Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Systematic Review of Frameworks for the Detection and Prevention of Card-Not-Present (CNP) Fraud

Department of Computer Science, College of Basic and Applied Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, P.O. Box LG 25, Ghana

* Corresponding Author: Kwabena Owusu-Mensah. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2026, 8, 33-92. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2026.074265

Received 07 October 2025; Accepted 09 December 2025; Issue published 20 January 2026

Abstract

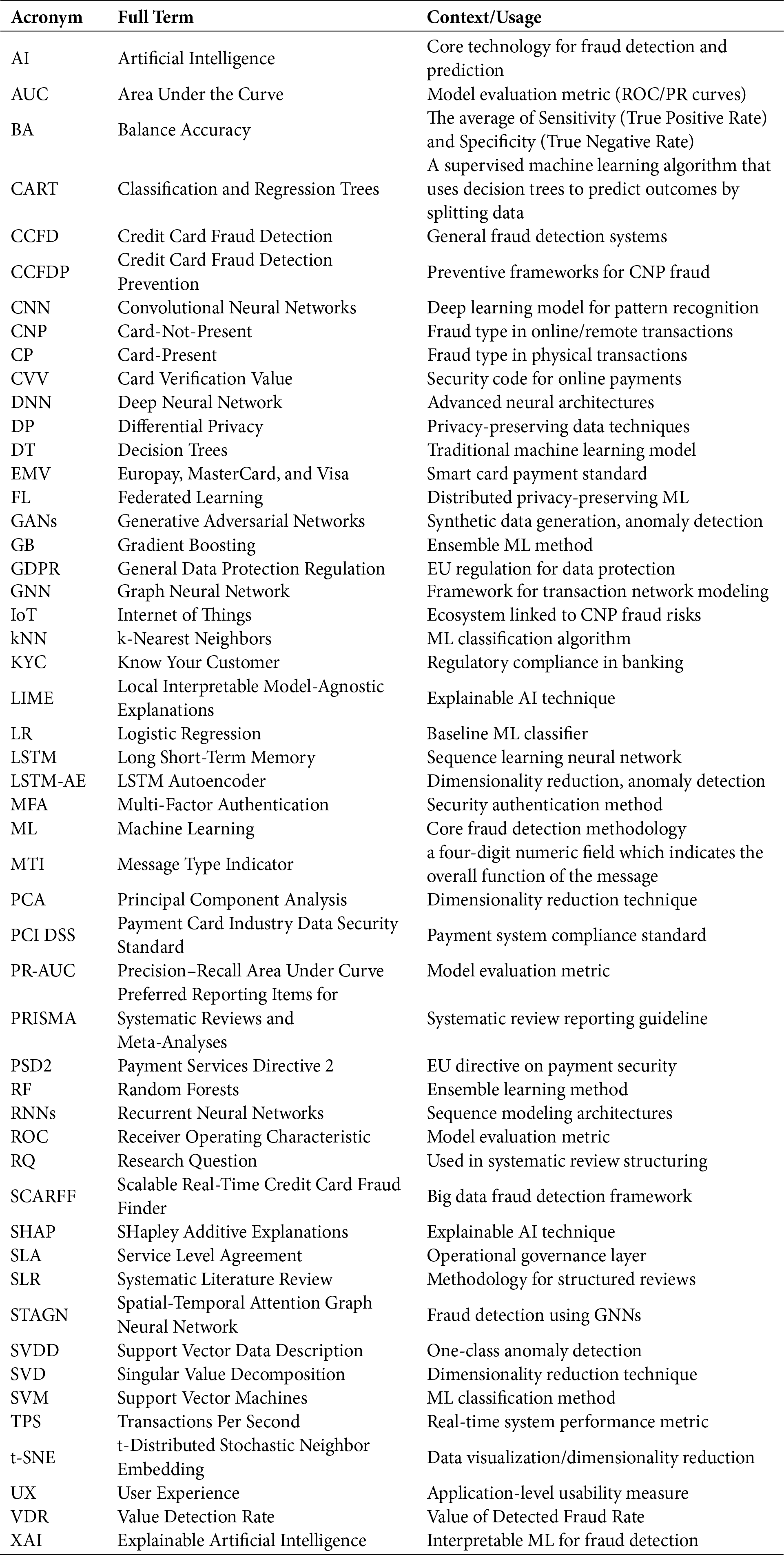

The rapid growth of digital payment systems and remote financial services has led to a significant increase in Card-Not-Present (CNP) fraud, which is now the primary source of card-related losses worldwide. Traditional rule-based fraud detection methods are becoming insufficient due to several challenges, including data imbalance, concept drift, privacy concerns, and limited interpretability. In response to these issues, a systematic review of twenty-four CNP fraud detection frameworks developed between 2014 and 2025 was conducted. This review aimed to identify the technologies, strategies, and design considerations necessary for adaptive solutions that align with evolving regulatory standards. The findings indicate a shift from static, supervised models to dynamic approaches, such as hybrid and federated architectures, which utilize advanced technologies like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), blockchain auditing, and privacy-preserving learning. These modern frameworks demonstrate impressive performance metrics, achieving F1 scores between 0.85 and 0.99 and AUC values exceeding 0.93, while also complying with regulatory standards, including GDPR and PCI-DSS. The review identified six key design pillars essential for effective CNP fraud mitigation: scalable architecture, privacy-preserving governance, adaptive learning, interpretability, cost optimization, and integrated continuous evaluation. This study presents a design-centric framework that emphasizes scalability, ethical governance, and explainable intelligence. The review suggests that graph-enabled, federated, and self-optimizing frameworks represent the future of securing digital payment environments and enhancing CNP fraud detection.Keywords

The rapid digitization of global commerce has fundamentally transformed the mechanisms of financial transactions, resulting in both unprecedented levels of convenience and a marked expansion of the associated threat landscape. One of the most prevalent and economically detrimental of these threats is Card-Not-Present (CNP) fraud, in which malicious actors exploit online and mobile platforms to initiate unauthorized transactions without the physical presence of a payment card.

Globally reported losses due to card fraud have seen a significant increase, rising from $18.11 billion in 2014 to an estimated $35.79 billion by 2024, with projections indicating a further escalation to $43.47 billion by 2028 [1]. Within this total, losses attributable to card-not-present (CNP) transactions have escalated from approximately $10 billion (representing 55% of total losses) in 2014 to around $27 billion (approximately 74%) in 2024, with expectations that these losses will surpass $30 billion annually by 2028 [2]. This upward trend underscores the urgent need for enhanced security measures within the online payment ecosystem and highlights the necessity for the development of CNP-specific detection tools grounded in a comprehensive understanding of relevant technologies, methodologies, and system-level design principles. In response to these challenges, a diverse array of solutions has begun to emerge, including machine-learning classifiers, federated-learning systems, and graph-based anomaly detectors. Despite this proliferation of solutions, significant gaps persist regarding systematic organization, standardized evaluation metrics, and design considerations focused on practical deployment [3,4]. As tactics employed by fraudsters evolve, many existing frameworks exhibit limitations in adaptability, explainability, and regulatory compliance, which further reinforces the imperative to address these deficiencies.

Prior surveys in the domain of financial fraud analytics have predominantly offered broad, model-centric overviews, such as taxonomies of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, without isolating the specific contexts of CNP transactions or the unique constraints associated with remote payments [5]. Also, the literature remains primarily focused on accuracy metrics, which can produce overly optimistic outcomes due to issues related to dataset handling or the limitations inherent in proxy transformations that may weaken their applicability to real-time CNP operations [3,6,7]. Simultaneously, surveys that emphasize privacy and governance typically address attack taxonomies and countermeasures at the learning layer but generally fail to provide an end-to-end, framework-level treatment of CNP pipelines [8].

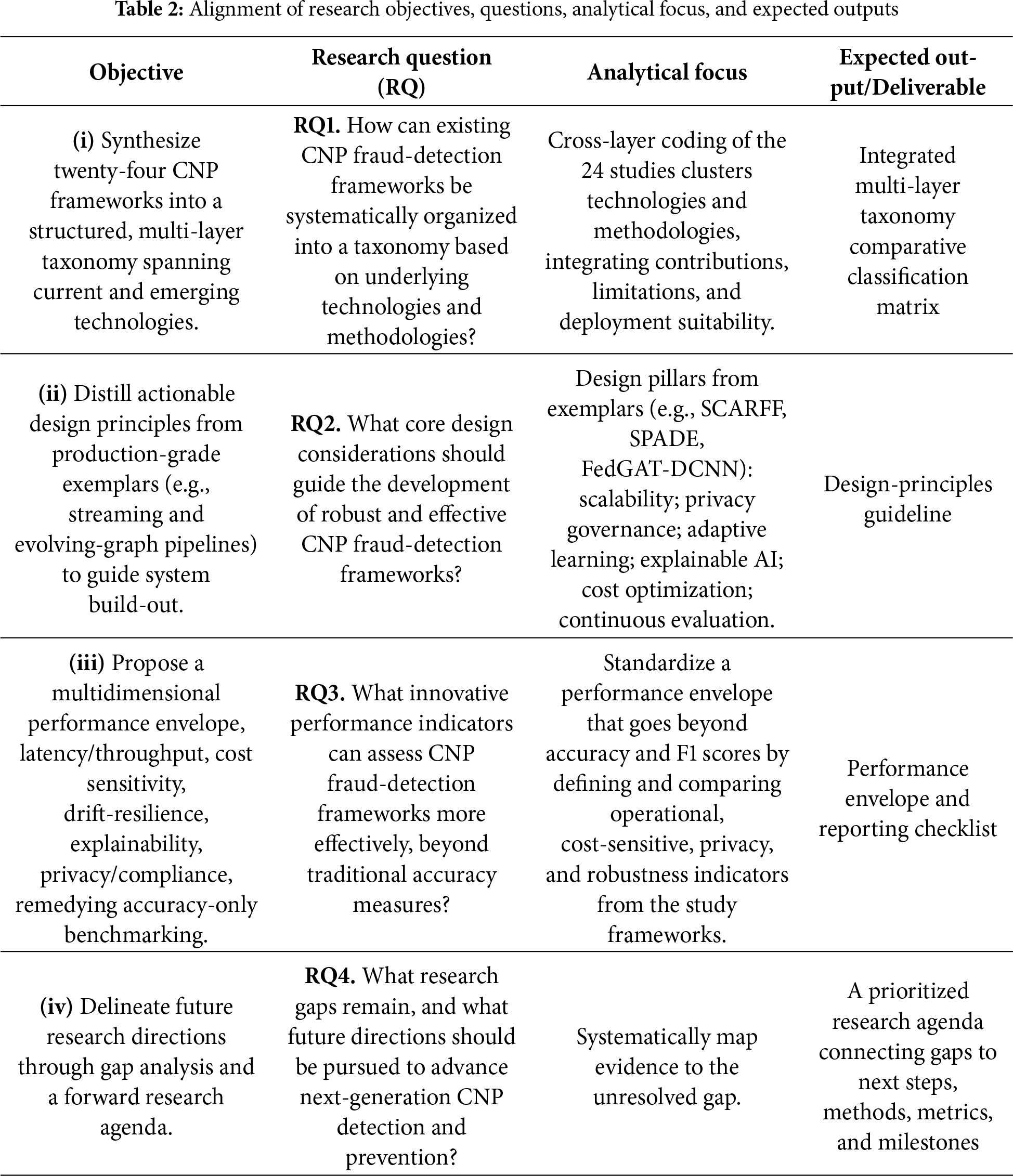

In contrast, this review is specifically focused on CNP fraud, framework-oriented, and mindful of deployment considerations. It: (i) synthesizes twenty-four CNP frameworks into a structured, multi-layer taxonomy that encompasses both current and emerging technologies; (ii) extracts actionable design principles from production-grade exemplars, such as streaming and evolving graph pipelines, to guide system development; (iii) proposes a multidimensional performance envelope that incorporates factors such as latency, throughput, cost sensitivity, drift resilience, explainability, and privacy/compliance, thereby addressing the limitations associated with accuracy-only benchmarking; and (iv) delineates future research directions through gap analysis and establishes a coherent research agenda.

The urgency of this agenda is underscored by the continuing rise and concentration of losses within CNP channels, which currently account for the majority of global card fraud losses and are anticipated to grow further. This trend emphasizes the critical need for deployment-grade, privacy-preserving solutions tailored to the complexities of CNP transactions.

Rationale and Contributions of This Review

This review is motivated by several convergent challenges within the domain of CNP fraud detection. First, the field currently lacks a unified taxonomy for its methodological frameworks, resulting in fragmented research endeavors that impede direct model comparison and hinder coherent scholarly progress. Second, the prevailing reliance on conventional performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) fails to capture critical operational dimensions, such as computational latency, scalability, the economic impact of false positives, and regulatory adherence, which are paramount to the practical deployment and viability of these systems. Third, existing literature offers insufficient guidance on the architectural and design-level decisions necessary to ensure robustness, adaptability, and effective human-AI collaboration. While pioneering contributions, such as Scalable Real-time Credit Card Fraud Finder (SCARFF) [9] and Federated Learning, Graph Attention Networks and Delineated Convolutional Networks (FedGAT-DCNN) [10], have demonstrated scalable and privacy-aware designs, they often remain disconnected from the complexities of production environments. Finally, in the face of rapidly evolving fraud tactics and financial regulations, there is a pressing need to systematically identify extant literature gaps and to chart a course for integrating emerging technological paradigms.

Consequently, this review seeks to consolidate, extend, and reorient contemporary CNP fraud detection research toward the imperatives of practical implementation, system-wide resilience, and cross-institutional collaboration.

Building on this motivation, the review makes four principal, interlocking contributions:

1. A Systematic Taxonomy of CNP Fraud Detection Frameworks. This work introduces a structured taxonomy that classifies existing frameworks along two primary axes: technological architecture (e.g., machine learning, federated learning, graph neural networks, blockchain) and methodological approach (e.g., supervised learning, unsupervised anomaly detection, ensemble modeling). This taxonomy not only facilitates a systematic comparison of extant techniques but also provides a conceptual scaffold for guiding future research and development aimed at mitigating CNP fraud.

2. A Foundational Set of Design Principles for CNP Systems. Derived from a comprehensive, cross-comparative analysis of 24 distinct frameworks, this review distills a set of core design principles essential for next-generation fraud detection systems. These principles recommend multi-layered, modular architecture; real-time stream processing capabilities; adaptive learning pipelines to counteract concept drift; privacy-by-design methodologies; and the strategic integration of human-in-the-loop interfaces.

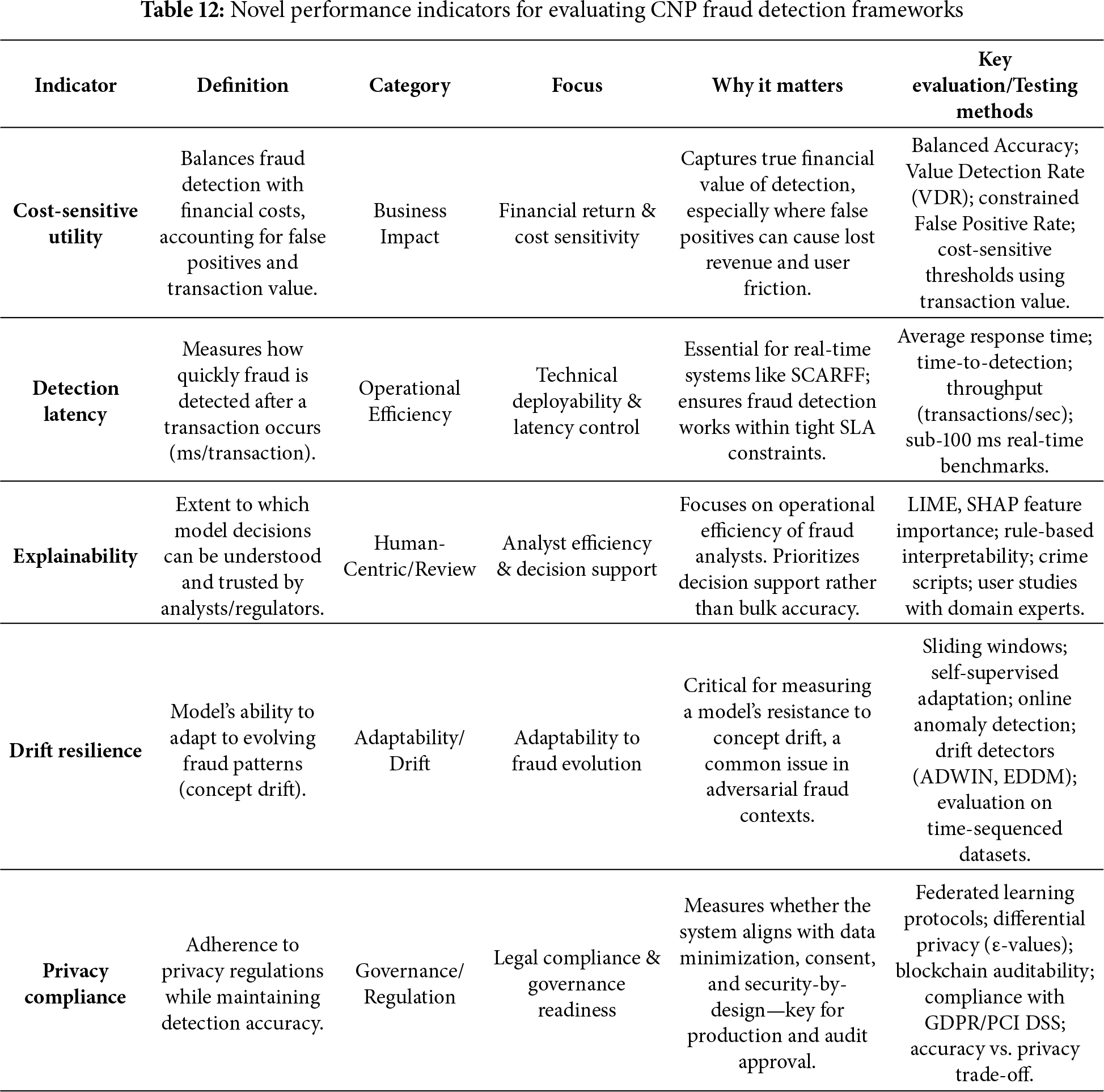

3. A Novel Multidimensional Framework for Performance Evaluation. Moving beyond traditional accuracy-based metrics, this review proposes a comprehensive suite of performance indicators that reflect the multifaceted demands of real-world deployment. This framework incorporates dimensions of cost-sensitive utility, detection latency, explainability, drift resilience, and privacy-compliance. By adopting this holistic evaluation paradigm, stakeholders can better assess a system’s operational efficacy, regulatory alignment, and ethical considerations.

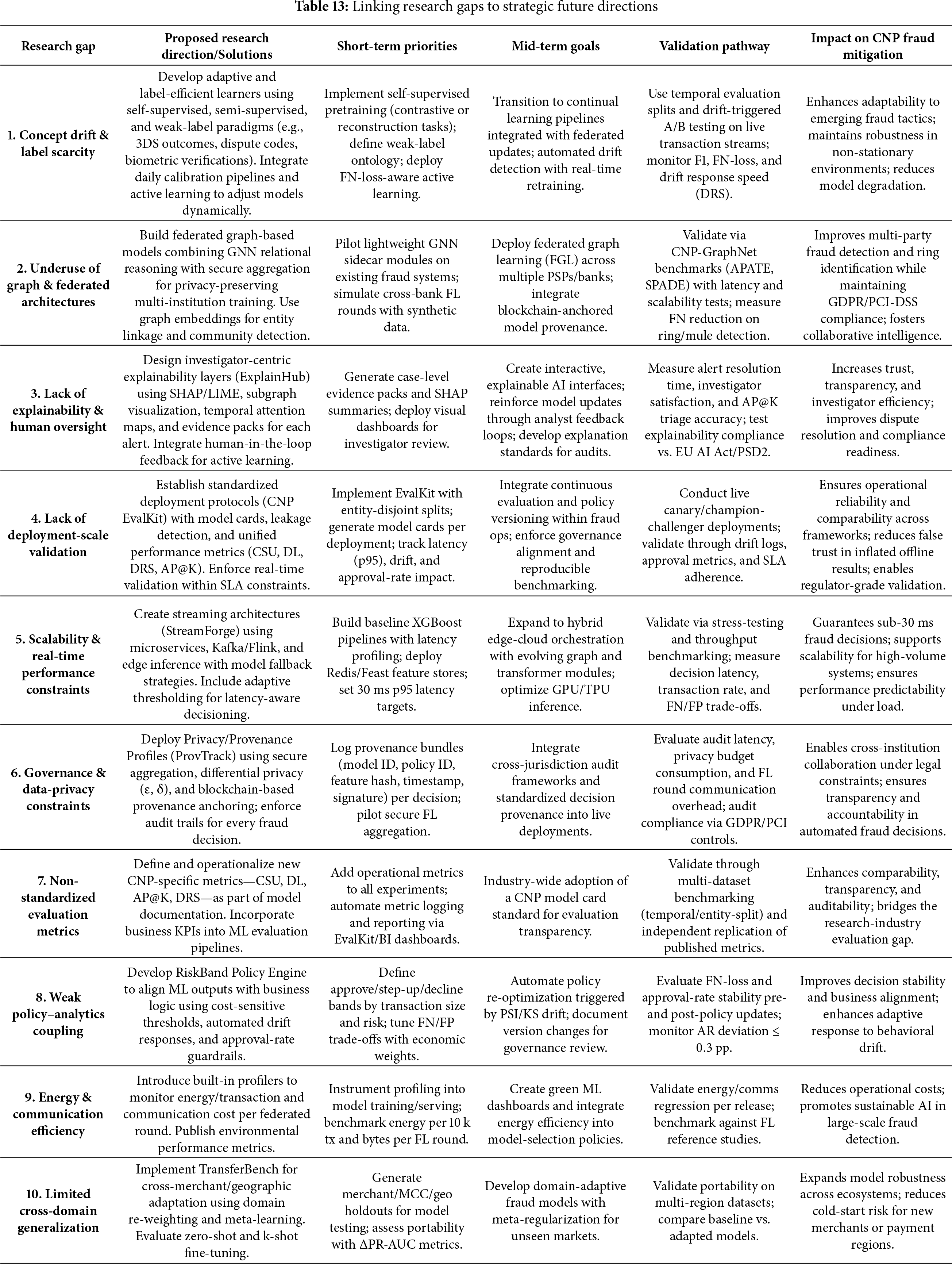

4. A Critical Gap Analysis and Forward-Looking Research Agenda. This work provides a critical synthesis of salient gaps in the current literature, highlighting deficiencies in areas such as concept drift handling, system scalability, empirical deployment validation, and explainability. In response, it proposes a strategic research agenda that prioritizes the exploration of emerging fields, including federated graph learning, explainable AI (XAI) frameworks, compliance-aware architectures, and secure, collaborative fraud intelligence sharing.

Collectively, these elements re-center CNP-fraud detection on system-level design and operational viability, offering a structured map for scholars and a practical blueprint for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

2 Card-Not-Present (CNP) Fraud

Card-not-present (CNP) fraud refers to the use of payment credentials for online or remote transactions where the cardholder is not physically present. Unlike card-present fraud, which is effectively mitigated by chip-and-PIN technology and Europay, MasterCard, and Visa (EMV) standards, CNP fraud depends entirely on digital verification methods. This reliance renders it particularly vulnerable to exploitation by cybercriminals [5]. The incidence of CNP fraud has surged in tandem with the global expansion of e-commerce, mobile banking, and digital wallets, posing a significant challenge for merchants, financial institutions, and regulatory bodies.

The lack of physical verification enables attackers to exploit vulnerabilities in digital channels, utilizing stolen, fabricated, or manipulated payment credentials. Furthermore, the globalization of payment systems, combined with the increasing sophistication of fraud tactics, exacerbates these risks. Fraudsters increasingly employ a hybrid approach, merging technical exploits, such as automated botnets and data breaches, with human-centric strategies, including phishing and social engineering, to circumvent detection systems [5,11].

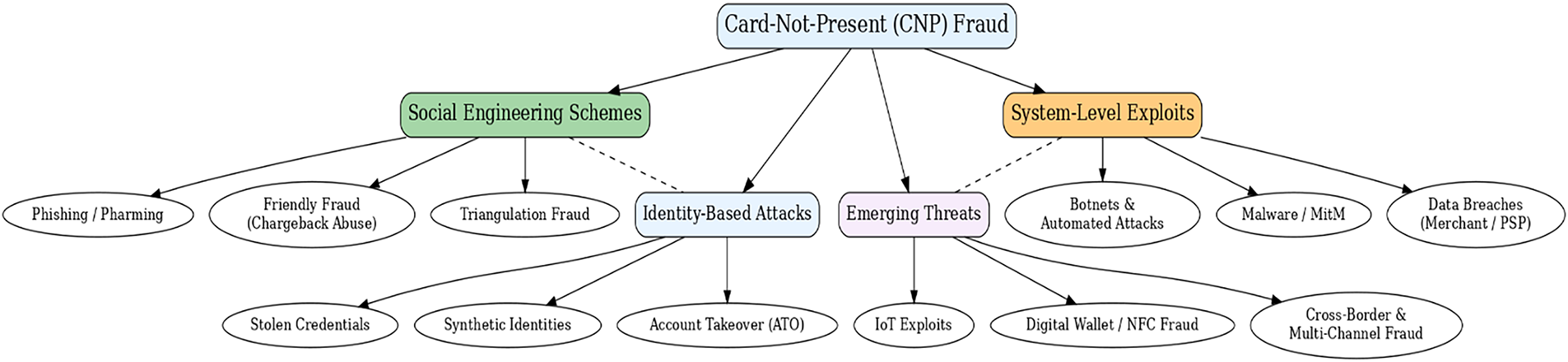

In our analysis, we categorize the major forms of CNP fraud into four overarching groups, reflecting both traditional and emergent dimensions of the threat landscape.

• Identity-based attacks involve the misuse or fabrication of customer credentials, including identity theft, account takeover, and synthetic identity fraud, all of which exploit weaknesses in authentication systems and customer verification processes.

• Social engineering schemes target the human element of payments, with fraudsters using deception through phishing, smishing, vishing, triangulation fraud, or even deliberate chargeback disputes (friendly fraud) to manipulate customers and merchants.

• System-level exploits focus on technological vulnerabilities within merchant platforms and payment infrastructures. These include merchant-side data breaches, botnet-driven credential stuffing, and large-scale automated attacks that overwhelm fraud filters.

• Emerging threats represent the newest frontier, where the rise of cross-border payments, digital wallets, and IoT ecosystems increasingly enables fraud. These environments introduce novel weaknesses in tokenization, device fingerprinting, and biometric verification.

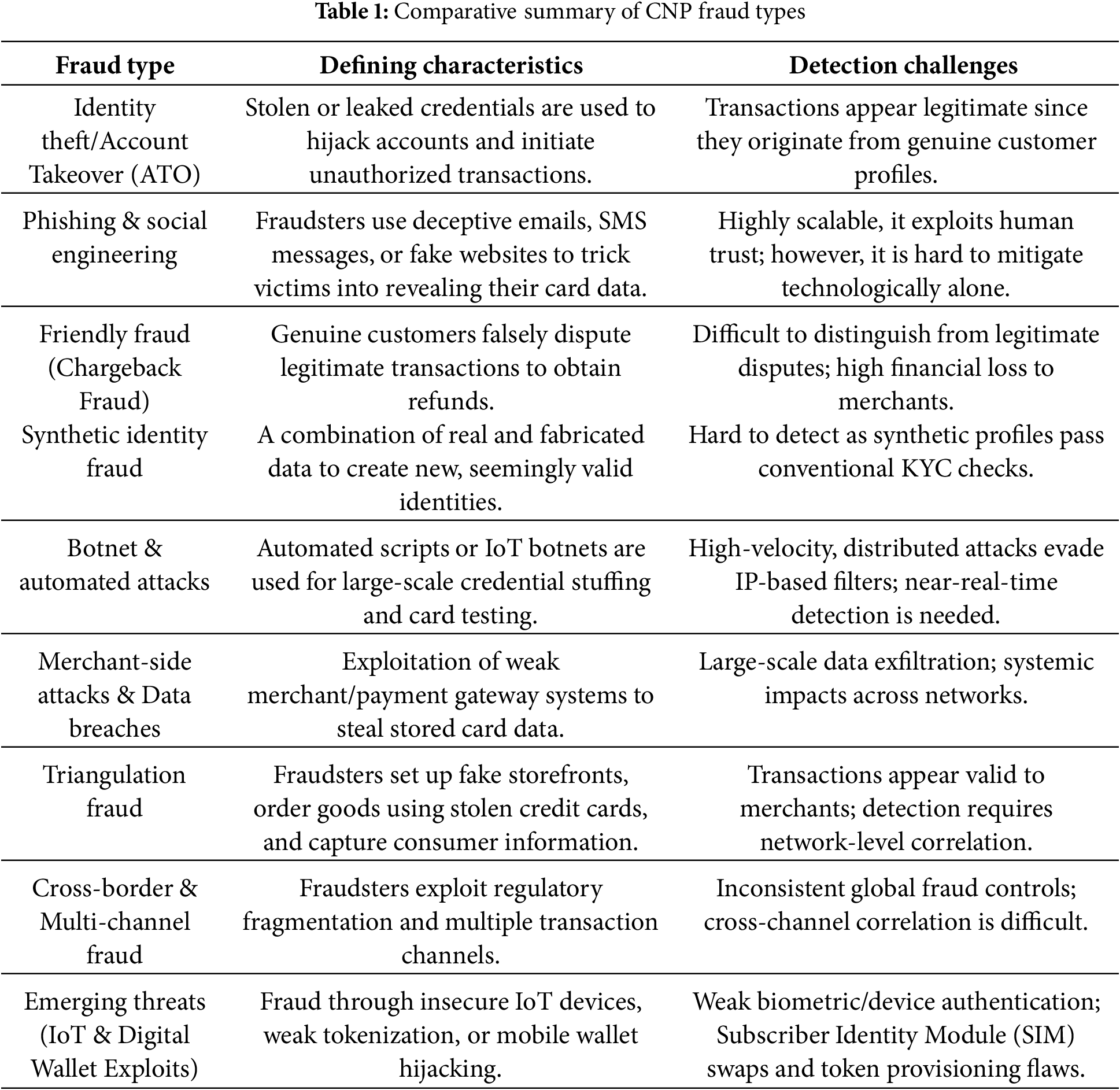

Each group encompasses multiple subtypes with distinct attack mechanisms, yet together they reveal a common theme: fraudsters adapt rapidly by combining technical sophistication with social manipulation to circumvent defenses. Fig. 1 illustrates a taxonomy of fraud types, presenting a structured visualization of their classification. Concurrently, Table 1 offers a comparative summary of their defining characteristics, detection challenges, and notable studies from the literature. This framework enhances the understanding of CNP fraud and equips researchers and practitioners with the insights necessary to develop targeted detection and prevention strategies.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of Card-Not-Present (CNP) fraud types organized into four major categories

2.1.1 Identity Theft and Account Takeover (ATO)

Identity theft and account takeover are among the most prevalent forms of CNP fraud, driven by the illicit acquisition and misuse of customer credentials. Attackers typically gain access to sensitive information, such as card numbers, card verification value (CVV) or card verification code (CVC) codes, billing addresses, and login credentials, through phishing campaigns, malware infections, large-scale data breaches, or black-market purchases [5,12].

Once stolen data is obtained, criminals can initiate ATO by hijacking legitimate customer profiles. This enables them to perform unauthorized transactions, alter delivery addresses, exploit stored payment methods, or launder funds through mule accounts. Unlike synthetic identity fraud, which constructs entirely new profiles, ATO exploits existing accounts, making detection particularly challenging. Transactions often appear legitimate, as they originate from trusted devices, IP addresses, or historical user accounts.

Recent studies show that account takeover (ATO) attacks are highly automated, with adversaries using credential-stuffing botnets to replay large volumes of stolen credentials across multiple merchant platforms at scale [13,14]. This automation substantially increases downstream exposure to card-not-present (CNP) fraud and undermines static and rule-based fraud detection systems. Compounding the threat, compromised accounts are often resold across cybercrime forums, creating an underground economy where user profiles have monetary value depending on their transaction history and geographic region.

From a prevention perspective, multi-factor authentication (MFA), behavioral biometrics, and anomaly detection algorithms have been proposed to counteract ATO. However, adoption remains uneven, and sophisticated attackers have found ways to bypass one-time passwords (OTPs) or exploit weak biometric implementations. This highlights the necessity of multi-layered defenses that combine technical measures (such as device fingerprinting and continuous authentication) with behavioral analytics (including user keystroke dynamics and login patterns) to effectively mitigate account takeover risks.

2.1.2 Phishing and Social Engineering Attacks

Phishing and social engineering attacks remain the most widely used techniques in facilitating CNP fraud because they exploit the human element rather than technical vulnerabilities. Fraudsters employ deceptive strategies to trick individuals into voluntarily disclosing sensitive payment details, login credentials, or personally identifiable information (PII). These attacks manifest in multiple forms, including email phishing, SMS-based phishing (smishing), voice calls (vishing), and increasingly through social media platforms that impersonate legitimate institutions [5,11]. In phishing scenarios, attackers construct counterfeit websites or mobile applications that closely resemble authentic merchant or banking portals. Victims, believing the interface to be genuine, input their card numbers, CVV or CVC, and authentication details, which are then harvested in real time and used for fraudulent purchases. The growing use of URL shortening services and domain obfuscation techniques further complicates the ability of users to distinguish fraudulent links from legitimate ones.

Smishing and vishing attacks have surged alongside the expansion of mobile banking and contactless payments. In these cases, fraudsters impersonate customer service agents or financial institutions, convincing victims to disclose verification codes or reset credentials. This is often coupled with real-time social engineering, where attackers initiate CNP transactions while simultaneously guiding the victim into providing the required one-time password (OTP) or biometric confirmation.

A particularly damaging variant is phishing for cryptocurrency wallets, where fraudulent QR codes or spoofed wallet applications redirect funds to attacker-controlled addresses. Unlike traditional chargeback-protected payments, cryptocurrency transactions are irreversible, magnifying consumer losses [8]. Detecting phishing attacks remains challenging because they often exploit legitimate communication channels. Traditional blacklist-based filtering is insufficient, as attackers continuously generate new domains and adaptive content. To address these limitations, researchers and practitioners have proposed machine learning classifiers that analyze email headers, message content, and embedded links for anomalies [15]. Additionally, visual similarity detection algorithms compare suspect websites against known brand templates, flagging fraudulent lookalikes [16].

Despite these advances, phishing attacks continue to succeed because they target cognitive biases such as trust, urgency, and curiosity. As a result, preventive measures must go beyond technological solutions and incorporate user education, awareness campaigns, and regulatory frameworks. For instance, strong customer authentication (SCA) under the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) directive mandates multi-factor verification in Europe, reducing the success of phishing-related CNP fraud.

2.1.3 Friendly Fraud (Chargeback Fraud)

Friendly fraud, often referred to as chargeback fraud, represents a paradoxical category of CNP fraud where the legitimate cardholder initiates fraudulent activity. Unlike identity theft or phishing attacks, which involve external actors, friendly fraud occurs when a genuine consumer disputes a legitimate transaction with the intent of reversing payment and retaining the purchased goods or services [9,17].

The mechanism is deceptively simple. After making a purchase, the cardholder contacts their issuing bank to claim that the transaction was unauthorized, the product was not delivered, or the service was unsatisfactory. Because consumer protection laws and card network regulations (such as Visa’s Zero Liability Policy) heavily favor customers in disputed transactions, merchants are often left to bear the financial loss. This dynamic makes friendly fraud one of the most costly and contentious types of CNP fraud, especially for small and medium-sized e-commerce merchants [11].

Unlike merchant error or true fraud, friendly fraud is difficult to detect at the point of transaction because it originates from an authentic payment method, a legitimate shipping address, and verified user credentials. The gray area between intentional and unintentional chargebacks compounds the challenge. Some consumers unknowingly commit friendly fraud when they fail to recognize a charge on their billing statement, forget about a purchase, or when multiple family members share the same account. Others, however, deliberately exploit chargeback policies as a risk-free way to obtain goods and services without paying.

From a prevention standpoint, friendly fraud requires a multi-pronged strategy.

• Enhanced transaction documentation, such as delivery confirmations, digital receipts, and geo-tagged proof of service, can strengthen a merchant’s defense during chargeback disputes [18].

• Chargeback alert systems, offered by payment processors, notify merchants in real time when disputes are filed, allowing them to issue refunds proactively and avoid fees.

• Machine learning–based behavioral analytics can flag suspicious refund or dispute patterns, such as repeat offenders or unusually high dispute rates from specific accounts [19].

At a regulatory level, initiatives such as PSD2’s strong customer authentication (SCA) aim to reduce disputes by requiring robust verification of each transaction. Similarly, card networks are refining dispute resolution processes by distinguishing between legitimate claims and abuse, though enforcement remains inconsistent across jurisdictions.

2.1.4 Synthetic Identity Fraud

Synthetic identity fraud is one of the fastest-growing and most insidious forms of CNP fraud because it combines elements of legitimate personal information with fictitious data to create a new, seemingly valid identity. Unlike traditional identity theft, where a fraudster assumes complete control of an existing profile, synthetic identity fraud constructs an entirely new persona that passes many conventional verification checks [13,20].

The process typically begins when fraudsters obtain fragments of personal information, such as Social Security numbers, national identification numbers, or dates of birth, through data breaches or dark web markets. These fragments are then fused with fabricated details, including false names, addresses, and phone numbers, to establish a synthetic identity. Over time, the fraudster may nurture the profile by applying for small lines of credit, paying bills on time, and building a positive transaction history. This “grooming” phase allows the synthetic identity to appear legitimate within financial systems [17].

Once established, synthetic identities are used to commit CNP fraud in several ways:

• Transaction Fraud: Fraudsters use synthetic profiles to open accounts and make purchases that are eventually defaulted on.

• Credit Bust-Outs: After gaining trust and higher credit limits, attackers suddenly maximize available credit and disappear without repayment.

• Merchant Exploitation: Fraudsters use synthetic identities to establish merchant accounts and launder fraudulent transactions under the guise of legitimate businesses.

The difficulty of detecting synthetic identities lies in their hybrid nature: part real and part fabricated. Fraud detection systems that rely heavily on deterministic checks (e.g., matching name, date of birth, or address) often fail to flag these accounts because the genuine elements validate the synthetic profile. Furthermore, the rise of digital onboarding processes in banking and e-commerce, where remote identity verification is common, has amplified vulnerability [12].

Advanced detection approaches are increasingly exploring graph-based analytics and linkage analysis. By mapping relationships across devices, addresses, emails, and transaction histories, these systems can identify anomalies in network structures that suggest fabricated identities [21,22]. Similarly, machine learning algorithms trained on behavioral patterns, rather than static identifiers, are being employed to differentiate between authentic and synthetic profiles.

Despite these innovations, synthetic identity fraud remains a significant regulatory challenge. Because victims are often not immediately aware, since their full identity is not directly stolen, it may take years before fraudulent activity is detected. This delayed recognition results in significant financial losses for issuers, acquirers, and merchants, while complicating liability assignment in cross-border transactions.

To mitigate this risk, industry experts recommend a layered defense that combines:

• Advanced Know Your Customer (KYC) checks with biometric verification,

• Device fingerprinting to link transactions to consistent hardware or network characteristics,

• Consortium data-sharing between banks and payment providers to identify overlapping suspicious patterns, and

• Regulatory frameworks, such as PSD2 and GDPR, which mandate stricter identity validation and data protection.

2.1.5 Botnet and Automated Attacks

Botnet and automated attacks have become the dominant enabler of large-scale CNP fraud due to their speed, scalability, and ability to overwhelm traditional fraud detection mechanisms. Unlike phishing or synthetic identity fraud, which rely on social or identity manipulation, botnet attacks exploit the automation of fraudulent transactions through networks of compromised devices [21]. These devices, ranging from personal computers to Internet of Things (IoT) endpoints, are infected with malware and remotely controlled by attackers to execute thousands of transaction attempts simultaneously.

A common manifestation of this threat is the card testing (or “carding”) attack, in which bots systematically attempt small transactions to validate stolen card details. If a transaction succeeds without being flagged, the card is marked as “live” and later used for higher-value purchases or sold on underground forums. Because these low-value tests often mimic legitimate consumer behavior, they are particularly challenging to detect in real-time [9].

Botnets are also central to credential stuffing attacks, where stolen username and password combinations are tested across multiple merchant sites to gain unauthorized access to customer accounts. Given the widespread reuse of credentials across platforms, these attacks frequently succeed, leading to account takeover (ATO) and downstream CNP fraud [23].

The rise of IoT-enabled botnets such as Mirai has further amplified the scale of attacks. Fraudsters can now mobilize millions of devices with minimal cost, creating distributed attack networks that evade IP-based detection methods. These IoT botnets often target weakly secured consumer devices such as routers, webcams, or smart home appliances, underscoring the growing convergence of cybersecurity and financial fraud [21].

Detecting botnet-driven fraud requires sophisticated behavioral analytics and velocity checks. For example:

• Transaction velocity monitoring identifies abnormal bursts of activity from single accounts, IPs, or devices.

• Device fingerprinting distinguishes legitimate users from bot-controlled scripts by tracking browser, hardware, and network attributes.

• Graph-based fraud detection models map relationships across IP addresses, devices, and transactions to uncover botnet patterns [21,22].

Despite these advances, challenges persist. Attackers increasingly employ human-in-the-loop botnets, where automated scripts handle the bulk of activities, but humans intervene during critical authentication steps (e.g., solving CAPTCHAs or providing stolen OTPs). This hybrid model blurs the distinction between machine-generated and genuine user behavior, raising false negatives in detection systems.

From a prevention perspective, multi-layered defenses are essential. Techniques such as reCAPTCHA challenges, rate limiting, behavioral biometrics, and federated learning approaches [16] can collectively reduce the impact of botnets. Moreover, cross-industry collaboration to share threat intelligence is critical for identifying evolving attack signatures across ecosystems.

2.1.6 Merchant-Side Attacks and Data Breaches

Merchant-side attacks and data breaches represent another critical source of CNP fraud, as they directly compromise the infrastructure that processes and stores sensitive payment data. Unlike phishing or botnet attacks that target consumers, merchant-side breaches exploit vulnerabilities in payment gateways, e-commerce platforms, and third-party service providers. Once attackers infiltrate these systems, they can exfiltrate large volumes of cardholder data, including Primary Account Numbers (PANs), CVV codes, billing addresses, and even authentication tokens, which are subsequently monetized on black markets or reused for fraudulent transactions [23].

A defining characteristic of merchant-side attacks is their scale and systemic impact. High-profile breaches, such as those affecting global retailers and payment processors, have resulted in the exposure of millions of card records at once. This not only amplifies the risk of downstream CNP fraud but also erodes consumer trust in digital commerce and leads to significant reputational and financial losses for affected organizations [9].

Common attack vectors include:

• SQL injection and web application exploits that allow unauthorized database access.

• API vulnerabilities, particularly in poorly secured mobile and e-commerce integrations, where weak authentication or misconfigured permissions expose payment data.

• Malware injections, such as form-jacking scripts (Magecart attacks), which intercept card details entered on checkout pages in real time.

• Insider threats, where employees or contractors abuse privileged access to extract or sell sensitive data.

Detecting and mitigating merchant-side attacks is particularly challenging due to the distributed and outsourced nature of modern payment ecosystems. Merchants often rely on third-party providers for payment processing, cloud hosting, and analytics, which increases the attack surface and complicates accountability [5]. Furthermore, compliance frameworks such as the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) establish minimum requirements for data security; however, enforcement is inconsistent across regions and merchant categories.

Recent approaches to prevention emphasize tokenization and end-to-end encryption (E2EE). By replacing sensitive card details with randomly generated tokens, merchants reduce the risk of storing exploitable data. Similarly, encryption ensures that cardholder data is unreadable even if intercepted. Some frameworks also employ real-time intrusion detection systems (IDS) and anomaly-based monitoring to detect unusual activity within merchant networks.

At a strategic level, blockchain-based antifraud frameworks have been proposed to decentralize transaction validation and reduce reliance on centralized merchant databases [18]. Additionally, regulatory regimes such as GDPR and PSD2 impose stricter requirements on data handling and customer authentication, providing legal incentives for merchants to strengthen security practices.

Triangulation fraud is a sophisticated form of CNP fraud that exploits both legitimate merchants and unsuspecting consumers through a three-party deception model. In this scheme, the fraudster operates a fake online storefront that advertises popular goods at unusually low prices to lure unsuspecting customers. When a purchase is made, the fraudster uses stolen credit card details to place an identical order with a legitimate merchant, directing the shipment to the original buyer. The consumer receives the goods, believing the transaction to be genuine, while the fraudster retains the customer’s personal and payment information for future exploitation [18].

This type of fraud is particularly deceptive because all three parties appear to engage in legitimate behavior:

• The consumer willingly purchases items online.

• The legitimate merchant processes a valid payment authorization and fulfills the order.

• The fraudster successfully masks their role by inserting themselves between the two.

The fraudster profits in two ways: first, by harvesting and reselling the consumer’s card details and personal information; second, by building credibility for their fake storefront through successful deliveries, which enables them to scale future fraudulent operations.

Triangulation fraud poses unique detection challenges. Since the goods are shipped to the correct consumer, the merchant is initially unaware of any fraud, and the customer may not suspect wrongdoing until they discover unauthorized charges or are later targeted by further fraudulent activities. Additionally, because transactions at the merchant level appear legitimate, traditional fraud detection models, focused on transaction anomalies, may fail to detect the scheme in real time [9].

Preventive measures require interventions at multiple levels:

• Consumer education is critical, as many victims are drawn to unrealistic discounts or unfamiliar sellers. Raising awareness about secure shopping practices, such as verifying vendor legitimacy, checking Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTPS) protocols, and avoiding suspiciously low prices, can reduce susceptibility.

• Merchant monitoring can help by flagging multiple transactions linked to the same device, IP address, or delivery address but involving different credit cards, which may indicate triangulation patterns.

• Network-level intelligence sharing among merchants, card networks, and banks can identify coordinated fraud campaigns by correlating suspicious activities across different platforms.

Advanced detection frameworks increasingly rely on graph analytics to uncover hidden relationships between fraudulent storefronts, compromised cards, and consumer identities [21,22]. By analyzing transaction networks, these systems can identify clusters of activity consistent with triangulation fraud, even when individual transactions appear normal.

2.1.8 Cross-Border and Multi-Channel Fraud

Cross-border and multi-channel fraud represent complex and rapidly expanding dimensions of CNP fraud that exploit regulatory fragmentation, jurisdictional inconsistencies, and technological diversity across global payment systems. With the rapid growth of e-commerce and international digital trade, transactions are increasingly flowing across borders, often involving multiple intermediaries, such as payment processors, acquiring banks, and card networks. This interconnected environment provides fertile ground for fraudsters to exploit gaps in fraud detection, varying compliance standards, and delays in cross-jurisdictional coordination [9,17].

In cross-border CNP fraud, attackers often exploit weaker fraud prevention systems in specific regions. For example, markets with less stringent enforcement of Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) standards or limited adoption of strong customer authentication (SCA) are particularly vulnerable. Fraudsters may route transactions through these jurisdictions to bypass stricter controls in others, creating a form of regulatory arbitrage. Additionally, global merchants often struggle to strike a balance between fraud prevention and customer experience, making them reluctant to impose strict security checks that could deter international customers.

Multi-channel fraud occurs when attackers leverage multiple platforms, such as websites, mobile applications, call centers, and social media marketplaces, to execute fraudulent transactions. By spreading activity across diverse channels, fraudsters reduce the likelihood of being detected by systems that focus on single-channel monitoring. For instance, a fraudster might test stolen credentials through automated scripts on a mobile app, use the same details for high-value purchases on a website, and later confirm delivery through a call center. This fragmented footprint makes it harder for merchants and financial institutions to correlate suspicious behavior.

Detection of cross-border and multi-channel fraud is challenging for several reasons:

• Data localization laws often restrict the sharing of transaction data across borders, limiting the ability of banks and merchants to build a complete fraud profile.

• Inconsistent fraud monitoring tools across different channels (e.g., weaker fraud filters on mobile apps vs. websites) create vulnerabilities that fraudsters exploit.

• High transaction velocity in global e-commerce complicates real-time risk scoring, particularly when payments involve currency conversion or multi-party settlement.

To counter these threats, researchers and practitioners have proposed multi-layered solutions:

• Global fraud intelligence sharing networks, such as consortium-based data lakes, enable institutions to correlate suspicious activity across borders and channels [23].

• Adaptive risk scoring models use contextual data, such as geolocation, device fingerprinting, and merchant category, to assess cross-border transactions more accurately.

• Federated learning approaches [16,24] allow institutions to collaboratively train fraud detection models without directly sharing sensitive customer data, thereby addressing privacy and compliance concerns.

From a regulatory perspective, harmonizing global standards remains a key challenge. While initiatives such as PSD2 in Europe and PCI DSS globally provide baseline requirements, inconsistencies persist across regions, especially in developing markets. Strengthening international cooperation between regulators, financial institutions, and merchants is therefore essential to reducing the vulnerabilities inherent in cross-border and multi-channel payment systems.

2.1.9 Emerging Threats: IoT and Digital Wallet Exploits

Emerging threats in CNP fraud increasingly stem from the convergence of payments with the Internet of Things (IoT) and the proliferation of digital wallets in mobile ecosystems. These innovations, while enhancing convenience and enabling new business models, have introduced novel vulnerabilities that fraudsters are actively exploiting [21,25].

IoT devices such as smart home assistants, connected vehicles, and wearable payment devices often lack the robust security architectures of traditional computing systems. Many operate with limited processing power, minimal encryption, and inconsistent patching cycles, making them attractive targets for fraudsters. Once compromised, IoT devices can be co-opted into botnets to conduct large-scale automated fraud, or manipulated to intercept transaction requests and relay fraudulent payment instructions. For example, compromised smart meters and point-of-sale IoT terminals have been documented as entry points for broader payment fraud campaigns [21].

Digital wallets, including platforms such as Apple Pay, Google Pay, and Alipay, introduce their own fraud vectors. While these systems rely on tokenization and biometric authentication to secure transactions, attackers have discovered ways to bypass protections. Weaknesses in device fingerprinting, poorly implemented biometric checks, and vulnerabilities in token provisioning have enabled fraudsters to hijack wallet accounts or inject fraudulent tokens. Moreover, Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) swap attacks, where fraudsters gain control of a victim’s mobile number, allow them to reset wallet credentials and bypass multi-factor authentication safeguards.

Another emerging concern is the rise of contactless payment exploitation. Fraudsters can use near-field communication (NFC) skimming devices to capture wallet data from unsuspecting users in crowded environments. Although such attacks typically require physical proximity, they highlight the evolving tactics of criminals seeking to exploit the expanding mobile-first payment landscape.

Detecting IoT and digital wallet fraud requires advanced, context-aware analytics. Transaction monitoring systems must integrate device-level signals, such as firmware version, operating environment, and biometric verification logs, into real-time risk assessments. Emerging frameworks propose the use of graph neural networks (GNNs) to model relationships among users, devices, and transactions, thereby identifying anomalies that suggest fraud [21,22]. Similarly, federated learning approaches have been applied to detect wallet fraud without exposing sensitive biometric data, thereby preserving user privacy [16].

From a governance standpoint, regulators are beginning to address these emerging risks. For instance, the European Central Bank’s PSD2 mandate has expanded strong customer authentication requirements to include mobile wallets, while the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has issued guidelines for IoT device manufacturers to incorporate security-by-design principles. However, enforcement remains fragmented, and many IoT payment devices continue to operate with insufficient safeguards.

3.1 Overview and Research Design

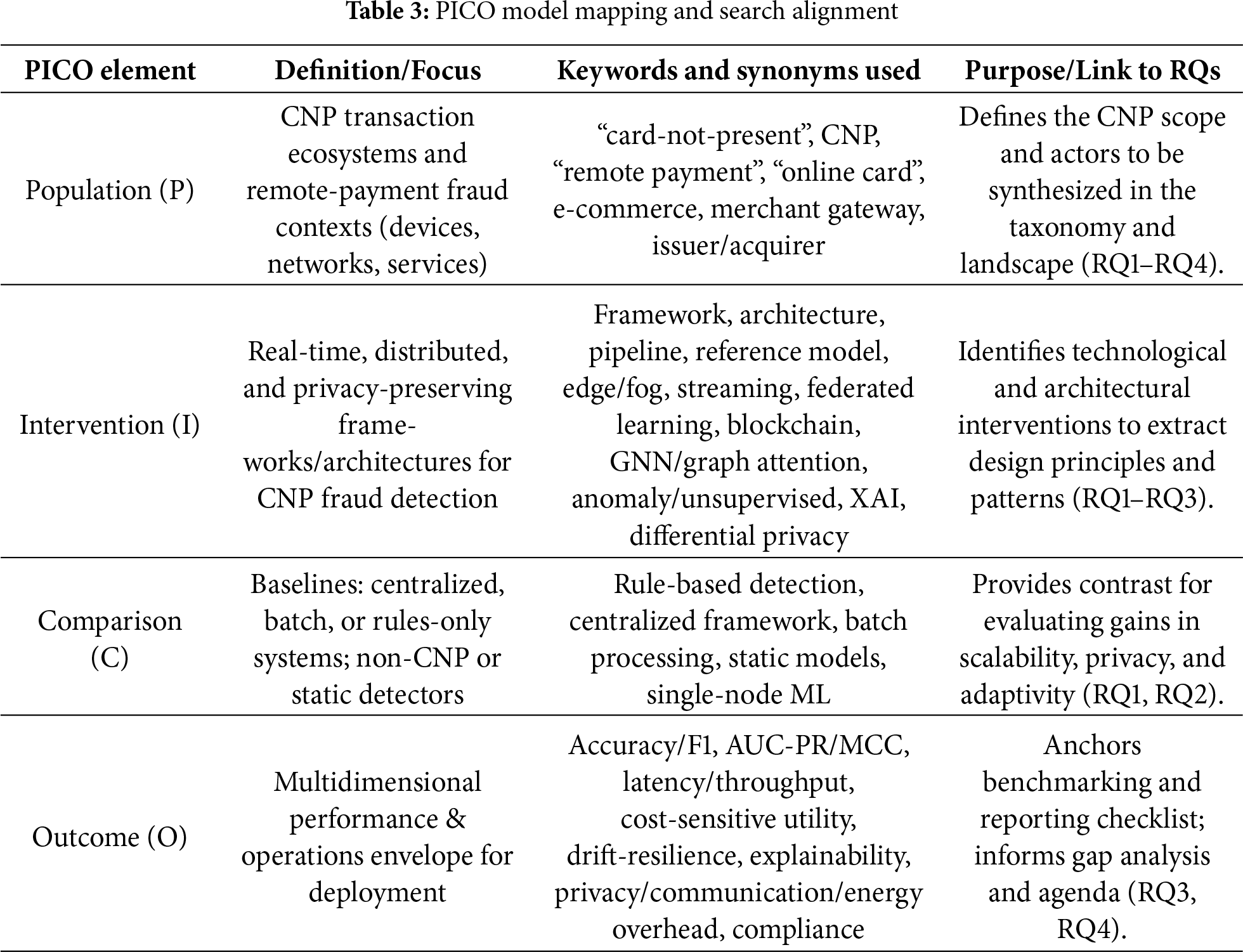

The review follows PRISMA 2020 [26] guidelines to ensure thoroughness and transparency. It adopts a (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) PICO model [27]—informed scope, focusing on CNP frameworks and their associated deployment outcomes. The workflow integrates qualitative thematic analysis with quantitative benchmarking, ensuring that the findings align with the research objectives and are organized into seven key stages:

1. Scope and Protocol: Research questions and objectives are aligned, with predefined criteria and screening rules, acknowledging potential risks such as publication bias and metric heterogeneity.

2. Search and Screening: Search academic databases, remove duplicates, and review titles and texts with a PRISMA flow diagram.

3. Eligibility and quality assessment: Assess eligibility and quality with a standardized evaluation checklist.

4. Data Extraction and Thematic Coding: Systematically extract data and apply thematic coding aligned with research questions.

5. Synthesis and Benchmarking: Develop a multi-layer taxonomy and actionable design principles through cross-study coding.

6. Integration & Agenda: Integrate findings to establish a prioritized research agenda based on evidence-to-gap mapping.

To achieve the objectives of the review, each objective was reformulated into a guiding research question to enhance data collection, analysis, and synthesis. Table 2 presents a precise alignment of the study’s objectives with the corresponding guiding research questions, analytical focus, and anticipated outcomes. This mapping operationalizes the review protocol, linking PRISMA-guided evidence collection and coding to a specific deliverable. Furthermore, this approach ensures methodological coherence throughout the paper.

3.3 Search Strategy and Query Construction

The literature search was conducted using the PICO model to ensure a systematic and reproducible approach. Results are organized in Table 3 to enable targeted retrieval and consistent linkage to the study’s research questions (RQ1–RQ4).

Search string used: (“card-not-present” OR “card not present” OR CNP OR “remote payment” OR “e-commerce” OR “online card”) AND (fraud OR “fraud detection” OR “fraud prevention” OR “fraud mitigation” OR anomaly) AND (framework OR architecture OR pipeline OR “reference model”) AND (“real-time” OR streaming OR “near real-time”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “graph neural network” OR GNN OR “federated learning” OR blockchain OR “explainable AI” OR XAI OR “differential privacy”)

Databases Searched

Searches covered major scholarly databases to ensure comprehensive coverage across computer science, cybersecurity, and fintech:

• IEEE Xplore: Rich source for real-time systems, edge/streaming, and security frameworks.

• ACM Digital Library: Strong on software architecture, graph analytics, and deployment studies.

• ScienceDirect (Elsevier): Broad journals on data mining, information systems, and payments.

• Scopus: Multidisciplinary index used for citation chaining and coverage checks.

• MDPI: Open-access venues with recent work on FL/blockchain/privacy in fraud detection.

• Google Scholar: Supplementary recall and gray literature discovery (filtered to peer-reviewed sources).

To minimize bias, database-specific field tags (e.g., TITLE-ABS-KEY) were used where available, and backward/forward citation chaining captured foundational and emerging works.

3.4 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Clear inclusion criteria were defined for studies on CNP fraud-detection frameworks with an emphasis on real-time/near-real-time operation across device, network, and platform layers. A study was included only if all criteria were satisfied:

1. Publication type: Peer-reviewed research (journal articles and full conference papers).

2. Publication window: 2014–2025.

3. Language: English only.

4. Topical focus: CNP/online card-payment fraud detection or prevention framed as a framework/architecture/pipeline (end-to-end or subsystem intended for integration).

5. Operational capability: Demonstrates real-time or near-real-time detection/decisioning (e.g., streaming, low-latency edge/fog/cloud).

6. Evaluation relevance: Reports effectiveness using performance metrics (beyond accuracy where available) and describes data/protocols (e.g., temporal/entity splits, latency/throughput, cost/privacy/comms overhead).

Notes: Studies centered on distributed/privacy-preserving intelligence (e.g., federated learning, blockchain governance, graph-based detection) were included when explicitly applied to CNP contexts or readily generalizable to CNP pipelines.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if any of the following applied:

1. Out of scope (technology/context): Not CNP-focused (e.g., card-present/POS only) or general IoT/security work without a payment-fraud application.

2. Not fraud-focused: Financial/fintech studies lacking a fraud-detection/prevention component or lacking a framework/architecture context (point algorithms only).

3. No real-time aspect: Offline/forensic analyses without real-time or near-real-time claims; purely retrospective analytics with no latency considerations.

4. Non-peer-reviewed/grey literature: White papers, blogs, theses/dissertations, extended abstracts/short papers (<3 pages), or preprints without peer-reviewed versions.

5. Language: Non-English publications without an official English translation.

6. Duplicates/versions: Redundant versions of the same study; retained the most comprehensive and most recent peer-reviewed version.

Screening practice: Title/abstract and full-text screening were conducted against these criteria; disagreements were resolved by consensus, and the PRISMA flow recorded exclusions with reasons.

The Screening Process

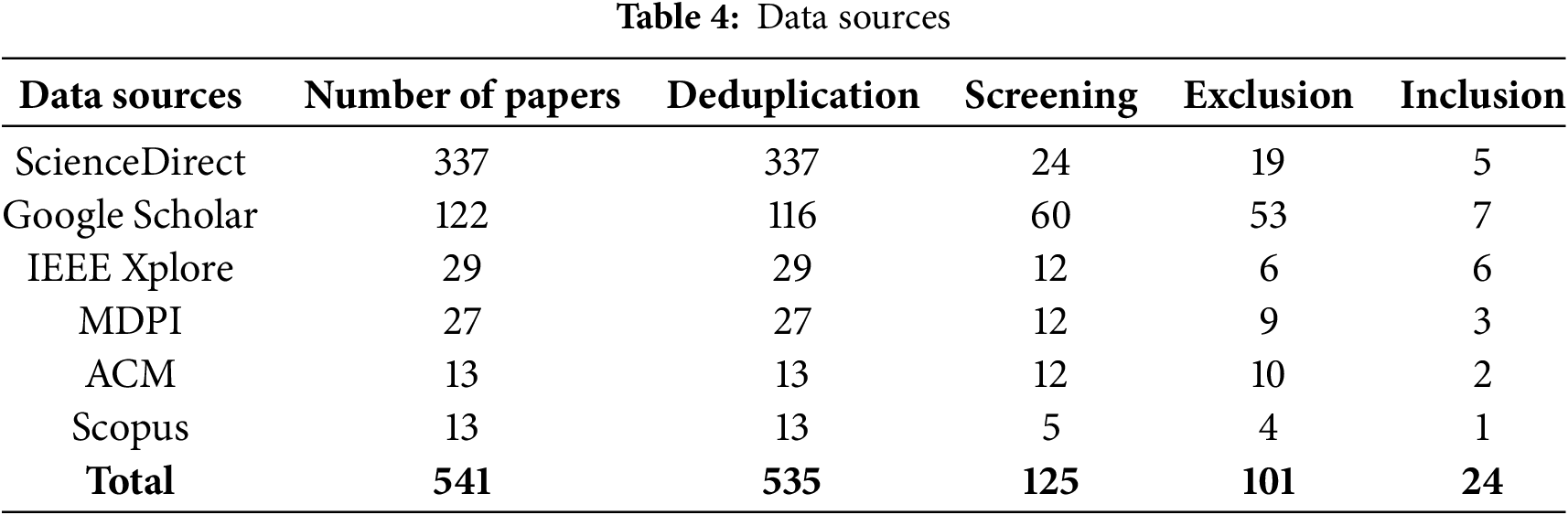

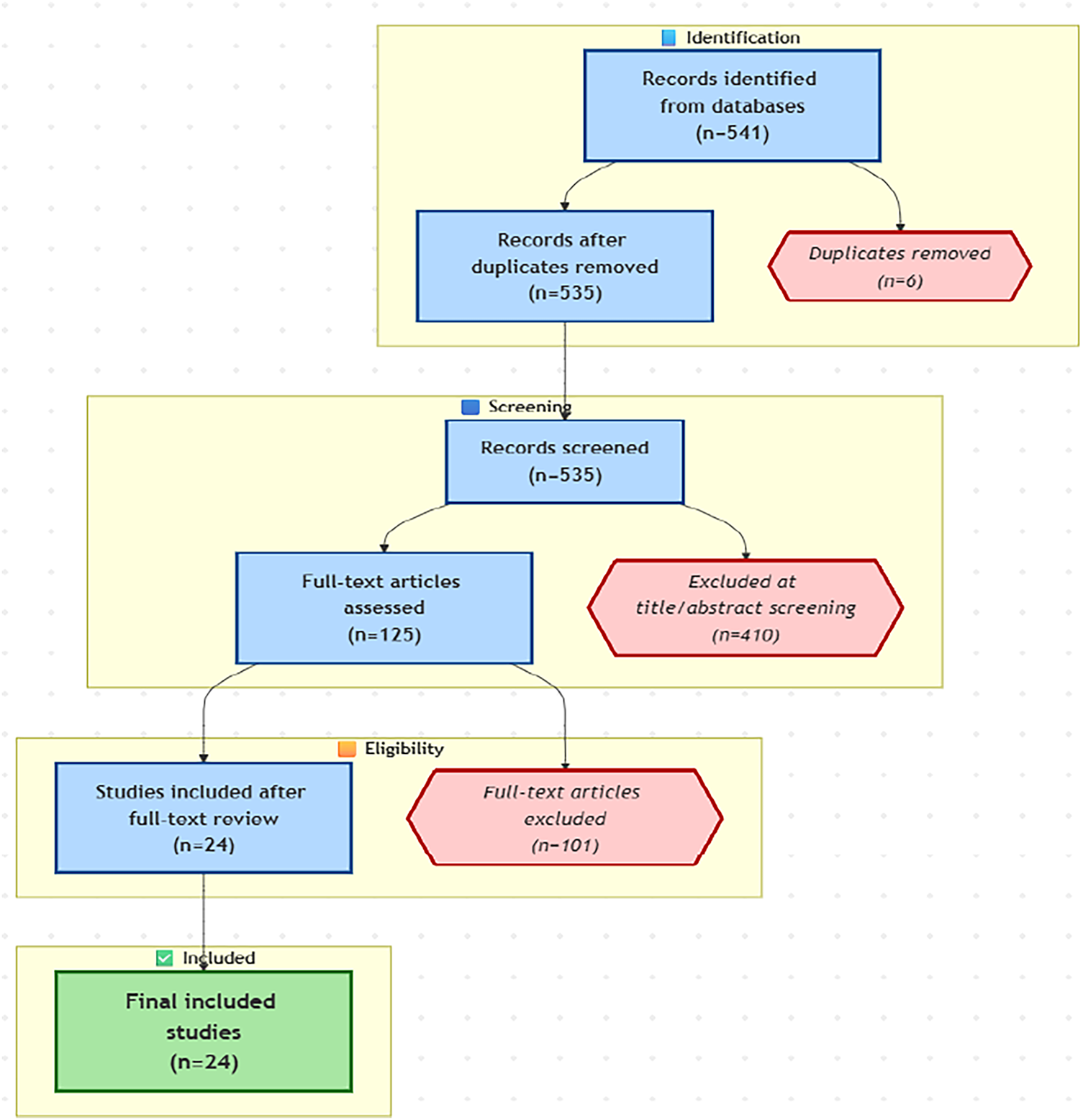

The screening process adhered to a four-phase PRISMA procedure. In the identification phase, a total of 541 records were retrieved from various sources. The Zotero reference management tool was subsequently employed to remove duplicate entries, refining the selection to 535 unique studies. In the title and abstract screening phase, 411 records were excluded based on predefined eligibility criteria, leaving 125 studies for full-text assessment. During the quality appraisal phase (full-text review), comprehensive quality assessments resulted in the exclusion of 101 records, thereby including 24 studies in the final review. Data sources are summarized in Table 4, and the workflow is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Prisma flow diagram

Each included study was appraised using a five-criterion checklist:

1. Clear articulation of research objectives.

2. Sound, reproducible methodology.

3. Valid evaluation metrics and credible experimental results.

4. Explicit CNP or applicable to CNP context for card-fraud detection.

5. Stated future work related to CNP fraud detection.

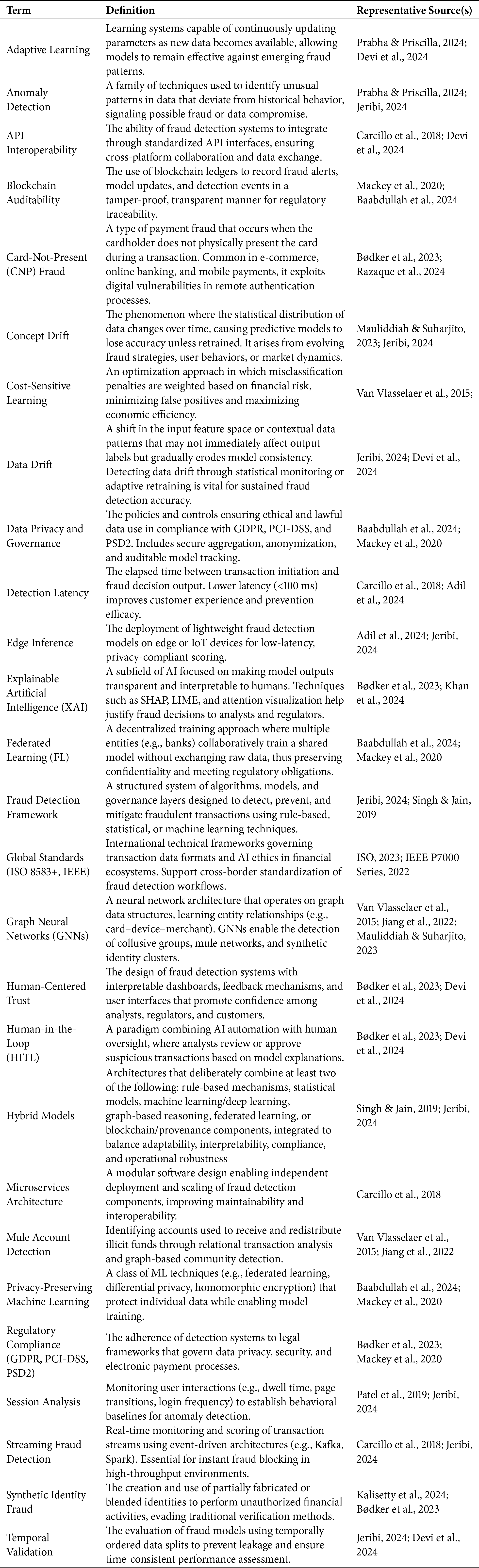

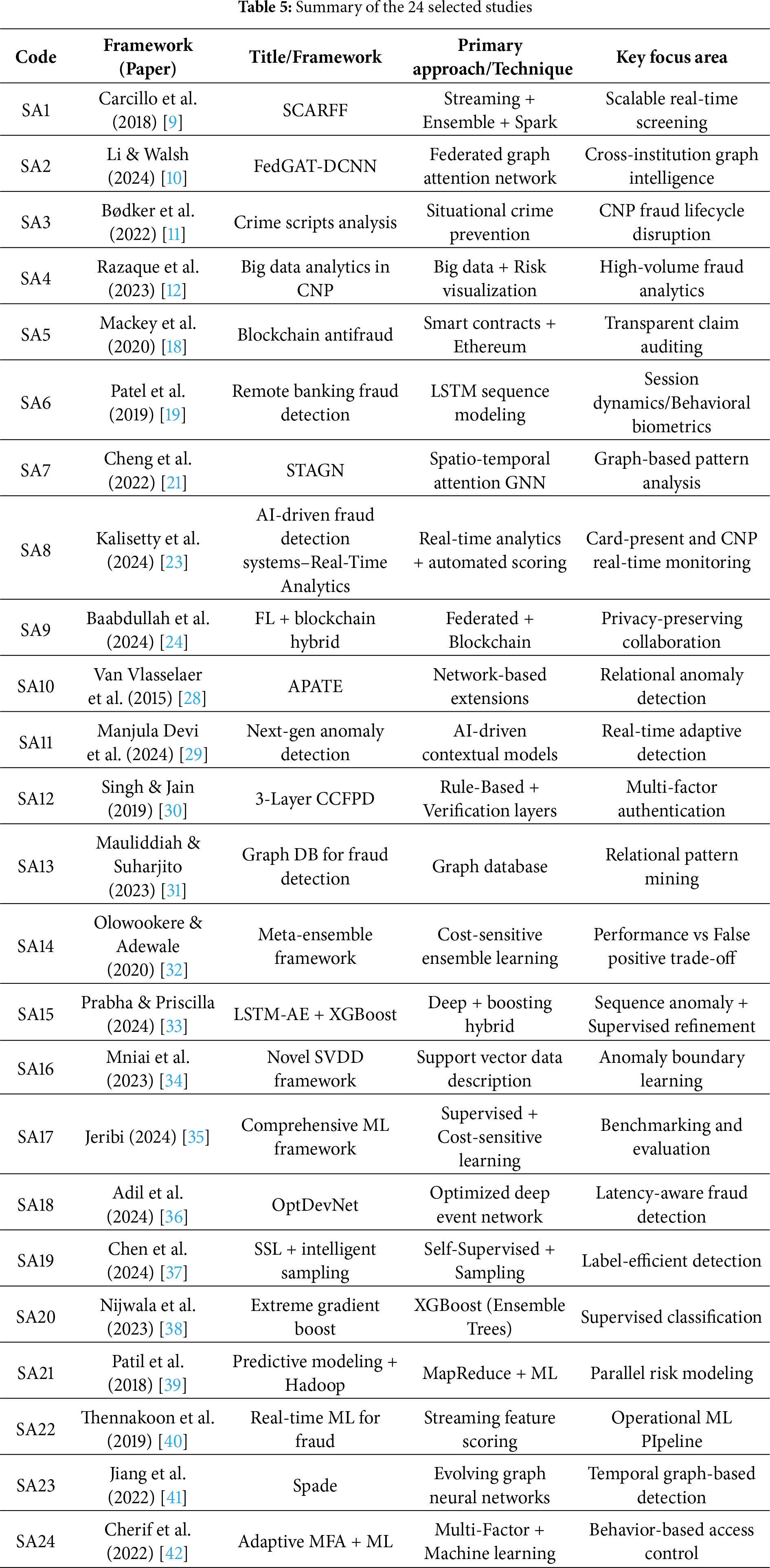

A binary scale was applied (1 = “yes,” 0 = “no”), enabling weighted synthesis by study quality. Only papers that met the quality thresholds were included in the final analysis. Table 5 summarizes the assessed studies, coded from Study Article 1 (SA1) to Study Article 24 (SA24).

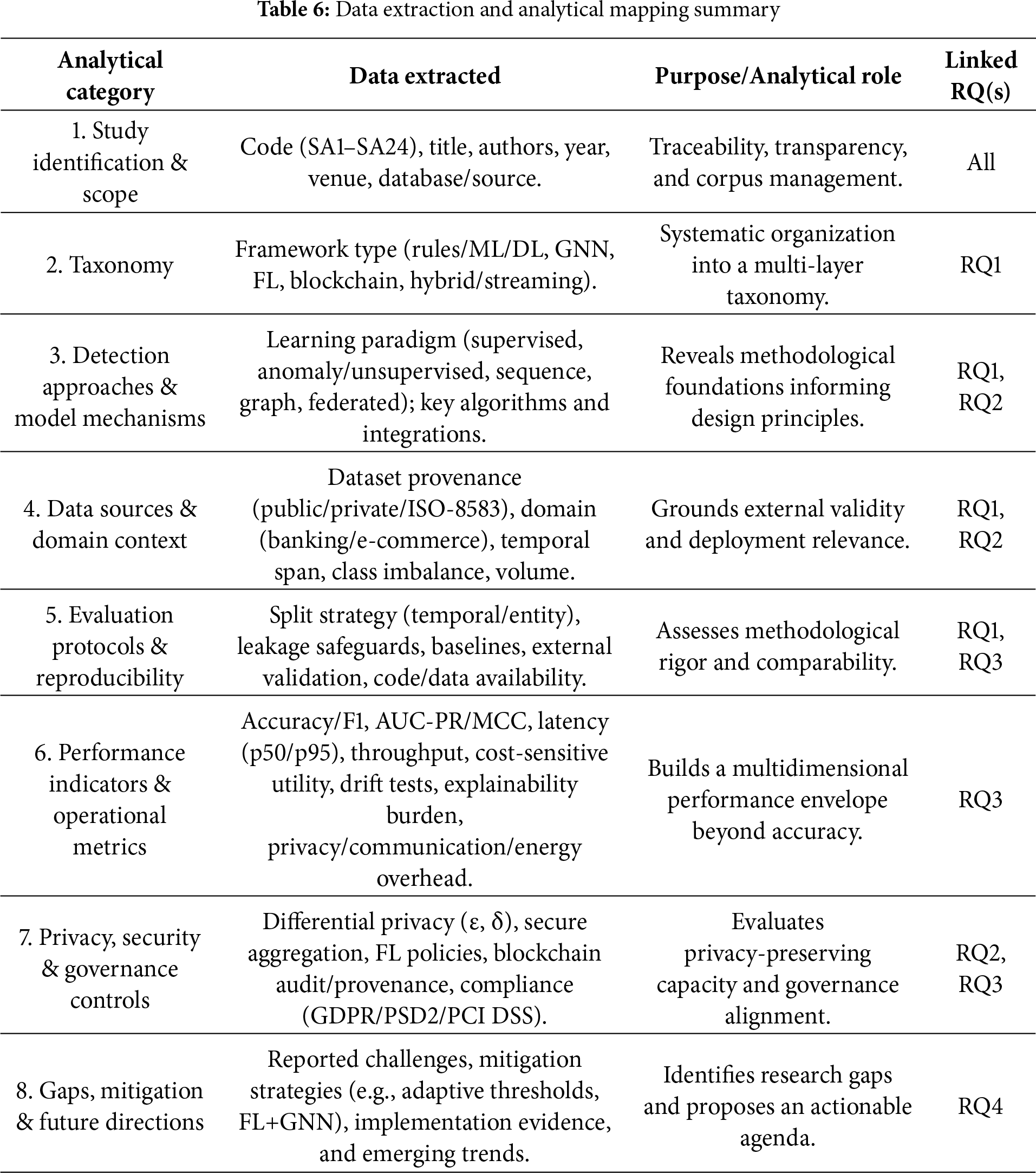

3.6 Data Extraction and Coding

Table 6 presents the structured data extraction and analytical mapping framework employed in this systematic review. Each record was coded across eight analytical categories, ranging from framework taxonomy and architectural layering to performance evaluation, governance controls, and emerging research directions. These categories were deliberately aligned with the study’s objectives and research questions to facilitate a coherent synthesis that connects conceptual organization, technical design, empirical benchmarking, and future research pathways within the CNP-fraud detection domain.

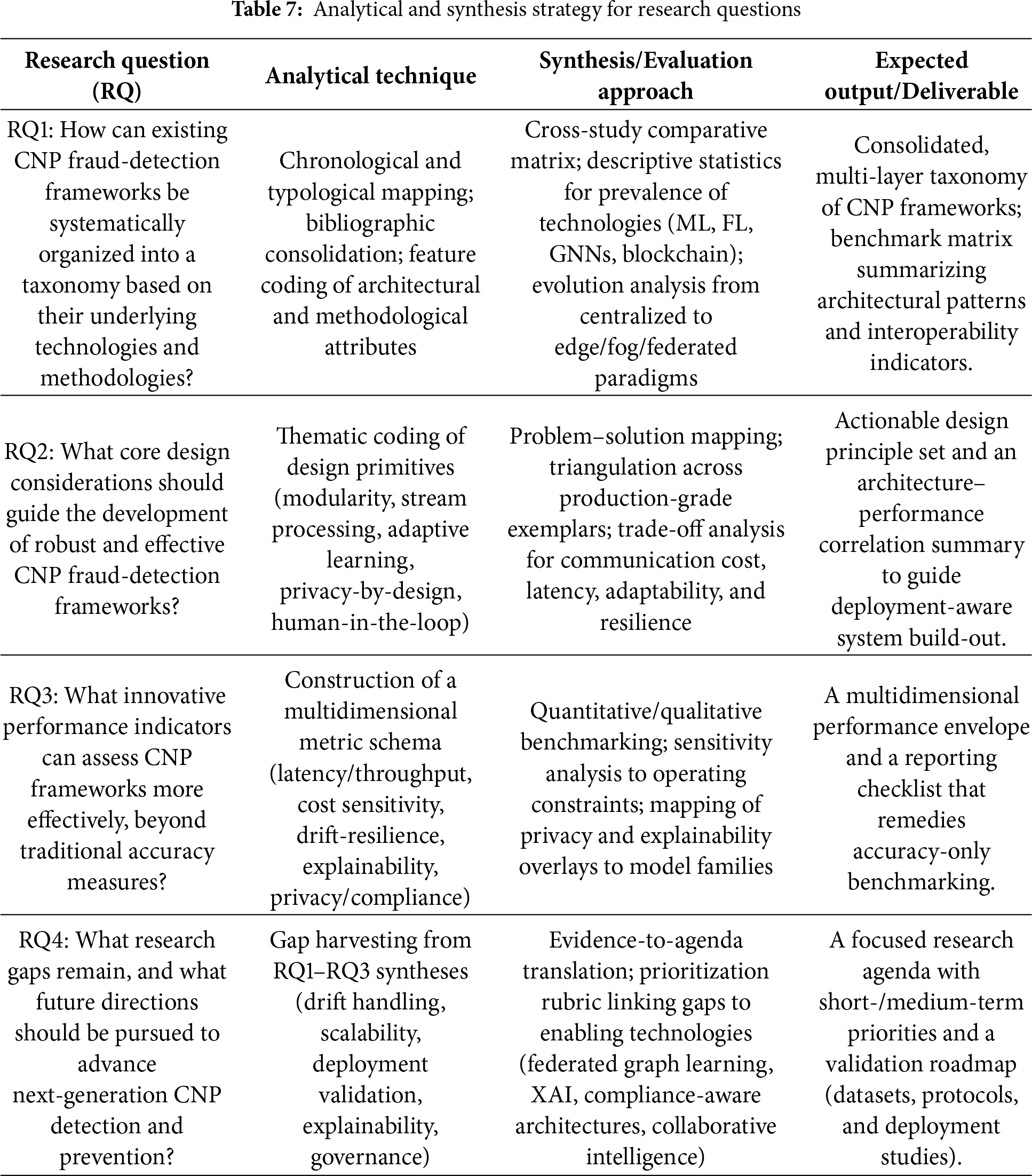

3.7 Analytical and Synthesis Strategy

Table 7 maps each research question to its corresponding analytical technique, synthesis/evaluation approach, and expected deliverable. This alignment provides a transparent line of sight from objectives to methods and outputs, ensuring that evidence collection and analysis are systematically organized and deployment-oriented. The structure also facilitates replication and focused interpretation of results across RQ1–RQ4.

3.8 Thematic Grouping of CNP Fraud Detection Frameworks

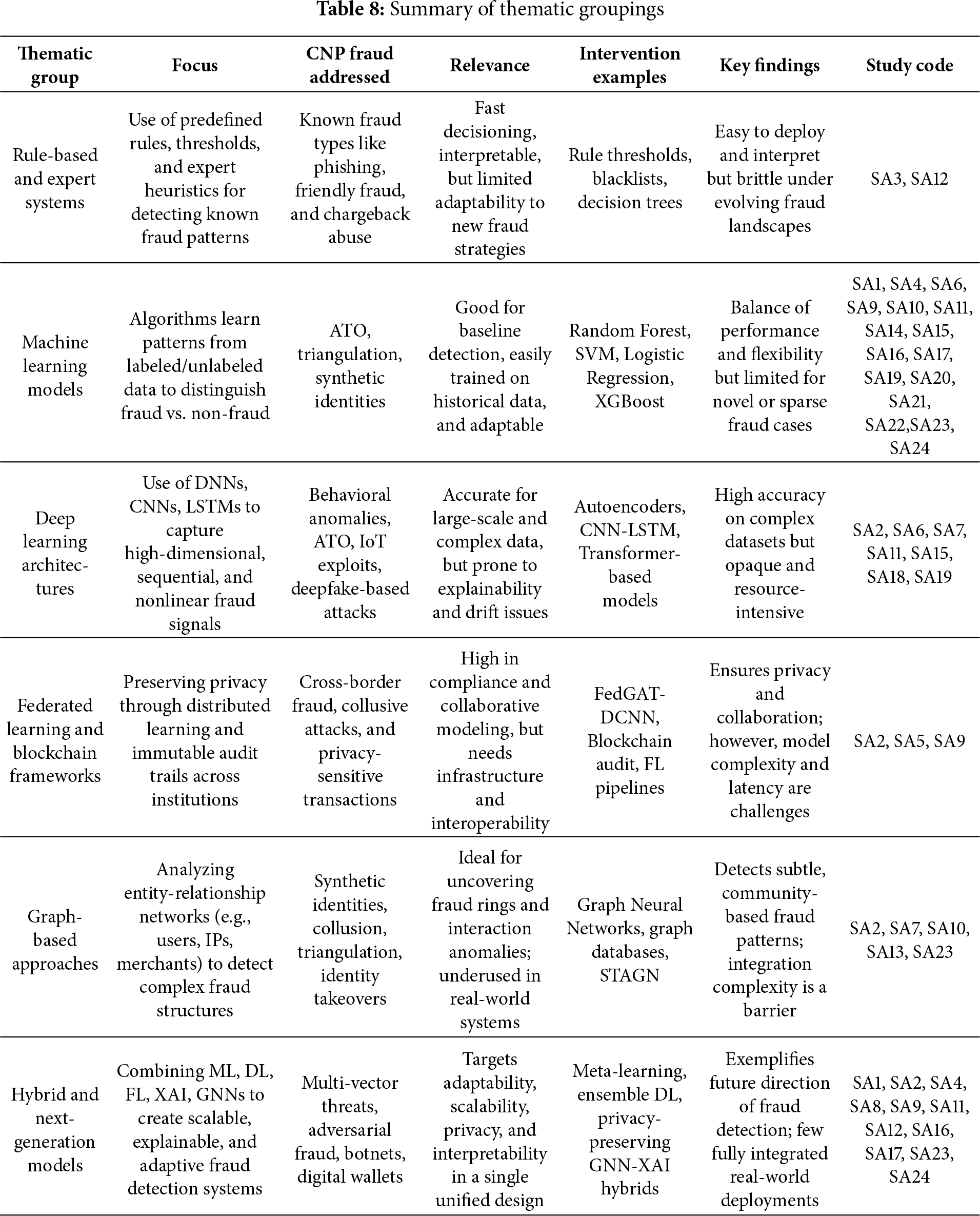

Following a comprehensive analysis of the frameworks, six major thematic categories were delineated: (i) Rule-Based/Expert Systems, (ii) Machine Learning, (iii) Deep Learning, (iv) Federated Learning & Blockchain, (v) Graph-Based, and (vi) Hybrid/Next-Generation. Each group reflects a unique theory of inference while highlighting key operational considerations for CNP fraud, as summarized in Table 8. This typology serves two primary purposes. First, it enables meaningful comparisons across diverse artifacts by applying ordinary analytical lenses focused on contribution, methods, CNP threat coverage, and notable findings. Second, it reveals trends in the field, illustrating a shift from isolated, rule-based detectors to integrated systems that are graph-aware and privacy-preserving, operating in real time across institutions. As contemporary systems often integrate multiple paradigms, this taxonomy is intentionally non-exhaustive, allowing for multi-label membership to facilitate practical applicability. By framing the literature through this lens, it reduces construct variability, clarifies design trade-offs, and connects methodological innovation with practical deployment.

Rule-Based and Expert Systems

Rule-based and expert systems are among the earliest and most transparent types of fraud detection architectures, operating through manually defined rules, thresholds, decision trees, and blacklists often created by fraud analysts or domain experts. Their primary advantage lies in their interpretability; each decision can be traced back to a specific rule, making them highly suitable for use in legacy banking infrastructures, regulatory audits, and internal fraud compliance checks. Additionally, they are fast, easy to maintain in static environments, and cost-effective for organizations with limited data science resources.

However, these systems face significant limitations, such as poor adaptability, as they are static by nature and require frequent manual updates to stay relevant to evolving fraud patterns. They are also vulnerable to zero-day fraud scenarios. They cannot learn from new data unless explicitly programmed to do so, with their reliance on known fraud signatures leaving considerable gaps in their ability to detect new or sophisticated attack vectors.

Key Insight: While no longer sufficient as standalone engines, remain important as foundational filters in today’s cybersecurity landscape. When integrated into multi-layered frameworks, they enhance early threat identification and provide valuable insights, complementing machine learning and AI-driven fraud detection methods. This combination is essential for a comprehensive security strategy against evolving threats.

Case Study: Crime-Script Deployment Lens for Targeted CNP Disruption [11]

A regional e-commerce marketplace used a crime-script framework to map the lifecycle of CNP attacks, which included stages such as offender preparation (data sourcing and mule onboarding), pre-transaction probing (test charges), checkout execution (using stolen credentials), and post-authorization monetization (refund abuse and chargebacks). This mapping produced a structured graph outlining offenders’ goals, resources, decisions, and contingencies, which the risk management team translated into specific disruption points for intervention.

Upstream controls were implemented to mitigate risks during account creation and device priming, including measures such as device fingerprinting, IP/ASN risk assessments, suppression of disposable email addresses, and KYC step-ups for high-risk regions. Midstream controls focused on the checkout process, employing geo-consistency checks for addresses, velocity thresholds for transactions, and caps on high-risk Merchant Category Codes (MCCs). Downstream controls targeted monetization risks by throttling refunds and returns and utilizing heuristics to address repeated disputes.

The operationalization process involved three phases. First, a policy matrix was created to link script nodes (e.g., “credential testing”) to specific rules and triggers. Second, these controls were integrated into business processes, with onboarding flows incorporating identity checks and checkout processes activating real-time gating mechanisms. Third, a governance structure facilitated measurement and adaptation by tracking key performance indicators (KPIs) linked to disruption points, such as test-charge prevalence and refund-to-sales ratios. Within eight weeks, the marketplace achieved a 43% reduction in credential-testing attempts, a 31% decrease in triangulated checkout activities, and a 22% drop in losses from refund abuse, with only a minor decline of 0.2 percentage points in approval rates. The use of a script-indexed queue also improved investigation times by 15%.

Overall, the crime-script approach clarified the strategic placement of controls, transforming the program from a broad strategy to precise, stage-specific interventions that combined prevention and detection across onboarding, checkout, and post-authorization processes.

Machine Learning Models

Machine learning (ML) frameworks signify a notable advancement over static rule-based systems in the realm of fraud detection. Unlike their static predecessors, these models leverage historical data to learn patterns, distinguishing between fraudulent and legitimate transactions through techniques such as statistical learning, classification, and pattern recognition. Key ML approaches, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and XGBoost, have been extensively investigated in the context of card-not-present (CNP) fraud. One of the primary advantages of ML models is their ability to automate large-scale fraud detection, enabling adaptability to evolving fraud trends as additional data is collected. They provide a necessary equilibrium between performance and interpretability, particularly within traditional banking environments where decisions require both defensibility and adaptability. Typically, these models serve as the foundational layer in real-time fraud scoring systems and can undergo frequent retraining to respond to data drift over time.

Despite these strengths, machine learning models have inherent limitations; their efficacy is often compromised by data imbalance, a common issue in fraud datasets where legitimate transactions vastly outnumber fraudulent ones. Furthermore, these models may encounter challenges with concept drift, necessitating regular retraining. Lastly, many conventional ML models exhibit a lack of transparency, complicating the justification of individual decisions without the support of additional explainability tools.

Key Insight: ML-based frameworks provide a strong foundation for fraud detection pipelines, especially when combined with feature engineering, feedback loops, and adaptive thresholding. While not as advanced as deep or graph-based models, they remain crucial in low-latency, data-rich, and risk-sensitive environments, effectively addressing fraudulent activities in real-time.

Case Study: Operational, Streaming Machine Learning for Real-Time CNP Fraud Control [39]

A mid-sized payment gateway has developed an online fraud-scoring pipeline for card-not-present (CNP) authorizations, handling 600 to 800 transactions per second within 30 to 50 ms. The architecture features several key stages:

– The ISO-8583 ingest and parsing stage (≤3 ms) sends MTI 0100/0200 messages to Kafka.

– A co-located feature service (≤6 ms) provides real-time data, including recent outcomes, velocity counters, and failed CVC attempts, with a 99th percentile staleness of under 10 s.

– An online model (≤7 ms) scores transactions after a 1 ms filter for mismatches and risky combinations.

– A policy engine executes actions (approve, step-up, or decline) within ≤5 ms, with a shadow model for safe evaluations and hourly updates.

Operational guidelines ensure data accuracy and prevent leaks. Time-based splits are used for training and validation, with latency goals of 10 ms for the median, 20 ms for 95% of cases, and 30 ms for 99% of cases. Key metrics are monitored, and alerts are triggered when thresholds are crossed. Around 700 transactions are processed per second, with a median scoring under 25 ms. The F1 score improved by 2.8 points, and false negatives decreased by 21%, while maintaining approval rate impact within ±0.3 points. Online updates restored normal false negatives in 36 h during peak traffic, and simple explanations reduced analyst review time by 18%. This case shows the shift in CNP detection from retrospective analysis to real-time risk management.

Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning (DL) has become a powerful technique for detecting credit card non-payment (CNP) fraud by utilizing neural networks to model complex, non-linear patterns in large-scale transactional data. These architectures excel at extracting hidden representations, modeling temporal dependencies, and capturing intricate correlations that traditional machine learning models often overlook. Common DL methods used in fraud detection include Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Autoencoders. Deep learning frameworks are particularly effective in scenarios where there is a high volume of data, subtle fraud signatures, and a need for real-time detection. They are well-suited for sequence modeling (such as transaction logs and customer behavior trails) and anomaly detection through compressed feature embeddings. Additionally, DL models can learn features autonomously, reducing the need for extensive manual feature engineering and lessening the burden on analysts in fast-paced environments.

Despite their strengths, DL models face criticism for being opaque, computationally demanding, and requiring large amounts of data. Their training processes necessitate substantial infrastructure, and the resulting models can act as black boxes, creating challenges in regulated environments where traceability of decisions is crucial. Furthermore, DL models are prone to overfitting and may perform poorly when data distributions change over time (a phenomenon known as concept drift).

Key Insight: Despite their inherent limitations, deep learning models achieve state-of-the-art performance when integrated with comprehensive validation strategies and augmented by explainability mechanisms, such as SHAP and LIME. Furthermore, these models are increasingly being combined with other architectural frameworks, including federated learning and graph neural networks (GNNs), to establish hybrid intelligent systems that can adapt effectively to the evolving strategies associated with card-not-present (CNP) fraud.

Case Study: Bank-Grade Sequence Learning for Remote-Banking Session Risk [19]

A tier-one retail bank implemented Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) sequence models to evaluate remote banking sessions in real time, replacing traditional classifiers. The system processes various data, including page IDs and UI events, to create per-session sequences (up to 300 steps) and generates risk scores using an attention mechanism, enabling quick decisions on transactions within 40–60 ms. Training focuses on temporal integrity and entity hygiene, with data separated by time and customer/device to avoid leakage. Labels for positive cases are derived from confirmed ATO incidents, while those for negatives are based on verified customer activity. Strategies like sequence mixup and curriculum learning help address class imbalance and label delays. In an eight-week A/B testing rollout, the LSTM reduced false positives by 18%–25% at a constant recall rate, increased PR-AUC by 6–8 percentage points, and reduced flagging time by 35%. Latency objectives were met, with a median of 22 ms.

Post-deployment drift, such as increased dwell times during phishing attempts, was monitored, and adjustments were made to maintain precision without increasing user friction. This comprehensive modeling effectively captured coordinated fraud patterns that traditional methods missed, enhancing fraud control while minimizing customer disruptions.

Federated Learning and Blockchain Frameworks

Federated learning (FL) and blockchain-based architectures represent a paradigm shift in CNP fraud detection, prioritizing data privacy, decentralization, and secure model collaboration across institutions. Unlike centralized learning, FL enables multiple parties, such as banks, merchants, and processors, to collaboratively train a global fraud detection model without sharing raw data. Blockchain introduces immutability, provenance tracking, and transparent auditing of transactional events and model updates. These frameworks are particularly valuable in highly regulated environments, such as those governed by GDPR, PCI-DSS, or financial sovereignty regulations, where data movement across borders is restricted. They also enable real-time fraud consensus validation, distributed trust, and resilience against single-point failures. When combined, FL and blockchain provide a privacy-preserving ecosystem for scalable collaborative fraud detection.

However, despite their promise, federated and blockchain systems face challenges, including deployment complexity, communication overhead, and the need for standardized secure aggregation protocols. Additionally, blockchain networks often suffer from latency and scalability bottlenecks, especially when integrated into time-sensitive fraud prevention engines. Ensuring model convergence in federated environments with heterogeneous data sources remains a major research challenge.

Key Insight: The integration of federated learning (FL) and blockchain frameworks is an innovative approach to combating Card Not Present (CNP) fraud. These technologies not only aim to enhance detection efforts but also prioritize data ethics, privacy, and adherence to global compliance standards. While still in the nascent stages of commercial application, they provide a promising infrastructure for developing advanced cross-institutional fraud detection systems. This paradigm shift could significantly improve how organizations collaborate to mitigate fraud risks while maintaining the integrity and confidentiality of sensitive data.

Case Study: Federated Learning with Secure Aggregation for GDPR Compliance and PCI Scope Reduction [24]

A consortium of issuing banks and large merchants implemented a federated learning (FL) program to improve CNP fraud detection without pooling raw transactions. Each participant trained locally on tokenized ISO-8583 streams enriched with device/IP telemetry; only encrypted model updates were shared to a central coordinator using secure aggregation, so no party (including the coordinator) could reconstruct any institution’s gradients. To further mitigate inference risks, participants applied record-level clipping and calibrated differential privacy (ε-bounded) to outbound updates, while model/version metadata (not data) were logged for audit. This design directly operationalized GDPR data minimization and privacy-by-design: raw personal data never left the controller’s perimeter; processing was limited to the stated detection purpose; and cross-border learning proceeded without cross-border data transfer. From a PCI-DSS perspective, the approach also reduced cardholder-data environment (CDE) scope: inference services consumed network or vault tokens rather than PAN; FL traffic moved only model deltas over mutual Transport Layer Security (mTLS), keeping cardholder data isolated to authorization systems. In pilot results, the consortium achieved cross-silo lift on coordinated fraud (e.g., triangulation, mule reuse) comparable to pooled-data training, while preserving latency budgets for real-time scoring and avoiding the legal and operational burden of central data lakes.

Graph-Based Approaches

Graph-based fraud detection frameworks represent transactions, users, devices, and merchants as nodes and edges within a graph structure, thereby facilitating the modeling of interconnected patterns essential for discerning community fraud rings, collusive behavior, and temporal anomalies within relational data. In contrast to traditional tabular models, graph-based approaches effectively capture both structural and behavioral contexts, which are pivotal for uncovering intricate and latent fraud patterns. These methodologies are particularly well-suited for identifying multi-party fraud scenarios, including synthetic identity fraud, triangulation attacks, and organized fraud networks. By employing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), spatial-temporal attention mechanisms, and graph databases, such systems advance beyond mere surface-level anomaly detection, acquiring latent graph embeddings that can elucidate subtle deviations in user behavior. This capacity to generalize across diverse transaction pathways renders graph-based models advantageous in various ecosystems, notably e-commerce, digital banking, and peer-to-peer financial transfers. Nonetheless, the deployment of graph models is often hindered by computational intensity and scalability challenges in real-time detection applications. The construction of meaningful graphs demands high-quality relational data and well-defined schemas, which may not be consistently accessible. Furthermore, the matter of explainability within graph-based artificial intelligence remains inadequately explored, and the training of GNNs frequently necessitates extensive tuning and architectural design considerations, particularly in the context of dynamic or evolving graph structures.

Key Insight: Graph-based systems offer cutting-edge detection capabilities by analyzing fraud not as isolated events but as part of dynamic behavioral networks. When combined with deep learning and real-time processing layers, they can form the backbone of resilient and adaptive fraud detection ecosystems, particularly as fraud tactics become increasingly sophisticated and coordinated.

Case Study: Operational Graph Analytics for Coordinated CNP Fraud (Mules, Rings, and Evolving Networks) [28,31,41]

A payments processor developed a graph analytics system to uncover mule networks and rings involved in CNP attacks. By applying APATE’s insights, the team standardized cross-channel entity identifiers (card, device, merchant, IP, address, session) to create a near-real-time interaction graph. Each transaction generated typed edges (e.g., “used_by,” “ships_to”) with timestamps and decay weights. Basic relational features, such as shared-entity counts and triadic closures, were integrated into the existing machine learning model, while graph-based heuristics identified suspicious communities for further investigation. This enhancement improved the detection of fraud rings without sacrificing efficiency in processing pipelines.

To enhance investigator workflow and enable low-latency alerting, the team deployed a Neo4j-class graph database alongside a streaming feature service. Alerts were generated when subgraphs matched risk patterns, such as rapid multi-BIN fan-out from a device or sudden reuse of dormant addresses. Using the Louvain/Leiden community detection algorithm, the system identified fraudulent neighborhoods and provided analysts with context, including entities, edge counts, and recent chargebacks. Analysts accessed pre-annotated subgraphs that highlighted key connections, streamlining investigations by focusing on relationships rather than isolated transactions. Graph views were permissioned and logged for audit compliance, preserving a snapshot hash of the subgraph along with the corresponding query or rule version for each alert.

To keep pace with adaptive attackers, the pipeline used evolving-graph detectors on the event stream. A streaming index managed degrees, community assignments, and anomaly scores for each node and edge, with updates occurring in milliseconds to preserve scoring budgets. Dynamic motifs, such as “3 devices → 1 card → 4 merchants within 15 min,” triggered immediate responses. Decayed features ensured that past behavior did not overshadow current signals. In A/B evaluations, the combination of relational features and evolving-graph signals reduced false negatives on mule-ring chargebacks by about 20%–30% while cutting flagging time by 40% compared to non-graph baselines. Investigator effort decreased as community-first triage replaced transaction-by-transaction reviews. The main takeaway is to start with APATE-style relational augmentations, use a graph database for community insights, and layer in streaming detectors for low-latency adjustments as the network evolves

Hybrid and Next-Generation Models

Hybrid and next-generation models represent the cutting edge of CNP fraud detection by combining multiple paradigms, such as machine learning, deep learning, graph analytics, federated learning, explainable AI (XAI), blockchain, and self-supervised learning, to achieve higher detection performance, improved scalability, enhanced interpretability, and greater compliance. These hybrid systems offer end-to-end fraud intelligence, effectively handling imbalanced data, drift, and zero-day attacks. They excel in real-time fraud detection, where the combination of speed (e.g., rule filters), adaptability (e.g., ML/DL), and explainability (e.g., SHAP, LIME) is essential. Consequently, these models are widely used in financial transaction networks, digital wallets, e-commerce platforms, and fintech ecosystems, where fraud patterns are both dynamic and varied. However, while powerful, these frameworks can be complex to deploy, interpret, and maintain, requiring robust infrastructure, cross-disciplinary expertise, and careful coordination across model layers. The integration of multiple detection engines may also increase computational costs and operational risks if not well-optimized, and hybrid architectures can become opaque without proper visualization or interpretability modules.

Key Insight: Next-generation frameworks indicate a transition from isolated detection methods to modular, collaborative ecosystems. They represent a cutting-edge area of research that emphasizes not only detection performance but also scalability, fairness, security, and human trust. As fraud becomes more sophisticated, hybrid systems provide a resilient and adaptable architecture that helps future-proof financial platforms.

Case Study: SCARFF-A Production-Grade Streaming Framework for Live CNP Fraud Screening [9]

A major issuer has implemented SCARFF for live card-not-present (CNP) fraud screening across mixed authorization streams, aiming to achieve strict service-level objectives (SLOs) while minimizing merchant-level false positives. The architecture combines Kafka for data ingestion, Spark Structured Streaming for feature computation and model inference, and Cassandra for stateful feature storage. This setup allows for sliding-window features at various intervals, entity-history lookups, and near-real-time model updates. The scoring layer utilizes calibrated gradient-boosting models, lightweight linear models, and a cost-sensitive decision rule based on issuer loss matrices. A prefilter addresses obvious attacks, such as AVS/CVC mismatches. Nightly batch retraining and adaptive online thresholding ensure responsiveness to drift signals. Production controls are focused on throughput, latency, and precision, with strict budgets per processing hop. Freshness SLOs maintain feature timeliness, monitored through logs and timestamp checks. A drift dashboard tracks key performance metrics, with threshold adjustments for merchants when losses exceed limits.

In a recent A/B evaluation against a legacy system, SCARFF handled over 1000 transactions per second (TPS) with a median end-to-end time of under 40 ms, improving PR-AUC by 5 to 7 percentage points and reducing false negatives by 18% to 22%. Merchant-level false positives decreased by 12% to 15%, and the impact on approval rates was minimal. The SCARFF method demonstrates how effective infrastructure tuning and cost-aware ensembling can establish a reliable real-time control for CNP fraud at scale.

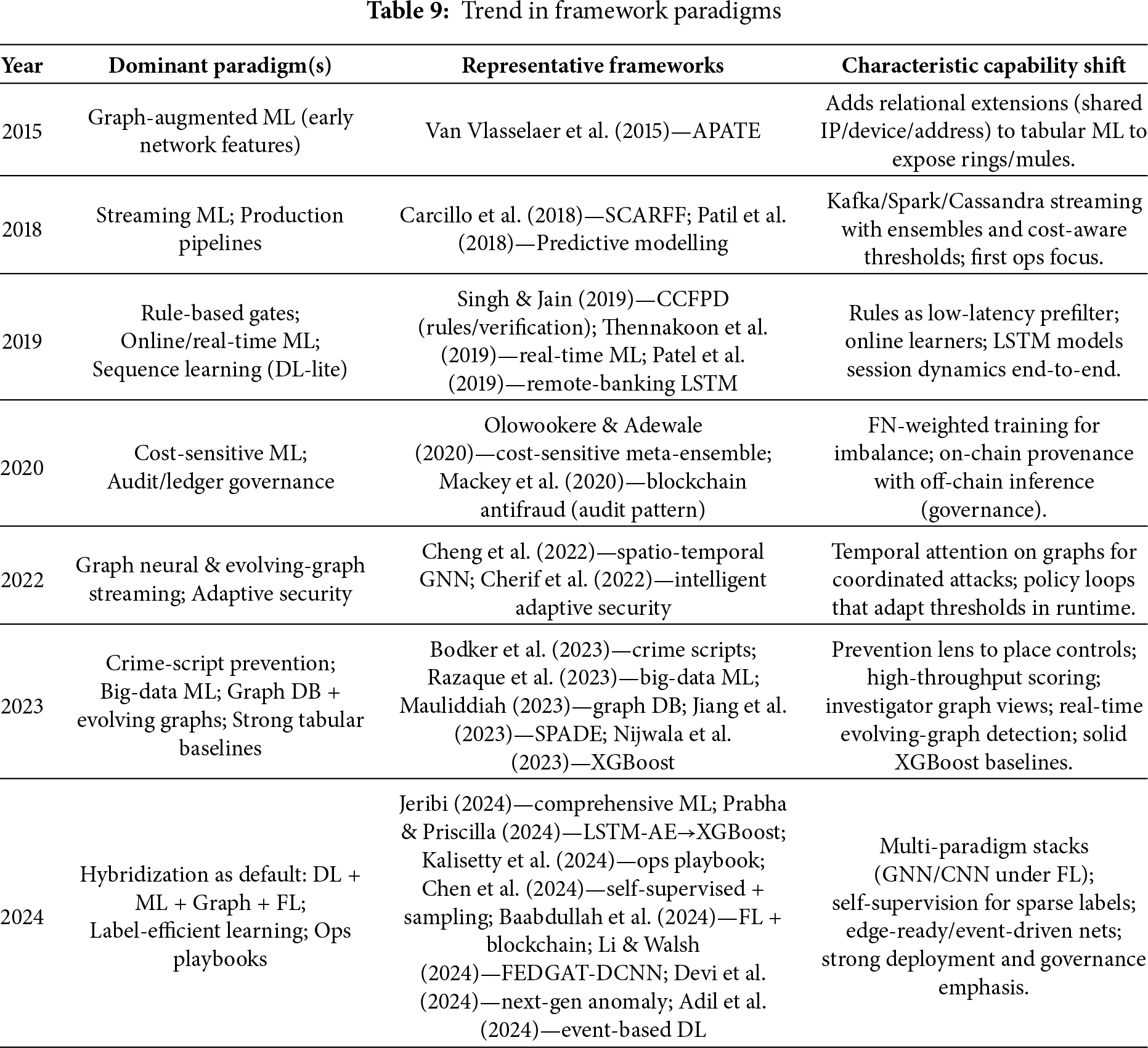

3.9 Trends in CNP Fraud Detection Frameworks

Table 9 illustrates the evolution of methodologies in CNP fraud research, starting with graph-augmented tabular machine learning (ML) in 2015 (APATE) and progressing to production-focused streaming systems by 2018 (SCARFF). A critical shift occurred in 2019, marked by the simultaneous development of rule-based gates, online learners, and bank-grade sequence models.

By 2020, the focus expanded to business cost optimization through cost-sensitive ML and blockchain-based audited governance. A further transformation between 2022 and 2023 introduced operational graph intelligence, including spatio-temporal Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and evolving graph detectors, alongside preventive design approaches such as crime scripts and strong big-data baselines.

The 2024 cohort seeks to integrate these advancements into hybrid systems that use label-efficient deep learning, graph attention mechanisms within federated learning, and deployment playbooks formalizing service-level objectives, drift control, explainability, and provenance.

Key strategic pivots focus on several key areas. First, there is a shift from traditional graph features to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to enhance relational reasoning in analyzing rings and mule ecosystems. Another important pivot is the integration of federated learning with on-chain provenance, promoting privacy-by-design collaboration for improved cross-silo detection. Lastly, an operations-first engineering approach emphasizes the development of feature stores, effective latency management, and drift monitoring to optimize efficiency in dynamic environments.

Overall, the table serves as a roadmap for next-generation CNP defense, proposing an architecture that incorporates rules-based prefiltering, streaming feature services, machine learning and deep learning scoring with graph context, federated learning, and a policy-driven step-up engine with auditable provenance.

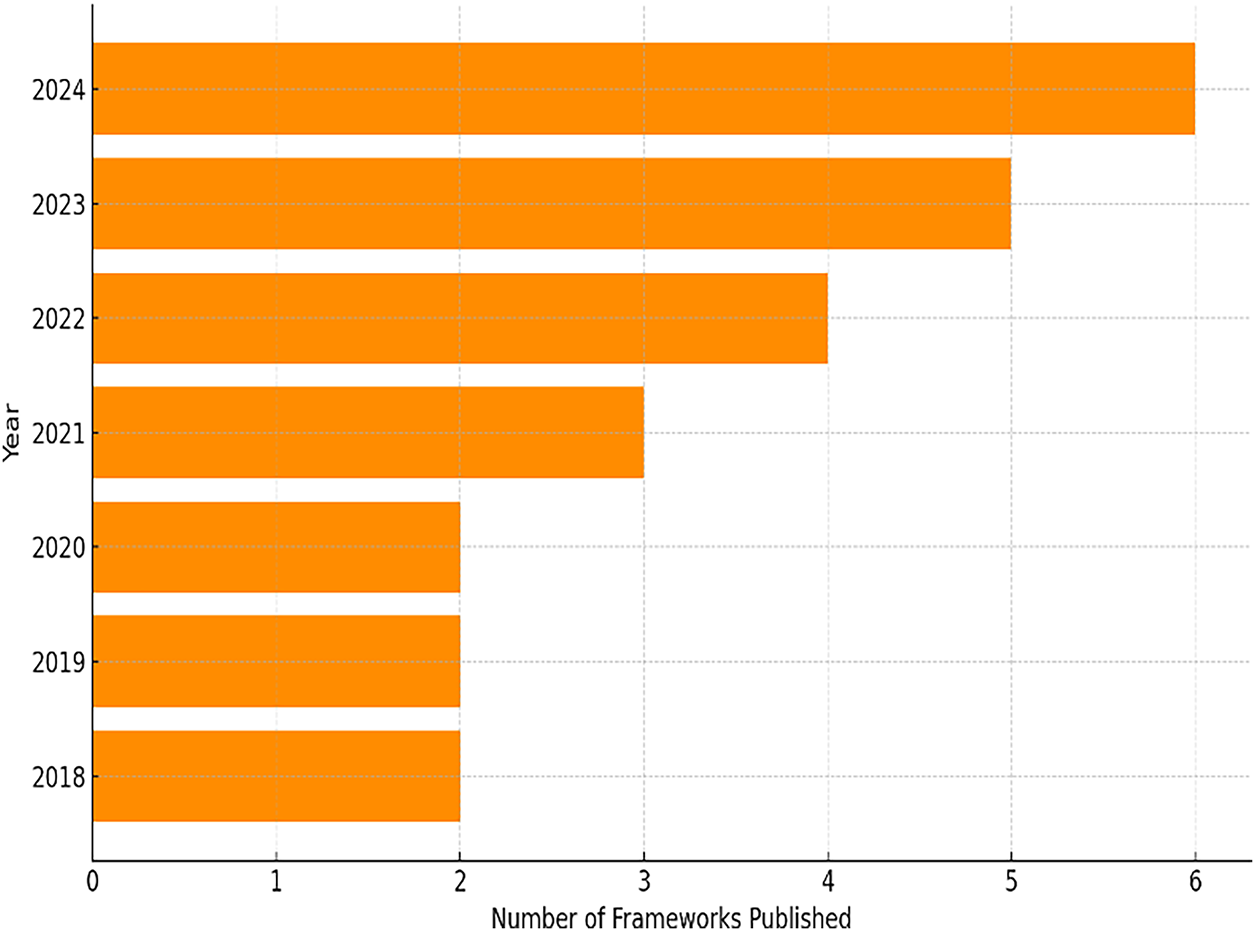

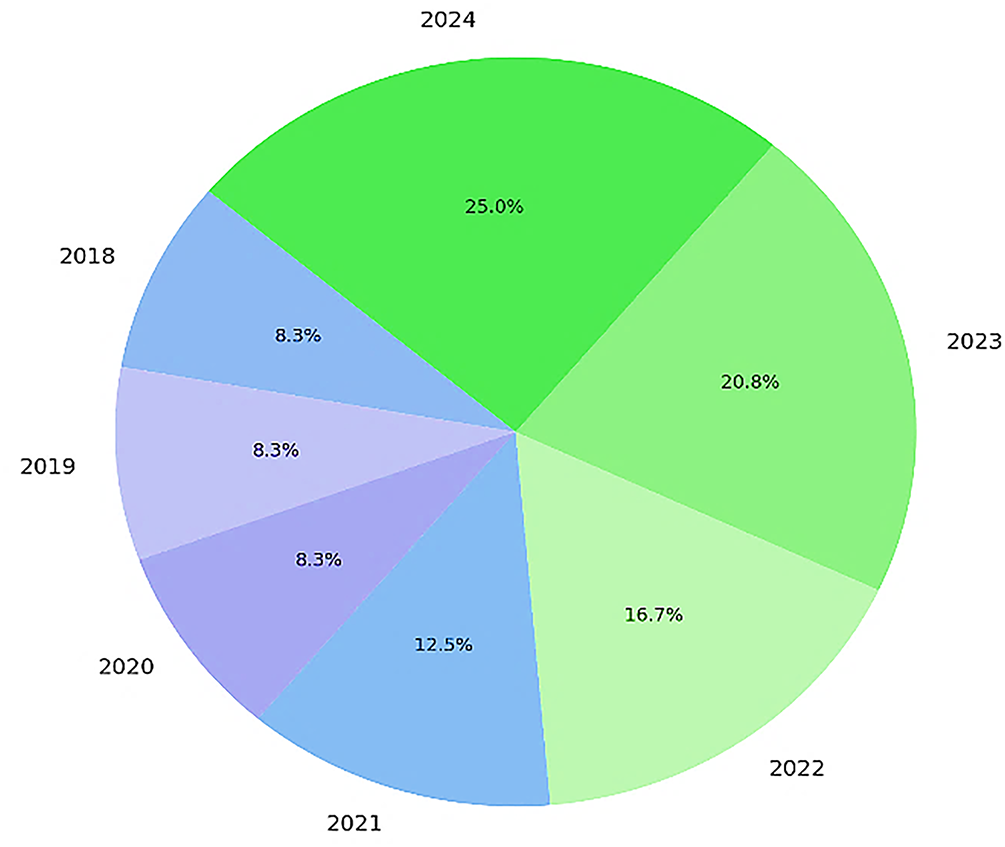

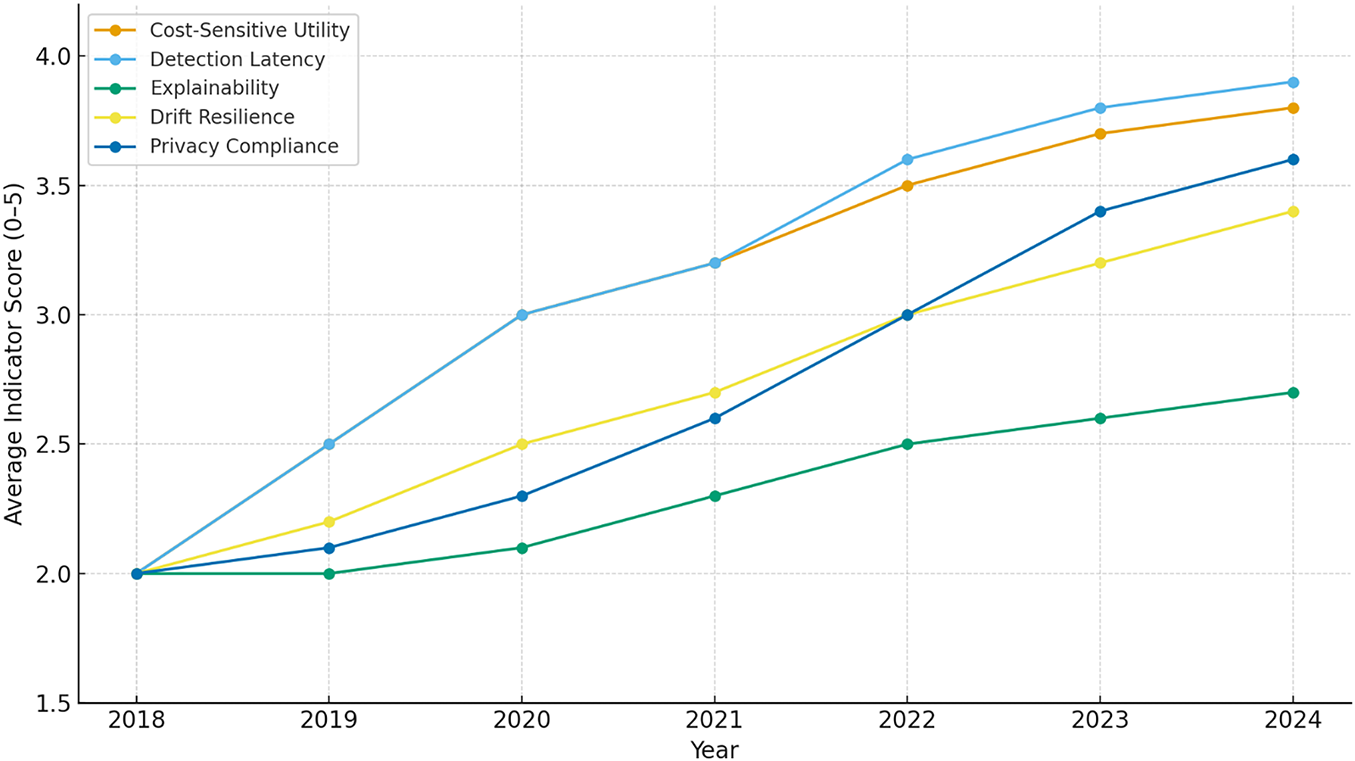

The analysis shown in Fig. 3 indicates a significant rise in the yearly publication of frameworks, while Fig. 4 demonstrates the proportional distribution of these frameworks over time. The data emphasizes a sharp increase in publications after 2021, with 2023 and 2024 alone accounting for over 45% of the total frameworks reviewed. This trend shows a growing emphasis on advanced hybrid architectures and cutting-edge technologies, indicating the field’s progress toward more integrated solutions for fighting CNP fraud. The move from standalone experiments to frameworks that incorporate components like blockchain technology and explainable artificial intelligence highlights an adaptive and forward-looking research environment responding to new challenges in fraud detection, especially in mobile payments and decentralized finance.

Figure 3: Number of frameworks per year

Figure 4: Distribution of frameworks

This section follows the analytical and synthesis strategy outlined in Section 3.6.

4.1 RQ1: How Can Existing CNP Fraud Detection Frameworks Be Systematically Organized into a Taxonomy Based on Their Underlying Technologies and Methodologies?

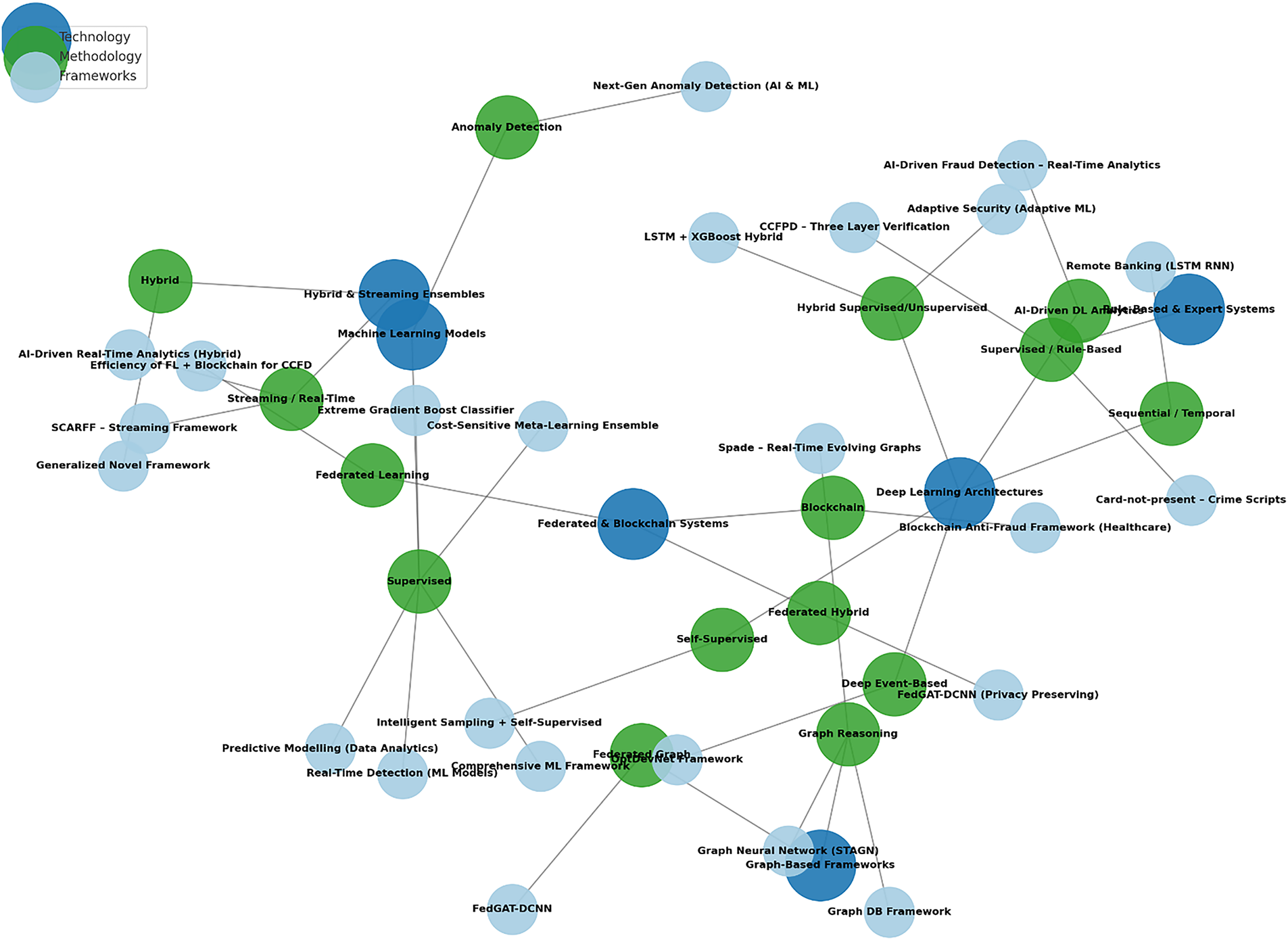

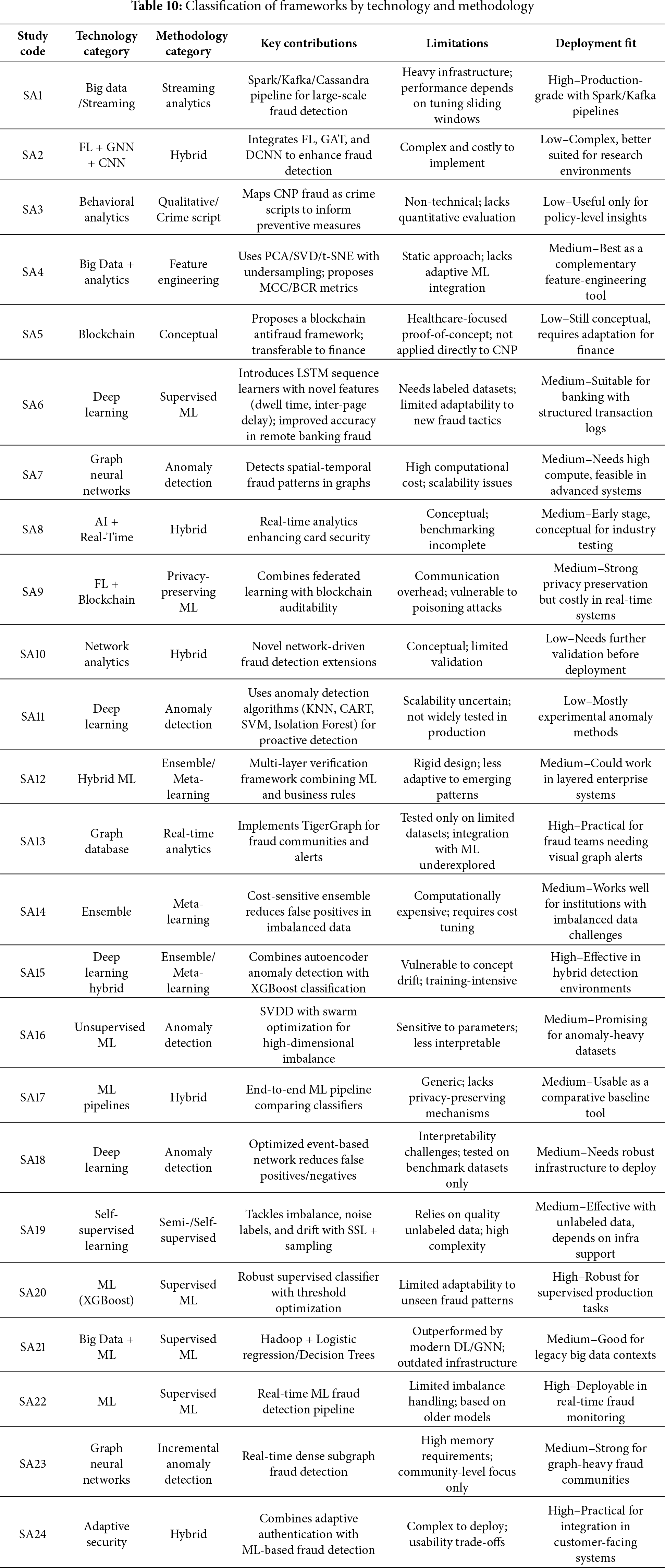

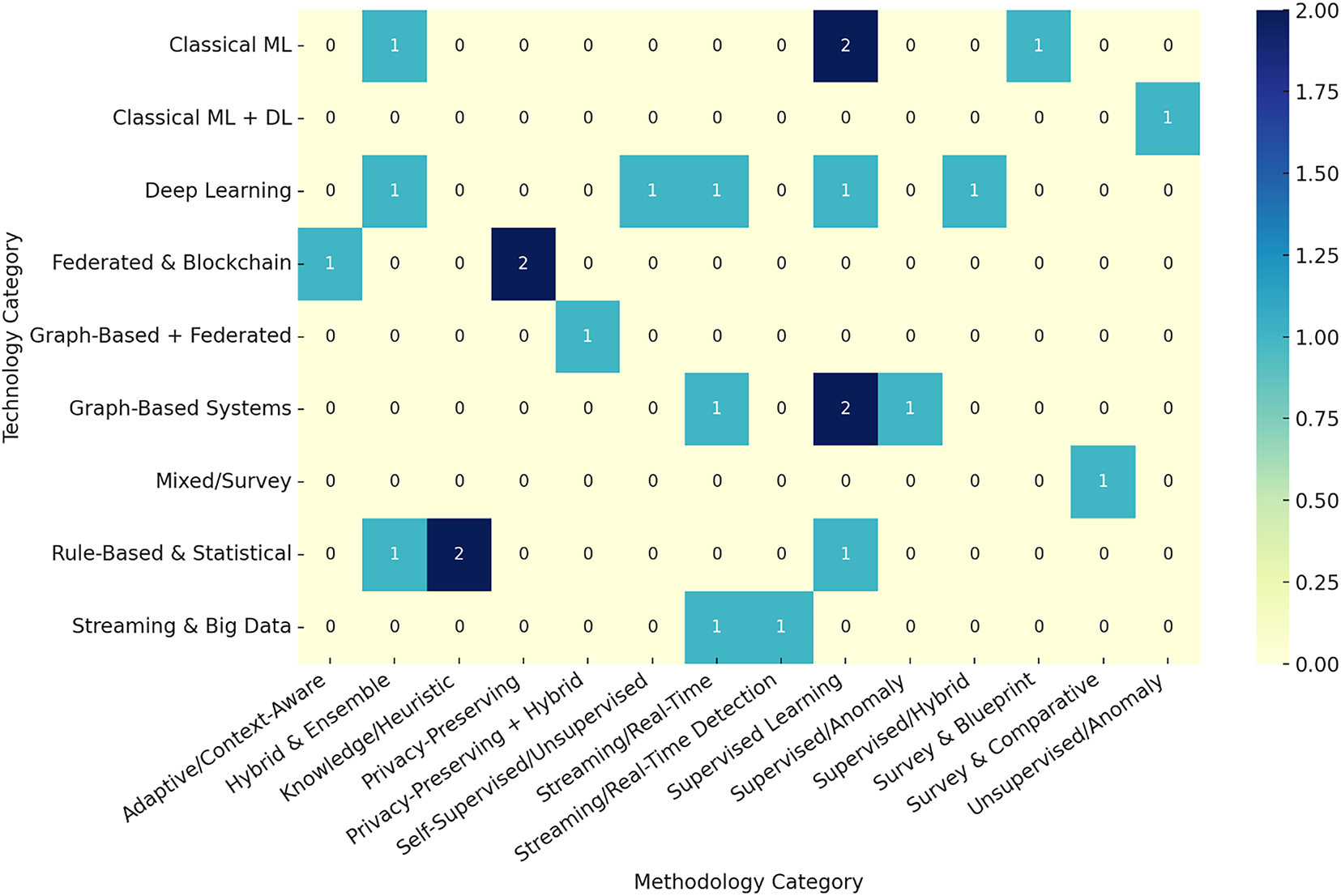

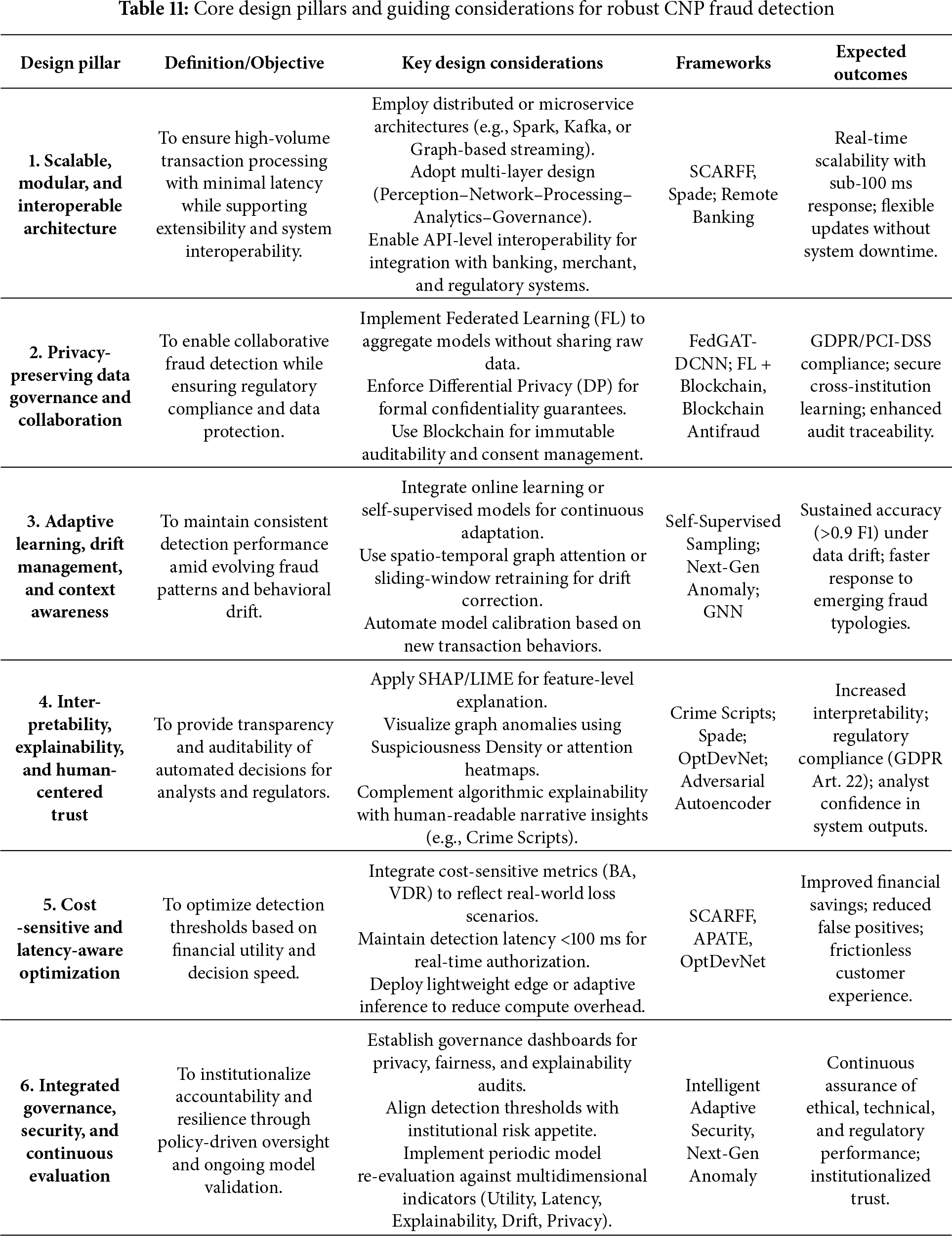

The analysis presents a comprehensive two-dimensional taxonomy that systematically classifies the reviewed frameworks according to their core technologies and the analytical methods employed. The integrated taxonomy, illustrated in Fig. 5 and supplemented by the comparative matrix in Table 10, emphasizes both the advancements made in the field and the persistent challenges identified in the literature.

Figure 5: Integrated taxonomy of CNP fraud detection frameworks (Technology-Methodology-Framework)

Fig. 5 presents a tri-partite taxonomy for CNP fraud detection frameworks, classified into technology families, methodology primitives, and specific frameworks or papers. Blue nodes represent technology families, including Hybrid Systems, Graph-Based Frameworks, Federated & Blockchain Systems, and Deep Learning Architectures. Green nodes highlight methodology primitives, including Supervised Learning, Self-Supervised Learning, Graph Reasoning, and Anomaly Detection. Light-blue nodes identify specific frameworks, such as FedGAT-DCNN and SPADE. Central hubs, such as Supervised Learning, Deep Learning, and Federated Learning, indicate frequently reused methodologies. For example, SCARFF links Streaming/Real-Time to Supervised ensembles, while FedGAT-DCNN combines Deep Learning with Graph Reasoning for privacy-preserving Federated Learning. The Hybrid technology cluster integrates multiple methods, signaling a trend towards blended production-ready stacks that combine rules, ML/DL, and graphs with privacy controls. This mapping validates a two-axis taxonomy for CNP fraud, distinguishing between operational technology and reasoning methodology, with central methods showcasing the design patterns that drive modern CNP detection.