Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Relationship between Resilience and Physical Activity in Adolescents: The Role of Family Functioning

1 Department of Sports Science, College of Education, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, China

2 Department of Child Health Care, Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, National Clinical Research Center for Child Health, Hangzhou, 310052, China

3 Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Research, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, AB T2S 3C3, Canada

4 Department of Oncology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 4N2, Canada

5 Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Jane Jie Yu. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1221-1235. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069810

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Physical inactivity among adolescents has become a global public health challenge, with over 80% failing to meet the recommendations of the WHO for activity levels. Existing research predominantly examines how physical activity (PA) enhances resilience, while the predictive role of resilience in PA, particularly its interaction with family factors, has received limited attention. This study aimed to examine the associations between resilience and PA among adolescents, focusing on family functioning and gender differences. Methods: In this cross-sectional study, a total of 909 Chinese adolescents (463 males and 446 females, aged 13.3 ± 0.5 years) completed the following validated self-report instruments: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale with 10 items, the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children, and the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II-Chinese version that was used to categorize family functioning into three types (i.e., lower, balanced, and higher). The generalized linear mixed-effect model (GLMM) was used to determine the contribution of resilience and its interaction with family functioning type on PA after adjusting for age and gender. Results: Males presented significantly higher resilience and PA levels (both p < 0.001) as well as better family functioning (p < 0.01) than females. Compared with the lower functioning group, participants from higher-functioning families showed superior resilience and PA (both p < 0.001). The GLMM analysis revealed a positive relationship between resilience and PA (p < 0.001), where the lower functioning group was significantly weaker than the higher functioning group. Conclusion: Resilience and PA in adolescents vary across gender and family functioning type, with males and adolescents from better-functioning families outperforming their peers. Resilience is a positive predictor of PA in adolescents, with family functioning type being a crucial moderator of such a relationship.Keywords

Regular physical activity (PA) has many health benefits, which include both physical and mental health, as well as psychological well-being [1]. Adolescence is typically conceptualized as the transitional period from childhood to (emerging) adulthood, spanning 10–19 years of age [2]. This period is critical for the formation of lifelong habits that may play a significant role in fostering healthy lifestyles in adulthood [3]. Individuals’ behaviors, including PA participation during their teenage years, can establish the behavior patterns that persist into adulthood as individuals make numerous lifestyle choices throughout this developmental stage [4,5]. However, a considerable number of adolescents around the world are facing physical inactivity [6]. As early as 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a global action plan on PA promotion, aiming at reducing the global rate of physical inactivity among adolescents and adults by 15% by 2030 [7]. Yet, the global trend of physical inactivity among adolescents has not seen significant improvement. The latest report by WHO showed that 81% of adolescents aged 11–17 years do not meet the PA recommendation (i.e., engage in moderate-to-vigorous PA for at least 60 min per day) [8], which may lead to their current and future health risks.

Recognizing that adolescent health behaviors are shaped by a complex array of factors, including personal attributes and environmental conditions, it becomes clear that adopting a single-factor approach to this issue is inadequate [9]. Over the last decade, an increasing number of studies and policies have begun to focus on the impact of family factors on individual health promotion and advocate for future public health to place greater emphasis on family-targeted interventions, particularly creating conditions to improve PA levels among adolescents [10,11]. This focus could represent a significant direction for further enhancing health-promoting lifestyles among adolescents worldwide. Moreover, the interplay between family-level factors (e.g., family functioning) and individual-level factors (e.g., resilience) and how these factors work together to influence adolescents’ PA is not fully understood. Therefore, to improve PA levels among adolescents, it is important to explore a comprehensive perspective that includes both family and individual factors to understand PA correlates.

1.1 Resilience as a Crucial PA Correlate

Resilience is a positive psychological quality that enables individuals to overcome adversity and thrive positively [12]. Substantial evidence has demonstrated that PA is closely linked to the dimensions of goals, cognition, self-efficacy, and external support, while resilience is strongly correlated with these dimensions [13,14]. In the past, research has explored the relationship between PA and resilience in adolescents and found a positive correlation [15]. One study proposed that PA may facilitate resilience by strengthening individual brain regions as well as large-scale neural circuits to improve emotional and behavioral regulation [16]. In contrast, resilience may be a facilitator of PA engagement. For instance, a recent study has found that university students with high resilience can address challenges in physical exercise with clear goal orientation and perseverance in overcoming difficulties, combined with self-confidence and a sense of joy, accomplishment, and satisfaction from the exercise experience, which may eventually make it easier to enhance adherence to exercise and accomplish long-term PA participation goals [17]. Yet, empirical research on the role of resilience in promoting PA participation among adolescents is still lacking.

1.2 The Role of Family Functioning for PA in Adolescents

Evidence has demonstrated that family plays a major role in shaping adolescents’ health behaviors, including PA [18]. According to the family systems theory by Murray Bowen, the family is viewed as an interdependent system in which any interactions and changes among family members not only influence the balance of the whole system but also significantly impact the behavior of each member [19]. For families to effectively support children’s developmental needs, optimal family functioning is essential.

Family functioning refers to the family’s ability to deal with everyday life and cope effectively with problems and changes, including the effective emotional bonding between family members, family communication, and the management of external events [20], which is an important variable for measuring the overall performance of a family [21]. According to the Circumplex Model of the family system proposed by Olson, adaptability and cohesion are the core indicators to assess family functioning [22]. Family adaptability is defined as the ability of a family to adapt to problems arising from family circumstances and different developmental stages, while family cohesion is defined as the emotional bonding that family members have toward one another [22].

Based on the status of adaptability and cohesion, families can be further categorized into certain types of family functioning with specific characteristics, thereby evaluating family functioning from a relatively holistic view [23]. Previous research has highlighted the importance of family functioning for PA in adolescents [24], yet it is still necessary to specifically explore whether and how adolescents’ PA is influenced by their family functioning type.

1.3 Interactions among Resilience, Family Functioning, and PA in Adolescents

The exploration of interactions among resilience, family functioning, and PA in adolescents is necessary, as adolescents’ resilience may not only be closely related to PA but can also be shaped by family functioning. Resilience can be influenced by a complex interplay of factors and shaped by specific cultural and social contexts (like family) in which individuals are embedded [25]. According to the Social Support Theory, strong family relationships, as essential interpersonal networks, are potential sources of social support with both direct and indirect impacts on individuals’ psychological health and well-being [26]. Furthermore, as indicated by Self-Determined Theory, strong family functioning boosts psychological resilience in adolescents by satisfying their basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which in turn strengthens self-efficacy, emotion regulation, and goal persistence [27]. Recent research highlighted the importance of preventing health problems by enhancing resilience-related factors in individuals through their families [28]. Additionally, a systematic review found that family-based interventions on strengthening resilience can reduce adolescents’ risk of psychopathology following childhood adversity [29]. However, the interplay between resilience, family functioning, and PA among adolescents remains underexplored. It is still unclear whether and how family functioning interacts with resilience and PA in adolescents.

In summary, despite the recognized importance of promoting PA participation among adolescents, there remains a knowledge gap on how to design family-based interventions, which requires understanding family-level and individual-level factors influencing PA. Hence, the present study aimed to investigate the associations of PA with resilience and family functioning in adolescents and to examine the potential moderating effects of family functioning type in the relationship between resilience and PA. We posited two hypotheses: (Hypothesis 1) there would be significant differences in resilience and PA among adolescents by gender and family functioning type, and (Hypothesis 2) resilience would be positively correlated to PA significantly, and such a relationship would be moderated by family functioning type after adjusting for key confounders. The findings from the present study will contribute empirical insights into the impact of family functioning and its interaction with resilience and PA in adolescents. Furthermore, such knowledge will facilitate effective family-centered interventions aimed at promoting PA and health among adolescents.

This study utilized a cross-sectional design, complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Reference No: 2024-IRB-0419-P-01). Written informed consents were received from all the participants and their parents for participation.

A total of 912 Chinese adolescents aged 12–16 years were voluntarily recruited from two public secondary schools in Zhejiang Province, China, in October 2024, using a purposeful sampling method. Three participants were removed during data processing due to incomplete data. Eventually, data from 909 participants (including 463 males and 446 females) with a mean age of 13.3 years (standard deviation [SD] = 0.5) were included in data analyses.

All outcomes and demographic characteristics were measured using self-report questionnaires completed by the participants.

PA was assessed using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C). PAQ-C has been demonstrated to have acceptable validity, reliability [30], and practicality as an appropriate instrument for use with participants who are currently in the school system and have recess as a regular part of their school week (grades 4–8; approximately ages 8–14) [31]. The questionnaire is a self-administered tool that utilizes a 7-day recall method to assess general moderate to vigorous PA levels during the school year. PAQ-C comprises nine items evaluating the participants’ levels of PA in different periods on a typical school week using a 5-point scale, including spare time, at school, recess, lunch break, physical education classes, after school, in the evenings, and on weekends. The total PAQ-C score was assessed by the mean score of these nine items, with a higher score representing a higher level of PA. The Chinese version of PAQ-C has been applied in Chinese children and adolescents with good reliability [32]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the PAQ-C was 0.87.

Participants’ resilience was evaluated with the Chinese version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10). CD-RISC is a concise, self-report instrument for measuring resilience that has sound psychometric properties [33], and the total score of the CD-RISC can be accurately estimated using the abbreviated CD-RISC-10 [34]. CD-RISC-10 comprises 10 items and is rated on a 5-point scale (0 = not true at all, 1 = rarely true, 2 = sometimes true, 3 = often true, and 4 = true nearly all the time). The total CD-RISC-10 score is obtained by adding up the points for all 10 items, ranging from 0 to 40, with a higher total score indicating greater resilience. The Chinese version of CD-RISC has been validated as reliable and used among Chinese youth [35]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CD-RISC-10 was 0.97.

Participants’ family functioning was evaluated using the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale, second edition, Chinese version (FACES II-CV) [36]. FACES is one of the effective family assessment tools with good psychometric properties and has been used in numerous projects and clinical evaluations [37]. FACES II-CV comprises 30 items, with 14 items assessing family adaptability and 16 items evaluating family cohesion. The participants were asked to rate each item concerning their family situations using a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 to 5, which is expressed as “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “always”, and to reverse rate the reverse-rating items. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha achieved 0.95 for the whole FACES II-CV scale and 0.92 and 0.86 for the subscales of adaptability and cohesion, respectively.

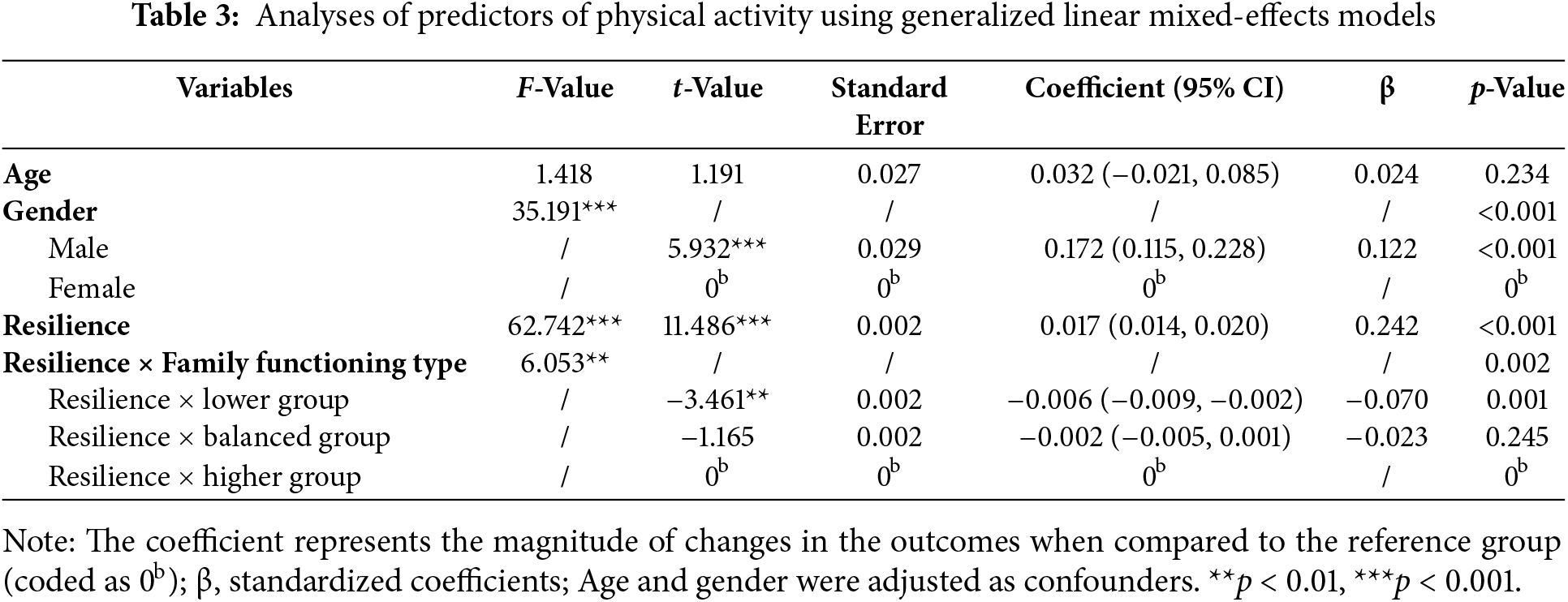

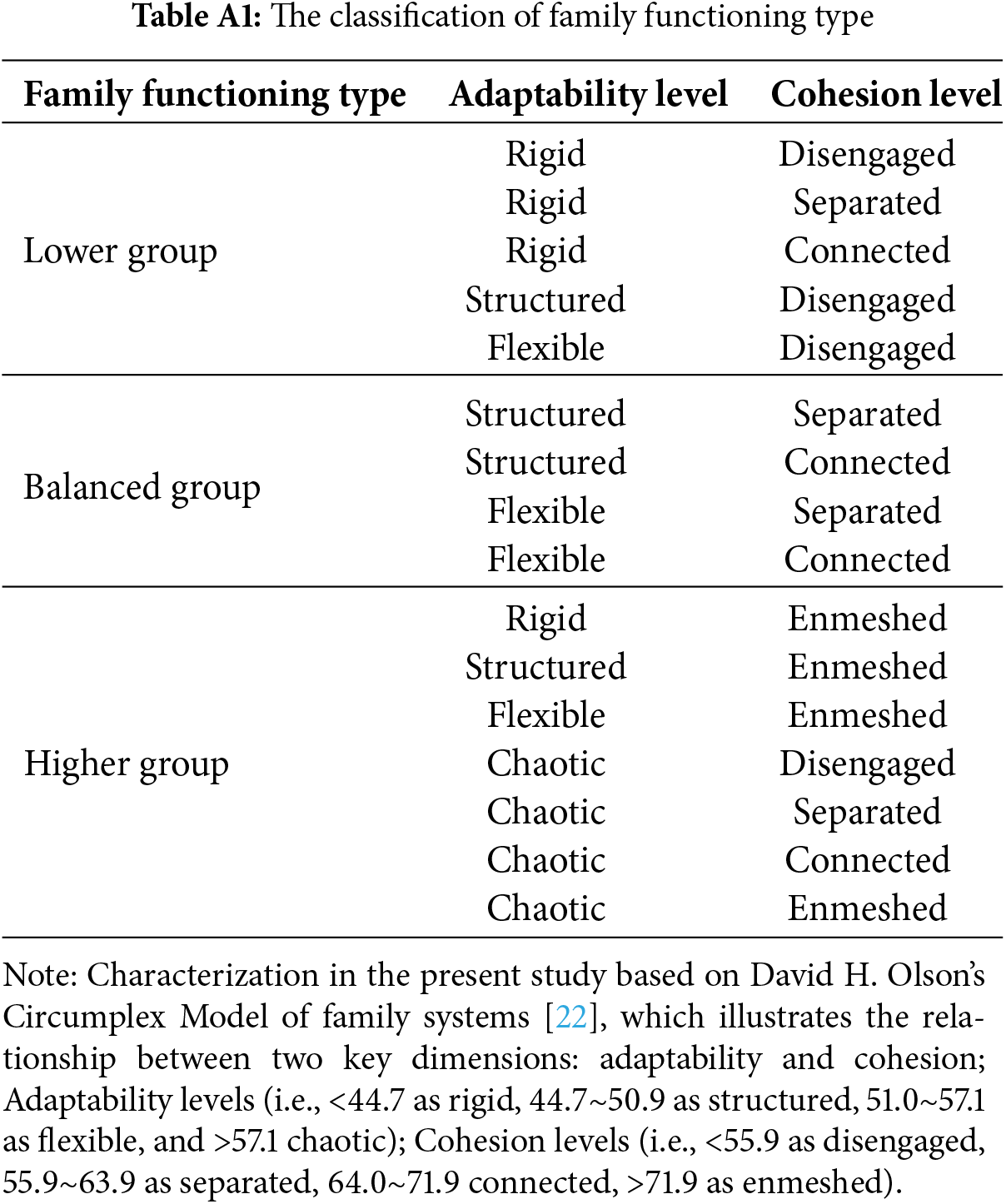

The raw scores for adaptability and cohesion were calculated separately by summing the scores of all corresponding items in each subscale. Subsequently, each family was classified into different levels in terms of adaptability (i.e., <44.7 as rigid, 44.7~50.9 as structured, 51.0~57.1 as flexible, and >57.1 chaotic) and cohesion (i.e., <55.9 as disengaged, 55.9~63.9 as separated, 64.0~71.9 connected, >71.9 as enmeshed) by referring to cut-off points used in previous research [38] and the Circumplex Model of family systems by Olson [22]. In the present study, the outcome of family functioning was family functioning type categorized into three groups, namely, the lower group, balanced group, and higher group. Each family was classified into a specific group based on predefined combinations of adaptability and cohesion levels in different groups by referring to previous research [23] (see Appendix A). For instance, a chaotic and enmeshed family was classified into the higher group and determined as having higher family functioning.

Descriptive analyses were applied to all outcomes. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to examine gender differences in outcomes with continuous data, including resilience and PA, while the cross-tabulation and chi-square test were used to evaluate the distribution of males and females across different family functioning groups (i.e., lower, balanced, and higher). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare differences in resilience and PA across family functioning types. The Box-Cox transformation was applied to the dependent variable of PA to meet the assumptions required by the data analysis, improving the symmetry and variance stability of its distribution. Generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMM) were further used to explore the associations between resilience and PA in males and females with different family functioning types, with PA serving as the dependent variable. Specifically, the potential contribution of resilience and its interaction with family functioning type were examined after adjusting for key confounding factors (i.e., age and gender). The distribution of the linear model and the identity correlation function with fixed effects was selected. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3.1 Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

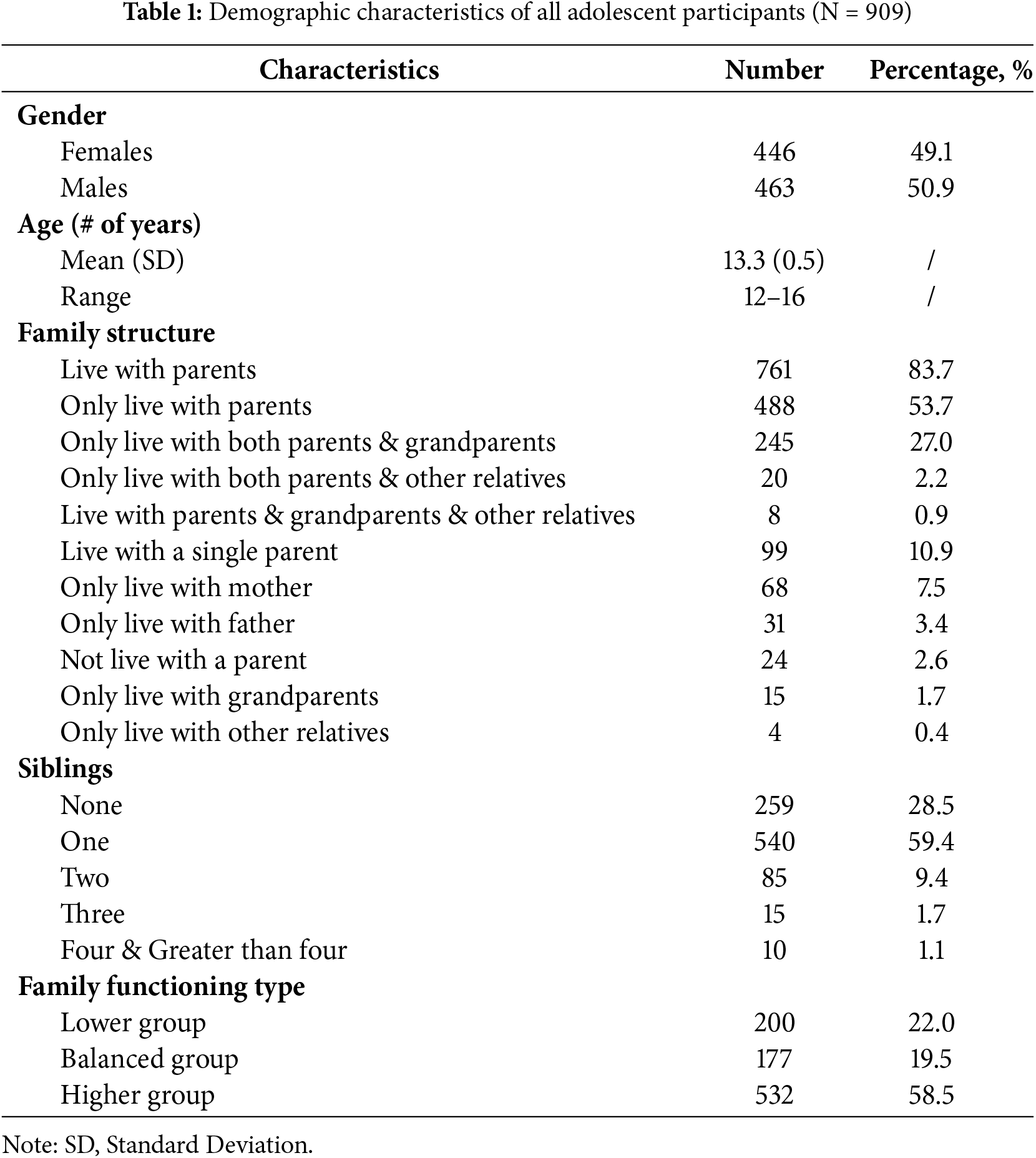

As shown in Table 1, data from 909 participants (mean age, 13.3 years; 49.1% females) were included in the statistical analyses.

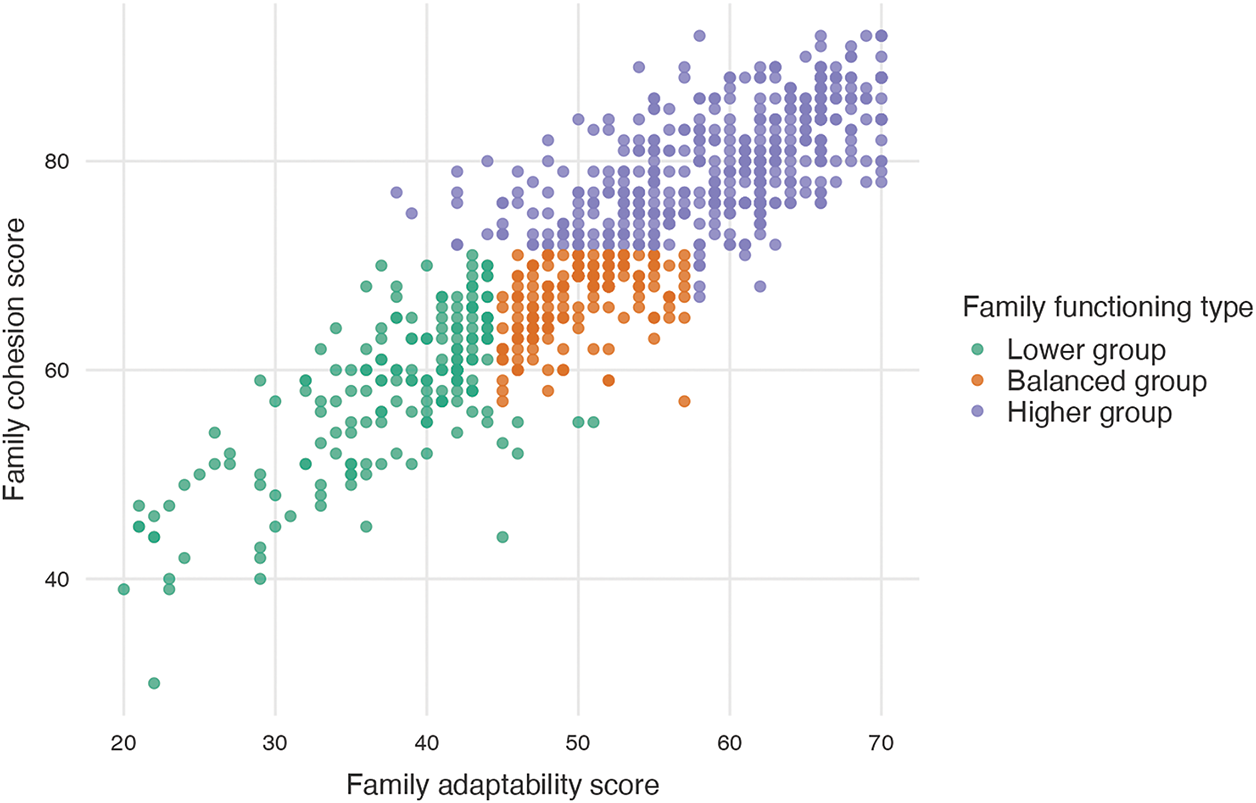

The family structure statistics revealed that most of the participants (83.7%) resided with parents, including 488 (53.7%) in nuclear family arrangements and 245 (27.0%) in multigenerational households with grandparents. Single-parent households represented 10.9% of cases, with 7.5% of adolescents living with only their mother and 3.4% with only their father. Notably, 24 adolescents (2.6%) reported no cohabitation with either parent, comprising 15 (1.7%) living exclusively with grandparents and 4 (0.4%) with other relatives. Regarding the number of siblings, 59.4% of the participants had one sibling, 9.4% had two siblings, and 1.1% had four or more siblings. When these characteristics were compared between males and females, no significant gender difference was evident (all p > 0.05). Additionally, the number of families in the higher functioning group was the largest (58.5%), followed by the lower functioning group (22.0%) and the balanced functioning group (19.5%), with the family functioning type distribution among participants categorized as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Sample distribution of different family functioning types

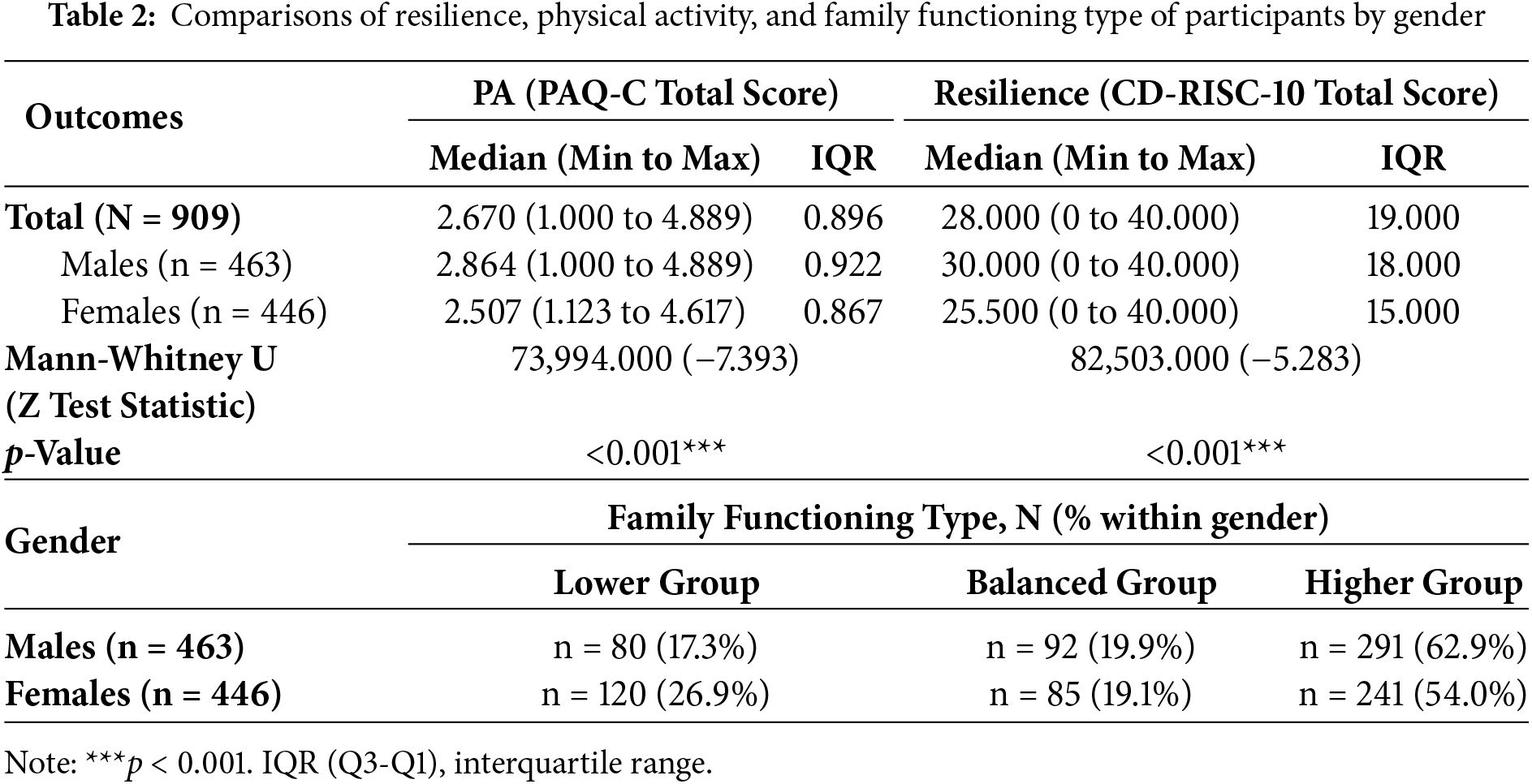

3.2 Gender Differences in PA, Resilience, and Family Functioning

As shown in Table 2, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test on the comparison of participants’ resilience and PA by gender, in which males demonstrated significantly greater scores in resilience and PA when compared to females (both p < 0.001). Additionally, the results of the cross-tabulation analysis showed a significant gender difference in the distribution of males and females across the three family functioning groups (χ2 = 12.663, p < 0.01). Specifically, the proportion of males reporting lower-functioning families was significantly lower than that of females, while the proportions reporting balanced and higher-functioning families were higher.

3.3 Differences in Adolescents’ Resilience and PA across Family Functioning Types

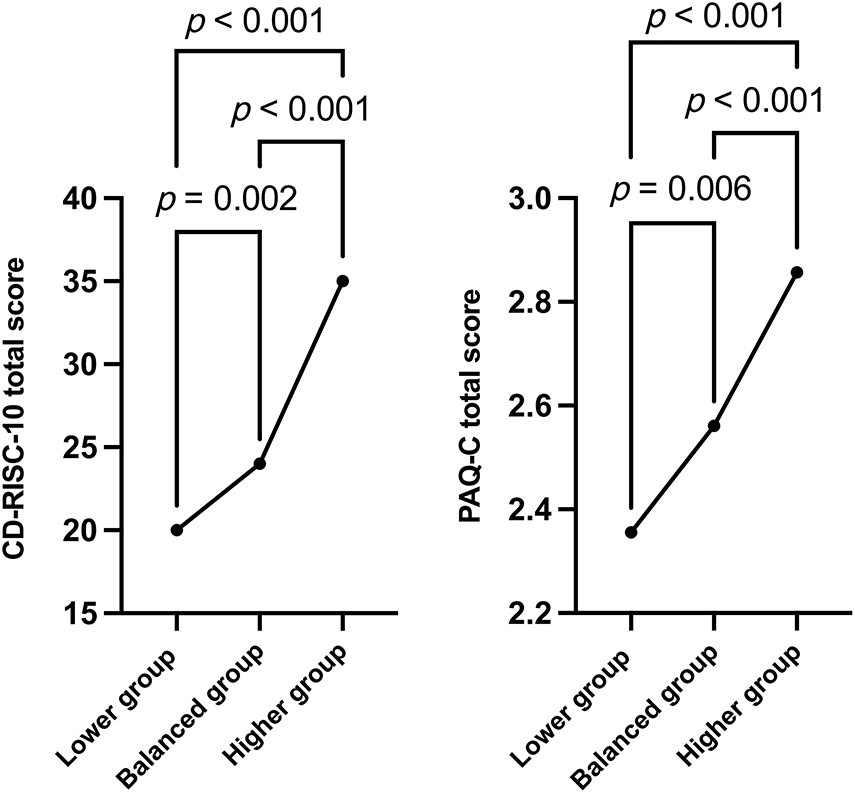

The results of the Kruskal-Wallis Test showed a significant main effect of family functioning type in both resilience (χ2 = 263.232, p < 0.001) and PA (χ2 = 91.591, p < 0.001). Furthermore, pairwise comparisons of median scores for resilience and PA, respectively, shown in Fig. 2, indicated that the lower functioning group had significantly lower resilience and PA when compared to both the balanced (both p < 0.01) and higher (both p < 0.001) functioning groups, while the balanced functioning group had significantly lower resilience and PA than the higher functioning group (both p < 0.001). These findings demonstrate that those participants from families with better functioning have higher levels of resilience and PA.

Figure 2: Kruskal-Wallis comparison of resilience and physical activity medians across family functioning types

As shown in Table 3, the GLMM analyses revealed that resilience (F = 62.742, p < 0.001) was a significantly positive predictor of PA after adjusting for key confounders, and the family functioning type (F = 6.053, p < 0.01) moderated such a relationship. Furthermore, the relationship between resilience and PA in the lower functioning group was significantly weaker than that in the higher functioning group.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the associations of PA with resilience and family functioning in adolescents and to examine the potential moderating effect of family functioning type in the relationship between resilience and PA in the context of China. Our findings demonstrated that (1) resilience and PA in adolescents significantly vary across gender and family functioning type, with males and adolescents from higher-functioning families exhibiting higher levels of resilience and PA; and (2) resilience is positively correlated to PA, in which family functioning type is a significant moderator. Our two hypotheses (Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2) were fully supported by these findings.

Our findings reveal significant gender differences in resilience and PA among adolescents, with males outperforming females, which is consistent with previous research demonstrating that males tend to show a relatively higher level of PA than females [39]. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that, when compared to females, males tend to perceive themselves as having a higher level of personal competence, self-efficacy, and self-awareness that are closely linked to psychological resilience [40] and have more PA engagement [41]. Regarding the resilience, recent evidence showed that there was no statistical significance by gender [42], which is different from our findings. It may be influenced by diverse sample contexts and regional specificity, which should be further explored in future investigations.

To a certain extent, gender differences might be attributable to societal expectations on necessary psychological traits for different genders in China under the traditional Confucian culture, in which males, rather than females, are generally expected or encouraged to possess resilient qualities and be physically active. From a young age, males are often encouraged to be strong, independent, and active, while females are socialized toward nurturing and passive roles. This may be shaped by interconnected environmental impacts, encompassing microsystemic interactions across familial, educational, and societal spheres. For instance, parental behaviors, like praising males for toughness and discouraging emotional expression, and tacit permission for females to show vulnerability [43]. This gender stereotype that stems from traditional culture forms can be highlighted by educational settings with the impact of peer support [44], and further reinforced through media, where males are frequently depicted as independent, rational, powerful, and active, whereas females are portrayed as emotionally expressive or peaceful [45]. Additionally, we found that males are more likely to perceive their family as having better family functioning than females do, which is worth further investigation in the future. Further research should not only promote resilience and PA but also the improvement of gender equity in physical and psychological health among adolescents.

We found that participants from families with higher functioning tend to have better resilience and higher PA than those from families with lower functioning, which is in line with previous research indicating that the relationship between family functioning and adolescents’ health behaviors may be linear [46]. While the positive correlation between family functioning and adolescents’ resilience has been proven by previous research, the potential mechanisms remain understudied. For example, self-efficacy, satisfaction with life, and other relevant variables may be influential in such a relationship indirectly. In addition, although recent evidence shows significant associations of PA in adolescents with multiple domains of family functioning, the results represent only statistically small amounts of correlation [47]. Therefore, additional evaluation and validation are warranted.

To some extent, families with better functioning may provide a more supportive, harmonious, and caring atmosphere for the development of adolescents. In this case, adolescents are more likely to cultivate positive psychology (e.g., a better sense of personal control and ability to cope with stress) and obtain social support for PA participation [48]. In contrast, poor family functioning is characterized by strain, conflict, violence, and weak cohesion, often failing to provide adolescents with adequate emotional support, which may impair their behavioral control, heightened risk of depression, and increased vulnerability and reduced stress-coping capacity [49]. Additionally, families with low functioning often fail to give adequate emotional validation or encouragement. This potentially negative parenting style may diminish children’s self-efficacy and motivation to engage in PA [50], with such households more likely to lack resources (e.g., funds, time) and organizational capacity to offer stable exercise conditions that may further inhibit PA behaviors.

Our results also indicate that resilience is a positive predictor of PA in adolescents, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that resilience is a crucial factor in motivating individuals to engage in regular exercise [51]. Of note, the importance of bidirectional effects should be further recognized. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis pointed to a significant positive correlation between PA and resilience among young students, with PA exerting a positive impact on resilience, and in turn, resilience may perform a promotional role in PA engagement [52]. This suggests attention towards the bidirectional relationship complicating the causal direction in future research, such as clarifying the causal weighting of the complex relationship and constructing a PA-resilience reinforcing loop.

We also discovered that family functioning type is an important moderator for such a relationship. Specifically, the amplitude of the link between resilience to PA is notably diminished in families with lower functioning compared to families with higher functioning. We speculate that the opportunities for developing psychological adaptability and fostering the relationship between resilience and behaviors may be reduced when a family does not function well. Our findings highlight the importance of family functioning in building a favorable status of resilience and PA among adolescents. We suggest that future research could place a greater emphasis on the impact of family environment on adolescents’ PA, particularly on exploring factors related to family functioning, as well as designing effective intervention programs to improve family functioning. For instance, low-functioning families should be provided with additional support and resources, such as family counseling and designed family communication training programs to enhance family cohesion and offer opportunities for family members and youth to participate in physical activities together.

In China, the “double reduction” policy was launched by the Ministry of Education in 2021, which aims to encourage all school-aged students to have more spare time after school and opportunities to engage in out-of-school activities (e.g., PA) to promote physical and mental health in childhood. Since then, the role of family in healthy development and high-quality education among adolescents has become more important [53]. Families with better functioning probably employ more advantageous parenting styles that can cultivate more psychologically positive, behaviorally healthy, and competitive adolescents. Therefore, researchers and caregivers should pay more attention to the disparities in family functioning and their negative impacts on healthy development for adolescents.

This empirical study investigates the complex interplay between resilience and family functioning in their influence on PA among adolescents in developing Eastern countries underpinned by a robust theoretical framework (i.e., the Circumplex Model of the family system). Nevertheless, we also acknowledge that limitations exist in the present study. First, the use of a cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, potentially obscuring whether observed relationships reflect true causation or mere correlation. Future studies are warranted to further examine their relationships in cohort or intervention studies. Second, to facilitate the feasibility of recruiting a large sample and smooth implementation, PA was reported by the participants using a questionnaire. Although the questionnaire is well recognized and has been widely used in the research field, it may cause recall bias due to its self-report nature, with the risk of misjudgment and a problem of social desirability bias. Third, our participants were recruited from one province located in eastern China, where economic development has progressed relatively well. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other areas in China and other countries with different sociocultural contexts.

Examining the influence of family factors on individual health has emerged as a crucial direction in global public health promotion. Previous studies have highlighted the positive association between resilience and PA, suggesting that resilient adolescents are more likely to engage in regular PA. Our study extends this understanding by exploring the important role of family functioning and its interaction with resilience in this relationship. Family functioning may have potential effectiveness in enhancing adolescents’ resilience, which in turn promotes PA. The present study indicates the possible influence of the family in fostering adolescent health behaviors, emphasizing the potential of resilience and family factors, as well as their interactions, in the development of PA, thereby offering a promising perspective for future research and intervention program development for promoting PA among adolescents.

The present study reveals crucial insights into the complex interplay of resilience, PA, and family functioning in adolescents in the Chinese context. Our results showed that resilience and PA in adolescents vary across gender and family functioning type, with males and adolescents from better-functioning families outperforming their counterparts. We also confirmed that there is a significant and positive relationship between resilience and PA, with family functioning type being a significant moderator of such a relationship. These findings highlight the importance of fostering adolescents’ PA through cultivating resilience and improving family functioning. Furthermore, we recommend that researchers and stakeholders who aim at improving PA among adolescents incorporate the family (either family-centered or family-involved) into their intervention strategies and place more focus on gender disparities.

Acknowledgement: This work is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants who participated in the present study and the staff from the participating schools who assisted in the study implementation.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 22BTY098) with JJY as Principal Investigator. The URL to the sponsor’s website is: http://www.nopss.gov.cn/GB/index.html (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Author Contributions: Dingmeng Mao performed data collection and formal analysis, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; Guannan Bai and Lin Yang interpreted data and critically edited the manuscript; Jane Jie Yu conceptualized this work, designed the methodology, supervised the entire process of research work, and critically edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are included in the manuscript and the additional file. Any additional questions should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Reference No: 2024-IRB-0419-P-01). Written informed consents were received from all the participants and their parents for participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ruiz-Ranz E, Asín-Izquierdo I. Physical activity, exercise, and mental health of healthy adolescents: a review of the last 5 years. Sports Med Health Sci. 2025;7(3):161–72. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2024.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. World Health Organization. Adolescent and young adult health [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions. [Google Scholar]

3. Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Khan MN, Mahmood W, Patel V, et al. Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4):49–60. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. van Sluijs EM, Ekelund U, Crochemore-Silva I, Guthold R, Ha A, Lubans D, et al. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):429–42. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01259-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hallal PC, Victora CG, Azevedo MR, Wells JC. Adolescent physical activity and health: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2006;36(12):1019–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Chen P, Wang D, Shen H, Yu L, Gao Q, Mao L, et al. Physical activity and health in chinese children and adolescents: expert consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(22):1321–31. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2025 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514187. [Google Scholar]

8. World Health Organization. Physical activity [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity. [Google Scholar]

9. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. 2020;4(1):23–35. doi:10.1530/ey.17.13.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 5]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/355463/9789240050945-chi.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

11. World Health Organization. Guidelines on mental health promotive and preventive interventions for adolescents [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336864/9789240011854-eng.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

12. Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Focus. 2004;161(3):195–391. doi:10.1176/foc.2.3.368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. White RL, Vella S, Biddle S, Sutcliffe J, Guagliano JM, Uddin R, et al. Physical activity and mental health: a systematic review and best-evidence synthesis of mediation and moderation studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2024;21(1):134. doi:10.1186/s12966-024-01676-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Özüdoğru A, Canlı M, Yinanç SB. Investigation of relationship between physical fitness and attention levels in athlete children. Kinesiol Slov. 2022;28(1):108–21. [Google Scholar]

15. Marquez J, Francis-Hew L, Humphrey N. Protective factors for resilience in adolescence: analysis of a longitudinal dataset using the residuals approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):140. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00687-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Belcher BR, Zink J, Azad A, Campbell CE, Chakravartti SP, Herting MM. The roles of physical activity, exercise, and fitness in promoting resilience during adolescence: effects on mental well-being and brain development. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6(2):225–37. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yu JJ, Ye JC. Resilience is associated with physical activity and sedentary behaviour recommendations attainment in chinese university students. Complement Ther Clin Pr. 2023;51(19):101747. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2023.101747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Umberson D, Thomeer MB. Family matters: research on family ties and health, 2010–2020. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):404–19. doi:10.1111/jomf.12640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Katafiasz H. Bowen family systems therapy with families. In: Lebow J, Chambers A, Breunlin D, editors. Encyclopedia of couple and family therapy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-15877-8_1147-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Holtom-Viesel A, Allan S. A systematic review of the literature on family functioning across all eating disorder diagnoses in comparison to control families. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(1):29–43. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Q. Family function. In: Zhang K, editor. The ECPH encyclopedia of psychology. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

22. Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J Fam Ther. 2000;22(2):144–67. [Google Scholar]

23. Joh JY, Kim S, Park JL, Kim YP. Relationship between family adaptability, cohesion and adolescent problem behaviors: curvilinearity of circumplex model. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34(3):169–77. doi:10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.3.169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lebron CN, Lee TK, Park SE, St George SM, Messiah SE, Prado G. Effects of parent-adolescent reported family functioning discrepancy on physical activity and diet among hispanic youth. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(3):333–42. doi:10.1037/fam0000386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Masten AS, Cutuli JJ, Herbers JE, Reed M-GJ. Resilience in development. In: Lopez SJ, Snyder CR, editors. The Oxford handbook of positive psychology. 2th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

26. Ell K. Social networks, social support and coping with serious illness: the family connection. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(2):173–83. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00100-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Soenens B, Deci EL, Vansteenkiste M. How parents contribute to children’s psychological health: the critical role of psychological need support. In: Wehmeyer M, Shogren K, Little T, Lopez S, editors. Development of self-determination through the life-course. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2017. p. 171–87. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1042-6_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wen L, Yang K, Chen J, He L, Xiu M, Qu M. Associations between resilience and symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents: examining the moderating effects of family environment. J Affect Disord. 2023;340(1):703–10. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Fritz J, De Graaff AM, Caisley H, Van Harmelen AL, Wilkinson PO. A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:341825. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Biddle SJ, Gorely T, Pearson N, Bull FC. An assessment of self-reported physical activity instruments in young people for population surveillance: project alpha. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

31. Kowalski KC, Crocker PR, Donen RM. The physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) and adolescents (PAQ-A) manual. Coll Kinesiol Univ Sask. 2004;87(1):1–38. doi:10.21831/jpji.v20i1.73750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang JJ, Baranowski T, Lau WP, Chen TA, Pitkethly AJ. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) among Chinese children. Biomed Env Sci. 2016;29(3):177–86. doi:10.3967/bes2016.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kuiper H, van Leeuwen CC, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Post MW. Measuring resilience with the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISCwhich version to choose? Spinal Cord. 2019;57(5):360–6. doi:10.1038/s41393-019-0240-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen W, Liang Y, Yang T, Gao R, Zhang G. Validity and longitudinal invariance of the 10-item connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC-10) in Chinese left-behind and non-left-behind children. Psychol Rep. 2022;125(4):2274–91. doi:10.1177/00332941211013531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Fei L, Zheng Y, Zou D. Family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scale, Chinese version (FACES II-CV). In: Wang X, editor. Mental health rating scale manual. Beijing, China: Chinese Mental Health Journal; 1999. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

37. Priest JB, Parker EO, Hiefner A, Woods SB, Roberson PN. The development and validation of the FACES-IV-SF. J Marital Fam Ther. 2020;46(4):674–86. doi:10.1111/jmft.12423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Cluff RB, Hicks MW, Madsen CHJr. Beyond the circumplex model: I. A moratorium on curvilinearity. Fam Process. 1994;33(4):455–70. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00455.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kretschmer L, Salali GD, Andersen LB, Hallal PC, Northstone K, Sardinha LB, et al. Gender differences in the distribution of children’s physical activity: evidence from nine countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2023;20(1):103. doi:10.1101/2023.04.17.23288558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Venegas-Murillo A, Klomhaus A, Aralis H, Lee K, Rahmanian Koushkaki S, et al. The role of resilience and gender: understanding the relationship between risk for traumatic stress, resilience, and academic outcomes among minoritized youth. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14(S1):S82–90. doi:10.1037/tra0001161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ricardo LIC, Wendt A, dos Santos Costa C, Mielke GI, Brazo-Sayavera J, Khan A, et al. Gender inequalities in physical activity among adolescents from 64 global south countries. J Sport Health Sci. 2022;11(4):509–20. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Guo L, Liang L. Physical activity as a causal variable for adolescent resilience levels: a cross-lagged analysis. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1095999. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1095999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Chaplin TM. Gender and emotion expression: a developmental contextual perspective. Emot Rev. 2015;7(1):14–21. doi:10.1177/1754073914544408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Li M, Huang Y, Sun M. Exploring the structural links between peer support, psychological resilience, and exercise adherence in adolescents: a multigroup model across gender and educational stages. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):2300. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-23308-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liao LL, Chang LC, Lee CK, Tsai SY. The effects of a television drama-based media literacy initiative on taiwanese adolescents’ gender role attitudes. Sex Roles. 2019;82(3):219–31. doi:10.1007/s11199-019-01049-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Green RG, Harris RN, Forte JA, Robinson M. Evaluating FACES III and the circumplex model: 2440 families. Fam Process. 1991;30(1):55–73. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1991.00055.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Forghani Soong Y, Hollman H, Rhodes RE. Association between child and youth physical activity and family functioning: a systematic review of observational studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2025;22(1):101. doi:10.1186/s12966-025-01782-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zurita-Ortega F, Alonso-Vargas JM, Puertas-Molero P, Gonzalez-Valero G, Ubago-Jimenez JL, Melguizo-Ibanez E. Levels of physical activity, family functioning and self-concept in elementary and high school education students: a structural equation model. Children. 2023;10(1):163. doi:10.3390/children10010163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Oltean II, Perlman C, Meyer S, Ferro MA. Child mental illness and mental health service use: role of family functioning (family functioning and child mental health). J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(9):2602–13. doi:10.1007/s10826-020-01784-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Vega-Díaz M, González-García H, De Labra C. Parenting profiles: motivation toward health-oriented physical activity and intention to be physically active. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):205. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01239-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Tang F, Wang W. Influence mechanism of college students’ mental toughness on physical exercise behavior: based on the perspective of habit control and resisting temptation. J Phys Educ. 2024;31(5):53–61. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

52. Qiu W, Huang C, Xiao H, Nie Y, Ma W, Zhou F, et al. The correlation between physical activity and psychological resilience in young students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1557347. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1557347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Sun H, Wang R, Zhang X. Development strategies of school physical education with collaborative empowerment of home, school and community under the “double reduction” policy. J Shenyang Sport Univ. 2022;41(6):28–56. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools