Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Orthorexia Nervosa Risk, Body Image Perception, and Associated Predictors Among Adolescent Football Players from Poland and Türkiye

1 Department of Food Technology and Quality Evaluation, Faculty of Public Health in Bytom, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Zabrze, 41-808, Poland

2 Department of Training Education, Faculty of Sports Science, Batman University, Batman, 72000, Türkiye

3 Department of Sport Nutrition, Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Katowice, 40-065, Poland

4 Department of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, Department of Dietetics, Faculty of Public Health in Bytom, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Zabrze, 41-808, Poland

* Corresponding Author: Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(5), 649-665. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.064543

Received 18 February 2025; Accepted 30 April 2025; Issue published 05 June 2025

Abstract

Background: In light of growing concern over eating disorders among young athletes amid cultural and social pressures, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa (ON) risk and evaluate body image perception and its predictive factors among young football players from Poland and Türkiye. Methods: The study involved 171 players aged 15–18 years, recruited from football academies in Poland and Türkiye. The Polish and Turkish versions of the Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA) were administered to assess body image perception, while the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS) was used to measure ON risk. Anthropometric measurements were taken to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI), which was then referenced to centile charts to determine nutritional status. Results: Results indicated that 13% of participants exhibited characteristics of ON, with an additional 26% classified as at elevated risk. Comparative analysis revealed no significant differences in ON prevalence between Polish and Turkish players (p = 0.938) and no age-related differences (p = 0.694). Among Polish players, a significant positive association emerged between BMI (relative to centile charts) and overall appearance evaluation (BE-Appearance) (p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.10). This relationship was not observed in Turkish players. Moreover, analysis of ON risk predictors—including age, nationality, nutritional status, and body image—did not identify any single variable as a definitive predictor (all p-values > 0.05), with a low predictive capacity (McFadden’s R2 = 0.03). Conclusion: The study revealed a significant risk of ON among young footballers with no clear predictors.Keywords

Body self-esteem is widely recognized as a crucial factor in psychosocial adjustment, yet recent studies suggest that increasing numbers of individuals—particularly adolescents—are dissatisfied with their appearance [1]. Although dissatisfaction can manifest in both genders, the specific concerns often differ: women commonly aspire to reduce body weight, while men may be more focused on increasing muscularity [2]. These gender-based patterns are important to consider, as body image concerns can emerge as early as six years of age, intensifying significantly during adolescence—a developmental stage marked by rapid physical and psychological changes [3]. In general, body self-esteem refers to how individuals perceive, evaluate, and feel about their own appearance [4].

Several instruments have been developed to assess body self-esteem in different populations. One widely used tool is the Body-Esteem Scale (BES) [5], which measures attitudes toward one’s body. However, references to sexual aspects in the BES limit its applicability among younger populations. As an alternative, the Body Self-Assessment Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA) was introduced to capture three dimensions of body self-esteem: appearance, weight, and attributed evaluation (i.e., how individuals believe others perceive them) [6]. Research has shown that lower body self-esteem can amplify perfectionistic tendencies in both dietary habits and exercise patterns [5,6]. This interplay between body image and health behaviors may place adolescents at risk for disordered eating.

Among various forms of disordered eating, orthorexia nervosa (ON) has recently gained attention. ON is characterized by an excessive, pathological preoccupation with consuming only foods deemed “healthy” or “pure” [7]. Over time, this rigid focus on food quality—often at the expense of quantity—may lead to nutritional deficiencies, malnutrition, and a reduced quality of life. Although ON is not formally recognized in major diagnostic manuals such as the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [8,9], it is frequently discussed in clinical practice under Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED) or conceptualized as a culturally influenced variant of anorexia nervosa (AN) [10]. Scholars continue to debate whether ON represents a distinct disorder or a precursor to, or subtype of, more established eating disorders (EDs) such as anorexia or bulimia. Understanding whether ON predisposes individuals to other EDs is crucial, especially in adolescence when unhealthy habits can become entrenched.

Beyond gender differences, the context of athletic participation adds another layer of complexity to disordered eating behaviors. Being an athlete, particularly in sports like football that emphasize specific fitness and performance goals, can heighten body image pressures [11]. The interplay of intense training schedules, performance expectations from coaches and peers, and constant self-monitoring of body weight or shape can create an environment in which restrictive or obsessive eating behaviors are more likely [7,12]. Adolescent football players, who are simultaneously navigating physical maturation and the development of personal identity, may be especially vulnerable to these pressures [13,14].

Recent findings suggest that approximately 40% of Polish elite footballers may be at risk for ON, although these athletes also report moderate to high body self-esteem across various subscales [15]. This apparent paradox—whereby players exhibit relatively positive self-evaluations yet remain susceptible to disordered eating—indicates that self-reported body image might not be the sole predictor of ON. Another study found significant differences in body self-esteem between professional and amateur players, suggesting that performance level and associated pressures can also shape athletes’ perceptions of their bodies [16].

Cultural and social factors further complicate these dynamics, as societal norms regarding attractiveness and acceptable body shapes can vary widely [17]. While Western societies often prioritize thinness or leanness, non-Western contexts may hold different ideals [18]. Indeed, the prevalence and manifestation of EDs, including ON, are increasingly recognized in non-Western populations, challenging the notion that these conditions are uniquely Western phenomena [19–21]. Consequently, the need for culturally sensitive tools and analyses has become more pressing [22]. For example, a study of female athletes from Poland and Türkiye showed that dissatisfaction with one’s body significantly heightened ON risk, with Polish participants more frequently exhibiting risk or presence of ON than their Turkish counterparts [23]. Such findings underscore the importance of examining sociocultural variables when assessing EDs in athletes.

Negative body image has long been identified as a risk factor for the development of EDs, especially in performance-oriented environments [24,25]. Athletes may adopt restrictive diets, compulsive exercise routines, or rigid food rules in pursuit of ideal weight or shape [25,26]. Moreover, the sociocultural backdrop can either reinforce or mitigate these pressures. For instance, cultural norms that valorize muscular physiques might place greater emphasis on weight gain (in the form of muscle) rather than weight loss, thus altering the trajectory of disordered eating behaviors [26].

Given these considerations, the present study aims to (1) determine the prevalence of ON risk among adolescent football players from Poland and Türkiye, (2) compare body image indicators in both groups, and (3) explore how age and nationality may shape the relationship between nutritional status and body image perception. We also seek to identify predictors of ON risk, focusing on variables such as age, nationality, and body self-esteem dimensions.

Based on the foregoing considerations and literature review, the following research hypotheses were formulated. First, adolescent football players from Poland and Türkiye exhibit a significant risk of developing ON, with a similar prevalence expected between the two countries. Furthermore, a negative body image—particularly dissatisfaction with one’s appearance or body weight—is associated with an elevated risk of ON among these athletes. Finally, demographic factors (such as age), cultural factors (such as nationality), and nutritional status (as indicated by BMI) are expected to significantly influence the occurrence of ON and serve as potential predictors in the studied group.

The study was conducted between December 2024 and January 2025 using a survey-based methodology. The participants comprised Polish and Turkish players from elite football academies. The players completed the questionnaire before training, and they received instructions to ensure proper understanding and interpretation of the questions, thereby minimizing response errors. The participants accessed the survey questionnaire by scanning a QR code. Data collection was facilitated through Google Forms due to its ease of use, accessibility, and adaptability to the specific needs of the study. The average time required to complete the questionnaire was approximately 20 min.

The sample size was estimated using the minimum sample size formula. In calculating the sample size, the number of players in the participating football academies was taken into account, including each player’s year of birth. This ensured that a representative group of study participants was obtained. The following formula was used in the study:

where, Nmin is minimum sample size, Np is population size, α is confidence level, f is fraction size, and e is assumed maximum error.

Based on the data obtained from the academies regarding the number of players, the minimum sample size was estimated. It was assumed that there were 100 football players in the U15–U18 groups at each of the Polish and Turkish academies. Under a 95% confidence level, a fraction of 0.9, and a maximum margin of error of 5%, the minimum required sample size for Polish and Turkish football players was 82 for each nationality.

All participants and their legal guardians were thoroughly informed about the study’s purpose and assured of their anonymity, with consent obtained for data usage. Details regarding the voluntary and informed nature of participation were provided to legal guardians prior to the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Silesian Medical University in Katowice (protocol code BNW/NWN/0052/KB/229/23 and date of approval: 25 October 2023), in accordance with the Act of 5 December 1996, regulating the professions of physicians and dentists (Journal of Laws 2016, item 727). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

The study included 171 football academy players from the U15–U18 age groups competing in an elite youth league. The participants were recruited from two sports academies: one in Poland (n = 86) and one in Türkiye (n = 85). They learned about the study through their coaches, who, together with the researchers, provided detailed information during a dedicated meeting held with the players and their legal guardians. This meeting clarified the study’s purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature, and ensured that both the athletes and their guardians fully understood the data collection process and confidentiality measures. Based on nationality, the players were divided into two groups—Polish football players (PL) and Turkish football players (TR)—and were further categorized into four age groups: 15, 16, 17, and 18 years old.

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (1) male sex, justified by the study’s focus on a specific athletic population, (2) consent from the academy to participate in the study, (3) voluntary participation with legal guardian consent, (4) age between 15 and 18 years, (5) attendance in at least 80% of training sessions over the past year, and (6) absence of any injury causing a training interruption of at least seven days within the last two months. The exclusion criteria included: (1) lack of consent from the participant or legal guardian, and (2) an incorrectly or incompletely filled-out questionnaire.

The decision to include only male participants was made due to the physiological, psychological, and developmental differences that occur between males and females during adolescence. Additionally, football as a discipline presents specific physiological and tactical demands that differ between male and female athletes, particularly in competitive settings. Therefore, to ensure the homogeneity of the study sample and accurately assess the variables of interest related to ON and body image perception within adolescent male football players, only male participants were included.

The study employed a structured questionnaire that included a demographic section aimed at gathering participants’ background information. This section collected details such as age, existing chronic illnesses, current medications, football playing position, and the frequency of additional training sessions conducted outside the academy and school environment. Moreover, two standardized assessment instruments were utilized in the study: the Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA) and the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS).

Body mass and height were measured before completing the questionnaire. Measurements were taken with an accuracy of 0.1 cm for height (cm) and 0.1 kg for body mass (kg) using a SECA 756 scale (Seca GmbH & Co. KG., Hamburg, Germany). Body mass (kg) was divided by height (m) squared to calculate the Body Mass Index (BMI). The results were used as a basis for assessing the relationship between height and body mass about age-appropriate centile grids for both the Polish and Turkish groups. The BMI values were compared to the national centile grids [27,28]: BMI ≤ 5% is underweight; BMI 5%–85% is normal body weight; BMI ≥ 85% and <95% is overweight; BMI ≥ 95% is obesity.

2.3.2 Analysis of Attitudes towards One’s Own Body

The BESAA scale provides a multidimensional analysis of attitudes toward one’s body, encompassing specific aspects related to weight, overall appearance, and social perception. It serves as a valuable tool for research on body image, particularly in examining the mediating role of body perception in the relationship between education, physical activity, and EDs [29,30].

The Polish adaptation of the BESAA scale consists of 23 items (10 negative and 13 positive), with responses recorded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The scale includes negative items (4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 18, 19, and 21), which are reverse-scored. The items are divided into three subscales [29].

The BE-Appearance subscale consists of 10 items related to general feelings about physical appearance, providing insight into participants’ satisfaction with their overall look. Scores on this subscale are systematically associated with overall self-esteem measures, which may influence the extent to which individuals develop obsessive behaviors. The BE-Weight subscale consists of 8 items focusing on satisfaction with body weight. This subscale is particularly significant, as its scores correlate with BMI, and dissatisfaction with weight may trigger restrictive eating behaviors. The BE-Attribution subscale consists of 5 items that reflect beliefs about how others perceive one’s appearance. Reliability analysis using McDonald’s ω was conducted on the BESAA scale results. The obtained coefficient of 0.72 indicates a good internal consistency of the scale [29].

The Turkish adaptation of the BESAA scale consists of 15 items (7 negative and 8 positive), as one item was not approved by the Provincial Directorate of the Ministry of National Education, and additional items were removed due to cross-loading on multiple dimensions. Respondents provide answers on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The items are divided into three subscales. The final Turkish version of BESAA consists of six items for BE-Weight, four for BE-Appearance, and five for BE-Attribution. The McDonald’s ω coefficient for the whole scale was 0.95, indicating acceptable or good internal consistency [30].

The ten-item DOS scale is used as a universal measure for assessing and screening ON. Originally developed in German by Barthels et al. in 2015, the DOS demonstrates strong internal consistency, solid construct validity, and reliable test-retest stability [31]. Respondents complete the ten-item DOS using a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “definitely does not apply to me” to “definitely applies to me”, with no reverse-scored items. The DOS scale, evaluates attitudes and behaviors related to an obsessive pursuit of healthy eating, with example questions including “I pay close attention to the quality of the foods I consume” and “I feel guilty when I deviate from my strict dietary rules.” The maximum possible score is 40 points. The interpretation of scores is as follows: a total score of 30 or higher suggests the presence of ON, a score between 25 and 29 indicates a risk of ON, and a score below 25 signifies no risk of ON [31].

In this study, due to the diverse national backgrounds of the participants, both the Polish version of the ten-item DOS (PL-DOS) and the Turkish version (Düsseldorf Ortoreksiya Ölçeği-DOÖ) were used for reassessment [32,33]. The reliability of PL-DOS and DOÖ was comparable to the original E-DOS version, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.84 and 0.87, respectively [32,33]. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha values for the scales used in the study were 0.82 for PL-DOS and 0.84 for DOÖ, confirming good internal consistency.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica version 13.3 (StatSoft, Kraków, Poland) and the R software (version 4.0.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020) operating under the GNU General Public License (GPL). Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean values (X), median (Med), standard deviations (SD), minimum (min), maximum (max), kurtosis (k), and standard error (SE). Qualitative data were expressed as percentages. The normality of data distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test, while Levene’s test was applied to assess the homogeneity of variances.

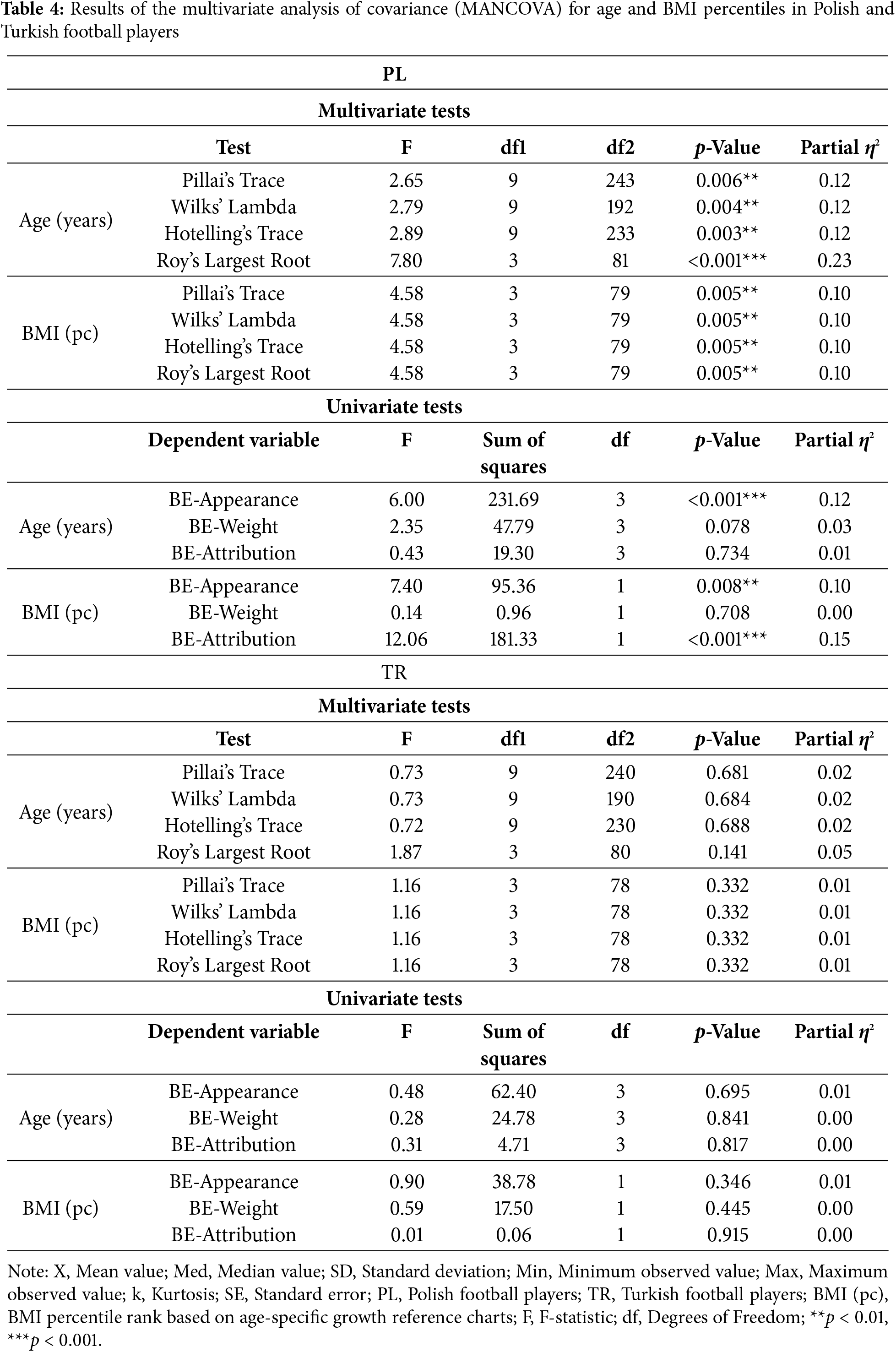

To evaluate differences in anthropometric parameters between nationality groups, the student’s t-test was applied for normally distributed variables, whereas Welch’s test was used in cases of variance heterogeneity. Differences in the distribution of BMI categories between groups were analyzed using the chi-square test, and differences in DOS scale scores were assessed via ANOVA. To examine the effect of age and BMI percentiles on body image perception, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted, with BESAA subscales (BE-Appearance, BE-Weight, BE-Attribution) as dependent variables and age and BMI percentiles as independent variables. The significance of the effects was assessed using four multivariate tests: Pillai’s Trace, Wilks’ Lambda, Hotelling’s Trace, and Roy’s Largest Root. If significant effects were detected in MANCOVA, univariate ANOVA analyses were performed to determine which dependent variables contributed to the effect. Additionally, to identify predictors of ON risk, logistic regression was conducted, including age, nationality, nutritional status, and BESAA subscale scores as predictor variables.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and for univariate analyses, multiple comparison corrections were applied using Bonferroni’s method.

3.1 Characteristics of the Study Group

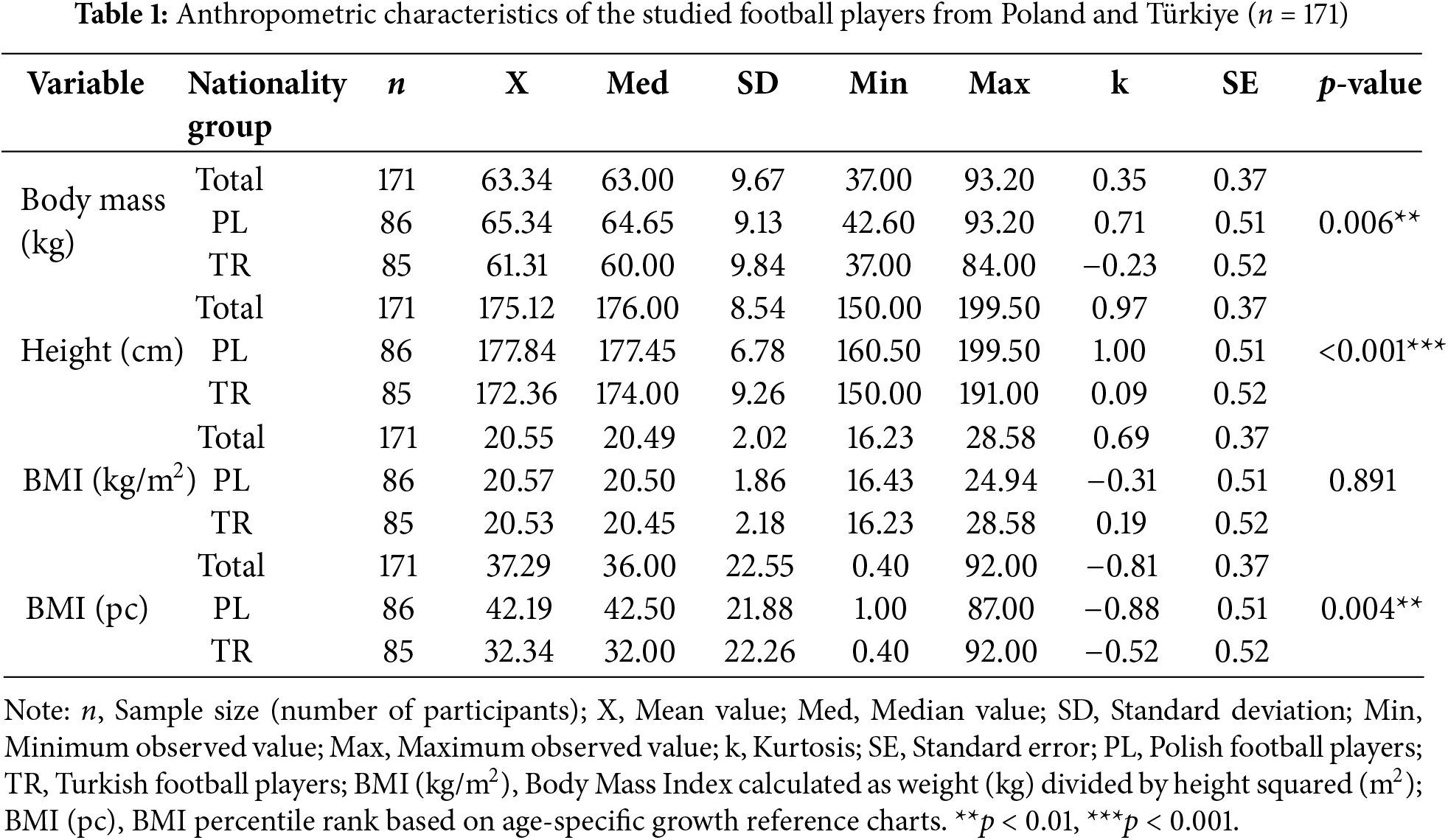

The characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1. The analysis of fundamental anthropometric parameters included body mass (kg), height (cm), BMI (kg/m2), and BMI percentiles. The results are presented for the entire sample as well as separately for Polish and Turkish players.

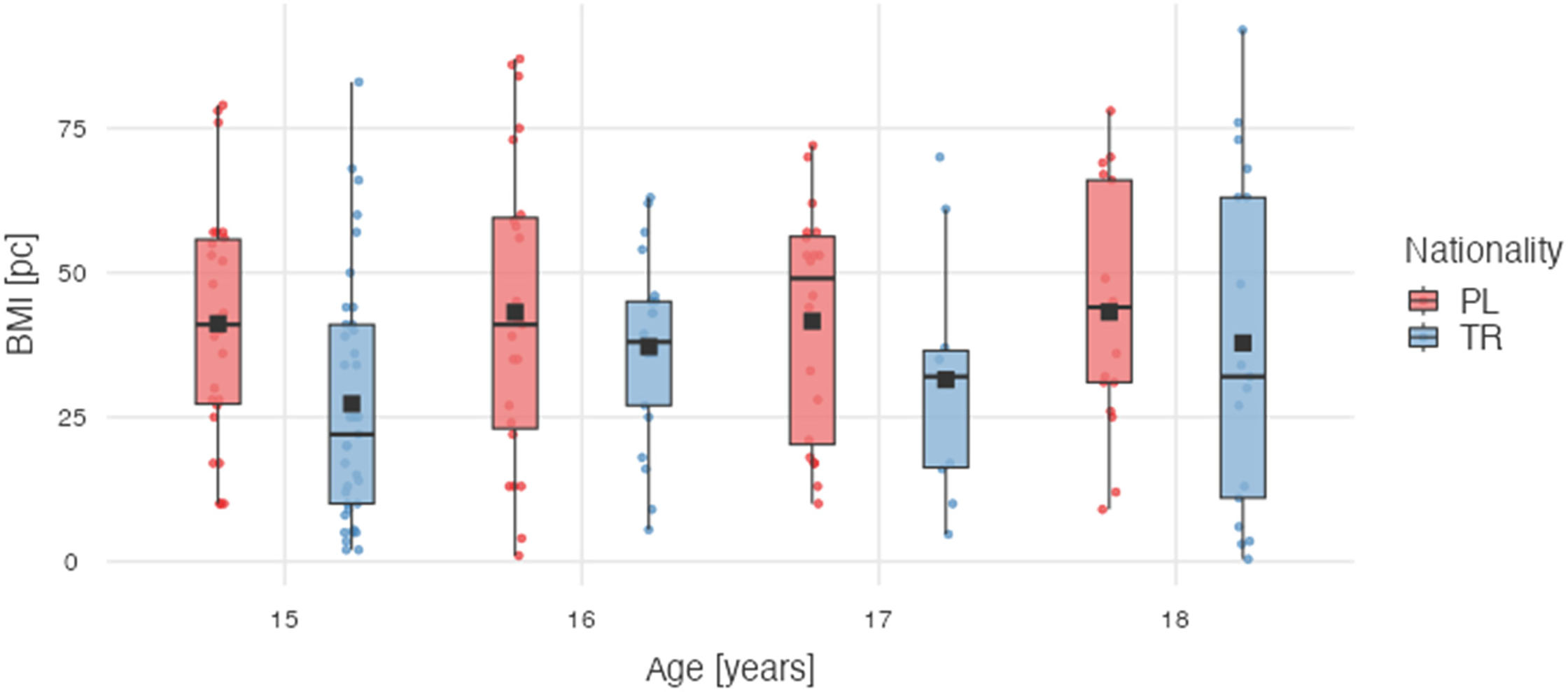

Analyzing the nutritional status according to the interpretation of national percentile grids revealed statistically significant differences between players from different countries (p = 0.048). Three players (including two from Poland) were classified as obese, while twelve players (including ten from Türkiye) were classified as underweight. Fig. 1 illustrates the distribution of BMI percentiles, considering the age and nationality of the participants.

Figure 1: Box plot illustrating BMI percentiles stratified by age groups and nationality (p = 0.298). Note: PL, Polish football players; TR, Turkish football players; BMI [pc], BMI percentile rank based on age-specific growth reference charts

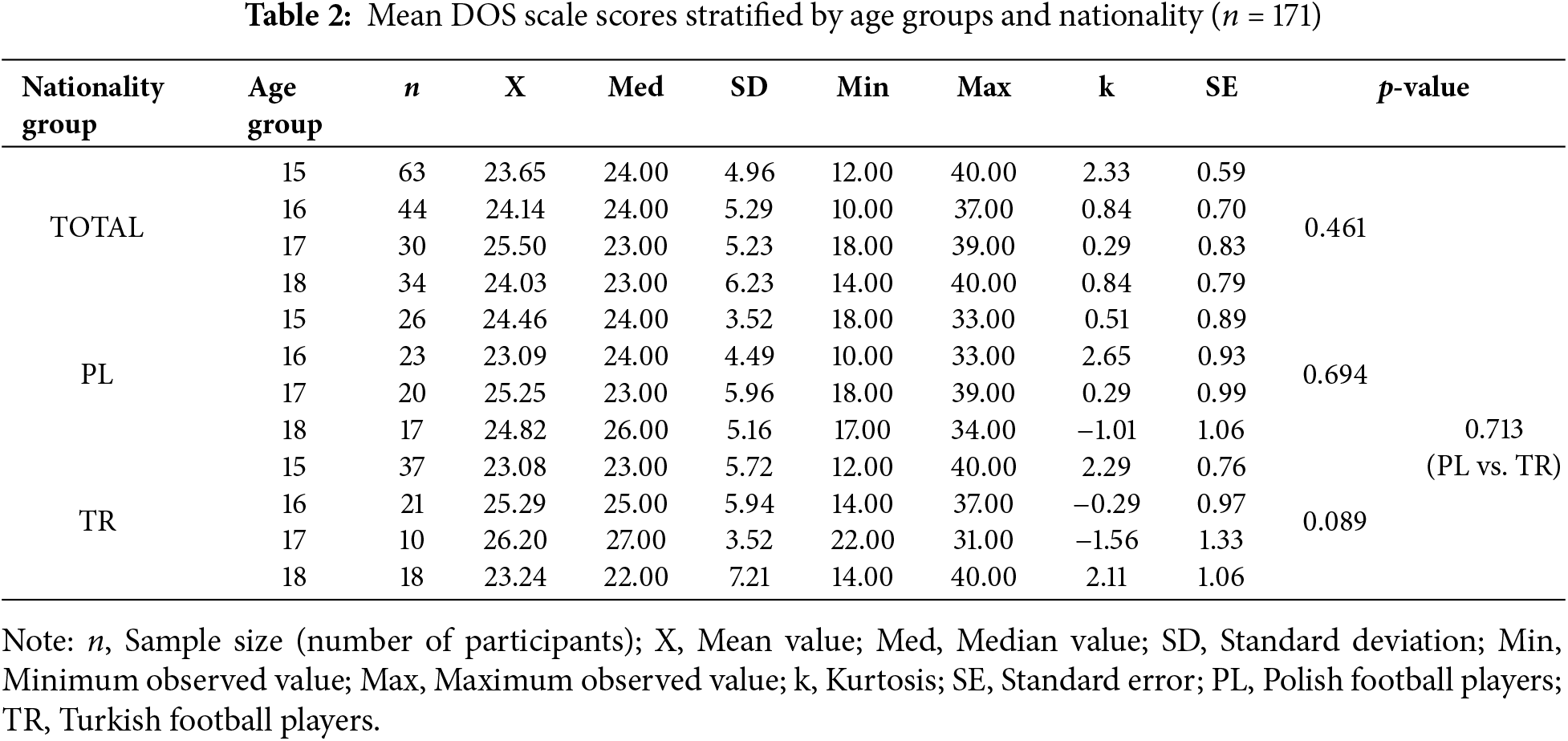

According to the interpretation of the DOS scale, 13% (n = 23) of the players met the criteria for ON, while 26% (n = 44) were classified as being at increased risk of developing the disorder. Comparative analysis revealed no significant differences between nationality groups (p = 0.938), suggesting that the ON risk level is similar among Polish and Turkish players. Similarly, no significant age-related differences were found (p = 0.694), indicating that the ON risk remained consistent across all analyzed age groups. Details of the DOS questionnaire scores obtained by age and nationality groups are shown in Table 2.

3.3 Satisfaction with One’s Appearance

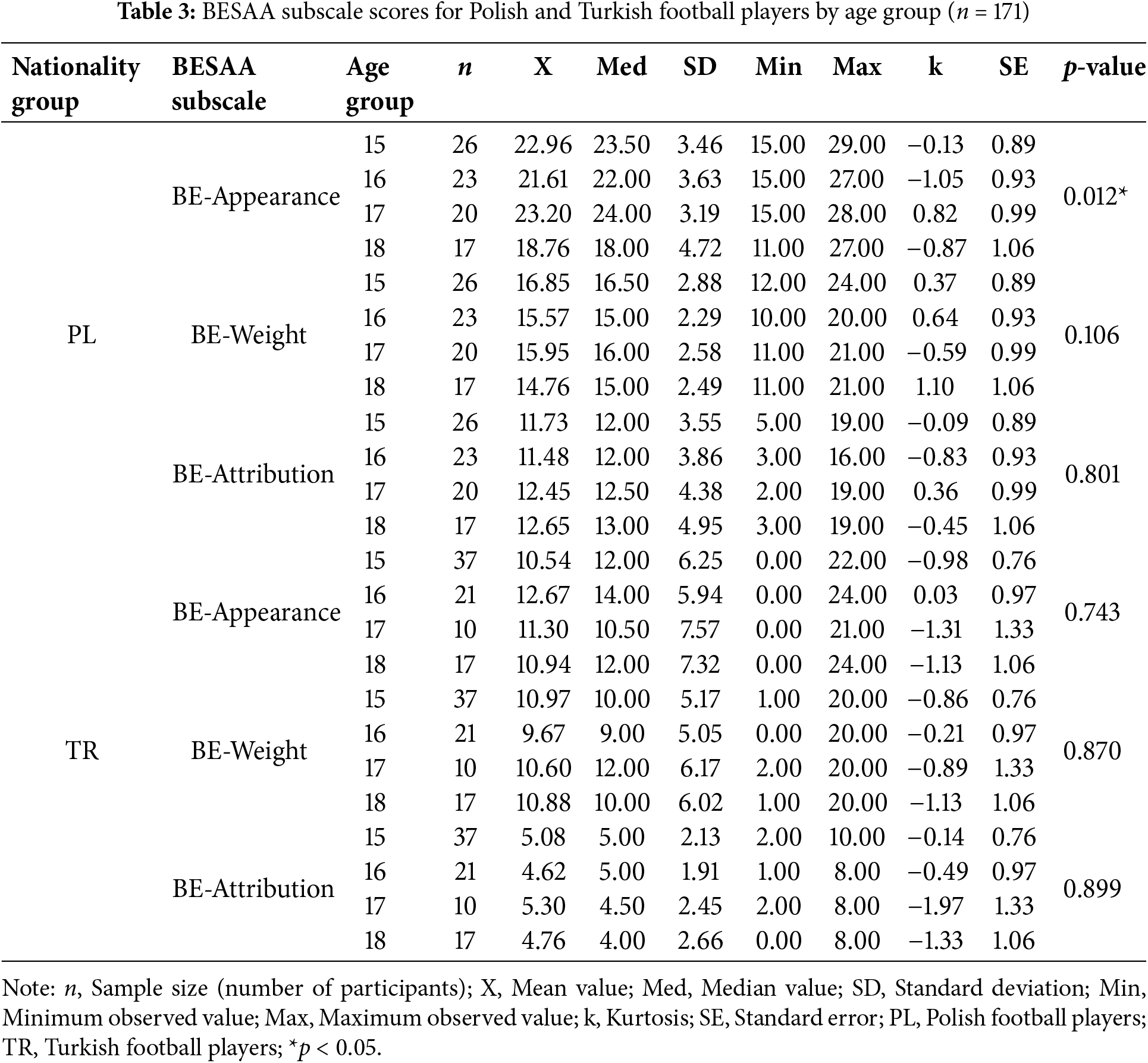

Analysis of BESAA subscale scores among PL revealed differences in self-assessment of appearance. The highest mean scores in the BE-Appearance subscale were observed among 17-year-olds (23.20 ± 3.19), while the lowest values were recorded in 18-year-olds (18.76 ± 4.72). The statistical significance of this effect was confirmed (p = 0.012), suggesting that self-perception of appearance may change with age. However, no significant associations were found between age and scores in the BE-Weight (p = 0.106) and BE-Attribution (p = 0.801) subscales among Polish players. Among Turkish football players, no significant associations were observed between age and scores in any of the three BESAA subscales (BE-Appearance, BE-Weight, and BE-Attribution, p = 0.743 p = 0.870; p = 0.899, respectively). Detailed information is presented in Table 3.

To examine the effect of age and BMI percentiles on body image perception among Polish and Turkish football players, a MANCOVA was conducted. The three BESAA subscales (BE-Appearance, BE-Weight, and BE-Attribution) were included as dependent variables, while age and BMI percentiles were treated as independent variables. Multivariate tests revealed a significant effect of both age and BMI percentiles on at least one aspect of body self-esteem among Polish players, as confirmed by Pillai’s Trace, Wilks’ Lambda, Hotelling’s Trace, and Roy’s Largest Root statistics. Univariate analysis demonstrated that age had a significant impact on BE-Appearance (p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.12), indicating a moderate effect size. In addition, BMI percentiles showed significant effects on both BE-Appearance (p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.10) and BE-Attribution (p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.15), suggesting moderate to large practical significance. No significant effects were found for BE-Weight (p = 0.708).

In contrast, multivariate tests for the Turkish group did not show any significant effects of age or BMI percentiles on the dependent variables, as confirmed by Pillai’s Trace, Wilks’ Lambda, Hotelling’s Trace, and Roy’s Largest Root (all p > 0.05). Likewise, univariate analyses yielded non-significant results for age and BMI percentiles across all three BESAA subscales (BE-Appearance, BE-Weight, BE-Attribution), with negligible effect sizes (partial η2 < 0.02). Detailed results are presented in Table 4.

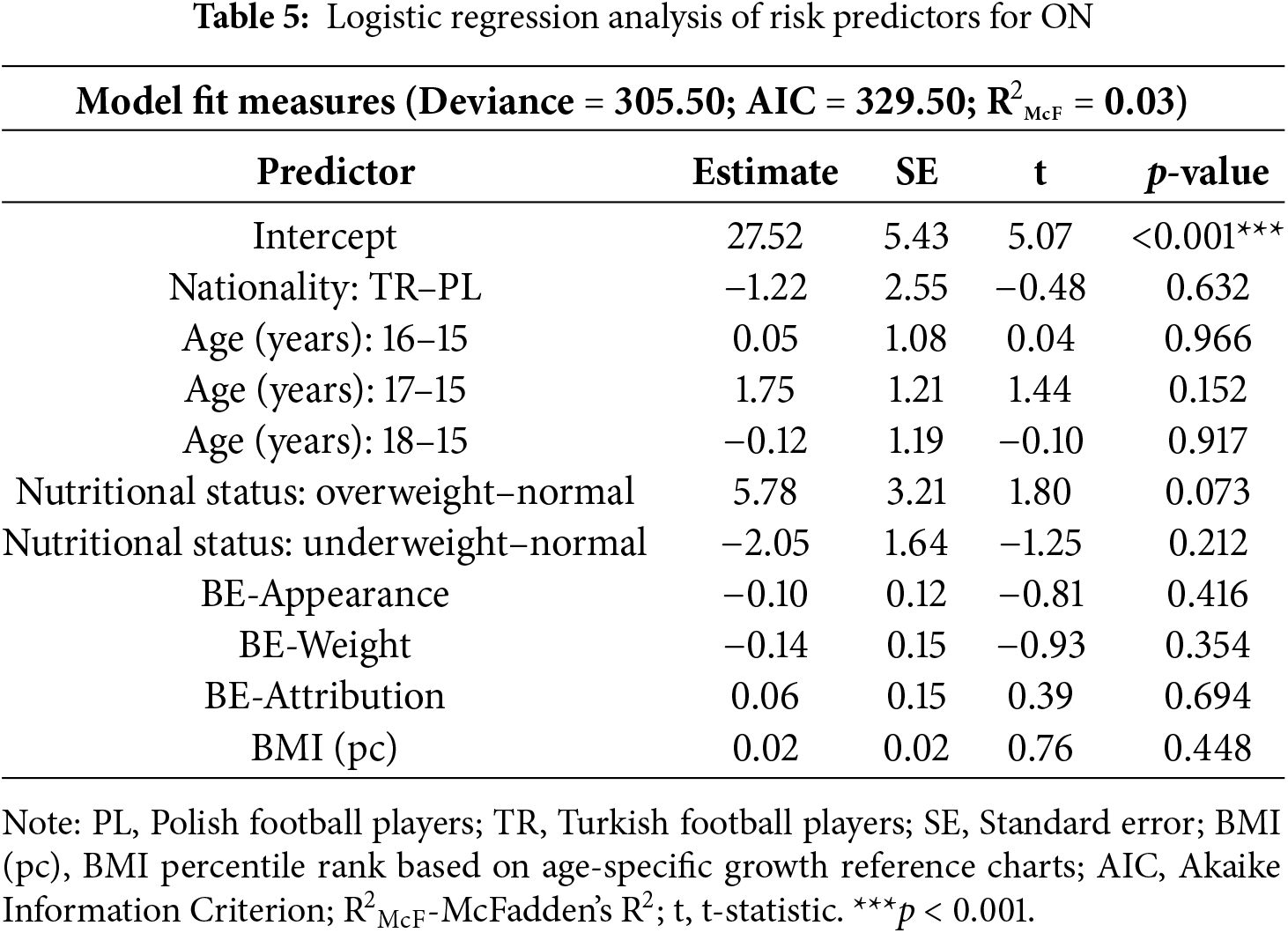

3.4 Analysis of Risk Predictors for ON

To determine the predictive factors for the risk of developing ON, logistic regression analysis was conducted. The regression model did not identify significant predictors such as age, nationality, nutritional status, and scores in BESAA subscales that would influence the risk of ON. Moreover, the effect size measure (McFadden’s R2 = 0.03) indicates that the model explains only about 3% of the variance in ON risk, suggesting a small practical effect size and limited predictive capacity (Table 5).

An analysis of scientific publications indicates that previous studies assessing the risk of ON among athletes, including male and female football players, have predominantly focused on adult populations [15,24]. By contrast, adolescent athletes have been relatively underrepresented in such analyses, despite undergoing intense psychological and physical changes that may render them more susceptible to the development of EDs [34]. Therefore, conducting a study involving adolescent football players is important, as it fills a significant research gap and provides a deeper insight into the specific risk factors for ON in this population. The present study offers findings on the risk of ON and the relationship between nutritional status and body image perception among adolescent football players from Poland and Türkiye, thereby complementing existing data.

The study results showed that 13% of the players exhibited ON characteristics, and 26% had an elevated risk of developing this disorder; notably, no significant differences in ON risk were found between Polish and Turkish football players. These findings suggest that, within our sample, ON risk appears relatively consistent across the two cultural contexts examined. Further research in a broader range of cultural settings would be necessary to confirm whether these patterns hold universally. Moreover, they align with the results of Zydek et al., who reported a significant level of ON risk among young Polish athletes, emphasizing that psychological factors such as perfectionism may play a key role in the development of this disorder [35]. Furthermore, our findings correspond to those reported by Sylwander, who noted an ON prevalence of approximately 16%–18% among Swedish adolescents participating in team sports such as football, ice hockey, floorball, or basketball [36]. This is consistent with our observation that 13% of athletes exhibited ON characteristics. In Sylwander’s study, there was no significant increase in ON cases over time, nor were there notable differences between girls and boys [36].

When comparing our findings on ON risk in young male football players with those of a study involving female football players from Poland, Türkiye, and India, several notable differences emerge [24]. The previous study, which found nearly half of the female participants at risk or exhibiting ON characteristics, identified significant associations between ON risk and factors such as age, dietary exclusions, social media use, and sources of nutritional information. Additionally, a significant relationship between nationality and ON risk was noted among female athletes, with the highest frequency of ON risk observed among Indian female players [24]. This partially contrasts with our results, as we found no differences between Polish and Turkish male players. Interestingly, the previous study reported that the relationship between sociocultural attitudes and ON risk was non-significant [24]. These discrepancies suggest that cultural factors may have a different or less pronounced impact on ON risk among young men compared to female populations. Further cross-cultural studies involving diverse regions and ethnic groups are warranted to draw broader conclusions.

Furthermore, the study revealed that, among Polish football players, the perception of one’s own body appearance changes with age, indicating a dynamic development of body image during adolescence. In contrast, no relationship was observed between age and the evaluation of appearance, weight, or attribution among Turkish players. These results suggest that the formation of body image among young athletes may be more complex and dependent on specific cultural and social factors. The findings of the present study partially overlap with those reported in Harriet Davies’ systematic review, which indicates that body dissatisfaction often develops during adolescence and that young athletes may be more susceptible to it due to the pressures associated with sports participation [37]. Additionally, Davies notes greater exposure to body dissatisfaction among young female athletes compared to male athletes; however, our study focused exclusively on a male cohort, which prevents a direct comparison with those conclusions [37].

Relating our findings to a study on body image perception among Italian adolescents reveals several notable similarities [38]. In the Italian study, which included both young athletes and non-athletes, it was found that engaging in sports was associated with a more favorable perception of one’s own body and a lower incidence of EDs—particularly among athletes, while the most negative evaluations were recorded among non-athletes, especially females [38]. Although our sample consisted solely of young athletes, the results suggest that the process of body image development may be influenced by both developmental and cultural factors. In the Italian study, the positive impact of sports activity on body satisfaction underscores the potential benefits of sport in promoting a healthy body image [38].

Our own results show that, among Polish football players, the perception of physical appearance varies depending on nutritional status, interpreted via BMI percentile charts. A clear relationship was observed between a higher BMI and a more positive perception of one’s body, particularly regarding the overall evaluation of appearance and the belief that others view them favorably. In contrast, such a relationship was not confirmed among Turkish players. These findings imply that the relationship between nutritional status and body image perception may be modulated by cultural and social determinants.

These perspectives align with the broader research on the construction of the male body image, often discussed in the framework of “muscularity.” Although our study did not focus directly on analyzing muscularity, the observed differences between Polish and Turkish players may indicate that culturally driven norms of masculinity—including expectations related physique and musculature—significant shape body image. Researchers developing the concept of “muscularity” emphasize that in various cultures, muscle mass can be viewed as an indicator of attributes such as socioeconomic status, intelligence, or professionalism [39]. Meanwhile, in our study, the changes in appearance perception noted among PL may result from maturation processes and the internalization of specific cultural norms that may not necessarily be analogous among Turkish athletes. These observations suggest that male body image is a multidimensional construct, deeply rooted in cultural contexts [39].

Another study involving boys participating in both individual and team sports found that those who were overweight demonstrated greater body dissatisfaction and lower performance on fitness tests [40]. Moreover, in that study, body dissatisfaction served as a significant mediator of the effect of BMI on perceived physical ability among team-sport athletes [40]. Our findings, obtained in a group of football players, suggest that within a specific cultural and athletic context, a higher BMI may be viewed as beneficial for body image, potentially due to greater muscle mass and normative expectations associated with the sport. These differences may indicate that the relationship between BMI and body image satisfaction is highly dependent on the characteristics of the population under study and the sporting context, underscoring the need for further comparative research across various sports and cultural groups [40].

An analysis of ON risk predictors—considering age, nationality, nutritional status, and body image assessment—did not identify any single variable that unequivocally determined ON risk. This finding suggests that ON risk is likely the result of the interaction among multiple factors, including psychological, social, and cultural variables, whose roles were not fully captured in our model.

In the study by Staśkieicz-Bartecka et al., the relationships between body composition parameters and the risk of EDs, ON, and body image perception in adult elite football players were examined [15]. The results indicated that a higher fat mass was associated with an increased risk of EDs, whereas muscle mass did not have a significant effect. However, body composition was not found to be a predictor of ON risk, highlighting a complex relationship among body composition, body perception, and ON risk [15].

The results of this study underscore that young football players, regardless of nationality, may be at risk of developing ON, suggesting the need for preventive measures to be implemented during adolescence. Such measures could include both nutritional education and psychological support. The fact that a higher BMI was correlated with a more positive self-assessment of appearance among Polish players, whereas no such relationship was observed in the Turkish group, highlights the potential importance of specific cultural and social factors in shaping body image. Our findings indicate that preventive interventions may benefit from being tailored to the cultural context and the athletes’ age, while also considering the multifaceted nature of EDs. Further studies are needed to determine the most effective strategies. In practice, this implies close collaboration among coaches, dietitians, and sports psychologists to develop programs that promote a balanced approach to diet and physical activity, while simultaneously fostering positive self-esteem.

Future research should analyze how body composition influences ON risk and body image perception to better understand how these factors determine body image and ON risk. It would also be valuable to extend such studies to include both male and female athletes to capture any gender-related differences in the development of ON and body perception. Additionally, involving physically inactive individuals could help determine whether the observed phenomena are primarily related to sports participation or to other psychosocial factors. Longitudinal studies are also recommended, as they would enable tracking changes in body image perception during adolescence and athletic development. Furthermore, incorporating additional psychological variables (e.g., perfectionism, sense of control, self-esteem) could offer deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying ON development among young athletes.

This study has several strengths that enhance its scientific value. First, the use of well-validated research tools—specifically the Polish and Turkish versions of the BESAA scale and the DOS—ensures the reliability of the obtained results. Additionally, the statistical analyses, including MANCOVA and logistic regression, enable a detailed assessment of the influence of various factors. Nonetheless, some limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. The cross-sectional design of the study prevents the establishment of causal relationships and the observation of changes over time, and focusing exclusively on a male sample restricts the generalizability of the results to the broader population of young athletes, including female players. Moreover, reliance on self-report measures introduces the potential for errors stemming from participants’ subjective assessments. Although the study investigates the impact of factors such as age, nutritional status, and nationality, it does not consider other possible risk predictors—such as personality traits or the level of perfectionism—nor does it include a body composition analysis, which could more precisely elucidate the complexity of this phenomenon among young athletes.

Finally, while our findings provide valuable insights into risk factors for EDs among adolescent football players, their significance in advancing the existing literature on EDs remains somewhat uncertain. The limited scope of this study and its cross-sectional nature complicate direct comparisons with other research, making it difficult to determine conclusively how these results extend current knowledge in this area.

The study’s results revealed that 13% of the players exhibited characteristics of ON, while an additional 26% were at an elevated risk of the disorder. Comparisons between players from Poland and Türkiye did not show significant differences in the prevalence of ON risk. Regarding body image, the analysis demonstrated that in the group of Polish footballers, self-perception of appearance varied with age, whereas no relationship between age and appearance ratings was observed among Turkish players. Furthermore, among the Polish athletes, an association was found between nutritional status—interpreted through BMI relative to percentile charts—and body image perception, particularly concerning overall appearance and how the players believe they are perceived by others; however, such an association was not confirmed in the group of Turkish players. Finally, the analysis of predictive factors for ON risk, which considered age, nationality, nutritional status, and body image assessment, did not identify any individual variables that could unequivocally determine the risk of developing ON. These findings suggest that other factors may also be involved, and further studies are necessary to confirm these observations.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; methodology, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; software, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; validation, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, Marek Kardas; formal analysis, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; investigation, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; resources, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; data curation, Samet Aktaş and Grzegorz Zydek; writing—original draft preparation, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; writing—review and editing, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; visualization, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; supervision, Oskar Kowalski; project administration, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka; funding acquisition, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bio-ethics Committee of the Silesian Medical University in Katowice (protocol code BNW/NWN/0052/KB/229/23 and date of approval: 25 October 2023), in accordance with the Act of 05 December 1996, regulating the professions of physicians and dentists (Journal of Laws 2016, item 727). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cafri G, Thompson JK. Measuring male body image: a review of the current methodology. Psychol Men Masc. 2004;5(1):18–29. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Levine MP, Smolak L. Body image development in adolescence. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, editors. Body image: a Handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2002. p. 74–82. [Google Scholar]

3. Lipowski M, Lipowska M. The role of narcissism in the relationship between objective body measurements and body self-esteem of young men. Pol Forum Psychol. 2015;20(1):31–46. (In Polish). doi:10.14656/PFP20150103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mendelson MJ, Mendelson BK, Andrews J. Self-esteem, body esteem, and body mass in late adolescence: is a Competence × Importance model needed? J Appl Dev Psychol. 2000;21:249–66. [Google Scholar]

5. Franzoi SL, Shields SA. The body esteem scale: multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. J Pers Assess. 1984;48(2):173–8. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4802_12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mendelson BK, Mendelson MJ, White DR. Body esteem scale for adolescents and adults. J Pers Assess. 2001;76(1):90–106. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA7601_6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385–94. doi:10.2147/NDT.S61665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

9. World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-11 international classification of diseases 11th revision. The global standard for diagnostic health information. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Zoe J, Serafino G, Mancuso A, Phillipou A, Castle DJ. What is OSFED? The predicament of classifying “other” eating disorders. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(5):e147. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ponce-Gonzalez JG, Corral-Perez J, de Villarreal ES, Gutierres-Manzanefo JV, De Castro-Maqueda G, Casals C. Antioxidants markers of professional soccer players during the season and their relationship with competitive performance. J Hum Kinet. 2021;80:113–23. doi:10.2478/hukin-2021-0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Woods G, McCabe T, Mistry A. Mental health difficulties among professional footballers: a narrative review. Sports Psychiatry. 2022;1(2):57–69. doi:10.1024/2674-0052/a000010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Smolak L. Body image in children and adolescents: where do we go from Here? Body Image. 2004;1(1):15–28. doi:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00008-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Voelker DK, Reel JJ, Greenleaf C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2015;6:149–58. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S68344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Zydek G, Michalczyk MM, Kardas M. Prevalence of eating disorders and self-perception concerning body composition analysis among elite soccer players. J Hum Kinet. 2025;95:259. doi:10.5114/jhk/194464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Kardas M. Eating disorders risk assessment and body esteem among amateur and professional football players. Nutrients. 2024;16(7):945. doi:10.3390/nu16070945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kumari R, Rosali B, Anubhav V, Pawanindra L. Hindi translation, cultural adaptation and validation of eating disorder diagnostic scale. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64(Suppl 3):S573. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.341517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liya MA, Cortney SA, Warren KM, Culbert KM. Disordered eating in Asian American women: sociocultural and culture-specific predictors. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1950. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Agüera Z, Brewin N, Chen J, Granero R, Kang Q, Fernandez-Aranda F, et al. Eating symptomatology and general psychopathology in patients with anorexia nervosa from China, UK, and Spain: a cross-cultural study examining the role of social attitudes. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Smith ML, Dunne PE, Pike KM. Cross-cultural differences in eating disorders. Encycl Feed Eat Disord. 2017;42(7):178–81. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-104-6_54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gaspar MCDMP, de Morais Sato P, Scagliusi FB. Under the “weight” of norms: social representations of overweight and obesity among Brazilian, French and Spanish dietitians and laywomen. Soc Sci Med. 2022;298(6):114861. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Melisse B, de Beurs E, van Furth EF. Eating disorders in the Arab world: a literature review. J Eat Disord. 2020;8(1):59. doi:10.1186/s40337-020-00336-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bratland-Sanda S, Sundgot-Borgen J. Eating disorders in athletes: overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment. Eur J Sport Sci. 2013;13(5):499–508. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.740504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Kalpana K, Aktaş S, Khanna GL, Zydek G, Kardas M, et al. The impact of social media and socio-cultural attitudes toward body image on the risk of orthorexia among female football players of different nationalities. Nutrients. 2024;16(18):3199. doi:10.3390/nu16183199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kussman A, Choo HJ. Mental health and disordered eating in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2024;43(1):71–91. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2023.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Joy E, Kussman A, Nattiv A. 2016 Update on eating disorders in athletes: a comprehensive narrative review with a focus on clinical assessment and management. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(3):154–62. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kaługa Z, Różdżyńska-Świątkowska A, Grajda A, Gurzkowska B, Wojtyło M, Góźdź M, et al. Growth and nutrition standards for polish children and adolescents from birth to 18 years of age. Standard Med Pediatr. 2015;12:119–35. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

28. Neyzi O, Bundak R, Gökçay G, Günöz H, Furman A, Darendeliler F, et al. Body Weight, Height, Head Circumference, and Body Mass Index Reference Values in Turkish Children. Cocuk Sagligi Hast Derg. 2008;51:1–14. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Słowińska A. Body esteem scale for adolescents and adults (BESAA)—polish adaptation. Pol J Appl Psychol. 2019;17(1):21–31. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

30. Arslan UE, Özcebe LH, Ünlü HK, Üner S, Yardim MS, Araz O, et al. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the body esteem scale for adolescents and adults (BESAA) for children. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(2):471–7. doi:10.3906/sag-1902-171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Barthels F, Meyer F, Pietrowsky R. The Düsseldorf orthorexia scale—construction and evaluation of a questionnaire to assess orthorexic eating behavior. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 2015;44:97–105. [Google Scholar]

32. Brytek-Matera A. The polish version of the düsseldorf orthorexia scale (PL-DOS) and its comparison with the English version of the DOS (E-DOS). Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(4):1223–32. doi:10.1007/s40519-020-01025-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Bilekli Bilger I. Adaptation of orthorexia nervosa scales and examination of relationships with obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, stress, health anxiety, body perception, and self-esteem [dissertation]. Ankara, Turkey: Hacettepe University; 2022. [cited 2025 Apr 29]. Available from: https://openaccess.hacettepe.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/11655/27203. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

34. Mancine R, Kennedy S, Stephan P, Ley A. Disordered eating and eating disorders in adolescent athletes. Spartan Med Res J. 2020;4(2):11595. doi:10.51894/001c.11595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zydek G, Kardas M, Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W. Perfectionism, orthorexia nervosa, and body composition in young football players: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2025;17(3):523. doi:10.3390/nu17030523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sylwander C. A longitudinal study of frequency of orthorexia nervosa and jump performance among adolescents in team ball sports [bachelor’s thesis]. Halmstad, Sweden: Halmstad University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

37. Davies H. Systematic review of body image dissatisfaction in young athletes and non-athletes, and an empirical study of the link between disgust and body image in an analogue sample [dissertation]. Cardiff, Wales: Cardiff University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

38. Toselli S, Rinaldo N, Mauro M, Grigoletto A, Zaccagni L. Body image perception in adolescents: the role of sports practice and sex. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22):15119. doi:10.3390/ijerph192215119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Monocello L. Guys with big muscles have misplaced priorities: masculinities and muscularities in young South Korean Men’s body image. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2023;47(2):443–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

40. Morano M, Colella D, Capranica L. Body image, perceived and actual physical abilities in normal-weight and overweight boys involved in individual and team sports. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(4):355–62. doi:10.1080/02640414.2010.530678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools