Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Influence of Self-Construal on Problematic Online Game Use among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediation of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction

1 Department of Sociology, School of Government, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

2 Department of Public Health, Shenzhen Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, Shenzhen Mental Health Center, Shenzhen Kangning Hospital,

Shenzhen, 518000, China

3 Center for Studies of Psychological Application, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Mental Health and Cognitive Science, School of Psychology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, 510631, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanshan Zhang. Email: ; Ruixiang Gao. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1399-1410. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.067138

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Fundamental internal factors like self-construal and its influence on problematic online game use (POGU) remain underexplored. Hence, this study aims to investigate the effects of independent and interdependent self-construal on POGU, with the mediation of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Methods: The study surveyed 418 Chinese junior high school students (50.24% male; Meanage = 12.68, SD = 0.65), assessing their levels of self-construal, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and POGU. A parallel mediation model was tested. Results: The findings showed that autonomy and competence needs satisfaction fully mediated the negative impact of independent self-construal on POGU (B = −0.052, p < 0.05; B = −0.094, p < 0.01, respectively), while interdependent self-construal and relatedness needs satisfaction did not have a significant effect on POGU (B = 0.005, p = 0.758). Additionally, while independent self-construal positively correlated with the satisfaction of all three psychological needs, interdependent self-construal only positively associated with relatedness need satisfaction (B = 0.152, p < 0.001). Conclusions: The study demonstrates that independent self-construal serves as a protective factor against POGU, mediated by autonomy and competence needs satisfaction, while the effects of interdependent self-construal are more complex. These insights highlight the need for tailored interventions that promote adaptive self-construal and psychological needs satisfaction among Chinese adolescents to prevent POGU.Keywords

Problematic online game use (POGU) has emerged as a significant global public health concern [1]. Notably, China has one of the highest adolescent POGU prevalence rates globally, ranging from 2.2% to 21.5% [1,2]. As a specific form of problematic Internet use, POGU is characterized by the uncontrollable, excessive, and compulsive engagement in online gaming, which leads to a range of negative outcomes in adolescents, including academic failure, low cognitive processing efficiency, depression, poor sleep quality, and even violent behavior [3–5]. Thus, it becomes crucial to investigate the underlying mechanisms of POGU and to develop targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Unmet psychological needs are key contributors to POGU [6]. However, most research focused on the environmental factors (e.g., parent-child relationships) that contribute to unmet psychological needs [7]. Internal factors in adolescents have received relatively less attention, despite the philosophical concept that “external factors exert influence through internal factors” [8]. For instance, addiction-related constructs have been studied in relation to internal factors like boredom, anxiety, self-control, etc. [9,10]. Nevertheless, these studies did not explore the essential mechanisms of adolescents’ variation in behavioral addiction; for example, they did not address why some adolescents experience greater boredom than others. It can be boldly assumed that more fundamental internal factors underlie these characteristics, which are likely related to how they construct their self-concept (i.e., self-construal). Therefore, this study aims to address this critical research gap by examining how different forms of self-construal influence POGU through the satisfaction of psychological needs.

1.1 Independent and Interdependent Self-Construal

Self serves as the foundation for both adaptive and maladaptive psychological processes. For centuries, psychologists have explored the concept of “self” from various perspectives and approaches. How individuals understand themselves directly shapes how they perceive and interpret the world and their relationship with it. Self-construal refers to how individuals define and make meaning of the self, specifically denoting whether people view the self as an independent entity distinct from others or as part of a broader social network, which was identified as independent self-construal (IndSC) and interdependent self-construal (InterSC) [11]. Individuals with a high level of IndSC, maintaining a consistent identity across contexts, are seen as mature; in contrast, individuals with a higher level of InterSC, their maturity is demonstrated by adapting behavior to maintain group harmony [11].

Initially, Markus and Kitayama introduced the concept of self-construal to develop a more comprehensive theory of self-concept from a cross-cultural perspective [11]. Early researchers on the self, primarily from European, Canadian, and European American backgrounds, generally viewed the self as autonomous, independent of others, and characterized by traits that are bounded, unique, and integrated, preceding social relationships and society itself [12]. As research on the self expanded to include more culturally diverse perspectives, scholars realized that this assumption did not adequately apply to East Asian societies. This realization led to the development of self-construal theory, which explicitly examines how culture shapes different types of self-concept [13].

Markus and Kitayama proposed that individuals with IndSC, typical of Western cultures, define themselves through stable internal traits and personal uniqueness, viewing relationships primarily in terms of personal benefit [11]. In contrast, those with InterSC, common in East Asian contexts, define the self through social roles and group affiliations [11]. For them, self-worth stems from fulfilling relational obligations and maintaining group harmony by adjusting behavior to situational demands [11]. Though individuals possess both independent and interdependent self-construals, cultural contexts tend to emphasize one type of self-construal more strongly [14]. However, with the increasing cultural integration [15], both independent and interdependent self-construals may significantly shape an individual’s self-concept within a given society. Hence, variations in self-construal also provide a valuable approach for investigating within-culture processes [13]. Moreover, given the “round outside and square inside” nature of the Junzi personality in traditional Chinese Zhongyong culture [16,17], both of these self-construals may yield significant yet distinct impacts on Chinese adolescents’ self-concept. The Zhongyong philosophy emphasizes a harmonious balance between flexibility and principle, encouraging individuals to adapt externally while maintaining an inner core of moral integrity and consistency [17]. This cultural ideal reflects a dynamic interplay between self-expression and social harmony, which aligns with the coexistence of independent and interdependent self-construals within the Chinese cultural context. Consequently, Chinese adolescents might simultaneously navigate the pursuit of personal uniqueness and social connectedness, shaping their self-concept in complex and culturally nuanced ways. Therefore, exploring the influence of self-construals on POGU among Chinese adolescents is crucial.

1.2 The Influence of Self-Construal on POGU

Decades of psychological studies have highlighted the crucial role of the self in human behaviors [18,19]. Cross et al. outline the roles of self-construal in shaping behavior across three dimensions: cognition, affect, and motivation [13], which elucidate the mechanisms through which self-construal influences POGU.

Cognitively, individuals with higher InterSC exhibit greater context sensitivity compared to those with higher IndSC, making them more responsive to environmental cues and social contexts [20]. This increased adaptability could positively link InterSC to POGU, as these individuals are more likely to engage deeply with online gaming due to its social nature, compared to their independent counterparts.

Affectively, existing studies have generally found that IndSC is linked to higher levels of subjective happiness and lower levels of depression, whereas InterSC tends to be associated with increased levels of these negative emotional states [21,22]. Given that numerous studies have identified impaired well-being, such as loneliness and anxiety [23,24], as precursors to POGU, it is plausible that InterSC positively influences POGU, while IndSC has a negative influence.

From the perspective of motivation and self-regulation, individuals with high IndSC prioritize personal goals. In contrast, those with high InterSC are primarily motivated by relational concerns [25]. This difference suggests that individuals with high IndSC are more likely to exercise self-discipline and avoid excessive online gaming, while those with high InterSC may be more inclined to seek social bonding through online games.

1.3 The Mediating Roles of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction

Similar to other factors influencing behavioral addiction, the effect of self-construal on POGU is likely mediated by the satisfaction of basic psychological needs [26–28]. According to Self-Determination Theory [29], human motivation and well-being fundamentally depend on the fulfillment of three innate psychological needs: autonomy (the need to experience volition and self-endorsement of actions), competence (the need to feel effective and capable in one’s activities), and relatedness (the need to feel connected and cared for by others). Extensive research has shown that deficits in satisfying these needs can contribute to maladaptive behaviors, including various forms of behavioral addiction [30–32]. Theoretically, when these needs are unmet, individuals may seek alternative means to fulfill them, such as excessive online gaming, which provides immediate but often unsustainable satisfaction. Empirical evidence from both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies corroborates the negative predictive role of basic psychological needs satisfaction on POGU, highlighting its critical function as a motivational mechanism underlying addictive gaming behaviors [33,34]. Thus, understanding how self-construal shapes need satisfaction offers valuable insights into the pathways leading to problematic gaming and informs targeted interventions. The relationship between self-construal (IndSC, InterSC) and POGU has not been fully explored. Markus and Kitayama suggested that individuals with high IndSC prioritize independence and self-actualization, which can satisfy autonomy and competence needs [11,35]. While autonomy and relatedness may seem contradictory, they can coexist, especially in East Asian cultures [36], such as among China’s “Little Emperors” [37]. IndSC individuals often balance autonomy and relatedness needs [37], as they may find it easier to fulfill relatedness needs through direct communication and conflict resolution [38,39]. Thus, IndSC is expected to be positively linked with relatedness need satisfaction.

In contrast, InterSC may hinder psychological needs satisfaction. Maintaining relationships and group harmony often requires sacrificing autonomy and uniqueness [13]. InterSC focuses on meeting group expectations, which may not support personal mastery or competence needs [40]. The emphasis on avoiding poor performance in front of others can undermine individual achievements, reducing competence satisfaction [41]. Moreover, while individuals with higher InterSC have stronger relatedness needs, these are harder to satisfy. Unlike those with high IndSC, who use active, promotion-focused strategies (e.g., voicing concerns), individuals with higher InterSC tend to adopt passive, prevention-focused strategies (e.g., waiting for improvement). This reliance on others’ willingness can create vulnerability and inconsistency in relatedness need satisfaction, potentially leading to need frustration. Thus, InterSC is likely to be negatively associated with satisfaction of all three basic psychological needs.

This study aims to explore how different forms of self-construal (independent and interdependent) influence POGU among Chinese adolescents, with basic psychological needs satisfaction (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) as mediators. Based on the analysis above, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: IndSC serves a protective role against POGU, while InterSC contributes to the development of POGU.

Hypothesis 2: basic psychological needs satisfaction mediates the negative association between IndSC and POGU, as well as the positive relationship between InterSC and POGU.

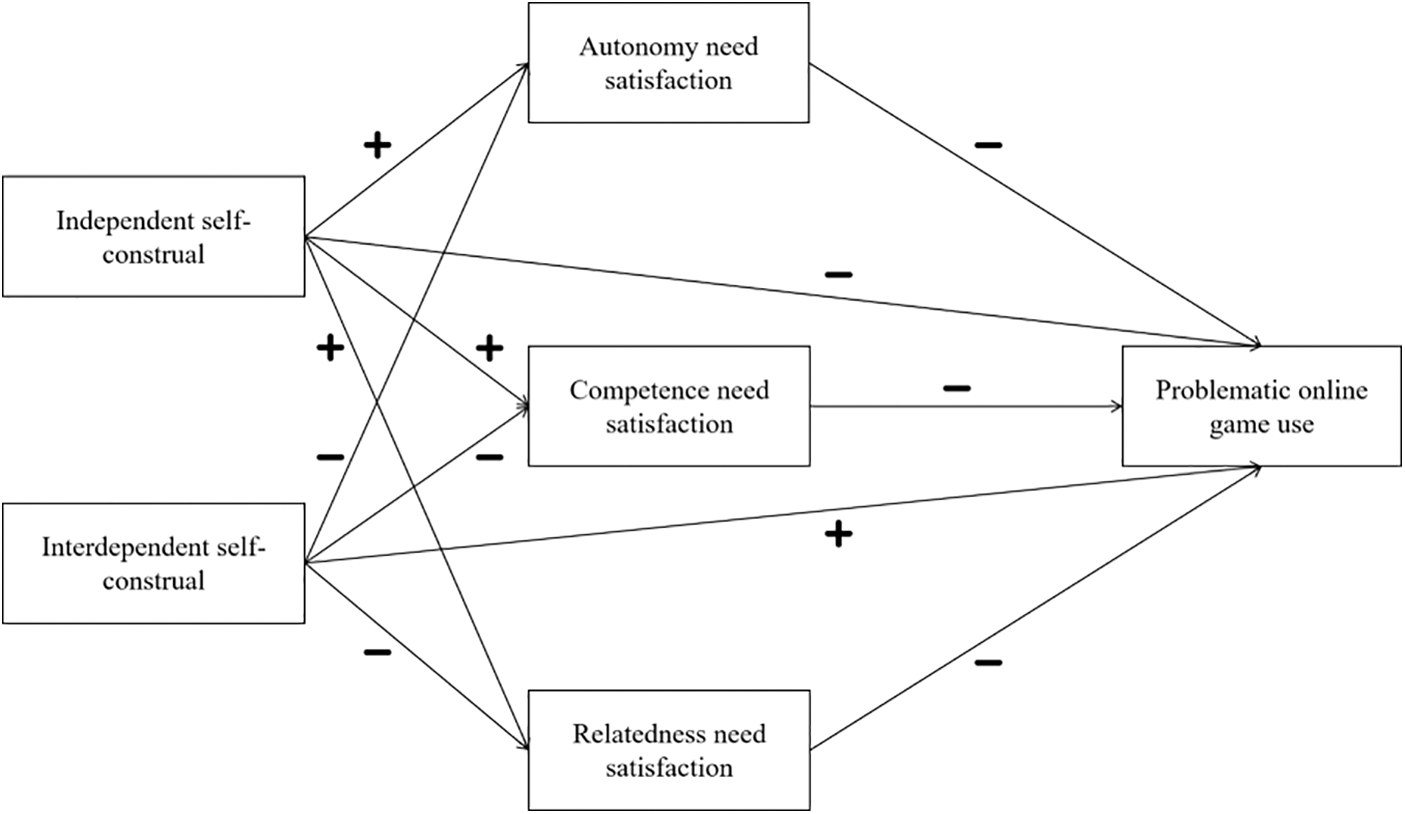

The research model, tested using a parallel mediation model, is shown in Fig. 1. The findings could inform more effective interventions and prevention strategies for POGU by promoting suitable self-concept development in Chinese adolescents.

Figure 1: The proposed research model. Note: In the figure, “+” indicates a positive correlation, and “−” indicates a negative correlation

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The final sample consisted of 418 Chinese junior high school students (50.24% male), with a mean age of 12.68 years (standard deviation [SD] = 0.65) and an age range of 11 to 15. A cross-sectional design was used, and data were collected via a paper-based questionnaire administered in classrooms. A trained postgraduate facilitated the survey in each class (40–50 students per class). After being briefed on the study’s purpose, precautions, and confidentiality, 453 students completed the questionnaire in 20 min. 35 responses were excluded due to a high number of unanswered items or identical responses. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University (No. 202300047) and adhered to the Helsinki Declaration (1975, revised 2000). Informed consent was obtained from students, head teachers, the grade moral education director, and the legal guardians of the students. All collected data were kept strictly confidential and anonymized to protect participants’ privacy. Personal identifiers were not recorded, and responses were coded to ensure anonymity during data analysis and reporting.

Self-construal was measured using the Self-Construal Scale for Middle School Students, a Chinese adaptation developed by Zhang as a revision of Singelis’s Self-Construal Scale [14,42]. It consists of 15 items (with no reverse-coded items), with 8 items assessing IndSC (e.g., “Individuality is important to me”) and 7 items assessing InterSC (e.g., “I feel happy when people around me are happy”). In this study, the scale employs a 7-point Likert scoring system (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) and McDonald’s ω are 0.752 and 0.804, respectively. Higher scores indicate higher levels of the corresponding type of self-construal.

2.2.2 Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction

This study used a 21-item Chinese version of the Basic Psychological Needs Scale [29,43]. The scale employs a 5-point Likert format (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) with nine items scored in reverse and comprises three subscales that assess the satisfaction of autonomy (e.g., “I can be myself in daily life”, McDonald’s ω = 0.745), competence (e.g., “I have mastered some interesting new skills recently”, McDonald’s ω = 0.761), and relatedness needs (“Generally, people are friendly to me”, McDonald’s ω = 0.867). Higher mean scores on each subscale indicate greater satisfaction of the respective psychological need.

The POGU Scale was utilized to measure the extent of POGU among the participants [44]. It consists of 20 items across five dimensions: Euphoria, Conflict, Health Problems, Preference for Virtual Relationships, and Loss of Self-Control. Sample items include “Playing online games is making my health worse” and “I am spending more and more time playing online games”. The scale was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “very unlike me” and 5 = “very like me”, overall McDonald’s ω = 0.913). Higher scores indicate a higher level of POGU.

Data analysis was conducted in two steps using SPSSAU, an online statistical software (https://spssau.com/indexs.html (accessed on 01 July 2025)). First, a preliminary analysis was performed, including descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and and Harman’s single-factor test to assess common method bias. Second, a formal analysis tested the proposed parallel mediation model using regression-based mediation analysis, and the significance of direct and indirect effects was evaluated using the Bootstrap method with 5000 resamples.

