Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Determinants of Vaginal Microbiome Stability and Homeostasis

1 Departamento de Psicología Social y de las Organizaciones, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, 28040, Spain

2 Departamento de Microbiología, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, 29071, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Alejandro Borrego-Ruiz. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Human Microbiota: Current Knowledge and Perspectives)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1311-1338. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066108

Received 29 March 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

The vaginal microbiome plays a pivotal role in maintaining vaginal health and protecting the host from various diseases. There is a broad agreement within the scientific community that the vaginal microbiome exhibits stable bacterial diversity, influenced by age and gonadal hormone levels, and is classified into distinct Community-State Types. A healthy vaginal microbiome is typically characterized by a predominance of Lactobacillus spp., which acidifies the vaginal environment and is essential in defending against invading microbial pathogens. This review examines the evolution of the vaginal microbiome’s composition throughout a woman’s life. It also explores how exogenous factors influence the homeostasis of this microbiome, leading to either a state of eubiosis or dysbiosis. The main factors supporting eubiosis of the vaginal microbiome include diet, probiotic intake, certain personal hygiene practices, and hormonal contraceptives, while the major contributors to dysbiosis are psychosocial stress, tobacco smoking, and sexual activity. This state of dysbiosis is strongly associated with a range of adverse vaginal health outcomes, including preterm birth, bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and a higher risk of sexually transmitted infections.Keywords

The term microbiome encompasses the genetic material of the microbiota residing in a human body niche, the microorganisms themselves, their microbial products, and the surrounding environmental conditions [1]. In particular, the vaginal microbiome (VM) constitutes a complex and dynamic ecosystem dominated by commensal, symbiotic, and potentially pathogenic microorganisms that colonize the vaginal mucosa and its lumen. This habitat is strongly associated with the subject’s ethnicity, age, hormone levels, menstruation, behavioral tendencies, dietary patterns, feminine hygiene products, and sexual activity [2].

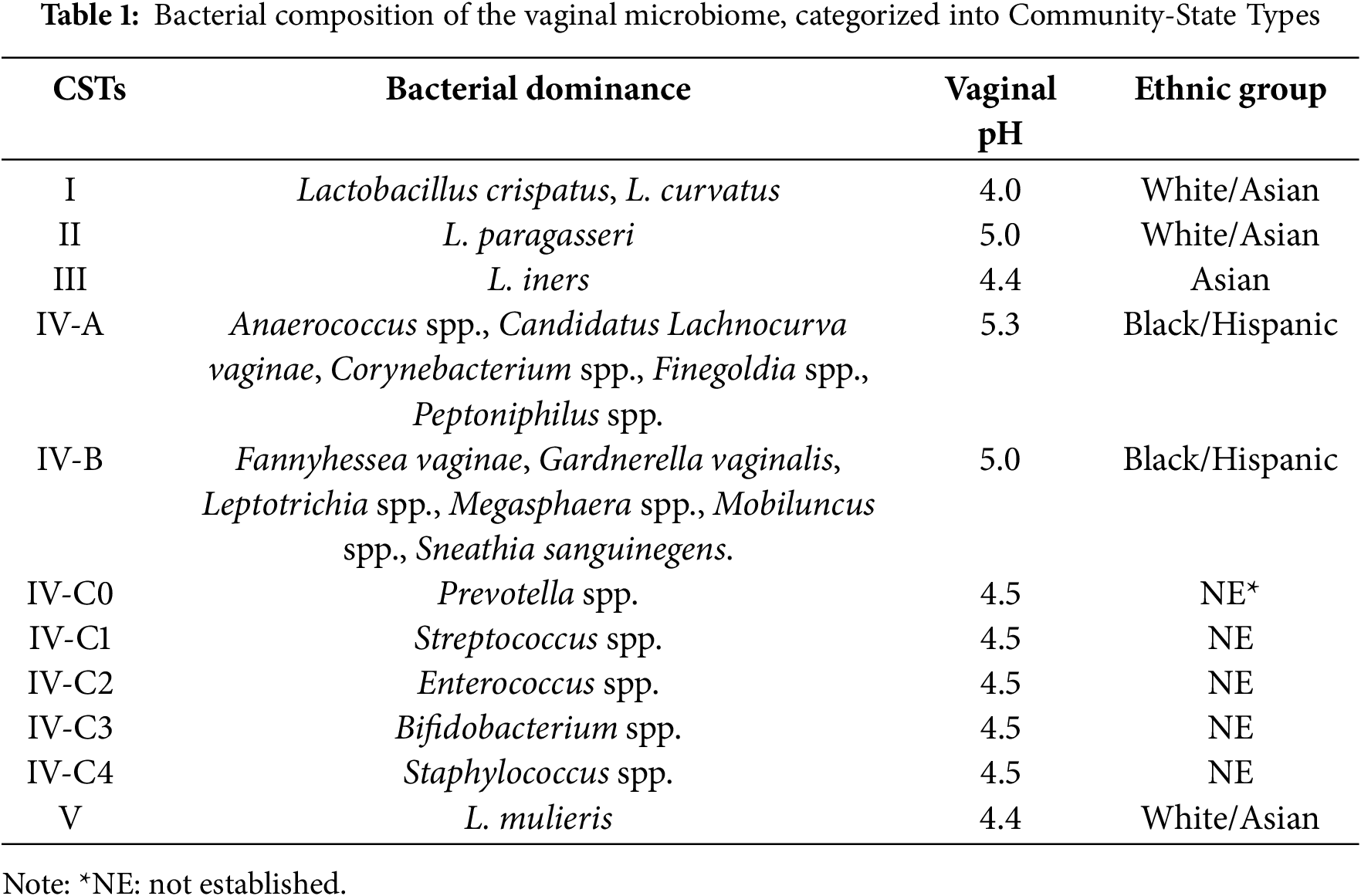

Using molecular sequencing techniques, Ravel et al. [3] studied the vaginal microbiota of asymptomatic, fertile, and non-pregnant North American women from four distinct ethnic backgrounds. They found that the microbiota was grouped into five different Community-State Types (CSTs). Four of these CSTs were predominantly composed of Lactobacillus species: L. crispatus (CST I), L. paragasseri (formerly L. gasseri) (CST II), L. iners (CST III), and L. mulieris (formerly L. jensenii) (CST V). In contrast, CST IV was characterized by a reduced presence of Lactobacillus spp. and an increased abundance of anaerobic microorganisms, such as Mobiluncus spp., Gardnerella spp., Prevotella spp., Leptotrichia spp., Sneathia spp., and Fannyhessea vaginae (formerly Atopobium vaginae). In addition, CST IV was further divided into two subtypes: CST IV-A and IV-B [4]. CST IV-A was predominantly composed of several species of anaerobic bacteria from the genera Anaerococcus, Corynebacterium, Finegoldia, and Peptoniphilus, whereas CST IV-B exhibited a greater abundance of the genera Fannyhessea, Gardnerella, Leptotrichia, Megasphaera, Mobiluncus, and Sneathia. More recently, Shen et al. [5] proposed the inclusion of five sub-groups within CSTs IV: IV-C0, IV-C1, IV-C2, IV-C3, and IV-C4, dominated by Prevotella spp., Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Staphylococcus spp., respectively. Table 1 presents the bacterial composition of the VM, categorized into CSTs ([3–6]).

These bacterial communities are frequently observed in asymptomatic, healthy women, especially in those of Black and Hispanic descent. However, they have also been associated with an elevated Nugent score, a Gram-staining method widely used for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis (BV). A high Nugent score in the vaginal microbiota has been associated with an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, preterm birth, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and postpartum endometritis [2,7]. According to Amsel et al. [8], BV is diagnosed when at least three of the following four signs are present: (i) excessive white vaginal discharge; (ii) a pronounced, unpleasant fishy odor; (iii) vaginal pH exceeding 4.5; and (iv) the presence of “clue cells” in wet-mount preparations. Indeed, this highlights a potential relationship between specific vaginal bacterial compositions and the clinical manifestations of BV.

In the eubiosis state, the VM is dominated by Lactobacillus spp., reaching concentrations of 107–109 per gram of vaginal fluid. These bacteria play a critical role in vaginal health [9] and are present in four of the CSTs (i.e., I, II, III and V). Lactobacillus spp. have the ability to produce hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, and lactic acid, creating an acidic microenvironment based on estrogen availability in the bloodstream, increasing the adherence of these microorganisms to the vaginal epithelium, reducing the potential for growth and colonization of microbial pathogens in this ecosystem, and activating immune mechanisms [9,10]. Although the precise reason for the dominance of Lactobacillus remains unclear, there are several advantages associated with eubiosis. One key benefit of the native microbiome is the concept of competitive exclusion: it adapts to become the most efficient nutrient scavenger in the environment. This competitive ability allows it to outcompete potential pathogens for resources, effectively starving and limiting the growth of harmful invaders [11].

Lactic acid presence is considered essential for maintaining vaginal homeostasis, and its production originate from two main sources: the conversion of glycogen by vaginal epithelial cells, and the microbial degradation of glycogen within the vaginal lumen by alpha-amylases, resulting in alpha-dextrins, maltotriose, and maltose, which are further converted into two isoforms of lactic acid, with a predominance of D-lactic acid [12]. When this ecosystem is perturbed by various intrinsic (e.g., menstrual cycle and pregnancy), and extrinsic factors or stressors (e.g., diet, smoking, antibiotic treatment, stress), the VM composition changes, leading to a dysbiosis state marked by: (i) a decrease in Lactobacillus spp. and an increase in anaerobic bacteria, accompanied by a reduction in microbial diversity; (ii) the production of amino compounds by the altered bacterial microbiota; (iii) an elevation in vaginal pH above 4.5; and (iv) prevalent pathological states such as BV, yeast infections, STDs, and urinary tract infections [13,14]. Furthermore, dysbiosis of the VM triggers inflammatory and abnormal immune responses, which can contribute to a variety of female reproductive health issues [4].

Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone play a crucial role in shaping the composition and abundance of the vaginal microbiota, with these effects beginning at puberty and continuing throughout the reproductive lifespan [5]. Estrogen stimulates the proliferation of vaginal epithelial cells and enhances glycogen storage, whereas progesterone induces the lysis of these cells, promoting glycogen release. Glycogen fermentation by Lactobacillus spp. is the major source of the lactic acid and acid pH present in the vaginal ecosystem [15]. Thus, given the significant impact of hormonal fluctuations on vaginal health, understanding their role in microbiome composition is essential. For this reason, the present narrative review addresses the changes in the VM composition as a function of age and sex hormone levels. In addition, it also examines the factors affecting the risk of homeostasis and dysbiosis, such as ethnicity, diet, probiotics, tobacco smoking, antimicrobial therapy, psychosocial stress, hygiene practices, contraceptive use, and sexual activity.

The present review consists of a non-systematic, narrative approach [16], aiming to assess the existing literature on the VM and the primary factors influencing the risk of dysbiosis. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the current state of research, the data were gathered from a range of scientific studies related to the topic. The data collection process involved searching through PubMed and Scopus databases, with no restrictions on publication dates, ensuring access to a wide range of articles. No language limitations were imposed, although the search keywords were limited to English terms. For the search, relevant terms related to the subject were used, along with Boolean operators. In addition, reference lists from prior studies were reviewed to identify additional articles of potential relevance. The selection process began with an initial retrieval based on predefined criteria. Each article underwent a two-step screening process: first, titles and abstracts were assessed, and studies not directly aligned with the research focus were excluded; second, full-text evaluations were performed to confirm the studies’ relevance to the established objectives. Inclusion criteria were based on whether the articles examined the VM composition across the life cycle, explored related physiological factors, and assessed risk factors impacting VM eubiosis and dysbiosis. Exclusion criteria included articles on metabolic diseases, opinion articles, theses, proceedings, and studies lacking sufficient relevant data. Searches and data extraction were conducted between November and December 2024. Articles not meeting the established criteria or deemed irrelevant were excluded, and only studies that provided significant findings directly related to the review’s objectives were retained.

3 Changes in Vaginal Microbial Composition throughout a Woman’s Life Cycle

There is broad agreement within the scientific community that the composition of the VM undergoes important fluctuations during several stages of a woman’s life, including birth, puberty, reproductive years, and menopause. In this regard, steroid sex hormones are essential in regulating the composition and stability of this microbiota during these periods. In addition, dietary intake has been shown to influence the composition of the VM in young females. Lower concentrations of certain essential nutrients, such as vitamins A, C, and E, β-carotene, and iron, may contribute to the risk of several microbial pathologies, such as BV or candidiasis. Moreover, elevated plasma glucose levels, dietary fat, and obesity are linked to poorer vaginal health and to a dysbiotic state [2].

3.1 Vaginal Microbiome at Birth

Several bacterial species, including coagulase-negative staphylococci, Mycoplasma spp., Escherichia coli, and Corynebacterium spp., constitute the VM in early childhood [10]. However, the presence of these microorganisms depends on the occurrence of vaginal infections during pregnancy, which may ultimately contribute to the onset of preterm labor [17]. For example, the presence of Burkholderia and L. iners in VM has been found related to preterm birth [18], whereas the presence of F. vaginae and Leptotrichia spp. is often associated with a dysbiotic state [17]. In neonates, the VM is primarily impacted by the presence of transplacental estrogens, which supply glycogen. Thus, the abrupt cessation of transplacental estrogens has been shown to reduce the vaginal glycogen content, leading to a neutralized or alkalized vaginal pH [19]. During childhood and the prepubertal stages, vaginal pH is influenced by the consistent presence of aerobic, strictly anaerobic, and enteric bacterial species. Conversely, throughout these stages, Lactobacillus spp. are only sporadically present [17].

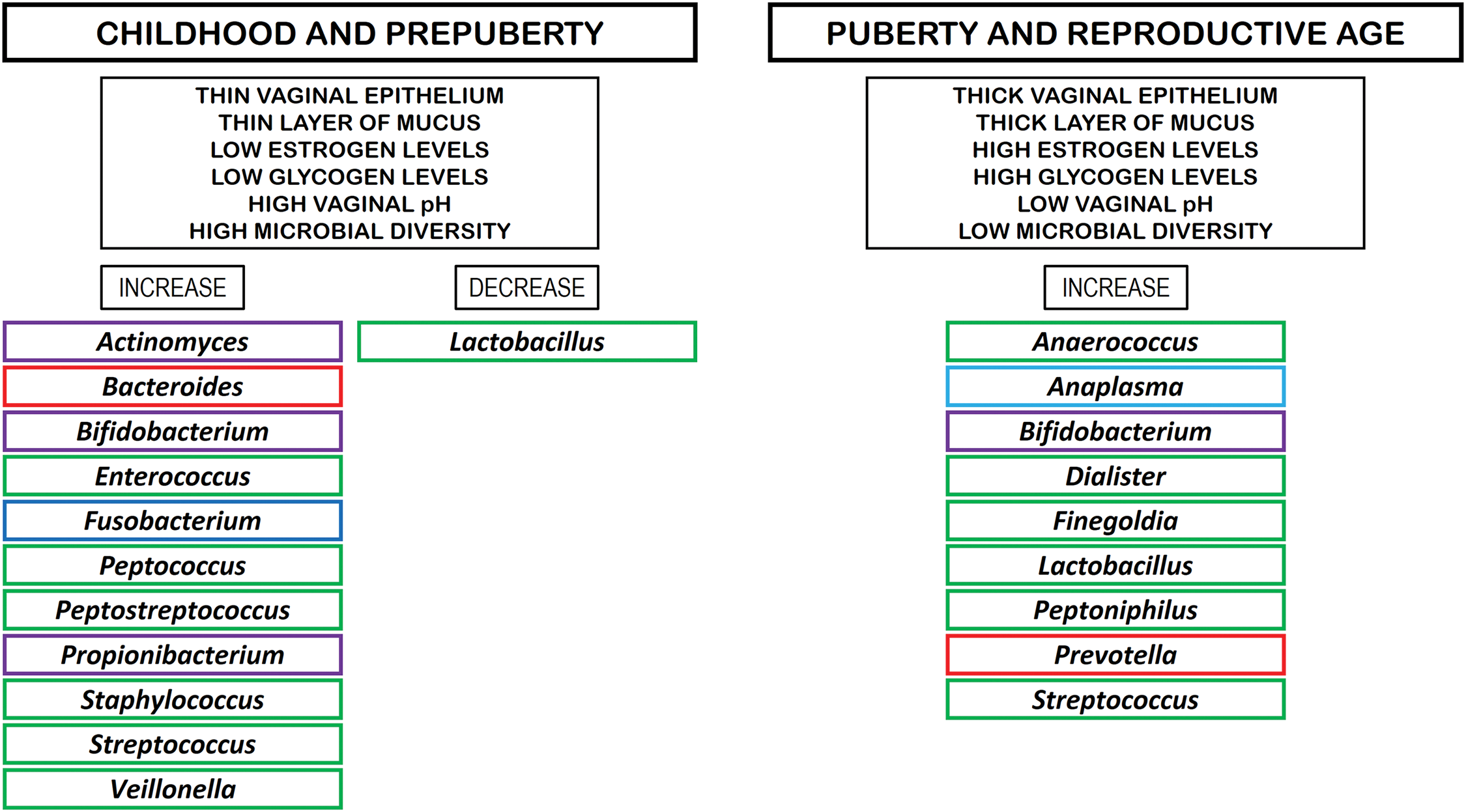

Adolescence marks a period of rapid development, where females undergo significant transformations from childhood to sexual maturity. This phase encompasses gradual changes in physical, psychological, endocrine, and reproductive aspects [5]. Later, the onset of puberty induces an increase in estrogen and progesterone levels with VM remodeling, which favors Lactobacillus spp. colonization throughout the reproductive years of women. In several research cohorts, the VM was found to be dominated by several bacterial taxa, such as the genera Anaplasma (phylum Pseudomonadota), Prevotella (phylum Bacteroidota), Anaerococcus, Dialister, Finegoldia, Lactobacillus, Peptoniphilus, and Streptococcus (phylum Bacillota), and Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinomycetota) [20]. Although Gardnerella is present in the VM of adolescent females, it has been suggested that it is transmitted by sexual activity from the infected partner [21].

Throughout reproductive age, the VM is exposed to high levels of estrogen and progesterone, resulting in a decrease in pH to less than 4.5, which in turn can limit the proliferation of numerous pathogens and may even lead to alterations in structure, such as thickening of the vaginal epithelium [12,22]. In addition, estrogens promote hyperplasia of the vaginal mucosal epithelium, which allows adhesion, colonization and growth of Lactobacillus species [12,22]. During this period, other bacterial taxa can be found in the VM, mainly anaerobes of the CSTs IV. In women of reproductive age, the VM harbors the bacterial communities listed in Table 1. To further complicate the heterogeneity of the VM, various studies have also considered the woman’s ethnicity as a potential confounding variable, thereby leading to divergent conclusions regarding the specificity of CSTs by ethnic groups [23]. As a result, it is plausible to assert that the composition of the VM might be more influenced by genetic and immunological factors than by social or behavioral patterns.

Menstruation leads to the interplay between menstrual blood and vaginal environment, which neutralizes the normally acidic vaginal pH within the lumen. This shift in pH promotes a notable elevation in the population of anaerobic commensal microorganisms, increasing the VM diversity [20]. Furthermore, during this period, iron from the heme in damaged blood cells serves as a main nutrient source for diverse bacteria [24]. Vaginal microbes such as Gardnerella and Streptococcus produce iron chelator complexes, known as siderophores, to acquire iron deposited on the vaginal mucosal surface [5]. This, in turn, allows for the rapid growth of these microorganisms. However, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, an effector of the vaginal local immune system, prevents the proliferation of iron-reliant bacteria by hindering iron accumulation [25]. In vaginal microecosystems where Lactobacillus spp. predominate, intravaginal neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin concentrations are higher, controlling the colonization of these anaerobic bacterial taxa. As the menstrual phase shifts to the follicular phase, sex hormone levels rise gradually, prompting the vaginal epithelial cells to thicken and secrete increased glycogen. This glycogen is subsequently broken down into lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, leading to a decrease in vaginal pH and promoting the growth of Lactobacillus spp., while simultaneously diminishing both the quantity and diversity of other anaerobic bacteria [12].

During the pregnancy period, female physiology undergoes substantial changes at the endocrine, immunological, and metabolic levels. These physiological alterations are related to shifts in the structure, composition, and abundance of microbial communities of different human microbiomes [26]. In the specific case of VM, menstruation ceases, and there are consistently elevated levels of estrogen with a concomitant increase in Lactobacillus spp. dominance [26]. Thus, pregnancy reshapes the VM, acquiring greater stability and reduced diversity, with Lactobacillus species becoming dominant early in pregnancy. A longitudinal study conducted on pregnant British women reported the following distribution of CSTs in VM: CST I (L. crispatus) was found in 40% of subjects, CST III (L. iners) in 27%, CST V (L. mulieris) in 13%, CST II (L. paragasseri) in 9%, and CST IV, characterized by decreased lactobacilli and increased numbers of BV-associated bacterial species, in 8% of subjects [27]. Similar patterns have been observed in a study conducted in the United States, where Lactobacillus species (CST I, II, III, and V) dominated the VM of White and Asian women during pregnancy, while CST IV was more prevalent in the vaginal microbiota of Black and Hispanic women [28]. In contrast, another study of a Mexican population showed differences in CST composition compared to American and European women, with L. acidophilus being isolated from 78% of pregnant Mexican women, whereas L. iners, L. paragasseri, and L. delbrueckii were isolated in lower percentages (54%, 20%, and 6%, respectively) [29].

Multiple studies have indicated a link between dysregulated microbiota and preterm birth [30,31]. Preterm premature rupture of membranes has also been associated with changes in the VM [32]. L. iners was identified as the predominant species related to preterm birth in pregnant women; however, until 2014, the placenta was thought not to contain its own microbiome [30]. In chorioamnionitis, an inflammatory infection affecting the fetal side of the placenta, the most frequently identified pathogens include Bacteroides spp., Escherichia coli, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Peptostreptococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., and Ureaplasma urealyticum [33], suggesting that bacterial pathogens may ascend from the vagina to invade the amnion and chorion [34]. In this sense, some studies have reported that variations in VM at the Lactobacillus spp. level are linked to preterm birth [35]. To safeguard the developing fetus and accommodate the physiological alterations that occur, the immune system undergoes adaptive regulation. Pregnancy necessitates immunological resistance for successful reproduction, as the fetus derives genetic material from two distinct parents [36,37]. During this period, processes such as immunological tolerance, endometrial initiation, and embryo implantation take place, accompanied by an increase in VM diversity and a decrease in Lactobacillus spp. levels [11]. Fig. 1 shows the microbial composition of the VM within the period between childhood and reproductive age [2,13,38,39].

Figure 1: Microbial composition of the VM within the period between childhood and reproductive age. Rectangles in violet color: phylum Actinomycetota. Rectangles in red color: phylum Bacteroidota. Rectangles in green color: phylum Bacillota. Rectangles in dark blue color: phylum Fusobacteriota. Rectangles in light blue color: phylum Pseudomonadota

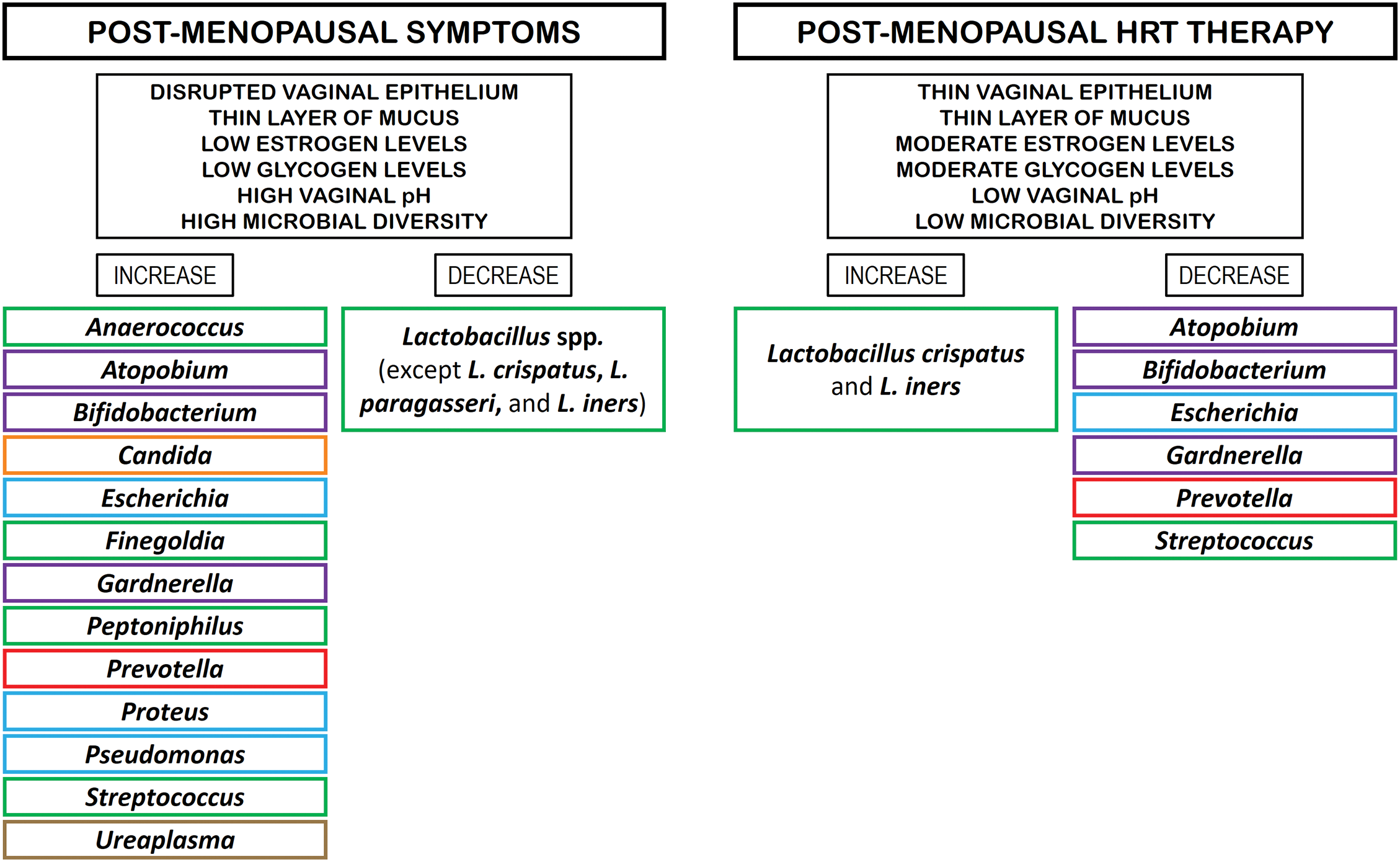

Menopause typically occurs in a woman’s fourth or fifth decade of life and is characterized by the cessation of menstruation for 12 consecutive months, signifying the end of the reproductive phase. Reduced ovarian function during menopause leads to lower circulating estrogen levels and elevated follicle-stimulating hormone levels [40], often resulting in symptoms such as cognitive decline, night sweats, mood fluctuations, and hot flashes that women usually experience in the years leading up to and during menopause [41]. Moreover, changes in the genitourinary tract related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) or the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) are prevalent, affecting 25%–50% of women in menopause [42]. The primary manifestations of VVA/GSM encompass genital symptoms (such as itching, burning, dryness, irritation, and bleeding), sexual symptoms (including dyspareunia and other forms of sexual dysfunction), and urinary symptoms (such as dysuria, as well as increased frequency, urgency, and recurrent urinary tract infections) [42]. Interestingly, Mitchell et al. [43] reported that the severity of vaginal symptoms post-menopause was not significantly linked to the vaginal microbiota or mucosal inflammatory markers.

The deterioration of estrogen excretion could have a detrimental effect on the vaginal mucosa, resulting in decreased glycogen levels, vaginal atrophy, and changes in the species composition of the VM [42]. This is often manifested by decreased lactobacilli abundance and lactic acid production, leading to an elevated vaginal pH [44], potentially making the vagina more susceptible to infection and exacerbating the vaginal symptoms related to VVA/GSM [38]. In a pilot cross-sectional study, Gliniewicz et al. [44] compared the VMs of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. The VMs of these women were classified into six distinct clusters (A–F) based on variations in the composition and relative abundance of bacterial taxa. Cluster A was predominantly dominated by L. crispatus, while cluster B showed a predominance of G. vaginalis. Communities within cluster C exhibited a high abundance of L. iners, whereas cluster D comprised a variety of co-dominant taxa. Lastly, clusters E and F were primarily dominated by Bifidobacterium spp. and L. paragasseri, respectively. However, other studies have reported conflicting results. For example, Fettweis et al. [45] found that lactobacilli were found in 49% of women, Prevotella bivia was identified in 33%, G. vaginalis in 27%, Ureaplasma urealyticum in 13%, and Candida albicans in 1%. Later, Kim et al. [46] analyzed the vaginal fluids of 11 premenopausal and 19 postmenopausal women in Korea and found that bacterial species richness was substantially decreased, but species diversity was significantly increased in postmenopausal women, with a reduction in the abundance of the genus Lactobacillus and an increase in the genera Prevotella, Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Proteus, Finegoldia, and Fannyhessea. Furthermore, Shen et al. [5] noted that the postmenopausal stage was dominated by the genera Aspergillus and Anaplasma, and by members of the phylum Actinomycetota. Additionally, Zeng et al. [47] found an abundance of the bacterial genera Escherichia-Shigella, Anaerococcus, Finegoldia, Enterococcus, Peptoniphilus, and Streptococcus in the VM of postmenopausal women.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is considered the most effective approach for treating menopausal symptoms resulting from estrogen withdrawal. HRT includes a range of sex hormone preparations (estrogen alone or in combination with progestogen) that can be delivered via different routes, including oral, transdermal, intramuscular, intranasal, subcutaneous, or vaginal administration [48]. Many postmenopausal women are treated with HRT, which may affect their VM. For example, a study of estrogen therapy for three months, found that vaginal swabs showed a dominance of L. iners and L. crispatus in the VM of 19 hormone-treated women [49]. Interestingly, the overall prevalence of BV was reported to be lower in postmenopausal women (6.0%) compared to fertile (9.8%) and perimenopausal (11%) women [50]. Among the postmenopausal women studied, the incidence of BV in women without HRT was 6.4%, whereas 5.4% of those treated with HRT were found to be positive for BV [50], suggesting that the return of Lactobacillus species microbial diversity to premenopausal levels following HRT does not increase the prevalence of BV in postmenopausal women. Although HRT has been shown to have benefits in menopausal women, including the symptoms of VVA/GSM [51], HRT is contraindicated in certain women, including those with active liver disease, established coronary artery disease, a history of breast cancer, or previous venous thromboembolic events or strokes [52]. In addition, potential side effects of HRT include venous thrombosis, stroke, breast cancer, gallstones, and dementia [50]. Fig. 2 shows the microbial composition of the VM in post-menopausal women without and with HRT [2,13,38,39].

Figure 2: Microbial composition of VM in post-menopausal women without and with HRT. Rectangles in green color: phylum Bacillota. Rectangles in violet color: phylum Actinomycetota. Rectangles in orange color: phylum Ascomycota. Rectangles in light blue color: phylum Pseudomonadota. Rectangles in brown color: phylum Mycoplasmatota

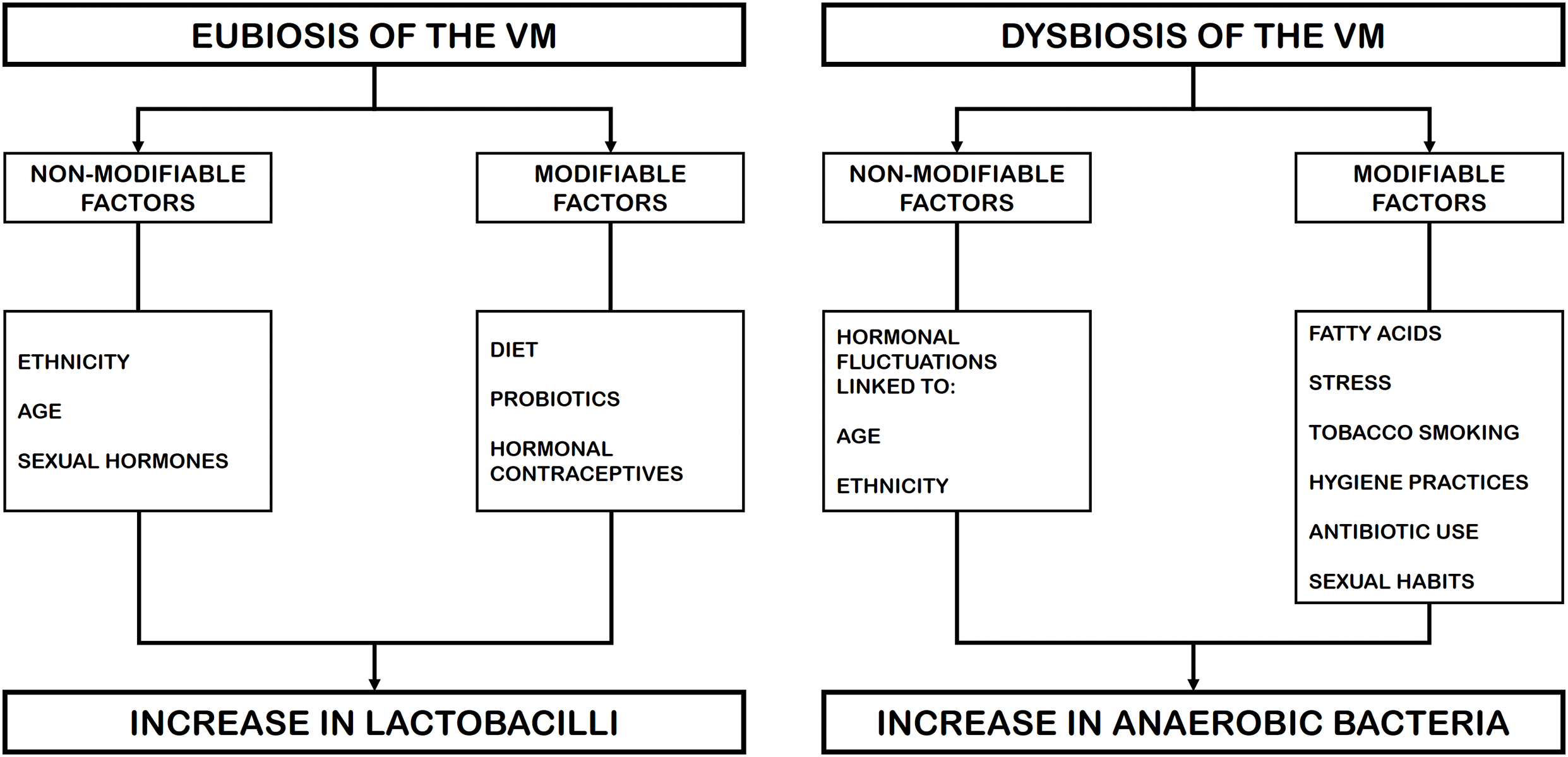

4 Factors Associated with Vaginal Microbiome Dysbiosis

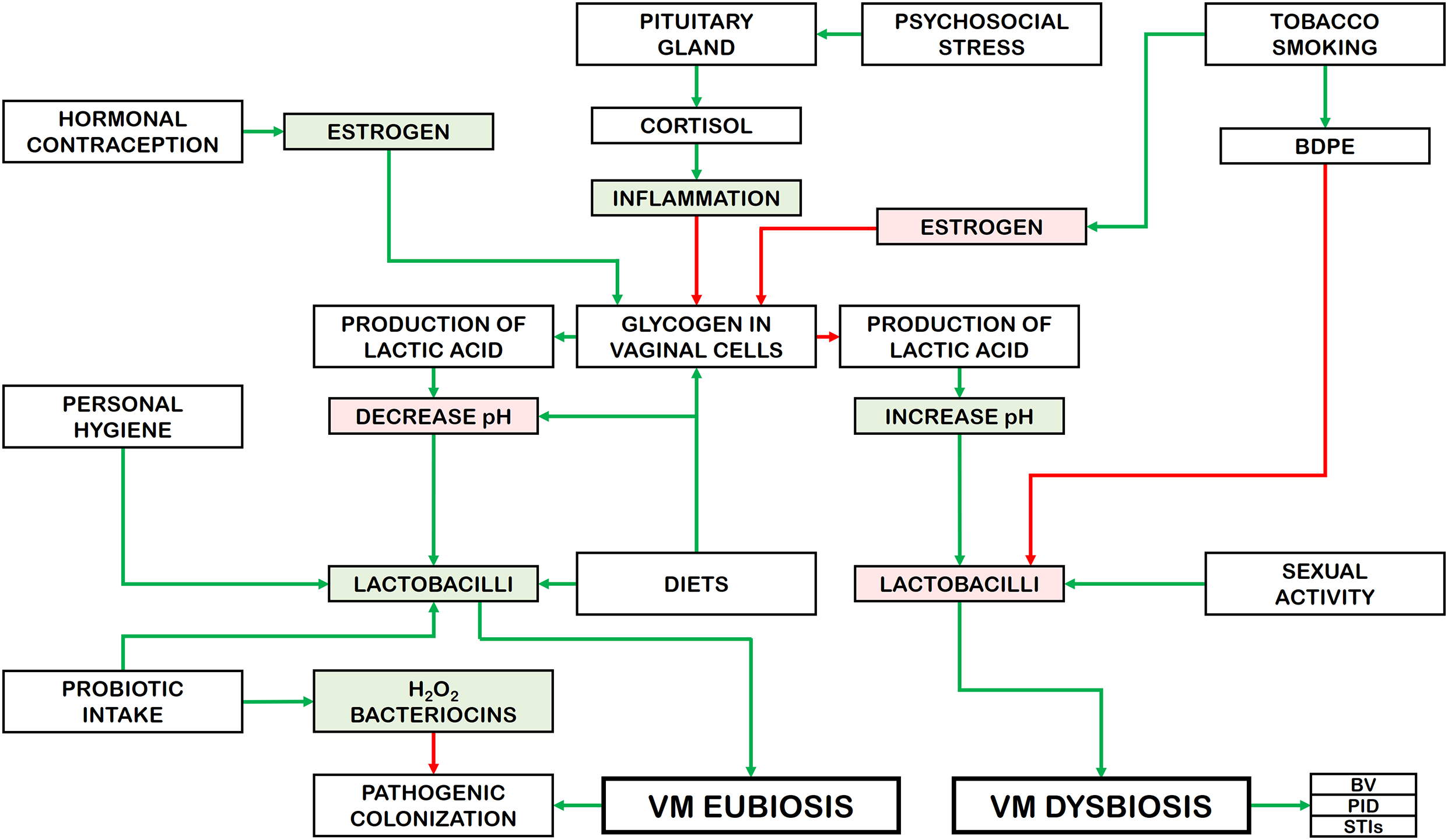

The risk factors affecting VM can be divided into two groups: (i) those that are inherent to the human condition or non-modifiable factors, such as age, hormonal levels, and ethnicity, which are related to the eubiosis or dysbiosis of the VM; and (ii) those related to environmental or social components, referred to as modifiable factors, such as diet, probiotic intake, tobacco smoking, stress, antibiotic use, hygiene practices, contraceptive use, and sexual habits, which are currently associated with VM dysbiosis [2,13,39,53]. In this regard, microbiome dysbiosis is currently defined as a decrease in microbial diversity, which represents an absence of beneficial microorganisms or the presence of potentially harmful microorganisms [54]. Fig. 3 shows the modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors affecting vaginal microbiome homeostasis [2,13,39,53].

Figure 3: Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors associated with vaginal homeostasis or dysbiosis

Research conducted on Japanese and North American women indicates that their VM is predominantly colonized by one or more Lactobacillus species [55,56]. In contrast, studies on African American women reveal a more diverse microbial composition with lower lactobacilli concentrations [45]. Notably, the Lactobacillus-depleted CST IV profile appears more frequently in Black women than in Caucasian women [45,57]. Ravel et al. [3] found substantial variations in CST distribution among four ethnic groups of North American women (Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White). Their findings suggest that Asian and White women exhibit a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs (I, II, III, and V), whereas Black and Hispanic women more commonly present CST IV, characterized by a dominance of anaerobic bacteria. However, the study does not clarify potential ethnic variations within the cohorts, which may have influenced these findings.

Various divergences in VM have been observed between Belgian and Canadian women, with L. crispatus. L. iners and Prevotella predominant in the Belgian population [58], and L. iners, L. mulieris, and G. vaginalis in the Canadian population [59]. In addition, in a study of African women (Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, and Tanzania), Gautam et al. [60] found that VM was divided into five clusters: one cluster that was dominated by L. crispatus and L. iners, and three clusters that were not dominated by a single species but contained several anaerobes, mainly G. vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Fannyhessea spp., and Dialister spp. Similar results were reported in a study conducted on 62 Black South African women of reproductive age [61], which characterized three VM profiles: the first dominated by L. iners, the second by unclassified Lactobacillus spp., and the third by a variety of bacterial species, some of them BV-associated, including Prevotella, Gardnerella, Sneathia, and Shuttleworthia.

Interestingly, Borgdorff et al. [62] investigated the VM of resident young women (16–34 years old) living in the Netherlands, belonging to the six more prevalent ethnic groups (African Surinamese, Asian Surinamese, Dutch, Ghanaian, Moroccan, and South Turkish). The authors found that more than 38% of the individuals presented a VM that was not dominated by lactobacilli. The African Ghanaian ethnicity was linked to a polybacterial VM containing G. vaginalis, and the African Surinamese ethnicity to a VM dominated by L. iners, in contrast to the predominant VM observed in ethnically Dutch women, which was L. crispatus.

All these findings suggest that host genetic factors, particularly those related to innate and adaptive immunity, may play a more significant role in determining VM composition than cultural or behavioral differences among ethnic groups. Nevertheless, since dietary habits and hygiene practices also vary across cultures and ethnicities, VM composition is likely shaped by a complex interplay of multiple factors.

Studies on VM have shown that inadequate consumption of essential micronutrients, including β-carotene, vitamins A, C, D, E, calcium, and folate, may elevate the risk of BV [63]. Additionally, research suggests that higher carbohydrate consumption could promote lactobacilli proliferation in the vagina by raising free glycogen levels, which are metabolized to lactic acid and produce an acidic vaginal pH [64]. However, high glycemic index carbohydrates have also been linked to an increased risk of BV, a condition typically characterized by a reduced abundance of Lactobacillus species [65]. Notably, a recent investigation by Song et al. [64] revealed that vegetarian women exhibited greater overall vaginal microbial diversity compared to their non-vegetarian counterparts. With regard to fats, the study conducted by Neggers et al. [66] identified a correlation between high dietary fat consumption and elevated risk of BV, whereas greater intake of micronutrients such as calcium, folate, and vitamin E appeared to mitigate the likelihood of severe BV. Furthermore, diets rich in betaine have been linked to a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus spp. in the vaginal microbiota [67]. Obesity-induced dysregulation of immune, metabolic, and hormonal pathways may also contribute to alterations in the vaginal ecosystem [68]. Moreover, obesity is linked to gut microbiota dysbiosis, which could serve as an external reservoir for vaginal bacteria, thereby influencing VM composition [69]. In addition, obesity significantly increases VM diversity regarding Prevotella, an anaerobic microorganism commonly detected in BV-positive individuals [70]. Recently, Dall’Asta et al. [71] reported that both pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and dietary habits have an adverse impact on vaginal health. Their findings suggest that women who are overweight or obese at the beginning of pregnancy present a higher incidence of vaginal dysbiosis during gestation. Interestingly, a VM dominated by lactobacilli was less prevalent in individuals with higher pre-pregnancy consumption of animal protein. In contrast, greater intake of total sugars and carbohydrates prior to pregnancy appeared to confer a protective effect on vaginal health.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, provide health benefits to the host [72]. Several members of the family Lactobacillaceae including several genera (e.g., Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Lactiplantibacillus, Levilactobacillus, Ligilactobacillus, Limosilactobacillus, and Apilactobacillus) used as probiotics, have shown a beneficial role in VM homeostasis, mainly in reducing the risk of vaginal infections in premenopausal and menopausal women [39,73] or for the treatment of BV and vulvovaginal candidiasis [74,75]. Probiotics can positively influence the vaginal environment through various mechanisms, including (i) their ability to selectively adhere to epithelial cells, and (ii) their production of bioactive compounds with antimicrobial properties, such as hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid that lowers vaginal pH, and bacteriocins [39,76]. Nevertheless, the route of administration of probiotics is a crucial aspect: vaginal applications (vaginal capsules or suppositories) deliver probiotics directly to the site of action, while orally administered probiotics must first navigate the gastrointestinal tract before colonizing the vaginal environment [77]. In this regard, oral probiotics may contribute to vaginal health through the “gut-vagina axis”, a mechanism by which they help regulate gut microbiota, hinder the translocation of urogenital pathogens from the rectum to the vagina, and enhance both gut and systemic immune responses [39].

Additionally, probiotics can contribute to vaginal microbial balance by secreting antimicrobial compounds and modulating immune responses [9,39]. The vaginal mucosal immune system plays a crucial role in both shaping and regulating VM composition [78]. This intricate interaction involves various factors, including epithelial and immune cells (e.g., dendritic cells), antimicrobial peptides, inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, and secretory antibodies [79]. Under normal conditions, the presence of endogenous lactobacilli prompts epithelial cells to produce minimal amounts of antimicrobial peptides and cytokines, thereby maintaining mucosal equilibrium. However, a marked increase in antimicrobial peptides and pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines is observed when lactobacilli are depleted, resulting in a disruption of the homeostatic balance [79].

Studies investigating the impact of cigarette smoking on VM have shown a strong correlation between smoking and an increased prevalence of BV, as well as a heightened risk of preterm birth [80,81]. Payne et al. [82] examined the VM of pregnant women to assess the presence of Candida, Mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma, microorganisms linked to preterm birth. They observed that smoking substantially heightened the likelihood of detecting all three microbial genera. Specifically, these authors reported that 50% of smokers had a higher vaginal pH and a VM dominated by CST IV compared to 15% of non-smokers. One potential explanation for the reduced abundance of Lactobacillus in smokers is the presence of benzopyrene diol epoxide, a compound found in cigarette smoke, which has been detected in the vaginal secretions of smokers and has been implicated in bacteriophage induction in the vaginal ecosystem [83]. In addition, smoking exerts anti-estrogenic effects, which may hinder the growth of Lactobacillus spp. in the vaginal environment [80]. Nelson et al. [84] did a comparison between the vaginal metabolomes of smokers and non-smokers, noting that nicotine, along with its metabolites (cotinine and hydroxycotinine), was present at significantly higher levels in the vaginal metabolomes of smokers. In this respect, the smokers with VM rich in CST IV have substantially greater concentrations of bioamines, which are regarded to affect the virulence of pathogens that predispose women to vaginal infections, thereby contributing to vaginal malodor.

The most important factors influencing the composition of the VM are antibiotics and antifungals aimed at treating vaginal microbial infections. Concerning the endogenous Lactobacillus populations, various studies suggest that the application of clindamycin and metronizadole does not have a notable impact on the overall colonization of Lactobacillus spp. in the vagina [85,86]. Furthermore, among women diagnosed with BV, several studies indicate that VM appears to revert within days of metronidazole treatment [87,88] and that L. iners is the predominant species during the recovery phase as the VM returns to homeostasis [87–89]. However, several vaginal pathogenic microorganisms are resistant to antimicrobials and can form a microbial biofilm, which may be a critical factor in pathogen recurrence and persistence [90]. In the case of vulvovaginal candidiasis, the hyphal (mycelial) forms of Candida spp. contribute to adherence and mucosal invasion, which are characteristic of symptomatic disease [91]. This biofilm confers increased virulence, as well as resistance to the host immune responses and antimicrobial agents, leading to recurrent candidiasis and reduced efficiency of antifungal treatments [14].

Elevated levels of perceived stress can influence the function of the immune system, potentially heightening vulnerability to infections and altering the composition of the VM [92]. This alteration of the VM may result from the presence of biogenic amines and pro-inflammatory responses, which can interfere with vaginal physiology [53]. Biogenic amines are generated through the decarboxylation of amino acids, a process that consumes hydrogen ions and leads to an increase in vaginal pH. This shift disrupts the balance of the vaginal microbiota, particularly affecting Lactobacillus populations. As a result, women experiencing psychosocial stress may have a greater colonization by a more diverse bacterial community in the vagina [93]. In preclinical studies, it has been noted that prolonged exposure to psychosocial stress can result in stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axes, with the release of adrenal corticotropic hormone, leading to a pro-inflammatory response and cortisol secretion from the adrenal cortex, mechanisms that suppress immune defense [92,94]. Cytokines, which are polypeptide mediators involved in immunity and inflammation, also function as neurotransmitters within the central nervous system during periods of stress, thereby influencing immune responses [53]. In addition, the disruption of epithelial cells during the inflammatory process triggered by pH shifts impedes the deposition of vaginal glycogen, thus limiting the available carbon source, which constitutes a crucial nutrient source for lactobacilli growth and further colonization of the vaginal ecosystem [15].

Culhane et al. [95] conducted a study involving 454 pregnant women and found that chronic stress was a significant, independent risk factor for BV. Women experiencing moderate and high levels of stress were 2.3 and 2.2 times more likely to develop BV, respectively, compared to those in the low-stress group. These results were confirmed in a longitudinal study on non-pregnant individuals [96]. Another study examining the relationship between chronic stress and BV in pregnant women revealed that Black women had significantly higher rates of BV in comparison to White women [97]. Moreover, Black women were more likely to experience chronic stressors both personally and within their communities, which likely accounts for a substantial portion of the ethnic disparities observed in BV prevalence.

An association between the presence of CST IV and both life trauma and self-esteem issues has been found among American Indian women experiencing high levels of perceived stress. This suggests that stressful situations may play a role in linking CST IV with the development of BV in this population [98]. Another study has confirmed the link between psychosocial stress and the change in VM [99], as an increase in stress score was significantly associated with the transition from CST III (dominated by L. iners) to CST IV. In addition, psychosocial stress has been shown to be a key aspect impacting the composition of VM in more than 80% of women of African or African American origin [98].

The vagina possesses a natural self-cleaning capacity, with vaginal discharge serving as a mixture of desquamated epithelial cells, bacteria, and glandular secretions [13]. The characteristics of vaginal discharge fluctuate along the menstrual cycle. In the early phase, the discharge is typically sticky, thick, and sperm-resistant, whereas during ovulation, it becomes thinner and more watery as a result of elevated estrogen levels [100]. For certain women, vaginal discharge can be uncomfortable, prompting the use of feminine hygiene products and practices aimed at eliminating both discharge and odor from the genital area. However, the short- and long-term health impacts of these practices remain poorly understood [101]. The type and frequency of use of such practices (e.g., vaginal washing and douching, wipes, oils, moisturizers, and sprays) can vary and may be influenced by personal preferences as well as cultural, societal, and religious factors [101–103].

Research indicates that the employment of feminine hygiene products may create a harmful cycle in which women wash to alleviate perceived discharge, itching, and odor, only to experience more severe or additional symptoms, as a result of the increased washing and the associated disruption of normal VM [104]. The use of feminine hygiene products and practices by women to clean the genital area and eliminate vaginal discharge, as well as to treat STDs, is prevalent, especially among Asian and African women [105]. Nevertheless, these practices have been associated with negative vaginal health outcomes [13]. The extensive use of such products underscores the importance of enhancing education on female intimate hygiene [106].

Vaginal douching has been associated with BV [107], pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) [108,109], preterm birth [110,111], and reduced fertility [107,112]. Douching remains common in American and African countries for general hygiene, to prevent or address odor and infections, as well as after sexual activity and menstruation [113,114]. Nevertheless, it is pivotal to highlight that some studies have found no significant correlations [115,116]. Van Der Veer et al. [117] found that vaginal douching did not significantly alter vaginal pH or the VM composition, whereas menstruation was identified as a key factor influencing VM changes, particularly by increasing the prevalence of anaerobes typically linked to BV. Similarly, douching during menstruation was associated with a higher risk of dysbiosis and a greater likelihood of Candida albicans infections, possibly due to the proinflammatory effects on the vaginal immune response. In a more recent study involving 33 sexually active women, it was reported that discontinuing douching alone did not lead to alterations in the VM or an increased incidence of BV. In turn, other external factors such as diet, antibiotic use, condom use, lubricants, and smoking cessation may play a more important role in modifying the VM [118].

In addition to douching, women employ various other feminine hygiene products and practices to cleanse the genital area, aiming to eliminate excess urine, sweat, odor, and discharge [101–103]. The use of feminine hygiene products has been associated with a threefold increase in the likelihood of experiencing adverse health outcomes, including BV, urinary tract infections, and STDs. This is because these products can decrease the relative abundance of Lactobacillus spp. and induce VM dysbiosis [101]. Fashemi et al. [119] investigated the effects of a vaginal moisturizer (Vagisil), lubricant, nonoxynol-9, and douche on the growth of L. crispatus in vitro. After two hours, both nonoxynol-9 and Vagisil inhibited Lactobacillus growth, and after 24 h, they were completely bactericidal. The lubricant also demonstrated bactericidal effects within 24 h, while the douche had no significant impact on bacterial growth. Similarly, Sabo et al. [104] explored the relationship between vaginal washing and vaginal bacterial concentrations in Kenyan and USA women. Their findings revealed that vaginal washing significantly increased the likelihood of detecting BVAB-1 and 2 (BVAB-1 Clostridiales genomosp. BVAB-1, and BVAB-2 Oscillospiraceae bacterium strain CHIC02), F. vaginae, G. vaginalis, and Megasphaera spp.

Contraceptive methods include several procedures that focus on preventing unintended pregnancy and can be used by both men and women. A 2019 United Nations report estimated that around 407 million women globally rely on hormonal contraception. Among them, 17% use intrauterine devices, 16% take oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), 8% opt for injectable contraceptives, and 2% utilize implants [120]. In addition, a non-hormonal contraceptive pill for men has recently advanced to clinical trials, expanding the traditionally limited male contraceptive options, which have largely relied on condoms and vasectomy. Conversely, women have access to a broader range of contraceptive methods, including mechanical, hormonal, reversible, and permanent options. Although each approach presents distinct advantages and potential risks, research on the impact of contraceptives on the VM is lacking [121].

Mechanical contraception constitutes a barrier method that includes the use of a cervical cap, diaphragm, male and female condoms, and spermicide, all of which act by creating a physical barrier that prevents sperm from reaching the ovum. Condoms, typically made of latex, can be used alongside lubricants or spermicides to enhance their efficacy. Research has indicated that individuals who use condoms tend to have a higher prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species [122] and are less likely to exhibit a non-optimal CST III microbiome dominated by L. iners [123]. However, condom use has been associated with inflammatory processes in adolescent girls, but without substantial alterations in the overall composition of the VM [124]. In adults, the use of condoms has been linked to allergic reactions, vaginal dermatitis, and irritant vulvovaginitis, as well as increased inflammation. These effects are likely attributed to the latex material or the presence of spermicide, which is commonly applied as a coating on certain condoms [121]. Diaphragms and cervical caps act as mechanical barriers by covering the cervix and necessitate the use of spermicides. Classic studies on the topic have noted that these contraceptive methods can provoke an alteration of the regular VM, leading to an increased prevalence of Enterococcus spp. and E. coli [125]. Nevertheless, the negative effect of these devices on VM alteration may be due to the co-use of spermicides. These substances are used to eliminate sperm or to prevent its passage into the cervix. Several studies have shown that nonoxynol-9 (the most commonly used spermicide) induces changes in VM that result in the removal of lactobacilli, alteration of the vaginal epithelium, and thus predisposition of the vagina to colonization by pathogenic bacteria and viruses [121,126]. Other spermicides, such as cellulose sulfate, effectively prevent sperm penetration into cervical mucus but increase mucosal inflammation and the risk of HIV acquisition [127]. More recently, a new spermicide called Phexxi has been used by its effect on the acidic pH that disrupts sperm. However, this causes an alteration in VM, similar to that caused by yeast and urinary tract infections [128].

Hormonal contraceptives are the most widely used methods by women worldwide. They consist of a synthetic form of progestin, sometimes combined with estrogen, which prevents ovulation by suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis [129]. The delivery system may vary, including options like the OCP or the hormonal intrauterine device (IUD). Given that the VM is influenced by the balance of estrogen and progesterone [64], it is plausible that hormonal contraception may also impact the distribution of CSTs in the vagina and affect the colonization of Lactobacillus [130]. When comparing the effects of OCP use versus IUD use on the VM, contrasting results have been reported, with several studies revealing higher colonization by BV-related microorganisms (e.g., F. vaginae and G. vaginalis) regarding IUD use [131–134]. In turn, Bassis et al. [135] found no changes in the microbiome consistent with BV in women using IUDs.

In terms of BV treatment, there is an association between OCP use and a reduction in incident, prevalent, and recurrent BV [133,136]. However, certain hormonal contraceptives may alter the VM, decrease vaginal lactobacilli, and increase the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission [121,137]. In this respect, Eleuterio et al. [138] investigated the prevalence of Candida spp., Trichomonas vaginalis, and BV infections among new users of either the OCP or the hormonal IUD. They found that infection rates significantly increased at six weeks in both contraceptive groups but subsequently decreased over time. This initial rise in infections could be attributed to factors such as increased sexual activity and reduced condom use following the initiation of hormonal contraception, as the penile and smegma microbiomes of male partners have been shown to predict the onset of BV in women [139].

In addition, other contraceptive methods, such as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA, i.e., “the shot”) [137], have shown similar outcomes, maintaining a stable VM but with a reduced predominance of H2O2-lactobacilli [140]. In patients using DMPA, a notable presence of F. vaginae and Prevotella bivia was noted, suggesting the presence of BV at the time of sampling. The Levonorgestrel intrauterine system resulted in an increased incidence of BV and a shift towards CSTs with lower Lactobacillus colonization, indicating a move toward a non-optimal VM [133,141]. On the other hand, etonogestrel-implanted contraception has not been shown to provoke substantial changes in the VM [132].

Data on the effects of progesterone-only pills (POP, or “mini-pill”) on the VM remain limited. Some studies report no significant alterations in BV rates, although they do indicate higher rates of aerobic vaginitis and vaginal atrophy [132]. These effects are likely related to increased bleeding associated with POPs when compared to OCPs and hormonal IUDs [142]. The NuvaRing, an estrogen-containing vaginal ring, has demonstrated a tendency to enhance Lactobacillus predominance while reducing G. vaginalis in populations with a high prevalence of BV [143,144]. The copper T intrauterine device (Cu-IUD), which is a non-hormonal metal device that can be retained for up to 10 years, remains an effective contraceptive option. However, evidence on its influence on VM dysbiosis remains conflicting. While various studies have found no significant association between Cu-IUD use and BV [131,145], other research has reported a 1.28-fold increase in BV prevalence among Cu-IUD users compared to those using no contraception or other non-hormonal methods [146].

Sexual activity alters the composition and diversity of the VM, has an inflammatory effect on the vaginal epithelium, and increases the incidence of STDs [147,148]. Moreover, various sexual practices, including receptive oral sex, the use of sexual devices, penile-vaginal intercourse, and condom application, may directly alter the composition and stability of the VM [53,139,149].

A study involving 97 pubertal virgin women examined the dynamics of the VM before and after initiating sexual activity [150]. The findings indicated that those who had not engaged in sexual intercourse exhibited a stable VM composition over time, predominantly characterized by Lactobacillus species colonization. Conversely, the VM of sexually active individuals showed a prevalence of CST IV-B, with a predominance of G. vaginalis, which may negatively impact reproductive and sexual health by elevating the risk of BV. In addition, research indicates that G. vaginalis can be transiently acquired from the penile skin or smegma microbiota of a sexual partner [151]. Similar results have been reported in studies focused on the outcomes of sexual intercourse involving a stable partner [152]. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of the VM composition between women in monogamous relationships and those with multiple partners revealed no significant differences between the groups. However, individuals engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse exhibited a higher likelihood of colonization by CST III (L. iners), with G. vaginalis present at lower abundance [123,151,152]. In turn, van Houdt et al. [153] reported that sexually active women who did not cohabit with their partner experienced alterations in their vaginal microbiota and faced an elevated risk of infection, especially with Chlamydia trachomatis.

Several studies published in recent years have shown associations between human sexual behavior and BV. Concerning the frequency of vaginal intercourse, a higher number of coital events has been associated with an increased risk of BV [136]. Thus, engaging with several, new, or different male partners is directly associated with BV [154]. Additionally, maintaining unprotected sex has been linked to a higher risk of presenting BV, which is negatively related to the abundance of healthy Lactobacillus species [155]. Other reports have investigated the effect of various sexual practices on BV. For example, a significant association has been found between BV and female sexual partners. Women in homosexual relationships appear to face a higher risk in comparison to those engaged in heterosexual intercourse [149,156,157]. Moreover, there is a direct association between BV and vaginal intercourse when it follows receptive anal intercourse [158]. However, the interplay between BV and receptive oral sex is controversial [156]. In turn, women who engage in high-risk sexual behavior (sex work) presents a diverse VM, low in Lactobacillus species as in BV, which is linked to a greater prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and an increased risk of HIV acquisition [159]. Nevertheless, several factors must also be considered, such as diverse sexual practices, multiple partners, indiscriminate condom use, and frequent contraceptive use [53]. Fig. 4 provides an overview of how risk factors influence the composition of the VM and their subsequent effects (modified from [53]).

Figure 4: Effects of risk factors on the VM composition and their consequences. BPDE: benzo-α-pyrene diol epoxide; BV: bacterial vaginosis; PID: pelvis inflammatory disease; STI: sexually transmitted infections. Rectangles with green background: increase. Rectangles with red background: decrease. Green arrows: activation. Red arrows: inhibition

The VM represents a complex ecological environment primarily composed of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms, with the relationship between them highly dependent on several processes. The reviewed research reports that the VM has different features at different stages of the female life cycle. The VM composition and diversity are primarily influenced by sex hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, beginning at puberty and continuing throughout the reproductive years [4], as well as during menstrual cycle and pregnancy [39]. However, other factors influence the homeostasis of this ecosystem and alter its composition and functionality.

The aim of this review was to examine the influence of various endogenous and exogenous factors on the composition of the VM. Diverse studies have established an association between VM dysbiosis and several different pathologies such as BV, PID, and STIs [14,160–163]. During VM dysbiosis, the vagina experience changes in its bacterial composition, which is mainly dominated by strict anaerobic bacterial species (CST IV), compromising the epithelial barrier of the vaginal mucosa through the secretion of metabolites and enzymes, modifying the pH, and causing inflammation, thereby fostering the development of BV [164]. Therefore, evaluation of the aspects that impact the composition of the vaginal mucosa, especially those that promote dysbiosis, is an essential step for better management of these conditions.

This review also highlights that risk factors affecting VM homeostasis can be classified into non-modifiable factors (e.g., age, sex hormone levels, and ethnicity) and modifiable factors such as diet (e.g., folate, vitamins, carotenes, and oligoelements), probiotic intake, and the use of hormonal contraceptives. In contrast, the factors that influence the imbalance of VM and the transition to a state of dysbiosis are mainly of modifiable nature, such as fatty acid intake, tobacco smoking, psychosocial stress, hygiene practices, antibiotic use, and sexual activity [2,39,53]. In this regard, hormonal contraceptives, probiotic intake, personal hygiene, and diets rich in vitamins, betaine, carotenoids, and minerals (Ca2+ and Zn2+) increase the glycogen levels in the vaginal epithelial cells. These factors also elevate the abundance of lactobacilli in the VM, inducing a state of eubiosis that protects vaginal ecosystem from colonization by microbial pathogens. On the other hand, risk factors such as psychological stress, cigarette smoking, and sexual activity reduce the glycogen and lactobacilli levels, producing a dysbiosis of the VM and increasing the potential colonization of microbial pathogens, resulting in vaginal diseases.

A recent investigation by Qin et al. [165] identified 24 factors, including physiological parameters, lifestyle habits, gynecological history, and social and environmental variables, which were significantly associated with the composition of the VM. The authors suggested that the influence of age on the VM might be indirectly mediated through factors such as parity and lifestyle choices. Notably, women whose VM were dominated by L. iners or L. mulieris exhibited higher live birth rates compared to those whose microbiota were dominated by Fannyhessea vaginae. In a related study, Chen et al. [166] utilized a machine learning model to predict female infertility based on genus-level abundances within the VM. Their findings revealed that infertile women displayed a significantly altered VM profile, characterized by increased microbial diversity. Specifically, elevated levels of Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, and Prevotella were observed in the infertility group, whereas Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species were found in reduced abundance. Moreover, in the context of lifestyle choices, it is important to highlight how certain practices, particularly those influenced by social trends among young people, are often overlooked and can severely compromise vaginal health, potentially disrupting the VM and increasing the risk of infections and dysbiosis [167–171]. This underscores the need to prioritize vaginal health not only in clinical practice but also through individual self-care, emphasizing the importance of broader public awareness of its vulnerabilities and the factors that may compromise its balance.

It is clear, therefore, that the vagina plays a pivotal role in overall health, as its contribution extends beyond reproduction and other essential biological functions, including its involvement in maintaining microbial homeostasis, serving as a barrier against pathogens, supporting sexual well-being, and contributing to immunological and endocrine regulation. When alterations in the bacterial composition of the VM occur, the risk of pathological conditions and urinary tract infections increases significantly [13,14]. Apart from localized infections, VM imbalances can trigger inflammatory cascades and immune dysfunction, contributing to a range of reproductive health disorders [172,173]. Furthermore, the maternal VM plays a critical role in shaping the microbial colonization of neonates during vaginal delivery [174]. Consequently, maternal infections heighten the likelihood of pathogen transmission at birth, whereas infants delivered via cesarean section acquire microbial communities resembling maternal skin microbiota [175]. Given these interconnections, maintaining VM stability is of utmost priority, not only for individual welfare but also for its transgenerational impact. Advancing our understanding of the mechanisms governing VM equilibrium and adaptability, as well as their potential disruptors, could facilitate the development of innovative strategies to prevent and mitigate reproductive and perinatal health complications.

In the immediate future, it will be very important to conduct studies that explore the influence of social sexual networks on the shaping of the VM and on their role in the transmission and prevalence of vaginal diseases. This would require additional extensive longitudinal studies examining the impact of overlapping sexual partners and the duration of concurrent relationships on the VM across different cultures and populations. Furthermore, research focusing on sexual behaviors, such as the sequence of sexual activities and the frequency of coital intercourse, could help explain variations in the composition of the VM and offer essential information for reducing the risk of dysbiosis in women.

As with any review, this work is subject to several limitations. (i) Some studies use the term “vagina” as a broad descriptor for the entire genital area, even though the vulva and vagina are anatomically distinct, each with its own unique microbial environment [176]. (ii) The metabolic interactions between the VM and its host, as well as those within the microbiota itself, remain largely undefined. Although some studies have begun to explore the functionality of the VM, further research is needed to assess the protein transcription profiles of both microorganisms and the host [177,178]. (iii) It is important to note that the studies included in this review primarily focus on bacterial communities. However, the rapidly growing fields of vaginal mycobiome and viral community research could provide important insights into the path toward VM homeostasis [179,180].

The human VM is characterized by low diversity, with Lactobacillus spp. predominating compared to the microbiome of other body sites. The VM and the host coexist in a mutually beneficial relationship within the vaginal microenvironment. Host cells provide glycogen as an energy source for Lactobacillus, which in turn produces lactic acid, lowering the vaginal pH and inhibiting the growth of other bacteria. The involvement of several habits and lifestyle factors in VM alterations is pivotal. Thus, it is essential to raise awareness among women about the impact of these factors on their health, as well as educate them on practices that promote a balanced VM. Reducing dysbiosis and stabilizing the VM could play a key role in lowering the prevalence of conditions such as BV, PID, and STIs, all of which have been increasingly reported in recent years. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota may also be linked to the risk of preterm birth, insemination failure, cervical cancer, HIV transmission, and other STIs. Therefore, recognizing the VM as a vital and integral aspect of women’s health represents an important public health concern and priority. However, there is still a need for further research in this field, along with more integrated collaboration between researchers, healthcare providers, and public health organizations. Such initiatives will ultimately enhance our understanding of women’s health and contribute to the development of improved healthcare strategies and outcomes.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Alejandro Borrego-Ruiz and Juan J. Borrego; investigation, Juan J. Borrego; writing—original draft preparation, Alejandro Borrego-Ruiz and Juan J. Borrego; writing—review and editing, Alejandro Borrego-Ruiz; supervision, Juan J. Borrego. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| VM | Vaginal microbiome |

| CSTs | Community-State Types |

| BV | Bacterial vaginosis |

| STDs | Sexually transmitted diseases |

| HRT | Hormone replacement therapy |

| PID | Pelvis inflammatory disease |

References

1. Marchesi JR, Ravel J. The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal. Microbiome. 2015;3(1):31. doi:10.1186/s40168-015-0094-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Barrientos-Durán A, Fuentes-López A, de Salazar A, Plaza-Díaz J, García F. Reviewing the composition of vaginal microbiota: inclusion of nutrition and probiotic factors in the maintenance of eubiosis. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):419. doi:10.3390/nu12020419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl. 1):4680–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UM, Zhong X, et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(132):132ra52. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Shen L, Zhang W, Yuan Y, Zhu W, Shang A. Vaginal microecological characteristics of women in different physiological and pathological period. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:959793. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.959793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jimenez NR, Maarsingh JD, Łaniewski P, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Commensal lactobacilli metabolically contribute to cervical epithelial homeostasis in a species-specific manner. mSphere. 2023;8(1):e0045222. doi:10.1128/msphere.00452-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Osei Sekyere J, Oyenihi AB, Trama J, Adelson ME. Species-specific analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(4):e0467622. doi:10.1128/spectrum.04676-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74(1):14–22. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Chee WJY, Chew SY, Than LTL. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19(1):203. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01464-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Auriemma RS, Scairati R, del Vecchio G, Liccardi A, Verde N, Pirchio R, et al. The vaginal microbiome: a long urogenital colonization throughout woman life. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:686167. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.686167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bardos J, Fiorentino D, Longman RE, Paidas M. Immunological role of the maternal uterine microbiome in pregnancy: pregnancies pathologies and alterated microbiota. Front Immunol. 2020;10:2823. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Amabebe E, Anumba DOC. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of lactobacilli. Front Med. 2018;5:181. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Holdcroft AM, Ireland DJ, Payne MS. The vaginal microbiome in health and disease—what role do common intimate hygiene practices play? Microorganisms. 2023;11(2):298. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11020298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kalia N, Singh J, Kaur M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: a critical review. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):5. doi:10.1186/s12941-020-0347-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Navarro S, Abla H, Delgado B, Colmer-Hamood JA, Ventolini G, Hamood AN. Glycogen availability and pH variation in a medium simulating vaginal fluid influence the growth of vaginal Lactobacillus species and Gardnerella vaginalis. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):186. doi:10.1186/s12866-023-02916-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Sukhera J. Narrative reviews: flexible, rigorous, and practical. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(4):414–7. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00480.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, Tarca AL, Fadrosh DW, Bieda J, et al. The vaginal microbiota of pregnant women who subsequently have spontaneous preterm labor and delivery and those with a normal delivery at term. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):18. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-2-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(237):237ra65. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Costello EK, DiGiulio DB, Robaczewska A, Symul L, Wong RJ, Shaw GM, et al. Abrupt perturbation and delayed recovery of the vaginal ecosystem following childbirth. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4141. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39849-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kaur H, Merchant M, Haque MM, Mande SS. Crosstalk between female gonadal hormones and vaginal microbiota across various phases of women’s gynecological lifecycle. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:551. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Vodstrcil LA, Plummer EL, Doyle M, Fairley CK, McGuiness C, Bateson D, et al. Treating male partners of women with bacterial vaginosis (StepUpa protocol for a randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical effectiveness of male partner treatment for reducing the risk of BV recurrence. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):834. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05563-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Trifanescu OG, Trifanescu RA, Mitrica RI, Bran DM, Serbanescu GL, Valcauan L, et al. The female reproductive tract microbiome and cancerogenesis: a review story of bacteria, hormones, and disease. Diagnostics. 2023;13(5):877. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13050877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Condori-Catachura S, Ahannach S, Ticlla M, Kenfack J, Livo E, Anukam KC, et al. Diversity in women and their vaginal microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2025;10:398. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2024.12.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Roberts SA, Brabin L, Diallo S, Gies S, Nelson A, Stewart C, et al. Mucosal lactoferrin response to genital tract infections is associated with iron and nutritional biomarkers in young Burkinabe women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(11):1464–72. doi:10.1038/s41430-019-0444-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nasioudis D, Witkin SS. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and innate immune responses to bacterial infections. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204(4):471–9. doi:10.1007/s00430-015-0394-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Digiulio DB, Callahan BJ, Mcmurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(35):11060–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. MacIntyre DA, Chandiramani M, Lee YS, Kindinger L, Smith A, Angelopoulos N, et al. The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a European population. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):8988. doi:10.1038/srep08988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Serrano MG, Parikh HI, Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Arodz TJ, Edupuganti L, et al. Racioethnic diversity in the dynamics of the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):1001–11. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hernandez-Rodriguez C, Romero-Gonzalez R, Albani-Campanario M, Figueroa-Damian R, Meraz-Cruz N, Hernandez-Guerrero C. Vaginal microbiota of healthy pregnant Mexican women is constituted by four Lactobacillus species and several vaginosis-associated bacteria. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011(4):851485. doi:10.1155/2011/851485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Bayar E, Bennett PR, Chan D, Sykes L, MacIntyre DA. The pregnancy microbiome and preterm birth. Sem Immunopathol. 2020;42(4):487–99. doi:10.1007/s00281-020-00817-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Biagioli V, Matera M, Ramenghi LA, Falsaperla R, Striano P. Microbiome and pregnancy dysbiosis: a narrative review on offspring health. Nutrients. 2025;17(6):1033. doi:10.3390/nu17061033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Paramel Jayaprakash T, Wagner EC, Van Schalkwyk J, Albert AY, Hill JE, Money DM, et al. High diversity and variability in the vaginal microbiome in women following preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROMa prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166794. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Moreno I, Simon C. Deciphering the effect of reproductive tract microbiota on human reproduction. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;18(1):40–50. doi:10.1002/rmb2.12249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Urushiyama D, Ohnishi E, Suda W, Kurakazu M, Kiyoshima C, Hirakawa T, et al. Vaginal microbiome as a tool for prediction of chorioamnionitis in preterm labor: a pilot study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18971. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98587-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li H, Han M, Xu J, Li N, Cui H. The vaginal microbial signatures of preterm birth woman. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2024;24(1):428. doi:10.1186/s12884-024-06573-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang J, Han T, Zhu X. Role of maternal-fetal immune tolerance in the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. Chin Med J. 2024;137(12):1399–406. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000003114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Weng J, Couture C, Girard S. Innate and adaptive immune systems in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Biology. 2023;12(3):402. doi:10.3390/biology12030402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mitchell CM, Srinivasan S, Zhan X, Wu MC, Reed SD, Guthrie KA, et al. Vaginal microbiota and genitourinary menopausal symptoms: a cross-sectional analysis. Menopause. 2017;24(10):1160–6. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Lehtoranta L, Ala-Jaakkola R, Laitila A, Maukonen J. Healthy vaginal microbiota and influence of probiotics across the female life span. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:819958. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.819958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Xu J, Bian G, Zheng M, Lu G, Chan WY, Li W, et al. Fertility factors affect the vaginal microbiome in women of reproductive age. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;83(4):e13220. doi:10.1111/aji.13220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Santoro N, Roeca C, Peters BA, Neal-Perry G. The menopause transition: signs, symptoms, and management options. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(1):1–15. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Nappi RE, Martini E, Cucinella L, Martella S, Tiranini L, Inzoli A, et al. Addressing vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)/genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) for healthy aging in women. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:561. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mitchell CM, Ma N, Mitchell AJ, Wu MC, Valint DJ, Proll S, et al. Association between postmenopausal vulvovaginal discomfort, vaginal microbiota, and mucosal inflammation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(2):159.e1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.02.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gliniewicz K, Schneider GM, Ridenhour BJ, Williams CJ, Song Y, Farage MA, et al. Comparison of the vaginal microbiomes of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:193. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Serrano MG, Sheth NU, Girerd PH, Edwards DJ, et al. Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology. 2014;160(10):2272–82. doi:10.1099/mic.0.081034-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kim S, Seo H, Rahim MA, Lee S, Kim YS, Song HY. Changes in the microbiome of vaginal fluid after menopause in Korean women. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;31(11):1490–500. doi:10.4014/jmb.2106.06022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zeng Q, Shu H, Pan H, Zhang Y, Fan L, Huang Y, et al. Associations of vaginal microbiota with the onset, severity, and type of symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1402389. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1402389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Fait T. Menopause hormone therapy: latest developments and clinical practice. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212551. doi:10.7573/dic.212551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Devillard E, Burton JP, Hammond JA, Lam D, Reid G. Novel insight into the vaginal microflora in postmenopausal women under hormone replacement therapy as analyzed by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;117(1):76–81. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cauci S, Driussi S, De Santo D, Penacchioni P, Iannicelli T, Lanzafame P, et al. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal flora changes in peri- and postmenopausal women. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(6):2147–52. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.6.2147-2152.2002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Flores VA, Pal L, Manson JE. Hormone therapy in menopause: concepts, controversies, and approach to treatment. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(6):720–52. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnab011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Pan M, Pan X, Zhou J, Wang J, Qi Q, Wang L. Update on hormone therapy for the management of postmenopausal women. Biosci Trends. 2022;16(1):46–57. doi:10.5582/bst.2021.01418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Morsli M, Gimenez E, Magnan C, Salipante F, Huberlant S, Letouzey V, et al. The association between lifestyle factors and the composition of the vaginal microbiota: a review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024;43(10):1869–81. doi:10.1007/s10096-024-04915-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Petersen C, Round JL. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16(7):1024–33. doi:10.1111/cmi.12308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhou X, Hansmann MA, Davis CC, Suzuki H, Brown CJ, Schütte U, et al. The vaginal bacterial communities of Japanese women resemble those of women in other racial groups. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;58(2):169–81. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00618.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Chaban B, Links MG, Jayaprakash TP, Wagner EC, Bourque DK, Lohn Z, et al. Characterization of the vaginal microbiota of healthy Canadian women through the menstrual cycle. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):23. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-2-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zhou X, Brown CJ, Abdo Z, Davis CC, Hansmann MA, Joyce P, et al. Differences in the composition of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Caucasian and Black women. ISME J. 2007;1(2):121–33. doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Verstraelen H, Vilchez-Vargas R, Desimpel F, Jauregui R, Vankeirsbilck N, Weyers S, et al. Characterisation of the human uterine microbiome in non-pregnant women through deep sequencing of the V1-2 region of the 16S rRNA gene. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1602. doi:10.7717/peerj.1602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Albert AY, Chaban B, Wagner EC, Schellenberg JJ, Links MG, van Schalkwyk J, et al. A study of the vaginal microbiome in healthy Canadian women utilizing cpn60-based molecular profiling reveals distinct Gard-nerella subgroup community state types. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Gautam R, Borgdorff H, Jespers V, Francis SC, Verhelst R, Mwaura M, et al. Correlates of the molecular vaginal microbiota composition of African women. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):86. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0831-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]