Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Role of Platelet Derivatives and Their Therapeutic Potential in Wound Healing

1 Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology and Platelet Signaling, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, 28644, Republic of Korea

2 Cancer Research Center, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, 28644, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Soochong Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2335-2364. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072418

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 30 September 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Regenerative medicine has attracted increasing attention across diverse organs, including the skin, musculoskeletal tissues, eye, and nervous system, where structural repair is limited. Among these, skin wound care is particularly urgent and challenging because diabetic ulcers, pressure injuries, and severe burns often resist standard dressings, debridement, and revascularization, resulting in infection, amputation, and high costs. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has gained value because platelets release coordinated growth factors and cytokines (e.g., platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor-1) that modulate hemostasis, inflammation, angiogenesis, fibroplasia, and re-epithelialization. PRP provides concentrated multiple growth factors and, owing to its autologous nature, shows low immunogenicity. Even allogeneic or xenogeneic PRP is generally considered to evoke minimal immune responses, positioning PRP as a promising and effective treatment. Recently, diverse platelet derivatives developed through processing and formulation have enabled more efficient applications and long-term storage. Nevertheless, substantial issues remain, including the lack of standardized preparation protocols, unclear dosing and retreatment schedules, potential disease-specific adverse effects, and donor-dependent variability in blood quality. Here, we review platelet-mediated mechanisms of wound healing, summarize the efficacy and clinical use of platelet derivatives, and discuss unresolved issues with potential solutions. These insights may support more efficient and effective use of platelets and PRP in wound care while advancing their translation across regenerative medicine.Keywords

Platelets are anucleate, disc-shaped cellular fragments derived from megakaryocytes. Their production is regulated by thrombopoietin synthesized mainly in the liver. These fragments play a fundamental role in hemostasis and blood coagulation. After vascular injury, exposed collagen and von Willebrand factor (vWF) bind to glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and glycoprotein Ib (GPIb) receptors on platelets. This interaction initiates platelet activation and adhesion to the damaged vessel wall. This process induces shape change, granule secretion, and recruitment of additional platelets. It triggers vasoconstriction and formation of a platelet plug through GPIIb/IIIa fibrinogen binding, forming the primary hemostatic response. As this phase depends heavily on platelet function, dysfunction may result in bleeding disorders [1]. Platelets also release factors, such as thromboplastin, which activate plasma coagulation factors. The generated thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin, stabilizing the platelet plug and completing secondary hemostasis [2].

In addition to their roles in hemostasis and thrombosis, platelets contribute to wound healing, immune responses, and tumor metastasis. Activated platelets secrete molecules, such as P-selectin, CD40L, and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). These mediators recruit and activate leukocytes, thereby promoting inflammation and clearance of debris and pathogens at the injury site [3]. Platelet α-granules store and release growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). These growth factors stimulate proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis in wound tissues. Although they promote tissue repair, they may also promote tumor growth and metastasis under pathological conditions [3–5]. Thus, platelets play multifaceted roles in human physiology, and their functional components can be harnessed for therapeutic applications.

Given the aforementioned roles, platelets have been widely applied in regenerative medicine, most commonly as platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Recently, depending on clinical purpose (e.g., orthopedic, dermatologic, dental, plastic surgery, and chronic wound healing), application method (solid or liquid forms), and duration (short- or long-term), various platelet derivatives, including PRP, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet lysate (PL), platelet exosomes, lyophilized platelets, and platelet gels, have emerged. These derivatives are often combined with scaffolds such as collagen, gelatin, fibrin, hyaluronic acid, poly lactic-co-glycolic acid, chitosan, or silk to enhance therapeutic efficacy [6–9]. In this study, we describe in detail the mechanisms through which platelets promote wound healing and introduce various platelet derivatives developed based on these mechanisms. In addition to wound healing potential, we discuss the broader biological effects of these derivatives to provide clinical and research guidelines for their application.

2 Mechanism of Wound Healing Effect Using Platelets

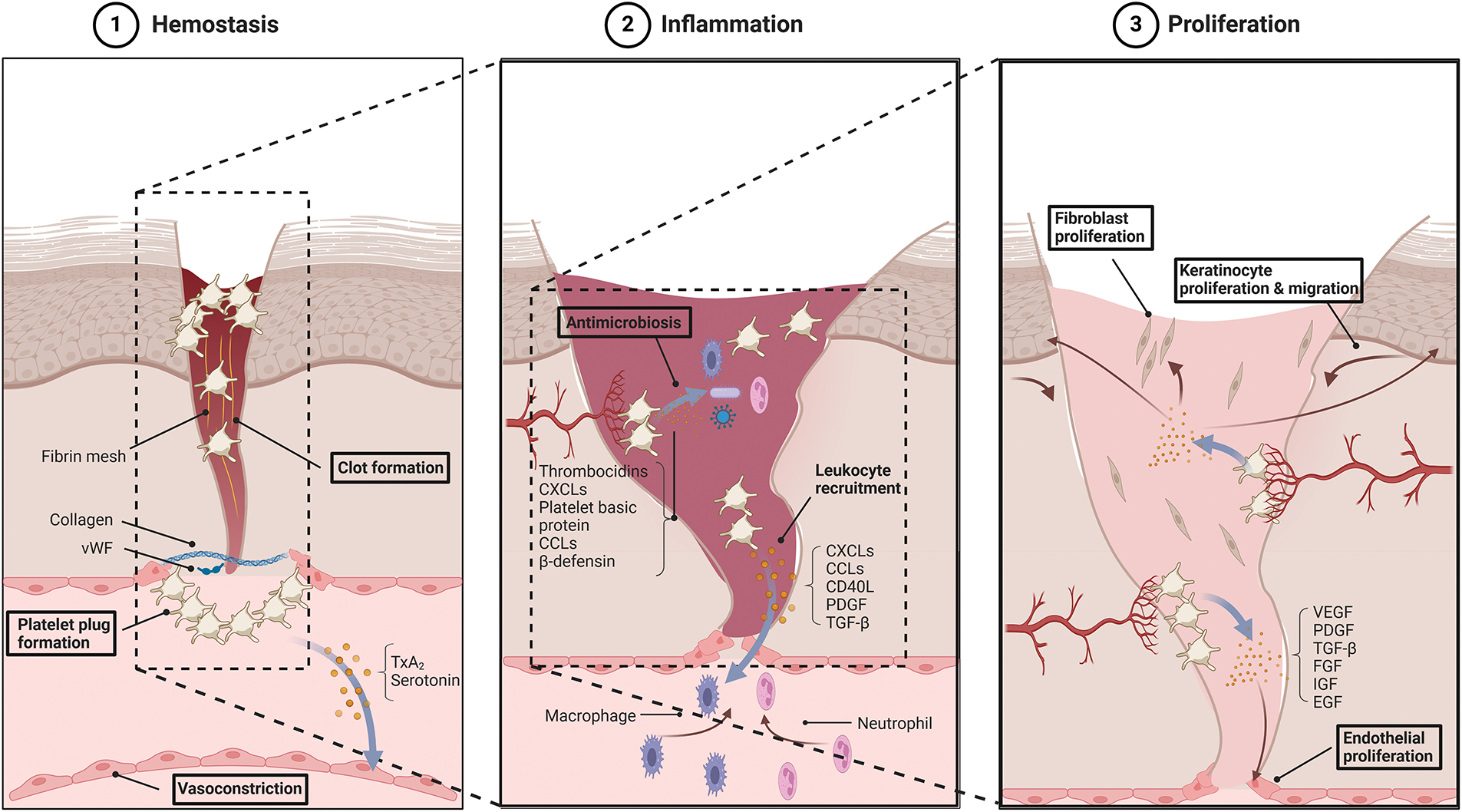

Wound healing is a complex physiological process that restores the structure and function of damaged tissue. It is typically divided into four sequential but overlapping stages, namely, hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. The hemostasis phase minimizes blood loss and temporarily seals the wound, and the inflammatory phase clears pathogens and cellular debris. The proliferative phase involves the formation of new tissue, and the remodeling phase gradually restores the structural and functional integrity of the tissue. Platelets play either a direct or indirect role in these phases. To elucidate their contribution in wound healing, we initially explore the mechanisms of action in each phase (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Platelet roles in each phase of wound healing. Platelets act in all stages of wound healing, including hemostasis, inflammation, and proliferation. During hemostasis, platelets promote platelet plug formation, fibrin clot formation, and vasoconstriction; during inflammation, they mediate leukocyte recruitment and antimicrobiosis; during proliferation, they support the proliferation of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes to drive wound repair. Abbreviation: vWF, von Willebrand factor; TxA2, thromboxane A2; CXCLs, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; CCL, C-C chemokine ligand; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor

Hemostasis, the first stage of wound healing, includes more than the initial cessation of bleeding. It establishes a foundation for the subsequent tissue repair. Under physiological conditions, platelets circulate in an inactive state. Following vascular injury, immediate vasoconstriction reduces blood loss; primary and secondary hemostasis then form a stable clot.

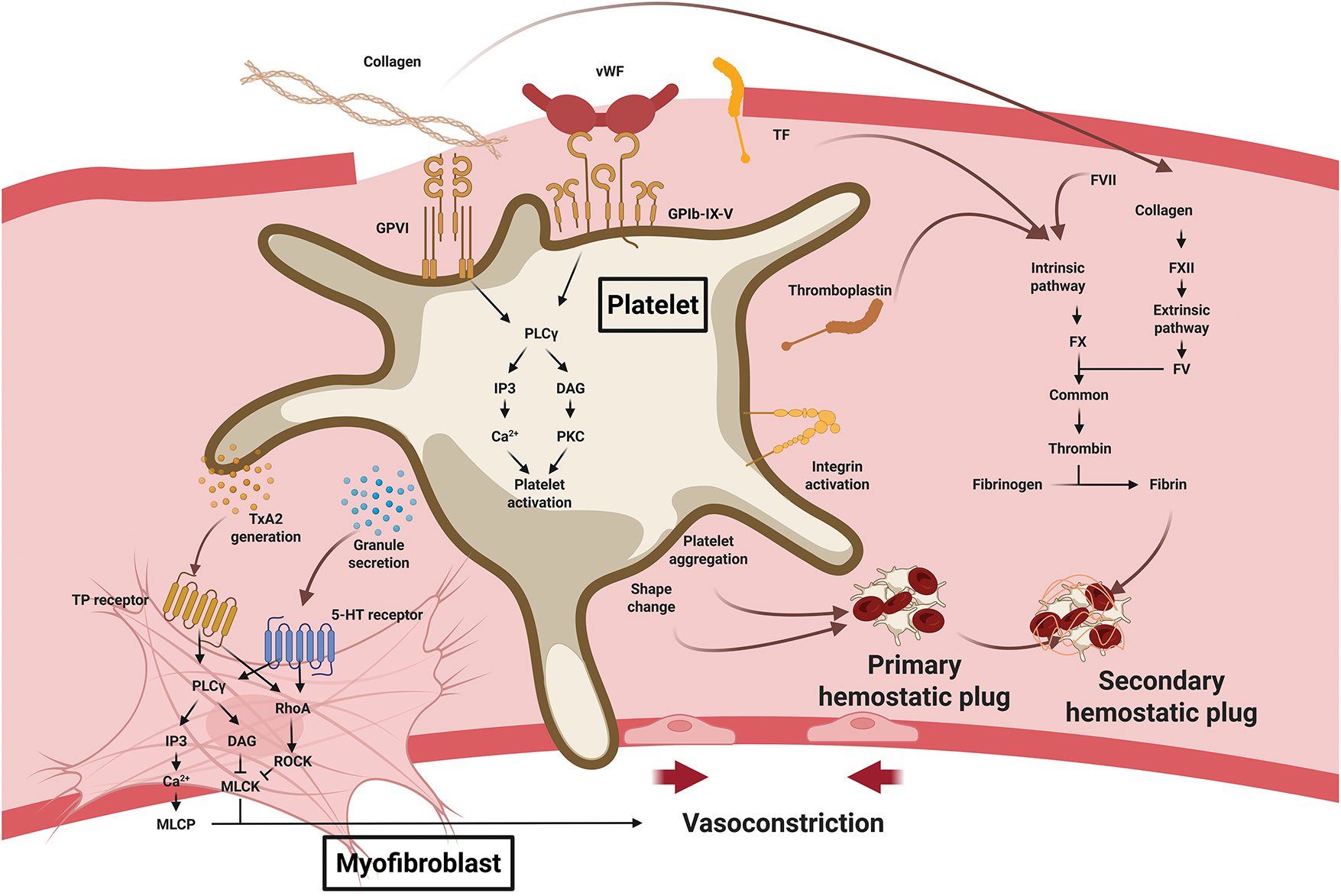

Vasoconstriction, the initial hemostatic response, is primarily mediated by vasoconstrictors such as endothelin released from damaged endothelial cells and catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine) and prostaglandins released from injured tissue. During primary hemostasis, platelets adhere to exposed collagen and vWF at the site of injury, become activated, and initiate granule secretion. Activated platelets synthesize thromboxane A2 (TxA2) from membrane phospholipids and release serotonin from dense granules (Fig. 2). TxA2 binds to TP receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells and activates Gq-protein-coupled phospholipase C (PLC), which generates inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) [10]. IP3 induces calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, increasing intracellular calcium levels and activating myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). MLCK phosphorylates MLC and induces smooth muscle contraction. Concurrently, DAG inhibits myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP), enhancing contraction [11]. TP receptors also activate the Rho/Rho kinase pathway via G12/13 proteins, further inhibiting MLCP and sustaining contraction [12]. Serotonin acts in a similar manner through the 5-HT2B receptor, which couples with Gq and G12/13 to induce vasoconstriction [13].

Figure 2: Platelet roles in hemostasis during wound healing. Upon vascular injury, exposed collagen and von Willebrand factor (vWF) bind platelet receptors to trigger activation and adhesion. Activated platelets release serotonin and generate thromboxane A2 (TxA2), which stimulates vascular smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts to induce vasoconstriction. Platelet shape change and aggregation form the primary hemostatic plug. Platelets also accelerate the coagulation cascade, and the fibrin stabilizes the thrombus to form the secondary hemostatic plug. Abbreviation: vWF, von Willebrand factor; GPVI, glycoprotein VI; GPIb-IX-V, glycoprotein Ib–IX–V complex; TF, tissue factor; PLCγ, phospholipase C γ; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; PKC, protein kinase C; TxA2, thromboxane A2; MLCP, myosin light chain phosphatase; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; FVII, factor VII; FXII, factor XII; FX, factor X; FV, factor V.2.2 Immunologic effect

Following vasoconstriction, primary hemostasis proceeds with platelet adhesion and aggregation. Platelet GPVI and GPIb-IX-V receptors bind to collagen and vWF, respectively, anchoring platelets to the injury site. Collagen binding to GPVI leads to phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif on the associated Fcγ receptor (FcRγ) chain by Src family kinases (SFKs) such as Lyn and Fyn. This event facilitates recruitment of Syk kinase and formation of a LAT signaling complex, ultimately activating phospholipase C γ2 (PLCγ2). PLCγ2 increases IP3-mediated calcium release and DAG-mediated PKC activation [14,15]. Meanwhile, vWF binding to GPIb similarly activates SFKs and downstream PI3K/PLCγ2 signaling [16]. These pathways stimulate granule secretion, cytoskeletal rearrangement (shape change), integrin activation, and fibrinogen binding, resulting in the formation of a platelet plug [17–19].

The temporary plug becomes stabilized during secondary hemostasis, during which the coagulation cascade produces a fibrin mesh that reinforces the platelet aggregates. The cascade comprises extrinsic, intrinsic, and common pathways. In the extrinsic pathway, tissue factor (TF) exposed at the injury site forms a complex with factor VII, which activates factor X to initiate coagulation [20]. The intrinsic pathway begins when collagen exposure activates factor XII, which sequentially activates factors XI, IX, and X, amplifying the coagulation response [21]. In the common pathway, activated factor X (Xa) and factor V form a prothrombinase complex, converting prothrombin into thrombin. Thrombin subsequently converts fibrinogen into fibrin, forming a mesh that stabilizes the platelet plug [22]. Thrombin also activates factor XIII, which crosslinks fibrin fibers to further reinforce the clot. In addition, thrombin enhances platelet activation and induces the externalization of phosphatidylserine on the platelet surface, providing a catalytic platform for coagulation factor complexes [23]. Activated platelets release thromboplastin, which mimics TF and accelerates the extrinsic pathway [22]. Fibrin binds to platelet integrins, strengthening thrombus stability. α-Granules from activated platelets release fibrinogen, factor V, and vWF, directly supporting clot formation [24]. Through these events, hemorrhage ceases, and the vascular injury is securely sealed. Beyond mechanical stabilization, the fibrin clot functions as a provisional matrix that protects the wound from pathogens, minimizes injury size, and facilitates healing. This matrix provides a scaffold for the migration, proliferation, and differentiation of fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. It also facilitates oxygen and nutrient delivery, establishing the foundation for tissue regeneration and repair [25,26].

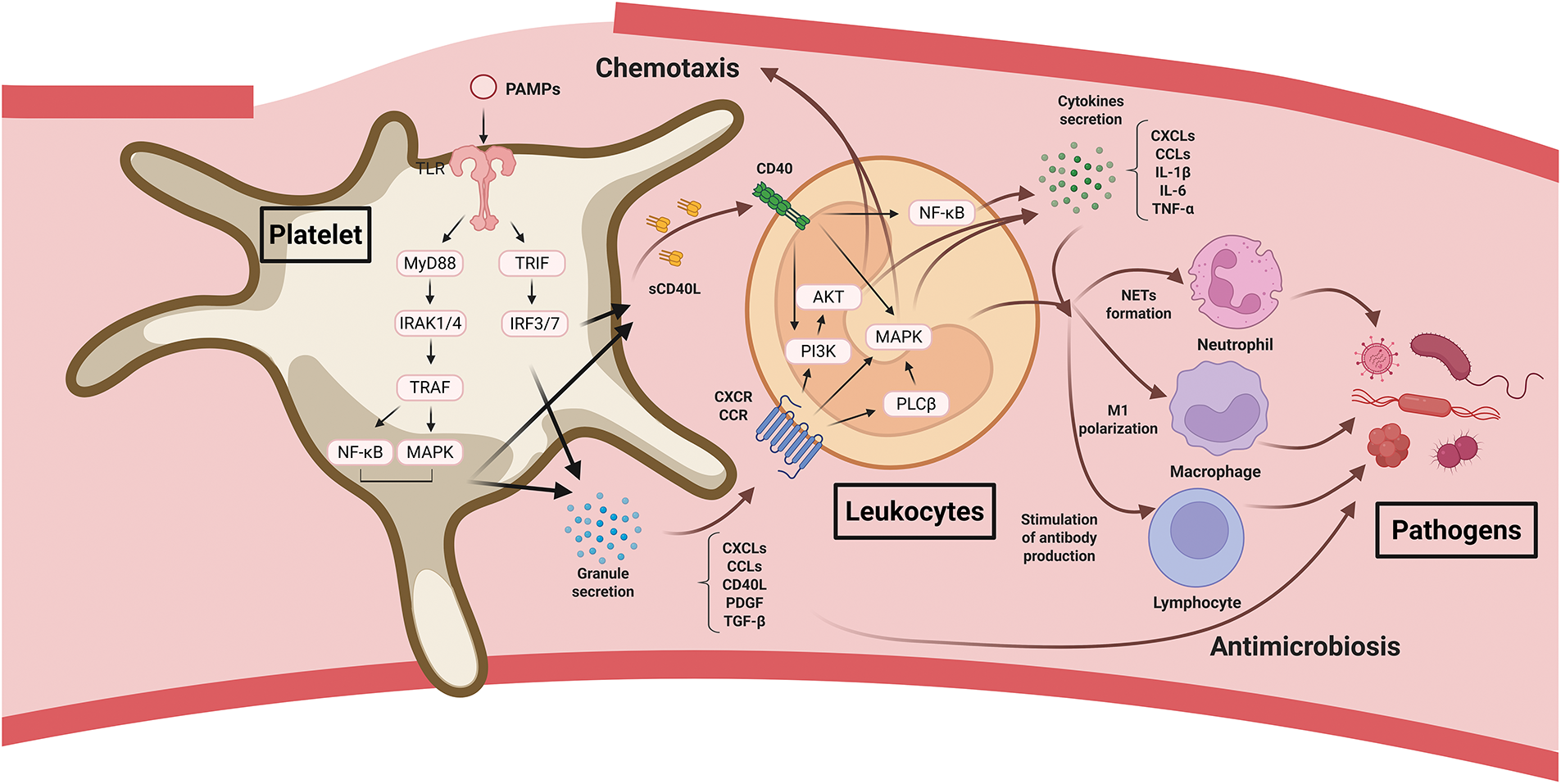

While the hemostatic function of platelets is important during the early stages of wound healing, their immunological mechanisms also serve as key modulators of the healing process (Fig. 3). Numerous studies have shown that platelets directly interact with a wide range of microbes and pathogens. In this context, platelets function as the “first responders” in host defense [27,28]. To fulfill this immunological role, platelets use diverse receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), FcRs, and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Platelets express several TLRs, such as TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR7, and TLR9, which belong to a conserved family of pattern recognition receptors that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns [29,30]. Upon ligand binding, TLRs recruit the adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), which activates IL-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs), particularly IRAK1 and IRAK4. These kinases interact with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), leading to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and promoting the release of platelet granule contents [31]. Platelet α-granules store various proinflammatory mediators, including C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CXCL4), C-C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), CD40L, PDGF, and TGF-β, which recruit immune cells and further activate platelets [32]. TLR1/2 activation on platelets also stimulates the PI3K/Akt pathway, enhancing integrin activation and P-selectin expression, which facilitates platelet–leukocyte interactions [31]. By contrast, TLR3 and TLR4 signaling through a MyD88-independent signaling pathway via the adaptor molecule TRIF (TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β), which activates interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IRF7 and promotes the granule secretion [33–35]. Upon activation, platelets also release platelet-derived microparticles. The microparticles contain antimicrobial proteins and peptides such as thrombocidins, CXCL4, platelet basic protein, CCL5, β-defensins, and fibrinopeptides [36,37]. These molecules directly bind to bacterial membranes, increasing membrane permeability, disrupting cellular integrity, and inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis.

Figure 3: Platelet roles in inflammation and immune responses during wound healing. Platelets are activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and exert direct antimicrobial activity. They then promote leukocyte recruitment and activation, facilitating pathogen clearance. Abbreviations: PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88; TRIF, TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β; IRAK, interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; TRAF, tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated factor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; sCD40L, soluble CD40 ligand; CXCL, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; PLCβ, phospholipase C beta; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; NET, neutrophil extracellular trap

Activated platelets release chemokines that recruit leukocytes to wound sites. CXCLs (CXCL1, CXCL4, CXCL5, CXCL7, CXCL8, CXCL12) and CCLs (CCL3, CCL5) within α-granules actively recruit neutrophils and monocytes. Although dense granule components such as ADP and serotonin do not directly recruit immune cells, they enhance chemokine receptor expression and leukocyte activation [32,38]. These chemokines bind to GPCRs (CXCRs and CCRs), activating the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways through Gαi signaling, and initiating PLCβ activation through Gβγ signaling, which promotes chemotaxis and leukocyte migration. Platelets also express CD40L (a TNF superfamily ligand) on their surface or release it in a soluble form (sCD40L). Binding of sCD40L to CD40 on leukocytes recruits TRAF proteins to the CD40 cytoplasmic domain, leading to the activation of NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways and inducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL8, and CCL2 [32,39]. P-selectin, which is upregulated on activated platelets, functions synergistically with CD40L to enhance leukocyte adhesion and recruitment [40]. sCD40L also binds to CD40 on endothelial cells, promoting leukocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration [41]. Recruited neutrophils form neutrophil extracellular traps, which immobilize and kill pathogens. In addition, platelet-mediated inflammation promotes macrophage M1 polarization, enhances antigen presentation by dendritic cells, and stimulates antibody production by B cells [42]. Through these mechanisms, platelets and the inflammatory cells they recruit contribute to pathogen clearance and facilitate the transition of wounds from the inflammatory to the proliferative phase.

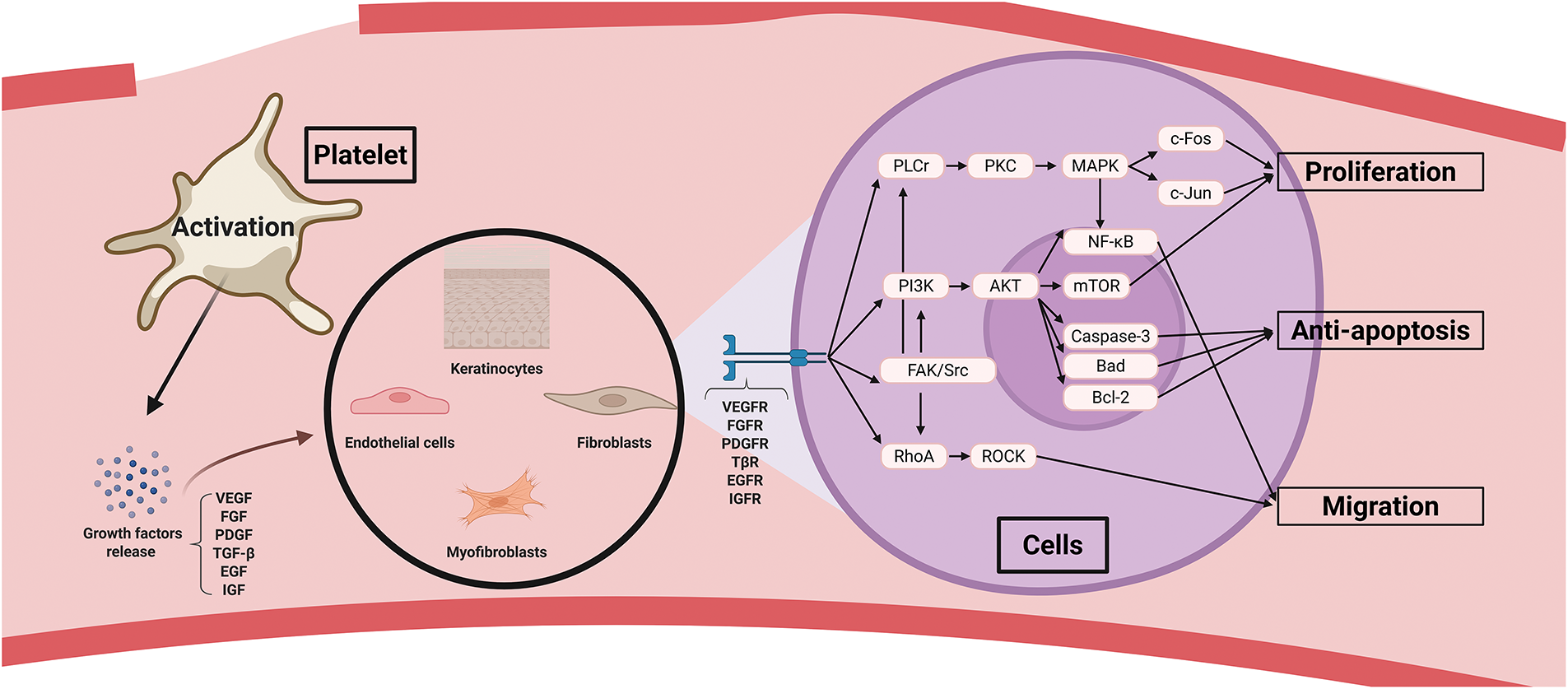

During wound healing, the proliferative phase begins once the initial inflammatory response subsides, marking the onset of active tissue regeneration. This phase is characterized by angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, granulation tissue formation, epithelialization, and wound contraction. Endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes are the major cell types involved. Platelets significantly contribute by releasing growth factors and cytokines that stimulate cell proliferation, thereby accelerating tissue regeneration (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Platelet roles in cell proliferation during wound healing. Platelet growth factors activate multiple signaling pathways in endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts, thereby promoting proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and migration. Abbreviations: VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; TβR, transforming growth factor-β receptor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IGFR, insulin-like growth factor receptor; PLCγ, phospholipase C gamma; PKC, protein kinase C; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase

Angiogenesis, driven by endothelial cell proliferation, supplies oxygen and nutrients to the wound site, replaces damaged vessels from the inflammatory phase, and delivers necessary factors for repair. Among platelet-derived factors, VEGF plays the most significant role in endothelial proliferation and neovascularization. VEGF release is further promoted under hypoxic conditions through HIF-1α and is abundantly secreted from platelet α-granules [43]. The binding of VEGF to VEGFR-2 endothelial cells activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which promotes cell cycle progression via mTOR and upregulates cyclin D1 expression, facilitating endothelial proliferation. In addition, this signaling inhibits apoptosis by enhancing Bcl-2 expression and suppressing pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bad and caspase-3 [44–47]. Activation of the PLCγ-PKC pathway increases intracellular calcium levels, promoting actin polymerization and endothelial migration. This activation also disrupts VE-cadherin and increases vascular permeability, facilitating the influx of plasma proteins and cells, thereby creating a pro-healing environment [48]. PKC activation stimulates the MAPK/ERK cascade through Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling, which induces proliferation-related genes, such as c-Myc and cyclin D1, by activating transcription factors c-Fos and c-Jun [49–51]. Both the PI3K/Akt and PLCγ/PKC/MAPK pathways also activate NF-κB, enhancing the expression of E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) [52]. E-selectin interacts with PSGL-1 on endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), mediating rolling, whereas ICAM-1 binds to β2 integrin on EPCs, facilitating firm adhesion and recruitment of EPCs to the injury site for angiogenesis [53]. Src activation promotes cytoskeletal rearrangement and enhances cell motility, while focal adhesion kinase (FAK) facilitates endothelial migration via integrin interactions [54,55]. VEGF regulates stalk cell differentiation via Dll4/Notch1 signaling and supports vascular lumen formation through interactions with αvβ3 integrin [56,57]. VEGF also activates eNOS to produce nitric oxide, promoting endothelial survival and vasodilation, and interacts with CXCR4 to recruit EPCs and initiate new vessel formation [58,59]. FGF binds to FGFR-1/2 (particularly FGFR-1), and PDGF, particularly PDGF-BB, binds to PDGFR-α/β, strongly inducing the PLCγ/PKC/MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and Src pathways to stimulate endothelial proliferation [60,61]. PDGF-BB also promotes pericyte and smooth muscle cell proliferation via PDGFR-β, enhancing vascular stabilization and maturation through cyclin D1 expression and cell survival via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [62]. The JAK/STAT pathway supports cell differentiation and maturation, whereas FAK/Src signaling promotes pericyte and smooth muscle cell migration [63,64]. TGF-β influences endothelial cells via both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent mechanisms. The Smad-independent pathway, triggered by TβR-I/II, activates PLCγ/PKC/MAPK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, promoting endothelial proliferation [65]. RhoA-ROCK activation enhances junctional protein stability, such as VE-cadherin, reducing permeability and promoting mature vascular structure formation [66]. In the Smad-dependent pathway, low TGF-β levels during the early phase recruit ALK1, leading to Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation and Id1-mediated proliferation [67]. At later stages, higher TGF-β levels activate ALK5, inducing Smad2/3 phosphorylation, and through PAI-1, p21, and p27, suppressing proliferation while promoting vessel stabilization [65,68,69]. SDF-1 binding to CXCR4/CXCR7 also activates PLCγ/PKC/MAPK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways, enhancing endothelial proliferation [70]. Moreover, PKCζ increases HO-1 expression, leading to CO production that activates the CO/PKG/VASP pathway, thereby promoting endothelial actin polymerization and tube formation [71].

Fibroblast proliferation is critical for granulation tissue formation, extracellular matrix (ECM) production, and structural support at wound sites. PDGF plays the most prominent role in early fibroblast proliferation. Platelets contain PDGF-BB, -AB, and some PDGF-AA, which activate PDGFR-α/β on fibroblasts, inducing PI3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated cyclin E expression and promoting cell survival via Bcl-2 upregulation and Bad suppression. ECM synthesis is enhanced by SREBP activation [72–75]. PLCr/PKC/MAPK signaling increases c-Fos and c-Jun expression to promote transcription and proliferation [76,77]. These pathways also upregulate tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP1) and TIMP2, which inhibit MMP activity and maintain ECM stability [78,79]. Fibroblast motility is enhanced through RhoA/ROCK-mediated actin-myosin interaction and LIMK1/2 phosphorylation, which inactivates cofilin and promotes lamellipodia formation [80–83]. FAK and Src phosphorylation induce MMP-2/9 expression, facilitate fibroblast invasion, and enhance ECM adhesion through phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins such as paxillin, vinculin, and talin [84–88]. FGF binds to FGFR1/2, and SDF-1 binds to CXCR4/CXCR7. TGF-β activates fibroblasts via PI3K/Akt/mTOR, PLCγ/PKC/MAPK, RhoA/ROCK, and FAK/Src signaling [65,89].

Keratinocyte proliferation restores the epidermal barrier and prevents infection. EGF is the primary platelet-derived factor responsible for keratinocyte proliferation. Binding of EGF to EGFR activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which inhibits apoptosis by suppressing Bad and caspase-9 phosphorylation and upregulating Bcl-2/Bcl-xL. This pathway also promotes proliferation through cyclin D/E stabilization [90]. Activation of PLCγ/PKC and MAPK via Ras enhances keratinocyte proliferation, whereas RhoA/ROCK and FAK/Src signaling promote migration [90,91]. PKCα/δ regulates keratinization by inducing keratin and involucrin expression [55]. Additional growth factors such as PDGF, TGF-β, FGF-2, and IGF-1 contribute to keratinocyte proliferation and migration through similar mechanisms [92]. Altogether, platelet-mediated proliferation of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes mutually reinforces the function of each cell type, accelerating re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and ultimately scar formation, which restores the structural and physiological integrity of wounded tissue.

3 Characteristics and Application of Platelet Derivatives

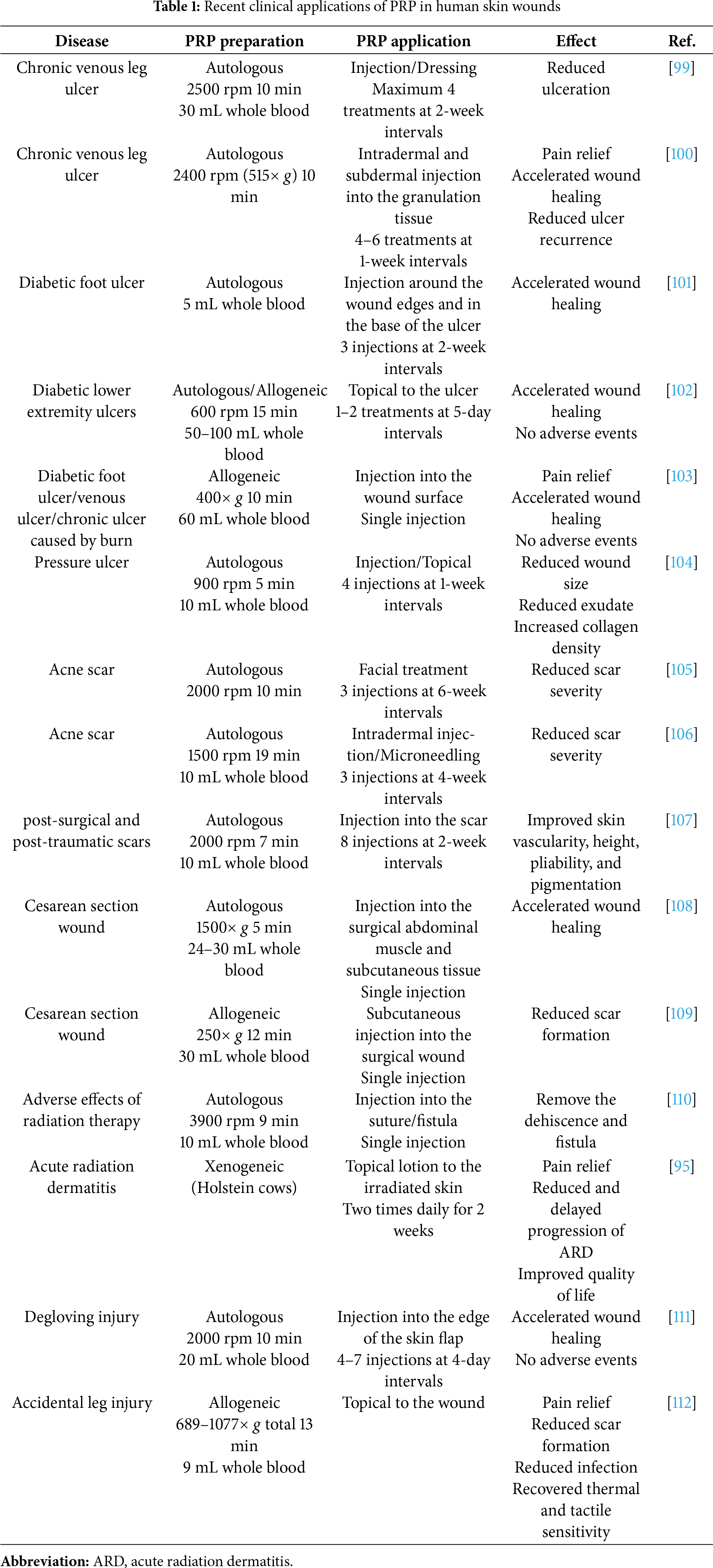

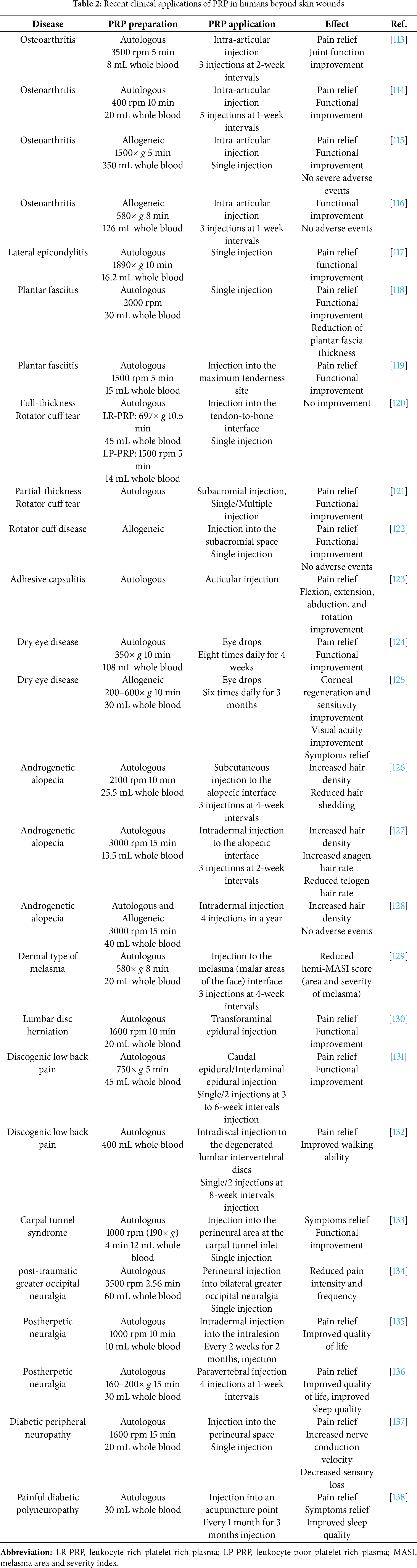

PRP refers to plasma containing a high concentration of platelets extracted from blood, typically 2–5 times higher than that of whole blood. The most common preparation method involves centrifugation, in which the plasma layer is selectively isolated and concentrated. In many applications, platelets are activated approximately one hour before use by adding calcium chloride or thrombin, promoting the release of growth factors and cytokines essential for wound healing. Current clinical uses of PRP extend beyond acute wounds to include chronic wounds, surgical wounds, radiation-induced injuries, skin grafts, burns, dental implants, aesthetic dermatology, and hair loss treatments [68,93–95]. PRP is also applied in musculoskeletal tissues (muscles, tendons, joints, bones, and cartilage), the eye (cornea, conjunctiva, retina), and the nervous system for the treatment and regeneration of inflammatory, degenerative, traumatic, and ruptured lesions, highlighting its wide-range role in regenerative medicine [96–98]. Recent applications of PRP in skin wounds and various regenerative medicines are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

PRP can be classified into leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP) and leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP) based on leukocyte content. LR-PRP can be obtained by low-speed centrifugation or by actively collecting the buffy coat layer, which contains abundant leukocytes. LR-PRP generally has a higher leukocyte content than whole blood, and its platelet recovery rate is typically higher than that of LP-PRP, thus containing higher concentrations of growth factors [139]. Monocytes in LR-PRP secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, IL-4, and TGF-β. These cytokines suppress inflammation; promote M2 macrophage polarization, thereby facilitating tissue repair; and release growth factors such as VEGF to promote angiogenesis [140]. Moreover, the phagocytic activity of monocytes removes dead cells, pathogens, and tissue debris from the wound site, resolving the inflammatory environment and preparing for the proliferative phase of wound healing [141]. Lymphocytes also contribute by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-4, IL-13, and TGF-β), promoting M2 macrophage polarization, and supporting tissue regeneration [142,143]. However, excessive neutrophils in LR-PRP secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, and recruit additional neutrophils, further amplifying inflammation [144]. They generate large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which help eliminate pathogens but may also cause oxidative damage to healthy tissues. In addition, excessive secretion of MMP-8, MMP-9, and elastase can degrade the ECM, leading to structural tissue damage [145]. Because neutrophils in LR-PRP often appear earlier and act more aggressively during the initial wound healing phase, the risk of excessive inflammation and oxidative stress remains significant [146]. When using LR-PRP, strategies to suppress the rapid surge of inflammatory cytokines should therefore be considered. Potential approaches include structural modifications that enable sustained release (e.g., gelation into platelet gels or PRF, or application with scaffolds) or increasing the monocyte/lymphocyte ratio to reduce inflammation-related side effects [147].

Although many formulations are available for various purposes in regenerative medicine, PRP offers several distinct advantages compared with other options. Because PRP is derived from autologous material, it carries no risk of immune reactions such as allergy or inflammation-induced tissue damage. Even in allogeneic or xenogeneic applications, PRP exhibits low immunogenicity, which minimizes the risk of toxicity or immune responses commonly associated with synthetic materials [148,149]. Allogeneic and even xenogeneic PRP is prepared from stringently screened donors, resulting in a lower risk of pathogen transmission than autologous PRP [150,151]. Moreover, platelets, unlike leukocytes, express HLA class I but essentially lack class II, and when PRP is formulated as leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP), antigen presentation is limited [152]. In addition, PRP is most often administered locally by injection or topical application, and once activated, its constituents diffuse gradually within the tissue [153]. As a result, there is minimal spillover into the systemic circulation and few opportunities for immune activation. In patients with chronic wounds or diabetic foot ulcers treated with allogeneic PRP, no abnormalities were observed in vital signs, serum biochemistry, hematology, or urinalysis [154]. Additionally, there was no evidence of anti-platelet antibody formation, no change in bacterial burden, and no wound maceration [154]. Furthermore, the therapeutic mechanism of platelets closely reflects the natural physiological healing process of the body, in which growth factors promote cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and collagen synthesis. Therefore, PRP accelerates tissue repair while causing few adverse effects [155]. Among platelet-based formulations, PRP is one of the easiest to prepare, making it cost-effective. Because production requires only a simple blood draw, the procedure is minimally invasive [156,157].

In contemporary wound care, the clinical focus has shifted from acute, superficial wounds, which heal relatively easily, to chronic deep wounds, which are more difficult and time-consuming to treat. Therefore, PRP is particularly effective for treating chronic, deep wounds. Although PRP can support acute injuries, such as burns or surgical wounds, its effects in these cases remain relatively limited because adequate blood flow generally supports natural healing [158]. By contrast, in intractable wounds, such as chronic ulcers in patients with diabetes, radiation-induced tissue damage, or infections, healing is delayed owing to impaired perfusion, leading to stagnation in the repair process. In such situations, supplementation with growth factors and cytokines can profoundly improve outcomes by overcoming the healing barrier [159]. Because PRP is a liquid formulation, it can be applied topically in combination with dressings. For deep wounds, PRP can be injected directly into the wound margins, making it particularly suitable for chronic wound management [160]. Moreover, PRP retains several advantages even when compared with recently developed advanced wound care therapies. In contrast to stem cell–based approaches, which represent an advanced form of regenerative medicine, PRP carries a much lower risk of tumor formation and is more cost-effective [6,161]. In addition, although many bioengineered skin substitutes provide excellent structural coverage and mechanical protection of wounds, they contain much lesser intrinsic growth factors or cytokines, and thus their actual regenerative efficacy is relatively limited compared with PRP [162]. They are also associated with a risk of immune rejection and face challenges in large-scale production [163].

Although PRP provides many beneficial functions, several derivatives have been developed to enhance its properties. PRF is obtained by immediately centrifuging freshly drawn blood without anticoagulants at a low speed, resulting in a coagulum. Because anticoagulants are not required and preparation requires only simple centrifugation (400–700× g for 8–12 min), PRF is the easiest platelet derivative to produce and can be manufactured most rapidly, making it particularly suitable for clinical use [164,165]. Moreover, PRF forms a sticky, flexible fibrin matrix in gel form, which undergoes natural degradation in vivo and adheres stably to wound or defect sites without external scaffolds, while also filling the site for hemostasis [166,167]. However, PRF contains high concentrations of leukocytes, which can cause inflammatory side effects. In addition, high centrifugation speeds can produce a dense and compact fibrin matrix that results in the rapid burst release of growth factors during the early phase. Shorter centrifugation speeds yield a loose and unstable fibrin matrix that degrades rapidly in vivo, thereby reducing its longevity [168]. To address these limitations, advanced PRF (A-PRF), prepared by centrifugation at a lower speed (200× g) for a longer duration (14 min), forms a loose yet stable fibrin matrix that traps growth factors for longer periods and enables their gradual release, resulting in more favorable long-term regenerative effects [169]. Furthermore, to improve applicability in cases where solid PRF is difficult to use, injectable PRF (i-PRF) is produced by brief centrifugation (3–4 min) before complete fibrin coagulation. This approach allows i-PRF to form a fibrin network immediately after injection, which is particularly effective for deep wounds or anatomically difficult-to-reach areas [170].

Platelet gel is produced by inducing the gelation of PRP using agonists such as CaCl2 and thrombin, forming a gel-like fibrin matrix similar to PRF [171,172]. Compared to PRF, its manufacturing process is more complex, requiring anticoagulants and platelet agonists, and the resulting fibrin matrix is relatively fragile, resulting in shorter persistence [173]. Nevertheless, platelet gel contains fewer leukocytes, which reduces the risk of excessive inflammatory responses and related complications. It also releases growth factors more rapidly and undergoes faster degradation, making it advantageous in situations requiring prompt healing [173].

PL is a liquid preparation obtained by disrupting platelets to release growth factors and cytokines contained within. The process typically begins with PRP preparation to concentrate platelets, followed by disruption through repeated freeze–thaw cycles, ultrasonication at 20 kHz for up to 30 min, or stimulation with agonists such as CaCl2 and thrombin to release intracellular growth factors, followed by centrifugation or filtration to remove cellular debris [174]. Compared with PRP and other platelet derivatives, PL lacks cell membranes, does not trigger immune responses, and represents a cell-free preparation. PL has been shown to be an excellent substitute for fetal bovine serum in promoting the proliferation of various cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and chondrocytes [175–178]. However, because growth factors are completely released, their effects are highly transient, necessitating multiple applications. Furthermore, additional manufacturing steps increase production time [179].

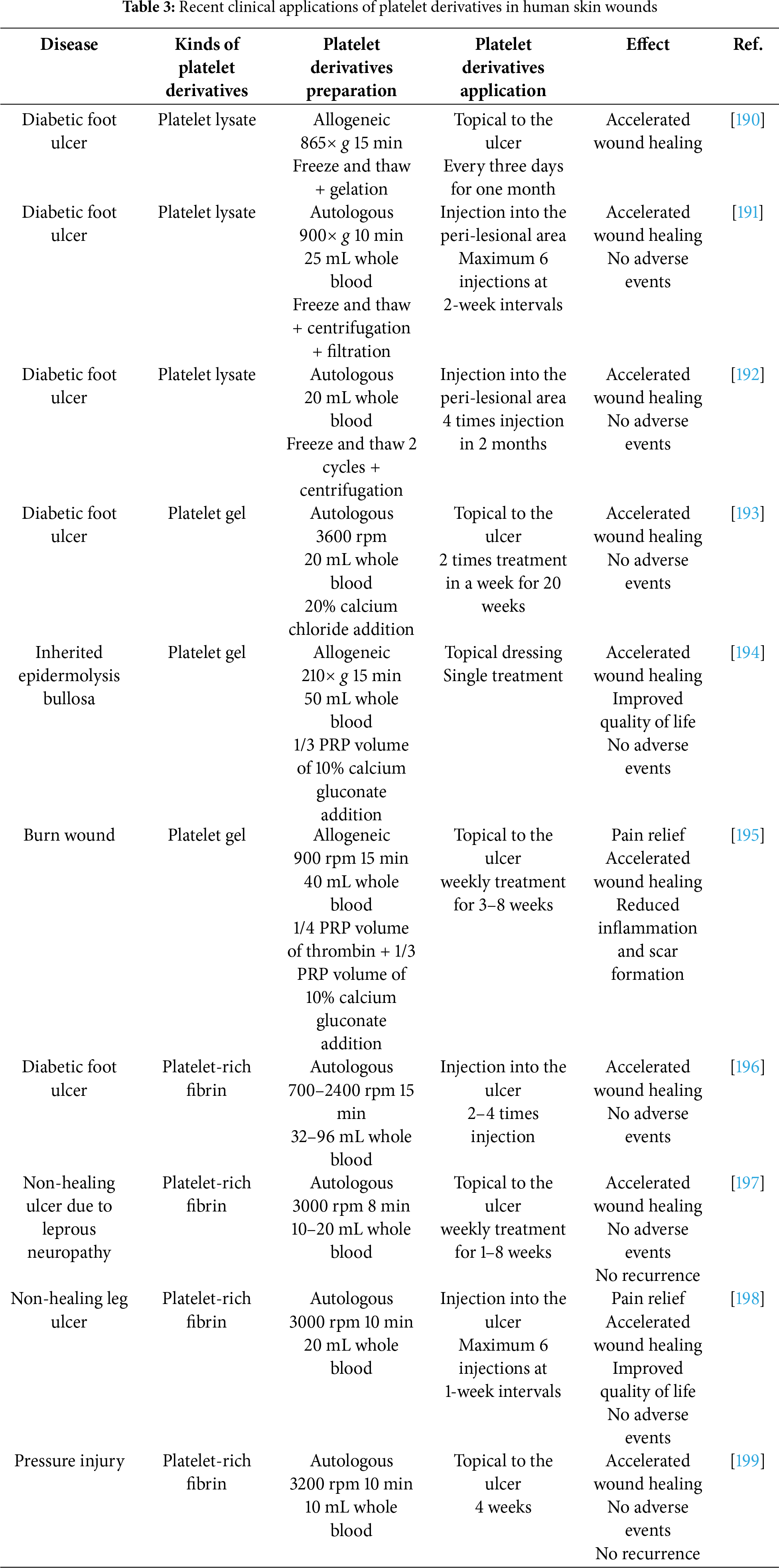

Lyophilized PRP is produced by freezing PRP at –80°C and then removing ice through sublimation under vacuum (freeze-drying). This process yields PRP in powder or sponge form, which can later be rehydrated with saline prior to application. Lyophilization greatly extends storage duration compared with the conventional short shelf life of fresh PRP, which typically lasts only several days under refrigeration. Growth factor activity can be preserved for years, even at room temperature, enabling pre-manufacturing, bulk storage, and convenient clinical application after simple rehydration with saline [180,181]. The use of protectants, such as trehalose and mannitol, both highly biocompatible and stable, helps mitigate protein aggregation and oxidative stress induced by freeze-drying, thereby protecting platelet membranes and proteins while preserving growth factor activity [182–184]. However, lyophilization requires specialized equipment, and the post-rehydration recovery rate of biological activity (reported to be approximately 70%–90%, verification needed) is lower than that of fresh PRP. Moreover, freeze–thaw processes can cause platelet rupture and immediate growth factor release, reducing sustained effects [185,186]. Despite these limitations, lyophilization is particularly suitable for the long-term storage of PLs, given their cell-free nature. PRF and platelet gel can also be stored long-term via lyophilization, although fibrin matrix damage presents some limitations [187,188]. For platelet gel, an effective approach for long-term preservation is to lyophilize PRP, rehydrate it, and then induce gelation with platelet agonists to maintain a stable fibrin matrix structure [189]. Recent applications of platelet derivatives in skin wounds are summarized in Table 3.

4 Challenges in PRP Application and Overcoming Strategies

PRP and platelet derivatives have gained considerable attention as promising agents for wound healing and regenerative medicine, supported by a strong theoretical foundation. Although they provide numerous advantages for tissue repair and regeneration, several limitations persist. In patients with hematological disorders (e.g., sepsis, coagulopathies, malignancies, and anemia), blood collection poses a significant challenge, making the application of autologous PRP difficult. Even when blood can be drawn, concerns remain regarding potential adverse effects from PRP prepared from such whole blood [200–202]. Studies have reported that platelet function in patients with liver cirrhosis or disseminated intravascular coagulation is reduced compared with that in healthy individuals, resulting in lower concentrations of growth factors within PRP [203,204]. For patients in whom blood collection is difficult, allogeneic PRP may serve as an alternative. However, rigorous donor screening is essential to minimize the risk associated with harmful PRP preparation. Furthermore, a consensus statement proposed by the International Research Group of Platelet Injections emphasizes that conditions such as diabetes, cancer, or systemic infections may increase the risk of complications. Careful evaluation of the patient’s condition and cautious use of PRP are therefore necessary to ensure safety [205].

By contrast with conventional pharmaceutical products that maintain consistent quality, platelet derivatives vary in composition depending on patient health status, sex, blood composition, and hematologic parameters. These variations alter leukocyte and platelet ratios as well as growth factor concentrations, complicating the delivery of an optimal therapeutic dose [202,206,207]. Furthermore, well-designed randomized controlled trials using PRP have not been adequately conducted. A perfectly standardized and reproducible centrifugation protocol that maximizes platelet recovery and function while minimizing leukocyte-associated adverse effects has yet to be established, further hindering clinical application. Critical variables, such as the final platelet concentration in PRP, the type and concentration of agonists used for activation, activation duration, and the frequency and dosage of PRP administration, remain undefined. Numerous studies have reported that PRP either provides no benefit in wound healing or regenerative medicine or, in some cases, causes adverse effects [208]. These inconsistencies likely result from the aforementioned variability and uncontrolled factors, hindering the movement of platelet-based therapies toward evidence-based clinical adoption. To address these challenges, pooling blood from multiple donors could reduce variability. To reduce variations in study design and to clearly determine the therapeutic efficacy of PRP across different diseases, well-powered, standardized randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are required to establish robust evidence before widespread clinical adoption.

5 Conclusion and Future Perspective

A wide range of regenerative biomaterials is attracting considerable attention today, each demonstrating outstanding efficacy in specific indications. PRP has likewise been extensively investigated owing to its low immunogenicity, immediate hemostatic action, and direct regenerative stimulation via multiple growth factors. Nevertheless, the demand for more efficient and standardized regenerative materials continues to grow, and diverse lines of research are underway to meet this need. Furthermore, recent advances in scaffold technologies using collagen, fibrin, alginate, silk, or hydrogels, combined with 3D printing, have enabled the development of diverse structural formats (sponges, hydrogels, films, membranes, nanofibers, etc.), thereby facilitating more efficient and effective PRP delivery [209]. Going forward, PRP and other platelet-derived formulations are expected to be increasingly integrated with advanced regenerative modalities, including stem cell therapies, gene therapy, immunomodulatory biomaterials, and bioengineered skin substitutes [162,210]. Such combinations are anticipated to provide new therapeutic options not only for wound healing but also for chronic diseases, refractory tissue injuries, and age-related conditions. To maximize the efficacy and efficiency of platelet-based products, biomaterials-driven engineering strategies, standardized clinical protocols with commercial kits and regulatory frameworks, large-scale randomized trials, and long-term safety evaluations will be essential research priorities, ultimately enabling more concrete and practical implementation in routine clinical practice.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National IT Industry Promotion Agency (NIPA, RQT-25-030567), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1A2C1003638), and the Basic Research Lab Program (2022R1A4A1025557) through the NRF of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Soochong Kim and Sanggu Kim; validation, Soochong Kim; investigation, Sanggu Kim and Seongmo Yang; writing―original draft, Sanggu Kim; writing―review and editing, Soochong Kim; supervision, Soochong Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Larsen JB, Hvas AM, Hojbjerg JA. Platelet function testing: update and future directions. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023;49(6):600–8. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1757898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Scridon A. Platelets and their role in hemostasis and thrombosis-from physiology to pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):12772. doi:10.3390/ijms232112772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yan C, Wu H, Fang X, He J, Zhu F. Platelet, a key regulator of innate and adaptive immunity. Front Med. 2023;10:1074878. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1074878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sánchez-González DJ, Méndez-Bolaina E, Trejo-Bahena NI. Platelet-rich plasma peptides: key for regeneration. Int J Pept. 2012;2012(3):532519. doi:10.1155/2012/532519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bian X, Yin S, Yang S, Jiang X, Wang J, Zhang M, et al. Roles of platelets in tumor invasion and metastasis: a review. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12072. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang Z, Liu P, Xue X, Zhang Z, Wang L, Jiang Y, et al. The role of platelet-rich plasma in biomedicine: a comprehensive overview. iScience. 2025;28(2):111705. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.111705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ieviņa L, Dubņika A. Navigating the combinations of platelet-rich fibrin with biomaterials used in maxillofacial surgery. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1465019. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1465019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Miron RJ, Gruber R, Farshidfar N, Sculean A, Zhang Y. Ten years of injectable platelet-rich fibrin. Periodontol 2000. 2024;94(1):92–113. doi:10.1111/prd.12538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Grzelak A, Hnydka A, Higuchi J, Michalak A, Tarczynska M, Gaweda K, et al. Recent achievements in the development of biomaterials improved with platelet concentrates for soft and hard tissue engineering applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1525. doi:10.3390/ijms25031525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chen H. Role of thromboxane A2 signaling in endothelium-dependent contractions of arteries. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018;134:32–7. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Dong Y, Wang J, Yang C, Bao J, Liu X, Chen H, et al. Phosphorylated CPI-17 and MLC2 as biomarkers of coronary artery spasm-induced sudden cardiac death. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):2941. doi:10.3390/ijms25052941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Eckenstaler R, Ripperger A, Hauke M, Braun H, Ergün S, Schwedhelm E, et al. Thromboxane A2 receptor activation via Gα13-RhoA/C-ROCK-LIMK2-dependent signal transduction inhibits angiogenic sprouting of human endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;201(7347):115069. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Soslau G. Cardiovascular serotonergic system: evolution, receptors, transporter, and function. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol. 2022;337(2):115–27. doi:10.1002/jez.2554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lee RH, Bergmeier W. Platelet immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) and hemITAM signaling and vascular integrity in inflammation and development. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(4):645–54. doi:10.1111/jth.13250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Poulter NS, Pollitt AY, Owen DM, Gardiner EE, Andrews RK, Shimizu H, et al. Clustering of glycoprotein VI (GPVI) dimers upon adhesion to collagen as a mechanism to regulate GPVI signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(3):549–64. doi:10.1111/jth.13613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Y, Ehrlich SM, Zhu C, Du X. Signaling mechanisms of the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex. Platelets. 2022;33(6):823–32. doi:10.1080/09537104.2022.2071852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Aburima A, Walladbegi K, Wake JD, Naseem KM. cGMP signaling inhibits platelet shape change through regulation of the RhoA-Rho Kinase-MLC phosphatase signaling pathway. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(8):1668–78. doi:10.1111/jth.13738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Goggs R, Harper MT, Pope RJ, Savage JS, Williams CM, Mundell SJ, et al. RhoG protein regulates platelet granule secretion and thrombus formation in mice. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(47):34217–29. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.504100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Huang J, Li X, Shi X, Zhu M, Wang J, Huang S, et al. Platelet integrin αIIbβ3: signal transduction, regulation, and its therapeutic targeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0709-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Vojacek JF. Should we replace the terms intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways with tissue factor pathway? Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2017;23(8):922–7. doi:10.1177/1076029616673733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Grover SP, Mackman N. Intrinsic pathway of coagulation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(3):331–8. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.118.312130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Periayah MH, Halim AS, Saad AZM. Mechanism action of platelets and crucial blood coagulation pathways in hemostasis. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2017;11(4):319–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Wolberg AS, Sang Y. Fibrinogen and factor XIII in venous thrombosis and thrombus stability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(8):931–41. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.317164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Golebiewska EM, Poole AW. Platelet secretion: from haemostasis to wound healing and beyond. Blood Rev. 2015;29(3):153–62. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Schultz GS, Chin GA, Moldawer L, Diegelmann RF. Principles of wound healing. In: Mechanisms of vascular disease. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press; 2011. p. 423–50. doi:10.1017/upo9781922064004.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Laurens N, Koolwijk P, De Maat MPM. Fibrin structure and wound healing. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(5):932–9. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01861.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Hickey MJ, Kubes P. Intravascular immunity: the host-pathogen encounter in blood vessels. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(5):364–75. doi:10.1038/nri2532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Mueller KL. Recognizing the first responders. Science. 2010;327(5963):283. doi:10.1126/science.327.5963.283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Herter JM, Rossaint J, Zarbock A. Platelets in inflammation and immunity. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(11):1764–75. doi:10.1111/jth.12730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Cognasse F, Nguyen KA, Damien P, McNicol A, Pozzetto B, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, et al. The inflammatory role of platelets via their TLRs and siglec receptors. Front Immunol. 2015;6:83. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. D’ Atri LP, Schattner M. Platelet toll-like receptors in thromboinflammation. Front Biosci. 2017;22(11):1867–83. doi:10.2741/4576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Koupenova M, Clancy L, Corkrey HA, Freedman JE. Circulating platelets as mediators of immunity, inflammation, and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2018;122(2):337–51. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Panzer B, Kopp CW, Neumayer C, Koppensteiner R, Jozkowicz A, Poledniczek M, et al. Toll-like receptors as pro-thrombotic drivers in viral infections: a narrative review. Cells. 2023;12(14):1865. doi:10.3390/cells12141865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Koupenova M, Livada AC, Morrell CN. Platelet and megakaryocyte roles in innate and adaptive immunity. Circ Res. 2022;130(2):288–308. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Galgano L, Guidetti GF, Torti M, Canobbio I. The controversial role of LPS in platelet activation in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10900. doi:10.3390/ijms231810900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yeaman MR. Platelets in defense against bacterial pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(4):525–44. doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0210-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kraemer BF, Campbell RA, Schwertz H, Cody MJ, Franks Z, Tolley ND, et al. Novel anti-bacterial activities of β-defensin 1 in human platelets: suppression of pathogen growth and signaling of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(11):e1002355. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Raziyeva K, Kim Y, Zharkinbekov Z, Kassymbek K, Jimi S, Saparov A. Immunology of acute and chronic wound healing. Biomolecules. 2021;11(5):700. doi:10.3390/biom11050700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Anitua E, Troya M, Alkhraisat MH. Immunoregulatory role of platelet derivatives in the macrophage-mediated immune response. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1399130. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1399130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Escopy S, Chaikof EL. Targeting the P-selectin/PSGL-1 pathway: discovery of disease-modifying therapeutics for disorders of thromboinflammation. Blood Vessel Thromb Hemost. 2024;1(3):100015. doi:10.1016/j.bvth.2024.100015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Urban D, Thanabalasingam U, Stibenz D, Kaufmann J, Meyborg H, Fleck E, et al. CD40/CD40L interaction induces E-selectin dependent leukocyte adhesion to human endothelial cells and inhibits endothelial cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404(1):448–52. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang H, Kim SJ, Lei Y, Wang S, Wang H, Huang H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):235. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01933-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang J, Yao M, Xia S, Zeng F, Liu Q. Systematic and comprehensive insights into HIF-1 stabilization under normoxic conditions: implications for cellular adaptation and therapeutic strategies in cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2025;30(1):2. doi:10.1186/s11658-024-00682-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang X, Bove AM, Simone G, Ma B. Molecular bases of VEGFR-2-mediated physiological function and pathological role. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:599281. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.599281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liu ZL, Chen HH, Zheng LL, Sun LP, Shi L. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):198. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01460-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. He Y, Sun MM, Zhang GG, Yang J, Chen KS, Xu WW, et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):425. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00828-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Munshi N, Fernandis AZ, Cherla RP, Park IW, Ganju RK. Lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells and its inhibition by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5860–6. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Sjöberg E, Melssen M, Richards M, Ding Y, Chanoca C, Chen D, et al. Endothelial VEGFR2-PLCγ signaling regulates vascular permeability and antitumor immunity through ENOS/Src. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(20):e161366. doi:10.1172/JCI161366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Shah FH, Nam YS, Bang JY, Hwang IS, Kim DH, Ki M, et al. Targeting vascular endothelial growth receptor-2 (VEGFR-2structural biology, functional insights, and therapeutic resistance. Arch Pharm Res. 2025;48(5):404–25. doi:10.1007/s12272-025-01545-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wake H, Hatipoglu OF, Nishinaka T, Watanabe M, Toyomura T, Mori S, et al. Histamine induces vascular endothelial cell proliferation via the histamine H1 receptor-extracellular regulated protein kinase 1/2-cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 axis. Microvasc Res. 2025;163(Supplement 2):104866. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2025.104866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Yao X, Xue Y, Ma Q, Bai Y, Jia P, Zhang Y, et al. 221S-1a inhibits endothelial proliferation in pathological angiogenesis through ERK/c-Myc signaling. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;952:175805. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kim I, Moon SO, Kim SH, Kim HJ, Koh YS, Koh GY. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1and E-selectin through nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(10):7614–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M009705200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Canjuga D, Steinle H, Mayer J, Uhde AK, Klein G, Wendel HP, et al. Homing of mRNA-modified endothelial progenitor cells to inflamed endothelium. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(6):1194. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14061194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Aman J, Margadant C. Integrin-dependent cell-matrix adhesion in endothelial health and disease. Circ Res. 2023;132(3):355–78. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.322332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Barbera S, Raucci L, Lugano R, Tosi GM, Dimberg A, Santucci A, et al. CD93 signaling via rho proteins drives cytoskeletal remodeling in spreading endothelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12417. doi:10.3390/ijms222212417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Blanco R, Gerhardt H. VEGF and Notch in tip and stalk cell selection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(1):a006569. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Cheresh DA, Stupack DG. Regulation of angiogenesis: apoptotic cues from the ECM. Oncogene. 2008;27(48):6285–98. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Pandey AK, Singhi EK, Arroyo JP, Ikizler TA, Gould ER, Brown J, et al. Mechanisms of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) inhibitor-associated hypertension and vascular disease. Hypertension. 2018;71(2):e1–8. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Wragg A, Mellad JA, Beltran LE, Konoplyannikov M, San H, Boozer S, et al. VEGFR1/CXCR4-positive progenitor cells modulate local inflammation and augment tissue perfusion by a SDF-1-dependent mechanism. J Mol Med. 2008;86(11):1221–32. doi:10.1007/s00109-008-0390-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Xie Y, Su N, Yang J, Tan Q, Huang S, Jin M, et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):181. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00222-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Chen PH, Chen X, He X. Platelet-derived growth factors and their receptors: structural and functional perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834(10):2176–86. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.10.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Perez J, Torres RA, Rocic P, Cismowski MJ, Weber DS, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. PYK2 signaling is required for PDGF-dependent vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301(1):C242–51. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00315.2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Song HT, Cui Y, Zhang LL, Cao G, Li L, Li G, et al. Ruxolitinib attenuates intimal hyperplasia via inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway activation induced by PDGF-BB in vascular smooth muscle cells. Microvasc Res. 2020;132(1):104060. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2020.104060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Ishigaki T, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Shimojo N, Matsushima S, Taki W, Yoshida T. Tenascin-C enhances crosstalk signaling of integrin αvβ3/PDGFR-β complex by SRC recruitment promoting PDGF-induced proliferation and migration in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(10):2617–24. doi:10.1002/jcp.22614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Deng Z, Fan T, Xiao C, Tian H, Zheng Y, Li C, et al. TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):61. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01764-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Jerkic M, Letarte M. Increased endothelial cell permeability in endoglin-deficient cells. FASEB J. 2015;29(9):3678–88. doi:10.1096/fj.14-269258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Curado F, Spuul P, Egaña I, Rottiers P, Daubon T, Veillat V, et al. ALK5 and ALK1 play antagonistic roles in transforming growth factor β-induced podosome formation in aortic endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(24):4389–403. doi:10.1128/MCB.01026-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Qiu P, Zhang X, Cao R, Xu H, Jiang Z, Lei J. Assessment of the efficacy of autologous blood preparations in maxillary sinus floor elevation surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1171. doi:10.1186/s12903-024-04938-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Badran M, Gozal D. PAI-1: a major player in the vascular dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5516. doi:10.3390/ijms23105516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Rath D, Chatterjee M, Holtkamp A, Tekath N, Borst O, Vogel S, et al. Evidence of an interaction between TGF-β1 and the SDF-1/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in human platelets. Thromb Res. 2016;144(45–50):79–84. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.06.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Deshane J, Chen S, Caballero S, Grochot-Przeczek A, Was H, Calzi SL, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 promotes angiogenesis via a heme oxygenase 1-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204(3):605–18. doi:10.1084/jem.20061609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(4):1283–316. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Wang J, You J, Gong D, Xu Y, Yang B, Jiang C. PDGF-BB induces conversion, proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis of oral mucosal fibroblasts through PDGFR-β/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2021;30(4):407–15. doi:10.3233/CBM-201681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Wang Z, Ahmad A, Li Y, Kong D, Azmi AS, Banerjee S, et al. Emerging roles of PDGF-D signaling pathway in tumor development and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806(1):122–30. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Zhou Z, Liang S, Zhou Z, Liu J, Zhang J, Meng X, et al. TGF-β1 promotes SCD1 expression via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR-SREBP1 signaling pathway in lung fibroblasts. Respir Res. 2023;24(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12931-023-02313-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang Z, Yang Z, Wang S, Wang X, Mao J. Targeting MAPK-ERK/JNK pathway: a potential intervention mechanism of myocardial fibrosis in heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;173(10159):116413. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Haga M, Iida K, Okada M. Positive and negative feedback regulation of the TGF-β1 explains two equilibrium states in skin aging. iScience. 2024;27(5):109708. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.109708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Sa Y, Li C, Li H, Guo H. TIMP-1 induces α-smooth muscle actin in fibroblasts to promote urethral scar formation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35(6):2233–43. doi:10.1159/000374028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cook H, Davies KJ, Harding KG, Thomas DW. Defective extracellular matrix reorganization by chronic wound fibroblasts is associated with alterations in TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and MMP-2 activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(2):225–33. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00044.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Sarasa-Renedo A, Tunç-Civelek V, Chiquet M. Role of RhoA/ROCK-dependent actin contractility in the induction of tenascin-C by cyclic tensile strain. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(8):1361–70. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Fernández-Simón E, Suárez-Calvet X, Carrasco-Rozas A, Piñol-Jurado P, López-Fernández S, Pons G, et al. RhoA/ROCK2 signalling is enhanced by PDGF-AA in fibro-adipogenic progenitor cells: implications for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(2):1373–84. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Yang S, Huang XY. Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels controls the trailing tail contraction in growth factor-induced fibroblast cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):27130–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501625200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, et al. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature. 1998;393(6687):805–9. doi:10.1038/31729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Graness A, Cicha I, Goppelt-Struebe M. Contribution of Src-FAK signaling to the induction of connective tissue growth factor in renal fibroblasts. Kidney Int. 2006;69(8):1341–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Skhirtladze C, Distler O, Dees C, Akhmetshina A, Busch N, Venalis P, et al. Src kinases in systemic sclerosis: central roles in fibroblast activation and in skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1475–84. doi:10.1002/art.23436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Zhao XK, Cheng Y, Cheng ML, Yu L, Mu M, Li H, et al. Focal adhesion kinase regulates fibroblast migration via integrin beta-1 and plays a central role in fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19276. doi:10.1038/srep19276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Gałdyszyńska M, Zwoliński R, Piera L, Szymański J, Jaszewski R, Drobnik J. Stiff substrates inhibit collagen accumulation via integrin α2β1, FAK and Src kinases in human atrial fibroblast and myofibroblast cultures derived from patients with aortal stenosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;159(2):114289. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Felsenfeld DP, Schwartzberg PL, Venegas A, Tse R, Sheetz MP. Selective regulation of integrin—cytoskeleton interactions by the tyrosine kinase Src. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(4):200–6. doi:10.1038/12021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Urban L, Čoma M, Lacina L, Szabo P, Sabová J, Urban T, et al. Heterogeneous response to TGF-β1/3 isoforms in fibroblasts of different origins: implications for wound healing and tumorigenesis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2023;160(6):541–54. doi:10.1007/s00418-023-02221-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Wee P, Wang Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers. 2017;9(5):52. doi:10.3390/cancers9050052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Frey MR, Golovin A, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated intestinal epithelial cell migration requires Src family kinase-dependent p38 MAPK signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):44513–21. doi:10.1074/jbc.M406253200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Seeger MA, Paller AS. The roles of growth factors in keratinocyte migration. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4(4):213–24. doi:10.1089/wound.2014.0540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Salgado-Pacheco V, Serra-Mas M, Otero-Viñas M. Platelet-rich plasma therapy for chronic cutaneous wounds stratified by etiology: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2024;40(1):31–42. doi:10.1007/s40267-023-01044-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Bahadoram M, Helalinasab A, Namehgoshay-Fard N, Akade E, Moghaddar R. Platelet-rich plasma applications in plastic surgery. World J Plast Surg. 2023;12(1):100–2. doi:10.52547/wjps.12.1.100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Chen ST, Liao GS, Wu CJ, Cheng MS, Shen PC, Su YF, et al. Xenogeneic platelet-rich plasma lotion for preventing acute radiation dermatitis in patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. JPRAS Open. 2024;43:271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2024.11.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774–8. doi:10.1177/0363546506288850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Alio JL, Rodriguez AE, WróbelDudzińska D. Eye platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of ocular surface disorders. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):325–32. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Jin X, Fu J, Lv R, Hao X, Wang S, Sun M, et al. Efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma for acute nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: a prospective cohort study. Front Med. 2024;11:1344107. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1344107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Elbarbary AH, Hassan HA, Elbendak EA. Autologous platelet-rich plasma injection enhances healing of chronic venous leg ulcer: a prospective randomised study. Int Wound J. 2020;17(4):992–1001. doi:10.1111/iwj.13361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Helmy Y, Farouk N, Ali Dahy A, Abu-Elsoud A, Khattab RF, Mohammed SE, et al. Objective assessment of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) potentiality in the treatment of Chronic leg Ulcer: rct on 80 patients with Venous ulcer. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(10):3257–63. doi:10.1111/jocd.14138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Ullah A, Jawaid SI, Qureshi PNAA, Siddiqui T, Nasim K, Kumar K, et al. Effectiveness of injected platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer disease. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28292. doi:10.7759/cureus.28292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. He M, Guo X, Li T, Jiang X, Chen Y, Yuan Y, et al. Comparison of allogeneic platelet-rich plasma with autologous platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic lower extremity ulcers. Cell Transplant. 2020;29(11):963689720931428. doi:10.1177/0963689720931428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Liao X, Liang JX, Li SH, Huang S, Yan JX, Xiao LL, et al. Allogeneic platelet-rich plasma therapy as an effective and safe adjuvant method for chronic wounds. J Surg Res. 2020;246:284–91. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.09.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Putri AC, Soedjana H, Hasibuan L, Sundoro A, Septrina R, Sisca F. The effect of platelet rich plasma on wound healing in pressure ulcer patient grade III and IV. Int Wound J. 2025;22(7):e70458. doi:10.1111/iwj.70458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Priya D, Patil S. A split face comparative interventional study to evaluate the efficacy of fractional carbon dioxide laser against combined use of fractional carbon dioxide laser and platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of acne scars. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14(3):371–4. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_462_22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Manishaa V, Senthil MP. Evaluation of the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections with and without microneedling for managing atrophic facial acne scars: a prospective comparative study. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e60957. doi:10.7759/cureus.60957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Osman MA, Samy NA, Jasim AS. Efficacy of fractional 2940-nm erbium: YAG laser combined with platelet-rich plasma versus its combination with low-level laser therapy for scar revision. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(11):39–44. doi:10.1111/jocd.15410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Barwijuk M, Pankiewicz K, Gałaś A, Nowakowski F, Gumuła P, Jakimiuk AJ, et al. The impact of platelet-rich plasma application during cesarean section on wound healing and postoperative pain: a single-blind placebo-controlled intervention study. Medicina. 2024;60(4):628. doi:10.3390/medicina60040628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Thanachaiviwat A, Suthaporn S, Teng-Umnuay P. Cord blood platelet-rich plasma in cesarean section wound management. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2024;2024(1):4155779. doi:10.1155/ogi/4155779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Bramati C, Biafora M, Galli A, Giordano L. Use of platelet-rich plasma in irradiated patients to treat and prevent complications of head and neck surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(3):e247766. doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-247766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Pundkar A, Shrivastav S, Date S. The effect of locally infiltrated platelet-rich plasma on survival of skin flaps in degloving injuries. J Datta Meghe Inst Med Sci Univ. 2021;16(2):240–3. doi:10.4103/jdmimsu.jdmimsu_439_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Vocca C, Romano F, Marcianò G, Cianconi V, Mirra D, Dominijanni A, et al. Heterologous platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of severe skin damage. Reports. 2023;6(3):34. doi:10.3390/reports6030034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Fossati C, Randelli FMN, Sciancalepore F, Maglione D, Pasqualotto S, Ambrogi F, et al. Efficacy of intra-articular injection of combined platelet-rich-plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) in knee degenerative joint disease: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144(11):5039–51. doi:10.1007/s00402-024-05603-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Partan RU, Putra KM, Hafizzanovian H, Darma S, Reagan M, Muthia P, et al. Clinical outcome of multiple platelet-rich plasma injection and correlation with PDGF-BB in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Pers Med. 2024;14(2):183. doi:10.3390/jpm14020183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Zhu X, Zhao L, Riva N, Yu Z, Jiang M, Zhou F, et al. Allogeneic platelet-rich plasma for knee osteoarthritis in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a randomized clinical trial. iScience. 2024;27(5):109664. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.109664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Sánchez M, Guadilla J, Jorquera C, Marijuán-Pinel D, Mercader-Ruiz J, Beitia M, et al. Intra-articular injections of allogeneic platelet-rich plasma from responder patients for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a pilot and feasibility clinical trial. Cartilage. 2025;36(2):19476035251355522. doi:10.1177/19476035251355522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Kizilkurt T, Aydin AS, Yagci TF, Ersen A, Ercan CC, Salmaslioglu A. Platelet-rich plasma provides superior clinical outcomes without radiologic differences in lateral epicondylitis: randomized controlled trial. Medicina. 2025;61(5):894. doi:10.3390/medicina61050894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Sharma R, Chaudhary NK, Karki M, Sunuwar DR, Singh DR, Pradhan PMS, et al. Effect of platelet-rich plasma versus steroid injection in plantar fasciitis: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):172. doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06277-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Khobragade AS, Barick D, Parmar K, Patil VE, Rokade S, Waghe S. Comparison of the effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injection versus plantar-specific calf stretching exercises in patients with plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e67992. doi:10.7759/cureus.67992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Yao L, Pang L, Zhang C, Yang S, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52(14):3495–504. doi:10.1177/03635465241283964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Desouza C, Shetty V. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J ISAKOS. 2024;9(4):699–708. doi:10.1016/j.jisako.2024.04.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Jo CH, Lee SY, Yoon KS, Oh S, Shin S. Allogeneic platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection for the treatment of rotator cuff disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(24):2129–37. doi:10.2106/JBJS.19.01411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Zhang WB, Ma YL, Lu FL, Guo HR, Song H, Hu YM. The clinical efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma on frozen shoulder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):718. doi:10.1186/s12891-024-07629-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Jongkhajornpong P, Lekhanont K, Rattanasiri S, Numthavaj P, McKay G, Attia J, et al. Efficacy of 100% autologous platelet-rich plasma and 100% autologous serum in dry eye disease: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024;9(1):e001857. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2024-001857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Mancini M, Postorino EI, Gargiulo L, Aragona P. Use of allogeneic platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of autoimmune ocular surface disorders: case series. Front Ophthalmol. 2023;3:1215848. doi:10.3389/fopht.2023.1215848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Nguyen LV, Nguyen TTT. Effectiveness of autologous platelet-rich plasma for androgenetic alopecia: a double-center, non-controlled, randomized clinical study in Vietnam. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2025;18:1645–56. doi:10.2147/CCID.S528663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Legiawati L, Yusharyahya SN, Bernadette I, Novianto E, Priyanto MH, Gliselda KC, et al. Comparing single-spin versus double-spin platelet-rich plasma (PRP) centrifugation methods on thrombocyte count and clinical improvement of androgenetic alopecia: a preliminary, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(12):39–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

128. Pensato R, Al-Amer R, La Padula S. Comparison of the efficacy of homologous and autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for treating androgenic alopecia. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48(1):23–4. doi:10.1007/s00266-023-03472-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Amiri R, Maskooni MK, Farsinejad A, Karvar M, Khalili M, Aflatoonian M. Combination of plasma rich in growth factors with topical 4% hydroquinone compared with topical 4% hydroquinone alone in the treatment of dermal type of Melasma: a single-blinded randomized split-face study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2024;15(4):593–8. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_551_23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Le VT, Dao LTN, Nguyen AM. Transforaminal injection of autologous platelet-rich plasma for lumbar disc herniation: a single-center prospective study in Vietnam. Asian J Surg. 2023;46(1):438–43. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2022.05.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Playfair D, Smith A, Burnham R. An evaluation of the effectiveness of platelet rich plasma epidural injections for low back pain suspected to be of disc origin-a pilot study with one-year follow-up. Interv Pain Med. 2024;3(2):100403. doi:10.1016/j.inpm.2024.100403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Akeda K, Ohishi K, Takegami N, Sudo T, Yamada J, Fujiwara T, et al. Platelet-rich plasma releasate versus corticosteroid for the treatment of discogenic low back pain: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2022;11(2):304. doi:10.3390/jcm11020304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Benny R, Venkataraman S, Chanu AR, Singh U, Kandasamy D, Lingaiah R. A randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of ultrasound-guided, single-dose platelet-rich plasma and corticosteroid injection in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. J Int Soc Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;5(3):90–6. doi:10.4103/jisprm.jisprm-000164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

134. Stone JE, Campbell C, Tabor JB, Bonfield S, Machan M, Shan RLP, et al. Ultrasound guided platelet rich plasma injections for post-traumatic greater occipital neuralgia following concussion: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1400057. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1400057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Abu El-Hamd M, Abd Elaa SG, Abdelwahab A. Possible role of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of patients with postherpetic neuralgia: a prospective, single-arm, open-label clinical study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2024;15(6):986–91. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_86_24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]