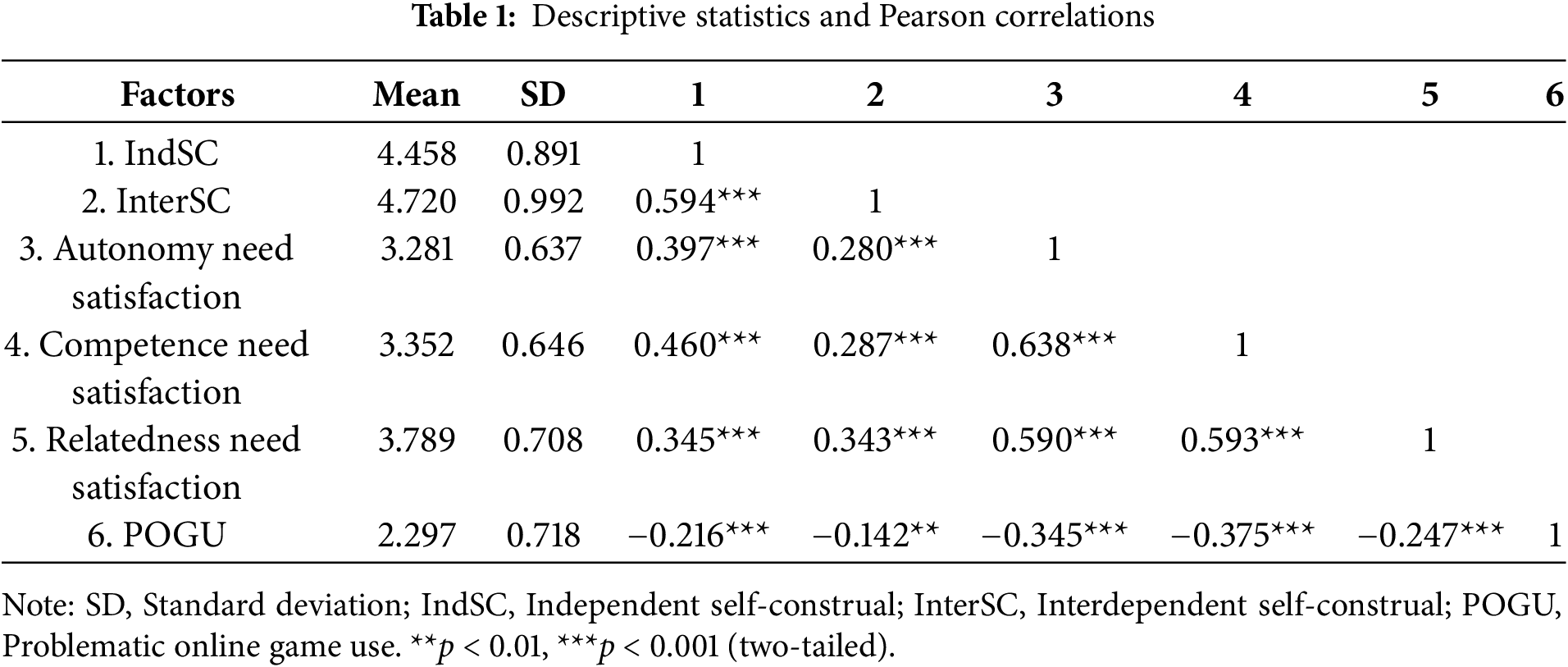

Table 1 presents the means, SDs, and correlation coefficients of the six variables studied. These preliminary results partially contradicted Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, as InterSC was found to have a positive (rather than negative) association with needs satisfaction and a negative (rather than positive) association with POGU. Additionally, we believe that there is no serious multicollinearity issue between the two predictor variables, IndSC and InterSC (r = 0.594, variance inflation factor [VIF] = 1.545, Tolerance = 0.647).

Moreover, given the potential limitations of self-report measures and the influence of the structured and supervised school setting, to minimize the influence of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. Results of EFA revealed that the cumulative variance explained by the first factor was 17.58%, indicating that common method bias in this study was not significant.

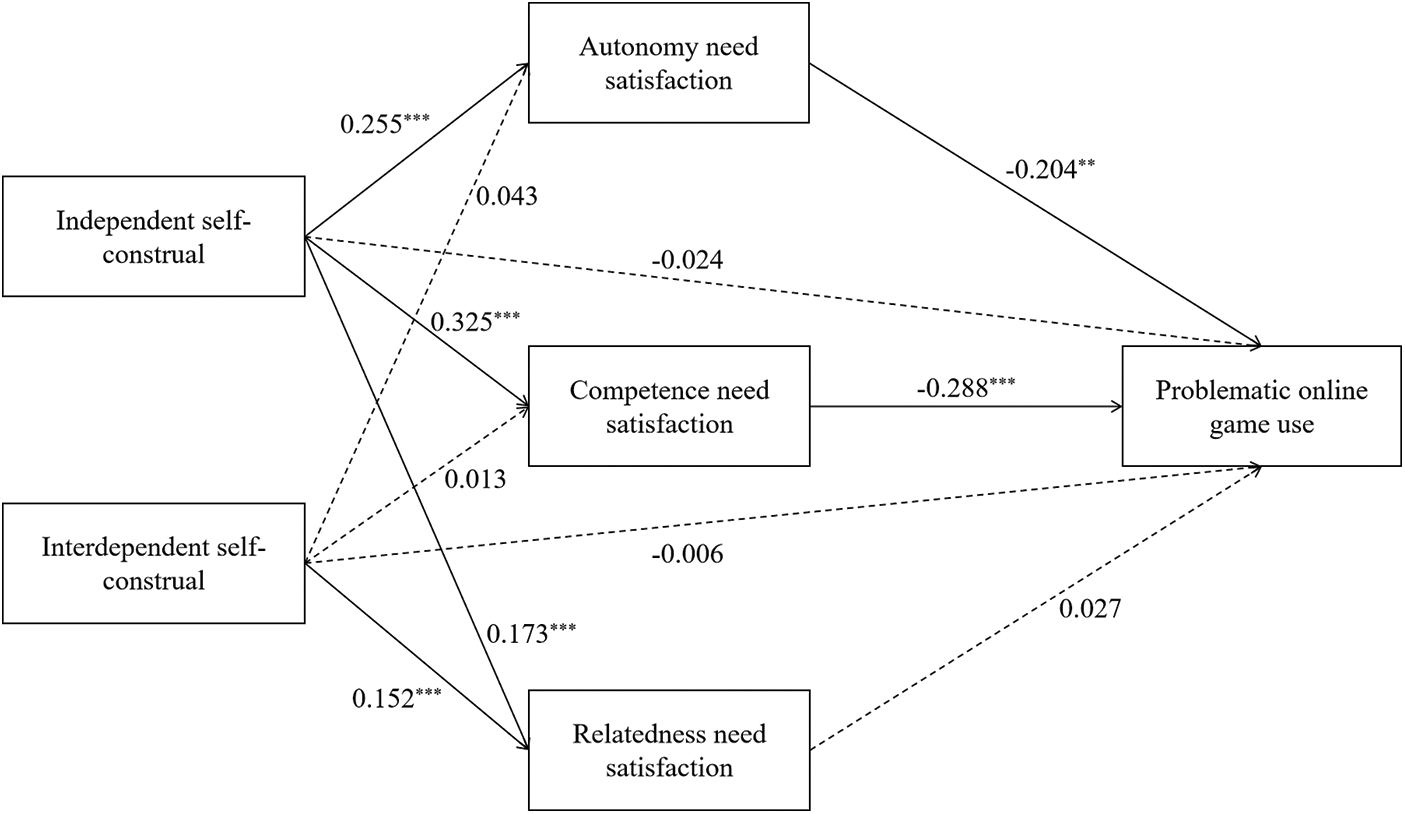

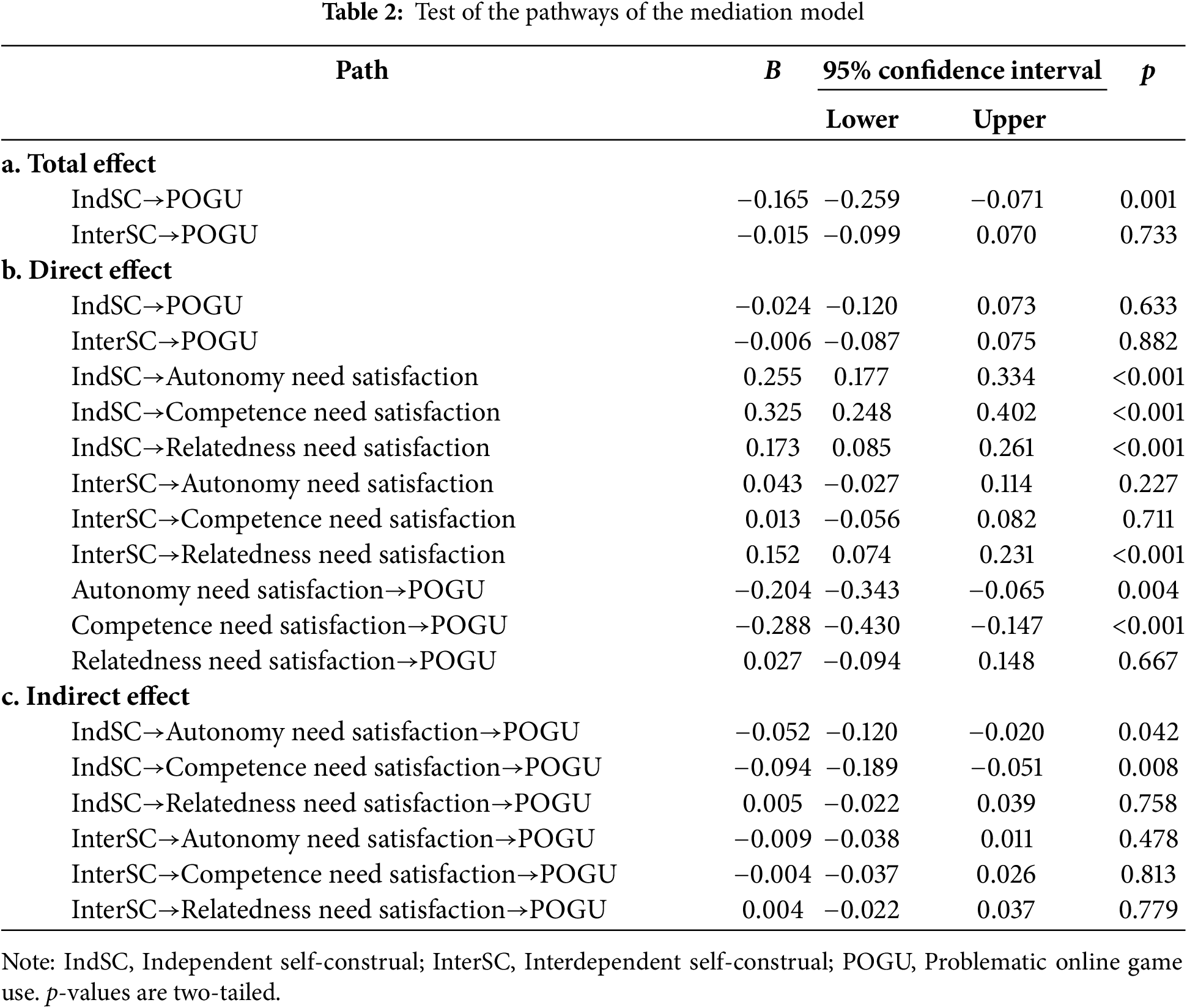

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, the negative effect of IndSC on POGU was fully mediated by autonomy (B = −0.052, 95% CI [−0.120, −0.020]) and competence need satisfaction (B = −0.094, 95% CI [−0.189, −0.051]), while the mediating effect of relatedness need satisfaction was not significant (B = 0.005, 95% CI [-0.022, 0.039]). Despite its positive association with relatedness need satisfaction (B = 0.152, 95% CI [0.074, 0.231]), InterSC did not show a significant direct effect on POGU (B = −0.006, 95% CI [−0.087, 0.075]), nor was this effect significantly mediated by autonomy (B = −0.009, 95% CI [−0.038, 0.011]), competence (B = −0.004, 95% CI [−0.037, 0.026]), or relatedness need satisfaction (B = 0.004, 95% CI [−0.022, 0.037]). These results provided only partial support for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2.

Figure 2: Test of the research model. Note: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed)

4.1 The Influence of Self-Construal on POGU

The first finding of this study concerns the influence of self-construal on POGU and provides only partial support for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. As expected, IndSC plays a significantly protective role against the development of POGU, aligning with numerous prior studies that suggest IndSC represents an adaptive self-concept development process associated with positive outcomes [21,22]. However, contrary to our maladaptive hypothesis, the effect of InterSC on POGU was found to be minimal (and still negative) or non-significant, suggesting that the mechanism through which InterSC influences POGU may be more complex than anticipated among Chinese adolescents. Possible explanations could be twofold: on one hand, the Chinese collectivist culture and the developmental stage of adolescence may justify the InterSC process of seeking social connections [13,15,45]. On the other hand, the maladaptive aspects of InterSC might be offset by its adaptive elements. For instance, while individuals with high InterSC are more prone to experiencing negative affect [22], a key precursor of POGU [23,24], they may also exhibit stronger abilities and greater willingness for self-regulation compared to those with high IndSC [46,47].

4.2 The Mediating Roles of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction

The second important finding of this study pertains to the mediating roles of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Partially consistent with our hypotheses, the satisfaction of autonomy and competence needs was significantly related to POGU in a negative manner; however, the relationship between relatedness need satisfaction and POGU was not significant. This nonsignificant result aligns with a previous finding on mobile phone addiction [30] but contradicts other studies [45]. This suggests that the association between relatedness need satisfaction and behavioral addiction may be complex. It can be inferred that although adolescents experience high levels of relatedness in real life, they may still seek an additional sense of relatedness in the virtual world. One possible explanation lies in the concept of parasocial relationships—one-sided, imagined interactions with virtual characters or avatars that simulate social engagement without the demands of real-life relationships [48,49]. In online gaming contexts, players often form parasocial bonds with in-game characters or fellow players, experiencing a sense of connection that is emotionally rewarding but qualitatively different from real-life relationships [50]. Thus, even when their real-world relatedness needs are met, adolescents may still turn to virtual platforms to fulfill a different kind of social experience—one that is more controlled, less risky, or more aligned with their identity needs. This may explain why relatedness needs satisfaction does not exert a significant protective effect against POGU.

The relationships between self-construal and basic psychological needs satisfaction were found to be mixed. IndSC was found to be significantly associated with the satisfaction of all three types of needs in a positive manner, which was consistent with our hypotheses. These outcomes are understandable, considering the adaptive roles of IndSC discussed earlier. In contrast, InterSC was only significantly associated with relatedness need satisfaction in a positive manner, while its relationships with autonomy and competence needs satisfaction were not significant, both of which were contrary to Hypothesis 2. The significantly positive relationship between InterSC and relatedness need satisfaction is not surprising, given the nature of InterSC, which emphasizes seeking and maintaining relationships [11,13]. The nonsignificant associations between InterSC and the satisfaction of autonomy and competence needs suggest more intricate mechanisms at play. On the one hand, while the pursuit of relational harmony may affect the satisfaction of autonomy needs, the two can still be compatible and coexist [36,37]. On the other hand, while self-enhancement motivation is primarily driven by IndSC, the desire to be a good group member in InterSC also necessitates self-improvement, which can contribute to a sense of competence, such as feeling capable of meeting the group’s expectations [51].

The results of the mediation analysis, along with the unexpected findings from the correlational analysis showing positive associations between InterSC and basic psychological needs, as well as a negative association with POGU, suggest that future research should adopt longitudinal designs and incorporate additional key variables to further explore the directionality and potential reciprocal nature of the relationships among InterSC, psychological needs satisfaction, and POGU.

From a practical perspective, our findings provide insights for developing more effective intervention and prevention strategies for POGU among Chinese adolescents. Specifically, promoting IndSC may serve as a protective factor, reducing adolescents’ vulnerability to POGU by fostering the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. This suggests that self-concept development programs in schools should emphasize autonomy-supportive environments and encourage personal goal-setting [33]. Moreover, given that InterSC was positively associated with relatedness needs but showed complex effects on POGU, interventions should focus on enhancing adolescents’ self-regulation skills and helping them manage social pressures more effectively. Specifically, interventions directly targeting self-concept (e.g., self-affirmation exercises) and positive feedback from significant others have been shown to effectively enhance adolescents’ self-concept [52], which may in turn reduce their tendency toward POGU. Incorporating elements of self-determination theory into educational practices can also contribute to a more balanced psychological development, addressing the diverse needs of Chinese adolescents. For example, previous educational programs in school settings have shown that teachers can support students’ competence needs by helping them complete academic tasks during individual mentoring sessions; fulfill their relatedness needs by discussing personal matters such as interpersonal relationships and family issues, thereby fostering positive social connections; and enhance their sense of autonomy by guiding them to reflect on classroom behavior, self-regulation strategies, and future learning paths, allowing them to experience choice and agency in decision-making [53].

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Second, the sample was limited to the students from one Chinese junior high school, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Third, while this study focused on self-construal as a fundamental internal factor, other individual characteristics may also play a role in POGU development and should be examined in future research. Fourth, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce response bias and limit the study’s validity. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs and multi-informant approaches, consider cultural contexts, and examine individual factors such as self-control, coping strategies, and personality traits to gain a more comprehensive understanding of POGU development.

This study contributes to an initial understanding of how different forms of self-construal influence POGU among Chinese adolescents, mediated by basic psychological needs satisfaction. The findings suggest that IndSC serves as a protective factor, while the effects of InterSC on POGU are more nuanced. Specifically, we revealed the following significant direct and indirect effects: (1) IndSC→Autonomy need satisfaction→POGU; (2) IndSC→Competence need satisfaction→POGU; (3) IndSC→Relateness need satisfaction; (4) InterSC→Relateness need satisfaction. The study underscores the importance of addressing self-concept development in interventions for adolescent POGU, emphasizing the role of psychological needs satisfaction, especially autonomy and competence.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The current research was supported by The National Social Science Fund of China (24ASH013).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception, design, and data collection: Qiufeng Gao and Yushu Feng; data analyis and original draft preparation: Ruixiang Gao; manuscript revision: Changcheng Jiang and Yanshan Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University (No. 202300047) and adhered to the Helsinki Declaration (1975, revised 2000). Informed consent was obtained from students, head teachers, the grade moral education director, and the legal guardians of the students.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Griffiths MD, Király O, Pontes HM, Demetrovics Z. An overview of pathological gaming. In: Aboujaoude E, Starcevic V, editors. Mental health in the digital age: grave dangers, great promise. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

2. Zuo B, Ma H. A research on the present situation of adolescent online game addiction: based on the survey of ten provinces and cities. J Cent China Norm Univ. 2010;49:117–22. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-2456.2010.04.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. De Rosa O, Baker FC, Barresi G, Conte F, Ficca G, de Zambotti M. Video gaming and sleep in adults: a systematic review. Sleep Med. 2024;124(12):91–105. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2024.09.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu S, Zhuang Y, Lee P, Li JCM, Wong PW. Leisure and problem gaming behaviors among children and adolescents during school closures caused by COVID-19 in Hong Kong: quantitative cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Serious Games. 2021;9(2):e26808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Mancone S, Tosti B, Corrado S, Diotaiuti P. Effects of video game immersion and task interference on cognitive performance: a study on immediate and delayed recall and recognition accuracy. PeerJ. 2024;12(2):e18195. doi:10.7717/peerj.18195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhao Z, Zhao M, Wang R, Pan H, Li L, Luo H. The effects of negative life events on college students’ problematic online gaming use: a chain-mediated model of boredom proneness regulation. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1426559. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1426559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gao Q, Jia G, Fu E, Olufadi Y, Huang Y. A configurational investigation of smartphone use disorder among adolescents in three educational levels. Addict Behav. 2020;103(5):106231. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Li D. Multiple ecological risk factors and adolescent social adaptation: risk modeling and mechanism research [master’s thesis]. Guangzhou, China: South China Normal University; 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Inzlicht M, Werner KM, Briskin JL, Roberts BW. Integrating models of self-regulation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2021;72(1):319–45. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-061020-105721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Li S, Ren P, Chiu MM, Wang C, Lei H. The relationship between self-control and internet addiction among students: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:735755. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.735755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–53. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shiraev EB, Levy DA. Cross-cultural psychology: critical thinking and contemporary applications. 7th ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. Cross SE, Hardin EE, Gercek-Swing B. The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(2):142–79. doi:10.1177/1088868310373752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Singelis TM. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1994;20(5):580–91. doi:10.1177/0146167294205014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao R, Huang S, Yao Y, Liu X, Zhou Y, Zhang S, et al. Understanding zhongyong using a zhongyong approach: re-examining the nonlinear relationship between creativity and the Confucian doctrine of the mean. Front Psychol. 2022;13:903411. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Gao R, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zeng J, Wu D, Huang X, et al. A sustainability lens on the paradox of Chinese learners: four studies on Chinese students’ learning concepts under Li’s “virtue–mind” framework. Sustainability. 2022;14(6):3334. doi:10.3390/su14063334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ge X, Hou Y. Confucian ideal personality traits (Junzi personality) and mental health: the serial mediating roles of self-control and authenticity. Acta Psychol Sin. 2021;53(4):374–86. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.00374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Crocetti E, Albarello F, Meeus W, Rubini M. Identities: a developmental social-psychological perspective. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2023;34(1):161–201. doi:10.1080/10463283.2022.2104987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Markus H, Wurf E. The dynamic self-concept: a social psychological perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 1987;38(1):299–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.38.020187.001503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Haberstroh S, Oyserman D, Schwarz N, Kühnen U, Ji L. Is the interdependent self more sensitive to question context than the independent self? Self-construal and the observation of conversational norms. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;38(3):323–9. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Elliott I, Coker S. Independent self-construal, self-reflection, and self-rumination: a path model for predicting happiness. Aust J Psychol. 2008;60(3):127–34. doi:10.1080/00049530701447368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Okazaki S. Sources of ethnic differences between Asian American and White American college students on measures of depression and social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106(1):52–60. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gao B, Cai Y, Zhao C, Qian Y, Zheng R, Liu C. Longitudinal associations between loneliness and online game addiction among undergraduates: a moderated mediation model. Acta Psychol. 2024;243(9):104134. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Meng Y, Shi X, Cai D, Ran M, Ye A, Qiu C. Prevalence, predictive factors, and impacts of internet gaming disorder among adolescents: a population-based longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2024;362(3):356–62. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2024.06.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. van Baaren RB, Maddux WW, Chartrand TL, de Bouter C, van Knippenberg A. It takes two to mimic: behavioral consequences of self-construals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):1093–103. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Király O, Koncz P, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Gaming disorder: a summary of its characteristics and aetiology. Compr Psychiatry. 2023;122:152376. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Vuorinen I, Savolainen I, Hagfors H, Oksanen A. Basic psychological needs in gambling and gaming problems. Addict Behav Rep. 2022;16(11):100445. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Larrieu M, Billieux J, Decamps G. Problematic gaming and quality of life in online competitive videogame players: identification of motivational profiles. Addict Behav. 2022;133(3):107363. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ryan RM. The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Gao Q, Zheng H, Sun R, Lu S. Parent-adolescent relationships, peer relationships, and adolescent mobile phone addiction: the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Addict Behav. 2022;129(2):107260. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Sun R, Gao Q, Xiang Y, Chen T, Liu T, Chen Q. Parent-child relationships and mobile phone addiction tendency among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction and the moderating role of peer relationships. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116(2):105113. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hong W, Liu RD, Oei TP, Zhen R, Jiang S, Sheng X. The mediating and moderating roles of social anxiety and relatedness need satisfaction on the relationship between shyness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2019;93(6):301–8. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yu C, Li X, Zhang W. Predicting adolescent problematic online game use from teacher autonomy support, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and school engagement: a 2-year longitudinal study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(4):228–33. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Shen CX, Liu RD, Wang D. Why are children attracted to the Internet? The role of need satisfaction perceived online and perceived in daily real life. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(1):185–92. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Gore JS, Cross SE. Pursuing goals for us: relationally autonomous reasons in long-term goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(5):848–61. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kagitcibasi C. Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: implications for self and family. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2005;36(4):403–22. doi:10.1177/0022022105275959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Shen J, Jia J, Wang L, Fang X. Autonomy-relatedness patterns and their association with academic and psychological adjustment among Chinese adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(6):1272–86. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01745-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Oetzel JG. Explaining individual communication processes in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups through individualism-collectivism and self-construal. Hum Commun Res. 1998;25(2):202–24. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1998.tb00443.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Singelis TM, Brown WJ. Culture, self, and collectivist communication: linking culture to individual behavior. Hum Commun Res. 1995;21(3):354–89. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1995.tb00351.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):482–97. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Mouratidis A, Vansteenkiste M, Michou A, Lens W. Perceived structure and achievement goals as predictors of students’ self-regulated learning and affect and the mediating role of competence need satisfaction. Learn Individ Differ. 2013;23(2–3):179–86. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2012.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang Y. Research on the relationship among interdependent self-construal, self-esteem and negative emotions for junior middle school students [master’s thesis]. Lanzhou, China: Northwest Normal University; 2012. (In Chinese). doi: 10.7666/d.D288601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Liu JS, Lin LL, Lv Y, Wei CB, Zhou Y, Chen XY. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the basic psychological needs scale. J Chin Ment Health. 2013;27(9):702–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

44. Kim MG, Kim J. Cross-validation of reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity for the problematic online game use scale. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26(3):389–98. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kaya A, Türk N, Batmaz H, Griffiths MD. Online gaming addiction and basic psychological needs among adolescents: the mediating roles of meaning in life and responsibility. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2024;22(4):2413–37. doi:10.1007/s11469-022-00994-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Self-regulation and the executive function of the self. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of self and identity. 1st ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2003. p. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

47. Seeley EA, Gardner WL. The “selfless” and self-regulation: the role of chronic other-orientation in averting self-regulatory depletion. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):103–17. doi:10.1080/15298860309034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hoffner CA, Bond BJ. Parasocial relationships, social media, and well-being. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45(1):101306. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Sherrick B, Hoewe J, Ewoldsen DR. Using narrative media to satisfy intrinsic needs: connecting parasocial relationships, retrospective imaginative involvement, and self-determination theory. Psychol Pop Media. 2022;11(3):266. doi:10.1037/ppm0000358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kreissl J, Possler D, Klimmt C. Engagement with the gurus of gaming culture: parasocial relationships to let’s players. Games Cult. 2021;16(8):1021–43. doi:10.1177/15554120211005241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kurman J. Self-enhancement: is it restricted to individualistic cultures? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27(12):1705–16. doi:10.1177/01461672012712013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. O’Mara AJ, Marsh HW, Craven RG, Debus RL. Do self-concept interventions make a difference? A synergistic blend of construct validation and meta-analysis. Educ Psychol. 2006;41(3):181–206. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4103_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Simões F, Alarcão M. Promoting well-being in school-based mentoring through basic psychological needs support: does it really count? J Happiness Stud. 2014;15(2):407–24. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9428-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools