Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Moral Disengagement, Preference for Solitude, and Demographic Factors as Predictors of Aggressive Behavior Categorized by Latent Profile Analysis in Chinese Rural Boarding Junior High School Students

1 School of Basic Medical Sciences, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, 611137, China

2 School of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, China

* Corresponding Author: Wangqin Hu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Latent Profile Analysis in Mental Health Research: Exploring Heterogeneity through Person Centric Approach)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1383-1398. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066974

Received 22 April 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Adolescents’ aggression is widely studied, the underlying heterogeneity of aggression among rural Chinese boarding students remains unexplored. This study investigates the latent profiles of Chinese rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression and its correlations with moral disengagement and preference for solitude. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted from 04–22 April 2022, using a convenient sampling method among 516 junior high school students from six Chinese rural boarding schools. The survey included the Aggression Questionnaire, the Moral Disengagement Scale (MDS), and the Preference for Solitude Scale (PSS). Results: Participants were divided into three latent profiles: low (36.0%), medium (50.9%), and high aggression levels (13.1%). Compared with low aggression, students who felt left-behind (minors who stay in the rural areas while one or both parents migrated to the urban areas for the work) accounted for a larger proportion in the medium aggression profile. The higher the grade level and the lower the educational level of the students’ parents, the greater proportion of students in the medium and high aggression profiles. Additionally, students with high moral disengagement and preference for solitude showed a significant association with the medium aggression and high aggression profiles. Conclusions: The results demonstrate the significant group heterogeneity of aggression groups in Chinese rural boarding junior high school students. Targeted prevention and intervention measures can be carried out according to feeling left-behind, grade level, parents’ education, and MDS and PSS scores.Keywords

Adolescent aggressive behavior is closely related to their physical and mental health [1]. In recent years, the aggressive behavior of adolescents has increased, which has become a major concern of many researchers [2]. Considering the Chinese educational system, junior high school students are generally refer the grade 7 to 9, corresponding age range between 12 to 15 years [3]. Existing evidence suggests that for adolescents with higher aggression, their physical and mental health, and interpersonal relationships are relatively poor; higher aggression has also been shown to hinder the healthy development of adolescent personality [4,5]. Across adolescent aggression research, rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression has become a popular focus [6]. This could be, in part, because adolescent rural boarding students live in a closed school environment for a prolonged time and lack parental companionship and support, so they are prone to psychological and behavioral problems [7–9]. For instance, previous research has shown that the mental health of non-boarding students was significantly better than that of boarding students, after investigating the mental health status of 274 boarding junior high school students and 300 non-boarding junior high school students [10]. A survey of 59 rural schools in five provinces in China also compared the mental health status and behavioral performance of boarders and non-boarders, finding that boarding students were worse than non-boarding students in both areas and more likely to show aggressive behavior [11]. Another study focusing on the developmental problems of rural boarding students found that rural boarding students showed higher aggression and impulsivity than non-boarding students [12]. The literature has consistently demonstrated that aggression is a prominent issue occurring in rural boarding student samples. It is essential to explore the contributing factors of aggression to ensure the healthy development and well-being of rural boarding junior high school students.

Beyond cognitive and psychological factors, the behaviors of rural residential middle school students are significantly influenced by certain demographic variables that are particular to their living context. Recent studies have broadly pointed out two key factors: left-behind children and parental education, both of which exert significant impacts on students’ psychology and behavior [13–15]. Left-behind children are defined as children living in rural areas whose parents have migrated to the city center to make a living. Because of being separated from their parents for a long time, left-behind children lack mental support and supervision, often experiencing significant mental distress [16]. Existing studies have shown that, in contrast to peers who live with their parents, left-behind children exhibit higher levels of impulsivity, aggression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and social withdrawal [17–19]. Existing literature has demonstrated that children’s aggressive behavior is highly influenced by parenting styles and parent-child attachment, which are indirectly influenced by some significant demographic factors (i.e., parental academic levels, left-behind experience, emotional and social development, etc.) [20,21]. Lower parental education levels and left-behind experiences tend to have lower parent-child attachment and harsh parenting, disrupt emotional regulation, and multiply the likelihood of aggressive behavior [22]. Often, these parental demographic factors do not directly impact a child’s aggressive behavior; rather, it declines the emotional resilience to cope with the stress, which subsequently affects the aggression.

Extensive empirical studies on aggression in rural boarding junior high school students have mostly been divided into the dimensions and scores of the students on an aggression questionnaire, the variable-centered approach that assumes that all the participants were homogeneous. The conclusions drawn from these studies then reflect the overall average of the aggression levels in rural boarding junior high school students but ignore individual differences [23–25]. This approach is not wrong; however, person-centered approaches, such as latent profile analysis (LPA), would provide a more in-depth understanding of the associations between the variables, considering individual differences. First, LPA emphasizes the “centrality” of individuals to classify heterogeneous groups of variables by judging the underlying characteristics of individuals [26,27]. Secondly, because LPA is based on the probability model to explore the heterogeneous classification within the group, this classification effect is more objective than the traditional cluster analysis [28]. Finally, LPA ensures that intra-class differences are minimized and inter-class differences are maximized. Thus, it will provide researchers with more valuable information to provide more targeted advice and recommendations for intervention strategies [29]. Therefore, using LPA to explore the aggressive behavior of rural boarding junior high school students may help resolve the clarity in group heterogeneity. Moreover, LPA is mostly grounded in person-environment interaction theories, which suggest that behavioral outcomes (e.g., aggression) often result from an individual’s experience influenced by the environment. In the context of this study, utilizing LPA can potentially demonstrate how different aggression profiles emerge based on various influencing factors (e.g., moral disengagement, preference for solitude, and socio-demographic characteristics, including left-behind experience and parental education). This extends a comparatively more in-depth understanding of the underlying complex mechanisms of aggressive behavior, which is hard to achieve through a variable-centered approach. Previous studies have identified that demographic variables such as age, gender, and grade were the main factors affecting the aggression of rural boarding junior high school students [8,30]. In addition, based on Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, moral disengagement is also an important factor associated with individual aggression [24]. In the adolescent literature, moral disengagement allows the individual to justify their aggressive behavior. Chinese rural boarding junior high school students often have a unique living-away experience, leading them to emotional negligence and subsequent higher levels of moral disengagement [31]. This left-behind demography is likely to use moral disengagement as a coping mechanism for their emotional distress [32]. Furthermore, this demography is also attributed to the preference for solitude, which can exacerbate aggressive behavior by voluntary social exclusion and indispensable frustration. Studies show a positive association between the level of individual moral disengagement and the level of aggression. However, most of the recent research is heavily variable-centric; further investigation is required to comprehend how and to what extent demographic variables and moral disengagement affect different types of aggressive behavior [25,26].

Students from Chinese rural boarding junior high schools offer a unique perspective to comprehend the cultural norms surrounding by collectivism and social connection related to aggressive behavior. Existing research has mainly analyzed the possible mechanisms of rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression through cognitive factors [9,17,22]. However, few studies have explored related factors from the perspective of individual needs. According to needs theory, individuals have both the need to establish contact with others and the need to be alone at all stages of development, and solitude is considered an internal motivation [33]. Theoretically, there are two main forms of solitude: one is being alone for a long time without interaction with the outside world, such as staying alone in a room; the other is being in a group without interacting with others in that group [34]. Everyone has a preference for solitude to varying degrees, which is generally referred to as a preference for solitude [35].

Existing literature has demonstrated that the preference for solitude is highly dependent on cultural norms. For example, a preference for solitude is often closely associated with psychological, social, and school maladjustment in those with an Eastern cultural background [36,37]. Conversely, in Western cultural contexts, a preference for solitude appears to have no direct connection with maladjustment [30,38]. Chinese culture emphasizes interpersonal relationships and collectivism more strongly. If an individual deliberately avoids or withdraws from group interactions, it is often regarded as unsociable or problematic behavior. In contrast to Western culture emphasizes individualism, and solitude is more widely accepted. Preference for solitude also plays different roles in individual adaptability across different ages [39,40]. For instance, in adults and the elderly, a preference for solitude is not generally linked to negative adaptation [38], whereas in adolescents, it is often closely associated with maladjustment [40]. In view of the close relationship between maladjustment and aggression [34,35], whether preference for solitude also affects the latent profiles of aggression among rural boarding junior high school students in the Chinese cultural background need to be further clarified and examined.

In sum, the present study aimed to conduct the LPA to classify rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression. LPA was utilized due to its ability to demonstrate the latent subgroups within the sample population, extending the comprehension of different aggression profiles that might be difficult to achieve through conventional variable-centered approaches. Based on the needs theory [41], we explored gender, grade level, and other demographic variables as well as moral disengagement and preference for solitude in this sample’s aggression latent profiles.

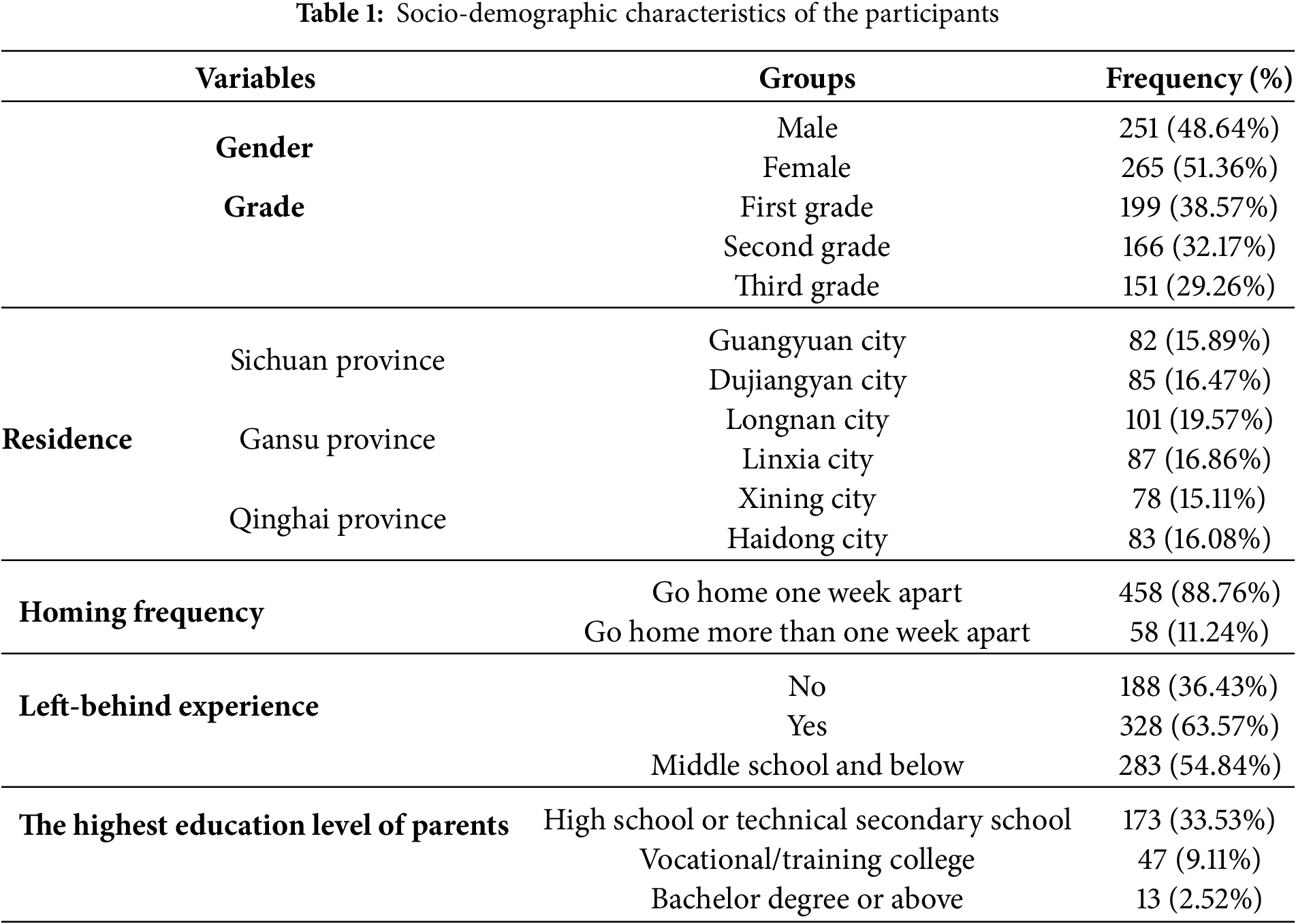

A total of 557 junior high school students were recruited from six rural boarding schools in three provinces of China by convenience sampling from 04–22 April 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwest Normal University (ERB Number: 20220311, dated: 01 April 2022). The participants’ responses were collected using a structured questionnaire. Before administering the questionnaire, we requested the head teachers of each class to obtain consent and support from the guardians. We commenced the survey after the consent of the guardians and the school authorities. Three staff members were responsible for organizing and coordinating the questionnaires on-site. Responses from 516 participants were finally included after excluding incomplete questionnaires (Male = 48.6%, Meanage = 13.28, standard deviation [SD] = 1.05), with an effective recovery of 92.64%. For the classification purpose, parental education was categorized as middle school and below, high school or technical secondary school, vocational/training college, and bachelor’s degree or above. In this study, the parental education referred to the highest level of education attained by either father or mother. Participants received stationery gifts (pens and writing pads) for participating in the survey. The demographic information of the respondents is listed in Table 1.

2.2.1 Chinese Version of Aggression Questionnaire (C-AQ)

The Chinese version of the Aggression Questionnaire was compiled by Buss and Perry [42] and revised by Liu et al. [43]. There are 20 items in the questionnaire, including 4 dimensions: vicarious aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very inconsistent with 5 = Fit in well). A higher total score denotes a higher level of aggression. The internal consistency in the present study was appropriate (Cronbach’s α = 0.89). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the data from this present study, and the results indicated good structural validity: (χ2/df = 4.19, Comparative Fit Index [CFI] = 0.94, Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI] = 0.93, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] = 0.05, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual [SRMR] = 0.04).

2.2.2 Chinese Version of Moral Disengagement Scale (C-MDS)

The Chinese version of the Moral Disengagement Scale was compiled by Bandura et al. [44] and revised by Yang and Wang [45]. There are 32 items on the scale, including eight dimensions: moral justification, euphemism labeling, favorable comparison, responsibility transfer, responsibility dispersion, distorted results, dehumanization, and blame attribution. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). A higher total score denotes a higher level of moral disengagement. The internal consistency in the present study was appropriate (Cronbach’s α = 0.91). CFA was conducted on the data from this present study, and the results indicated good structural validity: (χ2/df = 4.01, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04).

2.2.3 PQQUS Chinese Version of Preference for Solitude Scale (C-PSS)

The Chinese version of the Preference for Solitude Scale was compiled by Burger [46] and revised by Chen et al. [47]. There are 11 items on the scale, including three dimensions: solitude need, solitude value, and solitude preference. The scale is scored by the 2-point method. If subjects chose items related to solitude, scored 1 point. A higher total score denotes a higher degree of preference for solitude. The internal consistency in the present study was appropriate (Cronbach’s α = 0.88). CFA was conducted on the data from this present study, and the results indicated good structural validity: (χ2/df = 4.27, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.04).

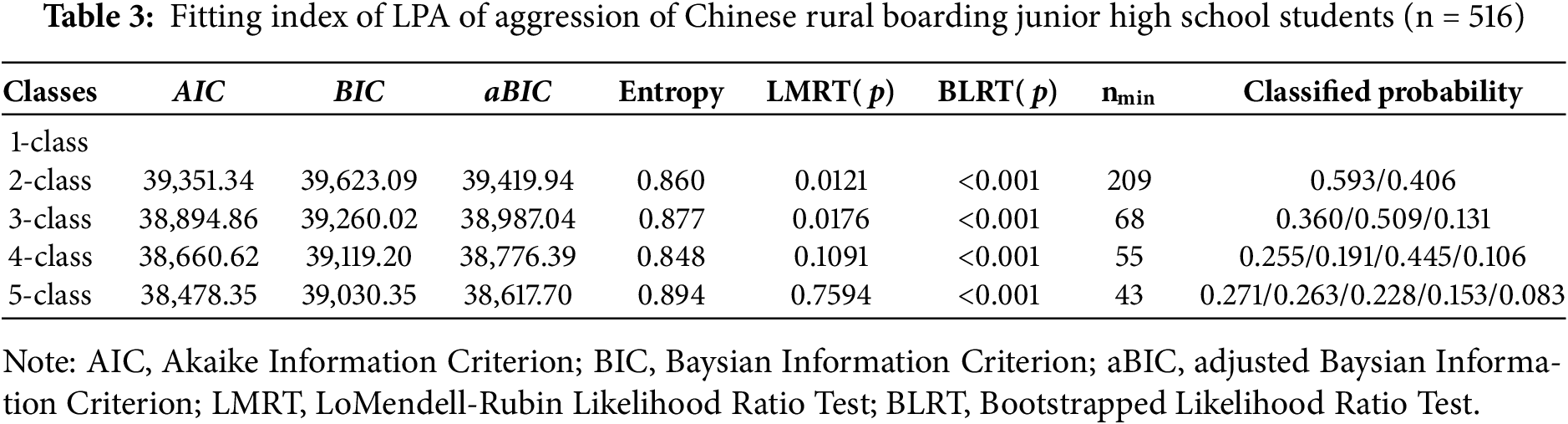

First, the mean, SD, and correlation of aggression and its dimensions, moral disengagement, and preference for solitude were obtained by SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Secondly, Mplus 8.10 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to conduct LPA analysis on the aggressive classes of rural boarding middle school students in China. In this study, the rural boarding junior high school students were divided into one class for benchmark model analysis, and then gradually added classified data for model fitting. The smaller AIC (Akaike Information Criterion), BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion), and aBIC (adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion) values signify better model fitting. The higher the Entropy value, the higher the classification accuracy. The values of LMRT (LoMendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test) and BLRT (Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test) are significant, indicating that the model with k classes is better than that with k-1 classes. Given the result structure of LPA, polychotomous logistic regression was not performed, considering the challenges regarding model fitting with the result interpretation when combining different aggression classes simultaneously. Instead, two separate models based on binary logistic regression were used, one to compare the medium aggressive class with the lower, and another to compare the higher aggression to low aggression class, respectively. This allowed comparatively more in-depth interpretations of the associations between socio-demographic variables with moral disengagement, and preference for solitude for each aggression class separately. On this basis, using SPSS 28.0, multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted with the results of potential profile analysis as the dependent variables, and gender, grade, frequency of going home, left-behind experience, educational level of parents, moral detachment and its various dimensions, and preference for solitude as independent variables. Among them, the low-aggression type was used as the reference category.

3.1 Common Methodological Deviations

Harman’s single-factor test was used to test the common method deviation. All items of Chinese rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression, moral disengagement, and preference for solitude were included in the factor analysis. The results showed that the variation explained by the first factor was 19.12%, which was below the critical value of 40%. This indicates that there is no serious common methodology bias in this study. The CFA results show that RMSEA = 0.152, CFI = 0.809, TLI = 0.778, SRMR = 0.060. Overall, the model fit is poor, indicating that there is no significant common method bias.

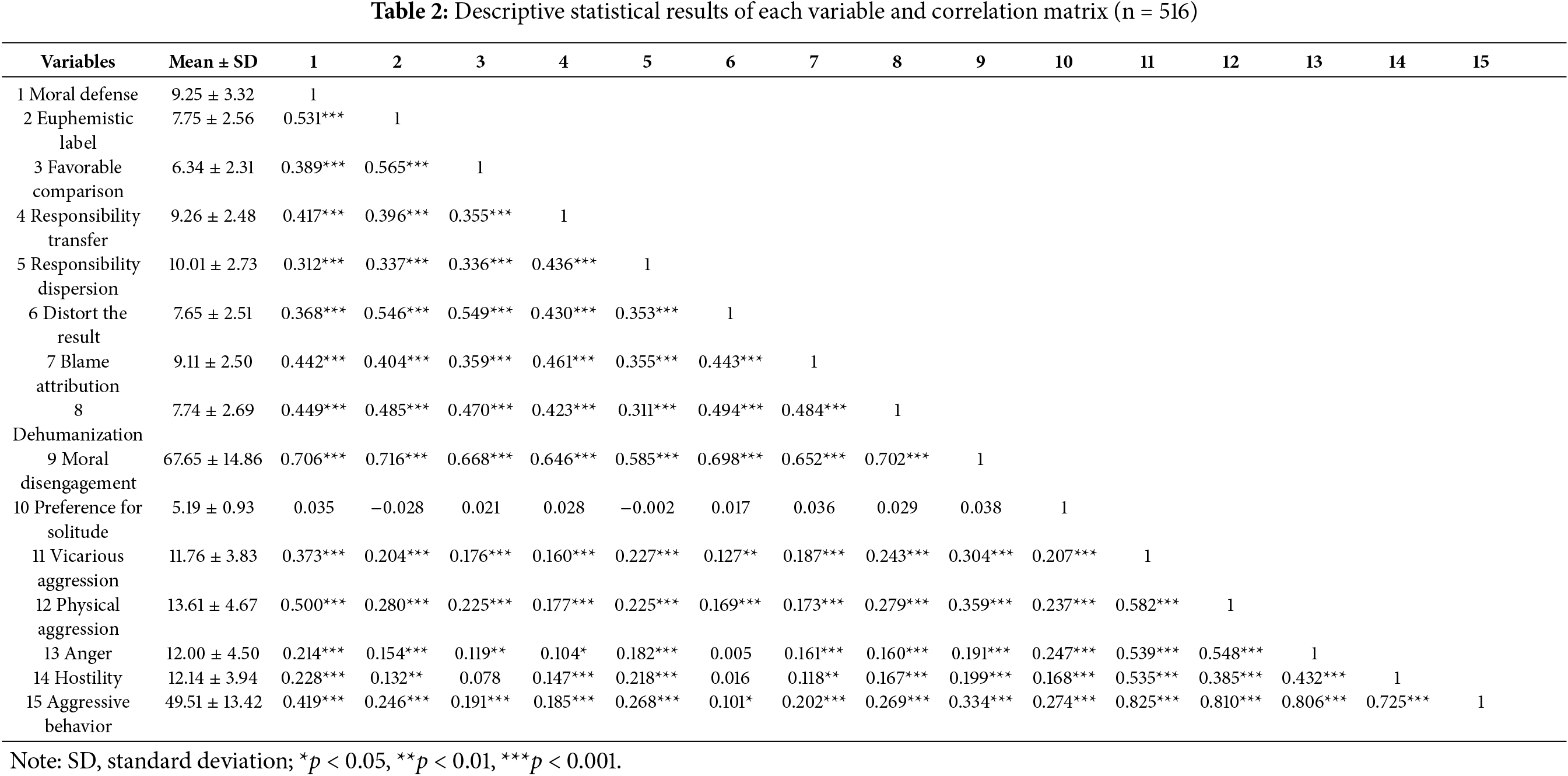

3.2 Correlation Analysis of Aggressive Behavior, Moral Disengagement, and Preference for Solitude

Pearson correlation analysis shows that aggressive behaviors of Chinese rural boarding junior high school students are significantly correlated with moral disengagement and its dimensions, as well as a preference for solitude. The descriptive statistical results and correlation matrices of each variable are shown in Table 2.

3.3 LPA Results of Chinese Rural Boarding Junior High School Students’ Aggression

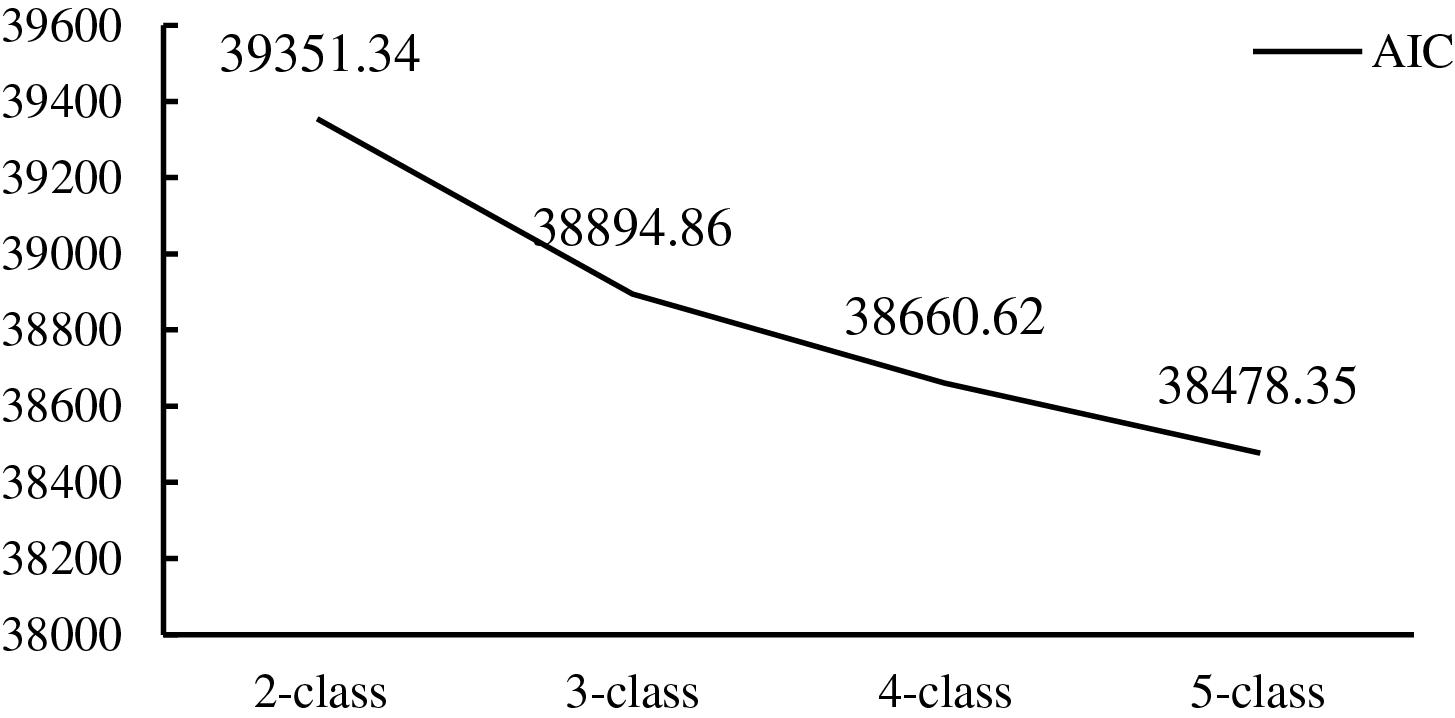

Taking the initial model as the reference point, the number of classes is increased by one, in turn, to carry out the LPA to determine the best-fitting data model. The fitting index of the LPA for classes 1–5 is shown in Table 3. The results showed that the AIC, BIC, and aBIC of the model monotonically decrease with the increase of classes, indicating that the more classes, the better, but there was no obvious inflection point to suggest several classes. All classification accuracy indexes Entropy > 0.8, indicating that both accuracies are acceptable. A transverse comparison of classes 2 to 5 showed that both LMRT and BLRT values are significant in classes 2 and 3, but Entropy is larger when aggression is divided into 3 classes. After comprehensive consideration of each index, 3 classes are selected as the classification of aggression in the sample of Chinese rural boarding junior high school students. The AIC values for the three latent classes are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: AIC values for different class

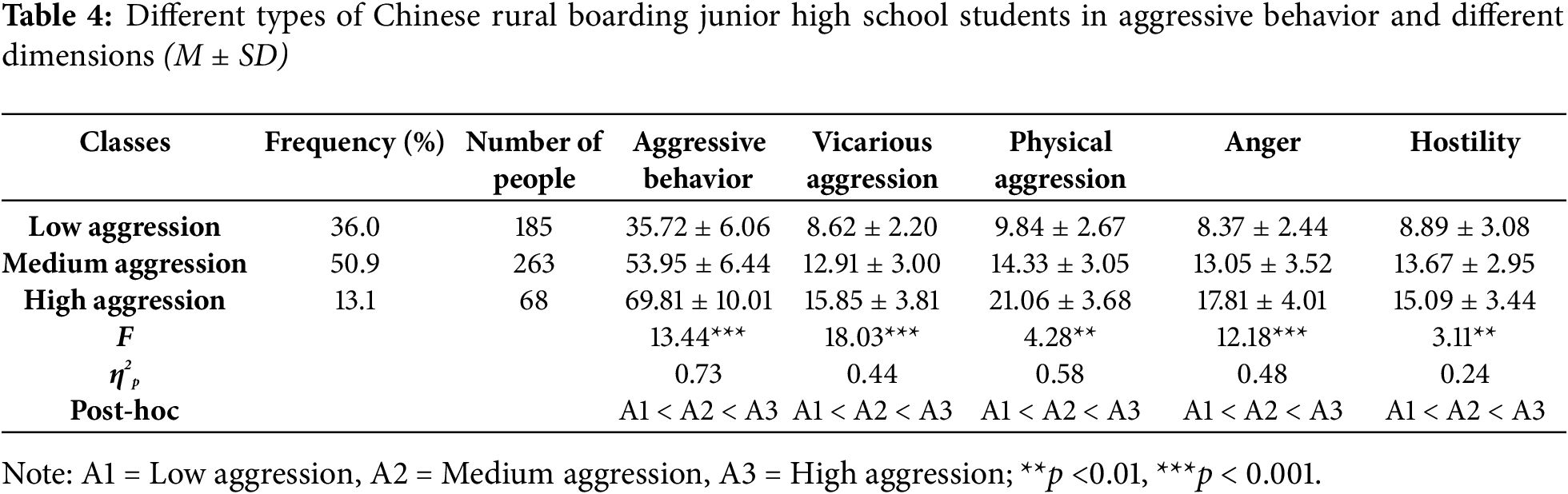

In addition, a one-way analysis of variance found that there was statistical significance in the total score of aggressive behavior and the scores of each dimension of the 3 classes for Chinese rural boarding junior high school students, F(3512) values were 13.44 (aggressive behavior), 18.03 (vicarious behavior), 4.28 (physical aggression), 12.18 (anger), and 3.11 (hostility); η2p were 0.73, 0.44, 0.58, 0.48, and 0.24, respectively.

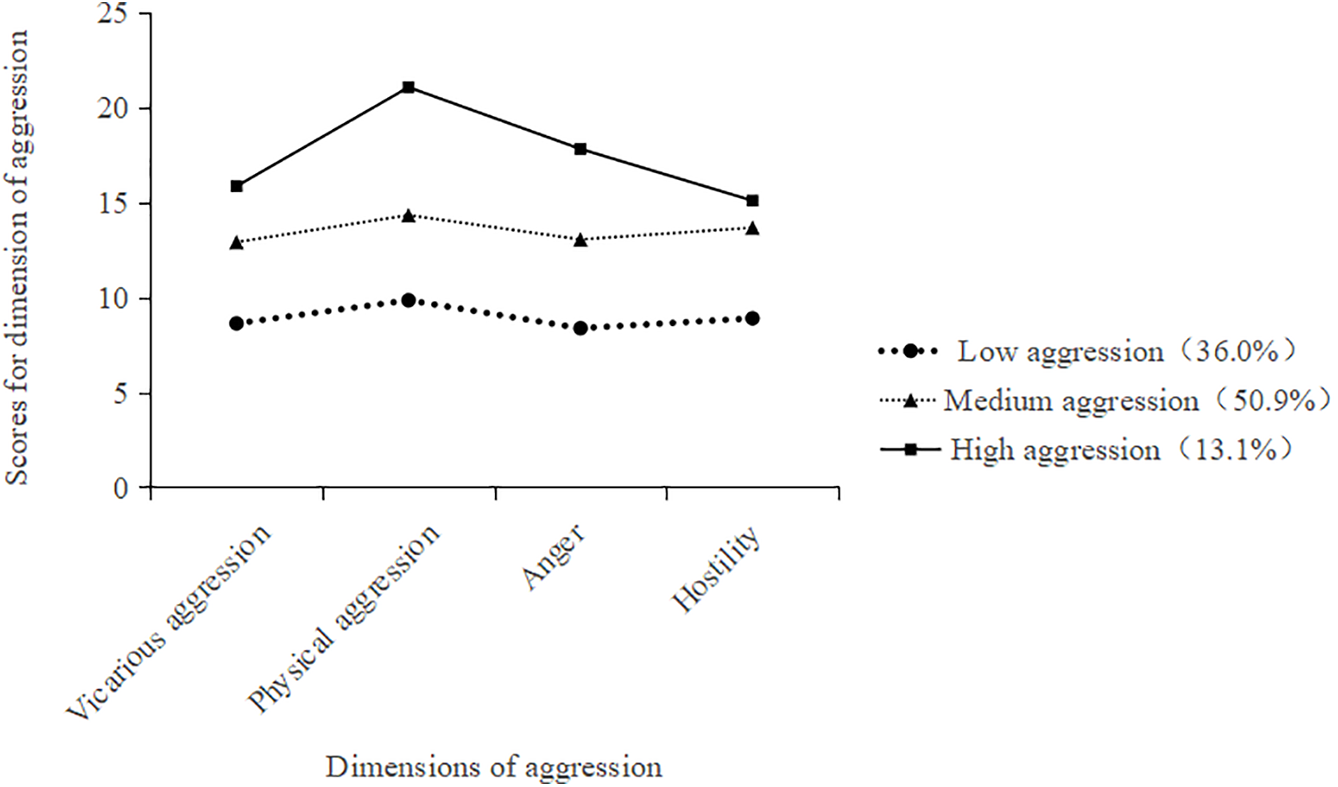

Further, Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparison showed that the high aggression class for rural boarding junior high school students scored the highest in the four dimensions of aggression, followed by the medium aggression class, and then the lowest in the low aggression class. The differences among the 3 classes were statistically significant; the results are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Scores of three latent profiles of aggressive behavior in the four dimensions of aggression in rural boarding junior school students

3.4 Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Latent Classes of Aggression and Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Moral Disengagement, and Preference for Solitude

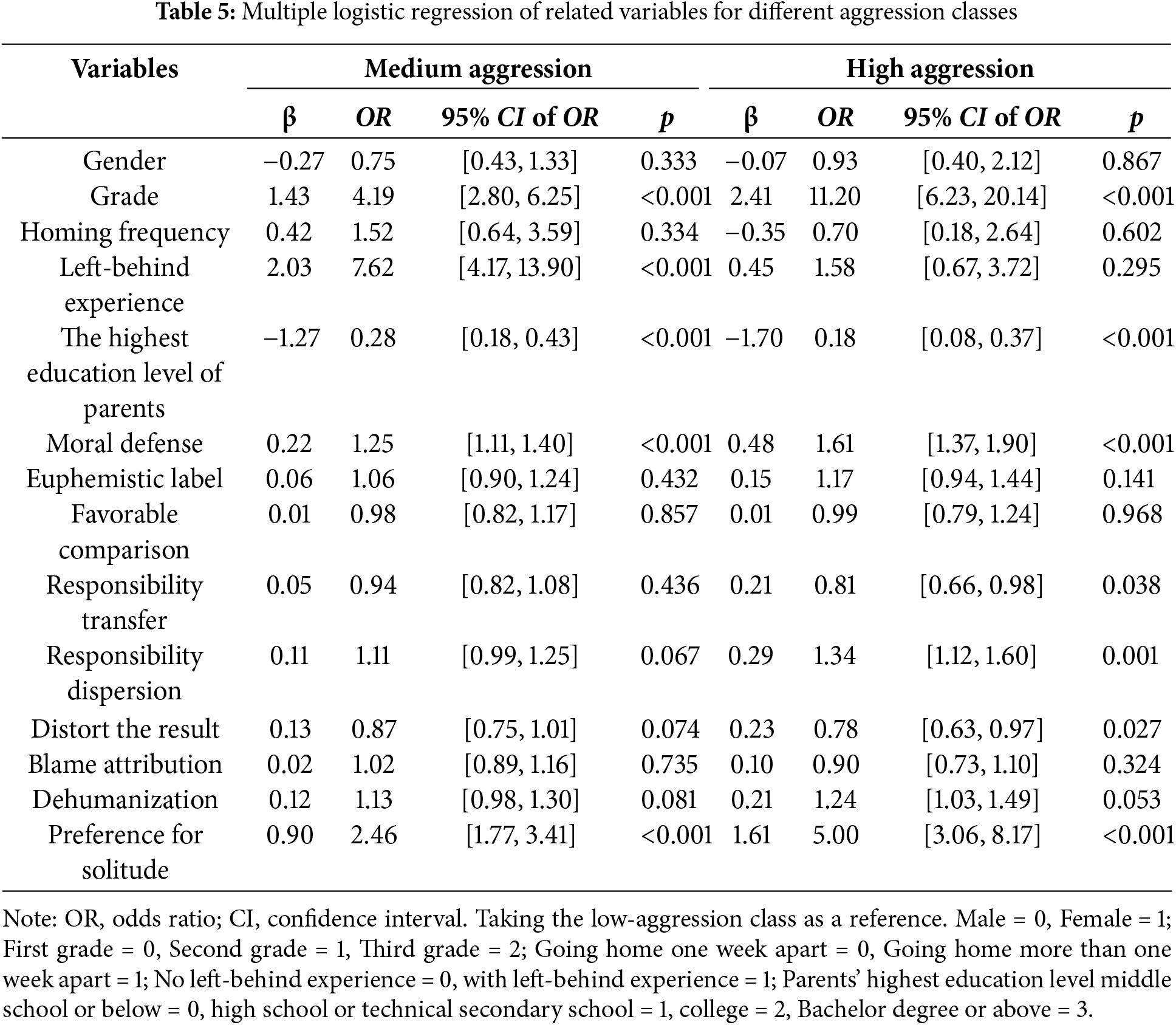

The three classes of LPA results were used as dependent variables; socio-demographic characteristics, moral disengagement, and preference for solitude were used as independent variables for logistic regression. The odds ratio (OR) coefficient is obtained by comparing the category “low aggression” as the benchmark. Logistic regression results are shown in Table 5. Compared with low aggression, Chinese rural boarding junior high school students with left-behind experience accounted for a larger proportion of the medium aggression class (β = 2.03, OR = 7.62). The higher the grade level, the greater the proportion of the sample in the medium (β = 1.43, OR = 4.19) and high aggression classes (β = 2.41, OR = 11.20). The lower the educational level of the parents, the greater the proportion of the medium (β = −1.27, OR = 0.28) and high aggression classes (β = −1.70, OR = 0.18). At the same time, students with high moral defense (β = 0.22/0.48, OR = 1.25/1.61) and preference for solitude (β = 0.90/1.61, OR = 2.46/5.00) are more likely to belong to medium aggression and high aggression. Students with high responsibility transfer (β = 0.21, OR = 0.81), responsibility dispersion (β = 0.29, OR = 1.34), and distorted results (β = 0.23, OR = 0.78) are more likely to be high aggression.

The current study used LPA to classify the types of aggression among rural boarding junior high school students based on their scores on four dimensions: vicarious aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. The results showed that there was significant group heterogeneity in rural boarding junior high school students’ aggression, which was divided into three main latent classes: low aggression (36.0%), medium aggression (50.9%), and high aggression (13.1%). In terms of the distribution of each type, the medium and high-aggression rural boarding junior high school students accounted for 64.0% of the total study subjects, which was 1.8 times more than the low-aggression students, indicating that a higher number of rural boarding junior high school students had some degree of aggression. Furthermore, a two-by-two comparison of the three latent classes of aggression among rural boarding junior high school students revealed that the scores on the four dimensions of aggression showed a descending pattern and significant differences between any two types. High-aggression students had the highest mean scores for both total and all dimensions of aggression and these students are prone to satisfy themselves by destroying objects and threatening others, and are more likely to use force to protect themselves in conflict situations. Consistent with the literature, high-aggression students have shown difficulty controlling their emotions when they encounter frustration and are often caught up in feelings of jealousy [48]. The results suggest that rural boarding schools should pay more attention to students’ aggression when conducting psychological surveys and offer additional support to students identified with higher aggression levels through screening results. When necessary, we should carry out intervention work aimed at their related problems, help them reasonably control their negative emotions, increase the vent of these emotions, timely reduce negative cognitions, and thus reduce their level of aggression [49,50].

Results from the multiple logistic regression analyses showed that demographic variables such as grade level, left-behind experience, and parental education were valid predictors of aggression classification among rural boarding junior high school students. The higher the grade level, the greater the likelihood of students being classified into the medium or high aggression profiles, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study [51]. This may be related to upper-grade students developing more mature perspective-taking skills than lower-grade students, allowing them to identify others’ intent to harm and respond aggressively [39]. That demonstrates, that research has also shown that seniors tend to face more academic stress than juniors and prior research has shown that academic stress can positively predict aggression [40]. It is evident that the cumulative academic pressure for a higher grade can be the major contributing factor to emotional distress, resulting in a higher demonstration of aggressive behavior. Thus, the higher the grade level of rural boarding junior high students, the more likely they are to have high aggression.

In addition, rural boarding junior high school students with a left-behind experience were more likely to be in the medium (vs. low) aggression class, a result consistent with previous research showing that left-behind students tend to exhibit more impulsive tendencies and aggressive behaviors than non-left-behind students [52]. According to ecosystem theory, the development of an individual is not isolated but exists in a series of interacting ecosystems, such as microsystems [53]. The family ecosystem is an important part of the microsystem and is particularly important for the healthy development of individuals [54]. Rural boarding junior high school students with left-behind experiences lack parent-child attachment and family education more than ordinary students resulting in serious impairment of their family system. It is not only detrimental to the construction of personality but also makes them lack the ability to handle emotions and more prone to excessive actions causing aggressive behaviors when solving problems or encountering conflicts [55,56]. In terms of parental education, rural boarding junior high school students with lower parental education are more likely to have medium and high aggression. This may be because parental education influences parenting style, with more educated parents tend to have a more positive approach, understanding, and respecting their children [57]. Conversely, parents with lower education levels may adopt a more negative parenting style, which is associated with higher aggression among rural boarding junior high school students [58]. In conclusion, early parent-child attachment and good family education are effective ways to prevent aggressive behavior problems among rural boarding junior high school students. Collaborative efforts from schools, society, educators, and parents are crucial for creating and providing a supportive developmental environment for rural boarding junior high students, in order to scientifically prevent problematic behaviors.

In addition, the results of the multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that not all dimensions of moral disengagement significantly associate with the aggression in rural boarding students. Specifically, only the dimensions of moral defense, responsibility transfer, responsibility dispersion, and distortion of results were found to have a significant impact on the potential level of aggression among rural boarding junior high school students. Previous variable-centered studies have predominantly focused on the overall level of moral disengagement in relation to aggression, showing that as the degree of moral disengagement increases, so does the likelihood of aggressive behavior. This aligns with the theory of moral disengagement, which posits that moral disengagement serves as a critical mechanism for alleviating psychological guilt and encourages individuals to engage in more aggressive behaviors [52,53]. In contrast, this study examined each dimension of moral disengagement and revealed that among rural boarding middle school students, the influence of each dimension on their aggressiveness varied. These students primarily rationalized their unethical behaviors and attributed responsibility for such actions to external factors or others. By diminishing personal accountability and distorting the consequences of immoral behavior in group settings, they justified aggressive actions that contravene their inherent moral standards, thereby increasing the probability of such behaviors occurring. Other dimensions of moral disengagement did not significantly affect the likelihood of aggressive behavior. This suggests that moral disengagement plays a pivotal role in intervening in the aggressive behaviors of rural boarding junior high school students [54], but its effectiveness depends on targeting specific dimensions such as moral defense, responsibility transfer, responsibility dispersion, and distortion of results.

It is worth noting that the current study found that solitary preference also influenced the latent classes of aggression among rural boarding junior high school students. Higher scores on solitary preference predicted a greater likelihood of aggressive behavior. A large number of researchers focusing on social withdrawal have argued that solitary behavior is a specific form of social withdrawal and can be classified as shyness [59,60]. Generally speaking, the preference for solitude depends on the individual’s internal motivation [61], with shy individuals having a tendency to avoid motivated internal conflict and often showing a strong willingness to interact as well as interaction anxiety [62]. Yet, solitary preference individuals show a low tendency to avoid motivation for interaction showing indifference to interpersonal interactions [63]. It follows that a preference for solitude as an internal motive often reflects strong social withdrawal in individuals. It has been found that social withdrawal positively predicts aggression in early adolescence [64], which to some extent supports the finding that preference for solitude, as a subtype of social withdrawal, is associated with the latent classes of aggression in this study. Chinese boarding students extend the existing literature with culturally grounded norms. In contrast with the different Western cultures, where solitude is often perceived as a normative or even healthy practice, Chinese culture strongly emphasizes social harmony. Because of this collectivism, Chinese culture views adolescents who prefer solitude or withdraw from social norms as social deviants or maladjusted individuals [65]. This leads to the common perception of their engagement in various internalizing and externalizing risk behaviors, including aggression. This culture-specific norm implies the significance of comprehending solitude behaviors through the lens of non-Western social dynamics [66]. The present study allows for the exploration of unique participants from Chinese rural boarding schools, which certainly extends the existing literature by highlighting the cultural norms and expectations connected with the social determinants of behavior that can determine the psychological risk factors of aggressive behavior.

5 Limitations and Future Directions of the Study

This present study presents some limitations that need to be addressed. First, the convenient sampling technique recruited a comparatively smaller number of students from 6 schools across 3 provinces of China, which narrows down the generalizability of the results to the broader population of rural boarding junior high school students in China. Second, the cross-sectional design of this study restricts the inference of causal relationships between the study variables. Therefore, in future studies, longitudinal tracking should be used to further explore the quasi-causal relationship between moral disengagement, preference for solitude, and aggression among rural boarding junior high students. Third, our study only used self-assessments via questionnaires to explore the explicit aggression of rural boarding junior high students, which may elicit with response bias. Fourth, this study solely recruited participants from Chinese rural boarding junior high school students, which may limit the generalizability for the excluded non-boarding students. Future research should comprise the observations from teachers and peers to highlight findings of aggression measurements. However, in view of the fact that implicit aggression is universally unconscious [67], future studies should continue to explore the classification of implicit aggression and related factors of rural boarding junior high school students. Furthermore, this study identified three aggressive profiles, and there is the possibility that further classes exist among the participants. However, the observed profiles highlight that higher aggressive behavior levels experience more negative outcomes. Additionally, integrating various other variables, including emotional regulation, peer dynamics, teacher-student relations, and institutional environment, may clarify the underlying mechanisms of aggressive behaviors among rural boarding students, with the inclusion of both boarding and non-boarding students. Moreover, future research should incorporate physical and mental health measures to explore the underlying mechanism of profile-based aggressive behavior to ensure broader well-being, since this present study was limited to concluding in that direction.

The study reveals three latent classes of aggression in Chinese rural boarding junior high school students, which are low, medium, and high aggression. Grade level, left-behind experience, and parents’ education level are the main socio-demographic characteristics that affect these latent classes. Moral disengagement and preference for solitude are also found to affect the latent classes. Chinese rural boarding junior high school students who score higher on moral disengagement and preference for solitude tend to be classified in the medium and high aggression classes. It is suggested that schools may reduce the level of moral disengagement and preference for solitude by using corresponding intervention methods (school-based socio-emotional learning, moral reasoning training, social and peer interaction skills, etc.), which could manage the aggression problems among rural boarding junior high school students.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the staff involved in data collection.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the General project of the “14th Five-Year Plan” of Education Science of Gansu Province in 2023: “Research on the Integration Strategy of Rural Primary School Labor Education and Other Disciplines under the Background of Rural Revitalization” (Project number: GS [2023]GHB1420), and Gansu Provincial University Curriculum Ideological and Political Demonstration Project “Exploration and Practice of Ideological and Political Courses in Pre-School Education Majors from the Perspective of Three Educations: A Case study of Pre-School Education History” (Project No.: GSkcsz-2021-094). No part of the study (design, data collection, and curation analysis, manuscript preparation or publication) was influenced by the funder.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yatong Li; methodology, Yatong Li and Wangqin Hu; software, Yatong Li and Wangqin Hu; validation, Yatong Li; formal analysis, Yatong Li; investigation, Yatong Li; resources, Wangqin Hu; data curation, Wangqin Hu; writing—original draft preparation, Yatong Li and Wangqin Hu; writing—review and editing, Yatong Li and Wangqin Hu; supervision, Yatong Li; project administration, Yatong Li; funding acquisition, Yatong Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwest Normal University (ERB Number 20220311, dated: 01 April 2022). It should be noted that the principal author, Yatong Li, obtained her doctoral degree from Northwest Normal University, and the study was registered during her studies at that institution. Since the participants were minors, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians prior to the survey. All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Barlett CP, Anderson CA. Direct and indirect relations between the Big 5 personality traits and aggressive and violent behavior. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;52(8):870–5. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Detullio D, Kennedy TD, Millen DH. Adolescent aggression and suicidality: a meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Behav. 2022;64(1):101576. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2021.101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cao L, Chen R. Secondary education (high school) in China. In: Education in China and the world. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 137–210. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-7415-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ebesutani C, Kim E, Young J. The role of violence exposure and negative affect in understanding child and adolescent aggression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2014;45(6):736–45. doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0442-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Goodearl AW, Salzinger S, Rosario M. The association between violence exposure and aggression and anxiety: the role of peer relationships in adaptation for middle school students. J Early Adolesc. 2014;34(3):311–38. doi:10.1177/0272431613489372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tong Y, Hu Y, Cheung NW. Life stage of boarding at school and middle school student victimization in rural China. Chin Sociol Rev. 2024;56(5):497–526. doi:10.1080/21620555.2024.2361643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Berryhill B, Carlson C, Hopson L, Culmer N, Williams N. Adolescent depression and anxiety treatment in rural schools: a systematic review. Rural Ment Health. 2022;46(1):13–27. doi:10.1037/rmh0000183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ren X, Lin C, Pan L, Fan Q, Wu D, He J, et al. The impact of parental absence on the mental health of middle school students in rural areas of Western China. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1439799. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1439799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang S, Dong X, Mao Y. The impact of boarding on campus on the social-emotional competence of left-behind children in rural western China. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2017;18(3):413–23. doi:10.1007/s12564-017-9476-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang LJ, Shen J, Li ZQ, Gai XS. A comparative research on the mental health status between boarding and non-boarding students in junior high school. Chin J Spec Educ. 2009;5:82–6. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2009.05.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang A, Medina A, Luo R, Shi Y, Yue A. To board or not to board: evidence from nutrition, health and education outcomes of students in rural China. China World Econ. 2016;24(3):52–66. doi:10.1111/cwe.12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang S, Zhang Y. A study on the relationship between self-control and bullying in rural boarding high school students. J Dali Uni. 2019;4(5):91–8. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2096-2266.2019.05.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gu J. Stay behind children’s differential educational performance: the impact of parental migration arrangements in China. Int J Educ Res Open. 2024;7(6):100364. doi:10.1016/j.ijedro.2024.100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li J, Huang J, Hu Z, Zhao X. Parent-child relationships and academic performance of college students: chain-mediating roles of gratitude and psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2022;13:794201. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.794201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Nguyen LV, Nguyen NHD, Truong HKT, Giang MTT. School problems among left-behind children of labor migrant parents: a study in Vietnam. Health Psychol Rep. 2022;10(4):266–79. doi:10.5114/hpr.2022.115657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao C, Wang F, Zhou X, Jiang M, Hesketh T. Impact of parental migration on psychosocial well-being of children left behind: a qualitative study in rural China. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):80. doi:10.1186/s12939-018-0795-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang F, Lin L, Xu M, Li L, Lu J, Zhou X. Mental health among left-behind children in rural China in relation to parent-child communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1855. doi:10.3390/ijerph16101855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Y, Shen Z, Liu W, Liu Y, Tang B. Will the situation of left-behind children improve when their parents Return? evidence from China. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2024;164(2):107856. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhuang J, Ng JCK, Wu Q. The role of parent–child communication on Chinese rural left-behind children’s educational expectation: a moderated mediation analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2025;12(1):1. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-04334-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bahmani T, Naseri NS, Fariborzi E. Relation of parenting child abuse based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions. Curr Psychol. 2022;42(15):12409–23. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02667-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lin Z, Zhou Z, Zhu L, Wu W. Parenting styles, empathy and aggressive behavior in preschool children: an examination of mediating mechanisms. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1243623. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1243623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shen J, Zhu Y, Zhang G. The relationship between parental adverse childhood experiences and offspring preschool readiness: the mediating role of psychological resilience. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):136. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02408-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bierman KL, Coie J, Dodge K, Greenberg M, Lochman J, McMohan R, et al. School outcomes of aggressive-disruptive children: prediction from kindergarten risk factors and impact of the fast track prevention program. Aggress Behav. 2013;39(2):114–30. doi:10.1002/ab.21467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen X, Chen J, Jiang H, Zhao H. Bullying victimization and mental health problems of boarding adolescents in rural China: the role of self-esteem and parenting styles. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):941. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-22043-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Thomas DE, Bierman KL, The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The impact of classroom aggression on the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(2):471–87. doi:10.1017/s0954579406060251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Gorter R, Fox JP, Eekhout I, Heymans MW, Twisk J. Missing item responses in latent growth analysis: item response theory versus classical test theory. Stat Methods Med Res. 2020;29(4):996–1014. doi:10.1177/0962280219897706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yin K, Peng J, Zhang J. Latent profile analysis in the field of organizational behavior. Adv Psychol Sci. 2020;28(7):1056–70. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2020.01056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Magidson J, Vermunt JK. Latent class models for clustering: a comparison with k-means. Can J Mark Res. 2002;20(3):36–43. [Google Scholar]

29. Zeng LP, Song X, Zhou Y, Tian DD, Zhu H. A latent profile analysis of social adaptation and related factors in relocated youths for poverty alleviation. Chin Ment Health J. 2021;35(9):726–32. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu J, Coplan RJ, Chen X, Li D, Ding X, Zhou Y. Unsociability and shyness in Chinese children: concurrent and predictive relations with indices of adjustment. Soc Dev. 2014;23(1):119–36. doi:10.1111/sode.12034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xu Y, Chen S, Ye Y, Wen W, Zhen R, Zhou X. Childhood neglect, depression, and academic burnout in left-behind children in China: understanding the roles of feelings of insecurity and self-esteem. Child Prot Pract. 2025;5(2):100168. doi:10.1016/j.chipro.2025.100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu CH. The influence of mindfulness and moral disengagement on the psychological health and willingness to work of civil servants experiencing compassion fatigue. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(4):2431–44. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00761-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liu J, Chen X, Coplan RJ, Ding X, Zarbatany L, Ellis W. Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2015;46(3):371–86. doi:10.1177/0022022114567537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Coplan RJ, Ooi LL, Nocita G. When one is company and two is a crowd: why some children prefer solitude. Child Dev Perspect. 2015;9(3):133–7. doi:10.1111/cdep.12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen X, Wang L, Cao R. Shyness-sensitivity and unsociability in rural Chinese children: relations with social, school, and psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 2011;82(5):1531–43. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01616.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhou DQ, Wang CY, Pan RY. The relationship between left-behind children’s preference for solitude and school adaptation: the mediating role of peer attachment. Psychol Res. 2021;14(2):184–90. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1159.2021.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Coplan RJ, Zheng S, Weeks M, Chen X. Young children’s perceptions of social withdrawal in China and Canada. Early Child Dev Care. 2012;182(5):591–607. doi:10.1080/03004430.2011.566328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yuan CY, Shao AH, Liang LC, Bian YF. Cross-lag analysis of unsociability, peer exclusion and peer victimization among adolescents and children. Psychol Dev Edu. 2014;30(1):16–23. (In Chinese). doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2014.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li X, Bian C, Chen Y, Huang J, Ma Y, Tang L, et al. Indirect aggression and parental attachment in early adolescence: examining the role of perspective taking and empathetic concern. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;86:499–503. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Keshi AK, Basavarajappa. The relationship of academic stress with aggression, depression, and academic performance of college students in Iran. I Manag J Educ Psychol. 2011;5(1):24–31. doi:10.26634/jpsy.5.1.1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Buchholz ES, Chinlund C. En route to a harmony of being: viewing aloneness as a need in development and child analytic work. Psychoanal Psychol. 1994;11(3):357–74. doi:10.1037/h0079555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(3):452–9. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu JS, Zhou Y, Gu WY. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of buss-perry aggression questionnaire in adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2009;17(4):449–51. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

44. Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(2):364–74. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yang JP, Wang XC. The influence of moral disengagement on adolescents’ aggressive behavior: moderating mediating effect. Acta Psychol Sin. 2012;44(8):1075–85. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.01075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Burger JM. Individual differences in preference for solitude. J Res Pers. 1995;29(1):85–108. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1995.1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Chen X, Song X, Huang X. Reliability and validity test of the Chinese version of the Solitude Preference Scale. Chin J Health Psychol. 2012;20(2):307–10. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

48. Potard C, Henry A, Pochon R, Kubiszewski V, Combes C, Brouté V, et al. Sex differences in the relationships between school bullying and executive functions in adolescence. J Sch Violence. 2021;20(4):483–98. doi:10.1080/15388220.2021.1956506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Kamper-DeMarco KE, Ostrov JM. Prospective associations between peer victimization and social-psychological adjustment problems in early childhood. Aggress Behav. 2017;43(5):471–82. doi:10.1002/ab.21705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhao Q, Li C. Victimized adolescents’ aggression in cliques with different victimization norms: the healthy context paradox or the peer contagion hypothesis? J Sch Psychol. 2022;92(1):66–79. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2022.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. He YS, Li HY, Feng L. A study on the developmental characteristics of aggression in middle school students. Psychol Dev Educ. 2006;22(2):57–63. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

52. Zhang C, Yang X, Xu W. Parenting style and aggression in Chinese undergraduates with left-behind experience: the mediating role of inferiority. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;126(1):106011. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Brouwers SA, van de Vijver FJR, Mishra RC. Cognitive development through schooling and everyday life: a natural experiment among Kharwar children in India. Int J Behav Dev. 2017;41(3):309–19. doi:10.1177/0165025416687410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Serpell ZN, Mashburn AJ. Family–school connectedness and children’s early social development. Soc Dev. 2012;21(1):21–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00623.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Fraser MW. Aggressive behavior in childhood and early adolescence: an ecological-developmental perspective on youth violence. Soc Work. 1996;41(4):347–61. doi:10.1093/sw/41.4.347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Fontaine RG. Applying systems principles to models of social information processing and aggressive behavior in youth. Aggress Violent Behav. 2006;11(1):64–76. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2005.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Anderson S, Cole S. The relationship between adolescent aggression, parenting style and family structure in urban inner city Jamaica. J Educ Dev Caribb. 2017;16(2):1–19. doi:10.46425/j011602y643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Lei H, Chiu MM, Cui Y, Zhou W, Li S. Parenting style and aggression: a meta-analysis of mainland Chinese children and youth. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;94(2):446–55. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60(1):141–71. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Stenseng F, Tingstad EB, Wichstrøm L, Skalicka V. Social withdrawal and academic achievement, intertwined over years? Bidirectional effects from primary to upper secondary school. Br J Educ Psychol. 2022;92(4):1354–65. doi:10.1111/bjep.12504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O’Neil K, Armer M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Dev Psychol. 2004;40(2):244–58. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Coplan RJ, Rose-Krasnor L, Weeks M, Kingsbury A, Kingsbury M, Bullock A. Alone is a crowd: social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(5):861–75. doi:10.1037/a0028861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Endo K, Ando S, Shimodera S, Yamasaki S, Usami S, Okazaki Y, et al. Preference for solitude, social isolation, suicidal ideation, and self-harm in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(2):187–91. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Xu Y, Zhou Y, Zhao J, Xuan Z, Li W, Han L, et al. The relationship between shyness and aggression in late childhood: the multiple mediation effects of parent-child conflict and self-control. Pers Individ Differ. 2021;182(3):111058. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Chen X. Socio-emotional development in Chinese children. In: Oxford handbook of chinese psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 37–52. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199541850.013.0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Chen X. Growing up in a collectivist culture: socialization and socioemotional development in Chinese children. In: Comunian AL, Gielen UP, editors. International perspectives on human development. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers; 2000. p. 331–53. [Google Scholar]

67. Galić Z, Ružojčić M, Jerneić Ž, Tonković Grabovac M. Disentangling the relationship between implicit aggressiveness and counterproductive work behaviors: the role of job attitudes. Hum Perform. 2018;31(2):77–96. doi:10.1080/08959285.2018.1455686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools