Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mental Health and Well-Being of Doctoral Students: A Systematic Review

1 School of Economics and Management, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, 116024, China

2 Graduate School of Education, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, 116024, China

3 School of Education, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300354, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinqiao Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health and Subjective Well-being of Students: New Perspectives in Theory and Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.074063

Received 30 September 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: Mental health concerns among doctoral students have become increasingly prominent, with consistently low levels of well-being making this issue a critical focus in higher education research. This study aims to synthesize existing evidence on the mental health and well-being of doctoral students and to identify key factors and intervention strategies reported in the literature. Methods: A systematic review was conducted to examine the determinants and interventions related to doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Relevant studies were comprehensively searched in Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCO, with the final search conducted on September 19, 2025. Records were screened according to predefined criteria: empirical studies on doctoral students’ mental health or well-being published in English were included, while non-empirical, non-English, and non-doctoral-student-focused studies were excluded. A total of 56 studies were included after rigorous screening. Results: Doctoral students’ mental health and well-being are shaped by multiple interacting factors across individual, academic, interpersonal, organizational, and environmental levels. Moreover, variations in gender, identity, discipline, study stage, and institutional context may further exacerbate or mitigate psychological distress. Existing intervention studies primarily focus on three approaches: psychologically oriented training, practice-based behavioral and learning programs, and relationship- or support network-based initiatives. Conclusion: This review offers integrated evidence on doctoral students’ mental health and well-being and highlights the need for universities to assume greater responsibility in developing systematic and responsive support mechanisms. Current research remains limited by insufficient cross-cultural comparison, a lack of intersectional perspectives, and a scarcity of large-scale, long-term evaluations of intervention effectiveness. Future studies should give greater attention to institutional contexts and vulnerable groups while expanding the scope and rigor of intervention research.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileDoctoral students occupy a distinctive position within higher education. As the most highly trained group in their disciplines, they represent both an essential national intellectual resource and a key driving force in knowledge production [1]. Compared with undergraduates and master’s students, doctoral candidates encounter more complex and multifaceted pressures, including sustained academic demands, financial burdens, and uncertainties about future career prospects [2,3]. Consequently, their overall levels of mental health and well-being tend to be lower [4,5], with higher prevalence rates of depression and anxiety than in the general population [6]. Studies have shown that doctoral students report more frequent physical symptoms, anxiety, sleep disturbances, behavioral issues, and depressive symptoms than graduates who did not pursue further study [7,8,9,10].

Mental health challenges among doctoral students not only undermine their quality of life but may also exert long-term effects on their academic career trajectories, ultimately influencing the broader functioning of higher education systems. On one hand, psychological distress can lead to academic stagnation, dropout, and research burnout, directly weakening the effectiveness of doctoral training [11]. On the other hand, the resulting loss of talent and psychological imbalance may jeopardize research productivity and the sustainable development of academic human capital, thereby threatening the stability of the knowledge innovation system and the overall quality of higher education [12,13].

The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. It is an integral component of health and well-being” [14]. Well-being, in contrast, reflects individuals’ overall evaluations of their lives [15]. Although conceptually distinct, mental health and well-being are closely intertwined and are often examined within a unified analytical framework. To provide a comprehensive synthesis of doctoral students’ psychological status, the present review includes studies addressing both mental health and well-being without making a strict conceptual distinction.

Existing research has primarily focused on two major domains: influencing factors and intervention strategies. Regarding influencing factors, economic strain, limited resources, academic workload, and career uncertainty have been consistently linked to deteriorations in mental health [1,11,16], whereas institutional support, high-quality supervision, and intrinsic motivation act as protective factors [5]. Meanwhile, well-being—an increasingly prominent topic—has been explored from multiple perspectives, including individual, interpersonal, and institutional contexts, emphasizing doctoral students’ overall life experiences and subjective satisfaction [12,15,17]. In terms of interventions, although empirical evidence remains limited, pilot programs have begun testing various approaches to enhance doctoral students’ mental health and well-being, such as psychological counseling and training, peer-support initiatives, improved supervisor–student interactions, and policy-level reforms [18].

Notably, recent studies have begun incorporating the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model to enhance explanatory power in examining doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Originally developed to explain stress and performance outcomes in occupational settings, the JD-R model links work-related resources to positive well-being and productivity outcomes. In this context, the doctoral training environment can be conceptualized as a distinct form of “workplace”, where resources such as supervisory support and opportunities for skill development function as critical job resources. These resources can foster doctoral performance through enhanced well-being [19,20].

While the JD-R model offers a promising and integrative perspective, there remains a lack of systematic reviews applying this framework to doctoral student populations, and existing literature is still fragmented in its coverage. Some existing reviews focus primarily on the prevalence of specific psychological disorders, overlooking the underlying stress mechanisms, moderating factors, and multilevel influences; others pay limited attention to subjective well-being and positive psychological resources. Therefore, a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence is needed to identify key determinants and intervention approaches, thereby constructing a more integrated framework for understanding doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Therefore, this review aims to address three key questions: (1) What factors influence doctoral students’ mental health and well-being? (2) What interventions have been proposed, and what are their effects? (3) How can future research further advance this field?

To comprehensively capture studies on doctoral students’ mental health and subjective well-being, we conducted systematic searches in four databases: Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCO (including PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, the Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection). The search period was restricted from 01 January 2010, to 19 September 2025. The search strategy was structured around three key dimensions: the study population (doctoral students), the study topic (mental health), and the outcome constructs (subjective well-being and quality of life). These dimensions were operationalized using relevant keywords and combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR) to ensure both comprehensiveness and precision. Full search terms, database-specific strategies, and inclusion/exclusion criteria are provided in Supplementary Material 1. Also, this study follows the PRISMA 2020 checklist (see Supplementary Material 2).

2.2 Screening Process and Results

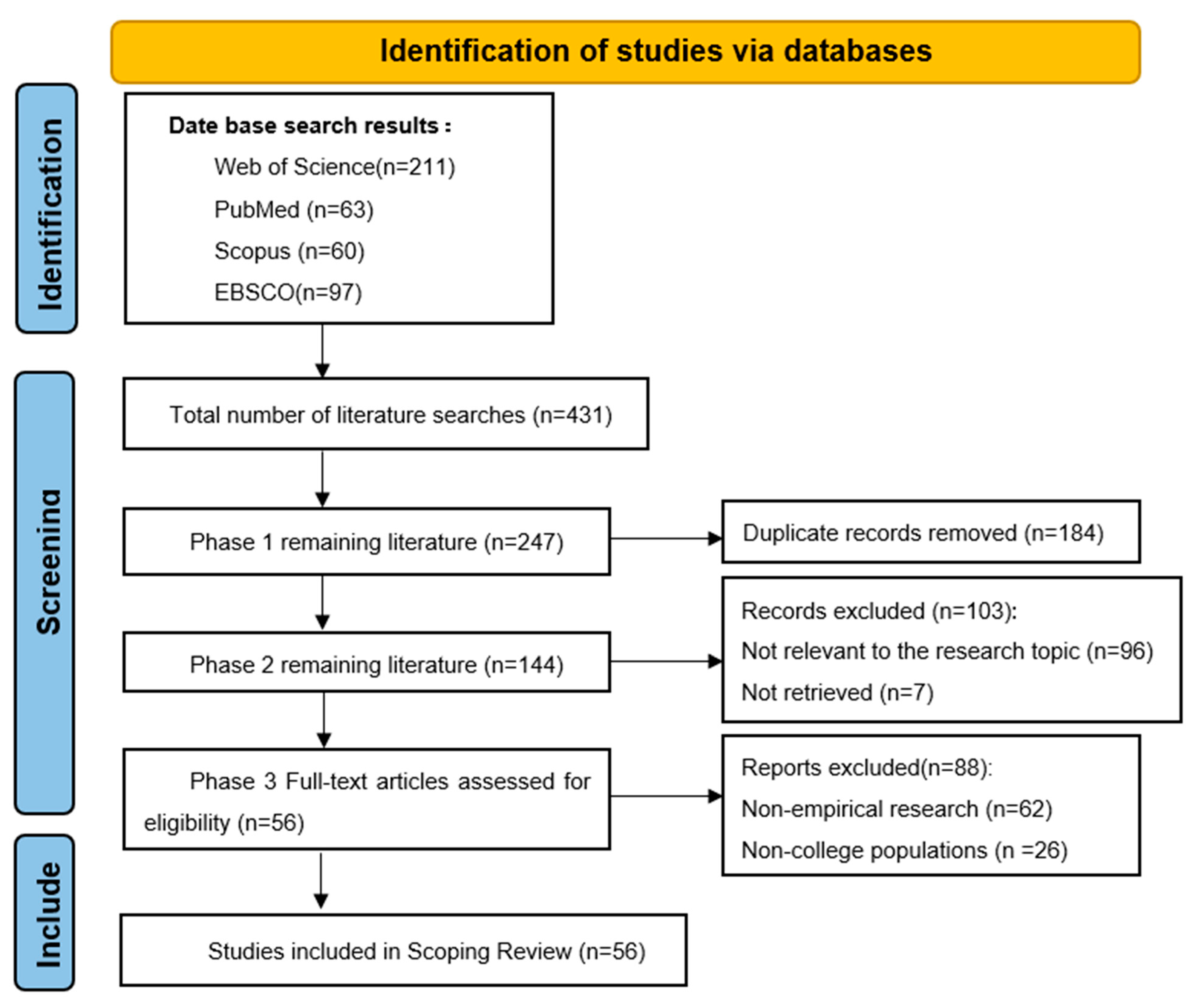

The screening process included three stages: de-duplication in Zotero, title/abstract screening, and full-text review using Rayyan (version 1.6.3). Two researchers independently screened all studies, with disagreements resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram was used to illustrate the study selection process (Fig. 1). The database search identified a total of 431 records. After removing duplicates, 247 articles remained. Title and abstract screening excluded 103 records, leaving 144 articles for full-text review. Following rigorous screening and evaluation, 56 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review.

Figure 1: Flowchart of included articles.

3.1 Factors Influencing Doctoral Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 45 studies were identified for analysis. In terms of geographical distribution, the literature spans Europe, North America, Asia, and the Nordic countries. Among them, the United States accounts for the largest share with 11 studies, followed by the United Kingdom (n = 5), China (n = 3), Spain (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), and India (n = 2), and Canada (n = 1), France (n = 1), and Norway (n = 1). This distribution highlights the cross-cultural relevance of doctoral students’ mental health and well-being as a global issue. Regarding methodological approaches, quantitative studies dominate the field (n = 26), while qualitative designs (n = 14) and mixed-methods studies (n = 5) are less common. In terms of measurement dimensions, research on mental health has primarily focused on anxiety, depression, stress, and burnout, whereas studies on well-being have examined life satisfaction, supervision quality satisfaction, sense of belonging, and loneliness. Overall, the literature remains weighted toward psychological distress, with relatively limited empirical evidence on well-being (see Table 1).

Table 1: Factors influencing doctoral students’ mental health and well-being.

| Authors and Year | Method | Sample Size | Age (Mean) | Dimensions Involved | Factors | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stubb et al (2011) [21] | Mixed methods | Total: 669 Male: 168 Female: 496 Other: 5 | 39 | socio-psychological well-being, stress, exhaustion, anxiety, and study engagement | Academic community experience (divided into empowering experience and burden experience) | Finland |

| Moate et al. (2019) [22] | Quantitative research | Total: 528 Male: 167 Female: 358 Other: 3 | 30.5 | stress, life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions | Perfectionism types (divided into adaptive perfectionists, non-perfectionists, and maladaptive perfectionists) | United States |

| Sverdlik et al. (2023) [23] | Quantitative research | Total: 708 Male: 151 Female: 529 | 31.11 | Anxiety, depression, stress, satisfaction, and academic emotions (such as anxiety, irritability, enthusiasm, etc.) | COVID-19 pandemic (such as challenges and coping strategies like inability to meet family and friends, staying at home, blurred work-family time, etc.), gender | Multiple countries |

| Espiritu et al. (2021) [24] | Qualitative research | Total: 1 Female: 1 | 32 | Health, wellness, well-being | Active choices, support network, self-cognition, desire to fulfill roles, time management strategies | United States |

| Krieger et al. (2025) [25] | Quantitative research | Total: 1265 Male: 414 Female: 739 Other: 112 | 32.36 | Anxiety, depression, life satisfaction, and perception of supervision | Gender, doctoral discipline field, anxiety and depression symptoms, and supervision quality | Spain |

| Martínez et al. (2025) [26] | Qualitative research | Total: 10 Male: 2 Female: 8 | / | Stress, well-being | overwhelming responsibility, lack of self-confidence, uncertainty about various aspects of the doctoral process, and challenges related to family obligations and maternity, support of Supervisors and research groups | Norway |

| Feizi et al. (2024) [27] | Quantitative research | Total: 2486 Male: 899 Female: 1512 Other: 64 | 31 | Perceived stress, emotional, social, and psychological well-being, as well as program satisfaction and intention to quit | Perceived stress, academic factors (dissertation requirements, program structure), personal factors (workload, time pressure), demographic variables (gender, international student status) | Canada |

| Tiet et al. (2025) [28] | Quantitative research | Total: 889 Male: 140 Female: 710 Other: 37 | 27.63 | Depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, quality of life, physical pain, coping strategies, resilient coping, and social support. | COVID-19 stress, protective factors (problem-focused engagement coping, resilient coping, social support, aerobic/strength/flexibility activities), demographic variables (gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, relationship status) | United States |

| Geary et al. (2023) [29] | Quantitative research | Total: 113 Male: 15 Female: 96 | 27 | Self-care frequency, self-compassion, satisfaction with life, perceived stress, positive/negative affect | COVID-19 pandemic context, demographic variables (race/ethnicity: Black/African American students reported higher stress), social desirability | United States |

| Syropoulos et al. (2021) [30] | Mixed methods | Total: 916 Male: 193 Female: 701 Other: 13 | 27.73 | Social belonging, threat, challenge, depression, stress, satisfaction with life, subjective happiness, optimism | COVID-19 pandemic, demographic variables (race: White students higher belonging; sexual orientation: heterosexual lower threat; gender: women/trans/non-binary higher threat/lower challenge) | United States |

| Satici et al. (2025) [31] | Quantitative research | Total: 405 Male: 146 Female: 259 | 30.39 | Resilience, intolerance of uncertainty, future anxiety, mental well-being | Resilience (direct and indirect effect), intolerance of uncertainty (mediator), future anxiety (mediator), demographic variables (socio-economic status, PhD stage, role, field of study, marital status, number of children, psychological help/receipt of diagnosis) | Türkiye |

| Paucsik et al. (2022) [32] | Quantitative research | Total: 134 Male: 41 Female: 93 Other: 0 | 27.8 | Depression, anxiety, stress, well-being, doctoral engagement, self-compassion, savouring | COVID-19 pandemic (lockdowns), self-compassion (protective factor), savouring (protective factor, including anticipatory/reminiscent/present-oriented subtypes), age (moderator for well-being) | France |

| Zhang et al. (2022) [33] | Mixed methods | Total: 206 Male: 82 Female: 123 Other: 1 | / | Mental well-being (purposeful life, supportive social relationships, daily engagement, contribution to others’ well-being, competence, moral self-perception, optimism, respect), research self-efficacy, research skills | Socialization variables (Year 2: satisfaction with advisor; Year 3: certainty of choice; Year 4: academic development, sense of belonging to lab), academic outcomes (number of publications, research skills), demographic variables (gender, first-generation status, racially minoritized status, international status) | United States |

| Kismihók et al. (2022) [34] | Qualitative research | Total: 250 | / | Well-being, mental health, career sustainability, stigma, work engagement | Systemic (policy, funding, legal frameworks), institutional (research culture, working conditions, evaluation systems), individual (peer relationships, supervision quality, self-care, career planning), transversal skills (time/project management, communication, mental health literacy) | Germany, Ireland, The Netherlands |

| Hazell et al. (2025) [35] | Qualitative research | Total: 1783 Male: 550 Female: 1207 Other: 26 | 31.21 | Mental health (depression, anxiety, suicidality), well-being, self-worth, professional identity, supervisory relationship quality | Supervision as a “conduit” (shapes PhD/academia belonging, self-actualization, autonomy development), supervision as a “mirror” (reflects self-worth, role violations cause distress), mental health status (impacts supervision engagement), supervisor’s understanding of mental distress (validation, signposting) | United Kingdom |

| Prendergast et al. (2023) [36] | Qualitative | Total: 10 | / | Well-being (mental well-being, including feeling good and functioning well), stress, guilt, anxiety, and imposter syndrome | Doctoral study-related (e.g., workload, responsibilities, pandemic-related delays), family roles, social life, financial difficulties, relationships with supervisors and peers | Ireland |

| Zeeman et al. (2025) [37] | Qualitative research | Total: 6 | / | Well-being, burnout | Curriculum and research (e.g., program design, milestones, cumulative exams), relationships (peer, supervisor, dissertation committee), financial burden, work-life balance | United States |

| McCray et al. (2021) [38] | Quantitative research | Total: 63 Male: 29 Female: 34 | / | Mental well-being, positive and negative mental well-being factors | Personal factors (e.g., self-doubt, isolation), interpersonal factors (e.g., relationships with supervisor, family), business school environment (e.g., competition, individualism), support from different sources | United Kingdom |

| Corvino et al. (2022) [39] | Quantitative research | Total: 121 Male: 51 Female: 70 | 30.5 | Organizational well-being, discrimination, fairness, sense of belonging, goal sharing | Gender, university location, perception of workplace health and safety, career development opportunities, job autonomy, discrimination, and fairness | Italy |

| Tikkanen et al. (2024) [40] | Quantitative research | Total: 768 Male: 234 Female:502 | 30–34 | Burnout (exhaustion, cynicism), work engagement | Supervisory experience, frequency of supervision, perceptions of supervisory support and interaction, length of supervisory experience, supervisory workload | Finland |

| Vilser et al. (2024) [41] | Quantitative research | Total: 1275 | 30.44 | Well-being (measured through perceived stress and work engagement), overcommitment, and resilience | Effort-reward imbalance (effort, reward, ERI ratio), overcommitment, resilience, gender, age, type of promotion, impact, and fear of COVID-19 | Germany |

| Kunz-Skrede et al. (2025) [42] | Qualitative research | Total: 10 Male: 6 Female: 4 | / | Well-being, social belonging, social support | Social activities (cooking and social eating, self-care workshops), social capital (social belonging, social support), relationships (with peers, supervisors) | Norway |

| Tikkanen et al. (2021) [43] | Quantitative research | Total: 692 Male: 253 Female: 424 | 35 | Well-being (study engagement, burnout), drop-out intentions | Gender, country of origin, study status (full-time or part-time), research group status, working in a clinical unit or hospital | Sweden |

| Xu et al. (2024) [44] | Qualitative research | Total: 18 Male: 6 Female: 12 | 28.9 | Well-being (emotional well-being, social well-being, psychological well-being) | Individual factors (gender, age, personality, coping strategies, motivation, self-beliefs), microsystem (relationships with family, peers, supervisors), mesosystem (interrelations between different microsystems), exosystem (university hard and soft infrastructure), macrosystem (COVID-19, living and cultural environment), chronosystem | China |

| Gonzalez et al. (2021) [45] | Quantitative research | Total: 479 | 27.06 | Well-being (physical health, mental health), disciplinary identity, stress, and psychological needs satisfaction | Stress, psychological needs satisfaction (autonomy, relatedness, competence), socio-demographics (gender, age, URM, SES), anticipatory socialization experiences, prior academic credentials (GRE scores, undergraduate GPA, undergraduate institution ranking) | United States |

| Dutta et al. (2022) [46] | Quantitative research | Total: 778 | / | Mental well-being (measured by WEMWBS score), loneliness, anxiety, and distress | Social connection, loneliness, anxiety, student status, impact of lockdown on social contact, change in relationship with university, impact on finances, caregiving responsibilities, impact of caregiving on work, impact on work, impact on research tools, university support, supervisor support, everyday stressors | United Kingdom |

| Pyhältö et al. (2023) [47] | Quantitative research | Total: 884 Male: 345 Female: 539 | 37 | Study engagement, study burnout, and satisfaction with study | Country of origin, gender, dissertation format, research group status, study status, drop-out intentions, time-to-candidacy | Finland, South Africa |

| Zhang et al. (2024) [48] | Quantitative research | Total: 643 | 29.18 | Academic stress, academic motivation, emotional intelligence, mindfulness | Academic motivation, emotional intelligence, mindfulness, age, and gender | Pakistan |

| Friedrich et al. (2023) [49] | Mixed-methods | Total: 589 | 28.8 | General health (depression, anxiety), job satisfaction, life satisfaction, job insecurity, perceived stress | Workload, self-perception, job insecurity, social integration, supervision quality, COVID-19 impact | Germany |

| Acharya et al. (2024) [50] | Quantitative research | Total: 391 Male: 185 Female: 206 | / | Psychological well-being, job strain, and intrinsic motivation | Doctoral program demands, job strain, intrinsic motivation, and gender | India |

| Devonport et al. (2014) [51] | Qualitative research | Total: 4 Male: 2 Female: 2 | 26–27 | Stress, well-being, and coping effectiveness | Doctoral stressors (time pressure, financial stress, uncertainty, conceptual confusion, competing commitments), dyadic coping (emotional support, practical support, collaboration), individual coping (planning), relationship stress, and career ambiguity | United Kingdom |

| Tommasi et al., (2022) [52] | Quantitative research | Total: 204 Male: 76 Female: 128 | 29 | Meaningful work, meaningless work, anxiety, depression, intention to quit | Neoliberal academic environment (individualism, instrumentality, competition), PhD support (financial, social), features of meaningful work (coherence, significance, purpose, belonging), managerial practices | Italy |

| Almasri et al. (2022) [53] | Quantitative research | Total: 308 Male: 166 Female: 139 | / | Mental well-being, depression, anxiety, guilt, loneliness, and physical health | Conflicting cultural values (traditional gender roles, child-rearing expectations), lack of familial support, time pressure, missing professional/personal opportunities, limited childcare, healthcare access barriers, marital conflict, social isolation, immigration policies | United States |

| Estupiñá et al. (2024) [54] | Quantitative research | Total: 1018 Male: 365 Female: 645 Other: 8 | 31.7 | Psychological distress, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, life satisfaction, emotion regulation difficulties, work-family conflict | Gender (being female), years in doctoral program, life satisfaction, emotion regulation, fear of losing tuition rights, social support, work-to-personal-life conflict, regret about doctoral studies, desire to change supervisor | Spain |

| Koo et al. (2022) [55] | Qualitative research | Total: 7 Female: 7 | 28–41 | Mental well-being, depression, anxiety, guilt, loneliness, and physical health | Ongoing battles to manage both academic progress and mothering, constant conflict with their spouses, feelings of guilt, thoughts of dropping out, and concerns about their children. | United States |

| Cornwall et al. (2019) [56] | Qualitative research | Total: 152 | / | Stress, sense of belonging, social isolation, and well-being | Time pressure, uncertainty (doctoral processes, future workload), financial pressure, social isolation, sense of belonging, supervision issues (supervisor departure, availability, conflict) | New Zealand |

| Cardilini et al. (2022) [57] | Quantitative research | Total: 114 Male: 46 Female: 65 Other: 1 | / | Mental well-being, academic performance, supervision quality satisfaction | Supervisory expectations mismatch, academic anxiety, personal expectations, research progress, supervisor support, student engagement | Australia |

| Yan et al. (2024) [58] | Quantitative research | Total: 213 Male: 84 Female: 129 | / | academic performance, academic anxiety, well-being, self-efficacy | Teacher support, parental support, time management skills, facilitating conditions, student engagement, self-efficacy (task confidence), and academic anxiety | China |

| Hoque et al. (2024) [59] | Quantitative research | Total: 42 | / | Psychological well-being (positive emotion), autonomy, competence, relatedness | Autonomy (task control), competence (study demand management), relatedness (social connection with peers/family), and remote learning challenges during COVID-19 | South Africa |

| Mavrogalou-Foti et al. (2024) [60] | Quantitative research | Total: 141 Male: 39 Female: 97 Other: 5 | / | Depression, anxiety, stress, and supervisory relationship satisfaction | Supervisory styles, discrepancy between actual and preferred supervision, post-COVID-19 mental health exacerbation, research group participation, and funding status | United Kingdom |

| Wang et al. (2019) [61] | Qualitative research | Total: 10 Male: 5 Female: 5 | / | Stress, anxiety, academic frustration, and relationship tension | Graduation pressure, job prospects, relationship issues (supervisor abuse of power, family/marriage concerns, roommate conflicts), financial hardship (limited funding vs. peer wealth), personal factors (perfectionism, career regret) | China |

| Parveen et al. (2025) [62] | Qualitative research | Total: 40 Male: 28 Female: 12 | / | Mental health (stress, anxiety, burnout), research engagement, and well-being | Supervisory factors (inadequate mentorship, unprofessional behavior, exploitation as unpaid labor). Institutional factors (prolonged evaluations, inefficient resource access, rigid policies), social factors (limited peer collaboration, competitive dynamics), financial instability, and health impacts | India |

| Kusurkar et al. (2022) [63] | Qualitative research | Total:386 | / | Stress, energization, burnout, well-being, autonomy, competence, relatedness | Research challenges (excessive paperwork, high publication pressure, complicated lab work vs. engaging topics/analysis), resources, recognition (positive feedback, publications vs. lack of acknowledgment) | The Netherlands |

| Deroncele-Acosta et al. (2025) [64] | Mixed-methods | Total: 108 Female: 108 | / | Mental health (hope, optimism, resilience, self-efficacy), academic motivation (intrinsic/extrinsic), university academic performance, and well-being | Psychological capital (self-efficacy as a protective factor), academic motivation, study cycle, social support (family/friends/peers), hidden factors (family roles, marriage, employment, cultural norms) | Peru |

| Evans et al. (2021) [65] | Quantitative research | Total: 297 Male: 46 Female: 238 Other: 13 | / | Work-related burnout, anxiety, depression, emotional connection, childcare access (for parents), dropout ideation | Protective Factors, Emotional connection to loved ones, Parenthood, Racial minority status (Black/Asian students), Risk Factors, Sexual minority (SM) status, Reduced childcare access (for parents) | United States |

The determinants of doctoral students’ mental health and well-being span multiple levels, including individual psychological traits and behavioral choices, academic processes and supervisory relationships, interpersonal support systems, organizational and institutional contexts, and group-based differences. These factors intersect to shape doctoral students’ psychological experiences and overall quality of life. Synthesizing this evidence not only clarifies the mechanisms underlying doctoral students’ psychological risks but also informs the development of multi-level support and intervention strategies. The following sections summarize the literature across four major domains.

3.1.1 Individual-Level Factors

Doctoral students’ individual psychological characteristics are a key source of variation in their mental health and well-being. Research has shown that traits such as perfectionism, resilience, future anxiety, and intolerance of uncertainty significantly influence their adaptive capacity. Adaptive perfectionism and higher levels of resilience help alleviate stress and enhance life satisfaction, whereas maladaptive perfectionism and heightened future anxiety are associated with increased psychological distress [22,31]. In addition, positive psychological resources—such as psychological capital (hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience), emotional intelligence, and mindfulness—have been shown to reduce academic stress and enhance psychological adaptability [48,54,64].

Beyond psychological traits, everyday behavioral practices also play a crucial role in shaping doctoral students’ mental health. Practices such as self-care, self-compassion, regular physical exercise, and healthy lifestyle habits have been linked to improved quality of life and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression [29,31]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these positive behaviors were especially emphasized as key resources for mitigating burnout and feelings of isolation [28]. Moreover, in the context of multiple roles and responsibilities, effective time management and structured daily routines have been shown to help students cope with stress and maintain a sense of well-being [36].

Supervisors are among the most critical sources of psychological and academic support for doctoral students. The supervisory relationship is widely regarded as one of the most decisive elements in doctoral education [3], and its effectiveness largely depends on the clarity of guidance and the quality of communication between the student and the supervisor. When supervision is unclear or when there are mismatched expectations regarding role division, research goals, or publication outcomes, doctoral students are more likely to experience elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [40,57,61]. In contrast, high-quality and supportive supervision has been associated with greater life satisfaction and reduced psychological distress [24,58]. Moreover, a supervisor’s communication style and availability not only influence academic progress but also shape how students understand and manage their own psychological states [35].

Doctoral students are typically subject to intense academic demands, contributing to persistently high stress levels. While academic environments can promote meaningful engagement, they are also frequent sources of anxiety and exhaustion [66]. Key stressors include working conditions, job insecurity, and the pressures and uncertainties associated with dissertation writing, all of which have been linked to psychological distress [26]. Structural factors—such as heavy coursework, bureaucratic procedures, limited resources, and unpaid labor—further increase the risk of burnout [31,56,62]. A lack of control over academic progress has been found to correlate with reduced pro-gram satisfaction and increased dropout intentions [29,33]. The effort–reward imbalance (ERI) model helps explain these outcomes: high personal investment coupled with limited recognition or compensation significantly amplifies psychological stress among doctoral students [41].

3.1.3 Interpersonal-Level Factors

Support and a sense of belonging within the academic community are widely recognized as core contributors to doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. A strong sense of social belonging is associated with lower threat perception, better psychological functioning, and greater optimism about the future [29]. Conversely, a lack of belonging can lead to feelings of isolation and detachment, significantly increasing the risk of anxiety, depression, and dropout intentions [45]. Peer relation-ships play a critical role in this context. Collaborative and supportive peer environments can help reduce stress levels and enhance academic engagement, whereas competitive or exclusionary peer dynamics are closely linked to heightened psychological distress [47,62]. Furthermore, participation in academic social activities—such as seminars, writing groups, and informal gatherings—can strengthen social capital, alleviate loneliness, and foster opportunities for communication and collaboration, thereby indirectly promoting well-being and academic productivity [42].

Outside of academic settings, doctoral students also rely on broader social support networks, including family and partners, for emotional stability. Research has shown that dyadic coping strategies involving a partner can effectively alleviate academic stress, reduce negative emotional responses, and enhance psychological resilience [51]. For specific groups such as international doctoral mothers, partner and family support is especially vital in balancing academic responsibilities with caregiving demands. In the absence of such support, these students are more likely to experience emotional distress, guilt, and even consider program withdrawal [55]. Broader social networks have consistently been identified as protective factors. Students with higher levels of perceived social support report better quality of life and fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression [26]. During times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the combination of social support, resilience, and adaptive coping strategies has been shown to significantly improve doctoral students’ psychological functioning by mitigating stress, reducing emotional suffering, and enhancing life satisfaction [28].

3.1.4 Organizational and Environmental-Level Factors

Organizational support plays a critical role in doctoral students’ psychological well-being. When students perceive a lack of meaning in their research or insufficient institutional support, they are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and intentions to withdraw from their programs [52]. Instrumental management styles may undermine students’ autonomy and academic identity, con-tributing to psychological distress and uncertainty about the future. Research also indicates that in some disciplines, the institutional environment is psychologically inadequate—over-relying on the supervisor as a single point of support while lacking diversified and formalized support systems—leaving students more vulnerable to mental health risks [38]. Additionally, gender equality studies have revealed systemic disparities: female doctoral students report significantly lower scores in career development, autonomy, and perceived safety compared to their male counterparts. These gaps not only reflect unequal resource distribution but also indicate that institutional and cultural biases may impose additional psychological burdens [39].

Resources and policy conditions. Financial stress and the instability of funding policies are significant determinants of doctoral students’ mental health. Insufficient economic support has been shown to intensify symptoms of anxiety and depression, reduce life satisfaction, and increase the likelihood of program attrition [54,56,62]. These issues are particularly pronounced during the early stages of doctoral training and among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, who are more reliant on scholarships or external funding. In such cases, resource uncertainty places an even heavier psychological toll. The structure and reliability of funding systems at the policy level directly influence students’ ability to balance academic demands with financial and personal well-being.

External environmental disruptions. Doctoral students’ mental health is also shaped by broader sociopolitical contexts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous studies documented significant increases in anxiety, depression, stress, feelings of isolation, and uncertainty among this population [3,23,46]. The pandemic disrupted access to laboratories and campus facilities and blurred the boundaries between work and personal life, compounding psychological distress [59]. Similarly, sociopolitical unrest and macro-level instability can heighten mental health risks by restricting aca-demic activities, altering social atmospheres, and undermining career outlooks.

3.2 Group Differences in Doctoral Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

3.2.1 Gender and Identity Differences

Gender is among the most prominent factors underlying disparities in doctoral students’ mental health. Numerous studies have shown that female doctoral candidates face higher risks of anxiety and depression, and report disadvantages in organizational well-being indicators such as career development, autonomy, and perceived safety [25,39]. In addition, minority and LGBTQ+ doctoral students are more likely to report negative psychological experiences, suggesting that discrimination or lack of inclusivity in academic environments may constitute additional stressors [30]. For doctoral students who simultaneously bear maternal and international identities, conflicts between academic and family responsibilities are particularly pronounced, often accompanied by guilt, emotional distress, and heightened dropout intentions [54]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the psychological vulnerabilities of marginalized groups stem not only from academic pressures but also from their social identities and cultural contexts.

3.2.2 Disciplinary and Study-Stage Differences

Doctoral students’ mental health also varies significantly across disciplines. Students in the humanities and arts report higher levels of anxiety and depression compared with those in other fields, whereas medical and STEM doctoral students more frequently exhibit differing patterns of burnout and academic engagement [25,41]. These disciplinary variations may reflect differences in the nature of research work, clarity of career pathways, and availability of academic resources.

Study stage likewise shapes trajectories of mental health. Longitudinal research indicates that doctoral students’ psychological health tends to decline overall during the first years of enrollment, though individual trajectories differ markedly: some students maintain stability or even show improvement, while others experience persistent deterioration [45]. Stress levels and the extent to which basic psychological needs are met have been identified as critical predictors distinguishing these trajectories. This suggests that doctoral students’ mental health does not follow a linear course, but rather is co-determined by academic progress, need satisfaction, and resource availability.

3.2.3 Institutional Differences

Cross-national comparative studies emphasize that national and institutional contexts substantially alter the risk and protective mechanisms shaping doctoral mental health. In countries with more comprehensive funding systems and social security, doctoral students generally report lower levels of psychological distress; by contrast, in environments where funding is insufficient or institutional support is weak, stress and dropout intentions are far more prevalent [38,44,47]. Moreover, academic cultural differences also shape psychological experiences. For instance, institutional contexts that rely excessively on supervisors while lacking institutionalized mental health support channels render doctoral students more vulnerable to the adverse effects of poor supervisory relationships [38]. These cross-cultural findings underscore that doctoral students’ mental health cannot be addressed solely through individual- or interpersonal-level interventions; rather, institutional and policy design must account for cultural and contextual variations.

3.3 Interventions for Doctoral Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

With the growing recognition of mental health concerns among doctoral students, both academia and practice have increasingly explored diverse intervention strategies aimed at alleviating elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, while enhancing overall well-being. This review identified and analyzed 11 empirical studies focusing on interventions targeting doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Geographically, most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 3), followed by the United Kingdom (n = 2), with the Netherlands, Spain, Canada, and France each contributing one study. Methodologically, the body of literature is diverse, encompassing randomized controlled trials (RCTs), mixed-methods research, qualitative interviews, and experimental designs. However, most interventions were tested in small-scale, short-duration studies. Despite these limitations, existing research suggests that interventions can be broadly categorized into three groups: psychology-based training (e.g., mindfulness, positive psychology, and self-compassion), practice-oriented behavioral and learning interventions (e.g., behavioral activation, structured writing retreats, and progress-oriented workshops), and relationship- and support-based approaches (e.g., peer support, reflective practice, and online group learning). These initiatives have enriched the repertoire of doctoral student support strategies and offer valuable insights for institutional policies and practices (see Table 2).

Table 2: Interventions for doctoral students’ mental health and well-being.

| Authors, Year, and Country | Method | Sample Size | Dimensions Involved | Interventions | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newlands et al. (2025) [66], United Kingdom | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews, thematic analysis) | Total:19 Male:6 Female:13 | Resilience, social connection, isolation, help-seeking barriers | Peer support (informal experience sharing, key-stage guidance, mixed-format interactions) | Peer support can serve as an effective complement to existing mental health services. |

| Fang et al. (2021) [67], United States | Quantitative (RCT, pre-test/post-test, 1-week follow-up) | Total:66 | Burnout, well-being | Two brief phone-based behavioral interventions: 1) “Reward” (increase pleasant behaviors); 2) “Approach” (tackle avoided goals); 3) Control (monitoring only) | “Approach” group had significantly lower burnout and higher well-being vs. control (immediately post-intervention and follow-up). |

| Barry et al. (2019) [68], United States | Quantitative (single-blinded RCT, intention-to-treat analysis) | Total: 72 (34 intervention; 38 control) | Psychological distress and psychological capital (hope, optimism, resilience, and efficacy) | Daily guided mindfulness practice (audio CD, self-administered) | Intervention group showed significant reduction in depression and increases in self-efficacy, hope, and resilience vs. control. |

| Marais et al. (2018) [69], French | Mixed quantitative design:1) Cross-sectional survey2) Quasi-experimental pre–post intervention study (with a control group) | Study 1: N = 136 Study 2: Small intervention and control groups | Psychological distress: stress, depression, anxiety, subjective mental well-being | CARE positive psychology intervention (Positive Psychology Intervention):– Group-based intervention for PhD students– Aimed at strengthening psychological resources, emotion regulation, and well-being– Control group received no intervention | Study 1 (Survey): High levels of stress, depression, and anxiety; overall well-being was below benchmark levels; career uncertainty and work–life balance were major drivers of well-being. Study 2 (Intervention): Anxiety decreased significantly after the intervention; other outcomes improved slightly but were not statistically significant. |

| Vincent et al. (2023) [70], Canada | Explanatory sequential mixed method with experimental design | Total: 100 Male: 24 Female: 75 Non-binary: 1 | Psychological distress, psychological well-being, emotional well-being, social well-being | 3-day retreat with lodging, structured activities, and meals; included workshops, writing sessions, recharging activities, and socializing; guided by two facilitators who taught time management and goal-setting techniques | Writing retreats reduced doctoral researchers’ psychological distress and improved their psychological, emotional, and social well-being. |

| Jiménez et al. (2024) [71], Spain | Non-randomized controlled study with repeated measures pre-post design | Total: 97 Male: 34 Female: 60 Other: 3 | Well-being (satisfaction with life, positive and negative affect), psychological distress (anxiety, depression, emotional profiles) | The Third Half program: six 3-h sessions held bi-weekly. Each session had two blocks—one with gamified outdoor activities based on positive psychology and the other for peer support through social interactions. | The program was effective in improving some well-being indicators and reducing distress. |

| Tullet et al. (2024) [72], United Kingdom | Pilot study with pre- and post-online surveys, analysis of transcribed recordings, and reflective notes | Total: 8 Male: 4 Female: 4 | Stress & pressure; imposter syndrome; student-supervisor relationship; trust & transparency; and reflexivity | 6-month online Reflexivity in Research program for second-year PhD students. It encouraged reflection on professional identity and interpersonal relationships through creative and reflective approaches. | Program helped students gain perspective, become more resilient, and better manage emotions. Positive feedback from students, supervisors, and management board members supported the program’s success. |

| Solms et al. (2025) [73], The Netherlands | Quantitative (RCT); pre-test, post-test, 3-month follow-up) | Total: 115 | Psychological capital (PsyCap: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, optimism), self-compassion, positive affect, work pressure, support seeking | 1. Self-compassion-based PsyCap intervention: 5-week online program—integrates self-compassion training with PsyCap exercises. 2. PsyCap-only intervention: Focused solely on PsyCap (HERO components) without self-compassion. 3. Wait-list control group | The findings suggest that although fostering PsyCap together with self-compassion may take a longer time, it yields greater improvements in PhD students’ well-being compared with developing PsyCap alone. |

| Gao et al. (2025) [74], United States | Mixed-methods: Qualitative + Quantitative | Total: 4 Female: 4 | Awareness and attention, emotional intelligence and regulation, stress and anxiety levels, compassion levels | 8-week mindfulness program via Healthy Minds Program app: 10–15 min of daily audio-guided mindfulness lessons and meditations | Mindfulness practice serves as a valuable tool for doctoral students to manage project challenges and support their emotional well-being. |

| Prieto et al. (2022) [75], Spain; Estonia | Design-based research (4 iterations; mixed data) | Total: 82 | Psychological capital (PsyCap: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, optimism), burnout, perceived progress, dropout ideation | Progress-oriented workshops (iterative formats): Iter. 1: 2 h F2F—Goal setting, peer feedback; Iter. 2: 6 h F2F—Added mental health & journaling; Iter. 3: 6 h Online—Added thesis mapping, self-tracking (LAPills); Iter. 4: 8 h Online—Extended discussion, data visualization | The seminar has a positive impact on doctoral students’ positive psychological capital. |

| Areskoug (2024) [76], Sweden; Norway | Mixed-methods (Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles; data; thematic analysis) | Total: 28 | Academic skills, stress, self-efficacy, supervisor dependency, social connection, well-being, project progress | 1. Online monthly meetings: 8–9 a.m., 1-h sessions. 2. Online writing retreats: (20 total) | Doctoral students acquired higher academic and leadership skills, experienced reduced stress, enhanced self-efficacy, and decreased dependence on their advisors. |

3.3.1 Psychology-Based Training

This category of interventions draws directly on established psychological approaches to enhance doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Mindfulness interventions are among the most commonly applied, with studies demonstrating that daily mindfulness meditation and attention-focused practices effectively reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety while significantly improving psychological capital, including hope, resilience, and self-efficacy, thereby enhancing overall well-being [68,74]. The advantages of mindfulness lie in its high feasibility, low cost, and adaptability for online delivery. Positive psychology interventions have also shown promising outcomes. For example, the French CARE program reduced anxiety and improved well-being among doctoral students, while a Dutch self-compassion–based PsyCap intervention emphasized cultivating self-compassion to lower stress, enhance positive emotions, and sustain improvements in well-being over time [69,73]. In addition, multi-component psychoeducational programs, such as “The Third Half,” integrate stress management, emotion regulation, and health-promoting skills to provide doctoral students with a toolbox for self-care and coping. These programs have been found to significantly reduce negative emotions and psychological distress and demonstrate strong feasibility and scalability in practice [77]. Collectively, these interventions highlight the importance of strengthening psychological resources and equipping doctoral students with systematic frameworks for cognitive and emotional coping in high-pressure academic contexts.

3.3.2 Practice-Oriented Behavioral and Learning Interventions

A second category of interventions focuses on optimizing doctoral students’ daily study habits and behavioral routines to improve mental health and well-being. For instance, brief behavioral activation delivered via phone encouraged doctoral students to approach avoided but important goals and engage in rewarding activities, which significantly reduced burnout and enhanced well-being [67]. This flexible, remotely deliverable format makes it particularly suitable for institutions with limited resources. Structured writing retreats, including residential or online formats, have also proven effective in alleviating stress and improving psychological, emotional, and social well-being. Mechanisms underlying these effects include perceived gains in productivity and opportunities for socialization and networking, which emerged as key predictors of improved well-being [70]. Similarly, progress-oriented workshops that combine educational components, peer sharing, and self-monitoring of progress were shown to enhance students’ perceptions of academic advancement, reduce burnout and dropout intentions, and strengthen positive psychological capital and satisfaction with their programs [75]. Overall, such interventions work indirectly by improving doctoral students’ academic engagement and sense of progress, thereby mitigating psychological distress.

3.3.3 Relationship- and Support-Based Interventions

The third category emphasizes the role of social relationships and support networks in fostering doctoral students’ mental health. Evidence suggests that peer support is highly valued, providing flexible and informal spaces where students can alleviate loneliness, anxiety, and depression while exchanging experiences and practical advice [77]. These interventions are especially effective when peer groups are diverse and inclusive, accommodating the needs of students from different backgrounds. Reflective practice programs offer doctoral students structured opportunities to discuss challenges in supervisory relationships, academic pressures, and work–life balance in a safe environment, thereby strengthening self-awareness, coping strategies, and resilience [78]. Additionally, online group-based learning activities that gained prominence during the pandemic—such as virtual monthly meetings and writing retreats—were found to reduce isolation, enhance academic and leadership skills, alleviate stress, and improve self-efficacy, while reducing overreliance on supervisors [76]. By fostering greater connectivity and mutual support among doctoral students, these relationship-based interventions contribute to building more inclusive, secure, and supportive academic communities.

This review systematically synthesizes the complex and multilayered factors influencing doctoral students’ mental health and well-being across four key domains: individual, academic, interpersonal, and organizational–environmental levels. It also categorizes the major intervention strategies targeted at improving psychological outcomes in this population. Building on these findings, it is necessary to more clearly highlight gaps in the existing literature to inform future research directions and propose specific, actionable recommendations for universities.

In terms of influencing factors, two critical gaps remain underexplored: cross-cultural comparisons and intersectional analyses of vulnerable subgroups. First, although existing studies have documented differences in doctoral students’ mental health and well-being based on demographic variables, academic disciplines, stages of study, and institutional settings, cross-cultural and policy-oriented comparative research remains limited. Most empirical studies have been conducted in Western contexts, while only a small number have focused on countries such as China or India. These studies tend to rely on single-nation or region-specific samples, with few adopting comparative perspectives. However, substantial variation exists in doctoral training models, academic cultures, funding structures, and mental health support systems across countries and institutional contexts. These systemic and cultural differences may exert heterogeneous effects on student psychological outcomes [38,44,47]. Future research should therefore undertake in-depth cross-cultural and cross-system comparative studies to examine how structural variations shape doctoral students’ mental health and well-being. Second, the differentiated psychological experiences of vulnerable populations within the doctoral student body require closer attention. Existing evidence indicates that female doctoral students are more prone to anxiety and depression, and students from ethnic minorities and LGBTQ+ groups frequently report negative psychological outcomes [33,60]. Moreover, intersecting identities—such as motherhood and international student status—introduce additional stressors and responsibilities that may heighten vulnerability to psychological distress. Future research should incorporate intersectional frameworks to examine how gender, ethnicity, caregiving roles, and institutional settings interact, identify which groups face the highest risks at specific academic stages, and propose tailored support mechanisms. Such analyses would not only advance understanding of risk stratification but also inform inclusive and equity-oriented policy development in higher education.

With regard to intervention strategies, although current research has demonstrated the effectiveness of approaches such as mindfulness training, writing retreats, and peer support in improving doctoral students’ mental health and well-being, there remains a lack of large-scale and longitudinal empirical validation [6,78,79,80]. Most existing interventions are characterized by short durations, small sample sizes, and voluntary participation, which limits their generalizability and scalability. Future studies should implement RCTs with larger, more diverse samples and incorporate extended follow-up periods to evaluate the comparative effectiveness and underlying mechanisms of different interventions across contexts [68]. In parallel, universities must take a more proactive role in promoting the psychological well-being of doctoral students. First, doctoral training programs should place greater emphasis on practical courses rooted in positive psychology. Integrating modules on emotion regulation, self-compassion, and mindfulness meditation into the formal curriculum may enhance students’ psychological resilience and their ability to cope with stress. Second, institutions should leverage artificial intelligence and big data technologies [81] to identify high-risk subpopulations and develop targeted, behavior- and learning-based interventions (e.g., structured writing retreats, time management coaching). Third, given that doctoral supervisors serve as critical sources of both academic and emotional support, universities should establish systematic mechanisms for assessing and improving supervision quality. This may include regular feedback sessions to explore supervisory style and communication patterns, evaluations of supervisor–student relationships, and early conflict resolution procedures to prevent the escalation of tensions.

Nevertheless, certain limitations remain. Despite following rigorous systematic review protocols, the number of included studies is constrained, especially with regard to intervention research, where existing evidence is largely limited to small-scale, short-term trials, lacking large-sample RCTs and long-term follow-up. Methodologically, many studies rely on cross-sectional data, limiting causal inference, while longitudinal and mechanism-focused analyses are relatively scarce. Additionally, heterogeneity across studies—in measurement tools, conceptual definitions, and analytical frameworks—complicates integration and comparison. Finally, this review excluded gray literature and unpublished studies, which may introduce publication bias.

Doctoral students’ mental health and well-being are not only central to their academic development and quality of life but also directly shape research productivity and the sustainability of higher education systems. This study is among the few systematic reviews to comprehensively synthesize research on doctoral students’ mental health and well-being, addressing both influencing factors and intervention strategies. It adopts a broad scope, including large-scale quantitative studies as well as qualitative and mixed-method research, and incorporates literature from diverse regions, including Europe, North America, and Asia, thereby reflecting both the universality and specificity of doctoral students’ psychological challenges in cross-cultural contexts. Moreover, this review systematically categorizes influencing factors across four dimensions: individual psychological traits and behaviors, academic processes and supervisory relationships, interpersonal support systems, and organizational and environmental conditions. It further highlights group-level differences related to gender, identity, discipline, stage of study, and institutional settings. In terms of interventions, it synthesizes three primary approaches: psychology-based training, practice-oriented behavioral interventions, and relationship- and support-based strategies. This multi-level, multidimensional integration enriches theoretical understanding and offers valuable insights for developing targeted support and intervention programs in practice.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and design: Yuxin Guo and Xinqiao Liu; literature search and screening: Yuxin Guo and Xinqiao Liu; writing original draft and review: Yuxin Guo and Xinqiao Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.074063/s1.

References

1. Storti BC , Sinval J , Munro YL , Medina FJ , Sticca MG . Advisor-advisee relationship and the organizational culture of doctoral programs on doctoral students’ mental health and academic performance: a scoping review protocol. MethodsX. 2025; 15: 103433. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2025.103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Guo Y . Examining how supervisor–student relationship types influence depression in doctoral students: the role of mediating mechanisms. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2025; 2025: 6254499. doi:10.1155/cad/6254499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu X , Zhang X , Li Y . Why early career researchers escape the ivory tower: the role of environmental perception in career choices. Educ Sci. 2024; 14( 12): 1333. doi:10.3390/educsci14121333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Acharya V , Rajendran A , Shenoy S . A framework for doctoral education in developing students’ mental well-being by integrating the demand and resources of the program: an integrative review. F1000Research. 2023; 12: 431. doi:10.12688/f1000research.131766.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu X . Tears and cheers: a narrative inquiry of a doctoral student’s resilience in study abroad. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 1071674. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1071674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Satinsky EN , Kimura T , Kiang MV , Abebe R , Cunningham S , Lee H , et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Sci Rep. 2021; 11( 1): 14370. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93687-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pizuńska D , Golińska PB , Małek A , Radziwiłłowicz W . Well-being among PhD candidates. Psychiatr Pol. 2021; 55( 4): 901– 14. doi:10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao X , Liu X . Effect of depressive symptoms and learning difficulty on academic achievement among adolescents in China: a cross-lagged panel study. Int J Psychol. 2025; 60( 6): e70113. doi:10.1002/ijop.70113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liu X , Li Y , Gao W . Subjective well-being of college students: developmental trajectories, predictors, and risk for depression. J Psychol Afr. 2024; 34( 5): 477– 86. doi:10.1080/14330237.2024.2398871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bergvall S , Fernström C , Ranehill E , Sandberg A . The impact of PhD studies on mental health-a longitudinal population study. J Health Econ. 2025; 104: 103070. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2025.103070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. González-Betancor SM , Dorta-González P . Risk of interruption of doctoral studies and mental health in PhD students. Mathematics. 2020; 8( 10): 1695. doi:10.3390/math8101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mahsood N , Mahboob U , Asim M , Shaheen N . Assessing the well-being of PhD scholars: a scoping review. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 362. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02668-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu X , Zhang Y , Cao X . Achievement goal orientations in college students: longitudinal trajectories, related factors, and effects on academic performance. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2024; 39( 3): 2033– 55. doi:10.1007/s10212-023-00764-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. World Health Organization . World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

15. Martínez-García I , De Witte H , García-Martínez J , Cano-García FJ . A systematic review and a comprehensive approach to PhD students’ wellbeing. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2024; 16( 4): 1565– 83. doi:10.1111/aphw.12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mackie SA , Bates GW . Contribution of the doctoral education environment to PhD candidates’ mental health problems: a scoping review. High Educ Res Dev. 2019; 38( 3): 565– 78. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1556620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Schmidt M , Hansson E . Doctoral students’ well-being: a literature review. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2018; 13: 1508171. doi:10.1080/17482631.2018.1508171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chmitorz A , Kunzler A , Helmreich I , Tüscher O , Kalisch R , Kubiak T , et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience—a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018; 59: 78– 100. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Park EK , Sibalis A , Jamieson B . The mental health and well-being of master’s and doctoral psychology students at an urban Canadian university. Int J Dr Stud. 2021; 16: 429– 47. doi:10.28945/4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y , King RB , Chen J , Xu W . PhD students’ well-being and its antecedents and consequences: a perspective of the job demands-resources model. High Educ Res Dev. 2025: 1– 17. doi:10.1080/07294360.2025.2482204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Stubb J , Pyhältö K , Lonka K , Institutet K . Balancing between inspiration and exhaustion: PhD students’ experienced socio-psychological well-being. Stud Continuing Educ. 2011; 33( 1): 33– 50. doi:10.1080/0158037x.2010.515572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Moate RM , Gnilka PB , West EM , Rice KG . Doctoral student perfectionism and emotional well-being. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2019; 52( 3): 145– 55. doi:10.1080/07481756.2018.1547619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sverdlik A , Hall NC , Vallerand RJ . Doctoral students and COVID-19: exploring challenges, academic progress, and well-being. Educ Psychol. 2023; 43( 5): 545– 60. doi:10.1080/01443410.2022.2091749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Espiritu EW , Smith TM . Health, wellness, and well-being of a non-traditional occupational therapy student: a case study. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2021; 37( 1): 87– 103. doi:10.1080/0164212x.2020.1832942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Krieger V , Cañete-Massé C , Amador-Campos JA , Peró-Cebollero M , Feliu-Torruella M , Pérez-González A , et al. Mental health among Spanish doctoral students: relationship between anxiety, depression, life satisfaction, and mentoring. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2025; 15( 8): 164. doi:10.3390/ejihpe15080164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Martínez García I , García Martínez J , Javier Cano García F , De Witte H . Navigating stress, support and supervision: a qualitative study of doctoral student wellbeing in Norwegian academia. Int J Dr Stud. 2025; 20: 1. doi:10.28945/5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Feizi S , Knäuper B , Elgar F . Perceived stress and well-being in doctoral students: effects on program satisfaction and intention to quit. High Educ Res Dev. 2024; 43( 6): 1259– 76. doi:10.1080/07294360.2024.2317276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Tiet QQ , Brooks J . Protective factors for depression, anxiety, quality of life, and physical pain in psychology doctoral students during the COVID-19 pandemic onset. J Am Coll Health. 2025: 1– 9. doi:10.1080/07448481.2025.2530481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Geary MR , Shortway KM , Marks DR , Block-Lerner J . Psychology doctoral students’ self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic: relationships among satisfaction with life, stress levels, and self-compassion. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2023; 17( 4): 323– 30. doi:10.1037/tep0000444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Syropoulos S , Wu DJ , Burrows B , Mercado E . Psychology doctoral program experiences and student well-being, mental health, and optimism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 629205. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.629205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Satici SA , Kütük H , Okur S , Demirci İ , Deniz ME , Satici B , et al. Resilience, intolerance of uncertainty, future anxiety and mental well being among young researchers. Psychiatr Q. 2025: 1– 15. doi:10.1007/s11126-025-10192-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Paucsik M , Leys C , Marais G , Baeyens C , Shankland R . Self-compassion and savouring buffer the impact of the first year of the COVID-19 on PhD students’ mental health. Stress Health. 2022; 38( 5): 891– 901. doi:10.1002/smi.3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang F , Litson K , Feldon DF . Social predictors of doctoral student mental health and well-being. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 9): e0274273. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kismihók G , McCashin D , Mol ST , Cahill B . The well-being and mental health of doctoral candidates. Euro J Education. 2022; 57( 3): 410– 23. doi:10.1111/ejed.12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hazell CM , Berry C , Haywood D , Birkett J , MacKenzie JM , Niven J . Understanding how doctoral researchers perceive research supervision to impact their mental health and well-being. Couns And Psychother Res. 2025; 25: e12762. doi:10.1002/capr.12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Prendergast A , Usher R , Hunt E . “A constant juggling act”—the daily life experiences and well-being of doctoral students. Educ Sci. 2023; 13( 9): 916. doi:10.3390/educsci13090916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zeeman JM , Anderson EB , Matt IC , Jarstfer MB , Harris SC . Assessing factors that influence graduate student burnout in health professions education and identifying recommendations to support their well-being. PLoS One. 2025; 20( 4): e0319857. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0319857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. McCray J , Joseph-Richard P . Doctoral students’ well-being in United Kingdom business schools: a survey of personal experience and support mechanisms. Int J Manag Educ. 2021; 19( 2): 100490. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Corvino C , De Leo A , Parise M , Buscicchio G . Organizational well-being of Italian doctoral students: is academia sustainable when it comes to gender equality? Sustainability. 2022; 14( 11): 6425. doi:10.3390/su14116425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tikkanen L , Ketonen E , Toom A , Pyhältö K . PhD candidates’ and supervisors’ wellbeing and experiences of supervision. High Educ. 2025; 90( 5): 1451– 69. doi:10.1007/s10734-024-01385-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Vilser M , Gentele S , Mausz I . Putting PhD students front and center: an empirical analysis using the effort-reward imbalance model. Front Psychol. 2024; 14: 1298242. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1298242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kunz-Skrede EM , Molin M , Tokovska M . “So, we started to say hi to each other on campus.” A qualitative study about well-being among PhD candidates in Norway. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2025; 20( 1): 2474355. doi:10.1080/17482631.2025.2474355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tikkanen L , Pyhältö K , Bujacz A , Nieminen J . Study engagement and burnout of the PhD candidates in medicine: a person-centered approach. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 727746. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Xu W , Li Y , King RB , Chen J . The well-being of doctoral students in education: an ecological systems perspective. Behav Sci. 2024; 14( 10): 929. doi:10.3390/bs14100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gonzalez JA , Kim H , Flaster A . Transition points: well-being and disciplinary identity in the first years of doctoral studies. Stud Graduate Postdr Educ. 2021; 12( 1): 26– 41. doi:10.1108/sgpe-07-2020-0045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Dutta S , Roy A , Ghosh S . An observational study to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the factors affecting the mental well-being of doctoral students. Trends Psychol. 2022: 1– 16. doi:10.1007/s43076-022-00211-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Pyhältö K , Peltonen J , Anttila H , Frick LL , de Jager P . Engaged and/or burnt out? Finnish and South African doctoral students’ experiences. Stud Graduate Postdr Educ. 2023; 14( 1): 1– 18. doi:10.1108/sgpe-02-2021-0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang S , Rehman S , Zhao Y , Rehman E , Yaqoob B . Exploring the interplay of academic stress, motivation, emotional intelligence, and mindfulness in higher education: a longitudinal cross-lagged panel model approach. BMC Psychol. 2024; 12( 1): 732. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-02284-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Friedrich J , Bareis A , Bross M , Bürger Z , Cortés Rodríguez Á , Effenberger N , et al. “How is your thesis going?”—Ph.D. students’ perspectives on mental health and stress in academia. PLoS One. 2023; 18( 7): e0288103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0288103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Acharya V , Thomas Gil M , Acharya KA . Impact of intrinsic motivation on psychological well-being of doctoral students–a multivariate analysis. Int J Dr Stud. 2024; 19: 13. doi:10.28945/5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Devonport TJ , Lane AM . In it together: dyadic coping among doctoral students and partners. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2014; 15: 124– 34. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2014.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tommasi F , Toscano F , Giusino D , Ceschi A , Sartori R , Lisa Degen J . Meaningful or meaningless? Organizational conditions influencing doctoral students’ mental health and achievement. Int J Dr Stud. 2022; 17: 301– 21. doi:10.28945/5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Almasri N , Read B , Vandeweerdt C . Mental health and the PhD: insights and implications for political science. PS Polit Sci Polit. 2022; 55( 2): 347– 53. doi:10.1017/s1049096521001396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Estupiñá FJ , Santalla Á , Prieto-Vila M , Sanz A , Larroy C . Mental health in doctoral students: individual, academic, and organizational predictors. Psicothema. 2024; 36( 2): 123– 32. doi:10.7334/psicothema2023.156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Koo KK , Nyunt G . Mom, Asian international student, doctoral student, and in-between: exploring Asian international doctoral student mothers’ mental well-being. J Coll Stud Dev. 2022; 63( 4): 414– 31. doi:10.1353/csd.2022.0035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Cornwall J , Mayland EC , van der Meer J , Spronken-Smith RA , Tustin C , Blyth P . Stressors in early-stage doctoral students. Stud Continuing Educ. 2019; 41( 3): 363– 80. doi:10.1080/0158037x.2018.1534821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Cardilini APA , Risely A , Richardson MF . Supervising the PhD: identifying common mismatches in expectations between candidate and supervisor to improve research training outcomes. High Educ Res Dev. 2022; 41( 3): 613– 27. doi:10.1080/07294360.2021.1874887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Yan T , Yu H , Tang J . The influence of multiple factors on musicology doctoral students’ academic performance: an empirical study based in China. Behav Sci. 2024; 14( 11): 1073. doi:10.3390/bs14111073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Hoque M . The psychological well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown of doctoral students at a private higher education institution in South Africa: an application of Self-Determination Theory. S Afr N J High Educ. 2024; 38( 1): 217– 26. doi:10.20853/38-1-6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Mavrogalou-Foti AP , Kambouri MA , Çili S . The supervisory relationship as a predictor of mental health outcomes in doctoral students in the United Kingdom. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1437819. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1437819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang X , Wang C , Wang J . Towards the contributing factors for stress confronting Chinese PhD students. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019; 14( 1): 1598722. doi:10.1080/17482631.2019.1598722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Parveen S , Yasmeen J , Ajmal M , Qamar MT , Sohail SS , Madsen DØ . Unpacking the doctoral journey in India: supervision, social support, and institutional factors influencing mental health and research engagement. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2025; 11: 101282. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Kusurkar RA , Isik U , van der Burgt SME , Wouters A , Mak-van der Vossen M . What stressors and energizers do PhD students in medicine identify for their work: a qualitative inquiry. Med Teach. 2022; 44( 5): 559– 63. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.2015308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Deroncele-Acosta A , Norabuena-Figueroa RP , Norabuena-Figueroa ED . Women’s mental health in the doctoral context: protective function of the psychological capital and academic motivation. Womens Health. 2025; 21: 17455057251315318. doi:10.1177/17455057251315318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. E Evans K , R Holmes M , M Prince D , Groza V . Social work doctoral student well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study. Int J Dr Stud. 2021; 16: 569– 92. doi:10.28945/4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Newlands F , Markan T , Pomfret I , Davey E , King T , Roach A , et al. “A PhD is just going to somehow break you”: a qualitative study exploring the role of peer support for doctoral students. PLoS One. 2025; 20( 6): e0325726. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0325726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Fang CM , McMahon K , Miller ML , Rosenthal MZ . A pilot study investigating the efficacy of brief, phone-based, behavioral interventions for burnout in graduate students. J Clin Psychol. 2021; 77( 12): 2725– 45. doi:10.1002/jclp.23245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Barry KM , Woods M , Martin A , Stirling C , Warnecke E . A randomized controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on doctoral candidate psychological status. J Am Coll Health. 2019; 67( 4): 299– 307. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1515760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. AB Marais G , Shankland R , Haag P , Fiault R , Juniper B . A survey and a positive psychology intervention on French PhD student well-being. Int J Dr Stud. 2018; 13: 109– 38. doi:10.28945/3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Vincent C , Tremblay-Wragg É , Plante I . Effects of a participation in a structured writing retreat on doctoral mental health: an experimental and comprehensive study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20( 20): 6953. doi:10.3390/ijerph20206953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]