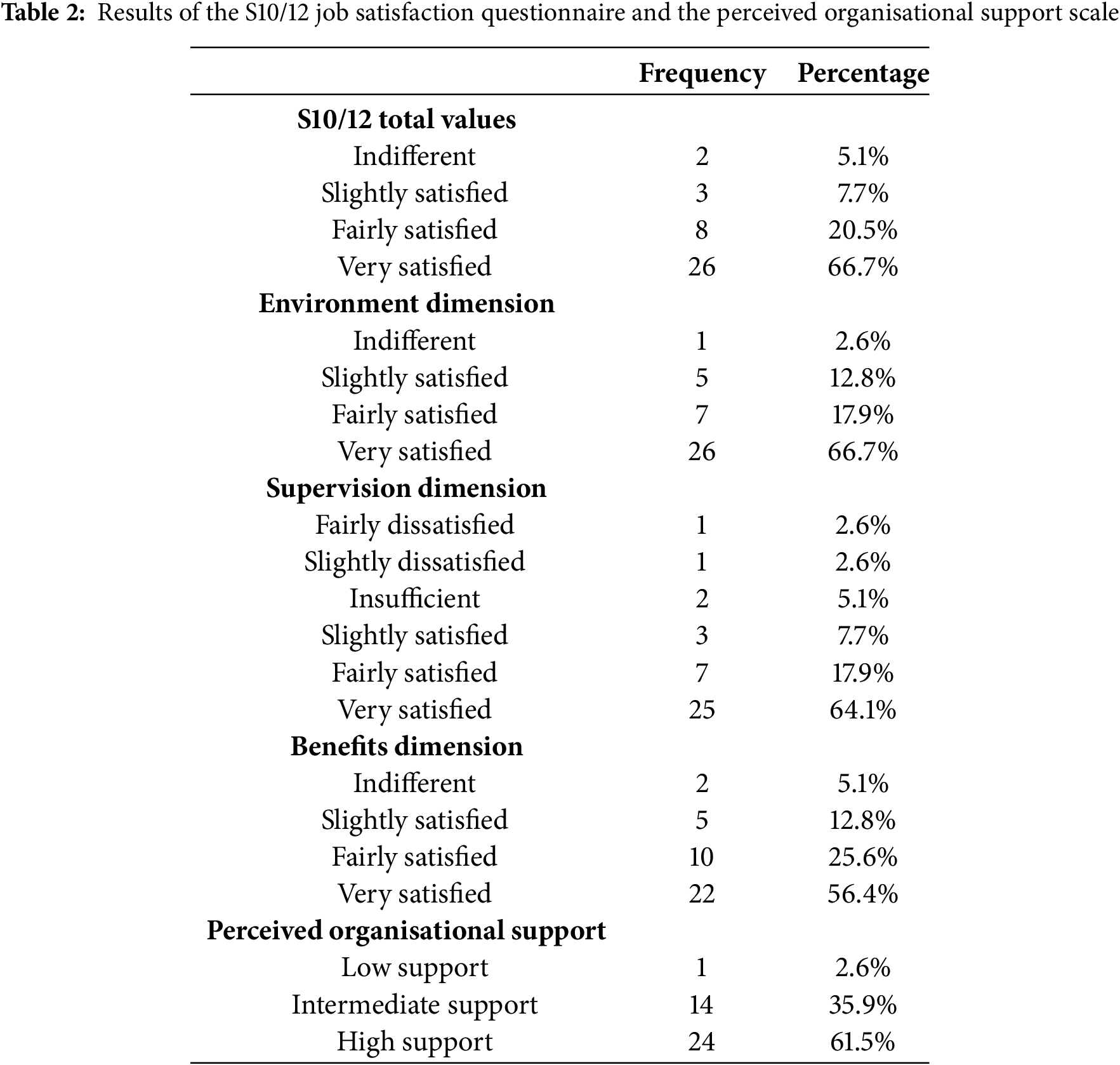

Table 2 shows that 87.2% of the sample showed high levels of job satisfaction. Regarding Perceived Organisational Support, 24 of the 39 (61.5%) respondents perceived high support, and 2.6% perceived little support from the organization.

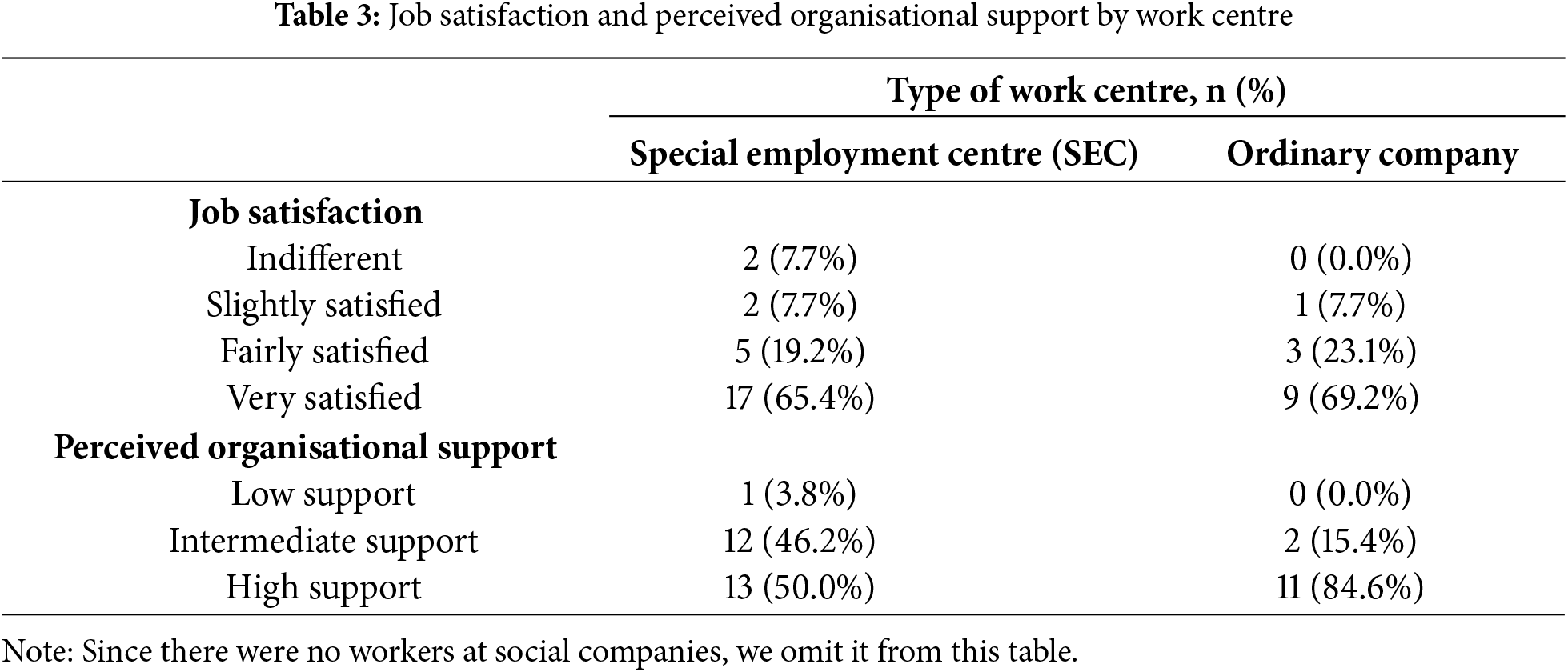

Regarding Job Satisfaction, similar percentages were found for both types of workers, with 65.4% for SEC and 69.2% for ordinary companies being ‘Very Satisfied’. Also, for the Perceived Support variable, 84.6% of the workers from ordinary companies considered that they had sufficient support, and only 50.0% of those from SECs reported the same (Table 3).

3.3 Correlations between Organisational Support and Job Satisfaction

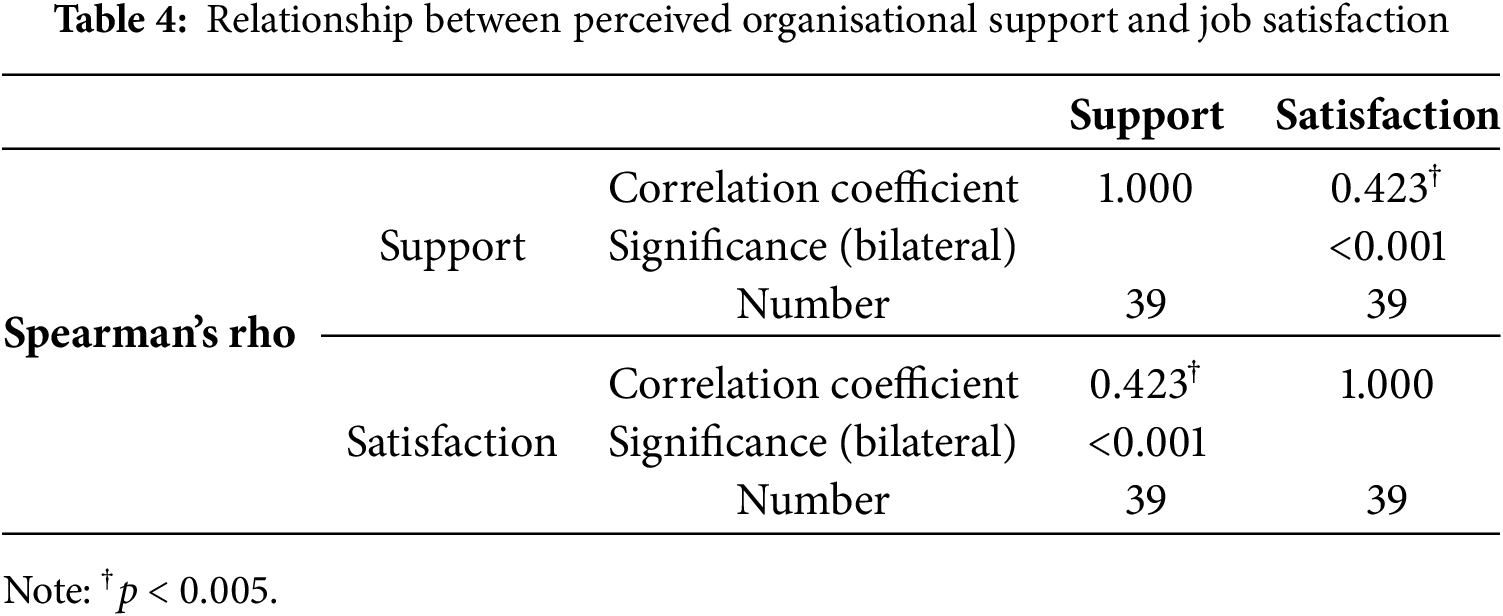

Table 4 shows the relationship between Support and Satisfaction using Spearman’s Rho statistical test. A positive and moderate correlation between these two variables can be observed (Rho = 0.423).

When assessing POS and job satisfaction in workers with SMD, a moderate relationship was found between both variables. This aligns with the theoretical approach of Eisenberg et al. [14], which suggests that organizational support fosters a sense of belonging, thereby increasing job satisfaction. High scores on supervision-related items also support previous research, indicating that employees perceive the company mainly through their supervisors and co-workers. This perception leads to greater satisfaction with supervisors and, consequently, with the company [15].

A pleasant and motivating work environment further enhances job satisfaction, improves mood, and promotes job retention [16]. Companies with a flexible organizational culture—offering adjustments in environment, working conditions, and schedules—can strengthen employees’ perception of support. Feeling supported and confident in seeking help from the organization fosters workplace well-being [17].

Regarding company type, no significant differences were found between individuals working in SECs and those in ordinary companies. In both cases, job satisfaction and perceived support were high. In SECs, this may be due to social and occupational adjustment mechanisms that, even when structured within specific departments, contribute to satisfaction and POS. In ordinary companies, high scores may reflect a commitment to diversity, inclusion, and the employment of individuals with disabilities [18]. This awareness enables job adaptations and ensures support both within and outside the company, facilitating workplace inclusion [19].

Certain factors strongly contribute to job retention. High scores were observed for items such as ‘The company really takes care of my well-being’ and ‘The company is willing to help me’ from the Organisational Support questionnaire. Similarly, items like ‘Support from supervisors’ and ‘Safe spaces to discuss issues’ from the Job Satisfaction questionnaire also scored highly. These findings suggest that company support—embodied by supervisors and adjustment process technicians—enhances satisfaction and, in turn, job retention. Providing a space for workers to express concerns, receive timely interventions, access tailored training, and strengthen social, family, and work relationships further reinforces this sense of satisfaction [20].

This study has certain limitations, primarily due to its small sample size, which restricts the generalisability of the findings and increases the risk of type-II errors. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for tracking changes in job satisfaction and perceived support over time. Future studies should incorporate a longitudinal design and a larger, more diverse sample to validate and expand upon these preliminary findings. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported measures introduces the possibility of response bias, as participants may have provided socially desirable responses. Future research should incorporate objective measures of job performance and organizational support to complement self-reported data.

Despite these limitations, this study serves as a first step in understanding the relationship between perceived support and job satisfaction in workers with severe mental disorders. Future research should build on these findings by including objective measures and longitudinal data collection. Additionally, controlling for confounding variables such as the severity of mental disorders, specific diagnoses, and employment history will help refine the understanding of this relationship.

The findings from this pilot study indicate a positive relationship between perceived organisational support and job satisfaction among workers with severe mental disorders. However, the small sample size and cross-sectional design limit the scope of generalisability. These results serve as a basis for future studies with larger samples and longitudinal designs to better understand the dynamics of job satisfaction and organisational support in this population. Moreover, future research should incorporate objective measures of job performance and organizational support while also considering key variables such as diagnosis type, the severity of the disorder, and employment history to obtain a more nuanced understanding.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: José Antonio Climent-Rodríguez, Yolanda Navarro-Abal; data collection: Inmaculada González-Lepe; analysis and interpretation of results: José Antonio Climent-Rodríguez, Inmaculada González-Lepe, Juan Gómez-Salgado; draft manuscript preparation: Juan Gómez-Salgado, Yolanda Navarro-Abal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Participants voluntarily answered the questionnaire and accepted the informed consent. The questionnaire explained the study topic in detail and included the participant’s consent. Participants’ responses were recorded anonymously, and the information was treated confidentially. The study was conducted in accordance with the ‘Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects’ contained in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki (amended by the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). It was also approved by the Ethics and Deontological Commission of the Association of University Schools of Labour Relations of Andalusia, whose acceptance was signed on 15 January 2020.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shahwan S, Yunjue Z, Satghare P, Vaingankar JA, Maniam Y, Janrius GCM, et al. Employer and co-worker perspectives on hiring and working with people with mental health conditions. Community Ment Health J. 2022;58(7):1252–67. doi:10.1007/s10597-021-00934-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jacob KS. Recovery model of mental illness: a complementary approach to psychiatric care. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(2):117–9. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.155605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Saavedra J, López M, Gonzáles S, Cubero R. Does employment promote recovery? Meanings from work experience in people diagnosed with serious mental illness. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):507–32. doi:10.1007/s11013-015-9481-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Garrido-Cumbrera M, Chacón-García J. Assessing the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on the labor force, employment, and wages of persons with disabilities in Spain. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2018;29(3):178–88. doi:10.1177/1044207318776437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gutierrez-Martínez I, González-Santos J, Rodríguez-Fernández P, Jiménez-Eguizábal A, Del Barrio-Del Campo JA, González-Bernal JJ. Explanatory factors of burnout in a sample of workers with disabilities from the special employment centres (SEC) of the Amica Association, Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):5036. doi:10.3390/ijerph18095036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hall A, Butterworth J, Winsor J, Kramer J, Nye-Lengerman K, Timmons J. Building an evidence-based, holistic approach to advancing integrated employment. Res Pract Pers Sev Disabil. 2018;43(3):207–18. doi:10.1177/1540796918787503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Almalky H. Employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a literature review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;109(3):104656. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hngoi CL, Abdullah NA, Wan SWS, Zaiedy NNI. Examining job involvement and perceived organizational support toward organizational commitment: job insecurity as mediator. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1290122. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1290122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Usadolo QE, Brunetto Y, Nelson S, Gillett P. Connecting the dots: perceived organization support, motive fulfilment, job satisfaction, and affective commitment among volunteers. Sage Open. 2022;12(3):1–13. doi:10.1177/21582440221116111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Eisenberger R, Rhoades SL, Wen X. Perceived organizational support: why caring about employees counts. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2020;7(1):101–24. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sigursteinsdottir H, Karlsdottir FB. Does social support matter in the workplace? Social support, job satisfaction, bullying and harassment in the workplace during COVID-19. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4724. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Meliá JL, Peiró JM. El cuestionario de Satisfacción S10/12: estructura factorial, fiabilidad y validez. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones. 1988;4(11):179–87 (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

13. Ortega V. Adaptación al castellano de la versión abreviada de survey of perceived organizational support. Encuentros En Psicol Soc. 2003;1(1):3–6 (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

14. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–7. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. García-Cabrera AM, Suárez-Ortega SM, Gutiérrez-Pérez FJ, Miranda-Martel MJ. The influence of supervisor supportive behaviors on subordinate job satisfaction: the moderating effect of gender similarity. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1233212. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1233212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhenjing G, Chupradit S, Ku KY, Nassani AA, Haffar M. Impact of employees’ workplace environment on employees’ performance: a multi-mediation model. Front Public Health. 2022;10:890400. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.890400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tsai Y. Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):98. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kwiatkowska-Ciotucha D, Załuska U, Kozyra C, Grześkowiak A, Żurawicka M, Polak K. Diversity of perceptions of disability in the workplace vs. cultural determinants in selected European countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2058. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Coll C, Mignonac K. Perceived organizational support and task performance of employees with disabilities: a need satisfaction and social identity perspectives. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2022;34(10):2039–73. doi:10.1080/09585192.2022.2054284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ellenkamp JJ, Brouwers EP, Embregts PJ, Joosen MC, van Weeghel J. Work environment-related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(1):56–69. doi:10.1007/s10926-015-9586-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools