Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Collision-Free Satellite Constellations: A Comprehensive Review on Autonomous and Collaborative Algorithms

1 Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Aviation and Space Exploration (IRC-ASE), King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM), Dhahran, 31261, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Electronics and Computer Technology, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia (UTeM), Durian Tunggal, Melaka, 76100, Malaysia

3 Maynooth International Engineering College (MIEC), Maynooth University, Kildare, R51, Ireland

* Corresponding Author: Ghulam E Mustafa Abro. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Revue Internationale de Géomatique 2025, 34, 301-331. https://doi.org/10.32604/rig.2025.065595

Received 17 March 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 05 June 2025

Abstract

Swarm intelligence, derived from the collective behaviour of biological entities, is a novel methodology for overseeing satellite constellations within decentralized control systems. Conventional centralized control systems in satellite constellations encounter constraints in scalability, resilience, and fault tolerance, particularly in extensive constellations. This research examines the use of swarm-based multi-agent systems and distributed algorithms for efficient communication, collision avoidance, and collaborative task execution in satellite constellations. We provide a comprehensive study of current swarm control algorithms, their relevance to satellite systems, and identify areas requiring further research. Principal subjects encompass decentralized decision-making, self-organization, adaptive communication protocols, and collision-free trajectory planning. The review article examines implementation obstacles, contrasts swarm algorithms with traditional approaches, and delineates potential research avenues to improve the autonomy and efficiency of satellite constellations. The detailed Literature and comparative analysis within this manuscript demonstrate the prospective advantages of swarm intelligence in satellite systems, providing insights for academic researchers and industry personnel alike.Keywords

A satellite constellation is essential for providing global coverage, improving communication, and facilitating many scientific applications, such as astronomy and disaster response [1]. Satellite constellations enable continuous observation of the Earth’s surface, which is particularly important for applications such as disaster management and environmental monitoring [2]. For example, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) constellations provide enhanced spatial coverage and temporal resolution, offering near real-time data availability during natural hazard events. However, the rapid expansion of satellite constellations also introduces challenges that must be addressed. Their increasing number requires careful management to mitigate negative impacts on other fields, particularly astronomy. Design challenges related to coverage and reconfiguration can be addressed through engineering solutions, although these remain complex under certain operational constraints [3]. Furthermore, factors such as atmospheric disturbances and the need for high-fidelity orbital modeling complicate constellation maintenance and stable orbit balancing [4].

Swarm intelligence has emerged as a promising solution in artificial intelligence and optimization, drawing inspiration from the collective behaviors of social insects and other natural organisms [5]. In today’s data-rich and complex technological landscape, innovative problem-solving strategies are becoming increasingly essential. Swarm intelligence offers decentralized and self-organizing approaches to tackle problems that traditional algorithms struggle with, including convergence efficiency, parameter optimization, and scalability [6–10]. The foundational study of swarm intelligence emphasizes the self-organized behavior of social insects, contributing to the development of control algorithms for robotic swarms and improving telecommunication network traffic flow [7]. Core concepts such as stigmergy and biological self-organization underpin these developments. Recent trends show significant growth in academic publications, patents, and industrial applications related to swarm intelligence, with annual increases exceeding 30

Modern satellite constellations, composed of large numbers of satellites operating cooperatively in specific orbits, have revolutionized global communication, Earth observation, and navigation systems [11,12]. Traditionally, these systems relied on centralized control architectures, which often encountered scalability, latency, and fault-resilience issues. Inspired by biological systems such as insect swarms, bird flocks, and fish schools, researchers are now exploring bio-inspired and swarm-based models to enhance the autonomy, adaptability, and coordination of satellite networks. These natural systems demonstrate decentralized decision-making, self-organization, and dynamic task execution in uncertain environments [13,14]. Applying swarm intelligence concepts to satellite constellations allows for decentralized coordination, collision avoidance, and resilient communication—emulating the robustness and flexibility of biological collectives. This paradigm shift offers novel solutions to scalability, fault tolerance, and resource optimization challenges, paving the way for the next generation of intelligent satellite networks [14]. Fig. 1 illustrates this shift by comparing centralized and decentralized constellation configurations. In a centralized constellation, all satellites communicate through a single ground station, creating a single point of control—and potential failure. A decentralised constellation facilitates inter-satellite communication and distributed decision-making, hence improving system robustness and scalability. This architecture facilitates enhanced data routing efficiency and fault tolerance in extensive, dynamic networks [15–18].

Figure 1: Centralised and decentralised constellation satellites

This review study is organised into eight sections, with Section 1 detailing the importance of satellite constellations and delineating the distinctions between centralised and decentralised satellite constellations. Section 2 provides an overview of the ideas of swarm intelligence, as well as the processes by which multi-agent systems execute tasks and engage in collaborative decision-making. Section 3 contains an examination of contemporary satellite constellation control technologies, including Global Positioning System (GPS), Iridium, and Starlink. Section 4 addresses swarm intelligence in decentralised satellite control, focusing on swarm algorithms, distributed decision-making, and self-organization. Additionally, one may discover adaptive communication protocols for satellites, as well as strategies for collision avoidance and trajectory planning. Section 5 discusses the comparative examination of swarm-based approaches. Furthermore, Section 6 addresses the comprehension of contemporary simulation and modelling methodologies, while Section 7 explores the obstacles and potential research avenues. The conclusion is located in Section 8. The entire flow is shown below in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Organisation of the proposed research work

2 Overview of Swarm Intelligence

Swarm intelligence derives from biological systems, as demonstrated by ant and bee colonies, schools of fish, and flocks of birds, as depicted in Fig. 3. These natural systems demonstrate significant organisation in executing functions at a macroscopic scale. “Swarm intelligence” refers to the collective behavior that emerges when each individual agent makes decisions independently, based on its own understanding of the environment. Thus, it is claimed that artificial robots may execute critical functions such as search and rescue and exploration of unfamiliar settings with comparable degrees of automation and intelligence [19–21]. Complex behaviours in swarms arise from basic individual principles. Every member of a natural swarm adheres to particular restrictions. Intricate, self-organised, coordinated actions arise from the collaborative efforts of these agents, independent of centralised oversight [22].

Figure 3: Biological swarm systems (a) Fish School (b) Insect Colony and (c) Bird Flock

This highlights the efficacy and flexibility of swarms in dynamic contexts and provides critical insights for creating robust and resilient systems [23]. Swarm intelligence, a scientific field encompassing distributed control in collective robotics and swarm optimisation, originated from biological observations of the remarkable problem-solving capabilities of social insects [24]. Their colonies, varying from a few to millions of individuals, exhibit extraordinary characteristics marked by persistence, adaptability, and efficiency. During their foraging phase, the neotropical army ants Eciton burchelli may conduct massive hunting expeditions, involving over 200,000 individuals, catching thousands of prey, reaching widths of 15 m or more, and covering areas surpassing 1500

Swarm intelligence is derived from the collective behaviours while individual insects are sophisticated biological “machines” capable of altering their activity in response to diverse sensory stimuli, their cognitive and communicative faculties, however intricate, can fail to tackle the complexities of a colony-scale system. Instead, solutions to these complex problems emerge from the collective interactions of society as a whole [25–28]. This is a self-organised and decentralised phenomenon, often described as “organisation without an organiser.” It allows insect societies to interpret noisy and unclear environmental signals. As a result, they can handle uncertainty and work together to solve complex problems. This swarm intelligence paradigm has been widely employed in artificial systems for tasks like as work allocation, graph partitioning, discrete optimisation, object grouping and sorting, and collaborative decision-making. These artificial systems are constructed upon principles derived from social insects. Nonetheless, similar collective behaviours may be observed in several biological systems, such as schools of fish, flocks of birds, herds of sheep, human crowds, and colonies of bacteria or amoebae, which also serve as inspiration for swarm-based artificial systems. Despite the vast array of biological examples, social insects remain the primary focus of swarm intelligence research, in both theoretical and practical contexts. This stems from the extensive literature concerning their behaviours and the significant parallels between the regulations governing their collective actions and those observed in other species [7].

Researchers want to leverage the self-organising principles of these systems to develop more durable, adaptive, and efficient artificial systems. Swarm intelligence, originating from the collective behaviour of natural systems, serves as an efficient framework for addressing complex tasks. A swarm is an organised collective of individuals with limited personal capabilities who collaborate to solve intricate problems. This method is particularly important in swarm robotics, where multi-robot systems employ decentralised decision-making to replicate natural behaviours, hence enhancing collaboration and problem-solving efficiency [29]. Through the use of these principles, swarm robotics systems can autonomously synchronise operations, allocate jobs, and adapt to dynamic surroundings, delivering solutions that are robust, scalable, and flexible. These systems can replicate the foraging behaviour of ants or the flocking dynamics of birds to perform tasks including exploration, mapping, search and rescue, and environmental monitoring. These bio-inspired algorithms enable self-organization, fault tolerance, and effective resource utilisation, even in unanticipated or bad conditions.The primary objective of swarm robotics is to create systems that can solve intricate issues and propose novel techniques or enhance existing ones. This methodology illustrates the application of nature-inspired ideas in the building of resilient and adaptable multi-agent systems for practical use [30].

Lets take an example of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) that are utilised to modernise the armed forces, defence organisations around, are incorporating UGVs for combat support, surveillance, and reconnaissance. UGVs enhance mission capabilities, mitigate risks to human operators, and improve situational awareness. Some UGVs are designed to operate as swarms, utilising decentralised control systems for intercommunication. Consequently, they may cover greater distances, share sensory information, and accomplish tasks collectively more rapidly than as individual organisms [31,32]. The inaugural agricultural unmanned vehicle platform to achieve global mass production is designated as Unmanned Ground Vehicles. This R150 model, equipped with many operating modes and extensive extension capabilities, was designed for unmanned agricultural operations. It can execute several duties based on diverse agricultural needs, such as intelligent mowing, effective spreading, precision plant protection, transportation of agricultural materials, and epidemic prevention [33].

Autonomous underwater vehicles (UUVs) can also benefit from the use of nature-inspired design ideas in creating robust and flexible multi-agent systems. For example, in autonomous oceanic sampling, swarms of unmanned underwater vehicles can be utilised to gather oceanographic data over extensive regions. By emulating natural swarm behaviours, these systems cooperate to assess factors such as salinity, temperature, and other essential parameters in real time, facilitating thorough mapping of oceanic conditions [34]. In environmental monitoring, swarm UUVs are employed to examine marine habitats. These devices function autonomously while collaborating to monitor coral reefs, collect health data, and identify environmental alterations. These characteristics are essential for assessing the effects of climate change on fragile marine ecosystems, demonstrating how decentralised decision-making and nature-inspired collaboration improve the efficiency and flexibility of robotic systems in practical applications [35,36]. In search and disaster response, swarms of UAVs collaborate to execute search and rescue missions during natural calamities such as earthquakes or floods. By emulating swarm behaviours, these UAVs efficiently survey extensive regions, sharing real-time information regarding their discoveries. They may adapt their flight trajectories in real-time according to identified heat signatures or signals from survivors, so improving the likelihood of prompt rescues. Studies demonstrate that swarm algorithms allow UAVs to optimise coverage and adjust to variable conditions, highlighting their resilience in uncertain settings [37]. In precision agriculture, UAV swarms are utilised to monitor crop health and evaluate soil conditions. Employing swarm intelligence, these UAVs cooperate to collect data from vast agricultural areas, assessing factors such as crop density, soil moisture, and pest infestations. A study illustrated how UAV swarms may autonomously arrange their fly trajectories to reduce data collection redundancy, hence facilitating efficient and thorough surveillance of extensive regions. This method highlights the capacity of multi-agent systems to transform agriculture by enhancing resource efficiency and facilitating proactive decision-making [38]. All three types of multi-agent systems that are nature-inspired are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Types of multi-agent systems with nature-inspired algorithms

Swarm intelligence concepts can be effectively utilised in satellite systems, enhancing performance across various space applications. Inspired by natural collective tendencies, satellite constellations operate as decentralised systems that communicate and collaborate to achieve complex tasks. In Earth observation, satellite constellations can divide and synchronise data collection across vast regions, improving coverage and offering redundancy to reduce data loss from individual satellite failures. In space exploration, satellite constellations can collaborate to scan planetary surfaces, monitor atmospheric conditions, and conduct scientific experiments, offering scalability and resilience in challenging scenarios. Moreover, satellite constellations can adaptively modify their orbits in accordance with changing mission requirements, akin to the real-time adjustments observed in UAV and UUV swarms. This adaptability is particularly beneficial for disaster management, as satellite constellations can rapidly reposition to monitor affected areas and provide high-resolution imagery. Decentralised control systems allow each satellite to make autonomous decisions while maintaining global coordination, so ensuring efficient resource utilisation and resilience to failures. The application of nature-inspired swarm algorithms in satellite systems, similar to UAVs and UUVs, highlights the transformative potential of multi-agent systems in providing efficient, scalable, and resilient solutions for space missions.

Although swarm intelligence provides significant benefits including fault tolerance, scalability, and resilience, it is crucial to recognise the inherent trade-offs in real applications. The fault tolerance of swarm-based systems arises from their decentralised architecture, wherein the failure of individual agents (e.g., a drone, UUV, or satellite) does not undermine the overall functionality of the system. Likewise, scalability is a crucial advantage, enabling the addition of more agents without necessitating a substantial overhaul of the system architecture. Nonetheless, these benefits entail heightened computing demands resulting from the necessity for ongoing local processing and decision-making by each agent, particularly in dynamic or data-intensive contexts. Moreover, latency can emerge as a pivotal component, especially in extensive swarms where inter-agent communication necessitates real-time synchronisation. Distributed consensus algorithms and adaptive communication protocols can alleviate this lag to some extent, but at the expense of increased processing and communication demands. Consequently, whereas SI-based systems demonstrate superior adaptability and resilience, a quantitative assessment of these trade-offs—particularly in extensive deployments—is crucial to guarantee optimal design choices aligned with specific mission requirements.

3 Current Satellite Constellation Control Mechanism

An innovative strategy for satellite systems has arisen from the incorporation of decentralised decision-making processes in multi-agent systems and swarm intelligence. This approach utilises the functionalities of numerous autonomous agents, or satellites, that collaborate and adaptively execute tasks. Each satellite functions as an autonomous entity, making instantaneous decisions based on localised data, hence augmenting system adaptability and resilience. The decentralised framework emulates natural behaviours seen in biological systems, like ant colonies or bird flocks, where collective activities arise from local interactions without necessitating centralised oversight. The autonomous decision-making of each satellite facilitates self-organization, permitting the system to adjust to environmental conditions informed by local knowledge [39–41]. Distributed techniques, including PSO and Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), enable satellite agents to collaborate by utilising local information to investigate and utilise the environment [42]. Reference [43] supports the use of both direct (intersatellite links) and indirect (shared data) communication methods by satellites. Furthermore, decentralised methods of work distribution allow satellites to modify their functions according to situational requirements, employing mechanisms such as bidding and bargaining for effective task management [44]. This methodology has various uses, including formation flying, where satellites can independently modify their positions to improve imaging and sensor functionalities [45]. In Earth observation, swarm intelligence enhances the efficiency and accuracy of data collection by coordinating satellite sensors across extensive regions [46]. Swarm intelligence is crucial in communication networks, facilitating decentralised real-time management of bandwidth and routing to enhance network resilience [47]. In space exploration, satellites utilising swarm-based technologies can collaborate to investigate planetary environments, enhancing data collection and decision-making [48]. The incorporation of multi-agent systems in satellite operations has numerous advantages. Scalability is improved as additional satellites can be incorporated without necessitating substantial redesigns [49]. The robustness is enhanced, allowing the remaining satellites to operate autonomously in the event of one or more failures, hence maintaining mission continuation [50]. Efficiency is an additional benefit, as collaborative problem-solving facilitates optimal resource utilisation, hence decreasing operational expenses [51]. Moreover, the flexibility of the decentralised system enables rapid adaptation to evolving conditions or requirements without dependence on a central authority [52,53]. Nonetheless, there are obstacles to contemplate. With the involvement of additional satellites, the complexity of guaranteeing optimal coordination among the agents escalates. Communication constraints, including bandwidth and latency limitations, might impede real-time decision-making [54,55]. Furthermore, ensuring that decentralised algorithms achieve convergence to optimal solutions in dynamic situations continues to pose challenges [56]. Effectively managing inter-agent conflicts is crucial to prevent inefficiencies or errors in decision-making [57,58]. Notwithstanding these hurdles, the incorporation of swarm intelligence and decentralised decision-making in satellite systems offers significant benefits, enhancing the flexibility, efficiency, and resilience of applications in Earth observation, communication, and space exploration. Satellite constellations, including GPS, Iridium, and Starlink, are vital for numerous global services, encompassing internet connectivity, communication, and navigation. These systems generally function under centralised management to ensure cooperation and enhance efficiency. We examine the design, characteristics, and related issues of each of these systems:

3.1 Global Positioning System (GPS)

The GPS constellation commenced in 1973 as a project of the US Department of Defence. Originally comprising 24 satellites, it was launched between 1989 and 1993 at a height of approximately 20,200 kilometres across three orbital planes. The constellation is presently segmented into six orbital planes, each comprising four satellites, all positioned at a

The Iridium constellation, initially launched by Motorola in the United States and currently managed by the US Department of Defence, offers global satellite communication services, particularly in distant regions without terrestrial network connectivity. The constellation comprises 66 operational satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) at an altitude of 780 km, launched by Falcon 9 rockets between 2017 and 2019. The Iridium network possesses a cross-linked architecture that provides global coverage and supports both voice and data services. Although Iridium’s satellite system provides global connectivity, it has difficulties such as increased latency resulting from extensive signal travel distances and constraints in delivering high-speed internet, as it is designed for low-data-rate applications. Moreover, the system’s satellites have a finite operating lifespan, requiring periodic upgrades and replacements to ensure continuous service [58,59].

Starlink, a venture launched by SpaceX, seeks to deliver high-speed internet access, especially in underprivileged areas. Initiated in 2019, Starlink is swiftly expanding by employing a constellation of tiny satellites in low Earth orbit to create a global broadband network. The system is engineered to provide high-speed internet through a resilient mesh network of interconnected satellites that interact with user terminals and ground stations. References [58–60] provide information on the Iridium and Starlink constellations, including details on the number of satellites, orbital characteristics, and challenges related to latency, debris management, and expansion. Moreover, although Starlink’s satellites are engineered for minimal latency, their orbital altitude and signal propagation time may result in latency levels that exceed those of fiber-optic networks. Additionally, overseeing spectrum and adhering to international standards poses operational difficulties as the network expands.

OneWeb seeks to deliver cost-effective worldwide internet access, especially to underserved regions, using a network of LEO satellites. The system functions at altitudes of 1200 kilometres and utilises advanced satellite control technologies to guarantee efficient satellite operation and synchronisation. Each satellite is outfitted with sophisticated communication technology, facilitating the transmission of signals to user terminals and ground stations, so creating a mesh network that permits real-time coordination. The satellites are engineered for autonomous functionality, encompassing collision avoidance and coverage enhancement, supported by a worldwide network of ground stations monitoring the constellation. References [61–63] offer insights into the OneWeb initiative, covering aspects like its goal to provide global internet access, satellite control technologies, and autonomous functionality. Moreover, there are several optimisation algorithms that can be implemented over the OneWeb initiative to resolve issues like intelligence optimisation, distributed communication and task allocation [64–68].

Project Kuiper, an Amazon initiative, seeks to establish a global satellite network to deliver dependable internet connection, especially in rural and underdeveloped regions. The initiative will launch a constellation of 3236 tiny satellites in LEO at altitudes ranging from 590 to 630 km, principally utilising the Ku-band for broadband connectivity. The satellites will interact with user terminals and ground stations to provide internet services. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has approved this effort for satellite deployment and operational specifications. Project Kuiper’s interconnected satellites, arranged in a swarm arrangement, offer redundancy and resilience, guaranteeing sustained coverage despite potential faults with individual satellites. Kuiper satellites, functioning in low Earth orbit, can diminish latency relative to conventional geostationary satellites, hence providing high-speed internet to rural and remote regions. The compact and lightweight design of Kuiper spacecraft streamlines and lowers launch costs. References [69–71] detail Amazon’s Project Kuiper, including information on the number of satellites, orbital altitudes, and the use of Ku-band for broadband connectivity.

Telesat’s Lightspeed initiative aims to provide high-speed broadband access worldwide, emphasising distant and underserved areas. The program employs a swarm satellite architecture, consisting of a constellation of roughly 298 LEO satellites. This architecture enhances communication capacities and guarantees effective coverage across extensive geographical regions. The swarm architecture facilitates redundancy and dynamic data traffic control, hence augmenting the network’s resilience. Low latency is accomplished by placing satellites in LEO, rendering Lightspeed optimal for real-time applications like online gaming and video conferencing. The satellite system will have high-throughput antennas and sophisticated optical inter-satellite communications to enable efficient data transmission throughout the network. Lightspeed decreases launch expenses through the utilisation of smaller and lighter satellites. Similar to other satellite constellations, Lightspeed encounters regulatory obstacles with orbital slot allocation and space debris mitigation, requiring meticulous coordination to prevent collisions and guarantee safe operation [72–74]. In summary, decentralised satellite constellations such as Starlink, OneWeb, and Project Kuiper as shown in Fig. 5, are enhancing global internet accessibility, especially in disadvantaged areas. These systems employ swarm satellite topologies to deliver high-speed, low-latency communication, ensuring a strong and resilient infrastructure. Nonetheless, the management of orbital debris, spectrum allocation, and regulatory adherence is essential for the future viability and sustainability of these initiatives.

Figure 5: Prominent satellites with swarm intelligence

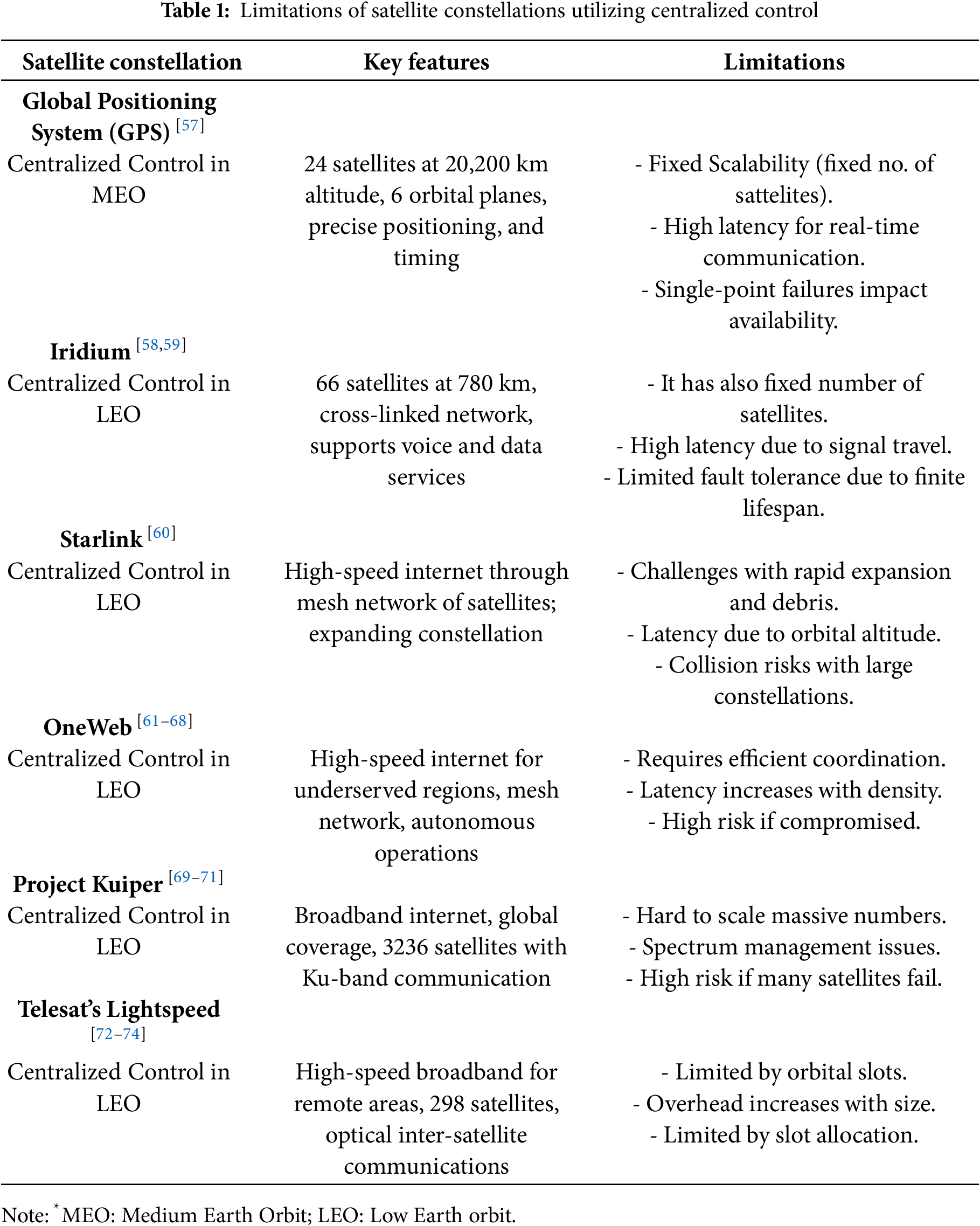

The satellite constellations studied in this Table 1 illustrate the distinct benefits and drawbacks of centralised control systems. Although constellations like GPS, Iridium, and Starlink provide essential worldwide services, including accurate navigation, communication, and high-speed internet access, they have considerable issues regarding scalability, communication overhead, and fault tolerance. Scalability continues to be a significant constraint in all systems, exemplified by the fixed number of satellites in constellations such as GPS, and the difficulties in overseeing extensive deployments in systems like Starlink and Project Kuiper [75–77]. As the size of the constellation expands, the necessity for coordination escalates, hence complicating management and operational efficiency [78,79]. Communication overhead is a significant consideration, especially in systems with elevated latencies, such as GPS and Iridium, where prolonged signal transmission might affect real-time communication [80].

As constellations expand, the management of signal propagation time and spectrum allotment becomes ever more challenging, as evidenced by Starlink and Project Kuiper. Ultimately, fault tolerance is an essential component of satellite constellations; whereas centralised control can enhance reliability, it simultaneously introduces vulnerabilities. A solitary point of failure in these systems can yield extensive repercussions, as evidenced in GPS and Iridium, where satellite integrity and orbital location necessitate continuous oversight. Extensive constellations likeas OneWeb and Project Kuiper may encounter heightened hazards from satellite malfunctions, as the failure of several satellites can impede services. In simple words, although centralised control provides stability and operational coordination, its limitations in scalability, communication efficiency, and fault tolerance highlight the necessity for more resilient and decentralised strategies, particularly as satellite constellations grow and new challenges in space management emerge [80]. The adoption of decentralised control systems in satellite constellations is becoming increasingly vital as extensive projects such as Starlink, OneWeb, Project Kuiper, and Lightspeed expand. These mega-constellations, designed to launch thousands of satellites into orbit, require control systems that can effectively scale while ensuring resilience against possible failures [81–83]. Decentralised control provides substantial benefits compared to conventional centralised systems, especially regarding scalability, communication overhead, and fault tolerance. A primary advantage of decentralised control is its scalability. In contrast to centralised systems, which encounter difficulties in maintaining extensive networks, decentralised systems may efficiently accommodate thousands of satellites without burdening a central control hub. Starlink satellites possess the capability to make localised decisions, facilitating seamless network expansion without a proportional rise in system complexity [84]. Decentralised control decreases communication overhead. Enabling satellites to autonomously make decisions based on local data reduces dependence on ongoing connection with ground stations.

This is especially crucial for constellations like OneWeb and Project Kuiper, where satellites must autonomously manage operations including as data transmission and collision avoidance. This localised decision-making diminishes the need for constant contact with ground stations, hence improving overall system efficiency [85]. Furthermore, distributed systems enhance fault tolerance. In the occurrence of a satellite failure, additional satellites within the constellation can work independently, preserving system operability. An illustrative instance is Telesat’s Lightspeed, where, in the event of a satellite malfunction, the remaining satellites can autonomously adjust their orbits or reallocate their jobs, thereby ensuring mission continuity without centralised oversight [86,87]. As space missions become increasingly complex and extensive, the shift towards decentralised control techniques, such as swarm intelligence and multi-agent systems, is becoming imperative [88]. These approaches will empower future satellite constellations to autonomously oversee operations, diminish communication requirements, and improve system reliability, thus meeting the increasing demand for global connectivity, Earth observation, and space exploration.

4 Swarm Intelligence for Decentralised Satellite Control

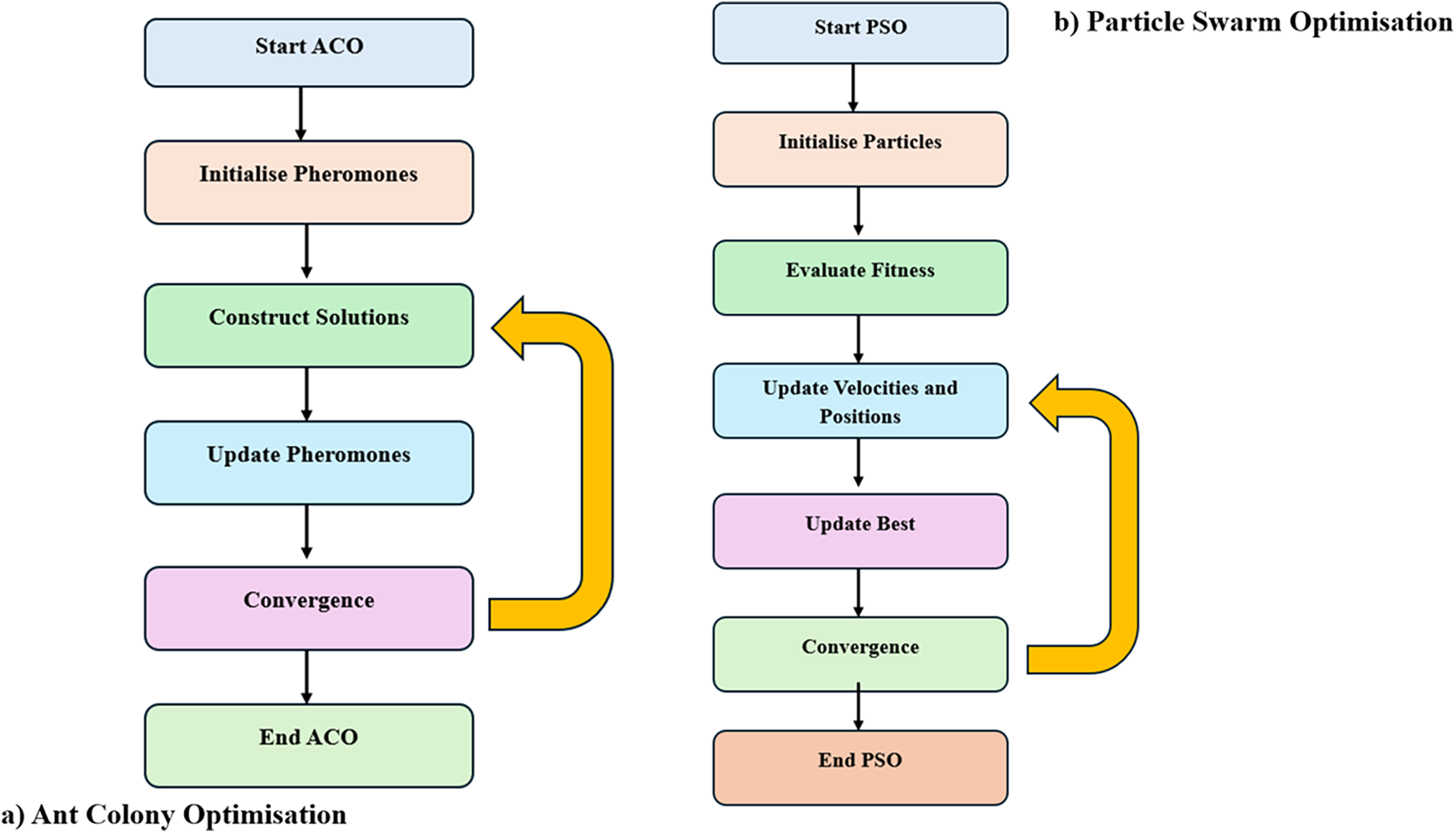

Swarm intelligence systems are based on three fundamental principles: decentralisation, self-organization, and stigmergy, which together provide collaborative problem-solving and optimisation. Decentralisation removes the necessity for centralised authority, enabling individual agents within the swarm to make autonomous decisions based on localised information [89]. This method improves scalability and resilience by allocating the computational burden among several agents and enabling the swarm to adjust dynamically to fluctuating environmental variables [90]. Furthermore, decentralisation enhances resilience by eliminating single points of failure and facilitating the emergence of collective behaviour through interactions among all agents, even during disruptions or failures of individual members [91]. Self-organization, a fundamental principle, facilitates the formation of complex global behaviours from simple local interactions [92]. Individual agents modify their behaviour in reaction to the actions of neighbouring agents through iterative feedback loops and compliance with local regulations. This process produces synchronised patterns and decision-making at the swarm level, promoting resilient and flexible behaviours [89]. These self-organised dynamics enable swarm intelligence systems to efficiently explore solution spaces and converge on optimal or near-optimal solutions without necessitating explicit external coordination [93]. Furthermore, self-organization enhances scalability, allowing for effortless expansion from small to large agent populations without incurring extra communication overhead [94]. Swarm intelligence effectively decomposes intricate tasks into smaller, manageable subproblems, which are allocated among agents to leverage their collective problem-solving abilities [95]. This decentralised coordination diminishes the necessity for centralised processing while guaranteeing effective task execution. In nutshell, swarm intelligence represents a combination of decentralisation, self-organization, and stigmergy, allowing autonomous systems to demonstrate complex behaviours and effectively tackle various difficulties. Comprehending these fundamental concepts is essential for the construction and analysis of algorithms and systems that utilise the complete capabilities of swarm intelligence. Fig. 6 shows a visual aid sharing the steps of ant colony optimisation (ACO) as well as particle swarm optimisation (PSO).

Figure 6: Comparison of ant colony optimization and particle swarm optimization algorithms with procedural steps

4.1 Swarm Algorithms for Satellite Systems

Swarm approaches replicate the decentralised and self-organising behaviours found in biological systems to tackle intricate optimisation, decision-making, and coordination issues. This document examines some notable swarm intelligence methodologies, emphasising their principal characteristics, uses, and constraints.

4.1.1 Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO)

ACO is a metaheuristic inspired by the foraging behavior of ants, particularly their pheromone-based communication system [6,96]. Ants leave pheromone trails to indicate favorable paths, which are reinforced as more ants follow these routes. Similarly, ACO algorithms iteratively build solutions using local heuristic knowledge and pheromone updates, converging toward optimal or near-optimal solutions [96]. ACO demonstrates remarkable strengths in efficiently exploring complex solution spaces by leveraging pheromone trails and stochastic decision-making processes. It excels at solving combinatorial optimization problems, including the traveling salesman problem and vehicle routing problem, by mimicking the foraging behavior of ants. However, ACO has notable limitations, such as its susceptibility to premature convergence, particularly in large-scale or dynamic problems. Additionally, the algorithm is highly sensitive to parameter settings and problem-specific features, necessitating meticulous tuning to achieve optimal performance [96]. ACO exhibits significant efficacy in navigating intricate solution spaces through the utilisation of pheromone trails and probabilistic decision-making mechanisms. It proficiently addresses combinatorial optimisation challenges, such as the travelling salesman issue and vehicle routing problem, by emulating the foraging behaviour of ants. Nonetheless, ACO exhibits significant limits, including its vulnerability to early convergence, especially in large-scale or dynamic scenarios. The method has significant sensitivity to parameter configurations and problem-specific characteristics, requiring careful adjustment to get optimal performance [96].

4.1.2 Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) is a nature-inspired optimisation algorithm that emulates the social behaviour of bird flocks and fish schools, wherein individuals modify their movements by learning from personal experiences and the experiences of their peers [97]. This method involves a population of particles navigating the search space, with each particle adjusting its position according to its individual best position and the swarm’s overall best position [98]. PSO is recognised for its simplicity and ease of implementation, rendering it very accessible to researchers and practitioners. Furthermore, it exhibits resilience in addressing noisy or multimodal optimisation challenges owing to its swarm dynamics and the dissemination of information among particles [98]. Nonetheless, PSO has its limitations; it is susceptible to early convergence, especially in high-dimensional or irregular search spaces. Furthermore, its performance is acutely dependent on characteristics like acceleration coefficients and inertia weight, necessitating meticulous calibration for ideal outcomes [97,98].

4.1.3 Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) Algorithm

The ABC algorithm is derived from the waggle dance of honeybees, which conveys information regarding prospective food sources [99]. This method employs synthetic bees to investigate the search space and progressively enhance viable solutions via local and global communication channels [100]. The ABC method is recognised for its simplicity and swift convergence, rendering it appropriate for practical optimisation challenges. It is especially efficacious for ongoing optimisation endeavours, including function optimisation and parameter estimation [99,100]. Nonetheless, the approach is less efficient for discrete or combinatorial optimisation tasks due to challenges in navigating non-continuous search areas. Moreover, its efficacy is heavily influenced by control factors, including the quantity of employed and onlooker bees, requiring meticulous parameter adjustment for peak performance [99].

The FA is a bio-inspired optimisation technique based on the luminescent behaviour of fireflies, which utilise light intensity to attract others and synchronise their patterns [101]. In FA, each potential solution is depicted as a firefly, with brightness reflecting the value of the optimised objective function. More luminous fireflies have greater allure, attracting other fireflies towards them. The movement of fireflies is affected by their proximity, with nearer and more luminous fireflies exerting a greater allure. This method allows the algorithm to iteratively modify the placements of fireflies within the search space, directing them towards optimal or near-optimal solutions [101]. The FA excels in addressing multimodal and dynamic optimisation challenges because to its intrinsic capacity to adapt and navigate the search space effectively. It excels at recognising varied, high-caliber solutions through a harmonious blend of local intensification and global discovery. This versatility renders it suitable for applications characterised by a dynamic optimisation landscape or the presence of many peaks [101]. Nonetheless, the algorithm possesses several limitations. It may face challenges when navigating complicated or uneven terrains, as these can hinder its exploration efficiency and result in unsatisfactory outcomes. Moreover, the FA significantly depends on randomisation to augment variation in the search process, which, although advantageous in certain contexts, may occasionally lead to slower or inferior convergence, especially in highly limited situations [101]. Notwithstanding these problems, the FA continues to be an invaluable instrument for diverse optimisation tasks, exhibiting resilience and adaptability across multiple domains.

4.1.5 Differential Evolution (DE)

Differential Evolution (DE) is a resilient population-centric optimisation algorithm derived on the principles of natural selection and genetic diversity [102]. It functions by iteratively producing new candidate solutions via a combination of mutation, crossover, and selection processes. These mechanisms facilitate the gradual evolution and convergence of the candidate solution population towards the global optimum. By utilising the variances among randomly selected solutions within the population, DE proficiently equilibrates exploration and exploitation in the search space, rendering it an adaptable and adaptive optimisation method [103]. One of the primary advantages of DE is its capacity to address a diverse array of optimisation issues, encompassing both discrete and continuous domains. It is especially advantageous for issues involving noisy goal functions and nonlinear restrictions, where conventional approaches may falter. The straightforward structure and ease of application, along with its effectiveness in navigating intricate solution spaces via differential variation, have rendered DE a favoured option among researchers and practitioners [102,103]. Notwithstanding its advantages, DE possesses limits that require consideration. The algorithm’s efficacy is acutely dependent on control parameters, including the crossover probability and scaling factor, which require meticulous calibration to attain ideal outcomes. Moreover, DE may encounter challenges in high-dimensional search environments, where the curse of dimensionality can diminish its efficacy. Likewise, it may encounter difficulties with non-smooth or extremely irregular objective functions, which might impede convergence and restrict its efficacy in these situations [103]. Nevertheless, DE continues to be a potent and adaptable instrument for addressing a broad spectrum of optimisation problems across several domains.

Genetic Algorithms (GAs), derived from the tenets of natural selection, are effective instruments for addressing intricate optimisation challenges. They apply a population-based methodology, utilising genetic operations including selection, crossover, and mutation to evolve solutions across several generations [104]. GAs are very beneficial for managing satellite constellations, providing effective solutions to complex problems. Their capacity to manage non-linear, multi-dimensional tasks renders them optimal for orbital manoeuvre planning and communication optimisation [104]. They exhibit significant adaptability, adapting efficiently to changing surroundings affected by elements such as orbital debris and atmospheric conditions [105]. GAs facilitate the concurrent assessment of many configurations, aiding in the discovery of optimal solutions [106]. Furthermore, they demonstrate proficiency in multi-objective optimisation, effectively balancing trade-offs among critical objectives such as fuel economy, coverage, and system stability [107]. GAs exhibit robustness to local optima through crossover and mutation, facilitating comprehensive exploration of the solution space [108]. Moreover, their incorporation with environmental and dynamic simulation models improves the validity of control strategies [109]. The applications of GAs in satellite constellation control encompass optimising orbital determination and maintenance to reduce fuel consumption, scheduling communication links for effective data relay, and enhancing fault tolerance through constellation reconfiguration in response to satellite failures [110]. Nonetheless, despite their advantages, GAs can be computationally intensive. This difficulty can be alleviated by employing distributed computing and parallel processing, facilitating more efficient algorithm execution in resource-intensive contexts. Swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms offer innovative solutions to complex optimization problems by mimicking natural behaviors such as decentralization, self-organization, and adaptability.

Techniques like ACO, PSO, ABC, FA, DE, and GA excel in various optimization domains, including multimodal, multi-objective, and combinatorial challenges. While each method has its strengths, such as robustness in dynamic environments or efficiency in combinatorial optimization, they also face limitations like early convergence and parameter sensitivity. However, by combining these algorithms in hybrid approaches and leveraging advancements in parallel computing, these methods can overcome their constraints and deliver even more powerful solutions. As these techniques evolve, they continue to push the boundaries of computational intelligence, offering scalable and adaptive solutions for a wide range of complex, real-world problems.

To systematically compare swarm control algorithms, we recognise that assessing their applicability for satellite applications necessitates a taxonomy based on domain-specific constraints, including orbital mechanics, communication latency, energy efficiency, and decentralised decision-making capabilities. The publication examines common algorithms, including PSO, ACO, and Artificial Potential Fields (APF), while highlighting that their usefulness is contingent upon mission specifications. For example, PSO is optimal for continuous-space optimisation, rendering it beneficial for formation control and trajectory planning, while ACO excels in addressing discrete job allocation challenges, such as dynamic reconfiguration or data routing in satellite swarms. Both may necessitate adjustments to manage time delays, sporadic connectivity, and fuel-efficient navigation in space. Table 2 has been given to comprehensively assess significant swarm algorithms based on evaluation criteria pertinent to satellites. This systematic comparison elucidates the merits, limits, and adaption requirements of each algorithm in the context of decentralised satellite control scenarios.

4.1.7 Transferability of Biological Swarm Behaviors to Satellite Systems

Although swarm intelligence draws inspiration from the collective behaviour seen in biological systems, it is crucial to acknowledge that not all natural concepts can be immediately applied to satellite constellations. Specific behaviours, like decentralised decision-making, coordination through local interactions, and stigmergy (indirect communication via environmental signals), shown by ant foraging and avian flocking, are especially relevant. These ideas can be used in satellite operations via intersatellite communication, adaptive job allocation, and distributed control—facilitating efficient coverage, redundancy, and resilience in dynamic mission contexts. Nevertheless, other ideas necessitate considerable modification owing to the distinctive limitations of orbital dynamics. For example, physical movement models in natural systems—such as the fluid wheeling of bird flocks or the pheromone trails of ants—do not correspond directly with the rigid trajectory control, orbital mechanics, and fuel limitations characteristic of space-based systems. Consequently, although the overarching methods of collaboration and robustness are transferable, the specific implementations must be modified to consider considerations such as time delays, communication intervals, energy efficiency, and orbital stability. By distilling the core principles of swarm coordination and integrating them into physics-informed models, satellite swarms can leverage biologically inspired intelligence while adhering to the constraints of space operations.

4.2 Distributed Decision Making and Self-Organisation

Fostering autonomy in satellites necessitates comprehending dispersed decision-making and self-organization, especially in contexts requiring coordinated actions without centralised oversight, as seen in swarm satellite systems or constellations. Distributed decision-making denotes the process wherein individual satellites make determinations based on localised information and interactions with other satellites, rather than depending on a central authority [111]. This method allows satellites to function autonomously, adapting to changing conditions and enhancing their operations without external guidance. Self-organization augments autonomy by enabling satellites to adapt to unexpected problems, such as evading debris or modifying their missions, through the ongoing reconfiguration of their roles and duties. By adhering to basic local regulations, satellites can demonstrate intricate, coordinated actions that fulfil mission goals. This feature enables effective resource utilisation, including energy management and coverage, despite changing circumstances [112]. Satellites employing distributed decision-making and self-organization can autonomously allocate activities such as environmental monitoring, data transmission, and photography, according to individual capabilities and mission requirements [113]. They can also adjust to new demands, such as modifying their formation or behaviour in reaction to shifts in mission objectives or external influences like meteorological conditions. Furthermore, these satellites exhibit resilience to failure, as they may reallocate tasks or assume activities autonomously in the case of a malfunction, without requiring ground control intervention. The integration of these decision-making processes enhances satellites’ effectiveness, resilience, and autonomous operation in dynamic environments, which is especially advantageous for contemporary space missions requiring elevated coordination and adaptability without centralised oversight.

4.3 Adaptive Communication Protocols

Swarm intelligence systems in satellite constellations depend heavily on robust satellite-to-satellite interactions and reliable data transfer mechanisms, which are facilitated through complex and adaptive communication protocols. These protocols must dynamically adjust to varying mission demands, environmental conditions, and network topologies to maintain performance and resilience [114]. One of the primary roles of these adaptive protocols is to optimize inter-satellite coordination by enabling satellites to share data and make decisions in a distributed yet synchronized manner, thereby improving the collective performance of the constellation [115]. However, implementing such adaptability poses several technical challenges, particularly in maintaining consistency, managing resource constraints, and ensuring low-latency communication under harsh space conditions. A core feature of adaptive communication protocols is dynamic bandwidth allocation, which adjusts bandwidth usage based on real-time communication needs. For instance, when a satellite needs to transmit high-resolution Earth observation data, the protocol can temporarily allocate it greater bandwidth. Protocols like Time-Division Multiple Access and Code-Division Multiple Access are commonly used to implement this flexibility. However, integrating these schemes in a dynamic space environment requires careful scheduling and coordination, especially to avoid signal collisions and latency under high-traffic loads [116].

Adaptive modulation and coding (AMC) is another vital component. In high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, satellites can switch to higher-order modulation schemes such as 16-QAM to increase data throughput. Conversely, under degraded conditions, they may revert to more robust schemes like Binary Phase Shift Key to preserve link reliability [117]. The challenge lies in real-time SNR estimation and fast switching between modulation schemes without interrupting data transmission. Additionally, frequency hopping is often employed to mitigate interference and enhance communication security by periodically changing transmission frequencies. While effective in reducing jamming and eavesdropping risks, implementing frequency hopping requires precise synchronization among all nodes in the constellation, which can be computationally intensive in large-scale satellite swarms. Several communication mechanisms complement these protocols in satellite constellations. Peer-to-peer communication via Intersatellite Links significantly reduces latency by allowing direct satellite communication without relying on centralized ground stations. However, maintaining stable ISLs with precise pointing and tracking across rapidly moving satellites is technically demanding. Gossip protocols, where satellites share data with neighboring nodes, enhance decentralization and fault tolerance but may increase communication overhead due to redundant messaging in dense constellations [118].

Multi-channel communication allows simultaneous use of multiple frequency bands to improve throughput. However, the complexity of hardware support for concurrent transmissions and interference management across channels must be addressed. Similarly, geographic routing—where satellites determine optimal communication paths based on spatial position—offers improved routing efficiency but requires accurate location awareness [118] and predictive trajectory modeling, which can be error-prone in highly dynamic orbital environments. Delay-Tolerant Networking (DTN) protocols are particularly useful in situations where continuous connectivity cannot be guaranteed, such as deep-space missions or Earth observation from polar orbits. DTN allows satellites to store data temporarily and forward it when a connection becomes available. The challenge here lies in data prioritization and buffer management to prevent loss or excessive delay during critical missions [119].

To enhance communication reliability and extend range, cooperative relay protocols allow satellites to retransmit signals on behalf of others, ensuring network continuity even when some nodes are out of direct range. Additionally, consensus algorithms help satellites agree on shared information, such as orbital changes or mission priorities. Although powerful, these algorithms require efficient consensus under communication delays and node failures—conditions common in satellite constellations. The integration of machine learning further enriches adaptive communication by enabling satellites to learn optimal communication strategies from historical data and real-time feedback. For example, learning-based protocols can predict link quality variations and preemptively adjust transmission parameters [107]. However, the need for onboard computational resources and energy efficiency limits the complexity of models that can be deployed. Moreover, cross-layer optimization—which coordinates the networking, application, and communication layers—has shown potential in improving overall system throughput and reliability. Yet, synchronizing actions across layers remains a challenge due to their varying time scales and dependencies [119].

In summary, adaptive communication protocols are fundamental to the success of swarm intelligence in satellite constellations. While they significantly improve resilience, efficiency, and cooperative behavior in complex space environments, their real-world implementation must address challenges such as synchronization, computational load, limited power availability, and robustness under dynamic conditions. As research advances in adaptive protocol design and space-based networking, satellite constellations will become increasingly capable of supporting a wide range of critical applications—from deep space exploration to Earth monitoring and disaster response. To mitigate intermittent connectivity and orbital perturbations—such as those induced by the J2 effect, atmospheric drag, or manoeuvres to avoid space debris—various techniques have been proposed and incorporated into adaptive communication and control systems. Delay-Tolerant Networking (DTN) is a fundamental method for addressing connectivity disruptions, enabling satellites to store and transmit data packets while communication with peers or ground stations is interrupted. To enhance dependability, ephemeris-based prediction models may be linked with routing algorithms to foresee communication blackouts and dynamically redistribute traffic. To manage perturbations, perturbation-aware routing and control algorithms account for non-Keplerian forces, such as those arising from the Earth’s oblateness represented by the J2 term, to guarantee effective formation maintenance and reliable coverage. Furthermore, collision-avoidance-aware scheduling techniques enable satellites to temporarily redirect communications or adjust orbital trajectories while maintaining swarm coherence. The integration of sensor fusion and space situational awareness (SSA) data improves the constellation’s capacity to address unforeseen occurrences, such as conjunction alerts. The integration of these processes with decentralised swarm-based coordination facilitates more resilient and adaptable satellite operations amid both predictable and unpredictable orbital perturbations.

4.4 Collision Avoidance and Trajectory Planning

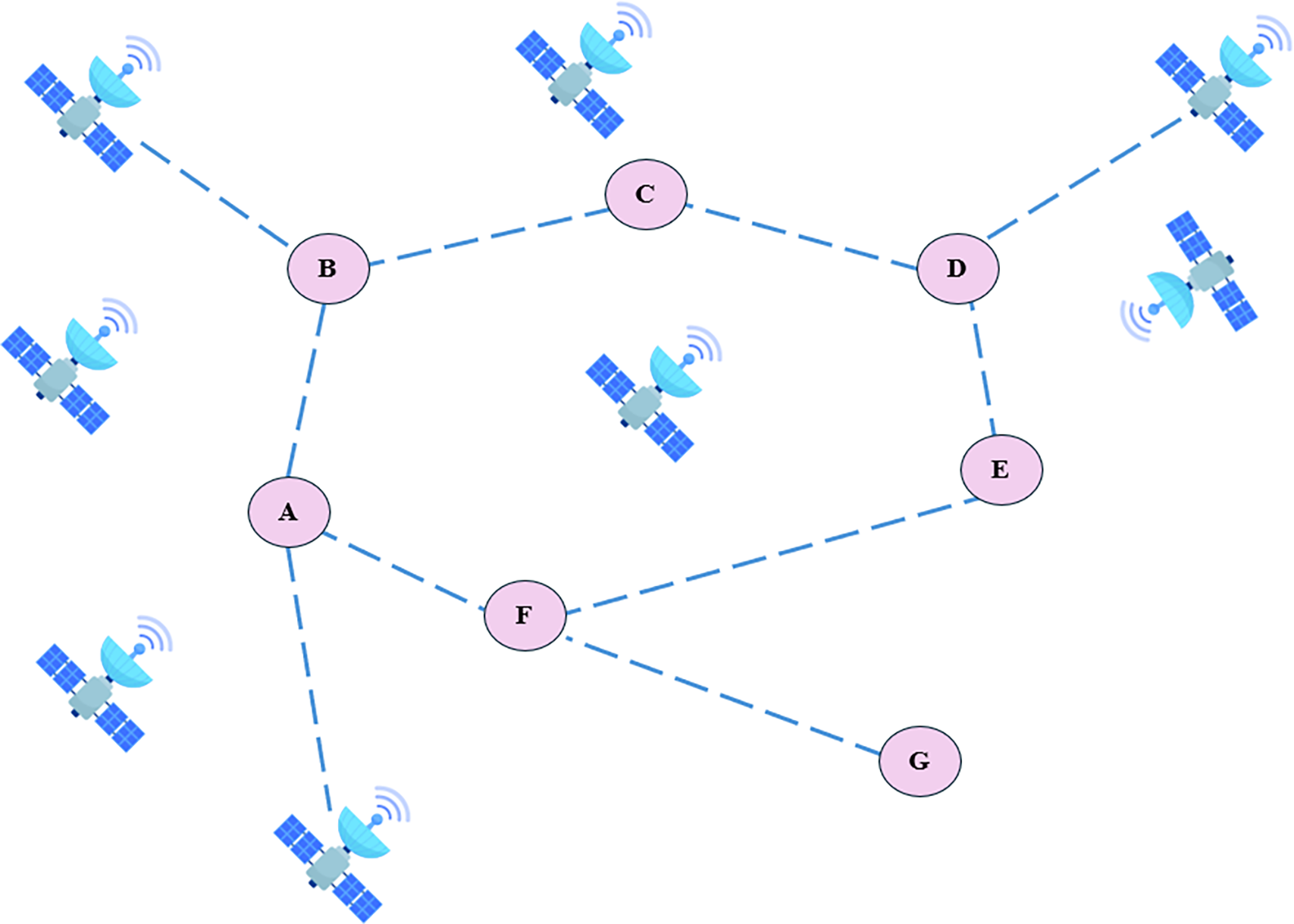

Swarm algorithms are essential for autonomous path planning and collision avoidance, especially in extensive satellite networks. These algorithms allow satellites to enhance their trajectories while maintaining safety and efficiency through decentralised decision-making and collaborative behaviours. A fundamental characteristic of swarm algorithms is collaborative behaviour, when satellites share information regarding their positions and velocities. This enables them to anticipate possible collisions and modify their trajectories accordingly. By using a decentralized approach, satellites can autonomously evaluate collision risks based on the positions of nearby satellites. This reduces dependence on a central authority and enables faster responses to potential collisions [119]. Additionally, flocking behavior—modeled after the movement patterns of bird flocks—ensures that satellites maintain safe distances from one another. As shown in Fig. 7, this behavior enables each satellite to adjust its orientation and velocity in real-time based on the positions of its neighbors. As a result, their trajectories are optimized, group coherence is maintained, and the risk of collisions is minimized [120].This illustration depicts a decentralised satellite constellation intended to facilitate autonomous path planning and resilient inter-satellite communication. Each node designated A through G represents a distinct satellite capable of executing localised choices. The dashed lines between nodes represent established communication linkages, creating a dynamic mesh network architecture. This decentralised paradigm enables satellites to autonomously share data and redirect information, ensuring resilience against node failure or signal congestion, in contrast to centralised systems that depend on a ground station or central hub. This network design improves real-time adaptation, facilitates collision avoidance, and offers scalable coordination, rendering it very useful for applications including Earth observation, worldwide connection, and autonomous space missions. The geographical arrangement and interconnectivity illustrate how satellites can collectively sustain network integrity while manoeuvring or relocating in orbit.

Figure 7: Autonomous path planning and collision avoidance in extensive satellite networks

Moreover, the incorporation of swarm algorithms helps improve collision avoidance and path planning. Hybrid methodologies can integrate techniques such as ACO for real-time modifications in reaction to probable collision hazards or environmental alterations, alongside PSO for preliminary path planning. This integration facilitates comprehensive route planning that adjusts to evolving conditions, guaranteeing both efficiency and safety [121]. Swarm algorithms facilitate real-time adaptation, permitting satellites to modify their trajectories depending on immediate data from onboard sensors and intersatellite communications. This is especially critical in orbit, where conditions can fluctuate swiftly, necessitating that satellites adjust their courses on short notice to evade unexpected obstructions or imminent collisions [122]. Notwithstanding their efficacy, swarm algorithms encounter numerous obstacles. Communication latency may hinder the timely exchange of positional and velocity data between satellites, thereby compromising collision avoidance. Swarm algorithms can include predictive models to estimate satellite positions based on past trajectories, thereby alleviating the effects of communication delays [123]. As the quantity of satellites within a network escalates, sustaining efficient coordination and communication gets increasingly difficult. Scalable swarm algorithms, particularly those employing hierarchical communication structures, facilitate the management of bigger networks by maintaining effective communication and coordination as the system grows [124]. Moreover, the integration of machine learning with swarm algorithms might augment path planning and collision avoidance by enabling the algorithms to learn and adapt to dynamic settings, hence enhancing their capacity to anticipate and respond to fluctuating conditions [125]. Advanced simulation tools are crucial for optimising swarm algorithms prior to their implementation in real missions. These instruments enable researchers to evaluate and enhance swarm algorithms in more intricate circumstances, hence ensuring their resilience and efficacy in practical applications [126]. Swarm algorithms provide an effective solution for autonomous path planning and collision avoidance in extensive satellite networks. Through the optimisation of trajectories via decentralised collaboration, these algorithms will be crucial in addressing the increasing complexity of satellite constellations, hence assuring safe and efficient operations in space.

5 Comparative Analysis of Swarm-Based Approaches and Conventional Methods

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the design Swarm intelligence algorithms, such as ACO, PSO, and the ABC algorithm, possess unique advantages for optimisation tasks based on the specific issue area. ACO, influenced by the pheromone-mediated communication of ants, is especially efficacious in combinatorial optimisation challenges such as the Travelling Salesman Problem and the Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) [6,96]. Nonetheless, it may have difficulties with large-scale issues due to early convergence. Conversely, PSO emulates social behaviours observed in avian and aquatic species, rendering it appropriate for continuous optimisation challenges. PSO often exhibits a more rapid convergence than ACO, although it encounters difficulties related to premature convergence in high-dimensional environments [97]. ABC, informed by the foraging habit of bees, achieves a balance between exploration and exploitation, rendering it more adaptable than ACO and PSO, especially in combinatorial and continuous optimisation challenges [99]. Nature-inspired optimisation techniques such as the FA, DE, GA, and ACO each offer distinct methodologies for solution exploration. FA emulates the bioluminescence of fireflies to facilitate the search process, demonstrating superiority in multimodal optimisation owing to its global search capabilities [101]. DE, conversely, employs mutation, crossover, and selection to provide novel solutions and is especially proficient in continuous optimisation problems, although it may encounter difficulties with discrete optimisation jobs [102]. Moreover, GA employs selection, crossover, and mutation to develop solutions, demonstrating efficacy in multi-objective optimisation but encountering difficulties with convergence velocity and computing complexity in extensive solution spaces [104]. In comparison to ACO, FA and DE demonstrate enhanced performance for global exploration and robustness in intricate, dynamic optimisation challenges [101,102].

In practical applications, each approach has proven useful across several areas, including satellite constellation optimisation and vehicle routing problems (VRP). GA and ACO have been effectively utilised in satellite constellation optimisation, with GA demonstrating superiority in multi-objective optimisation and ACO excelling in the combinatorial arrangement of satellite orbits [96,104]. In routing issues, PSO and ABC are prevalent methods, with PSO being effective for large-scale Vehicle Routing issues (VRP) and ABC provides a more resilient search approach in dynamic contexts [97,99]. Algorithms such as FA and DE exhibit robust efficacy in multimodal and dynamic optimisation challenges, with FA preserving global search capabilities and DE offering a methodical strategy for solution development [101,103]. This comparative analysis elucidates the merits of each algorithm in particular domains, providing essential insights for choosing the best appropriate approach according to issue type and requirements. The comparative performance has been summarized in Table 3.

6 Constraints Related to Recent Modelling Approaches

Recent advancements in satellite constellation optimization have been significantly influenced by the limitations inherent in current simulation and modeling methodologies. A primary challenge lies in accurately modeling large-scale satellite constellations, which requires advanced algorithms to manage numerous dynamic variables, orbital configurations, and environmental factors. These simulations often face processing constraints, especially when dealing with high-dimensional, real-time orbital adjustments. As the number of satellites in a constellation increases, the complexity of their interactions also grows, making it more difficult to ensure optimal coverage and communication efficiency while minimizing fuel consumption and orbital decay [6,96]. A notable limitation is the restricted accuracy in modeling satellite behavior under dynamic environmental conditions. Real-world phenomena such as atmospheric drag, gravitational perturbations, and the Earth’s non-uniform gravitational field significantly affect satellite trajectories. These factors are frequently underrepresented in many contemporary models, leading to discrepancies between simulated outcomes and actual satellite performance. Furthermore, many models assume ideal conditions—such as perfect satellite alignment and precise maneuverability—which oversimplify the realities of space operations. This simplification hampers the validation of proposed solutions when applied to real-world satellite constellations [97–99]. Scalability also remains a critical limitation of current modeling methodologies. Many platforms struggle to optimize large constellations, particularly those involving thousands of satellites. These systems require the coordination of numerous orbital and communication parameters, increasing the complexity of the optimization process. Additionally, many modeling approaches still rely on centralized control mechanisms, which introduce inefficiencies and reduce resilience as the size of the satellite network grows. While decentralized or distributed approaches are being explored to address these issues, they present new challenges in coordination and synchronization across the network [101,102]. Overcoming these limitations in modeling and simulation is crucial for the future optimization, deployment, and management of satellite constellations.

7 Challenges and Open Research Directions

Despite the significant advancements in satellite constellation optimization, several challenges remain, particularly in simulation and modeling approaches. One of the primary challenges is the difficulty in accurately modeling complex satellite interactions and environmental factors, such as gravitational perturbations, atmospheric drag, and orbital decay. These effects are often oversimplified in many models, leading to discrepancies when transitioning from simulation to real-world applications [6,96]. Moreover, the computational burden associated with simulating large-scale constellations, particularly those involving thousands of satellites, remains a critical issue. The high-dimensional nature of these problems makes real-time optimization and decision-making challenging [97,99]. Another challenge lies in the scalability of existing simulation methods, which struggle to handle the dynamic and evolving requirements of large satellite networks. Many approaches still rely on centralized control, which becomes inefficient and less resilient as the constellation size increases. Distributed and decentralized models are being explored, but these introduce additional complexities related to coordination and synchronization among satellites [101,102]. Additionally, incorporating dynamic environmental changes, such as space weather and collision avoidance, into optimization models remains an open research direction. Addressing these challenges opens up several research avenues, including the development of more accurate and computationally efficient models, the exploration of decentralized control mechanisms, and the integration of adaptive optimization techniques that can account for real-time dynamic changes in satellite behavior and environmental conditions. Such advancements will be crucial for the next generation of satellite constellations, enabling more resilient, efficient, and scalable space-based networks. Besides the issues associated with modelling and scalability, hardware constraints on satellites significantly hinder the real-time implementation of swarm intelligence (SI) algorithms. The majority of satellites, especially small ones like CubeSats, possess constrained onboard processing capabilities, memory, and energy resources. These limitations hinder the execution of computationally costly optimisation algorithms in real-time. Moreover, the dependability and bandwidth of inter-satellite links (ISLs) can substantially influence the efficacy of distributed algorithms necessitating frequent communication for coordination and decision-making. To address these restrictions, SI algorithms must be modified to function in resource-constrained situations by utilising lightweight computation, event-driven updates, and asynchronous communication mechanisms. Methods like edge computing, which involves delegating computation to more proficient nodes within the network, alongside the implementation of compressed data exchange or localised rule-based decision-making, might alleviate the computational strain. Moreover, hybrid architectures that integrate centralised planning with decentralised execution may offer an effective equilibrium between autonomy and efficiency. Confronting these hardware-level problems is crucial for actualising the complete potential of SI in extensive satellite constellations and guaranteeing their adaptability in fluctuating space settings.

This research has examined the revolutionary potential of swarm intelligence in the administration and operation of satellite constellations, highlighting its benefits compared to conventional centralised control systems. Swarm-based multi-agent systems, drawing inspiration from the collective behaviours of biological entities, offer a viable paradigm for addressing scalability and fault tolerance challenges inherent in extensive satellite constellations. Decentralised control mechanisms promote robustness, self-organization, adaptive communication, and efficient collision avoidance in these systems. The comparative analysis of swarm-based methodologies against conventional control systems has underscored the notable benefits of decentralised decision-making, especially in dynamic and uncertain contexts. Swarm intelligence, with its intrinsic capacity for adaptation and collaboration, presents potential solutions to critical issues in satellite systems, including trajectory tracking, communication protocols, and real-time decision-making. Nonetheless, the incorporation of swarm intelligence into satellite constellations presents several challenges. The study highlights other domains requiring additional investigation, especially in the creation of resilient algorithms adept at managing intricate interactions among numerous satellites within a dynamic spatial context. Furthermore, the utilisation of swarm intelligence in satellite constellations necessitates a more sophisticated methodology for simulation, modelling, and real-time execution. This research provides significant insights into the future of satellite constellation management, encouraging academic researchers and industry professionals to further investigate and enhance swarm intelligence methodologies. By tackling existing limitations and adopting forthcoming innovations, the autonomous functioning of satellite constellations can be enhanced, resulting in more efficient scalable, and robust space systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the support provided by Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Aviation and Space Exploration (IRC-ASE) King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Ghulam E Mustafa Abro: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—original draft and editing. Altaf Mugheri: Methodology; Writing—orginal draft and editing. Zain Anwar Ali: Project administration; Resources; Writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Choo N, Ahner D, Little B. A survey of orbit design and selection methodologies. J Astronaut Sci. 2024;71(1):4. doi:10.1007/s40295-023-00379-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Milillo P, Riel B, Minchew B, Yun S-H, Simons M, Lundgren P. On the synergistic use of SAR constellations’ data exploitation for earth science and natural hazard response. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2016;9(3):1095–100. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2015.2465166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ferringer M. General framework for the reconfiguration of satellite constellations [Ph.D. thesis]. University Park, PA, USA: The Pennsylvania State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

4. Folta D, Newman LK, Quinn D. Design and implementation of satellite formations and constellations. In: AAS/GSFC 13th International Symposium on Space Flight Dynamics. Greenbelt, MD, USA; 2019. NASA Technical Report No. AAS-98-304. [Google Scholar]

5. Sotomayor M, Pérez-Castrillo D, Castiglione F. Complex social and behavioral systems: game theory and agent-based models. 1st ed. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2020. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0368-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chakraborty A, Kar A. Swarm intelligence: a review of algorithms. In: Nature-inspired computing and optimization. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 475–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50920-4_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Priyadarshi R, Kumar RR. Evolution of swarm intelligence: a systematic review of particle swarm and ant colony optimization approaches in modern research. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2025. doi:10.1007/s11831-025-10247-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Brezočnik L, Fister I, Podgorelec V. Swarm intelligence algorithms for feature selection: a review. Appl Sci. 2018;8(9):1521. doi:10.3390/app8091521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Figueiredo E, Macedo M, Siqueira HV, Santana CJ, Gokhale A, Bastos-Filho CJ. Swarm intelligence for clustering—a systematic review with new perspectives on data mining. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2019;82(1):313–29. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2019.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zangana HM, Sallow ZB, Alkawaz MH, Omar M. Unveiling the collective wisdom: a review of swarm intelligence in problem solving and optimization. Inform. 2024;9(2):101–10. doi:10.25139/inform.v9i2.7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bu Y, Yan Y, Yang Y. Advancement challenges in UAV swarm formation control: a comprehensive review. Drones. 2024;8(7):1–25. doi:10.3390/drones8070320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cheraghi AR, Shahzad S. Past, present, and future of swarm robotics. In: Arai K, editor. Intelligent systems and applications. Vol. 296. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 497–510. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-82199-9_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Asri EG, Zhu ZH. An introductory review of swarm technology for spacecraft on-orbit servicing. Int J Mech Syst Dyn. 2024;4(1):3–21. doi:10.1002/msd2.12098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]