Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring the Framework of Online Music Use for Motivation of Studies and Gratification Needs for Students’ Well-Being

1 Faculty of Creative Multimedia, Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, 63100, Malaysia

2 Centre for Interaction and Experience Design, CoE of Immersive Experience, Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, 63100, Malaysia

3 Learning Institute for Empowerment, Multimedia University, Melaka, 75450, Malaysia

4 Faculty of Education, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Bandar Puncak Alam, 42300, Malaysia

5 Faculty of Technology Management and Business, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Batu Pahat, 86400, Malaysia

6 School of Communication & Design, Saigon South Campus, RMIT University, Ho Chi Minh, 700000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Hawa Rahmat. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion in Higher Education: Interventions and Strategies for the Psychological Well-being of Teachers and Students)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 10 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073109

Received 11 September 2025; Accepted 08 December 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

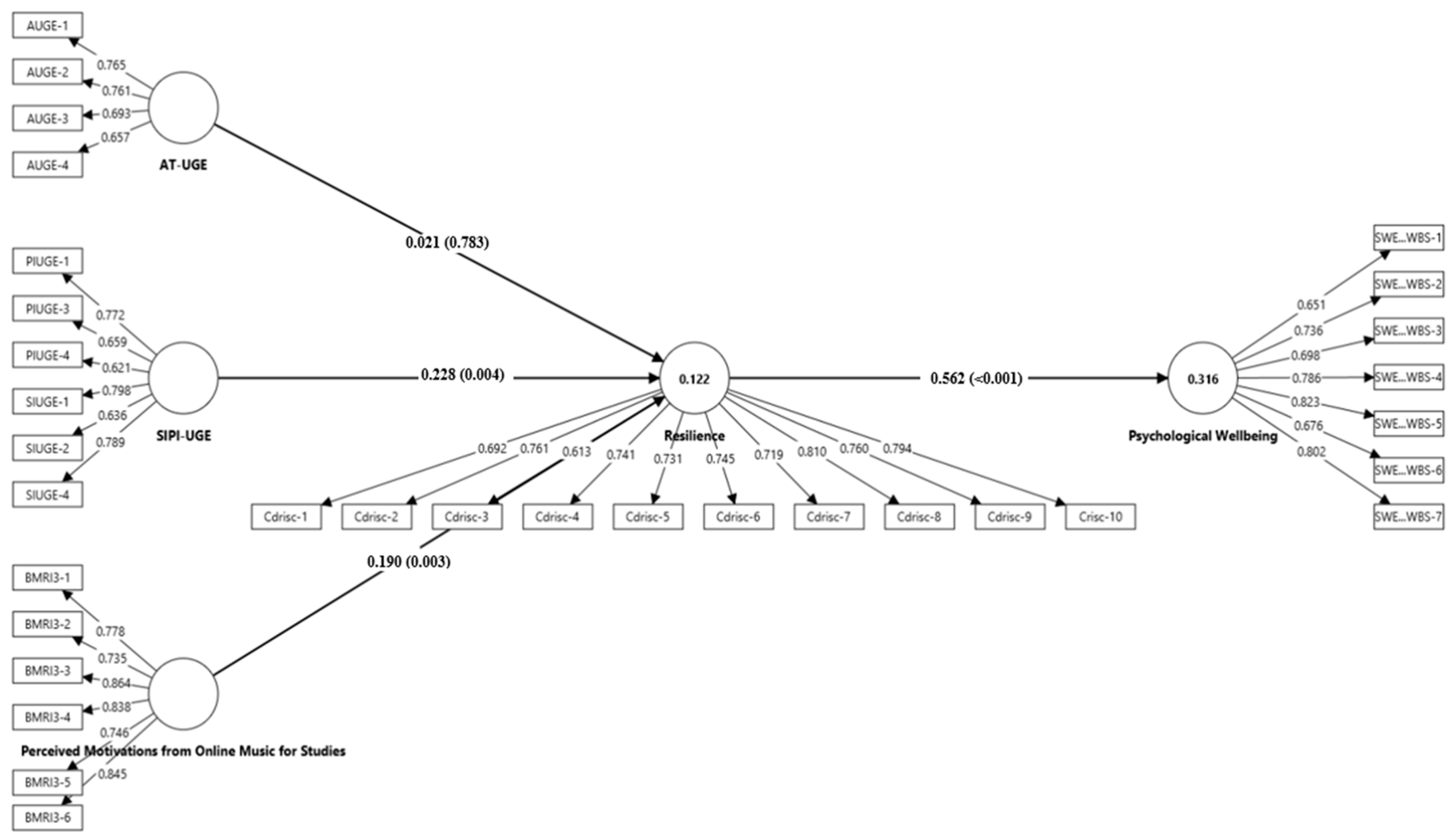

Background: Music has proven to be vital in enhancing resilience and promoting well-being. Previously, the impact of music in sports environments was solely investigated, while this paper applies it to study environments, standing out as pioneering research. The study consists of a systematic development of a conceptual framework based on theories of Uses and Gratification Expectancy (UGE) and perceived motivation based on music elements. Their components are observed variables influencing students’ psychological well-being (as the dependent variable). Resilience is examined as a mediator, influencing the relationships of both observed and dependent variables. The main purpose of this study is to highlight the positive effects of online music consumption on the psychological well-being of students. Methods: Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with eighteen final year creative multimedia undergraduate students belonging to five central region Malaysian universities, especially on their UGE needs, and a similar concept survey instrument with two hundred participants. The interview data were analysed through thematic analysis, while the survey data through descriptive and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Results: The results highlight that students gain motivation from online music, which positively affects their psychological well-being (β= 0.190, p= 0.003, f2 = 0.037), while resilience significantly affects this relationship (β = 0.562, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.461). However, the results also predict a partial relationship between constructs based on UGE with psychological well-being, mediated by resilience, i.e., AT-UGE (β = 0.021, p = 0.783, f2 = 0.000), SIPI-UGE (β = 0.228, p = 0.004, f2 = 0.044). Conclusion: The outcome of the study reflected practical, meaningful, and statistically significant results. The majority of the predictors, with the exception of one, i.e., AT-UGE, displayed a clear positive relation of online music consumption on the Psychological Well-being of students. Future research will explore varying contextual factors impacting online music-related gratifications, motivations, and resilience, along with additional potential mediators and moderators.Keywords

The incorporation of online music resources into education systems is in accordance with the idea or assumption that the integration of this technology will prove fruitful in enhancing the psychological well-being of students, which will have a positive effect on their academic performances. The study incorporates the Uses and Gratification Expectancy (UGE) framework to better explain the expectations students have, associated with the media, i.e., online music they consume, and how the fulfilment of these expectations contributes to their improved psychological well-being [1]. Additionally, conceptual support is drawn from the theory of perceived motivations from music based on Brunel’s Musing rating inventory to investigate how students utilise online music to gain motivation, which in turn leads to their improved psychological well-being [2].

Commonly, students find music consumption satisfying for their psychological and emotional needs [3]. Many students considered music as a more effective way to sustain their mood during challenges, compared to other activities, serving purposes beyond mere entertainment. Students active on social media frequently encounter music, either directly or indirectly. Even though some students purposely rely much more on online music than others, the students’ expectations regarding the uses and gratification of online music consumption might affect or influence their “perceived well-being” while studying. Listening to music may require intentional effort, which may divert students’ focus. Specifically, studies have emphasised the factors of association, musicality, cultural impact, rhythmic responses [2], and the importance of resilience in observing the outcomes. Therefore, the concern is about the quality of music and its components in relation to students’ motivational needs [4].

The first objective (RO1) of the following paper is to identify how the motivations obtained through online music consumption impact the psychological well-being of students. The second objective (RO2) is to investigate how the uses and gratification expectancy aspects of students, towards online music consumption, might influence their psychological well-being. The third objective (RO3) is to explore how resilience levels of students mediate the relationship between observed variables (based on UGE and perceived motivations from online music for studies) and outcome variable (psychological well-being).

RQ1: How do motivations obtained from online music impact the psychological well-being of final year undergraduate Malaysian students?

RQ2: How do uses and gratifications expectancies from online music impact the psychological well-being of final year undergraduate Malaysian students?

RQ3: How resilience levels of students mediate the relation between observed variables and the outcome variable?

Listening to music through online platforms has completely revolutionised how we interact, consume, and discover music. The advancements in digital technology have created an era of choice and accessibility, which has led to a transformation of the listening habits of billions of people worldwide. Artificial intelligence has also significantly contributed to this advancement by not only recommending curated musical playlists but also providing tools to create preferred music consisting of various genres, varying rhythms, moods, and instruments. This concept of self-preferred music consumption and generation through AI can promote well-being by lifting moods, uplifting spirits, and providing relaxation [5].

Zaatar et al. stated that music has proven to be effective in the completion of creative tasks and mood enhancement activities, which lead to motivation and improved focus. In addition to generally enhancing well-being, positive mood also greatly influences cognitive flexibility and focused attention [6]. Musicality and tempo have a profound impact on emotions. Tempos that are upbeat have the capacity to evoke feelings of excitement and energy, whereas slower tempos promote relaxation and calmness. Vibroacoustic therapy is a common practice nowadays that utilises music in providing relaxation, pain relief, and improved blood flow for those who are affected [7].

Faster tempos can potentially enhance the feeling of being energetic. Upbeat music can improve mood, leading to a more positive emotional state [8]. Slower tempos promote restfulness and relaxation. Calming music can create a sense of peacefulness, which reduces stress [2]. The motivational relation between tempo (rhythm) and desirable music may promote and facilitate a greater sense of liberty when they’re suitable for a specific motor rhythm [9]. Music can boost self-esteem and confidence if it resonates with an individual’s personal values and identity. An improvement in sports performance has been observed while listening to motivational synchronous music (movement in time with a pleasurable musical rhythm) because it facilitates entrainment by the rhythm that has potential [10]. Music that aligns with personal preferences and tastes can increase interest in life by providing emotional connection and enjoyment [10]. Musical experiences that are shared, such as sharing motivational music playlists with friends or listening to music with them, can strengthen social bonds [11]. Music can provide a temporary escape from anxiety and stress. Music can help detach, or turn off your mind, from feelings of stress or fatigue, regulate or lift your spirits, and adjust your arousal level. Soothing melodies and harmonies can induce a state of tranquility and restfulness.

2.3 Uses and Gratification Theory and Models

Littlejohn stated that the assumption, according to the Uses and Gratification theory, is that the audience actively seeks media in a goal-oriented manner. In this way, they gain gratification as needed [12]. Rayburn stated that the theory was reorganised to draw a comparison between the gratifications sought and obtained by the audience [13]. Mondi Makingu et al. further emphasised that the contrast between gratifications sought and obtained might have provided a favourable outcome in the past, but it is less likely that the same outcome will be reflected upon further engagement with media consumption [14].

2.4 Expectancy Value Theory and Its Addition to Existing Framework

Rayburn then proposed the addition of the theory of expectancy value within the uses and gratification theory framework. According to the updated model, the audience consumes media with an expectation of seeking personal gratification, assuming that the consumed media will fulfill them (GS). If they are fulfilled effectively by the media, they will consume it further (GO). Otherwise, they will stop. The decision to further consume media depends on the beliefs and evaluations of the audience, whether they are positive or negative towards the media [13].

2.5 Uses and Gratification Theory and Expectancies (GS)

As per the uses and gratifications expectancy model, the following are the expectancies of individuals consuming media, which are based on their self-evaluation and beliefs regarding the gratifications sought and obtained. Cognitive UGE (Expectations of gaining knowledge and information from media consumption), affective UGE (mood and emotion enhancement related expectations from media consumption), personal integrative UGE (Expectations that it will reinforce personal values and beliefs), social integrative UGE (Expectations that it will enhance social presence and connections), tension free UGE (Expectations from media consumption that it will lead to escapism and entertainment) [14,15].

The expectation from media utilization that it will contribute to the enhancement in knowledge and information is the cognitive uses and gratification expectancy. Online music as a medium is not assumed to be primarily cognitive but is rather considered emotional and affective. According to the latest research, the core gratifications from online music lie in emotional catharsis, mood regulation, personal identity, and companionship, instead of intellectual or factual learning [16]. Kahn et al. (2024) emphasised that the use of music is primarily for entertainment and emotional regulation rather than the attainment of knowledge as music sometimes might cause hindrance to cognitive tasks [17]. Similarly, Pang and Ruan (2024) found that short video application users on mobile are more likely to continue their usage if they experience entertainment value and social connectedness [18]. These emphasise further that the consumption of media is primarily influenced by the affective, social, entertainment, and personal gratifications instead of cognitive ones.

Moreover, it has been reported in previous UGE-based music studies that cognitive expectancy has often emerged as a non-significant or weak factor as compared to other expectancies [1]. These reasons led to the omission of cognitive UGE, as its inclusion could blur the focus from other important factors that truly highlight the impact of online music on psychological well-being. Affective and tension-free UGE were combined as a single construct (AT-UGE), whereas social integrative and personal integrative UGE needs were combined as SIPI-UGE for the current study.

This creates the following hypotheses:

H1(a): Affective and tension-free uses and gratification expectancy needs possess a positive relationship with students’ psychological well-being.

H1(b): Social and personal integrative uses and gratification expectancy needs possess a positive relationship with students’ psychological well-being.

2.6 Perceived Motivations for Study Based on Using Online Music (GS)

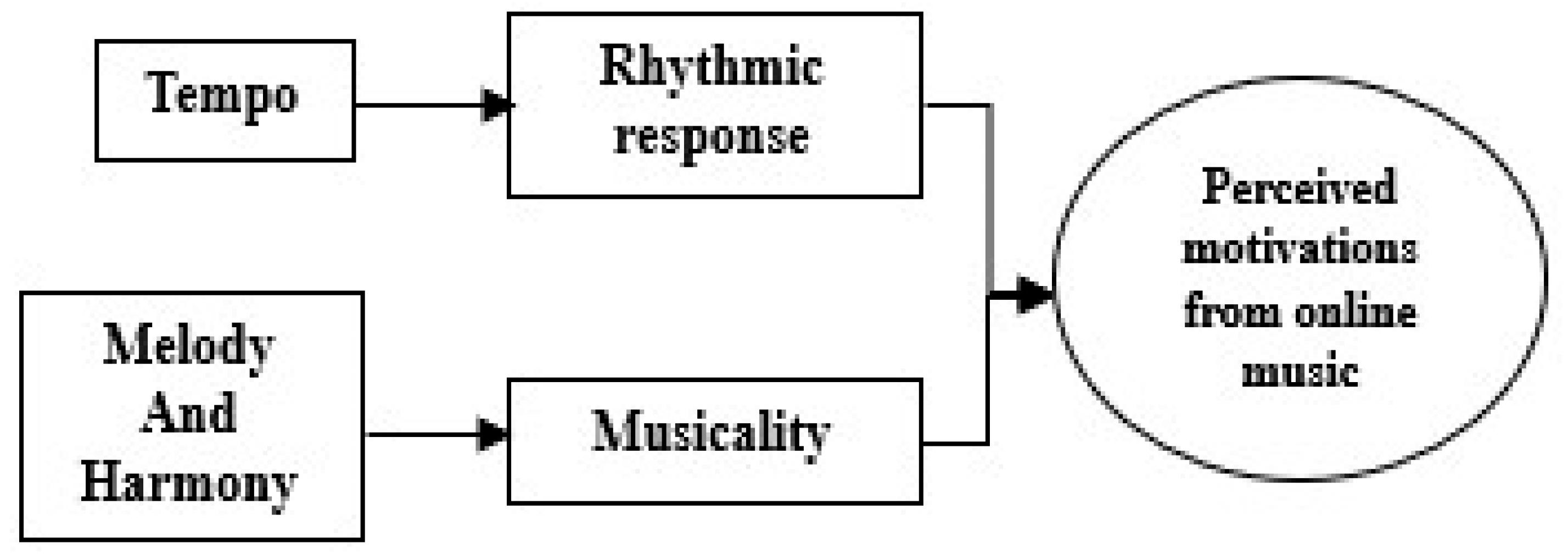

For the purpose of finding out the motivational qualities of music, as stated earlier (refer to Fig. 1), there might be differences in the opinion of who might consider one piece of music motivational or not. According to the researchers, the motivational qualities of music, according to a person, are based on some internal and external factors [10]. The internal factors include rhythmic response and musicality of music, whereas the external factors include the cultural impact on a person and his/her extramusical associations. Karageorghis considered the internal factors more important than the external factors, and their research is also related to the internal factors [19]. There is a need to find out how these perceived motivations from online music impact students in their studies and eventually lead to their better psychological well-being. This leads to Hypothesis 2:

H2: The perceived motivations from online music aid students in their studies, leading to their better psychological well-being.

Refer to Fig. 1 for more details regarding perceived motivations from online music.

Figure 1: Model of internal qualities of music for motivation.

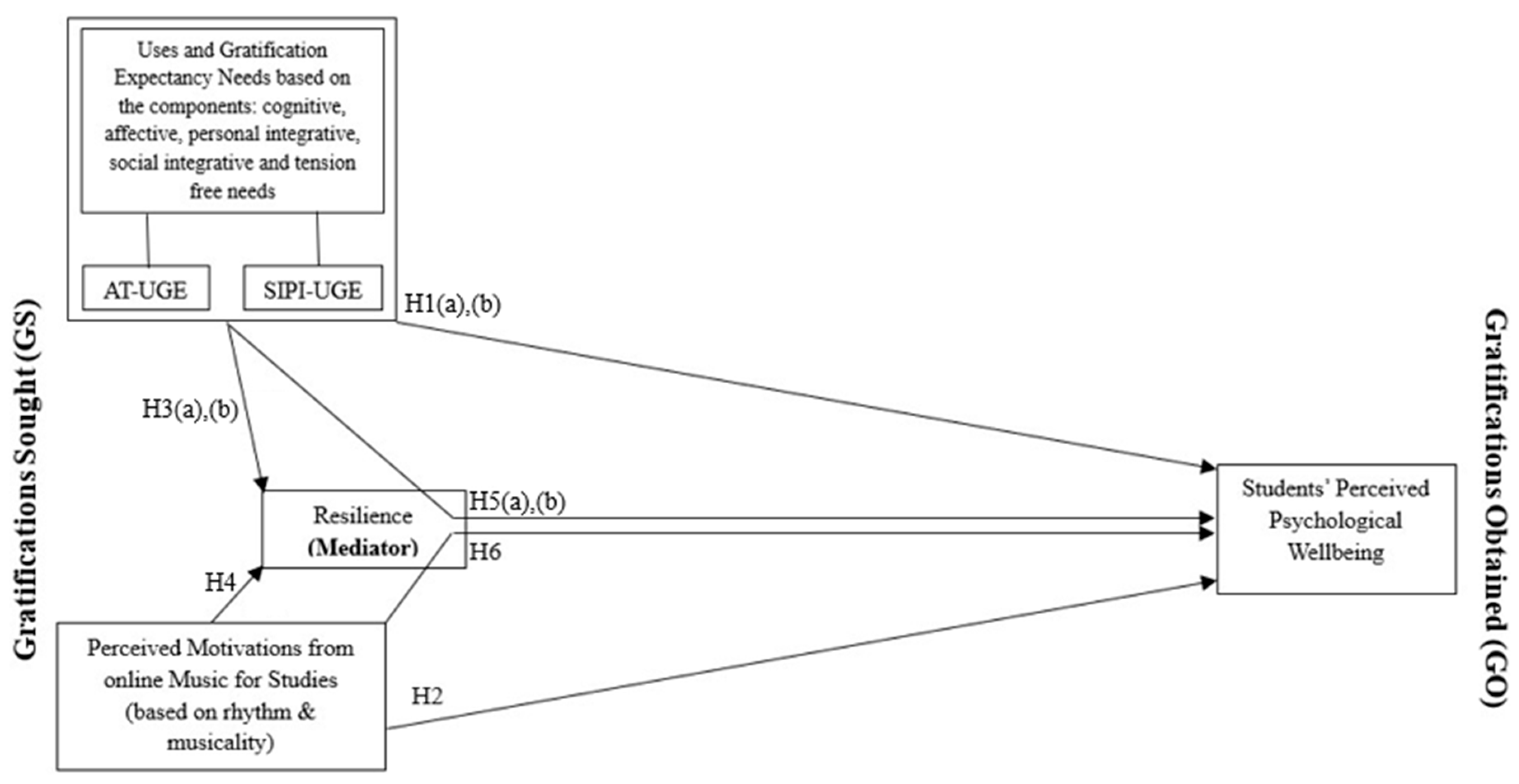

A mediating variable or mediator is incorporated in a framework to explore the observed and outcome variables’ relationship strength. The relationship between the observed variables based on uses and gratifications expectancies and internal motivational elements of music for studies with the outcome variable (perceived well-being) is to be measured, whether the effects of independent variables on resilience will have an enhancement or a deficiency in the perceived well-being levels of students. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H3(a): There is a positive relationship between affective and tension-free UGE of online music and resilience of students

H3(b): There is a positive relationship between social and personal integrative UGE of online music and resilience of students

H4: There is a positive relationship between perceived motivations from online music for studies and the resilience of students

Resilience is the ability to withstand an inconvenient situation and bounce back to normal after hardships. Resilience scores based on online music consumption can be immensely helpful in understanding the gratifications sought by students, i.e., the UGE needs, and the gratifications obtained by them, i.e., perceived well-being. As per Connor Davidson, resilience is divided into scoring based on hardiness which includes emotional regulation (the capacity to manage and modulate one’s emotional responses, including the ability to control impulsive reactions and adapt to emotional challenges), optimism (a positive mindset and tendency to expect positive outcomes, even in the face of adversities), cognitive focus (the capacity to maintain attention, concentrate and process information effectively, particularly in demanding or stressful situations), flexibility/adaptability (The ability to adjust to changing environments and circumstances and modify behavior accordingly as per the demand) and self-efficacy (having self-confidence and belief in own abilities to manage stressors and thrive) [20]. Based on the literature, the following research included resilience as a mediating variable to explore the strength of the relationship and direction between observed and outcome variables:

Gey et al. in their research on emotional intelligence and perceived stress among Malaysian youth, used resilience as a mediator [21]. Bajaj et al. used resilience as a mediator in their research on mindfulness and happiness [22]. Bernabe et al. incorporated resilience as a mediator in their research on the relationship between occupational psychological health and social support [23]. Fig. 2 is the proposed conceptual framework diagram, which includes Uses and gratification expectancies regarding online music and internal qualities of online music for motivation, as outcome variables lying under the category of gratifications sought. Their relationships with the observed variable, i.e., perceived well-being, which lies under the category of gratifications obtained, are influenced by resilience acting as a mediating variable.

Niyazova, in the research on factors affecting psychological well-being, had a prime focus on resilience as the main influencing factor. The research concluded that the key mechanism in achieving psychological well-being is resilience [24]. Klainin-Yobas et al. investigated in their research the relationship between resilience, psychological well-being, and stress. The study concluded with recommendations to promote resilience-building activities and stress management interventions to have a positive effect on psychological well-being [25]. This creates the following hypotheses:

H5(a): There is a positive relationship between affective and tension-free UGE from music, resilience, and psychological well-being of students.

H5(b): There is a positive relationship between social and personal integrative UGE from music, resilience, and psychological well-being of students.

H6: There is a positive relationship between perceived motivations from online music for studies, resilience, and psychological well-being of students.

Refer to Fig. 2 for details regarding the conceptual framework named the Music-UGE framework for student well-being.

Figure 2: Music-UGE (M-UGE) framework for student well-being.

The researcher has applied a mixed-method approach to the following research, as it consists of data collection and analysis methods of both qualitative and quantitative research [26].

The sampling method in this study was cluster sampling. It included universities that offered Creative Multimedia Technology programs; units in the cluster, namely classes, were initially planned to be randomly selected, but during practice, the selection was not fully random. All the participants belonging to these selected groups were invited and encouraged to participate. The lecturers and students of these classes provided consent to participate and contribute efficient data for the study.

The researchers briefed the students about the research and encouraged them to voluntarily take part in the online survey. The students had the option to provide informed consent to continue participating in the survey questions and items. Additionally, students were invited to participate in qualitative interviews.

The population for data collection is the final year creative multimedia undergraduate students, whereas the sample includes 200 survey participants from five central region Malaysian universities, 18 of which also participated as interviewees, yielding an 85% response rate. Demographic details obtained from the participants included their age, ethnicity, GPA, and year of study etc. The reason for obtaining this was to get a better idea of online music utilization by different age groups, ethnicities, and the relation of this to their academic performances/GPAs.

This study was approved by the Multimedia University’s Research Ethics Committee (approval number: EA0652025). Electronic informed consent was obtained from participants before their voluntary participation in both the survey and the interviews.

The data was collected over a period of two months, from October to November 2025, in two phases. The first phase of data collection involved obtaining responses from 200 participating students through a detailed quantitative survey instrument consisting of Likert-scale questions based on related constructs supported by theories. These include instruments, including uses and gratification expectancy needs adapted from [15], motivational factors of music adopted from [19], resilience adopted from [20], and psychological well-being adopted from [27]. The scales belong to previous research and are well known for their frequent utilization in measuring the relevant characteristics. See Table 1 for details regarding the measurement items of the research and Table A1 in Appendix A for more details.

The second phase consisted of collecting data through qualitative semi-structured interviews with 18 participants out of the total 200. Snowball sampling technique was utilised in their recruitment, starting from a small initial group of participants, which increased gradually after they referred others with relevant experiences [28]. In-person and online media, known as Microsoft Teams, were utilised in conducting in-depth interviews with student participants. The duration of each interview was fifteen to twenty minutes. The questions asked were in line with the objectives of the study, with an aim to strengthen them, and the interview guide was developed after a thorough review of the literature and consultations from experts. The participants were briefed about the research and were asked to provide their consent initially after being assured that the data they provided would stay confidential and would be utilised for research purposes only. They were also asked to provide consent for recording audio and videos so that no information they provided would be missed out later. Notes were taken, which were further processed and analysed during the process of thematic analysis.

The data collected was then analysed in two phases, i.e., the interviews’ data by processing it through the stages of thematic analysis which are (1) familiarisation by reading the data to understand it better; (2) generating initial codes by finding important data that are related to the research questions; (3) searching for themes which can represent the specific group of related codes; (4) reviewing themes by checking their accuracy; (5) defining and naming themes to give them meaningful titles; and (6) reporting the findings to answer the research questions [29].

A qualitative analysis software, Taguette (Version 1.5.1; Rémi Rampin, Vicky Rampin & Sarah DeMott; open-source), known for its effective utility in thematic analysis, was used for coding and theme generation. Whereas the questionnaire data was analysed through descriptive analysis in SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to determine the demographic information of participants, and Smart PLS-4 (version 4.1.1; SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) using structural equation modeling. The reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed through Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, convergent and discriminant validity (HTMT ratio), respectively. Whereas the structural model, which included both direct and mediating effects, was evaluated through path coefficient (β) values, statistical significance, and effect sizes to evaluate practical relevance. With the purpose of determining path significance, 5000 resamples bootstrapping were applied to obtain p and t values for path coefficients’ significance [30].

The results are divided into three sections, which include descriptive statistics, themes generated from interviews, and PLS-SEM statistics.

4.1 Participants’ Demographic Information

Two hundred participants (see Table 2) who were undergraduate final year students from five public and private universities in the central Malaysian region were recruited for the study. Along with these, eighteen undergraduate final year students from the same universities agreed to be recruited for qualitative semi-structured interviews. All the students belonged to creative multimedia and related bachelor’s degree programs.

Table 2: Demographic profile of student participants.

| Demographic Variable | Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–20 | 6 | 3.0% |

| 21–23 | 152 | 76.0% | |

| 24–26 | 38 | 19.0% | |

| 27 and above | 4 | 2.0% | |

| Gender | Female | 128 | 64.0% |

| Male | 72 | 36.0% | |

| Ethnicity | Chinese | 66 | 33.0% |

| Indian | 22 | 11.0% | |

| Malay | 108 | 54.0% | |

| Other | 4 | 2.0% | |

| Current GPA | 2.00–2.66 | 5 | 2.5% |

| 2.67–3.33 | 57 | 28.5% | |

| 3.34–3.66 | 76 | 38.0% | |

| 3.67–4.00 | 62 | 31.0% |

According to the descriptive statistics shown in Table 2, 64.0% of the respondents were females, who were in the majority as compared to their counterparts, male students (36.0%). A similar threshold was observed in qualitative interviews, where out of 18 respondents, females were in the majority, i.e., 66.7% and males were 33.3%. The age range of 21–23 was highest among respondents, i.e., 76.0%. In terms of ethnicity, participants in the majority were Malay (54.0%), whereas the highest percentage reported of CGPA range was 38.0% of 3.34–3.66.

4.2 Themes Generated from Interviews

The following were the initial codes generated from interview data in Taguette after the process of familiarization. Refer to Table 3 for more details.

Table 3: Initial codes with description.

| Code | Tag | Description | Number of Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Motivational Factors of Music | Music and its ability to motivate | 12 |

| 2 | Music and Relaxation | Music as a source of ease | 12 |

| 3 | Study Focus | Impact of music on the focus of students during studies | 18 |

| 4 | Personal Connection to Music | Personal association with music | 4 |

| 5 | Music and Mood | Effect of music on emotions | 15 |

| 6 | Well-being | Current state of well-being of students | 7 |

| 7 | Stress Management | Pressures in the lives of students | 4 |

| 8 | Resilience | Current state of resilience of students | 8 |

| 9 | Music Listening Frequency | Students’ music consumption details | 8 |

| 10 | Rhythm of music | Rhythmic quality of music, based on tempo | 3 |

| 11 | Musicality of music | Musicality based on the melody of music | 6 |

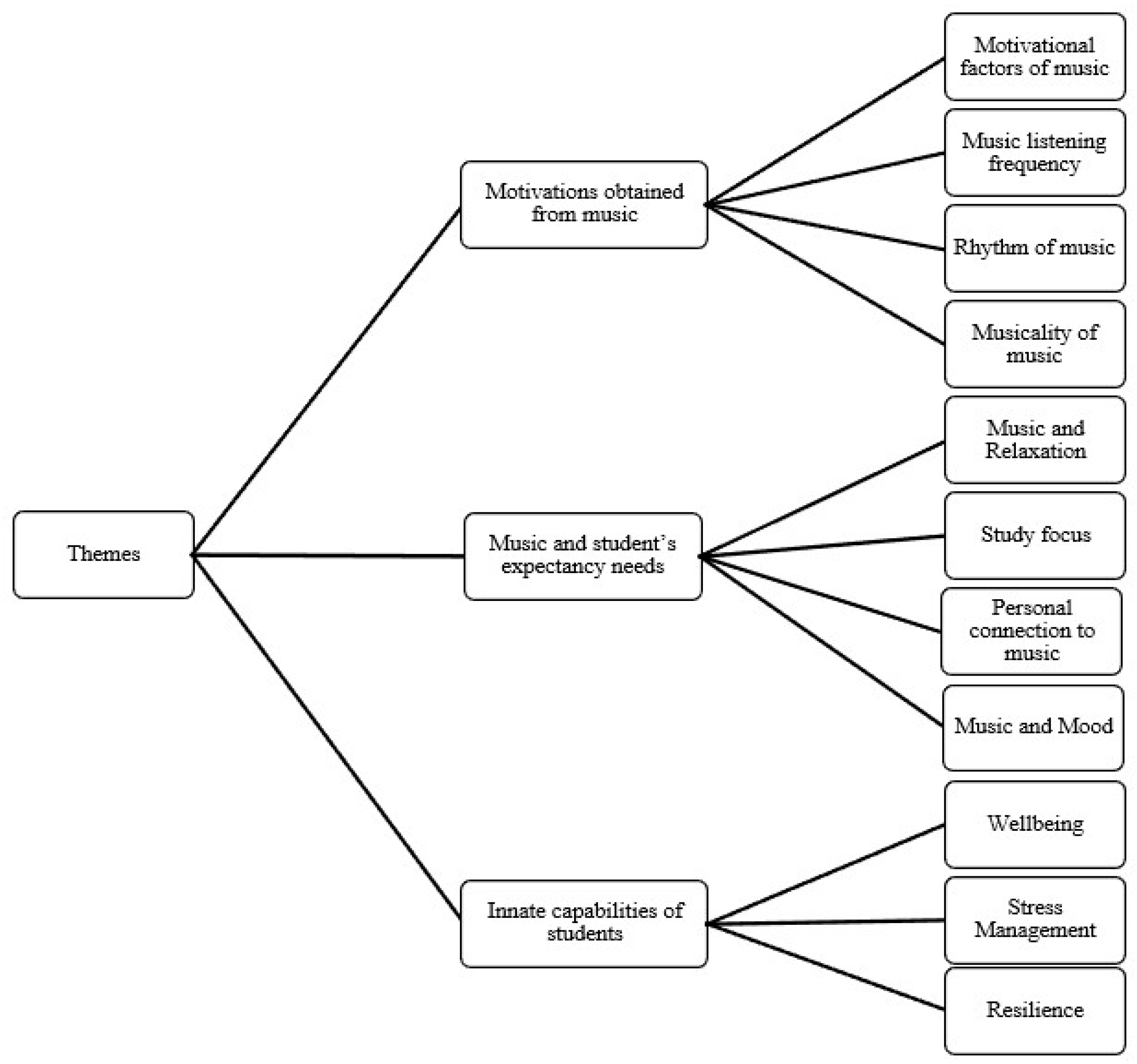

Three central themes emerged from the interview data after following all the stages of thematic analysis, which included motivations obtained from music, music and students’ expectancy needs, and finally, music and innate capabilities of students.

4.2.1 Motivations Obtained from Music (RO1)

All the interviewees agreed that they listen to online music daily, and most of them agreed that music provides motivation to work hard. Apart from a very few respondents, most of them acknowledged the fact that they make use of music even during studies to gain momentum and energy to study effectively. In response to a question about whether the respondents consider the rhythm or melody of the song more motivating, the responses were mixed, but most of them preferred rhythm over melody or a mix of both as a motivational factor for them.

“Music motivates me and gives me hype. It depends on the type of music. I personally believe that upbeat music motivates me.”

It was observed that female participants were inclined towards melody as the more important motivational factor, while the males considered the rhythm of the music they consume as the motivating factor.

“Music that has a high tempo and pitch, like rock, may boost my energy to do the homework.”

The extraordinary utilization of music every day and even during study routines by students and their acknowledgement of the fact that they gain motivation from music justifies the first objective of research, that the motivations gained by students through online music have a positive impact on their psychological well-being.

4.2.2 Music and Students’ Expectancy Needs (RO2)

Participants described what types of gratifications they expect from music consumption. All of them unanimously agreed with the statement that it does fulfill their expectations, but in different ways. Four sub-themes emerged from the current theme:

A significant portion of the participants agreed that they consume music to get a temporary escape from their daily mundane routines and entertain themselves. This theme is directly linked to the tension-free UGE needs as online music provides relaxation and enhances the productivity levels of students, eventually improving their well-being.

“I can multitask, can listen to music while studying and playing, both as it relaxes me and enhances my productivity.”

“To relax and take a break, I consume music first and like to do something else while listening to it, and then sit, continue to do the work.”

When inquired about whether the music they listen to lifts their emotions or not, the majority gave a positive reply.

“Music boosts my energy and lifts my mood.”

It was observed through responses provided by participating students that their personal attachment to certain songs had a more productive impact on their performance and psychological well-being. This theme is linked to the personal integrative UGE.

“If one has feelings attached to certain music, it does improve well-being.”

Some of the students gave credit to music for enhancing their focus during studies by minimizing the surrounding noise.

“I listen to simple background music to minimise other environmental noise in my surroundings.”

“Music cuts off loose thoughts and makes me focus.”

The sub-themes suggest that music satisfies various uses and gratification expectancy needs of students, justifying the second research objective.

Innate Capabilities of Students

It was observed through data analysis that students face various stressors, which include social, academic, and financial pressures [31]. Out of the total interview respondents, most of them reported low resilience levels, whereas their well-being was reported to be satisfactory. Female participants had low resilience and well-being levels as compared to male participants, who were more motivated to withstand pressures and thrive. See Fig. 3 for the graphical representation of final themes created through thematic analysis.

Figure 3: Final themes.

4.3 Addressing RO2 and RO3 through Quantitative Perspective

For a more detailed explanation of the closed-ended data collected from final year students, PLS-SEM was conducted in Smart PLS 4 due to its ability to effectively analyse complex data sets, whether large or small in size [32]. The study employed a measurement model that was reflective in nature. In it, all indicators reflected their relevant latent constructs.

The factor loadings were analysed after initiating the PLS algorithm, and all items exhibited factor loading values above 0.4, which is considered to be satisfactory. The internal reliability and consistency were evaluated through Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha statistics. A threshold of 0.70 and above is widely employed as the criterion for internal consistency.

To ensure satisfactory convergent validity and improved average variance AVE, indicators with low loadings, i.e., <0.70 were deleted from UGE constructs. The deletions include four indicators from AT-UGE and two indicators from SIPI-UGE. All other constructs retained their indicators as their values were up to the mark. Table 4 represents the final items and their factor loadings after deletion, and also a positive correlation between the Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability values of the instrument. The greater the value of (CR) marks an increased dependability and improved internal consistency of variables. Cronbach’s alpha values showed that all constructs were between 0.814 and 0.907 [33], except for one, i.e., AT-UGE, having a value of 0.696 that is regarded as acceptable, provided that all other indicators of the model possess good reliability [34]

The average variance extracted (AVE) was also measured to find out the convergent validity. The recommended value threshold is considered to be 0.5, which indicates that the AVE has been successful in explaining at least 50% variance of each indicator. The values for AVE are also displayed in Table 4 for all constructs, which are all found to exceed 0.5 across groups of data. The minimum values of AVE surpass the 0.5 threshold [35].

Table 4: Loadings, validity, reliability and AVE of constructs.

| Construct | Item | Loading | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT-UGE | ATUGE1 | 0.765 | 0.519 | 0.696 | 0.702 | 0.811 |

| ATUGE2 | 0.761 | |||||

| ATUGE3 | 0.693 | |||||

| ATUGE4 | 0.657 | |||||

| SIPI-UGE | SIPIUGE1 | 0.772 | 0.514 | 0.814 | 0.872 | 0.862 |

| SIPIUGE3 | 0.659 | |||||

| SIPIUGE4 | 0.621 | |||||

| SIPIUGE1 | 0.798 | |||||

| SIPIUGE2 | 0.636 | |||||

| SIPIUGE4 | 0.789 | |||||

| Perceived Motivations from online Music for Studies | BMRI3-1 | 0.778 | 0.644 | 0.890 | 0.908 | 0.915 |

| BMRI3-2 | 0.735 | |||||

| BMRI3-3 | 0.864 | |||||

| BMRI3-4 | 0.838 | |||||

| BMRI3-5 | 0.746 | |||||

| BMRI3-6 | 0.845 | |||||

| Resilience | CD-RISC-1 | 0.692 | 0.546 | 0.907 | 0.912 | 0.923 |

| CD-RISC-2 | 0.761 | |||||

| CD-RISC-3 | 0.613 | |||||

| CD-RISC-4 | 0.741 | |||||

| CD-RISC-5 | 0.731 | |||||

| CD-RISC-6 | 0.745 | |||||

| CD-RISC-7 | 0.719 | |||||

| CD-RISC-8 | 0.810 | |||||

| CD-RISC-9 | 0.760 | |||||

| CD-RISC-10 | 0.794 | |||||

| Psychological Well-being | SWEMWBS-1 | 0.651 | 0.550 | 0.863 | 0.875 | 0.895 |

| SWEMWBS-2 | 0.736 | |||||

| SWEMWBS-3 | 0.698 | |||||

| SWEMWBS-4 | 0.786 | |||||

| SWEMWBS-5 | 0.823 | |||||

| SWEMWBS-6 | 0.676 | |||||

| SWEMWBS-7 | 0.802 |

The discriminant validity of the constructs was determined through the Heterotrait-Monotrait correlation ratio. Table 5 shows discriminant validity values through HTMT. According to researchers, HTMT values are satisfactory when below 0.90. All the values obtained were below the required threshold [36].

Table 5: Discriminant validity (HTMT).

| Constructs | AT-UGE | SIPI-UGE | Perceived Motivations from Online Music for Studies | Resilience | Psychological Well-Being |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT-UGE | - | ||||

| SIPI-UGE | 0.63 | - | |||

| Perceived Motivations from Online Music for Studies | 0.31 | 0.35 | - | ||

| Resilience | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.28 | - | |

| Psychological Well-being | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.61 | - |

Moreover, the effect size f2 examined to identify the predictors’ practical significance indicted the presence of a large effect for one of the predictors i.e., Resilience and Psychological Well-being (f2 = 0.461), small effects for two predictors, i.e., Perceived motivations from online music and Resilience (f2 = 0.037), SIPI-UGE and Resilience (f2 = 0.044) and no effect for one predictor i.e., AT-UGE and Resilience (f2 = 0.000) [37]. This indicates that while some predictors substantially contribute to the outcomes, others possess negligible or limited practical impact [32]. Refer to Table 6 for more details.

Table 6: Effect size f2.

| Predictors | f-Square |

|---|---|

| AT-UGE → Resilience | 0.000 |

| Perceived Motivations from Online Music for Studies → Resilience | 0.037 |

| Resilience → Psychological Well-being | 0.461 |

| SIPI-UGE → Resilience | 0.044 |

4.4 Structural Equation Modeling—Hypothesis Testing

The initial step in the structural model is to assess the collinearity. Before conducting the latent variable analysis, it is important to minimise the collinearity between constructs, which is done by evaluating the values of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The ideal VIF values need to be close to 3 or below [32]. All the inner VIF values ranged from 1 to 1.348, which were satisfactory, raising no concerns in the investigation. See Table 7 for more details.

Table 7: Collinearity (VIF).

| Constructs | VIF |

|---|---|

| AT-UGE → Resilience | 1.293 |

| Perceived Motivations from Online Music for Studies → Resilience | 1.127 |

| Resilience → Psychological Wellbeing | 1.000 |

| SIPI-UGE → Resilience | 1.348 |

PLS-SEM is a non-parametric data analysis type in which the distribution of data is not assumed. For this reason, bootstrapping is applied to aid in normalising the data and obtaining the significance of the path between the constructs. The strength or power of the relation between the latent variables is indicated by the path coefficient value. Through bootstrapping, t and r squared values are also obtained. Where t values measure the significance as well as the size of path coefficients. It is recommended by researchers to bootstrap at least 5000 samples to enable them to be considered sufficient [32]. As per the recommendation, the study also employs 5000 samples.

4.4.1 Direct Effect Addressing RO2 through Quantitative Approach

According to researchers, the p values should be below 0.05 (p < 0.05) while the t value needs to be more than or equal to 1.645 (t ≥ 1.645), also β values of ≈ 0.10, 0.30, and ≥ 0.50 mostly display small, moderate, and strong effects [38]. Table 8 highlights that the results obtained support H1(b), H2, H3(b), and H4 but don’t support H1(a) and H3(a). H1(a) displays the absence of a relationship that can be considered significant between one UGE construct, i.e., AT-UGE, with Psychological Well-being, while the other UGE construct, i.e., SIPI-UGE, displays a presence of a significant relationship with Psychological Well-being, H1(b). H2 reveals a significant relationship between internal motivational factors of music and psychological well-being. Similarly, H3(a) reveals an insignificant relationship between AT-UGE and resilience, while H3(b) displays a significant relationship between SIPI-UGE and resilience. Finally, H4 shows a significant relationship between perceived motivations from music for studies with resilience. Table 8 shows hypothesis testing results for the direct effect.

Table 8: Hypothesis testing results for direct effect (RQ2).

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Beta β | t Values | p Values | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1(a) | AT-UGE → Psychological Well-being | 0.012 | 0.271 | 0.787 | Not Supported |

| H1(b) | SIPI-UGE → Psychological Well-being | 0.128 | 2.824 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H2 | Perceived Motivations from online Music for Studies → Psychological Well-being | 0.107 | 2.807 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H3(a) | AT-UGE → Resilience | 0.021 | 0.276 | 0.783 | Not Supported |

| H3(b) | SIPI-UGE → Resilience | 0.228 | 2.897 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H4 | Perceived Motivations from online Music for Studies → Resilience | 0.190 | 2.944 | 0.003 | Supported |

4.4.2 Indirect Effect Addressing RO3 through Quantitative Approach

Table 9 comprises a mediation analysis summary. H5(a) displays that there exists sufficient statistics-based evidence to establish or prove a connection between one UGE construct, i.e., SIPI-UGE, with resilience and psychological well-being, while H5(b) displays vice versa for the other UGE construct, i.e., AT-UGE. This suggests that the relationship between one UGE construct with psychological well-being is mediated by resilience, while the other UGE construct’s relationship with psychological well-being is not mediated by resilience, i.e., AT-UGE. H6 predicts a positive relationship between perceived motivations from music for studies and psychological well-being, which is mediated by resilience.

Table 9: Hypothesis testing on mediation.

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Beta β | t Values | p Values | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5(a) | SIPI-UGE → Resilience → Psychological Well-being | 0.128 | 2.824 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H5(b) | AT-UGE → Resilience → Psychological Well-being | 0.012 | 0.271 | 0.787 | Not Supported |

| H6 | Perceived Motivations from online Music for Studies → Resilience → Psychological Well-being | 0.107 | 2.807 | 0.005 | Supported |

Fig. 4 displays the relationships between multiple factors in the study of Uses and Gratification Expectancies (UGE), Perceived Motivations from online Music for Studies, Resilience, and Psychological Well-being. The model was created in Smart PLS 4 using the PLS-SEM algorithm.

Figure 4: Path analysis model. Note: The values reported are standardised beta coefficients β with corresponding p-values present in parentheses.

The mixed-method study employed triangulation to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings, which included comparing and converging the qualitative and quantitative data. This study found that students’ attention to music influenced their psychological well-being. It supports the theoretical understanding that attention to music— particularly rhythmic engagement— creates opportunities to sharpen focus and regulate emotions through internal processes, as highlighted in previous empirical studies [10,39]. Motivation sustains well-being by promoting positive behaviors like problem-solving and increased resilience in challenging situations. The sense of belonging and emotional benefits derived from music further strengthen these experiences [40]. Specifically, rhythm enhances students’ sense of familiarity, fostering responsiveness to their emotions and cultivating a deeper sense of belonging, as mentioned in social cognition [40]. In other words, motivation derived from online music plays an important role in increasing students’ resilience and psychological well-being. Based on the UGE Theory, individuals use media to fulfill certain needs such as entertainment, information, or emotional regulation [15]. Thus, motivation arising from music consumption can have a direct impact because it is in line with students’ expectations to get positive outcomes from music. These findings imply that educational institutions and stakeholders can integrate music as an intervention tool to increase student motivation in the context of learning and psychological well-being. Support programs or activities can leverage music not only as entertainment but as a strategic medium to increase focus, reduce stress, and foster mental well-being.

Interestingly, while the qualitative results derived from thematic analysis revealed that online music consumption fulfills the uses and gratification expectations of the vast majority of students, i.e., it enhances their mood, provides them with entertainment, and relieves their stress, which are the indications of strong psychological and emotional engagement with online music, quantitative results obtained from PLS-SEM presented a contrasting depiction. According to it, online music partially fulfills the expectations that students have of it. While it fulfills their social and personal integrative expectations, it does not satisfy their affective and tension-free needs.

This divergence across the two strands of data may be explained by variation in how the constructs were implemented in the data. The quantitative questionnaire items measured the tension-free and affective needs in a generalised and standardised manner with a specific set of answers to choose from, possibly missing the personalised or situational nature of the use of online music. Whereas the qualitative interviews allowed an in-depth understanding of individual experiences, allowing students to express in various ways that online music contributes to the enjoyment and regulation of emotions [41]. Under the Uses and Gratification Expectancies framework, the divergences display that the gratifications obtained from online music are non-uniform across individuals or contexts. While there was a vivid emergence of affective and tension-free needs in the qualitative data, the quantitative model might have indicated an increased heterogeneous music utilization pattern across the larger sample. Moreover, the mediation analysis revealed further that resilience did not mediate the relationships between affective and tension-free UGE with Psychological well-being, while it significantly mediated the relation between social and personal integrative UGE with Psychological well-being. This indicates that the role of music in the enhancement of psychological well-being gets pronounced further when it strengthens the resilience of students through the mechanisms of personal growth and social connection, rather than just the fulfillment of affective or entertainment-oriented gratifications. Feng et al. state music consumption as a strong intervention in enhancing resilience and well-being by discussing its significance in reducing anxiety, stress, and depression by fostering personal, social, and emotional growth [42].

Also, the mediation analysis of resilience between the relationship of perceived motivations from online music and the psychological well-being of students is found to be significant. Thus, it supports the objective of the study that students obtain motivation from online music, which strengthens their psychological well-being by enhancing their resilience levels. This is, in fact, endorsed by Koehler et al. (2023), in their research, where they found that those individuals who engaged more with music had better resilience and lower mental health issues [43]. The potential limitations of the study include selection bias as the interviewees were selected through snowball sampling, recall bias, or social desirability as the survey data were self-reported, relying on honesty and the memory of participants.

6 Conclusions and Future Research

The paper proposes a detailed conceptual framework based on uses and gratification expectancy needs that students have, regarding their online music consumption, which in this paper is called the Music-UGE Framework (M-UGE, Fig. 4). It also focuses on the motivations obtained by them through the music they consume for studies and finally, the overall effects of these two on psychological well-being. Resilience, as per the conceptual framework, works as a mediating variable between the observed and outcome variables.

The study examined how different uses and gratification expectations (affective, tension-free, social, and personal integrative needs) of final year Malaysian university students, from the online music they consume, relate to their psychological well-being, with resilience acting as a mediator.

It also explored how the motivations obtained from online music by students enhance their psychological well-being, with resilience acting as a mediator.

Qualitative and Quantitative analysis both endorsed the fact that students gain motivations from online music which enhances their psychological well-being and resilience significantly mediates this relationship between them.

Qualitative analysis of the data revealed that most of the students mainly utilise online music for their social, personal, affective, and tension-free UGE needs, whereas the quantitative data revealed that they utilise online music only to satisfy their personal and social integrative UGE needs, rejecting the hypothesis that online music also satisfies their affective and tension-free uses and gratification expectations.

PLS-SEM further revealed that resilience significantly mediates the relationship between social and personal integrative UGE and psychological well-being, whereas it did not mediate the relationship between psychological well-being and affective and tension-free UGE.

The divergence in the findings related to online music’s uses and gratification expectancies highlights that the use of online music is subjective and context-dependent. This further suggests that the consideration of situational, individual, and contextual factors needs to be kept in mind by researchers while studying online music gratifications.

Future studies could provide an extension to this research by exploring a wide range of respondents belonging to different cultural, educational, and age groups to investigate how the varying contextual factors impact online music-related gratifications, motivations, and resilience. Future research can also investigate additional potential mediators and moderators, such as genre preferences, coping styles, or emotional intelligence, to further enrich and highlight the knowledge of pathways through which online music affects psychological well-being.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This project is funded by Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2023/SSI07/MMU/02/3) which is awarded to the Multimedia University. The project is led by the second author.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Muhammad Ali Malik, Koo Ah Choo; methodology, Muhammad Ali Malik; resources, Hawa Rahmat, Elyna Amir Sharji, Teoh Sian Hoon, Sabariah Eni, Lim Kok Yoong; data curation and writing—original draft preparation, Muhammad Ali Malik, Koo Ah Choo, Hawa Rahmat. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Multimedia University’s Research Ethics Committee, with the approval number: EA0652025. Electronic informed consent was obtained from participants before their voluntary participation in both the survey and the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| UGE | Uses and Gratification Expectancy |

| GS | Gratification Sought |

| GO | Gratification Obtained |

| AT-UGE | Affective and Tension Free UGE |

| SIPI-UGE | Social and Personal Integrative UGE |

Table A1: Questionnaire instrument.

| Item | Category |

|---|---|

| 1. I like to talk to others about online music. | AUGE1 |

| 2. I like showing my friends how to use online music. | AUGE2 |

| 3. Online music streaming platforms are good to look at. | AUGE3 |

| 4. I enjoy working with online music | AUGE4 |

| 5. Using online music is relaxing for me. | PIUGE1 |

| 6. I can search and navigate through online music content. | PIUGE3 |

| 7. Using online music keeps me from feeling lonely. | PIUGE4 |

| 8. Using online music gives me feedback I need from others. | SIUGE1 |

| 9. Using online music allows me to be virtually connected anywhere. | SIUGE2 |

| 10. Using online music prepares me to join the extended community. | SIUGE4 |

| 11. The rhythm of this music would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 12. The style of this music (i.e., rock, dance, jazz, hip-hop, etc.) would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 13. The melody (tune) of this music would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 14. The tempo (speed) of this music would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 15. The sound of the instruments used (i.e., guitar, synthesiser, saxophone, etc.) would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 16. The beat of this music would motivate me during studies. | BMRI-3 |

| 17. I am able to adapt when changes occur. | Resilience |

| 18. I can deal with whatever comes my way. | Resilience |

| 19. I try to see the humorous side of things when I am faced with problems. | Resilience |

| 20. Having to cope with stress can make me stronger. | Resilience |

| 21. I tend to bounce back after illness, injury, or other hardships. | Resilience |

| 22. I believe I can achieve my goals, even if there are obstacles. | Resilience |

| 23. Under pressure, I stay focused and think clearly. | Resilience |

| 24. I am not easily discouraged by failure. | Resilience |

| 25. I think of myself as a strong person when dealing with life’s challenges and difficulties. | Resilience |

| 26. I am able to handle unpleasant or painful feelings like sadness, fear, and anger. | Resilience |

| 27. I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future. | Well-being |

| 28. I’ve been feeling useful. | Well-being |

| 29. I’ve been feeling relaxed. | Well-being |

| 30. I’ve been dealing with problems well. | Well-being |

| 31. I’ve been thinking clearly. | Well-being |

| 32. I’ve been feeling close to other people. | Well-being |

| 33. I’ve been able to make up my own mind about things. | Well-being |

References

1. Lonsdale AJ , North AC . Why do we listen to music? A uses and gratifications analysis. British J Psychology. 2011; 102( 1): 108– 34. doi:10.1348/000712610x506831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Karageorghis CI , Terry PC , Lane AM . Development and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise and sport: the Brunel Music Rating Inventory. J Phys Sci. 1999; 17( 9): 713– 24. doi:10.1080/026404199365579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Razali CSMM , Ma’rof AA . The impact of music preferences, listening context, and social music engagement on emotional wellbeing among Malaysian youth. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2024; 14( 12): 756– 69. doi:10.6007/ijarbss/v14-i12/24022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chin T , Rickard N . Music listening and emotional wellbeing: a scoping review. Psychol Music. 2022; 50: 153– 69. [Google Scholar]

5. Wang S-M , Chen T-H . Participatory artificial intelligence generated music for pressure healing. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Grids & Clouds (ISGC) 2024; 2024 Mar 24–29; Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

6. Zaatar MT , Alhakim K , Enayeh M , Tamer R . The transformative power of music: insights into neuroplasticity, health, and disease. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023; 35: 100716. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang X , Xie Z , Du G . Research on the intervention effect of vibroacoustic therapy in the treatment of patients with depression. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024; 26( 2): 149– 60. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.030755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Waterhouse J , Hudson P , Edwards B . Effects of music tempo upon submaximal cycling performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010; 20: 662– 9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00948.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. McCraty R , Barrios-Choplin B , Atkinson M , Tomasino D . The effects of different types of music on mood, tension, and mental clarity. Altern Ther Health Med. 1998; 1: 75– 84. [Google Scholar]

10. Karageorghis CI . Applying music in exercise and sport. Champaign, IL, USA: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2007. doi:10.5040/9781492595229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Krastel Z , Molson J , Bassellier G , Ramaprasad J . Music is social: from online social features to online social connectedness. In: Proceedings of the ICIS 2015 Proceedings; 2015 Dec 13–16; Fort Worth, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

12. Littlejohn SW , Foss KA , Oetzel JG . Theories of human communication. 11th ed. Prospect Heights, IL, USA: Waveland Press, Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

13. Rayburn JD . Merging uses and gratification and expectancy value theories. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 1984. doi:10.1177/009365084011004005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mondi M , Woods P , Rafi A . Students’ ‘uses and gratification expectancy’ conceptual framework in relation to E-learning resources. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2007; 8( 3): 435– 49. doi:10.1007/BF03026472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang M-H , Yang T-Y , Chen Y-S . How workers engage in social networking sites at work: a uses and gratification expectancy perspective. Int J Organ Innov. 2016; 8: 161– 76. [Google Scholar]

16. Ziv N , Moran T , Chan CW . Active versus passive engagement with music and emotional regulation. Music Ther Perspect. 2022; 40( 2): 120– 34. [Google Scholar]

17. Kahn JH , Enevold KC , Feltner-Williams D , Ladd K . Using music to feel better: are different emotion-regulation strategies truly distinct? Psychol Music. 2024. doi:10.1177/03057356241258959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pang H , Ruan Y . Disentangling composite influences of social connectivity and system interactivity on continuance intention in mobile short video applications: the pivotal moderation of user-perceived benefits. J Retail Consum Serv. 2024; 80: 103923. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Karageorghis CI , Terry PC . Inside sport psychology. London, UK: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2011. doi:10.5040/9781492595564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Connor KM , Davidson J . Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) © Manual. 2018 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: www.cd-risc.com. [Google Scholar]

21. Gey JW , Yap CK , Leow K , Lo YY . Resilience as a mediator between emotional intelligence (EI) and perceived stress among young adults in Malaysia. Discov Ment Health. 2025; 5( 1): 37. doi:10.1007/s44192-025-00166-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bajaj B , Khoury B , Sengupta S . Resilience and stress as mediators in the relationship of mindfulness and happiness. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 771263. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.771263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bernabé M , Botia JM . Resilience as a mediator in emotional social support’s relationship with occupational psychology health in firefighters. J Health Psychol. 2016; 21( 8): 1778– 86. doi:10.1177/1359105314566258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Niyazova A , Madaliyeva Z . Impact of resilience on psychological well-being. J Intellect Disabl Diagn Treat. 2022; 10( 4): 178– 86. doi:10.6000/2292-2598.2022.10.04.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Klainin-Yobas P , Vongsirimas N , Ramirez DQ , Sarmiento J , Fernandez Z . Evaluating the relationships among stress, resilience and psychological well-being among young adults: a structural equation modelling approach. BMC Nurs. 2021; 20( 1): 119. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00645-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mcleod S . Mixed methods research guide with examples. London, UK: Simply Psychology; 2024. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.31329.93286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Stewart-Brown S , Tennant A , Tennant R , Platt S , Parkinson J , Weich S . Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009; 7( 1): 15. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-7-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ting H , Memon MA , Thurasamy R , Cheah JH . Snowball sampling: a review and guidelines for survey research. Asian J Bus Res. 2025; 15( 1): 1– 15. doi:10.14707/ajbr.250186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Maguire M , Delahunt B . Doing a Thematic Analysis: a Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars. AISHE J. 2017; 8( 3): 3352– 9. [Google Scholar]

30. Haji-Othman Y , Sheh Yusuff MS , Md Hussain MN . Data analysis using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in conducting quantitative research. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2024; 14( 10): 2380– 8. doi:10.6007/ijarbss/v14-i10/23364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xu T , Zuo F , Zheng K . Parental educational expectations, academic pressure, and adolescent mental health: an empirical study based on CEPS survey data. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024; 26( 2): 93– 103. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.043226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Anthonysamy L . Self-regulated learning strategies in digital learning MBA technology and innovation management [ dissertation]. Selangor, Malaysia: Multimedia University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. Ramayah T , Cheah J-H , Chuah F , Ting H . Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: an updated and practical guide to statistical analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

34. Hair JF , Black WC , Babin BJ , Anderson RE . Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. New York, NY, USA: Pierson Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

35. Hair JF , Tomas G , Hult M , Ringle CM , Sarstedt M . A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd edition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ramli NA , Latan H , Nartea GV . Why should PLS-SEM be used rather than regression? Evidence from the capital structure perspective. In: International series in operations research and management science. New York, NY, USA: Springer New York LLC.; 2018. p. 171– 209. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71691-6_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hair JF , Tomas G , Hult M , Ringle CM , Sarstedt M . A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

38. Chua YP . A step-by-step guide to SMARTPLS 4: data analysis using PLS-SEM, CB-SEM, process and regression. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Researchtree; 2024. [Google Scholar]

39. Bangquiao S , Bangquiao M , Galigao R . Music as a therapy to students' mental health. Pantao Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2024; 3: 290. doi:10.69651/PIJHSS030427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yang Z , Su Q , Xie J , Su H , Huang T , Han C , et al. Music tempo modulates emotional states as revealed through EEG insights. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 8276. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-92679-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Feng Y , Wang M . Effect of music therapy on emotional resilience, well-being, and employability: a quantitative investigation of mediation and moderation. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 47. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-02336-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Koehler F , Schäfer SK , Lieb K , Wessa M . Differential associations of leisure music engagement with resilience: a network analysis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023; 23( 3): 100377. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2023.100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hausberger A , Parada-Cabaleiro E , Schedl M . Why context matters: exploring how musical context impacts user behavior, mood, and musical preferences. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization; 2025 Jun 16–19; New York, NY, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2025. doi:10.1145/3699682.3728354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools