Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Decentralized Identity Framework for Secure Federated Learning in Healthcare

Department of Computer Science, Edo State University Iyamho, Auchi, 312102, Edo State, Nigeria

* Corresponding Author: Samuel Acheme. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2026, 8, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2026.073923

Received 28 September 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 07 January 2026

Abstract

Federated learning (FL) enables collaborative model training across decentralized datasets, thus maintaining the privacy of training data. However, FL remains vulnerable to malicious actors, posing significant risks in privacy-sensitive domains like healthcare. Previous machine learning trust frameworks, while promising, often rely on resource-intensive blockchain ledgers, introducing computational overhead and metadata leakage risks. To address these limitations, this study presents a novel Decentralized Identity (DID) framework for mutual authentication that establishes verifiable trust among participants in FL without dependence on centralized authorities or high-cost blockchain ledgers. The proposed system leverages Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs) issued by a designated Regulator agent to create a lightweight, cryptographically secure identity management layer, ensuring that only trusted, authorized participants contribute to model aggregation. The framework is empirically evaluated against a severe model poisoning attack. Without the framework, the attack successfully compromised model reliability, reducing overall accuracy to 0.68 and malignant recall to 0.51. With the proposed DID-based framework, malicious clients were successfully excluded, and performance rebounded to near-baseline levels (accuracy = 0.95, malignant recall = 0.99). Also, this system achieves significantly improved integrity protection with minimal overhead: total trust overhead per FL round measured 75.5 ms, confirming its suitability for low-latency environments. Furthermore, this latency is approximately 39.7 times faster when compared to the consensus step alone of an optimized distributed ledger-based trust system, validating the framework as a scalable and highly efficient solution for next-generation FL security.Keywords

Federated Learning (FL) is a decentralized machine learning approach where multiple devices collaboratively train a shared model without exposing their raw data. Instead of transmitting personal datasets, only model parameters or updates are exchanged within FL systems [1]. This ensures that sensitive user data remains on local devices, thereby minimizing the likelihood of privacy violations [2,3]. Unlike conventional machine learning, which often relies on centralized data collection which increases privacy risks, FL mitigates this concern by keeping training data on individual devices [4].

Within an FL environment, clients train their data locally and only send model updates to the co-ordinating server [5]. The iterative process begins when a central server distributes an initial global model to participating clients [6–8]. Each client then performs local training with its private data and returns only the model updates rather than the raw data [9,10]. These updates are then aggregated by the server to improve the global model [8]. Finally, in the update and distribution stage, the optimized model is disseminated back to the clients, enabling further rounds of training [11].

1.1.1 Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning

Privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) encompasses techniques and frameworks aimed at building and deploying machine learning models while maintaining the confidentiality of sensitive data [12]. Its core objective is to integrate explicit privacy guarantees that protect training data during the learning process [13].

PPML methodologies allow effective model development while ensuring that individual data remains protected [14]. Several PPML techniques exist including:

• Federated Learning: Facilitates collaborative training by exchanging only model updates instead of raw data [15].

• Differential Privacy: Injects carefully designed noise into data or model outputs to prevent leakage of personal information [16].

• Homomorphic Encryption: A cryptographic method enabling computation directly on encrypted data without decryption, thus maintaining confidentiality while allowing analysis [17].

• Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC): Permits multiple entities to jointly compute a function while keeping each party’s input private [18].

1.1.2 Decentralized Identity Management

Decentralized Identity Management (DIDM) is the process of managing digital identities based on the principle of Self-sovereign Identity (SSI). It involves the issuance, storage, and verification of verifiable credentials without relying on a central authority [19,20]. DIDM gives individuals greater control over their digital identity, allowing them to share only necessary information with specific entities [21].

SSI is a digital identity model that gives individuals control over their personal data and credentials, removing the need for centralized authorities [22]. This decentralized approach protects privacy and security while reducing the risk of identity theft [21].

Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) are globally unique identifiers designed for digital entities, such as people, organizations, or objects. Unlike traditional identifiers that are issued and controlled by a central authority [21]. DIDs are self-owned and cryptographically verifiable. They are typically linked to a cryptographic key pair and registered on a decentralized network or distributed ledger, which provides a tamper-proof and trustless mechanism for their resolution [5]. This structure enables secure, peer-to-peer authentication and identity verification without relying on intermediaries, thereby giving individuals and organizations complete control over their digital identity and data [20].

Verifiable Credentials (VCs) are digital, tamper-proof representations of real-world documents such as a driver’s license or academic degree [23]. Issued by trusted organizations, they can be securely shared and verified by others. Verifiable credentials are provided by trusted issuers, stored by individuals in their digital wallet, and presented as a claim to a verifier, who then confirms their validity [19].

1.2 Problem Statement and Motivation

FL has emerged as a powerful paradigm for distributed machine learning, enabling multiple clients to collaboratively train models without directly sharing raw data [1]. While this approach addresses critical privacy concerns associated with centralized data collection, it introduces new vulnerabilities related to trust and authentication among participating entities [2]. In FL ecosystems, multiple clients and servers often from heterogeneous and potentially adversarial environments interact and exchange model updates [9]. Without robust mechanisms for verifying the legitimacy of these entities, the entire system becomes susceptible to poisoning attacks, data leakage, model manipulation, and unauthorized participation [5].

Existing PPML techniques, such as differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation, focus primarily on protecting data during training and transmission [16–18,24]. However, they largely overlook the fundamental issue of mutual authentication, ensuring that both the server and the clients can verify each other’s trustworthiness before engaging in collaborative learning. Weak or absent authentication mechanisms erode trust among participants, create opportunities for malicious actors to infiltrate the system, and ultimately compromise both the security and reliability of the global model [25].

Blockchain has been employed as a means of managing trust in FL. While its distributed ledger provides accountability, it introduces significant limitations [26]. The transparency of blockchain transactions can inadvertently leak metadata, exposing participation patterns or organizational relationships [27]. Furthermore, maintaining consensus across nodes increases computational and communication overhead, hindering scalability and reducing efficiency in large-scale FL deployments [28].

To address these limitations, this study adopts an off-chain self-sovereign identity framework powered by decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials. Unlike blockchain-based trust management, this off-chain SSI solution enables lightweight, peer-to-peer authentication, minimizes metadata exposure, and enhances trust without imposing excessive overhead.

By leveraging DID-based identity management and verifiable credentials, this research aims to design and implement an improved mutual authentication mechanism tailored for federated learning environments. This approach will strengthen trust, preserve privacy, and protect against adversarial threats, thereby advancing the security and reliability of FL in real-world applications.

This research introduces an off-chain DID-based mutual authentication framework to address the critical challenge of trust and adversarial resilience in federated learning. Unlike centralized or blockchain-based trust management systems, the proposed solution leverages DIDs and VCs to establish lightweight, off-chain, and verifiable trust among participants. The key contributions of this study are as follows:

• Novel DID-Based Authentication Framework: We designed a novel trust architecture for FL that enables mutual authentication between servers and clients using cryptographically signed credentials issued by the Regulator agent.

• Lightweight, Off-Chain Identity Management: We eliminated reliance on resource-intensive blockchain infrastructures by implementing an off-chain credentialing system that minimizes computational and communication overhead, ensuring scalability for real-world FL deployments.

• Mitigation of Model Poisoning Attacks: We demonstrated through experimental evaluation that the proposed framework effectively prevents malicious clients from corrupting the global model. The system identified and rejected falsified updates, preserving model accuracy and reliability.

• Empirical Validation in Healthcare FL: The framework was validated in a healthcare FL setting using simulations with both honest and malicious hospitals. The evaluation tested its ability to preserve model accuracy and robustness under adversarial conditions compared to a baseline FL system. This demonstrated the role of decentralized identity in enabling secure collaboration and contributed new insights on privacy-preserving trust management in healthcare.

• Scalable and Practical Trust Management: We provided a secure and verifiable alternative to centralized and blockchain-based authentication systems. The framework enhances trust, preserves privacy, and can be seamlessly integrated into FL environments with minimal infrastructure changes.

The proposed DID-based authentication framework advances the state of the art in federated learning security by offering a scalable and efficient solution to the long-standing challenge of mutual trust in decentralized machine learning.

Privacy-preserving machine learning has become an increasingly important research domain, particularly as machine learning applications expand into sensitive areas like healthcare, finance, and critical infrastructures where data privacy is paramount [29]. Numerous approaches including differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation have been explored to protect training data in federated learning [29]. While effective in safeguarding privacy, these methods face challenges such as reduced model accuracy and high computational demands [30]. Trust management further remains essential in privacy-sensitive settings, where blockchain-based frameworks have been proposed to ensure transparency and integrity [25]. However, blockchain-based solutions introduce scalability concerns and risks of metadata leakage [30]. This section reviews studies addressing these challenges and highlights advances in privacy-preserving federated learning.

Liu et al. [31] proposed CAFL, a contribution-aware FL framework designed for smart healthcare applications. CAFL tackles challenges of data quality, variability, and heterogeneous data distribution by fairly evaluating each participant’s contribution to model performance without revealing private data. It also improves training by distributing the best intermediate models to participants, enhancing overall accuracy. However, trust guarantees were not considered to ensure that only trusted entities participate in the FL process.

Silva et al. [32] proposed Fed-biomed, an open-source framework for FL in healthcare. Their study addressed the challenges in healthcare data sharing through FL, providing a flexible framework for deploying decentralized models across multiple sites. However, their solution lacks comprehensive trust management and privacy guarantees tailored to diverse healthcare settings.

Yuan et al. [33] introduced Fedcomm, a privacy-efficient and enhanced protocol for FL. Their work addresses privacy, authentication, and malicious participant detection in vehicular FL through pseudonymous identities and efficient protocols, focusing primarily on communication efficiency and anonymity within a highly dynamic network. However, the study lacked a comprehensive trust management framework to ensure only verified, trustworthy entities participate and did not address local data privacy at the participant level.

Shayan et al. [34] proposed Biscotti, a decentralized peer-to-peer FL framework leveraging blockchain and cryptographic primitives to eliminate reliance on centralized coordinators. While Biscotti enhances privacy, scales under adversarial conditions, and mitigates poisoning attacks, it introduces blockchain overhead and does not fully resolve efficiency challenges in large-scale real-time learning.

Manoj et al. [35] in their study on AgriFLChain, proposed a blockchain-based FL framework for smart agriculture, focusing on crop yield prediction. While centralized models (ResNet-16, ResNet-28, CNN-DNN, CNN-LSTM) showed strong predictive power, they highlighted risks of single-point failure and lack of trust. Although AgriFLChain maintained efficiency and scalability comparable to centralized learning, it primarily emphasized on-chain trust guarantees rather than lightweight, off-chain mechanisms.

Mou et al. [36] in their work on distributed machine learning, proposed a system architecture integrating FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to improve collaboration and data management in federated learning. They introduced tailored metadata schemes and a decentralized authentication mechanism using self-sovereign identity with policy-based access control. Their evaluation through a fairness assessment and federated use case demonstrated improved data sharing and security. However, while the framework ensures responsible data governance and interoperability, it emphasizes structural and policy mechanisms rather than lightweight, model-level privacy protections.

Zeydan et al. [37], in their study on identity management for vehicular FL, proposed an alternative to blockchain-based SSI. Their framework integrated SSI with FL to ensure confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity of vehicle users’ identities and data exchanges with the aggregation server. Experimental results showed that credential operations were generally efficient, though presentation, offer, connection establishment, and revocation times slightly increased with request volume, suggesting minor performance degradation at scale. However, their approach did not fully address the scalability and adaptability challenges of SSI in broader FL contexts.

Zeydan et al. [38] proposed a blockchain-based SSI approach for managing vehicle user identities and securing data exchanges with the aggregation server during FL iterations. The integration strengthens authenticity, integrity, and trust in the FL process while maintaining decentralized control. Experimental results show that while FL execution time increases with more clients and training rounds, the blockchain-supported SSI system achieves significantly faster credential operations. However, the reliance on blockchain introduces scalability and latency concerns.

Papadopoulos et al. [25] proposed a decentralized trust framework for FL using DIDs, leveraging the Hyperledger Aries/Indy/Ursa ecosystem. Their prototype demonstrated how verifiable credentials can authenticate entities before participating in privacy-sensitive FL workflows, such as training on mental health data. While their work effectively addresses trust and authentication through SSI, it relies heavily on blockchain-based infrastructure, which can introduce scalability and latency concerns in high-volume FL environments.

Khan et al. [39] addressed the security and resource limitations hindering the wide integration of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) by proposing Fed-Inforce-Fusion, a novel privacy-preserving Intrusion Detection System (IDS) based on FL. Specifically designed for resource-limited Smart Healthcare Systems (SHS), the model first employs a reinforcement learning technique to accurately learn the complex, latent relationships within sensitive medical data. The system then uses FL to enable distributed SHS nodes to collaboratively train a comprehensive IDS without centralizing proprietary patient information, thereby enhancing privacy and security. While effective at detecting attacks on the model’s integrity after they happen, this approach does not provide a proactive barrier against unauthorized or malicious clients.

Shrestha et al. [40] introduced a privacy-preserving framework to identify anomalies in smart electric grid data collected from substations, mitigating the risks of data misuse and privacy leakage inherent in central data storage. The system couples an LSTM-Autoencoder model for anomaly detection validated using the Mean Squared Deviation (MSD) and Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) approaches with FL to enable cooperative, privacy-preserving model training among energy providers. Furthermore, the framework integrates homomorphic encryption (Paillier algorithm) to enhance data security. However, their work focuses heavily on mathematical privacy protection for the data and model parameters, which can be computationally costly.

Jithish et al. [41] addressed the challenges of detecting anomalous behaviors in smart grids such as power thefts or cyberattacks by proposing an FL-based anomaly detection scheme that resolves the issue of data security and user privacy raised by traditional centralized machine learning. By enabling local model training on resource-constrained smart meters, the approach eliminates the need for sharing sensitive user data with a central server, while also alleviating computational burdens and latency issues. Furthermore, the model parameter updates are secured using Secure Socket Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Security (TLS). However, securing parameter updates using SSL/TLS ensures confidentiality during transit, but it does not verify the trustworthiness or of the client (the source) sending the updates.

Mothukuri et al. [42] addressed the severe privacy leakage and data centralization challenges inherent in applying classic machine learning to distributed IoT networks, where personally identifiable information is constantly generated at the edge. To proactively recognize intrusion, they proposed an FL-based anomaly detection approach that utilizes decentralized on-device data by training Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) models locally. This method secures user privacy by only sharing the learned model weights with the central server, where an ensembler part aggregates updates from multiple sources to optimize the global model’s accuracy. This solution attempts to optimize accuracy and perhaps implicitly mitigate poor updates through clever aggregation (the ensembler). However, it relies on the hope that the ensembler can filter out large-scale, coordinated model poisoning attacks.

Sahu et al. [43] addressed the limitations of traditional anomaly detection in distributed threat scenarios. They proposed a novel Federated Long Short-Term Memory (Fed-LSTM) model tailored for analyzing cyber security time-series data. The model utilizes FL to permit collaborative model training across decentralized data sources without centralizing raw data, thereby preserving privacy, while leveraging LSTMs for their effectiveness in identifying temporal correlations. However, no measure was put in place to protect the high-performing Fed-LSTM from rogue participants.

Jeyasheela Rakkini et al. [44] addressed the need for improved cybersecurity in decentralized environments, they proposed a novel Transformer-Based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) integrated within a Deep Federated Learning (DFL) framework. The model leverages the self-attention mechanisms of transformers to capture complex temporal and spatial dependencies in network traffic for accurate attack detection, while the DFL framework ensures strong privacy preservation by keeping sensitive data decentralized. However, formal trust guarantees were not put in place to guarantee only legitimate participation.

Yang et al. [45], in their study, used highly compressed gradients for data reconstruction attacks. By acknowledging that FL gradients can still be reconstructed to leak private data, they proposed the Highly Compressed Gradient Leakage Attack (HCGLA). HCGLA is able to carry out data reconstruction with three key techniques: redesigning the optimization objective for compression scenarios, introducing the Init-Generation method to compensate for information loss in dummy data initialization, and employing a denoising model for quality enhancement. Their study highlights a major privacy vulnerability in FL (gradient reconstruction), which demonstrates that solely focusing on securing the aggregation process is insufficient.

Khan et al. [46] presented a method for securing sensitive data at rest or in transit through quantum image encryption. The scheme features a two-phase chaotic confusion-diffusion architecture that performs simultaneous qubit and pixel-level encryption. The authors demonstrate strong resilience against statistical and differential attacks as well as resistance to occlusion. Their study highlights the necessary advancements in cryptographic privacy protection for massive image datasets, particularly in emerging quantum computing environments. However, its focus is strictly on securing the raw data contents via encryption. It does not address the integrity risks associated with decentralized training, such as ensuring the encrypted data is processed by an authorized node, nor does it address privacy risks (metadata leakage) that arise when integrating trust management into a distributed machine learning architecture like FL.

Umair et al. [47] addressed the challenge of deploying high-performing deep learning models for cyber-attack detection on resource-constrained consumer devices. The authors utilize knowledge distillation to train a significantly smaller student model from a larger teacher model, achieving impressive reductions in model size and inference time with minimal loss in accuracy. Their study is critical to improving the computational efficiency and scalability of security solutions at the edge, making on-device intelligence feasible. While their work focuses on optimizing the model payload for lightweight operation, it does not address the integrity of the training process itself. The optimized student model could still be targeted or compromised during a decentralized training phase by an unauthorized client.

Mai et al. [48] presented a comprehensive survey of cybersecurity challenges in shipboard microgrids (SHMGs), focusing on vulnerabilities in communication networks that connect sustainable energy resources, energy storage systems, and loads. The review identifies key attack vectors, including denial-of-service, false data injection, covert, and replay attacks, and surveys detection and mitigation mechanisms ranging from observer-based methods (Kalman filter, Luenberger observer) to machine learning algorithms and control-based strategies (active disturbance rejection control, model predictive control). The study emphasizes safeguarding the stability and operational integrity of maritime power systems. While the paper provides valuable insights into SHMG-specific cybersecurity threats and countermeasures, its scope is limited to the detection and mitigation of attacks within the energy system context. It does not address trust establishment, mutual authentication, or credential-based verification mechanisms that are central to federated learning frameworks in privacy-sensitive domains such as healthcare.

2.1 Limitations in Existing Federated Trust Mechanisms

Existing trust mechanisms often introduce significant operational latency. For instance, highly optimized Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) protocols, as observed in Ren et al. [49], and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) systems that integrate block mining and P2P consensus such as Nguyen et al. [50], report a significant consensus latency per aggregation round. This reliance on resource-intensive consensus creates a major overhead gap, as this delay is prohibitive for high-frequency FL training that requires mutual authentication at the start of every round. Our work directly addresses this by departing from the on-chain verification model, separating the high-latency consensus layer (used only for auditable record-keeping) from our proposed low-latency runtime identity layer.

While some studies successfully target communication overhead, they fail to address the latency of the security check itself. Liu et al. [51], for example, proposed the efficient Federated Stochastic Block Coordinate Descent (FedBCD) approach, which mitigates communication overhead by reducing the frequency of gradient updates. While this is important for bandwidth efficiency, it does not minimize the clock latency of the security and identity checks that must occur when communication happens. Our work is architecturally orthogonal: we specifically focus on minimizing the clock latency of the security layer, ensuring that mutual authentication is nearly instantaneous, regardless of how frequently the models are exchanged.

Other security solutions introduce severe computational barriers. Lee et al. [52] proposed a Verifiable Decentralized FL (VDFL) system that extends security via computationally intensive Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP) and blockchain anchoring. This VDFL approach focuses on complex computational integrity tasks, but it does not prioritize a lightweight, sub-second mutual authentication protocol prior to its intensive workflow. Our work is structurally distinct: we separate these concerns, utilizing simple credential validation to achieve speed, ensuring the foundational act of secure communication is instant and non-blocking.

While the security strength of DIDs and VCs is established in human-centric applications like Single Sign-On as observed in Hauck [53], these are inherently low-frequency. This creates a scope and specificity gap, as DIDs/VCs are not typically applied to high-throughput, machine-to-machine (M2M) mutual authentication. Our work addresses this by successfully extending the robust DID/VC framework to meet the high-speed demands of automated FL, making the framework applicable to continuous M2M collaboration.

An important advantage of our off-chain design is the direct mitigation of the metadata leakage risk inherent to DLT solutions; Since ledger transactions including identity proofs, participation logs, and timestamps are publicly visible and traceable, malicious actors can easily deduce sensitive operational details like participation frequency, device type, and interaction patterns from the immutable public record. Our framework deliberately utilizes a stateless, off-chain verifiable credential validation mechanism. This choice completely eliminates the need to anchor authentication events to a public, traceable ledger, ensuring that the entire mutual authentication process remains private and non-traceable, thereby addressing the fundamental security vulnerability associated with DLT metadata leakage.

Motivated by these gaps, we present a novel DID/VC framework that strongly guarantees integrity and authentication while providing the low-latency performance and enhanced privacy required for scalable, real-time federated learning deployments.

2.2 Analysis of Existing System and this Paper’s Contribution

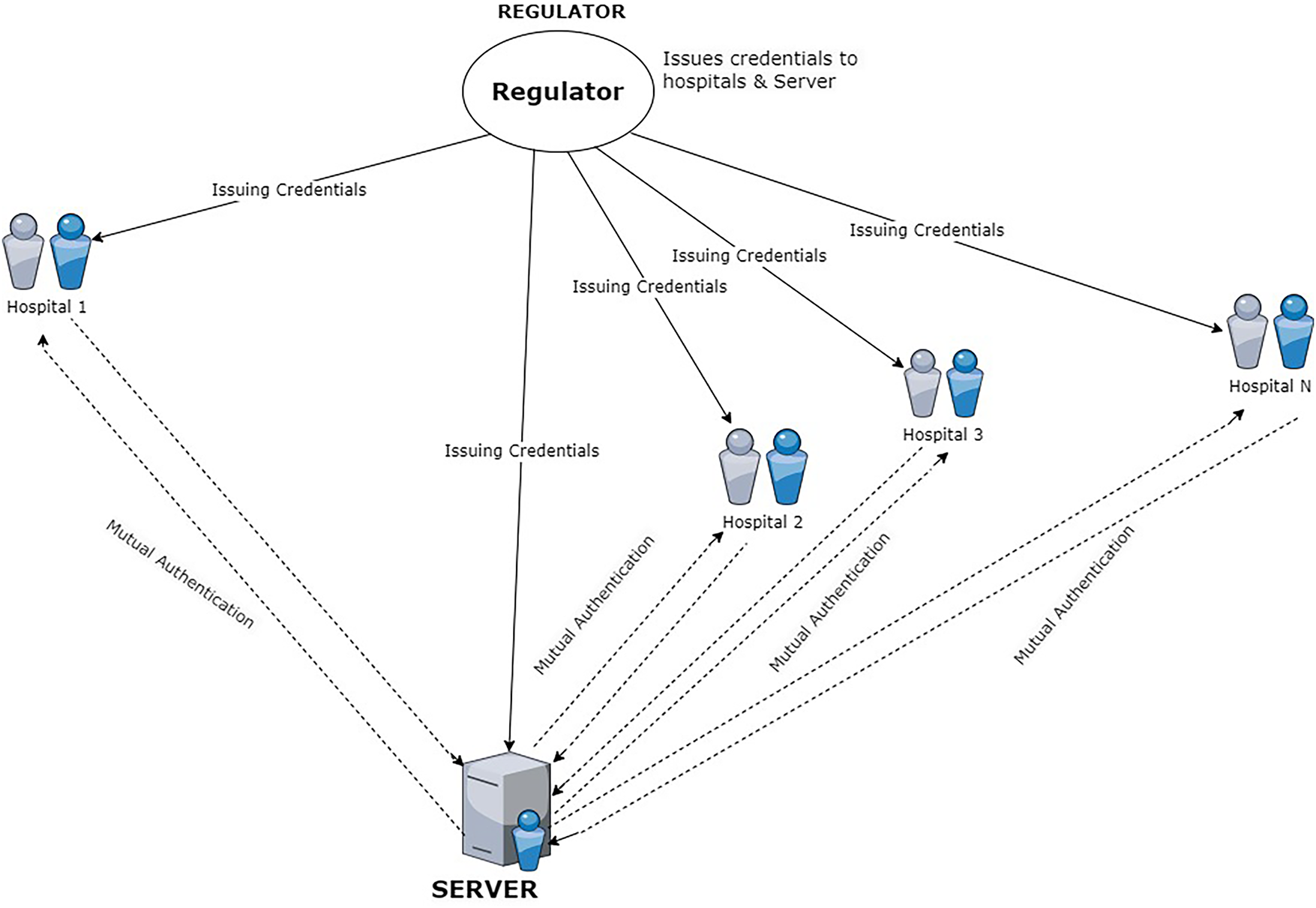

The existing system considered in this study is the Machine Learning Trust Framework of Papadopoulos et al. [25]. Fig. 1 is a diagrammatic representation of the machine learning trust Framework.

Figure 1: Machine learning trust framework [25]

Papadopoulos et al. [25] proposed an FL framework that integrates decentralized identity management using the Hyperledger ecosystem to enhance trust and security within collaborative machine learning environments. The system ensures that all participating entities are authenticated and that secure communication channels are established prior to engagement in the FL workflow. Their architecture incorporates a regulatory authority, a hospital trust, a researcher, and multiple hospital clients, with each participant required to obtain a verifiable credential to prove legitimacy. A mutual authentication process is then performed to guarantee that only authorized entities can participate. Once authenticated, a vanilla FL process where hospitals and the researcher exchange model updates ensuring data confidentiality in transit.

The Machine Learning Trust Framework proposed by [25] is composed of four agents namely:

• Regulatory Authority: Responsible for issuing verifiable credentials to validate the digital identities of participants.

• Researcher: Responsible for global model distribution, and aggregation of the federated model.

• Hospitals: Serve as FL clients that receive the global model, train it locally, and return updates following successful authentication

• Agents & Controllers: Implemented in separate Docker containers to simulate real-world deployment scenarios with isolated operational environments.

The workflow of communication and training proceeds as follows: (i) both hospitals and the researcher first obtain VCs from the regulatory authority (ii) the researcher distributes the initial machine learning model to authenticated hospitals; (iii) hospitals locally train the model on their private data and return the updates; and (iv) the researcher validates the aggregated model against a trusted local dataset.

While the framework demonstrates an important advancement by embedding decentralized identity management into federated learning, it still faces notable limitations. Specifically, its reliance on blockchain infrastructure (e.g., Hyperledger Indy) introduces the risk of metadata leakage, scalability concerns, and infrastructure overhead, which may hinder seamless adoption in large-scale, real-world healthcare applications.

Our solution overcomes this limitation by moving mutual authentication off-chain, reducing blockchain overhead and the possibility of metadata leakage while keeping strong trust guarantees. Verifiable credentials are exchanged directly between participants, ensuring privacy and efficiency. Additionally, a credential revocation endpoint allows regulators to invalidate compromised or outdated credentials, ensuring only trusted entities participate in federated learning.

This section outlines the methodology adopted to design an off-chain decentralized identity management solution leveraging DIDs and VCs, enabling efficient mutual authentication within the federated learning network.

3.1 Research Design and Approach

This study applies a Design Science Research (DSR) methodology to develop, implement, and evaluate a novel off-chain decentralized identity management framework for FL in healthcare. DSR is particularly appropriate here because it emphasizes both the creation of practical solutions and their rigorous evaluation [54]. The research design unfolds across three main phases: design, implementation, and evaluation.

To address the shortcomings of the existing system, this system design integrates (i) W3C-compliant decentralized identity standards (DIDs and VCs) for trust and authentication, (ii) an off-chain approach to identity management, avoiding blockchain-related overhead and privacy concerns, and (iii) a FastAPI-based implementation, chosen for its speed, asynchronous capabilities, and easy integration with Python machine learning libraries. The three entities, Regulator, Server, and Hospitals, were designed to be modular, independently deployable, and to communicate over secure HTTP interfaces.

The framework was implemented directly from the design blueprint with the following roles:

• Regulator: Issues decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials, serving as the trusted credential authority.

• Server: Coordinates FL by aggregating hospital updates and validating credentials before interaction.

• Hospitals: Train local models on private data and engage in mutual credential verification before contributing.

• Communication Layer: Built with FastAPI endpoints over HTTP, where identity verification relies on cryptographically verifiable credentials rather than blockchain infrastructure.

The system was developed entirely with Python, integrating specialized libraries for FL and credential management.

The framework will be tested through simulations using benchmark healthcare datasets. Evaluation focused on trust assurance, determining the system’s ability to exclude uncredentialed or unauthorized participants.

3.2 Architecture of Proposed System

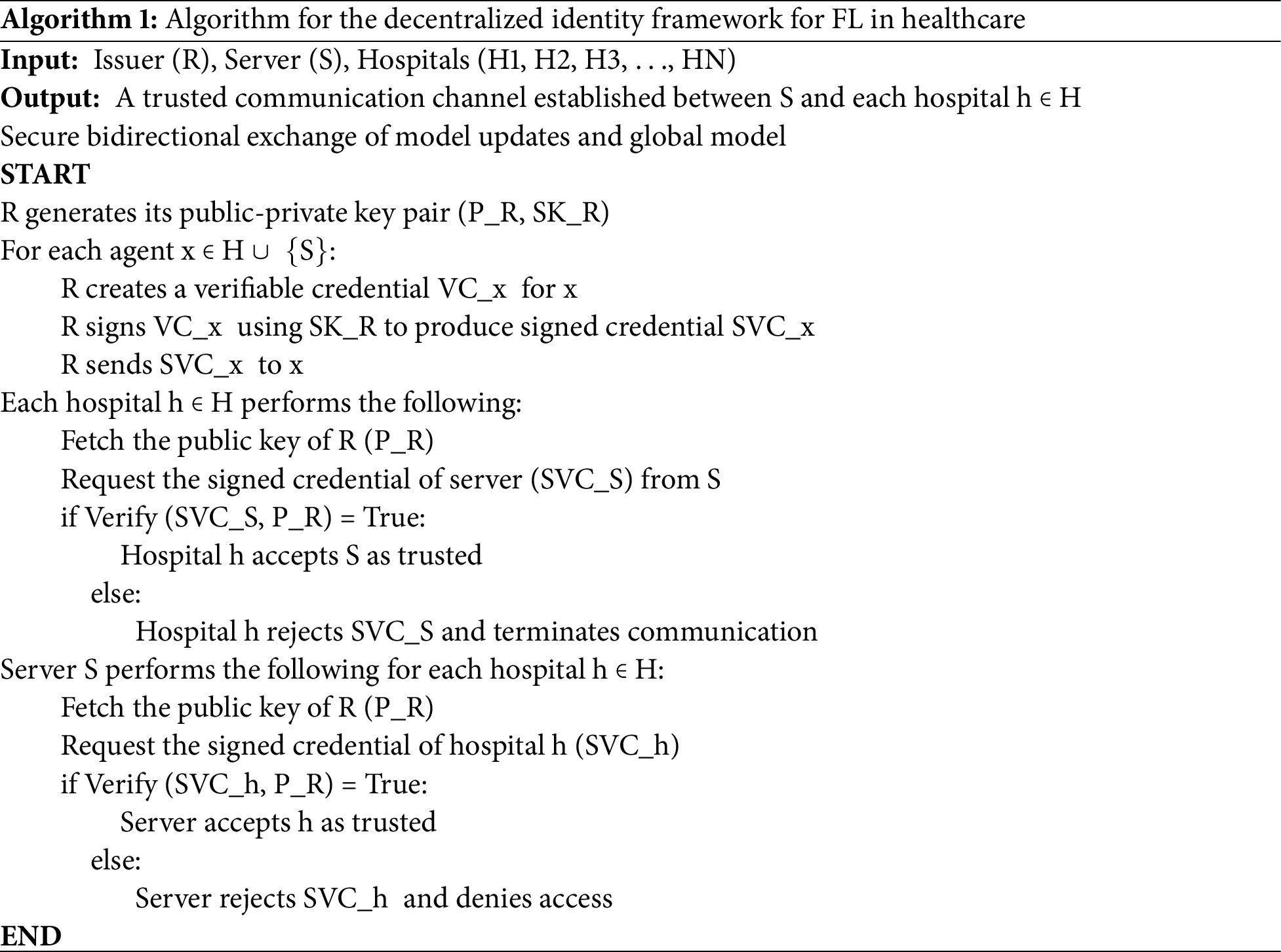

Our proposed framework, shown in Fig. 2, creates a secure communication environment for FL. Its purpose is to guarantee that private model updates are shared exclusively among verified, trusted participants.

Figure 2: Architecture of the proposed framework

The system’s design focused on authenticated and authorized participation for all involved entities: hospitals (the data holders), the server (the aggregator), and the regulatory authority (the regulator). Before any data or model exchange can begin, each participant must present a verifiable credential issued by the regulator. This step ensures that only approved agents handle sensitive patient data during collaborative model training.

To achieve this, the system uses a self-sovereign identity approach, allowing each participant to independently manage their own identity. Unlike conventional identity systems that rely on centralized authorities, our method utilizes off-chain decentralized identifiers and W3C verifiable credentials. These credentials are both digitally signed and cryptographically verifiable, enabling secure mutual authentication without the need for public blockchain registries or external resolvers.

The entire architecture is built on independent FastAPI applications for each entity: the regulator, hospitals, and the server with all communication happening over HTTP. During an FL session, the regulator first issues verifiable credentials to the server and all participating hospitals, confirming their identity and role. The server then performs a mutual authentication check with each hospital before any communication takes place. Only those with valid, verifiable credentials are permitted to join the training process.

This design ensures that unauthorized entities are completely excluded, and all model updates are exchanged within a trusted, authenticated network. Ultimately, this protects both data privacy and model integrity in healthcare-focused FL systems.

3.3 Data Collection and Pre-Processing

The dataset used in this study is the Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) dataset, originally provided by the UCI Machine Learning Repository. This dataset contains 569 samples with 30 numerical features that describe characteristics of cell nuclei computed from digitized images of fine needle aspirates (FNA) of breast masses. Each instance is labeled as either malignant (cancerous) or benign (non-cancerous). The dataset includes 212 malignant and 357 benign cases, making it a well-established benchmark for evaluating classification models in medical diagnosis tasks.

To get the data ready for a privacy-preserving FL environment, we used a thorough preprocessing pipeline. This approach ensures the data’s integrity, usefulness, and suitability for our secure and robust machine learning experiments, all while upholding strict privacy standards.

3.3.3 Data Preprocessing Steps

First, we cleaned the data by identifying and removing outliers. Using the Z-score method, we calculated the distance of each data point from its feature’s mean. Any data point with a Z-score greater than ±3 was considered an outlier and removed to ensure we were only training our model on statistically consistent observations.

Next, we performed feature standardization using the Standard Scaler. This step is important because it ensures that all features have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, preventing features with larger numerical ranges from overpowering those with smaller ones during training [24]. This is especially important for algorithms that rely on distance metrics or assume a normal distribution, like neural networks.

To minimize computational cost and reduce the risk of overfitting, we applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This technique is a linear transformation that identifies the directions, or principal components, that capture the most variance in the dataset [55]. We selected enough components to retain 95% of the cumulative variance. This step not only makes the model more efficient but also enhances privacy by obscuring the original feature details while preserving the data’s essential structure [55].

3.3.4 Data Partitioning and Preparation

After preprocessing, the dataset was split into training and testing sets using an 80:20 stratified sampling strategy because because this ratio provides sufficient data for training to capture patterns while reserving enough unseen data to reliably evaluate model performance and generalization.

To mimic a real-world FL setup, the training data was then partitioned among 10 different clients, with each one representing an independent data holder, like a hospital. Each partition was saved separately and loaded by a distinct agent during the training process. This guarantees that no raw data leaves its source, which is fundamental to a privacy-focused FL system.

3.3.5 Data Coding and Categorization

To ensure consistency across all participants, we used a structured approach for data coding:

• Label Encoding: We converted binary target variables into numerical values (e.g., 0 and 1).

• Federated Metadata: Each local dataset was tagged with metadata, including a unique client ID and role (e.g., hospital, server). This metadata was essential for simulating the credential verification and access control features of our system.

• Secure Organization: We organized each client’s dataset with unique identifiers, like hospitalA.csv, which allowed for automated loading and tracking during the training sessions.

This standardized framework ensures the entire process is both traceable and reproducible, allowing for efficient and secure federation across multiple healthcare agents.

Algorithm 1 shows the algorithm for the trust proposed decentralized identity framework for FL in healthcare.

As shown in Algorithm 1, the credential-based verification process between the Regulator (R), the Server (S), and the set of Hospitals (H = {h1, h2, h3, ..., hN}) is as follows. The process begins with the Regulator generating a cryptographic key pair consisting of a public key (P_R) and a private key (SK_R). Using the private key, the Regulator issues and cryptographically signs a verifiable credential for each participating agent. These signed credentials, denoted by SVCX, contain the agent’s identity and assigned role (e.g., hospital or server).

Each hospital (h) first obtains the Regulator’s public key (P_R). It then fetches the Server’s signed credential (SVC_S) and confirms its authenticity using a verification function. This function checks if the digital signature on the Server’s credential can be validated using the Regulator’s public key. If this check succeeds, the hospital trusts the Server. Similarly, the Server (S) performs the same verification for each hospital by retrieving its signed credential (SVC_h) and checking its authenticity.

Only when both parties have successfully verified each other’s credentials does the system proceed with the secure exchange of model updates.

3.5 Cryptographic and Identity Specification

The system is built entirely on the W3C Verifiable Credentials Data Model v1.1 and the DID Core Specification. The credentials issued are JSON-based and leverage a custom but W3C-compliant context.

3.5.2 Key Methods and Proof Format

All digital signatures are created using RSA cryptography with a key size of 2048 bits. The payload is hashed using SHA-256 and signed using PKCS1v15 padding. The resulting signature is encapsulated as a JSON Web Signature (JWS), stored in the VC’s proof object, and referenced by the JsonWebSignature2018 proof type.

3.5.3 Credential Freshness and Replay Protection

i. The system utilizes a session-specific nonce (Number Once) mechanism to guarantee the freshness of credentials and to prevent the replay of model updates and credentials.

ii. During mutual authentication, the Server issues a unique nonce to the Hospital, which the Hospital must include in the submit update request payload. The Server then verifies the nonce’s validity (using the Python secrets library for generation and server-side session tracking for single-use enforcement), thereby binding the credential presentation to a specific, non-repeatable communication session.

i. The Regulator maintains an internal revocation list indexed by the VC’s unique URN/UUID.

ii. A revocation request targets the /revoke/credential endpoint.

iii. During mutual authentication, the verification agent (Server or Hospital) performs an additional HTTP GET request to the Regulator’s /check-revocation endpoint to confirm the credential’s status is not revoked before accepting the model update.

Our system is designed to establish trust between the three actors: the regulator, the server, and the hospitals. It relies on a decentralized identity framework, using verifiable credentials to ensure that every participant is verified and trustworthy. Each of these entities: the regulator, the server, and the hospitals, is a separate FastAPI application.

The regulator acts as the central authority for managing trust in the FL process. Its main job is to issue verifiable credentials to authorized participants. This credential confirms their identity and role in the system. To allow others to verify these credentials, the regulator publicly shares its cryptographic key. The entire process of how the regulator issues these credentials is shown in Fig. 3 below.

Figure 3: Credential issuance process of regulator

The regulator’s role in the system is to act as the central authority for issuing credentials. To do this, it follows a strict, step-by-step process.

Phase 1: Handling a Credential Request

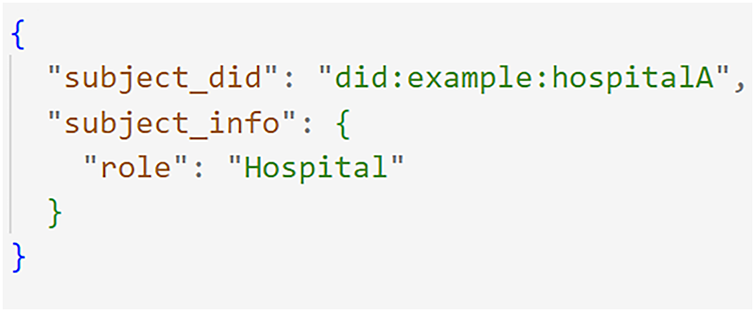

When an agent, a hospital or the server wants a credential, it sends a HTTP POST request to the regulator’s API at the /request-credential endpoint. The regulator then performs two critical checks. First, it makes sure the request is valid by checking it against a predefined format. The request must contain a unique DID for the agent and their specific role. This ensures the request is well-formed. As Fig. 4 shows, the request is a simple, structured message.

Figure 4: Credential request to regulator

After this, the regulator performs a strict authorization check. It verifies that the requesting agent is permitted to receive a credential. If the agent is authorized, the process continues; if not, the regulator immediately rejects the request with a “Forbidden” error (HTTP 403).

Phase 2: Generating the Credential

Once a request is approved, the regulator begins creating the credential. It first generates a unique ID for the credential using a Universally Unique Identifier (UUID), this UUID is generated using python’s uuid4() function. This is used to uniquely identify a credential and is embedded as a Uniform Resource Name (URN) in the id field of the credential (e.g., urn:uuid:xxxx). After this, the regulator adds a precise timestamp, ensuring the credential’s creation time is globally consistent. Finally, it builds the core of the credential, known as the credential subject, which contains the agent’s unique DID and assigned role.

Phase 3: Signing the Credential

The regulator prepares a cryptographic payload from the agent’s role information. Using its private key, the regulator then creates a digital signature for this payload using RSA cryptography.

To guarantee the signature is both secure and verifiable, the process follows these specifications:

• Padding: It uses PKCS1v15 padding, which adds a layer of structure to the data for secure signing.

• Hashing: It uses the SHA-256 hash function to create a unique fingerprint of the payload, ensuring the data’s integrity.

• Encoding: The final signature is encoded into a URL-safe string using Base64, making it easy to embed and transmit.

Finally, this digital signature is embedded into the proof section of the verifiable credential. This proof includes all the necessary details for verification: the type of signature used, the timestamp it was created, and a reference to the regulator’s public key. The actual signature itself is stored as a URL-safe Base64 string, known as the JSON web signature (JWS). This completes the cryptographic proof that the credential is authentic and was issued by the regulator.

Phase 4: Delivering the Credential

After the credential has been signed, it’s packaged into a JSON object and sent back to the requesting agent.

Supporting Trust Infrastructure

For the reliability of the system, the regulator maintains two key endpoints:

• Credential Revocation: The regulator can revoke a credential at any time using its unique UUID. This is essential for managing trust dynamically.

• Public Key Endpoint: The regulator exposes its public key so that other agents can retrieve it and verify the digital signatures on their credentials. This establishes the regulator as a root of trust for the entire system.

An example of a credential issued to a hospital agent is shown below in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Issued credential

In this credential;

• @context: This field simply confirms that the credential is W3C-compliant and uses a standard vocabulary, ensuring it can be easily understood by different systems.

• id: This serves as a unique identifier for the credential, much like a serial number.

• type: This field explicitly declares that the document is a Verifiable Credential, as defined by W3C specifications.

• issuer: This is the centralized identifier of the issuing entity, in this case, the regulator.

• issuanceDate: This provides the exact date and time the credential was created.

• credentialSubject: This defines the recipient of the credential by listing their DID and their assigned role (e.g., Hospital).

The credential also includes an important proof section which contains all the cryptographic details needed to verify its authenticity. Within this proof the following details are contained;

• type: Specifies the cryptographic algorithm used for signing, which in this case is RSA.

• created: Marks the exact timestamp when the digital signature was generated.

• proofPurpose: Explains the reason for the signature to assert that the information in the credential is true.

• verificationMethod: Points to the issuer’s public key, which is used by others to verify the signature.

• jws: This is the actual digital signature string itself. It’s generated using the issuer’s private key and ensures the integrity and authenticity of the entire credential.

4.2 Server and Hospitals (Credential Holders and Verifiers)

In our system, the server and hospitals are designed to be both credential holders and verifiers. This means they not only possess their own verifiable credential issued by the regulator, but they also have the responsibility of verifying each other’s credentials.

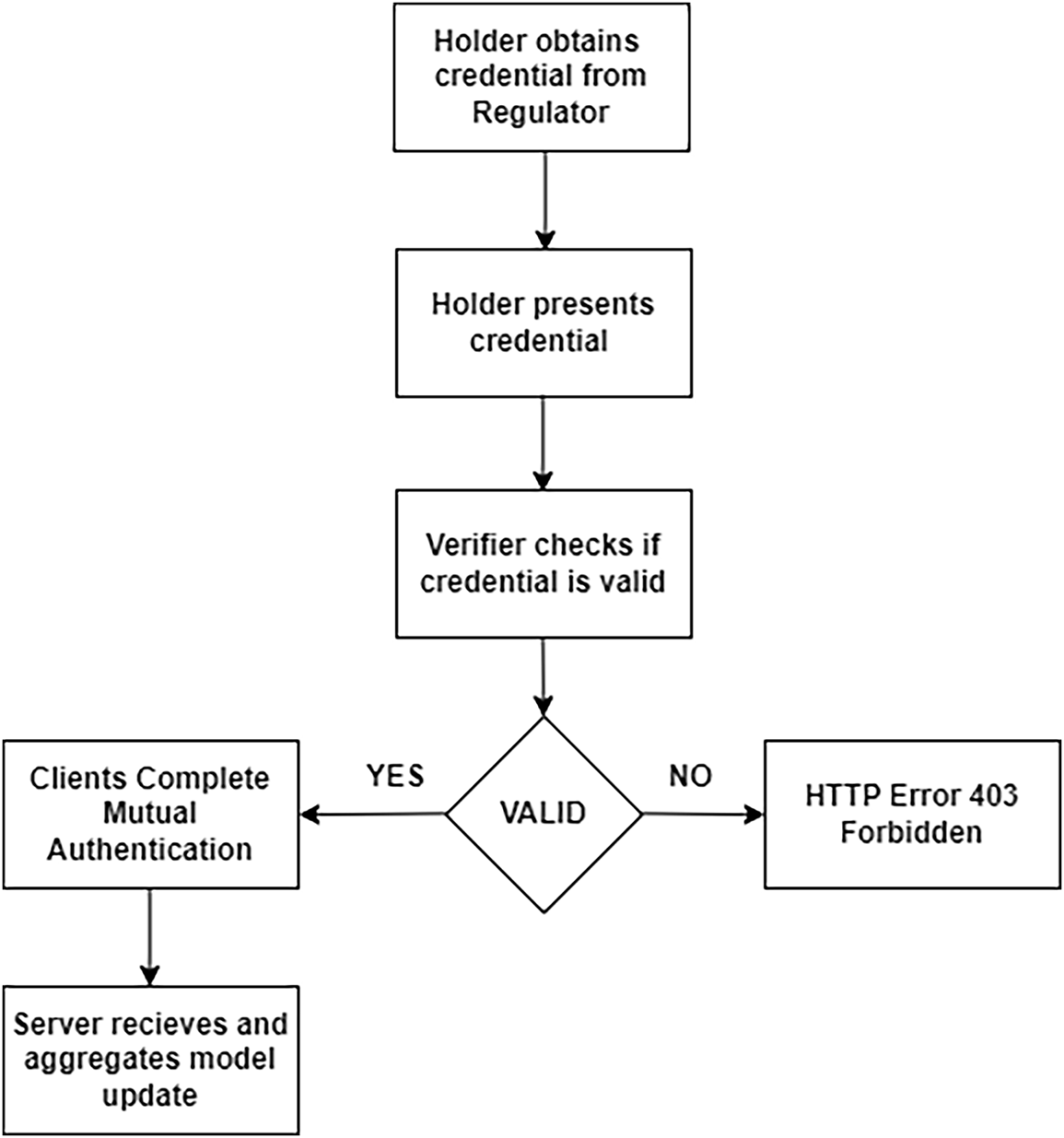

Before any data exchange begins, the server verifies the credential of each hospital to ensure they are authorized participants. At the same time, each hospital will verify the server’s credential before sending any model update. This process of two-way authentication is what ensures that all communication occurs exclusively within a trusted network of authorized agents. The entire credential request and verification process is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Credential request and verification process of server and hospitals

4.3 Credential Request and Verification Workflow of the Hospital

To ensure a secure training environment, each hospital follows a strict process to acquire its own credentials and then verify the server’s identity. This process has two main phases: acquiring a credential from the regulator and then verifying the server.

Phase 1: Credential Acquisition from Regulator

Firstly, each hospital needs to get the regulator’s public key. It does this by sending an HTTP POST request to the regulator’s /public_key endpoint on the regulator’s API. This key is needed for validating any credential issued by the regulator, and the hospital saves it securely for later use.

Next, the hospital makes a credential request to the regulator’s API by sending a HTTP POST request to the /request-credential endpoint on the Regulator’s API as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Credential request of hospital to regulator

This request prompts the regulator to issue a credential that confirms the hospital’s unique digital identity and its role in the system. The regulator digitally signs this new credential with its private key before sending it back.

Phase 2: Server Identity Verification before Sending Update

Before a hospital sends its model update, it must first verify the server’s identity. To do this, the hospital requests a credential from the server’s API. In this process, the Server issues a unique, single-use session_nonce for the current communication. Once it receives the server’s credential, the hospital uses the regulator’s public key (which it got in Phase 1) to perform a series of security checks on the server’s credential.

These checks include:

• Signature Validity: Is the digital signature valid?

• Integrity: Has the credential been tampered with?

• Issuer Trust: Was the credential issued by the trusted regulator?

• Subject Match: Does the credential correctly identify the server’s known digital identity?

• Revocation Status: Has the credential been revoked?

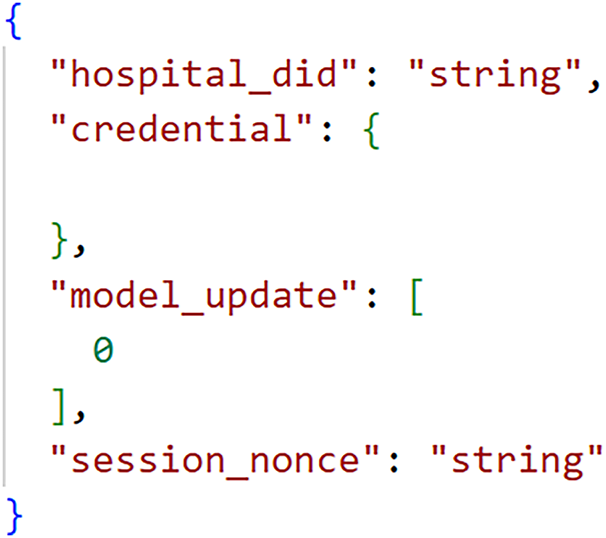

Only after the credential passes all these checks does the hospital send its model update to the server’s API sending an HTTP POST request to the server’s /submit-update endpoint. The request payload includes the required session_nonce to prevent replay attacks. The server then performs its own verification on the hospital’s credential, and if invalid, the model update is rejected, protecting the integrity of the FL model. The request payload is of the form shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Submit update request

4.4 Credential Request and Verification Workflow of the Server

To establish a trustworthy FL environment, the server follows a strict workflow. This process is divided into two main phases: acquiring its own credential and then verifying the credentials of participating hospitals.

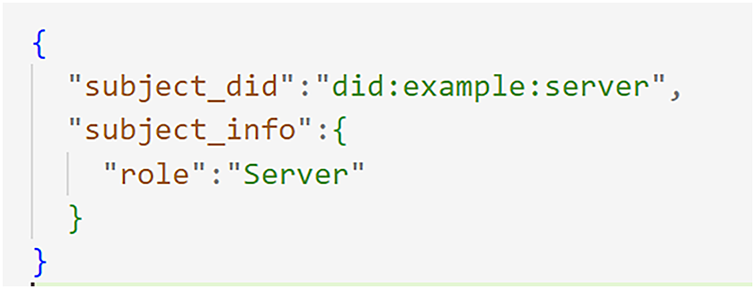

Phase 1: Acquiring a Credential from the Regulator

The server’s first step is to get the regulator’s public key by sending an HTTP GET request to the regulator’s /public-key endpoint on the regulator’s API. This key is essential for validating any credentials the regulator issues. After obtaining the key, the server sends its own credential request to the regulator. The server does this by sending an HTTP POST request to the /request-credential endpoint of the regulator. This request prompts the regulator to issue a verifiable credential that confirms the server’s identity and role. The credential is then digitally signed with the regulator’s private key before being sent back to the server. The credential request is a JSON payload of the structure shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Credential request of server to regulator

Phase 2: Hospital Identity Verification

Before the server accepts any model updates, it must verify the identity of the hospital sending the request. When a hospital requests the Server’s credential or initiates submission, the Server uses Python’s secrets module to generate and issue a unique session_nonce for the transaction. The server then uses the regulator’s public key to perform a series of cryptographic checks on the hospital’s credential. It verifies the digital signature, ensures the credential hasn’t been tampered with, and confirms that it was issued by the trusted regulator. The server also checks that the credential belongs to the correct hospital and that it hasn’t been revoked. In addition, the server verifies the submitted payload contains the correct, single-use session_nonce corresponding to the current transaction. Only after the credential passes all of these checks does the server accept the model update for aggregation otherwise the update is rejected, and the nonce is immediately invalidated.

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Partitioning

Following data collection, cleaning, and preprocessing, the dataset was randomized and divided into 80% for training and 20% for testing.

The training portion was partitioned using a Non-IID (Label Skew) scheme to better mirror the heterogeneity of real-world multi-institutional medical data.

To simulate the natural variability in disease prevalence across institutions, we employed the Dirichlet distribution (α = 0.5) to generate distinct label distributions for each client.

This approach ensures that each simulated hospital’s dataset contains a unique proportion of classes, reflecting realistic diagnostic diversity.

We used 15 clients (hospitals) for the experimental setup representing a mix of heterogeneous data volumes (Quantity Skew).

The server retained the test set for global model evaluation at the end of each communication round.

Phase 2: Local Model Training

Each hospital (client) independently trains a model on its private, non-IID dataset without sharing raw data.

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), a feedforward Artificial Neural Network (ANN) was chosen because it is well-suited for tabular healthcare data and capable of capturing complex non-linear feature interactions.

The consistent model architecture across clients ensures compatibility during federated aggregation.

Before training, each client performs feature scaling using sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler to normalize input features and improve convergence stability.

At the beginning of each FL round, the client synchronizes its model with the global model parameters received from the server, ensuring all clients begin from a shared baseline.

Local training is conducted for a fixed number of LOCAL_EPOCHS using mini-batches (torch.utils.data.DataLoader, BATCH_SIZE = 32).

Training utilizes the binary cross-entropy with logits loss (torch.nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss()), which integrates a sigmoid activation with cross-entropy loss.

Optimization is handled by Adam (torch.optim.Adam), chosen for its adaptive learning rate and computational efficiency.

In each training iteration, gradients are zeroed, a forward pass is computed, loss is evaluated, and parameters are updated via backpropagation (loss.backward() and optimizer.step()).

Upon completion, each client computes its local update as the difference between the trained local parameters and the received global parameters.

This difference is flattened into a NumPy array (flattened_local_update), which constitutes the client’s contribution to the global model aggregation phase.

Phase 3: Statistical Robustness and Evaluation

To ensure statistical rigor and reproducibility, all experimental configurations were executed with five different random seeds.

Performance metrics: Accuracy, Precision, and Recall are reported as the Mean ± and Standard Deviation σ across these runs, providing confidence intervals and reducing the impact of stochastic variations.

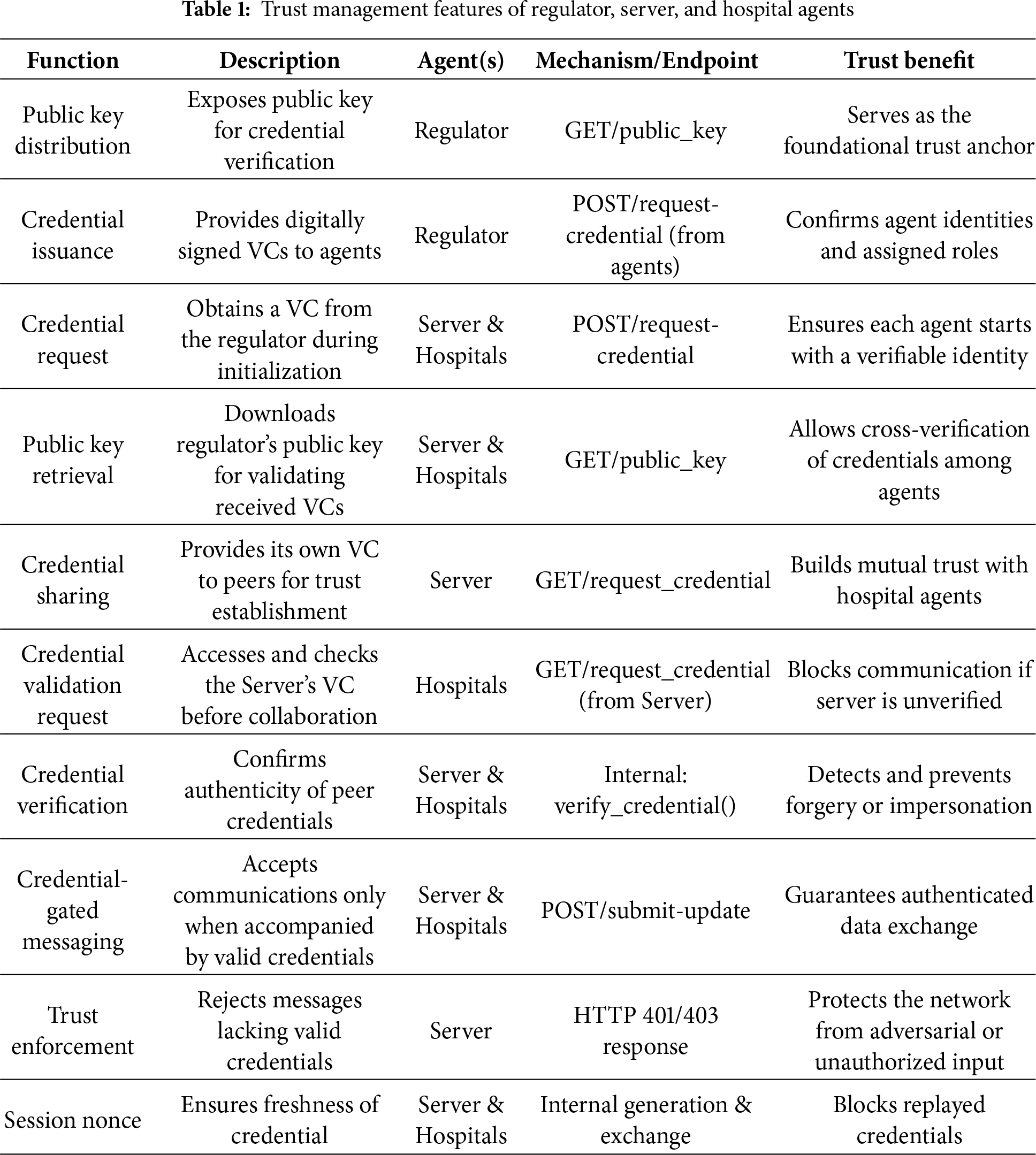

5.1 Analysis of the Proposed System

This section analyzes the trust management and mutual authentication process of the proposed system and how the Regulator, Server, and Hospital agents utilize verifiable credentials, cryptographic verification, and secure protocols to ensure identity assurance, mutual authentication, and policy-based trust enforcement. Table 1 summarizes the main trust features.

Table 1 above shows the trust anchors of all the agents, the Regulator anchors trust by issuing credentials and publishing its public key, while the Server and Hospitals obtain these credentials and validate trust through key retrieval. Agents establish mutual authentication by exchanging and verifying credentials before interaction with communication strictly gated by credential checks. Any unauthorized or unverified requests are blocked, maintaining a rigorous trust boundary across the system.

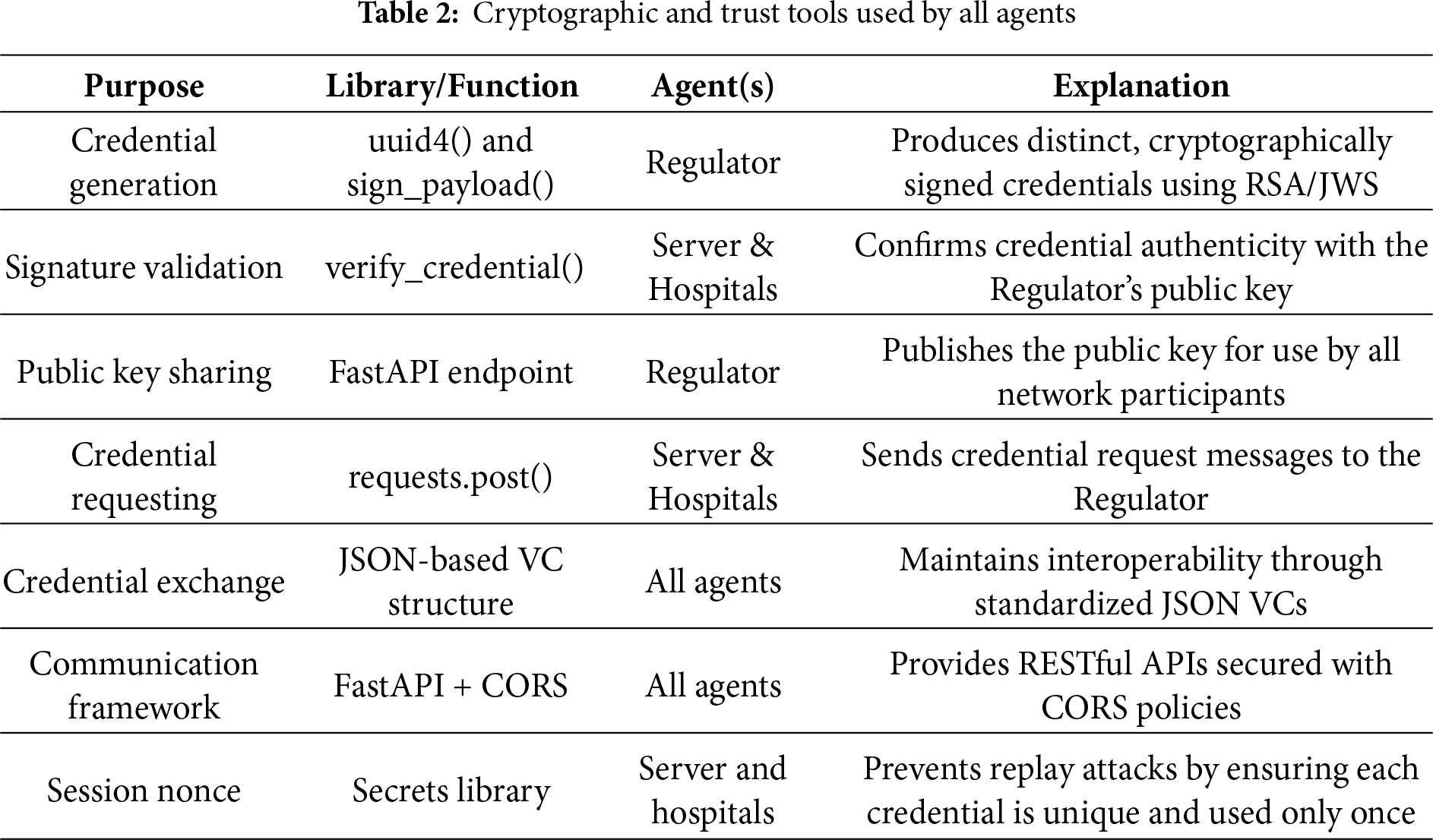

Table 2 below shows the cryptographic and trust tools used by all agents.

In Table 2 above, the tools used to enforce trust are presented. The regulator uses cryptographic signing together with the uuid4() function. The Regulator employs the uuid4() function along with cryptographic signing to generate unique verifiable credentials, while Server and Hospital agents validate them through the verify_credential() method using the Regulator’s public key. This key is shared via a designated FastAPI endpoint. Servers and Hospitals initiate credential requests using requests.post(), with credentials exchanged in a standardized JSON format. Agent communication is secured using FastAPI together with CORS policies, ensuring reliable and interoperable interactions. Additionally, a session nonce is employed by both the Server and Hospital agents to guarantee the freshness of each authentication or credential verification exchange, preventing replay attacks by ensuring that every credential or message is unique and can only be used once.

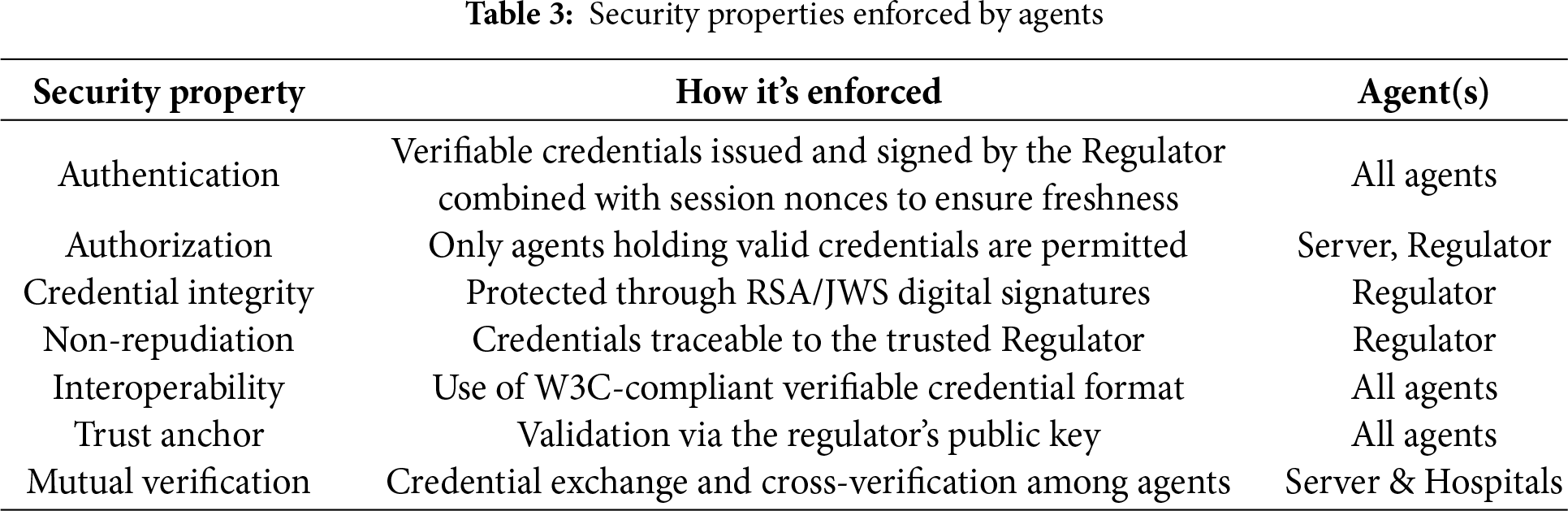

Table 3 below summarizes the security features enforced by the system’s agents. Each agent authenticates through verifiable credentials signed by the Regulator, ensuring trusted identities. Authorization is maintained by restricting interactions to agents holding valid credentials, particularly at the Server and Regulator. The use of RSA/JWS digital signatures, tied to a trusted issuer, guarantees credential integrity and non-repudiation. Compliance with the W3C verifiable credential standard enables interoperability, while the Regulator’s public key functions as the shared trust anchor across the system. Mutual verification between the Server and Hospitals ensures that data exchanges occur solely between authenticated parties.

For security analysis, an attack model was adopted to simulate potential strategies that an adversary might employ to compromise the system. To demonstrate the strength of the proposed system in comparison with the existing system, a model poisoning attack model was employed.

A model poisoning attack occurs when a malicious participant in federated learning intentionally sends altered model updates to compromise the global model. The attacker’s aim may be to decrease overall accuracy or implant hidden behaviors [29]. We evaluate our system’s resistance against such attacks, demonstrating how the proposed enhanced off-chain mutual authentication system can effectively mitigate model poisoning in a federated learning environment.

5.2.1 Experimental Setup for the Model Poisoning Attack

To illustrate model poisoning and test the strength of our system, we poisoned the data of some clients. The poisoning process converted every input in their datasets to 0. Training on such data produced biased local models, whose updates were intended to significantly degrade performance. These malicious clients aimed to submit corrupted updates to the server, skewing the aggregation toward class 0 predictions, thereby compromising the global model, reducing accuracy, and increasing false negatives.

To ensure the stability of our results, all comparative scenarios were carried out using 5 different random seeds. The mean µ and standard deviation σ of each scenario were used to provide statistical confidence bounds to measure observed utility and resilience.

To test the effectiveness of our framework, we carried out four runs across four scenarios.

For the first run, we carried out FL with the fifteen honest clients; this will serve as a baseline for evaluating our proposed framework.

For the second run, we carried out FL without mutual authentication. During the second run, all 15 clients, 12 honest clients and 3 rogue clients carried out local training and sent updates to the server; the server received and aggregated these updates.

In the third run, we carried out FL with the proposed decentralized identity framework. During the third run, the 12 honest clients who possessed valid credentials were able to train their data and share model updates with the server. However, updates from the 3 malicious clients were identified and dropped by the server as they couldn’t present valid credentials.

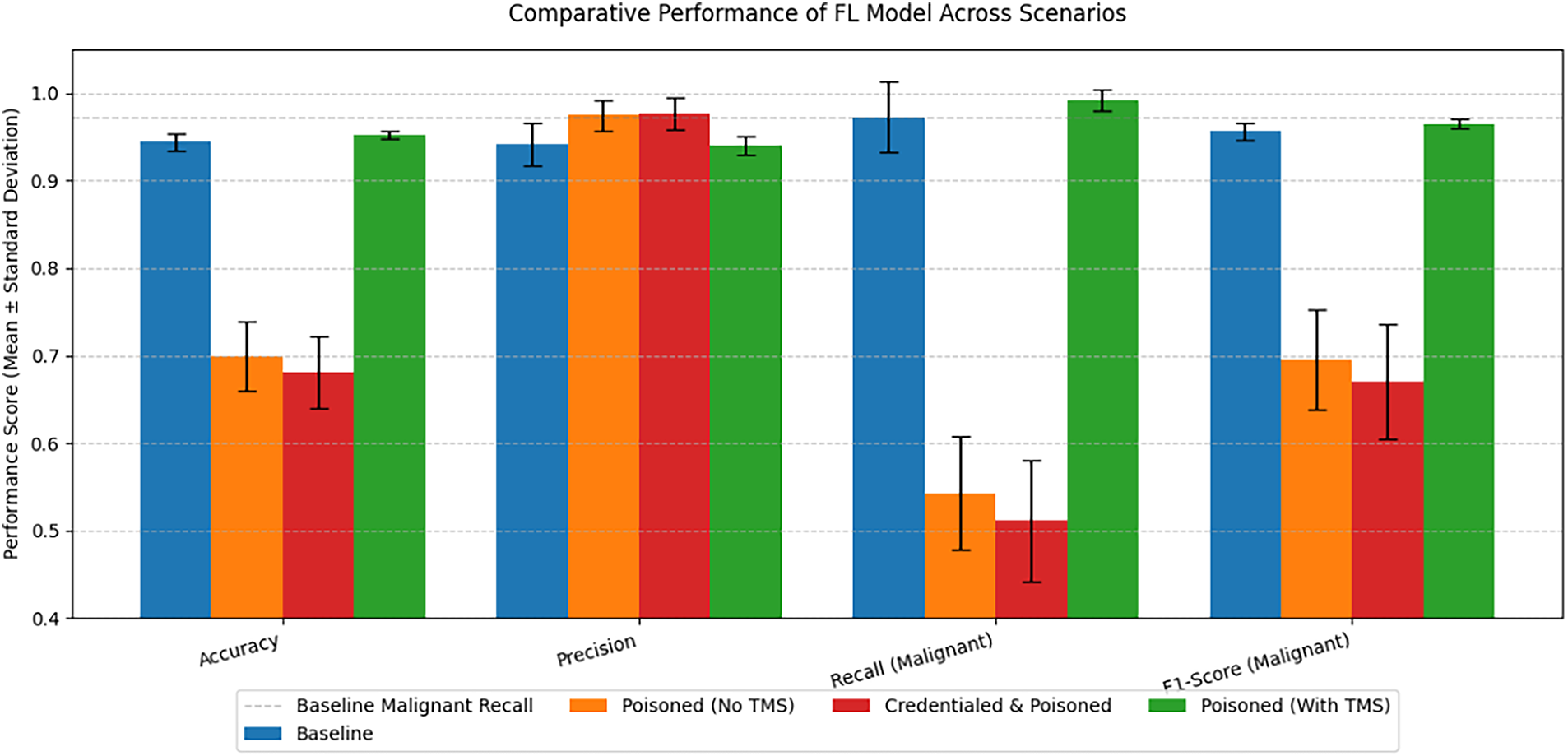

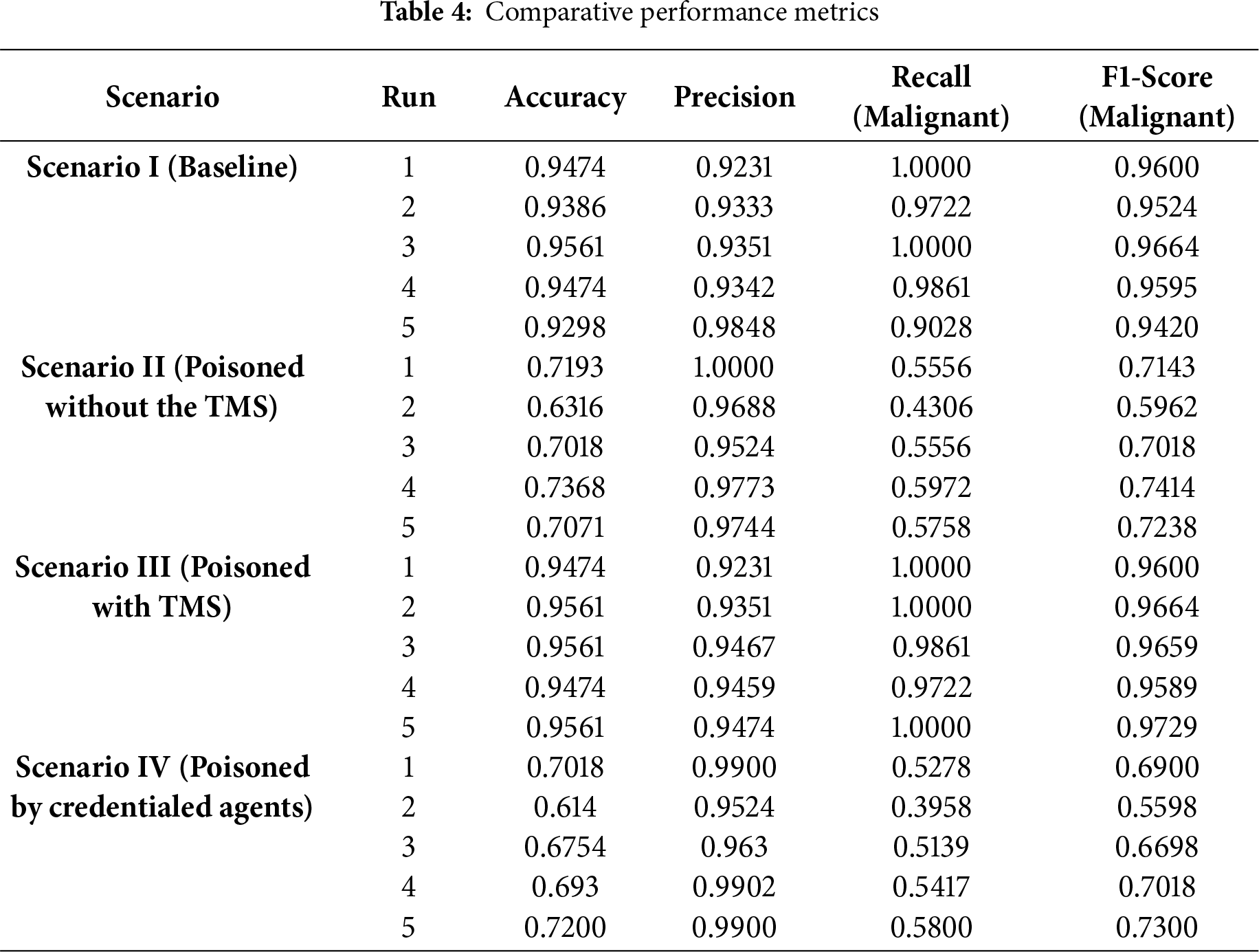

In the fourth run, we introduced malicious insiders using the 15 clients (12 honest and 3 rogue clients). This fourth run is carried out with the assumption that a credentialed client possessing valid DID and VC goes rogue. Fig. 10 is a comparative analysis of the performance of the model across the three runs.

Figure 10: Comprehensive model performance across all scenarios

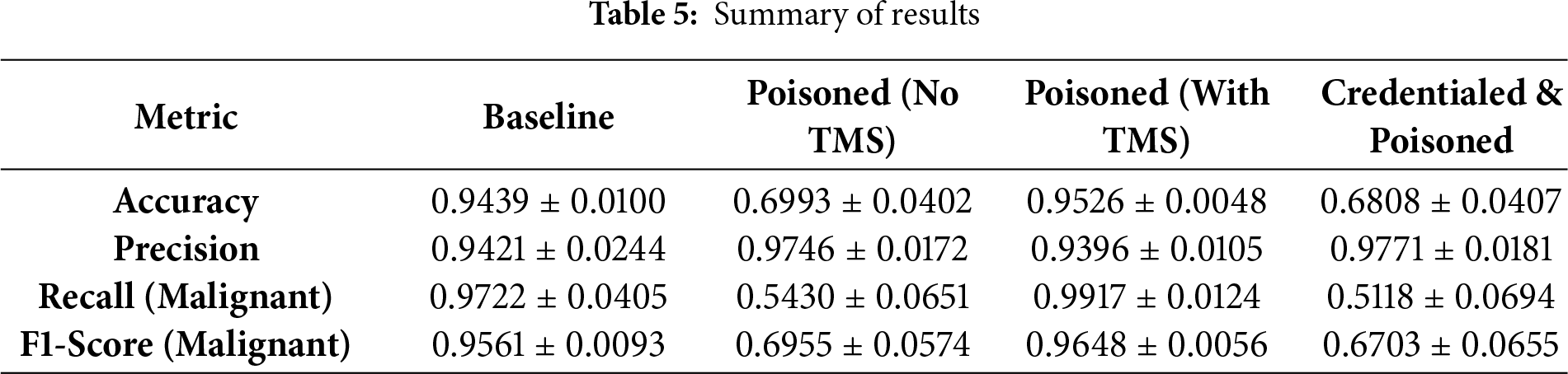

The performance metrics reported below represent the Mean µ and Standard Deviation σ providing statistical confidence bounds on the observed utility and resilience.

The first scenario establishes the baseline for model performance under normal conditions. In this scenario 15 clients carried out model training and submitted updates for aggregation. The model achieves consistently high overall accuracy with (µ = 0.9439 σ ±= 0.0100) with a malignant recall of (µ = 0.9722 ± σ = 0.0405). This high recall is essential in, oncology where missed cancers (false negatives) are the highly risky. The low standard deviation across all metrics confirms the stability and reproducibility of the federated learning process with trustworthy clients.

Introducing three malicious clients without the admission control of the trust management system dropped the model’s reliability. The overall accuracy felled to (µ = 0.6993 σ = ±0.0402), and the malignant recall dropped severely to (µ = 0.5430, σ = ±0.0651) indicating that a good number of malignant cases were missed. This is an indication of a model poisoning attack.

The third scenario demonstrates the effectiveness of the Trust Management System (TMS). The model’s performance is fully restored to near-baseline levels, with minimal deviation: accuracy (µ = 0.9526 σ = ±0.0048) and malignant recall (µ = 0.9917 σ = ±0.0124). The restoration of malignant recall proves that the TMS effectively isolates and neutralizes the poisoning vector. The low standard deviations (e.g., σ = ±0.0048 for Accuracy) confirm the defence mechanism is robust and predictable across different runs.

The fourth experiment was done with the assumption that a trusted client goes rogue after being issued a valid credential. In this scenario, the 15 clients were issued valid credentials (establishing digital identity and provenance), yet the 3 malicious clients still carried out model poisoning attack, thus degrading model performance. The results were statistically identical to the unprotected scenario: accuracy (µ = 0.6808 σ = ±0.0407) and malignant recall (µ = 0.5118 σ = ±0.0694). This result is important as it demonstrates the functional boundary of the identity layer; the DID/VC framework successfully establishes provenance and ensures updates originate from a credentialed source, yet it cannot infer or block malicious intent from a validated participant. Consequently, simple identity-centric access control is inherently insufficient against sophisticated, credentialed internal threats.

The gains from the third run do not come from regularization or robust aggregation; they arise from identity-centric admission control that guarantees update provenance and prevents untrusted gradient contributions from ever entering the aggregation path. This shrinks the attack surface, preserves the statistical properties of honest updates, and stabilizes class-wise metrics. Table 4 shows the comparative performance metrics across all scenarios showing results gotten from individual runs. Table 5 is the summary of results showing the mean µ and standard deviation σ of performance metrics across scenarios.

To empirically validate the architectural decision to utilize a Decentralized Identifier DID and VC framework as a lightweight, off-chain trust mechanism, we quantify the cryptographic and communication overhead introduced by the mutual authentication layer. This analysis directly addresses the scalability and efficiency concerns typically associated with distributed trust systems. The key metrics measured are the latency of credential issuance and the latency of verification, as these represent the one-time setup cost and the per-round runtime cost, respectively.

5.3.1 Trust Establishment Latency Benchmarks

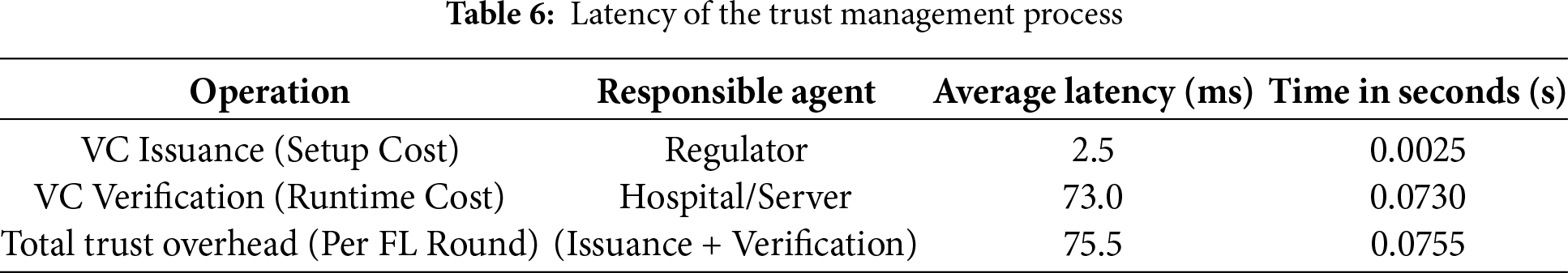

The performance measurements were carried out for both credential issuance and credential verification. Issuance involves the Regulator generating a JSON Web Signature (JWS) protected VC, while verification involves JWS validation, session nonce checking, and an HTTP request to the Regulator for revocation status. Table 6 shows the trust establishment latency for each operation.

The results confirm that the cryptographic overhead introduced by the DID/VC layer is minimal and highly conducive to a scalable, low-latency FL environment.

For credential issuance, the average issuance time recorded was 2.5 ms, this demonstrates that the Regulator can process credential requests nearly instantaneously.

The credential verification process represents the critical runtime cost incurred by the communicating agents during each FL round; this averaged 73 ms.

5.3.2 Comparative Analysis with Blockchain DLT

For comparative analysis, we compared the latency of our system with that of FLCoin reported in Ren et al. [49]. The comparative result is presented below;

Ren et al. [49] proposed an FLCoin approach which utilizes an optimized committee-based consensus protocol designed specifically for FL. The reported latency was around 3 s or 3000 ms.

Our entire mutual authentication overhead of 75.5 ms is approximately 39.7 times faster than the consensus step alone in an optimized distributed ledger-based system.

6 Summary, Conclusion and Suggestions for Future Research

This study presents a novel mutual authentication framework that directly addresses the challenge of trust and security in FL for privacy-sensitive domains. While existing privacy-preserving techniques often focus on protecting data during training, they largely overlook the fundamental issue of authenticating participating entities. This gap has left FL systems vulnerable to malicious actors and model poisoning attacks. Traditional blockchain-based trust solutions are often resource-intensive and prone to metadata leakage.

To overcome these limitations, the proposed solution leverages a lightweight, off-chain framework built on DIDs and cryptographically signed VCs. The architecture comprises a designated Regulator agent that issues unique VCs to authorized participants, enabling secure, peer-to-peer mutual authentication between servers and clients. Session nonces were employed to guarantee freshness of credential exchanges and prevent replay attacks.

The framework’s efficacy was rigorously evaluated in a simulated healthcare environment using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset. The experimental setup included 15 clients with heterogeneous, non-IID data, including honest and malicious participants attempting to submit falsified model updates. To ensure statistical robustness, each scenario was executed across five random seeds, with results reported as Mean ± Standard Deviation for key metrics.

The results confirmed the strength of the proposed system: unverified clients were automatically rejected, preventing them from compromising the integrity of the global model. The final aggregated model, built exclusively from verified contributions, achieved high accuracy (µ ≈ 0.95) and strong malignant recall (µ ≈ 0.99), while maintaining low trust management overhead (~75.5 ms per FL round). These results indicate that while identity-centric admission control reliably ensures the provenance of model updates and blocks untrusted participants, it cannot prevent malicious behavior from credentialed clients, highlighting a functional boundary of the framework.

This study presents a scalable and efficient mutual authentication framework for FL in healthcare, addressing a critical security gap in existing systems. By leveraging a lightweight, off-chain DID and VC-based identity management approach, the framework enables secure, peer-to-peer mutual authentication among participants. Session nonces ensure freshness and prevent replay attacks, enhancing trust in credential exchanges.

Experiments with 15 heterogeneous, non-IID clients across five random seeds demonstrate that the framework effectively blocks unverified or untrusted clients from submitting poisoned updates, preserving global model accuracy (µ ≈ 0.95) and malignant recall (µ ≈ 0.99) with minimal overhead (~75.5 ms per FL round). These results confirm that identity-centric admission control reliably ensures provenance and mitigates attacks from untrusted participants, while highlighting a limitation; credentialed clients acting maliciously cannot be prevented by authentication alone, underscoring the need for complementary defences like robust aggregation or anomaly detection.

6.3 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

While the proposed mutual authentication framework shows promising results for secure federated learning in healthcare, it has some constraints. The Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset is relatively small and does not fully reflect real-world healthcare data, so larger and more diverse datasets are needed to evaluate scalability and robustness. Also, the identity-centric admission control blocks unverified participants; however, it cannot prevent malicious behaviours from credentialed clients, who could still submit poisoned updates.

Future research could explore the integration of DID/VC-based authentication with additional privacy-preserving techniques, such as differential privacy or secure aggregation to establish multi-layered protection. Additionally, evaluating the framework against a broader range of adversarial attacks, including backdoor and inference attacks would provide a more comprehensive security assessment.

Furthermore, testing the framework in large-scale, real-world environments with heterogeneous clients and hardware would help quantify latency, scalability, and robustness under realistic conditions.

Finally, extending the framework to other domains and machine learning models, including finance, IoT, natural language processing, and computer vision, would assess generalizability and applicability beyond healthcare. Collectively, these directions aim to enhance the robustness, versatility, and practical adoption of secure, identity-centric federated learning systems.

Acknowledgement: Special thanks to the staff members of the Department of Computer Science, Edo State University Iyamho.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm the following contributions: Samuel Acheme was responsible for Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing of original draft, Visualization. Glory Nosawaru Edegbe was responsible for Supervision, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Banabilah S, Aloqaily M, Alsayed E, Malik N, Jararweh Y. Federated learning review: fundamentals, enabling technologies, and future applications. Inf Process Manage. 2022;59(6):103061. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wen J, Zhang Z, Lan Y, Cui Z, Cai J, Zhang W. A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2023;14(2):513–35. doi:10.1007/s13042-022-01647-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Samuel A, Nosawaru Edegbe G. Federated machine learning solutions: a systematic review. NIPES J Sci Technol Res. 2025;7(3):51–65. doi:10.37933/nipes/7.3.2025.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Fang H, Qian Q. Privacy preserving machine learning with homomorphic encryption and federated learning. Future Internet. 2021;13(4):94. doi:10.3390/fi13040094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Abramson W, Hall AJ, Papadopoulos P, Pitropakis N, Buchanan WJ. A distributed trust framework for privacy-preserving machine learning. In: Trust, privacy and security in digital business. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 205–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58986-8_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhu H, Zhang H, Jin Y. From federated learning to federated neural architecture search: a survey. Complex Intell Syst. 2021;7(2):639–57. doi:10.1007/s40747-020-00247-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Edegbe GN, Samuel A. A systematic review of centralized and decentralized machine learning models: security concerns, defenses and future directions. NIPES-J Sci Technol Res. 2024;6(4):161–75. [Google Scholar]

8. Imteaj A, Thakker U, Wang S, Li J, Amini MH. A survey on federated learning for resource-constrained IoT devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(1):1–24. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3095077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Arachchige PCM, Bertok P, Khalil I, Liu D, Camtepe S, Atiquzzaman M. A trustworthy privacy preserving framework for machine learning in industrial IoT systems. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;16(9):6092–102. doi:10.1109/TII.2020.2974555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lo SK, Lu Q, Paik HY, Zhu L. FLRA: a reference architecture for federated learning systems. In: European Conference on Software Architecture; 2021 Sep 13–17; Virtual. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 83–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-86044-8_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang X, Mavromatis A, Vafeas A, Nejabati R, Simeonidou D. Federated feature selection for horizontal federated learning in IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(11):10095–112. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3237032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Brand M, Pradel G. Practical privacy-preserving machine learning using fully homomorphic encryption. 2023. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/1320. [Google Scholar]

13. El Mestari SZ, Lenzini G, Demirci H. Preserving data privacy in machine learning systems. Comput Secur. 2024;137:103605. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Frimpong E, Nguyen K, Budzys M, Khan T, Michalas A. GuardML: efficient privacy-preserving machine learning services through hybrid homomorphic encryption. In: Proceedings of the 39th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing; 2024 Apr 8–12; Avila, Spain. p. 953–62. doi:10.1145/3605098.3635983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Grover J, Misra R. Keeping it low-key: modern-day approaches to privacy-preserving machine learning. In: Data protection in a post-pandemic society: laws, regulations, best practices and recent solutions. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 49–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-34006-2_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rofougaran R, Yoo S, Tseng HH, Chen SY. Federated quantum machine learning with differential privacy. In: ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 9811–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10447155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Su Y, Huang C, Zhu W, Lyu X, Ji F. Multi-party diabetes mellitus risk prediction based on secure federated learning. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;85:104881. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zapechnikov S. Secure multi-party computations for privacy-preserving machine learning. Procedia Comput Sci. 2022;213:523–7. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Garzon SR, Yildiz H, Küpper A. Decentralized identifiers and self-sovereign identity in 6G. IEEE Netw. 2022;36(4):142–8. doi:10.1109/MNET.009.2100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bolte P, Jetschni J. Self-sovereign identity: development of an implementation-based evaluation framework for verifiable credential SDKs [master’s thesis]. Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany: Technische Hochschule Brandenburg; 2021. [Google Scholar]