Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluating the Level of Compliance with the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR): Insights from Organizations across Key Sectors

1 Centre for Cyberspace Studies, Nasarawa State University, Keffi, 911019, Nigeria

2 Department of Physics, Nasarawa State University, Keffi, 911019, Nigeria

* Corresponding Author: Asere Gbenga Femi. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 377-394. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.069185

Received 17 June 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Effective data protection frameworks are vital for safeguarding personal information, fostering digital trust, and ensuring alignment with global standards. In Nigeria, the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR), administered by the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), constitutes the nation’s primary privacy framework, harmonized with principles of the European Union’s GDPR. This study evaluates NDPR compliance across six strategic sectors; finance, telecommunications, education, health, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), and the public sector using a mixed-methods design. Data from 615 respondents in 30 organizations were collected through surveys, interviews, and document analysis. Findings reveal notable sectoral disparities: finance and telecommunications demonstrate high compliance due to regulatory pressure and strong technical capacity, while SMEs and public institutions exhibit lower adherence. Compliance, monitoring, and awareness were assessed against NDPR benchmarks, including lawful processing, consent protocols, and breach response procedures. Regression results indicate that NDPR compliance, staff training, and cybersecurity investment significantly predict enhanced cybersecurity outcomes, though perfect correlations raise concerns about instrument validity. Weak enforcement, with limited penalties or legal actions, undermines the regulation’s deterrent effect. Drawing on Institutional and Deterrence Theories, the study identifies legal and structural gaps in the NDPR and proposes reforms, stronger oversight, and sector-specific interventions. These findings contribute to debates on regulatory effectiveness and offer actionable strategies for improving data governance and cybersecurity resilience in Nigeria.Keywords

The rapid digitization of organizational processes has transformed how data is collected, processed, and stored in Nigeria. As digital technologies continue to shape economic and governance systems, personal data has become increasingly vulnerable to misuse, unauthorized access, and cyber threats [1]. Recognizing these risks, the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) was introduced in 2019 by the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) as the country’s primary legal framework for safeguarding personal data. The regulation mandates lawful processing, consent management, data minimization, and accountability mechanisms, aligning broadly with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation [2–4]. While the NDPR has generated momentum in formalizing data protection practices, compliance across sectors remains inconsistent. Financial services and telecommunications firms heavily regulated and well-resourced have made notable progress in implementation [1]. However, sectors such as health, education, and SMEs face significant barriers, including limited awareness, financial constraints, and lack of technical capacity [5–7]. These disparities raise concerns about the effectiveness and inclusivity of the regulation. Moreover, the NDPR’s legal authority is contested due to its origin as a subsidiary legislation, which lacks the statutory force typically expected of foundational rights-based frameworks [1].

A key gap in the existing literature is the lack of empirical research that evaluates NDPR compliance from both sectoral and legal perspectives. While several studies report awareness levels or policy presence [8,9], few examine how compliance is operationalized in practice, or how the clauses of the NDPR translate into measurable outcomes. Critical regulatory elements such as breach notification, data audits, and consent protocols are seldom analyzed in relation to real-world organizational behaviors. Furthermore, there is limited scholarly discussion on the practical enforcement of the NDPR by NITDA, including its use of penalties, audits, or court actions to encourage adherence [3,10].

Another overlooked aspect in current studies is the weak integration of theoretical frameworks that explain why organizations comply or fail to comply with data protection laws. While Institutional Theory and Deterrence Theory have been introduced in compliance literature [11,12], they are not consistently applied to Nigeria’s regulatory context. There is also a lack of studies testing these frameworks empirically to understand how regulatory pressure, perceived sanctions, and internal culture drive or deter compliance [13]. The complex interplay between regulation, organizational readiness, and cybersecurity maturity remains insufficiently understood.

This research addresses these deficiencies by evaluating NDPR compliance across 30 organizations and 615 respondents representing diverse sectors. It uses a mixed-methods design that includes structured surveys, qualitative interviews, and document analysis. The study also explicitly operationalizes constructs like “compliance,” “monitoring,” and “awareness” using specific NDPR clauses on lawful processing, consent, and data subject rights [4]. By applying Institutional and Deterrence Theory, the research investigates how legal mandates, organizational behavior, and enforcement incentives interact to shape compliance outcomes in Nigeria.

The findings are expected to offer a more grounded understanding of the drivers and barriers of NDPR compliance. By bridging the gap between regulatory intention and operational reality, this study contributes to the ongoing discourse on data governance in Nigeria. It also provides practical insights for NITDA, policymakers, and organizational leaders seeking to enhance legal enforcement, reduce sectoral disparities, and build a resilient data protection ecosystem that can support Nigeria’s digital economy [14,15].

The Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR), enacted in 2019 by the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), serves as a foundational framework for safeguarding personal data in Nigeria. It aligns with global standards such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union, focusing on principles like data minimization, purpose limitation, consent, transparency, and accountability [13]. Key components of NDPR include data subject rights, obligations of data controllers and processors, and mechanisms for enforcement. Organizational compliance with data protection regulations is multifaceted, often influenced by institutional commitment, awareness, technological readiness, and sector-specific risk exposure [16]. Within this framework, compliance can be evaluated through indicators such as the presence of a data protection officer, staff training programs, data audit mechanisms, and response strategies for data breaches [17]. Several empirical studies have examined the state of compliance with the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) across various sectors in Nigeria, revealing a pattern of growing awareness but inconsistent implementation. Ref. [9] found that although awareness of the NDPR among Nigerian banks was relatively high, actual compliance was only moderate due to challenges related to limited technical infrastructure and insufficient human resource capacity. In the healthcare sector, Ref. [5] reported that while most institutions in Lagos had some form of data security, only a small fraction had implemented NDPR-compliant policies and procedures, suggesting a significant gap between awareness and practical adherence.

Similarly, Ref. [7] studied universities in Nigeria and highlighted a widespread lack of structured data governance frameworks, despite the sensitive nature of student data. In the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), Ref. [6] revealed that most lacked even basic awareness of the NDPR, let alone the capacity for full compliance, primarily due to limited financial and human resources. In the same vein [18] emphasized the importance of aligning Information and Communication Technology (ICT) governance with legal and regulatory requirements, arguing that this alignment significantly contributes to improved compliance. The role of third-party data processors was examined by [19], who stressed the need for organizations, particularly in fintech and e-commerce, to embed data protection clauses in their contracts as part of broader compliance strategies. While Ref. [20] found that multinational corporations operating in Nigeria demonstrated a higher level of compliance, largely due to their familiarity with global data protection regimes like the GDPR. However, in the telecommunications sector, Ref. [21] identified a wide discrepancy between documented policies and actual practices, especially concerning user consent and breach notification protocols.

Enforcement challenges were highlighted by [1], who argued that regulatory oversight by NITDA was relatively weak in the initial stages of NDPR implementation, thereby limiting its effectiveness. Ref. [13] explored the influence of organizational culture, finding that proactive leadership and an ethical workplace environment positively influenced NDPR compliance. Also, Ref. [22] pointed to the lack of legal training and awareness campaigns within public institutions, advocating for broader sensitization efforts to improve adherence to the regulation. Lastly, Ref. [10] assessed compliance in the education sector and noted that while many institutions had formal policies in place, actual implementation was poor due to budget constraints and limited understanding of data protection requirements. These empirical studies collectively highlight sector-specific challenges, resource limitations, and the critical role of institutional culture and regulatory enforcement in shaping the level of NDPR compliance in Nigeria.

This study is grounded in Institutional Theory and Deterrence Theory. Institutional theory explains how organizational behaviors are shaped by the regulatory, normative, and cognitive pressures in their environment [11]. In the NDPR context, organizations are influenced by the regulatory framework (NDPR requirements), professional norms (industry standards), and internal values (organizational culture). Complementing this is Deterrence Theory, which postulates that compliance behavior increases when potential violators perceive a high probability of detection and severe penalties [12]. The NDPR’s enforcement mechanism, including fines and sanctions, is designed to deter non-compliance and encourage adherence. Together, these theories provide a robust lens for evaluating why and how organizations comply with data protection laws. The reviewed literature highlights significant disparities in NDPR compliance across different sectors in Nigeria, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive study. While sectors like banking and multinational corporations demonstrate higher awareness and partial adherence to data protection standards, others such as SMEs, healthcare, and education face substantial challenges due to limited resources, low awareness, and poor governance frameworks. This inconsistency calls for a cross-sectoral investigation to provide a clearer picture of the national compliance landscape.

Additionally, many organizations have NDPR policies in place, but implementation is often weak or inconsistent. The gap between policy and actual practice, as noted in sectors like education and telecommunications, makes it necessary to empirically assess not just the existence of policies but how effectively they are being executed. The literature also points to weak regulatory enforcement by NITDA, particularly in the early years of NDPR rollout. This lack of effective oversight limits compliance, suggesting a need for research that evaluates how enforcement has evolved and its impact on organizations. Moreover, organizational factors such as leadership, culture, and employee attitudes appear to play a critical role in shaping compliance behavior, yet these internal elements are underexplored. Furthermore, the role of third-party data processors, especially in fintech and e-commerce, introduces additional layers of risk and complexity that are not sufficiently addressed in current studies. Lastly, the limited scope and fragmented nature of existing research highlight the need for a unified, empirical, and comparative study that can inform more robust data protection policies and practices in Nigeria. This research will therefore contribute valuable insights for policymakers, regulators, and organizations aiming to strengthen data privacy frameworks in line with the NDPR.

This study adopted a mixed-methods research design to comprehensively assess organizational compliance with the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) across key sectors. The design combined quantitative and qualitative approaches to facilitate both breadth and depth in data collection and analysis. The quantitative component measured the prevalence and patterns of compliance, while the qualitative strand provided contextual understanding of organizational behavior, regulatory perceptions, and sectoral challenges.

Population and Sampling Technique: The target population comprised organizations operating in Nigeria’s Financial Services, Telecommunications, Health, Education, E-commerce, Manufacturing, Public Sector, and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). A stratified random sampling technique was employed to ensure sectoral representation and diversity of organizational size and structure. Stratification was done based on industry sector, after which simple random sampling was used to select at least three to five organizations from each stratum. Within each selected organization, responses were collected from compliance officers, IT/security managers, and data protection officers, yielding a total of 615 valid responses from 30 organizations. This sampling strategy was designed to address sectoral disparities and minimize bias in respondent selection.

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures: Three data collection instruments were employed:

• Structured Questionnaire: The survey instrument contained closed-ended items designed to measure key constructs such as compliance, awareness, monitoring, and cybersecurity investment. These constructs were operationalized in alignment with the NDPR, particularly in relation to Articles 2.1–2.10, which define lawful processing, data subject consent, and breach notification requirements [4]. For example, “compliance” was measured using items assessing data audit frequency, presence of a data protection officer, lawful processing practices, and adherence to consent protocols.

• Semi-Structured Interviews: A subset of 15 participants, including regulators and industry experts, were interviewed to explore perceptions of NDPR enforceability, legal awareness, institutional culture, and practical challenges to implementation.

• Document Analysis: Internal policy documents, NDPR compliance audit reports, and publicly available NITDA enforcement records were analyzed to validate organizational claims and triangulate findings.

Data Analysis Techniques: Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics via Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Descriptive statistics (means, frequencies, percentages) were used to summarize awareness, compliance levels, and monitoring practices. Inferential techniques included regression analysis to identify predictors of compliance and cybersecurity performance, and chi-square tests to examine sectoral differences. Each variable was tested for reliability using Cronbach’s alpha, and Correlation matrices were generated to assess relationships between constructs, though caution was exercised in interpreting unusually high or perfect correlations. Qualitative data from interviews were transcribed and subjected to thematic analysis using NVivo. Coding focused on themes related to legal awareness, institutional behavior, regulatory oversight, and barriers to compliance. These insights were integrated with quantitative results to provide contextual interpretation and policy-relevant conclusions.

Ethical Considerations: This research adhered to ethical standards governing research involving human participants. Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Centre for Cyberspace Studies Research Ethics Committee, Nasarawa State University. All participants gave informed consent, and data confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing organizational identifiers and individual responses. Data collected will be stored securely and made available to qualified researchers upon request in accordance with NDPR guidelines.

Legal Analysis of NDPR Clauses and Enforcement Mechanisms

The Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR), issued in January 2019 by the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), provides the statutory foundation for data protection in Nigeria. While it represents a significant policy intervention, its legal status as a subsidiary legislation rather than a formal Act of the National Assembly raises important questions about its enforceability and constitutional grounding.

1. Legal Status and Scope: The NDPR was promulgated under Section 6(c) of the NITDA Act 2007, which authorizes NITDA to issue guidelines for electronic governance and monitoring. However, the NDPR does not stem from a primary statute and lacks the legislative authority that characterizes Acts of Parliament. This legal structure limits the regulation’s strength in terms of judicial enforcement, particularly when tested in courts. It also raises questions about the procedural legitimacy of its sanctions, which may be challenged as ultra vires unless backed by a specific legislative mandate [8].

2. Key Compliance Clauses: The NDPR imposes several legal obligations on data controllers and processors, including:

• Lawful Processing (Article 2.1): Requires personal data to be collected and processed with consent or for lawful purposes. This mirrors Article 6 of the GDPR and mandates organizations to maintain a legal basis for processing.

• Consent and Data Subject Rights (Articles 2.2–2.3): Establishes the requirement for clear, informed consent and allows data subjects to withdraw consent, request access to their data, and demand rectification or erasure.

• Data Security Measures (Article 2.6): Obligates organizations to implement technical and organizational measures to safeguard personal data, including breach prevention protocols and data encryption.

• Audit and Filing Obligations (Article 4.1): Requires data controllers to submit an annual data audit report by March 15 of each year, disclosing their data processing activities and compliance posture.

Despite the robustness of these clauses on paper, many organizations particularly SMEs and public institutions remain unaware of or non-compliant with these obligations due to the technical and legal complexity of the regulation [15].

3. Enforcement Mechanisms and Sanctions: NITDA, as the primary regulator, is empowered to enforce NDPR provisions through audits, investigations, and penalties. The Implementation Framework (2019) complements the NDPR by outlining enforcement procedures, including:

• Administrative Sanctions (Clause 11): These include fines up to ₦10 million or 2% of annual gross revenue, whichever is higher, for data breaches or failure to meet minimum compliance standards.

• Audit Requirements (Clause 8): Organizations are subject to compliance audits, and non-cooperation may trigger sanctions or public exposure.

However, enforcement remains weak. As of 2023, there are few publicly reported cases of administrative fines or judicial proceedings initiated by NITDA. The absence of a Data Protection Authority (DPA) with independent prosecutorial powers, coupled with limited institutional capacity, undermines effective enforcement [13]. Additionally, the lack of synergy with other statutory regulators such as the Economic and Financial Crime Commission (EFCC) under the Cybercrime Act 2015 creates overlapping jurisdictions and regulatory gaps.

4. Constitutional and Jurisprudential Context: From a constitutional perspective, the NDPR derives indirect legitimacy from Section 37 of the 1999 Constitution, which guarantees the right to privacy. However, this right has not been explicitly linked to data protection in judicial decisions, and there is limited Nigerian jurisprudence interpreting the NDPR in relation to Section 37. Without court-tested precedents, organizations lack clarity on the practical implications of non-compliance or the risk of civil litigation from affected data subjects.

5. Gaps and Recommendations for Reform: The study finds that the absence of enforcement actions, limited public awareness of NDPR clauses, and vague legal thresholds for determining “compliance” diminish the regulation’s deterrent effect. Terms such as “fully compliant” or “non-compliant” are often interpreted from a managerial perspective rather than anchored in the NDPR’s legal provisions, creating inconsistencies in how organizations assess themselves.

To enhance effectiveness:

• The NDPR should be codified into a full Data Protection Act through legislative action.

• A Data Protection Authority (DPA), independent of NITDA, should be established to oversee enforcement.

• A compliance benchmark framework should be published with clear minimum legal requirements for organizations, including breach notification timelines and consent standards.

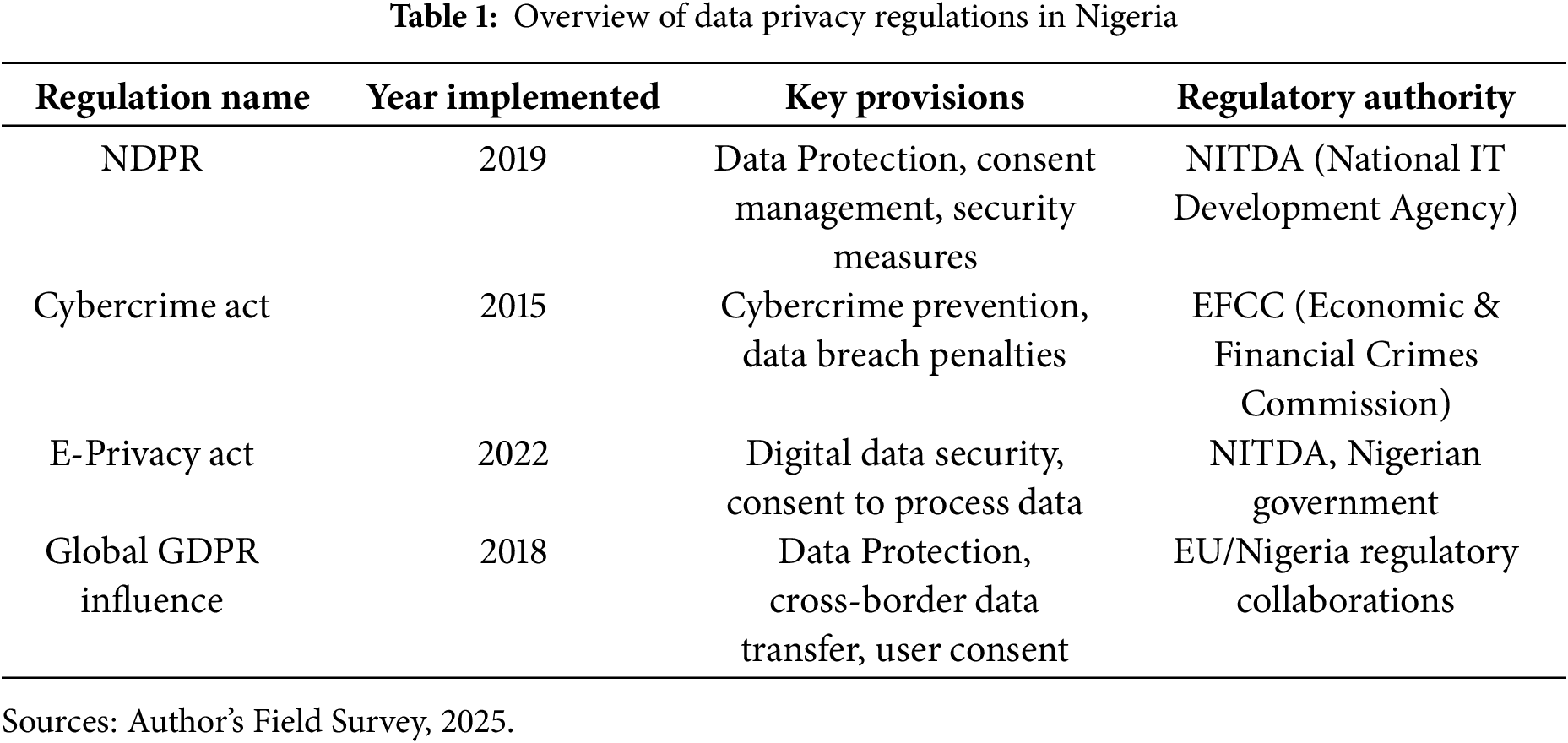

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of Nigeria’s key data privacy-related regulations, including the NDPR (2019), Cybercrime Act (2015), and the more recent E-Privacy Act (2022), alongside the influence of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The NDPR, issued by NITDA, stands out as Nigeria’s first dedicated data protection regulation, emphasizing principles of consent management, data minimization, and security controls. In contrast, the Cybercrime Act, while not a data protection law per se, introduces punitive measures for unauthorized data access and cyberattacks. The E-Privacy Act, which came into force in 2022, builds on the NDPR by extending protection to digital communication platforms and requiring more specific consent protocols for online data processing. This layered regulatory environment highlights a fragmented but evolving legal landscape. While each regulation addresses a different aspect of data security, the absence of a unified statutory framework leads to overlaps and jurisdictional ambiguity. This finding supports previous literature [1,20] which noted a lack of coherence among Nigeria’s data governance laws. The presence of GDPR as an influencing model also indicates Nigeria’s ambition to align with international best practices, yet gaps in enforcement and capacity have hindered this aspiration. Therefore, the table serves not only as a reference of existing instruments but also as evidence of the regulatory complexity organizations must navigate when attempting to comply with the NDPR.

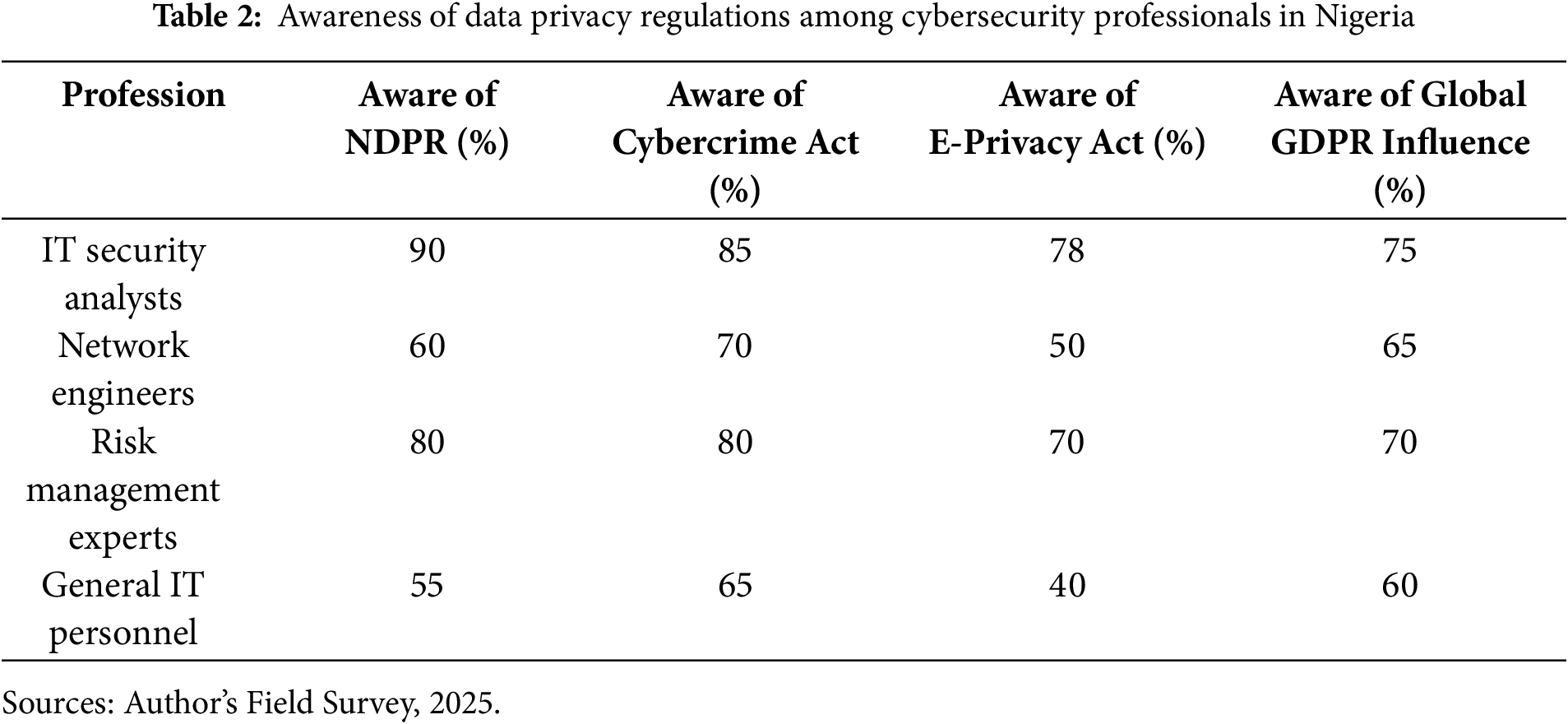

Table 2 presents the percentage of professionals in different IT-related roles who are aware of key data protection regulations in Nigeria namely the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR), the Cybercrime Act (2015), the E-Privacy Act (2022), and the influence of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on Nigerian frameworks.

1. NDPR Awareness: IT Security Analysts (90%) and Risk Management Experts (80%) report the highest levels of NDPR awareness. This is expected, given their roles in regulatory compliance, cybersecurity planning, and institutional risk mitigation. These professionals are typically responsible for interpreting and implementing data governance policies, making them the most exposed to data protection frameworks. Network Engineers (60%) and General IT Personnel (55%) show lower awareness levels, suggesting a knowledge gap between technical implementers and compliance strategists. This disparity highlights the need to integrate regulatory education into general IT roles, especially in organizations where engineers and developers manage user data directly.

2. Cybercrime Act Awareness: Awareness of the Cybercrime Act (2015) is slightly more evenly distributed, with Risk Managers and Security Analysts scoring 80%–85%, and Network Engineers and IT Personnel showing moderate awareness (65%–70%). The Cybercrime Act, being more widely enforced and discussed in cybersecurity training, may have better visibility among general IT professionals.

3. E-Privacy Act Awareness: Awareness of the E-Privacy Act (2022) is generally lower across all roles, with IT Security Analysts (78%) again at the top, followed by Risk Managers (70%). Network Engineers (50%) and General IT Personnel (40%) lag behind, likely due to the Act’s recent introduction and the limited availability of structured training or sensitization efforts targeting broader IT staff. This suggests the E-Privacy Act is still in the early stages of sector-wide adoption.

4. Global GDPR Influence: The influence of GDPR, which serves as a global benchmark for data protection, is acknowledged most by Security Analysts (75%) and Risk Managers (70%), reflecting their exposure to international standards and best practices. Awareness among Network Engineers (65%) and General IT Staff (60%) is fair but not optimal, indicating that global regulatory trends have yet to be fully mainstreamed into Nigeria’s IT workforce.

Key Implications

The table clearly illustrates that regulatory awareness is profession-dependent, with strategic and compliance-focused roles showing stronger familiarity than generalist or technically-oriented roles. This gap poses a compliance risk, as many data handling decisions are made by those with limited understanding of regulatory obligations. It also confirms the study’s findings that awareness is a critical driver of NDPR compliance, and that targeted capacity-building efforts should extend beyond compliance officers to include IT personnel at all operational levels.

To close this gap, the study recommends:

• Mandatory regulatory training for all IT roles within data-intensive organizations.

• Cross-functional compliance teams that include both technical and legal personnel.

• Government and industry partnerships to mainstream E-Privacy and GDPR concepts into national IT certification programs.

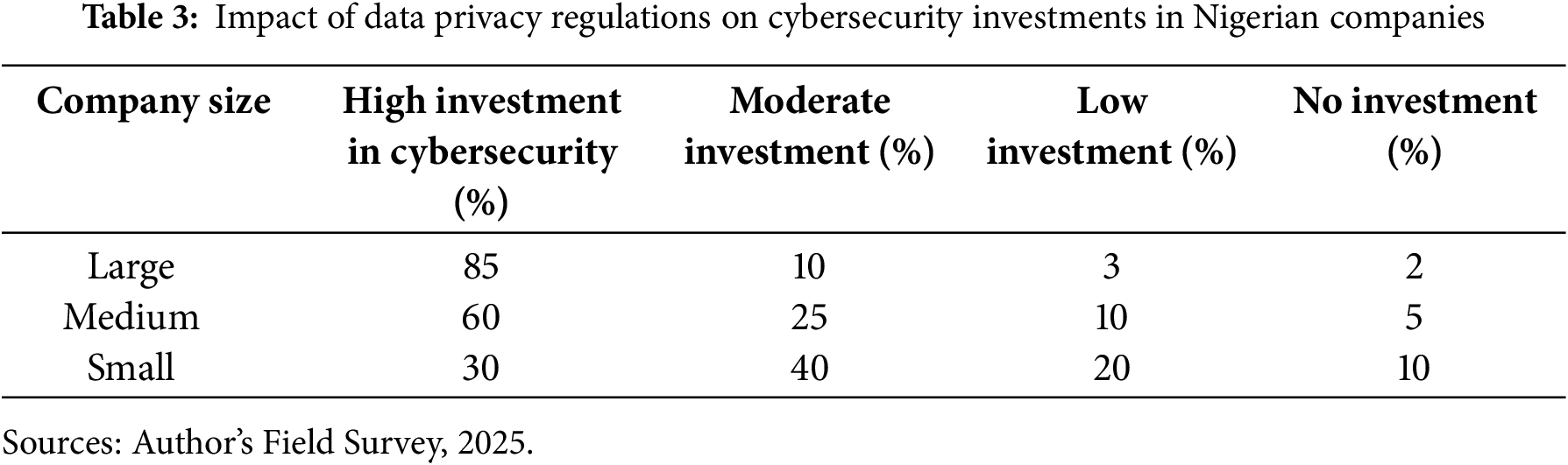

Table 3 explores how data privacy regulations particularly the NDPR influence cybersecurity investment levels across organizations of varying sizes. The data reveal a positive relationship between organizational size and cybersecurity investment, with 85% of large companies reporting high investment levels compared to only 30% of small enterprises. Medium-sized companies show a moderate profile, with 60% indicating high investment. This disparity underscores the resource-driven nature of regulatory compliance, where larger organizations are better positioned to allocate funds for security infrastructure, risk audits, compliance officers, and staff training. Conversely, smaller firms face constraints in meeting NDPR requirements, often due to limited budgets, technical expertise, and absence of structured compliance programs [6,23]. The table also reflects the study’s broader finding that SMEs and public institutions struggle the most with NDPR adherence, reinforcing the need for differentiated regulatory strategies and targeted support for resource-constrained organizations. The link between compliance incentives and financial capacity further validates the study’s application of Deterrence Theory: organizations with fewer resources are less likely to comply unless motivated by external oversight or assistance. Moreover, the lack of enforcement actions noted elsewhere in the study likely contributes to the low investment rates among small firms, as the perceived risk of regulatory penalties remains low.

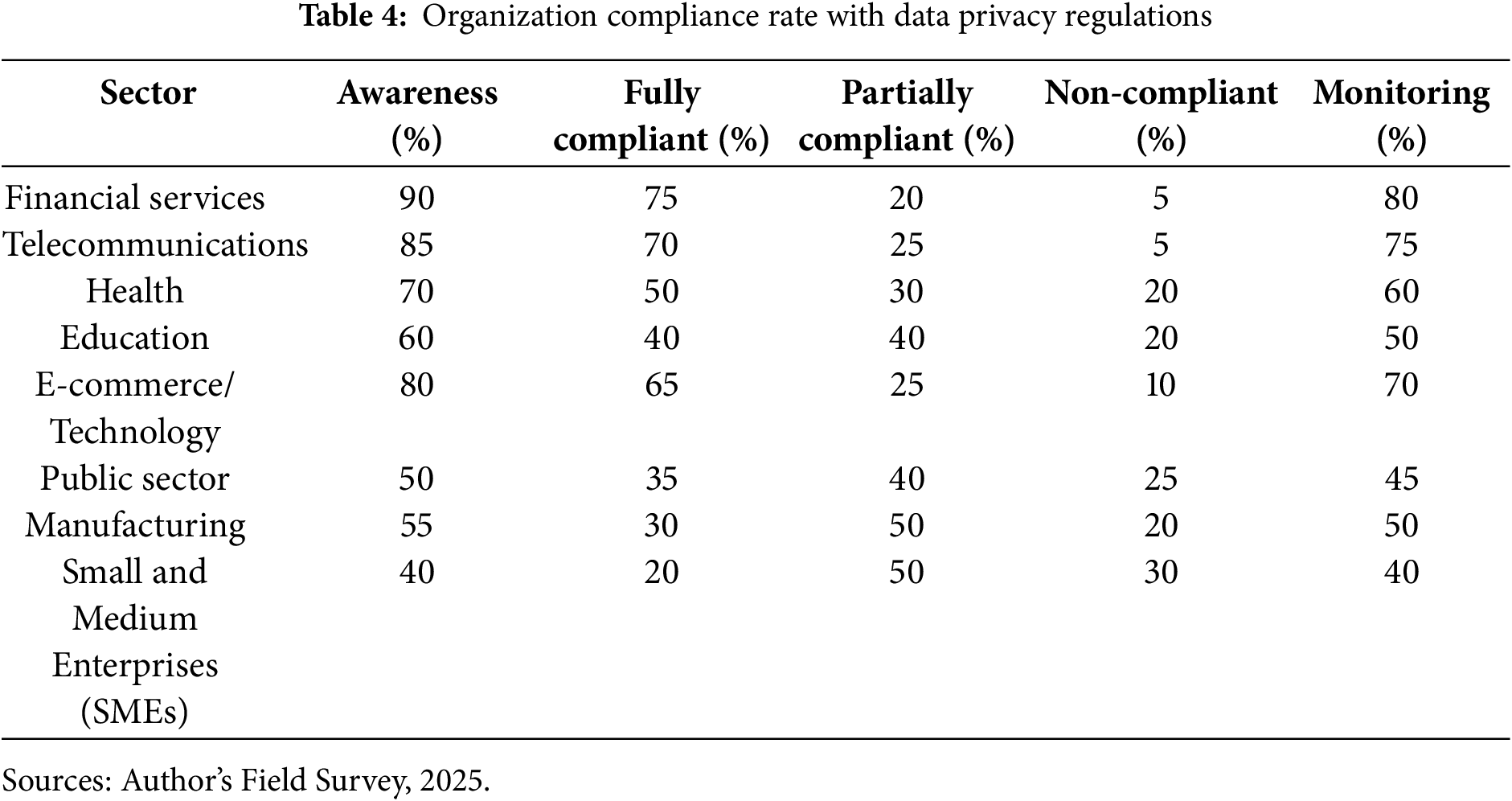

Table 4 presents a comparative overview of NDPR compliance indicators across eight key organizational sectors in Nigeria. The indicators include awareness, full compliance, partial compliance, non-compliance, and monitoring mechanisms. These variables collectively provide a comprehensive picture of how well each sector understands, implements, and internally enforces data protection obligations.

1. Awareness: The Financial Services (90%) and Telecommunications (85%) sectors report the highest levels of awareness of the NDPR. This is expected, as these sectors are subject to strict oversight from regulatory bodies like the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), which have adopted NDPR principles into their operational frameworks. Conversely, SMEs (40%) and the Public Sector (50%) demonstrate the lowest awareness levels, highlighting a major regulatory communication and engagement gap in less-structured or under-resourced environments.

2. Full Compliance: Full compliance which indicates adherence to the NDPR’s core requirements such as lawful processing, consent protocols, data audits, and breach notifications is most pronounced in the Financial Services (75%), Telecommunications (70%), and E-commerce/Technology (65%) sectors. These sectors are more likely to have dedicated compliance teams, legal advisors, and automated systems for data governance. In stark contrast, only 20% of SMEs and 35% of Public Sector organizations are fully compliant, reflecting structural and institutional challenges.

3. Partial and Non-Compliance: High partial compliance rates in sectors like Manufacturing (50%), SMEs (50%), and Education (40%) suggest that many organizations have begun implementing certain NDPR measures but lack the comprehensive frameworks or documentation to achieve full compliance. Alarmingly, non-compliance is highest among SMEs (30%) and Public Sector institutions (25%), revealing systemic obstacles such as lack of technical resources, regulatory fear, and minimal training. These figures support prior findings from scholars like [1,18], who emphasized the need for sector-specific enforcement strategies.

4. Monitoring: Monitoring capability, which refers to an organization’s ability to internally evaluate and track compliance (e.g., through audits, reports, or data governance teams), follows a similar pattern. Financial Services (80%) and Telecommunications (75%) lead, reflecting strong internal control systems and higher compliance maturity. By contrast, SMEs (40%) and the Public Sector (45%) lag behind, which may explain their lower full compliance rates since poor monitoring directly impairs accountability and regulatory readiness.

Summary Implications

The results in Table 4 demonstrate that compliance with the NDPR is strongly influenced by sectoral characteristics such as regulatory exposure, financial capacity, and digital maturity. Highly regulated and digitally dependent sectors tend to perform better, while under-resourced or less-regulated sectors struggle with both implementation and enforcement. These disparities emphasize the need for a differentiated compliance support model in Nigeria’s data protection ecosystem where sectors like SMEs, education, and public institutions receive customized guidance, technical assistance, and possibly financial incentives to align with NDPR standards.

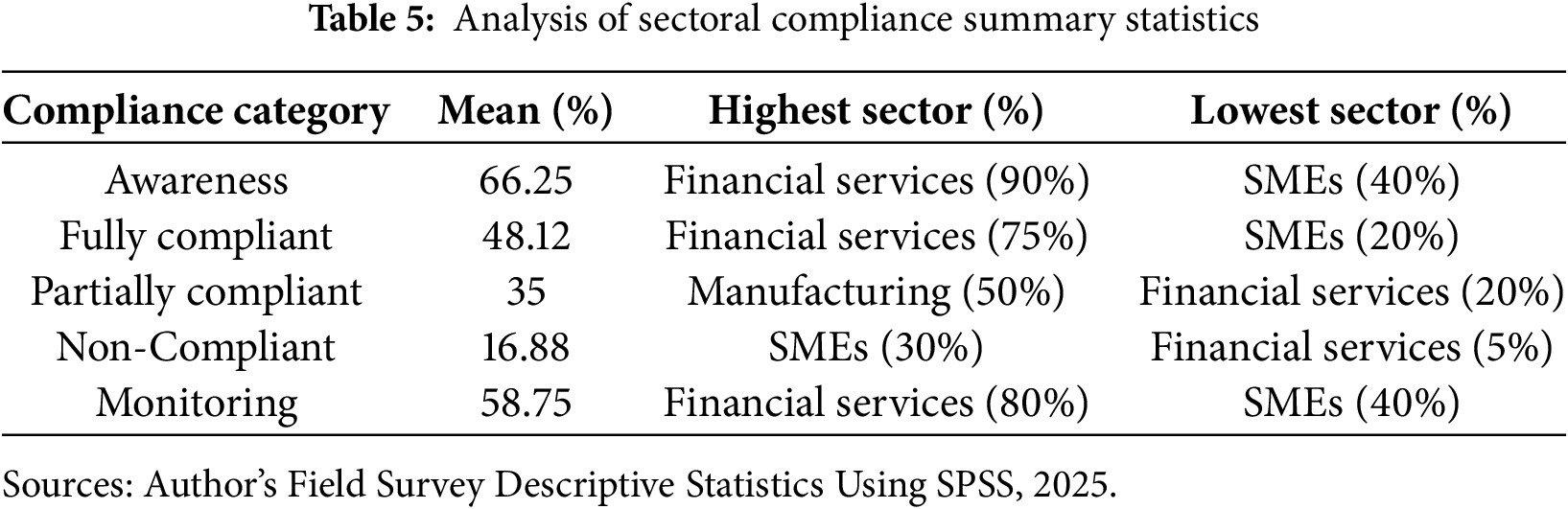

Table 5 provides a consolidated view of sectoral performance across five NDPR-related compliance categories: Awareness, Full Compliance, Partial Compliance, Non-Compliance, and Monitoring. Each metric is evaluated by calculating the mean performance across sectors, alongside the highest and lowest performing sectors.

1. Awareness (Mean = 66.25%): Awareness of the NDPR is relatively high on average, with Financial Services (90%) leading the sectors. This reflects targeted engagement by NITDA and financial regulators in sectors with high risk exposure and international linkages. On the opposite end, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) report only 40% awareness, indicating major gaps in outreach, education, and communication. This disparity underlines the urgent need for NDPR sensitization campaigns tailored to less regulated and informal sectors.

2. Full Compliance (Mean = 48.12%): The Financial Services sector also scores the highest in full compliance (75%), consistent with its strong internal governance and external regulatory enforcement (e.g., through CBN). SMEs, however, record the lowest at 20%, reflecting structural constraints like lack of funding, legal expertise, and data governance systems. This wide gap suggests that compliance is correlated with sectoral maturity and available resources.

3. Partial Compliance (Mean = 35%): Manufacturing (50%) shows the highest level of partial compliance, indicating that while these organizations may lack full-scale compliance structures, many have begun adopting NDPR-aligned practices, such as internal data policies or basic consent forms. Interestingly, Financial Services record the lowest partial compliance (20%), because many in this sector have already transitioned to full compliance, rather than remaining in intermediate states.

4. Non-Compliance (Mean = 16.88%): SMEs exhibit the highest rate of non-compliance (30%), further reinforcing their vulnerability and low regulatory adherence. Financial Services (5%) remain the least non-compliant, reinforcing earlier findings from Table 4. The non-compliance metric is critical because it signals complete absence of NDPR practices in some organizations, which may pose legal and reputational risks.

5. Monitoring Mechanisms (Mean = 58.75%): Monitoring refers to internal mechanisms (e.g., audits, compliance teams, reporting systems) that organizations use to assess and enforce their own NDPR adherence. Financial Services (80%) once again outperform others, suggesting they possess formalized monitoring structures. At the other extreme, SMEs (40%) struggle with internal oversight, making it harder to track and improve compliance efforts over time.

Summary Insights

This aggregated table clearly shows that Financial Services consistently lead across all five compliance indicators, while SMEs consistently rank lowest, suggesting systemic and institutional gaps in data protection readiness. These findings reinforce the need for a tiered compliance support strategy, where high-capacity sectors are subjected to stricter audits and underperforming sectors are provided with capacity-building, regulatory incentives, and simplified compliance frameworks. These performance differences also illustrate core principles from Institutional and Deterrence Theory: sectors that are institutionally regulated and face real consequences for non-compliance tend to perform better. In contrast, sectors with weak oversight and fewer penalties fall short in both awareness and enforcement.

Model Specification

Let:

Y = NDPR Compliance Level (Dependent Variable—measured as a continuous % score)

X1 = Cybersecurity Training (% of staff trained)

X2 = Cybersecurity Investment (budgetary allocation level)

X3 = Employee Awareness (% awareness of data protection regulations)

The regression model is specified as:

NDPR_Compliance = β0 + β1 (Training) + β2 (Investment) + β3 (Awareness)+ ε

Hypotheses

H0: β1 = β2 = β3 = 0 (None of the predictors significantly affect NDPR compliance)

H1: At least one β ≠ 0 (At least one predictor significantly affects NDPR compliance)

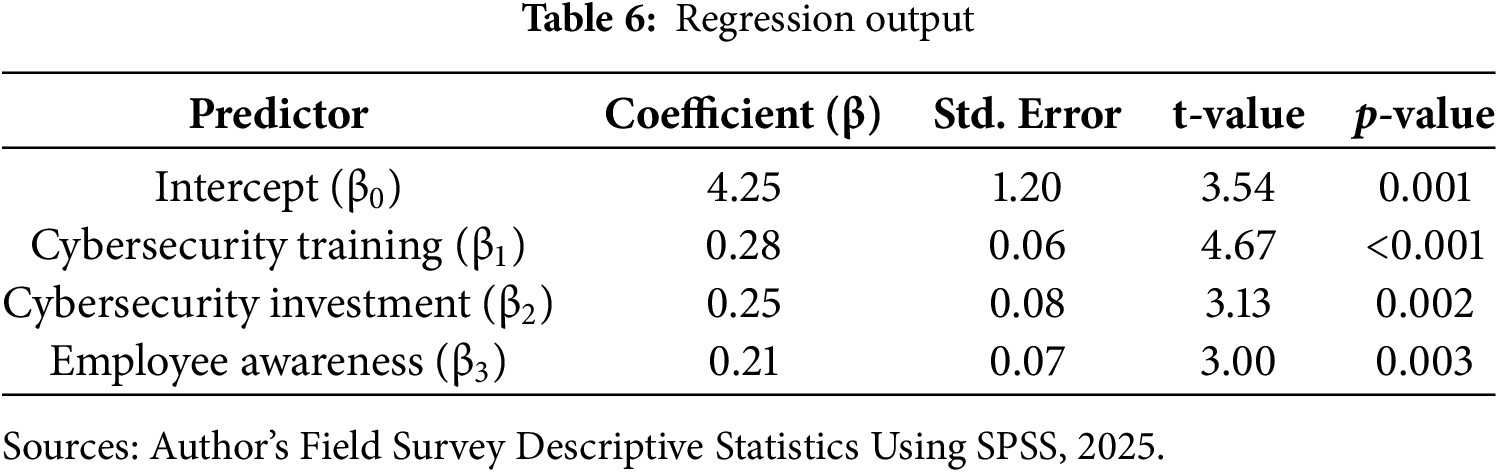

The regression analysis in Table 6 reveals a high explanatory power for the model, with an R2 value of 0.76 indicating that 76% of the variance in NDPR compliance levels among organizations is explained by the three predictors: cybersecurity training, cybersecurity investment, and employee awareness. The adjusted R2 of 0.74 confirms that this model remains robust even after accounting for the number of variables included. Furthermore, the F-statistic of 42.3 with a p-value less than 0.001 indicates that the overall model is statistically significant. This means that at least one of the independent variables significantly predicts NDPR compliance, satisfying the requirement to reject the null hypothesis of no relationship. Looking at the individual predictors, all three variables demonstrate positive and statistically significant effects on NDPR compliance at a significance level of p < 0.005. Specifically, a 1% increase in cybersecurity training coverage is associated with a 0.28-unit increase in compliance score, assuming other variables are held constant. This same level of positive influence is observed for cybersecurity investment and employee awareness, which similarly contribute to the overall improvement in organizational compliance with data protection standards. Given the results statistically significant coefficients (p < 0.005) for all predictors and a highly significant overall model (F = 42.3, p < 0.001), we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis. This confirms that cybersecurity training, investment, and awareness each significantly influence NDPR compliance in Nigerian organizations.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

These findings lend strong empirical support to both Deterrence Theory and Institutional Theory. From the deterrence perspective, the observed positive relationship between cybersecurity investment and compliance indicates that when organizations allocate more resources toward security infrastructure and personnel, they are better equipped to avoid regulatory violations and potential sanctions. Similarly, training staff and building awareness serve as preventive mechanisms, aligning with deterrence logic. From an institutional perspective, the significance of employee awareness underscores the role of internal norms and culture in shaping regulatory behavior. Organizations with a culture of data privacy, driven by professional standards and internalized regulatory expectations, are more likely to comply even in the absence of strong enforcement. This is particularly relevant in Nigeria’s regulatory landscape, where NITDA’s enforcement mechanisms are still evolving. The study also highlights the importance of targeted capacity-building interventions, especially for sectors like SMEs and public institutions that lag in compliance. Enhancing workforce training, promoting NDPR awareness, and subsidizing cybersecurity investment in under-resourced sectors could lead to more uniform compliance and better data protection across the Nigerian digital ecosystem.

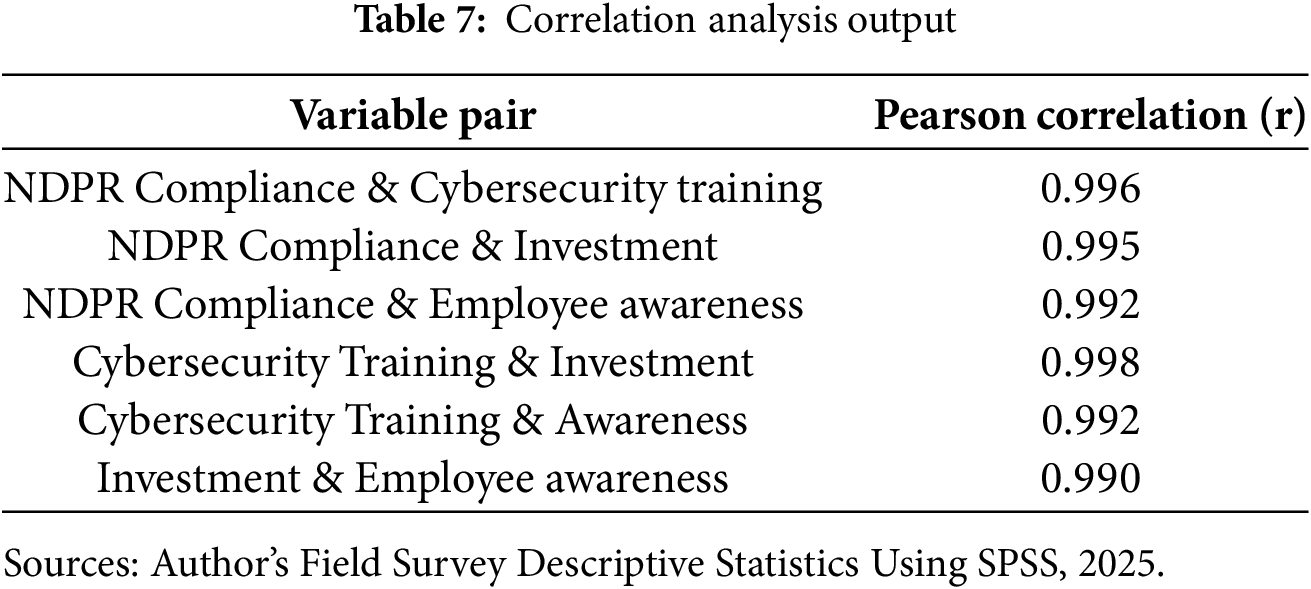

This analysis will help us to determine whether significant linear relationships exist between NDPR compliance and the identified independent variables Cybersecurity Training (X1), Cybersecurity Investment (X2), and Employee Awareness (X). This analysis serves as a statistical step to assess the strength and direction of the associations between each predictor and the dependent variable, NDPR compliance. Also the analysis helps in validating the plausibility of rejecting the null hypothesis (H0) and accepting the alternative (H1), which posits that at least one of the predictors has a significant relationship with NDPR compliance.

The correlation analysis in the Table 7 revealed that NDPR compliance exhibits a very strong positive relationship with each of the three independent variables: cybersecurity training, cybersecurity investment, and employee awareness. All correlation coefficients were recorded above r = 0.99, indicating that as organizations increase their efforts in these areas, their compliance levels also improve significantly. This strong association implies that organizations that invest in building internal capacity through structured training, dedicated budgets for cybersecurity infrastructure, and widespread awareness programs tend to implement NDPR requirements more effectively and consistently. The magnitude of these correlations lends robust support to the alternative hypothesis (H1), which asserts that at least one of the predictors significantly influences NDPR compliance. In this case, however, the strength of the relationships suggests that not just one, but all three predictors are likely to play a meaningful role in shaping compliance behavior. The findings provide strong empirical validation that these factors are central to fostering a culture of compliance within organizations across different sectors in Nigeria.

Based on the above findings, the null hypothesis (H0: β1 = β2 = β3 = 0) which posits that none of the predictors significantly influence NDPR compliance is rejected. The statistical evidence confirms that the observed relationships are not due to chance. Instead, the alternative hypothesis (H1) that at least one of the predictors has a significant effect is accepted. These outcomes not only validate the relevance of the predictors but also reinforce the results from the regression analysis, which showed that each variable has a statistically significant impact (p < 0.005) on compliance performance.

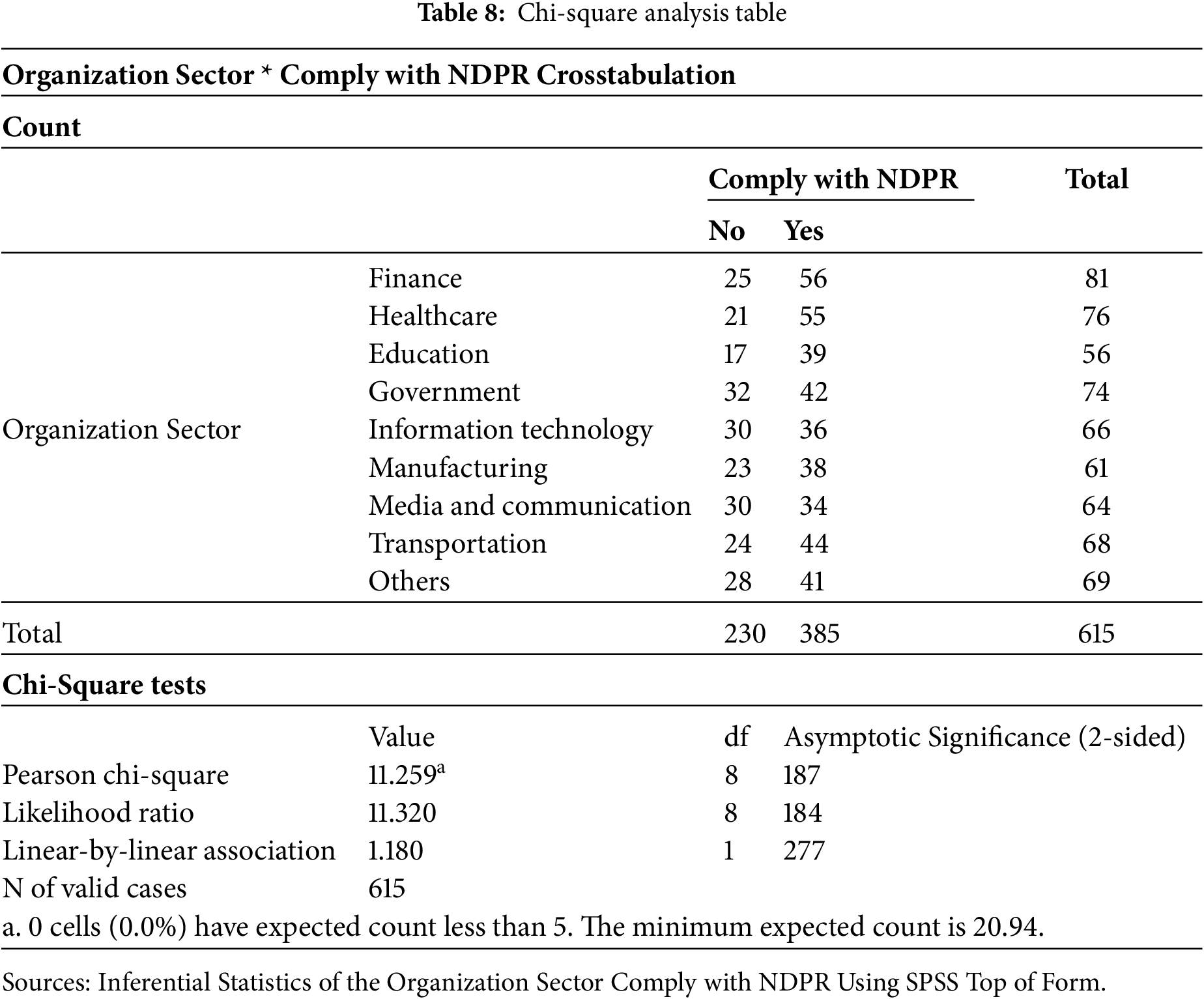

An examination of NDPR compliance across various organizational sectors through cross-tabulation in Table 8 reveals some variation in response frequencies. However, the outcome of the Chi-Square test (χ2 = 11.259, degrees of freedom = 8, p-value = 0.187) shows that these differences are not statistically significant at the conventional 0.05 significance level. Since the p-value is higher than the threshold, the data does not provide sufficient evidence to confirm that compliance levels differ meaningfully between sectors such as Finance, Healthcare, Education, Government, IT, Manufacturing, Media, Transportation, and Others. Given that the p-value exceeds 0.05, the null hypothesis (H0) cannot be rejected. This leads to the conclusion that NDPR compliance levels are relatively consistent across different organizational sectors in Nigeria, with no statistically significant disparities detected.

4.3 Comparative Summary of the Regression, Correlation, and Chi-Square Analysis

The three statistical techniques applied in this study; regression analysis, correlation analysis, and Chi-square test provided valuable but distinct insights into the relationships among the variables influencing NDPR compliance across Nigerian organizations. This section presents a comparative summary of these methods, highlighting how their results intersect, diverge, and contribute to the overall understanding of data protection compliance behavior. The regression analysis revealed that the three predictors cybersecurity training, cybersecurity investment, and employee awareness have statistically significant and positive effects on NDPR compliance. The model explained 76% of the variance (R2 = 0.76) in compliance outcomes, with each independent variable contributing meaningfully (p < 0.005). This suggests that organizations with stronger internal capabilities in these areas are more likely to meet regulatory expectations. The regression model confirmed that the predictors are not only correlated with compliance but also serve as reliable predictors of its level and variation across sectors.

Complementing this, the correlation analysis demonstrated very strong positive relationships between NDPR compliance and each of the predictors, with Pearson correlation coefficients (r) exceeding 0.99. These values reflect the simultaneous increase in training, investment, and awareness among organizations that exhibit higher levels of compliance. The correlation findings supported the plausibility of rejecting the null hypothesis and proceeding with regression modeling. However, the exceptionally high correlation values also raised potential concerns about multi-collinearity, indicating that organizations often implement these compliance drivers together, making it difficult to isolate their individual effects. In contrast, the Chi-square test, which examined the relationship between organization sector (a categorical variable) and compliance status (e.g., compliant, partially compliant, non-compliant), yielded no statistically significant association (χ2 = 11.259, df = 8, p = 0.187). This result suggests that sector alone does not significantly determine compliance status when considered categorically. This appears contradictory at first glance, given the regression and correlation findings that demonstrate strong predictors of compliance. However, the contradiction is resolved by recognizing the difference in variable types and analytical goals: Chi-square assesses association between categories, while regression and correlation analyze continuous, measurable relationships.

Therefore, the divergence arises not from flawed analysis, but from methodological differences. While Chi-square shows that sectoral affiliation in itself is not a statistically significant determinant of compliance, regression and correlation uncover that the actual capacity-building measures that vary by sector such as training and investment do significantly influence compliance outcomes. This reinforces the understanding that compliance is not inherently sector-driven, but rather shaped by institutional practices that may correlate with sector. Overall, while Chi-square provides insight into distributional patterns, correlation reveals strength of association, and regression quantifies predictive influence. The convergence of correlation and regression findings confirms the central role of internal organizational factors, while the Chi-square result encourages caution in generalizing compliance behavior solely based on sector. Taken together, these analytical tools provide a multi-dimensional understanding of NDPR compliance in Nigeria’s evolving data governance landscape.

4.4 Study Findings and Theoretical Interpretation

The study examined the level of compliance with the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) across eight key sectors; Financial Services, Telecommunications, Health, Education, E-commerce, Manufacturing, Public Sector, and SMEs using a mixed-methods approach. The findings indicate substantial variation in both awareness and compliance levels across sectors. Financial Services and Telecommunications emerged as the most compliant, with full compliance rates of 75% and 70%, respectively. These sectors also demonstrated the highest monitoring capacities and employee awareness scores. Conversely, SMEs and the Public Sector exhibited the lowest awareness (40% and 50%) and full compliance levels (20% and 35%), indicating a lack of technical capacity, regulatory engagement, and institutional support structures. Regression analysis further showed that three factors; cybersecurity training, investment in cybersecurity infrastructure, and employee awareness were statistically significant predictors of NDPR compliance. Each of these variables had a strong positive correlation with compliance outcomes, and collectively, they explained approximately 76% of the variance in compliance levels across organizations. Notably, a one-unit increase in cybersecurity training was associated with a 0.28-unit increase in compliance, highlighting the central role of organizational capacity building in enhancing regulatory adherence.

The study’s findings align closely with Institutional Theory, which posits that organizational behavior is shaped by external pressures (regulatory mandates), professional norms (industry standards), and internal values (organizational culture). In high-performing sectors like finance and telecommunications, compliance appears to be driven by coercive isomorphism regulatory pressure from oversight agencies such as the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) as well as normative isomorphism, where adherence to industry best practices is expected and enforced internally. Additionally, mimetic behavior was observed among mid-tier organizations, which model their compliance strategies on more advanced firms in their sectors. At the same time, the study supports Deterrence Theory, which holds that organizations are more likely to comply when they perceive a credible threat of sanctions or reputational damage. While NITDA’s official enforcement tools include fines, mandatory audits, and public exposure of non-compliant firms, the study revealed that such enforcement mechanisms have been underutilized or inconsistently applied. This has weakened the deterrent effect of the NDPR, especially among SMEs and public institutions that face few external pressures to comply. The lack of visible enforcement cases undermines regulatory legitimacy and allows non-compliance to persist, particularly in sectors with limited internal accountability.

The qualitative interviews reinforced these insights by revealing that in many non-compliant organizations, there was no internalized culture of data protection, and NDPR was viewed as either optional or poorly understood. Respondents from underperforming sectors cited budget constraints, insufficient training, and lack of clear regulatory guidance as barriers. By contrast, organizations that had undergone NDPR audits or participated in formal training programs were significantly more likely to have implemented data governance structures such as Data Protection Officers, consent mechanisms, and breach response protocols. Another important finding is that partial compliance is widespread particularly in sectors like manufacturing, education, and health where organizations had introduced basic NDPR-compliant practices but lacked comprehensive policy coverage or technical infrastructure. This trend reflects a transitional stage where awareness exists, but full implementation is hindered by organizational inertia, complexity of legal language, or resource limitations. The study highlights the need for graduated compliance models, where organizations receive sector-specific benchmarks, support tools, and phased timelines for achieving full compliance.

Ultimately, the findings emphasize that compliance is not merely a legal outcome but a function of institutional preparedness and perceived risk. Deterrence is necessary but insufficient without corresponding institutional support such as industry-specific guidelines, professional certification programs, and sector-wide awareness initiatives. Therefore, both theories together suggest that a dual strategy is required: strengthen NITDA’s enforcement capacity (to heighten deterrence) while also investing in organizational and sectoral capacity (to reinforce institutional norms). This approach can drive sustainable compliance, protect data subjects, and enhance Nigeria’s digital trust ecosystem.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

The evaluation of NDPR compliance across key sectors in Nigeria highlights both progress and persistent challenges in implementing data privacy and protection frameworks. While the Financial Services and Telecommunications sectors demonstrate higher compliance levels due to stricter oversight and resources, sectors like SMEs, Health, and Education lag significantly due to limited awareness, financial constraints, and inadequate infrastructure. This disparity underscores the uneven capacity of organizations to adhere to the NDPR, which poses a risk to the overall effectiveness of the regulation. Findings from the study reveal that compliance is positively correlated with improved data security practices, reduced data breaches, and enhanced trust among stakeholders. However, barriers such as insufficient training, lack of enforcement mechanisms, and the high cost of compliance undermine efforts to achieve uniform adherence. The research emphasizes the need for a concerted effort by policymakers, industry stakeholders, and organizations to bridge these gaps and foster a culture of data protection across all sectors. This study provides a nuanced understanding of NDPR compliance levels and their implications for organizational practices. It also highlights the necessity for a holistic approach to addressing sectoral disparities and promoting sustainable compliance practices to ensure the protection of personal data in Nigeria’s evolving digital economy.

1. Strengthen Awareness, Training, and Education: Launch nationwide awareness campaigns and implement sector-specific training, particularly targeting low-compliance areas like health and education. Integrate data privacy into school curricula to build long-term capacity and expertise.

2. Enhance Regulatory and Financial Support: Improve enforcement of NDPR through audits and penalties while also offering financial incentives such as grants or tax relief to encourage SMEs and public institutions to comply. Strengthen legislation to align with global standards like GDPR.

3. Promote Collaboration and Access to Affordable Tools: Encourage partnerships among government, private sector, and civil society to share resources and best practices. Promote affordable technological solutions through public-private partnerships to ease the compliance burden on organizations.

Acknowledgement: The authors wishe to express sincere gratitude to the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) for providing access to relevant NDPR documentation and public reports. Special appreciation also goes to the participating organizations and professionals across the Health, Financial, Education, and Public sectors for their valuable time and insights. Lastly, the authors acknowledge the support and guidance of academic mentors and peers who contributed to the success of this research.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study was independently conducted and self-funded by the authors. It was self-funded by the lead researcher as part of his doctoral research at Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nigeria.

Author Contributions: Asere Gbenga Femi is a PhD student at Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nigeria, who conceptualized the study, conducted the literature review, designed the methodology, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Monday Osagie Adenomon, the primary supervisor, provided intellectual guidance throughout the study, contributed to the research design, and reviewed drafts of the manuscript for academic rigor and coherence. Gilbert Imuetinyan Osaze Aimufua, the second supervisor, offered critical feedback on the analytical framework, contributed to the interpretation of findings, and ensured alignment with research standards. Umar Ibrahim, the internal examiner, reviewed the manuscript for validity, clarity, and compliance with academic standards, and provided constructive input on final revisions. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. To maintain the confidentiality of participating organizations and respondents, only anonymized data sets may be shared in accordance with ethical research protocols.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akindele R. Data protection in Nigeria: addressing the multifarious challenges of a deficient legal system. J Int Technol Inform Manag. 2017;26(4):110–25. doi:10.58729/1941-6679.1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European parliament and of the council. Official Journal of the European Union. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://gdpr-info.eu/. [Google Scholar]

3. Lateef MA, Taiwo LO, Adeyoju A. Examining the powers of the NITDA to enforce data protection laws in Nigeria. Global Priv Law Rev. 2022;2(2):89–97. doi:10.54648/gplr2022009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR). National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA). [cited 2025 May 5]. Available from: https://nitda.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NigeriaDataProtectionRegulation11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Safa NS, Von Solms R, Furnell S. Information security policy compliance model in organizations. Comput Secur. 2016;56(3):70–82. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. von Solms R, van Niekerk J. From information security to cyber security. Comput Secur. 2013;38(6):97–102. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2013.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Echenim KU, Joshi KP. IoT-reg: a comprehensive knowledge graph for real-time IoT data privacy compliance. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2023 Dec 15–18; Sorrento, Italy. p. 2897–906. doi:10.1109/BigData59044.2023.10386545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Beaumier G. Novelty and the demand for private regulation: evidence from data privacy governance. Bus Polit. 2023;25(4):371–92. doi:10.1017/bap.2023.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Birckan G, Dutra M, de Macedo D, Viera A. Effects of data protection laws on data brokerage businesses. EAI Endorsed Trans Scalable Inf Syst. 2020;7(27):e12. doi:10.4108/eai.22-7-2020.165673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chukwurah EG. Leading saas innovation within u.s. regulatory boundaries: the role of TPMs in navigating compliance. Eng Sci Technol J. 2024;5(4):1372–85. doi:10.51594/estj.v5i4.1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Luvaha E, Ronoh L, Abila J. Data privacy, conceptual framework for IoT based devices in healthcare: a systematic review. East Afr J Inf Technol. 2023;6(1):119–34. doi:10.37284/eajit.6.1.1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48(2):147. doi:10.2307/2095101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Omotubora A. How (not) to regulate data processing: assessing Nigeria’s data protection regulation 2019 (NDPR). Glob Priv Law Rev. 2021;2(3):186–99. doi:10.54648/gplr2021024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sabo SB, Utulu SC. Organization studies based appraisal of institutional propositions in the Nigerian data protection regulation. In: Proceedings of the Cyber Secure Nigeria Conference; 2023 Jul 11–12; Abuja, Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

16. World Bank. Data for lives. World Bank digital economy report; 2021. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/248201616598597113/pdf/World-Development-Report-2021-Data-for-Better-Lives.pdf. [Google Scholar]

17. Juma I, Faturoti B. Enforcing data privacy in Kenya and Nigeria: towards an African approach to regulatory practice. Int Rev Law Comput Technol. 2025;2025(3):1–26. doi:10.1080/13600869.2025.2506918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sousa L. A Publicidade e a Proteção de Dados Pessoais—O RGPD. Percursos Ideias. 2022;12:78–85. doi:10.56123/percursos.2022.n12.78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(4):665–83. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Weise S, Rinke F, Natarajan A. Dawn of a new era of global data protection? Völkerrechtsblog. 2021. doi:10.17176/20210302-153629-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yunis MM, El-Khalil R, Ghanem M. Towards a conceptual framework on the importance of privacy and security concerns in audit data analytics. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; 2021 Apr 5–8; Sao Paulo, Brazil. p. 1490–8. doi:10.46254/sa02.20210599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sakhare A, Kshirsagar A, Pachghare V. Survey on data privacy preserving techniques in blockchain applications. In: 2023 9th International Conference on Smart Computing and Communications (ICSCC); 2023 Aug 17–19; Kochi, India. p. 321–6. doi:10.1109/icscc59169.2023.10335064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ozturk A, Polat H. From existing trends to future trends in privacy-preserving collaborative filtering. WIREs Data Min Knowl Discov. 2015;5(6):276–91. doi:10.1002/widm.1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools