Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Some Important Features of the Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

Faculty of Geodesy, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, HR-10000, Croatia

* Corresponding Author: Miljenko Lapaine. Email:

Revue Internationale de Géomatique 2025, 34, 793-808. https://doi.org/10.32604/rig.2025.066916

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 28 September 2025; Issue published 06 November 2025

Abstract

The paper investigates the properties of the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection, which is often used in normal aspect in atlases for maps of the northern and southern hemispheres. The field of research is theoretical in nature and assumes a mastery of mathematics because it deals with map projections. The transverse aspect is commonly used for eastern and western hemisphere atlas maps. In addition, the Hammer projection was created from the transverse aspect of that projection. Therefore, if we want to get to know the Hammer projection better, we must first investigate the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection in detail. While investigating this projection, it was observed that the equations of the transverse aspect can be represented in several ways. After that, it was necessary to determine the most suitable form of the equations of that projection for the calculation of partial derivatives, which are necessary for determining distortions. The article presents the distribution of factors of local linear scales along the (pseudo) meridians and (pseudo) parallels, and found that in the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection, there can exist only one point where the distortion is equal to zero. The general case of a normal and transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection has not been observed so far, and that is the new contribution of this article.Keywords

Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777) was a physicist, mathematician, astronomer and cartographer. His mathematical research included algebra, spherical trigonometry and perspective. He was the first to prove that π is an irrational number and the first to systematically use hyperbolic functions. His work on the theory of parallel lines is particularly significant. In his work Photometrie, he clearly distinguished the concepts of brightness and illumination, thus laying the foundations of photometry. In addition, he investigated the refraction of light in the atmosphere, then the paths of comets, and in this connection discovered new properties of conics. In his astronomical works, binary stars are mentioned for the first time [1,2].

According to Frischauf [3], the beginnings of the theory of mapping one surface onto another belong to Lambert, who dealt with the general problem of mapping a sphere and an ellipsoid onto a plane in the chapter Anmerkungen und Zusätze zur Entwerfung der Land und Himmelscharten (Notes and Additions to the Establishment of Maps of the Earth and Sky) printed in the third part of his Beyträge zum Gebrauche der Mathematik und deren Anwendung (Contributions to the Use of Mathematics and Its Application) [4].

Lambert was the first mathematician who dealt with the general properties of map projections. He considered the properties of conformality and equivalence and pointed to the fact that these two properties are mutually exclusive. In the aforementioned book, he published seven new map projections that he did not name, and today they are known as:

1. Lambert Conformal Conic

2. Transverse Mercator

3. Lambert Azimuthal Equivalent

4. Lagrange Projection

5. Lambert Cylindrical Equivalent

6. Transverse Cylindrical Equivalent

7. Lambert Conic Equivalent

Let us also mention that the Lambertian function is defined as a mapping

This mapping appears in the equations of the normal Mercator projection [5,6].

In a previous paper [7], I researched points and lines on maps where the distortions are equal to zero. This is followed by examples of cylindrical, azimuthal, pseudocylindrical and a few other projections. These examples show that there need not be standard points at all, that there may be one or two standard points, as well as entire standard lines. In conclusion, I stated that in future research, other map projections should be included where the mathematical approach is somewhat more complex. These are, for example, the Aitoff, Hammer and Winkels Triple projection. The Hammer projection was created from the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection. That is why it was necessary to first look for the distribution of linear distortions that occur during that projection, which is the topic of this article.

In normal azimuthal projections, images of meridians are lines that intersect at a single point at angles equal to the difference in their longitudes, and images of parallels are concentric circles centered at the intersection of the meridians. Accordingly, the general equations of normal azimuthal projections in polar coordinates can be written in this form

where

If a rectangular coordinate system x, y is set up so that its origin is at the center of the projection, then the rectangular coordinates in the right-handed (mathematical) coordinate system of each point in that projection are determined by the equations:

We will arrive at the formulas for the local linear scale factors h along the meridian and k along the parallel from the general formulas by determining E and G from the projection equations

Azimuthal projections are most often used for small-scale maps, so we approximate the Earth with a sphere. For a sphere of radius R [8],

The minus sign in expression (5) is chosen because

The general formulas for normal azimuthal projections for the sphere are therefore

In Formula (7)

Without loss of generality, we can assume that

3 Normal Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

Maps in the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection are often used in normal aspect in atlases for maps of the polar regions, i.e., the northern and southern hemispheres. The transverse aspect is usually used for atlas maps of the eastern and western hemispheres. The oblique aspect is used for atlas maps of continents and oceans. The projection is recommended for maps of approximately circular areas that need to preserve the area [8].

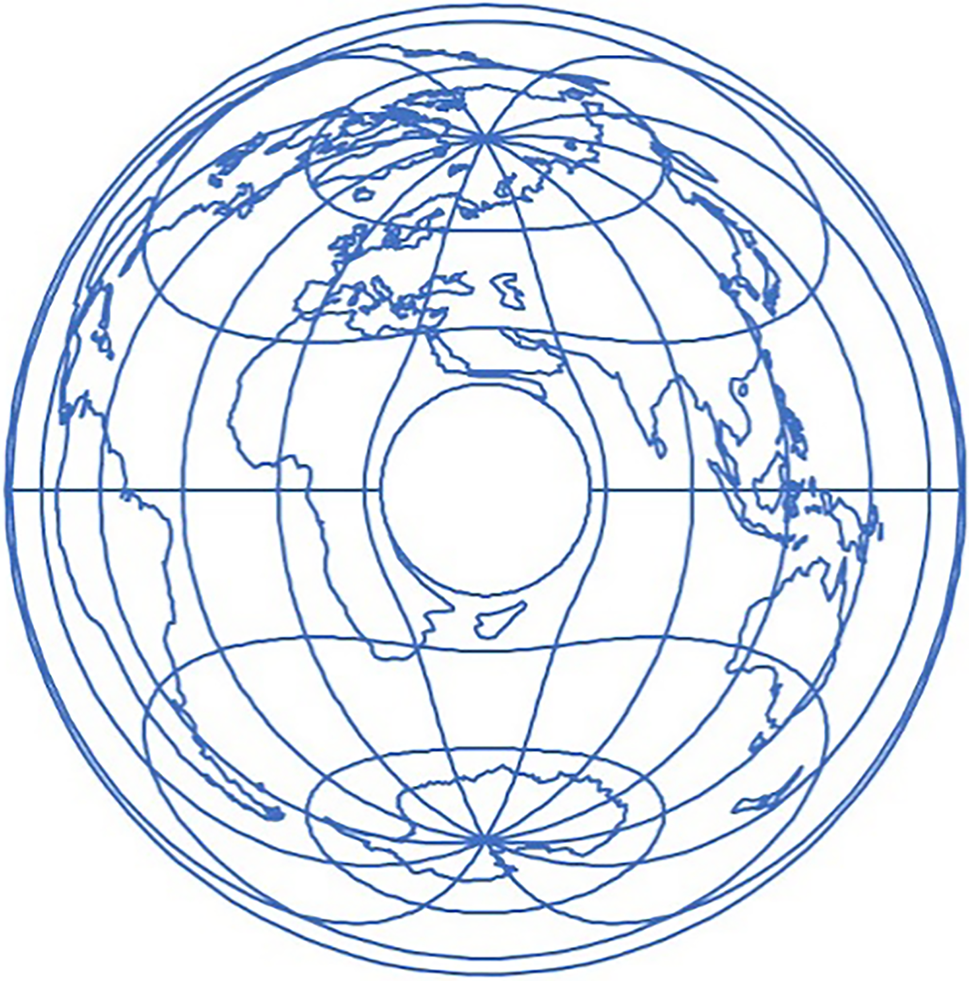

In the simple normal aspect of this projection, the meridian images are straight lines that intersect in the image of the pole. The angles between the meridian images are equal to the angles between the meridians on the sphere. The parallel images are concentric circles. The distances between the parallel images gradually decrease with distance from the pole. In this projection, the entire sphere of the Earth can be shown (Fig. 1). The distortion is moderate in the image of a hemisphere but becomes very large on a map of the whole Earth (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: World map in the simple normal Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection

Figure 2: Distribution of linear distortions in the simple normal Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection, h blue, k red. The horizontal axis indicates degrees. The vertical axis indicates h and k, which are real numbers defined by (21). The yellow line is drawn at height 1

Let us derive the equations of the simple normal Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection. The equivalence condition in normal azimuthal projections of the sphere is expressed by the equation

where h and k are local linear scale factors along the meridian and parallel [8]. Inserting the expression for the local linear scale factors (7) into (10) we obtain

from where

By integrating, we get

If we set the condition that the North Pole is mapped as a point (for

By inserting this value into (13) we get

This expression can also be written in the form

so it is finally

We chose the sign in (17) so that

If we insert the obtained value for

and then

Therefore, the mapping equations and expressions for the local linear scale factors and distortion in simple normal equivalent azimuthal projections are:

A map of the world in the simple normal equivalent azimuthal projection is shown in Fig. 1. From expression (20) we see that the images of all parallels are circles. If

For a point to be standard for a certain normal azimuthal projection, it is necessary and sufficient that at that point [7]

For the normal Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection (20), condition (23) reads:

from which immediately follows the unique

If we set the condition that the North Pole is mapped not only as a point, but as a circle (Fig. 3), it follows from (13) (See also Section 3.3)

and in that case it should be

so that the expression under the root is non-negative. From (25) it is easy to see that the North Pole will be mapped into a circle of radius

Figure 3: World map in the normal aspect of the general Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection,

For the radius of the parallel images defined in (25), condition (23) gives

After squaring, expression (27) can be written in the form

Since the left side of (28) is always non-negative, and by assumption (26) and (28) will be fulfilled only for

3.2 “Tangent” and “Secant” Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

In the cartographic literature, tangent and secant projections are often mentioned. I am committed that the terms tangent and secant projection should be avoided in general, because they only make sense in perspective projections [9]. First, the derivation or definition of the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection makes no mention of tangency or contact. The position of the projection plane in relation to the sphere being mapped is completely irrelevant. Furthermore, conclusions about an undistorted circle if a secant plane is used are a complete failure, because in the previous section we showed that an undistorted circle exists only for

The radius of the parallel corresponding to the latitude

If

Figure 4: Distribution of linear distortions in the general normal Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection

If

To conclude, it makes no sense to talk about tangent and secant projections in general, because the position of the projection plane is in no way connected to the sphere being mapped except for perspective projections. In addition, the introduction of the names tangent and secant can lead to wrong conclusions about the distribution of distortions.

It is commonly assumed that standard parallels and parallels that appear as the intersections of a developable surface and a sphere or ellipsoid coincide. In a previous paper [9], it has been shown that this is not true for azimuthal projections which are equidistant along meridians, equidistant along parallels (orthographic), or equivalent, because there is no standard parallel at all in such projections. Only some azimuthal conformal (stereographic) projections have a standard parallel, in which case it coincides with the secant parallel. Furthermore, there are azimuthal projections with two secant parallels and with infinitely many secant parallels. One can read more about this in Lapaine’s articles [9,10].

4 Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

In the transverse aspect, the central meridian is shown as a straight line. Meridians that are 90° from the central meridian form a circle. The images of the other meridians are complex curves that intersect at both poles. The distance between the images of the meridians decreases with distance from the central meridian. The image of the Equator is a straight line. The images of the other parallels are complex curves concave towards the nearer Pole. The distance between the images of the parallels decreases with distance from the Equator. Along the image of the meridian that is 90° from the central meridian, the parallels are placed at equal intervals (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: World map in the simple transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection,

Let us recall how the equations of the transverse Lambert projection are formally derived from the equations of the normal Lambert projection. First, Eq. (20) are written as follows:

and then a substitution is made:

Substitution (30) is a special case of the general transition from the normal aspect of the projection to the transverse one:

which is Formula (10) in the article by Lapaine and Frančula [11]. When the values

and then according to (29)

To get a map with the cardinal points arranged as we are used to, i.e., North is up and South is down, it is necessary to rotate the image by 90°, i.e., apply the expressions

In this way we get the equations of the simple transverse Lambert projection

Let us notice that the expression in the denominator in (34) can be equal to zero. Since

With

Eq. (34) look a little simpler

Let us calculate

This means that a map of the entire world made in the projection to which Eq. (34) are applied will be placed in a circle of radius 2 (Fig. 5).

For

For

The considerations on the transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection carried out in Section 4.1 are sufficient to achieve my goal, i.e., to apply it in further research on the Hammer projection. However, for the sake of completeness, let us briefly present the general case. If instead of the equation

In the special case for

Figure 6: World map in the general transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection,

4.3 Partial Derivatives for the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

Partial derivatives are needed to estimate projection distortions. We will focus on the special case of the transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection and Eq. (36), because we have seen the general case is not promising, while for further investigation of the Hammer projection only a simple form is needed. Let us do the math first:

After that, we can calculate the partial derivatives:

4.4 Another Form of the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection Equations and the Corresponding Partial Derivatives

Let us look for a different way to write the Lambert projection equations that would be more convenient for calculating partial derivatives. The following relation is known from trigonometry

Using (43), the equations of the transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection (36) can be written in the form

The partial derivatives obtained based on expression (44) after rearrangement are:

4.5 Third Form of the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection Equations and the Corresponding Partial Derivatives

Following Solov’ev [12]:

The partial derivatives will be:

Thus, we have three equivalent but different partial derivative notations for the simple Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection. Partial derivatives are needed to determine projection distortions. We will deal with this in the next section.

5 Standard Points in the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

At the end, let us investigate the places where the distortion is equal to zero in the simple transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection. In a previous article [7], I derived the conditions that a single point must meet to be a standard point of a map projection. Assuming

these conditions are:

and

In (54)–(56),

Since for all equivalent projections

condition (54) will be fulfilled for all

In the previous sections, we introduced four equation sets of the Lambert transverse equivalent azimuthal projection. These were Eqs. (34), (36), (44) and (49). For all these equations, we calculated partial derivatives. Among them, we choose those with which we can most easily verify conditions (55) and (56). With a little analysis, it can be determined that for this purpose Eqs. (50)–(53) will be the most convenient to use.

If

If we insert the partial derivatives (59) into (55) we get

With the assumption

we get

from which it is immediately clear that

5.1 A Simpler Way to Determine the Standard Point in the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

Since the equations of the Lambert transverse equivalent azimuthal projection can be written in the form (21), which is formally equal to the form (18), then for the Lambert transverse equivalent azimuthal projection we can write the local linear scale factors according to the model of the normal projection.

and conclude that (19) will hold for the transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection if

holds. From there,

5.2 The Simplest Way to Determine the Standard Point in the Simple Transverse Lambert Equivalent Azimuthal Projection

A third, even simpler method without additional calculations would be to apply the property of map projections according to which all aspects of a projection (normal, oblique and transverse) have the same distribution of distortions.

Transverse and oblique projections are created by reparametrization from normal aspect projections. Since the first differential form is invariant to the change of parameters [13,14], the distortion distribution will not change with the transition from normal to transverse or oblique projection. Since the normal simple Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection (20) has only one standard point located at the origin of the coordinate system, then this is also true for the transverse aspect of this projection.

The Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection is one of the seven map projections proposed by J. H. Lambert. Although it was invented many years ago, this projection is still relevant today [15–20]. Scientists publish articles about it in journals [21,22], and future scientists study it as part of their doctoral dissertations [23].

This projection is often used in the normal aspect in atlases for maps of the polar regions. The transverse aspect is commonly used for Eastern and Western Hemisphere atlas maps. When researching that projection, it was observed that the general case of a normal and transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection is not yet known in the theory of map projections. That is why the Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection was divided into a simple and a general form. Since the general case does not look promising in applications, and further research on the Hammer projection requires the simple case, it was investigated in more detail.

The equations of the simple transverse aspect can be written in several ways. Among several forms of the equations of the transverse aspect of the projection, I chose the form that is most adept at calculating the partial derivatives, which are necessary for the determination of distortions. The article presents the distribution of the local linear scale factor along the (pseudo) meridians and (pseudo) parallels and found that there is only one point where the distortion is zero.

Given that the Hammer projection was created from the simple transverse Lambert equivalent azimuthal projection, the research conducted and the results obtained can be used in future research on the Hammer projection.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bollmann J, Koch WG. Lexikon der kartographie und geomatik. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag; 2001. (In German). [Google Scholar]

2. Hrvatska E, Lambert JH. Miroslav krleža lexicographic institute. [cited 2024 Apr 1]. (In Croatian). Available from: http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=35243. [Google Scholar]

3. Frischauf J. Die abbildungslehre und deren anwendung auf kartographie und geodäsie. Teubner, Leipzig: Druck und Verlag von B.G; 1905. (In German). [Google Scholar]

4. Lambert JH. 6th Chapter: Anmerkungen und Zusätze zur Entwerfung der Land- und Himmelscharten [Notes and comments on the composition of terrestrial and celestial maps]. In: Beyträge zum gebrauche der mathematik und deren anwendung. dritter theil Berlin: Verlag der Buchhandlung der Realschule; 1772. (In German). [Google Scholar]

5. Lee LP. Conformal projections based on elliptic functions. Cartographica, Monograph no. 16, supplement no. 1 to Canadian Cartographer. 1976. Vol. 13, 128 p. [Google Scholar]

6. Rickey VF, Tuchinsky PM. An application of geography to mathematics: history of the integral of the secant. Math Mag. 1980;53(3):162–6. doi:10.1080/0025570x.1980.11976846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lapaine M. Standard points and lines in map projections. KN-J Cartogr Geogr Inf. 2024;74(2):159–67. doi:10.1007/s42489-024-00168-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Snyder JP. Map projections—a working manual. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1987. 383 p. Reprinted 1989 and 1994 with corrections. [Google Scholar]

9. Lapaine M. Standard parallel and secant parallel in azimuthal projections. Cartogr Geoinf. 2017;16(28):72–88. [Google Scholar]

10. Lapaine M. Sekushchie paralleli v azimutal’nyh proektsiyah [Secant Parallels in Azimuthal Projections]. Geod Cartogr. 2019;80(4):39–54. (In Russian). doi:10.22389/0016-7126-2019-946-4-39-54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lapaine M, Frančula N. Map projection aspects. Int J Cartogr. 2016;2(1):38–58. doi:10.1080/23729333.2016.1184554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Solov’ev MD. Matematicheskaya kartografiya. Moscow, Russia: Nedra; 1969. 286 p. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

13. Pressley A. Curvature of surfaces. In: Elementary differential geometry. London, UK: Springer; 2001. p. 123–45. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-3696-5_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jia Y-B. Surface curves and fundamental forms (Com S 477/577 Notes). [cited 2020 Nov 11]. Available from: https://faculty.sites.iastate.edu/jia/files/inline-files/surface-curves.pdf. [Google Scholar]

15. Wikipedia. Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lambert_azimuthal_equal-area_projection. [Google Scholar]

16. ArcGIS Pro. Lambert azimuthal equal-area. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/help/mapping/properties/lambert-azimuthal-equal-area.htm. [Google Scholar]

17. Wolfram Math World. Lambert Azimuthal equal-area projection. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://mathworld.wolfram.com/LambertAzimuthalEqual-AreaProjection.html. [Google Scholar]

18. GMT Community Forum. Azimuthal Lambert. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.pygmt.org/latest/projections/azim/azim_lambert.html. [Google Scholar]

19. PROJ. LAEA. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://proj.org/en/stable/operations/projections/laea.Html. [Google Scholar]

20. GMT Map Projections—GMT 6.6.0 Documentation. Azimuthal projections. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://docs.generic-mapping-tools.org/latest/reference/map-projections.html#azimuthal-projections. [Google Scholar]

21. Öztürk E. Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection. Eskişehir Tech Univ J Sci Technol A. 2024;25(3):380–9. doi:10.18038/estubtda.1410864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kerkovits K. Development of a low-distortion authalic sphere for the oblique azimuthal equal-area map projection of the spheroid. J Spat Inf Sci. 2025;2025(30):117–29. doi:10.5311/josis.2025.30.402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gilić F. Development of a geospatial data model for global land cover data storage and handling [Ph.D. thesis]. Zagreb, Croatia: University of Zagreb Faculty of Geodesy; 2025. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools