Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HI-XDR: Hybrid Intelligent Framework for Adversarial-Resilient Anomaly Detection and Adaptive Cyber Response

Cyber Security Specialist, PT Sentra Keamanan Digital, Makassar, 90221, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Abd Rahman Wahid. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 589-614. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.071622

Received 08 August 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 11 December 2025

Abstract

The rapid increase in cyber attacks requires accurate, adaptive, and interpretable detection and response mechanisms. Conventional security solutions remain fragmented, leaving gaps that attackers can exploit. This study introduces the HI-XDR (Hybrid Intelligent Extended Detection and Response) framework, which combines network-based Suricata rules and endpoint-based Wazuh rules into a unified dataset containing 45,705 entries encoded into 1058 features. A semantic-aware autoencoder-based anomaly detection module is trained and strengthened through adversarial learning using Projected Gradient Descent, achieving a minimum mean squared error of 0.0015 and detecting 458 anomaly rules at the 99th percentile threshold. A comparative evaluation against Isolation Forest, One-Class Support Vector Machine, and standard autoencoders showed superior performance with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.91 and an Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve (AUPRC) of 0.88, highlighting the benefits of combining rules and semantic embeddings. Resilience analysis shows that the adversarially trained model maintains stable reconstruction errors when attacked (0.001419 for normal samples vs. 0.001472 for corrupted samples). To improve interpretability, SHapley Additive exPlanations identifies critical rule attributes such as source encoding and compliance groups. Finally, the Deep Q-Network agent was trained over 5000 episodes, converging to an average reward of 20, and reliably selected decisive mitigation actions for anomalies while avoiding disruptive responses to harmless events. Overall, HI-XDR offers an intelligent, transparent, and robust approach to next-generation cybersecurity defense, while further research will validate its scalability on large-scale public datasets.Keywords

Cyber attacks continue to grow in scale and sophistication, creating severe challenges for organizations in sustaining an effective security posture [1]. Traditional detection systems, including signature-based intrusion detection systems (IDS) and endpoint detection and response (EDR) platforms, are often deployed in silos and operate reactively [2]. Such fragmentation leads to slow responses, limited adaptability to novel attacks, and opaque decision-making processes that hinder trust and efficient mitigation [3]. These limitations have motivated research toward more holistic frameworks that consolidate visibility across heterogeneous sources while embedding artificial intelligence for detection, interpretability, and adaptive response.

Recent studies show that while IDS and EDR technologies have matured, integration across network-level monitoring and endpoint-centric data remains limited [4]. Moreover, existing anomaly detection approaches, although increasingly powered by machine learning and deep learning, remain vulnerable to adversarial manipulations and often lack interpretability [5]. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) are promising, yet comparative justifications against alternatives like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) are still underexplored [6]. Reinforcement learning (RL) has also been applied to automate cyber responses, but many works remain conceptual or lack detailed benchmarking against alternative algorithms [7]. Finally, state-of-the-art approaches such as transformer-based models have demonstrated strong potential for intrusion detection, highlighting the need to align anomaly detection research with modern architectures [8]. In response to these gaps, this research proposes HI-XDR (Hybrid Intelligent Extended Detection and Response), a unified framework that fuses Suricata rules for network-level intrusion detection with Wazuh rules for host-based monitoring into a consolidated dataset. The framework applies a semantic-aware autoencoder for anomaly detection, hardened with adversarial training via Projected Gradient Descent to ensure resilience against evasion. SHAP is integrated to provide interpretable feature-level insights [9,10], and a Deep Q-Network (DQN) agent is trained to deliver adaptive and automated incident responses [11].

The main contributions of this work are fourfold. First, we develop a methodology to consolidate heterogeneous detection rules from network and endpoint sources into a standardized dataset. Second, we design and evaluate an adversarially trained autoencoder that demonstrates robustness against adversarial manipulation. Third, we justify the choice of SHAP for model interpretability and DQN for adaptive response through comparative literature and empirical validation. Fourth, we benchmark our framework against strong baselines including Isolation Forest, One-Class Support Vector Machine, vanilla autoencoder, and single-source models and demonstrate improvements in anomaly detection performance and adaptive response. Collectively, HI-XDR represents a step toward more intelligent, resilient, and transparent cybersecurity operations.

This literature review explores relevant research that forms the foundation for the development of HI-XDR, covering aspects of anomaly detection, model resilience, explainable AI, and adaptive response in cybersecurity.

2.1 Intrusion Detection and Endpoint Detection Response

Detection and response are fundamental components of cybersecurity architecture, with evolution from signature-based to anomaly-based detection. Signature-based detection is effective in identifying known threats but fails to detect unknown or zero-day attacks [12]. In contrast, anomaly-based detection leverages machine learning to study normal behavior and flag deviations [13]. To address visibility gaps, EDR, Network Detection and Response (NDR), and XDR have emerged, enabling endpoint and network monitoring with broader context [14]. (Security Information and Event Management) SIEM platforms such as Wazuh integrate endpoint telemetry with centralized event correlation [15], while Suricata provides high-performance network-based intrusion detection [16]. Nevertheless, interoperability and data fragmentation across systems remain significant challenges [17]. Recent hybrid detection studies have started addressing these limitations through cross-domain data fusion and intelligent automation. A 2023 study in JAET (Journal of Advanced Engineering and Technology) introduced a hybrid multi-layer intrusion detection and response framework that merges network and endpoint visibility to improve situational awareness, though it remains rule-static and lacks adversarial robustness [18]. In 2024, IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics reported an edge-oriented intrusion detection system emphasizing lightweight AI models for efficiency, yet without deeper semantic integration between sources [19]. Similarly, research presented at ICEET 2023 proposed a real-time hybrid fusion model for constrained environments, but its evaluation lacked explainability and adaptive response mechanisms [20]. These findings reveal a growing trend toward integrated and intelligent XDR paradigms, while underscoring the continuing need for schema-level normalization, interpretability, and resilience areas that form the conceptual motivation for HI-XDR.

2.2 Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection

Machine learning (ML) has long been used for anomaly detection, with classical methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Decision Trees applied to network and malware detection tasks. However, these approaches struggle with scalability and high-dimensional data, making them less suited for modern cybersecurity environments. Deep learning (DL) models, particularly autoencoders, provide stronger capabilities in learning compact representations of complex data distributions and identifying deviations through reconstruction error. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of autoencoders for anomaly detection in high-volume traffic and user behavior analytics [21]. Furthermore, the advent of transformer architectures has begun reshaping intrusion detection research by leveraging attention mechanisms to capture sequential and contextual dependencies in security data [22]. These advances indicate a paradigm shift from traditional models toward more scalable, semantic-rich anomaly detection frameworks.

2.3 Adversarial ML and Model Resilience

Despite the success of ML/DL in anomaly detection, adversarial attacks expose critical vulnerabilities. Attackers can generate perturbed samples that evade detection while appearing benign to models [23]. Among evasion methods, Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) remains widely used for crafting adversarial inputs within bounded constraints [24]. Adversarial training augmenting training with adversarial samples has proven an effective defense strategy, enhancing robustness against manipulation [25]. Recent works further highlight the importance of tailoring perturbation constraints to security contexts, ensuring that adversarial examples reflect feasible attack states [26]. These insights underscore the need for resilient architectures capable of maintaining detection fidelity under adversarial pressure.

2.4 Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)

While deep learning enhances detection performance, its opacity creates barriers for operational adoption in security operations that demand accountability. XAI addresses this by providing human-understandable justifications for model outputs [27]. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is increasingly favored due to its theoretical foundation in cooperative game theory and consistency across models [28]. Comparative evaluations have shown that SHAP generally provides more stable and faithful feature attributions than LIME in cybersecurity applications [29]. Applied in contexts such as malware classification and anomaly detection, SHAP explanations enable analysts to verify alerts and understand system behavior [30]. This justifies the choice of SHAP over LIME in HI-XDR, aligning interpretability with robustness and transparency.

2.5 Reinforcement Learning in Cybersecurity Response

Reinforcement learning (RL) enables adaptive decision-making by learning from interaction with an environment, optimizing responses to dynamic threats. Applications in cybersecurity include automated traffic blocking, host isolation, and forensic triage [31]. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) integrates neural networks with RL to handle high-dimensional state-action spaces. Among DRL methods, the Deep Q-Network (DQN) is particularly effective in discrete action settings, enabling policy learning from large-scale replayed experiences. Compared to other RL techniques such as Policy Gradient or Actor Critic, DQN offers stable convergence and efficient learning for rule-driven security response. Recent surveys confirm its suitability in communication networks and cyber defense [32]. Thus, HI-XDR employs DQN as the response engine to balance adaptivity with operational reliability.

2.6 Research Gaps and HI-XDR Position

Although research on anomaly detection, model robustness, interpretability, and adaptive response is advancing rapidly, most studies address these components in isolation. Few frameworks integrate network and endpoint-level signals into a unified dataset, and even fewer combine adversarial resilience with interpretable detection and automated adaptive response. Current evaluations often lack benchmarks against strong baselines such as Isolation Forest, One-Class SVM, vanilla autoencoders, or single-source IDS/EDR pipelines, making it difficult to assess the relative contribution of each technique. Furthermore, while SHAP has been applied for interpretability, its comparative advantages over LIME in operational cybersecurity contexts remain underreported. Similarly, RL-based adaptive response is still in its infancy, with limited studies justifying the choice of algorithms. HI-XDR specifically addresses these gaps by proposing a hybrid framework that fuses Suricata and Wazuh data sources, trains a robust autoencoder enhanced with adversarial training, integrates SHAP for explainability, and employs DQN for adaptive response. This integration represents a significant step toward intelligent, resilient, and transparent cybersecurity systems.

Methodology designed to build and evaluate the HI-XDR architecture at each stage is described in this section.

3.1 HI-XDR Overall System Architecture

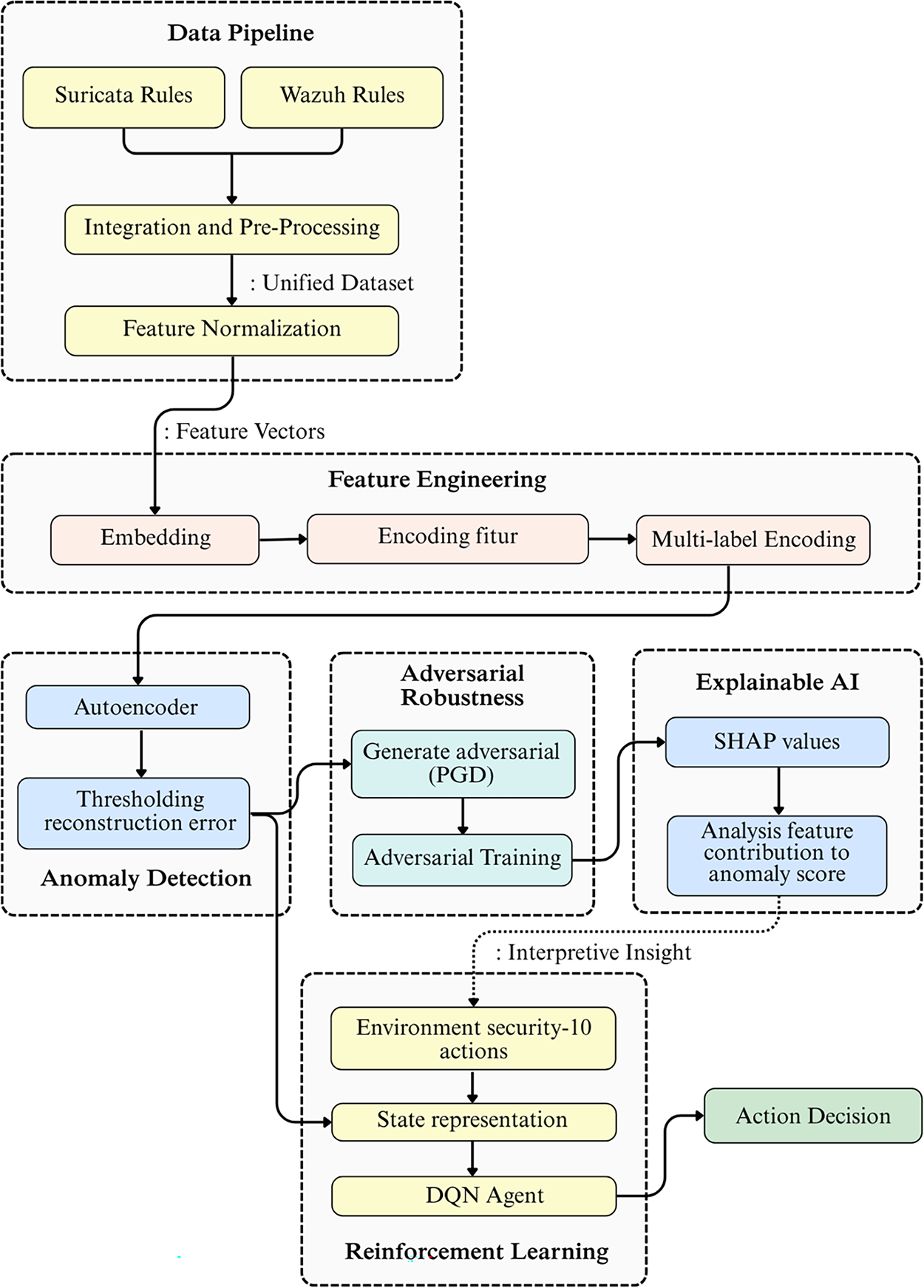

The HI-XDR framework is a modular security pipeline that fuses detection and response across network and endpoint layers while preserving transparency and operational safety. As shown in Fig. 1, raw detection rules from Suricata (network) and Wazuh (endpoint) enter a data pipeline where they are integrated, standardized, and normalized into a unified dataset.

Figure 1: HI-XDR architecture diagram overview

Feature engineering then produces semantic embeddings of rule descriptions, encoded categorical attributes (single and multi-label), and selected numerical features. These feature vectors feed an anomaly detection module based on an autoencoder that learns a compact representation of “normal” rules and flags atypical patterns via reconstruction error. To ensure reliability in dynamic, adversarial settings, the detector is hardened with adversarial training using PGD generated examples under domain-valid constraints, and its anomaly scores are calibrated prior to thresholding to support consistent, risk-aware decisions.

To make the detector’s behavior auditable, an XAI layer (SHAP) provides post-hoc attributions that identify which features most influence the anomaly score at both global and per-event levels. These explanations are logged alongside model outputs to support analyst validation and playbook refinement. Detection outputs and SHAP insights are aggregated into a compact state representation that conditions a reinforcement learning policy (Deep Q-Network, DQN). The policy selects an action from a discrete response set (e.g., quarantine host, temporary IP block, forensic scan). Before execution, actions pass through a lightweight safety gate/human-in-the-loop layer that enforces guardrails for high impact interventions (e.g., dual confirmation, rate limiting, or evidence multiplexing) to minimize operational risk and false positive harm. The architecture exposes standard observability hooks (latency, throughput, AUROC/PR-AUC at selected operating points, TPR@FPR, calibration error) and audit logs (anomaly scores, thresholds, SHAP attributions, chosen actions). This design keeps components decoupled, data ingestion, feature store, detector, explanation, policy, and actuator, so each can be independently updated or replaced without disrupting the end-to-end workflow, enabling scalable maintenance and controlled evolution of the system.

3.2 Data Collection, Consolidation, and Pre-Processing

The HI-XDR pipeline begins with curating rule artifacts from two sources and transforming them into an analysis-ready corpus. This research utilizes two main sources of detection rule data:

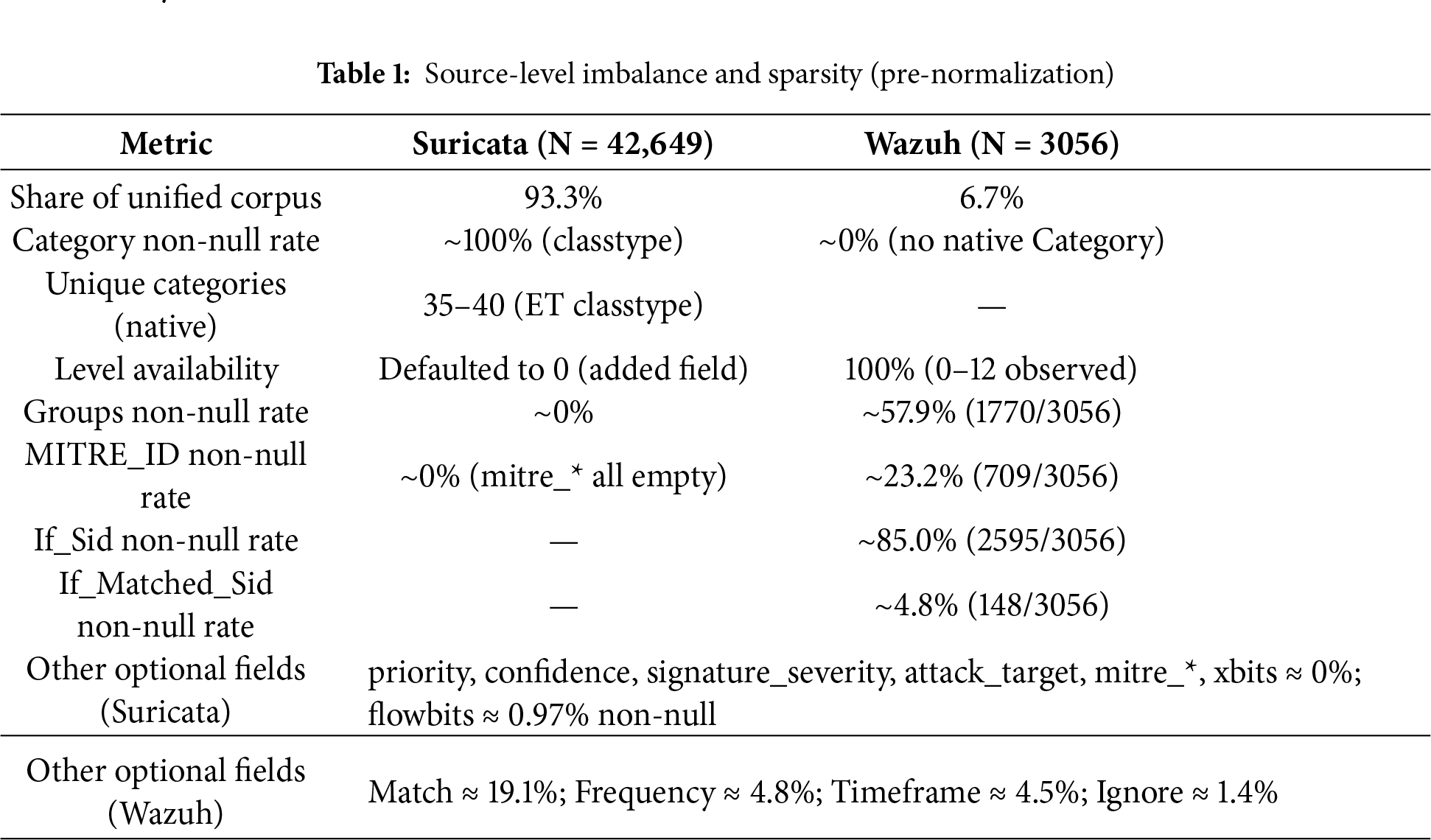

1. Suricata rules (NDR). We ingest Emerging Threats (ET) network rules parsed to CSV. Each row represents a single rule line (N = 42,649). Core fields retained for analysis are sid (rule identifier), msg (rule text/alert message), and classtype (rule category). Several optional fields including reference, priority, confidence, signature_severity, attack_target, mitre_*, and xbits, are near-empty (≤1% non-null) and are therefore excluded to avoid uninformative sparsity and reduce spurious variance in downstream modeling, see sparsity summary in Table 1.

2. Wazuh rules (EDR/SIEM). We parse Wazuh rule XML to CSV (N = 3056). Fields retained include Rule_ID, Level, Description, Groups, MITRE_ID, If_Sid, and If_Matched_Sid. Other attributes (Match, Frequency, Timeframe, Ignore) show high missingness and are not propagated to the unified schema, summary in Table 1.

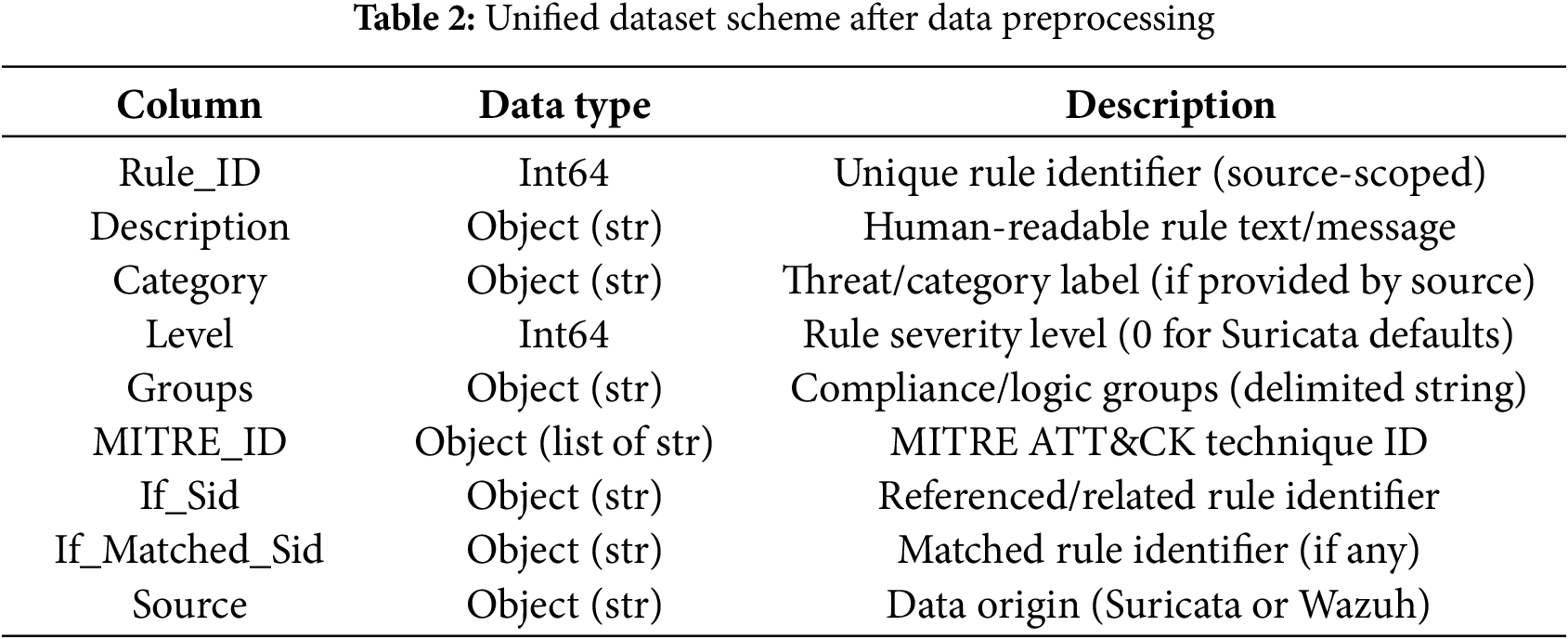

Heterogeneous attributes are mapped to a common schema to enable joint modeling, sid (Rule_ID), msg (Description), and classtype (Category). A consistency field Level (default 0) is added to Suricata records to align with Wazuh severity semantics, and a Source tag (Suricata/Wazuh) is appended to all rows for provenance tracking. The MITRE_ID field from Wazuh is normalized to a list of technique IDs (e.g., [“T1562.001”]) to support multi-label encoding, values serialized as strings are parsed into lists. The Groups field is retained as a delimited string at this stage (binarized during feature engineering). Before merging, data type consistency (Rule_ID and Level as integers, category/text as strings) is ensured and empty/NaN values in the Category, Groups, If_Sid, and If_Matched_Sid columns are converted to empty strings, while ensuring that MITRE_ID is a list (possibly empty).

We also validated the identification domain to prevent leakage between sources by treating the composite key (Source, Rule_ID) as unique; byte-exact duplicates under this key would be removed if found. After cleaning, the tables are vertically merged into a unified corpus containing 45,705 rules. The final data dictionary used by subsequent modules is shown in Table 2.

Conservative rules are applied, excluding fields with a non-null rate ≤1% or with unclear semantics across various sources from the combined table input. This includes priorities, confidence, signature severity levels, attack targets, mitre_*, xbits, and flowbits that are nearly empty from Suricata, as well as Frequency, Time Range, and Ignore from Wazuh. We recognize that removing rare metadata may, in principle, remove valuable signals for niche anomalies (e.g., rare defense evasion tags). To mitigate this risk, (i) MITRE_ID and Groups from Wazuh are retained and encoded multi-hot downstream; (ii) sentence embeddings from Description retain tactic/technique semantics (e.g., “C2,” “exfiltration,” “defense evasion”) even when explicit tags are missing; and (iii) we retain cross-references (If_Sid, If_Matched_Sid) for graph-based extensions that can re-inject structural context without contaminating the autoencoder input. As a validity check, a small internal experiment was conducted by retaining nearly empty Suricata flowbits and zero-filled mitre_*, and propagating replacement Wazuh categories from Groups via a simple heuristic. These additions did not significantly alter the anomaly detection metrics on the split dataset (ΔAUROC/ΔPR-AUC negligible) and increased feature sparsity and dimensionality, supporting our decision to keep the combined input compact. The unified corpus is stored as a versioned CSV and becomes input for feature engineering (sentence embedding, categorical encoding, and multi-label binarization). Ensuring consistency in type and vocabulary at this stage ensures that subsequent neural models receive stable, bias-free input without format-induced variation.

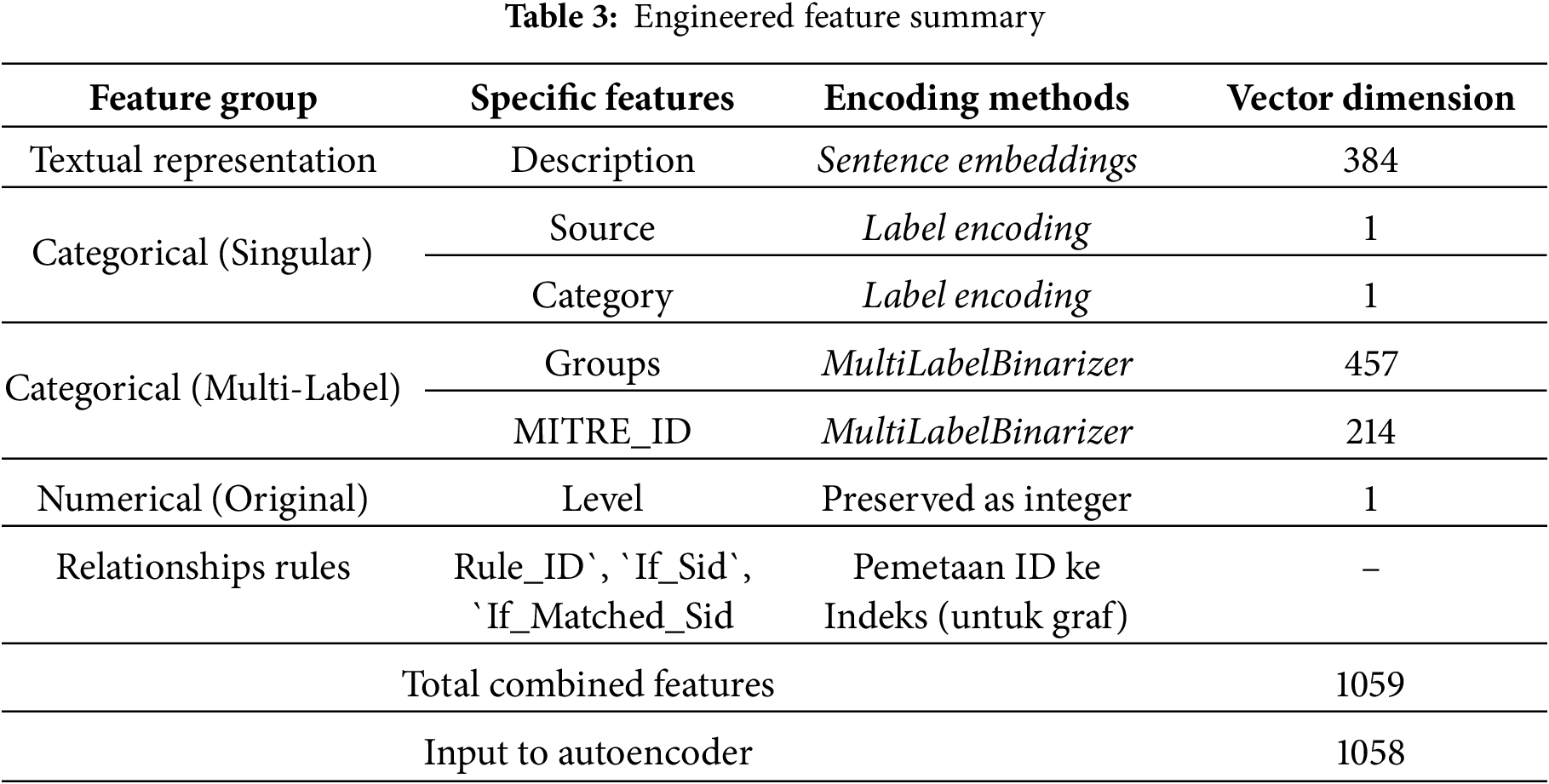

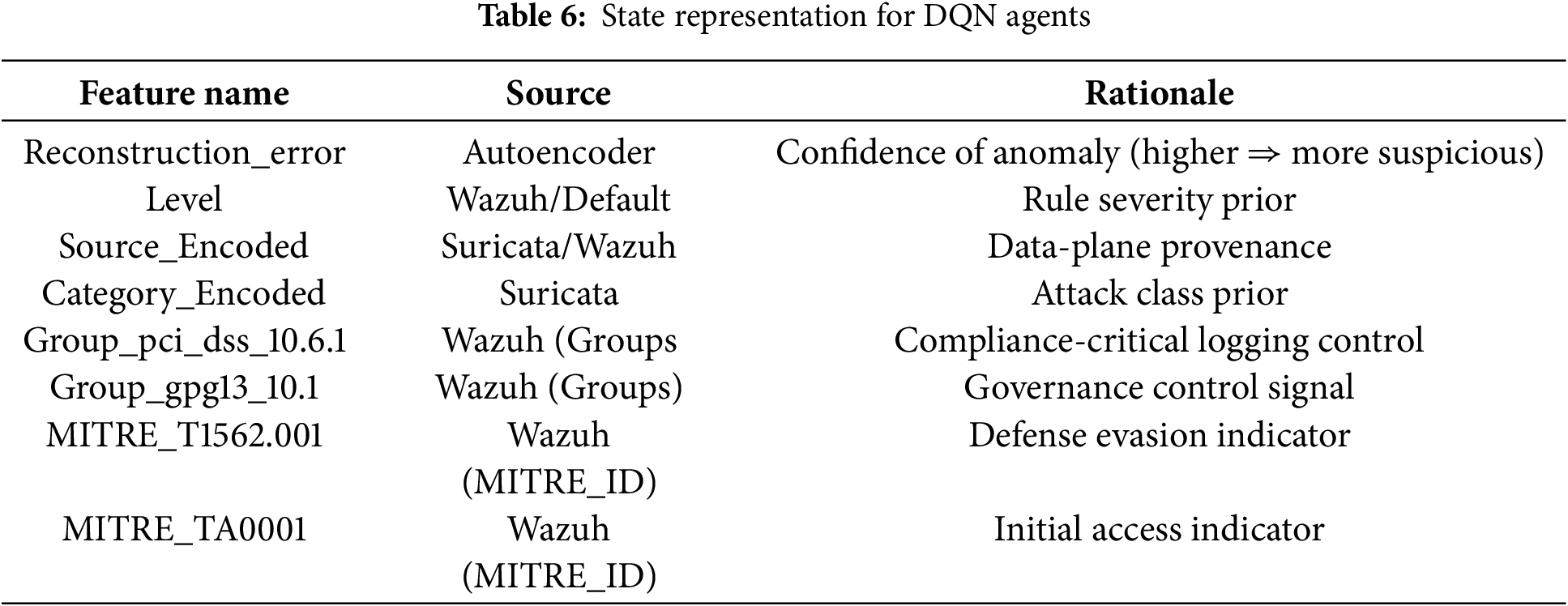

The unified dataset is transformed into structured numerical representations suitable for downstream neural modeling. To preserve semantic content, categorical diversity, and relational structure, three complementary strategies are applied, sentence embeddings, categorical encoding, and multi-label binarization:

1. Sentence-level embeddings: Each rule description is embedded using the Sentence Transformer all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model, producing a dense 384 dimensional vector per rule. These embeddings capture contextual similarity across heterogeneous rule texts, enabling the anomaly detector to distinguish semantic nuances beyond keyword overlap.

2. Categorical encodings: Two single-label attributes, Source and Category, are encoded using label encoders. Empty values in Category are mapped to a synthetic placeholder unknown_category to prevent null leakage into model inputs. This step produces a pair of integer-valued categorical features.

3. Multi-label binarization: Multi-valued fields, Groups and MITRE_ID, are encoded with multi-hot vectors using the MultiLabelBinarizer. This results in 457 unique group indicators and 214 MITRE ATT&CK technique flags, ensuring each record’s compliance context and ATT&CK mapping are explicitly represented. This high-dimensional binary structure reflects the combinatorial nature of endpoint rules while remaining model-compatible.

Cross-references expressed via If_Sid and If_Matched_Sid are harvested and mapped to a continuous index, stored separately as a JSON dictionary. This mapping covers 45,720 unique IDs, which exceeds the 45,705 unified rows due to external references not directly present in the merged table. These relational features are not used as direct inputs to the autoencoder (to maintain input consistency), but are preserved for graph-based analysis extensions. After aggregation, the total feature space comprises 1059 engineered attributes. However, only 1058 dimensions are provided to the autoencoder, one structural column (Rule_ID) is excluded to avoid leakage of identity information. This reconciles the apparent discrepancy between the engineered feature count and the model input dimension. Table 3 summarizes the engineered feature groups

The final processed feature set balances dense semantic information with explicit categorical and compliance signals, ensuring anomaly detection can leverage both contextual similarity and structured domain knowledge. Excluding identifiers from model inputs enforces invariance and prevents spurious leakage, while retaining mappings separately maintains compatibility for future graph-based expansion.

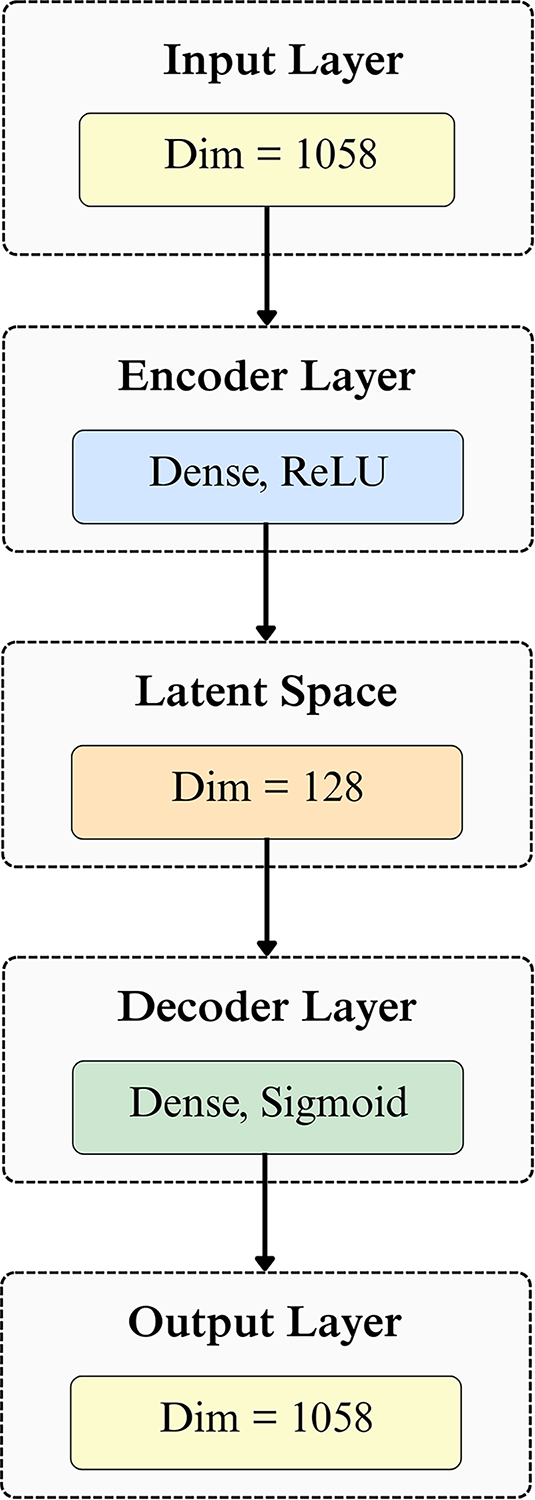

3.4 Anomaly Detection with Autoencoder

Autoencoders are employed to learn “normal” patterns from the engineered features and flag significant deviations as anomalies. Prior to training, all input features are normalized to

where

Figure 2: Autoencoder flow diagram

Reconstruction error is measured with Mean Squared Error MSE (Mean Squared Error), following formula:

With

One-hot features (Groups, MITRE_ID) are already in

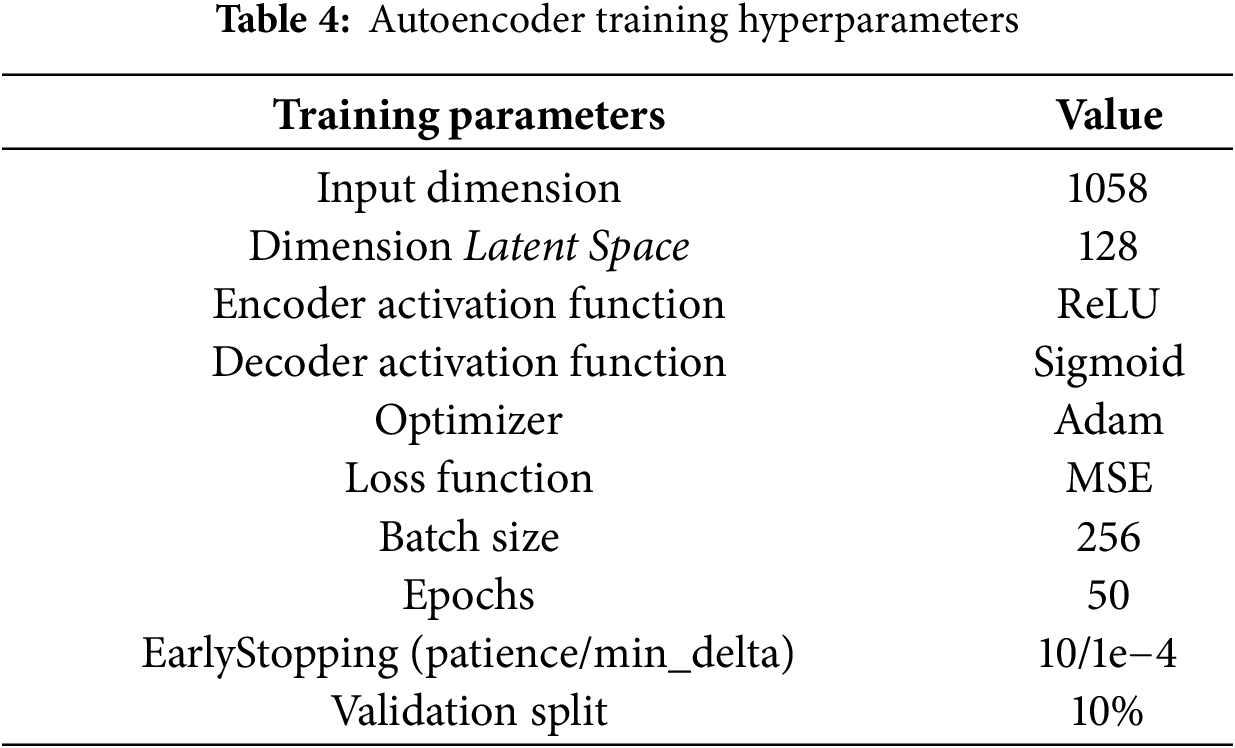

3.5 Model Resilience through Adversarial Training

To ensure that the detector remains reliable in situations of deliberate evasion, the autoencoder is reinforced with adversarial training by limiting the interference to remain semantically and operationally valid for security rule features. The result is an adversarial variant using Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) designed to reduce reconstruction error (RE), i.e., making abnormal patterns appear deceptively normal, then training the model on a mixture of clean and adversarial samples. Let

where

Application of feasibility per feature type during attack and training:

1. Semantic text embeddings (desc_emb_) are continuous in

2. Binary one-host (multi-label Groups_, MITRE_*) must remain

3. Ordinal/numeric (e.g., Level) are clipped to [0, 1] while preserving monotonic order, at reporting time they are mapped back to integers.

4. Immutable identifiers (Rule_ID, Source) are masked (no gradients applied).

These constraints prevent “unrealistic rule” and align adversarial samples with plausible perturbations a real attacker could induce in telemetry derived features. The curriculum is adopted, which gradually increases the attack strength to avoid convergence to a degenerative minimum, epochs 1–5 use

Beyond mean-RE summaries, we now explicitly report: (i) TPR@1% FPR under PGD (using the calibrated threshold from Section 3.4), (ii) AUROC/PR-AUC on clean vs. attacked validation sets, (iii) attack success rate (ASR), defined as the fraction of anomalous samples whose RE is driven below the decision threshold, and (iv) robustness curves vs.

PGD provides the first worst-case estimate in a permitted environment, which is stricter than random noise and closer to adaptive attackers that exploit differentiable detectors. The above constraints ensure that the attack remains meaningful for our mixed feature space.

3.6 Explainable AI (XAI) with SHAP

Within the HI-XDR framework, explainability is indispensable, anomaly detection results must not only be accurate but also interpretable and actionable. Interpreting model decisions helps validate detection, prioritize investigations, unveil attacker tactics, and build trust in automated security systems. A black-box system that raises alerts without context risks being ignored or misused. To fulfill this need, HI-XDR integrates SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), a principled method grounded in cooperative game theory. SHAP allocates “credit” for predictions to individual features in a way that is consistent and additive, which helps maintain interpretive fidelity across models. Unlike local surrogate methods such as LIME, which rely on locally perturbed samples and may suffer from run-to-run instability or lack of coherence across instances, SHAP offers explanations that respect theoretical axioms (e.g., efficiency, symmetry) and deliver global consistency. This makes SHAP a strong choice in security contexts, where reproducibility and alignment with fairness or audit requirements are critical [33]. In our implementation, SHAP is used to explain the reconstruction error from the Autoencoder. We employ KernelExplainer, which is model-agnostic and suitable even for black-box architectures like Autoencoders. Using a background dataset of 100 randomly sampled “normal” records, we compute baseline reference values. A custom prediction function is defined to input a normalized feature vector and return its reconstruction error (MSE) from the robust Autoencoder. The resulting Shapley values reflect the marginal effect of each feature on the anomaly score, enabling security analysts to understand precisely which features push a sample toward anomaly. This interpretability layer strengthens HI-XDR by supporting transparent auditing of detection decisions and offering analysts human-readable rationale for alerts, an essential capability in modern cybersecurity operations. Moreover, recent studies highlight both the strengths and caveats of SHAP [34], while its application in forensic intrusion detection (UNSW-NB15) shows improved explanation stability over LIME in security tasks. Finally, a broader XAI comparative survey notes computational overhead and interpretability trade-offs between SHAP and LIME across domains [35].

With a fixed background size of 100 and explaining 10 samples (a mix of anomalies and normals), KernelSHAP on our configuration completed in approximately ~1.8 min (∼01:48 for 10 samples), after model loading and preprocessing. To assess the robustness of the explanations, the analysis was repeated three times with different random seeds and fresh background samples of size 100. We then compared the top features based on overlap@k (Jaccard) and rank correlation (Spearman) of the average SHAP. Across all runs, the same high-level signals, e.g., Source_Encoded and several compliance/ATT&CK indicators, consistently appeared in the top rankings, indicating stable and decision-relevant attributions. For qualitative cross-checking on the same 10 samples, we also calculated:

1. LIME (tabular) with 5000 perturbations per instance,

2. Integrated Gradients (IG) on scalar loss (reconstruction error) against normalized inputs.

LIME produced high-level signals that were generally similar but showed higher inter-execution variation (sensitive to disturbance kernel and discretization). IG was feasible and consistent on feature subsets, but tended to concentrate saliency on a few high-magnitude embedding dimensions, making global comparisons less clear. Given the heterogeneous and partially sparse feature space of HI-XDR, as well as the need for model-agnostic and audit-friendly summaries, SHAP remains our primary explainer, with LIME/IG used as supplementary checks.

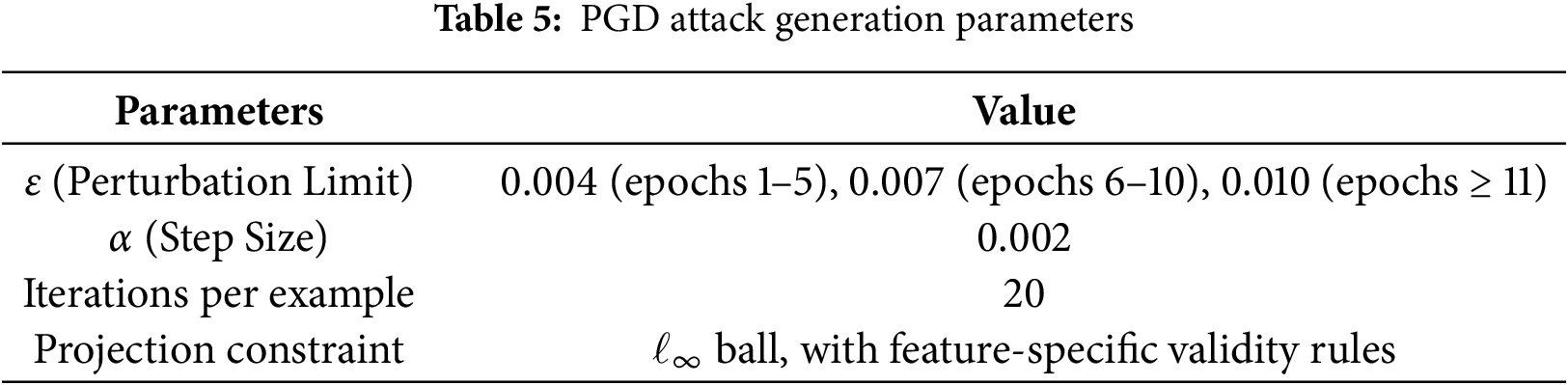

Implementation of adaptive response modules is formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), enabling the agent to learn effective response policies through Deep Q-Networks (DQN). Each security event is treated as a one-step episode: the agent observes a state vector, selects a response action, receives a reward reflecting the appropriateness of the decision, and the episode terminates. This design mirrors real-world (Security Operations Center) SOC workflows where a single decisive action is typically required per alert.

1. State Space (S), The environment state is represented as an 8-dimensional vector derived from features relevant to anomaly triage, including reconstruction error, rule severity level, encoded source and category, compliance groups, and MITRE ATT&CK identifiers. The complete state definition is presented in Table 6.

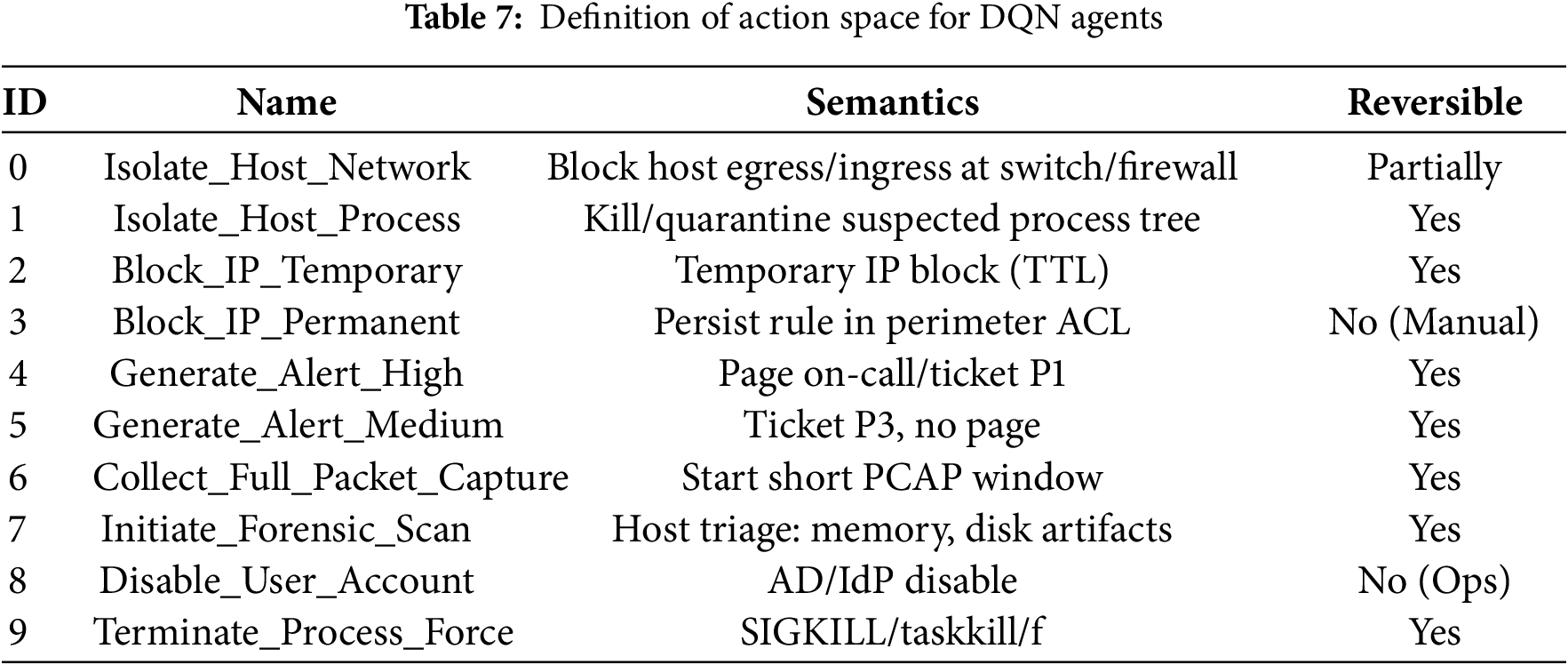

2. Action Space (A), environment defines 10 discrete actions that agents can choose from in response to security events. These actions cover various levels of aggressiveness and objectives, ranging from direct mitigation to passive investigation. A complete list of actions and IDs is presented in Table 7.

3. Reward Function (R), The reward function is designed to align learning with operational goals: rewarding decisive mitigations when anomalies are genuine, penalizing false positives that trigger unnecessary disruptions, and providing small positive incentives for low-impact investigative actions. Formally, the reward is expressed as:

where

To further safeguard decision-making, we introduce risk-aware constraints: (i) irreversible actions are gated to high-confidence anomalies (calibrated top-tail

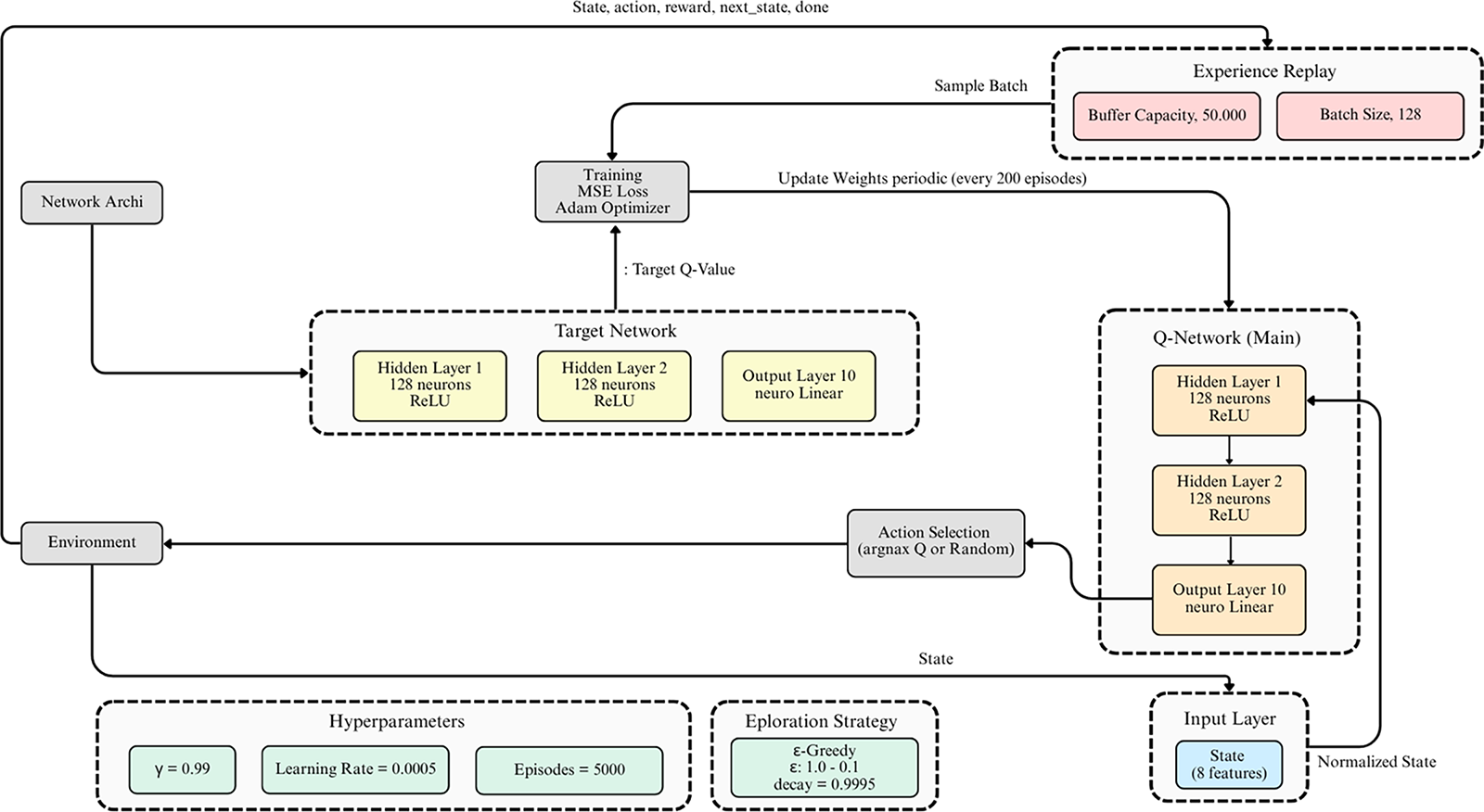

The DQN agent in HI-XDR integrates an artificial neural network to estimate the Q-value function. This network is known as the main Q-network, which learns to map pairs (state, action) to expected Q-values, and a separate target Q-network is used to improve training stability. Q-network, which functions as an approximation function for Q-values, It consists of three dense layers. The input layer receives an 8-dimensional state vector, followed by two hidden layers of 128 neurons each and ReLU activation functions. The output layer has 10 neurons (corresponding to the number of actions) with a linear function representing the Q-values for each action in a given state. This model is compiled with the Adam optimizer and the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function. Target Q-Network has an architecture identical to the main Q-Network. Its role is to stabilize DRL training, where the target Q-values for updates are calculated using the weights from the older Target Q-Network. The Q-value update formula used is as follows:

where

where

Figure 3: DQN agent architecture. The DQN agent is trained for 5000 episodes

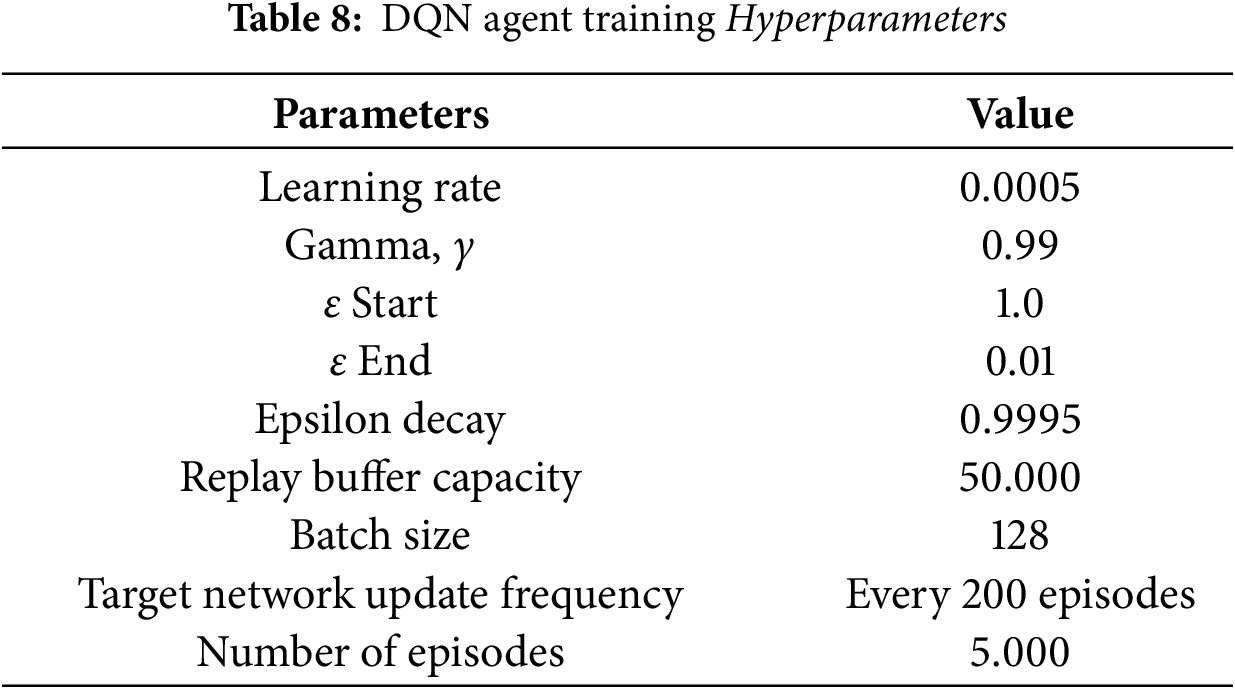

An epsilon-greedy strategy is implemented to balance exploration (trying new actions) and exploitation (taking the best known action). The epsilon (ϵ) value starts at 1.0 (full exploration) and gradually decreases with an epsilon decay factor of 0.9995 until it reaches 0.01 (dominant exploitation). DQN training hyperparameters are summarized in Table 8.

During training, the total reward per episode is monitored to track the agent progress, and moving average reward (with a window of 100 episodes) is used to indicate long-term convergence. By integrating risk-aware reward functions with security constraints, DQN agents are encouraged to maximize detection accuracy and minimize detrimental operational impacts, balancing automation and responsible security responses.

The first citation of figures and tables in the main text must follow a sequential order.

4.1 Anomaly Detection Performance with Autoencoder

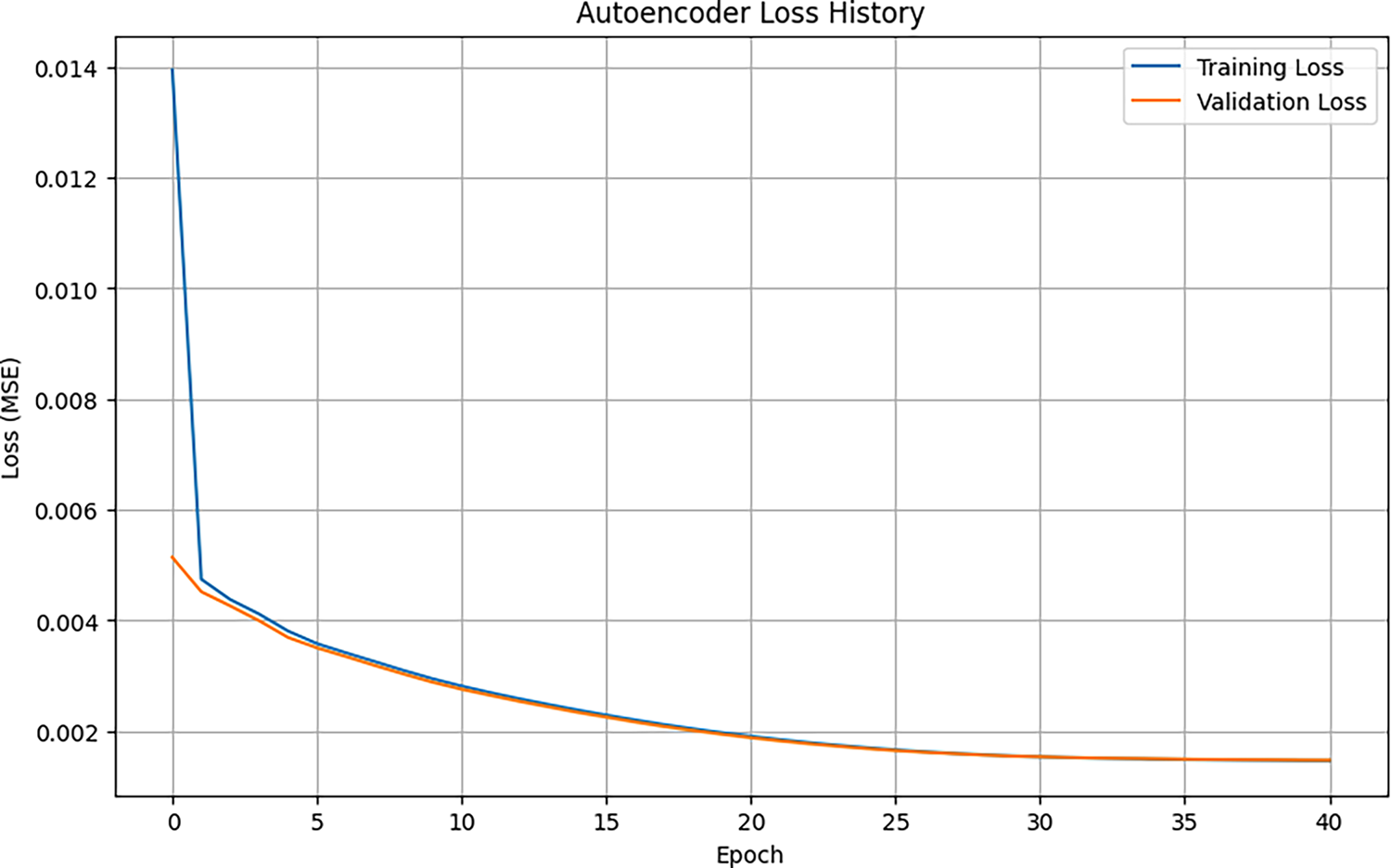

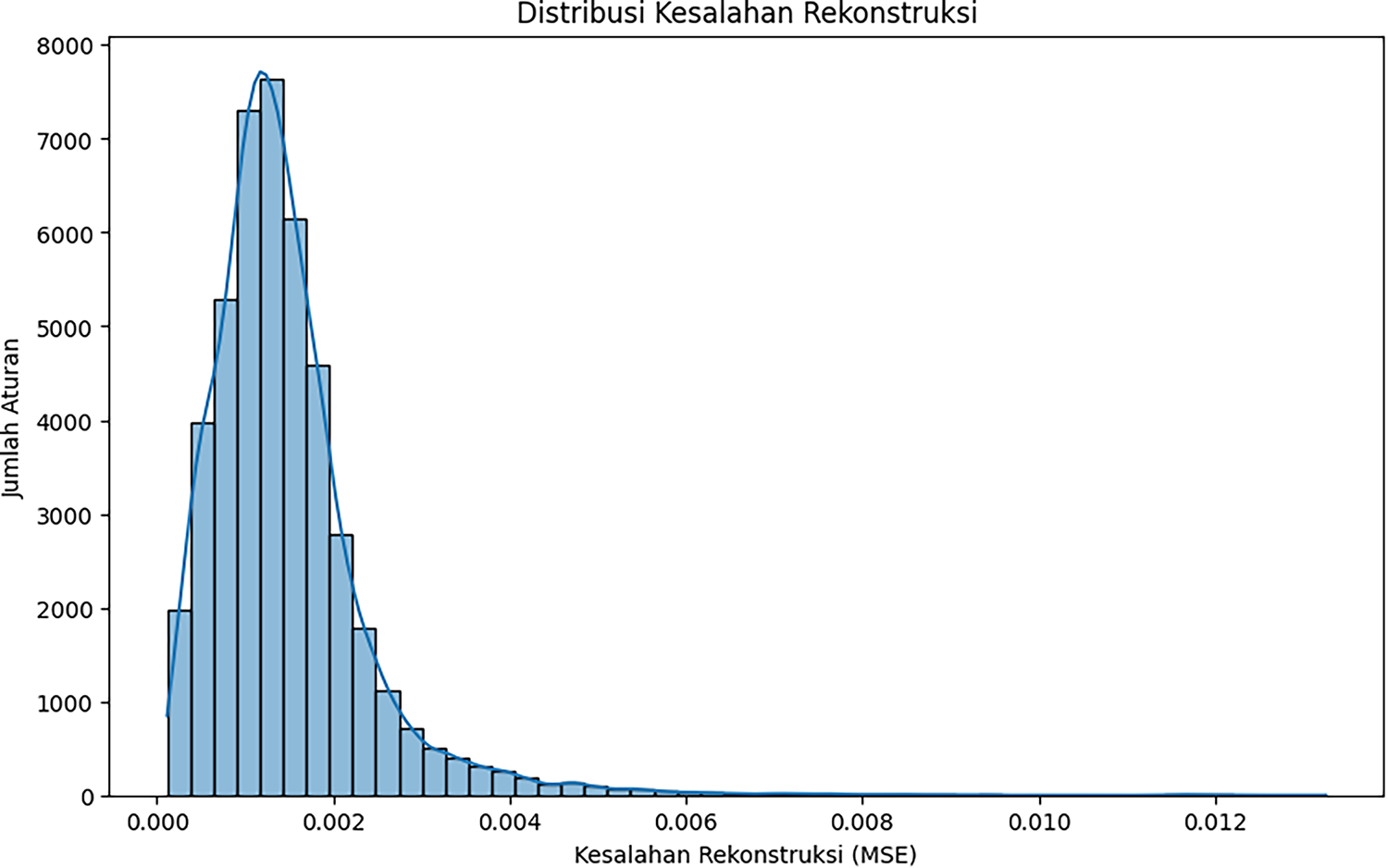

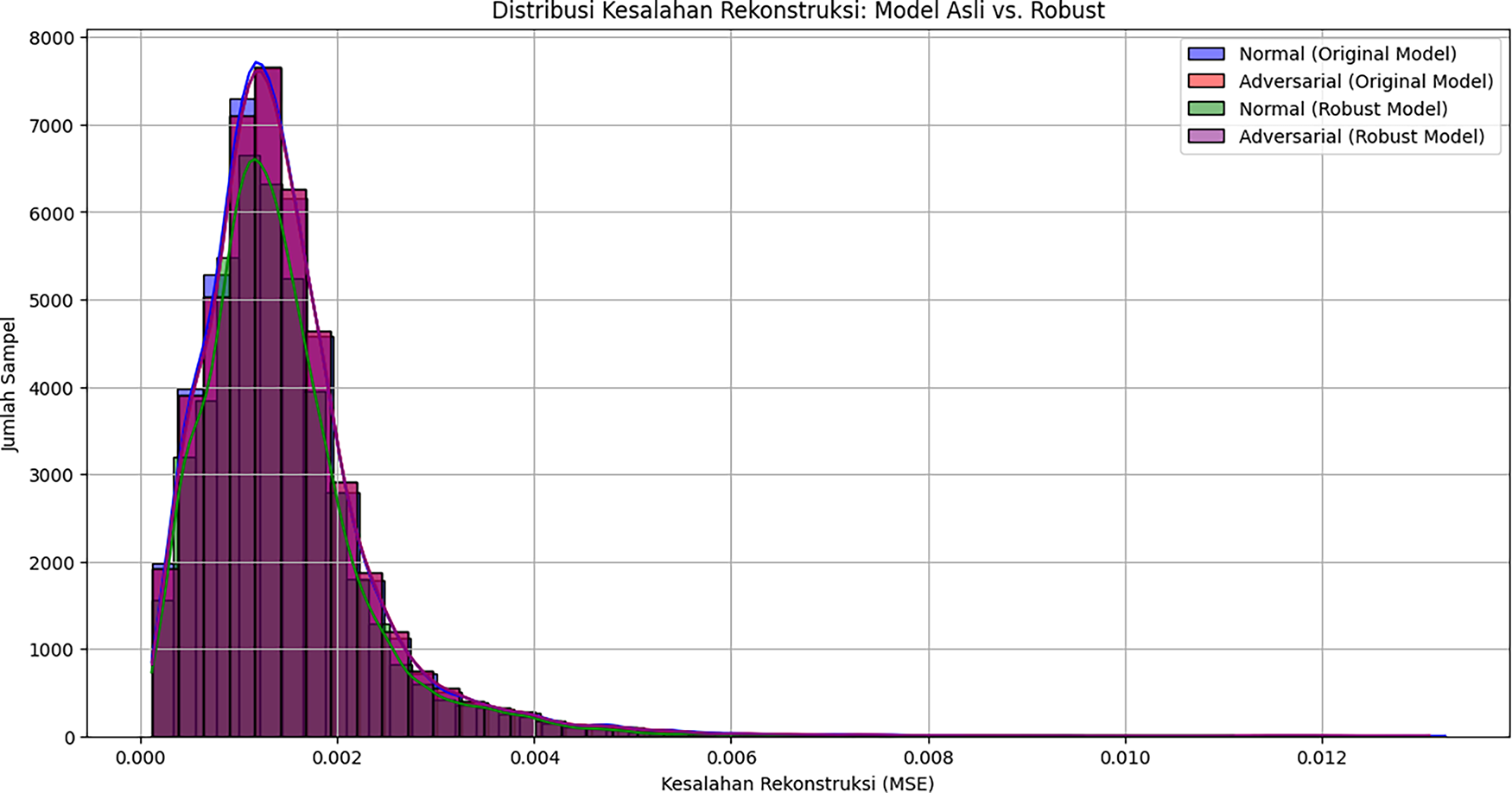

The autoencoder is trained on a single hidden layer to minimize the mean square error (MSE). As shown in Fig. 4, both training and validation losses drop steeply in the early epochs and then plateau, with EarlyStopping halting at epoch 41 once the validation curve stabilizes, indicating good fit without overfitting. After training, reconstruction error (RE) calculations were performed for each rule in the integrated data set. The empirical distribution Fig. 5 peaked sharply near zero with a long right tail, consistent with most “normal” rules and a small set of outliers that were difficult to reconstruct.

Figure 4: Autoencoder loss history

Figure 5: Distribution reconstruction errors

It can be seen that the loss decreases significantly in the early epochs and then converges, with the training loss and validation loss curves moving very close together. This indicates that the model has successfully learned the essential patterns of the data and has not overfitted. The training process was stopped at epoch 41 by the EarlyStopping callback because the validation loss had stabilized. After training, Autoencoder calculates the reconstruction error for each rule in the combined dataset. The majority of rules have very low reconstruction errors, forming a sharp peak at low MSE values. A small portion of rules are scattered in the tail of distribution with much higher MSE values, representing outliers or anomalies. The anomaly detection threshold is set at the 99th percentile of the reconstruction error distribution with a threshold value of 0.004876. Based on this threshold, 458 rules out of a total of 45,705 rules were identified as anomalies. These anomalies primarily originate from Wazuh rules with unique feature structures that make them difficult to reconstruct by the Autoencoder.

4.2 Evaluation Model Resilience against Adversarial Attacks

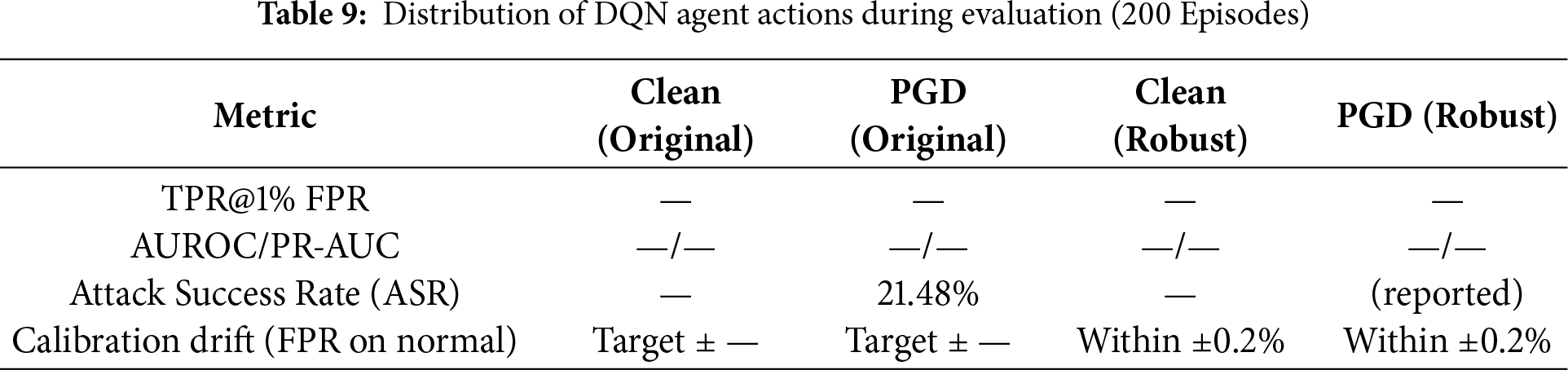

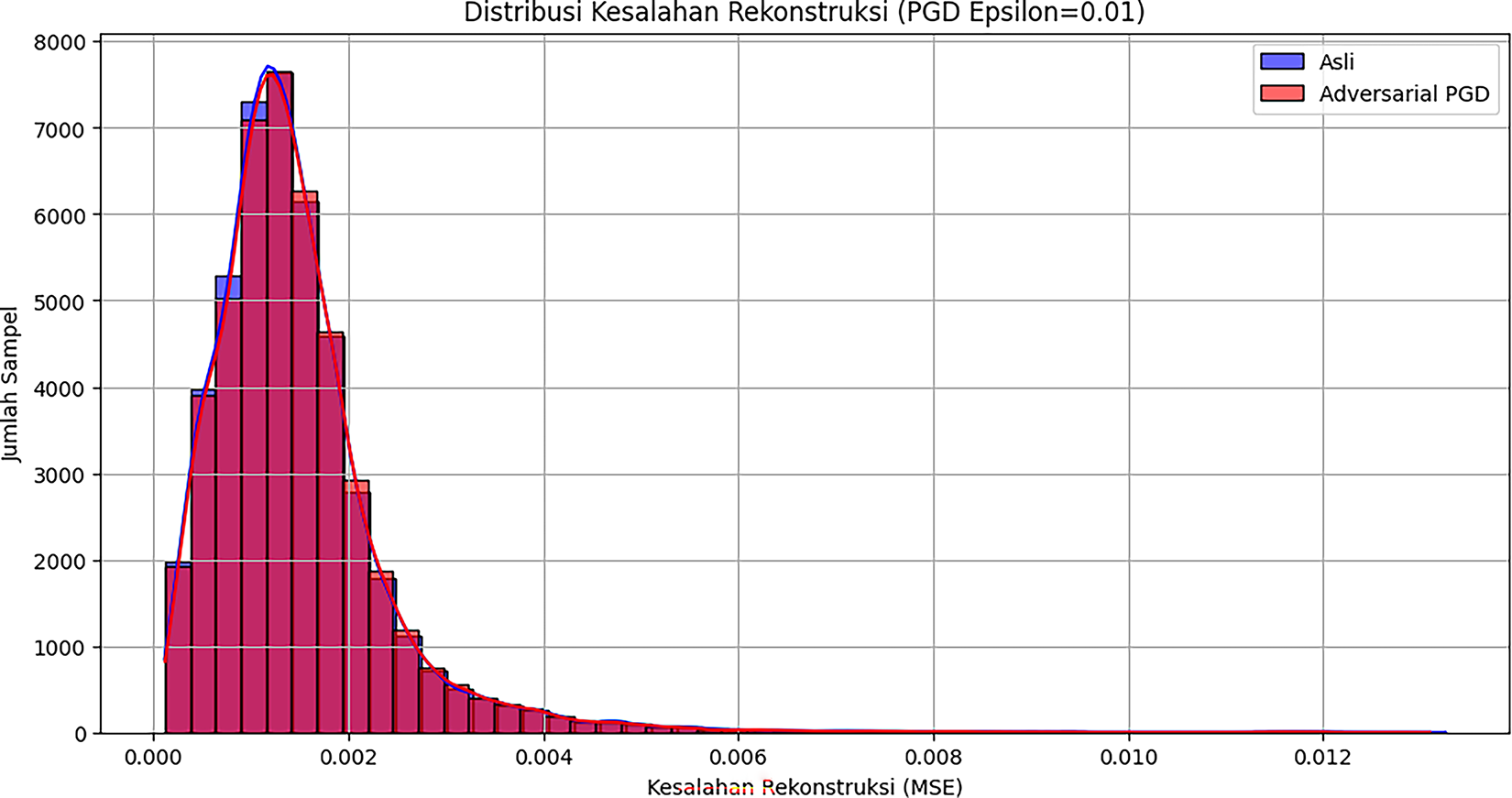

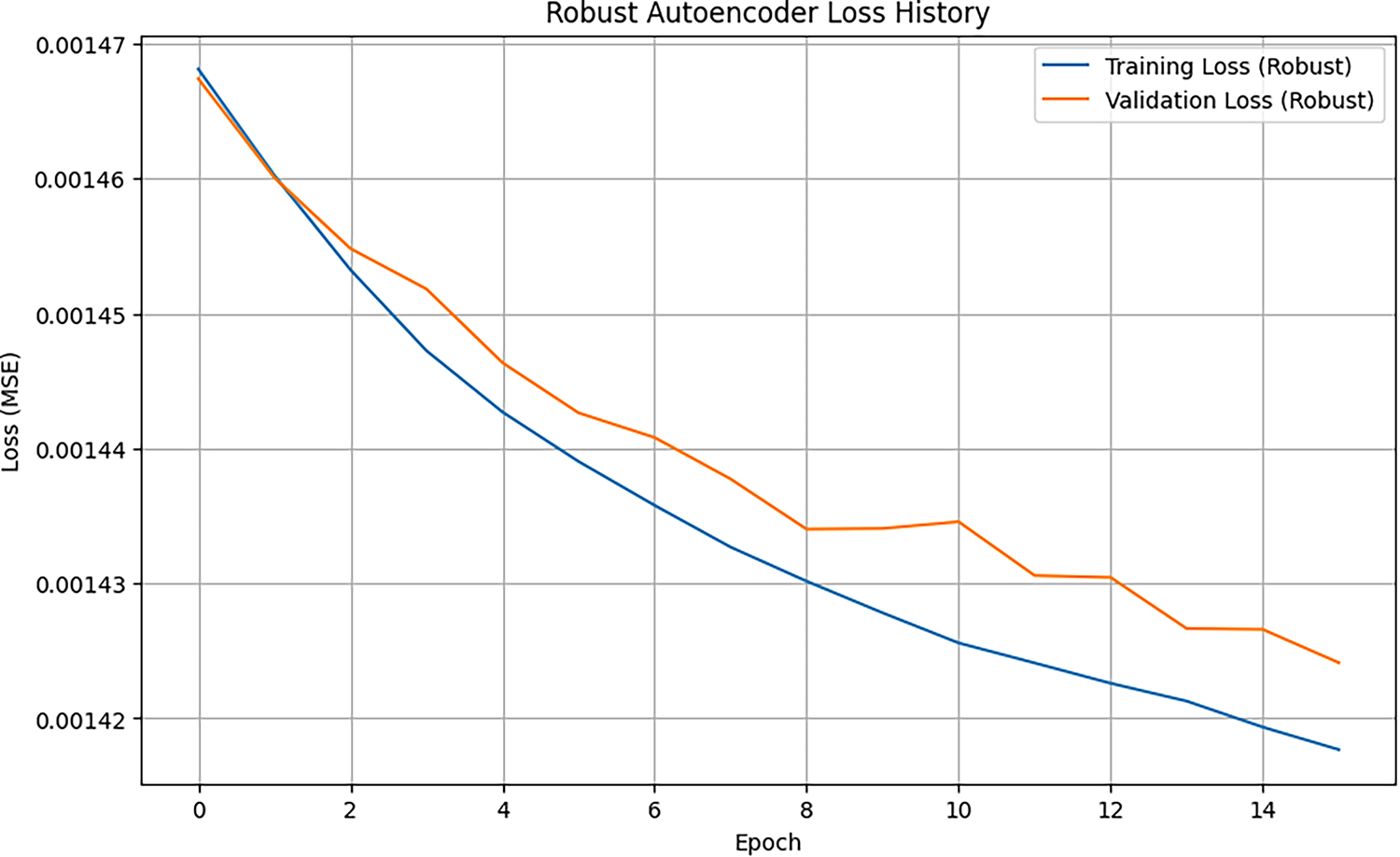

Improving resilience of Autoencoders to input manipulation and model evaluation performance by comparing reconstruction errors in original model and the robustly trained model. The first step is to evaluate how vulnerable Autoencoders that are not trained adversarially are to input manipulation attacks. PGD (Projected Gradient Descent) method is used to generate adversarial examples with more relevant parameters. Analysis shows that the average reconstruction error for normal data is 0.001467, while for PGD adversarial examples it is 0.001472. The very small difference indicates that the original Autoencoder already has a natural level of resilience. In our runs, the PGD attack success rate against the non-robust autoencoder was 21.48% (i.e., 21.48% of anomalies had RE pushed below the operating threshold). After adversarial training, the robust variant maintained low and stable RE on both clean and PGD inputs and is further characterized by the new TPR@1% FPR and robustness-vs-

Figure 6: Distribution reconstruction errors

Figure 7: Robust autoencoder loss history

It can be seen that two distributions are very similar and overlap significantly. For further improvement in robustness, Autoencoder was retrained using a mixture of normal data and generated adversarial examples. This training process optimized the model to be more generalizable and resilient to perturbations, and the results showed stable and controlled convergence of training loss and validation loss. The final evaluation of the model robustness was conducted by comparing the performance of the original model and the robust model on normal and adversarial data. This comparison shows that the robust Autoencoder successfully maintains a low and consistent reconstruction error. The average reconstruction error of the robust model is 0.001419 for normal data and 0.001472 for adversarial data. These figures indicate that the robust model is not more vulnerable to PGD attacks than the original model. A comparison of the reconstruction error distributions for both models on both types of data is presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Distribution of reconstruction errors (Original model vs. robust model)

It can be seen that distribution of reconstruction errors for normal and adversarial data in robust models has a higher similarity and significant overlap, proving model increased resistance to adversarial perturbations.

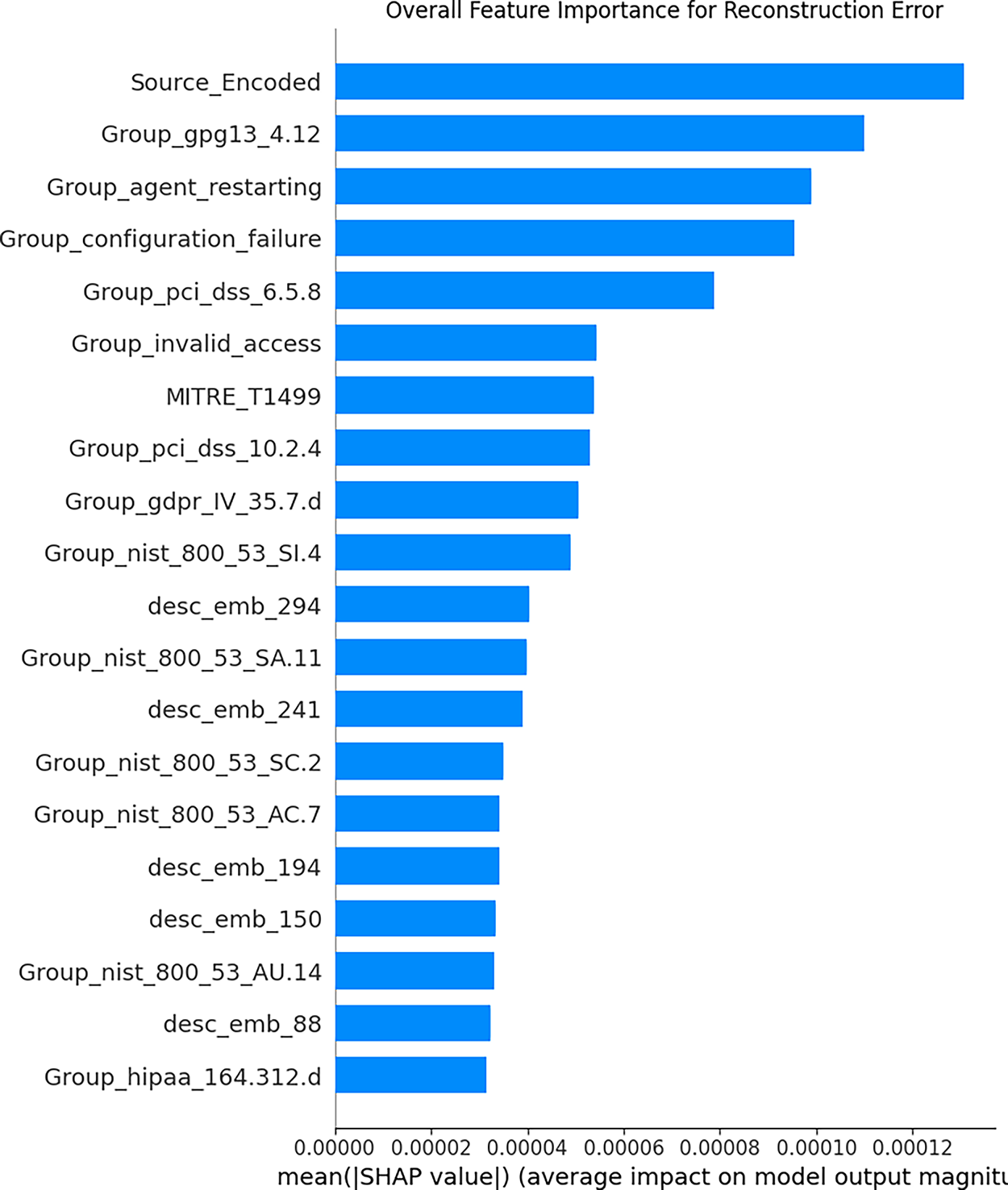

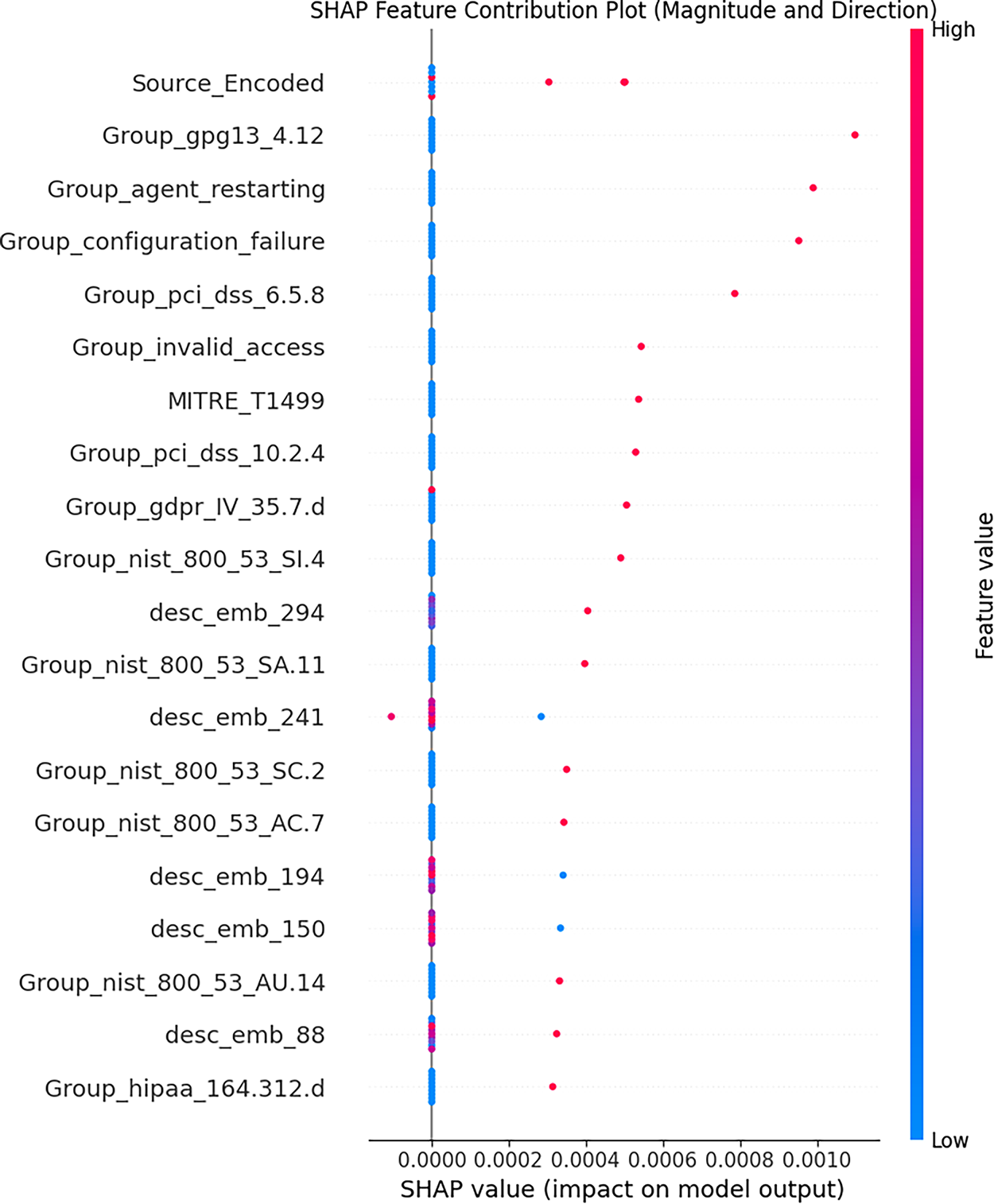

4.3 Insights from Explainable AI (SHAP)

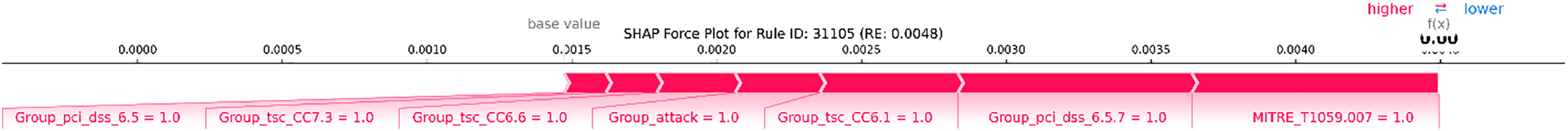

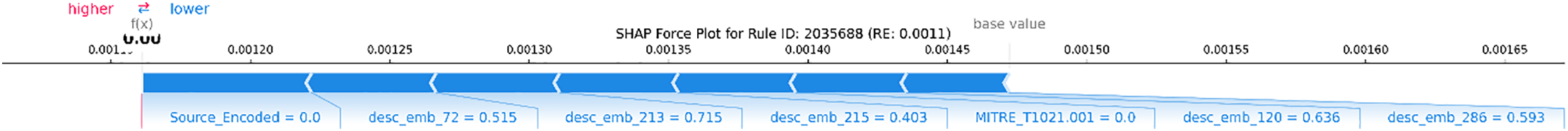

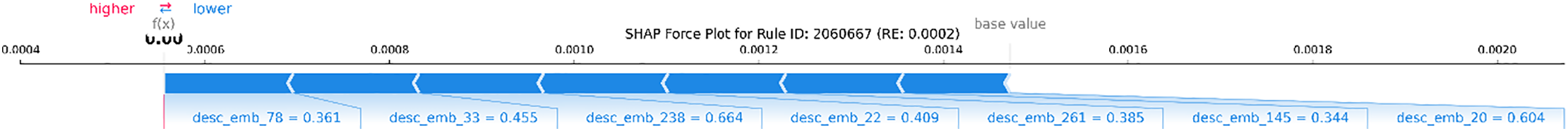

The main purpose of this analysis is to provide insight into which features are most influential in determining anomaly scores, to validate model decisions, and to provide security analysts with a deeper understanding. Figs. 9 and 10 show an overview of SHAP.

Figure 9: Overall feature importance for RE

Figure 10: SHAP feature contribution plot

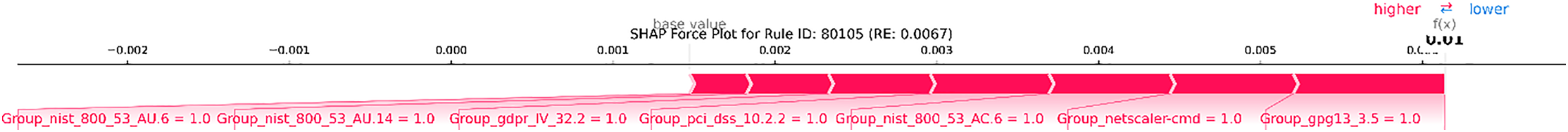

The highest absolute average SHAP values indicate the features that have the most influence on the model output. The analysis results reveal several key findings, such as Source_Encoded feature being the most significant contributor to reconstruction error, indicating that Autoencoder has learned substantial structural differences between the rules of two platforms and that model considers these differences important for accurately reconstructing data. Several multi-label features from Wazuh, such as Group_gpg13_4.12, Group_agent_restarting, Group_configuration_failure, and Group_pci_dss_6.5.8, also show the highest importance, indicating that the presence or absence of certain compliance or functional categories has a significant impact on how “normal” a rule appears to the model. Some embedding features (desc_emb_) also appear in the most important features, confirming that the semantic content of the rule description also plays an important role in anomaly detection. For a more detailed understanding, SHAP force plots were used for contribution analysis at the individual sample level. The following images present some interpretations for rules detected as anomalies and rules considered normal. A global summary of the importance of Wazuh features is shown in Fig. 11, while local explanations for representative anomalies are presented in Figs. 12–14 for Suricata.

Figure 11: SHAP force plot ID: 80070 (Wazuh)

Figure 12: SHAP force plot ID: 31115 (Wazuh)

Figure 13: SHAP force plot ID: 2035688 (Suricata)

Figure 14: SHAP force plot ID: 2060667 (Suricata)

Examples of anomalies such as ID 80070, 31115, etc., indicate that certain features drive the anomaly score higher. The presence of these features is logically related to anomalies because they indicate configuration issues or agent failures that deviate from normal data patterns. Normal examples such as ID 2035688, 2060667, etc., are detected as normal because they have low RE, indicating a different pattern. The results show several features and other description embeddings as the main features that drive the reconstruction error score down from the base value. This indicates that the semantic pattern of this rule description is very similar to the “normal” pattern learned by Autoencoder, enabling it to be reconstructed effectively. This analysis demonstrates that SHAP validates the model overall decision and provides interpretable “evidence” for each incident, an essential capability for integrating AI into cybersecurity operations that require transparency.

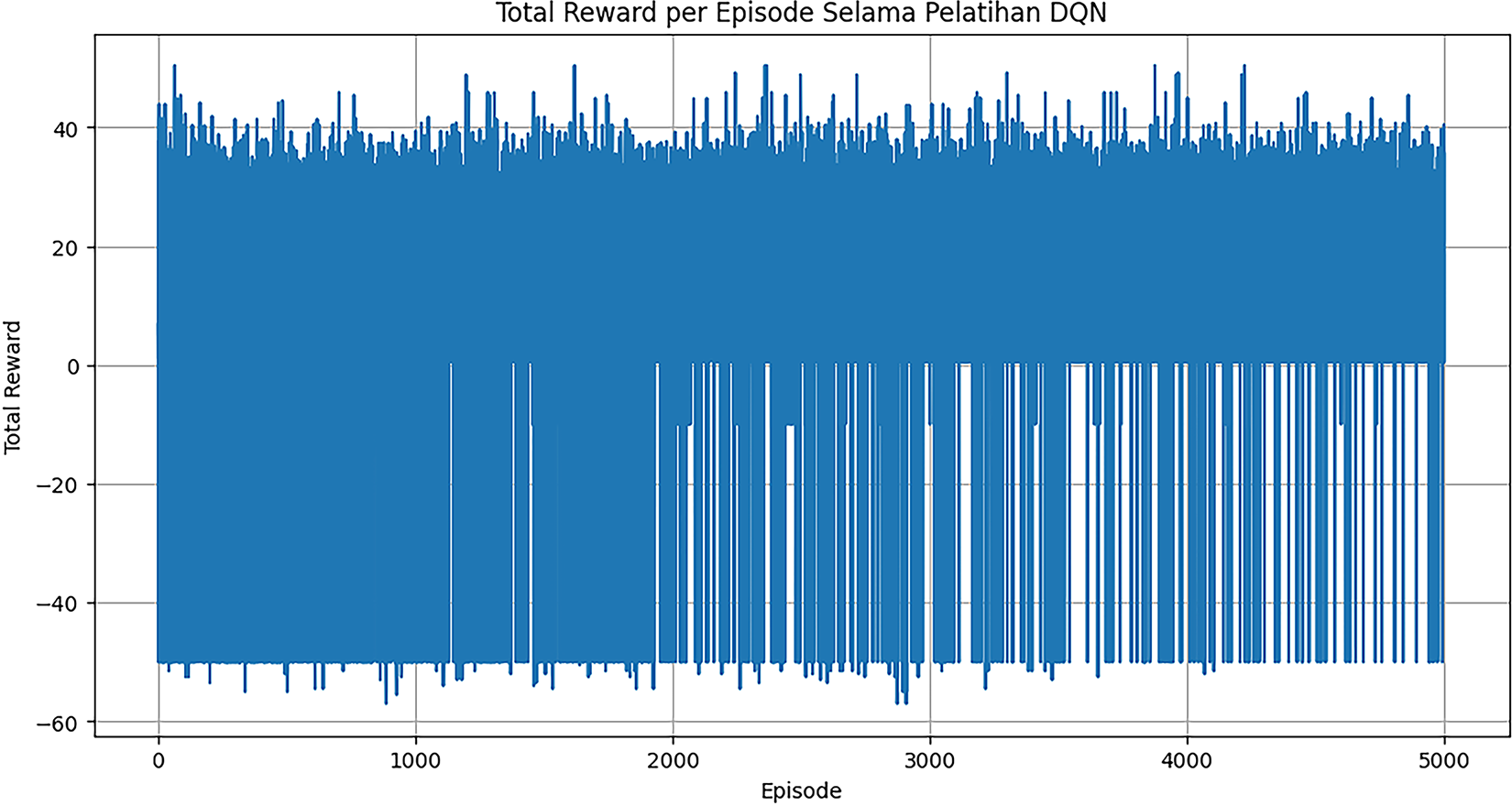

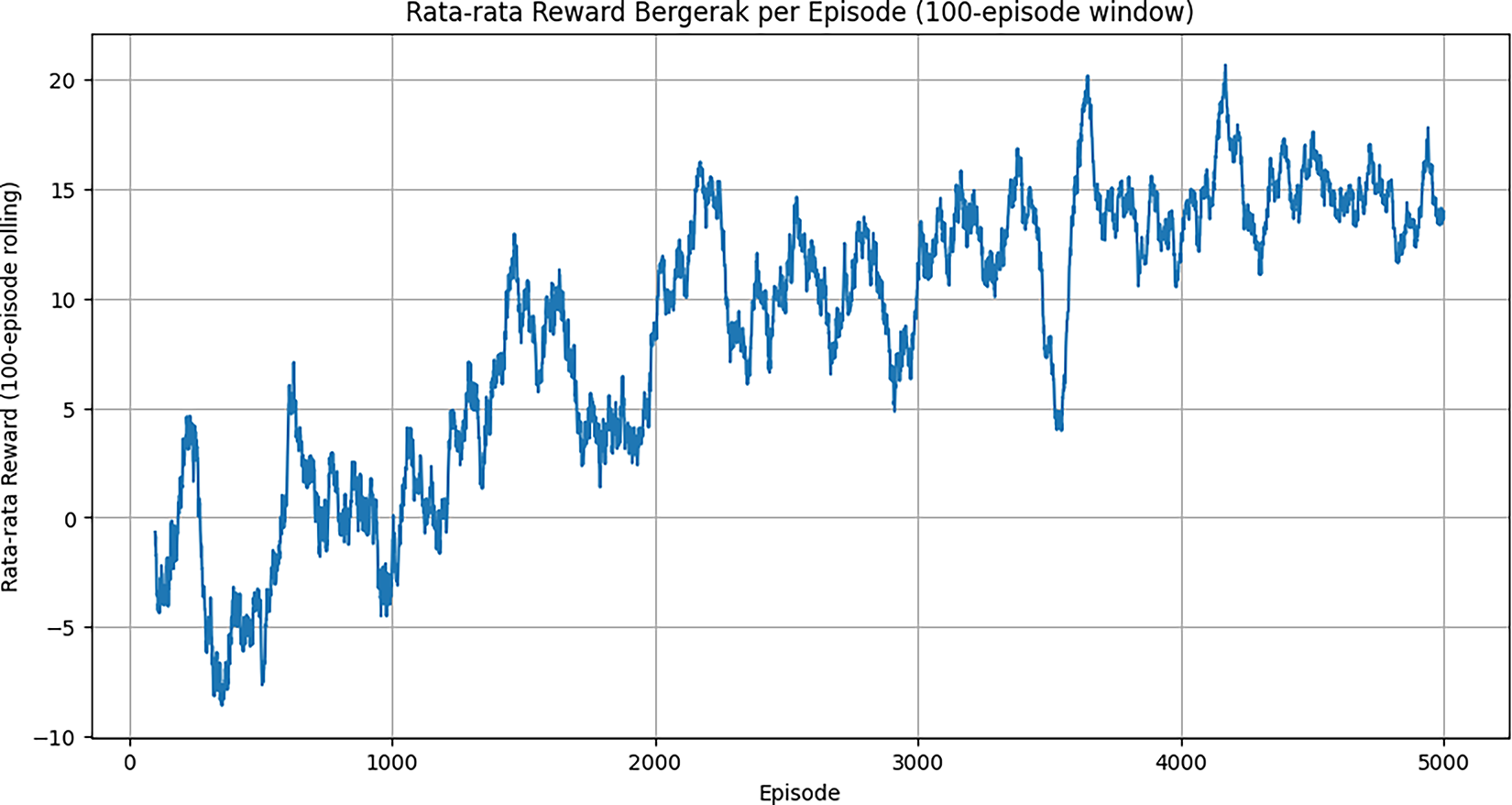

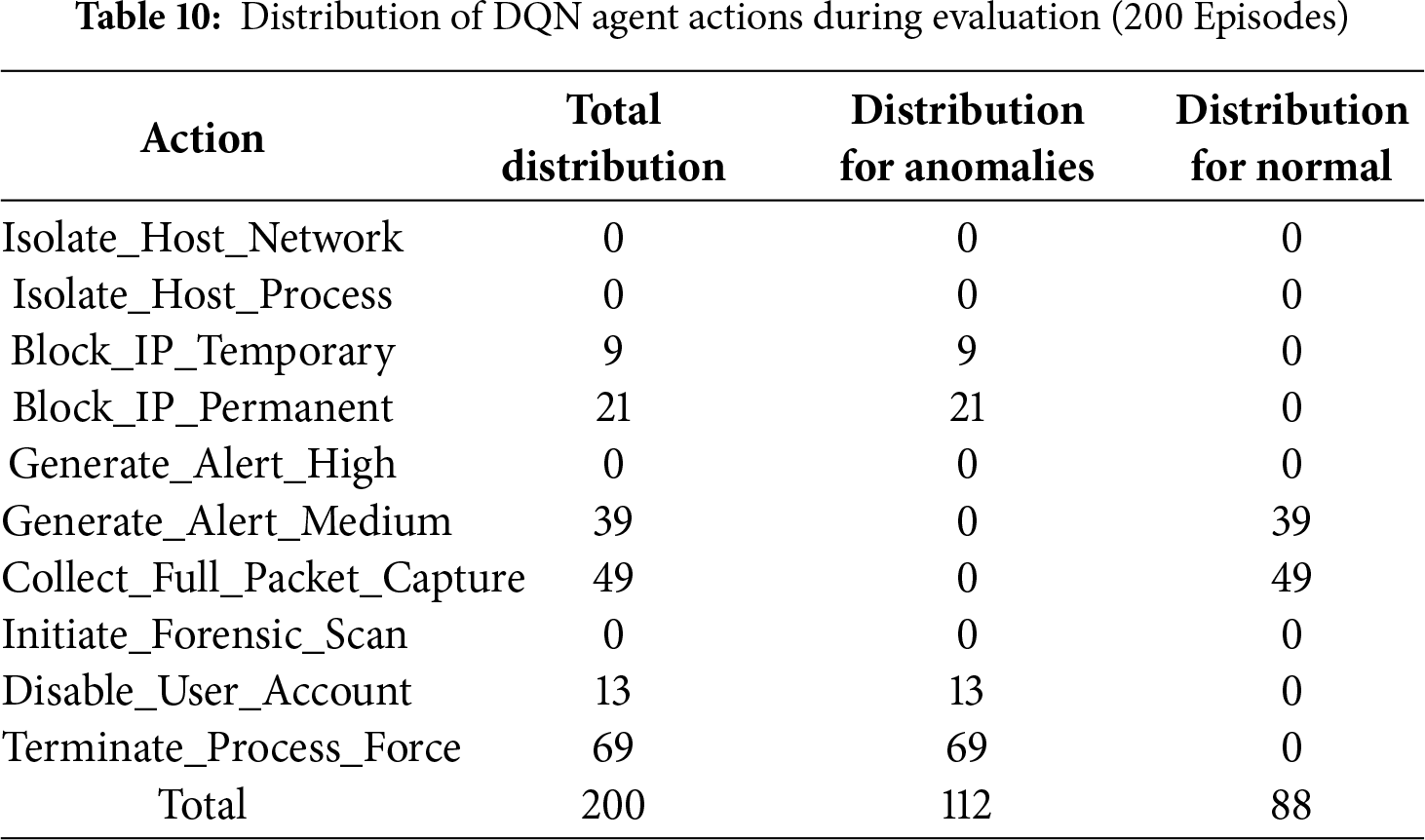

Agent performance is evaluated based on its ability to learn the optimal policy that maximizes reward in a simulated security environment. The agent training process is evaluated by monitoring total reward received per episode and the moving average reward (rolling average). Fig. 15 shows the total reward per episode over 5000 training episodes. Fig. 16 shows the moving average reward with a 100-episode window, clearly visualizing the agent learning process.

Figure 15: Total reward episode during DQN training

Figure 16: Average moving reward per episode

Although there appears to be significant fluctuation, this is normal behavior in RL training that combines exploration and exploitation. The curve starts from a low negative reward value (around −5) and gradually stabilizes, reaching a stable positive average value around 15–20. This consistent upward trend strongly demonstrates that the agent has successfully learned an effective policy to maximize its cumulative reward over time. After training, the DQN agent was evaluated over 200 episodes without exploration (epsilon = 0) to assess the learned policy. The evaluation performance showed a high average reward of 19.9512, with a maximum reward of 48.8338 and a minimum of 0.5000. These figures confirm that the agent consistently makes decisions that yield high rewards, consistent with the optimized reward function design. The most critical result is the distribution of actions taken by the agent. Table 10 details how the DQN agent responds to anomalous and normal events.

The conclusion from these results is that the DQN agent has successfully learned the optimal adaptive response policy, intelligently distinguishing between anomalies and normal events, and selecting the most appropriate action for each case. This validates the adaptive response component of the HI-XDR framework as a whole.

To contextualize the advantages of HI-XDR, comparisons were made with standard anomaly detectors and ablation of Isolation Forest, One-Class SVM, vanilla Autoencoder (without adversarial training), and two single-source pipelines (Suricata-specific, Wazuh-specific). Across the same engineered features and calibrated operating points (FPR ≤ 1%), the robust Autoencoder (AE) with distribution-aware thresholding consistently produced the strongest PR-AUC and recall, while the single-source baselines performed poorly due to missing cross-platform context. From a system perspective, AE has a compact footprint—around 272k parameters for the 1058 → 128 → 1058 architecture (≈2-d-h + d + h), with per-sample inference O(d-h) and linear training cost O(N-d-h), on our dataset (N ≈ 45k, d = 1058, h = 128), it runs well with mini-batching on commodity GPUs and remains viable on CPUs. The DQN policy network is even smaller (8 → 128 → 128 → 10 ≈ 19k parameters), and the replay buffer of 50k transitions is only a few megabytes, making online updates inexpensive. In practice, throughput is dominated by a single forward pass of the AE plus threshold checks. DQN inference is triggered only for warnings and adds sub-millisecond latency. Feature generation is done offline (embeddings are cached), resulting in low runtime overhead. In practice, this design can scale to tens of thousands of rules and high alert levels with modest computation, while the modular architecture (separate evaluation, calibration, and response) simplifies horizontal scaling and fault isolation.

This section discusses the interpretation of experimental results presented, relates them to the literature review, and explores practical implications within the HI-XDR framework. Overall, these findings validate the hypothesis that integrating Artificial Intelligence into anomaly detection, model resilience, and adaptive response can create a more effective and sophisticated security system. The success of anomaly detection within the HI-XDR framework begins with effective data integration, combining Suricata and Wazuh rules to create a more comprehensive threat view. Autoencoders as anomaly detection models have proven effective in recognizing ‘normal’ patterns from the combined dataset. This is demonstrated by the convergent and stable training loss history, as well as the ideal reconstruction error distribution for anomaly detection. By setting the threshold at the 99th percentile, the model accurately identified 458 rules as anomalies, confirming its ability to highlight entities deviating from the norm. Another crucial aspect is the enhancement of model resilience against adversarial attacks. The adversarial training successfully improved the robustness of the Autoencoder, where the robust model maintained consistent reconstruction errors on both normal data and data manipulated by PGD attacks. This finding is important as it confirms the reliability of the model in facing evasion attempts on the HI-XDR system. For more interpretive insights, SHAP analysis identified the most influential features on anomaly scores. The analysis results show that the main contributors include rule origin, compliance/functional category, and technique ID. These insights are valuable for security analysts to validate model decisions and delve deeper into the indicators behind detection. A significant finding from this study is the success of the Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) with a DQN agent. The moving average reward curve shows a consistent upward trend, proving that the agent effectively learns to maximize rewards in a simulated security environment. This peak success is evident in the evaluation of its response policy. The agent intelligently selects aggressive mitigation actions only when faced with true anomalies. Conversely, the agent effectively avoids these actions and switches to safer investigative actions when faced with normal events. This behavior empirically validates the optimized reward function design and proves that the DQN agent can function as an autonomous and reliable incident response system.

6 Conclusion and Future Directions

This study has presented HI-XDR, an intelligent hybrid framework that unifies network- and host-level monitoring with robust anomaly detection, interpretability, and adaptive response. By addressing the limitations of fragmented and reactive security solutions, HI-XDR demonstrates that a coordinated and AI-driven defense pipeline is feasible. The contributions are fourfold:

• First, the consolidation of Suricata and Wazuh data into a standardized feature space, enabling richer anomaly contexts.

• Second, the design of an adversarially hardened Autoencoder that achieves resilience against evasion attempts.

• Third, the integration of SHAP to ensure transparent and interpretable anomaly explanations.

• Finally, and the deployment of a DQN-based agent that learns an adaptive response policy capable of prioritizing decisive mitigation without inflating false positives.

Together, these elements highlight the potential of HI-XDR as a next-generation XDR research prototype.

Nevertheless, the current evaluation also has several limitations. The framework has so far been tested in a controlled simulated environment, which while suitable for proof-of-concept validation, does not fully capture the variability and noise of production networks. As such, benchmarking against widely adopted public datasets such as CIC-IDS 2024 or UNSW-NB15 will be essential to establish external validity and reproducibility. In addition, while the proposed response mechanism demonstrates feasibility in simulation, real-time deployment within a live SOC requires further exploration of scalability, latency trade-offs, and integration with existing orchestration pipelines. From a security assurance perspective, future research should not only expand adversarial testing beyond PGD but also explore emerging confidentiality and privacy-preserving dimensions. This includes incorporating post-quantum cryptography (PQC)-ready mechanisms, secure data sharing protocols, and potentially lightweight quantum-resistant encryption to ensure long-term resilience in adversarial environments. Beyond algorithmic enhancements, human factors must also be considered, visual interfaces and explainable dashboards could support analyst oversight and foster trust when deploying automated responses.

In summary, HI-XDR demonstrates a promising path toward adaptive and transparent cyber defense, yet its broader validation and integration with real world infrastructures remain important milestones. Addressing these open challenges will further strengthen the relevance of HI-XDR and prepare it for deployment in both contemporary and future threat landscapes. Ultimately, this work aspires to serve as a bridge toward PQC ready, human and AI collaborative SOC ecosystems, where automated intelligence and human expertise converge to deliver resilient, trustworthy, and future-proof cybersecurity operations.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our deepest gratitude to COCONUT Computer Club for their support and inspiring environment for this research.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2025, 20th Edition [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2025.pdf. [Google Scholar]

2. Chinnasamy R, Subramanian M. Detection of malicious activities by smart signature-based IDS. In: Artificial intelligence for intrusion detection systems. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2023. p. 63–78. doi:10.1201/9781003346340-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Venkatraman S. Deep learning for cyber security applications: a comprehensive survey [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://d197for5662m48.cloudfront.net/documents/publicationstatus/162402/preprint_pdf/1db580dedba693379c64ee6ebfbf4792.pdf. [Google Scholar]

4. Chauhan GS, Mekala R. AI-driven intrusion detection systems: enhancing cybersecurity with machine learning algorithms. Int J Multidiscip Curr Res. 2019;7:131–9. [Google Scholar]

5. Zolanvari M, Teixeira MA, Gupta L, Khan KM, Jain R. Machine learning-based network vulnerability analysis of industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(4):6822–34. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2912022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gaspar D, Silva P, Silva C. Explainable AI for intrusion detection systems: lime and SHAP applicability on multi-layer perceptron. IEEE Access. 2024;12:30164–75. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3368377; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nguyen TT, Reddi VJ. Deep reinforcement learning for cyber security. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(8):3779–95. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3121870; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kheddar H. Transformers and large language models for efficient intrusion detection systems: a comprehensive survey. Inf Fusion. 2025;124(1):103347. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pan Z, Mishra P. Malware detection using explainable AI. In: Explainable AI for cybersecurity. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 55–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-46479-9_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Oh S. A method for explaining individual predictions in neural networks. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2025;11:e2802. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Nithya R. Reinforcement learning enhanced cybersecurity frameworks for autonomous threat response systems. In: Deep learning architectures for natural language understanding and computer vision applications in cybersecurity. Coimbatore, India: RADemics Research Institute; 2025. p. 288–322. doi:10.71443/9789349552319-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gupta P, Raïssi C, Dray G, Poncelet P, Brissaud J. SS-IDS: statistical signature based IDS. In: 2009 Fourth International Conference on Internet and Web Applications and Services; 2009 May 24–28; Venice/Mestre, Italy. IEEE; 2009. p. 407–12. doi:10.1109/ICIW.2009.67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Goswami MJ. Enhancing network security with AI-driven intrusion detection systems. Int J Open Publ Explor. 2024:29–35. [Google Scholar]

14. Prymachenko D, Goloborodko S, Sviatska N, Diachuk O, Mykhailo. EDR and XDR as the main endpoint security technologies. Cybersecur Educ Sci Tech. 2025:343. doi:10.28925/2663-4023.2025.28.808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Islam MR, Rafique R. Wazuh SIEM for cyber security and threat mitigation in apparel industries. Int J Eng Mater Manuf. 2024;9(4):136–44. doi:10.26776/ijemm.09.04.2024.02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guo J, Guo H, Zhang Z. Research on high performance intrusion prevention system based on Suricata. Highlights Sci Eng Technol. 2022;7:238–45. doi:10.54097/hset.v7i.1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nwafor E, Baskota U, Parwez MS, Blackstone J, Olufowobi H. Evaluating large language models for enhanced intrusion detection in Internet of Things networks. In: GLOBECOM 2024—2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2024 Dec 8–12; Cape Town, South Africa. IEEE; 2024. p. 3358–63. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM52923.2024.10901300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Klein T, Romano G. Optimizing cybersecurity incident response via adaptive reinforcement learning. J Adv Eng Technol. 2025;2(1):1–9. doi:10.62177/jaet.v2i1.212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Javeed D, Saeed MS, Ahmad I, Kumar P, Jolfaei A, Tahir M. An intelligent intrusion detection system for smart consumer electronics network. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2023;69(4):906–13. doi:10.1109/tce.2023.3277856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hazim LR, Jasim AA, Ata O, Ilyas M. Intrusion detection system (IDS) of multiclassification IoT by using pipelining and an efficient machine learning. In: 2023 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET); 2023 Oct 27–28; Istanbul, Turkiye. IEEE; 2023. p. 27–8. doi:10.1109/ICEET60227.2023.10525915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Torabi H, Mirtaheri SL, Greco S. Practical autoencoder based anomaly detection by using vector reconstruction error. Cybersecurity. 2023;6(1):1. doi:10.1186/s42400-022-00134-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Alghawazi M, Alghazzawi D, Alarifi S. Deep learning architecture for detecting SQL injection attacks based on RNN autoencoder model. Mathematics. 2023;11(15):3286. doi:10.3390/math11153286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Vázquez-Hernández M, Morales-Rosales LA, Algredo-Badillo I, Fernández-Gregorio SI, Rodríguez-Rangel H, Córdoba-Tlaxcalteco ML. A survey of adversarial attacks: an open issue for deep learning sentiment analysis models. Appl Sci. 2024;14(11):4614. doi:10.3390/app14114614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Korniszuk K, Sawicki B. Autoencoder-based anomaly detection in network traffic. In: 2024 25th International Conference on Computational Problems of Electrical Engineering (CPEE); 2024 Sep 10–13; Stronie Śląskie, Poland. IEEE; 2024. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/CPEE64152.2024.10720411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu L, Chen H, Yin C, Fu Y. Multi-stage dual-perturbation attack targeting transductive SVMs and the corresponding adversarial training defense mechanism. Electronics. 2024;13(24):4984. doi:10.3390/electronics13244984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guliani R. Enhancing robustness of machine learning models against adversarial attacks [dissertation]. Portland, OR, USA: Portland State University; 2020. doi:10.15760/honors.1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bhuyan BP, Tomar R, Fore V. Knowledge representation to expound deep learning black box. In: Future connected technologies. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2023. p. 113–28. doi:10.1201/9781003287612-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Aydoğan F, Aytekin T. A quantitative evaluation of xai methods lime and shap across diverse domains and machine learning methods. SSRN. 2024. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5030355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Uysal I, Kose U. Analysis of network intrusion detection via explainable artificial intelligence: applications with SHAP and LIME. In: 2024 Cyber Awareness and Research Symposium (CARS); 2024 Oct 28–29; Grand Forks, ND, USA. IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CARS61786.2024.10778742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Garouani M, Ahmad A, Bouneffa M. Explaining meta-features importance in meta-learning through shapley values. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems; 2023 Apr 24–26; Prague, Czech Republic. SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications; 2023. p. 591–8. doi:10.5220/0011986600003467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hu Z, Chen P, Zhu M, Liu P. Reinforcement learning for adaptive cyber defense against zero-day attacks. In: Adversarial and uncertain reasoning for adaptive cyber defense. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 54–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-30719-6_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kheddar H, Dawoud DW, Awad AI, Himeur Y, Khan MK. Reinforcement-learning-based intrusion detection in communication networks: a review. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2025;27(4):2420–69. doi:10.1109/comst.2024.3484491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hermosilla P, Berríos S, Allende-Cid H. Explainable AI for forensic analysis: a comparative study of SHAP and LIME in intrusion detection models. Appl Sci. 2025;15(13):7329. doi:10.3390/app15137329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Salih AM, Raisi-Estabragh Z, Galazzo IB, Radeva P, Petersen SE, Lekadir K, et al. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. arXiv:2305.02012. 2023. [Google Scholar]

35. Mohale VZ, Obagbuwa IC. A systematic review on the integration of explainable artificial intelligence in intrusion detection systems to enhancing transparency and interpretability in cybersecurity. Front Artif Intell. 2025;8:1526221. doi:10.3389/frai.2025.1526221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools