Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Harnessing Exercise for Chronic Kidney Disease: Integrating Molecular Pathways, Epigenetics, and Gene-Environment Interactions

1 Department of Physical Education, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 52828, Republic of Korea

2 Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Jinju, 52828, Republic of Korea

3 College of Sport Science, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, 16419, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 52828, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Ji-Seok Kim. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise in Aging and Chronic Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1339-1362. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.064916

Received 27 February 2025; Accepted 07 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects a significant fraction of the global population and is closely associated with elevated cardiovascular risk and poor clinical outcomes. Its pathophysiology entails complex molecular and cellular disturbances, including reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, persistent low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, altered mineral metabolism, genetic predispositions, and uremic toxin accumulation. As current pharmacological treatments provide only partial risk reduction, complementary approaches are imperative. Exercise training, both aerobic and resistance, has emerged as a potent non-pharmacological intervention targeting these underlying molecular pathways. Regular exercise can enhance nitric oxide signaling, improve antioxidant defenses, attenuate inflammation, facilitate endothelial repair via endothelial progenitor cells, and stabilize muscle metabolism. Additionally, accumulating evidence points to a genetic dimension in CKD susceptibility and progression. Variants in genes such as APOL1, PKD1, PKD2, UMOD, and COL4A3–5 shape disease onset and severity, and may modulate response to interventions. Exercise may help buffer these genetic risks by inducing epigenetic changes, improving mitochondrial function, and optimizing crosstalk between muscle, adipose tissue, and the vasculature. This review synthesizes how exercise training can ameliorate key molecular mediators in CKD, emphasizing the interplay with genetic and epigenetic factors. We integrate evidence from clinical and experimental studies, discussing how personalized exercise prescriptions, informed by patients’ genetic backgrounds and nutritional strategies (such as adequate protein intake), could enhance outcomes. Although large-scale trials linking molecular adaptations to long-term endpoints are needed, current knowledge strongly supports incorporating exercise as a cornerstone in CKD management to counteract pervasive molecular derangements and leverage genetic insights for individualized care.Keywords

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains a formidable global health challenge, affecting approximately 10% of adults worldwide and leading to substantial morbidity and premature mortality [1–3]. CKD increases cardiovascular (CV) risk through complex mechanisms that cannot be fully explained by traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. One study reported that chronic inflammation, oxidative stress (OS), and malnutrition, collectively referred to as the “uremic puzzle,” have drawn attention in the CKD setting from a novel biomarker perspective [4]. Another study highlights that vascular calcification and arterial stiffness are major drivers of residual CV risk in patients with CKD and those on dialysis [5], while subsequent clinical guidelines elucidate how CKD-associated mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) exacerbates CV complications through vascular calcification, bone metabolism abnormalities, and hyperparathyroidism [6]. Furthermore, an analysis focusing on the unique presentation of heart failure in CKD/dialysis patients suggests the need for a multifaceted approach beyond traditional risk factor control, including anemia management, correction of CKD-MBD, and mitigation of microinflammation [7]. Given that CKD itself increases the risk of CV disease via fluid and electrolyte imbalances, uremic toxin accumulation, and chronic inflammation, a statement has also pointed out the limitations of managing only conventional risk factors [8]. Therefore, in order to effectively reduce CV risk in CKD patients, it is essential to employ an integrated therapeutic strategy that addresses both traditional and “nontraditional” risk factors.

This persistent risk stems from “nontraditional” and complex molecular factors that extend beyond standard CV risk profiles, encompassing endothelial dysfunction, OS, inflammation, disordered mineral metabolism, and genetic components [4,5]. A deeper understanding of these molecular processes is crucial for developing innovative therapeutic strategies that can bolster current management approaches. CKD pathology is marked by reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability [9], chronic low-grade inflammation [10], increased OS [11], and vascular calcification [12,13]. Additionally, uremic toxins and dysregulated adipokines [14], hepatokines [15], and myokines amplify disease complexity [16], influencing the intricate interplay among the kidneys, vasculature, immune system, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue—networks that collectively drive CKD progression and exacerbate CV risk. Recent findings further highlight a genetic dimension: monogenic conditions (e.g., polycystic kidney disease due to PKD1/PKD2 variants, COL4A3–5 alterations in Alport syndrome) and common risk alleles (e.g., APOL1 G1/G2 variants in individuals of African ancestry) both shape disease onset, progression, and comorbidity profiles [17–20].

Despite these challenges, lifestyle interventions remain central to comprehensive CKD care. Alongside dietary modifications and weight control, exercise training emerges as a non-pharmacological tool capable of simultaneously modulating multiple pathogenic pathways [21,22]. Beyond enhancing exercise capacity and quality of life, regular physical activity improves endothelial function, diminishes OS and inflammation, and fosters metabolic adaptability. Notably, recent interest has focused on how exercise may counteract inherited vulnerabilities, potentially via epigenetic modifications that offset predispositions in NO signaling or antioxidant defenses.

This review aims to elucidate how exercise training specifically targets the molecular underpinnings of CKD. We begin by outlining the molecular and genetic substrates of CKD, then explore how exercise modulates core mechanisms and discuss the genetic and epigenetic determinants that influence exercise responsiveness. Although topics such as detailed endothelial progenitor cell mobilization mechanisms, and the regulation of adipokines and hepatokines are briefly mentioned above, we do not delve into them extensively in the main text. Instead, we have prioritized key pathways directly linked to exercise interventions in CKD, including OS, inflammation, and muscle wasting. We acknowledge, however, that these additional subjects remain closely interwoven with the pathophysiology of CKD and warrant more in-depth investigation in future work. By integrating these molecular and genetic insights, we propose that tailored exercise protocols may help alleviate the inherent complexities of CKD and ultimately advance a personalized exercise medicine approach within nephrology.

This review was conducted as a narrative synthesis of the current literature focusing on the role of exercise in CKD-related molecular mechanisms. We conducted literature searches using PubMed and Scopus from 2000 to 2025, focusing on studies exploring the impact of aerobic or resistance exercise (RE) on inflammation, OS, muscle wasting, and epigenetic modifications in CKD. Given the diversity of study designs, no formal inclusion/exclusion criteria or meta-analytical pooling was applied. Our aim was to integrate mechanistic insights from both preclinical and clinical sources to inform future research directions.

2 Endothelial Dysfunction and Reduced Nitric Oxide Bioavailability

2.1 Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Endothelial cells, which form the inner lining of blood vessels, play a critical role in regulating vascular tone, platelet aggregation, and inflammation [23]. In CKD, various factors such as uric acid, uremic toxins, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA, an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS)), and OS impair the function of eNOS. As a result, the production of NO is reduced, leading to vasoconstriction, platelet activation, and leukocyte adhesion. Persistent NO deficiency fosters a pro-atherogenic environment, contributing to arterial stiffening and plaque formation [24]. Additionally, genetic variations in eNOS, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH, which degrades ADMA; DDAH1, and DDAH2), or L-arginine transporters may influence baseline NO levels and susceptibility to endothelial damage (SLC7) [25]. Furthermore, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential cofactor for eNOS, may become depleted in genetically predisposed individuals (e.g., those with hyperphenylalaninemia), resulting in eNOS uncoupling and the generation of superoxide rather than NO [26]. Understanding these genetic and biochemical factors is crucial, as they highlight the intrinsic disadvantages some patients face, which could influence how effectively exercise or other therapeutic interventions can restore normal NO signaling and improve endothelial function.

2.2 Exercise-Induced Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Enhancement

Animal studies have demonstrated that exercise training mitigates the decline in eNOS expression in the aorta. One such study revealed that eNOS production in the aorta decreases with aging but can be restored through exercise training in aged subjects. These findings suggest that exercise confers beneficial effects on the CV system compromised by aging [27]. Given that CKD prevalence rises sharply around the age of 65 [28], the exercise-induced increase in eNOS appears crucial for both cardiac and renal function. Moreover, sustained and regular exercise may be a key factor in preventing or delaying the progression of CKD associated with aging. Additional animal research has confirmed that exercise training directly upregulates eNOS in the kidney [29,30]. Since the kidney is composed of numerous glomeruli—entwined vessels—maintaining stable blood pressure is essential for renal health. Therefore, the regulation of eNOS expression in blood vessels via exercise helps preserve vascular elasticity and facilitates blood pressure control, thereby supporting kidney function.

It has also been shown in animal models that the eNOS-upregulating effects of exercise can manifest in the acute phase [31], and that chronic running exercise enhances eNOS expression to alleviate the early progression of kidney disease [32]. In that study, chronic running not only upregulated eNOS but also neuronal NO synthase, while implicating NADPH oxidase and α-oxoaldehyde as potential key factors in early diabetes. Taken together, these results indicate that maintaining vascular health and antioxidant capacity through exercise may slow the progression of kidney disease. Ultimately, preserving vascular health and antioxidative function via exercise enhances mitochondrial function in the kidney, which is likely a crucial element in long-term renal health [33,34].

3 Chronic Inflammation as a Central Mediator

3.1 Inflammatory Pathways in CKD

Low-grade, persistent inflammation pervades CKD pathophysiology [10], driven in part by inappropriately activated innate immunity that upregulates pro-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [35], which themselves are crucial in initiating and amplifying inflammatory responses [36]. The promoter region of a gene is where transcription factors bind to regulate expression [37], and variations in these regulatory sequences—along with modifications in innate immune receptors like toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)—have been linked to both susceptibility to inflammatory diseases [36,38,39] and differential responses to therapies in CKD. Physical activity can modulate these pathways, reducing inflammation in healthy individuals and those with chronic inflammatory conditions, including CKD [40], with benefits that extend beyond anti-inflammatory effects to encompass improved physical function, mitigation of comorbidities, and attenuation of upstream factors contributing to CKD progression [41].

3.2 Exercise-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms

Mechanistically, exercise can downregulate TLR4- and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)–dependent signaling cascades [42], decreasing overactive innate immune responses, and induce muscle to release myokines (particularly IL-6 in an acute manner) which can suppress TNF-α and trigger anti-inflammatory IL-10 release [43,44]. Over time, these processes re-balance the cytokine milieu toward an anti-inflammatory profile, while enhancing endothelial function, boosting antioxidant capacity [45], and improving metabolic parameters such as insulin sensitivity and body composition [46]. The collective outcome of these adaptations is a positive feedback loop that lowers chronic inflammation in CKD.

3.3 Clinical Evidence for Exercise in Reducing Inflammation

Empirical support for these benefits is robust: in an randomized controlled trial (RCT), 12 weeks of aerobic exercise (AE) for patients with stages 3–4 CKD significantly reduced TNF-α and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, while improving VO2 max (maximal oxygen consumption) and self-reported function [47]; meta-analyses further demonstrate consistent declines in IL-6 and CRP alongside gains in muscle strength, walking capacity, and quality of life [48]. Notably, both aerobic and resistance training can produce these anti-inflammatory and functional benefits, and long-term exercise adherence correlates with slower CKD progression and reduced CV risk, likely through sustained dampening of pro-inflammatory signals and metabolic improvements [49]. By diminishing chronic inflammation, exercise can also alleviate complications such as anemia, protein-energy wasting, and CV comorbidities; for instance, lower TNF-α and IL-6 levels support better erythropoiesis and reduce muscle catabolism, while improved endothelial function decreases atherosclerotic risk. Hence, structured exercise programs (such as regular aerobic and resistance training) should be integral to CKD management, with potential to slow disease progression, enhance physical function, and improve overall quality of life.

4 Oxidative Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species Overproduction

4.1 Sources and Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in CKD

In CKD, heightened OS arises from imbalances between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (e.g., NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase) and antioxidant defenses (e.g., superoxide dismutase (SOD); catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)) [50,51], with ROS reacting with NO to form peroxynitrite, perpetuating endothelial damage [52,53]. This process is triggered by hyperglycemia [54], hypertension [55], dyslipidemia [56], and proteinuria [57], all of which accelerate kidney injury, and is further exacerbated by the kidney’s high metabolic rate and oxygen demand, rendering renal tissue particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage.

ROS accumulation in the kidney promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis and heightens renal inflammation, driving disease progression [58,59]. While OS is a key pathophysiological mechanism, mounting evidence indicates that physical activity can modulate OS and inflammation, thereby offering a potential therapeutic strategy [60,61]. Although exercise transiently increases ROS production, regular training elicits a long-term upregulation of antioxidant defenses (such as SOD and GPx) that effectively neutralize excessive ROS and reduce cellular damage [62,63]. This antioxidative adaptation is partly mediated by enhanced mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle [64], leading to more efficient ROS handling and improved energy metabolism.

4.2 Exercise-Induced Antioxidant Adaptations

Importantly, observational data link low levels of physical activity with decreased renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [65], suggesting that higher physical activity may confer renal protection. Specific interventions support these findings: For instance, in the diabetic mouse model (db/db mice) that progresses to diabetic kidney disease, the renal tissue exhibited higher malondialdehyde (MDA) levels compared with non-diabetic control mice (db/m) [66]. AE training ameliorated these elevated MDA levels and inhibited Nox4-mediated NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation, thereby mitigating renal injury [66]. Given that excessive ROS generation activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, these findings underscore the antioxidant potential of exercise in attenuating kidney damage. Furthermore, when partial nephrectomy was performed on Wistar rats following an eight-week exercise regimen, the exercised group demonstrated significantly lower levels of urea, creatinine, peroxide production, SOD and CAT activity, thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS), and protein carbonyls compared with the non-exercised nephrectomy control group, while total thiol content was significantly higher [67]. According to the authors, the observed increase in CAT and SOD in rats with CKD reflects an adaptive response of the antioxidant defense system to superoxide overproduction. In other words, they posited that the beneficial effects of exercise on kidney disease stem primarily from reduced oxidant production, rather than a direct alteration of renal function or the antioxidant defense system, thereby suggesting that exercise can preventively improve renal function and OS parameters [67]. In contrast, in patients with CKD receiving hemodialysis, a four-month exercise program (conducted either during dialysis sessions or as a home-based intervention) did not lead to significant changes in MDA, glutathione (GSH), or glutathione disulfide (GSSG) although plasma IL-6 and CRP levels decreased significantly [68]. While these results could be misconstrued to mean that the antioxidant effects of exercise do not translate to human studies, such an interpretation overlooks the fact that these participants had already progressed to advanced kidney disease, where anti-inflammatory benefits may take precedence. Moreover, this finding underscores the importance of regular exercise-based antioxidant interventions prior to the dialysis stage. According to a recent review, AE improves OS markers in patients with CKD compared with standard care or no exercise, yet its effects on GPx and total antioxidant capacity remain to be fully elucidated [69].

4.3 Clinical Perspectives and Stage-Specific Considerations

In summary, exercise exerts renal protective effects through its antioxidant actions. Persistent engagement in physical activity during the early or moderate stages of CKD can slow disease progression and further contribute to overall health improvements in patients with end-stage kidney disease by attenuating inflammation. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that antioxidant mechanisms are not the sole pathway by which exercise confers renal benefits, and more robust evidence is needed to directly link exercise, antioxidant effects, and kidney disease improvement.

5 Mineral Metabolism Disturbances and Klotho Deficiency

5.1 Pathophysiology of CKD-Associated Mineral and Bone Disorder(Fibroblast Growth Factor 23-Klotho Axis)

CKD-MBD is a common comorbidity in patients with CKD [70,71]. CKD–MBD is characterized by hyperphosphatemia, elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) levels, and reduced Klotho expression, collectively disrupting mineral homeostasis and exacerbating vascular complications [72–74]. Notably, Klotho deficiency (often accompanied by excess FGF23) drives vascular calcification and arterial stiffness via multiple mechanisms, including impaired phosphate handling and an increased calcium–phosphate product [75]. Variants that influence phosphate transporters or Klotho transcription may further potentiate arterial calcification, thereby exacerbating CV risk and worsening CKD progression [76–79]. Indeed, Klotho functions as a co-receptor for FGF23, orchestrating phosphate excretion in the kidney and limiting mineral deposition in vascular tissues [76,80]. Loss of Klotho fosters a pro-aging phenotype that impairs bone metabolism and renal function, and predisposes to extensive tissue calcification [80,81].

Such pathophysiological changes reinforce a vicious cycle: increased arterial stiffness elevates systemic blood pressure, compromises renal perfusion, and accelerates nephron injury while further diminishing Klotho expression [82]. Although FGF23 initially supports phosphate excretion [83,84], chronically high levels become maladaptive, fueling left ventricular hypertrophy and perpetuating CKD–MBD [85,86]. Accordingly, either genetic or acquired Klotho insufficiency can magnify disease severity and clinical complications [87].

5.2 Consequences of Klotho Deficiency

Restoring Klotho expression has therefore emerged as a compelling therapeutic goal. Recent preclinical data indicate that exercise training may upregulate Klotho, potentially mitigating the deleterious vascular and renal consequences of CKD–MBD [88,89]. While additional clinical trials are needed, these findings suggest that targeted non-pharmacological interventions—especially structured exercise programs—could elevate Klotho levels and bolster phosphate homeostasis [90]. Parallel research into gene-based therapies aims to enhance Klotho transcription or activity, offering the possibility of reversing vascular calcification and improving renal outcomes. By correcting the underlying mineral imbalance, such approaches may reduce arterial stiffness, slow CKD progression, and alleviate the heightened CV risk that accompanies CKD–MBD.

5.3 Exercise-Based Approaches and Clinical Studies

CKD–MBD is characterized by hyperphosphatemia, elevated FGF23, and decreased Klotho expression, collectively exacerbating vascular calcification and arterial stiffness while sharply declining renal function. According to recent RCTs, preclinical research, and systematic reviews, regular moderate-intensity AE or resistance training significantly increases Klotho expression in both CKD patients and animal models, while partially normalizing mineral metabolism abnormalities such as elevated FGF23, thereby slowing CKD progression [91,92]. For example, in a study involving stage 2 CKD patients who performed blood flow-restricted resistance training for six months, the exercise group exhibited increased Klotho levels and suppressed FGF23, resulting in a reduced rate of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decline [91]. Similarly, in a 22-week pilot study of home-based progressive resistance training, participants also showed elevated Klotho along with improvements in blood pressure and metabolic indicators [92]. Further reports indicate that a 16-week combined aerobic and RE program during hemodialysis in end-stage renal disease patients led to enhanced Klotho levels, decreased FGF23 and serum phosphate, as well as lowered parathyroid hormone (iPTH), collectively yielding positive outcomes for CKD–MBD [93,94]. These findings have been corroborated by meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which have presented evidence that exercise lasting 12 weeks or more confers anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits in CKD patients, supporting the notion of Klotho as an “exerkine”—a factor secreted in response to exercise [90,95]. At the preclinical level, AE has been shown to directly upregulate Klotho in both aging and CKD animal models, mitigating renal fibrosis and OS; moreover, the protective effects of exercise were nullified when Klotho genes or proteins were suppressed, suggesting Klotho as a key mediator of exercise-induced organ protection [88,89]. In conclusion, exercise is considered a relatively safe and highly feasible non-pharmacological approach for CKD–MBD management; by increasing Klotho expression and improving mineral metabolism, it holds substantial potential to slow disease progression and reduce CV risks in this patient population.

6 Uremic Toxins, Epigenetic Dysregulation, and Gene-Environment Interactions

CKD imposes a systemic pathophysiological burden, in large part due to the accumulation of uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, which not only promote OS and inflammation but also exert profound epigenetic influences through aberrant DNA methylation [96–98], altered histone modifications [99], and dysregulated microRNA (miRNA) expression [100]. These toxins preferentially target vascular endothelial cells [101,102], immune cells [103], and skeletal muscle fibers [104], undermining endothelial function, propagating chronic inflammation, and accelerating muscle wasting; furthermore, inherited genetic variations (such as UMOD, MUC1, REN, SEC61A1 variants)—particularly in detoxification pathways or epigenetic regulators—can heighten susceptibility to these abnormalities, culminating in a pathogenic epigenomic landscape that accelerates CKD progression and compromises therapeutic responses [105]. Within this context, tailored exercise interventions have emerged as a promising adjunct, capable of mitigating multiple interrelated factors: by inducing shifts in miRNA profiles [106,107], exercise downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulates anti-inflammatory mediators [108], thereby reducing systemic inflammation; through enhanced mitochondrial function and antioxidant signaling (e.g., nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) activation) [109], it helps counteract OS and improve vascular reactivity; by modulating key anabolic and proteolytic pathways, as well as altering histone acetylation or DNA methylation in genes governing muscle regeneration, regular physical activity can preserve skeletal muscle mass and partially offset the sarcopenic effects of uremic toxins [110]; and, notably, exercise improves insulin sensitivity via increased glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation and reduced ectopic lipid accumulation [111], changes that may be supported by beneficial epigenetic modifications in metabolic pathways [112]. To optimize these effects while minimizing risks—particularly those related to electrolyte disturbances, CV complications, or inadequate dialysis clearance—exercise protocols must be carefully individualized based on renal function, comorbidities, and patient-specific genetic or epigenetic profiles. Emerging research highlights the potential of integrating epigenetic biomarkers, such as promoter methylation signatures linked to inflammatory genes or miRNAs regulating muscle proteostasis, to refine exercise prescriptions further, enabling a precision medicine paradigm that addresses CKD’s complexity by harnessing the synergy between lifestyle interventions and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms.

CKD is typified by the pathological buildup of uremic toxins (e.g., indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate), sustained low-grade inflammation, and persistent OS, all of which accelerate organ damage and contribute to systemic complications, including muscle wasting and CV morbidity. Notably, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that various modes of exercise (e.g., AE, RE, high-intensity interval training (HIIT)) can mitigate these deleterious processes in both pre-dialysis and dialysis-dependent CKD cohorts. By enhancing hemodynamic parameters during dialysis, exercise helps increase the clearance of uremic solutes and potentially modulates the gut microbiota, thereby reducing the production of protein-bound toxins. Additionally, exercise attenuates pro-inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, upregulates antioxidant defense mechanisms via Nrf2, reactivates insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) anabolic signaling, and may favorably alter epigenetic regulators (including microRNAs) that govern muscle proteostasis and renal inflammation [113,114].

From a clinical perspective, intradialytic resistance training and moderate-intensity aerobic regimens have consistently improved physical performance, diminished markers of inflammation, and preserved muscle mass in CKD patients. Abreu et al. [113], for instance, reported that patients who performed intradialytic REs (leg extensions, elastic band exercises) three times per week for 12 weeks exhibited higher expression of Nrf2 and lower NF-κB activity compared to controls, reflecting both antioxidant upregulation and amelioration of inflammatory signaling. Similarly, Moinuddin and Leehey demonstrated [114], in a controlled study, that combining aerobic and resistance protocols in CKD patients not only strengthened muscle function but also reduced systemic inflammation (e.g., lowered TNF-α concentrations) relative to sedentary individuals. Meanwhile, animal models have revealed mechanistic insights: Wang et al. found that treadmill running and muscle overload countered CKD-induced deficits in muscle protein metabolism by stimulating Akt/mTOR phosphorylation and curtailing proteolytic pathways [115], although resistance-like protocols (i.e., weighted muscle overload) elicited a more robust anabolic response. Comparable findings on HIIT in CKD rat models, as described by Tucker et al. [116], suggest that vigorous interval sessions can confer superior improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and anabolic markers.

One emerging concept is that exercise exerts epigenetic influences, notably through modulation of microRNAs (miRNAs). In a seminal study, Wang et al. demonstrated that miR-23a and miR-27a upregulation (induced in part by a resistance-like intervention) alleviated CKD-associated muscle atrophy, largely by repressing catabolic effectors (FoxO1, MuRF1) and facilitating IGF-1-mediated signaling [117]. It is important to investigate how modifiable environmental factors, particularly physical activity, influence the progression of CKD through epigenetic mechanisms. Wing et al. [118] reviewed evidence that environmental inputs such as exercise can affect DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA expression, which are all involved in renal fibrosis, inflammation, and gene regulation in CKD. Physical exercise is already recommended for CKD patients and has shown benefits in improving complications such as MBD, chronic inflammation, and muscle wasting [119]. However, the mechanistic links between exercise and these improvements remain only partly understood [119]. Emerging evidence indicates that epigenetic modifications could be a key mediator, bridging the gap between exercise (an environmental stimulus) and gene expression changes in CKD.

6.1 Epigenetic Dysregulation in CKD and the Influence of Uremic Toxins

CKD is characterized by widespread epigenetic dysregulation. Aberrant DNA methylation, histone modification, and microRNA expression are all implicated in CKD pathogenesis [120]. Such epigenetic changes modulate key pathways (e.g., transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, inflammatory and fibrotic gene networks), thereby promoting renal fibrosis and CKD progression [118]. One notable driver of epigenetic dysregulation in CKD is the accumulation of uremic toxins as kidney function declines. For example, the anti-aging gene Klotho—crucial for renal OS resistance—is suppressed in CKD due to epigenetic silencing: exposure of kidney cells to uremic toxins upregulates DNA methyltransferases, leading to hypermethylation of the Klotho promoter and reduced Klotho expression [118]. This illustrates how toxin-induced epigenetic modifications can turn off renoprotective genes. More broadly, uremic toxins and the associated OS create an epigenomic landscape favoring inflammation and fibrosis (e.g., methylation changes in nephrin promoters that activate NF-κB and injure podocytes) [121–123]. Importantly, epigenetic patterns are not permanent; they are potentially reversible, which makes them attractive therapeutic targets. This is where gene–environment interactions become critical-environmental factors like diet, toxins, and exercise can alter epigenetic marks. Indeed, epigenetics is increasingly seen as the molecular interface between genes and environment in complex diseases like CKD. By addressing environmental contributors (e.g., reducing toxins or increasing physical activity), we may reverse some pathogenic epigenetic changes.

6.2 Exercise as a Modulator of Epigenetic Changes in CKD

Regular physical exercise is a potent environmental stimulus that can induce beneficial molecular changes. Exercise triggers a cascade of cellular signals (such as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation) that enhance metabolic and antioxidant pathways (e.g., upregulating PPARG coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) and mitochondrial biogenesis) [124]. Importantly, exercise also modulates epigenetic mechanisms: it has been shown to induce changes in chromatin structure (through DNA methylation and histone acetylation) and to alter the expression of non-coding RNAs like microRNAs [125,126]. In essence, physical activity can “reprogram” gene expression by rewriting epigenetic marks [127,128]. These epigenetic modifications are one way exercise overcomes the epigenetic dysregulation seen in CKD.

6.2.1 Effects on MicroRNA Regulation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression, and they play significant roles in CKD progression and its complications [119]. In CKD, distinct miRNA profiles have been linked to fibrosis, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction—for instance, circulating miR-21, miR-17, and miR-150 levels correlate with CKD presence and severity [129]. Exercise has emerged as a powerful regulator of microRNAs. Numerous studies in healthy individuals show that endurance and RE can alter circulating miRNA levels associated with angiogenesis, inflammation, and muscle growth [130]. This effect is also observed in CKD patients: acute exercise was found to significantly increase miR-150 in both CKD and healthy subjects, while decreasing pro-inflammatory miR-146a in CKD patients [131]. Although chronic exercise training in that study did not drastically change baseline miRNA levels, it altered the acute response (e.g., enabling an exercise-induced reduction in hypoxia-related miR-210 post-training) [131]. These differential miRNA responses to exercise suggest a physiological adaptation that could benefit CKD patients. Indeed, microRNAs are considered possible mediators of exercise’s therapeutic effects, given their role in fine-tuning genes involved in fibrosis, metabolism, and vascular function. By modulating specific miRNAs, exercise may downregulate pathological pathways and upregulate protective ones. For example, miR-21 is a well-known pro-fibrotic miRNA often elevated in CKD; in vivo experiments show that knocking down miR-21 can prevent renal fibrosis [132]. On the flip side, the miR-29 family is anti-fibrotic, and increasing miR-29b expression in kidney disease models ameliorates fibrosis [132]. Although direct evidence is sparse, it is conceivable that exercise could exert similar effects (naturally suppressing fibrosis-promoting miR-21 and enhancing fibrosis-inhibiting miR-29) thereby slowing CKD progression. Additionally, exercise stimulates the release of exosome-packed “exerkines” (including miRNAs) from muscles, which travel through circulation to remote organs [133]. This muscle–kidney crosstalk via exosomal miRNAs may partly explain how exercise improves not only muscular health but also kidney outcomes. In support, one study in a CKD mouse model (5/6 nephrectomy) found that exercise elevated muscle-derived miR-23a and miR-27a levels, which in turn attenuated muscle wasting and reduced circulating myostatin (a catabolic factor) [117]. Improved muscle mass and reduced inflammation can relieve some CKD-related stress, indirectly benefiting the kidneys. Overall, while exercise-induced miRNA changes in CKD are still being unraveled, current data indicate that miRNAs are a pivotal epigenetic link between exercise and improved CKD pathology.

6.2.2 Effects on DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is another epigenetic mechanism by which exercise may influence CKD outcomes. CKD patients exhibit altered DNA methylation patterns; for example, hypermethylation of anti-inflammatory or renoprotective genes and hypomethylation of promoters that drive inflammation and fibrosis are common [134]. As discussed, uremic toxins can induce DNA hypermethylation of crucial genes like Klotho, exacerbating CKD progression [98]. Physical exercise might counteract these changes through several pathways. First, regular exercise improves renal function and metabolic health, which could lower the burden of uremic toxins and OS that fuel aberrant methylation. Second, exercise has been shown to directly affect DNA methylation in various tissues. In skeletal muscle, acute bouts of exercise can lead to transient DNA hypomethylation at the promoters of metabolic genes, increasing their expression, while long-term training can reprogram the methylation landscape to support endurance adaptation [125,126,135]. Exercise-induced signals (like activated AMPK and increased NAD+ levels) may modulate the activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and demethylating enzymes, thus influencing the methylation status of gene regions. Although specific data in CKD are limited, one can hypothesize that exercise might reduce pathological methylation marks in kidney tissue or blood cells. For instance, if exercise were able to prevent the hypermethylation of the Klotho gene (by dampening DNMT activation via reduced toxin levels), it could help restore Klotho expression and improve renal resilience to oxidative injury. More generally, exercise as a gene–environment interaction can reshape the epigenome: environmental stimuli like physical activity are known to produce tissue-specific epigenetic changes [136]. This may include beneficial DNA methylation changes in immune cells or vascular cells in CKD patients, potentially lowering chronic inflammation. Epigenetic memory is also a consideration—some methylation changes induced by long-term lifestyle modification might persist and contribute to sustained health benefits. While concrete examples in CKD are still forthcoming, ongoing research is beginning to fill this gap by epigenome-wide analyses of exercise interventions. The reversible nature of DNA methylation marks offers a promising avenue whereby consistent exercise could overwrite maladaptive epigenetic marks with a healthier program, slowing CKD progression or even partially rejuvenating the epigenetic profile of cells.

6.2.3 Effects on Histone Modification

Exercise can also influence histone modifications, thereby altering chromatin accessibility and gene expression. Histone acetylation and methylation are key regulators of whether genes are turned “on” or “off.” In general, acetylated histones (via histone acetyltransferases, HATs) lead to a relaxed chromatin structure and active gene transcription, whereas deacetylated or certain methylated histones (mediated by histone deacetylases, HDACs, or histone methyltransferases) result in condensed chromatin and gene repression [137]. CKD has been associated with abnormal histone modification patterns. For example, excessive HDAC activity in the kidney can suppress genes that would normally protect against fibrosis and inflammation, and aberrant histone methylation at promoters can lock in the expression of pro-fibrotic factors [138]. Exercise may help restore a balanced histone code. Research in exercise physiology shows that physical activity increases histone acetylation in skeletal muscle, promoting the expression of genes involved in oxidative metabolism and muscle remodeling [139]. These systemic effects might extend to other tissues as well. During exercise, metabolic by-products (like β-hydroxybutyrate and acetate) can act as HDAC inhibitors or acetyl-CoA donors, thereby enhancing histone acetylation in various cells [140]. Additionally, exercise tends to upregulate sirtuins (SIRT1 and others), which are NAD+-dependent deacetylases that paradoxically improve metabolic health by fine-tuning acetylation levels on both histones and transcription factors. In CKD, low SIRT1 activity (partly due to inflammation or miR-mediated suppression) is linked to renal fibrosis; exercise might boost SIRT1, indirectly altering histone acetylation in favor of anti-fibrotic gene expression [141]. Moreover, exercise intensity and modality can lead to different histone modification outcomes—for instance, endurance training might predominantly enhance acetylation of genes for oxidative capacity [142], while resistance training might impact chromatin regions governing muscle growth hormones [143]. Although direct data on exercise-induced histone changes in kidneys are lacking, it stands to reason that reducing systemic inflammation and improving metabolism (as exercise does) will affect the activity of histone-modifying enzymes in the kidney. Over time, such changes could loosen the epigenetic repression of beneficial genes or tighten the repression of deleterious ones. In summary, exercise has the potential to recalibrate histone modifications in a way that mitigates CKD-related gene expression aberrations, but this hypothesis needs targeted investigation in renal tissues or circulating cells of CKD patients. Beyond general trends in histone modification, exercise elicits precise and well-characterized epigenetic effects that modulate transcriptional activity. For example, acute endurance exercise has been shown to demethylate promoters of key metabolic genes such as PGC-1α, PDK4, and PPARδ in human skeletal muscle, leading to their upregulated expression and improved metabolic adaptation [144]. At the chromatin level, exercise-activated AMPK and CaMKII phosphorylate HDAC5, resulting in its nuclear export and the subsequent relief of transcriptional repression at myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2)-dependent genes, thereby increasing histone H3 acetylation and facilitating metabolic gene expression [145,146]. Additionally, exercise-induced increases in NAD+ activate the deacetylase SIRT1, which modulates histone and non-histone proteins such as PGC-1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism [147,148]. Finally, elevated levels of β-hydroxybutyrate (a ketone body produced during prolonged exercise or fasting) function as endogenous inhibitors of class I HDACs, further enhancing histone acetylation at genes involved in cellular stress resistance and energy regulation [140,149]. Collectively, these mechanisms highlight the multilayered and dynamic epigenetic landscape reshaped by exercise stimuli—effects that may extend beyond muscle to other metabolically active tissues, including the kidney.

7 Muscle Wasting and Sarcopenia in CKD

7.1 Mechanisms of Muscle Wasting

In CKD, sarcopenia arises from complex disruptions in multiple signaling pathways, primarily characterized by suppressed protein synthesis and concurrent enhancement of protein degradation. For instance, the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR axis, which governs anabolic signaling and protein synthesis in skeletal muscle, can be blunted by the pro-inflammatory milieu and insulin resistance inherent to CKD, leading to diminished muscle protein formation [150,151]. By contrast, the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (notably upregulation of Atrogin-1/MAFbx and MuRF1) [152], autophagy–lysosome mechanisms [153], and calpain activity become excessively activated [154], accelerating muscle proteolysis. This proteolytic drive is further reinforced by pro-inflammatory cascades involving NF-κB and p38 MAPK [155], as well as by the TGF-β superfamily ligands myostatin and Activin A, which suppress muscle growth through SMAD2/3 signaling and concurrently promote catabolic gene expression [156]. In the CKD milieu, factors such as uremic toxins (e.g., indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate), chronic low-grade inflammation, and metabolic acidosis can exacerbate myostatin production [157]. Against this backdrop, targeted exercise—particularly resistance or combined aerobic–resistance training—exerts beneficial, direct effects on several levels. Mechanical loading of muscle fibers stimulates the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR pathway, enhancing protein synthesis and favoring anabolic gene expression [158,159]. Several studies suggest that exercise may suppress the myostatin signaling pathway, thereby reducing SMAD2/3 phosphorylation and attenuating the expression of protein degradation–related proteins such as MAFbx (encoded by FBXO32) and MuRF1 (encoded by TRIM63) [160,161]. Additionally, exercise fosters mitochondrial biogenesis and upregulates antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, catalase), mitigating OS and improving muscular energy metabolism [162,163]. These adaptations can diminish intramuscular lipid deposition and ameliorate insulin resistance, thus alleviating some of the metabolic derangements commonly seen in CKD. Consequently, exercise prescriptions in CKD not only address sarcopenia directly but also confer systemic benefits by optimizing metabolic and inflammatory states, potentially slowing disease progression and enhancing quality of life.

7.2 Exercise Strategies for Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia in CKD arises from a complex interplay of factors (including uremic inflammation, metabolic derangements, elevated myostatin expression, and reduced Klotho) that collectively disrupt the balance of muscle protein synthesis and degradation, ultimately compromising muscle mass and strength and thereby exacerbating patients’ functional decline and clinical outcomes [164,165]. Recent RCTs and meta-analyses indicate that both RE and AE beneficially modulate multiple molecular pathways (including IGF-1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR, NF-κB, and Smad2/3) to mitigate sarcopenia and enhance physical performance in CKD populations. Specifically, RE stimulates muscle protein synthesis through mechanical loading and partially overcomes anabolic resistance, thus improving muscle strength and mass, whereas AE exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and suppressing myostatin, thereby refining the overall metabolic milieu [166,167]. Indeed, progressive RE programs exceeding six months have demonstrated significant improvements in grip strength, one-repetition maximum (1RM), and lower-limb strength indicators among CKD patients, with some investigations also reporting hypertrophic effects such as increased muscle cross-sectional area and lean body mass [164]. Meanwhile, AE interventions (e.g., walking, cycling) can enhance CKD-related reductions in cardiopulmonary fitness (by improving six-minute walking distance (6MWT]), gait speed, and stair-climbing duration) while markedly reducing OS markers (e.g., malondialdehyde) and inflammatory mediators (e.g., CRP, IL-6), collectively suggesting a deceleration of sarcopenic progression [165]. Combining RE and AE into a comprehensive program confers synergistic advantages by simultaneously boosting muscular strength and endurance. For instance, in a 16-week study of dialysis patients, concurrent RE and AE training not only improved grip strength and 1RM but also elevated circulating Klotho levels and decreased FGF-23 and sclerostin, while another RCT in nondialysis CKD stages 4–5 similarly documented significant gains in 6MWT performance and quality-of-life metrics [166]. These multifaceted benefits likely arise from exercise’s capacity to ameliorate chronic inflammation, OS, insulin resistance, and hormonal imbalances frequently observed in CKD, thereby safeguarding skeletal muscle and improving overall physical function, ultimately reducing fall risk, enhancing daily activities, and mitigating CV complications [165,167]. Notably, recent animal and cell-based studies reveal that CKD-associated upregulation of myostatin, driven through NF-κB signaling, activates proteolytic pathways (ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome), promoting muscle fiber atrophy. However, regular exercise is proposed to repress myostatin expression and reinforce anti-inflammatory and antioxidant processes, thereby helping to restore muscle metabolic homeostasis [168]. Consequently, a properly tailored and sufficiently intensive exercise regimen is strongly recommended as a cornerstone of both preventive and therapeutic strategies for sarcopenia in CKD, especially when combined with nutritional interventions (e.g., adequate protein intake and vitamin D supplementation) that further support muscle and metabolic health [48].

In this comprehensive overview, we elucidate how multiple molecular perturbations, including endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, epigenetic dysregulation, and excessive uremic toxin accumulation, converge in CKD to drive both disease progression and cardiovascular complications. These molecular derangements are often influenced by specific genetic variants, such as APOL1, PKD1/PKD2, UMOD, and COL4A3–5, which predispose certain patients to faster CKD progression and reduced responsiveness to conventional treatments.

This review acknowledges the limitations of current pharmacological approaches while presenting evidence that aerobic and RE can simultaneously influence several key pathological mechanisms. Exercise has been shown to increase nitric oxide bioavailability, reduce proinflammatory cytokines, enhance antioxidant defenses, and attenuate skeletal muscle wasting. Importantly, physical activity also appears to influence gene expression and epigenetic regulation, potentially mitigating genetic risk by modulating pathways such as myostatin inhibition, IGF-1/AKT/mTOR signaling, and the interactions between muscle, adipose tissue, and the vascular system.

Although this review does not propose a standardized exercise protocol due to substantial variability in patient populations, disease severity, and intervention designs, the mechanistic evidence supports the possibility of tailoring exercise interventions based on individual molecular profiles. For example, patients in early CKD stages may benefit primarily from antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, whereas those undergoing dialysis may require interventions that focus on preserving muscle mass. Future investigations should explore the feasibility of precision exercise prescriptions using genetic, metabolic, and epigenetic markers as stratification tools.

Incorporating exercise into individualized CKD management, when aligned with a patient’s genetic and metabolic background, has the potential to improve clinical outcomes. In addition, while this review focused on the molecular and epigenetic effects of exercise, future studies should also explore the potential synergistic effects of combining exercise with other non-pharmacological interventions such as dietary modifications or nutritional supplementation. These multimodal strategies may interact through shared molecular pathways, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function, and could offer enhanced therapeutic value when applied in an integrated manner. Future research should prioritize the identification and validation of epigenetic biomarkers to enable better patient stratification. In addition, studies are needed to determine the most appropriate exercise modalities and intensities for specific patient subgroups. Long-term clinical trials that link molecular adaptations to measurable clinical endpoints, such as slowed disease progression, reduced cardiovascular events, and improved quality of life, will be essential.

At the same time, it is important to clarify that the aim of this review was not to propose specific exercise regimens. Rather, our intent was to consolidate mechanistic and translational evidence from existing literature. The development of prescriptive exercise protocols requires dedicated clinical studies and safety evaluations that go beyond the scope of a mechanistically focused synthesis. Exercise functions as a systemic modulator with wide-ranging effects on vascular, inflammatory, oxidative, and epigenetic processes, and does not act through a single, target-specific mechanism like a pharmacological agent. For this reason, translating molecular insights directly into fixed exercise recommendations may be premature without supporting outcome-based data.

Nevertheless, this review identifies several molecular targets that appear consistently responsive to exercise. These include improved nitric oxide signaling, inhibition of NF-κB activity, activation of antioxidant enzymes, and modulation of epigenetic regulators such as SIRT1 and miR-29. These pathways may serve as a foundation for future studies aiming to optimize exercise strategies in CKD. They also highlight the importance of continuing to investigate the biological underpinnings of exercise in this population, with the goal of advancing toward a more personalized and mechanistically informed exercise medicine approach in nephrology.

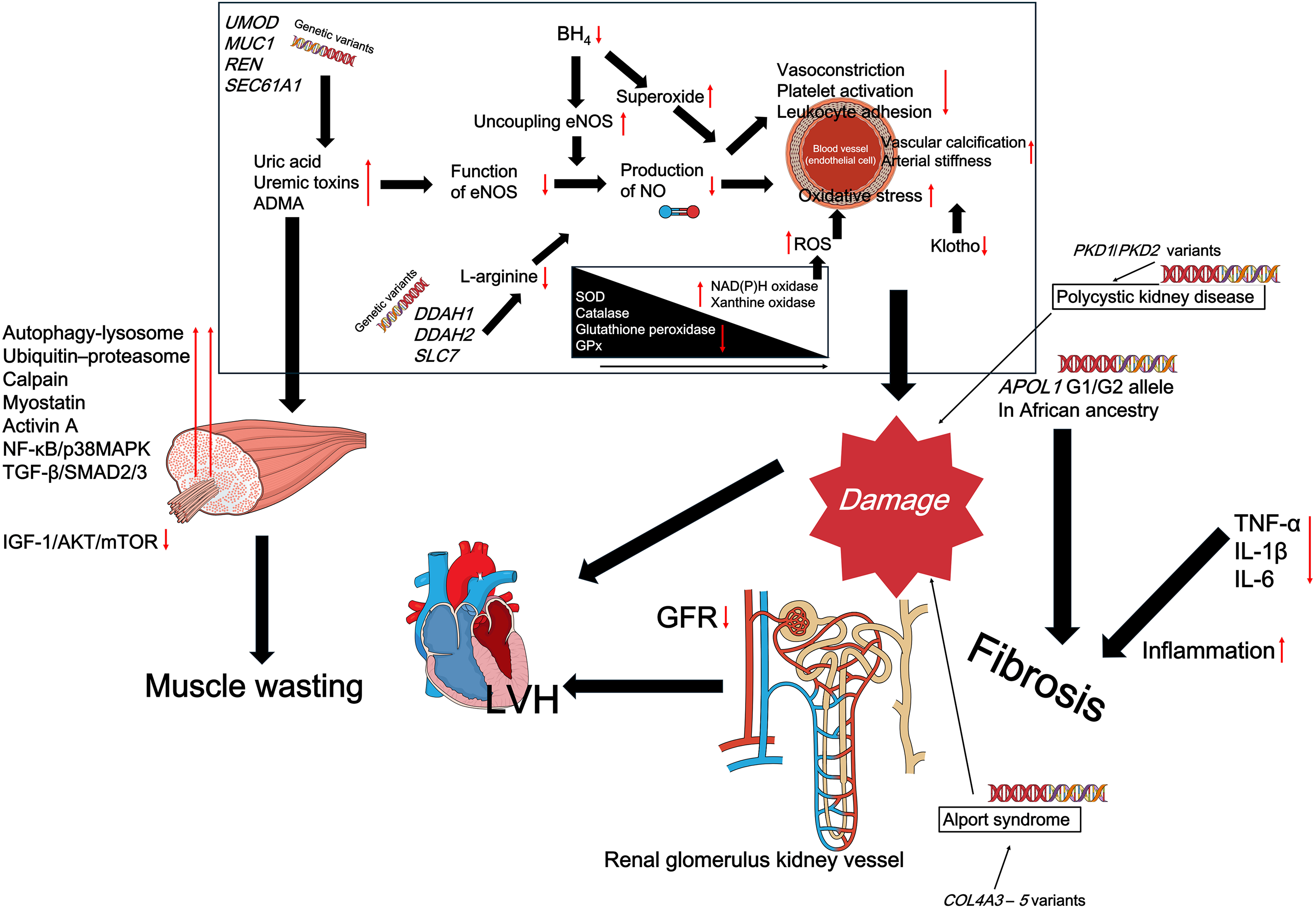

The reviewed evidence positions exercise as a cornerstone intervention capable of correcting or attenuating key pathophysiological mechanisms inherent to CKD. By targeting inflammation, OS, mineral dysregulation, uremic toxin burden, and muscle catabolism, physical activity can impart wide-reaching benefits that extend beyond traditional risk factor control (Fig. 1). Genetic predispositions and epigenetic alterations add a layer of complexity to CKD, but they also offer an avenue for precision exercise medicine — individualized prescriptions informed by patients’ unique molecular and genetic contexts. Embracing this integrative model, wherein exercise is tailored alongside pharmacological, nutritional, and emerging gene-based interventions, could usher in more effective strategies to slow CKD progression and improve survival in this high-risk population.

Figure 1: Overview of key molecular and genetic factors contributing to the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Red arrows indicate pathophysiological changes, such as downregulation of nitric oxide (NO), increased oxidative stress, and activation of proinflammatory and profibrotic pathways. These changes are influenced by genetic variants (e.g., APOL1, PKD1, COL4A3–5) and systemic disturbances, including uremic toxins and reduced antioxidant defenses. While this figure depicts the disease-promoting network, the molecular nodes shown (e.g., NF-κB, ROS, myostatin, SIRT1, IGF-1/AKT/mTOR) are known to be modulated by regular physical exercise, as discussed throughout the manuscript. BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NAD(P)H, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant number: NRF-2022R1A2C1092743). Research grant recipients: JSK.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Kyung-Wan Baek, Ji-Seok Kim; methodology, Kyung-Wan Baek, Jinkyung Cho; validation, Kyung-Wan Baek, Ji-Seok Kim; formal analysis, Kyung-Wan Baek, Jinkyung Cho, Ji Hyun Kim; investigation, Kyung-Wan Baek; resources, Kyung-Wan Baek; data curation, Kyung-Wan Baek; writing—original draft preparation, Kyung-Wan Baek; writing—review and editing, Kyung-Wan Baek; visualization, Kyung-Wan Baek; supervision, Ji-Seok Kim; project administration, Ji-Seok Kim; funding acquisition, Ji-Seok Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AE | Aerobic exercise |

| ADMA | Asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BH4 | Tetrahydrobiopterin |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| CaMK | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKD-MBD | CKD-mineral and bone disorder |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DDAH | Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase |

| DNMT | DNA Methyltransferase |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| FOXO | Forkhead box O |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| FGF23 | Fibroblast growth factor 23 |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HIIT | High-intensity interval training |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| MAFbx | Muscle atrophy F-box (also known as Atrogin-1) |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MEF2 | Myocyte enhancer factor 2 |

| miRNA | Micro RNA |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MuRF1 | Muscle RING-finger protein-1 |

| NAD | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| PGC-1α | PPARG coactivator 1 alpha |

| RE | Resistance exercise |

| RM | Repetition maximum |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin-1 |

| 6MWT | Six-minute walk test |

| SMAD | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

1. Jadoul M, Aoun M, Masimango Imani M. The major global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet Glob Health. 2024;12(3):e342–3. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(24)00050-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM, Tummalapalli SL, Ortiz A, Fogo AB, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20(7):473–85. doi:10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Deng L, Guo S, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Liu Y, Zheng X, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease and its underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):636. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5415099/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Stenvinkel P, Carrero JJ, Axelsson J, Lindholm B, Heimburger O, Massy Z. Emerging biomarkers for evaluating cardiovascular risk in the chronic kidney disease patient: how do new pieces fit into the uremic puzzle? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):505–21. doi:10.2215/cjn.03670807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. London GM. Cardiovascular calcifications in uremic patients: clinical impact on cardiovascular function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(9 Suppl 4):S305–9. doi:10.1097/01.asn.0000081664.65772.eb. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Group KDIGOKC-MUW. KDIGO 2017 Clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7(1):1–59. doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Virani SA, Khosla A, Levin A. Chronic kidney disease, heart failure and anemia. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24 Suppl B(Suppl B):22B–4B. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(08)71026-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension. 2003;42(5):1050–65. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.0000102971.85504.7c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Reddy YS, Kiranmayi VS, Bitla AR, Krishna GS, Rao PV, Sivakumar V. Nitric oxide status in patients with chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol. 2015;25(5):287–91. doi:10.4103/0971-4065.147376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mihai S, Codrici E, Popescu ID, Enciu AM, Albulescu L, Necula LG, et al. Inflammation-related mechanisms in chronic kidney disease prediction, progression, and outcome. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2180373. doi:10.1155/2018/2180373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Montenegro J, Klein M, Bregman R, Prado CM, Barreto Silva MI. Osteosarcopenia in patients with non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(6):1218–27. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2022.04.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Adragao T, Pires A, Lucas C, Birne R, Magalhaes L, Goncalves M, et al. A simple vascular calcification score predicts cardiovascular risk in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(6):1480–8. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ballanti P, Silvestrini G, Pisano S, De Paolis P, Di Giulio S, Mantella D, et al. Medial artery calcification of uremic patients: a histological, histochemical and ultrastructural study. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26(2):191–200. doi:10.14670/HH-26.191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Teta D. Adipokines as uremic toxins. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22(1):81–5. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2011.10.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Mehrotra R. Emerging role for fetuin-A as contributor to morbidity and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2007;72(2):137–40. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Peng H, Wang Q, Lou T, Qin J, Jung S, Shetty V, et al. Myokine mediated muscle-kidney crosstalk suppresses metabolic reprogramming and fibrosis in damaged kidneys. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1493. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01646-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Z, Bai H, Blumenfeld J, Ramnauth AB, Barash I, Prince M, et al. Detection of PKD1 and PKD2 somatic variants in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney cyst epithelial cells by whole-genome sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(12):3114–29. doi:10.1681/asn.2021050690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chen S, Xu G, Zhao Z, Du J, Shen B, Li C. A novel COL4A5 splicing mutation causes alport syndrome in a Chinese family. BMC Med Genomics. 2024;17(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12920-024-01878-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Groen S, Rood IM, Steenbergen E, Willemsen B, Dijkman HB, van Geel M, et al. Kidney disease associated with mono-allelic COL4A3 and COL4A4 variants: a case series of 17 families. Kidney Med. 2023;5(4):100607. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2023.100607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Pollak MR, Friedman DJ. APOL1 and APOL1-associated kidney disease: a common disease, an unusual disease gene—proceedings of the henry shavelle professorship. Glomerular Dis. 2023;3(1):75–87. doi:10.1159/000529227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Clyne N, Anding-Rost K. Exercise training in chronic kidney disease-effects, expectations and adherence. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(Suppl 2):ii3–14. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfab012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao Q, He Y, Wu N, Wang L, Dai J, Wang J, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions to improve physical function in patients with end-stage renal disease: a network meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2023;54(1–2):35–41. doi:10.1159/000530219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Sumpio BE, Riley JT, Dardik A. Cells in focus: endothelial cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34(12):1508–12. doi:10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00075-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Singh R, Devi S, Gollen R. Role of free radical in atherosclerosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia: larger-than-life. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31(2):113–26. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Janaszak-Jasiecka A, Ploska A, Wieronska JM, Dobrucki LW, Kalinowski L. Endothelial dysfunction due to eNOS uncoupling: molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic targets. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023;28(1):21. doi:10.1186/s11658-023-00423-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Werner ER, Blau N, Thony B. Tetrahydrobiopterin: biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem J. 2011;438(3):397–414. doi:10.1042/bj20110293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Tanabe T, Maeda S, Miyauchi T, Iemitsu M, Takanashi M, Irukayama-Tomobe Y, et al. Exercise training improves ageing-induced decrease in eNOS expression of the aorta. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;178(1):3–10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-201x.2003.01100.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Merchant AA, Ling E. An approach to treating older adults with chronic kidney disease. CMAJ. 2023;195(17):E612–8. doi:10.1503/cmaj.221427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ito D, Ito O, Cao P, Mori N, Suda C, Muroya Y, et al. Effects of exercise training on nitric oxide synthase in the kidney of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(2):74–82. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ito D, Ito O, Mori N, Cao P, Suda C, Muroya Y, et al. Exercise training upregulates nitric oxide synthases in the kidney of rats with chronic heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(9):617–25. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cacicedo JM, Gauthier MS, Lebrasseur NK, Jasuja R, Ruderman NB, Ido Y. Acute exercise activates AMPK and eNOS in the mouse aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(4):H1255–65. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01279.2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ito D, Cao P, Kakihana T, Sato E, Suda C, Muroya Y, et al. Chronic running exercise alleviates early progression of nephropathy with upregulation of nitric oxide synthases and suppression of glycation in zucker diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138037. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Bhargava P, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(10):629–46. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2017.107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Davidson SM, Duchen MR. Endothelial mitochondria: contributing to vascular function and disease. Circ Res. 2007;100(8):1128–41. doi:10.1161/01.res.0000261970.18328.1d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Jones SA. Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):3463–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Hirano T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int Immunol. 2021;33(3):127–48. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxaa078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bansal M, Kumar A, Yella VR. Role of DNA sequence based structural features of promoters in transcription initiation and gene expression. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;25(Suppl 1):77–85. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2014.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Emonts M, Veenhoven RH, Wiertsema SP, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Walraven V, de Groot R, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in immunoresponse genes TNFA, IL6, IL10, and TLR4 are associated with recurrent acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):814–23. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Lorenz E, Mira JP, Frees KL, Schwartz DA. Relevance of mutations in the TLR4 receptor in patients with gram-negative septic shock. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(9):1028–32. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.9.1028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Carney EF. Chronic kidney disease. Walking reduces inflammation in predialysis CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(6):300. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Gould DW, Graham-Brown MP, Watson EL, Viana JL, Smith AC. Physiological benefits of exercise in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2014;19(9):519–27. doi:10.1111/nep.12285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Dong W, Luo M, Li Y, Chen X, Li L, Chang Q. MICT ameliorates hypertensive nephropathy by inhibiting TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway and down-regulating NLRC4 inflammasome. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0306137. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0306137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1379–406. doi:10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(9):607–15. doi:10.1038/nri3041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Green DJ, Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Taylor R. Effect of exercise training on endothelium-derived nitric oxide function in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 1):1–25. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R, et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(2):92–103. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Headley S, Germain M, Wood R, Joubert J, Milch C, Evans E, et al. Short-term aerobic exercise and vascular function in CKD stage 3: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(2):222–9. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(10):CD003236. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Robinson-Cohen C, Katz R, Mozaffarian D, Dalrymple LS, de Boer I, Sarnak M, et al. Physical activity and rapid decline in kidney function among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2116–23. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM. The elephant in uremia: oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia. Kidney Int. 2002;62(5):1524–38. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00600.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Vaziri ND. Oxidative stress in uremia: nature, mechanisms, and potential consequences. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24(5):469–73. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.06.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hsieh HJ, Liu CA, Huang B, Tseng AH, Wang DL. Shear-induced endothelial mechanotransduction: the interplay between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) and the pathophysiological implications. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21(1):3. doi:10.1186/1423-0127-21-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Hsiai TK, Hwang J, Barr ML, Correa A, Hamilton R, Alavi M, et al. Hemodynamics influences vascular peroxynitrite formation: implication for low-density lipoprotein apo-B-100 nitration. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(4):519–29. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. DCCTR Group, Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, Crofford O, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977–86. doi:10.1056/nejm199309303291401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Hamrahian SM, Falkner B. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;956:307–25. doi:10.1007/5584_2016_84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Tsimihodimos V, Mitrogianni Z, Elisaf M. Dyslipidemia associated with chronic kidney disease. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2011;5:41–8. doi: 10.2174/1874192401105010041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Agrawal V, Marinescu V, Agarwal M, McCullough PA. Cardiovascular implications of proteinuria: an indicator of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(4):301–11. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Daenen K, Andries A, Mekahli D, Van Schepdael A, Jouret F, Bammens B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(6):975–91. doi:10.1007/s00467-018-4005-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Scholze A, Jankowski J, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Evenepoel P. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:8375186. doi:10.1155/2016/8375186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Battaglia Y, Baciga F, Bulighin F, Amicone M, Mosconi G, Storari A, et al. Physical activity and exercise in chronic kidney disease: consensus statements from the physical exercise working group of the italian society of nephrology. J Nephrol. 2024;37(7):1735–65. doi:10.1007/s40620-024-02049-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Bellos I, Marinaki S, Lagiou P, Boletis IN, Stehouwer CDA, van Greevenbroek MMJ, et al. Association of physical activity with endothelial dysfunction among adults with and without chronic kidney disease: the Maastricht Study. Atherosclerosis. 2023;383(Suppl A):117330. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2023.117330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Craige SM, Mammel RK, Amiri N, Willoughby OS, Drake JC. Interplay of ROS, mitochondrial quality, and exercise in aging: potential role of spatially discrete signaling. Redox Biol. 2024;77(1985):103371. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Ji LL, Leeuwenburgh C, Leichtweis S, Gore M, Fiebig R, Hollander J, et al. Oxidative stress and aging. Role of exercise and its influences on antioxidant systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;854(1):102–17. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09896.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Roshanravan B, Kestenbaum B, Gamboa J, Jubrias SA, Ayers E, Curtin L, et al. CKD and muscle mitochondrial energetics. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(4):658–9. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kelly JT, Su G, Zhang L, Qin X, Marshall S, Gonzalez-Ortiz A, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors for primary prevention of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):239–53. doi:10.1681/ASN.2020030384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhou Z, Ying C, Zhou X, Shi Y, Xu J, Zhu Y, et al. Aerobic exercise training alleviates renal injury in db/db mice through inhibiting Nox4-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Exp Gerontol. 2022;168(A7):111934. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2022.111934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Coelho BL, Rocha LG, Scarabelot KS, Scheffer DL, Ronsani MM, Silveira PC, et al. Physical exercise prevents the exacerbation of oxidative stress parameters in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20(3):169–75. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2009.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Melendez-Oliva E, Sanchez-Vera Gomez-Trelles I, Segura-Orti E, Perez-Dominguez B, Garcia-Maset R, Garcia-Testal A, et al. Effect of an aerobic and strength exercise combined program on oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a single blind randomized controlled trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54(9):2393–405. doi:10.1007/s11255-022-03146-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhao M, Xiao M, Tan Q, Lyu J, Lu F. The effect of aerobic exercise on oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Ren Fail. 2023;45(2):2252093. doi:10.1080/0886022x.2023.2252093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Sprague SM, Martin KJ, Coyne DW. Phosphate balance and CKD-mineral bone disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(8):2049–58. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.05.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Chuang SH, Wong HC, Vathsala A, Lee E, How PP. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in incident peritoneal dialysis patients and its association with short-term outcomes. Singapore Med J. 2016;57(11):603–9. doi:10.11622/smedj.2015195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Fliser D, Kollerits B, Neyer U, Ankerst DP, Lhotta K, Lingenhel A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(9):2600–8. doi:10.1681/asn.2006080936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Mirza MA, Larsson A, Melhus H, Lind L, Larsson TE. Serum intact FGF23 associate with left ventricular mass, hypertrophy and geometry in an elderly population. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(2):546–51. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):584–92. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0706130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Edmonston D, Grabner A, Wolf M. FGF23 and klotho at the intersection of kidney and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(1):11–24. doi:10.1038/s41569-023-00903-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390(6655):45–51. doi:10.1038/36285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quinones H, Griffith C, Kuro-o M, et al. Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(1):124–36. doi:10.1681/asn.2009121311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Ichikawa S, Imel EA, Kreiter ML, Yu X, Mackenzie DS, Sorenson AH, et al. A homozygous missense mutation in human KLOTHO causes severe tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(9):2684–91. doi:10.1172/JCI31330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Nakatani T, Sarraj B, Ohnishi M, Densmore MJ, Taguchi T, Goetz R, et al. In vivo genetic evidence for klotho-dependent, fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23)-mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis. FASEB J. 2009;23(2):433–41. doi:10.1096/fj.08-114397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]