Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VCA Augments Doxorubicin Efficacy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Evidence for Multi-Pathway Synergism

1 Department of Pharmacy, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

2 Smart Beautytech Research Institute, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

3 Research Institute of Life and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Su-Yun Lyu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural Product-Based Anticancer Drug Discovery)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2377-2397. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072360

Received 25 August 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Objective: Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) remains a major therapeutic challenge with limited treatment options and poor prognosis. This study aimed to investigate the synergistic anticancer effects of doxorubicin (DOX) combined with Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin (VCA) and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms in TNBC cells. Methods: This study evaluated the synergistic effects and mechanisms of doxorubicin (DOX) and Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin (VCA) combination in MDA-MB231 TNBC cells. Cell viability, oxidative stress markers, apoptosis-related proteins, cell migration, and proliferative recovery were assessed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and nitric oxide (NO) assays, Western blotting, wound healing assay, and Muse™ cell analyzer, respectively. Results: The DOX-VCA combination demonstrated strong synergistic cytotoxicity with Bliss Independence scores of +8.9% to +33.4% at therapeutic concentrations (0.01–50 ng/mL, p = 0.032) and remarkable dose reduction indices of >3000-fold for DOX and >16.7-fold for VCA. This synergistic effect was mediated through multiple mechanisms: enhanced oxidative stress modulation (48% increase in SOD-like activity, p = 0.0003, and 94% increase in NO production, p = 0.0002, at 50 ng/mL combination compared to control), augmented apoptotic responses (4.8-fold increase in cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio, p = 0.0001, and 91% reduction in procaspase-9 levels, p = 0.00008, at 48 h compared to control), significant inhibition of cell migration (85.8% remaining wound area at 48 h, p = 0.0004 vs.control), and severely impaired proliferative recovery (98.9% reduction in cell viability at 72 h post-treatment, p = 0.0001 vs. untreated control). Conclusion: The DOX-VCA combination demonstrates potent synergistic effects through multiple mechanisms, warranting further investigation as a potential dose-reducing strategy for TNBC treatment.Keywords

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly aggressive subtype of breast cancer characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression [1]. TNBC accounts for 12%–20% of all breast cancers and is associated with poor prognosis compared to other breast cancer subtypes [1,2]. This subtype is more prevalent in younger women, particularly those of African American descent, and is characterized by aggressive clinical behavior with higher risks of early recurrence and metastasis [3]. Furthermore, TNBC preferentially metastasizes to visceral organs, including the lungs, liver, and brain, contributing to its poor prognosis [4]. The median overall survival for patients with metastatic TNBC is approximately 13 months, highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies [5]. Previous studies have explored various combination therapies to enhance doxorubicin (DOX) efficacy while reducing its toxicity. Plant-derived compounds have shown particular promise, with studies demonstrating synergistic effects when combined with conventional chemotherapeutics [6]. Mistletoe extracts, specifically, have been investigated for their anticancer properties through multiple mechanisms, including immunomodulation, apoptosis induction, and anti-angiogenic effects [7,8]. Several clinical studies have reported improved quality of life and reduced chemotherapy-related adverse effects when mistletoe preparations were used as adjuvant therapy [9]. However, the specific interaction between mistletoe lectin and DOX in TNBC cells, particularly regarding their synergistic mechanisms and dose-reduction potential, has not been systematically investigated. Current standard treatment for TNBC relies primarily on cytotoxic chemotherapy, including anthracyclines, taxanes, and platinum agents [5,10]. Among these, DOX, an anthracycline antibiotic, remains a cornerstone in TNBC treatment due to its potent cytotoxic effects [11]. DOX exerts its antitumor activity through multiple mechanisms, including DNA intercalation, topoisomerase II inhibition, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [12]. However, the clinical utility of DOX is limited by dose-dependent cardiotoxicity, which can lead to irreversible cardiomyopathy and heart failure [13].

Due to the limitations of current therapies and the aggressive nature of TNBC, there is growing interest in identifying combination therapies that may improve therapeutic outcomes. One promising strategy is the co-administration of standard chemotherapeutic drugs with bioactive compounds from natural sources that possess anticancer properties [14]. Viscum album L. (European mistletoe) is a semi-parasitic plant that grows on various host trees and has been used in traditional medicine for centuries, particularly in cancer treatment in Europe [12]. The anticancer activities of V. album are primarily attributed to mistletoe lectins, which are ribosome-inactivating proteins with direct cytotoxic and immunomodulatory effects [15]. Mistletoe lectins exert multiple mechanisms of action, including direct cytotoxic effects on cancer cells and modulation of the immune system, potentially enhancing the body’s ability to fight cancer [16,17]. V. album L. var. coloratum, a subspecies indigenous to Korea, Japan, and China, has received less attention than the European species [18]. Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that it possesses comparable anticancer properties. We previously reported that lectin isolated from V. album L. var. coloratum agglutinin (VCA) exhibits anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties in several cancer cell lines, including breast cancer [19,20]. We demonstrated that VCA induces apoptosis through downregulation of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), inhibition of telomerase activity, and activation of caspase-3 [21]. Additionally, VCA modulates the protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in cell survival and proliferation and is frequently dysregulated in cancer [22]. These findings suggest that VCA may be valuable in combination therapy for aggressive cancers such as TNBC.

A combination of plant-derived compounds with conventional chemotherapy has shown potential to enhance anticancer efficacy while reducing toxicity [14]. This combination therapy approach can target multiple molecular pathways simultaneously, potentially preventing drug resistance and improving therapeutic outcomes [23]. This strategy is particularly relevant for TNBC, which has limited treatment options. Given that DOX is effective in TNBC treatment and VCA has demonstrated promising anticancer properties, investigating their combination represents a valuable research direction. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of VCA and DOX combination on MDA-MB231 TNBC cells, focusing on cell viability, apoptosis induction, oxidative stress markers, cell migration, and proliferative recovery. We hypothesized that the combination would show synergistic effects through simultaneous targeting of multiple pathways. Through comprehensive evaluation of these parameters, we sought to identify potential therapeutic targets for improved TNBC treatment strategies.

While our previous work explored the combination of doxorubicin and Korean mistletoe lectin in breast cancer more broadly [19], the specific synergistic mechanisms and therapeutic potential of this combination in TNBC remain unexplored. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the synergistic anticancer effects of DOX combined with VCA and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms in TNBC cells. Specifically, we evaluated: (1) synergistic cytotoxicity in a TNBC cell line (MDA-MB-231), (2) oxidative stress modulation through superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity and nitric oxide (NO) production, (3) apoptotic pathway activation, (4) anti-migratory effects, and (5) long-term proliferative recovery. We hypothesized that the DOX-VCA combination would demonstrate synergistic cytotoxicity through coordinated modulation of multiple cellular pathways, potentially offering a dose-reduction strategy for TNBC treatment.

The human TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 was obtained from the Korea Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (11875-093) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (16000044), 1% (v/v) non-essential amino acids (11140-050), 1% (v/v) L-glutamine (25030-081), and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (15140-122) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. DOX was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (D1515, St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to prepare a 10 mm stock solution, which was stored at −20°C. Mycoplasma contamination testing was routinely conducted using the MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07-318, Basel, Switzerland), confirming the absence of contamination throughout all experimental procedures.

2.2 Isolation and Purification of VCA

Viscum album L. var. coloratum was collected from oak trees (Quercus sp.) in Kangwon Province, South Korea, in December. The botanical identity was confirmed by Prof. Jon-Suk Lee (College of Natural Sciences, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea). VCA was isolated and purified as previously described [24]. Briefly, the mistletoe extract was applied to SP Sephadex C-50 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and eluted with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). The lectin-containing fractions were further purified using asialofetuin-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography and concentrated by ultrafiltration (10 kDa molecular weight cut-off; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The purity of VCA was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (23227, Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23227, Waltham, MA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. The purified VCA was divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C. All experiments were performed using aliquots from the same purified batch to ensure consistency. The purity and biological activity of VCA used in this study were confirmed to be consistent with our previous reports [24–27].

2.3 Cell Viability and Bliss Independence Analysis

Cell viability was assessed using the (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then treated with various concentrations of DOX (0.001–10,000 ng/mL), VCA (0.001–10,000 ng/mL), or their combinations at a 1:1 ratio for 48 h. After treatment, 20 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/mL; M5655 Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; D2650, Sigma-Aldrich), and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise; Tecan). Drug interaction was evaluated using the Bliss Independence model [28]. The Bliss score was calculated as: effect_DOX = 1 − (viability_DOX/100), effect_VCA = 1 − (viability_VCA/100), expected = effect_DOX + effect_VCA − (effect_DOX × effect_VCA), observed = 1 − (viability_combination/100), and Bliss Score (%) = (observed − expected) × 100. Bliss scores were interpreted as strong synergy (>10%), synergy (5%–10%), additive effects (−5% to +5%), and antagonism (<−5%), based on established criteria [29]. The dose reduction index (DRI) was calculated as IC50 (single agent)/IC50 (in combination) to quantify the fold-reduction in drug concentration achieved through combination therapy. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

SOD-like activity was measured using a SOD assay kit (19160, Sigma-Aldrich). MDA-MB-231 cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with DOX, VCA, or their combinations for 48 h. Then, cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (78444, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min at 4°C (VS-550, Vision Scientific Co., Daejeon, Republic of Korea), and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay (23227, Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). SOD-like activity was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions, based on the inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction by superoxide radicals generated by xanthine/xanthine oxidase. The absorbance was read at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), and SOD-like activity was expressed as the inhibition rate percent.

NO production was assessed using the Griess reagent method [30,31]. Cell culture supernatants were collected after treatment with DOX, VCA, or their combinations for 48 h. Equal volumes (50 μL) of supernatant and Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0.1% naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in distilled water) were mixed in a 96-well plate. After 10 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm with a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan). NO concentration was determined using a sodium nitrite standard curve. For normalization, cells from the same treatment groups were lysed in RIPA buffer (89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and total protein content was measured using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific). NO levels were expressed as μM per mg of total protein.

Western Blot Analysis Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (78444, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010, Immobilon-P, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies against caspase-3 (1:1000, 9662, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000, 9661, Cell Signaling Technology), procaspase-9 (1:1000, 9508, Cell Signaling Technology), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:1000, 5174, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000, 7074, Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate, 32106, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54f, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA).

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and grown to confluence. A scratch was made using a sterile 200 μL pipette tip. Cells were washed with PBS and treated with DOX, VCA, or their combinations in serum-free medium (RPMI 1640 without FBS, 11875-093, Life Technologies). Images were captured at 0, 24, and 48 h using a JuLI Smart Fluorescence Cell Imager (NanoEnTek Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) at 4× magnification. Wound closure was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54f, NIH) by measuring the wound area at each time point. The percentage of wound closure was calculated relative to the initial wound area.

2.8 Proliferative Recovery Assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated with DOX, VCA, or their combinations for 24 h. The treatment medium was then removed, cells were washed with PBS, and fresh growth medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 11875-093 and 16000044, Life Technologies) was added. Viable cell counts were obtained at 48 h post-treatment removal using a Muse™ Cell Analyzer (MCH100101, Millipore) with the Muse™ Count & Viability Kit (MCH100102, Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were trypsinized, resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, 11875-093 and 16000044, Life Technologies), and mixed with an equal volume of Muse™ Count & Viability Reagent (part number 4700-0490, supplied with MCH100102, Millipore). After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, samples were analyzed on the Muse™ Cell Analyzer (Millipore).

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates and treated with DOX, VCA, or their combinations for 48 h. For nuclear staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min at room temperature), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (10 min at room temperature), and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/mL; D9542, Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min in the dark. For live/dead cell staining, cells were incubated with calcein-AM (2 μm, C3100MP, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and ethidium homodimer-1 (4 μm, E1169, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (BX53, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined as follows: For single time point comparisons (MTT, SOD, NO assays, and fluorescence microscopy quantification), one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used. For experiments with multiple time points (Western blot, wound healing, and proliferative recovery assays), two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used. *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001). For the MTT assay, IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For drug interaction analysis, Bliss Independence scores and DRI were calculated as described in Section 2.3.

3.1 Synergistic Cytotoxicity of DOX and VCA on MDA-MB231 Cells

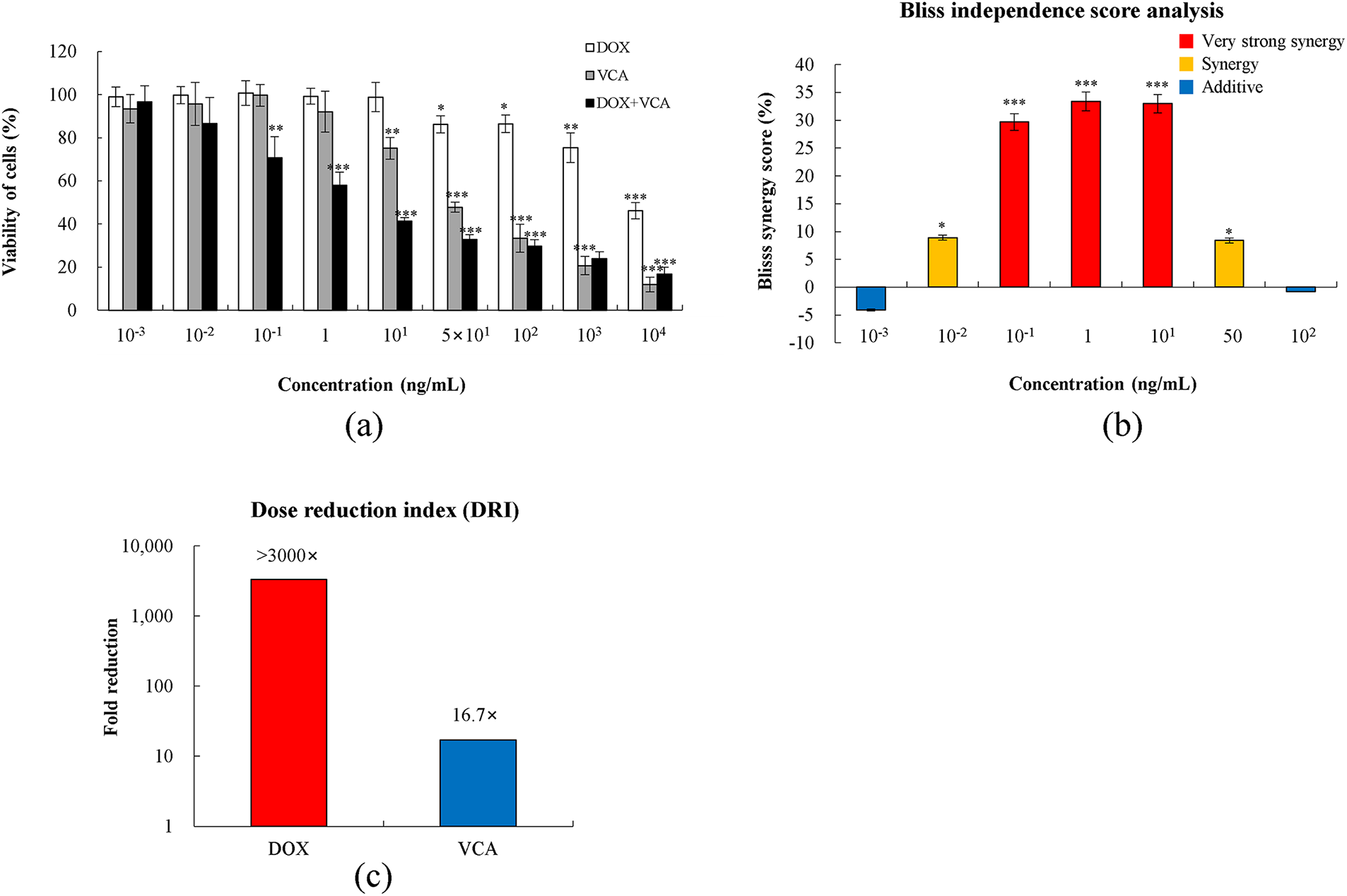

The cytotoxic effects of DOX, VCA, and their combination on MDA-MB231 triple-negative breast cancer cells were assessed by MTT assay at various concentrations of 0.001–10,000 ng/mL (Fig. 1a). VCA exhibited significant cytotoxicity at concentrations above 10 ng/mL, with the cell viability reducing to 75.11% ± 8.58% at 10 ng/mL (p = 0.0058), 47.80% ± 2.34% at 50 ng/mL (p = 0.00003), and further declining to 11.95% ± 3.42% at 10,000 ng/mL (p = 0.000004). The IC50 for VCA at 48 h was calculated to be approximately 50 ng/mL. DOX showed a relatively mild dose-response pattern, with significant cytotoxicity at concentrations above 50 ng/mL. The cell viability was reduced to 86.22% ± 4.01% at 50 ng/mL (p = 0.023), 86.48% ± 4.71% at 100 ng/mL (p = 0.027), and 46.16% ± 3.81% at 10,000 ng/mL (p = 0.00007). The DOX-VCA combination showed significantly higher cytotoxicity compared to either agent alone. Cell death was significant at concentrations as low as 0.1 ng/mL (70.77% ± 9.82% viability, p = 0.0067). At higher concentrations, the combination induced significant cytotoxicity, with the cell viability reducing to 29.78% ± 2.90% at 100 ng/mL and 16.77% ± 3.28% at 10,000 ng/mL (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.000001, respectively).

Figure 1: Synergistic cytotoxicity of doxorubicin (DOX) and Viscum album L. var. colroatum agglutinin (VCA) combination in MDA-MB231 cells. (a) Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay after 48 h treatment with DOX, VCA, or their 1:1 combination at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 100 ng/mL. (b) Bliss Independence Score analysis showing drug interaction effects. Positive values indicate synergy (red bars: >10%, strong synergy; orange bars: 5%–10%, synergy), while values near zero indicate additive effects (blue bars: −5% to +5%). (c) Dose reduction index (DRI) demonstrating fold-reduction in required drug concentration when used in combination compared to single agents (IC50 alone/IC50 in combination). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

To evaluate drug interaction, we analyzed the Bliss Independence scores (Fig. 1b). The combination demonstrated strong synergistic effects at therapeutic concentrations (0.1–10 ng/mL) with Bliss scores ranging from +29.7% to +33.4%, all showing statistical significance (p < 0.001). Moderate synergy was observed at 0.01 ng/mL (+8.9%, p = 0.032) and 50 ng/mL (+8.4%, p = 0.038), while additive effects were seen at extreme concentrations (0.001 and 100 ng/mL; −4.1% and −0.8%, respectively). The DRI analysis (Fig. 1c) revealed remarkable dose-sparing potential, with DOX doses reducible by >3000-fold and VCA by >15-fold when used in a 1:1 combination. Based on these results, we chose 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL of VCA and DOX for subsequent experiments. These concentrations were selected as they demonstrated strong to moderate synergistic effects (Bliss scores: +33.4%, +29.7%, and +8.4%, respectively) while ensuring sufficient cellular responses for comprehensive mechanistic studies. This range allowed us to investigate whether the synergistic mechanisms remain consistent across different levels of drug interaction.

3.2 Modulation of Oxidative Stress Markers by DOX and VCA

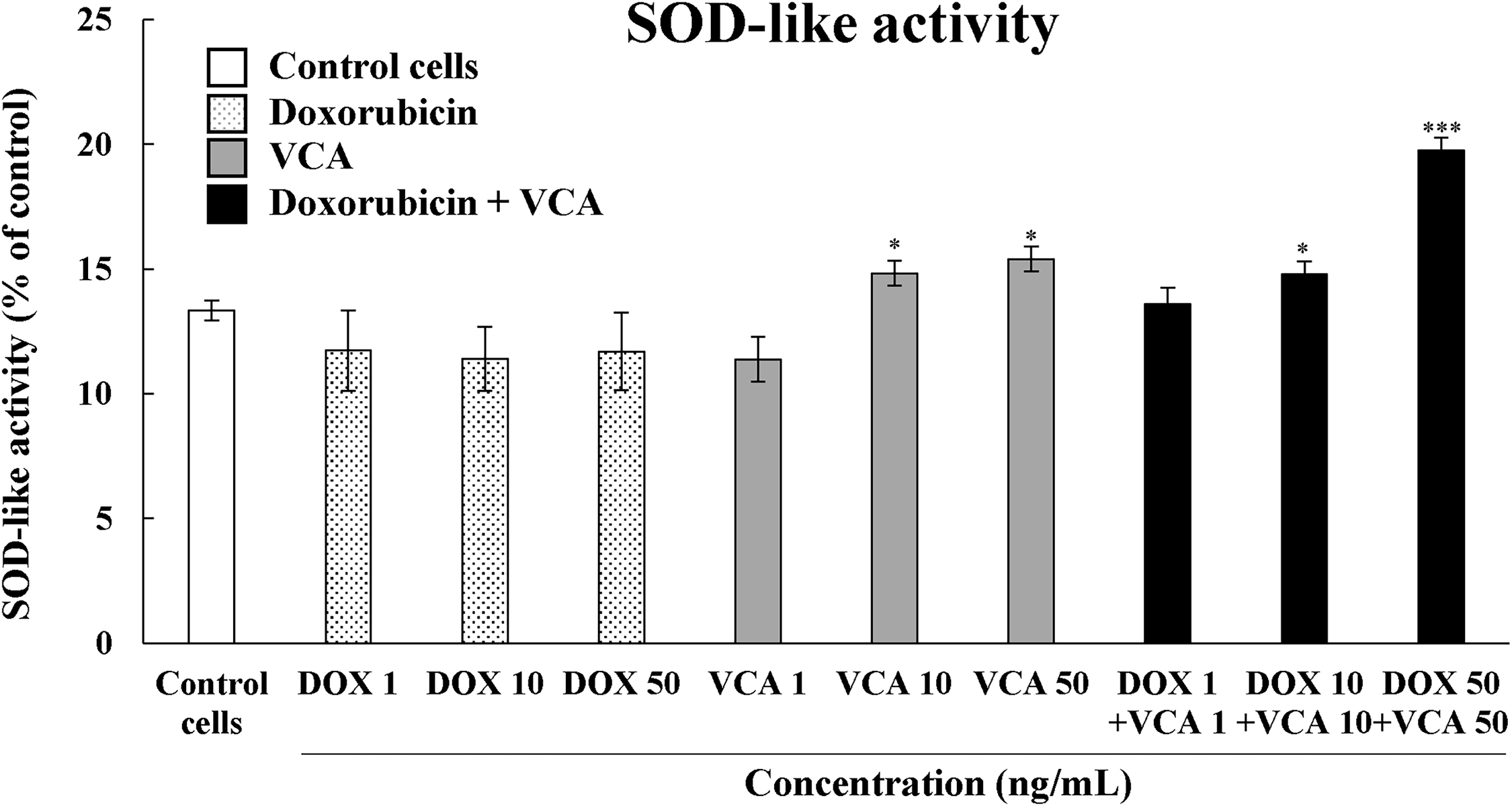

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the synergistic cytotoxicity, we first evaluated the effects of DOX, VCA, and their combination on the intracellular antioxidant potential by measuring SOD-like activity (Fig. 2). VCA alone significantly enhanced SOD-like activity in a dose-dependent manner, with activities of 14.84% ± 0.51% at 10 ng/mL and 15.39% ± 0.50% at 50 ng/mL (p = 0.0056 and p = 0.0038, respectively) compared to 13.35% ± 0.40% in control cells. On the other hand, DOX treatment did not significantly change the SOD-like activity at any of the tested concentrations, with values ranging from 11.37% ± 1.60% at 1 ng/mL to 11.69% ± 1.56% at 50 ng/mL (all p > 0.05 vs. control). The combination of DOX and VCA exhibited a synergistic increase in SOD-like activity. The highest activity was seen with 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA (19.76% ± 0.50%, p = 0.0003 vs. control and vs. either agent alone), which was a 48% increase over the control level. Interestingly, the lower combination dose of 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA also enhanced the SOD-like activity (14.79% ± 0.51%, p = 0.0072), which was higher than that of the individual drugs at these concentrations.

Figure 2: Superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity in MDA-MB231 cells when treated with DOX, VCA, or cotreatment of DOX and VCA. Cells were treated for 48 h, and the SOD-like activity was measured by the SOD assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: *(p < 0.05), *** (p < 0.001)

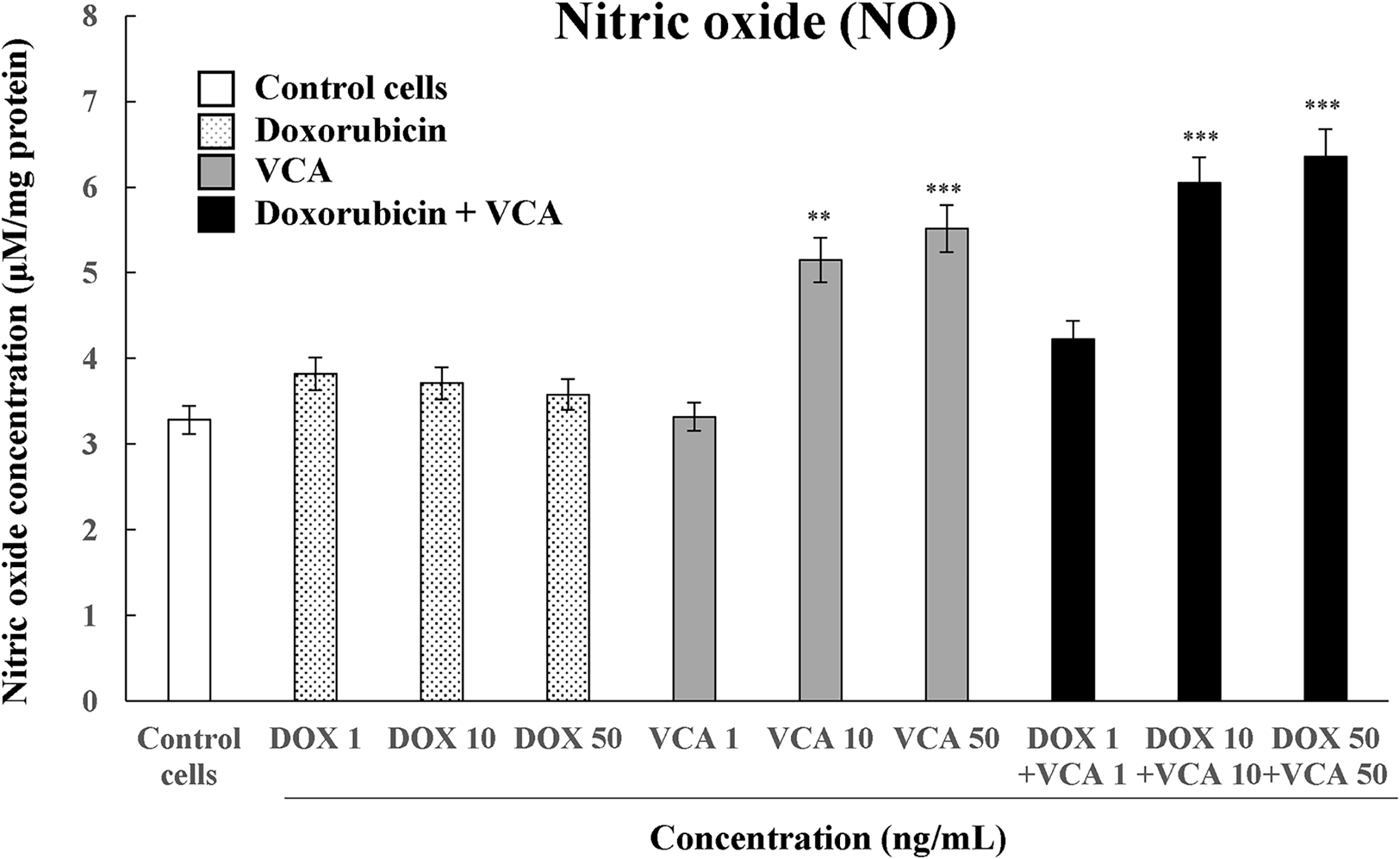

To assess the effect on cellular redox state, we also determined NO production using the Griess reagent assay (Fig. 3). VCA treatment alone also induced a dose-dependent increase in NO production, with the level being significantly increased at 10 ng/mL (5.15 ± 0.03 μm, p = 0.0046) and 50 ng/mL (5.51 ± 0.04 μm, p = 0.0031), compared to control levels (3.28 ± 0.02 μm). There was no significant change in NO levels in DOX-treated cells at any of the tested concentrations, which ranged from 3.58 ± 0.03 μm at 1 ng/mL to 3.82 ± 0.03 μm at 50 ng/mL (all p > 0.05 vs. control). The combination of DOX and VCA resulted in a synergistic effect in NO production. The highest NO concentrations were detected in the cells treated with 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA (6.05 ± 0.04 μm, p = 0.0006) and 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA (6.36 ± 0.04 μm, p = 0.0002). These combination treatments enhanced NO production by 84% and 94%, respectively, compared to control levels, and were more effective than the individual treatments.

Figure 3: Measurement of nitric oxide (NO) concentration in MDA-MB231 cells when treated with DOX, VCA, or the cotreatment of DOX and VCA. Cells were treated for 48 h, and the concentration of NO was measured. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

3.3 Induction of Apoptosis by DOX and VCA

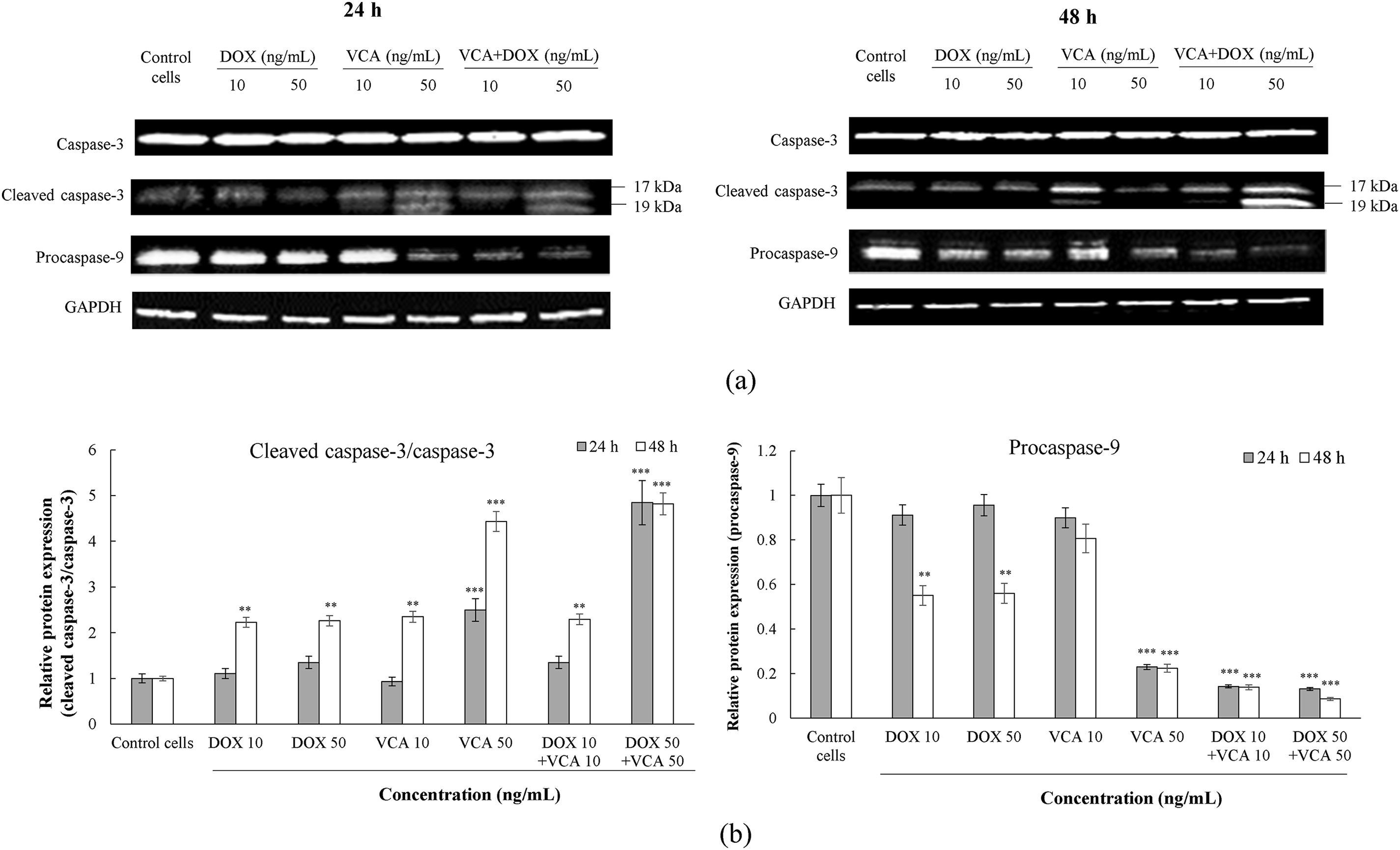

Given that oxidative stress is a well-established inducer of apoptosis, we investigated whether the enhanced oxidative modulation by the DOX-VCA combination corresponded with increased apoptotic responses. The expression of key proteins associated with apoptosis was determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4). We focused on the cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio as a marker of apoptosis execution and procaspase-9 levels as an indicator of intrinsic apoptosis pathway activation. The DOX-VCA combination induced a significantly greater increase in cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio compared to single-agent treatments, both at 24 and 48 h. At 24 h, the highest ratio was seen with 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA (4.85 ± 0.15 fold increase vs. control, p = 0.0001), compared to 1.35 ± 0.08 and 2.50 ± 0.11 fold increases for 50 ng/mL DOX and 50 ng/mL VCA alone, respectively. This effect was more significant at 48 h, where 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA induced a 4.82 ± 0.18 fold increase in the cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio (p = 0.0007), compared to the 2.26 ± 0.09 and 4.43 ± 0.16 fold increases observed for 50 ng/mL DOX and 50 ng/mL VCA alone, respectively. In addition, procaspase-9 levels were reduced with the combination treatment, particularly at 48 h. The most significant reduction was at 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA at 48 h, where procaspase-9 levels were reduced to 8.66% ± 0.52% of control levels (p = 0.00008), compared to 55.97% ± 2.80% and 22.43% ± 1.35% for 50 ng/mL DOX and 50 ng/mL VCA alone, respectively. Further analysis of our data revealed a potential relationship between the modulation of oxidative stress markers and apoptosis induction. The increase in SOD-like activity and NO production observed with the DOX-VCA combination corresponded with enhanced apoptotic responses, as evidenced by increased cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratios and decreased procaspase-9 levels. This suggests that the combination therapy may be activating multiple cell death pathways simultaneously, potentially explaining its synergistic effects.

Figure 4: Effects of DOX and VCA on apoptosis-related protein expression in MDA-MB231 cells. (a) Representative Western blot images showing expression of caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3 (17 and 19 kDa), procaspase-9 (47 kDa), and GAPDH loading control at 24 h (left) and 48 h (right) post-treatment. (b) Quantification of apoptotic markers. The left panel shows the cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio, and the right panel shows procaspase-9 levels relative to GAPDH at 24 h (grey bars) and 48 h (white bars). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

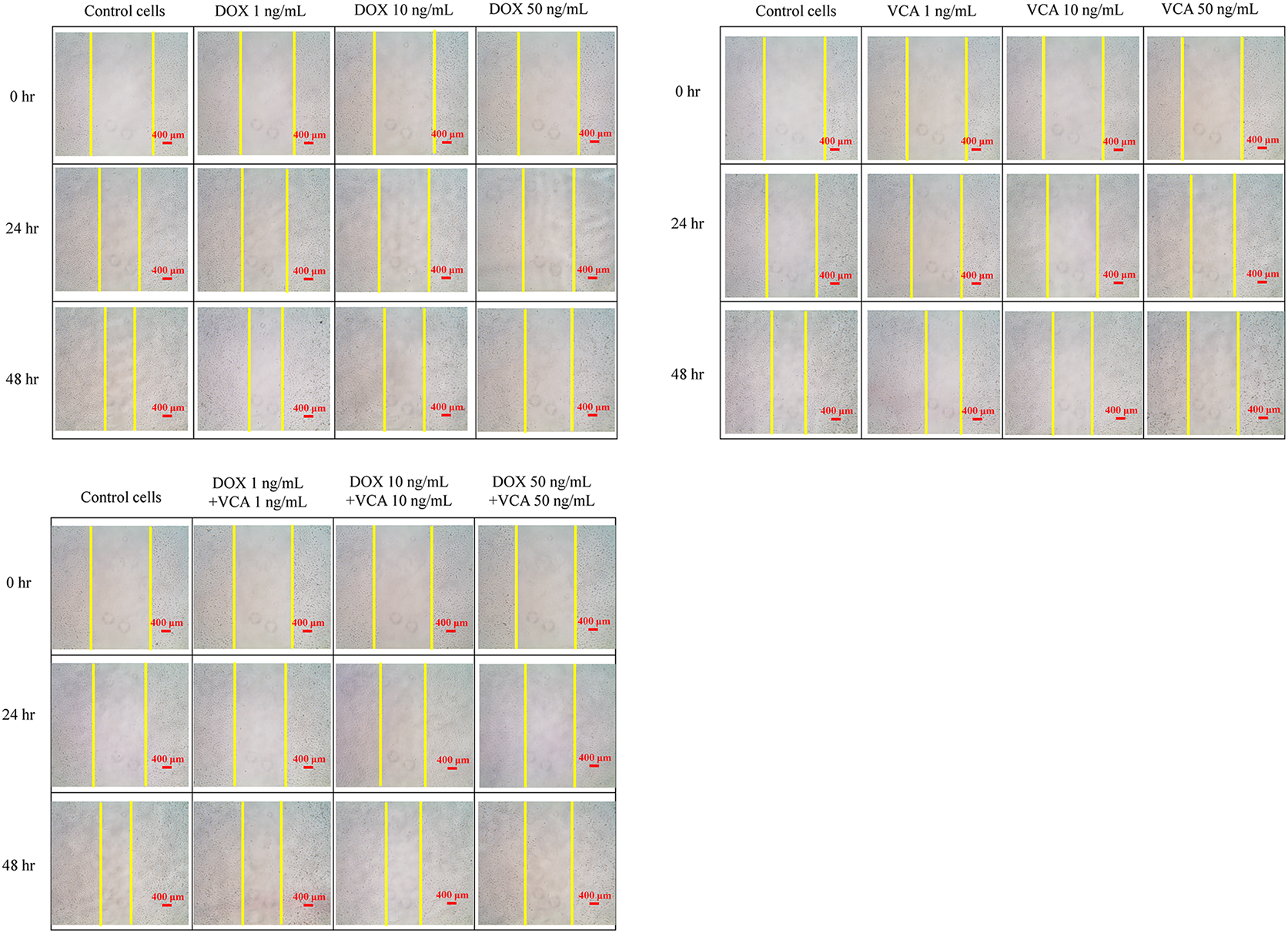

3.4 Effects of DOX and VCA on Cell Migration in Wound Healing Assay

Having established that the DOX-VCA combination induces significant apoptosis, we next assessed its effects on cell migration, a key process in cancer metastasis. A wound healing assay was used to assess the effects on cell migration (Fig. 5). The remaining wound area was measured at 0, 24, and 48 h post-treatment. DOX alone prevented wound healing in a dose-dependent manner. At 48 h, significant inhibition was observed with 10 ng/mL DOX (69.95 ± 3.50% remaining wound area, p = 0.0056) and 50 ng/mL DOX (76.39% ± 3.82% remaining wound area, p = 0.0008), compared to control (49.08% ± 2.45% remaining wound area). VCA also showed a dose-dependent inhibition of cell migration. At 48 h, significant effects were seen at 10 ng/mL VCA (64.71% ± 3.24% remaining wound area, p = 0.0041) and 50 ng/mL VCA (83.46% ± 4.17% remaining wound area, p = 0.0006). The combination of DOX and VCA was more effective in inhibiting cell migration. Interestingly, the treatment with both 1 ng/mL DOX and 1 ng/mL VCA inhibited the wound closure at 48 h (61.66% ± 3.08% remaining wound area, p = 0.023), while each drug alone had no such effect at this concentration. Higher combination doses showed a more significant inhibition of cell migration. At 48 h, 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA resulted in 67.77% ± 3.39% remaining wound area (p = 0.0033), while 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA led to 85.82% ± 4.29% remaining wound area (p = 0.0004).

Figure 5: Effects of DOX and VCA on MDA-MB-231 cell migration in a wound healing assay. Cells were treated with DOX, VCA, or their combinations for 48 h. Representative microscopic images show wound closure at 0, 24, and 48 h post-treatment. Quantitative analysis of the remaining wound area over time is presented in the graphs. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control at each time point was determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001). Magnification: 4×. Scale bars, 400 μm

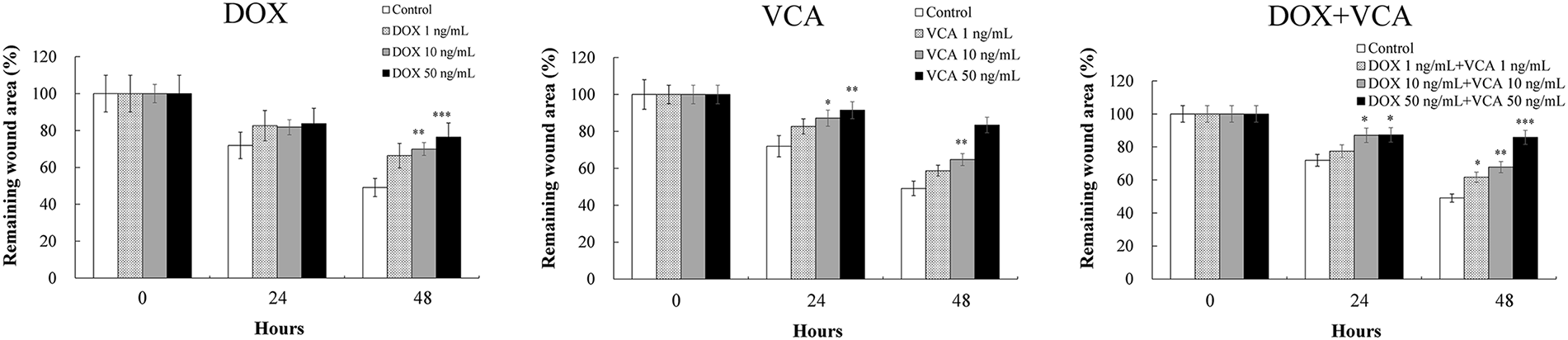

3.5 VCA Impairment of Proliferative Recovery by DOX and VCA

While immediate cytotoxic effects are important, the ability to prevent cancer cell recovery is crucial for long-term therapeutic success. Therefore, we evaluated the long-term effects of treatments on cell proliferation using a proliferative recovery assay. The long-term effects of treatments on cell proliferation were assessed using a proliferative recovery assay (Fig. 6). After 24 h of treatment and compound removal, cell proliferation was monitored for an additional 48 h. DOX alone caused a dose-dependent inhibition of proliferative recovery. At 48 h post-treatment removal, the differences were statistically significant with 10 ng/mL DOX (5.43 ± 0.27 × 104 cells, p = 0.0008) and 50 ng/mL DOX (5.01 ± 0.25 × 104 cells, p = 0.0006) vs. control (10.03 ± 0.50 × 104 cells). VCA demonstrated more potent inhibition of proliferative recovery. Significant effects were observed at all tested concentrations at 48 h post-treatment removal: 1 ng/mL VCA (2.01 ± 0.10 × 104 cells, p = 0.0004), 10 ng/mL VCA (0.55 ± 0.03 × 104 cells, p = 0.0002), and 50 ng/mL VCA (0.33 ± 0.02 × 104 cells, p = 0.0001). The combination of DOX and VCA led to a more significant inhibition of proliferative recovery. Even at the lowest combination dose (1 ng/mL DOX + 1 ng/mL VCA), there was still a significant inhibition (0.77 ± 0.04 × 104 cells, p = 0.0003). Higher combination doses almost completely abrogated proliferative recovery: 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA (0.55 ± 0.03 × 104 cells, p = 0.0002) and 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA (0.11 ± 0.01 × 104 cells, p = 0.0001).

Figure 6: Assessment of DNA damage and proliferative recovery in MDA-MB231 cells treated with DOX and VCA. (a) Proliferative recovery following DOX treatment alone at 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL. (b) Proliferative recovery following VCA treatment alone at 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL. (c) Proliferative recovery following DOX + VCA combination treatment at equivalent concentrations. Cells were treated for 24 h (red vertical line indicates treatment removal), followed by a 48 h recovery period. Relative viable cell counts were measured at 0 h (treatment initiation), 24 h (treatment removal), and 72 h (proliferative recovery). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control at each time point was determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test: *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

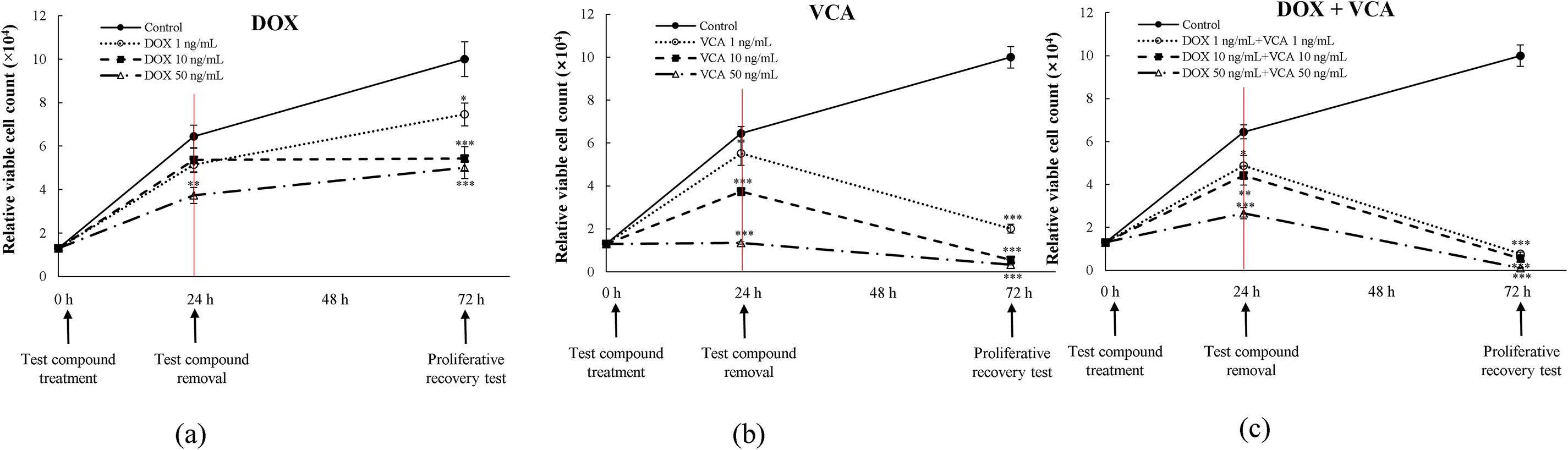

3.6 Quantification of Cell Viability and Death

3.6.1 DAPI Staining and Nuclei Quantification

To visually confirm and quantify the cytotoxic effects observed in our functional assays, we performed DAPI staining and nuclei quantification (Fig. 7). The total number of nuclei per field was counted after 48 h of treatment. DOX alone decreased the number of nuclei in a dose-dependent manner, with a statistically significant decrease at 10 ng/mL (167 nuclei per field, 69.87% of control, p = 0.024) and 50 ng/mL (61 nuclei per field, 25.52% of control, p = 0.0004). VCA demonstrated more potent effects, with significant reductions in nuclei count at all tested concentrations: 1 ng/mL (118 nuclei per field, 49.37% of control, p = 0.0063), 10 ng/mL (41 nuclei per field, 17.15% of control, p = 0.0002), and 50 ng/mL (29 nuclei per field, 12.13% of control, p = 0.0001). The combination of DOX and VCA caused a further decrease in the number of nuclei per field. Notably, the lowest concentration of DOX and VCA (1 ng/mL) also produced a statistically significant reduction in the number of nuclei per field (101 nuclei per field, 42.26% of control, p = 0.0005). The combination of 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA further decreased the count to 17 nuclei per field (7.11% of control, p = 0.00008), while 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA showed the most dramatic reduction to 14 nuclei per field (5.86% of control, p = 0.00006). These results show that the DOX-VCA combination is more effective in reducing the cell number than either of the compounds alone, even at lower concentrations.

Figure 7: Effects of DOX and VCA on MDA-MB231 cell viability and nuclear morphology. Cells were treated with various concentrations of DOX and VCA for 48 h. DAPI staining shows nuclear morphology with quantification of nuclei per field presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Live/dead cell staining with calcein-AM (live cells, green) and ethidium homodimer-1 (dead cells, red) demonstrates cell viability, with stacked bar graphs showing the percentage distribution of live and dead cells. Total cell count was determined by summing calcein-AM-positive and ethidium homodimer-positive cells. Data represent the mean from three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared to control was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. * represents significance for dead cells and † represents significance for live cells: */†: p < 0.05, **/††: p < 0.01, ***/†††: p < 0.001

Further information on the cell viability was obtained by using Live/dead cell staining with calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer (Fig. 7) after 48 h of treatment. DOX alone reduced the percentage of live cells in a dose-dependent manner; the differences were statistically significant at 50 ng/mL (71.77% live cells, p = 0.0058). VCA had more significant effects on cell viability. Significant reductions in live cells were observed at 1 ng/mL (61.81% live cells, p = 0.0047), 10 ng/mL (31.03% live cells, p = 0.0003), and 50 ng/mL (18.18% live cells, p = 0.0001). The combination treatment led to a greater reduction in the percentage of viable cells. The treatment of 1 ng/mL DOX + 1 ng/mL VCA reduced live cells to 48.12% (p = 0.0006). Higher doses showed stronger effects: 10 ng/mL DOX + 10 ng/mL VCA (23.53% live cells, p = 0.0002) and 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA (15.09% live cells, p = 0.0001). Similarly, the proportion of dead cells increased with treatment. The highest effect was seen at 50 ng/mL DOX + 50 ng/mL VCA, where dead cells increased to 84.91% (p = 0.0001).

Our study demonstrates that the combination of DOX and VCA exhibits strong synergistic cytotoxicity against MDA-MB231 TNBC cells, with Bliss Independence scores ranging from +29.7% to +33.4% at therapeutic concentrations and remarkable dose reduction indices (>3000-fold for DOX, >15-fold for VCA). This synergistic effect was accompanied by coordinated changes in multiple cellular processes: enhanced modulation of oxidative stress markers (48% increase in SOD-like activity and 94% increase in NO production), augmented apoptotic responses (4.8-fold increase in cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio and 91% reduction in procaspase-9 levels), significant inhibition of cell migration (85.8% remaining wound area at 48 h), and severely impaired proliferative recovery (98.9% reduction in cell viability at 72 h post-treatment). These findings suggest that VCA could potentially serve as an effective adjuvant to reduce DOX dosage while maintaining or enhancing therapeutic efficacy in TNBC treatment.

The DOX-VCA combination showed synergistic cytotoxicity, especially at therapeutic concentrations, which can be beneficial for the treatment of TNBC. Bliss Independence analysis revealed the strongest synergy at clinically relevant concentration ranges, with the most pronounced effects observed at lower doses. The DRI demonstrated that DOX could be used at substantially lower doses when combined with VCA, potentially minimizing dose-dependent cardiotoxicity while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [32]. Similar synergistic effects have been observed with other plant-derived compounds in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, thus supporting the possibility of such combinations in cancer treatment [33]. Based on the synergy analysis results, concentrations were selected to represent different effect levels for subsequent mechanistic studies. This range enabled us to assess the impact of both compounds separately and in combination on numerous cellular processes and to gain information on the mechanisms of action and possible cooperation at different levels of cytotoxicity. A key implication of the observed synergistic effect between DOX and VCA is the potential for dose reduction strategies that warrant further investigation. This is particularly important because DOX has been known to have dose-dependent cardiotoxicity [32]. Our in vitro findings suggest that DOX may potentially be used at a lower concentration when combined with VCA while maintaining cytotoxic efficacy against TNBC cells. If validated through in vivo studies and clinical trials, this dose reduction approach could potentially offer several advantages in the treatment of TNBC. First, it may hypothetically reduce the risk of cardiotoxicity, which is one of the main drawbacks of DOX-based therapies. Second, it might enable longer duration of treatment or multiple treatment regimens, though this requires systematic evaluation in appropriate models. While our data provide a promising foundation, the translation of these in vitro observations to clinical benefits, including potential improvements in patient quality of life and treatment compliance, remains a hypothesis requiring rigorous validation through preclinical and clinical studies.

The dose-reduction indices demonstrated in our study, particularly the >3000-fold reduction for DOX, warrant discussion regarding their physiological relevance. The concentrations tested in our study (0.001–100 ng/mL) fall within clinically achievable ranges for both agents. For doxorubicin, therapeutic plasma concentrations typically range from 0.5–25 μg/mL following standard dosing, with sustained infusion maintaining levels of 100–250 ng/mL [34,35]. Our experimental concentrations are therefore well below typical clinical exposures, suggesting potential for dose reduction strategies. Regarding VCA, pharmacokinetic studies of mistletoe preparations have shown that following subcutaneous administration of 20 mg, peak plasma concentrations of mistletoe lectins reach 3.7–56 ng/mL [6,36]. The VCA concentrations demonstrating synergy in our study (0.1–50 ng/mL) are within this clinically achievable range. This is particularly relevant as mistletoe extracts are widely used in integrative oncology with established safety profiles at these doses [7].

In order to elucidate the mechanisms of this synergistic effect, we analyzed the effect of the DOX-VCA combination on cellular oxidative stress markers. The DOX-VCA combination affected the cellular redox status as indicated by changes in SOD-like activity and NO levels. Interestingly, VCA treatment alone, and more significantly in combination with DOX, increased SOD-like activity. This enhancement of antioxidant activity is in accordance with previous studies demonstrating the antioxidant properties of mistletoe extracts [15,37]. Also, our results revealed an increase in NO production with VCA treatment and the DOX-VCA combination. This raises a paradox in the cellular response. Even though NO can have protective effects at low concentrations, high levels of NO can cause the formation of peroxynitrite, which is a potent oxidant and can cause cell death [38]. This dual nature of NO has been observed across multiple natural product systems with redox-modulating properties. Similar paradoxical effects have been documented with curcumin, where low concentrations exhibit antioxidant activity while higher concentrations induce oxidative stress and apoptosis in cancer cells through ROS and reactive nitrogen species generation [39,40]. Resveratrol, another polyphenolic compound, demonstrates comparable concentration-dependent redox modulation, acting as an antioxidant at physiological concentrations but switching to a pro-oxidant mode in cancer cells by increasing ROS and NO production [41]. Chitosan and its derivatives have also been shown to modulate cellular redox balance by enhancing SOD activity and regulating NO levels, with their metal-chelating properties contributing to selective oxidative stress in malignant cells while protecting normal tissues [42]. The selective cytotoxicity observed with the DOX-VCA combination may be related to fundamental differences in redox homeostasis between cancer and normal cells. Cancer cells, including TNBC, have been shown to exhibit elevated baseline levels of reactive oxygen species compared to their normal counterparts due to metabolic reprogramming and increased activity of ROS-generating systems [43,44]. This elevated oxidative stress in cancer cells creates a narrower therapeutic window before reaching cytotoxic thresholds. Specifically, TNBC has been characterized by high expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which correlates with poor prognosis, increased metastasis, and aggressive tumor behavior [45]. The elevated iNOS expression contributes to higher baseline NO production in TNBC cells, and further increases in NO levels—such as those induced by the DOX-VCA combination—may more readily exceed the cytotoxic threshold in these cells. In contrast, normal cells typically maintain lower baseline ROS and NO levels along with more robust antioxidant defense systems [43], which may provide a mechanistic basis for the differential sensitivity to pro-oxidant therapies. Conventional anticancer agents like doxorubicin function as pro-oxidants that selectively drive ROS levels above death-inducing thresholds in cancer cells due to their pre-existing oxidative stress [44]. This duality of NO in cancer has been reported by Choudhari et al., where NO has been seen to have both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic effects depending on concentration [46]. The enhancement of SOD-like activity and NO production with the DOX-VCA combination indicates that the redox processes in the cell are interconnected. While our study demonstrates coordinated changes in oxidative stress markers associated with DOX-VCA synergistic cytotoxicity in TNBC cells, comparative studies using both cancer and normal cell lines are needed to directly assess the selective toxicity and to elucidate the causal relationships among the observed pathway changes and identify potential master regulatory mechanisms.

Although the modulation of oxidative stress markers gives an understanding of the changes in the cellular redox state induced by DOX-VCA combination, these changes in the cellular environment are often the precursors of more definitive cell fate decisions. One of the most important consequences of such cellular stress is apoptosis, a programmed cell death that is essential for the efficacy of anticancer treatments. The relationship between oxidative stress and apoptosis is well described in cancer research, with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species frequently involved in the regulation of apoptotic signaling [38,47,48]. DOX is well-established to induce apoptosis primarily through DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction [11], while mistletoe preparations have been reported to activate apoptotic pathways through multiple mechanisms, including STAT3 signaling pathway regulation in breast cancer cells [17] and immunomodulation [17,49]. Natural products have been demonstrated to induce apoptosis through diverse mechanisms, including mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress in TNBC [14]. Our observations of enhanced caspase activation with the DOX-VCA combination are consistent with coordinated modulation of multiple apoptotic markers. The changes in DNA damage-related pathways by DOX and STAT3-related markers by mistletoe preparations were observed concurrently with the potentiated apoptotic response in our study, though the causal relationships among these pathways remain to be determined. In addition, the enhanced NO release observed earlier may be involved in the apoptotic process, as oxidative stress mediators can directly trigger apoptotic cascades in cancer cells [49]. The coordinated changes in oxidative stress markers and apoptotic indicators following DOX-VCA treatment suggest potential convergence of multiple pathways, though the precise mechanistic hierarchy requires further investigation.

Even though the induction of apoptosis is essential for immediate cytotoxicity, the overall effectiveness of cancer therapies in the long run may be determined by their capacity to suppress tumor recurrence. Preventing proliferative recovery is particularly critical in TNBC, which is characterized by high rates of recurrence and resistance to treatment [3]. DOX is known to cause long-term DNA damage by inhibiting topoisomerase II and generating free radicals, which results in cell cycle arrest or senescence [32]. Natural products and their extracts have been shown to cause endoplasmic reticulum stress and inhibit protein synthesis, effects that can persist beyond the immediate treatment period [14]. The coordinated changes in multiple cellular processes observed with the DOX-VCA combination may contribute to sustained inhibition of cellular proliferation [50]. The concurrent modulation of DNA damage-related markers and stress response pathways was associated with the impaired capacity of cells to regain proliferative potential following treatment cessation. In addition, the long-lasting effect seen in the present study may be related to the increased oxidative stress and NO production. Long-term changes in the cellular redox balance may cause epigenetic modifications and metabolic changes that may affect the long-term cell behavior [38].

To support our biochemical and functional data and to give visual proof of the cellular alterations caused by the DOX-VCA treatment, we used fluorescence microscopy. Nuclear condensation and fragmentation observed through DAPI staining are well-established morphological hallmarks of apoptosis [51]. These characteristic changes reflect the progression of programmed cell death and correspond with the activation of apoptotic pathways. The nuclear morphological alterations observed with DOX and VCA treatments, particularly in combination, are consistent with our biochemical findings of elevated cleaved caspase-3 levels, demonstrating convergence between morphological and biochemical evidence. Live/dead cell staining with calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer-1 provides functional assessment of plasma membrane integrity, a critical determinant of cell viability [52]. The loss of membrane integrity represents a key feature of apoptotic cell death, while calcein-AM retention indicates maintained esterase activity and intact membranes in viable cells. The imaging patterns observed with the DOX-VCA combination support the integration of multiple cell death mechanisms. The coordinate changes in nuclear morphology and membrane integrity are consistent with our earlier observations of increased oxidative stress markers and caspase activation, suggesting that the combination treatment engages multiple pathways leading to enhanced cytotoxicity. Fluorescence microscopy provides visual confirmation that complements our quantitative biochemical assays, revealing the extent of treatment effects across the cell population. These morphological findings strengthen the interpretation that DOX and VCA act synergistically through the activation of multiple apoptotic mechanisms [51,52].

Our findings suggest several potential implications that warrant further investigation through preclinical validation. The observed modulation of oxidative stress markers by the DOX-VCA combination may contribute to the synergistic cytotoxicity, though the precise mechanisms require elucidation in more complex model systems. The effects on cell migration observed in our in vitro wound healing assay raise the possibility of anti-metastatic activity; however, metastatic behavior involves complex interactions with the tumor microenvironment that cannot be fully recapitulated in monolayer culture systems. Similarly, while the impaired proliferative recovery following treatment cessation suggests potential for reducing recurrence risk, validation in appropriate animal models would be essential to determine whether these effects translate to clinically relevant tumor suppression. If confirmed through systematic preclinical studies, such properties could be relevant for addressing the aggressive clinical behavior of TNBC, though considerable additional investigation would be required before any clinical implications could be considered. These results align with previous observations on the anticancer properties of mistletoe-derived compounds and other natural products in combination with conventional chemotherapy [50]. We previously demonstrated apoptosis induction by VCA in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [20], while Park et al. showed effects of mistletoe extract combined with chemotherapy drugs in various breast cancer cell lines [17]. These parallels suggest that similar mechanisms may operate across different breast cancer cell types, though a comprehensive evaluation across multiple TNBC cell lines would be necessary to establish broader applicability.

Important limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The use of a single TNBC cell line (MDA-MB-231) limits the generalizability of our findings across the heterogeneous TNBC subtype. Although our previous work demonstrated VCA’s cytotoxic activity in BT-549 cells and selective toxicity compared to MCF-10A normal breast epithelial cells [53], the DOX-VCA combination specifically requires validation across multiple TNBC cell lines and normal cell comparisons to confirm broader applicability and therapeutic selectivity. The in vitro nature of our experiments cannot capture the complexity of tumor biology, including interactions with the immune system, stromal components, and the challenges of drug delivery to solid tumors. Therefore, rigorous in vivo validation using appropriate xenograft or orthotopic models would be a critical next step to assess the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, safety profile, and potential cardioprotective benefits of this combination.

Several key translational challenges must be addressed before clinical application can be considered. First, as a protein-based therapeutic, VCA faces bioavailability and delivery challenges inherent to lectin-based agents. Pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that subcutaneous administration of mistletoe lectins achieves only approximately 56% systemic bioavailability [54], and protein therapeutics are generally susceptible to enzymatic degradation in biological fluids and exhibit limited tissue penetration [55]. The in vivo stability of VCA and its optimal formulation for systemic administration require systematic investigation, as protein drugs are prone to aggregation and loss of bioactivity under physiological conditions [56]. Second, while our in vitro findings suggest selective toxicity toward cancer cells based on differential redox homeostasis, the potential for normal tissue toxicity must be rigorously evaluated in animal models, as protein therapeutics can exhibit unforeseen toxicities in vivo that are not predicted by cell culture studies [57]. Third, the pharmacokinetic profiles of DOX and VCA differ substantially as small-molecule chemotherapeutics and protein-based agents demonstrate distinct distribution, metabolism, and clearance patterns [58]. This necessitates careful optimization of dosing schedules and administration routes to achieve synchronized effective drug concentrations at tumor sites while minimizing systemic exposure and off-target effects. Only after such preclinical validation could the potential clinical relevance of this approach be meaningfully evaluated.

Our in vitro results demonstrate that the DOX-VCA combination exhibits synergistic cytotoxicity, enhanced apoptotic responses, inhibition of cell migration, and impaired proliferative recovery in TNBC cells through coordinated modulation of oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways [3,51,59]. These mechanistic findings provide a foundation for further preclinical investigation of this combination in animal models of TNBC.

Several critical translational barriers must be addressed before clinical application can be considered. First, as a protein-based therapeutic, VCA faces bioavailability and delivery challenges, with subcutaneous administration of mistletoe lectins achieving only approximately 56% systemic bioavailability (Doehmer et al., 2011). Second, while existing literature suggests that mistletoe lectins show relatively low toxicity in vivo [60], the toxicity profile of the DOX-VCA combination specifically has not been evaluated, and our in vitro findings of selective cytotoxicity require validation in animal models. Third, although our results suggest potential for dose reduction, the hypothesis that lower DOX doses in combination with VCA could reduce cardiotoxicity [32] while maintaining efficacy requires rigorous pharmacokinetic and toxicological evaluation in appropriate preclinical models. Finally, the pharmacokinetic profiles of small-molecule chemotherapeutics like DOX and protein-based agents like VCA differ substantially, necessitating careful optimization of dosing schedules and administration routes.

Despite these challenges, our findings suggest that the DOX-VCA combination warrants further investigation in preclinical models. The observed anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects in vitro could be relevant for challenging clinical scenarios such as ipsilateral TNBC recurrence, where novel treatment approaches are urgently needed [61]. Future studies should comprehensively elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed synergistic effects through transcriptomics and proteomics approaches, evaluate the combination in patient-derived xenograft models to assess in vivo efficacy and safety, determine optimal dosing schedules and pharmacokinetic profiles, and investigate potential cardioprotective effects at reduced DOX doses. Only after addressing these translational challenges through systematic preclinical validation can the potential clinical relevance of this approach be meaningfully evaluated.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Su-Yun Lyu; methodology, Chang-Eui Hong; validation, Chang-Eui Hong; formal analysis, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; investigation, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; resources, Su-Yun Lyu; data curation, Chang-Eui Hong; writing—original draft preparation, Chang-Eui Hong; writing—review and editing, Su-Yun Lyu; visualization, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; supervision, Su-Yun Lyu; project administration, Su-Yun Lyu; funding acquisition, Su-Yun Lyu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Akt/PKB | Protein knase B |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| DRI | Dose reduction index |

| ECL | Enhanced chemiluminescence |

| ELLA | Enzyme-linked lectin assay |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation assay |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| VCA | Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin |

References

1. Howard FM, Olopade OI. Epidemiology of triple-negative breast cancer: a review. Cancer J. 2021;27(1):8–16. doi:10.1097/PPO.0000000000000500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chen IE, Lee-Felker S. Triple-negative breast cancer: multimodality appearance. Curr Radiol Rep. 2023;11(4):53–9. doi:10.1007/s40134-022-00410-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zagami P, Carey LA. Triple negative breast cancer: pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):95. doi:10.1038/s41523-022-00468-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bustamante E, Casas F, Luque R, Piedra L, Barros-Sevillano S, Chambergo-Michilot D, et al. Brain metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast J. 2024;2024(1):8816102. doi:10.1155/2024/8816102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Patel G, Prince A, Harries M. Advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2024;40(1):151548. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2023.151548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Schad F, Axtner J, Kröz M, Matthes H, Steele ML. Safety of combined treatment with monoclonal antibodies and Viscum album L preparations. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(1):41–51. doi:10.1177/1534735416681641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Melzer J, Iten F, Hostanska K, Saller R. Efficacy and safety of mistletoe preparations (Viscum album) for patients with cancer diseases. A systematic review. Forsch Komplementmed. 2009;16(4):217–26. doi:10.1159/000226249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Oei SL, Thronicke A, Schad F. Mistletoe and immunomodulation: insights and implications for anticancer therapies. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2019;2019(8):5893017. doi:10.1155/2019/5893017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kienle GS, Kiene H. Review article: influence of Viscum album L (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9(2):142–57. doi:10.1177/1534735410369673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Li L, Zhang F, Liu Z, Fan Z. Immunotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer: combination strategies to improve outcome. Cancers. 2023;15(1):321. doi:10.3390/cancers15010321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cheong A, McGrath S, Robinson T, Maliki R, Spurling A, Lock P, et al. A switch in mechanism of action prevents doxorubicin-mediated cardiac damage. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;185(9938):114410. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen R, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhu L, Zhang X, Ma Y, et al. Progress on the mechanism of action of emodin against breast cancer cells. Heliyon. 2024;10(21):e38628. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Nyangwara VA, Mazhindu T, Chikwambi Z, Masimirembwa C, Campbell TB, Borok M, et al. Cardiotoxicity and pharmacogenetics of doxorubicin in black Zimbabwean breast cancer patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;90(8):1782–9. doi:10.1111/bcp.15659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chen H, Yang J, Yang Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, Lu X. The natural products and extracts: anti-triple-negative breast cancer in vitro. Chem Biodivers. 2021;18(7):e2001047. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202001047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Nicoletti M. The anti-inflammatory activity of Viscum album. Plants. 2023;12(7):1460. doi:10.3390/plants12071460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Schröder L, Hohnjec N, Senkler M, Senkler J, Küster H, Braun HP. The gene space of European mistletoe (Viscum album). Plant J. 2022;109(1):278–94. doi:10.1111/tpj.15558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Park YR, Jee W, Park SM, Kim SW, Bae H, Jung JH, et al. Viscum album induces apoptosis by regulating STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):11988. doi:10.3390/ijms241511988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Shin J, Yim E, Kang CM. Viscum album, as alternative and bridge to palliative chemotherapy in recurrent gallbladder cancer following laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy: a case report. Korean J Clin Oncol. 2023;19(2):88–92. doi:10.14216/kjco.23016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hong CE, Park AK, Lyu SY. Synergistic anticancer effects of lectin and doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;394(1–2):225–35. doi:10.1007/s11010-014-2099-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hong CE, Lyu SY. Modulation of breast cancer cell apoptosis and macrophage polarization by mistletoe lectin in 2D and 3D models. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(15):8459. doi:10.3390/ijms25158459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lyu SY, Park WB, Choi KH, Kim WH. Involvement of caspase-3 in apoptosis induced by Viscum album var. coloratum agglutinin in HL-60 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65(3):534–41. doi:10.1271/bbb.65.534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ho C, Yun L, Bong P. Mistletoe lectin induces apoptosis and telomerase inhibition in human A253 cancer cells through dephosphorylation of Akt. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27(1):68–76. doi:10.1007/BF02980049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Fatfat Z, Fatfat M, Gali-Muhtasib H. Therapeutic potential of thymoquinone in combination therapy against cancer and cancer stem cells. World J Clin Oncol. 2021;12(7):522–43. doi:10.5306/wjco.v12.i7.522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Park WB, Han SK, Lee MH, Han KH. Isolation and characterization of lectins from stem and leaves of Korean mistletoe (Viscum album var. coloratum) by affinity chromatography. Arch Pharm Res. 1997;20(4):306–12. doi:10.1007/BF02976191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hong CE, Lyu SY. Comparative anticancer mechanisms of Viscum album var. coloratum water extract and its lectin on primary and metastatic melanoma cells. Biocell. 2025;49(2):289–314. doi:10.32604/biocell.2025.061334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hong CE, Lyu SY. Mistletoe lectin induces apoptosis and modulates the cell cycle in YD38 oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Biocell. 2025;49(2):269–88. doi:10.32604/biocell.2025.060411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lyu SY, Park WB. Mistletoe lectin (Viscum album coloratum) modulates proliferation and cytokine expressions in murine splenocytes. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;39(6):662–70. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.6.662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bliss CI. The toxicity of poisons applied jointly. Ann Appl Biol. 1939;26(3):585–615. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1939.tb06990.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ianevski A, Giri AK, Aittokallio T. SynergyFinder 2.0: visual analytics of multi-drug combination synergies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W488–93. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wang QH, Yu LJ, Liu Y, Lin L, Lu RG, Zhu JP, et al. Methods for the detection and determination of nitrite and nitrate: a review. Talanta. 2017;165:709–20. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2016.12.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N] nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126(1):131–8. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Singh M, Nicol AT, DelPozzo J, Wei J, Singh M, Nguyen T, et al. Demystifying the relationship between metformin, AMPK, and doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:839644. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.839644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Dasari S, Njiki S, Mbemi A, Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB. Pharmacological effects of cisplatin combination with natural products in cancer chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1532. doi:10.3390/ijms23031532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Danesi R, Conte PF, Del Tacca M. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of treatment schedules for anthracyclines and paclitaxel in patients with cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37(3):195–211. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937030-00002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wiebe VJ, Benz CC, DeGregorio MW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of drugs used in the treatment of breast cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;15(3):180–93. doi:10.2165/00003088-198815030-00003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Huber R, Lüdtke H, Wieber J, Beckmann C. Safety and effects of two mistletoe preparations on production of Interleukin-6 and other immune parameters-a placebo controlled clinical trial in healthy subjects. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11(1):116. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-11-116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Nicoletti M. The antioxidant activity of mistletoes (Viscum album and other species). Plants. 2023;12(14):2707. doi:10.3390/plants12142707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ju S, Singh MK, Han S, Ranbhise J, Ha J, Choe W, et al. Oxidative stress and cancer therapy: controlling cancer cells using reactive oxygen species. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(22):12387. doi:10.3390/ijms252212387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Komarova TV, Sheshukova EV, Kosobokova EN, Kosorukov VS, Shindyapina AV, Lipskerov FA, et al. The biological activity of bispecific trastuzumab/pertuzumab plant biosimilars may be drastically boosted by disulfiram increasing formaldehyde accumulation in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16168. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-52507-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pouliquen DL, Boissard A, Henry C, Coqueret O, Guette C. Curcuminoids as modulators of EMT in invasive cancers: a review of molecular targets with the contribution of malignant mesothelioma studies. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:934534. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.934534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wan Z, Hallajzadeh J. The beneficial effects of resveratrol on hepatocellular carcinoma and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: modulation of apoptosis, autophagy, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Food Sci Nutr. 2025;13(7):e70555. doi:10.1002/fsn3.70555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ivanova DG, Yaneva ZL. Antioxidant properties and redox-modulating activity of chitosan and its derivatives: biomaterials with application in cancer therapy. Biores Open Access. 2020;9(1):64–72. doi:10.1089/biores.2019.0028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Aykin-Burns N, Ahmad IM, Zhu Y, Oberley LW, Spitz DR. Increased levels of superoxide and H2O2 mediate the differential susceptibility of cancer cells versus normal cells to glucose deprivation. Biochem J. 2009;418(1):29–37. doi:10.1042/BJ20081258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Sun J, Patel CB, Jang T, Merchant M, Chen C, Kazerounian S, et al. High levels of ubidecarenone (oxidized CoQ(10)) delivered using a drug-lipid conjugate nanodispersion (BPM31510) differentially affect redox status and growth in malignant glioma versus non-tumor cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13899. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70969-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Granados-Principal S, Liu Y, Guevara ML, Blanco E, Choi DS, Qian W, et al. Inhibition of iNOS as a novel effective targeted therapy against triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):25. doi:10.1186/s13058-015-0527-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Choudhari SK, Chaudhary M, Bagde S, Gadbail AR, Joshi V. Nitric oxide and cancer: a review. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11(1):118. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Nizami ZN, Aburawi HE, Semlali A, Muhammad K, Iratni R. Oxidative stress inducers in cancer therapy: preclinical and clinical evidence. Antioxidants. 2023;12(6):1159. doi:10.3390/antiox12061159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Azmanova M, Pitto-Barry A. Oxidative stress in cancer therapy: friend or enemy? Chembiochem. 2022;23(10):e202100641. doi:10.1002/cbic.202100641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Li K, Fan C, Chen J, Xu X, Lu C, Shao H, et al. Role of oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(10):e18399. doi:10.1111/jcmm.18399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jung T, Cheon C. Synergistic and additive effects of herbal medicines in combination with chemotherapeutics: a scoping review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2024;23:15347354241259416. doi:10.1177/15347354241259416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang M, Meng M, Liu Y, Qi J, Zhao Z, Qiao Y, et al. Triptonide effectively inhibits triple-negative breast cancer metastasis through concurrent degradation of Twist1 and Notch1 oncoproteins. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):116. doi:10.1186/s13058-021-01488-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Marsolier J, Prompsy P, Durand A, Lyne AM, Landragin C, Trouchet A, et al. H3K27me3 conditions chemotolerance in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2022;54(4):459–68. doi:10.1038/s41588-022-01047-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Lyu SY, Meshesha SM, Hong CE. Synergistic effects of mistletoe lectin and cisplatin on triple-negative breast cancer cells: insights from 2D and 3D in vitro models. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):366. doi:10.3390/ijms26010366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Doehmer J, Eisenbraun J. Assessment of extracts from mistletoe (Viscum album) for herb-drug interaction by inhibition and induction of cytochrome P450 activities. Phytother Res. 2012;26(1):11–7. doi:10.1002/ptr.3473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Bruno BJ, Miller GD, Lim CS. Basics and recent advances in peptide and protein drug delivery. Ther Deliv. 2013;4(11):1443–67. doi:10.4155/tde.13.104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Wallis L, Kleynhans E, Toit TD, Gouws C, Steyn D, Steenekamp J, et al. Novel non-invasive protein and peptide drug delivery approaches. Protein Pept Lett. 2014;21(11):1087–101. doi:10.2174/0929866521666140807112148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Ensign LM, Cone R, Hanes J. Oral drug delivery with polymeric nanoparticles: the gastrointestinal mucus barriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(6):557–70. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2011.12.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Choi YH, Zhang C, Liu Z, Tu MJ, Yu AX, Yu AM. A novel integrated pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model to evaluate combination therapy and determine in vivo synergism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2021;377(3):305–15. doi:10.1124/jpet.121.000584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Klingemann H. Viscum album (mistletoe) extract for dogs with cancer? Front Vet Sci. 2024;10:1285354. doi:10.3389/fvets.2023.1285354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Baek SY, Kim J, Chung IY, Ko BS, Kim HJ, Lee JW, et al. Chemotherapy for ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence: a propensity score-matching study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;192(1):143–52. doi:10.1007/s10549-021-06493-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools