Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

An Overview and Comparative Study of Traditional, Chaos-Based and Machine Learning Approaches in Pseudorandom Number Generation

1 Department of Computer Science, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, 233, Ghana

2 Department of Medical Imaging, University for Development Studies, P.O. Box TL1350, Tamale, 233, Ghana

* Corresponding Author: Issah Zabsonre Alhassan. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 165-196. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.063529

Received 17 January 2025; Accepted 05 June 2025; Issue published 07 July 2025

Abstract

Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) are foundational to modern cryptography, yet existing approaches face critical trade-offs between cryptographic security, computational efficiency, and adaptability to emerging threats. Traditional PRNGs (e.g., Mersenne Twister, LCG) remain widely used in low-security applications despite vulnerabilities to predictability attacks, while machine learning (ML)-driven and chaos-based alternatives struggle to balance statistical robustness with practical deployability. This study systematically evaluates traditional, chaos-based, and ML-driven PRNGs to identify design principles for next-generation systems capable of meeting the demands of high-security environment like blockchain and IoT. Using a framework that quantifies cryptographic robustness (via NIST SP 800-22 compliance), computational efficiency (throughput in numbers/sec), and resilience to adversarial attacks, we compare various PRNG architectures. Results show that ML-based models (e.g., GANs, RL agents) achieve near-perfect statistical randomness (99% NIST compliance) but suffer from high computational costs (10³ numbers/sec) and vulnerabilities to model inversion. Chaos-based systems (e.g., Lorenz attractor) offer moderate security (97%–98% NIST scores) with faster generation rates (1.5–2 ms/number), while traditional PRNGs prioritize speed (106 numbers/sec) at the expense of cryptographic strength (70%–95% NIST pass rates). To address these limitations, we propose hybrid architectures integrating classical algorithms with lightweight ML components (e.g., TinyGANs), reducing training time by 40% while maintaining 98% NIST compliance. This work provides three key contributions. These include a quantitative security-speed trade-off analysis across PRNG paradigms, cryptanalytic insights into ML-PRNG vulnerabilities (e.g., overfitting to training data), and actionable guidelines for optimizing hybrid designs in resource-constrained settings. By bridging deterministic and stochastic methodologies, this study advances a roadmap for developing adaptable, attack-resistant PRNGs tailored for evolving cryptographic standards.Keywords

Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) serve as the backbone of modern computational systems, enabling critical functionalities in cryptography, Monte Carlo simulations, gaming, and secure communications [1]. Traditional PRNGs, such as Linear Congruential Generators (LCGs), Mersenne Twister (MT), and XORShift, rely on deterministic algorithms to produce sequences that approximate randomness. While these methods are computationally efficient, generating up to 106 numbers per second in resource-constrained environment, their inherent periodicity and predictability pose significant risks in cryptographic applications [2,3]. For instance, LCGs exhibit correlations in higher dimensions, and even MT, despite its long period of

Recent advancements in machine learning (ML) have introduced novel paradigms for PRNG design, leveraging architectures such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and chaotic neural networks [5,6]. Unlike traditional methods, ML-based PRNGs dynamically adapt to environmental inputs, achieving 99% NIST test pass rates and near-zero predictability [7]. For example, GANs trained on chaotic maps generate sequences that resist linear cryptanalysis, while RL models optimize entropy through iterative reward mechanisms [8,9]. However, these advancements come at a cost: ML-PRNGs demand substantial computational resources, with GANs producing only 10³ numbers per second, and face challenges such as overfitting and model inversion attacks [10].

This study addresses these gaps by conducting a systematic comparison of traditional and ML-based PRNGs, with a focus on cryptographic applications such as IoT, blockchain, and secure communications. The primary objectives are:

1. Analyze the security–speed trade-offs among traditional, chaos-based, and ML-driven PRNGs using metrics like NIST SP 800-22 compliance and throughput.

2. Identify vulnerabilities in ML-based PRNGs and their cryptographic implications.

3. Propose design guidelines for hybrid PRNGs by combining classical and ML components that are better suited for resource-constrained environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews traditional and ML-based PRNGs, including chaos-based methods. Section 3 presents a quantitative comparison using NIST tests and computational benchmarks. Section 4 discusses cryptanalysis, ethical implications, optimization strategies for low-resource environment and future research. Finally, Section 5 concludes with recommendations for future research, emphasizing hybrid models and explainable AI in PRNG design.

2 Pseudorandom Number Generators (PRNG)

Algorithms that are used to produce sequence of numbers that show properties of randomness but are not actually random, are termed as pseudorandom number generators. They usually require an initial parameter(s) to generate the sequence and can reproduce the exact same sequence once the exact same initial parameter(s) are provided [11]. Periodicity, randomness and determinism are the major properties of PRNGs, and they depend on the quality of the initial parameters called seeds.

2.1 Traditional PRNG Approaches

There have been several approaches to pseudorandom number generation before the introduction of Machine learning. These traditional PRNGs formed the basis of random number generation today.

2.1.1 Linear Congruential Generators (LCGs)

The Linear Congruential Generator (LCG) is undoubtedly one of the oldest PRNG’s [12]. LCG’s are generally define as:

A pseudorandom sequence is generated starting with an initial seed

Let us assume that we have a starting value of some length, say a 4-digit number from 0000 to 9999. If we wish to generate a 4-digit random number also, then we could square this initial 4-digit number to get a number of 8 digits in the form of abcd efgh. The next 4 digits of the random number could then be taken from its middle: ef, which we would use as a random number and as a new initial value for the next number. This method of random number generation is called the middle square method. The first and less significant half of every number does not change with time; likewise, since there are only 10,000 possible 4-digit numbers, this number will eventually be repeated, and what comes thereafter will also be repeated. So the middle square method is not a very good random number generation method, and if at all, it can be used only for an extremely small number of solutions as compared to large ones [15].

The Mersenne Twister is undoubtedly one of the most popular random number generators (RNGs) of today, with widespread use due to its longer period and faster generation. It was described in 1998. The name derives from the fact that its period is a Mersenne prime, which provides the following formula to generate a 32-bit random number [4].

MT is known for its extremely good dimensionality properties; it can pass extensive statistical tests. It has a period of

It is disappointing that the chosen code for illustration produces only 32-bit numbers, leading to calculations not relevant for cryptography, except when used in combination with other generators. The efficiency of each encoding can be compensated by the computational cost of the sequential generation to improve the efficiency of a truly cryptographic generator. To the knowledge of the present authors, the implementation details of the cryptographic version of known generators have not been made available to the general public, despite claiming that they are robust for this purpose [3].

XORShift Generators generally rely on bitwise operations and bit–shifting to generate sequences. Bits of the internal state are repeatedly shifted and XORed with themselves. This process is expressed as:

where

It is typical of these generators to have long periods and are extremely fast because they rely on bitwise operations to produce their values [17].

2.1.5 Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR)

Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) is an algorithm that is used to generate sequences simply by first shifting some bits and applying a function that is linear feedback based [18]. This can be mathematically expressed as:

where

2.1.6 The Blum Blum Shub (BBS)

The Blum Blum Shub (BBS) is an algorithm that generates sequences on the bases of the hardness of the residuosity problem [19,20]. The sequence is generated using the formula:

where

2.1.7 Lagged Fibonacci Generators (LFGs)

Lagged Fibonacci Generators Lagged Fibonacci Generator (LFG) are more like Fibonacci sequence, but with LFGs the value of a number is calculated by performing an operation (addition, subtraction, XOR, etc.) of the two preceding numbers and between the numbers, there may be a lag greater than 1 [21]. This is mathematically expressed as:

where

2.1.8 Cryptographically Secure PRNGs (CSPRNGs)

Cryptographically Secure PRNGs are PRNGs that generates sequences that are fit for cryptographic purposes. For a PRNG to be classified as cryptographically secured, sequences generated must be unpredictable, non-reproduceable, resistant to attacks and have high entropy [22].

2.1.9 Quasi–Random Sequence Generators

Quas–Random Sequence Generators are also called low discrepancy sequence. This PRNG is designed to cover a sample space in a uniform manner. The are deterministic and have a define mathematical properties making them one of the best for numerical integration and optimization [23].

Combination Generators are algorithms that combines at least two PRNGs to create a new one by leveraging on their individual strengths. They are most of the time more robust when compared to the individual algorithms [24].

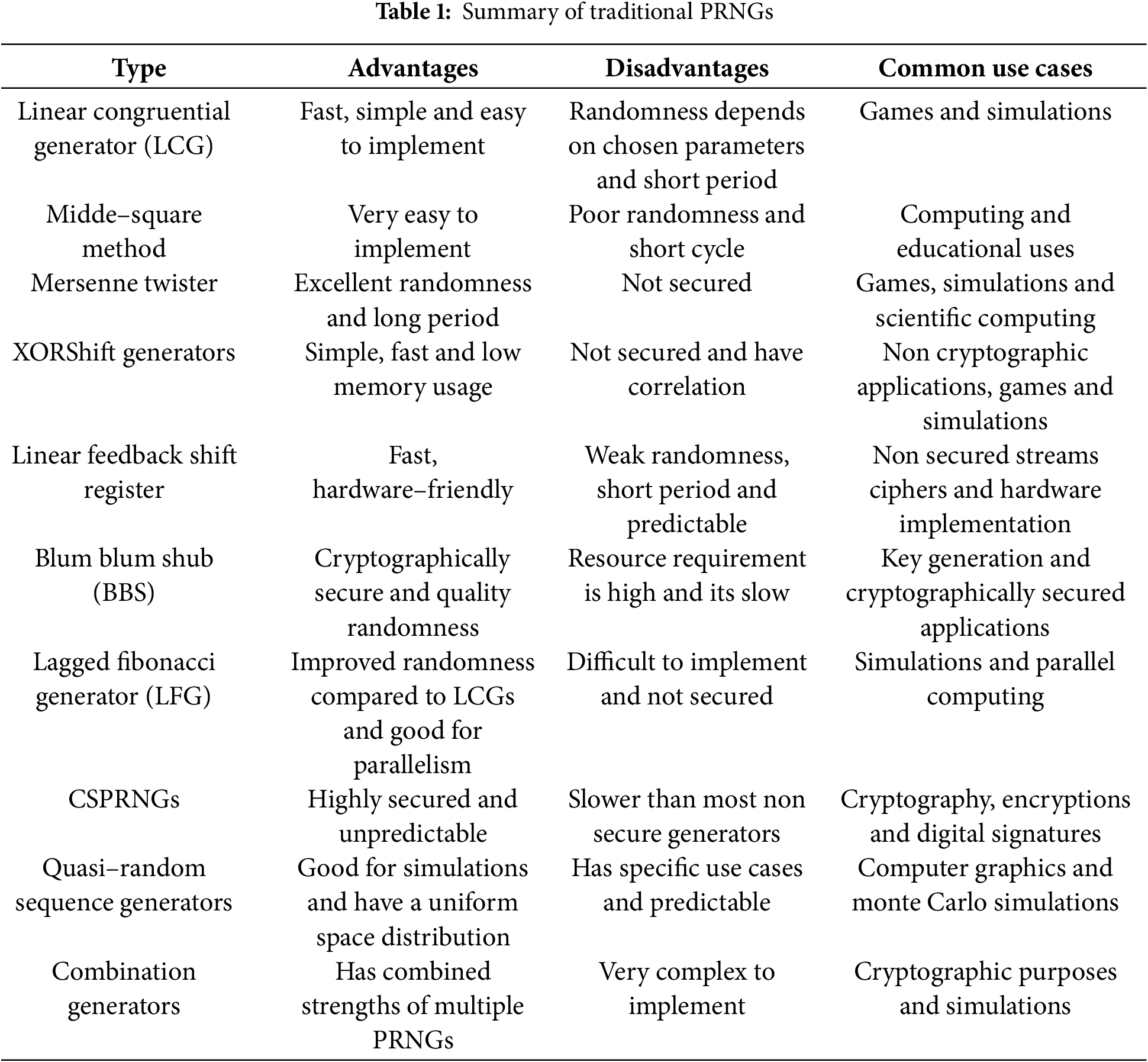

Table 1 summarises the advantages disadvantages and some common use cases of the pseudorandom number generators discussed so far.

Chaos-based pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) exploit the inherent unpredictability of nonlinear dynamical systems to produce sequences that mimic randomness while remaining deterministic. These systems are characterized by sensitivity to initial conditions, aperiodicity, and complex trajectories in phase space, making them suitable for applications requiring high-security and statistical robustness. Below, we delineate the principal mechanisms underpinning chaos-based PRNGs, emphasizing their mathematical foundations, operational characteristics, and practical implications [25].

The logistic map, a one-dimensional discrete-time system, is defined by the quadratic recurrence relation:

where

Proposed by Edward Lorenz in 1963, this continuous-time system models atmospheric convection through three coupled differential equations:

With canonical parameters

The Chen system, a hyperchaotic variant, extends the Lorenz model by introducing additional nonlinearities:

Characterized by multiple positive Lyapunov exponents, this system exhibits heightened complexity and unpredictability. However, its efficacy depends on meticulous parameter selection, and computational overhead limits its deployment to high-assurance environment such as blockchain consensus mechanisms and military-grade encryption [28].

The tent map, a piecewise linear function, is governed by:

where

A two-dimensional discrete-time system, the Henon map is described by:

For

The Rossler system simplifies chaotic dynamics with fewer parameters:

With

This nonlinear oscillator is governed by:

Under specific driving forces

2.2.8 Cellular Automata with Chaotic Rules

Cellular automata (CA), such as Rule 30, evolve discrete grids via local interaction rules. For a 1D CA, the state of each cell is updated based on its immediate neighbors:

The emergent complexity of CA systems enables parallelizable, hardware-efficient PRNGs, though periodic behavior in finite grids necessitates careful design. Applications include secure hardware tokens and edge computing devices [33].

2.2.9 Hybrid Chaos-Traditional PRNGs

Hybrid systems synergize chaotic and traditional algorithms, such as seeding a Linear Congruential Generator (LCG) with outputs from a Lorenz attractor. This approach balances the speed of classical PRNGs with the cryptographic strength of chaos, albeit at the cost of integration complexity. Use cases span real-time systems, including algorithmic trading and interactive gaming [34].

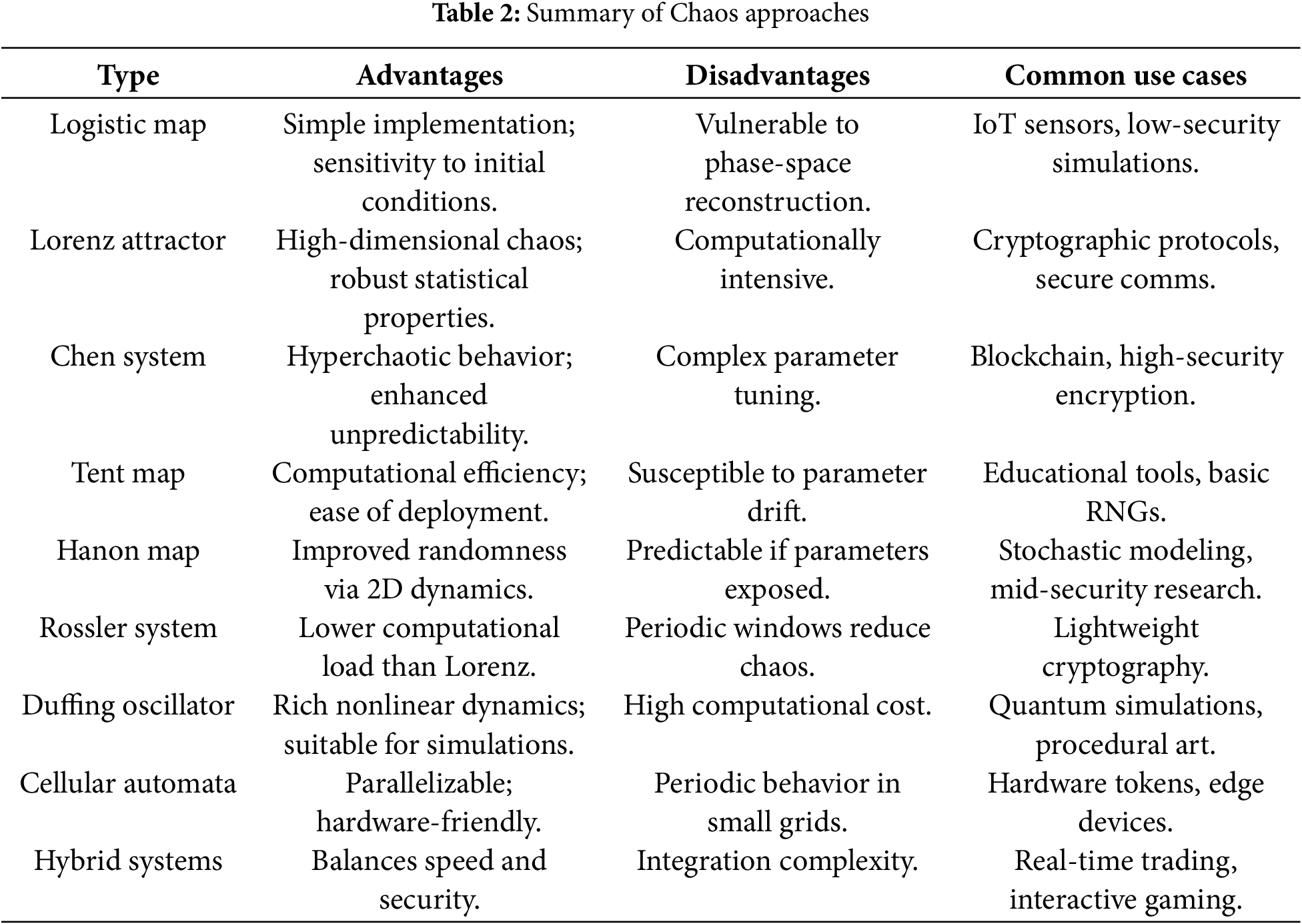

Table 2 summarises all the discussed chaos-based approaches with their respective advantages, disadvantages and common use cases.

Chaos-based PRNGs represent a confluence of nonlinear dynamics and computational ingenuity, offering a spectrum of solutions tailored to diverse security and efficiency requirements. From the pedagogical simplicity of the logistic map to the cryptographic rigor of hyperchaotic systems, these mechanisms underscore the transformative potential of chaos theory in modern computing. Future advancements will likely focus on optimizing hybrid architectures and addressing vulnerabilities inherent to finite-precision implementations, thereby expanding their applicability in an increasingly digitized world.

2.3 Machine Learning-Enhanced PRNG Approaches

This section discusses the various machine learning approaches including the data types required and their respective learning goals.

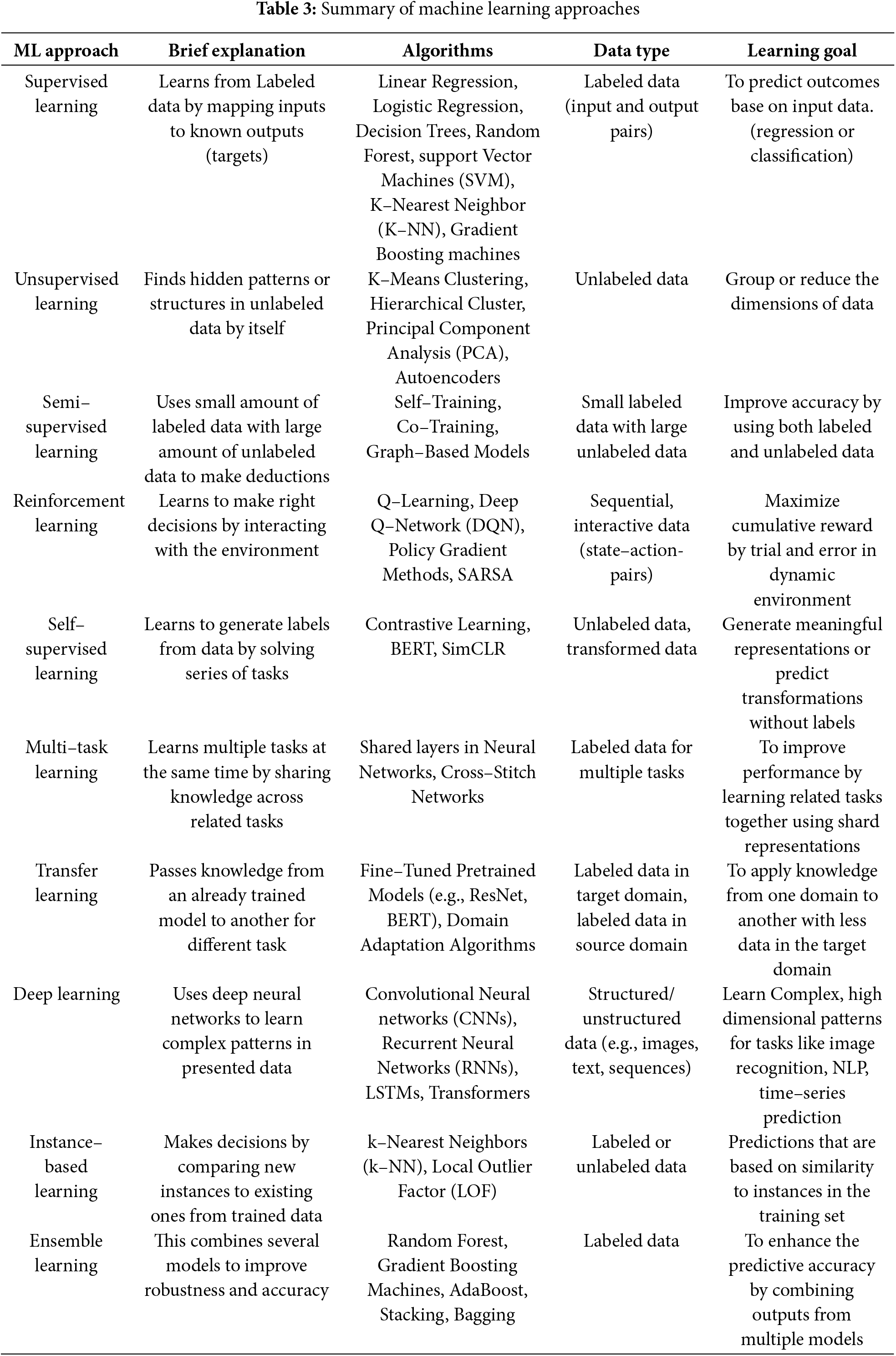

According to Chopra and Khurana [35], Machine Learning (ML) is a field in computer science under Artificial Intelligence where machines learn from data without being explicitly programmed. These machines improve their performance as they are exposed to more data. There are various types of machine learning approaches, and each approach has various types of algorithms that can accomplish different learning goals. For a machine leaning model to function, it must have the computational algorithm, features and variables based on which the model can make decisions and the expected output to determine accuracy level of the model. Also, these approaches are ideal for different domains. Some of these approaches are supervised learning, unsupervised learning, semi supervised learning, etc. Table 3 summarizes all the machine learning approaches discussed.

The dataset in supervised learning is the set of labeled examples

Unsupervised learning in machine learning refers to the process of modeling a dataset of unlabeled samples {

For instance, in aggregation, the framework determines the grouping identification that corresponds to each characteristic vector in the file, but in decreasing dimensionality, the outcome of the model is a characteristic vector with fewer attributes than the input (

2.3.4 Semi-Supervised Learning

In semi-supervised learning, a dataset with together considered and unlabeled samples is used; in most cases, there are far more unlabeled examples than labeled ones. The objective of a semi-supervised learning algorithm is the same as that of a supervised learning algorithm, notwithstanding this imbalance: to create a model that can infer the label for a given feature vector. Since it adds to the problem’s uncertainty, adding more unlabeled instances to the learning process initially may appear counterintuitive. Nevertheless, as a higher model size more accurately represents the fundamental chance delivery of the considered statistics, including unlabeled examples can provide more details about the issue. In theory, an algorithm for learning may make use of this extra data to enhance its model.

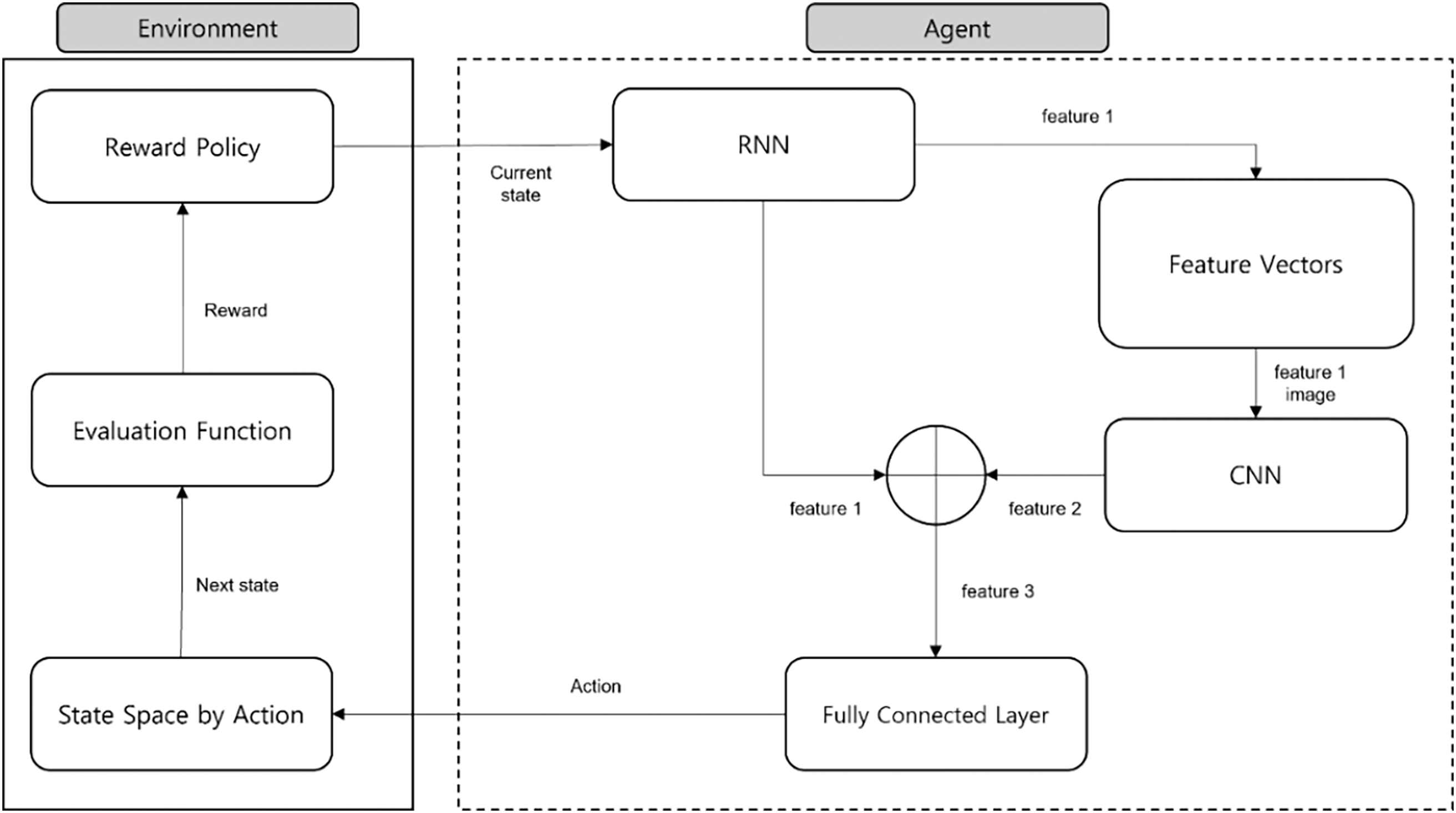

A machine learning subfield called reinforcement learning deals with the operation of an agent in an environment and the provision of incentives as feedback for its behaviors. The agent interprets the environment’s current state as a vector of features and can respond to it by acting. Every action has a reward connected to it, and it can also lead to a change in state. A reinforcement learning procedure’s goal is to discover a strategy that associates every state with the best course of action; optimality is well-defined as exploiting the predicted increasing recompence over an extended [36]. The policy function outputs a recommended course of action after receiving the state feature vector as input. This model works well for challenges involving sequential decision-making with long-term objectives.

From Table 3, one can easily deduce the various types of machine learning algorithms and their uses. Attempts have been made by researchers to use some of these algorithms either to improve some pseudorandom generators or to entirely propose novel approaches to generating random numbers using ML.

2.4 Machine Learning-Based PRNGs

Atee et al. [37] proposed a Sub Key Generation approach using Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) for neural network hidden layer. Their approach incorporates the Artificial Neural Network topology, seeds for pseudo random number generation and activation function in the primary key. This method begins with defining the key as

Lokesh and Kounte [38] proposed a Pseudo random number generator that uses a four–layer neural network with chaotic maps like cubic and piece–wise linear chaotic maps. Their approach initializes weights, generate control paraments and iterate through the neural network to produce the output sequences. This approach is simple and fast, making it suitable for real time applications. However, the complexity of neural networks combined with chaotic systems require high computational resources for implementation.

Machicao and Bruno [39] proposed a generalized method for a reliable Pseudorandom generator based on the digit precision of the chaotic discrete orbit points that is also called Deep-Zoom. Their work improved upon various properties of PRNGs such as uniform distribution, higher length period and randomness to ensure the security of the cryptosystems. Their approach improved the randomness of chaotic maps as compared to some traditional PRNGs, but its efficiency depends on the initial parameter and also requires high precision computing which is difficult to implement.

Gayoso et al. [40] proposed a generalized construction method of Pseudo Random Number Generators in that, each small pseudo generator is considered as a neuron of the Hopfield Neural Network. This approach used the Residue Number System in arithmetic calculations for every feedback line to incorporate nonlinearity in test system and to claim binary representations for small number of bits. The efficiency of this approach lies in the parallel operating property of RNS in various channels without data transformation, which results in higher speed and provides better randomness of PRNGs. But there are implementation challenges due to the introduction of RNS and further analysis need to be done on the practical application for further validation.

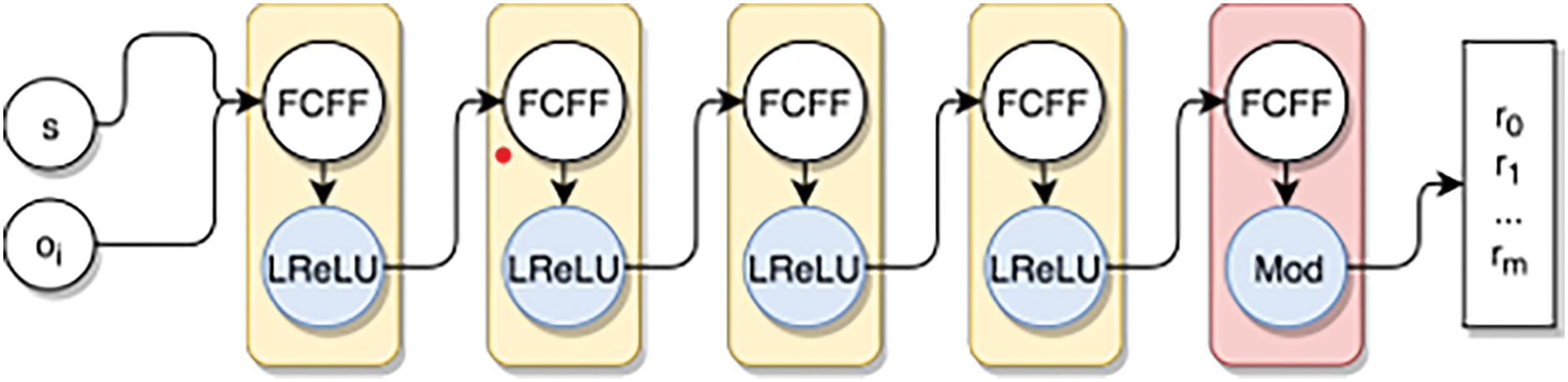

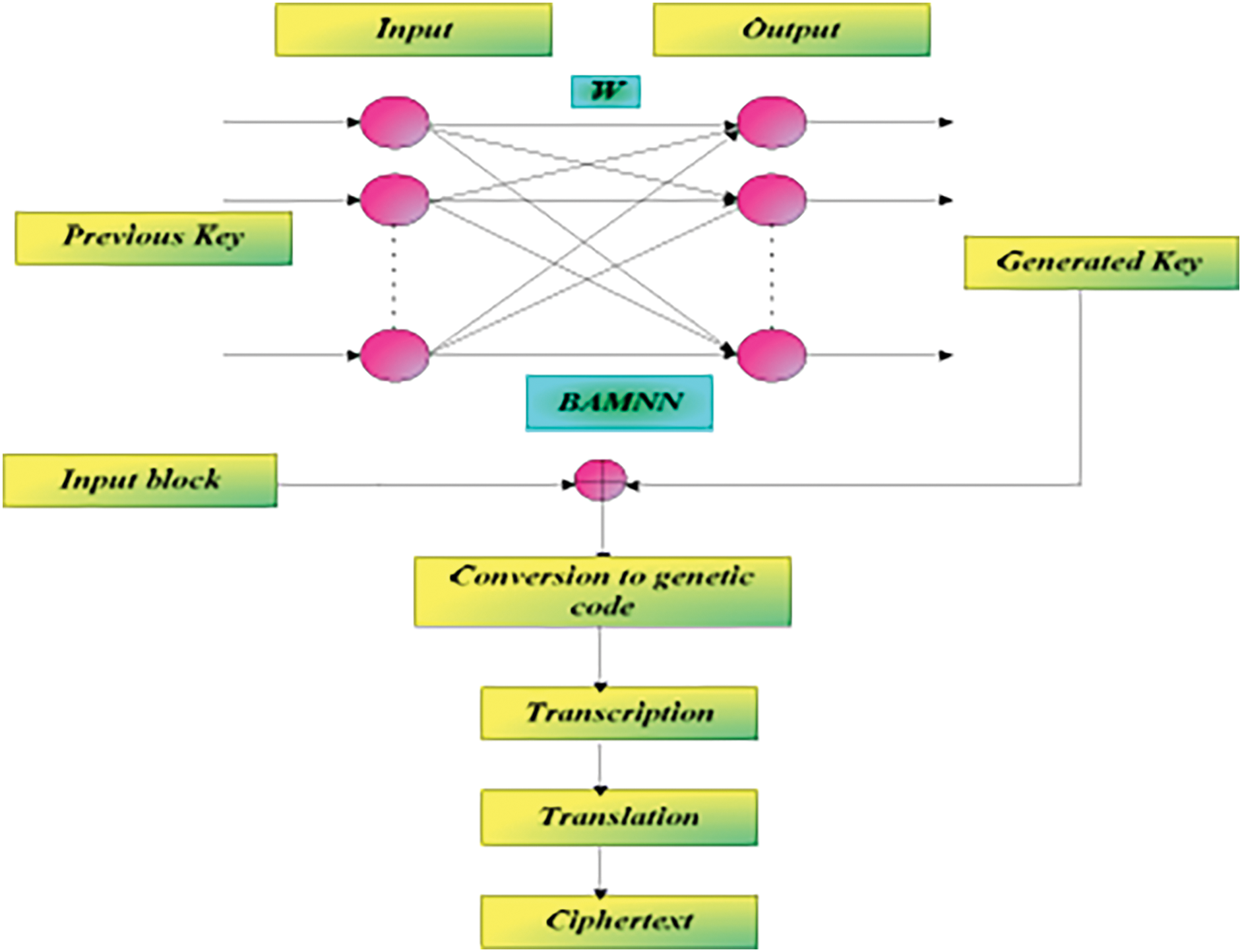

De Bernardi et al. [5] presented a new Machine learning based approach which uses the Generative Adversarial Networks to impactfully train the neural network to act as PRNG as shown in Fig. 1. This was done by partly concealing the outcome and training the adversary to map the concealed portion. Thus, the generator learned to generate unpredictable random sequences. The researcher demonstrated that, GAN can effectively train even a small feed-forward fully connected neural network to produce pseudo-random number sequences with good statistical properties. This approach produced sequences that pass around 99% of test instances using the NIST test suit. However, only statistical analysis was used to access the quality of PRNGs and this may require further cryptanalysis of the implementation.

Figure 1: Architecture of the generator: FCFF layers with leaky ReLU and mod activations [5]

Alloun et al. [41] proposed a pseudorandom number generator by fusing the sensitive dynamics of the Lorenz chaotic system and the modelling capacity of an artificial neural network (ANN). They first solve the Lorenz differential equations with a fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme to create a rich training corpus of state triples (x, y, z). A compact fully connected network (3-8-8-3 topology, ReLU activations, RMSprop optimiser, 10 epochs) is then taught to predict the next Lorenz state from the current one, reaching a validation loss of 2.37 × 10–7. During sequence generation only the fractional part of each 32-bit floating-point output is retained and concatenated, thereby suppressing amplitude-related correlations and yielding a binary stream. The proposed generator exhibits several notable strengths. Statistically, the bit-stream passes all sub-test in the NIST SP 800-22 battery, from monobit frequency to random-excursions variants. Security-wise, replacing the seven-parameter Lorenz key with 115 learned weights inflates the effective key-space from 2224 to 23680 which is an increase of roughly 3.6-fold over the best prior Lorenz-ANN design. The authors also argue that the neural surrogate inherits the noise immunity and parallel-friendly nature of ANNs, making the scheme attractive for high-throughput hardware deployments. Because the network is trained on a single set of Lorenz parameters, its unpredictability outside that operating point remains untested as the authors acknowledge residual errors between ANN output and the reference solver (RMSE up to 0.63). Cryptanalytic metrics, such as period length, linear complexity under keyed attack, or resistance to side-channel leakage, are left unexplored. Computational overhead of forward passes and IEEE-754 bit manipulation may offset the statistical gains in resource-constrained environments.

Hu et al. [42] proposed another machine learning based pseudorandom number generator using Cellular Neural Network that possesses hyper chaotic behavior which is ideal for initial parameters to the PRNGs. This approach offers secured randomness, simple operation, increased length of the sequence, and increased search space but also has several chaotic iterations leading to high cost of computation.

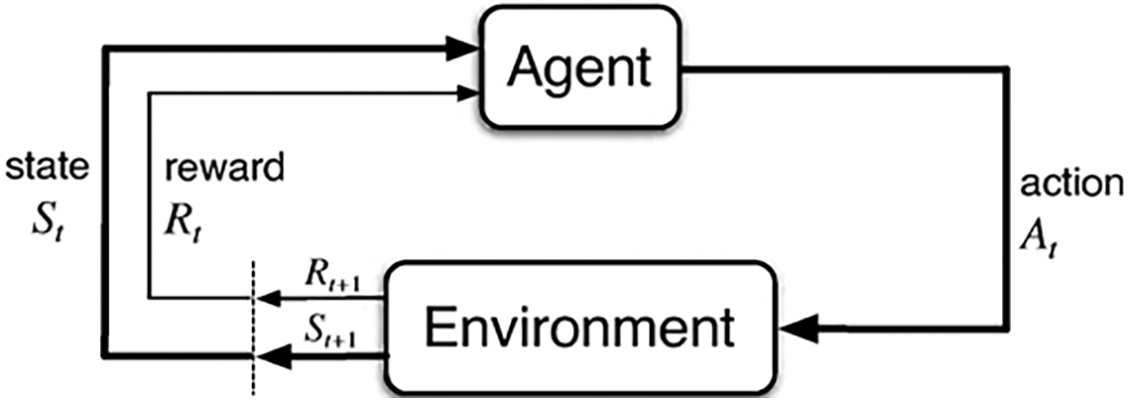

Reddy et al. [43] presented a machine learning based cryptographic system that relies on Hybrid Key generation approach and biographically inspired DNA system using genetic encoding, transcription and translation. The researchers made use of a Bidirectional Associative Memory Neural Network (BAMNN) as a memory storage for the generated keys to train the NN and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) for weight factor in the neural network as shown in Fig. 2. This approach enhanced security, but the complexity of the system makes it challenging to implement as it requires high resources for key generation and encryption process.

Figure 2: Encryption and key generation process in proposed cryptosystem [43]

Pasqualini and Parton [44] developed a Pseudo random generator based on the reinforcement learning method (Fig. 3) and Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM). This approach models the PRNG as a partially observable Markov Decision Process (MDP). This approach improved the properties of the generated sequence as compared to other models, but it involves a highly complex RL algorithms and neural network architecture which makes it challenging to implement. Also, action space grows exponentially with length of generated sequence making scalability difficult beyond certain limits.

Figure 3: Reinforcement learning [44]

Pasqualini and Parton [8] also used a machine learning technique for producing Pseudo Random Number Generator from base level. The researchers used the Reinforcement Learning (RL) approach wherein PRNGs could be learned to improved generated sequence for every iteration that solves N-dimensional navigation problems, where N is the length of the desired sequence to be generated. Their approach improved accuracy and efficiency of predictive models but requires large amount of labeled data and risks overfitting.

Lin et al. [9] developed a scheme of the symmetric cryptography by the integration of Chaotic map and Multilayer Machine Learning Network (MMLN), where the chaotic map proactively generated the dynamic pseudo random sequences with the unique control parameters and provided fastest key generation for the real-world implementations. Their work made an efficient MMLN to train the cipher code protocol by an optimization algorithm to create an encrypted network in cryptosystem with high confidentiality, recoverability and large information transition. But the performance of this model is significantly influenced by the initial parameters used.

Park et al. [6] proposed a Dynamic pseudorandom generator that uses a machine learning technique called Reinforcement Learning to choose the best characters to ensure the random property of the generated number sequences in every possible way by optimization. They incorporated the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to provide the long-term memory to hold the previous patterns and feature vectors that are extracted by convolutional NN to generate the random numbers as shown in Fig. 4. Evaluation of this approach showed improved randomness of generated sequence, but this approach contains complex structures with several parameters which makes it require high computational resources.

Figure 4: Dynamical pseudo-random generator using reinforcement learning [6]

Patel and Thanikaiselvan [45] proposed a Pseudo random number generator using Latin Square and Machine learning neural network technique to propose an image encryption algorithm. The researcher made use of Latin square to model cryptographic key images in the finite field then XOR with the input matrices to extract encrypted images and GA to preserve the best encrypted image search. This approach secures multimedia data during transmission and resistant to various attacks. However, the proposed random number generator requires further evaluation to access its efficiency.

Okada et al. [7] presented a Learned pseudorandom number generator using Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) and Mersenne Twister (MT) pseudorandom generator. The researchers used the MT to generate an inexhaustible sequence of random numbers to train the WGAN model. The learning is done without any arithmetic programming code implementations. The experimental results show improved randomness and robustness of the proposed learned PRNG, and that enhances unpredictability for the safety information systems. But this approach is prone to overfitting after 450,000 iterations after extensive training with huge amounts of data.

2.4.1 Security Implications of Machine Learning–Based PRNGs: Potential Vulnerabilities and Attack Vectors

Machine learning–based pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional and chaos-driven approaches, promising improved randomness, adaptable designs, and stronger security [5,44]. Yet, beneath these impressive capabilities lie potential vulnerabilities and avenues for exploitation. Below, we consider how these vulnerabilities might unfold, drawing on perspectives common to both traditional cryptanalysis and modern machine learning research.

One of the central challenges with machine learning–based PRNGs is the risk that an attacker could gain access to the trained neural model [7]. Traditional PRNGs rely on transparent algorithms—like Blum Blum Shub or Mersenne Twister whose security can be scrutinized mathematically [2]. However, in an ML-based system, if someone uncovers the hidden weights or architecture, they can replicate the generation process themselves. This duplication effectively hands them the keys to the generator, allowing them to predict every future output in a nearly perfect clone of the original environment. Preventing such breaches may require periodic re-seeding or combining the ML model’s outputs with proven cryptographic primitives, ensuring that knowledge of the neural network alone is insufficient for full prediction [46].

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning (RL) often rely on adversarial refinements to train robust models. Ironically, a system designed to produce strong pseudorandom sequences might inadvertently learn only to “pass” standard randomness tests, leaving deeper patterns undetected [5]. In such scenarios, if an attacker trains a second neural network one specifically tuned to identify hidden correlations in the PRNG’s outputs vulnerabilities can be exposed. Likewise, mode collapse in GAN-based systems or flawed reward signals in RL-based generators can produce repetitive outputs that, once collected in sufficient quantities, become predictable [6].

At the heart of any PRNG lies the notion of a “seed,” and machine learning designs expand this concept into a vast web of parameters and hidden states [43]. Although chaotic neural networks and other advanced architectures can, in theory, provide strong randomness, an adversary who gains partial insight into these states may reconstitute a large portion of the generator’s logic [38]. Implementing secure parameter storage, encrypting model weights, and periodically refreshing seeds through trusted hardware-based randomness can thus be essential to defense.

Traditional PRNGs are relatively transparent; their equations and modular arithmetic can be exhaustively analyzed to detect vulnerabilities (Bhattacharjee and Das, 2022). Machine learning-based PRNGs, by contrast, rely on deep neural layers that are notoriously opaque [9]. While some argue that this “black box” deters attackers, it also hinders formal proofs of security. Indeed, the lack of widely accepted frameworks to demonstrate unbreakable security for neural-based PRNGs leaves them more open to suspicion. A practical compromise is to merge ML-driven outputs with classical cryptographic transformations hashing, block-cipher modes, or keyed transformations to couple the adaptability of machine learning with the reliability of proven ciphers [8].

Even if a machine learning–based generator is solid on the software side, hardware-level channels can betray internal states. Characteristic timing patterns or power usage may inadvertently map to specific neural states during inference, affording attackers a side-channel path [46]. While masking or constant-time execution techniques exist, applying them reliably across large-scale neural architectures can be computationally expensive, especially in high-throughput applications.

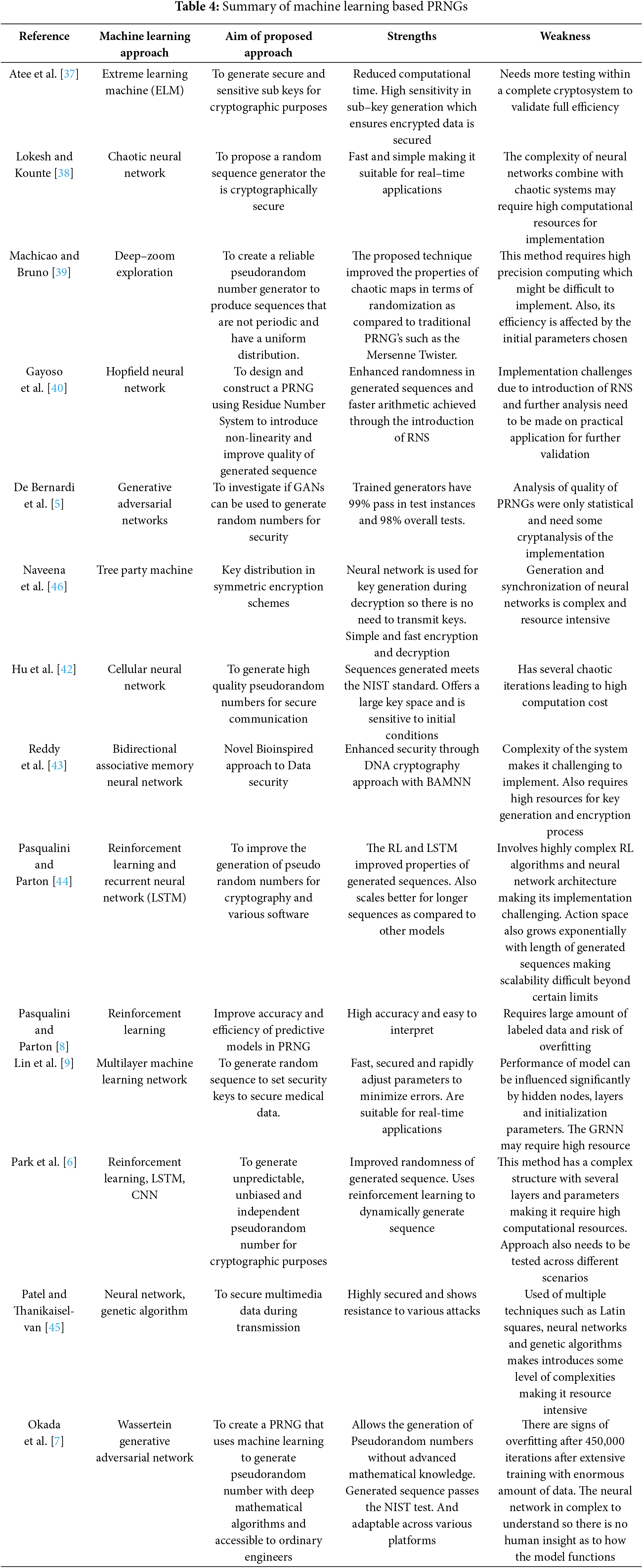

In sum, machine learning–based PRNGs offer tantalizing promises higher degrees of randomness, real-time adaptive behavior, and intricate nonlinearities. Yet these same features open new routes for attack: adversarial ML, covert model extraction, overfitting, or side-channel leaks. As a result, many researchers recommend a judicious integration of ML-based outputs with cryptographic post-processing, secure parameter management, and ongoing validation beyond standard test suites [7]. By adopting this layered approach, developers can harness the strengths of machine learning without relinquishing the practical safeguards honed over decades of cryptographic research. Table 4 presents a summary of the discussed machine learning based PRNGs with their respective aims, strengths and weaknesses.

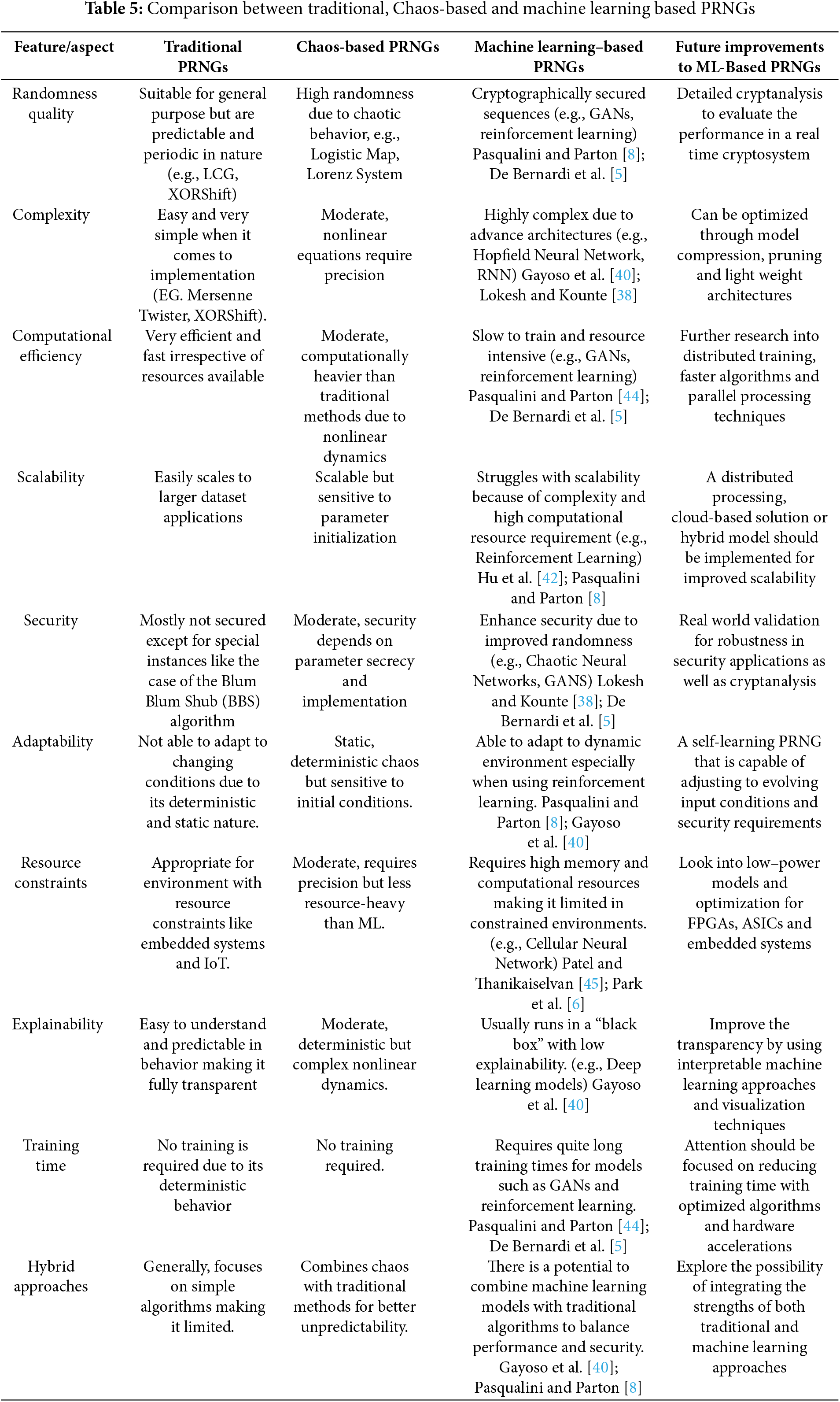

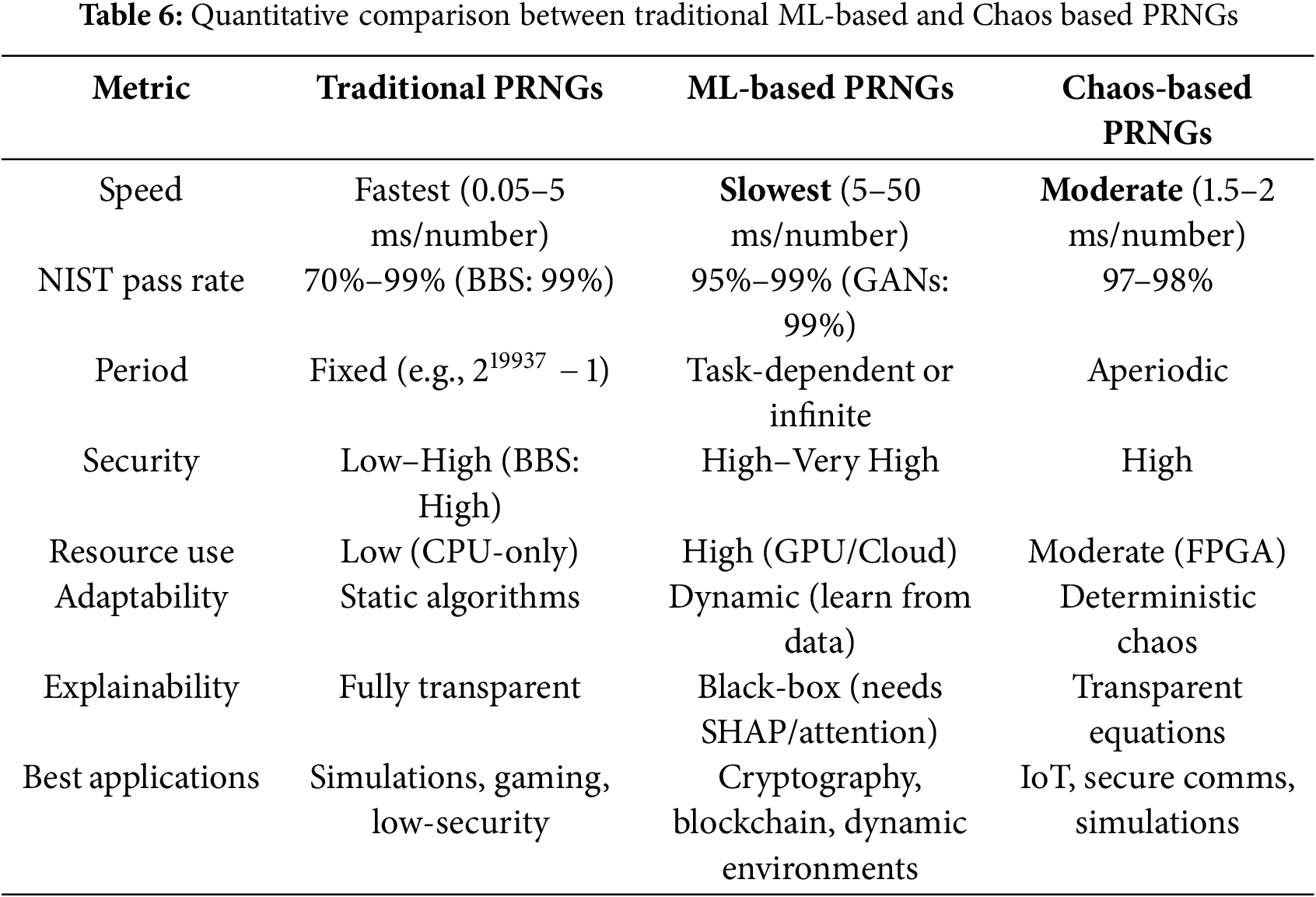

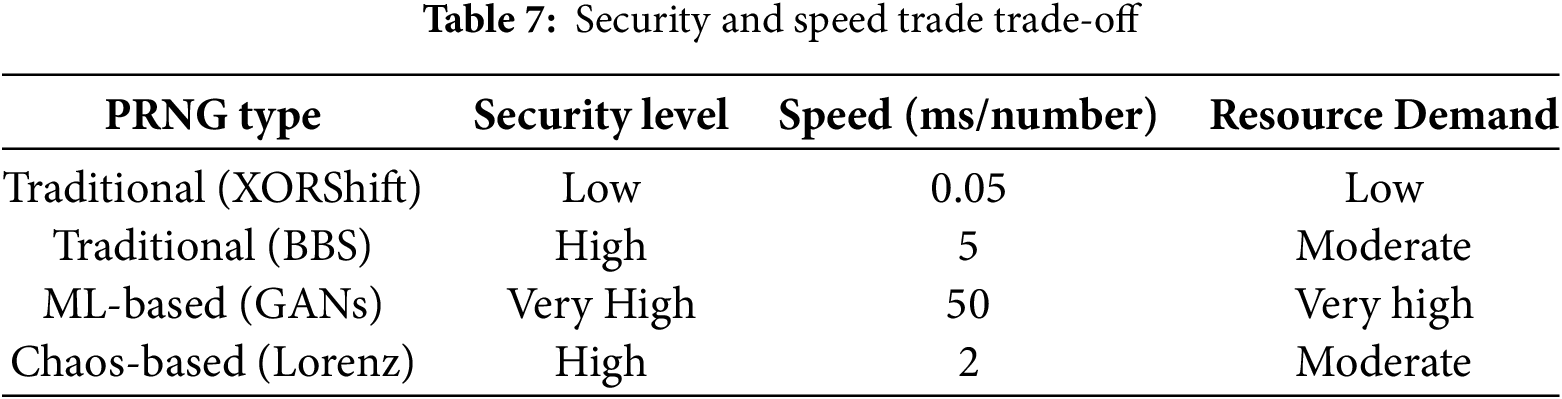

The application and significance of pseudorandom number generators in simulations, games, cryptography and statistical sampling cannot be overstated. The growing use of machine learning approaches as a substitute to traditional and chaos-based PRNGs cannot be overlooked. This is because the machine learning approaches have improvements in the area of randomness, security and adaptability. Tables 5–7 show various comparisons between traditional, chaos-based and machine learning approaches.

4 Discussion and Future Directions

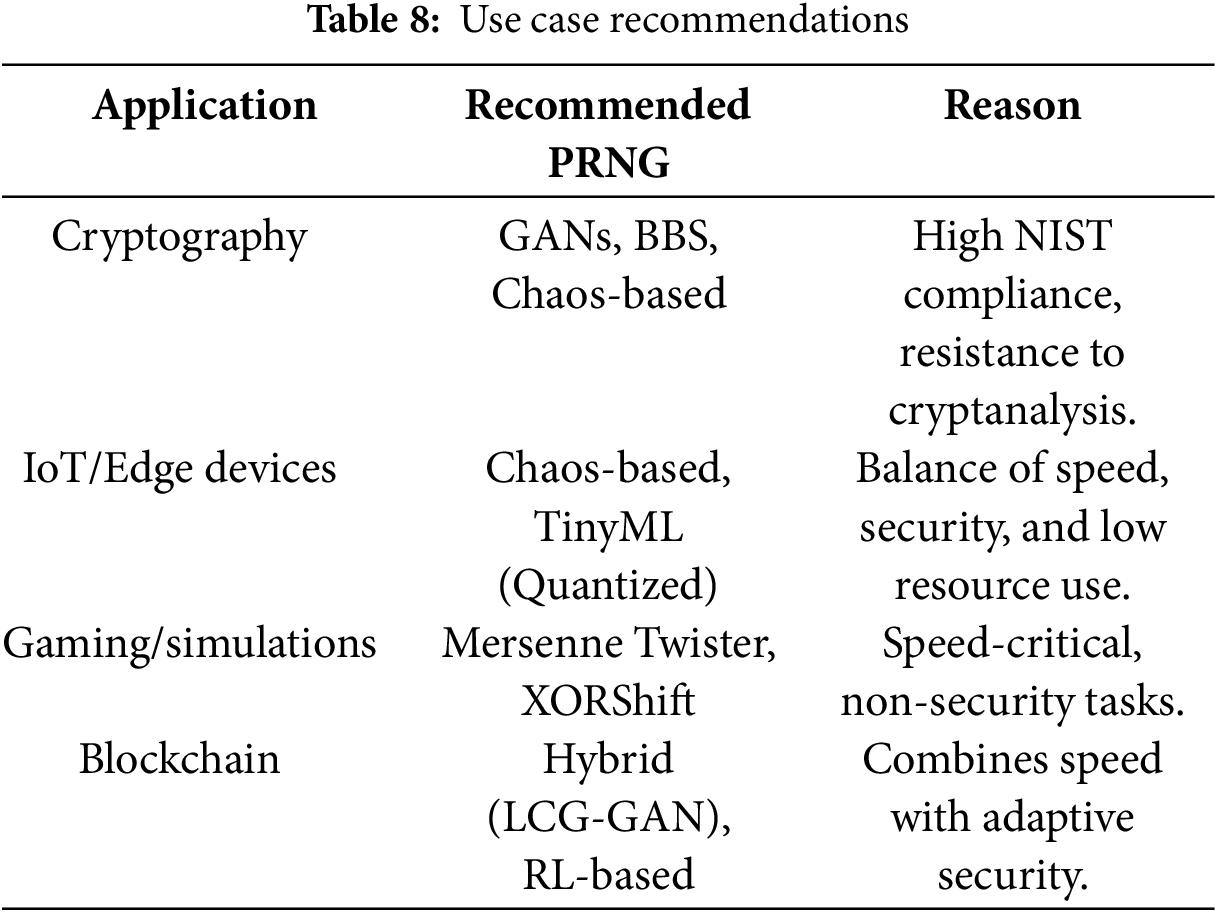

In comparing traditional, chaos-based, and machine learning (ML)–based pseudorandom number generators, it becomes clear that each approach offers distinct advantages and trade-offs as shown in Tables 5–7. In light of the distinct advantages and trad-offs, each approach is ideal for peculiar cases as shown in Table 8. A holistic evaluation across randomness quality, complexity, efficiency, scalability, security, adaptability, and explainability highlights how newer ML-driven techniques aim to overcome limitations of classical methods, while also introducing new challenges. This section synthesizes these comparisons and outlines future research directions, emphasizing resource optimization, model transparency, hybrid designs, and cryptographic validation.

4.1 Randomness Quality and Statistical Robustness

Traditional algorithmic PRNGs (e.g., linear congruential generators or Mersenne Twister) are well-studied and generally provide high-quality uniform randomness for simulation purposes. They have long been tuned to pass standard statistical test suites (with Mersenne Twister achieving a period of

Despite high aggregate test scores, each paradigm has nuances in randomness quality. Traditional PRNGs are designed with mathematical guarantees for distribution uniformity and long periods, but their linear structures can cause subtle patterns (e.g., the spectral patterns in linear congruential generators). Chaos-based generators introduce nonlinearity and high sensitivity to initial conditions, which generally enhances unpredictability; yet finite-precision implementations of chaotic maps can sometimes lead to short cycles or mild biases if not designed carefully. Indeed, the chaotic “randomness” is contingent on system parameters – poorly chosen parameters can degrade randomness, while well-chosen chaotic systems yield competitive randomness suitable even for encryption and image processing applications [47]. ML-based PRNGs, being data-driven, do not rely on explicit formulae at all—they learn to emit statistically random sequences. This data-driven nature means they can, in theory, approximate extremely complex distributions. Empirical evidence (e.g., GAN-based generators) shows that a sufficiently trained neural model can reproduce the statistical properties of true random sources or robust classical PRNGs [5]. One advantage is that ML methods can be trained or tuned to target the passing of specific randomness test batteries, effectively “learning” to avoid known statistical pitfalls. However, there is also a danger of overfitting to test suites. A model might learn to pass known tests while still harboring undetected patterns. Overall, all three approaches can achieve excellent randomness quality with careful design, but ML-based methods are notable for achieving this without requiring an explicit algorithmic structure, instead leveraging the capacity of neural networks to mimic randomness.

4.2 Complexity, Efficiency and Scalability

The complexity of PRNG design and its computational efficiency vary greatly across the three paradigms. Traditional PRNGs are typically lightweight in terms of algorithmic complexity. They often consist of simple arithmetic or bitwise operations (e.g., linear recurrences, bit shifts, or Xorshift operations), making them extremely fast and resource-efficient. This simplicity translates to low computational overhead per random number generated—a crucial factor for applications requiring billions of random samples. Because their behavior is well-understood, traditional generators can be implemented in hardware or optimized at the instruction level to further improve throughput. The trade-off for this simplicity is that the generator’s statistical properties are fixed once the algorithm is chosen; improving their randomness often requires deep mathematical analysis or developing a new algorithm altogether. Chaos-based PRNGs tend to be more complex in design, as they derive from nonlinear iterative equations or differential equations. Implementing a chaotic map like the logistic map or a higher-dimensional chaotic system involves iterative floating-point computations. In practice, a chaos-based generator might require multiple iterations per output or high-precision arithmetic to maintain chaotic behavior, making them moderately more computationally expensive than linear PRNGs. However, many chaotic maps are still relatively simple functions (e.g., polynomial maps, piecewise linear functions), so software implementations can often generate millions of values per second, and hardware implementations (analog or digital) can exploit inherent parallelism. The complexity here lies more in analysis—understanding and tuning the chaotic system— than in runtime cost. ML-based PRNGs, on the other hand, introduce significant complexity both in design and execution. Designing an ML-based generator involves training a neural network or reinforcement learning agent, which is a computationally intensive process requiring large datasets of random numbers or numerous training episodes. References [8,9] noted that their deep reinforcement learning approach had to navigate a huge search space and was limited by training instability for long sequences, ultimately managing sequences up to 1000 bits long in their recurrent model [44]. The generation phase of an ML-based PRNG (after training) involves forward passes through a network (e.g., an RNN or GAN generator). This is markedly slower than a few arithmetic operations; for instance, generating a single number might require matrix multiplications and nonlinear function evaluations in a neural net. Reference [7] report that although their WGAN-based generator could produce high-quality outputs, the model began to overfit after ~450,000 training iterations. An indication of the immense training effort and the delicate balance in model complexity. Thus, while runtime generation from a trained model can be made reasonably fast with modern hardware (potentially leveraging GPU parallelism to produce many random numbers in batch), it is still generally less efficient than traditional PRNGs, especially on general-purpose CPU architectures.

Scalability is another critical aspect. The ability of a PRNG to produce long sequences (or many parallel sequences) without degradation. Traditional PRNGs excel in this regard—algorithms like Mersenne Twister are explicitly engineered for astronomically long periods, and multiple independent streams can be created via different seeds or algorithmic variants. They also have well-understood scaling in parallel environment. For example, leap-frog or sequence splitting techniques allow traditional generators to be used in multi-threaded simulations with minimal overlap. Chaos-based PRNGs can also produce long sequences, but their effective period is bound by the precision of the arithmetic and the nature of the map. A chaotic sequence in real arithmetic never repeats, but in finite precision it will eventually cycle. In practice, well-designed chaotic systems can achieve very long cycle lengths (comparable to traditional PRNG periods) if implemented with high precision or by combining multiple chaotic elements. Recent work has explored coupled map lattices and higher-dimensional chaotic systems to boost complexity and reduce the likelihood of short cycles [47], Still, ensuring truly long-term decorrelation in chaos-based generators can be challenging without resorting to large state representations (akin to large PRNG state in classical methods). ML-based PRNGs face unique scalability challenges. A neural network has a fixed number of parameters and (for many designs) a fixed input size, which might implicitly limit the period or the amount of randomness it can produce before repeating patterns. Recurrent neural network-based PRNGs, like the one by Pasqualini & Parton, effectively carry state in their hidden layers, but as noted, the model they used did not scale well beyond sequences of 1000 bits without retraining [44]. This suggests that scaling an ML-based PRNG to arbitrarily long sequences could require increasing model complexity (more layers or neurons) or using streaming strategies. On the upside, some GAN-based approaches operate in an “end-to-end” fashion and can generate outputs of arbitrary length by sequentially applying the network to generate blocks of bits, though ensuring that the concatenated output remains random over very long stretches is an open question. Another aspect of scalability is the ability to produce many random streams in parallel: an ML model could in principle be replicated or vectorized to produce multiple streams, but this multiplies the resource usage (memory for multiple models or larger batch computations). Researchers are beginning to address this. For example, Kim et al. [48] integrated an RNN-based generator into an edge computing platform, demonstrating that with model optimization, even resource-limited devices (like those in Internet-of-Things scenarios) can run ML-based PRNGs efficiently. Such efforts indicate that while ML-based PRNGs are currently heavier, there is room for optimization (pruning, quantization, or specialized hardware acceleration) to narrow the efficiency gap. In summary, traditional PRNGs offer simplicity and speed with proven large-scale performance, chaos-based PRNGs introduce moderate complexity with acceptable efficiency and unique state-space properties, and ML-based PRNGs incur high complexity and computational cost but open the door to generating randomness through learned behavior–at the expense of careful scaling considerations.

4.3 Security and Explainability

Security, meaning resistance to prediction or manipulation is a crucial consideration for PRNGs, especially in cryptographic contexts. Traditional PRNGs vary widely in security. Non-cryptographic PRNGs (like linear congruential or Mersenne Twister) are not intended to be secure. Their internal state can often be inferred from a segment of output (for example, observing 624 outputs of Mersenne Twister allows exact prediction of all future outputs, due to its linear structure). Cryptographically secure PRNGs (CSPRNGs), on the other hand, are designed so that predicting future bits is computationally infeasible without knowing a secret seed. They achieve this by using one-way functions or cryptographic primitives, e.g., using block cipher or hash function outputs as the random sequence. These are still “traditional” in design but sacrifice some performance for security guarantees. Chaos-based PRNGs were once hoped to naturally provide cryptographic-strength secrecy because chaos is unpredictable in theory. However, practical analyses have revealed that deterministic chaotic systems can still be attacked if an adversary has partial information. According to Al-Daraiseh et al. [47], Yeniçeri et al. [49] demonstrated a concrete attack on a time-delay chaos-based RNG by synchronizing to its trajectory—effectively predicting future values by coupling a replica system once a few outputs were known. Other cryptanalyses of chaos-based schemes have identified weaknesses such as short cycles, phase space leakage, or insufficient complexity, and have broken proposed chaotic ciphers by exploiting those flaws. These findings underscore that chaos alone does not guarantee security; a chaotic PRNG must be carefully analyzed just like any other, and often additional techniques (e.g., perturbing the chaotic process with external entropy or using compound chaos systems) are needed to approach cryptographic security. Recent chaos-based designs have started to incorporate such improvements. For instance, using multiple coupled chaotic maps with adaptive parameters to expand the key space and thwart synchronization attacks. The explainability of traditional and chaotic PRNGs is relatively high. Their mechanisms are given by mathematical formulas, so one can in principle trace how an output is produced from the seed and analyze the transformation. This transparency aids in security analysis (finding linearity, biases, etc.). At the same time, that transparency can be a double-edged sword as it makes it easier for attackers to understand the generator’s structure. Security for classical PRNGs thus comes from proven difficulty of inverting or analyzing the function (as in CSPRNGs), rather than secrecy of the algorithm.

ML-based PRNGs introduce new dynamics for security and explainability. On one hand, they are black boxes by nature—a neural network’s logic is encoded in millions of weights rather than a simple formula, which can obscure any underlying patterns. Proponents of ML-based PRNGs have argued that this complexity can enhance security: the generator may have no simple mathematical structure to exploit, and if the model is large and proprietary, an adversary would find it hard to reverse-engineer. For example, Park et al. [6] assert that tracking the operations of their deep learning model (with parameters adaptively changing via reinforcement learning) is practically impossible, hence the pattern of random bits cannot be discerned by an attacker. ndeed, an RL-based approach that continually updates its parameters could thwart an adversary’s attempt to lock onto a moving target. Additionally, De Bernardi et al. [5] took an adversarial training approach to security by concealing a portion of the generator’s output bits and training a discriminator to predict them, they forced their GAN-based generator to produce outputs that an AI adversary could not reliably predict. This innovative method essentially built a cryptographic mindset into the training process, aiming to maximize unpredictability, not just match a distribution. These examples show how ML methods can be tailored for security considerations in ways that classical PRNGs are not. However, caution is warranted. The lack of explainability of ML models makes it difficult to prove any security property. A neural network might inadvertently learn some subtle internal pattern or state cycling that is not obvious to developers but could be learned by an attacker with enough samples. For instance, one could imagine training a secondary machine learning model on the outputs of a supposedly random generator to see if it can distinguish it from true random as a form of ML-based cryptanalysis. If that secondary model finds a predictor, it would indicate a flaw. At present, ML-based PRNGs have not undergone the decades-long scrutiny that traditional cryptographic PRNGs have. There is also the issue of the seed and model secrecy: if an adversary somehow obtains the trained model (weights) of an ML PRNG, the security might be compromised similarly to knowing the algorithm of a classical PRNG. The model could be simulated to predict future outputs unless it incorporates a hidden secret. This suggests that for an ML PRNG to be cryptographically secure, it might need to combine with traditional techniques. For example, using a secret cryptographic key either as part of the input or embedded in the network initialization so that even knowledge of the architecture doesn’t allow prediction without the key. As for explainability, ML models are currently largely opaque, which complicates both trust and debugging. Users and developers might not know why an ML-based generator produces a given sequence or how close it is to failing a certain randomness test. This stands in contrast to chaos-based systems, where one can often relate statistical properties to known chaotic parameters, or classical ones where theoretical analysis is possible. The community is beginning to address this by exploring interpretable models (e.g., smaller networks or ones with constrained structures) and by applying formal analysis to neural networks. For example, some researchers apply explainable AI techniques to gauge which parts of a network contribute to randomness, but this is an emergent area. In summary, ML-based PRNGs may ameliorate some traditional security issues (by embedding unpredictability in complex models) but lack the transparency that engineers and cryptographers are accustomed to, meaning extensive testing and new analysis methods are needed before they can be trusted in high-security applications [7]. At present, they should be used with caution in security-critical contexts until more cryptographic validation is performed.

4.4 Current State Cryptanalysis for Traditional, Chaos-Based, and Machine Learning–Based PRNGs

Modern pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs), be they traditional, chaos-based, or machine learning–driven are evaluated not merely by their statistical performance but by how effectively they withstand adversarial scrutiny. This section provides an overview of the cryptanalytic challenges each PRNG category faces.

Early PRNGs (e.g., Linear Congruential Generators, XORShift, and even the popular Mersenne Twister) rely on fairly transparent, straightforward arithmetic or bitwise operations. While this simplicity underpins their speed and ease of analysis, it likewise renders them vulnerable to predictable behavior once an adversary observes enough consecutive outputs. For instance, Mersenne Twister’s internal state can be deduced after capturing 624 successive 32-bit outputs, enabling an attacker to replicate all future values [2].

Security Implication: These methods suffice for simulations or non-critical randomization tasks but lack the unpredictability required in cryptographic settings unless augmented by cryptographic post-processing or robust seeding mechanisms.

Notable Exceptions like Blum Blum Shub (BBS) offer theoretically stronger security grounded in number-theoretic hardness, but trade off speed and ease of deployment.

Traditional PRNGs often exhibit fixed periods (e.g., 219937−1 for Mersenne Twister). Although large, once identified or partially compromised, the stream’s future outputs become guessable. Additionally, if a system uses limited-entropy seeds, cryptanalytic attacks grow much simpler, as the effective keyspace shrinks drastically (Okada et al., 2023).

Chaos-based designs (e.g., logistic maps, Lorenz systems) rest on the premise that chaotic dynamics in real arithmetic are unpredictable over long windows. In theory, these systems exhibit aperiodicity and sensitivity to initial conditions. Nevertheless, hardware and software introduce finite precision, causing chaotic orbits to fall into shorter cycles [9]. Adversaries can exploit these cycles often by estimating or partially reconstructing the chaotic state space-turning “unpredictable” streams into a solvable puzzle [38].

Security Implication: Even robust chaotic maps can have hidden periodic windows if parameters or step sizes are poorly chosen. Without meticulous engineering, cryptanalytic tools can uncover short cycles or approximate the map’s behavior to predict subsequent outputs.

A core tenet of chaos-based PRNG security is safeguarding the initial parameters. If these parameters leak, or if partial outputs reveal a pattern, an attacker can approximate or synchronize to the chaotic trajectory [5]. This underscores why carefully managed seeds, parameter updates, or external entropy injection is critical in real-world chaos-based solutions.

Hybrid Approaches: Some researchers embed chaos-based PRNGs within classical block ciphers or hash-based frameworks to mitigate the threat of direct parameter inference. While this can bolster security, it also introduces added design complexity and the typical overhead of cryptographic primitives.

4.4.3 Machine Learning–Based PRNGs

Machine learning–driven PRNGs often employ deep networks (e.g., GANs, RNNs) that learn to replicate random-like distributions. Because these networks have millions of tunable weights, proponents argue that the architecture’s complexity can obscure direct linear attacks. However, the heightened complexity also raises the risk that a malicious party could extract or approximate the model [6].

Security Implication: If an adversary gains knowledge of the trained network (e.g., through side channels or compromised hardware), they can fully replicate the generator. Hence, rigorous model-protection (such as encrypting weights) and frequent reseeding or randomizing portions of the network become vital for real-world security.

Innovations such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning (RL) can yield PRNGs that pass standard randomness test batteries with near-flawless rates [5]. Yet these successes may hinge on training data that exclusively targets those same tests, risking “overfitting” the generator to known benchmarks. An adversary can train a secondary “discriminator” or specialized model to detect subtle correlations not flagged by mainstream test suites, thereby undermining the generator’s output secrecy [46].

Security Implication: The black-box nature of deep neural networks makes it challenging to ensure no hidden patterns remain. As such, cryptanalysts are increasingly applying ML-based cryptanalysis to these PRNGs, searching for exploitable structures or repeating motifs in high-dimensional output spaces.

Unlike classical cryptographic PRNGs, machine learning–based models lack robust reductionist proofs tying their security to well-known hard problems. While chaotic systems similarly lack bulletproof proofs of unpredictability, ML-based PRNGs compound the issue with their “black-box” training processes [43]. Until standard proof frameworks or certification mechanisms emerge, they must be tested extensively often in adversarial environments before being declared safe for high-stakes applications [44].

Across each paradigm, traditional, chaos-based, and machine learning–driven cryptanalysis consistently exposes the tension between efficiency, randomness, and real-world security demands. Traditional algorithms are well-understood but predictable under determined inspection. Chaos-based methods push unpredictability further but remain sensitive to parameter leakage and finite-precision pitfalls. ML-based PRNGs offer remarkable adaptability and statistical performance yet risk vulnerabilities tied to model extraction, adversarial training, and the absence of rigorous mathematical proofs.

In practice, cryptanalysts continue devising specialized attacks for each category, underscoring the importance of defensive strategies like robust seeding, parameter secrecy, cryptographic post-processing, and continual validation. Ultimately, ongoing research toward hybrid designs and the integration of formal cryptanalysis in neural or chaotic settings may hold the key to PRNGs that can withstand sustained, systematic cryptanalytic efforts [7].

Deploying ML-based PRNGs in sensitive applications raises some ethical and practical considerations. The trustworthiness of randomness underpins fairness and security in many systems (lotteries, encryption, scientific experiments). If an ML-based PRNG has an undetected flaw, the impact could be severe. For example, an encryption system could be weakened without anyone realizing it because the randomness source was assumed to be secure. Ethically, developers have a responsibility to ensure that any AI-driven component (including PRNGs) is thoroughly vetted and monitored. There is also the aspect of accountability: if a cryptographic breach occurs due to an ML-generated sequence being predictable, who is accountable? The complexity of the model can make it hard to assign blame or to understand the failure. In applications like online gambling or lotteries, using an opaque ML-based RNG might lead to public mistrust, even if it’s technically sound, because stakeholders cannot easily verify its fairness. Transparency, or at least rigorous certification by independent parties, will be key in such domains.

Another ethical aspect is the potential for bias. While randomness by definition should be free of bias, a learned model might inadvertently incorporate biases from its training setup. For instance, if it was trained mostly to output certain patterns, it might unknowingly favor those. This is more relevant for pseudo-randomness when used in simulations or procedural generation (e.g., AI-based RNG in game content generation) – biases could skew results. Ensuring a broad and unbiased training input (potentially combining multiple randomness sources, including quantum or hardware randomness if available, to train the model) could mitigate this.

Finally, one might consider the ethical use of resources: training a large model to do what a few lines of code could already do (generate random numbers) might seem wasteful. In a time where energy efficiency is important, justifying the use of heavy computation for PRNGs requires that it offers a clear benefit (like significantly better security). This isn’t a traditional ethical issue, but it’s a practical one when considering deploying ML at scale.

4.6 Future Research Directions

The convergence of traditional, chaos-based, and ML-based PRNG research opens several promising paths. Going forward, researchers should aim to combine the strengths of these approaches while mitigating their weaknesses.

One challenge for ML-based PRNGs is their computational cost. Future work can focus on optimizing neural PRNG models for speed and low power usage, enabling deployment on IoT and edge devices. Techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and efficient hardware implementations (FPGA or ASIC designs for neural generators) could significantly reduce the gap in performance per bit generated. Recent results in deploying PRNGs on edge AI platforms suggest that even deep models can be trimmed or adapted for real-time use. Similarly, chaos-based generators can be optimized through digital hardware design or by identifying simpler chaotic functions that still provide strong randomness. Achieving near-real-time ML-based randomness without heavy hardware will broaden the applicability of these methods.

Rather than view the three categories in isolation, future PRNG designs might integrate them to leverage complementary advantages. For example, a hybrid generator could use a fast classical PRNG as a backbone and then feed its output into a chaotic or neural network transformation to “randomize the random”, adding an extra layer of nonlinearity and complexity to eliminate any residual structure. Conversely, chaos could be used as an inspiration for network design (e.g., neural networks that emulate chaotic maps) or as part of the training regime for ML models. Pasqualini and Parton [8] hint that their reinforcement learning formulation scales better with recurrent structures, which could be combined with chaos-based state updates to extend the period and complexity. There is also potential in evolutionary algorithms or genetic programming to evolve new PRNG algorithms (including neural network architectures) that human designers might not conceive, blending human insight with automated search. Additionally, a two-stage system could be envisioned: one stage (possibly chaos-based or classical) provides a stream of entropy, which a second stage (ML-based) adapts or enhances. This might ensure that even if one stage has weaknesses, the combination remains robust. Coupling mechanisms (such as feeding back output to adjust parameters on the fly) could also create a moving-target PRNG that is harder to analyze or predict. The challenge in hybrid approaches will be to keep the designs analyzable, hence balancing complexity with transparency.

As ML components become more common in PRNG design, improving their explainability will be crucial. Future research may explore interpretable ML models for randomness, For instance, using smaller networks with structure that can be mathematically related to known PRNG constructs. Another approach is to develop theoretical frameworks for analyzing the randomness of neural networks. This could involve treating a neural generator as a high-dimensional nonlinear dynamical system and studying its behavior with tools from chaos theory or information theory. By bridging the gap between the black-box nature of ML and the analytical rigor of traditional PRNG theory, we can build trustworthy random generators. Efforts like the adversarial training by De Bernardi et al. [5] highlight one path: using one part of the model to test another. Extending this, research could integrate real-time statistical testers or predictors into the PRNG system that continually ensure the output has no detectable patterns (an idea of self-monitoring PRNGs). Moreover, publishing negative results (e.g., discovered weaknesses of ML-based PRNGs) will be as important as positive results, to truly understand the failure modes and guide the design of explainable models.

Perhaps the most significant future direction is the rigorous cryptographic evaluation of novel PRNGs. For chaos-based and ML-based generators to be adopted in security-sensitive applications, they must undergo extensive testing beyond standard statistical suites. This includes cryptanalytic attacks: attempting to predict outputs, find correlations, or recover seeds using advanced methods. ML-based PRNGs present a new frontier for cryptanalysis—attackers might use machine learning themselves to find shortcuts or patterns. Future studies should simulate such scenarios: e.g., training a neural network to predict another neural network’s outputs, or using evolutionary strategies to search for weak seeds in a chaotic PRNG. In addition, formal proofs or reductionist security arguments (even limited ones) would greatly enhance confidence. This might involve proving that an ML-based PRNG, under certain assumptions, is equivalent to a known secure construction or does not reduce to a simpler predictable process. Validation standards may need to evolve as well. Just as the community developed the NIST test suite for statistical randomness, one could envision a benchmark suite for cryptographic randomness of ML/chaos PRNGs—including tests for sequence duplication (period finding), spectral analysis, mutual information, and resistance to ML-driven prediction. Cross-disciplinary collaboration between cryptographers, chaos theorists, and ML experts will be vital here. Park, Kim [6] and others have begun to claim cryptographic-level unpredictability for their methods, but independent verification and possibly certification (similar to FIPS certification for PRNGs) will be needed before widespread adoption. Future research might also explore post-quantum aspects of PRNGs—ensuring that the generator’s security holds even against quantum adversaries—an angle where chaotic and ML systems could offer new insights due to their complexity.

In conclusion, the landscape of pseudorandom number generation is witnessing a fruitful expansion from classical algorithms into chaos-inspired methods and machine learning-based models. Machine learning approaches show great promise in addressing traditional limitations. They can automatically discover complex patterns that yield excellent randomness quality and potentially adapt to specific requirements or environment. They offer a form of algorithmic creativity, generating solutions that were not hand-designed. However, this comes with caveats. The increased complexity means we must be cautious and thorough in evaluation. Current limitations such as high computational cost, limited explainability and unproven security profiles highlight that further exploration is necessary before these methods can replace established generators in critical domains. On the other hand, insights from chaotic systems and ML could also enhance traditional PRNGs, for instance by informing new designs that incorporate controlled nonlinearity or by using learning to fine-tune parameters. The trade-offs among the approaches such as simplicity vs. complexity, speed vs. security, theoretical transparency vs. learned adaptability all need to be carefully balanced for each application. Going forward, a synergy of techniques is likely the key. For example, using machine learning to augment or tune classical and chaos-based PRNGs, resulting in hybrids that are both high-performance and reliable. By pursuing the research directions outlined above, the community can work towards PRNGs that are fast, scalable, and statistically perfect like traditional generators, unpredictable and robust like ideal cryptographic sources, and adaptable and intelligent in leveraging new methodologies, ultimately advancing the field of random number generation into a new era of innovation and rigor.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our gratitude to the Computer Science Department of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and the Medical Imaging Technology Department of University for Development Studies for their support of this research.

Funding Statement: This research was not funded by any institution or individual organization.

Author Contributions: Issah Zabsonre Alhassan conceptualized and wrote the original draft; Gaddafi Abdul-Salaam reviewed and edited all versions of the work; Michael Asante supervised the work; Yaw Marfo Missah was part of the supervisors of the work; Alimatu Sadia Shirazu reviewed and proof read the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this work are available in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PRNG | Pseudorandom Number Generator |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LCG | Linear Congruential Generator |

| MT | Mersenne Twister |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| XOR | Exclusive OR |

| LFSR | Linear Feedback Shift Register |

| BBS | Blum Blum Shub |

| LFG | Lagged Fibonacci Generator |

| CSPRNG | Cryptographically Secure Pseudorandom Number Generator |

| RNS | Residue Number System |

| CA | Cellular Automata |

| TPM | Tree Parity Machine |

| BAMNN | Bidirectional Associative Memory Neural Network |

| WOA | Whale Optimization Algorithm |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| SARSA | State-Action-Reward-State-Action |

| PCA | Rincipal Component Analysis |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| K–NN | K–Nearest Neighbor |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| FPGA | Field Programmable Gate Array |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| WGAN | Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network |

| GRNN | General Regression Neural Network |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| DES | Data Encryption Standard |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

References

1. Dahiya P, Shumailov I, Anderson R. Machine learning needs better randomness standards: randomised smoothing and PRNG-based attacks. In: 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24); 2024. [Google Scholar]

2. Bhattacharjee K, Das S. A search for good pseudo-random number generators: survey and empirical studies. Comput Sci Rev. 2022;45(1070):100471. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2022.100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu W, Zhong J, Huan S, Li H, Yang Y. Improved Mersenne Twister random number generator based on FPGA. In: 5th International Conference on Information Science, Electrical, and Automation Engineering (ISEAE 2023). SPIE; 2023. Vol. 12748, p. 932–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Antune B, Mazel C, Hill D, editors. Identifying quality mersenne twister streams for parallel stochastic simulations. In: 2023 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC). San Antonio, TX, USA; 2023. p. 2801–12. doi:10.1109/wsc60868.2023.10408699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. De Bernardi M, Khouzani M, Malacaria Peditors. Pseudo-random number generation using generative adversarial networks. In: ECML PKDD 2018 Workshops: Nemesis 2018, UrbReas 2018, SoGood 2018, IWAISe 2018, and Green Data Mining 2018; 2018 Sep 10–14; Dublin, Ireland: Springer; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-13453-2_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Park S, Kim K, Kim K, Nam C. Dynamical pseudo-random number generator using reinforcement learning. Appl Sci. 2022;12(7):3377. doi:10.3390/app12073377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Okada K, Endo K, Yasuoka K, Kurabayashi S. Learned pseudo-random number generator: WGAN-GP for generating statistically robust random numbers. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0287025. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Pasqualini L, Parton M. Pseudo random number generation: a reinforcement learning approach. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;170:1122–7. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lin C-H, Wu J-X, Chen P-Y, Li C-M, Pai N-S, Kuo C-L. Symmetric cryptography with a chaotic map and a multilayer machine learning network for physiological signal infosecurity: case study in electrocardiogram. IEEE Access. 2021;9:26451–67. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3057586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Saxena D, Cao J. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Comput Surveys. 2021;54(3):1–42. doi:10.1145/3446374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fazliddin N. Random numbers: pseudo-random and true random numbers. Samarali Ta’lim Va Barqaror Innovatsiyalar Jurnali. 2023;1(5):73–81. [Google Scholar]

12. Laia O, Zamzami EM, Larosa FGN, Gea A. Application of linear congruent generator in affine cipher algorithm to produce dynamic encryption. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2019;1361(1):012001. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1361/1/012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dunn WL, Shultis JK. Exploring monte carlo methods. 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128197394/exploring-monte-carlo-methods [Google Scholar]

14. Dunn W, Shultis J. Pseudorandom number generators; 2023. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819739-4.00011-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ali-Pacha H, Hadj-Said N, Ali-Pacha A, Mohamed MA, Mamat M. Cryptographic adaptation of the middle square generator. Int J Electr Comput Eng. 2019;9(6):5615. doi:10.11591/ijece.v9i6.pp5615-5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shcherbyna Y, Kazakova N, Fraze-Frazenko Oeditors. The Mersenne Twister output stream postprocessing. In: III International Scientific and Practical Conference “Information Security and Information Technologies”; 2021 Sep 13; Odesa, Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

17. Lecca C, Zegarra A, Santisteban J. Random number generator based on hopfield neural network with Xorshift and genetic algorithms. In: Mexican International Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2023. p. 283–95. [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1007/978-3-031-47765-2_21. [Google Scholar]

18. Eljadi FMA, Al Shaikhli IFT. Dynamic linear feedback shift registers: a review. In: The 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Muslim World (ICT4M). Kuching, Malaysia; 2014. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

19. Olsson M, Gullberg N. Blum Blum Shub on the GPU [master thesis]. Karlskrona, Sweden: Blekinge Institute of Technology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

20. Laia O, Zamzami E, editors. Analysis of combination algorithm data encryption standard (DES) and Blum-Blum-Shub (BBS). J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021;1898:012017. [Google Scholar]

21. Aldossari H, Mascagni M. Scrambling additive lagged-Fibonacci generators. Monte Carlo Methods Appl. 2022;28(3):199–210. doi:10.1515/mcma-2022-2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Naumenko M. Cryptographically secure Pseudorandom number generators; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://dspace.cuni.cz/handle/20.500.11956/193197. [Google Scholar]

23. Navarro MA, Oliva D, Ramos-Michel A, Morales-Castaneda B, Zaldívar D, Luque-Chang A. A review of the use of quasi-random number generators to initialize the population in meta-heuristic algorithms. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2022;29(7):5149–84. doi:10.1007/s11831-022-09759-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Maksymovych V, Shabatura M, Harasymchuk O, Shevchuk R, Sawicki P, Zajac T. Combined pseudo-random sequence generator for cybersecurity. Sensors. 2022;22(24):9700. doi:10.3390/s22249700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Naik RB, Singh U. A review on applications of chaotic maps in pseudo-random number generators and encryption. Annals Data Sci. 2024;11(1):25–50. doi:10.1007/s40745-021-00364-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Setiadi D-R-I-M, Sutojo T, Rustad S, Akrom M, Ghosal S-K, Nguyen M-T, et al. Single Qubit Quantum Logistic-Sine XYZ-rotation maps: an ultra-wide range dynamics for image encryption. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2161–88. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.063729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Si H. Lorenz attractors: exploring its properties and the application value of chaos theories. Theor Natural Sci. 2024;38:190–5. [Google Scholar]

28. Ouyang Z, Jin J, Yu F, Chen L, Ding L. Fully integrated chen chaotic oscillation system. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc. 2022;2022(1):8613090. doi:10.1155/2022/8613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nagaraj N. The unreasonable effectiveness of the chaotic tent map in engineering applications. Chaos Theory Appl. 2022;4(4):197–204. [Google Scholar]

30. de Hénon JX. Hénon maps: a list of open problems. Arnold Math J. 2024;10(4):585–620. doi:10.1007/s40598-024-00252-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Letellier C, Sendiña-Nadal I, Minati L, Barbot J-P. Flat control law for diffusively y-coupled Rössler systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025;113(13):1–19. doi:10.1007/s11071-025-11005-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Salas Salas AH, Castillo Hernández JE, Martínez Hernández LJ. The duffing oscillator equation and its applications in physics. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021(1):9994967. doi:10.1155/2021/9994967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shafique A, Khan KH, Hazzazi MM, Bahkali I, Bassfar Z, Rehman MU. Chaos and cellular automata-based substitution box and its application in cryptography. Mathematics. 2023;11(10):2322. doi:10.3390/math11102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Alnajim AM, Abou-Bakr E, Alruwisan SS, Khan S, Elmanfaloty RA. Hybrid chaotic-based PRNG for secure cryptography applications. Appl Sci. 2023;13(13):7768. doi:10.3390/app13137768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chopra D, Khurana R. Introduction to machine learning with python. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.benthamdirect.com/content/books/9789815124422. [Google Scholar]

36. Shakya AK, Pillai G, Chakrabarty S. Reinforcement learning algorithms: a brief survey. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;231(7):120495. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Atee HA, Ahmad R, Noor NM, Rahma AMS. Extreme learning machine based sub-key generation for cryptography system; 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/83531933.pdf. [Google Scholar]

38. Lokesh S, Kounte MR, editors. Chaotic neural network based pseudo-random sequence generator for cryptographic applications. In: 2015 International Conference on Applied and Theoretical Computing and Communication Technology (iCATccT). Davangere, India:IEEE; 2015. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/icatcct.2015.7456845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Machicao J, Bruno OM. Improving the pseudo-randomness properties of chaotic maps using deep-zoom. Chaos: Interdiscip J Nonlinear Sci. 2017;27(5):1–20. [Google Scholar]

40. Gayoso CA, Arnone L, González C, Moreira JC, editors. A general construction method for Pseudo-random number generators based on the residue number system. In: 2019 XVIII Workshop on Information Processing and Control (RPIC). Salvador, Brazil: IEEE; 2019. p. 25–30. doi:10.1109/rpic.2019.8882147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Alloun Y, Azzaz MS, Kifouche A, Kaibou R, editors. Pseudo random number generator based on chaos theory and artificial neural networks. In: 2022 2nd International Conference on Advanced Electrical Engineering (ICAEE). Constantine, Algeria: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

42. Hu G, Peng J, Kou W. A novel algorithm for generating pseudo-random number. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2019;12(2):643–8. doi:10.2991/ijcis.d.190521.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Reddy MI, Kumar AS, Reddy KS. A secured cryptographic system based on DNA and a hybrid key generation approach. Biosystems. 2020;197(12):104207. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2020.104207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Pasqualini L, Parton M. Pseudo random number generation through reinforcement learning and recurrent neural networks. Algorithms. 2020;13(11):307. doi:10.3390/a13110307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Patel S, Thanikaiselvan V. Latin square and machine learning techniques combined algorithm for image encryption. Circuits Syst Signal Process. 2023;42(11):6829–53. doi:10.1007/s00034-023-02427-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Naveena V, Satyanarayana DS, Mt Scholar. Symmetric cryptography using neural networks. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2019;06(8):1556–8. [Google Scholar]

47. Al-Daraiseh A, Sanjalawe Y, Al-E’mari S, Fraihat S, Bany Taha M, Al-Muhammed M. Cryptographic grade chaotic random number generator based on tent-map. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2023;12(5):73. doi:10.3390/jsan12050073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Kim H, Kwon Y, Sim M, Lim S, Seo H, editors. Generative adversarial networks-based pseudo-random number generator for embedded processors. In: International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology. Cham: Springer; 2020. Vol. 12593. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68890-5_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yeniçeri R, Kilinç S, Yalçin ME. Attack on a chaos-based random number generator using anticipating synchronization. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 2015;25(2):1550021. doi:10.1142/s0218127415500212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.