Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Technological Innovations and Multi-Omics Approaches in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Review

1 Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute, Chettinad Academy of Research and Education, Kelambakkam, 603103, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Faculty of Paramedical Sciences, Assam down town University, Guwahati, 781026, Assam, India

3 Department of Pharmacology, JKKN Dental College and Hospital (Affiliated to The Dr. MGR Medical University), Kumarapalayam, 638183, Tamil Nadu, India

* Corresponding Author: Gowtham Kumar Subbaraj. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Genetic Biomarkers of Cancer: Insights into Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1363-1390. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065891

Received 24 March 2025; Accepted 28 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Cancer rates are increasing globally, making it more urgent than ever to enhance research and treatment strategies. This study aims to investigate how innovative technology and integrated multi-omics techniques could help improve cancer diagnosis, knowledge, and therapy. A complete literature search was undertaken using PubMed, Elsevier, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Embase, and NCBI. This review examined the articles published from 2010 to 2025. Relevant articles were found using keywords and selected using inclusion criteria New sequencing methods, like next-generation sequencing and single-cell analysis, have transformed our ability to study tumor complexity and genetic mutations, paving the way for more precise, personalized treatments. At the same time, imaging technologies such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) have made detecting tumors early and tracking treatment progress easier, all while improving patient comfort. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are having a significant impact by helping to analyze large volumes of data more efficiently and enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Meanwhile, Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR/Cas9) gene editing is emerging as a promising tool for directly targeting genes related to cancer, providing new possibilities for treatment. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data, multi-omics approaches provide researchers with a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving cancer, thereby facilitating the discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Despite these advancements, additional challenges persist, such as data integration, elevated costs, standardisation concerns, and the intricacies of translating findings into clinical practice, which might prevent wider implementation. Research needs to concentrate on improving these developments and encouraging multidisciplinary cooperation going forward to maximize their possibilities. Personalized cancer therapies will become more successful with ongoing developments, therefore enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.Keywords

Global population growth and aging are contributing to rising cancer incidence and death rates, which suggests changes in the distribution and prevalence of the main risk factors for cancer [1]. The United States projects 2,001,140 new cancer cases and 611,720 cancer deaths in 2024. While the most prevalent cancers in women were breast, lung, and colorectal cancers, among males, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers were the most often occurring ones [2]. Data from the National Cancer Registry Program indicate a consistent rise in cancer-related fatalities in India, with 770,230 deaths in 2020, 789,202 in 2021, and 808,558 in 2022. With an expected 1,461,427 new cases recorded in 2022, almost one in nine Indians is expected to develop cancer over their lifetime [3]. By 2025, there will be 29.8 million cancer cases, according to the Indian Council for Medical Research, highlighting the urgent need for better screening, prevention, and treatment strategies [4]. Cancer is expected to increase significantly in the coming decades, with 35 million new annual cases by 2050. Low- and middle-income countries are expected to account for 70% of global premature cancer deaths due to population growth, increased risk factors, demographic aging, health system vulnerabilities, and humanitarian crises [5]. Given that prevention is only realistic for a few types of cancer, there is an urgent need for technological advancements in cancer diagnostics. These innovations are essential for the precise determination of tumor location, size, stage, and molecular characteristics, especially as global cancer-related mortality continues to rise [6]. For decades, cancer treatment options were limited to surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy, either as standalone treatments or in combination [7]. Physical exams, laboratory testing, and radiologic or nuclear medicine-based imaging modalities, including CT scans, ultrasonography, MRI, bone scans, and positron emission tomography, define the traditional path of cancer diagnosis. A minimally invasive or invasive biopsy is then carried out, followed by histological analysis to determine the type and stage of cancer, a vital phase in clinical cancer treatment [8]. Even though these conventional techniques for diagnosis and therapy have been essential, they are sometimes imprecise, only work well for moderately to severely advanced cancers, and have drawbacks such as cytotoxicity and drug resistance [9].

In recent years, technological innovations and multi-omics approaches have transformed cancer research by providing comprehensive insights into cancer biology at multiple molecular levels. While Lu et al. (2020) emphasized the importance of integrating multi-omics for cancer research and clinical outcomes, our review builds upon this by incorporating recent advancements in specific technologies, such as single-cell profiling, CRISPR-based functional genomics, and AI-driven data analytics. These developments offer an updated and broader view of how multi-omics can enhance cancer diagnostics, personalized therapies, and the understanding of tumor heterogeneity [10]. Multi-omics approaches are vital in comprehending complex biological processes, identifying new biomarkers, and creating personalized therapies for cancer and other diseases [11]. These multi-omics technologies have been employed in breast cancer research to explore different phenotypes, biomarkers, and treatment strategies [12]. Integrating advanced technologies from several fields, including genetics, stem cell research, molecular imaging, and bioinformatics, is essential for advancing cancer research and enhancing diagnostic and therapeutic results [13]. These technological advancements are facilitating a move toward predictive, preventive, and personalized approaches in cancer care.

Multi-omics techniques in cancer research combine several datasets to improve comprehension of the molecular and clinical features of malignancies [14]. These techniques integrate genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics to meticulously understand carcinogenesis at multiple biological levels [15]. Emerging as a transforming technology, spatial multi-omics allows cells inside tissues to be precisely located and the gene expression to be measured in situ. With applications in neurology, developmental biology, and cancer research, this finding represents a significant technical rise in life sciences and biomedicine [16]. Multi-omics techniques provide paths for diagnosis, improved prognosis, and cancer subtyping. They help to identify clinical procedures, genetic driver alterations, and cancer subtypes [17]. Examining multi-omics data helps translational research via integrated models, explains cellular responses to therapy, improves the grouping of samples into relevant physiological categories, and provides better knowledge of prognostic and predictive phenotypes [18]. Although their benefits exist, obstacles persist in clinical adoption, such as the disparate maturity of various omics methodologies and the need for standardized processing and analytical frameworks [19]. As technologies advance and costs decrease, multi-omics will continue revolutionizing biomedical research, offering insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets [20]. Hence, the present review comprehensively analyses the impact of technology advancements and multi-omics strategies on the progression of cancer research. It emphasizes crucial technologies, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), single-cell profiling, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas systems, artificial intelligence (AI), and spatial transcriptomics, that have transformed the comprehension of cancer biology. Multi-omics layers, including genomes, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics, are examined for their roles in elucidating molecular pathways, tumor heterogeneity, and biomarker identification. The integration of multi-omics data is examined for its potential applications in systems biology, customized medicine, and pharmacological development. This study highlights the essential function of multi-omics in enhancing precision oncology and optimizing patient outcomes.

The comprehensive literature search was conducted using various electronic databases such as PubMed, Elsevier, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Embase, and NCBI. We have reviewed the last 15 years of articles that were published from 2010 to 2025. Specific keywords were used to search the articles, such as “cancer, multiomics approaches, sequencing techniques, CRISPR/CAS9, AI & ML approaches, imaging and diagnostics, genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and high throughput sequencing” combined with Boolean operators AND/OR. The inclusion criteria were applied to select the articles: (i) Research on technical advancements (e.g., sequencing, CRISPR, artificial intelligence/machine learning, imaging) in oncology. (ii) Investigate the use of multi-omics (genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) in oncology. (iii) Publications that include technology and multi-omics for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment. (iv) Research, reviews, clinical trials, case reports, and experimental, pre-clinical, and clinical studies were included.

3 Overview of Molecular Mechanisms and Pathways in Cancer

The development of cancer depends on intricate molecular systems and signaling networks. Like p53, mutations in proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes may cause uncontrolled proliferation of cells and metastasis [21]. Tumor cells exhibit a series of traits or hallmarks, such as unregulated growth, genomic instability, and evasion of apoptosis. The complexity of cellular signaling networks profoundly affects our comprehension of tumor cell behavior and our capacity to use this information in cancer treatment [22]. Cellular signal transduction is a crucial mechanism in the advancement and evolution of cancer. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway consists of numerous essential signaling components and phosphorylation events that are pivotal in carcinogenesis [23]. The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein Kinase B is a serine/threonine kinase (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway is crucial for tumor cell proliferation and viability, often playing a role in oncogenesis. Aberrant stimulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling leads to the accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus, facilitating the transcription of several oncogenes and contributing to carcinogenesis and tumor growth. Therapeutic interventions at the MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways represent a potential method [24]. Important in cancer development are adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin; leptin promotes tumour growth, whereas adiponectin shows negative correlations with cancer risk [25]. Important paths include cell cycle control, DNA damage response, epigenetic modifications, and miRNA regulation. Greater proliferation, metabolic changes, resistance to apoptosis, genetic instability, angiogenesis, and increased motility define cancer cells [26]. Comprehending these molecular processes and mechanisms has resulted in identifying prospective therapeutic targets and creating innovative targeted medicines for diverse cancer types. Fig. 1 shows a summary of the main signaling routes engaged in cancer development.

Figure 1: Important signaling routes in cancer progression, including proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastases, are shown in this figure. It emphasises carcinogenic pathways including p53 (tumor protein 53), RAS/MAPK (Rat sarcoma/mitogen-activated protein kinase), TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta), Wnt/β-catenin (wingless-related integration site/β-catenin), and PI3K/Akt/mTOR (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mechanistic target of rapamycin). Receptor tyrosine kinases are stimulated by growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular signals, hence generating intracellular signaling cascades. Unchecked cell proliferation, escape from death, and therapeutic resistance may all result from dysregulation of these pathways. The figure was created using BioRender.com

4 Technological Innovations Transforming Cancer Research

4.1 High Throughput Sequencing Technologies

In 1977, Sanger and Gilbert simultaneously published two distinct techniques that revolutionized DNA sequencing. Their pioneering work cleared the path for creating more efficient and rapid sequencing technology and a thorough comprehension of the genetic code [27]. Although essential, Sanger sequencing was constrained and expensive for whole genome sequencing (WGS). As a result of the shortcomings of first-generation sequencing techniques, high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies were developed, which can sequence small DNA fragments in massive parallel [28]. In the early 2000s, various HTS techniques were labeled as NGS or second-generation sequencing. While these methods have made significant progress in terms of speed and cost, they still depend on Polymer Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification. This can introduce biases during amplification and usually produces shorter reads, typically between 20 to 200 base pairs. As a result, this can lead to misassemblies and gaps in the sequencing data [29]. To tackle these issues, third-generation HTS technologies have been developed, including Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT). These technologies provide extended read lengths and eliminate the need for clonal amplification; nonetheless, they are often more expensive than second-generation approaches [30]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a multifaceted system including various pro- and antitumor cellular elements or signals that may modulate tumor growth and influence the effectiveness of the antitumor immune response [31]. Tissue-based sequencing methodologies examine a cellular cohort, yielding an average representation of gene expression within that population. This technique may provide valuable insights into cellular processes and activities, but it may overlook important changes and distinctions among individual cells [32]. One of the main limitations of bulk sequencing is that it lacks the resolution to capture cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types. It may miss critical treatment resistance or metastatic pathways. It is reasonably affordable and appropriate for determining average gene expression across cell groups [33]. In contrast, single-cell sequencing gives high-resolution data that may identify tumor subpopulations and gene expression patterns. But it creates complicated datasets, costs more, and demands more processing resources for analysis, which can limit its broad use in clinical practice. Moreover, single-cell sequencing introduces additional complexities, such as drop-out rates and low RNA capture efficiency, which can skew results and make interpretation challenging [34]. The introduction of HTS technology permits sequencing at the single-cell level. This allows us to exceed the limits of tissue-based sequencing [35]. High-throughput single-cell sequencing techniques analyze individual cells in multiple dimensions, encompassing their genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles [36]. In contrast to conventional bulk sequencing methods, cell sequencing has the notable benefit of assessing heterogeneity within a cell population, identifying cells with a limited quantity and highly specific phenotypes, and inferring cellular activity [37]. In the first phase of single-cell sequencing, its use is significantly constrained by inadequate throughput and elevated detection costs. Currently, the rapid advancement of single-cell sequencing technology has led to its extensive use across many research domains, notably in cancer research [38]. Furthermore, a novel approach called spatial transcriptomics gives gene expression profiling spatial resolution so that researchers may directly trace RNA expression within tissue architecture. In cancer, especially, this is rather important as it retains the geographical background of tumor-immune interactions and cellular microenvironments [39]. By integrating transcriptome data with geographical information, researchers may more precisely detect niche-specific gene expression and tumor heterogeneity. Spatial transcriptomics enhances single-cell RNA sequencing by providing positional context, crucial for comprehending tumor architecture and therapeutic resistance [40]. However, spatial transcriptomics is an emerging discipline. A present limit is the challenge of attaining high resolution across extensive tissue sections, and the prohibitive cost of these methods has restricted their broad use [41]. Xie et al. (2020) used HTS to analyze the vaginal microbiota in healthy women, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) patients, and cervical cancer patients. The study found that cervical cancer was associated with reduced Lactobacillus (probiotics) and increased pathogens such as Prevotella, Sneathia, and Pseudomonas [42]. Fig. 2 illustrates the HTS technologies and their applications in cancer research. This high-throughput approach demonstrated strong potential for non-invasive early-stage lung cancer detection.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies in cancer. The figure emphasises important HTS techniques, the sequencing workflow, and their uses in cancer research, including early detection, mutation profiling, and personalized therapy, including Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), and RNA-sequencing. The figure was created using BioRender.com

Liang et al. (2019) utilized high-throughput DNA bisulfite sequencing to profile methylation patterns in tissue and plasma samples, enabling differentiation between malignant lung tumors and benign nodules. Tissue-based markers achieved 92.7% sensitivity and 92.8% specificity, while a plasma assay built from filtered markers showed 79.5% sensitivity and 85.2% specificity [43]. The research demonstrated considerable heterogeneity in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) mutations through Single-cell RNA sequencing and identified essential genes, such as ELF3, that mediate interactions between tumor cells and their tumor microenvironment components, indicating that ELF3 may serve as a therapeutic target in LUAD for future pharmacological development [44]. The results of Pellini and Chaudhuri (2022) show that next-generation sequencing-based circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) tests may identify minimum residual disease (MRD) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It demonstrates high sensitivity (36%–100%) and specificity (71%–100%) for relapse prediction, improving further with extended surveillance. The study emphasizes the need for prospective validation to refine ctDNA MRD’s clinical utility in relapse monitoring and treatment optimization [45]. NGS identified somatic mutations in tumor tissues from localized colon cancer patients, achieving an 88% detection rate. The circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) tracking in plasma samples revealed MRD and predicted relapse risk, offering a reliable tool for early detection of recurrence and monitoring treatment outcomes [46]. Single-cell RNA sequencing and Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing (CITE-seq) revealed dynamic myeloid changes in glioblastoma, with microglia-derived Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) prevalent in early tumors and monocyte-derived TAMs dominating after recurrence, offering insights for targeted therapies [47]. Zavidij et al. (2020) reported that the Single-cell RNA sequencing of bone marrow cells revealed immune changes in multiple myeloma progression, including increased natural killer cells, loss of granzyme K+ cytotoxic T cells, and T-cell suppression due to MHC class II dysregulation in monocytes, aiding immune-based patient stratification [48]. Hence, the technological advancements and the extensive use of HTS analysis may facilitate the identification of innovative insights into cancer treatment, which may then be applied in clinical settings.

4.2 Imaging and Diagnostic Advancements in Oncology

Oncological imaging developments have recently greatly enhanced cancer detection, characterization, and therapy monitoring [49]. Using specific probes tagged with radioactive isotopes or fluorescent dyes, molecular imaging modalities, including single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hyperpolarization MRI, molecular optical imaging, positron emission tomography (PET), and ultrasonic imaging, identify cancer-related molecular characteristics in cancer diagnostics [50]. Imaging modalities with cancer-specific biomarkers provide significant advantages for early cancer detection, including enhanced accuracy in identifying genetic modifications, non-invasive visualization of tumor attributes, and rapid detection of detectable morphological abnormalities [51]. MRI is safer for regular assessments than other imaging methods because it does not involve ionizing radiation, unlike other imaging methods, especially in the treatment of chronic diseases like cancer. Recent developments in MRI methodologies have markedly enhanced diagnostic capabilities [52]. In diagnosing breast cancer, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) is quite successful. While MR spectroscopy offers information on tumor grade and treatment response, it helps in lesion diagnosis depending on vascular properties [51,53]. Furthermore, innovative techniques like magnetic particle imaging and perylene diimide-grafted nanoparticles are developing as viable alternatives that may improve tumor visibility and targeted treatment. These improvements seek to enhance specificity and sensitivity in the identification of cancerous tissues [54]. The hyperpolarized MRI has resulted in significant improvements in imaging capabilities. Clinicians may examine numerous metabolic processes changed in cancer cells, such as glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, by using hyperpolarized 13C-labeled substrates. This method facilitates the detection of malignant tumors and offers insights into tumor aggressiveness and treatment effectiveness [55]. According to Sarkaria et al. 2023, the randomized controlled trial for intraoperative molecular imaging with pafolacianine greatly enhanced tumor identification during lung cancer surgery. In 19% of patients, primary tumors were discovered that were not visible with white light, and occult synchronous malignant lesions were identified in 8%. Furthermore, in 38% of instances, it showed surgical margins of ≤10 mm, allowing for more accurate resections and modifications to the surgical plan [56]. Jiao et al. (2022) used SPECT imaging to assess the diagnostic efficacy of [99mTc] Tc-labeled aptamer-siRNA chimeras in PSMA-positive prostate cancer (PCa). SPECT imaging in 22Rv1 xenograft mice exhibited distinct tumor visibility with elevated tumor-to-muscle (T/M = 4.63 ± 0.68) and tumor-to-blood (T/B = 3.61 ± 0.7) ratios at 2 h post-injection, validating the efficacy of the molecular probe for targeted imaging in prostate cancer [57]. For molecular imaging of gastrointestinal cancer, a leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) targeting peptide probe IPQILSI was developed. Tagged with FITC and Cy5.5, the Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ) displayed more fluorescence in gastric cancer cells than in Intrahepatic Cholangio Carcinoma (ICC) and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) studies using controls [58]. Positron Emission Mammography (PEM) is a specialist breast imaging method based on PET technology designed especially for the diagnosis of breast cancer. This method has significant potential in the early detection of breast cancer and the assessment of treatment efficacy [59]. The study revealed that low-dose positron emission mammography (PEM) utilizing [18F-FDG] accurately identified 96% of invasive and in situ breast cancers, maintaining consistent efficacy even after 3 h of radiotracer uptake. PEM exhibited a lower incidence of false-positive lesions compared to MRI (16% vs. 62%), indicating its potential as a valuable imaging modality for breast cancer diagnosis [60]. The research indicated that dedicated breast positron emission tomography (DbPET) has better sensitivity (91.4%) than whole-body PET (WBPET) (80.3%) in identifying invasive breast cancer, especially for sub-centimetric lesions (80.9% vs. 54.3%). DbPET also detected more lesions across all nuclear grades [61]. Molecular optical is an innovative methodology in cancer research, using non-invasive approaches that exploit genetic markers for accurate tumor identification and treatment [62]. This approach distinguishes tumor tissues from adjacent healthy tissues by using unique biomarkers found in the tumor microenvironment, hence enabling high-resolution real-time imaging [63]. The use of ultrasound imaging in the diagnosis of cancer is well known. It helps professionals assess the size and features of masses by seeing malignancies in various body areas [64]. To get comprehensive imaging data, methods like High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) are often employed. It is used to target malignant cells efficiently without harming nearby healthy tissue by producing heat via concentrated energy that destroys tumor tissue. This minimally invasive method shows promise in the treatment of several malignancies [65].

4.3 Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches in Cancer Studies

AI and ML revolutionize cancer research and treatment. These technologies provide benefits in managing extensive data sets, increasing diagnostic precision, and strengthening clinical decision-making [66]. Timing of cancer detection, accuracy of cancer diagnosis, and staging are key determinants of tumor aggressiveness and affect clinical decision-making and outcomes. In a short span of years, AI has significantly impacted this crucial field of oncology, demonstrating performance that rivals that of human experts while also offering advantages in scalability and automation.

Applications of AI and ML in cancer are found in many fields, such as therapy selection, prognosis calculation, early diagnosis, and risk assessment. They are more accurate than physicians in predicting different forms of cancer. Multimodal data from electronic health records, medical imaging, experimental biology, and genomes may be efficiently analyzed using machine learning algorithms [67]. Numerous detailed studies on deep learning algorithms accurately diagnose cancer and differentiate between cancer subtypes using histopathological and various medical images. Deep neural networks (DNN) are robust algorithms capable of classifying extensive pictures, such as H&E-stained whole slide images (WSIs) from biopsies or surgical resections, therefore accurately assessing the presence of cancer cells on a digitized slide [68,69]. The efficacy of DNNs extends beyond histopathology to various medical imaging techniques such as CT scans, MRIs, mammograms, and photos of questionable lesions. Sekaran et al. (2020) explored a deep learning approach that utilizes a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) in conjunction with a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) and the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. Their approach shows the potential of predicting the progression of pancreatic cancer using CT scan images from a dataset of approximately 19,000 images, demonstrating the potential of early detection and treatment monitoring in pancreatic cancer [70]. Using smartphone photos, deep learning algorithms also enhance the identification of oral diseases, attaining 96.6% specificity and 84.3% accuracy. The suggested strategy improves diagnostic performance by combining a resampling methodology with a “center positioning” method, making smartphone-based AI a viable early detection tool [71]. Cancer staging and grading are crucial diagnostic steps that influence treatment choices. In prostate cancer, the Gleason score is used for staging, which measures tumor cell prevalence. DNNs have demonstrated the ability to predict Gleason scores from histopathological images of prostate cancer [72]. The Cancer of Unknown Primary Location Resolver (CUPLR), a machine learning model using 511 genetic variables, precisely identifies 35 cancer subtypes with around 90% recall and accuracy. It accurately identified the tissue of origin in 58% of CUP cases, offering an interpretable graphical report that enhances standard diagnosis [73]. A new AI pipeline predicts protein crystallization propensity at various stages, utilizing a novel feature selection method that combines Chi-square testing and recursive feature elimination. The model employs linear discriminant analysis and an optimized Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, achieving better accuracy across three datasets than existing methods. This offers an efficient solution to a key challenge in computational biology [74].

AI is advancing notably in the early identification of cancer with novel, minimally invasive techniques, such as liquid biopsies for circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Chabon et al. (2020) developed a machine learning methodology named Lung-CLiP (cancer likelihood in plasma), which assesses the probability of ctDNA presence in blood samples from lung cancer patients [75]. Many cancer labs routinely run sequencing of cancer genes, exomes, and genomes. Although various computational techniques are accessible to identify genetic variants and mutations in NGS data, these techniques may sometimes be useless in certain contexts. Using gene length-normalized somatic mutation data, a machine learning method was developed to monitor the tissue-of-origin (TOO) of cancer of unknown primary (CUP). The model employing somatic mutation data from 4909 samples across 13 cancer types obtained an average accuracy of 88.22% and an F1-score of 88.86% using a 600-gene set and random forest method. Combining machine learning with DNA sequencing, this computational method is a useful instrument for enhancing CUP diagnosis and therapy [76]. AI, especially deep learning and machine learning algorithms, has emerged as a potential solution to the issues encountered in drug design and discovery [77]. Drug discovery and design involve complex processes such as target identification, therapeutic screening, optimization of lead compounds, preclinical and clinical trials, and manufacturing techniques, each posing significant challenges in finding effective medications for various illnesses [78]. Chebanov et al. (2023) devised an algorithmic platform for the identification of small-molecule anti-tumor drugs in lung cancer. Utilizing deep learning and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), they identified critical genes associated with unfavorable outcomes and predicted drug-target interactions and IC50 values. The platform facilitated virtual trials, leading to the identification of promising anti-tumor compounds for targeted therapies [79]. Developed DeepCancerMap, a deep learning-based platform for anticancer drug discovery using Fingerprint and Graph Neural Network (FP-GNN) models. By analyzing 485,900 compounds across 426 targets and 406 cancer cell lines, the models achieved high predictive performance with AUC values up to 0.91. DeepCancerMap enables virtual screening, target prediction, and drug repositioning, offering a valuable tool to accelerate anticancer drug discovery [80]. The study by Zhou et al. (2022) revealed that the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) predicts survival in primary breast cancer using tumor size, lymph node count, and tumor grade. This study used t-SNE embedding to map omics data into 2D and integrated it into a ResNet model for multi-class NPI prediction, achieving 98.48% accuracy and AUC 0.9999, outperforming other methods. Key biomarkers linked to breast cancer prognosis included CDCA5, IL17RB, MED30, and CENPA, providing insights into survival prediction [81]. The reduction of research expenditures and acceleration of the medication development process has become imperative for the advantage of both pharmaceutical manufacturers and patients. The evolution of machines or AI now guides early-stage drug design and discovery in the current big data era. The success stories in this regard provide us with clear evidence that AI will reveal its great potential in accelerating effective new drug findings. However, the inadequate experimental validation of predicted molecules, which postpones clinical translation, is still a significant barrier to AI-driven drug development. Furthermore, bias in training datasets might cause discovery pipelines to be biased towards well-characterized targets, underexploring uncommon or new targets [82].

4.4 CRISPR and Gene Editing in Cancer Research

Gene editing has advanced significantly in recent years, particularly with the use of CRISPR/Cas9. The rapid advancement of gene editing methods has made them more important in medicine [83]. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique is potent, exhibiting excellent specificity and high efficiency, enabling precise and speedy genome-wide screening, hence enhancing the implementation of gene therapy for certain disorders [84]. Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9 technology is used in tumor research to look at the pathways behind tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Studies on cancer therapy have been using this technique even more often. By altering specific genes or fixing genetic abnormalities, CRISPR/Cas9 presents possible therapeutic approaches to fight cancers [85]. Liu et al. (2021) investigated the function of Pumpilio RNA Binding Family Member 1 (PUM1) in acquired resistance to cetuximab in colorectal cancer via the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing method. Research indicated that PUM1 enhances DEAD Box Helicase 5 (DDX5) expression and facilitates cell proliferation in resistant colorectal cancer cells. The knockout of PUM1 or DDX5 enabled these cells to be more susceptible to cetuximab, indicating their potential as therapeutic targets to address drug resistance [86]. The implementation of an innovative lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery technology for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated cancer therapies, targeting issues of inadequate editing efficiency and toxicity. The designed lipid nanoparticles enabled effective in vivo gene editing, attaining over 70% editing in glioblastoma and around 80% in ovarian cancer models. This led to considerable tumor growth suppression and enhanced survival rates [87]. The study utilized CRISPR technology to create stable wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1 (WHSC1) mutant cells, revealing a functional regulatory interaction between High Mobility Group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2) and WHSC1 in colon cancer. WHSC1 was found to promote cancer cell proliferation, enhance chemotherapy resistance, and increase metastatic potential, indicating its potential as a novel therapeutic target for colon cancer treatment [88]. Multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in T cells for cancer immunotherapy proved safe and feasible in phase 1 trials. Emphasizing the promise of CRISPR-Cas9 to improve T cell-based cancer therapy, the modified T cells survived long-term, displayed efficient tumor targeting, and had no related toxicity [89]. This study uses CRISPR-Cas9 to enhance photodynamic therapy (PDT) by silencing Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2), reducing cancer cell resistance to Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). A Single Standard Deoxyribonucleic Acid (ssDNA) scaffold enables controlled co-delivery of Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP), hemin, and protoporphyrin (PP). Up Conversion Nanoparticles (UCNPs) convert Near Infra-Red (NIR) light for deeper activation, while a DNAzyme boosts oxygen levels to overcome hypoxia. This synergistic approach significantly improves PDT efficacy in breast cancer models [90]. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system has significant potential for research and clinical applications in cancer treatment (Fig. 3). Significant obstacles remain in the advancement of CRISPR/Cas9 technology as a standard therapy for solid tumors. Challenges ahead include production timelines, elevated manufacturing costs, off-tumor effects, CAR-T delivery, trafficking, tumor invasion, and related safety and toxicity.

Figure 3: Applications of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) in cancer research. The figure emphasizes important areas of CRISPR, such as cancer gene editing for therapy, oncogene knockout and tumor suppressor restoration, CRISPR-based biosensors for early cancer detection, disease models for researching tumor progression, mutation screening for genetic changes, immune therapy enhancement by immune cell modification, and drug target identification for precision oncology. The figure was created using BioRender.com

5 Multi-Omics Approaches in Cancer Research

Multi-omics offers a complete picture of interactions across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic elements, therefore guiding the understanding of cancer formation and progression [91]. Single-level omics methodologies often do not succeed in establishing causal relationships between molecular changes and phenotypic results. Conversely, systems biology amalgamates several regulatory levels, facilitating a comprehensive knowledge of complex disorders such as cancer [19]. By analyzing biological samples across multiple omics scales, researchers can better understand genetic and environmental influences on disease. Multi-omics data analysis enhances sample classification, refines prognostic and predictive markers, and deciphers cellular responses to therapy [92]. Advances in high-throughput technologies, large-scale collaborations, and computational algorithms have driven the adoption of multi-omics in cancer research, improving diagnostic and prognostic predictions by uncovering key molecular interactions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Multi-omics approaches and AI-driven data integration in combining genomes, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics data, with the bioinformatics and artificial intelligence analyzing tools used to improve biomarker discovery, personalized treatment, tumor categorization, therapeutic target identification, and cancer progression monitoring. Effective clinical translation depends on addressing issues such as data complexity, processing requirements, and the necessity for standardizing effective clinical translation. The figure was created using BioRender.com

Cancer genomics involves studying the complete set of DNAs (genome) in cancer cells, including the identification of mutations, gene expression changes, and epigenetic modifications [93]. Cancer genomics advances precision medicine by identifying and categorizing cancer types and subtypes based on their genetic makeup, which results in more accurate diagnoses and customized treatment options [94]. Genomic testing, which examines the genome within cancer cells, provides information on how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and whether certain treatments are likely to be effective [95]. It involves investigating alterations at the DNA level using polymerase chain reaction and genomic hybridization techniques. These methods facilitate classifying cancers based on genetic alterations, such as Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutations in papillary tumors and TP53/RB1 mutations in non-papillary tumors [96]. Improvements in sequencing and genomic technologies, coupled with refined analytical methods, permit the evaluation of how germline and somatic genetic variations impact carcinogenesis and metastasis. This progress aids in discovering new molecular targets and companion diagnostics, thereby transforming the approaches employed by geneticists and oncologists in cancer diagnosis, etiology, and treatment [97]. Analysing gene expression data, like that available in the Kent Ridge Bio-Medical Dataset Repository for lung cancer, can help predict an individual’s susceptibility to cancer. Combining gene expression data with advanced machine-learning techniques makes it possible to identify candidate genes that have prognostic value in determining cancer susceptibility [98]. The cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics provides an open-access resource where researchers can explore multidimensional cancer genomic datasets and link them to clinical outcomes, aiding in discovering new biomarkers and understanding disease mechanisms [99]. Additionally, UCSC Xena offers tools for visual exploration of public and private omics data, integrating various data types such as expression profiles and phenotypic annotations [100]. The application of machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), is expanding in cancer genomics. SVMs are utilized for classifying and subtyping cancer based on genomic data, enabling the identification of new biomarkers and drug targets [101]. The study evaluated the PCDG-Pred genomics-driven ML model for identifying cancer driver genes from sequencing data. Unlike frequency-based methods, it prioritizes biologically significant mutations. Rigorous validation shows high accuracy (91.08% self-consistency, 87.26% independent set, 92.48% cross-validation), making it a powerful tool for precision oncology [102].

Transcriptomics is a rapidly advancing area of molecular genetics that has seen significant progress in recent years. The transcriptome refers to the complete collection of all RNA molecules generated from the genome in a particular cell, at a specific developmental stage, and under distinct physiological or pathological conditions [103]. It includes non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), each unique molecule contributing a distinct range of activities within the cell and reacting differently to external stimuli, as well as protein-coding RNAs (pcRNAs), commonly referred to as messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [104]. The transcriptome profile can be viewed as a snapshot of a cell’s transient state, and its analysis provides insights not only into gene function but also into genome plasticity, mechanisms of gene expression regulation, and variations in individual transcripts [105]. Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful approach to studying tumor-stroma interactions in various cancers. In advanced High Grade Serous Carcinoma (HGSC), integrating spatial transcriptomics with single-cell RNA sequencing identified a specific Cancer Associated Fibroblast (CAF) subtype whose spatial positioning correlates with long-term survival. Additionally, increased APOE-LRP5 signaling at the tumor-stroma interface in short-term survivors suggests a potential biomarker for patient outcomes [106]. Similarly, spatial transcriptomics has been used to investigate cell interactions at the colorectal cancer (CRC) invasion front, revealing that CRC cells induce Human Leukocytic Antigen-G–G (HLA-G) expression, leading to the recruitment of SPP1+ macrophages. This signaling enhances immune evasion, proliferation, and invasion, emphasizing critical tumor-stroma interactions as potential therapeutic targets [107]. The study analyzes 36,424 single cells from 13 prostate cancer tumors, revealing significant transcriptomic heterogeneity. It identifies epithelial cells linked to disease aggressiveness and changes in the tumor microenvironment. The study also reveals active communication between tumor cells and an endothelial subset, which promotes invasion in castration-resistant prostate cancer [108]. The investigation of the genomic and transcriptome profiles of 738 treated rectal tumors revealed that the overexpression of Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 (IGF2) and L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule (L1CAM) reduces the responsiveness to neoadjuvant treatment. Furthermore, RNA-sequencing results imply that a subpopulation of immunologically hot microsatellite-stable tumors has a stronger response and longer disease-free survival [109]. Transcriptome analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from patients with pancreatic and bile duct cancers revealed that most neoantigen-reactive CD8+ T cells exhibited signs of exhaustion, with significant co-expression of Granzyme A (GZMA) and C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 13 (CXCL13). In bile duct cancer, neoantigen-reactive CD4+ T cells also displayed an exhausted phenotype, characterized by the absence of Interleukin 7 Receptor (IL7R) expression and overexpression of Homeodomain Only Protein X (HOPX) or Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor G1 (ADGRG1). These findings highlight distinct transcriptome profiles of neoantigen-reactive T cells that could inform treatment strategies [110].

Proteomics has emerged as a powerful tool in cancer research, offering insights into tumor biology, biomarker discovery, and drug development. Various proteomic technologies, including mass spectrometry, protein microarrays, and gel electrophoresis, enable researchers to analyze protein expression profiles, post-translational modifications, and signaling pathways in cancer [111]. These approaches have applications in the early detection, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring of cancer. Proteomics also facilitates the identification of novel drug targets and evaluating drug efficacy and toxicity [112]. The study revealed that proteomics is valuable for examining NSCLC patients undergoing immunotherapy. Plasma proteomic analysis identified 142 upregulated proteins, with soluble PD-1 correlating with tumor PD-L1 status and survival. A 30-protein network, including CD8A, indicated T cell activation, while alveolar-derived proteins were linked to poor response. These findings highlight the potential of proteomics in identifying biomarkers for treatment response and resistance [113]. Furthermore, proteomics points to SMAD3 as a potential target for disulfiram-cisplatin combination treatment; hence, down-regulating SMAD3 may enhance cisplatin-induced cell death in ovarian cancer [114]. The study showcases proteomics as a powerful approach for breast cancer classification, analyzing 300 Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples across Prediction Analysis of Microarray 50 (PAM50) subtypes. It identifies distinct basal-like and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-enriched subgroups, as well as four triple-negative clusters with immune and metabolic differences linked to survival, highlighting potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [115]. The pilot proteomics study analysis identified a four-protein signature (OGN, LUM, DCN, COL14A1) that is capable of differentiating breast cancer. SWATH-based mass spectrometry revealed 370 differentially abundant proteins with consistent validation across multiple proteomics and transcriptomics datasets. ROC analysis showed high diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.87–0.9, 80% 82%), improving in Basal-Like/Triple-Negative subtypes (AUC 0.922–0.959, 84.2%–89%). These findings highlight the potential of this protein signature to enhance breast cancer diagnostics [116]. The study revealed proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiles of Endometrial Cancer (EC) tumors, identifying dysregulated proteins and phosphosites. It classifies EC into two molecular subtypes (S1 and S2), with S2 being more aggressive and characterized by upregulated spliceosomal and ribosomal proteins. A subtype signature (ELOA and SCAF4) is identified, leading to the development of a diagnostic and prognostic model [117].

Metabolomics is the systematic analysis of various metabolites, including nutrients, drugs, signaling molecules, and the metabolic byproducts of these small molecules, found in blood, urine, tissue extracts, and other bodily fluids. It is a powerful approach for discovering cancer biomarkers and identifying factors that drive carcinogenesis [118]. It enables deeper investigation into cancer metabolism, particularly the Warburg effect, and aids in understanding how cancer cells utilize metabolic pathways for tumor proliferation. Metabolomics has shown promise in discovering diagnostic biomarkers, elucidating cancer’s complex nature, identifying potential therapeutic targets, and monitoring treatment responses [119]. Metabolic reprogramming is a key feature of cancer, enabling cells to adapt and thrive in harsh conditions, promoting proliferation, survival, and metastasis. This reprogramming involves changes in intracellular metabolism, facilitating the survival and spread of cancer cells [120]. Techniques such as stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) combined with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry are used to analyze metabolic pathways and networks, offering a detailed understanding of drug actions and metabolic changes in cancer [121]. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI)-based metabolomics can visualize the spatial reprogramming of metabolism in heterogeneous cancers, revealing novel vulnerabilities for cancer therapy [122]. Cancer metabolomics faces challenges in obtaining robust sampling methods, distinguishing cancer-specific signals from systemic influences, and addressing inconsistencies in cell culture conditions. Traditional metabolic pathways like the Warburg effect limit the exploration of novel targets, necessitating precise technologies for tumor heterogeneity [123]. The AI-based deep learning methods are suitable for classifying metabolomics data. For example, a deep learning framework was highly accurate, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.93, when classifying ER+/ER− patients with breast cancer. The biological interpretation of the first hidden layer revealed eight commonly enriched significant metabolomics pathways (adjusted p-value < 0.05) that other machine-learning methods could not discover [124]. The research demonstrated that the Metabolomic analysis of gut microbiota in NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab revealed that 2-pentanone and tridecane were associated with early progression, while Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), lysine, and nicotinic acid correlated with long-term benefits. These findings suggest a potential role of gut microbiota metabolism in influencing immunotherapy response [125].

6 Applications of Multi-Omics Data Integration in Clinical Oncology

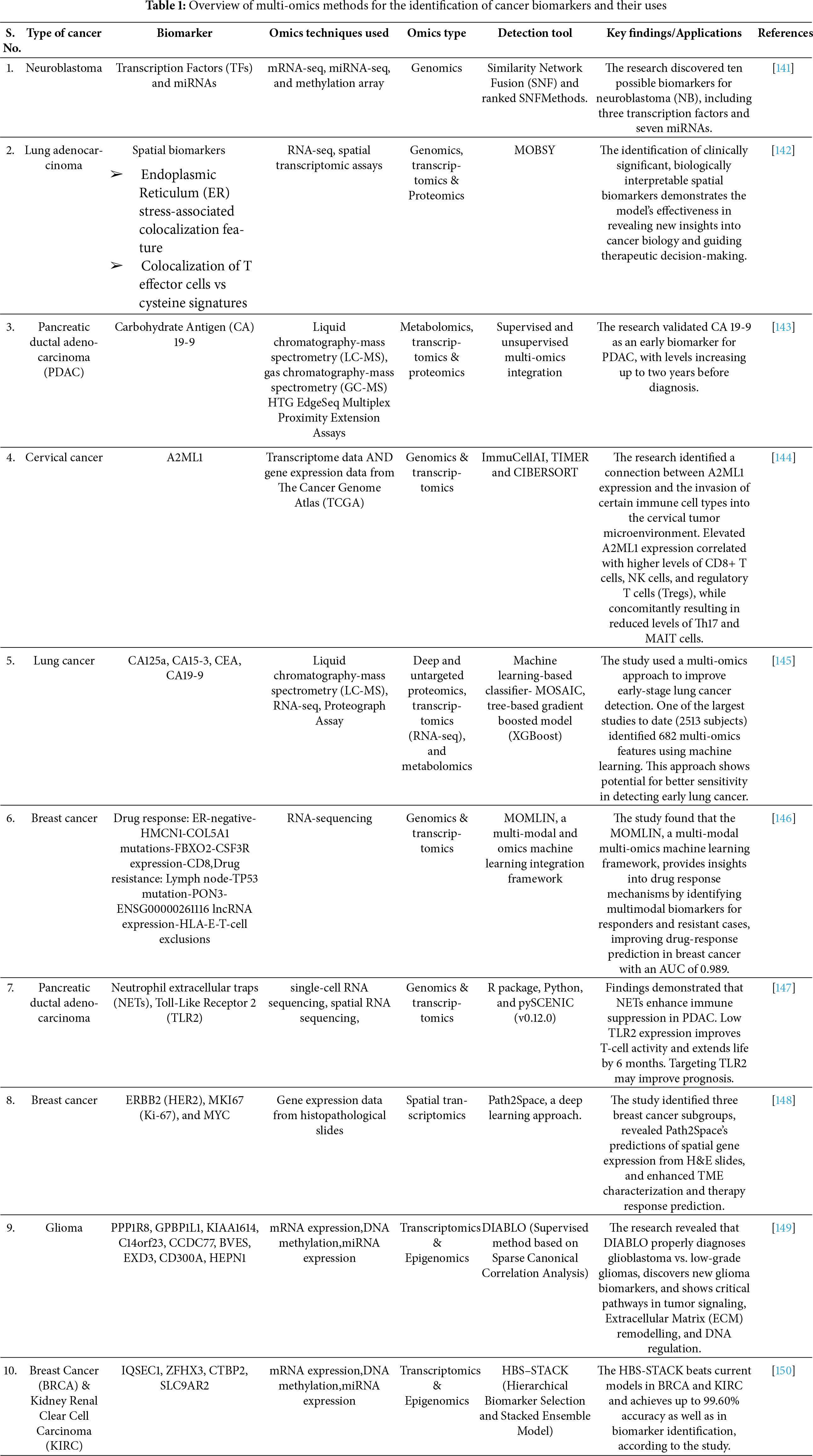

Multi-omics approaches in clinical oncology integrate data from various molecular levels to enhance precision medicine. These technologies enable comprehensive tumor profiling, including spatial genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, as well as liquid biopsy and ex vivo drug response modelling [126]. Multi-omics data integration facilitates cancer subtyping, prognosis, and diagnosis by revealing underlying disease mechanisms and driver genomic alterations [127]. Machine learning methods, such as deep learning, network-based approaches, and clustering, have been developed to analyze complex multi-omics datasets for patient phenotyping, biomarker discovery, and drug repurposing [128]. Despite the potential of multi-omics in advancing precision oncology, challenges remain in standardizing sample processing, analytical pipelines, and data interpretation. Multi-omics data integration is used for developing classification systems for prognostic prediction. In muscle-invasive bladder cancer, which is a common urinary system carcinoma, such systems are especially needed due to poor outcomes [129]. A survival stratification model based on multi-omics integration using bidirectional DNNs has been developed for gastric cancer, grouping patients into different survival subgroups. This model has been validated and shown to be robust and stable [130]. Integration of spatial multi-omics data can reveal faulty metabolism-driven networks, improving diffuse glioma penetration. While maintaining the spatial organization of cells, spatial multi-omic profiling makes a thorough study of transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics possible on the same tissue section. This integration facilitates the inference of the implications of intricate cell-cell communication under tumor invasion and suggests approaches to target ligand-receptor networks to reduce glioma invasion and enhance clinical outcomes. Additionally useful for therapeutic targets in cancer patients are isoform variations found by multi-omics data integration [131,132]. The integration of multi-omics data helps to improve knowledge of tumor heterogeneity. A novel multi-omics approach identified a hybrid breast cancer subtype (Mix Sub) that contributes to tumor heterogeneity with a poor prognosis, characterized by low immune infiltration, T-cell dysfunction, and altered Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (NCAM1)-FGFR1 signaling. This subtype showed significant changes in cell cycle, DNA damage, and DNA repair pathways, along with increased sensitivity to targeted therapies. Prognostic models and subtype classifiers were validated in external datasets, highlighting their potential for precision therapy [133]. The integration of multi-omics expression data from transcriptomic and metabolomic sources reveals heterogeneity within tumors and identifies potential treatment targets in pediatric ependymoma. This method highlights possible treatment targets by pointing up dysregulated metabolic paths and gene-metabolite interactions [134]. Integration of multi-omics data clarifies and cross-annotates programs found in mass spectrometry datasets in glioblastoma, hence highlighting tumour cell invasion and drug resistance [135]. The paper introduces Multi-Omics Data Integration for Clustering to Identify Cancer Subtypes (MDICC), a multi-omics data integration strategy that uses network fusion and an affinity matrix to cluster cancer subtypes. MDICC outperforms current clustering techniques in identifying cancer subtypes, and its efficacy and generalizability are demonstrated through survival analysis, indicating it offers equivalent or better results than current integrative methods [136]. Lu et al. (2020) study introduced MOVICS as an R package for multi-omics integration and visualization in cancer subtyping. It supports 10 state-of-the-art clustering algorithms, key downstream analyses, and external validation. With customizable visualizations, MOVICS facilitates precise patient stratification, as demonstrated in breast cancer cohorts, aiding personalized cancer therapy [137]. Yin et al. (2022) introduced the Multi-omics Graph Convolution Network (M-GCN), a novel graph convolutional network framework for cancer subtyping using multi-omics data. By selecting subtype-related transcriptomic features with Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) Lasso and constructing a low-noise similarity graph, M-GCN integrates gene expression, Single-Nucleotide Variant (SNV), and Copy Number Variant (CNV) data to learn multi-view sample representations. Experimental results on breast and stomach cancer show superior classification performance compared to existing methods [138]. Patient-specific multi-omics data integration can help identify and develop personalized combination therapies. Combination therapy, which involves treating a disease with two or more drugs, is a basis for cancer care [139]. Multi-omics data integration captures tumor characteristics at the microscopic, macroscopic, and clinical levels, providing a more comprehensive risk assessment and facilitating personalized therapies. This synergistic value of integrated diagnostic methods can improve risk assessment and pave the way for more personalized treatment planning [140]. Table 1 provides an overview of multi-omics techniques used for cancer biomarker discovery. It covers many cancer types, related biomarkers, omics methods used, and detection tools used. Significant findings emphasize the relevance of these biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans.

7 Conclusions and Future Directions

In conclusion, this review highlights the profound impact of technological innovations and multi-omics approaches in revolutionizing cancer research, from enhanced diagnostics to personalized therapeutics. High-throughput sequencing, advanced imaging, AI-driven analytics, and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing are collectively enabling a deeper understanding of cancer biology at multiple levels. The integration of genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics, along with spatial multi-omics, is pivotal for dissecting tumor heterogeneity and identifying novel therapeutic targets. Moving forward, it is crucial to address existing challenges in data integration, standardization, and clinical implementation of multi-omics. Future research should focus on validating multi-omics-based biomarkers in larger cohorts, leveraging AI for predictive modelling, and refining liquid biopsy techniques for early detection and relapse monitoring. Furthermore, enhancing CRISPR-Cas9 delivery and minimizing off-target effects are essential for advancing gene editing therapies. A greater emphasis on understanding tumor-microenvironment interactions and developing personalized combination therapies based on patient-specific multi-omics profiles is warranted. Moreover, ethical considerations must be acknowledged. AI-driven systems may demonstrate biases due to imbalanced training datasets, thereby influencing clinical decision-making. Likewise, CRISPR uses, especially in germline editing, pose substantial legal issues regarding long-term safety and heredity. Subsequent research must guarantee that these technologies can be developed ethically within well-defined ethical and regulatory parameters. Ultimately, collaborative efforts, open data sharing, and continuous technological advancements will accelerate the translation of these innovations into clinical practice, leading to more precise, effective, and personalized cancer care strategies.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the management of Chettinad Academy of Research and Education (Deemed to be University) for providing facilities to perform this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gowtham Kumar Subbaraj, Saranya Velmurugan; data collection: Saranya Velmurugan; analysis and interpretation of results: Dapkupar Wankhar, Vijayalakshmi Paramasivan, Saranya Velmurugan; draft manuscript preparation: Saranya Velmurugan, Gowtham Kumar Subbaraj. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data and materials used/analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Abbreviations

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing |

| HTS | High-Throughput Sequencing |

| PCR | Polymer Chain Reaction |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technology |

| CIN | Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| LUAD | Lung Adenocarcinoma |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| MRD | Minimum Residual Disease |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| CITE-seq | Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing |

| TAMs | Tumor-Associated Macrophages |

| DCE-MRI | Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI |

| IPQ | Illness Perception Questionnaire |

| ICC | Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma |

| FACS | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting |

| PEM | Positron Emission Mammography |

| HIFU | High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound |

| DNN | Deep neural networks |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| FP-GNN | Fingerprint and Graph Neural Network |

| PUM1 | Pumilio RNA Binding Family Member 1 |

| DDX5 | DEAD Box Helicase 5 |

| WHSC1 | Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1 |

| HMGA2 | High Mobility Group AT-hook 2 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 |

| HGSC | High Grade Serous Carcinoma, |

| CAF | Cancer-Associated Fibroblast |

| HLA-G | Human Leukocytic Antigen-G |

| IGF2 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 13 |

| IL7R | Interleukin 7 Receptor |

| HOPX | Homeodomain Only Protein X |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| NCAM1 | Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| M-GCN | Multi-omics Graph Convolution Network |

| HSIC | Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion |

| SNV | Single-Nucleotide Variant |

| CNV | Copy Number Variant |

| TFs | Transcription Factors |

| TLR2 | Toll-Like Receptor 2 |

References

1. Kondylakis H, Axenie C, Bastola D, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, Kurz D, et al. Status and recommendations of technological and data-driven innovations in cancer care: focus group study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e22034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Raqib M, George PN. TechCare: transformative innovations in addressing the psychosocial challenges of cancer care in Kerala. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2024;45(3):256–62. doi:10.1055/s-0044-1787150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kulothungan V, Sathishkumar K, Leburu S, Ramamoorthy T, Stephen S, Basavarajappa D, et al. Burden of cancers in India-estimates of cancer crude incidence, YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs for 2021 and 2025 based on national cancer registry program. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Casolino R, Mikkelsen B, Ilbawi A. Elevating cancer on the global health agenda: towards the fourth high-level meeting on NCDs 2025. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(11):933–5. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2024.07.246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pulumati A, Pulumati A, Dwarakanath BS, Verma A, Papineni RV. Technological advancements in cancer diagnostics: improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep. 2023;6(2):e1764. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dagar G, Gupta A, Shankar A, Chauhan R, Macha MA, Bhat AA, et al. The future of cancer treatment: combining radiotherapy with immunotherapy. Front Mol Biosci. 2024;11:1409300. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2024.1409300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hussain S, Mubeen I, Ullah N, Shah SS, Khan BA, Zahoor M, et al. Modern diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: a review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022(1):5164970. doi:10.1155/2022/5164970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang X, Zhang H, Chen X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019;2(2):141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Lu M, Zhan X. The crucial role of multiomic approach in cancer research and clinically relevant outcomes. EPMA J. 2018;9(1):77–102. doi:10.1007/s13167-018-0128-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Dar MA, Arafah A, Bhat KA, Khan A, Khan MS, Ali A, et al. Multiomics technologies: role in disease biomarker discoveries and therapeutics. Brief Funct Genomics. 2023;22(2):76–96. doi:10.1093/bfgp/elac017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Orsini A, Diquigiovanni C, Bonora E. Omics technologies improving breast cancer research and diagnostics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12690. doi:10.3390/ijms241612690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ibrahim HK. From nanotech to AI: the cutting-edge technologies shaping the future of medicine. Afr J Adv Pure Appl Sci. 2024;3(3):410–27. [Google Scholar]

14. Heo YJ, Hwa C, Lee GH, Park JM, An JY. Integrative multi-omics approaches in cancer research: from biological networks to clinical subtypes. Mol Cells. 2021;44(7):433–43. doi:10.14348/molcells.2021.0042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Eicher T, Kinnebrew G, Patt A, Spencer K, Ying K, Ma Q, et al. Metabolomics and multi-omics integration: a survey of computational methods and resources. Metabolites. 2020;10(5):202. doi:10.3390/metabo10050202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu X, Peng T, Xu M, Lin S, Hu B, Chu T, et al. Spatial multi-omics: deciphering technological landscape of integration of multi-omics and its applications. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):72. doi:10.1186/s13045-024-01596-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chakraborty S, Sharma G, Karmakar S, Banerjee S. Multi-OMICS approaches in cancer biology: new era in cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024;1870(5):167120. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chen C, Wang J, Pan D, Wang X, Xu Y, Yan J, et al. Applications of multi-omics analysis in human diseases. MedComm. 2023;4(4):e315. doi:10.1002/mco2.315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Menyhart O, Gyorffy B. Multi-omics approaches in cancer research with applications in tumor subtyping, prognosis, and diagnosis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:949–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

20. Mohammadi-Shemirani P, Sood T, Pare G. From ‘omics to multi-omics technologies: the discovery of novel causal mediators. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25(2):55–65. doi:10.1007/s11883-022-01078-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Dakal TC, Dhabhai B, Pant A, Moar K, Chaudhary K, Yadav V, et al. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes: functions and roles in cancers. MedComm. 2024;5(6):e582. doi:10.1002/mco2.582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ortega MA, Fraile-Martinez O, Asunsolo A, Bujan J, Garcia-Honduvilla N, Coca S. Signal transduction pathways in breast cancer: the important role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR. J Oncol. 2020;2020(1):9258396. doi:10.1155/2020/9258396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ng GY, Loh ZW, Fann DY, Mallilankaraman K, Arumugam TV, Hande MP. Role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways in metabolic diseases. Genome Integr. 2024;15(23):e20230003. doi:10.14293/genint.14.1.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Fu D, Hu Z, Xu X, Dai X, Liu Z. Key signal transduction pathways and crosstalk in cancer: biological and therapeutic opportunities. Transl Oncol. 2022;26(22):101510. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kim JW, Kim JH, Lee YJ. The role of adipokines in tumor progression and its association with obesity. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):97. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12010097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Derakhshani A, Rostami Z, Safarpour H, Shadbad MA, Nourbakhsh NS, Argentiero A, et al. From oncogenic signaling pathways to single-cell sequencing of immune cells: changing the landscape of cancer immunotherapy. Molecules. 2021;26(8):2278. doi:10.3390/molecules26082278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lee JY. The principles and applications of high-throughput sequencing technologies. Dev Reprod. 2023;27(1):9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

28. Satam H, Joshi K, Mangrolia U, Waghoo S, Zaidi G, Rawool S, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biology. 2023;12(7):997. doi:10.3390/biology13050286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Akintunde O, Tucker T, Carabetta VJ. The evolution of next-generation sequencing technologies. In: High throughput gene screening: methods and protocols. Vol. 2866. New York, NY, USA: Springer US; 2024. p. 3–29. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-4192-7_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ben Khedher M, Ghedira K, Rolain JM, Ruimy R, Croce O. Application and challenge of 3rd generation sequencing for clinical bacterial studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1395. doi:10.3390/ijms23031395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Baghban R, Roshangar L, Jahanban-Esfahlan R, Seidi K, Ebrahimi-Kalan A, Jaymand M, et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18:1–9. doi:10.1186/s12964-020-0530-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Li X, Wang CY. From bulk, single-cell to spatial RNA sequencing. Int J Oral Sci. 2021;13(1):36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Erfanian N, Heydari AA, Feriz AM, Iañez P, Derakhshani A, Ghasemigol M, et al. Deep learning applications in single-cell genomics and transcriptomics data analysis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165(5):115077. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ortega-Batista A, Jaén-Alvarado Y, Moreno-Labrador D, Gómez N, García G, Guerrero EN. Single-cell sequencing: genomic and transcriptomic approaches in cancer cell biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(5):2074. doi:10.3390/ijms26052074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Boegel S, Castle JC, Schwarting A. Current status of use of high throughput nucleotide sequencing in rheumatology. RMD Open. 2021;7(1):e001324. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Jia Q, Chu H, Jin Z, Long H, Zhu B. High-throughput single-сell sequencing in cancer research. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):145. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-00990-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chen S, Zhou Z, Li Y, Du Y, Chen G. Application of single-cell sequencing to the research of tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1285540. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1285540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Xie D, An B, Yang M, Wang L, Guo M, Luo H, et al. Application and research progress of single cell sequencing technology in leukemia. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1389468. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1389468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Jin Y, Zuo Y, Li G, Liu W, Pan Y, Fan T, et al. Advances in spatial transcriptomics and its applications in cancer research. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):129. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02040-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Huang S, Ouyang L, Tang J, Qian K, Chen X, Xu Z, et al. Spatial transcriptomics: a new frontier in cancer research. Clin Cancer Bull. 2024;3(1):13. [Google Scholar]

41. Molla Desta G, Birhanu AG. Advancements in single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics: transforming biomedical research. Acta Biochim Pol. 2025;72:13922. doi:10.3389/abp.2025.13922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Xie Y, Feng Y, Li W, Zhan F, Huang G, Hu H, et al. Revealing the disturbed vaginal micobiota caused by cervical cancer using high-throughput sequencing technology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:538336. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.538336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liang W, Zhao Y, Huang W, Gao Y, Xu W, Tao J, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of early-stage lung cancer using high-throughput targeted DNA methylation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Theranostics. 2019;9(7):2056. doi:10.7150/thno.28119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. He D, Wang D, Lu P, Yang N, Xue Z, Zhu X, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals heterogeneous tumor and immune cell populations in early-stage lung adenocarcinomas harboring EGFR mutations. Oncogene. 2021;40(2):355–68. doi:10.1038/s41388-020-01528-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Pellini B, Chaudhuri AA. Circulating tumor DNA minimal residual disease detection of non-small-cell lung cancer treated with curative intent. Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6):567–75. doi:10.1200/jco.21.01929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Tarazona N, Gimeno-Valiente F, Gambardella V, Zuniga S, Rentero-Garrido P, Huerta M, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of circulating-tumor DNA for tracking minimal residual disease in localized colon cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(11):1804–12. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Pombo Antunes AR, Scheyltjens I, Lodi F, Messiaen J, Antoranz A, Duerinck J, et al. Single-cell profiling of myeloid cells in glioblastoma across species and disease stage reveals macrophage competition and specialization. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(4):595–610. doi:10.1038/s41593-020-00789-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zavidij O, Haradhvala NJ, Mouhieddine TH, Sklavenitis-Pistofidis R, Cai S, Reidy M, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals compromised immune microenvironment in precursor stages of multiple myeloma. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(5):493–506. doi:10.1038/s43018-020-0053-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Alyehya AA, Alharbi SS, Alhejaili SE, Alhejaili AR, Alharbi FS, Muhanna SA, et al. Advancements in radiographic imaging techniques for early cancer detection. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(10):2075–86. doi:10.53730/ijhs.v6ns10.15325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Malik MM, Alqahtani MM, Hadadi I, Kanbayti I, Alawaji Z, Aloufi BA. Molecular imaging biomarkers for early cancer detection: a systematic review of emerging technologies and clinical applications. Diagnostics. 2024;14(21):2459. doi:10.3390/diagnostics14212459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Bai JW, Qiu SQ, Zhang GJ. Molecular and functional imaging in cancer-targeted therapy: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):89. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01366-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Uchikov P, Khalid U, Dedaj-Salad GH, Ghale D, Rajadurai H, Kraeva M, et al. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: advances in imaging, pathology, and personalized care. Life. 2024;14(11):1451. doi:10.3390/life14111451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Frankhouser DE, Dietze E, Mahabal A, Seewaldt VL. Vascularity and dynamic contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging. Front Radiol. 2021;1:735567. doi:10.3389/fradi.2021.735567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Li Y, Zhang P, Tang W, McHugh KJ, Kershaw SV, Jiao M, et al. Bright, magnetic NIR-II quantum dot probe for sensitive dual-modality imaging and intensive combination therapy of cancer. ACS Nano. 2022;16(5):8076–94. doi:10.1021/acsnano.2c01153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Woitek R, McLean MA, Ursprung S, Rueda OM, Manzano Garcia R, Locke MJ, et al. Hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI for early response assessment of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2021;81(23):6004–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

56. Sarkaria IS, Martin LW, Rice DC, Blackmon SH, Slade HB, Singhal S, et al. Pafolacianine for intraoperative molecular imaging of cancer in the lung: the ELUCIDATE trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;166(6):e468–78. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.02.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Jiao Y, Xu P, Luan S, Wang X, Gao Y, Zhao C, et al. Molecular imaging and treatment of PSMA-positive prostate cancer with 99mTc radiolabeled aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nucl Med Biol. 2022;104:28–37. doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2021.11.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Kwak MH, Yang SM, Yun SK, Kim S, Choi MG, Park JM. Identification and validation of LGR5-binding peptide for molecular imaging of gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;580:93–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.09.073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Cecil K, Huppert L, Mukhtar R, Dibble EH, O'Brien SR, Ulaner GA, et al. Metabolic positron emission tomography in breast cancer. PET Clinics. 2023;18(4):473–85. doi:10.1016/j.cpet.2023.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Freitas V, Li X, Scaranelo A, Au F, Kulkarni S, Ghai S, et al. Breast cancer detection using a low-dose positron emission digital mammography system. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2024;6(2):e230020. doi:10.1148/rycan.230020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Sueoka S, Sasada S, Masumoto N, Emi A, Kadoya T, Okada M. Performance of dedicated breast positron emission tomography in the detection of small and low-grade breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;187(1):125–33. doi:10.1007/s10549-020-06088-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Li Y, Li Z, Li Y, Gao X, Wang T, Ma X, et al. Optical molecular imaging in cancer research: current impact and future prospect. Cancer Transl Med. 2024;10(5):212–22. doi:10.1097/ot9.0000000000000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Wang C, Wang Z, Zhao T, Li Y, Huang G, Sumer BD, et al. Optical molecular imaging for tumor detection and image-guided surgery. Biomaterials. 2018;157(2):62–75. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.12.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Zhang G, Ye HR, Sun Y, Guo ZZ. Ultrasound molecular imaging and its applications in cancer diagnosis and therapy. ACS Sensors. 2022;7(10):2857–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

65. Izadifar Z, Izadifar Z, Chapman D, Babyn P. An introduction to high intensity focused ultrasound: systematic review on principles, devices, and clinical applications. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):460. doi:10.3390/jcm9020460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Koh DM, Papanikolaou N, Bick U, Illing R, Kahn CEJr, Kalpathi-Cramer J, et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in cancer imaging. Commun Med. 2022;2(1):133. doi:10.1038/s43856-022-00199-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Zhang B, Shi H, Wang H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: a critical approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:1779–91. doi:10.2147/jmdh.s410301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Iizuka O, Kanavati F, Kato K, Rambeau M, Arihiro K, Tsuneki M. Deep learning models for histopathological classification of gastric and colonic epithelial tumours. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1504. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58467-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]