Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of Duration Since Cancer Diagnosis and Anxiety or Depression on the Utilization of Korean Medicine

1 Division of Humanities and Social Medicine, the School of Korean Medicine, Pusan National University, Yangsan, 50612, Republic of Korea

2 College of Korean Medicine, Dongshin University, Naju, 58245, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Dongsu Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Evidence-based Approaches to Managing Stress, Depression, Anxiety, and Suicide)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1353-1367. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.067407

Received 02 May 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Patients with cancer are confronted not only with physical changes and pain but also with significant psychological challenges, including distress, anxiety, and depression, as a consequence of their diagnosis and treatment. This study aimed to identify the factors influencing anxiety or depression in patients with cancer, examine the relationship between the duration since cancer diagnosis and psychological state, and explore the association between these factors and the use of Korean medicine (KM). Methods: This study utilized data from the 2018 Korea Health Panel spanning 2008 to 2018. The analysis focused on adult participants (aged 19 and above) diagnosed with cancer who responded to their psychological state (i.e., anxiety or depression) and the duration since their cancer diagnosis. The dependent variables were the presence of anxiety or depression and the utilization of KM. Descriptive statistics and multiple logistic regression analysis were used to investigate factors influencing these variables. Results: A total of 773 participants were included in the final analysis, of whom 214 reported prior KM experience. Multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that the likelihood of experiencing anxiety or depression decreased as the duration since cancer diagnosis increased. Factors associated with anxiety or depression in patients with cancer included sex (odds ratio [OR] = 2.06), number of chronic diseases (OR = 1.17), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (CCI score of 2: OR = 1.60), and EQ-5D (EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire) index (OR < 0.001). Cancer patients without anxiety or depression were more likely to use KM if they had been diagnosed within three years, were female (OR = 2.11), and had a higher number of chronic conditions (OR = 1.20). In contrast, patients with anxiety or depression were more likely to utilize KM if they had been diagnosed for more than five years (OR = 6.30) and resided in urban areas. Conclusions: The results suggest that patterns of KM utilization among patients with cancer are associated with their psychological state. Future research should focus on identifying direct correlations between psychological factors and KM use in patients with cancer.Keywords

Patients with cancer not only experience physical pain during the treatment process but are also confronted with psychological stressors such as fear of metastasis or death, uncertainty about complete remission, and concerns about recurrence, all of which act as psychological sources of anxiety and depression [1,2]. Physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and nausea can also increase patients’ levels of anxiety and depression, highlighting the need for diverse palliative treatments across multiple dimensions for cancer patients [3,4]. The cancer diagnosis process itself induces psychological stress, which is known to potentially lead to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression [5]. Due to uncertainties related to treatment and physical changes, patients with cancer often experience emotional difficulties, which can affect their adherence to treatment and overall resilience [6]. Ultimately, mental health problems in patients with cancer are linked to a decline in their overall quality of life [7], and they may also induce physiological changes, such as weakened immune function and increased inflammatory responses, potentially leading to negative outcomes in survival rates [8,9].

In this context, cancer patients expect both direct and indirect positive effects from their treatment through the use of traditional medicine (TM) and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to manage cancer symptoms, alleviate treatment side effects, and improve emotional well-being [10,11]. Specifically, non-pharmacological approaches such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy and light therapy have been found to positively influence the psychological well-being of cancer patients [12–14], while treatments such as acupuncture, moxibustion, and herbal medicine have been shown not only to alleviate physical symptoms and to provide psychological stability, thereby enhancing quality of life [15–17]. However, most existing studies on Korean medicine (KM) for cancer have primarily focused on its effectiveness in managing physical symptoms, such as cancer treatment side effects, pain management, and immune enhancement [18]. Consequently, research on how KM affects the psychological state of patients with cancer is relatively limited, and studies on patterns of KM utilization among patients with cancer experiencing anxiety or depression are scarce.

Previous research on cancer patients’ utilization of TM has primarily analyzed the current usage status of TM or CAM [19,20], explored factors influencing TM or CAM usage [21–23], and, among these, focused on socioeconomic factors to establish correlations with TM usage [24,25]. These studies have generally been conducted without considering the psychological conditions of cancer patients and their impact on healthcare utilization. Therefore, there is a lack of research on whether there are changes in KM utilization over time following cancer diagnosis, how cancer patients with psychological conditions such as anxiety or depression utilize KM, and what factors influence their utilization of KM.

Thus, the primary aim of this study was to explore the relationship between the duration since cancer diagnosis, anxiety or depression, and KM utilization among patients with cancer. Specifically, the study aimed to (1) identify the factors associated with anxiety or depression in cancer patients and the factors related to KM utilization; (2) examine the relationship between the duration since cancer diagnosis, anxiety or depression, and KM utilization; and (3) analyze the correlation between anxiety or depression and KM utilization, as well as the factors that associated with this relationship. Ultimately, this study sought to provide insights that could positively affect cancer patients’ quality of life.

The Korea Health Panel (KHP) is a statistical dataset jointly surveyed and compiled by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) and the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) through the establishment of the KHP Consortium to provide foundational information for the formulation of national health and medical policies. This enables an in-depth analysis of medical utilization patterns, medical expenditure levels, and factors influencing medical utilization and expenditure based on individual and household characteristics [26,27]. This study utilized the 2018 data from the first phase of the KHP, “Korea Health Panel 2008–2018 Annual Data (Version 1.7)” [28]. Although the second phase of the KHP survey Health Panel Survey includes more recent data, it was difficult to confirm the period of cancer diagnosis. Therefore, we utilized 2018 data from the first phase, the most recent year available.

The first wave of the KHP used a probability-proportional two-stage stratified cluster sampling method with a population frame based on 90% of the census data. To maintain a certain number of sample households, an additional 2500 households were sampled in 2012 after the initial sampling of 8000 households in 2007, taking into account sample attrition rates. Therefore, the KHP data represent a sample of the Korean population. The survey method involved collecting health household records, receipts, and year-end tax settlement data from panel households over one year. Surveyors visit households to verify the collected data and conduct face-to-face interviews to complete the survey, which forms the basis for the annual data [26,27].

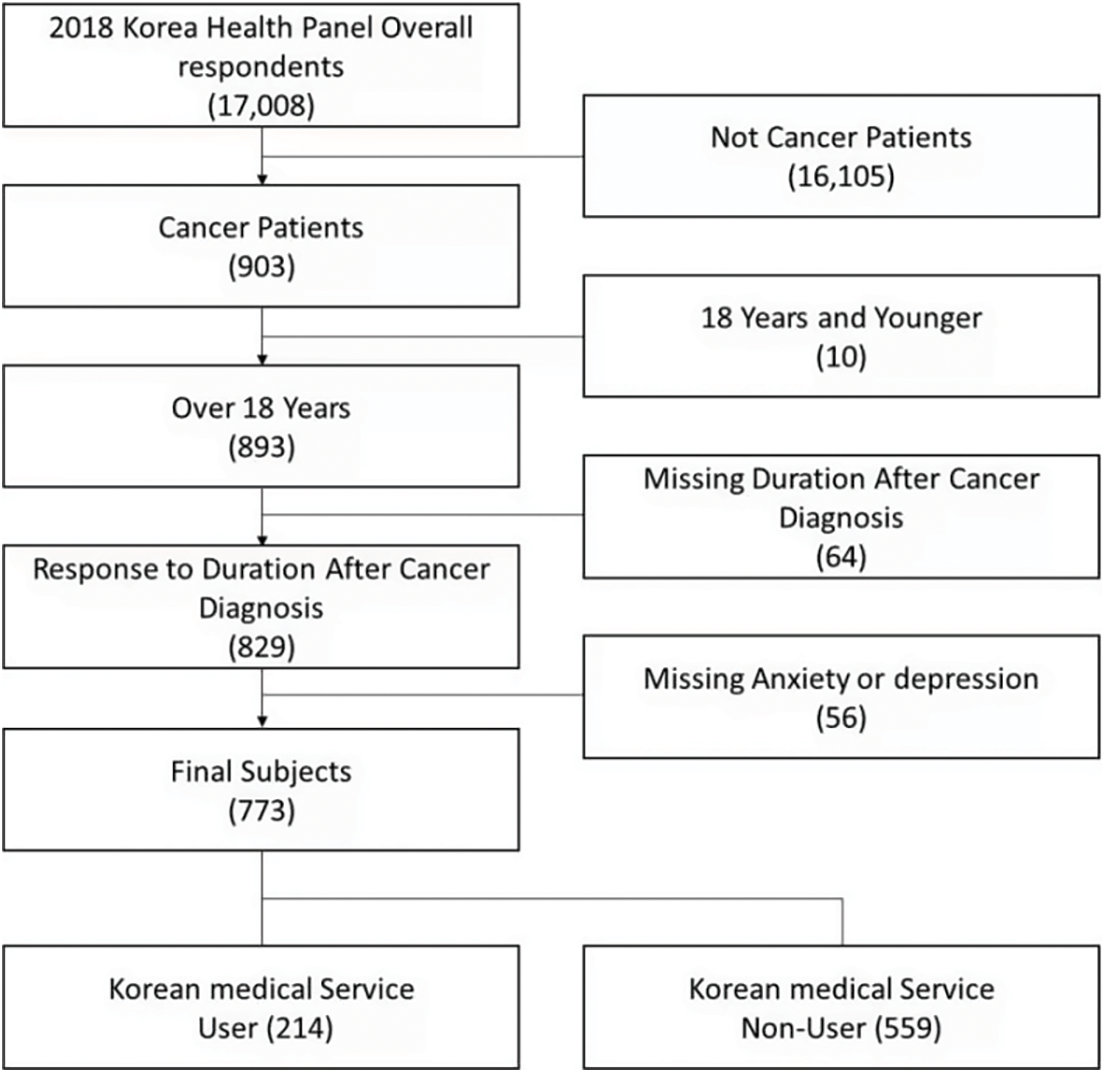

The 2018 KHP data included 17,008 participants. Among these, participants who responded with “C00-D48 Neoplasms” to the question “Chronic diseases you have” in the chronic disease and medication use survey were included. A total of 16,105 participants who did not diagnosed with malignant or benign tumors were excluded from the study. Participants aged <19 years were excluded because they could not make independent decisions regarding medical care (n = 10). By asking the question regarding the year of cancer diagnosis, we aimed to exclude patients diagnosed with benign tumors and include only cancer patients; therefore, 64 participants who responded “unknown or no response” to this question were excluded. Finally, 56 participants who responded with unknown or no response to questions about anxiety or depression were excluded.

The final study population consisted of 773 participants, of whom 214 had utilized KM and 559 had not (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Flow chart of sample selection

We conducted two multiple logistic regression analyses to analyze the association between the period after diagnosis and anxiety or depression, and as well as the use of KM among patients with cancer.

In the first logistic regression analysis conducted to analyze the relationship of the period after cancer diagnosis on anxiety or depression, the dependent variable was set as “presence or absence of anxiety or depression” among cancer patients. The presence or absence of anxiety or depression among cancer patients was determined based on their response to the question, “How would you rate your level of anxiety or depression?” in the “Quality of Life” section of the 2018 KHP Survey. Those who responded “somewhat anxious or depressed” or “very anxious or depressed” were classified as “with anxiety or depression,” while those who responded “not anxious or depressed” were classified as “without anxiety or depression.”

After stratifying cancer patients by their anxiety or depression status, logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the association between duration since cancer diagnosis and the use of KM. The dependent variable was set as the “Korean medicine utilization (KM utilization)” among the participants. In the KHP data, the use of KM is categorized into emergency, inpatient, and outpatient services. Considering that all items would be beneficial for analyzing KM utilization, the 2018 KHP data had few observations of KM utilization in emergency and inpatient services, which could introduce bias due to the small sample size. Therefore, this study only analyzed patients who used outpatient KM services. Accordingly, in the outpatient medical service utilization questionnaire, respondents who answered “Korean medicine hospital” or “Korean medicine clinic” to the question “What type of hospital (or clinic) did you visit?” were defined as users of Korean medical services. Furthermore, we conducted an analysis to examine the diseases participants aimed to treat and the treatment methods they utilized, to support the understanding of KM utilization.

The “duration since cancer diagnosis” was selected as the primary independent variable for the two main logistic regression analyses. In the chronic disease and medicaion use question of the KHP data, the responses to the question “When were you diagno”. In the case of cancer, considering that five years after diagnosis is an important milestone for survival, we classified five years or more as a single category. Considering the distribution of observations suitable for analysis, we finally classified them into “less than 3 years,” “3 years or more to less than 5 years,” and “5 years or more.”

In addition, variables expected to correlate with KM use among cancer patients, such as sex, age, education level, household income, residential area, number of chronic diseases, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D), were selected as independent variables. Sex was categorized as male or female, and age was confirmed as a continuous variable. Educational level was categorized as elementary school graduate or below, high school graduate or below, or college enrollment or above. Household income was adjusted by dividing the annual total household income by the square root of the number of household members, and then categorized into three groups: less than 15 million won, 15 million won or more but less than 30 million won, and 30 million won or more. The residence area was categorized as urban if the respondents’ current addresses on the survey date were in Seoul Special City, Sejong City, or one of the six metropolitan cities, and rural for all other areas. The number of chronic diseases was calculated as a continuous variable based on the respondent’s number of chronic diseases. The CCI was calculated by summing the weights assigned to 17 major chronic diseases based on Korean Classification of Diseases (KCD) codes and classifying them into three groups according to the severity of comorbidities. The EQ-5D is a validated measure of health-related quality of life across five dimensions. Responses of “somewhat impaired” or “very impaired or severe” to each item were assigned weights and converted into a continuous variable. The quality-of-life variable was calculated using EQ-5D profile scores adjusted by a South Korean time-trade-off value.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between anxiety or depression and the use of KM, and how, during the period after cancer diagnosis, it is associated with the use of KM. In this context, anxiety or depression may act as a mediating variable between the period after cancer diagnosis and the use of KM. Specifically, patients with cancer may experience anxiety or depression depending on the period following cancer diagnosis, and this anxiety or depression may, in turn, be associated with the utilization of KM. Therefore, we first conducted a logistic regression analysis to examine whether anxiety or depression occurred depending on the period after cancer diagnosis in cancer patients. We then conducted a second logistic regression analysis, stratifying the subjects into those with and without anxiety or depression to eliminate the mediating effect of anxiety or depression, and analyzed the association between the period after cancer diagnosis and the use of KM.

First, we performed a descriptive analysis of all cancer patients to analyze their general characteristics. To verify the association between patient characteristics and the presence or absence of anxiety or depression and the use of KM, we conducted a chi-square test for nominal variables and a t-test for continuous variables, including the period after cancer diagnosis.

Subsequently, to analyze whether the period after cancer diagnosis affected anxiety or depression, a simple logistic regression analysis was performed using only the variables representing the period after cancer diagnosis, and a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed, including the subject characteristic variables.

Finally, to analyze the association between the period after cancer diagnosis, the presence or absence of anxiety or depression, and the use of KM, we conducted a single logistic regression analysis with the use of KM as the dependent variable, distinguishing between cases with and without anxiety or depression, and a multiple logistic regression analysis including both the period after cancer diagnosis and participant characteristics.

Model fit was assessed using the goodness-of-fit test, and the model’s explanatory power was evaluated by calculating c-statistics. To check for multicollinearity among independent variables, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated, and values below 10 were confirmed before presenting the average values.

All analyses were performed using Stata (Stata BE, version 18.0, Stata Corp., TX, USA), and hypothesis testing was conducted at a significance level of 0.05.

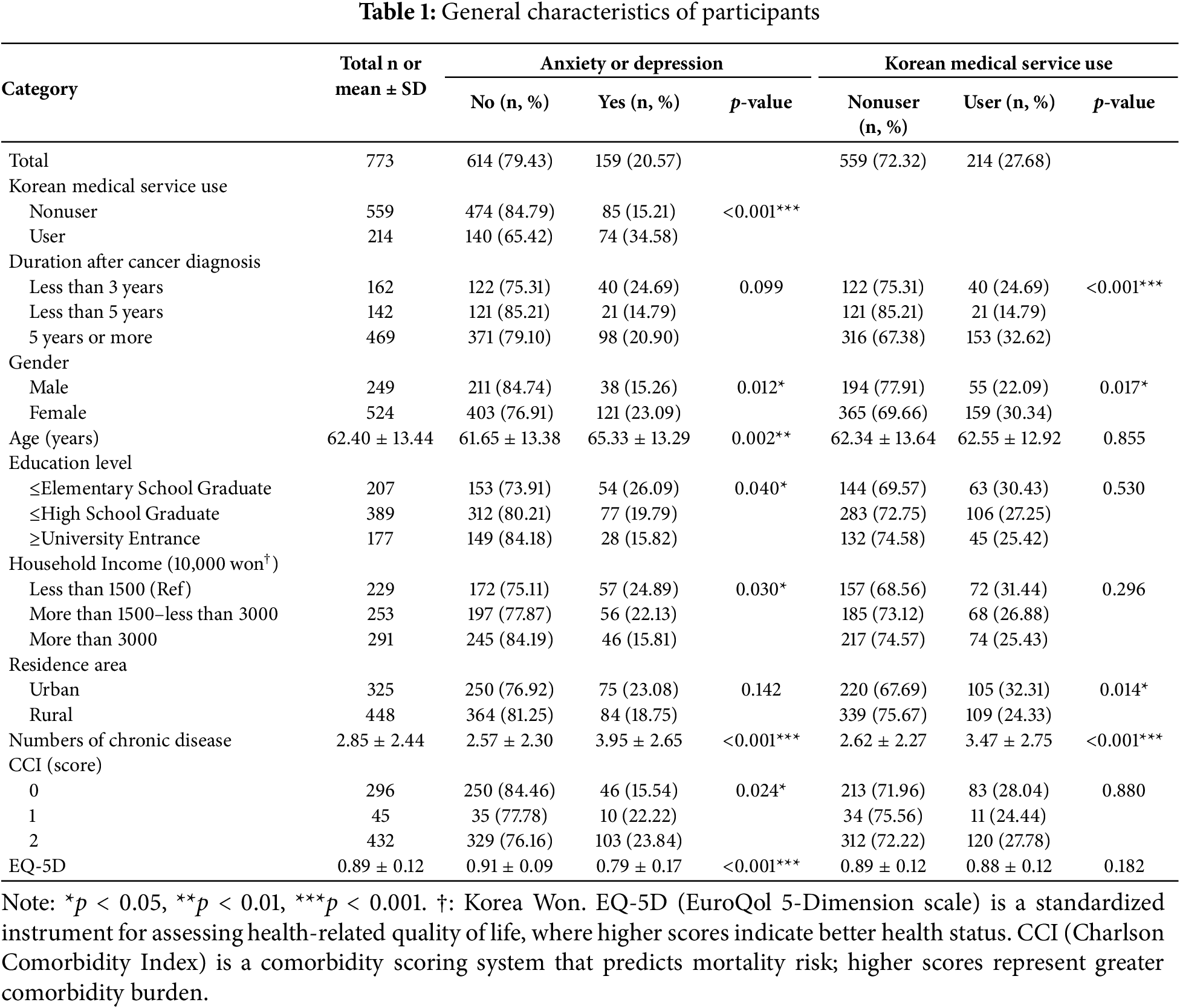

The total number of participants was 773, of whom 159 (20.57%) had anxiety or depression and 214 (27.68%) had used KM.

Statistically significant differences in anxiety or depression were observed for the following variables: use of KM, sex, age, education level, household income, number of chronic diseases, CCI score, and quality of life (EQ-5D). The duration since cancer diagnosis did not influence anxiety or depression.

Specifically, among those with anxiety or depression, 15.21% did not use KM, whereas 34.58% did, indicating a higher proportion of users. Gender showed that women had a higher rate of anxiety or depression (23.09%) than did men (15.26%). The average age of the participants was 62.40 (±13.44), with an average age of 61.65 (±13.38) for those without anxiety or depression and 65.33 (±13.29) for those with anxiety or depression, indicating a higher average age in the group with anxiety or depression. Educational attainment showed that the proportion of those with anxiety or depression was highest in the group with an educational level of elementary school graduation or below (26.09%), followed by the group with a high school graduation or below (19.79%), and the group with a college education or higher (15.82%). Household income showed the highest rate of anxiety or depression at 24.89% in the group earning less than 15 million won, followed by 22.13% in the group earning between 15 and 30 million won, and 15.81% in the group earning 30 million won or more. The average number of chronic diseases among the participants was 2.85 (±2.44), with the group experiencing anxiety or depression having an average of 3.95 (±2.65) chronic diseases, which was higher than the average of 2.57 (±2.30) in the group without anxiety or depression. The CCI score showed that the proportion of participants with anxiety or depression was the lowest at 15.54% for a score of 0, 22.22% for a score of 1, and 23.84% for a score of 2, with the proportion gradually increasing with higher scores. The EQ-5D score was 0.89 (±0.12) on average, with the average for the group without anxiety or depression being 0.91 (±0.09), which was higher than the average of 0.79 (±0.17) for the group with anxiety or depression.

Variables associated with using KM include the duration since cancer diagnosis, sex, residential area, and the number of chronic diseases. When examining the items that showed statistically significant differences in detail, the proportion of KM users was the highest at 32.62% for those who had been diagnosed with cancer for five years or more, followed by 24.69% for those diagnosed for less than three years, and 14.79% for those diagnosed for less than five years. The proportion of women who utilized KM was 30.34%, higher than the 22.09% of men. The proportion of KM users was 32.31% in urban areas, which was higher than that in rural areas (24.33%). Regarding the number of chronic diseases, the group that utilized KM had an average of 3.47 (±2.75) chronic diseases, which was higher than the average of 2.62 (±2.27) in the group that did not utilize KM (Table 1).

3.2 Analysis of the Association between the Period after Cancer Diagnosis and Anxiety or Depression

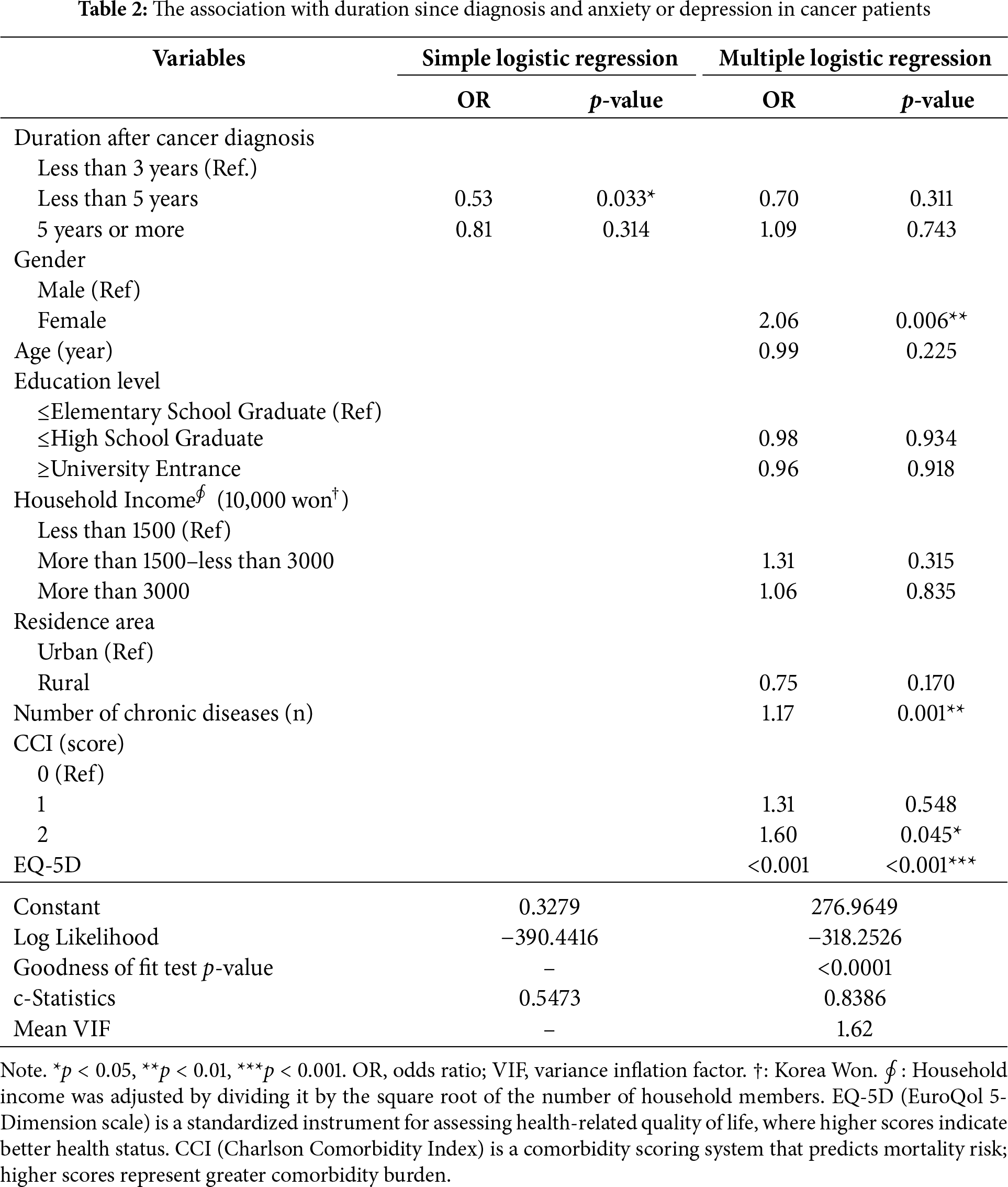

The results of a single logistic regression analysis based on the period after cancer diagnosis showed that the probability of anxiety or depression was significantly lower in patients with a period of less than five years after diagnosis than in those with a period of less than three years (odds ratio [OR] = 0.53, p = 0.033). However, in multivariate logistic regression analysis, the duration since cancer diagnosis did not have a significant relationship with the presence of anxiety or depression.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, the variables that were significantly associated with the presence of anxiety or depression in patients with cancer were sex, number of chronic diseases, CCI score, and EQ-5D. Female cancer patients had a higher probability of experiencing anxiety or depression (OR = 2.06, p = 0.006), and this probability increased with the number of chronic diseases (OR = 1.17, p = 0.001). A CCI score of 2 was associated with a higher likelihood of anxiety or depression than a CCI score of 0 (OR = 1.60, p = 0.045), and the higher the EQ-5D score, the lower the likelihood of anxiety or depression (OR = 0.00, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

3.3 Analysis of the Association between the Period after Cancer Diagnosis, Anxiety or Depression, and the Use of KM

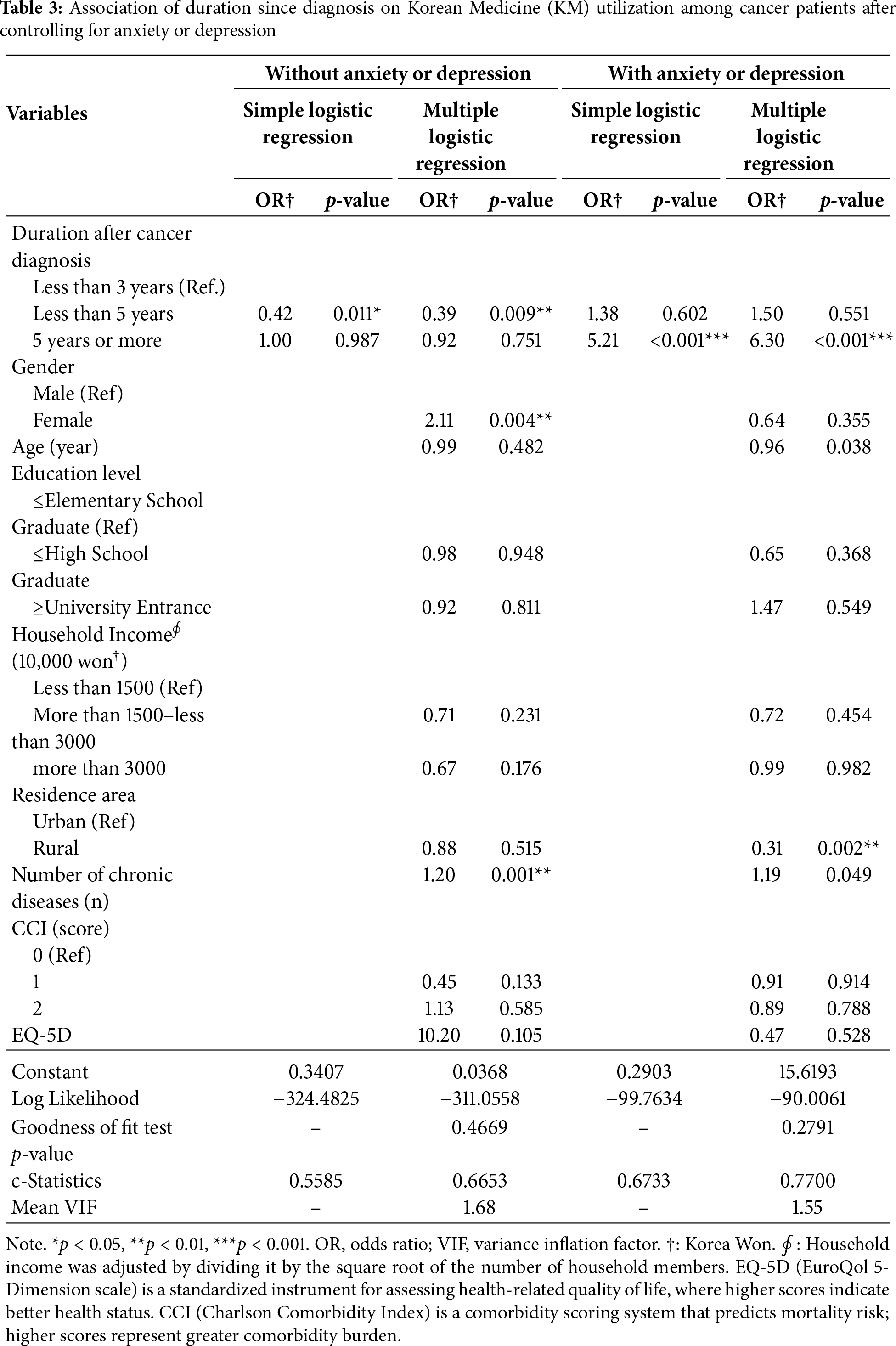

To analyze the association between the period after cancer diagnosis, anxiety or depression, and the use of KM, participants were stratified according to the presence or absence of anxiety or depression, followed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. First, when cancer patients did not have anxiety or depression, the single logistic regression analysis (OR = 0.42, p = 0.011) and the multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR = 0.39, p = 0.009) both showed that the probability of using KM was lower when the period after diagnosis was less than 5 years compared to less than 3 years, and this was statistically significant (Table 3).

Additionally, in the absence of anxiety or depression, the likelihood of utilizing KM increased when the subject participants were female (OR = 2.11, p = 0.004) and as the number of chronic diseases increased (OR = 1.20, p = 0.001).

Among cancer patients with anxiety or depression, those diagnosed with cancer for five years or more had a higher probability of using KM than those diagnosed for less than five years, as indicated by both univariate (OR = 5.21, p < 0.001) and multivariate logistic regression analyses (OR = 6.30, p < 0.001), which were statistically significant.

In cases of anxiety or depression, the likelihood of utilizing KM was lower among rural residents (OR = 0.31, p = 0.002) compared to urban residents.

This study was conducted to identify the factors associated with cancer patients’ anxiety or depression and the utilization of KM, and to analyze the key determinants that shape the relationship between these variables. In this study, anxiety or depression among patients with cancer was associated with factors such as sex, number of chronic diseases, CCI score, and EQ-5D. The finding that women were more likely to experience symptoms of anxiety or depression is consistent with previous studies indicating that physiological and social differences can affect psychological health [29–31]. Moreover, a higher number of comorbid chronic diseases or a higher CCI score can increase the mental burden on patients because these factors are known to increase the risk of depression [32–34]. However, a cohort study indicated that the risk of accumulating chronic diseases increases among individuals with anxiety or depression [35]. In this study, it was not possible to determine whether anxiety or depression was a consequence of cancer diagnosis and treatment or a preexisting condition; thus, both possibilities must be carefully considered in the interpretation of these results.

The results suggest that patients with cancer tend to adapt psychologically over time following their diagnosis. While patients with cancer initially experience psychological shock along with anxiety or depression, they gradually adapt psychologically over time and may develop a more positive attitude. This aligns with previous research indicating that patients diagnosed with cancer for a shorter duration are more likely to experience adjustment disorders [36,37], and studies showing that, after 8 years from diagnosis, cancer patients do not differ significantly from healthy individuals in terms of depression, anxiety, and life satisfaction [38]. These findings imply that cancer patients gradually adapt to their situation and condition over time, and that an appropriate period is needed for patients to accept their condition and the treatment they will undergo to foster a positive attitude. However, as this relationship was significant only in a single logistic regression analysis, further research using a more robust methodology is required to clarify this trend.

This study did not confirm a direct correlation between the mental health status of cancer patients and their utilization of KM, but identified factors related to anxiety or depression that may be associated with KM use. Patients without anxiety or depression were more likely to use KM within three years of diagnosis, whereas those with anxiety or depression showed higher KM utilization after more than five years since diagnosis. These findings suggest that the study has identified a significant potential, specifically that the temporal dynamics of psychological adjustment post-diagnosis in cancer patients are associated with patterns of KM utilization. Patients without anxiety or depression may perceive their cancer as less severe or experience less prognostic uncertainty, leading to faster acceptance of their condition and more proactive seeking of alternative treatments such as KM. This interpretation is supported by previous research indicating that psychosocial adaptation is associated with reduced uncertainty and increased hope [39]. Conversely, patients experiencing anxiety or depression tend to exhibit lower treatment adherence, which may delay acceptance of their condition and KM utilization [6]. However, owing to the lack of clear evidence, further studies are needed to determine the direct correlates of anxiety or depression and the use of KM.

Another important finding of this study was the difference between urban and rural areas; patients in urban areas were more likely to use KM. This can be interpreted as a result of the relatively higher accessibility of medical resources and information in urban areas [40], which may facilitate the concurrent use of standard cancer treatments and alternative therapies such as KM. By contrast, patients living in rural areas may face challenges in accessing medical infrastructure, information, and economic resources, which could limit their ability to utilize KM. This regional disparity reaffirms previous findings that various socioeconomic factors influence cancer patients’ treatment choices, and that these factors ultimately affect their mental health and quality of life [21], highlighting the need for support systems that consider socioeconomic status.

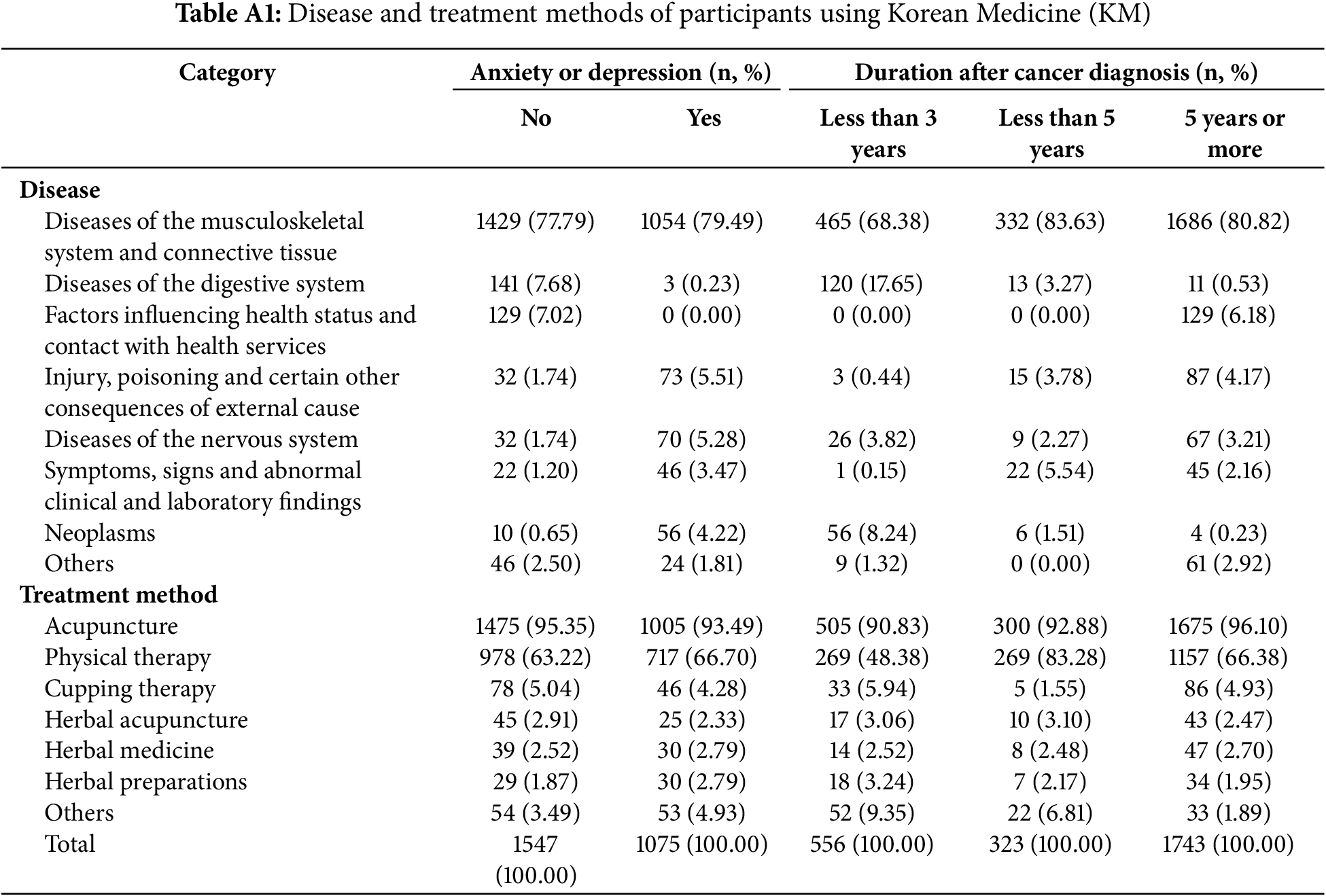

This study has several limitations. First, although anxiety and depression are often considered similar psychological issues, they are distinct mental states. The decision to group them into segments in this study may have limited the precision of the findings. Second, because anxiety or depression may either precede or result from a cancer diagnosis, careful consideration is needed when interpreting the results. Third, the KHP data lacks a precise measurement tool for anxiety and depression, with these conditions inferred from the EQ-5D items. Consequently, the precision of the measurement may be compromised in terms of capturing the severity, distinctiveness, and diagnostic relevance of both conditions. Fourth, although this study identified various socioeconomic and healthcare-related factors associated with KM utilization, it did not establish a direct causal relationship between anxiety, depression, and KM use. Additionally, the primary purpose of KM utilization among patients was not for the improvement of their psychological state (Table A1). Therefore, future studies should aim to clarify KM’s effects on cancer patients’ mental health through clinical trials, long-term follow-up studies, or qualitative research.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the psychosocial functions of KM, particularly regarding the temporal dynamics of psychological adjustment post-diagnosis among cancer patients. Future research should focus on exploring psychosocial relationships, such as the direct impact of KM utilization on the improvement of mental health in cancer patients, which could lead to important discoveries regarding the role of KM in enhancing psychological resilience and overall health management in cancer patients.

This study confirmed that the pattern of KM utilization among cancer patients may vary depending on their psychological state, such as anxiety or depression. Specifically, the finding that there was a difference in the “period after cancer diagnosis” in the utilization of KM between patients who experienced anxiety or depression and those who did not indirectly suggests that psychological states may be associated with the use of KM. Further research is needed to identify direct correlations between anxiety, depression, and KM use.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by a grant of the R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-KH139376). The funding body did not participate in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of the manuscript.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Dongsu Kim, Hanbit Jin; data collection: Eunji Ahn; analysis and interpretation of results: Dongsu Kim, Ji-eun Yu, Eunji Ahn; draft manuscript preparation: Ji-eun Yu, Eunji Ahn. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dongsu Kim, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Dongshin University Bioethics Committee (IRB No.: 1040708-202402-SB-002) in February 2024. This is because the Korea Health Panel contains secondary data that does not contain any private information available in the public domain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Term | Interpretation |

| KM | Korean Medicine |

| KIHASA | Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs |

| NHIS | National Health Insurance Service |

| KHP | Korea Health Panel |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| KCD | Korean Classification of Diseases |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

1. Lim CYS, Laidsaar-Powell RC, Young JM, Solomon M, Steffens D, Blinman P, et al. Fear of cancer progression and death anxiety in survivors of advanced colorectal cancer: a qualitative study exploring coping strategies and quality of life. Omega. 2025;90(3):1325–62. doi:10.1177/00302228221121493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Galica J, Giroux J, Francis JA, Maheu C. Coping with fear of cancer recurrence among ovarian cancer survivors living in small urban and rural settings: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;44(4):101705. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Salvetti MDG, Machado CSP, Donato SCT, Silva AMD. Prevalence of symptoms and quality of life of cancer patients. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(2):e20180287. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kayastha N, LeBlanc TW. When to integrate palliative care in the trajectory of cancer care. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(5):41. doi:10.1007/s11864-020-00743-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lu D, Andersson TML, Fall K, Hultman CM, Czene K, Valdimarsdóttir U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders immediately before and after cancer diagnosis: a nationwide matched cohort study in Sweden. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1188–96. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pezzolato M, Spada GE, Fragale E, Cutica I, Masiero M, Marzorati C, et al. Predictive models of psychological distress, quality of life, and adherence to medication in breast cancer patients: a scoping review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:3461–73. doi:10.2147/PPA.S440148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Omran S, McMillan S. Symptom severity, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(2):365–74. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.2.365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB. Impact of depression on treatment adherence and survival from cancer. In: Kissane DW, Maj M, Sartorius N, editors. Depression and cancer. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. p. 101–24. doi:10.1002/9780470972533.ch5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Davies EA, Wand Y. Could improving mental health disorders help increase cancer survival? Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(7):e482–4. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00156-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS, Glass BD. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35(3):33–47. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Alejandra R, Francisco G, Mario G, Juan AM. Psychological and non-pharmacologic treatments for pain in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2022;63(5):e505–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Alberto PP, Anna LS, Sara C, Francesco O, Luca O. EMDR in cancer patients: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2020;11:590204. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Xiao P, Ding S, Duan Y, Li L, Zhou Y, Luo X, et al. Effect of light therapy on cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2022;63(2):e188–202. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Yao L, Zhang Z, Lam L. The effect of light therapy on sleep quality in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiaty. 2023;14:1211561. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1211561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Rodrigues JM, Santos C, Ribeiro V, Silva A, Lopes L, Machado JP. Mental health benefits of traditional Chinese medicine—an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Brain Behav Immun Integr. 2023;2(5):100013. doi:10.1016/j.bbii.2023.100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han G, Lee Y, Jang H, Kim S, Lee Y, Ha I. Symptom management and quality of life of breast cancer patients using acupuncture-related therapies and herbal medicine: a scoping review. Cancers. 2022;14(19):4683. doi:10.3390/cancers14194683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Han Y, Wang H, Xu W, Cao B, Han L, Jia L, et al. Chinese herbal medicine as maintenance therapy for improving the quality of life for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24(2–3):81–9. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2015.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Peng L, Zhang K, Li Y, Chen L, Gao H, Chen H. Real-world evidence of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatment on cancer: a literature-based review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2022;2022(1):7770380. doi:10.1155/2022/7770380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Choi YJ, Lee JS, Cho SH. Use of Korean Medicine among cancer patients. J Korean Med. 2012;33(3):46–53. [Google Scholar]

20. Lee EL, Richards N, Harrison J, Barnes J. Prevalence of use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine by the general population: a systematic review of national studies published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022;45(7):713–35. doi:10.1007/s40264-022-01189-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kuo YT, Chang TT, Muo CH, Wu MY, Sun MF, Yeh CC, et al. Use of complementary traditional Chinese medicines by adult cancer patients in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):531–41. doi:10.1177/1534735417716302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tankiatkumjai M, Boardman H, Walker DM. Potential factors that influence usage of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide: a systematic review. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):363. doi:10.1186/s12906-020-03157-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ciarlo G, Ahmadi E, Welter S, Hübner J. Factors influencing the usage of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;44(6):101389. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chao MT, Wade CM. Socioeconomic factors and women’s use of complementary and alternative medicine in four racial/ethnic groups. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(1):65–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Ludwick A, Corey K, Meghani S. Racial and socioeconomic factors associated with the use of complementary and alternative modalities for pain in cancer outpatients: an integrative review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020;21(2):142–50. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2019.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Park EJ. A report on the Korea health panel survey of 2018. Republic of Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2020. [Google Scholar]

27. National Health Insurance Service, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Korean Health Panel Survey. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.khp.re.kr:444/. [Google Scholar]

28. National Health Insurance Service, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Korea health panel annual data (2008–2018). 2022. [Google Scholar]

29. Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):146–58. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Parker G, Brotchie H. Gender differences in depression. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(5):429–36. doi:10.3109/09540261.2010.492391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li SH, Graham BM. Why are women so vulnerable to anxiety, trauma-related and stress-related disorders? The potential role of sex hormones. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):73–82. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30358-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang YZ, Xue C, Ma C, Liu AB. Associations of the Charlson comorbidity index with depression and mortality among the US adults. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1404270. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1404270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ma Y, Xian Q, Yan C, Liao H, Wang J. Relationship between chronic diseases and depression: the mediating effect of pain. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):436. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03428-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu R, He WB, Cao LJ, Wang L, Wei Q. Association between chronic disease and depression among older adults in China: the moderating role of social participation. Public Health. 2023;221(2):73–8. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2023.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bobo WV, Grossardt BR, Virani S, St Sauver JL, Boyd CM, Rocca WA. Association of depression and anxiety with the accumulation of chronic conditions. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e229817. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Van Beek FE, Wijnhoven LMA, Custers JAE, Holtmaat K, De Rooij BH, Horevoorts NJ, et al. Adjustment disorder in cancer patients after treatment: prevalence and acceptance of psychological treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(2):1797–806. doi:10.1007/s00520-021-06530-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–74. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Schroevers M, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R. Adjustment to cancer in the 8 years following diagnosis: a longitudinal study comparing cancer survivors with healthy individuals. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(3):598–610. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhu H, Yang L, Yin H, Yuan X, Gu J, Yang Y. The influencing factors of psychosocial adaptation of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Serv Insights. 2024;17:11786329241278814. doi:10.1177/11786329241278814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Williamson G. Healthcare access disparities among marginalized communities. Glob Perspect Health Med Nurs. 2024;3(1):11–22. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools