Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Examining the Influence of Psychological Factors on Mental Health Problems in Korean Adolescents

1 Department of Sport Science, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, 01811, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Health and Fitness, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, 01811, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Youngho Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Improving Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) Through Promoting Health-Related Behaviors)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1411-1421. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069543

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: It has been broadly witnessed that a large number of adolescents are suffering emotional and mental health problems after COVID-19, and such adverse experiences in early life often extend into adulthood, resulting in serious long-term implications. However, it is accepted that the literature examining the relationship between mental health problems in adolescents and their underlying psychological factors is limited. The purposes of the current study were to identify mental health problems of Korean adolescents and to investigate the possible influence of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and health locus of control on mental health problems. Methods: A total of 2104 Korean adolescents were randomly recruited from junior high and high schools located in Seoul, Korea. The Korean Symptom Checklist, and Self-esteem Scale, Health Locus of Control Scale, Self-efficacy Scale were applied to identify mental health problems and psychological factors among adolescents. Frequency analysis, independent t-tests, one-way ANOVA, correlation analysis, and multiple regression analysis were performed to test the study hypothesis. Results: Korean adolescents showed a high prevalence of depression (61.4%), anxiety (44.7%), interpersonal sensitivity (76.1%), and hostility (40.3%). In addition, the findings indicated significant gender and age differences in adolescent mental health problems. Moreover, results reported that the adolescents’ mental health problems were significantly associated with psychological factors (R2 = 0.51 for depression, 0.38 for anxiety, 0.33 for interpersonal sensitivity, and 0.23 for hostility). Conclusions: The current findings highlight the need for comprehensive, culturally relevant mental health strategies for Korean adolescents. The interventions that foster psychological resilience, promote positive self-concept, and encourage internal control beliefs may be effective in mitigating mental health challenges.Keywords

Adolescence, derived from the Latin word adolescere, meaning “to grow up,” represents a crucial stage of life marked by rapid biological, psychological, and social transitions. It is a period during which individuals navigate the formation of their identity, emotional maturation, and social integration [1]. These processes increase vulnerability to psychological distress, and when unaddressed, such mental health problems may persist into adulthood and significantly impact well-being and functioning [2–4].

Mental health in adolescence is influenced by developmental challenges, such as identity exploration, increased autonomy, peer comparison, and academic competition. In highly competitive societies such as Korea, adolescents face immense pressure to perform academically, meet parental expectations, and conform socially [5,6]. Furthermore, mental health issues manifesting in adolescence may indicate either the persistence of childhood-onset issues or the emergence of a new illness. These mental health problems generally include depression, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, loneliness, and hostility, and are sometimes associated with suicide [7,8].

Recently, there has been growing concern over the mental health status of adolescents around the world. Depression, anxiety, and behavioral issues are among the leading contributors to adolescent morbidity and disability [9]. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) reported that approximately 28% of adolescents experienced depressive symptoms within the past year, with an observable surge following the COVID-19 pandemic. Such findings reflect a growing mental health crisis that demands culturally specific inquiry and intervention [10].

It has been widely understood that mental health is overtly interacted with physical, social, and psychological factors [11]. Therefore, factors that affect the mental health of adolescents can be associated with issues from the emotional, psychological, and behavioral domains. Specifically, adolescents’ mental health problems may be caused by negative psychological attributes, such as low self-efficacy and self-esteem, and loss of ability to control health.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) provides a valuable framework for understanding and addressing mental health [12]. It emphasizes how individual experiences, social influences, and environmental factors interact to shape behavior and mental well-being. As core constructs, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and locus of control are interconnected concepts within the SCT [13].

Self-efficacy was introduced by Bandura [12] for cognitive modification. Self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s belief in their capacity to successfully perform the actions required to achieve a specific goal, a belief that is rooted in personal perception [14]. The construct of self-efficacy has been extensively applied across a diverse range of domains, including academic achievement and psychological well-being. In the context of mental health, perceived self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to alter adverse mental states through personal agency, for instance, by acquiring skills to prevent them. This conviction subsequently shapes their intention to modify detrimental behaviors and the degree of effort they invest in reaching this objective [15].

A study by Schönfeld et al. analyzing the relationship between adolescent depression and self-efficacy found that depression was characterized by heightened negative attributions and reduced self-efficacy [16]. Findings implied that self-efficacy played a mediating role in the decrease of depressive symptoms. Recently, Park and Lee [17] revealed that self-efficacy was a significant factor in maintaining the mental health of adolescents. The study revealed that higher levels of self-efficacy were functionally linked to effective affective control, manifested as both the avoidance of sadness and emotional management. A significant positive correlation was also identified between self-efficacy and sustained self-confidence. This reinforces the critical importance of considering such psychological constructs in the formulation of therapeutic mental health programs.

Self-esteem is widely regarded as a foundational component of psychological functioning, demonstrating significant associations with numerous variables, including general life satisfaction [18]. It is defined as an individual’s internal appraisal of self-worth, encompassing confidence in one’s abilities and judgments, and reflecting a favorable self-perspective [19]. Sowislo and Orth [20] posited that self-esteem is linked to a wide array of both psychological and behavioral outcomes. For instance, they suggested that adolescents with low self-esteem, compared to their high-self-esteem peers, exhibit greater depressive symptoms, diminished life satisfaction, and elevated levels of anxiety, aggression, and irritability. Corroborating this association, research by Song et al. [21] provided further evidence for the link between self-esteem and mental health. The authors found a substantial inverse correlation between self-esteem and negative affective states such as anxiety and fear in adolescents. Notably, their results also revealed a gender-specific dynamic: while boys demonstrated a significant reduction in anxiety and fear following a coping session, girls exhibited consistently low levels of self-esteem throughout the intervention.

Multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC), originally based on Rotter’s social learning theory [22], was developed to seek, describe, predict, and influence individuals’ perception and behavior regarding their health. MHLC refers to people’s attribution of their own health to personal or environmental factors and is divided into internal health locus of control (IHLC), powerful other health locus of control (PHLC), and chance health locus of control (CHLC) [23]. IHLC refers to the belief that an individual’s health is primarily determined by their own actions and behaviors. Individuals with a strong internal health locus of control believe they can influence their health outcomes through their choices and efforts. This contrasts with an external health locus of control. PHLC refers to the belief that one’s health is primarily controlled or influenced by the actions and decisions of others, particularly those in positions of authority or expertise, such as doctors, family members, or friends. CHLC refers to the belief that health outcomes are determined by luck, fate, or chance, rather than by individual actions or the influence of others [24]. An investigation by Tak et al. into the mental health beliefs of adolescents revealed significant gender-based differences. Specifically, male participants demonstrated a stronger and more concurrent endorsement of IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC compared to their female counterparts. Females are significantly different from males in that they believe positive mental health is related to an external locus of control [25]. More recently, an investigation by Li et al. [26] into the mental health beliefs of adolescents revealed significant gender-based differences. Specifically, male participants demonstrated a stronger and more concurrent endorsement of IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC compared to their female counterparts.

Adolescents’ mental health and its related psychological factors have been paid great attention as important public and social issues in Korea. Therefore, this study aims to examine the prevalence and characteristics of mental health problems among Korean adolescents and to explore how specific psychological variables relate to these issues. By focusing on a representative sample of urban adolescents, this research seeks to contribute to the development of culturally sensitive mental health programs and broaden the understanding of adolescent psychological well-being in Korea. The research hypotheses were set as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Adolescents’ mental health problems will be significantly different between gender and age.

Hypothesis 2. Mental health problems (interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and hostility) will be significantly correlated with psychological factors (self-efficacy, self-esteem, IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC).

Hypothesis 3. Psychological factors (self-efficacy, self-esteem, IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC) will be significantly related to mental health problems (interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and hostility).

2104 adolescents (1075 males and 1029 females) aged from 13–18 years (Mean = 15.7, standard deviation [SD] = 1.7) voluntarily participated in the study. The students were randomly selected from the five schools that were geographically located in the mid-range socioeconomic areas of Seoul. Among the possible participants, the students who have no physical or mental illness and who completed the survey form were included in the study as the final study participants. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University of Science and Technology, and all procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (No. 2025-0572). Before data collection, informed consent was obtained from both the adolescents and their legal guardians, with all participants assured of the confidentiality and voluntary nature of their participation.

The Korean Symptom Checklist [27] was applied to assess Korean adolescents’ mental health problems. This scale consists of four sub-constructs with 38 items (13 items for depression, 10 items for anxiety, 9 items for interpersonal sensitivity, and 6 items for hostility). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very often).

To establish the reliability of the measure, a pilot study was conducted with a sample of 164 adolescents (94 males, 70 females) of a similar age to the target sample. Internal consistency was evaluated at the initial administration, and stability was examined through a follow-up administration with the same 78 participants two weeks later. The test–retest reliability coefficients for the four sub-constructs were as follows: anxiety (r = 0.91), depression (r = 0.90), hostility (r = 0.84), and interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.81).

To measure Korean adolescents’ self-reliability and ability to control health and life satisfaction associated with mental health, the three scales translated by Kim [28] were used: Self-efficacy Scale and Self-esteem Scale, and Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) Scale. This study utilized the Korean version of the Self-efficacy Scale, which was adapted from the original instrument developed by Sherer et al. [29]. Among 17 items, 13 items were reversed, requiring the scores to be converted. Items were rated on a 14-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 14 (strongly agree). A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88 was reported for this scale.

The Korean version of the Self-esteem Scale, developed by Rosenberg [18], was used to the study. This scale consists of 10 items with 5 reversed items requiring scores to be converted. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The test–retest reliability method was performed, and a reliability of 0.83 was obtained.

The MHLC Scale, developed by Wallston et al. [23], was translated into Korean and applied in the study. The revised scale consists of the three sub-scales and 18 items. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Alpha reliabilities of each sub-scale were 0.83 for IHLC, 0.79 for PHLC, and 0.81 for CHLC.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency analysis was conducted to identify Korean adolescents’ mental health problems (depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility). Independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA determined gender and age differences in mental health problems. Pearson correlation analysis explored associations between psychological factors (self-efficacy, self-esteem, IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC) and mental health problems. Multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the relationships between psychological factors and mental health problems.

3.1 Mental Health Problems of Korean Adolescents

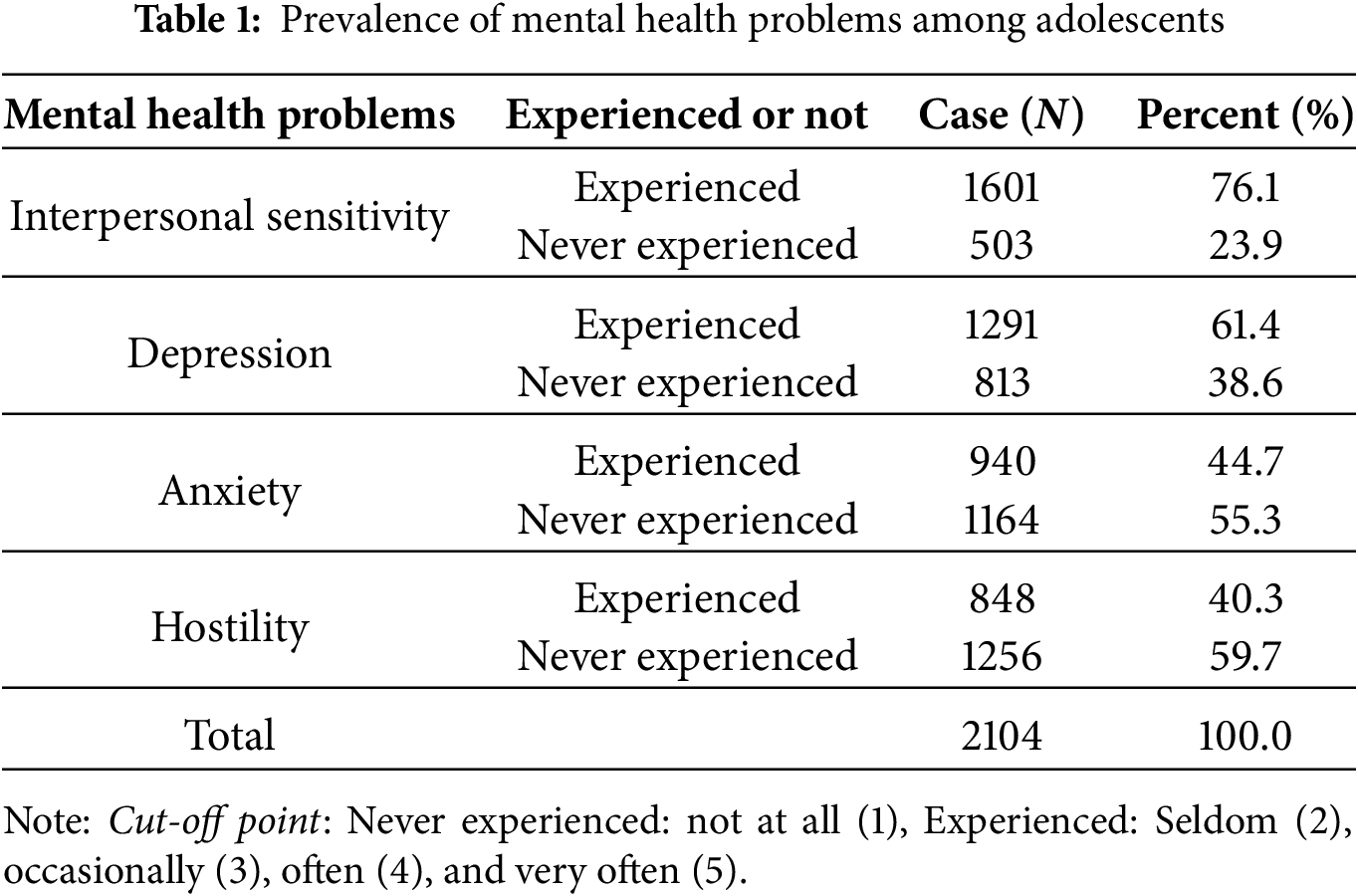

Frequency analysis was conducted to show Korean adolescents’ mental health problems. According to Table 1, among the adolescents, 76.1% reported frequent experiences of interpersonal sensitivity, 61.4% experienced depression, 44.7% reported anxiety, and 40.3% endorsed feelings of hostility. Considering the high prevalence in all sub-constructs, negative mental health in Korean adolescents is a critical factor that might negatively affect their health. These results underscore the widespread presence of emotional distress among Korean youth.

3.2 Gender and Age Differences in Mental Health Problems

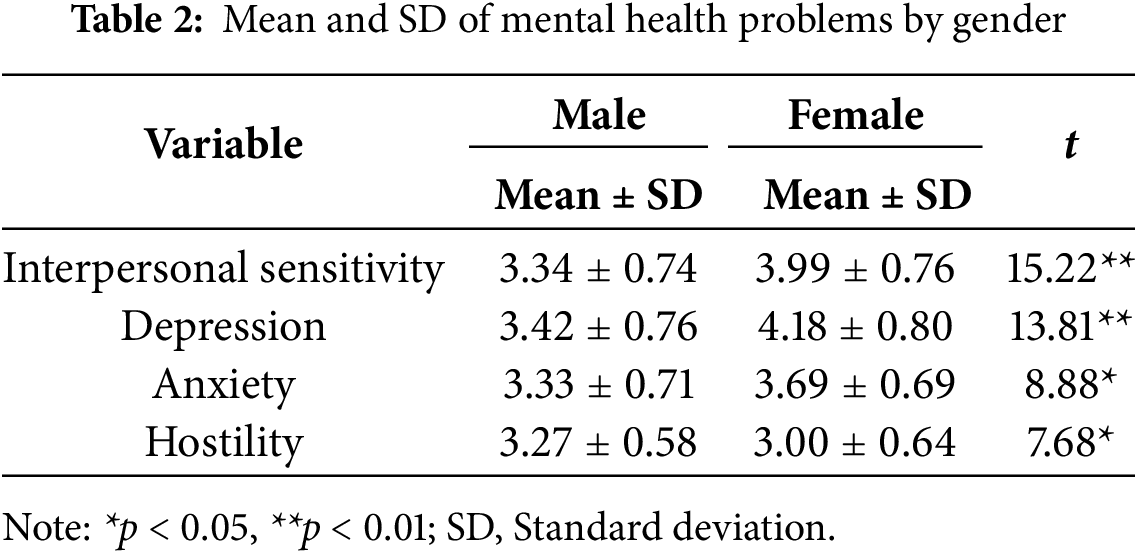

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the t-test and ANOVA to identify mean differences between gender and age in all sub-constructs of mental health problems. In Table 2, there were significant gender differences across most sub-domains. Female adolescents reported higher scores for interpersonal sensitivity (t = 15.22, p < 0.001), depression (t = 13.81, p < 0.001), and anxiety (t = 8.88, p < 0.05), while male adolescents showed higher hostility scores (t = 7.68, p < 0.05).

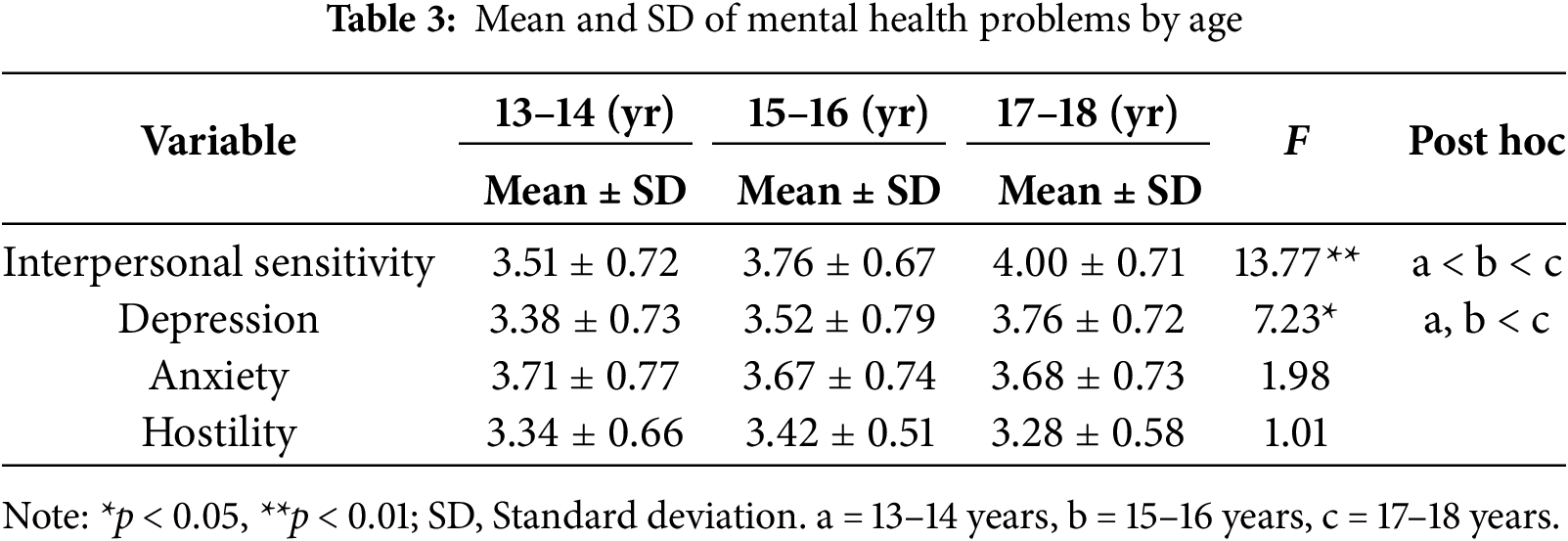

Furthermore, according to Table 3, older adolescents (ages 17–18) had significantly higher scores for interpersonal sensitivity (F = 13.77, p < 0.001) and depression (F = 7.23, p < 0.01), suggesting increased vulnerability during later adolescence.

3.3 Relationships between Mental Health Problems and Psychological Factors

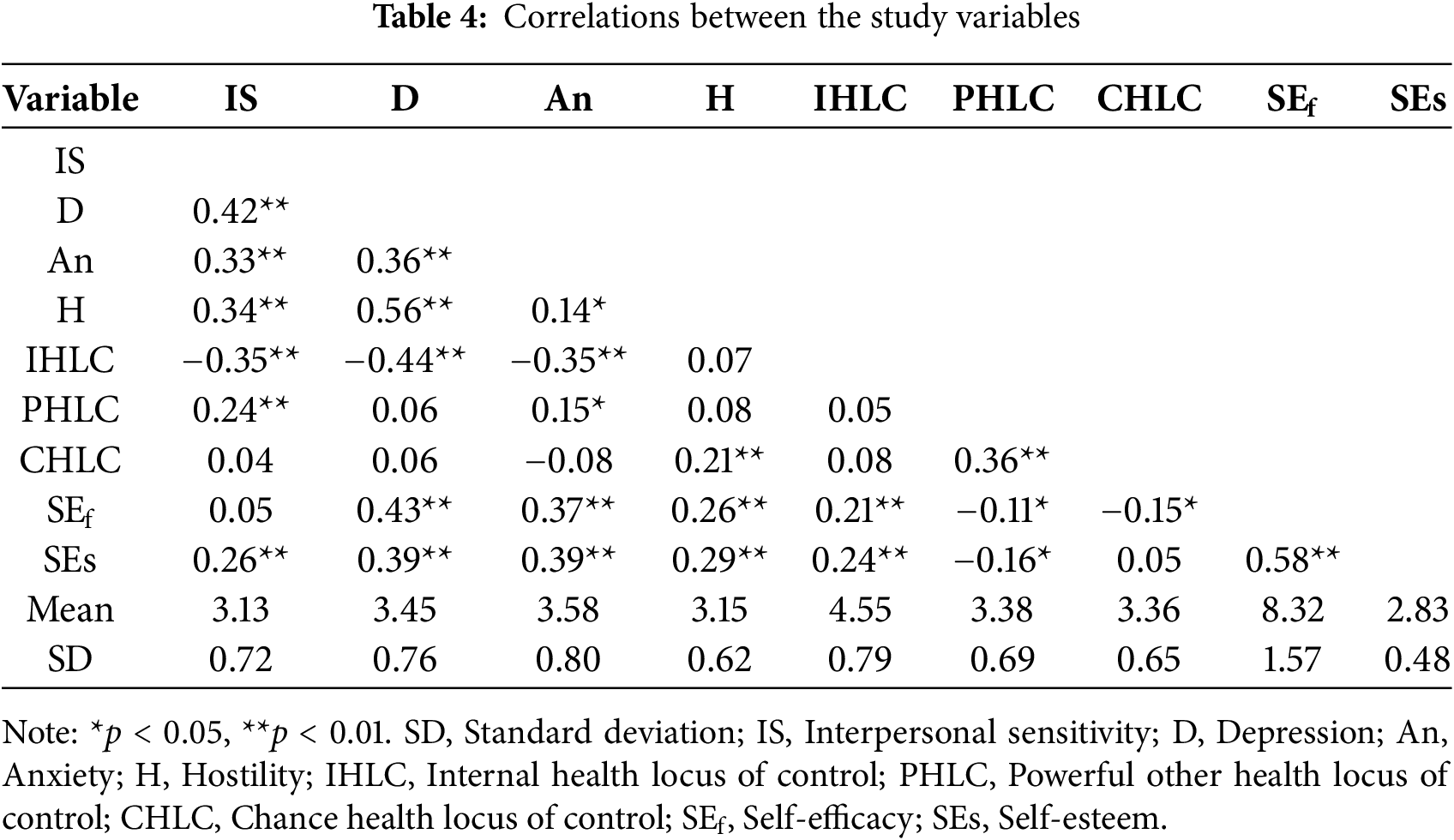

A correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationships between psychological factors and the sub-constructs of mental health problems among adolescents. As shown in Table 4, all psychological factors (self-efficacy, self-esteem, IHLC, PHLC, and CHLC) were significantly correlated with almost all mental health problems (anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility).

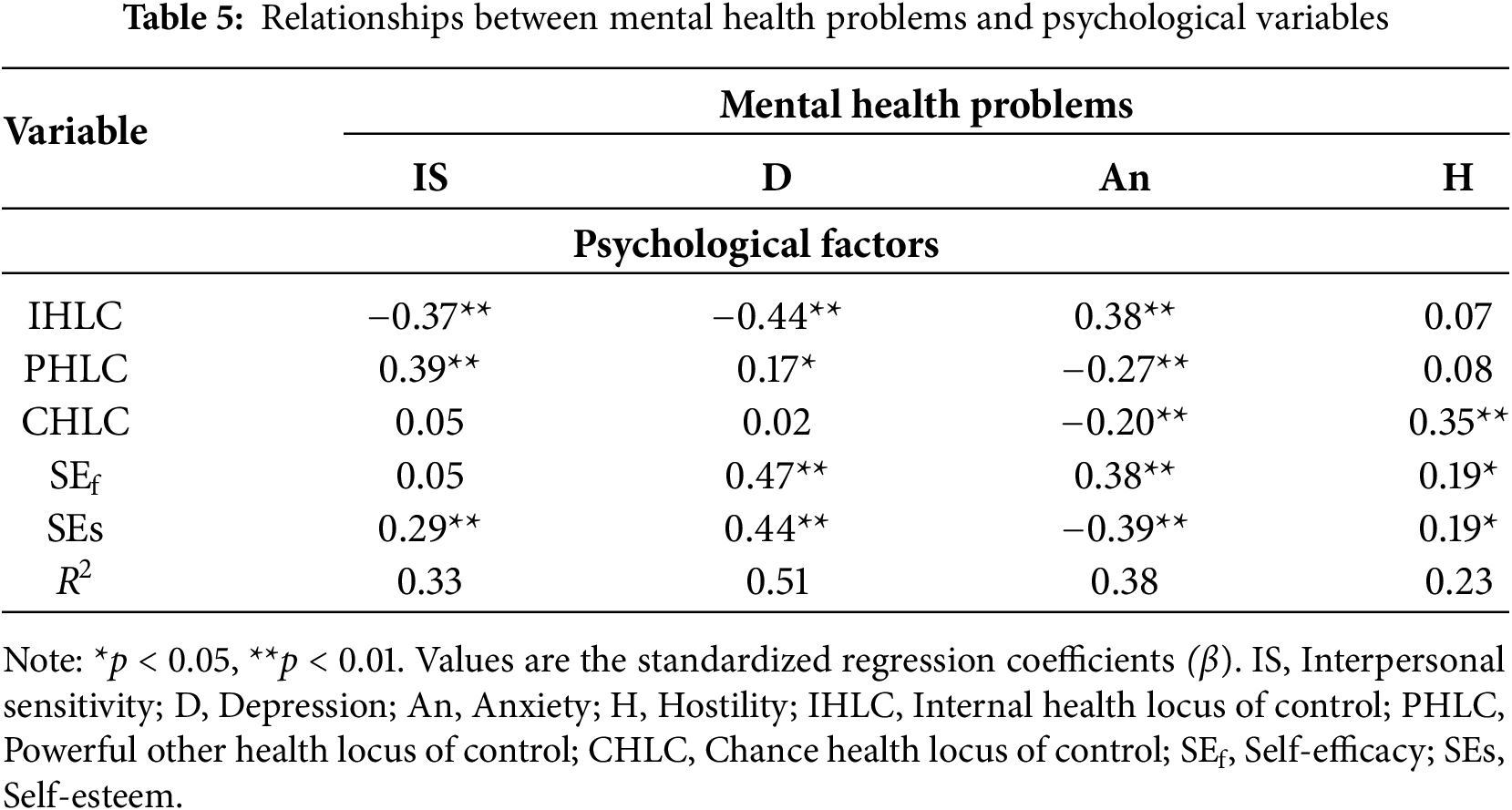

Based on the correlation coefficients revealed in Table 4, the multiple regression analysis was conducted to explore robust and statistically significant pathways from psychological factors to the sub-constructs of mental health problems. In Table 5, all psychological factors exhibited significant predictive power across nearly all mental health problems.

Specifically, psychological variables collectively accounted for 33% of the variance in interpersonal sensitivity (R2 = 0.33), with the PHLC exerting the most pronounced influence (β = 0.39). Moreover, these variables explained 51% of the variance in depression (R2 = 0.51), with self-efficacy (β = 0.47), self-esteem (β = 0.44), IHLC (β = −0.44), and PHLC (β = 0.17) emerging as significant contributors. Concerning anxiety, psychological variables accounted for 38% of the variance (R2 = 0.38), with self-esteem (β = −0.39), IHLC (β = 0.38), self-efficacy (β = 0.38), PHLC (β = −0.27), and CHLC (β = −0.20) demonstrating significant associations. Finally, 23% of the variance in hostility was explained by psychological variables (R2 = 0.23), with CHLC (β = 0.35), self-efficacy (β = 0.19), and self-esteem (β = 0.19) all exerting statistically significant effects.

The present study provides important insights into the psychological underpinnings of adolescent mental health in South Korea. The results underscore the prevalence of psychological distress among adolescents, with interpersonal sensitivity and depression being particularly prominent. These findings are consistent with post-pandemic surveys that report increased emotional strain among youth [8].

The exceptionally high level of interpersonal sensitivity (76.1%) suggests a context in which adolescents may struggle to establish secure peer connections and may be overly reactive to perceived social rejection. In urban Korean settings, where academic achievement and social appearance are highly emphasized, adolescents may internalize social pressures in ways that exacerbate emotional vulnerabilities [30].

Gender differences observed in this study reinforce well-documented patterns in adolescent mental health. Female adolescents showed significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety, which is consistent with evidence suggesting gendered differences in emotional regulation, coping strategies, and neurobiological development [31,32]. These findings suggest that school mental health programs should incorporate gender-sensitive approaches tailored to emotional expression and resilience training. The current study also identified significant age differences in mental health problems, indicating that older adolescents experienced greater levels of depression and interpersonal sensitivity. These results are consistent with previous studies [33,34], which have demonstrated that adolescents in late adolescence exhibit higher levels of depression and anxiety compared to those in early adolescence. This may reflect transitional stress associated with approaching adulthood, academic pressures related to university entrance, and evolving identity challenges. These issues underscore the importance of supporting older adolescents with targeted interventions that address future planning, stress coping, and emotional support [35]. As the gender and age differences in mental health problems revealed in the current study are significant and in the same line with previous studies, Hypothesis 1 is accepted.

More importantly, the current findings indicated that psychological factors—self-efficacy, self-esteem, and health locus of control—were shown to have significant predictive power in explaining mental health problems. It is theoretically grounded that self-efficacy, self-esteem, and locus of control are interconnected concepts within psychology that influence an individual’s behavior, motivation, and overall well-being. The current findings indicated that adolescents with higher self-efficacy and self-esteem reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety, which supports prior research highlighting their protective role in managing life stressors [16,36]. These findings were supported by previous studies, indicating that self-efficacy predicted lower depression levels through enhanced resilience. These results mirror the present study’s findings that adolescents with high self-efficacy reported fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms. Similarly, the role of self-esteem as a protective factor has been well-established [21]. Furthermore, one meta-analysis demonstrated that low self-esteem significantly predicted both depression and anxiety over time and emphasized the buffering role of self-esteem in reducing the mental health deterioration among Korean adolescents facing stress, consistent with our observation that self-esteem negatively correlated with all four mental health domains [20]. Health locus of control has been increasingly recognized as a key predictor of psychological well-being. Lee et al. [25] confirmed that an IHLC was associated with lower depression and anxiety among Korean youth. Adolescents who believed they had personal control over their health outcomes were less likely to experience feelings of helplessness, social withdrawal, and aggression. This finding aligns with the significant correlations between IHLC and reduced depression, interpersonal sensitivity, and anxiety in our sample. As the psychological sub-factors are significantly correlated with the sub-constructs of mental health problems and psychological factors play an important role as a significant predictor in explaining mental health problems, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are also accepted.

This study has several strengths, including its large representative sample and the use of well-validated psychological instruments. Nonetheless, limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and findings may not generalize to rural populations or out-of-school youth. Furthermore, due to the data was obtained from self-reported measures, some biases or prejudices may occur in interpreting and recalling the items. Future research should consider a longitudinal design and integrate qualitative approaches to deepen contextual understanding.

The current findings contribute to the growing literature on adolescent mental health in non-Western contexts and underscore the necessity of culturally tailored mental health preventive strategies. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to track mental health trajectories over time and assess the long-term impact of enhancing psychological strengths during adolescence.

This study provides compelling evidence for the high prevalence and psychological predictors of mental health problems among Korean adolescents. The current findings highlight the need for comprehensive, culturally relevant mental health strategies for Korean adolescents. School-based interventions that foster psychological resilience, promote positive self-concept, and encourage internal control beliefs may be effective in mitigating mental health challenges. Specifically, this study suggests that PE teachers or school nurses should take a more assertive role in promoting and designing risk reduction interventions caused by mental health problems of adolescents.

Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to track mental health trajectories over time and assess the long-term impact of enhancing psychological strengths during adolescence. Furthermore, policymakers, educators, and healthcare professionals must collaborate to develop holistic frameworks for adolescent mental health promotion that are informed by both empirical evidence and sociocultural realities.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge all participants involved in this research and those who helped in recruiting.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Seoul National University of Science and Technology.

Author Contributions: Youngho Kim designed the study. Hakgweon Lee collected data. All authors analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University of Science and Technology (No. 2025-0572). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the adolescents and their legal guardians.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. [Google Scholar]

3. Kenny DT, Job RFS. Australia’s adolescents: a health psychology perspective. Armidale, Australia: University of New England Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

4. Kirkbride JB, Anglin DM, Colman I, Dykxhoorn J, Jones PB, Patalay P, et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry. 2024 Feb;23(1):58–90. doi:10.1002/wps.21160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Jang SY, Kim JH. Academic stress and mental health among Korean adolescents: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Korean J Child Stud. 2022;43(2):97–111. (In Korean). doi:10.5723/kjcs.2022.43.2.97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yoon J, Chun J, Bhang SY. Internet gaming disorder and mental health literacy: a latent profile analysis of Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2024;21(3):300–10. doi:10.30773/pi.2023.0303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li J, Li J, Jia R, Wang Y, Qian S, Xu Y. Mental health problems and associated school interpersonal relationships among adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):12. doi:10.1186/s13034-020-00318-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lin J, Guo W. The research on risk factors for adolescents’ mental health. Behav Sci. 2024 Mar 22;14(4):263. doi:10.3390/bs14040263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dong W, Liu Y, Bai R, Zhang L, Zhou M. The prevalence and associated disability burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents in China: a systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2025;23(58):101556. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2025.101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. 2023 Youth health behavior survey. Cheongju, Republic of Korea: KDCA; 2023. [Google Scholar]

11. Field NP, Filanosky C. Continuing bonds, risk factors for complicated grief, and adjustment to bereavement. Death Stud. 2010 Jan;34(1):1–29. doi:10.1080/07481180903372269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

13. Robinson TM. Self-efficacy, self-esteem and locus of control relationship with performance of air force first sergeants [master’s thesis]. Cypress, CA, USA: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses; 2019. [Google Scholar]

14. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

15. Spagnolo J, Champagne F, Leduc N, Rivard M, Piat M, Laporta M, et al. Mental health knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy among primary care physicians working in the Greater Tunis area of Tunisia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018 Oct 26;12(1):63. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0243-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Schönfeld P, Brailovskaia J, Bieda A, Zhang XC, Margraf J. The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: mediation through self-efficacy. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Park S, Lee E. The role of self-efficacy and peer support in adolescent mental health: evidence from Korea. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;147(1):106855. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rosenberg M. Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

19. Muris P, Otgaar H. Self-esteem and self-compassion: a narrative review and meta-analysis on their links to psychological problems and well-being. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023 Aug 3;16:2961–75. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S402455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(1):213–40. doi:10.1037/a0028931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Song J, Yang J, Yoo S, Cheon K, Yun S, Shin Y. Exploring Korean adolescent stress on social media: a semantic network analysis. Peer J. 2023;11(6):e15076. doi:10.7717/peerj.15076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rotter JB. Social learning and clinical psychology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1954. doi:10.1037/10788-000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wallston KA, Wallston RS, DeVellis R. Development of the multidimensional health locus of control scale. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6(1):160–70. doi:10.1177/109019817800600107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bartsch L, Fiebig N, Strauß S, Angermaier A, Smith CA, Reuter U, et al. Translation of multidimensional health locus of control scales, Form C in patients with headache. J Clin Med. 2024;13(14):4239. doi:10.3390/jcm13144239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lee DJ, So WY, Lee SM. The relationship between Korean adolescents’ sports participation, internal health locus of control, and wellness during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 13;18(6):2950. doi:10.3390/ijerph18062950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li W, Zhao Z, Chen D, Kwan MP, Tse LA. Association of health locus of control with anxiety and depression and mediating roles of health risk behaviors among college students. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 4;15(1):7565. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91522-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kim KL, Won HT, Kim KY. Standardization study of symptom checklist-90 in Korea I: characteristics of normal responses. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1978;17(4):449–58. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

28. Kim YH. Adolescents’ perceptions with regard to health risks, health profile and the relationship of these variables to a psychological factor—a study across gender and different cultural settings [dissertation]. Wollongong, NSW, Australia: University of Wollongong; 1998. [Google Scholar]

29. Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychol Rep. 1982;51(2):663–71. doi:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Choi DH. Impact of social media use on the life satisfaction of adolescents in South Korea through social support and social capital. Sage Open. 2028;14(2):63. doi:10.1177/21582440241245010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lim M, Kim HS, Lee H. Gender differences in adolescent depression and coping mechanisms. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(12):e92. (In Korean). doi:10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Campbell OLK, Bann D, Patalay P. The gender gap in adolescent mental health: a cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM Popul Health. 2021;13(4):100742. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Clarkin J, Heywood C, Robinson LJ. Are younger people more accurate at identifying mental health disorders, recommending help appropriately, and do they show lower mental health stigma than older people?: age differences in mental health disorder recognition. Ment Health Prev. 2024;36(11):200361. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2024.200361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Rega A, Nappo R, Simeoli R, Cerasuolo M. Age-related differences in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 2;19(9):5532. doi:10.3390/ijerph19095532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cho HH, Lee JH. A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of mindful meditation: focused on ACT and MBSR. Korean J Stress Res. 2017;25(2):69–74. (In Korean). doi:10.17547/kjsr.2017.25.2.69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yudiati EA, Sugiharto DYP, Purwanto E, Sunawan. Analysis of self-efficacy and resilience as determinants of psychological well-being in situations of psychological stress in students. Multidiscip Rev. 2025;8(9):2025274. doi:10.31893/multirev.2025274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools