Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring Subjective Well-Being in Adolescents: The Role of Mental Health and Addictive Behaviors through Machine Learning

1 College of Economics, Hangzhou Dianzi University, Hangzhou, 310018, China

2 School of Economics, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China

3 Physical Education Teaching and Research Office, Xinjiangwan Experimental School Affiliated to Tongji University, Shanghai, 200433, China

4 School of Physical Education, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, 200438, China

5 Centre for Mental Health, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518061, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhuoning Gao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Role of Addictive Behaviors and Psychological Disorders in Shaping Subjective Well-Being)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(5), 667-682. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.062808

Received 28 December 2024; Accepted 12 March 2025; Issue published 05 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Adolescents’ subjective well-being (SWB) is strongly linked to mental health, academic achievement, social relationships, and quality of life, and is a key predictor of life outcomes in adulthood. Mental health and addictive behaviors are the two main factors influencing SWB. This study aimed to identify key mental health and addictive behavior factors associated with adolescent SWB through machine learning models. Methods: The data for this study comes from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey 2017/18. The study data contains health data from 60,450 adolescents aged 10–16 years. The study used the XGBoost machine learning model to analyze the impact of mental health and addictive behaviors on adolescent SWB. Gain was used to analyze the significance of the variables. The direction of action of the variables and the interaction between the variables were analyzed using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method. Results: The model in this study has an accuracy of 86.7% and an AUC value of 0.85, showing its good predictive performance. Six key variables were filtered through Gain analysis. Feeling low and health as the two most important factors affecting SWB, with these two variables contributing 51.38% and 19.65%, respectively. Friends and thinking body as major factors influencing SWB in mental health. Smoking lifetime and sweets as major factors influencing SWB in addictive behaviors. The interactions and characteristic dependencies between these variables were further analyzed. The results showed that feeling low, friends, and sweets had a positive effect on SWB, while health and smoking lifetime showed a negative effect. In addition, a moderate thinking body contributes to SWB, whereas being too fat and too thin are both associated with decreased levels of SWB. Conclusion: Mental health and addictive behavioral factors such as feeling low, friends, sweets, and smoking lifetime were significant factors influencing SWB. This provides a scientific basis for the development of public health policies and interventions aimed at enhancing adolescent well-being.Keywords

The field of research on adolescents’ subjective well-being (SWB) is rapidly expanding. Advances in this area are critical to understanding physical and mental health and personal development across the lifespan [1]. SWB affects not only mental health and academic performance but also social relationships, quality of life, and contributions to society. It has significant predictive value for life outcomes in adulthood [2]. Adolescence is critical stage of personality development when targeted measures can significantly enhance an individual’s SWB [3]. Therefore, it is particularly important to identify the key factors that influence adolescents’ SWB. SWB refers to an individual’s personal perception and experience of quality of life. It encompasses positive and negative emotional responses and satisfaction with all areas of life [4]. The formation of SWB is influenced by a variety of factors, and the complexity of these factors requires in-depth research to better understand its dynamics.

When exploring SWB in adolescents, demographic variables are often considered as a research dimension [5]. Boys tend to have higher SWB than girls [6,7]. The effect of age on SWB shows a trend. As adolescents age, physical and cognitive changes occur, and SWB declines [8]. It is worth noting that health is also an important component of what constitutes SWB, with individuals with higher SWB tending to have better health, and the effect is bidirectional [9,10].

Adolescent mental health is an issue of widespread concern globally as a cornerstone of inner stability and tranquility and is directly related to adolescents’ quality of life and SWB [11]. Research has shown that mental health has a significant positive impact on adolescents’ SWB, with adolescents with better mental health tending to report higher levels of life satisfaction and thus having higher levels of SWB [12]. Individuals with higher levels of mental health are able to maintain higher levels of SWB by making positive cognitive appraisals of social circumstances or life stressors and increasing their ability to control negative emotions. Specifically, feeling low [13], irritability [14], nervousness [15], sleep difficulty [16], pressure [17,18], thinking body [19], and friends [20] are all contributors to SWB. For adolescents, home and school environments, social relationships with parents and peers are particularly important, and these factors significantly influence SWB in these scenarios [21,22]. Good parent-child and peer relationships are important protective factors influencing children’s adjustment and development and an important source of SWB in adolescents [23]. In contrast, factors such as parental and school stress [24], anxiety about schooling [25], sleep deprivation, and body image anxiety [26] may contribute to the ‘hidden psychological costs of education’, which can reduce adolescents’ SWB.

SWB may be significantly and negatively affected by addictive behaviors [27]. Addictive behaviors that are common among adolescents, such as excessive use of social media, smoking, and alcohol consumption, may not only develop into long-term habits but also pose a threat to an individual’s physical health and SWB [28]. For example, with the development of information technology, the large amount of time adolescents invest in social media has made social media addiction a growing concern [29,30]. The effects of adolescent social media use on SWB are complex. Moderate social media use can promote social engagement, peer support, and self-identity. However, chronic overuse can also lead to offline social isolation, increased stress, and an increased tendency to anxiety and depression [31,32]. Addictive behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption [33], drunkenness, cannabis [34], fighting and eating sweets [35] can temporarily release stress. These behaviors stimulate the brain to release dopamine, which brings transient pleasure and elevates mood and SWB. However, prolonged or excessive performance of these behaviors may lead to a decrease in SWB. In particular, smoking and alcohol consumption are often perceived as social activities that enhance social bonding and social support, which in turn increases SWB. However, most addictive behaviors are harmful to physical health in the long term, increasing the risk of disease, impairing cognitive functioning, and in turn, decreasing SWB.

Previous studies on adolescent SWB while providing valuable insights. However, they are mostly limited to examining a single factor in isolation, making it difficult to capture the complex nonlinear interactions among multiple factors. In contrast, machine learning methods can effectively compensate for the shortcomings of traditional methods. It provides a new research perspective for revealing the interaction between multiple factors. In recent years, the application of machine learning in the field of adolescent SWB research has received increasing attention [36,37]. Compared to traditional methods, machine learning not only improves the accuracy of predictions but also enhances the interpretability of models. Machine learning is able to maximize a model’s ability to generalize to new data and optimize prediction accuracy through the division of training and validation sets [38]. Although machine learning models are often viewed as ‘black boxes’, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) provides insight into the contribution of each feature to predicting adolescent SWB, enhancing the interpretability and operationalization of the model [39]. This ability allows us to identify and prioritize influential predictors, leading to more effective implementation of targeted interventions to improve SWB.

Most current studies focus on isolated risk factors and ignore their interdependencies. This study aims to fill the gap in existing research by identifying key mental health and addictive behavioral factors associated with adolescent SWB through machine learning models. Unlike previous studies that have considered risk factors in isolation, this study will consider the interactions between multiple factors and analyze the non-linear effects of each factor on SWB, providing a holistic view of the determinants of SWB. In addition, the insights gained from this study will inform public health policies and targeted interventions aimed at improving SWB in adolescents, ultimately contributing to the improvement of adolescents’ physical and mental health.

2.1 Study Design and Participants

This study adopted a cross-sectional design utilizing data from Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2017/2018 (https://hbsc.org/data/ (accessed on 1 December 2024)) The HBSC is the world’s largest child and adolescent health study conducted every four years in collaboration with WHO. The study focuses on the health, well-being, social environment, and health behaviors of children aged 11, 13, and 15. It is one of the key sources of data for health surveillance. These surveys cover a wide range of topics, including adolescent sexual health, alcohol and drug use, family and friendships, socio-economic environment, health habits, and body image. HBSC researchers obtained institutional ethical approval and informed consent from parents and adolescents in each participating country and participating school [40,41].

The study utilized publicly available, de-identified data from the HBSC, which was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and with appropriate approval from the Institutional Review Board. As a secondary data analysis, this study did not require additional ethical approval, and all analyses were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical standards to ensure data privacy and confidentiality.

In this study, the variables used were assessed based on specific questions in the HBSC questionnaire. The variables cover several dimensions, such as demographic characteristics, mental health status, and addictive behaviors. The information was collected through multiple choice items in the questionnaire. During data processing, the study followed the original coding of the questionnaire to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the findings. The demographic variables were age, gender, health, and sexual intercourse or not. Participants were asked to indicate whether they were a boy (coded 1) or a girl (coded 2), as well as the month and year of their birth. Participants were asked to assess their overall health by choosing from 1 (‘Excellent’) to 4 (‘Poor’). Sexual intercourse was a binary variable coded 1 (‘Yes’) and 2 (‘No’).

The SWB is measured using a modified version of Cantril’s ladder [42], where children rate their current life satisfaction. The ladder has 11 levels, ranging from 0 (‘Worst possible life’) to 10 (‘Best possible life’). The variable was recoded as a dichotomous indicator with thresholds set at low SWB (scores 0–5) and high SWB (scores 6–10) according to the needs of the study [43]. The scale has been used with children and has shown good reliability and good convergent validity on several measures of health and well-being [44].

Mental health is indicated by measuring non-clinical indicators of problematic mental health, and measures of psychopathology and psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, psychosis, etc.) were not included in this study [45]. Part of the Health Behavior Symptom Checklist for School-Aged Children was used in this study, in which students were asked how often they had experienced certain psychological symptoms (feeling low, irritability, nervousness, sleep difficulty, dizziness, and thinking body) in the past 6 months. Each item except the think body was assessed on a 5-point scale from 1 (i.e., ‘about every day’) to 5 (i.e., ‘rarely or never’). Thinking body was assessed from 1 to 5 as ‘Much too thin’, ‘A bit too thin’, ‘About right’, ‘A bit too fat’, and ‘Much too fat’. The checklist has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.74) [40], with retest reliabilities ranging from 0.60 to 0.70 for the individual items [46]. This was supplemented by the addition of two items on stress and reliance on friends (both positively coded).

Addictive behaviors mainly involve smoking, alcohol, cannabis, drunkenness, sweets, fighting, and social media, with participants using specific items to describe their involvement in various types of addictive behaviors [47]. Smoking, alcohol, cannabis, and drunkenness were measured by two constituent measures: ‘In lifetime’ and ‘Last 30 days’, which reflect possible substance addiction, and fighting and social media, which reflect possible behavioral addiction. These items were positively coded. Cronbach’s alpha for this dimension measured 0.78, which is consistent with existing literature (Cronbach alpha = 0.75) [48].

This study used R software (version 4.4.0) for statistical analysis. In this study, machine learning models were used to analyze the impact of mental health and addictive behaviors on adolescent SWB. First, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the participants. Secondly, this study divides the dataset into a training set (70% of the total) and a test set (30% of the total) and the XGBoost model was constructed using the packages “xgboost”, “Matrix”, “caret”, “DALEX”, and “pROC”. This model is particularly suitable for capturing non-linear relationships between variables and their complex interactions. In order to improve the accuracy of the model and prevent overfitting, this study uses a five-fold cross-validation approach aimed at determining the optimal configuration of the learning rate, the depth of the tree, and the number of trees. In this study, the dataset was divided into five different subsets, each containing 20% of the total data volume. Each subset, in turn is used as a test set, while the remaining subsets are used to train the model. To circumvent the potential overfitting problem, the learning rate was set to 0.001 to construct a robust model with low prediction bias and moderate tree size. In this study, the performance of the final model was evaluated using several metrics, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Finally, this study provided a visualization of the importance of the key variables affecting the model predictions, and calculated the SHAP values using the “shapviz” package to further quantify the specific contribution of each feature to the model predictions. By combining various visualization methods from packages such as “ggplot2” and “patchwork”, this study examined in detail the impacts of the key variables on the model and provided insights into their nonlinear effects and interactions on SWB.

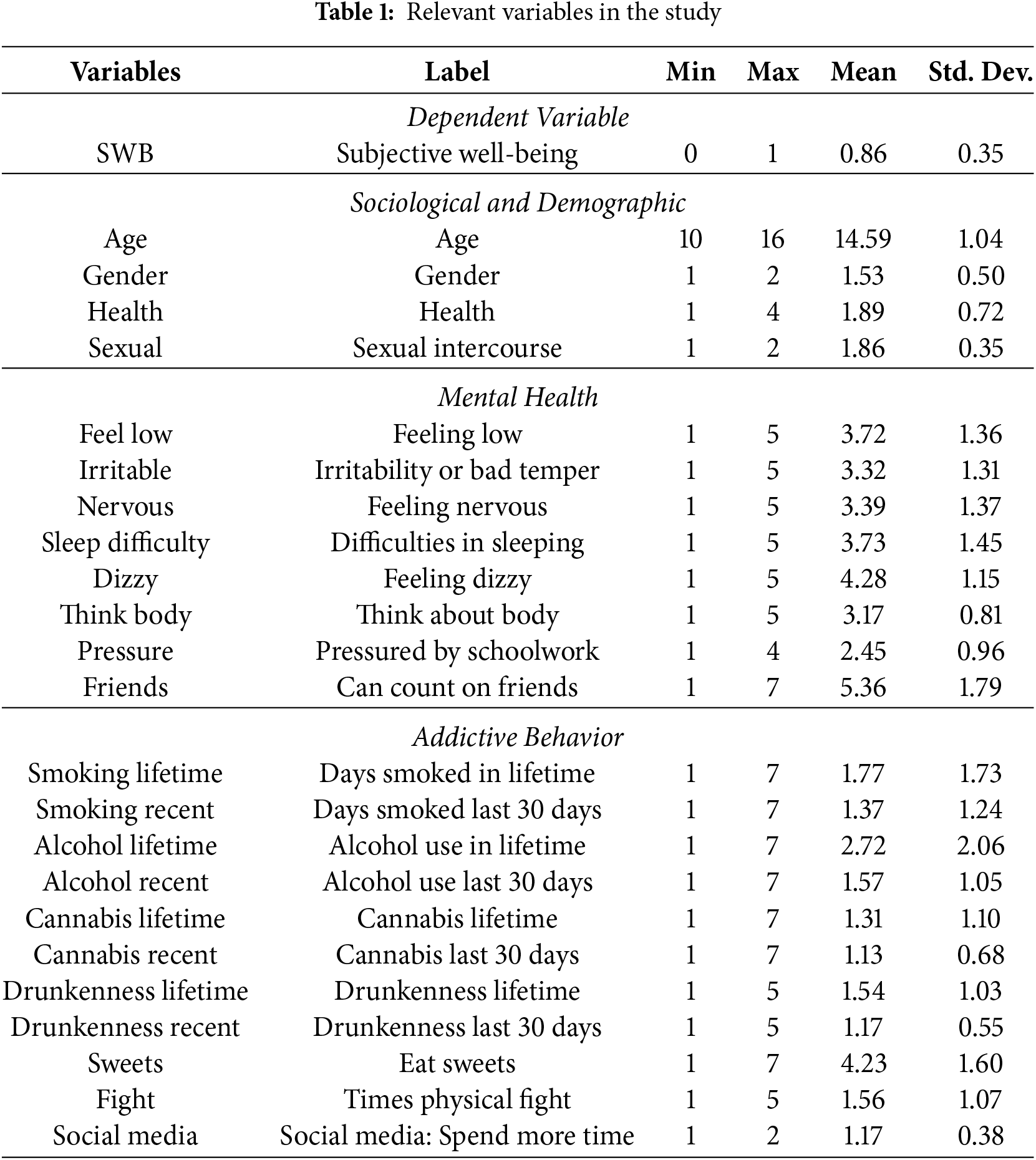

Variables relevant to this study and their descriptions are shown in Table 1.

The results of the descriptive statistics in Table 1 show that these participants were between the ages of 10 and 16. Although the HBSC primarily surveys 11-, 13-, and 15-year- olds, the survey may cover the entire school year when surveyed on a grade-level basis. This may result in participants of other ages being included in the sample. The mean age of the participants was 14.59 ± 1.04. This suggests that the age distribution in the sample was relatively concentrated, mainly between the ages of 13 and 16. In addition, the mean SWB score in the sample was 0.86 ± 0.35. This result suggests that the majority of participants reported high levels of SWB, but it also reflects some inter-individual variability.

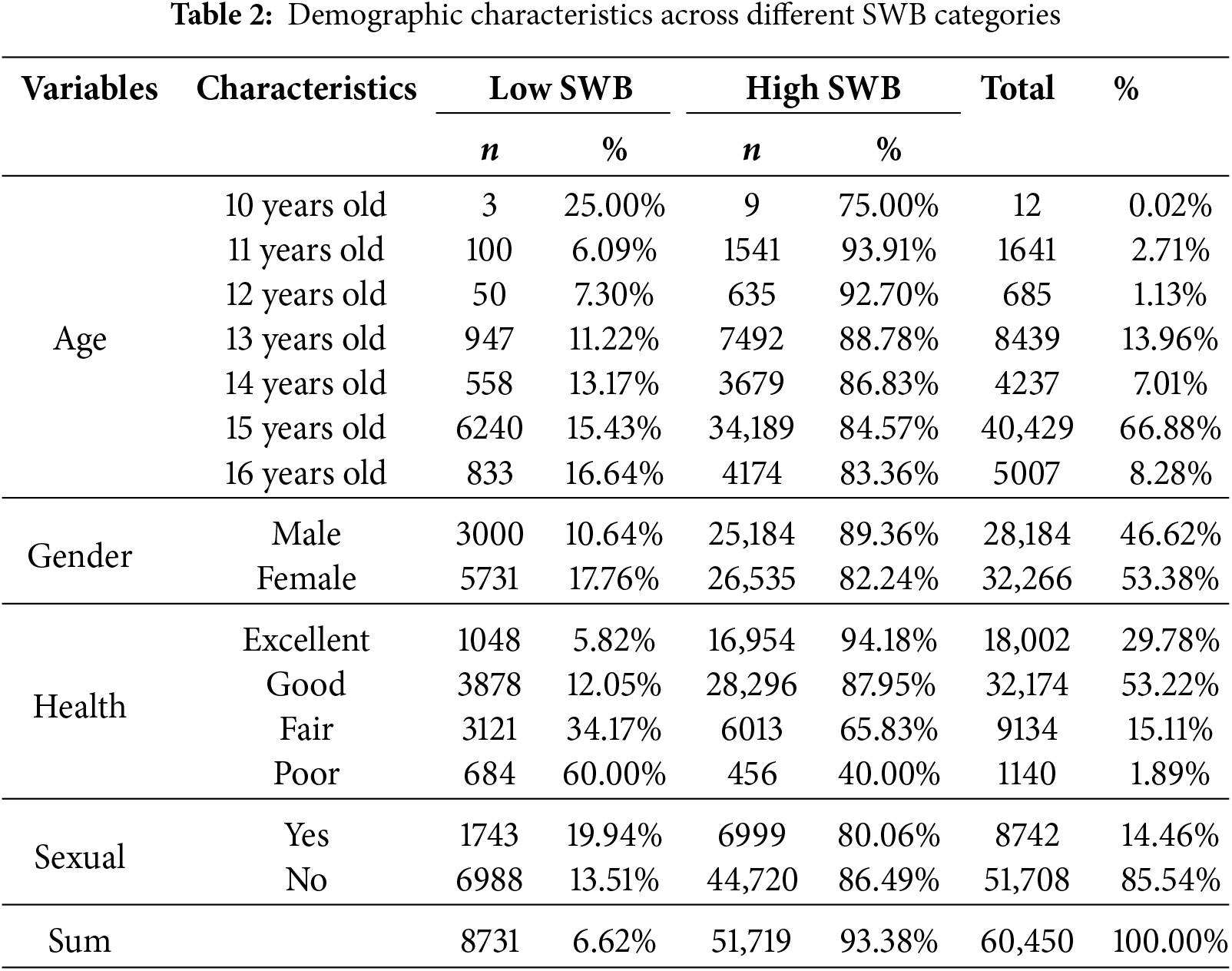

Table 2 provides a descriptive statistical analysis of the study population, revealing the demographic characteristics of the participants under the different SWB categories. The study population was divided into low and high SWB groups based on a range of demographic and behavioral factors. Of the total 60,450 participants, 46.62% were male, and 66.88% were aged 15 years. More than half of the adolescents rated themselves as being in good health, while nearly three-quarters reported no sexual experience. Notably, the vast majority of adolescents (93.38%) exhibited high levels of SWB.

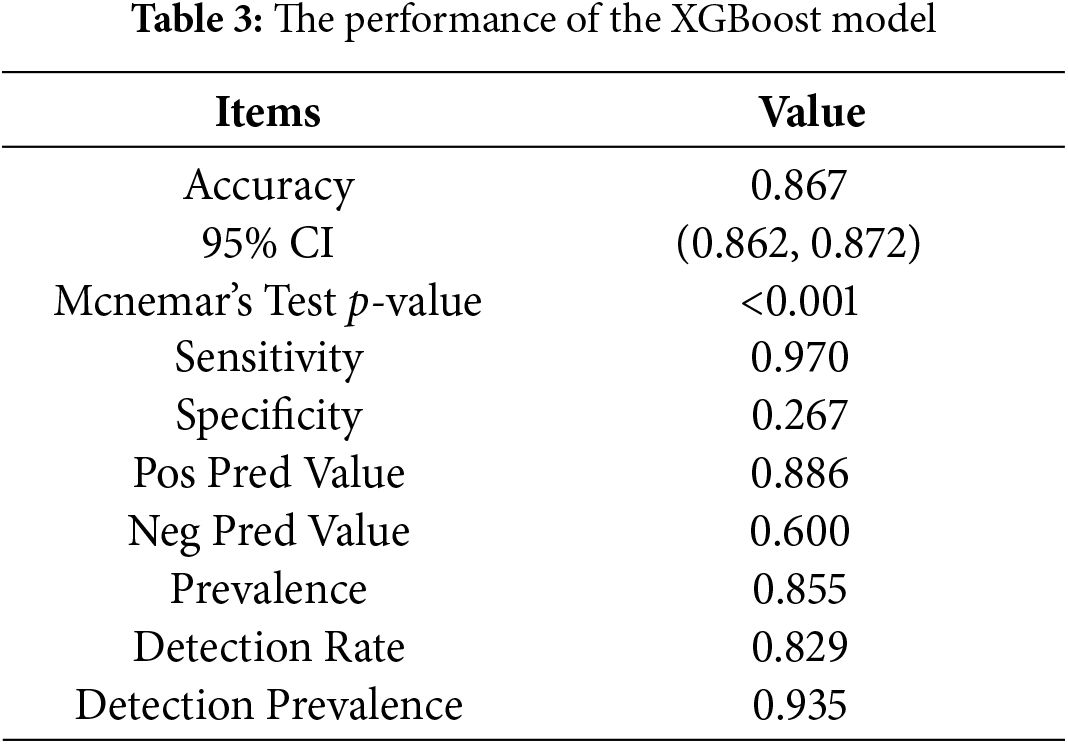

Table 3 shows the performance metrics of the XGBoost model, revealing the accuracy of the model in predicting SWB. The model achieved an accuracy of 86.7%, and the estimated interval of true accuracy was 86.2% to 87.2% at a 95% confidence level. The p-value of Mcnemar’s Test is less than 0.001, indicating that the model is statistically significant in distinguishing between positive and negative samples. In addition, the sensitivity and positive predictive value further confirmed the superior performance of the model. Specifically, the sensitivity was as high as 97.0%, and the positive predictive value was 88.6%, metrics that demonstrate the model’s excellent ability to identify samples with high SWB.

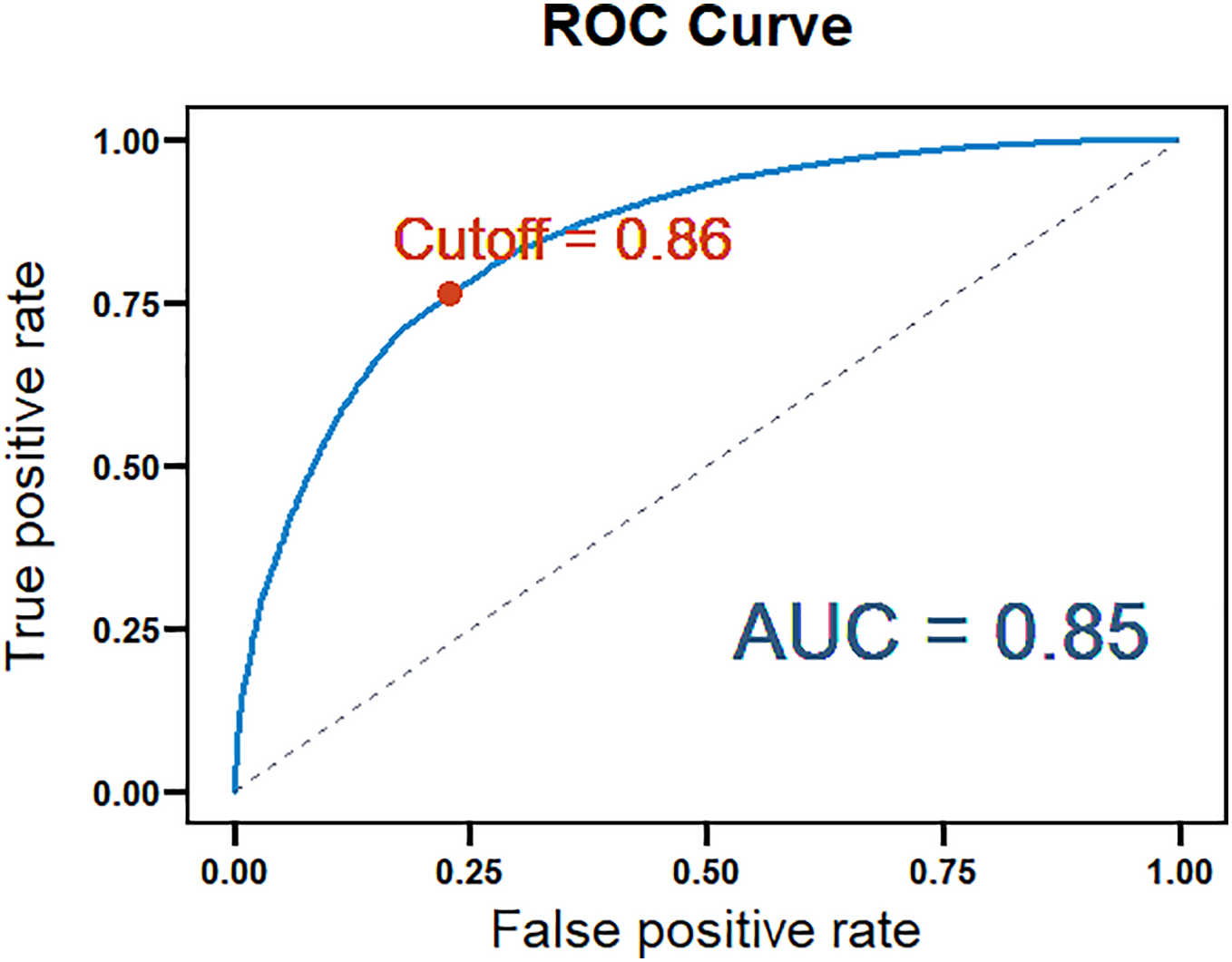

As can be seen from the evaluation curves of the prediction results in Fig. 1, XGBoost achieves a good prediction performance in the task of predicting SWB for teenagers. The closer the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is to the upper left corner, the stronger the model’s prediction is, while XGBoost achieved a good level of 0.85 on the AUC score.

Figure 1: The receiver operating characteristic curve of the XGBoost model

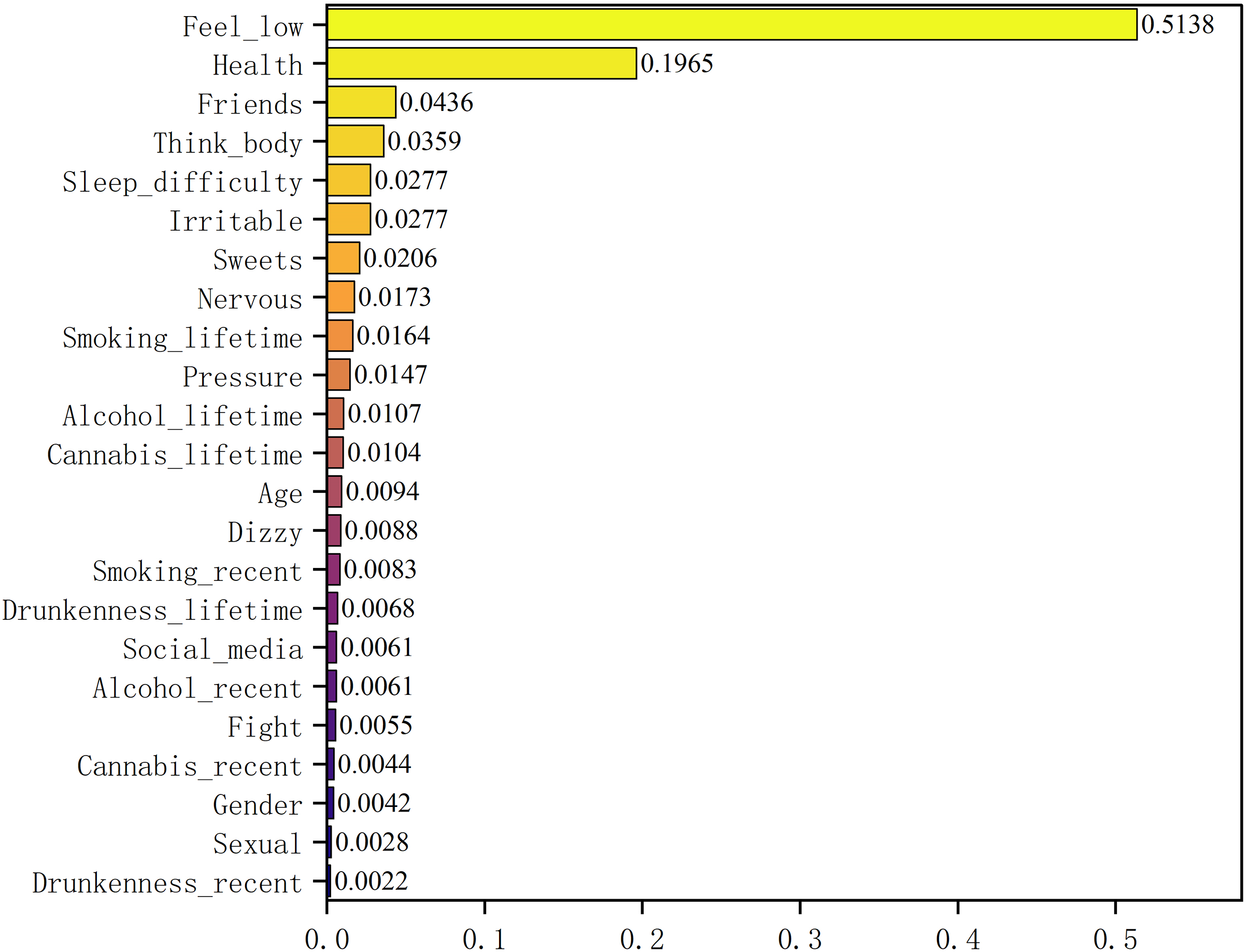

For the XGBoost model, Gain was used to quantify the contribution of each feature to model accuracy during node splitting. The higher the Gain value, the greater the model performance improvement that can be achieved by splitting on that feature. Fig. 2 illustrates the importance of each feature for adolescent SWB. Specifically, feeling low occupies the most important position among these characteristics with a contribution of 51.38%, closely followed by health with a contribution of 19.65%. Friends served as the third most influential factor, while characteristics such as thinking body, sleep difficulty, irritability, sweets, nervousness, smoking lifetime, and pressure also had a predictive effect on the results. Other than that, the cumulative contribution of the other features is relatively low, suggesting that they play a minor role in the model predictions.

Figure 2: Importance ranking of factors influencing adolescent SWB in the XGBoost model

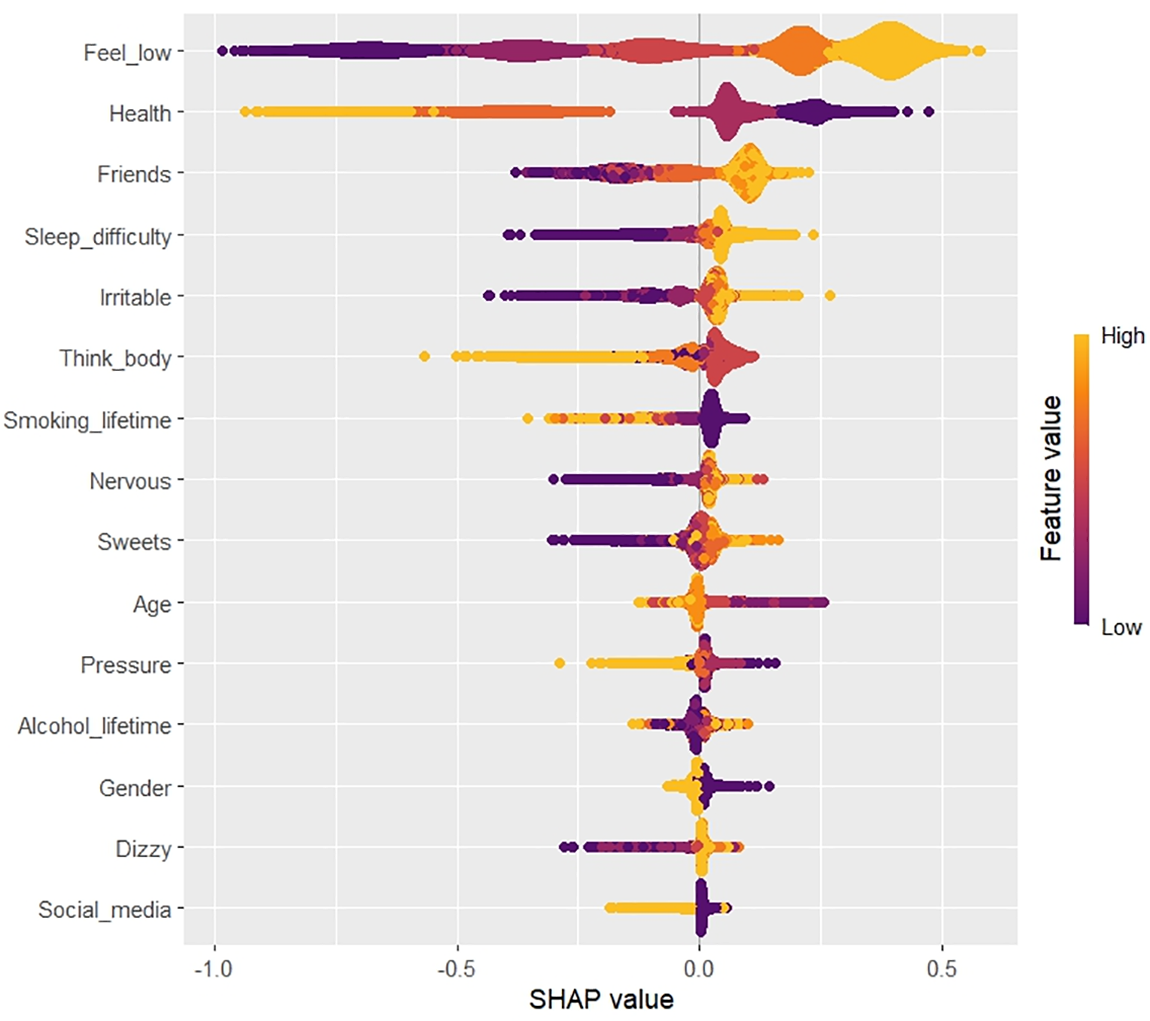

Fig. 3 illustrates the density scatterplot of the top 15 significant features calculated using the SHAP method. In Fig. 3, each scatter represents the SHAP value of a sample, reflecting the feature’s contribution to an individual prediction. The scatter color from purple to yellow indicates the incremental increase in the feature value. The distribution of the scatters then indicates the overall direction and strength of the feature’s influence on the predictions.

Figure 3: Beeswarm plot of factors influencing adolescent SWB in the XGBoost model

As can be seen from Fig. 3, among these 15 features, feeling low is the most important factor affecting the model’s prediction results, and its frequency shows a significant negative effect on the prediction results of SWB. Specifically, the smaller the value of feeling low, the higher the frequency, and the lower its SHAP value, the lower the predicted SWB. Health and friends were the next most important characteristics. The poorer the health of one (the higher the value), the lower the SHAP value and the lower the predicted SWB. The lower the degree to which friends can count (the lower the value), the lower the SHAP value, resulting in a lower predicted SWB. In addition, features such as thinking body, smoking lifetime, age, pressure, gender, and social media were negatively correlated with SWB, implying that an increase in the values of these features was associated with a decrease in SWB in adolescents. In contrast, sleep difficulty, irritability, nervousness, sweets, and dizziness were positively correlated with SWB, suggesting that an increase in the values of these features is associated with an increase in adolescent SWB.

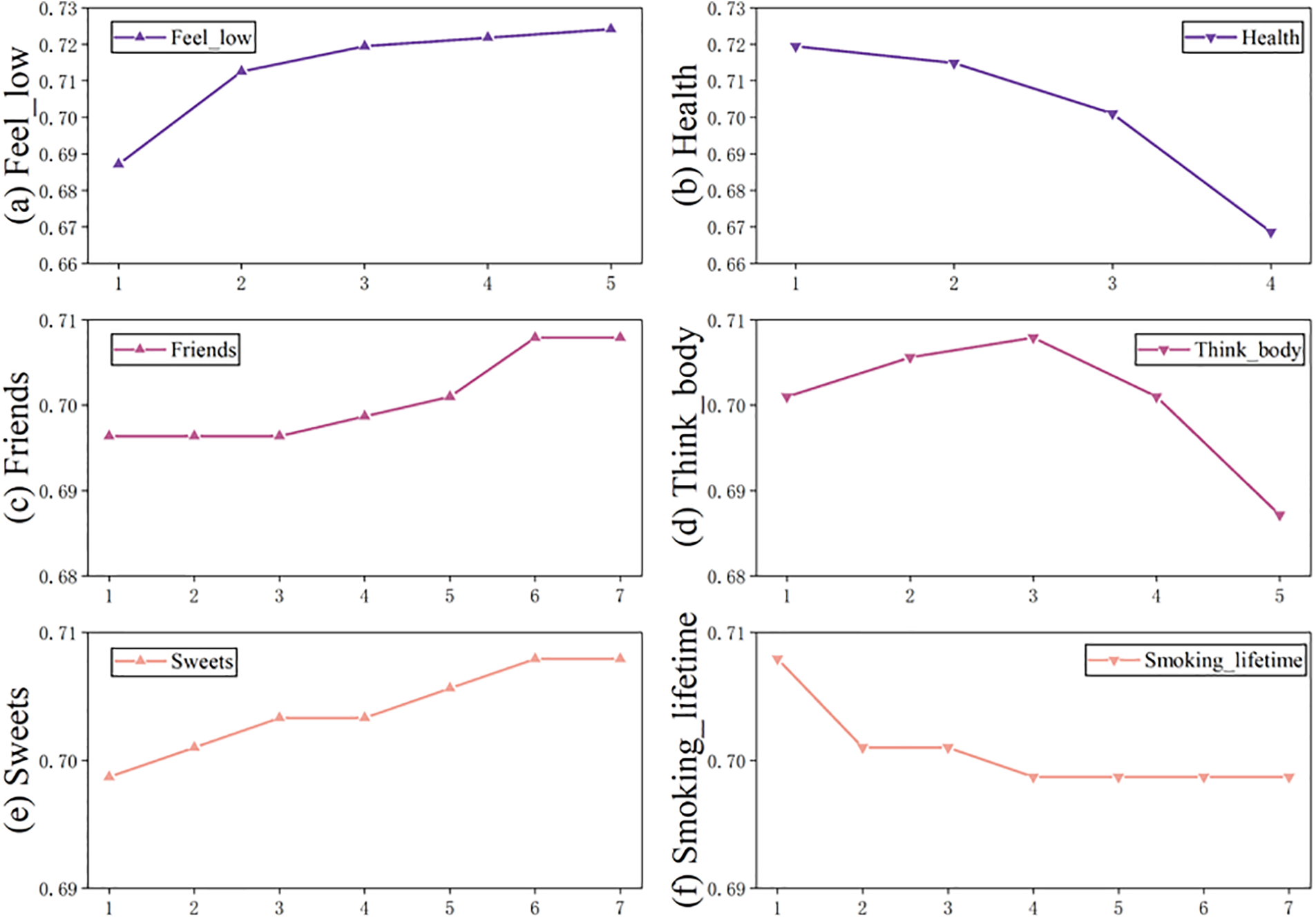

Based on the feature contribution map (Fig. 2), this study selected the two features that have the greatest impact on SWB prediction and the two features that are most critical in mental health and addictive behaviors. These features and the other features with the strongest interactions with them were combined, and the interactions of important features in the XGBoost model were analyzed by visualization. Fig. 4 illustrates the interaction between these features, with each subplot revealing the interrelationship between two features and their joint effect on SHAP values and model predictions. Changes in the horizontal and vertical axes represent changes in the feature values, and the legend indicates the SHAP values of the features.

Figure 4: Interaction effects of important factors in the XGBoost model. (a) Feel low; (b) Health; (c) Friends; (d) Think body; (e) Sweets; (f) Smoking lifetime

In Fig. 4a, this study found that feeling low was the main influencing factor, and the relationship between irritability and SWB was not significant when the level of feeling low was high; however, irritability was positively correlated with SWB when the level of feeling low was low. Fig. 4b shows that improved health has a more significant positive effect on boosting the predicted value of SWB when the level of feeling low is low. Fig. 4c–e all shows that feeling low plays a dominant role when increased friends, moderate thinking body, and sweets are positively associated with SWB. Fig. 4f highlights the important role of friends, on the basis of which there is a negative correlation between smoking lifetime and SWB.

To explore the dependence and non-linear relationship of important features on SWB in the XGBoost model, Fig. 5 illustrates the feature dependency graphs for the six important features in Fig. 4. The horizontal coordinates represent the feature values, while the vertical coordinates map the changes in the model’s predictions. The curves in the figure reflect the trend in the average movement of the predicted results in the sample population as the feature values change.

Figure 5: Partial dependence profile of important factors on adolescent SWB in the XGBoost model. (a) Feel low; (b) Health; (c) Friends; (d) Think body; (e) Sweets; (f) Smoking lifetime

The results of the analyses in Fig. 5 show that the feature values of feeling low, friends, thinking body, and sweets are positively correlated with SWB, while they are negatively correlated with the feature values of health and smoking lifetime. Fig. 5a shows that reducing the frequency of feeling low boosts SWB, but this boosting effect diminishes as the frequency of feeling low decreases. Fig. 5b reveals that deteriorating health is associated with a decrease in SWB, and this negative effect is enhanced with further deterioration in health. Fig. 5c shows that friends have a positive effect on SWB within a certain range. Fig. 5d states that a moderate thinking body has a positive effect on SWB, while an excessive thinking body (too fat or too thin) has a negative effect, especially too fat. Fig. 5e found that moderate consumption of sweets helped to enhance SWB. Fig. 5f shows that an increase in smoking lifetime is associated with a decrease in SWB, but this effect stabilizes after a certain level of increase in smoking lifetime.

In this study, the XGBoost model was used to predict SWB among adolescents, and the model performed well with 86.7% accuracy, effectively differentiating the positive class samples. The ROC curves and the AUC values showed good predictive performance. In order to deeply parse the predictive ability of the model, this study employs Gain and SHAP analyses based on feature contribution to identify the features that most significantly influence SWB. Through this process, six key variables were screened in this study. Feeling low and health, which had the most significant effect on SWB. Friends and thinking body are the main factors affecting SWB in mental health. Smoking lifetime and sweets as the main factors affecting SWB in addictive behaviors. Having identified these key variables, this study further analyzed their interactions and feature dependencies to gain a comprehensive understanding of the predictive mechanisms and outcomes of the model. This comprehensive analysis helped to reveal the complexity of factors affecting adolescent SWB and provided insights into the model’s predictions.

4.1 Sociological and Demographic Factors

The strong positive correlation between health and SWB was further validated in this study [9]. Health positively affects SWB at both the physiological and psychological levels: physiologically, a healthy body provides the necessary energy and hormonal balance; psychologically, it enhances self-efficacy and fosters positive interpersonal relationships, thus contributing to emotional stability [49,50]. Therefore, good health contributes to higher SWB and can counteract some degree of feeling low.

The Sociological and demographic factors, with the exception of health, are also consistent with other literature representations and largely do not have a significant effect on SWB [7]. Age is negatively correlated with SWB, which is consistent with previous studies. This negative correlation may stem from physical and cognitive changes in adolescents, such as increased self-awareness and pubertal development. It is also influenced by increased external social pressures on individuals in this age group, such as stricter school and parental demands [8]. Girls have lower SWB than boys, which is consistent with previous studies [6]. Research has shown that differences in societal role expectations for men and women and gender discrimination, particularly in employment, education, and income, limit girls’ self-worth. Such restrictions increase girls’ anxiety, which in turn affects their self-confidence and SWB. In addition, biological factors, such as hormone levels and structural differences in the brain, may also affect girls’ mood and SWB [1].

Feeling low and SWB exhibit a mirror-image relationship, which has been confirmed in several studies [51,52]. The results of the present study are consistent with the existing literature, which found that adolescents with a higher frequency of feeling low tended to report lower SWB. Feeling low itself can lead to unhappiness, lack of motivation and interest. This reduces satisfaction with life. Feeling low also affects one’s cognitive processes, for example, leading to negative thinking, excessive worrying, and self-depreciation. These can further reduce SWB. The link between feeling low and SWB may go beyond social factors and involve interactions at the biological level, including genetic factors, neurotransmitter systems, and hypothalamic function [53]. In addition, there is a significant genetic association between irritability and feeling low [54], and increased irritability further reduces SWB when feeling low is high.

The lifting effect of friends on SWB was also demonstrated in this study [55]. The support of friends contributes to positive psychosocial adjustments such as lowering depressive symptoms, reducing delinquent and risky behaviors, increasing academic achievement, and counteracting the negative effects of victimization and internalized behaviors [56,57]. However, the role of friends is more effective when the level of feeling is low.

As documented in the existing literature. As adolescents develop during puberty, families and peer groups tend to provide adolescents with information about their appearance and body size. This leads to their perceived pressure from sociocultural sources and vulnerability to others’ comments about their bodies [19]. The results of the present study are consistent with this, in that a moderate thinking body may enhance SWB, but this enhancement is limited when the level of feeling low is high. Being too fat or too thin reduced SWB, with the effects of being overweight being particularly significant.

4.3 Addictive Behavior Factors

The research in this study revealed a positive correlation between sweets and SWB, a finding that contradicts previous findings. The possible explanation lies in children’s natural preference for sweets and the link between sweet consumption and positive emotional experiences [43,58]. This association suggests that the intake of sweets may boost an individual’s SWB in the short term. However, this lifting effect may not be significant at higher levels of feeling low, so it would not be wise to rely on a high intake of sweets to lift SWB in the long term.

The negative correlation between smoking lifetime and SWB was demonstrated in this study [59]. Smoking not only increases negative emotions, triggers health problems, and increases financial burdens, but it can also diminish the positive effects of friends on SWB. In addition, the shared risk factors of smoking and alcohol consumption may cause these two behaviors to occur together, further reducing SWB.

The strength of this study lies in its data sources and analytical methods. The HBSC project provided high-quality data on adolescent mental health, addictive behaviors, and SWB during 2017/2018. As an international study, HBSC ensures the representativeness of the data through a standardized data collection process and extensive sample coverage. These data are able to cover diverse socio-economic and demographic backgrounds, thus enhancing the generalizability and validity of the findings. In addition, this study evaluates SWB using a machine learning approach, which is capable of identifying nonlinear relationships between variables. By dividing the training and validation sets, machine learning is able to avoid overfitting, thus improving the prediction accuracy of the model. At the same time, the interpretability and manipulability of the model are enhanced through the use of methods such as SHAP.

However, there are four main limitations to the data in this study. First, the cross-sectional data provided by the HBSC limited the ability to infer causal relationships, including complex associations such as reverse causation, bi-directionality, and endogeneity. Future research could more accurately identify these relationships through longitudinal data or intervention study designs. Second, the study relied on self-reported data, which could lead to bias. Individuals may overestimate their mental health in order to conform to social expectations. In addition, individuals may also have memory biases. For example, forgetting certain events or exaggerating the negative effects of certain events. Future studies could consider incorporating objective indicators such as physiological sensors to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of physical and mental health. Third, the supervised learning method used in this study relies on predefined labels, which limits the exploration of the underlying structure of the data. Future research could explore unsupervised learning methods to discover new patterns and groups in the data. Finally, the raw international data for the 2021/22 HBSC survey is currently under embargo (until October 2026). This study was unable to access the latest data, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Future studies may use updated data for further validation.

4.5 Public Policy Implications

This study reveals a strong association between adolescents’ mental health and physical health status and their SWB, a finding that emphasizes the importance of promoting positive attitudes and healthy lifestyles among adolescents. Schools and communities should emphasize the emotional well-being of students, teach emotional management skills, and provide opportunities for physical activity enrichment. Friend support and perceptions of body image have a significant impact on adolescents’ mental health and SWB. Therefore, schools should enhance educational activities to increase adolescents’ awareness of body image pressure, promote positive peer relationships, and create an inclusive and diverse school environment. The study also found that moderate intake of sweets helped boost SWB while smoking negatively affected SWB. Based on these findings, the government could develop healthy dietary guidelines to regulate the intake of sweets and strengthen legal restrictions on the purchase of cigarettes by minors.

In this study, key predictors affecting adolescent SWB, including feeling low, friends, sweets, and smoking lifetime, were successfully identified through the application of a machine learning model. These factors are significant predictors and explainers of adolescent SWB in the domains of mental health and addictive behaviors. The results of the study reveal the complex interactions between these variables. The findings of this study highlight the need to develop targeted interventions to enhance adolescent SWB, which should have a particular focus on physical and mental health and addictive behaviors. Using the advanced capabilities of machine learning, the public health field can develop more effective data-driven strategies to enhance SWB in adolescents.

Acknowledgement: HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with WHO/EURO. The International Coordinator of the 2017/18 survey was Dr. Joanna Inchley and the Data Bank Manager was Prof. Oddrun Samdal. For details,see http://www.hbsc.org (accessed on 1 December 2024).

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 24CTJ019).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sitong Chen; methodology, Xingyi Yang; software, Luze Xie; validation, Menghan Bao; formal analysis, Yajing Xu; resources, Xingyi Yang and Zhuoning Gao; writing—original draft preparation, Yajing Xu; writing—review and editing, Luze Xie; visualization, Luze Xie; supervision, Sitong Chen and Zhuoning Gao; funding acquisition, Zhuoning Gao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at http://www.hbsc.org (accessed on 1 December 2024).

Ethics Approval: The study utilized publicly available, de-identified data from the HBSC, which was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and with appropriate approval from the Institutional Review Board. As a secondary data analysis, this study did not require additional ethical approval, and all analyses were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical standards to ensure data privacy and confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ditzel AL, Ketain Meiri Y, Casas F, Ben-Arieh A, Torres-Vallejos J. Satisfaction with the neighborhood of Israeli and Chilean children and its effects on their subjective well-being. Child Indic Res. 2023;16(2):863–95. doi:10.1007/s12187-022-10001-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chu M, Fang Z, Lee CY, Hu YH, Li X, Chen SH, et al. Collaboration between school and home to improve subjective well-being: a new Chinese children’s subjective well-being scale. Child Indic Res. 2023;16(4):1527–52. doi:10.1007/s12187-023-10018-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lawler MJ, Choi C, Yoo J, Lee J, Roh S, Newland LA, et al. Children’s subjective well-being in rural communities of South Korea and the United States. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;85(1):158–64. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1984;95(3):542–75. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Goswami H. Children’s subjective well-being: socio-demographic characteristics and personality. Child Indic Res. 2014;7(1):119–40. doi:10.1007/s12187-013-9205-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. dos Santos BR, Sarriera JC, Bedin LM. Subjective well-being, life satisfaction and interpersonal relationships associated to socio-demographic and contextual variables. Appl Res Qual Life. 2019;14(3):819–35. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9611-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Moreira AL, Yunes MAM, Martins LF. Children’s subjective well-being and the protective role of friendships, school satisfaction and neighborhood in the face of peer victimization. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;155(2):107177. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xie QW, Luo X, Lu S, Fan XL, Li S. Household income mobility and adolescent subjective well-being in China: analyzing the mechanisms of influence. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2024;164(4):107882. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Diener E, Pressman SD, Hunter J, Delgadillo-Chase D. If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2017;9(2):133–67. doi:10.1111/aphw.12090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mathentamo Q, Lawana N, Hlafa B. Interrelationship between subjective wellbeing and health. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2213. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19676-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Yun L, Mao Z. Psychological security, financial market participation, and residents’ subjective well-being: an empirical analysis based on CFPS data. Int Rev Econ Finance. 2025;97(10410):103744. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2024.103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pongutta S, Vithayarungruangsri J. Subjective well-being of Thai pre-teen children: individual, family, and school determinants. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15927. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang N, Liu C, Chen Z, An L, Ren D, Yuan F, et al. Prediction of adolescent subjective well-being: a machine learning approach. Gen Psychiatr. 2019;32(5):e100096. doi:10.1136/gpsych-2019-100096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang L, Yao B, Zhang X, Xu H. Effects of irritability of the youth on subjective well-being: mediating effect of coping styles. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49(10):1848–56. doi:10.18502/ijph.v49i10.4685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Luo YF, Shen HY, Yang SC, Chen LC. The relationships among anxiety, subjective well-being, media consumption, and safety-seeking behaviors during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13189. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lenneis A, Das-Friebel A, Tang NKY, Sanborn AN, Lemola S, Singmann H, et al. The influence of sleep on subjective well-being: an experience sampling study. Emotion. 2024;24(2):451–64. doi:10.1037/emo0001268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kleinkorres R, Stang-Rabrig J, McElvany N. Comparing parental and school pressure in terms of their relations with students’ well-being. Learn Individ Differ. 2023;104(2):102288. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu T, Liu L, Chen Z, Fu R. Study on influencing factors of mental health of mobile young white-collar workers in China. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(2):127–38. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.045071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xiang G, Teng Z, Yang L, He Y. Longitudinal relationships among sociocultural pressure for body image, self-concept clarity, and emotional well-being in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2024;96(1):98–111. doi:10.1002/jad.12257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang L, Cheng Y, Jiang S, Zhou Z. Neighborhood quality and subjective well-being among children: a moderated mediation model of out-of-school activities and friendship quality. Child Indic Res. 2023;16(4):1607–26. doi:10.1007/s12187-023-10024-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Knies G. Effects of income and material deprivation on children’s life satisfaction: evidence from longitudinal data for England (2009–2018). J Happiness Stud. 2022;23(4):1469–92. doi:10.1007/s10902-021-00457-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Marquez J, Main G. Can schools and education policy make children happier? A comparative study in 33 countries. Child Indic Res. 2021;14(1):283–339. doi:10.1007/s12187-020-09758-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li W, Song Y, Zhou Z, Gu C, Wang B. Parents’ responses and children’s subjective well-being: the role of parent-child relationship and friendship quality. Sustainability. 2024;16(4):1446. doi:10.3390/su16041446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Boer M, Cosma A, Twenge JM, Inchley J, Jeriček Klanšček H, Stevens GM. National-level schoolwork pressure, family structure, Internet use, and obesity as drivers of time trends in adolescent psychological complaints between 2002 and 2018. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(10):2061–77. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01800-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Steinmayr R, Crede J, McElvany N, Wirthwein L. Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: testing for reciprocal effects. Front Psychol. 2016;6(52):1994. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Eryılmaz A, Kara A, Huebner ES. The mediating roles of subjective well-being increasing strategies and emotional autonomy between adolescents’ body image and subjective well-being. Appl Res Qual Life. 2023;18(4):1645–71. doi:10.1007/s11482-023-10156-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Khasmohammadi M, Ghazizadeh Ehsaei S, Vanderplasschen W, Dortaj F, Farahbakhsh K, Keshavarz Afshar H, et al. The impact of addictive behaviors on adolescents psychological well-being: the mediating effect of perceived peer support. J Genet Psychol. 2020;181(2–3):39–53. doi:10.1080/00221325.2019.1700896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Atroszko PA, Atroszko B, Charzyńska E. Subpopulations of addictive behaviors in different sample types and their relationships with gender, personality, and well-being: latent profile vs. latent class analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8590. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Yang J. The cumulative effect of multi-contextual risk on problematic social media use in adolescents. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(25):21919–30. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-06003-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu T, Shi H, Chen C, Fu R. A study on the influence of social media use on psychological anxiety among young women. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(3):199–209. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.046303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Malone C, Wachholtz A. The relationship of anxiety and depression to subjective well-being in a mainland Chinese sample. J Relig Health. 2018;57(1):266–78. doi:10.1007/s10943-017-0447-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Popat A, Tarrant C. Exploring adolescents’ perspectives on social media and mental health and well-being—A qualitative literature review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;28(1):323–37. doi:10.1177/13591045221092884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Brook DW, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Morojele NK, Brook JS. Environmental stressors, low well-being, smoking, and alcohol use among South African adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(9):1447–53. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tartaglia S, Miglietta A, Gattino S. Life satisfaction and cannabis use: a study on young adults. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(3):709–18. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9742-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chang HH, Nayga RM. Childhood obesity and unhappiness: the influence of soft drinks and fast food consumption. J Happiness Stud. 2010;11(3):261–75. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9139-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Britton Ú, Onibonoje O, Belton S, Behan S, Peers C, Issartel J, et al. Moving well-being well: using machine learning to explore the relationship between physical literacy and well-being in children. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2023;15(3):1110–29. doi:10.1111/aphw.12429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Meng H, He S, Guo J, Wang H, Tang X. Applying machine learning to understand the role of social-emotional skills on subjective well-being and physical health. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2025;17(1):e12624. doi:10.1111/aphw.12624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. King RB, Wang Y, Fu L, Leung SO. Identifying the top predictors of student well-being across cultures using machine learning and conventional statistics. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8376. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55461-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Andrew Rothenberg W, Bizzego A, Esposito G, Lansford JE, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D, et al. Predicting adolescent mental health outcomes across cultures: a machine learning approach. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(8):1595–619. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01767-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mojtabai R. Problematic social media use and psychological symptoms in adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;59(12):2271–8. doi:10.1007/s00127-024-02657-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Moor I, Winter K, Bilz L, Bucksch J, Finne E, John N, et al. The 2017/18 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study—Methodology of the World Health Organization’s child and adolescent health study. J Health Monit. 2020;5(3):88–102. doi:10.25646/6904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ, USA: Rutgers University Press; 1965. 456 p. [Google Scholar]

43. Jonsson KR, Bailey CK, Corell M, Löfstedt P, Adjei NK. Associations between dietary behaviours and the mental and physical well-being of Swedish adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2024;18(1):43. doi:10.1186/s13034-024-00733-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Corell M, Friberg P, Petzold M, Löfstedt P. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent mental health in the Nordic countries in the 2000s—A study using cross-sectional data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Arch Public Health. 2024;82(1):20. doi:10.1186/s13690-024-01240-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Eriksson C, Stattin H. Mental health profiles of 15-year-old adolescents in the Nordic countries from 2002 to 2022: person-oriented analyses. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2358. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19822-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Melkevik OR, Torsheim T, Samdal O, Hetland J, et al. Gaming addiction, gaming engagement, and psychological health complaints among Norwegian adolescents. Medium Psychol. 2013;16(1):115–28. doi:10.1080/15213269.2012.756374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bartlett S, Bataineh J, Thompson W, Pickett W. Correlations between weight perception and overt risk-taking among Canadian adolescents. Can J Public Health. 2023;114(6):1019–28. doi:10.17269/s41997-023-00778-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. King N, Davison CM, Pickett W. Development of a dual-factor measure of adolescent mental health: an analysis of cross-sectional data from the 2014 Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e041489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Liu N, Zhong Q. The impact of sports participation on individuals’ subjective well-being: the mediating role of class identity and health. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2023;10(1):544. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-02064-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ngamaba KH, Panagioti M, Armitage CJ. How strongly related are health status and subjective well-being? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(5):879–85. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckx081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Cheng H, Furnham A. Personality, self-esteem, and demographic predictions of happiness and depression. Pers Individ Differ. 2003;34(6):921–42. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00078-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Schlechter P, Katenhusen S, Morina N. The relationship of aversive and appetitive appearance-related comparisons with depression, well-being, and self-esteem: a response surface analysis. Cogn Ther Res. 2023;47(4):621–36. doi:10.1007/s10608-023-10369-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Gargiulo RA, Stokes MA. Subjective well-being as an indicator for clinical depression. Soc Indic Res. 2009;92(3):517–27. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9301-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Vidal-Ribas P, Stringaris A. How and why are irritability and depression linked? Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2021;30(2):401–14. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2020.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Y, King R, Leung SO. Understanding Chinese students’ well-being: a machine learning study. Child Indic Res. 2023;16(2):581–616. doi:10.1007/s12187-022-09997-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Güroğlu B. The power of friendship: the developmental significance of friendships from a neuroscience perspective. Child Dev Perspectives. 2022;16(2):110–7. doi:10.1111/cdep.12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Fu R, Xie L. Do public health events promote the prevalence of adjustment disorder in college students? An example from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(1):21–30. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.041730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Otake K, Kato K. Subjective happiness and emotional responsiveness to food stimuli. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(3):691–708. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9747-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Altwicker-Hámori S, Ackermann KA, Furchheim P, Dratva J, Truninger D, Müller S, et al. Risk factors for smoking in adolescence: evidence from a cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1165. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-18695-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools