Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

3D LiDAR-Based Techniques and Cost-Effective Measures for Precision Agriculture: A Review

1 Geographic Information System (GIS) Cell, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology, Allahabad, Prayagraj, 211004, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 AIT-CSE (AIML), Chandigarh University, Mohali, 140413, Punjab, India

* Corresponding Author: Mukesh Kumar Verma. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities in GIS 3D Modeling and UAV Remote Sensing)

Revue Internationale de Géomatique 2025, 34, 855-879. https://doi.org/10.32604/rig.2025.069914

Received 03 July 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

Precision Agriculture (PA) is revolutionizing modern farming by leveraging remote sensing (RS) technologies for continuous, non-destructive crop monitoring. This review comprehensively explores RS systems categorized by platform—terrestrial, airborne, and space-borne—and evaluates the role of multi-sensor fusion in addressing the spatial and temporal complexity of agricultural environments. Emphasis is placed on data from LiDAR, GNSS, cameras, and radar, alongside derived metrics such as plant height, projected leaf area, and biomass. The study also highlights the significance of data processing methods, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), in extracting actionable insights from large datasets. By analyzing the trade-offs between sensor resolution, cost, and application, this paper provides a roadmap for implementing PA technologies. Challenges related to sensor integration, affordability, and technical expertise are also discussed, promoting the development of cost-effective, scalable solutions for sustainable agriculture.Keywords

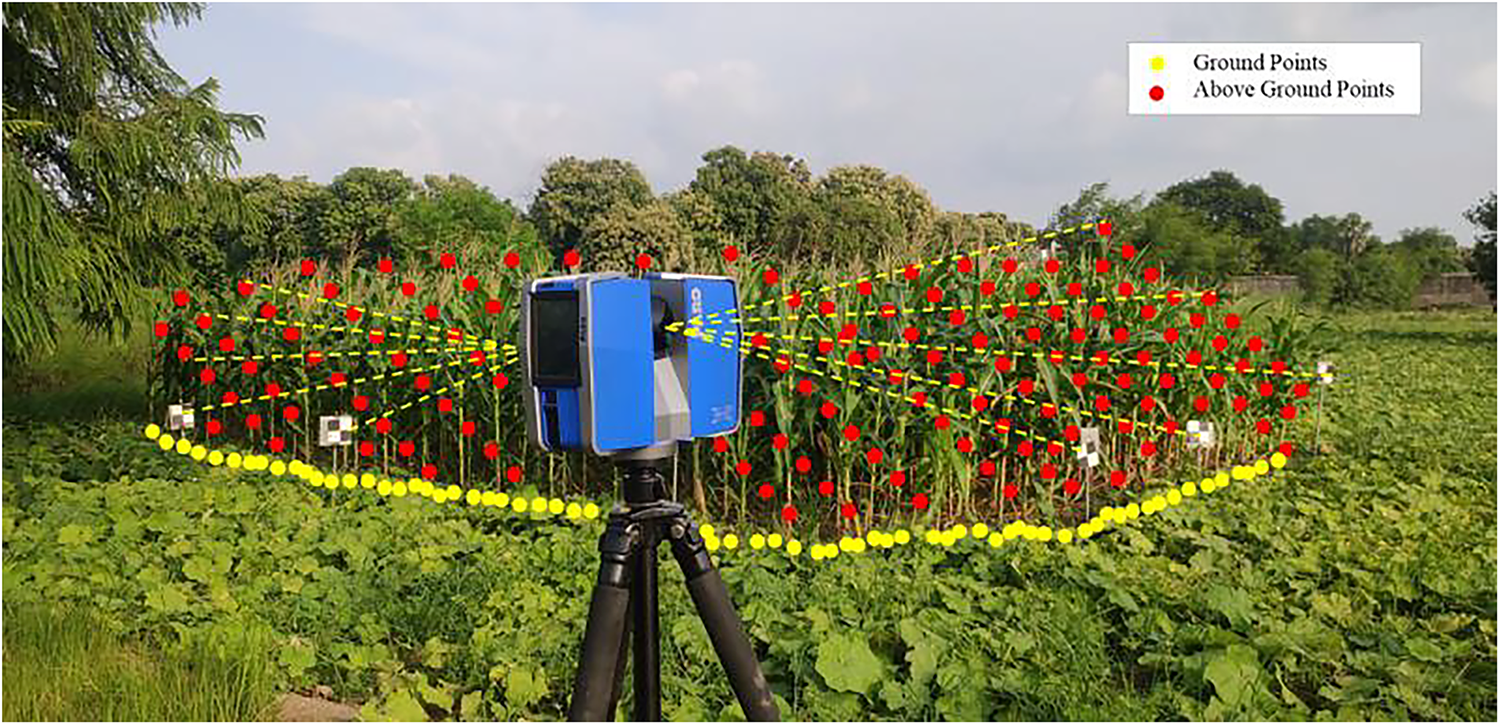

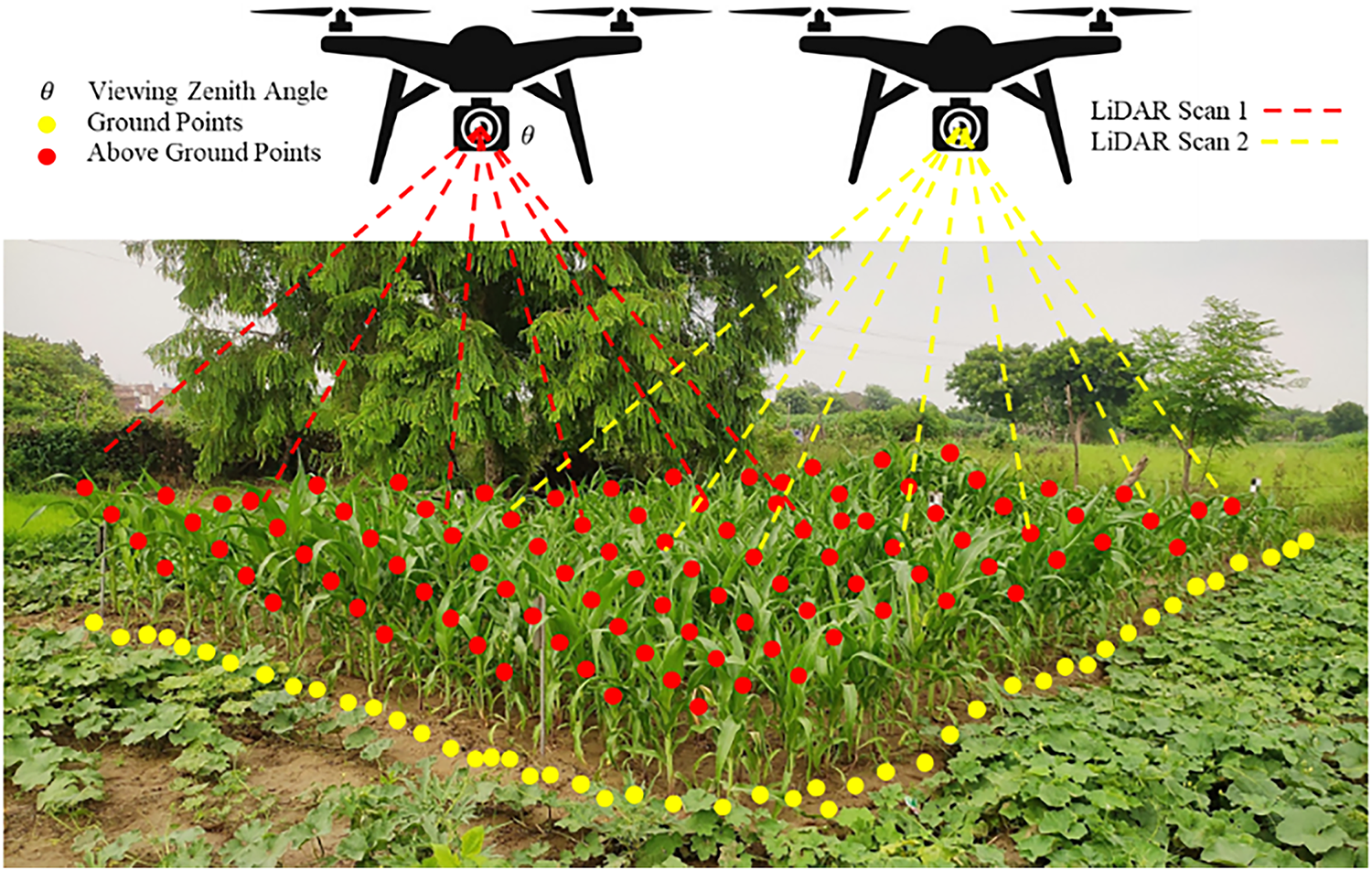

Global food consumption is projected to rise substantially by 2050, necessitating transformative alterations in agricultural practices to enhance productivity, resource efficiency, and environmental sustainability [1]. Precision agriculture (PA), driven by developments in sensor technologies, data analytics, and automation, offers a viable framework to address these challenges. Among several remote sensing technologies, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) has emerged as a powerful tool for acquiring high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) structural data of crops, enabling non-destructive, scalable, and timely monitoring of plant and field dynamics [2]. The TLS system acquires a dense 3D point cloud of the maize canopy, subsequently categorizing it into ground and above-ground points, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Configuration of Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) for the collecting of maize field data. Yellow and red dots signify ground points and above-ground points, respectively, illustrating the vertical structural profiling of maize fields by 3D LiDAR point cloud classification. Classifying points into terrestrial and aerial components is crucial for producing Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) and delineating plant structures for biomass assessment and morphological analysis

LiDAR systems operate by emitting pulsed laser beams and monitoring the time interval of their return to generate dense 3D point clouds of the surveyed region. These point clouds offer precise measurements of morphological attributes such as plant height, canopy volume, Leaf Area Index (LAI), and biomass, which are critical indicators for yield estimation, crop health assessment, and agricultural decision-making [3]. Over the past decade, significant advancements have been made in the amalgamation of LiDAR with machine learning, computer vision, and geographic information systems (GIS) to improve phenotyping, field robotics, and decision support systems.

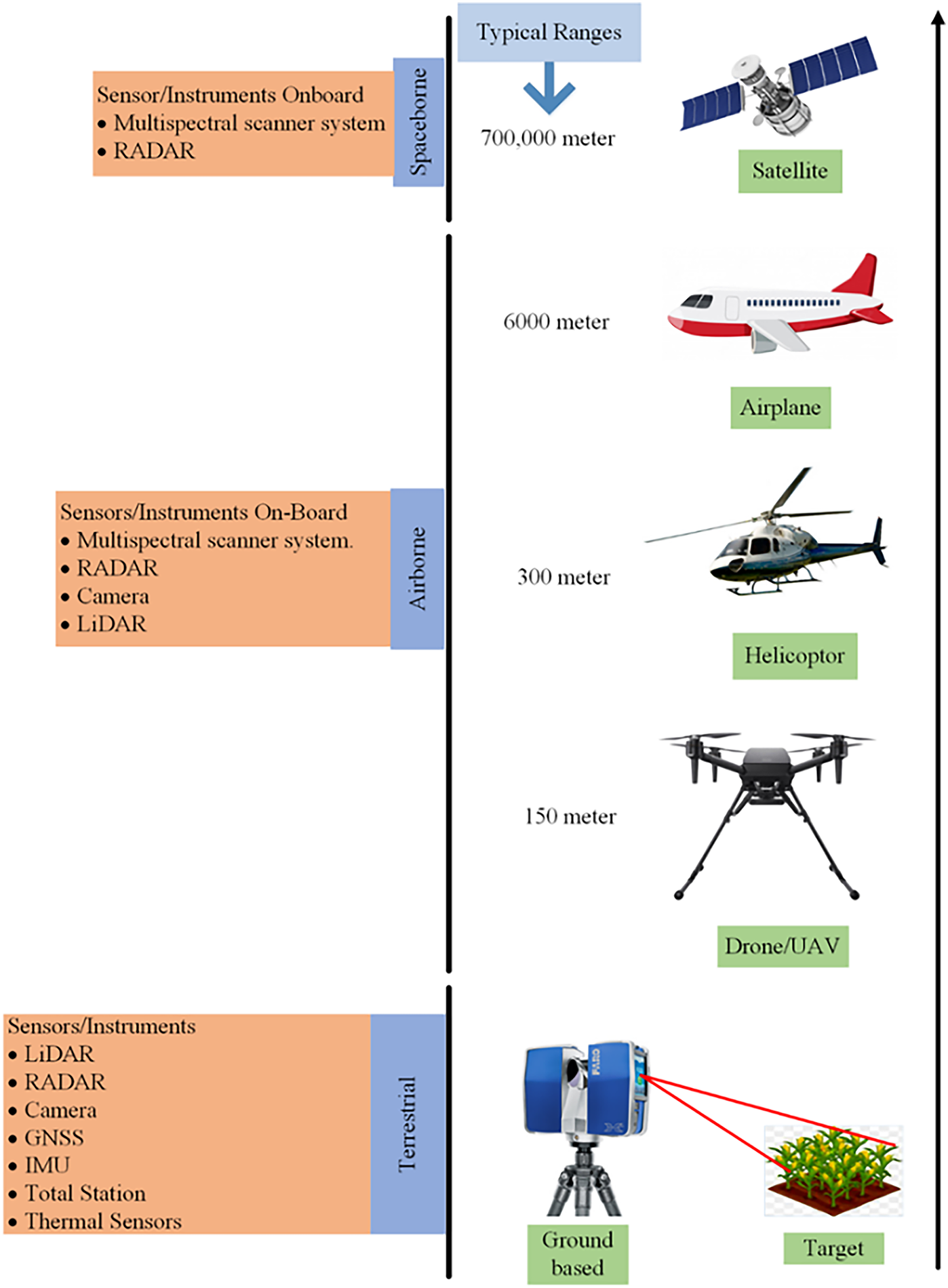

LiDAR platforms are categorized as Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS), Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), and Mobile Laser Scanners (MLS) based on their mode of deployment. ALS devices are optimal for comprehensive canopy assessment, but TLS and MLS offer precise data collection at the individual plant level, enabling high-throughput phenotyping and the evaluation of intra-field variability. The widespread application of LiDAR in agriculture is constrained by factors such as high acquisition and operational costs, sensor complexity, and data processing demands, particularly for smallholder farmers [4]. Remote sensing platforms are classified into spaceborne, airborne, and terrestrial systems, each possessing unique sensor payloads and operational altitudes, as depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Classification of remote sensing platforms according to sensor deployment altitude and operational range. Platforms encompass spaceborne (satellites), airborne (aircraft, helicopters, UAVs), and terrestrial (ground-based systems such as TLS). Each platform is outfitted with an array of sensors, including LiDAR, RADAR, multispectral scanners, and GNSS, to enable precision agriculture applications

Recent research efforts have focused on developing cost-effective, compact, and computationally efficient LiDAR solutions, including low-channel sensors, UAV-integrated systems, and open-source processing pipelines. This has enabled the democratization of LiDAR applications in Pennsylvania and their adaptation for diverse agricultural environments, including row crops and orchards.

This work presents a comprehensive synthesis of recent advances in 3D LiDAR point cloud techniques for precision agriculture, with a particular emphasis on economical and scalable approaches. It systematically categorizes applications such as crop metric estimation, field digitization, object detection, and decision support systems. The study evaluates the effectiveness and trade-offs of different LiDAR platforms—including ALS, TLS, and MLS systems—alongside associated data processing methodologies. It further integrates cost–benefit analyses of LiDAR sensors, providing practical insights into platform selection based on operational requirements and budget constraints.

A key novelty of this work lies in its explicit mapping of state-of-the-art deep learning models, including PointNet, 3D-CNN, and transformer-based architectures, to their corresponding LiDAR modalities and agricultural applications such as weed detection, canopy segmentation, biomass estimation, and disease classification. Unlike previous reviews, this study offers an implementation-focused perspective that bridges high-end and low-cost LiDAR solutions, aligning them with AI-driven analytics to enable real-time, accurate, and accessible precision agriculture systems. By identifying emerging trends and research gaps, it provides a structured roadmap for advancing LiDAR adoption from experimental trials to large-scale, field-ready deployment.

2 Classification of LiDAR Platforms

LiDAR systems utilized in precision agriculture can be categorized based on their deployment platform. The platform is crucial for determining spatial resolution, area coverage, temporal flexibility, operational cost, and suitability for certain agricultural applications. The three principal categories of LiDAR platforms are ALS, TLS, and MLS. Each technology offers unique benefits and limitations regarding sensor installation, mobility, and cost-efficiency for diverse crop monitoring scenarios.

2.1 Airborne Laser Scanner (ALS)

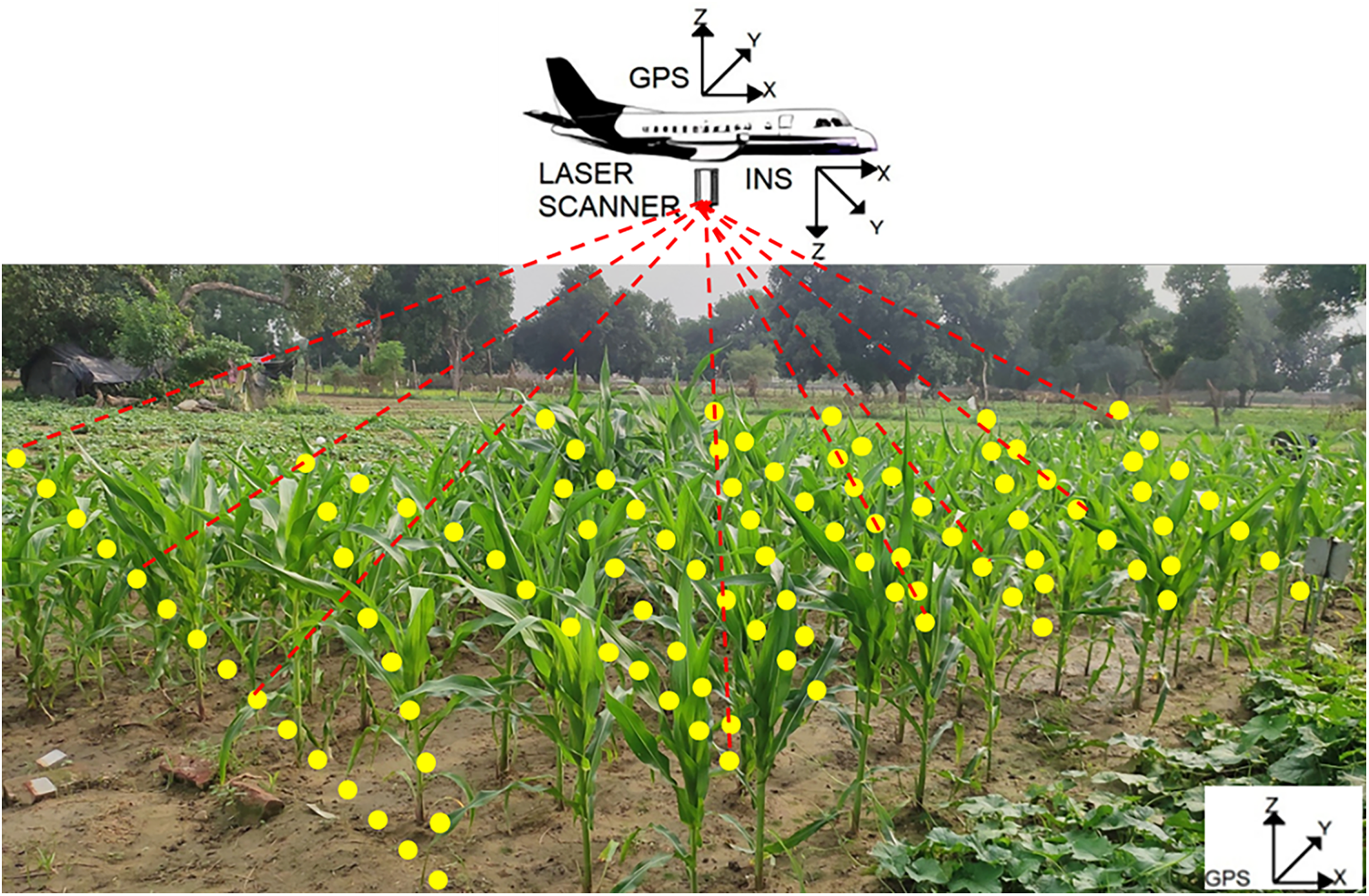

ALS systems are typically mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), drones, or manned aircraft. These systems are meticulously engineered for extensive, high-altitude surveys and are commonly utilized to get canopy-level data, such as crop height, LAI, and field topography. ALS enables rapid data acquisition across vast agricultural landscapes, making it suitable for yield prediction, health evaluation, and land surface modeling. Airborne LiDAR systems include global positioning system (GPS) and intertial navigation system (INS) for accurate georeferencing of point clouds, enabling detailed study of canopy structure and ground surface modeling, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Depiction of aerial LiDAR data collection over a corn field. The configuration comprises a laser scanner integrated with GPS and an Inertial Navigation System (INS) affixed to an airplane. The generated laser pulses (red dashed lines) impact the earth and plants, generating categorized point clouds—yellow points denote ground returns, whereas red points signify above-ground vegetation returns

ALS benefits from a bird’s-eye view (BEV) position, enabling little hindrance and large area coverage. However, the vertical resolution is sometimes inferior than that of TLS and MLS due to flight altitude, and their ability to detect understory vegetation or minor morphological features is limited. The integration of multi-return or full-waveform ALS devices improves penetration through dense canopies, while it results in increased operational costs.

Recent studies demonstrate that UAV-mounted ALS, employing sensors such as Velodyne VLP-16 or RIEGL VUX-1UAV, may attain sub-decimeter accuracy in quantifying plant height and canopy volume in crops including maize, sorghum, and sugarcane. Despite their efficacy in temporal monitoring and comprehensive mapping, ALS systems may be constrained by battery life, regulatory restrictions, and equipment costs, particularly in smallholder or resource-constrained environments.

2.2 Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS)

TLS systems are stationary, ground-based platforms generally mounted on tripods. They provide high-density 3D point clouds with millimeter-level accuracy, making them appropriate for detailed plant-level phenotyping, biomass evaluation, and canopy structure analysis. TLS is especially beneficial in experimental agriculture plots, greenhouse environments, and research applications requiring accurate extraction of structural characteristics.

TLS systems such as the FARO Focus X330, Leica ScanStation, and RIEGL VZ-series are commonly utilized in studies evaluating the morphological traits of individual plants or small plots. Their ability to scan from fixed positions allows for repeated evaluations throughout critical growth stages, hence providing accurate monitoring of crop development over time.

Despite the accuracy of TLS systems, they are hampered by a restricted field of vision, shadowing effects, and the labor-intensive requirement for human repositioning or registration during repeated scans. The cost and operational complexity of TLS make it less viable for widespread use; yet, it is highly advantageous for ground truthing, model calibration, and validation research.

2.3 Mobile Laser Scanner (MLS)

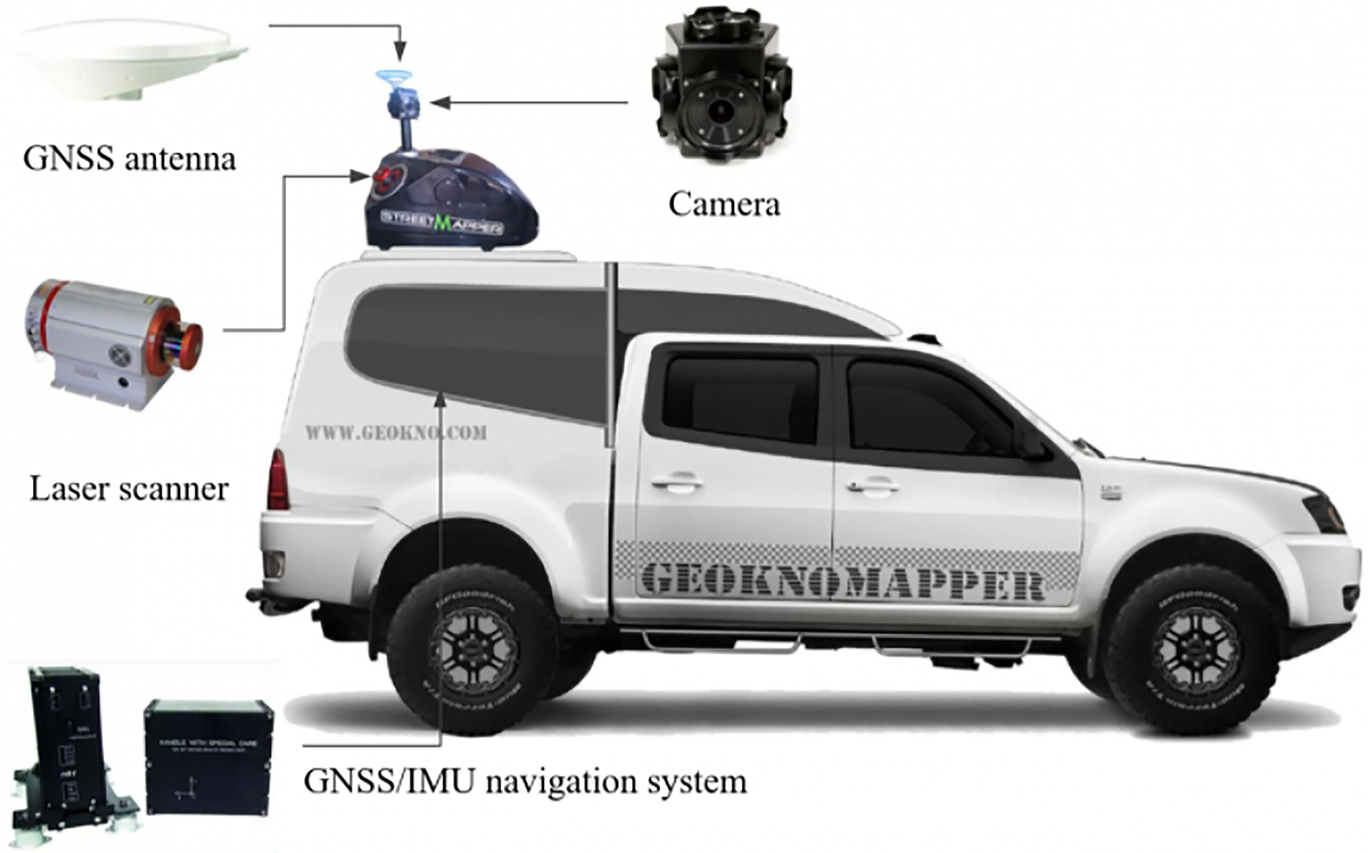

MLS systems are mounted on movable platforms such as tractors, rovers, backpacks, or handheld devices. These systems offer a balance between resolution and mobility, making them suitable for field-scale applications with modest geographic coverage and considerable versatility. MLS has greater flexibility than TLS and improved resolution compared to ALS at the plant level, making it an effective solution for real-time crop monitoring, inventory assessment, and navigation tasks in orchards or row-crop farms. A vehicle-based Mobile LiDAR System integrates GNSS, LiDAR, and imaging sensors to facilitate high-resolution geospatial data acquisition in various field environments as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Configuration of a Mobile LiDAR System (MLS) mounted on a vehicle, illustrating key components including a GNSS antenna, camera, laser scanner, and GNSS/IMU navigation system for geospatial data acquisition [5]

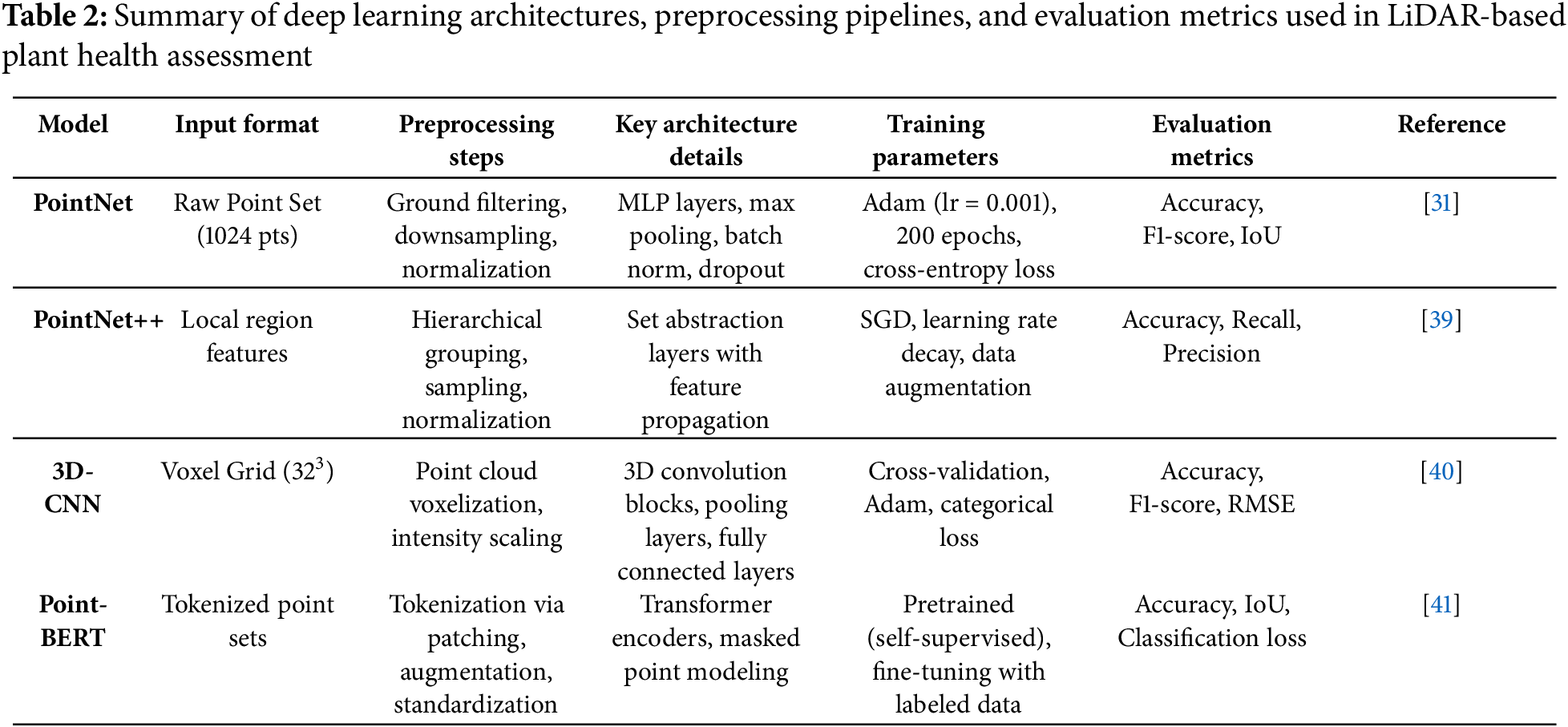

Recent advancements in miniature LiDAR modules such as Livox Horizon, Hesai QT64, and solid-state LiDAR units are enabling affordable, lightweight deployments on UAVs and autonomous ground vehicles. For example, Ref. [6] demonstrated real-time crop row navigation using a solid-state LiDAR, GNSS, and monocular camera fusion, achieving sub-decimeter accuracy at 10 Hz update rates on vineyard rows. These low-power units, when paired with lightweight SLAM frameworks, significantly reduce system complexity and power consumption. Diverse UAV-LiDAR scanning approaches, encompassing oblique and nadir angles, significantly affect point distribution and ground detection accuracy, as demonstrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: UAV-based LiDAR scanning configuration for maize field monitoring. The image illustrates two scanning strategies: oblique and nadir scanning angles. Laser pulses (red and yellow dashed lines) generate classified 3D point clouds where red dots represent above-ground vegetation points and yellow dots indicate ground-level returns. The pitch angle (θ) affects the point density and coverage of the scanned area

Frequently employed MLS include the SICK LMS400/511, Velodyne HDL-32E, Hokuyo UTM-30LX, and RIEGL VZ-400. These devices can operate while traversing the field, enabling real-time scanning and reducing the need for post-alignment. The MLS is increasingly integrated with agricultural robots and autonomous ground vehicles for precision tasks, like as trimming, fertilizer application, and disease diagnosis.

The principal drawbacks of MLS systems include sensor vibration, motion-induced distortions, and obstruction from dense vegetation, all of which can undermine point cloud quality. Nonetheless, its cost-effectiveness, scalability, and compatibility with AI-driven systems position MLS as a rapidly advancing field in smart agriculture technology (Table 1).

3 Applications of LiDAR in Crop Cultivation

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) has rapidly emerged as a crucial component of the digital agricultural toolset, enabling non-invasive, high-resolution mapping of crop structure and field conditions. LiDAR systems generate dense 3D point clouds by emitting laser pulses and measuring the time delay of their return, thereby capturing intricate spatial information such as plant height, canopy structure, row spacing, and surface elevation. This data supports numerous applications aimed at optimizing crop development, enhancing input efficiency, and improving output predictability.

One of LiDAR’s most notable features is its ability to function under diverse lighting and weather conditions, making it highly reliable for field-level data acquisition. LiDAR, utilized on terrestrial, aerial, or mobile platforms, provides consistent and repeatable measurements crucial for multi-temporal crop monitoring, phenotyping, and field variability assessment [26].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms facilitate the automatic classification of plants, evaluation of health, detection of weeds, and yield calculation utilizing LiDAR data. Machine learning models employing LiDAR-derived features enable real-time decision-making, while deep learning frameworks—such as PointNet and 3D convolutional neural networks—have enhanced the segmentation of complex canopies and the detection of structural anomalies [27]. These sophisticated approaches convert raw LiDAR data into actionable agronomic insights, significantly reducing the need for manual data analysis.

Furthermore, the amalgamation of LiDAR with additional sensing technologies—such as multi-spectral, hyperspectral, and thermal imaging—has broadened its range of applicability. This multi-sensor integration enables comprehensive monitoring that accounts for both structural (e.g., canopy volume) and physiological (e.g., chlorophyll content, water stress) attributes, providing a holistic view of crop performance [28].

3.1 Crop Monitoring and Management

LiDAR has emerged as an essential sensing instrument in modern precision agriculture for evaluating crop development and enabling site-specific management strategies. Its ability to generate high-resolution, three-dimensional models of vegetation enables the precise evaluation of critical structural parameters, such as plant height, canopy volume, row spacing, and leaf angle distribution. These measurements are essential indicators of crop health, growth uniformity, and stand establishment, and their accurate evaluation is vital for informed agronomic decision-making [29].

In agricultural crops including maize, wheat, and soybean, LiDAR enables plot-scale monitoring of spatial variability, identifying anomalies such as uneven emergence, lodging, or regions impacted by pests. This spatial data enables the creation of prescription maps for variable-rate applications (VRA) of water, fertilizers, and pesticides, improving resource efficiency and minimizing environmental impact. Unlike passive imaging systems, LiDAR functions actively and is less influenced by ambient light conditions, making it suitable for both daytime and nighttime applications, as well as various weather conditions.

In orchards and vineyards, marked by significant variety in structural complexity and plant design, LiDAR excels in row-based monitoring and individual plant assessment. MLS mounted to land vehicles or UAVs may traverse rows and capture detailed 3D canopy profiles, enabling prompt evaluation of plant health, pruning needs, and potential yield zones. These measures offer site-specific interventions, like differential irrigation, pest management, or growth regulation therapies [30].

Moreover, the repeatability and automated features of LiDAR make it ideal for multi-temporal monitoring, enabling the observation of crop growth during phenological stages. This facilitates the integration of LiDAR into decision support systems (DSS) that provide actionable insights to farmers and agronomists. Due to decreased sensor costs and improved accessibility of processing pipelines, LiDAR is increasingly employed as a standard monitoring tool in both research and commercial agriculture.

3.1.1 Plant Health Assessment, Maintenance and Disease Detection

Monitoring plant health and early disease identification are essential for maximizing agricultural output and minimizing losses. LiDAR technology, first used for structural analysis, is increasingly applied in plant health diagnostics due to its ability to gather detailed 3D canopy architecture and laser reflection intensity. Changes in plant physiology—such as chlorosis, wilting, or biomass reduction—often lead to noticeable alterations in canopy structure and laser backscatter characteristics. Canopy thinning and uneven leaf orientation can be discerned by measurements like point cloud density and surface curvature [31].

To improve diagnostic accuracy, LiDAR is frequently combined with hyperspectral, multispectral, or RGB imaging, creating a multi-modal sensing framework. LiDAR provides spatial and structural precision, while spectrum sensors yield critical physiological and biochemical information, such as chlorophyll concentrations and signs of thermal stress. This integration enables the detection of structural and functional disease symptoms before they become apparent to the naked eye.

Techniques such as voxel-based modeling, radiometric calibration, and intensity normalization enhance LiDAR’s sensitivity to subtle changes in plant morphology, facilitating early disease detection and stress evaluation. These methods are particularly effective when combined with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), enabling flexible, repeated data collection over large areas with high spatial resolution [32].

Furthermore, advanced deep learning models, including 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs), PointNet++, and transformer-based architectures, have been engineered to classify healthy and unhealthy plants directly from LiDAR point clouds or integrated datasets [33]. These models automate the identification of disease symptoms and anomalies with high accuracy, enabling real-time alerts and targeted crop management. The implementation of intelligent systems is crucial for shifting from reactive to preventive crop management within the framework of smart agriculture.

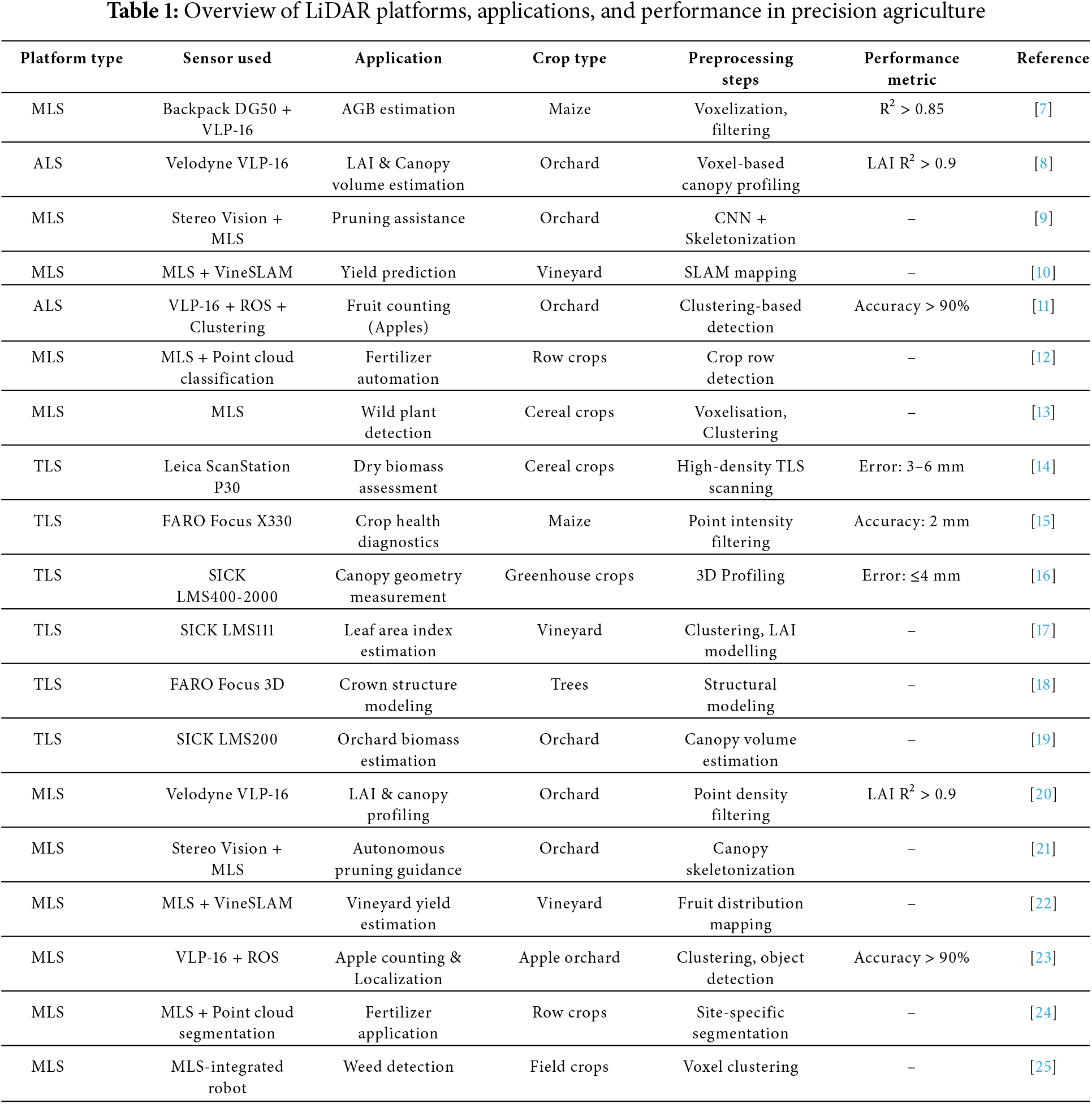

Recent advancements in LiDAR-based plant phenotyping have increasingly employed deep learning architectures such as PointNet [34], PointNet++ [35], and 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs) [36] for plant health assessment, owing to their ability to effectively capture the spatial and structural characteristics of 3D point clouds. To ensure reproducibility and promote model transparency, we report comprehensive implementation parameters based on the reviewed literature. Standard preprocessing workflows typically involve ground point removal using Cloth Simulation Filtering (CSF) [37] to isolate canopy and plant structures, voxel downsampling to a spatial resolution of 0.05 m to reduce computational complexity while retaining geometric detail, and intensity normalization to mitigate inter-scan variability and sensor-dependent biases. In PointNet-based classifiers, input point sets are generally sampled to 1024 points per instance and processed through multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) incorporating batch normalization, ReLU activation functions, and dropout regularization, with training conducted using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001) and categorical cross-entropy loss. Conversely, 3D-CNN-based approaches transform point clouds into voxelized occupancy grids—commonly at a resolution of 32 × 32 × 32—before feature extraction using convolutional blocks, followed by max-pooling and fully connected layers, with 5-fold cross-validation applied to enhance robustness and generalizability. Performance evaluation across the surveyed studies typically reports accuracy, F1-score, recall, and Intersection over Union (IoU), reflecting both classification precision and spatial segmentation quality. The methodological details, along with references to key studies employing each architecture, are summarized in Table 2, which also outlines the preprocessing and validation strategies used in the reviewed works in alignment with emerging standardized model reporting protocols [38]. Such methodological clarity is essential for interpreting model performance in LiDAR-based phenotyping applications and for guiding future research workflows aimed at improving plant health monitoring and advancing precision agriculture practices.

3.1.2 Weed Detection and Fertilizer Application

Efficient weed management and precise fertilizer application are pivotal components of sustainable agricultural practices. In recent years, LiDAR technology has emerged as a critical enabler in both domains, offering non-destructive, structure-based plant differentiation directly in the field. Unlike spectral sensing systems, which rely primarily on color or reflectance variations, LiDAR captures detailed three-dimensional structural parameters—including plant height, canopy width, leaf orientation, and volumetric attributes—that often suffice to distinguish crops from weeds, even during early developmental stages when spectral differences are minimal [42].

Researchers have developed robust systems for automated weed detection and selective herbicide application by leveraging object segmentation algorithms and traditional machine learning classifiers—such as Random Forests, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), and Support Vector Machines (SVM)—applied to sensor-derived data. For example, Ref. [43] compared RF, SVM, and k-NN for detecting weeds in an Australian chili field, achieving accuracies exceeding 90%, and designed a real-time weed detection system using Random Forest that enabled variable-rate herbicide application. These approaches target non-crop vegetation exclusively, thereby significantly reducing pesticide usage and minimizing environmental impacts.

Simultaneously, LiDAR-derived canopy-structure metrics—such as height, density, and leaf area index—provide valuable indicators of nutrient uptake efficiency and plant vigor. When integrated with prescription maps and variable-rate technology (VRT), these data enable spatially targeted fertilizer application, thereby reducing over-application and subsequent nutrient leaching, all while enhancing yield potential. Contemporary reviews affirm that LiDAR offers highly accurate measurements of canopy height and density, facilitating the generation of prescription maps for precision fertilizer application and contributing to improved environmental and production outcomes.

Moreover, Ref. [44] emphasize that real-time VRT systems crucially depend on accurate acquisition of plant canopy and soil data. These systems adjust fertilizer rates in correspondence with crop variability, thereby enhancing nutrient use efficiency and mitigating environmental impacts.

MLS, typically affixed to tractors or autonomous robots, provide real-time data collection and actuation, hence rendering precise weeding and fertilizer automation feasible at commercial sizes. These applications not only save input expenses but also enhance agroecological sustainability by reducing non-target effects and optimizing nutrient use efficiency.

Monitoring crop growth dynamics during various phenological stages is crucial for optimizing agronomic treatments and detecting periods of stress or atypical development. LiDAR technology, particularly within a multi-temporal context, provides exceptional accuracy in documenting the structural development of crops across time. By consistently surveying the same area at specified growth intervals, researchers and practitioners can generate comprehensive growth trajectories and observe geographic variability in development [45].

Essential morphological metrics obtained from LiDAR point clouds—such as plant height, canopy volume, and LAI—act as indicators of growth rate, vegetative vigor, and biomass accumulation. These measures can reveal growth-limiting conditions like water stress, nutrient insufficiency, lodging, or disease incidence, frequently before the manifestation of visible signs [46,47]. In this setting, LiDAR facilitates early warning systems that initiate prompt interventions, minimizing yield loss and enhancing resource efficiency.

In addition to crop management, LiDAR-based growth monitoring serves as an effective instrument for high-throughput phenotyping in plant breeding programs. By capturing detailed three-dimensional structural data, LiDAR enables breeders to quantify phenotypic variables such as growth rate, canopy architecture, and plant uniformity across thousands of individual plants and multiple developmental stages with high temporal and spatial resolution. This capability accelerates the identification and selection of genotypes exhibiting favorable traits under diverse environmental conditions [48,49]. Field-deployed LiDAR systems—ranging from tractor-mounted sensors to autonomous ground robots—allow repeated, non-destructive measurements, producing heritable and stress-sensitive structural metrics that enhance breeding efficiency [50,51].

3.1.4 Above Ground Biomass and Yield Estimation

Precise calculation of above-ground biomass (AGB) and crop yield is essential for evaluating crop productivity, carbon sequestration capacity, and input-use efficiency. Conventional biomass monitoring frequently necessitates destructive sampling, rendering it labor-intensive, time-consuming, and impracticable for large-scale applications. Conversely, LiDAR provides a non-invasive, scalable option by facilitating high-resolution three-dimensional characterization of crop structure.

Biomass estimation using LiDAR generally follows a structured workflow that begins with pre-processing steps such as noise removal, ground point extraction—often using algorithms like the Progressive Morphological Filter (PMF) [52] and voxelization for volume approximation [53]. Feature extraction typically focuses on geometric descriptors including plant height, canopy volume, surface area, and point density metrics, which have been shown to correlate strongly with above-ground biomass in various crops [46]. These features are then integrated into machine learning models such as Random Forest [54], Support Vector Regression (SVR) [55], or deep neural networks. More recent approaches employ voxel-based 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs) [56] and raw point-based architectures such as PointNet, depending on the input data representation. Model performance is commonly assessed using regression metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (R2), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), enabling fair comparison across datasets, crop species, and sensing conditions [57].

LiDAR-derived structural attributes—such as canopy height, volume, surface area, and plant density—exhibit a substantial correlation with above-ground biomass (AGB) and yield across diverse crop species, including maize, wheat, sugarcane, and orchards. Geometric parameters are derived from point cloud data and can be consolidated at the plant, plot, or field level to deduce biomass accumulation patterns.

Researchers have devised many regression models, including linear, nonlinear, and allometric types, to translate structural measurements into quantitative biomass and yield estimations, frequently utilizing field-calibrated coefficients. Recently, ML algorithms—such as Random Forests, Support Vector Regression, and Artificial Neural Networks—have exhibited superior predictive accuracy by elucidating intricate, non-linear correlations between LiDAR features and ground truth biomass data ([58]).

These models have been effectively used in both research plots and operating farms, facilitating real-time production monitoring, decision support for harvesting, and site-specific management planning. Furthermore, when integrated with multispectral indices like NDVI or PRI, LiDAR-derived estimations enhance robustness by amalgamating structural and physiological markers of crop condition [59].

3.2 Soil Analysis and Management

Although LiDAR technology is mostly utilized for analyzing vegetation and canopy structure, it is also essential for terrain modeling and soil management in precision agriculture. The elevated spatial resolution and precision of LiDAR-derived elevation datasets give critical insights into topographic variability, which substantially affects soil characteristics, hydrology, and agricultural productivity.

LiDAR facilitates the creation of Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and Digital Terrain Models (DTMs), which are essential for soil mapping, erosion modeling, drainage analysis, and field zoning. These models facilitate the identification of runoff channels, low-lying accumulation zones, and high-risk erosion areas, enabling farmers to adopt site-specific conservation strategies like as contour plowing, grass streams, or terracing. In heterogeneous environments, LiDAR’s accuracy enhances the delineation of soil types and enables precise distribution of resources such as water, fertilizers, and soil additives.

Moreover, whether combined with multispectral, hyperspectral, or in-situ sensor data, LiDAR facilitates the indirect evaluation of soil moisture, nutrient availability, and variability in soil texture. The integration of several data sources, frequently analyzed using machine learning techniques, improves the comprehension of spatiotemporal soil dynamics and facilitates real-time monitoring of soil health.

3.2.1 Soil Mapping and Classification

LiDAR-generated Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) are essential instruments for soil mapping and categorization in precision agriculture. LiDAR provides high-resolution representations of surface elevation and bare-earth topography, facilitating precise modeling of field slope, aspect, elevation gradients, and micro-topographical variations, which are essential factors influencing soil distribution, water movement, and erosion risk.

These terrain models facilitate the definition of management zones based on hydrological dynamics and soil formation processes. LiDAR-derived slope maps can delineate areas susceptible to erosion, whilst aspect and curvature analyses facilitate the identification of zones vulnerable to drought or potential waterlogging. Such insights provide site-specific soil interventions, encompassing contour farming, buffer strip installation, or targeted drainage enhancements.

Furthermore, the integration of LiDAR data with terrestrial soil surveys, remote sensing photography, or electromagnetic induction (EMI) data improves the classification of soil types and textural variations within fields. Machine learning algorithms utilized on integrated information can forecast attributes such as soil organic matter, pH, salinity, and compaction zones, hence guiding customized agronomic operations [58].

LiDAR is particularly beneficial in areas with diverse terrain, where conventional soil surveys may be constrained by accessibility or resolution. LiDAR enhances the spatial precision of soil classification maps, facilitating improved input allocation, minimizing environmental effect, and aiding in the long-term monitoring of soil health.

3.2.2 Soil Moisture Content and Nutrition Analysis

While LiDAR technology cannot directly measure soil moisture or nutrient levels, it plays a crucial role in their indirect evaluation by analyzing the structure and morphology of flora and topography. LiDAR-derived metrics, including canopy height, volume, and plant density, act as indicators for assessing the physiological responses of crops to water or nutrient stress. Regions characterized by scant canopies, diminished biomass, or irregular growth patterns in LiDAR point clouds frequently align with locations exhibiting inadequate soil moisture retention or nutritional deficits [60].

The amalgamation of LiDAR with thermal imaging, multispectral, or hyperspectral sensors significantly improves the identification of moisture-induced stress. LiDAR can capture structural deformations due to dehydration—such as leaf bending and canopy wilting—while thermal sensors detect surface temperature variability, and spectral data provide indices like the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) and chlorophyll content as physiological indicators of stress [61]. These combined datasets enable a more comprehensive and accurate evaluation of crop-water relationships and nutrient uptake efficiency.

Moreover, LiDAR-derived Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) are crucial for simulating water flow pathways, drainage patterns, and potential pooling zones within agricultural fields. When integrated with in-situ soil moisture probes or microwave remote sensing data, these models provide detailed insights into hydrological dynamics that govern root-zone moisture availability [62]. The fusion of such heterogeneous datasets—facilitated by machine learning algorithms—enables spatially explicit soil moisture predictions, thereby supporting site-specific irrigation and fertilization strategies. This integrative approach has been shown to improve water use efficiency and enhance crop yields by aligning management decisions with fine-scale variability in soil–water conditions [63].

4 LiDAR Applications in Crop Harvesting

The utilization of LiDAR in crop harvesting has markedly increased in recent years, propelled by the necessity for accuracy, automation, and resource efficiency in contemporary agriculture. LiDAR’s capacity to acquire high-resolution three-dimensional structural data renders it an essential instrument for informing harvesting decisions and streamlining post-harvest processes. Its use encompasses the complete harvesting cycle—from assessing crop ripeness and predicting production to facilitating robotic harvesting and analyzing field conditions after harvest.

4.1 Crop Maturity and Yield Prediction

LiDAR technology is essential for the non-invasive evaluation of crop maturity, facilitating accurate observation of structural changes that transpire as crops near senescence. As plants grow, quantifiable changes, including a reduction in canopy volume, modification in leaf orientation, and a drop in plant height, become evident in the 3D point cloud data obtained from LiDAR systems [64]. These geometric markers serve as reliable indicators of physiological development, aiding in the determination of optimal harvest windows.

Advanced LiDAR technologies, specifically TLS and MLS, provide millimeter-level precision, rendering them appropriate for monitoring subtle morphological changes over time. The collection of these datasets at various growth phases establishes the foundation for multi-temporal phenotyping, essential for forecasting maturity levels and estimating yield [65].

Moreover, the amalgamation of LiDAR data with AI and ML algorithms has markedly enhanced the precision of yield predictions. AI methods, including Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and deep neural networks, can be trained on data extracted from point clouds—such as canopy density, height variability, and volumetric indices—to model associations with biomass and grain yield [58]. These models not only reduce the need for destructive sampling but also enable in-season yield prediction, allowing farmers to optimize harvest logistics and market planning.

4.2 Autonomous Harvesting Systems

The integration of LiDAR technology into autonomous harvesting systems is rapidly transforming field operations by enhancing machine perception and decision-making. LiDAR serves as a core sensor in these systems for obstacle detection, plant and fruit localization, as well as trajectory planning—empowering robots and autonomous vehicles to carry out harvesting tasks with minimal human intervention [66]. By generating dense 3D point clouds of the environment, LiDAR supports accurate mapping of crop rows, individual plant geometry, and fruit clusters—even in cluttered or partially occluded scenes [67,68].

The latest generation of autonomous agricultural robots increasingly employs miniature LiDAR sensors equipped with real-time localization and obstacle avoidance capabilities. Recent advancements highlight the integration of point cloud-based scene understanding with embedded edge processors—such as NVIDIA Jetson and Intel Movidius—to enable continuous 24/7 operation. Furthermore, state-of-the-art systems adopt multi-sensor simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) strategies that combine LiDAR, thermal imaging, and inertial sensors, ensuring robust positioning even in GPS-degraded environments.

In orchard environments, MLS mounted on unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) or robotic arms enable real-time scanning and enhanced situational awareness. These platforms utilize SLAM and point cloud segmentation algorithms to autonomously navigate between crop rows, identify harvestable produce, and perform precise manipulations such as fruit picking or branch pruning. When integrated with complementary vision sensors—such as RGB or hyperspectral cameras—LiDAR improves the detection of occluded fruits and facilitates ripeness assessment, thereby significantly enhancing harvesting efficiency [69].

The latest generation of autonomous agricultural robots now leverages miniaturized solid-state LiDARs integrated with low-cost GNSS and monocular cameras to enable real-time 3D perception. In a recent study, Ref. [70] validated a real-time, low-power perception system for crop row navigation, achieving consistent tracking even under partial occlusions and variable lighting condition.

Recent developments in deep learning have further strengthened these systems. CNNs and PointNet-based architectures have been used to extract geometric features of fruits like apples, peaches, and citrus from LiDAR point clouds, enabling robotic arms to compute grasping poses for gentle and accurate picking.

4.3 Post-Harvest Quality Assessment

Post-harvest assessment is a critical yet often underutilized phase of the crop production cycle, where LiDAR technology is gaining increasing relevance. Following harvest, terrestrial or mobile LiDAR systems can be deployed to evaluate residual biomass, stubble height, and field surface conditions, providing essential insights for optimizing tillage operations, residue management, and preparation for subsequent planting cycles [71]. The high-resolution 3D point clouds generated by these systems enable accurate quantification of remaining plant structures and soil surface roughness. For example, precise measurements of stubble height and density can inform decisions regarding mechanical residue removal, mulching, or no-till practices [72]. Such measurements also contribute to estimates of carbon sequestration potential and nutrient cycling, particularly in the context of conservation agriculture [73].

In addition, post-harvest LiDAR surveys can identify wheel ruts, compaction zones, and erosion features—factors that directly affect soil health and future crop emergence. Advances in autonomous ground vehicles and robotic platforms have enabled the integration of automated LiDAR-based analytics for real-time assessment and spatial mapping of harvesting efficiency across extensive fields. These capabilities not only improve operational efficiency but also support sustainability objectives by enabling more uniform residue distribution and minimizing soil disturbance.

The capacity to rapidly acquire and analyze spatially explicit post-harvest data positions LiDAR as a key component in closed-loop agricultural systems, where insights from one season inform input optimization and management strategies for the next. This integration ultimately supports more resilient and resource-efficient farming systems.

LiDAR technology provides high spatial accuracy and dense three-dimensional (3D) structural information, offering significant potential for precision agriculture. However, its large-scale adoption—particularly in resource-constrained settings such as smallholder and low-income farming systems—has been impeded by high initial costs, complex data processing requirements, and the need for specialized technical expertise. Recent technological developments, including the availability of low-cost LiDAR sensors, open-source data processing pipelines, and accessible deployment platforms, are contributing to the democratization of LiDAR technologies for agricultural applications.

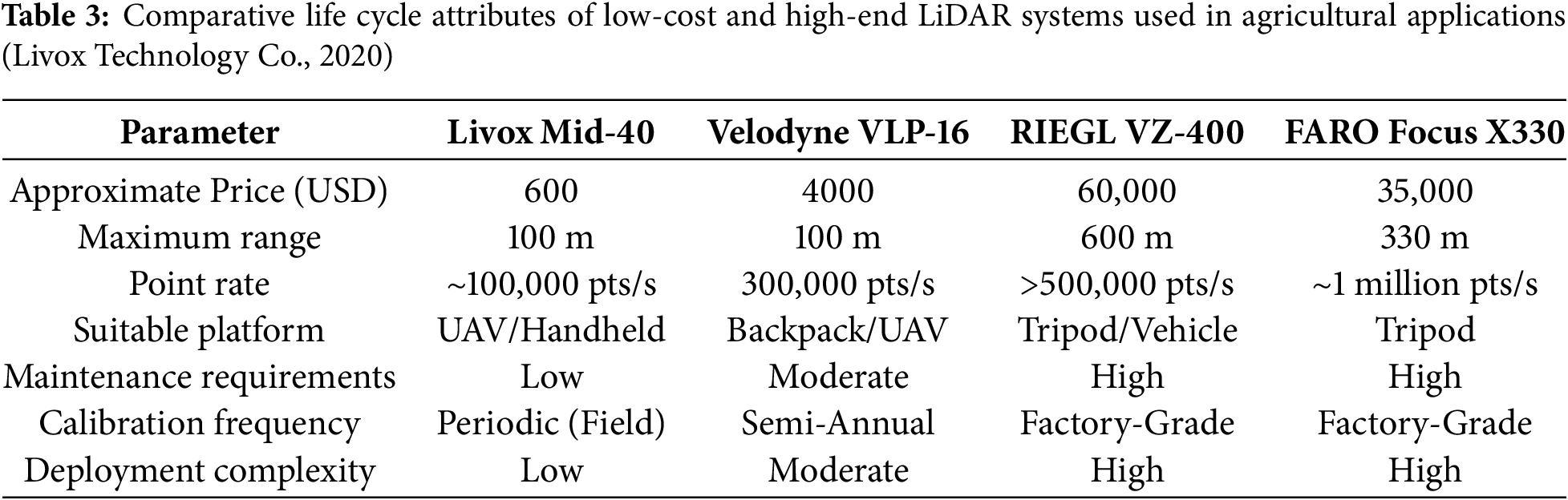

To support informed decision-making regarding LiDAR adoption in agricultural applications, a life cycle cost analysis was performed [74]. This analysis compared low-cost LiDAR sensors—such as the Livox Mid-40 and Velodyne VLP-16—with high-end industrial-grade systems, including the RIEGL VZ-series and FARO Focus X330. The comparison considered both technical specifications (e.g., range accuracy, beam divergence, scan rate) and economic factors (e.g., purchase price, maintenance costs, operational lifespan). Table 3 presents a consolidated summary of these systems, highlighting trade-offs between performance and affordability to guide selection for specific agricultural contexts.

While industrial-grade systems offer superior range, point density, and environmental robustness, low-cost alternatives are adequate for numerous precision agriculture tasks, such as plant height estimation, canopy volume calculation, and above-ground biomass assessment [15,75].

Empirical studies have demonstrated that low-cost LiDAR systems, particularly the Livox Mid-40 and Velodyne VLP-16, can achieve reliable accuracy in agricultural applications despite their comparatively lower point densities [76,77]. For example, plant height estimations using these sensors have achieved root mean square error (RMSE) values between 0.03–0.06 m, while biomass prediction models based on their data have reported coefficients of determination (R2) exceeding 0.85. These performance metrics underscore their suitability for diverse agricultural contexts, particularly in smallholder farming systems where field sizes typically range from 0.2 to 2 ha. In such settings, the extended range or ultra-high-density scanning capabilities of high-end terrestrial laser scanners (TLS) are often unnecessary. Instead, the Livox and VLP-16 platforms provide sufficient spatial resolution and coverage for tasks such as field-level crop monitoring, early stress detection, and precision variable-rate input management.

These sensors are also highly applicable in pilot-scale deployments and academic research, where they can be effectively employed to generate training datasets, validate algorithmic models, and conduct cost-effective phenotyping experiments [7]. When evaluating the feasibility of LiDAR systems for agriculture, it is critical to consider not only initial acquisition cost but also the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)—which includes recurring and context-specific expenditures such as sensor maintenance, calibration cycles, power system compatibility, personnel training, and data processing tools.

Environmental durability—including resilience to dust, heat, and mechanical vibrations—as well as multi-season reusability across different crop types, are also key factors influencing cost-effectiveness. For instance, the Livox Mid-40 is particularly well-suited for UAV-based surveys over small agricultural plots due to its compact form factor, low power consumption (<10 W), and minimal calibration requirements (Livox Technology Co., 2020). Similarly, the Velodyne VLP-16, though more expensive, excels in dynamic field conditions, especially when mounted on rovers or mobile platforms. Its compatibility with real-time Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) and ability to integrate with other sensors (e.g., GNSS, IMUs) make it highly suitable for autonomous field operations [58].

In contrast, high-end systems such as the RIEGL VZ-series and FARO Focus X330 incur significantly higher TCO due to requirements for factory-grade calibration, reliance on proprietary software, and the need for skilled operators. These systems are therefore more appropriate for large-scale commercial agriculture, high-throughput phenotyping, and advanced research applications such as digital twin modeling [78].

6 Progress Made, Need and Challenges

Its integration with machine learning, robotics, and multi-sensor platforms has enhanced capabilities for biomass estimation, disease detection, yield forecasting, and autonomous navigation. Over the past decade, LiDAR has become an essential non-destructive sensing technology in precision agriculture, enabling high-resolution monitoring of crop structure, soil properties, and plant health.

However, most applications have been demonstrated in controlled environments—such as research plots, greenhouses, or institutional stations—where variables like lighting, occlusion, and terrain irregularity are minimized [79]. This contrasts sharply with commercial farming, where heterogeneous terrain, dense canopies, and physical obstructions (e.g., irrigation lines, trellises, weeds) complicate consistent point-cloud acquisition [80,81].

Field deployments face multiple technical and operational constraints. Low-cost LiDAR sensors, while more accessible, are prone to calibration drift and data degradation under dust, humidity, vibration, and extreme temperatures. Large-scale data acquisition generates substantial computational loads, limiting real-time analytics, particularly in rural areas with poor connectivity and unstable power supply. Occlusion in dense crops, motion distortion on mobile platforms, and environmental sensitivity further degrade accuracy. While multi-view scanning and SLAM-based alignment improve completeness, they increase hardware and processing demands, challenging scalability.

Bridging the gap between experimental success and farm-scale adoption requires multi-season, multi-location trials to assess robustness under diverse agro-ecological conditions, participatory research to tailor deployment protocols, and modular, ruggedized LiDAR systems adapted to specific crop types and budgets. Edge computing and cloud-based dashboards can alleviate computational bottlenecks, while open-access, labeled agricultural LiDAR datasets will enable the development and benchmarking of machine learning models. Finally, user-friendly interfaces and localized training programs are critical to overcoming the skill gap among farmers and technicians.

7 Discussion and Future Outlook

3D LiDAR technology has demonstrated transformative potential in enhancing precision agriculture through accurate, real-time, and non-invasive monitoring of crops and soil. Its integration with machine learning and robotics is driving automation and decision support across the crop lifecycle. However, several limitations—such as high cost, data processing complexity, and limited penetration in smallholder systems—persist.

7.1 Summary of Progress and Key Innovations

Recent advancements in LiDAR technology are significantly enhancing its usability in precision agriculture, particularly through miniaturization and cost reduction. Compact, low-cost LiDAR sensors—such as the Velodyne Puck Lite and Livox Mid series—are being increasingly integrated into UAVs and handheld systems, enabling scalable deployment even in resource-constrained environments. These lightweight sensors maintain sufficient spatial resolution for agricultural applications while reducing payload constraints and power consumption, making them ideal for high-frequency monitoring across diverse terrains.

In parallel, the fusion of LiDAR data with complementary spectral sources—such as multispectral, hyperspectral, and RGB imagery—is improving the reliability and richness of environmental interpretation. While LiDAR provides precise 3D structural data (e.g., plant height, canopy volume), spectral data contributes critical biochemical and physiological indicators (e.g., chlorophyll content, water stress). The integration of these modalities enhances the accuracy of classification tasks, such as crop type differentiation, disease detection, and yield forecasting. Data fusion frameworks, including both early fusion (raw data-level) and late fusion (decision-level), have been applied to maximize the synergistic strengths of these sensors.

Moreover, AI-driven analytics on 3D point cloud data are enabling a new era of automation in agricultural monitoring. Deep learning models—such as PointNet, PointCNN, and more recently, transformer-based architectures—can directly process raw point cloud data to perform object detection, semantic segmentation, and phenotypic trait estimation. These models reduce the reliance on manual feature engineering and improve scalability across different crops and field conditions. A growing number of studies now implement semi-supervised and transfer learning techniques to reduce the need for large annotated datasets. Semi-supervised models leverage both labeled and unlabeled LiDAR data to enhance generalization, while transfer learning reuses pre-trained weights from domains such as forestry or urban scenes to accelerate convergence in crop-specific tasks. The review distinguishes between these learning strategies and fully supervised pipelines, highlighting their advantages in data-scarce agricultural scenarios.

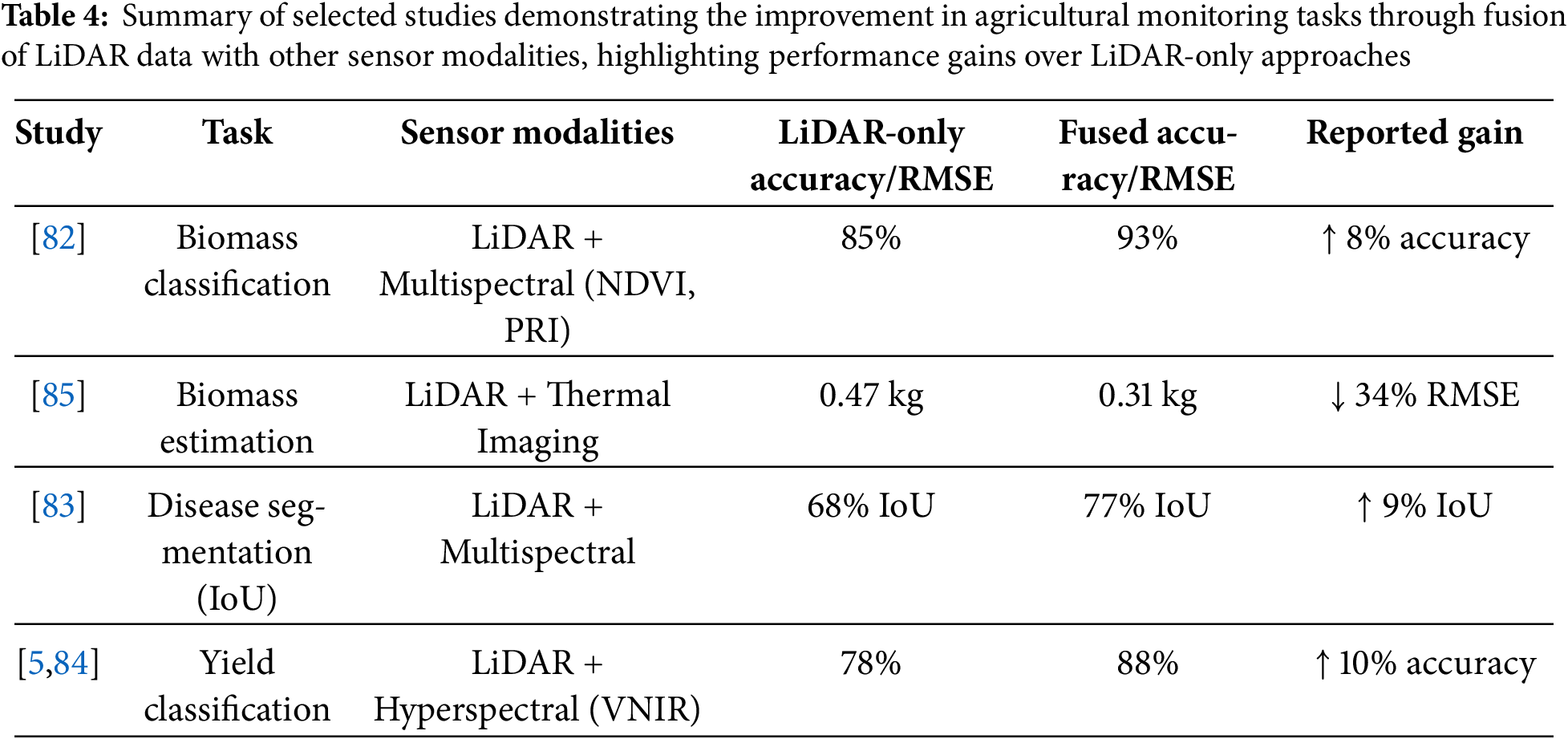

Integrating LiDAR-derived structural information with complementary spectral indices or thermal measurements has consistently improved performance across diverse agricultural tasks. For instance, Ref. [82] demonstrated that combining vegetation indices—specifically the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Photochemical Reflectance Index (PRI)—from multispectral imagery with LiDAR point clouds increased biomass classification accuracy from 85% (LiDAR-only) to 93%. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022) reported a reduction in root mean square error (RMSE) from 0.47 to 0.31 kg when LiDAR data were fused with canopy temperature measurements derived from thermal imagery [83]. In plant disease diagnostics, Ref. [83] showed that mid-level fusion of LiDAR geometry and multispectral reflectance achieved a 9% gain in Intersection over Union (IoU) for segmentation compared to LiDAR-only models. Likewise, Ref. [84] observed a 10% increase in yield classification accuracy when integrating LiDAR with visible–near-infrared (VNIR) hyperspectral data using hybrid deep learning frameworks. As shown in Table 4, the integration of LiDAR data with complementary sensing modalities such as multispectral, thermal, and hyperspectral imagery has consistently improved performance across biomass classification, biomass estimation, disease segmentation, and yield classification tasks.

These results highlight the complementarity of LiDAR’s high spatial fidelity and optical sensors’ spectral richness. However, differences in spatial resolution, spectral domains, acquisition frequency, and geometric alignment necessitate advanced co-registration methods such as GNSS/IMU-based synchronization, ground control point (GCP) rectification, and intrinsic–extrinsic calibration. Particularly for UAV-based deployments, precise temporal alignment is critical to mitigate spatial drift and geometric mismatches. Fusion approaches generally fall into three categories: early fusion, where raw features (e.g., XYZ coordinates, intensity, NDVI) are concatenated; mid-level fusion, where modality-specific features (e.g., CNN-extracted image descriptors and PointNet-extracted point cloud features) are merged; and late fusion, where decision-level outputs are combined.

7.2 Remaining Challenges and Research Gaps

Despite the promising capabilities of LiDAR technology in precision agriculture, several challenges continue to limit its widespread adoption and effectiveness. One significant barrier is the scarcity of publicly available, labeled datasets tailored for agricultural LiDAR applications. Most existing datasets are either proprietary or limited to forestry or urban mapping, leaving a gap in annotated point cloud data for diverse crop types, growth stages, and environmental conditions. This scarcity hampers the training and benchmarking of machine learning models for tasks such as plant segmentation, biomass estimation, and phenotyping.

While the limited availability of open-access agricultural LiDAR datasets remains a barrier to innovation, equally important are the issues related to data quality and annotation accuracy. Many existing datasets exhibit heterogeneous point densities, variable scanning angles, and occlusion effects due to dense vegetation, leading to inconsistent and unreliable ground-truth labels. Manual annotation remains the dominant method for labeling such datasets; however, it is labor-intensive and susceptible to subjective bias—particularly when distinguishing overlapping plant organs such as leaves, stalks, and stems. Widely used labeling tools like CloudCompare and LabelCloud do not include domain-specific modules for plant morphology, further reducing annotation efficiency and reproducibility.

To address these challenges, several methodological enhancements have been proposed. Data augmentation techniques—such as random rotation, jittering, scaling, and Gaussian noise injection—can increase the variability of training samples and improve model generalization. Additionally, synthetic point cloud generation using tools like Blender or recent techniques such as Gaussian Splatting has been used to simulate complex canopy structures and environmental variability. Voxel-based up-sampling and point interpolation algorithms also offer effective strategies to enhance low-density LiDAR scans.

Collaborative and semi-supervised annotation frameworks are gaining traction as alternatives to purely manual labeling. Platforms like LabelMe3D or crowd-sourced labeling tools enable large-scale dataset creation with community support. Simultaneously, semi-supervised learning techniques—including pseudo-labeling and consistency regularization—reduce the dependence on fully labeled data by leveraging unlabeled samples in training workflows.

To further improve model performance under limited data conditions, domain adaptation and transfer learning approaches are increasingly adopted. Pre-trained models—especially those developed for forestry or autonomous driving datasets—are fine-tuned on smaller agricultural datasets to bridge the domain gap. For instance, PointNet models originally trained on the KITTI dataset have been successfully adapted to tasks such as canopy segmentation and plant structure classification in agricultural settings, yielding competitive accuracy with minimal training data.

In addition to dataset scarcity, the quality of available agricultural LiDAR datasets often suffers from inconsistencies in point density, variable scan angles, and occlusion due to dense vegetation, making reliable annotation difficult. Most existing labeling approaches rely on manual annotation, which is not only time-consuming but also prone to ambiguity in differentiating plant organs such as leaves, stems, or overlapping canopies. To overcome this, collaborative labeling platforms and semi-supervised methods can be adopted to accelerate and standardize ground truth generation. Furthermore, data augmentation techniques—such as random rotation, jittering, scaling, and synthetic point cloud generation—can expand training diversity and improve generalization. Domain adaptation strategies (e.g., transfer learning from forestry or indoor datasets) also offer potential for improving model performance in underrepresented crop types or geographic regions where labeled agricultural data is unavailable.

The lack of open-access, labeled LiDAR datasets in agriculture not only constrains model development but also hinders reproducibility and benchmarking across studies. To address this, collaborative labeling platforms and community-driven data repositories should be encouraged, allowing researchers to share annotated point clouds under standardized formats. Additionally, synthetic point cloud generation using simulation tools or generative models (e.g., GANs, NeRFs) can help supplement training data for underrepresented crops and field conditions. Establishing benchmarking protocols with shared evaluation metrics (e.g., RMSE, IoU, R2) would further standardize performance reporting and enhance cross-study comparability. Cloud-based platforms such as PDAL and Google Earth Engine also play a pivotal role by providing low-cost, scalable solutions for storing, processing, and visualizing LiDAR data, thereby lowering the technical barriers to entry for users in resource-constrained settings.

Another persistent technical challenge is the issue of occlusion, particularly in dense or overlapping canopies, where parts of the plant are obscured from the sensor’s line of sight. This results in incomplete point cloud data, affecting the accuracy of derived morphological parameters such as canopy volume, LAI, and plant architecture. While techniques like multi-angle scanning, voxelization, and model-based reconstruction have been proposed to mitigate occlusion, these methods often increase processing complexity and computational load, posing scalability issues in field-scale deployments.

Several challenges limit the effectiveness of LiDAR-based analytics in agricultural applications, particularly when operating under real-world field conditions. Common dataset-related issues include sparse and noisy point clouds, which reduce segmentation accuracy and can be mitigated through denoising filters or voxel up-sampling. Manual labeling remains a labor-intensive process prone to annotation inconsistencies, prompting the adoption of semi-supervised learning approaches and collaborative labeling platforms. Dense canopy occlusion often results in incomplete structural data, which can be addressed using multi-view scanning and point cloud fusion techniques. Small dataset sizes lead to poor generalization of deep learning models; strategies such as data augmentation and synthetic point cloud generation can help alleviate this limitation. Furthermore, a domain gap from other fields—where pre-trained models from unrelated datasets exhibit low transferability—necessitates the use of transfer learning and domain adaptation frameworks.

Beyond dataset challenges, the environmental vulnerability of LiDAR sensors remains a significant bottleneck for operational deployment. Many low-cost units are prone to inaccuracies caused by mechanical vibrations, sensor drift, dust accumulation, and abrupt temperature fluctuations, particularly in agricultural environments. These issues are exacerbated in smallholder farming systems, where access to maintenance services and environmental shielding is often limited. While strategies such as SLAM-based sensor fusion and multi-angle scanning can reduce occlusion and enhance structural completeness, they typically require additional computational resources and careful calibration. Therefore, the development of lightweight, robust LiDAR systems coupled with integrated error-compensation pipelines is essential to ensure consistent performance in operational agricultural contexts [58].

Furthermore, the high cost of LiDAR systems—especially high-resolution TLS and advanced MLS platforms—combined with the need for technical expertise in data acquisition and processing, creates barriers for adoption in low-income or smallholder farming regions. Farmers in such regions may lack access to trained personnel or infrastructure needed to integrate LiDAR into their existing agricultural practices. Addressing these socio-technical challenges through open data initiatives, user-friendly platforms, and cost-sharing models will be critical to democratizing the benefits of LiDAR for sustainable agriculture globally.

7.3 Future Directions and Opportunities

Future research in precision agriculture is expected to be driven by innovations in LiDAR data acquisition, fusion techniques, and edge-based analytics for real-time decision-making. Multi-angle LiDAR fusion, as demonstrated by [86], can substantially enhance canopy segmentation accuracy by increasing the visibility of inner foliage, improving canopy completeness by 30%–40% and reducing biomass estimation errors due to occlusion by approximately 20%–35%. Achieving such improvements requires robust point cloud registration approaches, including Iterative Closest Point (ICP) for rigid alignment, SLAM-based methods for mobile scanning environments, and GNSS–IMU-based global alignment for UAV and mobile LiDAR platforms. Following alignment, voxel grid fusion or octree-based merging can be employed to generate denser and more structurally complete 3D canopy reconstructions, thereby reducing occlusion-related uncertainties in structural and biomass modeling.

Parallel advancements in lightweight deep learning architectures have opened opportunities for deploying LiDAR analytics on resource-constrained edge computing platforms such as the NVIDIA Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi 4, and Google Coral Edge TPU, enabling in-field data processing without reliance on high-bandwidth communication. Achieving this requires balancing computational efficiency with predictive accuracy, a challenge addressed through techniques such as model pruning to remove redundant weights [87], quantization to reduce parameter precision for faster inference [88], knowledge distillation to transfer performance from complex “teacher” models to compact “student” models [89], and the adoption of low-parameter architectures like MobileNetV2, PointNetLite, and Tiny-ConvNet. Additional optimizations, such as operator fusion to merge computational steps and minimize latency, can further improve edge deployment.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Farmer Mr. Fool Chandra, who generously provided his land for maize cultivation, which made this work possible. The authors also acknowledge the use of Quillbot for grammar checking and correction of typographical errors in the manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Mukesh Kumar Verma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. Manohar Yadav: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Galanakis CM. The future of food. Foods. 2024;13(4):506. doi:10.3390/foods13040506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kutyrev AI, Kiktev NA, Smirnov IG. Laser rangefinder methods: autonomous-vehicle trajectory control in horticultural plantings. Sensors. 2024;24(3):982. doi:10.3390/s24030982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Verma MK, Yadav M. Estimation of plant’s morphological parameters using terrestrial laser scanning-based three-dimensional point cloud data. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ. 2024;33:101137. doi:10.1016/j.rsase.2024.101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dhillon R, Moncur Q. Small-scale farming: a review of challenges and potential opportunities offered by technological advancements. Sustainability. 2023;15(21):15478. doi:10.3390/su152115478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yadav M, Lohani B. Identification of trees and their trunks from mobile laser scanning data of roadway scenes. Int J Remote Sens. 2020;41(4):1233–58. doi:10.1080/01431161.2019.1662966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang X, Zeng H, Yang X, Shu J, Wu Q, Que Y, et al. Remote sensing revolutionizing agriculture: toward a new frontier. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2025;166:107691. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.107691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Adhikari S, Ma Q, Poudel K, Renninger HJ. Aboveground woody biomass estimation of young bioenergy plantations of Populus and its hybrids using mobile (backpack) LiDAR remote sensing. Trees For People. 2024;18:100665. doi:10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Liu S, Baret F, Abichou M, Boudon F, Thomas S, Zhao K, et al. Estimating wheat green area index from ground-based LiDAR measurement using a 3D canopy structure model. Agric For Meteor. 2017;247:12–20. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Obaid S, Mohammed G, Nagaraju KC. Application of LiDAR and SLAM technologies in autonomous systems for precision grapevine pruning and harvesting. SHS Web Conf. 2025;216:01064. doi:10.1051/shsconf/202521601064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Barriguinha A, de Castro Neto M, Gil A. Vineyard yield estimation, prediction, and forecasting: a systematic literature review. Agronomy. 2021;11(9):1789. doi:10.3390/agronomy11091789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abeyrathna RMRD, Nakaguchi VM, Minn A, Ahamed T. Recognition and counting of apples in a dynamic state using a 3D camera and deep learning algorithms for robotic harvesting systems. Sensors. 2023;23(8):3810. doi:10.3390/s23083810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Shi J, Bai Y, Diao Z, Zhou J, Yao X, Zhang B. Row detection BASED navigation and guidance for agricultural robots and autonomous vehicles in row-crop fields: methods and applications. Agronomy. 2023;13(7):1780. doi:10.3390/agronomy13071780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Di Stefano F, Chiappini S, Gorreja A, Balestra M, Pierdicca R. Mobile 3D scan LiDAR: a literature review. Geomat Nat Hazards Risk. 2021;12(1):2387–429. doi:10.1080/19475705.2021.1964617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Menéndez-Miguélez M, Madrigal G, Sixto H, Oliveira N, Calama R. Terrestrial laser scanning for non-destructive estimation of aboveground biomass in short-rotation poplar coppices. Remote Sens. 2023;15(7):1942. doi:10.3390/rs15071942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Farhan SM, Yin J, Chen Z, Memon MS. A comprehensive review of LiDAR applications in crop management for precision agriculture. Sensors. 2024;24(16):5409. doi:10.3390/s24165409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Gong Y, Li X, Du H, Zhou G, Mao F, Zhou L, et al. Tree species classifications of urban forests using UAV-LiDAR intensity frequency data. Remote Sens. 2023;15(1):110. doi:10.3390/rs15010110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Moreno H, Valero C, Bengochea-Guevara JM, Ribeiro Á, Garrido-Izard M, Andújar D. On-ground vineyard reconstruction using a LiDAR-based automated system. Sensors. 2020;20(4):1102. doi:10.3390/s20041102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bohn Reckziegel R, Larysch E, Sheppard JP, Kahle HP, Morhart C. Modelling and comparing shading effects of 3D tree structures with virtual leaves. Remote Sens. 2021;13(3):532. doi:10.3390/rs13030532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Keightley KE, Bawden GW. 3D volumetric modeling of grapevine biomass using Tripod LiDAR. Comput Electron Agric. 2010;74(2):305–12. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2010.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Y, Fang H, Zhang Y, Li S, Pang Y, Ma T, et al. Retrieval and validation of vertical LAI profile derived from airborne and spaceborne LiDAR data at a deciduous needleleaf forest site. GISci Remote Sens. 2023;60:2214987. doi:10.1080/15481603.2023.2214987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Borrenpohl D, Karkee M. Automated pruning decisions in dormant sweet cherry canopies using instance segmentation. Comput Electron Agric. 2023;207:107716. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2023.107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Papadimitriou A, Kleitsiotis I, Kostavelis I, Mariolis I, Giakoumis D, Likothanassis S, et al. Loop closure detection and SLAM in vineyards with deep semantic cues. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2022 May 23–27; Philadelphia, PA, USA. doi:10.1109/ICRA46639.2022.9812419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chatziparaschis D, Teng H, Wang Y, Peiris P, Seudiero E, Karydis K. On-the-go tree detection and geometric traits estimation with ground mobile robots in fruit tree groves. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2024 May 13–17; Yokohama, Japan. doi:10.1109/ICRA57147.2024.10610355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chakraborty M, Khot LR, Sankaran S, Jacoby PW. Evaluation of mobile 3D light detection and ranging based canopy mapping system for tree fruit crops. Comput Electron Agric. 2019;158:284–93. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2019.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bajraktari A, Toylan H. Autonomous agricultural robot using YOLOv8 and ByteTrack for weed detection and destruction. Machines. 2025;13(3):219. doi:10.3390/machines13030219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Rivera G, Porras R, Florencia R, Sánchez-Solís JP. LiDAR applications in precision agriculture for cultivating crops: a review of recent advances. Comput Electron Agric. 2023;207:107737. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2023.107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lisiewicz M, Kamińska A, Stereńczak K. Recognition of specified errors of individual tree detection methods based on canopy height model. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ. 2022;25:100690. doi:10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ahmad U, Alvino A, Marino S. A review of crop water stress assessment using remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2021;13(20):4155. doi:10.3390/rs13204155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hosoi F, Omasa K. Estimation of vertical plant area density profiles in a rice canopy at different growth stages by high-resolution portable scanning lidar with a lightweight mirror. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2012;74:11–9. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2012.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Franz TE, Pokal S, Gibson JP, Zhou Y, Gholizadeh H, Tenorio FA, et al. The role of topography, soil, and remotely sensed vegetation condition towards predicting crop yield. Field Crops Res. 2020;252:107788. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2020.107788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu H, Zhong H, Lin W, Wu J. Tree species classification based on PointNet++ deep learning and true-colour point cloud. Int J Remote Sens. 2024;45(16):5577–604. doi:10.1080/01431161.2024.2377837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yao H, Qin R, Chen X. Unmanned aerial vehicle for remote sensing applications—a review. Remote Sens. 2019;11(12):1443. doi:10.3390/rs11121443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xie K, Zhu J, Ren H, Wang Y, Yang W, Chen G, et al. Delving into the potential of deep learning algorithms for point cloud segmentation at organ level in plant phenotyping. Remote Sens. 2024;16(17):3290. doi:10.3390/rs16173290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Charles RQ, Hao S, Mo K, Guibas LJ. PointNet: deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Qi CR, Yi L, Su H, Guibas LJ. PointNet++: deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

36. Maturana D, Scherer S. VoxNet: a 3D Convolutional Neural Network for real-time object recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2015 Sep 28–Oct 2; Hamburg, Germany. doi:10.1109/IROS.2015.7353481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang W, Qi J, Wan P, Wang H, Xie D, Wang X, et al. An easy-to-use airborne LiDAR data filtering method based on cloth simulation. Remote Sens. 2016;8(6):501. doi:10.3390/rs8060501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Pineau J, Vincent-Lamarre P, Sinha K, Lariviere V, Beygelzimer A, d’Alche-Buc F, et al. Improving reproducibility in machine learning research (a report from the NeurIPS 2019 reproducibility program). J Mach Learn Res. 2020;22:164:1–20. [Google Scholar]

39. Qian G, Li Y, Peng H, Mai J, Hammoud H, Elhoseiny M, et al. PointNeXt: revisiting PointNet++ with improved training and scaling strategies. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:23192–204. [Google Scholar]

40. Meng HY, Gao L, Lai YK, Manocha D. VV-net: voxel VAE net with group convolutions for point cloud segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yu X, Tang L, Rao Y, Huang T, Zhou J, Lu J. Point-BERT: pre-training 3D point cloud transformers with masked point modeling. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Omasa K, Hosoi F, Konishi A. 3D lidar imaging for detecting and understanding plant responses and canopy structure. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(4):881–98. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Islam N, Rashid MM, Wibowo S, Xu CY, Morshed A, Wasimi SA, et al. Early weed detection using image processing and machine learning techniques in an Australian chilli farm. Agriculture. 2021;11(5):387. doi:10.3390/agriculture11050387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Pramod Pawase P, Madhukar Nalawade S, Ashok Walunj A, Balasaheb Bhanage G, Bhaskar Kadam P, Durgude AG, et al. Comprehensive study of on-the-go sensing and variable rate application of liquid nitrogenous fertilizer. Comput Electron Agric. 2024;216:108482. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2023.108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yu Z, Qi J, Zhao X, Huang H. Evaluating the reliability of bi-temporal canopy height model generated from airborne laser scanning for monitoring forest growth in boreal forest region. Int J Digit Earth. 2024;17:2345725. doi:10.1080/17538947.2024.2345725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wang Y, Fang H. Estimation of LAI with the LiDAR technology: a review. Remote Sens. 2020;12(20):3457. doi:10.3390/rs12203457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Madec S, Baret F, de Solan B, Thomas S, Dutartre D, Jezequel S, et al. High-throughput phenotyping of plant height: comparing unmanned aerial vehicles and ground LiDAR estimates. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:2002. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.02002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Sun S, Li C, Paterson AH, Jiang Y, Xu R, Robertson JS, et al. In-field high throughput phenotyping and cotton plant growth analysis using LiDAR. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:16. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Chawade A, van Ham J, Blomquist H, Bagge O, Alexandersson E, Ortiz R. High-throughput field-phenotyping tools for plant breeding and precision agriculture. Agronomy. 2019;9(5):258. doi:10.3390/agronomy9050258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Johnsen K, Li C. A ground mobile robot for autonomous terrestrial laser scanning-based field phenotyping. arXiv:2404.04404. 2024. [Google Scholar]

51. Chedid E, Avia K, Dumas V, Ley L, Reibel N, Butterlin G, et al. LiDAR is effective in characterizing vine growth and detecting associated genetic loci. Plant Phenomics. 2023;5:0116. doi:10.34133/plantphenomics.0116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hao Y, Zhen Z, Li F, Zhao Y. A graph-based progressive morphological filtering (GPMF) method for generating canopy height models using ALS data. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2019;79:84–96. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2019.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Siebers MH, Fu P, Blakely BJ, Long SP, Bernacchi CJ, McGrath JM. Fast, nondestructive and precise biomass measurements are possible using lidar-based convex hull and voxelization algorithms. Remote Sens. 2024;16(12):2191. doi:10.3390/rs16122191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Li W, Guo Q, Jakubowski MK, Kelly M. A new method for segmenting individual trees from the lidar point cloud. Photogramm Eng Remote Sensing. 2012;78(1):75–84. doi:10.14358/pers.78.1.75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Ma Y, Zhang Z, Kang Y, Özdoğan M. Corn yield prediction and uncertainty analysis based on remotely sensed variables using a Bayesian neural network approach. Remote Sens Environ. 2021;259:112408. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2021.112408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kang Y, Kim M, Kang E, Cho D, Im J. Improved retrievals of aerosol optical depth and fine mode fraction from GOCI geostationary satellite data using machine learning over East Asia. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2022;183:253–68. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.11.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Parizzi A, Rodriguez Gonzalez F, Brcic R. A covariance-based approach to merging InSAR and GNSS displacement rate measurements. Remote Sens. 2020;12(2):300. doi:10.3390/rs12020300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]