Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social Value and Public Health: Exploring the Impact of Social Connection on the Community Mental Health

1 Department of Geography, Sungshin Women’s University, Seoul, 02844, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Public Administration, Kookmin University, Seoul, 02707, Republic of Korea

3 The Convergence Institute of Healthcare and Medical Science, College of Medicine, Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, 22711, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Youngbin Lym. Email: ,

; Geiguen Shin. Email:

,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Social and Behavioral Determinants of Mental Health: From Theory to Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071482

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: Social connection is widely recognized as a protective determinant of health, yet its direct and indirect effects on mental health remain underexplored. This study examines the relationship between social connection and mental health, focusing on the mediating role of quality of life (QoL) and the moderating effect of regional differences. Methods: We analyzed data from the 2019 Korean Community Health Survey, comprising 229,099 adults. Mental health was assessed through validated measures of depressive symptoms and psychological well-being. Social connection was measured using indicators of interpersonal ties and community participation, and QoL was assessed via self-reported health-related satisfaction across major life domains. Analytical procedures included mediation modeling and subgroup analyses by region, with significance levels set at p < 0.05. Results: The results indicate that social connections are significantly associated with lower stress levels and reduced depressive symptoms, with QoL playing a critical mediating role. Notably, the indirect effect of social connection on mental health via QoL is stronger in rural areas compared to urban regions, highlighting the importance of social cohesion and community support in mental well-being. Among 203,567 adults, greater social participation was associated with lower subjective stress (total effect = −0.052, p < 0.001) and fewer depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 total effect = −0.308, p < 0.001). QoL significantly mediated these associations, with the strongest indirect pathways observed through usual activities (19.2% for stress; 27.6% for depression) and mobility (24.4% for depression). Regional analysis showed stronger mediation in rural areas (up to 26.8% for stress and 32.6% for depression) than in urban areas (8–16% and 14.9–23%). Direct effects remained significant, indicating partial mediation. These findings highlight that social participation enhances mental health directly and indirectly through QoL, particularly in rural contexts. Conclusions: Social connection contributes to better mental health both directly and indirectly through improved QoL, with stronger effects observed in rural communities. These findings highlight the importance of fostering social cohesion and enhancing life quality as strategies for improving population mental health. Policy interventions should adopt context-sensitive approaches that account for regional differences in social resources and service availability.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCommunity mental health is shaped by a complex interplay of biological, psychological, socioeconomic, cultural, environmental, institutional, and political factors. Addressing these determinants requires a multi-sectoral approach that prioritizes mental health services, reduces social inequalities, and fosters supportive environments for psychological well-being. Over the past several decades, substantial research has aimed to understand the various contributors to mental health, demonstrating that conditions such as depression and anxiety are influenced by diverse contextual factors [1,2,3,4].

While recent research has examined medical factors influencing mental illness, comparatively less attention has been given to non-medical determinants. Studies suggest socioeconomic status significantly impacts mental health, with poverty, unemployment, and lack of healthcare access contributing to psychological distress [1]. Cultural, environmental, and societal conditions—such as urbanization and chronic discrimination—also exacerbate risk [2,3,4]. Environmental factors, such as living in high-crime neighborhoods or experiencing chronic discrimination, further exacerbate mental health risks. For example, urbanization has been linked to increased prevalence of anxiety and depression [5,6,7].

Traditional approaches to mental health have often emphasized risk factors such as stress, trauma, and socioeconomic adversity. While these factors are undeniably significant, research exploring the role of positive behaviors in shaping mental health outcomes remains relatively underdeveloped. Despite the centrality of risk factors, mental health is also shaped by positive social conditions. In particular, social connection—encompassing the quality and extent of interpersonal ties, and civic or community participation—has emerged as a key protective factor for psychological well-being [8]. Social connection differs from discrete helping acts (often termed prosocial behavior) [9]; instead, it captures how individuals are embedded in, and feel supported by, their social environments [10]. Social acceptance enhances self-worth and self-esteem, which can elevate one’s sense of meaning in life [11].

Because social acceptance shapes self-worth and self-esteem, the relational and reputational benefits that come from being socially connected reinforce self-worth and, in turn, foster a stronger sense of meaning in life [12,13]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that quality of life (QoL) tends to be diminished in individuals with severe mental health conditions [14,15,16]. Social connection has been consistently identified as a protective determinant of health. Its structural (e.g., network size and participation), functional (e.g., emotional and instrumental support), and qualitative (e.g., relationship satisfaction) dimensions are linked to lower stress and depression as well as better physical health and QoL [17,18,19].

Although social connection is widely acknowledged as a community priority, most studies have focused on its general health benefits or the effects of received social support [20,21,22], leaving its specific pathways to mental health largely underexplored. However, while the significance of social connection is well established, the literature has been relatively underdeveloped in examining its direct and indirect pathways to mental health outcomes. Could active social networks and relationship serve as protective factors against mental health decline? Do they enhance resilience, mitigate symptoms of depression and anxiety, or contribute to overall psychological well-being? While mounting evidence suggests that the structure and quality of social relationships are not only consequential for individual well-being but are also critical determinants of population health, the underlying mechanisms and variations across different populations remain unclear.

Attempting to address these questions, this study aims to bridge the gap by examining the impact of social connection on mental health, highlighting whether engaging in sustained, meaningful human relationships promotes psychological well-being. The findings could have significant implications for mental health interventions, policy-making, and community-based strategies aimed at improving psychological health through fostering social cohesion. In a large-scale cross-sectional study comprising 229,099 observations, we examine the direct relationship between individual social connection and mental health. We also examine how social connection indirectly reduces severe mental disorder by improving QoL. In addition, we suggest that the full impact of social connection will be different by the size of residential community.

2.1 Social Connection and Mental Health

While the WHO (2001) defines mental health as the ability to cope with stress, work productively, and contribute to society, recent public health perspectives view it as a dynamic state of emotional and social well-being, enabling individuals to pursue goals, manage challenges, and engage in society within supportive environments [23,24,25]. Social support plays a protective role in mental health. Research shows that individuals with strong social networks are less likely to experience depression or anxiety, even in the face of significant stress. Studies have demonstrated that social support can act as a buffer against the effects of stress, promoting resilience and recovery from mental health conditions [26]. Strong social networks lower stress biomarkers [27], while isolation increases the risk of mental distress [28]. There is a well-established theoretical link between social connection and mental health. The relationship can be explained by several psychological and sociological theories, highlighting mechanisms through which social connection contributes to enhanced well-being and mental health outcomes.

First, grounded in Self-Determination Theory (SDT), we argue that social connection enhances public health by satisfying fundamental psychological needs. SDT posits that relatedness, autonomy, and competence are essential for optimal functioning and well-being [29]. Cohesive networks and civic participation fulfill relatedness, while supportive social environments enable autonomous health choices and foster competence through informational and instrumental aid [30,31]. Need satisfaction, in turn, strengthens intrinsic motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviors, reduces psychological distress, and improves adherence to care, thereby yielding benefits at both individual and population levels.

Second, social exchange theory emphasizes that rewards such as expressions of gratitude and acts of reciprocity reinforce individual’s sense of self-worth and help reduce anxiety and depression [32]. The expectation that social cohesion may be reciprocated can foster a sense of security, knowing that one can count on others in times of need. Repeated fair exchanges cultivate trust and commitment, strengthening norms of reciprocity that ensure support is available when health needs arise [33]. These dynamics reduce the psychological and resource “costs” of seeking care, enhance compliance with preventive behaviors, and facilitate the rapid diffusion of credible health information [26,34]. At the community level, dense, reciprocally bonded networks bolster collective efficacy—coordinating mutual aid and advocacy for health-promoting environments—thereby translating individual exchanges into population health gains [34,35,36].

Third, based on social capital theory, social capital refers to the resources embedded in social relationships and community structures that individuals and groups can access and mobilize. Structural elements (e.g., civic participation, network size) and cognitive facets (e.g., trust, reciprocity) jointly enable the exchange of emotional and instrumental support, the diffusion of health-promoting information, and coordinated collective action [19]. These processes reduce stress exposure, improve health behaviors, and enhance access to services, thereby translating social connection into measurable gains in mental and physical health at the population level [36,37,38]. Taken as a whole, then, we suggest the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals with higher levels of social connection tend to experience better mental health.

2.2 The Mediating Effect of Quality of Life

However, it is important to systematically investigate how social connection reduces individuals’ mental health problems. In public health research, this requires clarifying not only the direct effects of social connection on mental health but also the mediating role of health-related QoL—that is, the degree of satisfaction people perceive in key life domains. Multiple theoretical perspectives support a linkage between social connection and QoL: connected individuals tend to report higher life satisfaction, stronger psychological well-being, and greater perceived support, all of which elevate QoL [26,39]. Consequently, QoL serves as a plausible pathway through which social connection translates into lower stress and depressive symptoms.

Broaden-and-build theory posits that positive emotions evoked by feeling socially connected—such as happiness, gratitude, or pride—broaden thought-action repertoires and help individuals accumulate enduring personal resources (e.g., resilient coping, supportive ties) [40]. These resources, in turn, strengthen life satisfaction and health-related QoL. Complementing this view, social capital theory emphasizes that dense, trusting networks supply emotional and instrumental support, lowering stress and enhancing life satisfaction [41]. Likewise, human flourishing perspectives suggest that meaningful engagement with others deepens purpose and contributes to both individual and collective well-being [42]. Taken together, these frameworks suggest that social connection improves QoL by strengthening social resources, enhancing life purpose, fulfilling psychological needs, and promoting both mental and physical health.

The relationship between QoL and mental health can be understood through various theoretical frameworks that suggest how life satisfaction, autonomy, social connectedness, and other dimensions of QoL impact mental health. Social support theory posits that strong relationships provide emotional support, which can buffer against stress [43]. Low QoL often correlates with limited social resources, making it harder for individuals to cope with life’s challenges and increasing their vulnerability to mental disorders. Humanistic perspectives [44,45] emphasize that a strong sense of self-worth is crucial for psychological well-being; low QoL can erode self-esteem and increase mental health risks. When QoL is low, individuals may feel they lack value or purpose, undermining their self-esteem and sense of identity, which can lead to mental health issues. In sum, these theories illustrate that low QoL can negatively impact mental health by constraining social connection, autonomy, meaning, and stress resilience. Addressing these QoL factors is therefore critical to reducing disorder risk and fostering mental recovery and resilience.

Given the theoretical discussion so far, this study suggests that social connection positively affects individuals’ mental health through improved QoL. Therefore, we hypothesize the indirect effect of social connection on mental health as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Individuals with stronger social connection tend to experience better mental health through enhanced quality of life.

2.3 Regional Impact on Social Connection and Mental Health

Despite the broad theoretical premises that expect the potential indirect relationship between social connection and mental health, little is known about its difference by region. Evidence indicates that the strength and consequences of social ties differ between rural and urban areas. In many rural communities—where formal mental-health services are scarce—tightly knit networks and everyday reciprocity serve as primary sources of emotional and practical support [46]. While social connection still contributes to well-being in urban settings, its impact on QoL may be less pronounced because urban residents have access to a wider range of supportive resources, including recreational activities, mental health services, and diverse social opportunities [47]. In contrast, rural residents may depend more on interpersonal relationships and social interactions as key sources of emotional support, which in turn may strengthen the pathway from social connection to QoL, and ultimately to mental health [48]. The resulting sense of belonging and mutual reliance in these settings may therefore translate into greater psychological well-being than in urban locales. Therefore, our third hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3: The indirect impact of social connection on mental health, mediated by quality of life, is stronger in rural regions than in urban regions.

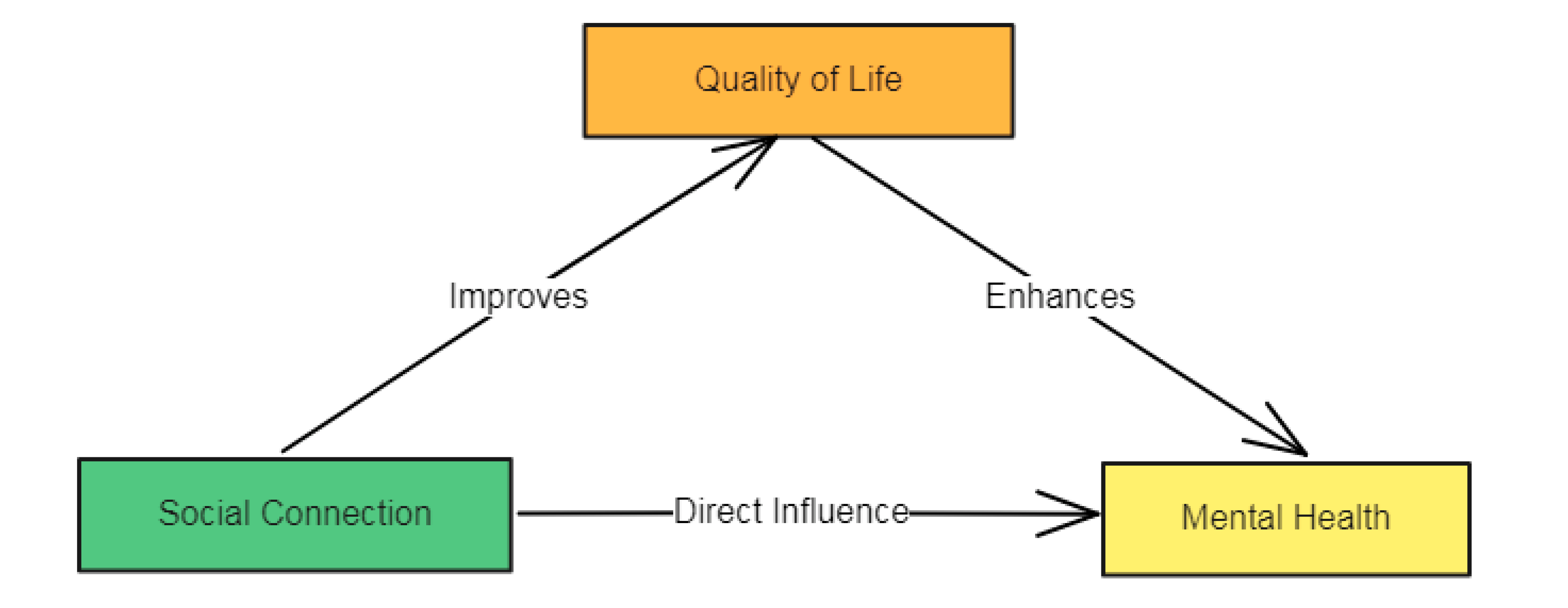

Taken as a whole, social connection promotes mental health by strengthening supportive ties, satisfying basic psychological needs, and enhancing QoL. Yet the magnitude of these benefits appears to vary across settings, highlighting the importance of context-sensitive approaches in mental health interventions and policies. This study aims to bridge the gap in existing research by examining the direct impact of social connection on mental health, specifically assessing whether being socially connected enhances psychological well-being and overall wellness. Additionally, we examine how social connection indirectly alleviates severe mental health conditions by enhancing QoL. By clarifying how connection operates in diverse residential contexts, our findings can inform targeted strategies to improve psychological well-being at the population level. Fig. 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework.

The data adopted for this study are from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA)’s Community Health Survey (CHS) conducted in 2019 [49]. Since its initial implementation in 2008, CHS has been a key source for designing and supporting public health policies on local health behaviors, mental health, and community-level healthcare utilization. Numerous studies have shaped evidence-based public health strategies and addressed regional health disparities using CHS data [50,51,52]. Building upon previous research efforts, this study examines a tripartite relationship among social connection, individuals’ health-related QoL, and mental health.

This study employed a cross-sectional design using the raw 2019 CHS dataset, which was selected because it includes all relevant variables required for our analysis—indicators of social participation (as a proxy for social value), EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) dimensions, subjective stress levels, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) items. While the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to draw causal inferences, the 2019 wave provides the most contextually appropriate dataset for our study focus. The original dataset consists of 280 variables and 229,099 observations, from which 203,657 were retained after data cleaning and manipulation for formal statistical assessment. We consider two response variables—subjective stress level and PHQ-9 score—to measure mental health. We applied reverse coding to the values of subjective stress level to ensure consistency. Meanwhile, following previous studies, the PHQ-9 score was calculated using nine variables (the nine diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder) from the CHS data [52,53].

To measure social connection, we developed a composite indicator of social participation using principal component analysis (PCA) based on three dimensions of social engagement: participation in friendship-based clubs, involvement in cultural or leisure activities, and engagement in voluntary work. The WHO Commission on Social Connection’s flagship report, From Loneliness to Social Connection (2025), identifies participation in hobbies, sports and other clubs, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and religious organizations as key population-level indicators reflecting the structural (activities and social partners), functional (exchanged resources), and qualitative (perceived closeness) aspects of social connection [54]. These indicators are considered alongside the frequency of contact with friends and family.

To examine how social connection influences individual mental health through health-related QoL, we initially considered the five EQ-5D domains (i.e., mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) with Korean-specific weights assigned [55]. However, since our dependent measures are subjective stress level and PHQ-9, incorporating the anxiety/depression domain of EQ-5D would create conceptual overlap between the mediator and the outcome variables. To avoid such confounding, we did not analyze the composite EQ-5D index; instead, we employ each of the four non-mental health domains as separate mediators.

Furthermore, we classified areas (i.e., urban vs. rural) based on Korea’s official administrative divisions. Individuals who reported residing in either eup (towns) or myeon (townships) were coded as living in rural areas, whereas those residing in dong (neighborhoods) were classified as living in urban areas [52,56]. This classification reflects the official administrative structure of South Korea, where eup/myeon generally correspond to rural jurisdictions with population below 50,000, while dong units are subdivisions of cities and larger towns (urban jurisdictions) [57,58]. Based on these understandings, we present Table 1, which explains the variables of our research interest and provides a summary of statistics for subsequent analyses.

Table 1: Summary of variables used in this study (A total of 203,567 observations).

| Variable | Description | Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response variables (Mental health) | |||||

| Stress1) | Reported subjective stress level | 1 | 4 | 1.996 | 0.742 |

| PHQ-92) | PHQ-9 score index for measuring severity of depressive symptoms | 0 | 27 | 2.095 | 3.078 |

| Independent variables (Social connection) | |||||

| Social participation3) | A principal component constructed from three variables related to social activities | −0.989 | 2.756 | 0 | 1 |

| Mediator (Health-related quality of life) | |||||

| Mobility4) | Ability to walk about | 1 | 3 | 2.822 | 0.396 |

| Self-care4) | Ability to wash or dress oneself | 1 | 3 | 2.934 | 0.271 |

| Usual activities4) | Ability to perform everyday activities | 1 | 3 | 2.868 | 0.363 |

| Pain/discomfort4) | Presence and intensity of pain or physical discomfort | 1 | 3 | 2.638 | 0.543 |

| Indicator (Population size) | |||||

| Urban5) | A binary variable (urban, 1; otherwise, 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.550 | 0.497 |

This study adopts a mediation analysis under a linear regression framework [59]. It examines whether and how the effect of predictors (social connection) on the dependent variable (stress level or PHQ-9 score) is transmitted through each mediator. The influence of independent variables on the dependent variable is decomposed into direct and indirect effects in a mediation analysis.

Let us define our independent variable as

All statistical analyses were conducted using jamovi (version 2.5.6) [60]. Mediation analyses were employed to test whether the association between social connection—operationalized as a composite social participation score derived through PCA—and mental health outcomes (subjective stress level and PHQ-9 score) was mediated by four health-related QoL domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, and pain/discomfort). Separate mediation models were estimated for urban, rural, and total samples using the medmod module under a linear regression framework.

Bootstrapped confidence intervals (5000 iterations) were generated to assess the statistical significance of indirect effects. All models adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, and employment status. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Results are reported as direct, indirect, and total effects, along with corresponding mediation percentages, for each outcome and regional group.

As previously noted, this study relies on the 2019 CHS data to explore how social connection affects mental health and whether health-related QoL mediates this relationship. It also examines whether these influences differ across regions, particularly between urban and rural areas. To address these research questions, we designed our dataset to conduct a series of mediation analyses. In that regard, we developed regression models that includes social connection as the key independent variable and two outcome variables: subjective stress levels and the PHQ-9 score, using data from all study participants (n = 203,567). Each non-mental health dimension of the EQ-5D (i.e., the QoL variables: mobility, self-care, usual activities, and pain/discomfort) was included as a mediator in these models. In addition, the same analytical framework was applied to urban and rural subsamples to assess regional disparities in the pathways linking social participation to mental health outcomes.

4.1 Results Based on Entire Datasets

We utilized the open-source software jamovi for mediation analyses [60]. Table 2 presents the mediation estimates for the effects of social connection on subjective stress levels, mediated by QoL for all observations. The total effect of social participation on subjective stress was statistically significant and negative (Estimate = −0.052, Z = −31.07, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of social participation are associated with lower levels of perceived stress. It is worth noting that these results were obtained after accounting for demographic covariates (i.e., age, gender, education levels, marital status, and employment), the effects of which are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Among the four mediators, both usual activities (Estimate = −0.010, Z = −36.89, p < 0.001, 19.2% of the total effect) and pain/discomfort (Estimate = −0.010, Z = −31.31, p < 0.001, 19.2%) exhibited the most substantial indirect effects. This suggests that both functional ability in daily activities and improved physical comfort play important roles in medicating the relationship between social participation and reduced stress. The other QoL dimensions, mobility (17.3%) and self-care (11.5%) also yielded statistically significant but relatively small indirect effects (Estimates ranging from −0.009 to −0.006, all p < 0.001). Across all models, the direct effect of social participation remained robust (p < 0.001), highlighting that the association with reduced stress is only partially mediated through improvements in QoL.

Table 2: Mediation estimates of social participation on subjective stress levels.

| Dependent Variable: Subjective Stress Levels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Connection | Mediator | Effect | Estimate | SE | Z | p | % Mediation |

| Social participation | Mobility | Indirect | −0.009 | 0.000 | −35.10 | <0.001 | 17.3 |

| Direct | −0.043 | 0.002 | −25.65 | <0.001 | 82.7 | ||

| Total | −0.052 | 0.002 | −31.07 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Self-care | Indirect | −0.006 | 0.000 | −29.02 | <0.001 | 11.5 | |

| Direct | −0.046 | 0.002 | −27.36 | <0.001 | 88.5 | ||

| Total | −0.052 | 0.002 | −31.50 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Usual activities | Indirect | −0.010 | 0.000 | −36.89 | <0.001 | 19.2 | |

| Direct | −0.042 | 0.002 | −25.09 | <0.001 | 80.8 | ||

| Total | −0.052 | 0.002 | −31.07 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Pain/Discomfort | Indirect | −0.010 | 0.000 | −31.31 | <0.001 | 19.2 | |

| Direct | −0.042 | 0.002 | −25.09 | <0.001 | 80.8 | ||

| Total | −0.052 | 0.002 | −31.07 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

From another perspective, Table 3 shows the path estimates of the mediation models, offering insight into the strength and direction of the individual pathways between social participation, non-mental health dimensions of EQ-5D, and subjective stress. All a paths (social participation → mediator; Table 3, Label a) were positive and significant, indicating that higher social participation is associated with better QoL. The b paths (mediator → stress; Table 3, Label b) were negative and significant for pain/discomfort, self-care, and usual activities, supporting their roles as mediators. Across all models, the direct effects (c paths) remained significantly negative, implying that the relationship is only partially mediated by improvements in QoL.

Table 3: Path estimates of social participation on subjective stress levels.

| Dependent Variable: Subjective Stress Levels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Label | Estimate | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Z | p | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Social participation → Mobility | a | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 49.16 | <0.001 |

| Mobility → Stress | b | −0.235 | 0.005 | −0.245 | −0.226 | −50.13 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Stress | c | −0.043 | 0.002 | −0.046 | −0.040 | −25.65 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Self-care | a | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 39.85 | <0.001 |

| Self-care → Stress | b | −0.264 | 0.006 | −0.277 | −0.252 | −42.33 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Stress | c | −0.046 | 0.002 | −0.049 | −0.043 | −27.36 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Usual activities | a | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 50.26 | <0.001 |

| Usual activities → Stress | b | −0.265 | 0.005 | −0.275 | −0.256 | −54.31 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Stress | c | −0.042 | 0.002 | −0.045 | −0.049 | −25.09 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Pain/discomfort | a | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.041 | 33.77 | <0.001 |

| Pain/discomfort → Stress | b | −0.264 | 0.003 | −0.270 | −0.258 | −83.03 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Stress | c | −0.042 | 0.002 | −0.046 | −0.038 | −25.09 | <0.001 |

Table 4 and Table 5 present the mediation and path estimates of social connection on depressive symptoms, as measured by the PHQ-9 index, through the QoLs. Similar to the findings for subjective stress levels (Table 2 and Table 3), the social participation variable was significantly associated with reduced depressive symptoms (total effect: Estimate = –0.308, p < 0.001), both directly and indirectly through all four QoL dimensions. It is worth noting that these results were obtained after accounting for demographic covariates (i.e., age, gender, education levels, marital status, and employment), the effects of which are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 4: Mediation estimates of social participation on depression.

| Dependent Variable: PHQ-9 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Connection | Mediator | Effect | Estimate | SE | Z | p | % Mediation |

| Social participation | Mobility | Indirect | −0.075 | 0.002 | −44.20 | <0.001 | 24.4 |

| Direct | −0.233 | 0.007 | −34.06 | <0.001 | 75.6 | ||

| Total | −0.308 | 0.007 | −44.19 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Self-care | Indirect | −0.053 | 0.001 | −36.31 | <0.001 | 17.1 | |

| Direct | −0.255 | 0.007 | −37.10 | <0.001 | 82.9 | ||

| Total | −0.308 | 0.007 | −44.19 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Usual activities | Indirect | −0.085 | 0.002 | −45.86 | <0.001 | 27.6 | |

| Direct | −0.224 | 0.007 | −32.84 | <0.001 | 72.4 | ||

| Total | −0.308 | 0.007 | −44.19 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

| Pain/Discomfort | Indirect | −0.069 | 0.002 | −32.80 | <0.001 | 22.4 | |

| Direct | −0.240 | 0.007 | −35.80 | <0.001 | 77.6 | ||

| Total | −0.308 | 0.007 | −44.19 | <0.001 | 100 | ||

Path analysis revealed that social connection was positively associated with each QoL domain (a paths = 0.024 to 0.039, p < 0.001), which in turn were strongly linked to lower PHQ-9 scores (b paths = –2.232 to –1.774, p < 0.001). The strongest mediated effects were observed through usual activities (27.6%) and mobility (24.4%), followed by pain/discomfort (22.4%) and self-care (17.1%). Despite significant mediation, the direct effect of social participation remained robust across models (c paths = –0.255 to –0.224), indicating that social connection reduces depressive symptoms both directly and through improvements in physical functioning.

Table 5: Path estimates of social participation on depression.

| Dependent Variable: PHQ-9 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Label | Estimate | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | Z | p | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Social participation → Mobility | a | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 49.16 | <0.001 |

| Mobility → Phq-9 | b | −1.945 | 0.019 | −1.982 | −1.907 | −101.23 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Phq-9 | c | −0.233 | 0.007 | −0.247 | −0.220 | −34.06 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Self-care | a | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 39.85 | <0.001 |

| Self-care → Phq-9 | b | −2.262 | 0.026 | −2.312 | −2.211 | −88.11 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Phq-9 | c | −0.255 | 0.007 | −0.269 | −0.242 | −37.10 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Usual activities | a | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 50.26 | <0.001 |

| Usual activities → Phq-9 | b | −2.232 | 0.020 | −2.271 | −2.193 | −112.15 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Phq-9 | c | −0.224 | 0.007 | −0.237 | −0.210 | −32.84 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Pain/discomfort | a | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.041 | 33.77 | <0.001 |

| Pain/discomfort → Phq-9 | b | −1.774 | 0.013 | −1.799 | −1.749 | −137.70 | <0.001 |

| Social participation → Phq-9 | c | −0.240 | 0.007 | −0.253 | −0.226 | −35.80 | <0.001 |

4.2 Urban and Rural Comparisons Using Subsets

To examine whether the mediating effects vary across regions, we split the entire dataset (n = 203,567) into urban (n1 = 112,111) and rural (n2 = 91,546) subsamples with urban respondents accounting for 55.1% of total observations. Table 6 presents the mediation estimates stratified by region. Regarding subjective stress levels (upper panel), the indirect effects of social participation on stress were consistently negative across QoL domains, indicating stress-reducing mediation pathways.

The magnitude of mediation also differed substantially by regions. In urban areas, indirect effects accounted for 8–16% of the total effects—mobility (12.9%), self-care (8.1%), usual activities (12.7%), and pain/discomfort (16.1%)—indicating that the relationship between social participation and stress is primarily direct with modest mediation. Conversely, in rural areas, mediation was more pronounced, accounting for 17–27% of the total effect (mobility: 24.4%, self-care: 17.1%, usual activities: 26.8%, pain/discomfort: 22.0%). These results suggest that improvements in physical functioning play a more central role in the stress-buffering effects of social engagement in rural contexts. Importantly, these estimates were obtained after adjusting for demographic covariates (i.e., age, gender, education levels, marital status, and employment), the effects of which are detailed in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 for subjective stress levels and in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 for depressive symptoms (PHQ-9).

Table 6: Comparison of mediation estimates between urban and rural areas.

| Dependent Variables: Subjective Stress Levels and PHQ-9 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator & Effect | Urban | Rural | Entire Regions | ||||

| Estimate | % Mediation | Estimate | % Mediation | Estimate | % Mediation | ||

| Subjective stress levels | |||||||

| Mobility | Indirect | −0.008** | 12.9 | −0.010*** | 24.4 | −0.009*** | 17.3 |

| Direct | −0.054*** | 87.1 | −0.031*** | 75.6 | −0.043*** | 82.7 | |

| Total | −0.062*** | 100 | −0.041*** | 100 | −0.052*** | 100 | |

| Self-care | Indirect | −0.005*** | 8.1 | −0.007*** | 17.1 | −0.006*** | 11.5 |

| Direct | −0.057*** | 91.9 | −0.034*** | 82.9 | −0.046*** | 88.5 | |

| Total | −0.062*** | 100 | −0.041*** | 100 | −0.052*** | 100 | |

| Usual activities | Indirect | −0.009*** | 12.7 | −0.011*** | 26.8 | −0.010*** | 19.2 |

| Direct | −0.053*** | 87.3 | −0.030* | 73.2 | −0.042*** | 80.8 | |

| Total | −0.062*** | 100 | −0.041*** | 100 | −0.052*** | 100 | |

| Pain/Discomfort | Indirect | −0.010*** | 16.1 | −0.009*** | 22 | −0.010*** | 19.2 |

| Direct | −0.052*** | 83.9 | −0.032*** | 78 | −0.042*** | 80.8 | |

| Total | −0.062*** | 100 | −0.041*** | 100 | −0.052*** | 100 | |

| PHQ-9 | |||||||

| Mobility | Indirect | −0.070*** | 20.1 | −0.076*** | 29.1 | −0.075*** | 24.4 |

| Direct | −0.277*** | 79.9 | −0.185*** | 70.9 | −0.233*** | 75.6 | |

| Total | −0.348*** | 100 | −0.261*** | 100 | −0.308*** | 100 | |

| Self-care | Indirect | −0.052*** | 14.9 | −0.053*** | 20.3 | −0.053*** | 17.1 |

| Direct | −0.295*** | 85.1 | −0.208*** | 79.7 | −0.255*** | 82.9 | |

| Total | −0.348*** | 100 | −0.261*** | 100 | −0.308*** | 100 | |

| Usual activities | Indirect | −0.080*** | 23 | −0.085*** | 32.6 | −0.085*** | 27.6 |

| Direct | −0.267*** | 77 | −0.175*** | 67.4 | −0.224*** | 72.4 | |

| Total | −0.348*** | 100 | −0.261*** | 100 | −0.308*** | 100 | |

| Pain/Discomfort | Indirect | −0.073*** | 21 | −0.061*** | 23.4 | −0.069*** | 22.4 |

| Direct | −0.275*** | 79 | −0.200*** | 76.6 | −0.240*** | 77.6 | |

| Total | −0.348*** | 100 | −0.261*** | 100 | −0.308*** | 100 | |

For depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), a similar pattern was observed (lower panel of Table 6). While the total effects of social participation were consistent across urban (–0.348), rural (–0.261), and overall (–0.308) samples, the extent of mediation again varied by region. In rural areas, indirect effects were relatively higher—mobility (29.1%), usual activities (32.6%), and pain/discomfort (23.4%)—compared to urban areas, where the corresponding mediated proportions were 20.1%, 23.0%, and 21.0%, respectively. Although self-care was the least influential mediator in both regions, it still accounted for 20.3% of the effect in rural areas as compared to 14. 9% in urban areas.

Across all models and regions, the direct effects of social participation remained significant, accounting for approximately 73–92% of the total effects for subjective stress and 67–85% for depressive symptoms. This confirms that social participation contributes to reduced stress and depressive symptoms through both direct and indirect pathways. These results suggest that while QoL mediators are important in all settings, their influence is more pronounced in rural areas, where physical functioning appears to contribute more substantially to the mental health benefits of social engagement.

Importantly, indirect effects through QoL were significant in both urban and rural areas, suggesting that social engagement enhances QoL, which in turn mitigates stress and depressive symptoms. However, the urban–rural gap in mediation was narrower for depression than for subjective stress, indicating a more consistent mediation structure for depression across regions. These findings imply that the mental health benefits of social connection are context-dependent, with regional variation likely shaped by environmental, social, and infrastructural conditions.

Our study provides empirical evidence supporting all three proposed hypotheses. First (Hypothesis 1), we find that higher levels of social connection are significantly associated with better mental health outcomes, including lower stress and reduced depressive symptoms. Second (Hypothesis 2), the results demonstrate that this relationship is partially mediated by QoL, with substantial indirect effects observed across multiple QoL domains, suggesting that social connection improves mental health indirectly through enhanced QoL. Third (Hypothesis 3), the analyses reveal that the indirect impact through QoL is more pronounced in rural than in urban areas. Taken together, these findings align with existing literature while extending it by showing robust evidence that social connection contributes to mental well-being both directly and indirectly, with the magnitude of these effects differing by regional context.

The findings indicate that social connection directly reduce stress and depressive symptoms. These results align with previous research emphasizing social connectedness in fostering emotional resilience and mitigating mental distress [26,27,28]. The significant direct effect of social participation as a measure of social connection suggests that individuals who actively participate in cohesive networks and civic participation are more likely to experience lower stress and depression. This finding is particularly relevant given the growing recognition of social connection including structural (what you do and with whom), functional (resources exchanged), and cognitive (perceived closeness) aspects as a fundamental element of psychological well-being [37]. Similarly, social networks and participation were found to be a strong predictor of lower stress and depressive symptoms. Individuals actively engaged in social activities and community-based initiatives benefit from belonging and emotional support, reinforcing the buffering effect of social capital on mental health. The direct impact of social connection on stress reduction stems from the emotional support and positive reinforcement afforded by interpersonal interactions, which function as supportive resources for managing everyday stressors.

A key contribution of this study is the identification of QoL as a crucial mediator in the relationship between social connection and mental health. Our findings reveal that individuals exhibiting higher social connection experience enhanced QoL, which, in turn, leads to better mental health outcomes. This suggests that positive emotions derived from social relationships help broaden an individual’s mindset, leading to the accumulation of personal and social resources that improve life satisfaction. Specifically, social participation exhibited the highest proportion of indirect effects through QoL, indicating that engaging in social relationships, roles, and interactions activities improve QoL, further benefiting mental well-being. This highlights the importance of social connection as a pathway to achieving overall well-being.

A key aspect of our study was examining how the relationship between social connection and mental health varies between urban and rural regions. Our findings indicate that the indirect impact of social connection through QoL is more pronounced in rural areas than in urban settings. Specifically, social participation showed a stronger mediation effect in rural communities, suggesting that social connection plays a crucial role in maintaining mental well-being where formal mental health services may be scarce. This result is consistent with previous research suggesting that rural residents rely more heavily on interpersonal relationships and community engagement as primary sources of emotional support [48]. The stronger indirect impact of social participation in rural areas can be explained by the close-knit nature of rural communities, where individuals tend to have deeper social connections and a heightened sense of collective responsibility for each other’s well-being. Additionally, the relative lack of recreational and mental health resources in rural regions may make social engagement a more significant factor in enhancing QoL and reducing mental distress. In contrast, in urban areas, the direct effects of social participation on mental health were found to be stronger compared to rural settings. This suggests that urban dwellers may benefit more from individual-level social roles and interpersonal connections, possibly due to the diverse and heterogeneous nature of urban communities. The relatively lower indirect effect of social connection through QoL in urban settings may be due to the availability of alternative resources, such as professional mental health services and diverse leisure activities, which contribute to QoL independent of social engagement.

Given the significant role of social connection in improving mental health, our findings have important policy implications. Efforts to promote community-based social engagement programs should be prioritized, particularly in rural areas where formal mental health services are limited. Public health initiatives that encourage volunteering, civic participation, and neighborhood-based support networks could serve as cost-effective interventions to enhance QoL and reduce the burden of mental illness. Additionally, policymakers should consider integrating social connection interventions into mental health programs. For instance, cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques could incorporate elements of social engagement to reinforce positive social interactions and enhance self-worth among individuals experiencing mental distress. Furthermore, initiatives aimed at strengthening social inclusion and cohesion within communities—such as participatory governance, community dialogues, and inclusive urban planning—can help create environments that foster mental well-being.

Despite the significant findings regarding both the direct and indirect impacts of social connection on mental health, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the data were derived from Korean survey respondents in 2019, and the findings are therefore context-specific and should be generalized with caution. Nevertheless, because the mechanisms linking prosocial behavior and mental health are supported by broader psychological and public health theory, the findings may hold implications beyond the Korean case. Second, given the cross-sectional and observational design, causal inferences cannot be established between the associations identified. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs across diverse contexts would help validate and extend these findings.

In conclusion, this study provides robust evidence that social connection has both direct and indirect effects on mental health, with health-related QoL serving as a critical mediator in this relationship. Importantly, these findings were observed after adjusting for key demographic covariates, thereby enhancing the robustness of the results. The study underscores the importance of fostering social connection as strategies for promoting psychological well-being. Moreover, the differences observed between urban and rural areas highlight the need for context-specific interventions that leverage the strengths of local social structures. Nonetheless, the cross-sectional study design limits our ability to infer causality, and future research should further employ longitudinal or experimental approaches to clarify the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, investigating other contextual factors, such as cultural influences and economic conditions, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how social connection contributes to psychological well-being.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Seoul RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2025-RISE-01-005-07).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Jimin Chae, Geiguen Shin; data collection: Jimin Chae, Youngbin Lym; analysis and interpretation of results: Youngbin Lym, Geiguen Shin; draft manuscript preparation: Jimin Chae, Youngbin Lym, Geiguen Shin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: The data used in this study are publicly available; therefore, ethical approval or individual consent is not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071482/s1. Table S1: Covariate effects on Subjective stress levels. Table S2: Covariate effects on PHQ-9. Table S3: Covariate effects on Subjective stress levels (Urban). Table S4: Covariate effects on Subjective stress levels (Rural). Table S5: Covariate effects on PHQ-9 (Urban). Table S6: Covariate effects on PHQ-9 (Rural).

References

1. Lund C , De Silva M , Plagerson S , Cooper S , Chisholm D , Das J , et al. Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011; 378( 9801): 1502– 14. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60754-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Crockett MA , Núñez D , Martínez P , Borghero F , Campos S , Langer AI , et al. Interventions to reduce mental health stigma in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2025; 8( 1): e2454730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nwokoroku SC , Neil B , Dlamini C , Osuchukwu VC . A systematic review of the role of culture in the mental health service utilization among ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom. Glob Ment Health. 2022; 9: 84– 93. doi:10.1017/gmh.2022.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ran MS , Hall BJ , Su TT , Prawira B , Breth-Petersen M , Li XH , et al. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21( 1): 8. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02991-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu Q , Li C , Zhang L , Zhou Y . The mitigation effects of residential green space and low air pollution on socioeconomic inequalities in depression. npj Ment Health Res. 2025; 4( 1): 33. doi:10.1038/s44184-025-00152-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ochnik D , Buława B , Nagel P , Gachowski M , Budziński M . Urbanization, loneliness and mental health model—a cross-sectional network analysis with a representative sample. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 24974. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-76813-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Srivastava K . Urbanization and mental health. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009; 18( 2): 75– 6. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.64028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Holt-Lunstad J , Robles T , Sbarra DA . Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol. 2017; 72( 6): 517– 30. doi:10.1037/amp0000103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Klein N . Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. J Posit Psychol. 2017; 12( 4): 354– 61. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1209541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Holt-Lunstad J . Social connection as a public health issue: the evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022; 43: 193– 213. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Anthony DB , Holmes JG , Wood JV . Social acceptance and self-esteem: tuning the sociometer to interpersonal value. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007; 92( 6): 1024– 39. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sarac E , Yıldız E . Future anxiety and belongingness in young and older adults: an empirical study. World J Psychiatry. 2025; 15( 6): 106227. doi:10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Leary MR , Tambor ES , Terdal SK , Downs DL . Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995; 68( 3): 518– 30. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Berghöfer A , Martin L , Hense S , Weinmann S , Roll S . Quality of life in patients with severe mental illness: a cross-sectional survey in an integrated outpatient health care model. Qual Life Res. 2020; 29: 2073– 87. doi:10.1007/s11136-020-02470-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rapaport MH , Clary C , Fayyad R , Endicott J . Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162( 6): 1171– 8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Saarni SI , Suvisaari J , Sintonen H , Pirkola S , Koskinen S , Aromaa A , et al. Impact of psychiatric disorders on health-related quality of life: general population survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2007; 190: 326– 32. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Berkman LF , Glass T , Brissette I , Seeman TE . From social integration to health: durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51( 6): 843– 57. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Holt-Lunstad J . Social connection as a critical factor for mental and physical health: evidence, trends, challenges, and future implications. World Psychiatry. 2024; 23( 3): 312– 32. doi:10.1002/wps.21224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kawachi I , Berkman LF . Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In: Berkman LF , Kawachi I , Glymour MM , editors. Social epidemiology. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014. p. 290– 319. doi:10.1093/med/9780195377903.003.0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Clark JL , Algoe SB , Green MC . Social network sites and well-being: the role of social connection. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2017; 27( 1): 32– 7. doi:10.1177/0963721417730833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Seppala E , Rossomando T , Doty JR . Social connection and compassion: important predictors of health and well-being. Soc Res. 2013; 80( 2): 411– 30. doi:10.1353/sor.2013.0027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Umberson D , Montez JK . Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010; 51( Suppl): S54– S66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. World Health Organization (WHO) . Mental health: strengthening mental health promotion. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

24. Galderisi S , Heinz A , Kastrup M , Beezhold J , Sartorius N . Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry. 2015; 14( 2): 231– 3. doi:10.1002/wps.20231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wren-Lewis S , Alexandrova A . Mental health without well-being. J Med Philos. 2021; 46( 6): 684– 703. doi:10.1093/jmp/jhab032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lam PH . An extension to the stress-buffering model: timing of support across the lifecourse. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2024; 42: 100876. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ozbay F , Johnson DC , Dimoulas E , Morgan CA , Charney D , Southwick S . Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry. 2007; 4( 5): 35. [Google Scholar]

28. Cacioppo JT , Hughes ME , Waite LJ , Hawkley LC , Thisted RA . Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006; 21( 1): 140– 51. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Deci EL , Ryan RM . The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000; 11( 4): 227– 68. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ng JY , Ntoumanis N , Thøgersen-Ntoumani C , Deci EL , Ryan RM , Duda JL , et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012; 7( 4): 325– 40. doi:10.1177/1745691612447309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ryan RM , Patrick H , Deci EL , Williams GC . Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: interventions based on self-determination theory. Eur Health Psychol. 2008; 10( 1): 2– 5. [Google Scholar]

32. Peng C , Nelissen R , Zeelenberg M . Reconsidering the roles of gratitude and indebtedness in social exchange. Cogn Emot. 2018; 32( 4): 760– 78. doi:10.1080/02699931.2017.1353484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Molm LD . The structure of reciprocity. Soc Psychol Q. 2010; 73( 2): 119– 31. doi:10.1177/0190272510369079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Thoits PA . Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011; 52( 2): 145– 61. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cropanzano R , Mitchell MS . Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag. 2005; 31( 6): 874– 900. doi:10.1177/0149206305279602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Szreter S , Woolcock M . Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2004; 33( 4): 650– 67. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Putnam RD . Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster; 2000. doi:10.1145/358916.361990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Morgan A , Svedberg P , Nyholm M , Nygren J . Advancing knowledge on social capital for young people’s mental health. Health Promot Int. 2021; 36( 2): 535– 47. doi:10.1093/heapro/daaa055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Uchino BN . Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006; 29( 4): 377– 87. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Fredrickson BL . The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001; 56( 3): 218– 26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Elgar FJ , Davis CG , Wohl MJ , Trites SJ , Zelenski JM , Martin MS . Social capital, health and life satisfaction in 50 countries. Health Place. 2011; 17( 5): 1044– 53. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hefferon K , Ashfield A , Waters L , Synard J . Understanding optimal human functioning—the ‘call for qual’ in exploring human flourishing and well-being. J Posit Psychol. 2017; 12( 3): 211– 9. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1225120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bekiros S , Jahanshahi H , Munoz-Pacheco JM . A new buffering theory of social support and psychological stress. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 10): e0275364. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Maslow A . The psychology of science. New York, NY, USA: Harper & Row; 1966. [Google Scholar]

45. Rogers CR . Client-centered therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. Boston, MA, USA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951. [Google Scholar]

46. Caldwell TM , Jorm AF , Dear KBG . Suicide and mental health in rural, remote, and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med J Aust. 2004; 181( 7): S10– 4. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06348.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ballas D . What makes a ‘happy city’? Cities. 2013; 32( 1): S39– 50. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Komiya A , Oishi S , Lee M . The rural–urban difference in interpersonal regret. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2016; 42( 4): 513– 25. doi:10.1177/0146167216636623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency . 2019 Community Health Survey: Raw Data [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 05]. Available from: https://chs.kdca.go.kr/chs/index.do. [Google Scholar]

50. Jang BN , Youn HM , Lee DW , Joo JH , Park EC . Association between community deprivation and practising health behaviours among South Korean adults: a survey-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11: e047244. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kim S , Kim KH . Physical, mental health, and social support of young adults under 30 living with dementia patients: analysis of the 2019 Community Health Survey. Korean J Fam Pract. 2024; 14: 57– 64. (In Korean). doi:10.21215/kjfp.2024.14.1.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Jung M , Kim J . Influence of social capital on depression of older adults living in rural area: a cross-sectional study using the 2019 Korea Community Health Survey. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2022; 52: 144– 56. (In Korean). doi:10.4040/jkan.21239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. An JY , Seo ER , Lim KH , Shin JH , Kim JB . Standardization of the Korean version of the patient health questionnaire-9 as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2013; 19: 47– 56. (In Korean). doi:10.0000/jksbtp.2013.19.1.47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. World Health Organization . From loneliness to social connection—charting a path to healthier societies: report of the WHO commission on social connection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2025. [Google Scholar]

55. Moon H , Cha S . Multilevel analysis of factors affecting health-related quality of life of the elderly. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2022; 31: 391– 401. (In Korean). doi:10.12934/jkpmhn.2022.31.3.391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Park S , Bai H , Lee JR , Kim S , Jung H , Lee JY . Necessity of analyzing the Korea community health survey using 7 local government types. J Prev Med Public Health. 2025; 58( 1): 83– 91. doi:10.3961/jpmph.24.388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Institute for Basic Science . Living in Korea—Overview of Metro Lines [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://centers.ibs.re.kr/html/living_en/overview/lines.html. [Google Scholar]

58. Korea Legislation Research Institute . Local Autonomy Act [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/ganadaDetail.do?hseq=57596&type=abc&key=LOCAL+AUTONOMY+ACT¶m=L. [Google Scholar]

59. Baron RM , Kenny DA . The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 51: 1173– 82. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. The Jamovi Project [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.jamovi.org. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools