Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Metronomic Chemotherapy Response in MDA-MB-231 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells under Nicotine Exposure

1 Tumor Immunopharmacology Laboratory, Center of Pharmacological and Botanical Studies (CEFYBO)-National Council for Science and Technology (CONICET), University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, C1121ABG, Argentina

2 Second Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, C1121ABG, Argentina

* Corresponding Author: Alejandro Javier Español. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Role of Cancer Stem Cells)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1449-1480. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068034

Received 20 May 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Triple-negative (TN) breast cancer, the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, is usually treated with high doses of paclitaxel (PX), which induces resistance. To prevent this adverse effect, metronomic chemotherapy based on administering low doses of PX plus carbachol (Carb), a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) agonist, has emerged as an alternative. Other acetylcholine receptors also present in breast tissue are nicotinic ones. When activated by nicotine (Nic), these receptors can decrease the effectiveness of conventional chemotherapy. However, whether metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb is affected by Nic has not yet been described. This study aimed to determine the efficacy of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb in human breast tumor MDA-MB-231 cells in the presence or absence of Nic and assess the intermediaries involved. Methods: Cell viability and proliferation were determined using colorimetric assays with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and trypan blue. Nitrite levels in cell supernatant were determined using Griess reagent. The expression of proteins was determined by western blot assays. Apoptosis/necrosis and the proportion of cancer stem cells (CSC) were determined by flow cytometry. Mammosphere-forming units were determined with anchorage-free growth assays. Results: The metronomic chemotherapy combining PX and Carb effectively inhibited the viability of TN MDA-MB-231 cells in the presence and absence of Nic. These effects were mediated by the activation of mAChRs, triggering signaling pathways dependent on several kinases. These mediators induce increased expression of the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Only the inducible and endothelial isoforms were expressed in these cells, and their activity was increased by the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb. Nitric oxide (NO), a product of NOS activity, may contribute to the observed increase in apoptosis. We also observed an increased sensitivity to PX in the residual cells after the metronomic chemotherapy, as well as a decrease in mammosphere-forming units and CSC proportion. We also determined a decrease in the expression of stemness proteins such as ATP-binding cassette super-family G member 2 (ABCG2), sex-determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2), octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4), and Nanog. Conclusions: Metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb was selective for MDA-MB-231 cells and increased their sensitivity to conventional chemotherapy in the presence and absence of Nic, indicating that it could be a useful neoadjuvant strategy for the treatment of TN breast tumors.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCancer is a heterogeneous pathology characterized by loss of contact inhibition and uncontrolled cell proliferation. It can develop in any organ, but breast cancer has the highest incidence and mortality rates among the female population worldwide [1,2]. To predict tumor behavior and determine the optimal treatment, breast cancer is classified into four main subtypes, based on the expression or absence of estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and the expression of the HER2 oncogene [3]. TN breast cancer subtype is characterized by the lack of expression of ER, PR, or the HER2 oncogene [4]. Patients with TN tumors usually have a poor prognosis, as this is a highly invasive subtype and lacks specific markers that serve as therapeutic targets [5]. TN breast cancer tumors are classically treated with the cytostatic agent PX at the highest dose tolerated by the patient. PX is a taxane that actively stabilizes the cytoskeleton, preventing depolymerization and arresting the cell cycle in the G2/M phase, resulting in cell death [2,6,7]. However, due to its low specificity of action, it causes numerous adverse effects and requires prolonged inter-dose periods to allow for patient recovery. During these drug-free periods between PX cycles, tumor cells may also recover and develop a treatment-resistant clone [8]. The primary problem with the use of this chemotherapy is the innate or acquired resistance to it, which is the main cause of therapy failure [9]. In this sense, Yin et al. [10] found that resistance to PX treatment is related to a high expression of membrane proteins that act as transporters, eliminating drugs that enter the cytoplasm and thus decreasing their efficacy. The most observed mechanism of multidrug resistance to PX in tumor cells is the overexpression of the ABCG2 transporter [11,12]. CSC, a tumor subpopulation, exhibits high expression of these ABCG2 transporters [13], which confer intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy [14]. It has been described that successive cycles of conventional PX treatment can increase the proportion of CSC present in a tumor by selecting them from the residual cell population after treatment [15]. In breast CSC, different stemness markers, such as OCT-4, SOX-2, and Nanog, have been described [16].

To prevent the adverse effects of conventional chemotherapy with PX, a new cancer treatment regimen, known as metronomic chemotherapy, based on the administration of low-dose chemotherapy with short drug-free intervals, has emerged [17]. An additional strategy to enhance the benefits of metronomic chemotherapy is drug repositioning, which consists of assigning new therapeutic uses to drugs already approved for the treatment of other pathologies. In particular, targeted drug repositioning consists of choosing these drugs based on specific therapeutic targets [18]. This is the case of the muscarinic agonist Carb, which, when combined with PX in a metronomic administration schedule, causes a decrease in cell viability via the activation of mAChRs. This decrease in cell viability is of the same magnitude as that achieved with the therapeutic dose of PX in TN cells [19]. Since mAChRs are present in breast tumor cells but not in normal breast cells, this metronomic chemotherapy combining PX and Carb selectively targets breast tumor cells [20,21]. mAChRs activate several mediators capable of modulating cell viability, including phospholipase C (PLC), protein kinase C (PKC), Ras, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK), extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1/2, Ikappa kinase subunit beta (IKKβ), and NOS [22]. NOS has three isoforms: the neuronal (nNOS), the inducible (iNOS), and the endothelial (eNOS) ones [23]. One of the products of NOS activity is NO, which can promote either cell proliferation or apoptosis depending on its concentration, thereby modulating the efficacy of chemotherapy [24]. Other acetylcholine receptors present in the mammary gland that can negatively modulate the response to chemotherapy are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [25]. These receptors are activated by Nic, which is the primary active component of cigarette smoke. Although it has been described that short-term treatment with Nic negatively modulates the efficacy of conventional antitumor therapy [25,26], little is known about the modulating effect of chronic exposure to Nic on antitumor efficacy. In this sense, Zhao et al. [27] and Li et al. [28] have described that chronic treatment with Nic can decrease the antitumor efficacy in pancreatic and lung tumor cells. Although we have previously demonstrated the antitumor efficacy of metronomic therapy combining PX and Carb [19], there is no evidence regarding the intracellular mediators involved, the role of CSC, or the possible modulation by chronic treatment with Nic. Understanding the signaling pathways involved in the possible nicotinic modulation of the efficacy of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX and Carb is relevant, as this could improve the antitumor response.

With more than 160 million active female smokers worldwide, the search for anti-tumor therapies that are unaffected or less affected by Nic is imperative. Thus, the aims of the present study were: (i) to determine the efficacy of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX and Carb in human breast tumor MDA-MB-231 cells, which present a well-characterized aggressive phenotype, in the presence or absence of Nic at concentrations similar to those found in the plasma of smoking patients, and (ii) to investigate the intermediaries involved and the modulation of pluripotency factors characteristic of CSC.

The human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MDA-MB-231 (CRM-HTB-26) and the non-tumorigenic cell line MCF-10A (CRL-10317), used as control, were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VI, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, 12100-046, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, 49419, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 80 μg/mL gentamycin (Richet, 235186-3, Munro, Buenos Aires, Argentina), supplemented with heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 10% (Internegocios SA, FBI code, Mercedes, Buenos Aires, Argentina) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. In the MCF-10A cells, the medium was also supplemented with hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich, H0888) (0.5 μg/mL), insulin (Densulin, 52706, Munro, Buenos Aires, Argentina) (10 μg/mL), and human epidermal growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich, E5036) (20 ng/mL). Cells were detached from confluent monolayers by using the following buffer: 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich, 798681) in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The medium was replaced with fresh medium three times a week. Cell viability was determined by the Trypan blue exclusion test, and the absence of mycoplasma was observed by Hoechst (Invitrogen, H3570, Eugene, OR, USA) staining [29].

The inhibition of cell viability exerted by different treatments was analyzed using the soluble MTT colorimetric assay (Life Technologies, 298-93-1, Eugene, OR, USA) [30]. In viable cells, MTT is reduced to formazan. A total of 4 × 103 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates in culture medium supplemented with 5% FBS (Internegocios SA, FBI code) and then left to adhere overnight. When cells reached 65% to 75% confluence, they were deprived of FBS for 24 h prior to the assay to synchronize the cultures. Then, cells were treated with Nic (Sigma-Aldrich, N0267) (which is a non-selective nAChR receptor agonist) for 15 days, or PX (IMA, 49765, CABA, Buenos Aires, Argentina) combined with Carb (Sigma-Aldrich, 212385-M) for three 48-h cycles, interspersed with 24-h drug-free intervals, either alone or in combination. According to previous results, this metronomic chemotherapy administration scheme combining PX with Carb is the most effective in these cells [31]. Cells were previously treated for 30 min to inhibit the action of cholinergic agonists with atropine (AT) (Sigma-Aldrich, 1044990)(a non-selective mAChR antagonist), mecamylamine (MM) (Sigma-Aldrich, M9020) (a non-selective nAChR antagonist) or the selective antagonists pirenzepine (Pir, for M1 mAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, P7412), methoctramine (Met, for M2 mAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, 104807-40-1), 4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methyl-piperidine (Damp, for M3 mAChR) (Cayman Chemical, 14574, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), tropicamide (Trop, for M4 mAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, T9778), xanomeline (Xan, for M5 mAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, 141064-23-5), methyllycaconitine (MLA, for α7 nAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, M168) or luteolin (Lut, for α9 nAChR) (Sigma-Aldrich, L9283) (Table S1). To determine the participation of several mediators in the effects of drugs, cells were pretreated for 30 min with different enzymatic inhibitors to: PLC [2-nitro-4-carboxyphenyl N,N-diphenyl carbamate (NCDC) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CAS 10556-88-4, Dallas, TX, USA)], PKC [staurosporine (Stau) (Sigma-Aldrich, S5921)], Ras [S-trans,trans-farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS) (Cayman Chemical Company, 10010501)], MEK [PD098059 (PD) (Sigma-Aldrich, 513001)], ERK 1/2 (U126) (Promega, V112A, Madison, WI, USA), IKKβ [IMD354 (IMD) (Sigma-Aldrich, I3159], nNOS (N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl](amino]pentyl]-N′-nitroguanidine Tris (4S-AEPN) (Sigma-Aldrich, A5727), iNOS [aminoguanidine (AG) (Sigma-Aldrich, 396494)]), eNOS [L-N5-(1-iminoethyl) ornithine hydrochloride (L-NIO) (Sigma-Aldrich, I134)] or NOS [NGmonomethyl-L arginine (l-nmma) (Sigma-Aldrich, M7033)] (Table S1). After treatments, cell viability and sensitivity to PX were assessed. To detect cell viability, the medium was replaced by 110 μL of MTT solution, which was prepared by diluting 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT in PBS, in 100 μL medium free of phenol red and FBS in each well. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, the production of formazan was measured by analyzing the absorbance at 540 nm with an ELISA reader (BioTek, MQX200, Winooski, VE, USA).

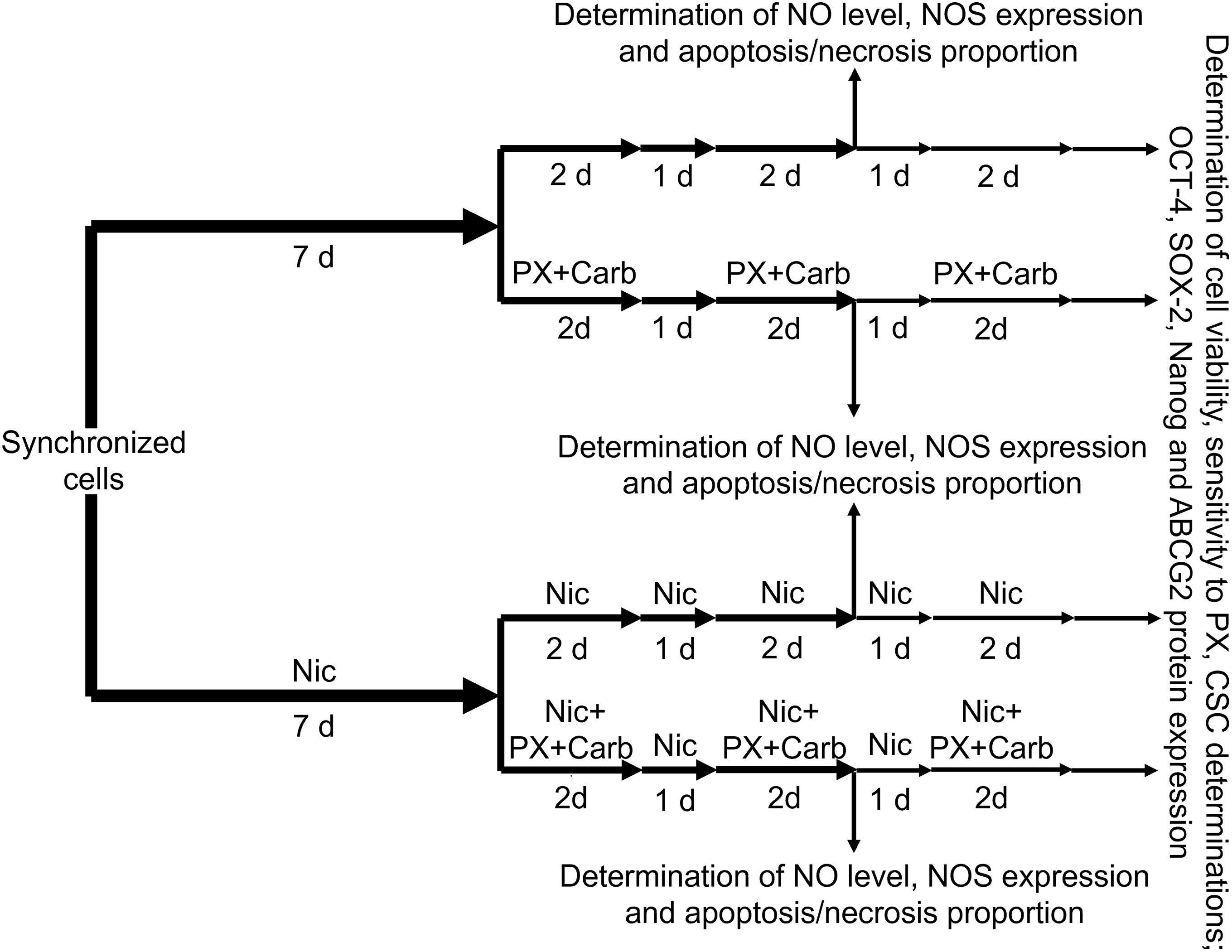

To analyze cell sensitivity to PX, residual cells after treatment were detached using PBS containing 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, 15090-046) and 0.02% EDTA and seeded in 96-well plates. A total of 4 × 103 viable cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates in culture medium supplemented with 5% FBS (Internegocios SA, FBI code). Cells were left to adhere overnight and then deprived of FBS for 24 h to induce the synchronization of cultures. Next, cells were treated with PX (100 nM), and cell sensitivity was determined by the MTT assay in the same way as in cell viability assays. Values are mean results expressed as the percentage of cell viability. A diagram illustrating the administration schedule for the determination of both cell sensitivity and cell viability is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Diagram of the administration schedule for the determination of nitric oxide (NO) levels, nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression, apoptosis and necrosis proportion, cell viability or cell sensitivity to chemotherapy, mammosphere formation, and protein expression of sex-determining region Y-box 2 (SOX-2), octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4), Nanog and ATP-binding cassette super-family G member 2 (ABCG2). d: days; PX: Paclitaxel; Carb: Carbachol; Nic: Nicotine; CSC: cancer stem cells

2.3 Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay

For the trypan blue exclusion assay, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a ratio of 10,000 cells per well. After the treatments, viable and non-viable cells were collected and centrifuged (Sorvall-Dupont, RT6000, Newtown, CT, USA) at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The pellets were resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM (Gibco 12100-046) and trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, T6146). Cells were counted using a hemocytometer under an inverted microscope (Arcano, 1118918, Xiamen, Fujian, China) at 40 X magnification. Unstained cells were considered viable and expressed as a percentage of the total cells [32].

NO production was determined in culture supernatants by measuring the accumulation of nitrite (NO2−). Residual cells after the different treatments were seeded (104 per well) in triplicate in 96-well plates with 100 μL of medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium without FBS, and NO2− accumulation was assessed after 48 h in culture supernatants by using Griess reagent [1% sulfanilamide (Sigma-Aldrich, S9251) in 30% acetic acid (Anedra, 6010, San Fernando, Buenos Aires, Argentina) with 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich, N9125) in 60% acetic acid)] [33]. Absorbance was measured with an ELISA reader at 540 nm (Biotek, MQX200, Winooski, VE, USA). Nitrite concentration was determined using a standard curve of NaNO2 diluted in culture medium. The results are expressed as micromolar concentration of NO2− per 104 cells (μM/104 cells). A diagram of the administration scheme for this determination is shown in Fig. 1.

2.5 Western Blot Protein Analysis

For protein analysis, residual cells after the different treatments (2 × 106) were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 1 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, 798681), 1 mM EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich 324626), 5 mM NaF (Cicarelli, 1081211, Munro, Buenos Aires, Argentina), 5 mM MgCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, M1028), 5 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, 78830), 1% Triton X-100 (Cicarelli, PA142314), 50 mM NaCl (Cicarelli, 750), 10 μg/mL trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, P2714), 10 μg/mL leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich, L2884) and 10 μg/mL aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich, A4529), pH 7.4. Lysates were incubated on an ice bath for 1 h and then centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were stored at −80°C, and protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method [34]. Protein samples (80 μg of protein per lane) were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-PAGE minigel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad, 162-0115, Feldkirchen, Munich, Germany). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris Buffered Saline with Tween (TBS-T) and incubated at 4°C overnight with different anti-human primary antibodies obtained from rabbits: nNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1025, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), iNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8310), eNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-654), ABCG2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-130933), Nanog (ABClonal, A22625, Woburn, MA, USA), SOX-2 (ABClonal, A19118) and OCT-4 (ABClonal, A7920), with the first four diluted 1:100 and the last three diluted 1:1000 in TBS-T. After several rinses with TBS-T, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, ab6734, Cambridge, MA, USA), diluted 1:10,000 in TBS-T at 37°C for 1 h. The bands were visualized by chemiluminescence. Expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) diluted 1:300 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-25778) was used as a loading control [27]. Densitometric results are expressed as units of fold increase relative to the control treatment. A diagram of the administration scheme for these protein determinations is shown in Fig. 1.

2.6 Determination of Apoptosis and Necrosis by Flow Cytometry

To determine apoptosis and necrosis, residual cells after the treatments were detached using PBS containing 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, 15090-046) and 0.02% EDTA. Cells were resuspended in culture medium and centrifuged at 1000 g for 1 min at 4°C (Sorvall-Dupont, RT6000). Supernatants were discarded, and pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of DMEM/F12 without phenol red (Gibco, 21041025). The cell concentration was adjusted to 5 × 105 viable cells/100 μL of DMEM/F12 without phenol red. Fluorescein (FIT-C)-conjugated Annexin-V (BD Biosciences, 560931, Trenton, NJ, USA) and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (Invitrogen, A1310) were added to the cell suspensions at concentrations recommended by the manufacturer and incubated on ice in the dark for 30 min. After incubation, cell suspensions were washed twice with binding buffer (Hepes 10 mM (Sigma-Aldrich, H4034), NaCl 14 mM (Cicarelli, 759), and CaCl2 2.5 mM (Cicarelli, 879), pH: 7.4) and immediately analyzed on a flow cytometer (BD, Accuri C6Plus). All appropriate compensation checks were performed. The results were analyzed with the Cyflogic software (CyFlo Ltd., Turku, Finland). In the dot-plot graphs made, live cells were represented as Annexin-V−/7-AAD−, cells in apoptosis as Annexin-V+/7-AAD−, and cells in necrosis as Annexin-V+/7-AAD+. Values are presented as means, and results are expressed as the percentage of cell apoptosis or necrosis. A diagram of the administration scheme for the determination of apoptosis and necrosis is shown in Fig. 1.

2.7 Determination of Mammosphere Formation by Extreme Limiting Dilution Assay

Mammosphere-forming units were determined by an extreme limiting dilution assay (ELDA). Briefly, 96-well plates were treated with 50 μL/well of a solution of 20 mg/mL ethanol 95% of Poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich, P3932) to form a hydrogel layer. Then, plates were left to dry overnight at 37°C, and decreasing concentrations of residual viable cells after the different treatments (300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 cells) were seeded (24 wells/treatment). Cells were resuspended in 200 μL of medium supplemented with 2% B27 (Gibco, 12587-010), 1% glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, 49419), 0.1% methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, H7509), 20 ng/μL epidermal growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich, 5036) and 20 ng/μL basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich, GF003AF). After 10 days of culture, images of the mammospheres were obtained using a microscope (Arcano, 1118918) with a camera (Arcano 3.0, 1G3617, Xiamen, Fujian, China) (64 X). Cell aggregates >80 μm were considered positive in a blind count. The frequency of mammosphere-forming units in the cultures was determined with the online web tool from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research Bioinformatics Division [35]. A diagram of the administration scheme for ELDA determination is shown in Fig. 1.

2.8 Analysis of the Proportion of Cancer Stem Cells by Flow Cytometry

To identify the proportion of CSC (CD44+/CD24− cell population), residual cells after the treatment were resuspended with 5 mL of fresh medium without phenol red (Gibco, 21041025) and with 5% FBS (Internegocios SA, FBI code) and centrifuged at 1000 g for 1 min at 4°C (Sorvall-Dupont, RT6000). The pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of medium without phenol red containing 0.5% FBS, and the cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells per tube. Antibodies against human CD44 coupled to phycoerythrin (BD Biosciences, 561858) and CD24 coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Biosciences, 560992) were added to the cell suspensions at concentrations recommended by the manufacturer and incubated at 4°C in the dark for 30 min. The labeled cells were washed twice with medium without phenol red containing 2% FBS and then analyzed by flow cytometry (BD, Accuri C6plus). The BD Accuri C6 plus software was used to identify cell subpopulations. CD44+/CD24− cells were defined as breast CSC [36].

2.9 Calculation of the Effective Concentrations 50 and 25

Dose-response data were transformed by using the GraphPad Prism8 (8.0.1-244) software (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA), converted to percentage, and fitted to a sigmoid curve following a maximum effective concentration (Emax) model with at least six data points. Effective concentration 50 (EC50), EC25, and Emax values were obtained from this analysis. Only data with an EC50 coefficient of variation less than 20% were considered.

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The significance of differences between mean values in all control and test samples was determined using the GraphPad Prism8 (8.0.1-244) software, specifically using one-way ANOVA. The analysis was complemented by a Tukey test to compare mean values. Differences between means were considered significant if p < 0.05. Data and statistical analysis complied with the recommendations for experimental design and analysis in pharmacology [37].

3.1 Effect of Chronic Nicotine Exposure on MDA-MB-231 Cell Viability

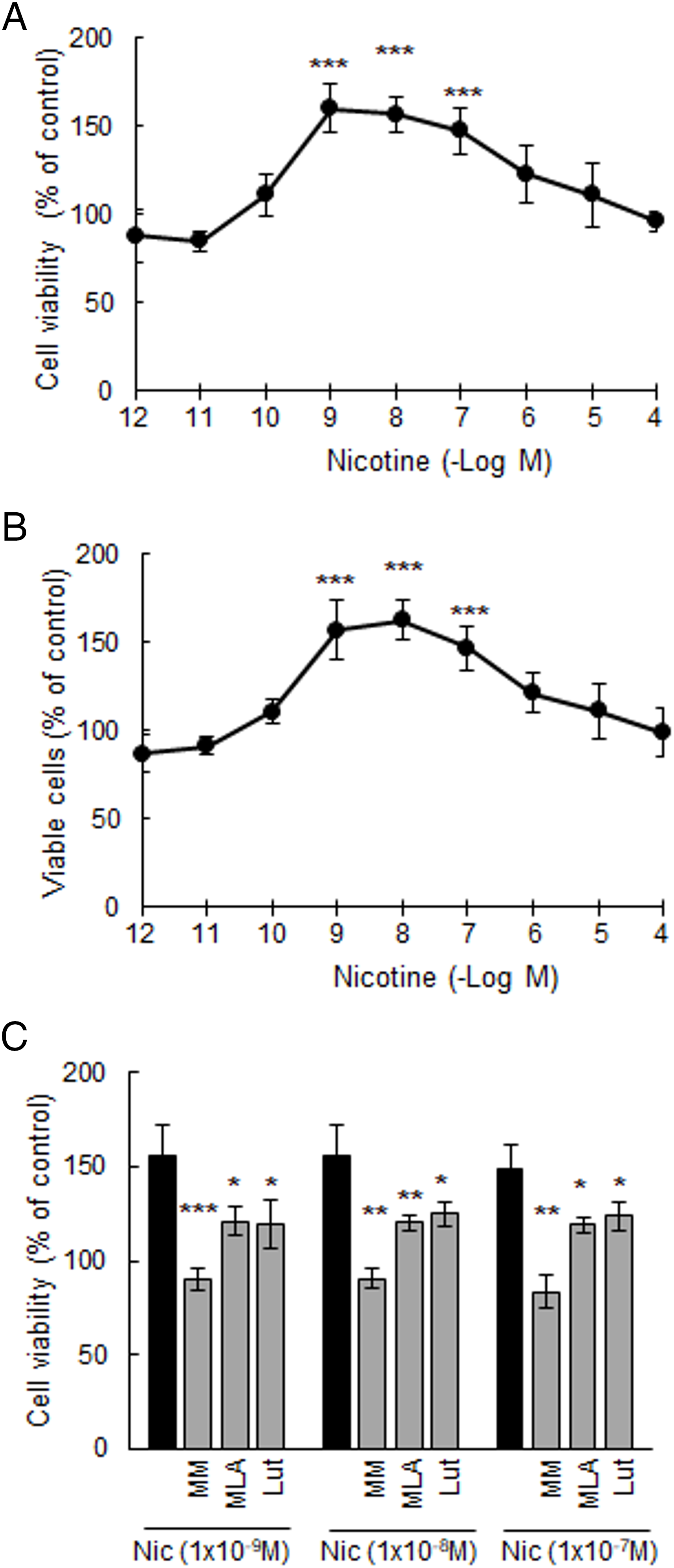

To evaluate the chronic effects of Nic, we first analyzed its impact on MDA-MB-231 cells in culture following treatment for 2, 8, 15, and 22 days (Fig. S1). We have previously described that these cells basally express α7 and α9 nAChRs [25]. Here, we demonstrated that these receptor subtypes were functionally active, since the addition of Nic increased cell viability at all time points, within a concentration range of 1 nM (1 × 10−9 M) to 100 nM (1 × 10−7 M), with an Emax of 159.9 ± 14.0% after 15 days of treatment (Fig. 2A). At 22 days of treatment, we observed an Emax (157.3 ± 6.5%) similar to that observed at 15 days. However, at this later time point, we found a decrease in cell viability at concentrations equal to or greater than 10 μM (1 × 10−5 M) (10 μM: 61.3 ± 2.7%; 100 μM: 64.5 ± 10.4%). Since this effect could be attributed to the toxicity of prolonged Nic treatment, we decided to use a 15-day administration schedule. The effect of Nic was established by analyzing the proportion of viable cells using the trypan blue exclusion assay, which yielded results consistent with those obtained by the MTT assay (Fig. 2B). The stimulatory effects of Nic on cell viability were significantly reduced by pretreating cells for 30 min with 1 μM of different nicotinic antagonists, including MM (non-selective), MLA (α7 nAChR selective) and Lut (α9 nAChR selective), indicating the involvement of both nAChR subtypes (Fig. 2C). The nicotinic antagonists alone at this concentration or vehicles did not modify cell viability (basal: 100.0 ± 7.8%; MM: 90.0 ± 5.6%; MLA:104.1 ± 5.0%; Lut: 103.1 ± 10.4%; dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): 94.6 ± 6.5%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3).

Figure 2: Viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. Concentration-response curves of nicotine (Nic) on: (A) cell viability and (B) percentage of MDA-MB-231 viable cells. ***p < 0.001 vs. control considered as 100%. (C) Effect of Nic [1 nM (1 × 10−9 M) to 100 nM (1 × 10−7 M)] on cell viability in the presence or absence of 1 μM of nicotinic antagonists: mecamylamine (MM) [non-selective for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)], methyllycaconitine (MLA) (selective for α7 nAChRs), and luteolin (Lut) (selective for α9 nAChRs). One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. Nic. Values are expressed as the mean±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate

3.2 Metronomic Chemotherapy with Paclitaxel Plus Carbachol of MDA-MB-231 Cells in the Presence of Nicotine

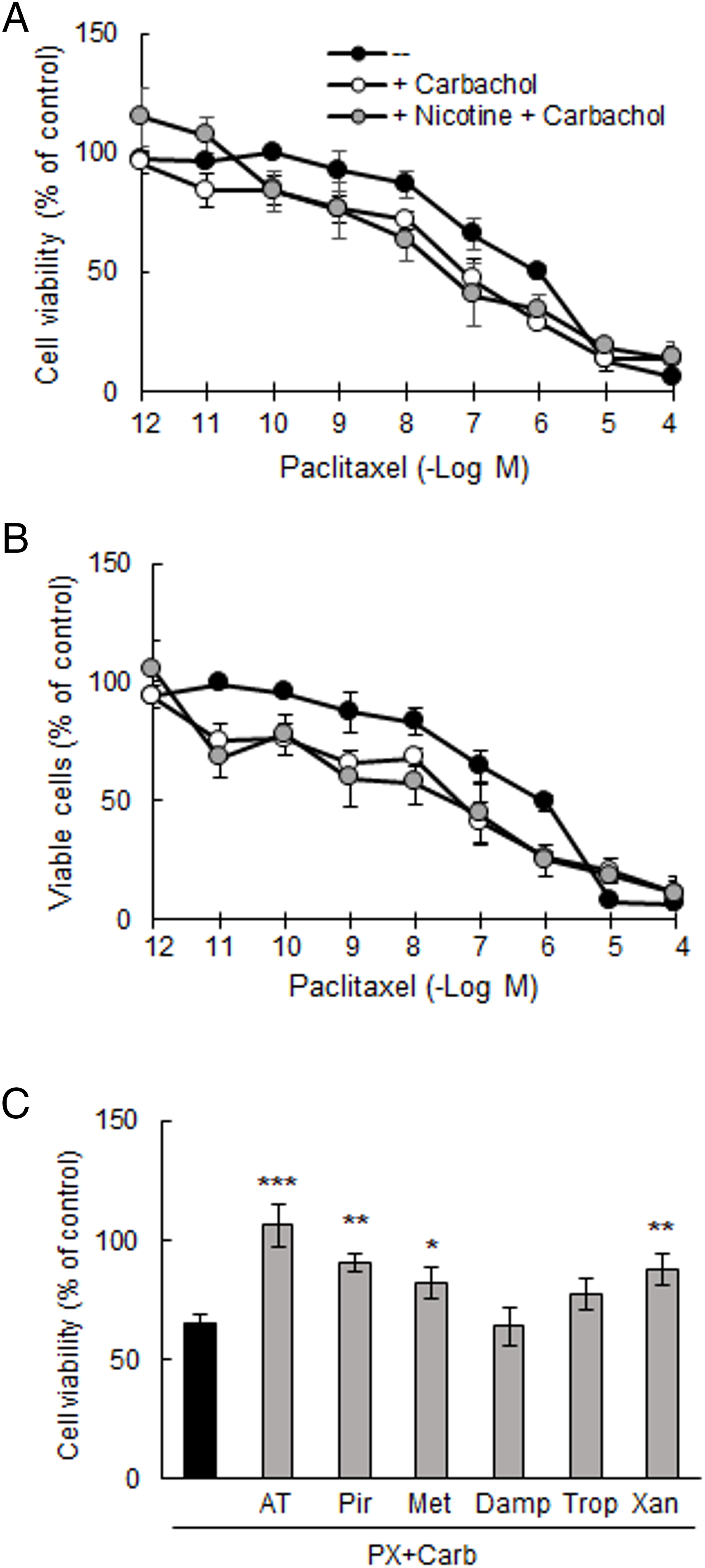

To investigate the effect of Nic on the efficacy of our metronomic chemotherapy, we first confirmed that PX reduces cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). The effect of PX was significant at concentrations equal to or greater than 10 nM (EC50: 370 nM), consistent with our previous findings [19]. We next determined that the addition of the EC25 of Carb (8.6 pM) shifted the concentration-response curve to the left, decreasing the EC50 value by more than one order of magnitude (EC50: 32 nM, p < 0.01 vs. EC50 PX, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3), thereby increasing cell sensitivity to PX treatment. This potentiating effect was also observed in the presence of 100 nM of Nic, a concentration similar to that found in the blood of a smoking patient [38] (EC50: 6.9 nM, p < 0.01 vs. EC50 PX, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3) (Fig. 3A). These results were confirmed by analyzing the percentage of living cells by the trypan blue exclusion assay, which yielded values similar to those obtained with the MTT assay (Fig. 3B). To confirm the efficacy of the PX + Carb combination, we investigated the effect of treatment with either PX or Carb alone. The viability of cells pretreated with 100 nM Nic remained unchanged both in the absence and presence of PX or Carb (Nic: 157.6 ± 8.6%; Nic + PX: 147.5 ± 3.4%; Nic + Carb: 152.5 ± 3.5%, p > 0.05 vs. Nic, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3).

Figure 3: Viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Concentration-response curves of paclitaxel (PX) on (A) cell viability and (B) percentage of viable cells, in the presence or absence of carbachol (Carb) (8.6 pM) alone or in combination with nicotine (100 nM). (C) Effect of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX + Carb (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) on cell viability in the presence or absence of 1 μM of muscarinic antagonists: atropine (AT) [non-selective for muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs)], pirenzepine (Pir) [selective for M1 mAChRs], methoctramine (Met) [selective for M2 mAChRs], diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine (Damp) [selective for M3 mAChRs], tropicamide (Trop) [selective for M4 mAChRs)] or xanomeline (Xan) [selective for M5 mAChRs]. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. PX with Carb. Values are expressed as the mean±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate. n = 4

In the next set of experiments, we analyzed the involvement of mAChRs in the effects of metronomic chemotherapy on MDA-MB-231 cells. This treatment consisted of three 48-h drug cycles, each separated by a 24-h drug-free period, using the minimally effective concentration of PX (10 nM) in combination with the EC25 of Carb (8.6 pM) (PX with Carb). As previously described, MDA-MB-231 cells basally express the M1, M2, M4 and M5 mAChR subtypes [19]. The inhibitory effects on cell viability induced by this metronomic chemotherapy (65.0 ± 3.8%) were reduced only by pre-treatment of cells for 30 min with 1 μM of the following muscarinic antagonists: AT (non-selective; 106.3 ± 9.0%, p < 0.001), Pir (M1 mAChR selective; 90.7 ± 4.2%, p < 0.01), Met (M2 mAChR selective; 82.3 ± 6.7%, p < 0.05) and Xan (M5 mAChR selective; 87.6 ± 6.6%, p < 0.01), indicating that the M1, M2 and M5 mAChR subtypes are involved in mediating this response (Fig. 3C). The muscarinic antagonists alone at this concentration did not modify cell viability (basal: 100.0 ± 10.7%; AT: 93.1 ± 3.9%; Pir: 103.1 ± 1.9%; Met: 101.6 ± 1.9%, Damp: 109.8 ± 4.1%; Trop: 103.7 ± 6.0%; Xan: 102.1 ± 6.3%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3).

Finally, we confirmed that metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb at these concentrations did not affect the viability of the non-tumorigenic mammary cell line MCF-10A (control: 100.0 ± 10.5%; metronomic chemotherapy: 104.3 ± 8.4%, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 4).

3.3 Signal Transduction Pathways Involved in the Effect of Metronomic Chemotherapy on Nicotine-Treated Tumor Cells

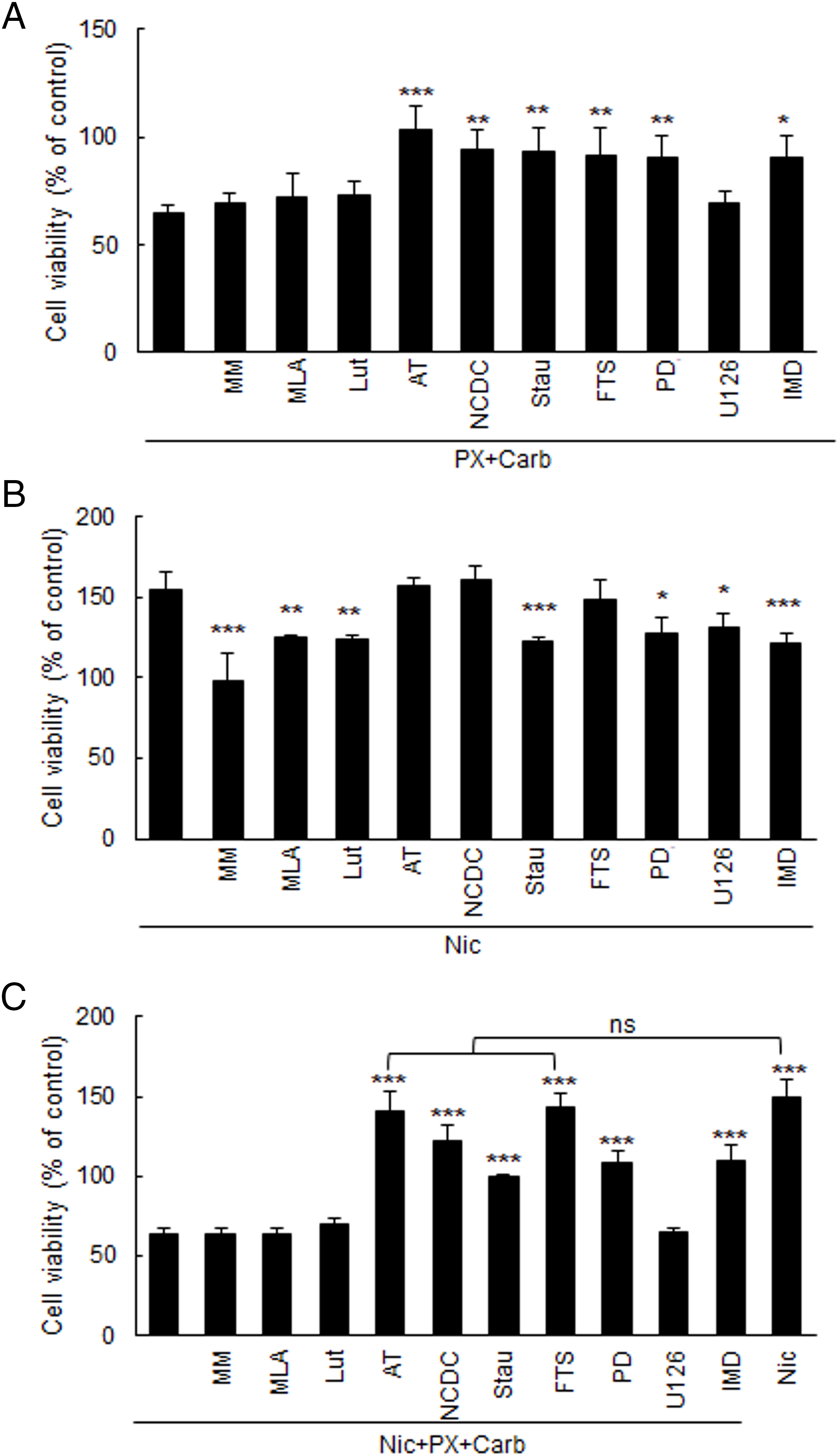

Given that mAChR activation plays a role in the inhibitory response induced by the metronomic chemotherapy and considering that both Carb and PX can activate mAChRs [20], we decided to study several typical mediators of muscarinic signaling pathways. By using several specific inhibitors added 30 min previously, we observed that the inhibitory effect of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb on MDA-MB-231 cell viability (65.0 ± 3.8%) is mediated, at least in part, by PLC (94.4 ± 8.8%, p < 0.01), PKC (93.5 ± 10.5%%, p < 0.01), Ras (91.8 ± 12.3%%, p < 0.01), MEK (90.9 ± 10.0%%, p < 0.01) and IKKβ (90.0 ± 11.0%, p < 0.05). IKKβ is a necessary mediator in the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway [39] (Fig. 4A) (one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 4).

Figure 4: Effect of metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (carb) and/or nicotine (Nic) on the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with (A) PX combined with Carb (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively), (B) Nic (100 nM) or (C) Nic + PX with Carb, and the mediators were evaluated in the presence or absence of 1 μM of nicotinic antagonists: mecamylamine (MM) [non-selective for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)], methyllycaconitine (MLA) (selective for α7 nAChRs), or luteolin (Lut) (selective for α9 nAChRs); the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT, 1 μM); an inhibitor for phospholipase C (PLC) [4-carboxyphenyl-N, N-diphenylcarbamate (NCDC), 5 μM], or the kinase inhibitors for: PKC [staurosporine (Stau), 10 nM], Ras [S-trans, trans farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), 1 μM], MEK [PD098059 (PD), 10 μM], ERK1/2 (U126, 10 μM) or IKKβ [IMD354 (IMD), 50 nM]. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. A) PX with Carb, B) Nic or C) Nic + PX with Carb, respectively. ns: not significant. Values are expressed as the mean±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate. n = 4

To further understand the role of Nic in modulating the response to our metronomic chemotherapy, we first examined the signaling pathways involved in its stimulatory effect on cell viability (154.7 ± 11.1%). We observed the participation of PKC (122.2 ± 3.0%, p < 0.001), MEK (149.9 ± 11.8%, p < 0.05), ERK1/2 (130.7 ± 8.5 5, p < 0.05) and IKKβ (121.2 ± 6.8%, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 4) since the addition of their specific inhibitors (Stau, PD, U126 and IMD, respectively) for 30 min reduced the effect of Nic (Fig. 4B).

Additionally, the presence of 100 nM of Nic during the metronomic chemotherapy treatment did not modify its effect (Nic + PX + Carb: 63.3 ± 4.1%, p > 0.05 vs. PX + Carb, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 4) and all previous identified mediators (Fig. 4A) remained relevant. This was confirmed by pretreatment with their specific inhibitors, which modulated the effects observed (Fig. 4C). Specifically, when we inhibited mAChR (140.2 ± 12.9%) or Ras (142.8 ± 9.6%), cell viability increased to values similar to those obtained with treatment with Nic alone (148.8 ± 12.2%). Furthermore, inhibition of PKC, MEK or IKKβ restored cell viability to control levels (99.1 ± 1.44%, 108.9 ± 6.3% and 110. 0 ± 2.5%, respectively) (Fig. 4C). Results confirmed that none of the inhibitors alone at these concentrations modified cell viability (basal: 100.0 ± 5.4%; NCDC: 100.9 ± 2.2%; Stau: 98.0 ± 1.3%; FTS: 96.2 ± 5.4%; PD: 99.4 ± 6.7%; U126: 104.2 ± 12.3%; IMD: 105.3 ± 5.5%, DMSO: 94.6 ± 6.5%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3).

3.4 Participation of Nitric Oxide Synthase in the Effect of Metronomic Chemotherapy on Nicotine-Treated Tumor Cells

Since mAChR signaling pathways are involved in the actions of metronomic chemotherapy, both in the absence and presence of Nic treatment, we next decided to evaluate the role of NOS, a classical muscarinic mediator, whose product can modulate tumor biology.

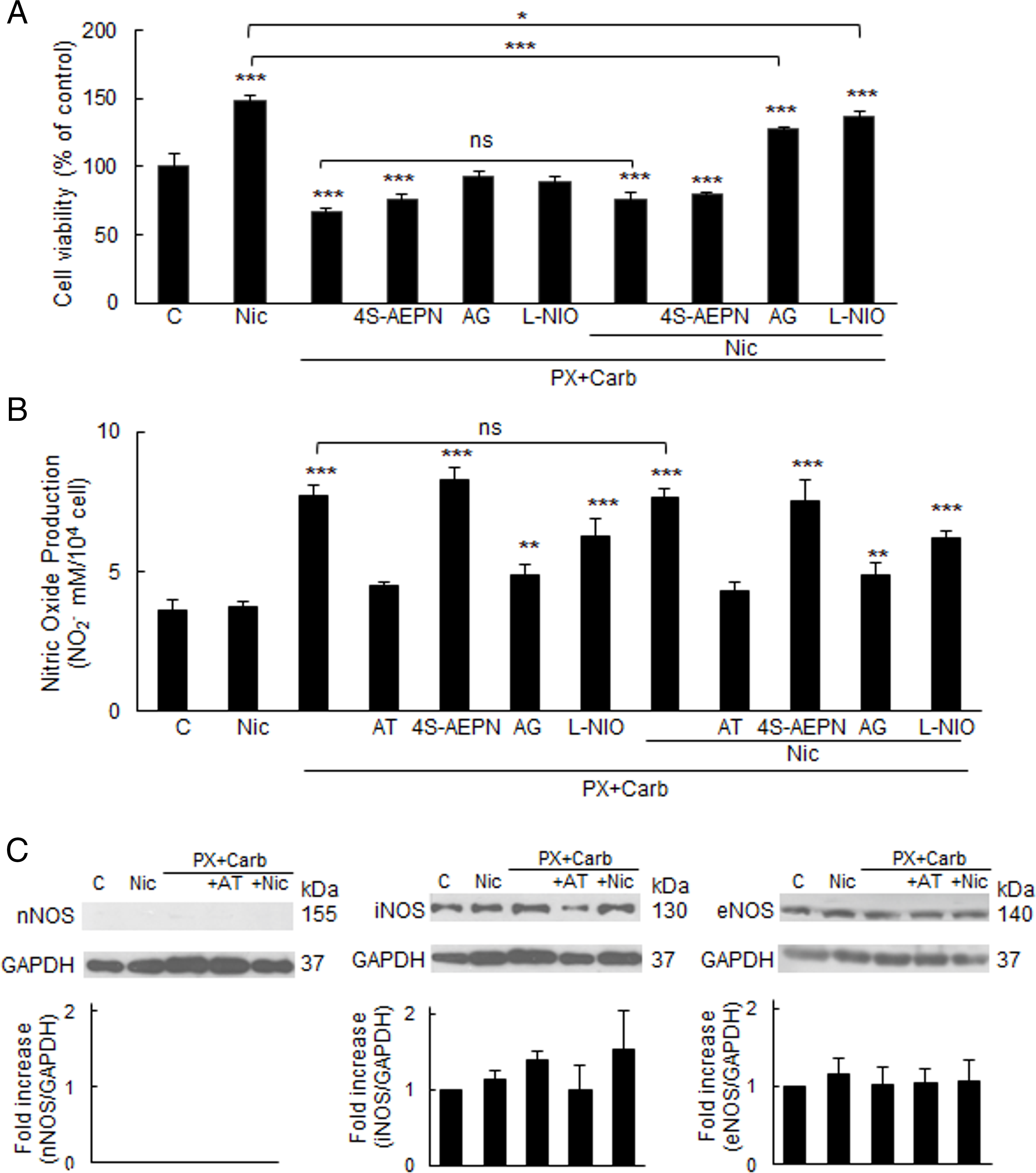

We found that the inhibitory effect of the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb on cell viability is mediated by the activation of the iNOS and eNOS isoforms, the only NOS isoforms expressed in these cells (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment with their respective selective inhibitors for 30 min reversed the effects of the metronomic chemotherapy (AG + PX + Carb: 92.5 ± 3.8%; L-NIO + PX + Carb: 89.6 ± 2.6%) (Fig. 5A), confirming their involvement. In the presence of Nic, inhibition of either iNOS or eNOS shifted cell viability to intermediate values (127.4 ± 1.2% and 136.9 ± 4.2%, respectively) between those determined with the metronomic chemotherapy alone (67.4 ± 1.8%) and Nic treatment (148.0 ± 4.1%) (Fig. 5A), indicating that both NOS isoforms contribute to the effect of the metronomic chemotherapy.

Figure 5: Participation of the phospholipase C/nitric oxide synthase pathway in the effect of metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) on MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Cell viability and (B) nitric oxide (NO) production in cells treated with PX combined with Carb (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) and/or nicotine (Nic) (100 nM) in the presence or absence of the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT, 1 μM) or the inhibitors for nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms: nNOS (4S-AEPN, 5 μM), iNOS [aminoguanidine (AG, 1 mM)] or eNOS [L-N5-(1-iminoethyl) ornithine (L-NIO, 10 μM)]. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. control or that indicated. ns: not significant. n = 4. Values are expressed as the mean ±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Western blot assay to detect NOS isoforms in cells treated with PX and Carb in the presence or absence of Nic and/or AT. Molecular weights are shown on the right. Densitometric analysis of the bands is expressed as fold increase units relative to the expression of control. One representative experiment of three is shown

Given that nitric oxide (NO), which is one of the products of NOS activity, can induce apoptosis at high concentrations, we next analyzed NO levels. Chronic Nic treatment did not significantly modify the basal NO levels in MDA-MB-231 cells (basal: 3.6 ± 0.3 μM; Nic: 3.7 ± 0.1 μM, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 4). However, the metronomic chemotherapy induced a significant increase in NO levels (7.7 ± 0.3 μM), which was reduced by pretreatment for 30 min with the iNOS or eNOS inhibitors both in the absence (4.8 ± 0.3 μM and 6.2 ± 0.6 μM, respectively) and presence of Nic (4.8 ± 0.4 μM and 6.2 ± 0.2 μM, respectively) (Fig. 5B).

This increase in NO levels was at least partially attributed to an increase in iNOS expression induced by the metronomic chemotherapy, observed both in the absence and presence of Nic. In contrast, the expression of eNOS, the other NOS isoform expressed in MDA-MB-231 cells, remained unchanged across all treatments (Fig. 5C). The NOS inhibitors alone, at the concentrations tested, did not modify cell viability (basal: 100.0 ± 9.6%; 4S-AEPN: 108.2 ± 11.1%; AG: 108.4 ± 6.6%; L-NIO: 105.0 ± 9.1%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 4) or NO levels (basal: 3.6 ± 0.3 μM; 4S-AEPN: 3.9 ± 0.4 μM; AG: 4.1 ± 0.5 μM; L-NIO: 3.5 ± 0.2 μM, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 4).

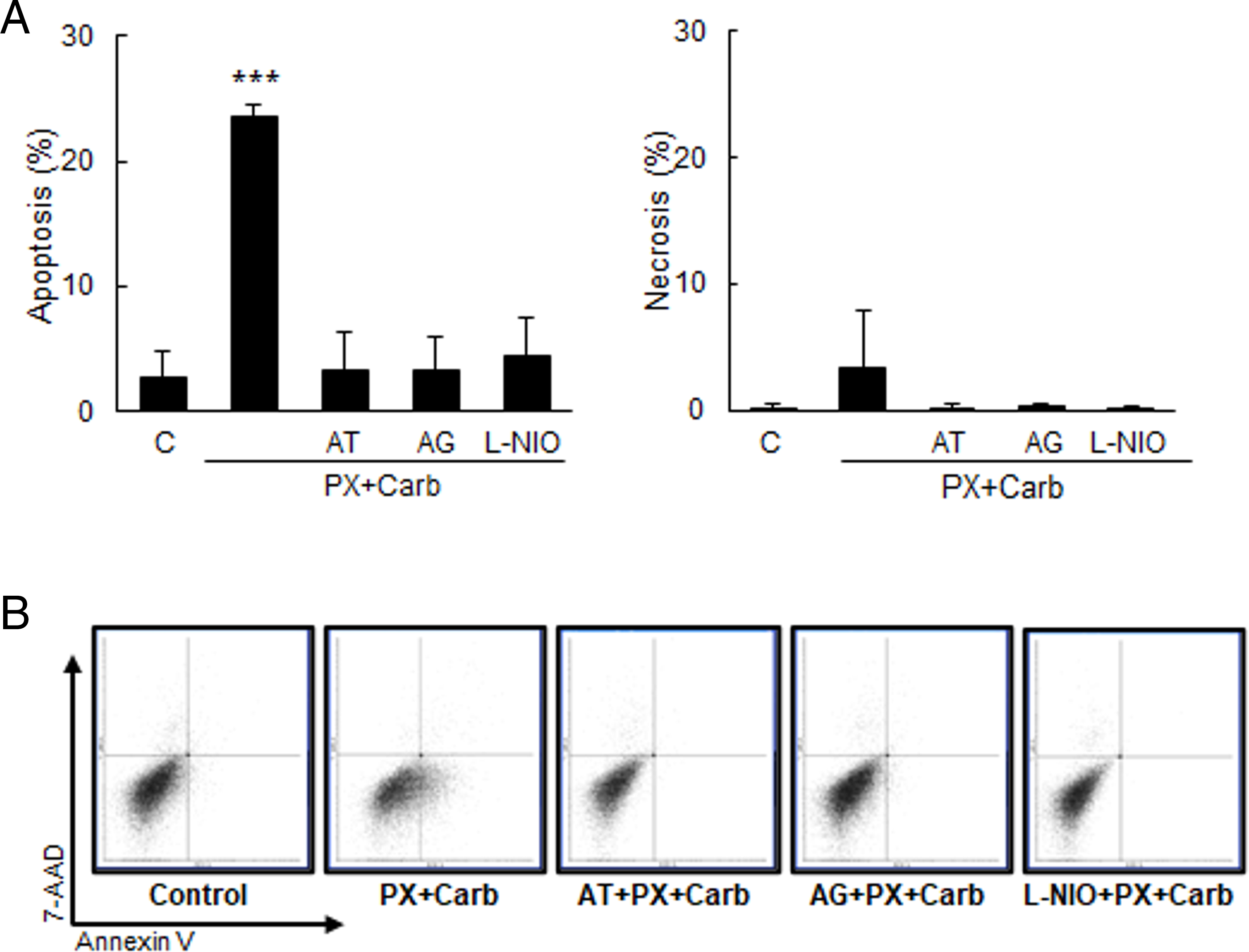

Since the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb induced an increase in NO levels (Fig. 5B), and given that several authors have reported that high levels of this free radical exert pro-apoptotic effects, we proceeded to evaluate apoptosis levels. Our metronomic chemotherapy protocol significantly increased cell apoptosis (basal: 2.8 ± 1.9%; PX + Carb: 23.4 ± 1.0%, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 3). This effect that was reversed by pretreatment for 30 min with the mAChR antagonist AT (3.3 ± 2.9%), or with the selective iNOS and eNOS inhibitors (AG, 3.2 ± 2.6% and L-NIO, 1.4 ± 3.1%, respectively). In contrast, necrosis levels were not significantly modified by any of the treatments evaluated (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 3) (Fig. 6). AT, AG or L-NIO alone, at the concentrations used, did not modify apoptosis (basal: 2.8 ± 1.9%; AT: 4.4 ± 4.3%; AG: 4.3 ± 4.9%; L-NIO: 5.3 ± 2.6%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 3) or necrosis levels (basal: 0.2 ± 0.2%; AT: 0.5 ± 0.6%; AG: 0.3 ± 0.3%; L-NIO: 0.3 ± 0.4%, all p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3).

Figure 6: MDA-MB-231 apoptosis/necrosis levels. (A) Percentage of apoptotic (left) or necrotic (right) cells treated with metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT, 1 μM) or the inhibitors for nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms: iNOS [aminoguanidine (AG, 1 mM)] or eNOS [L-N5-(1-iminoethyl) ornithine (L-NIO, 10 μM)]. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. ***p < 0.001 vs. control. n = 3. The percentages of the lower right quadrants correspond to apoptotic cells, whereas those of the upper left quadrants correspond to necrotic cells. Values are expressed as the mean±SD from independent triplicate experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Dot plots representative of the different treatments are shown

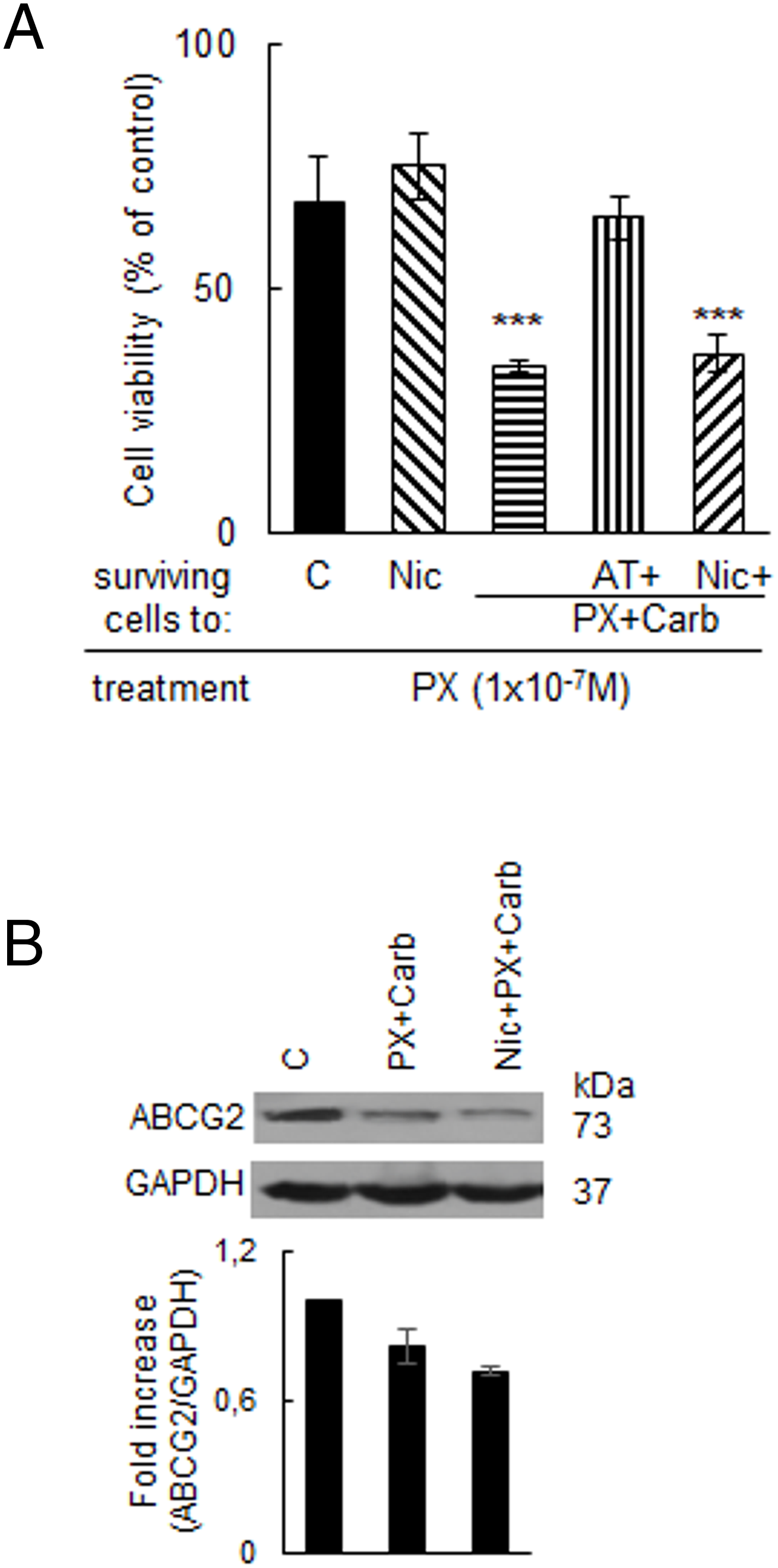

In antitumor therapy, the potential of a treatment to be used as a neoadjuvant that increases sensitivity to chemotherapy is a desirable characteristic. Thus, we then sought to determine whether the metronomic chemotherapy could modulate the sensitivity of surviving MDA-MB-231 cells to subsequent PX treatment. We confirmed that the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb increased the sensitivity of residual cells to a new therapeutic cycle of PX (100 nM) (basal: 67.5 ± 9.2%; PX + Carb: 34.2 ± 1.1%, p < 0.001 vs. cells without treatment, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 4) both in the absence and presence of Nic (36.5 ± 3.7%) (Fig. 7A). AT alone, at the concentration used, did not modify chemotherapy sensitivity of residual cells (basal: 67.5 ± 9.2%; AT: 64.3 ± 2.5%, p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 4).

Figure 7: Chemotherapy sensitivity of residual MDA-MB-231 cells after treatments. (A) Sensitivity to paclitaxel (PX, 100 nM) of residual cells treated with nicotine (Nic, 100 nM) or metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT, 1 μM) or Nic (100 nM). Values are expressed as the mean ±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. ***p < 0.001 vs. control. n = 4. (B) Expression of the ATP binding cassette G2 (ABCG2) transporter in MDA-MB-231 cells. ABCG2 expression was analyzed by Western blot. Cells were treated with metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of Nic (100 nM). Molecular weights are indicated on the right. The densitometric analysis of the bands is expressed as fold increase units relative to the expression of controls. One representative experiment of three is shown. n = 3

Given that the sensitivity to PX is modulated by the expression of the ABCG2 efflux pump, we also evaluated ABCG2 protein levels. Results confirmed that MDA-MB-231 cells basally express ABCG2, and that treatment with the metronomic chemotherapy decreased its expression, both in the absence and presence of Nic (17.9 ± 6.5% and 28.1 ± 1.3% of decrease, respectively) (Fig. 7B).

3.5 Metronomic Chemotherapy Modulation of Cancer Stem Cells

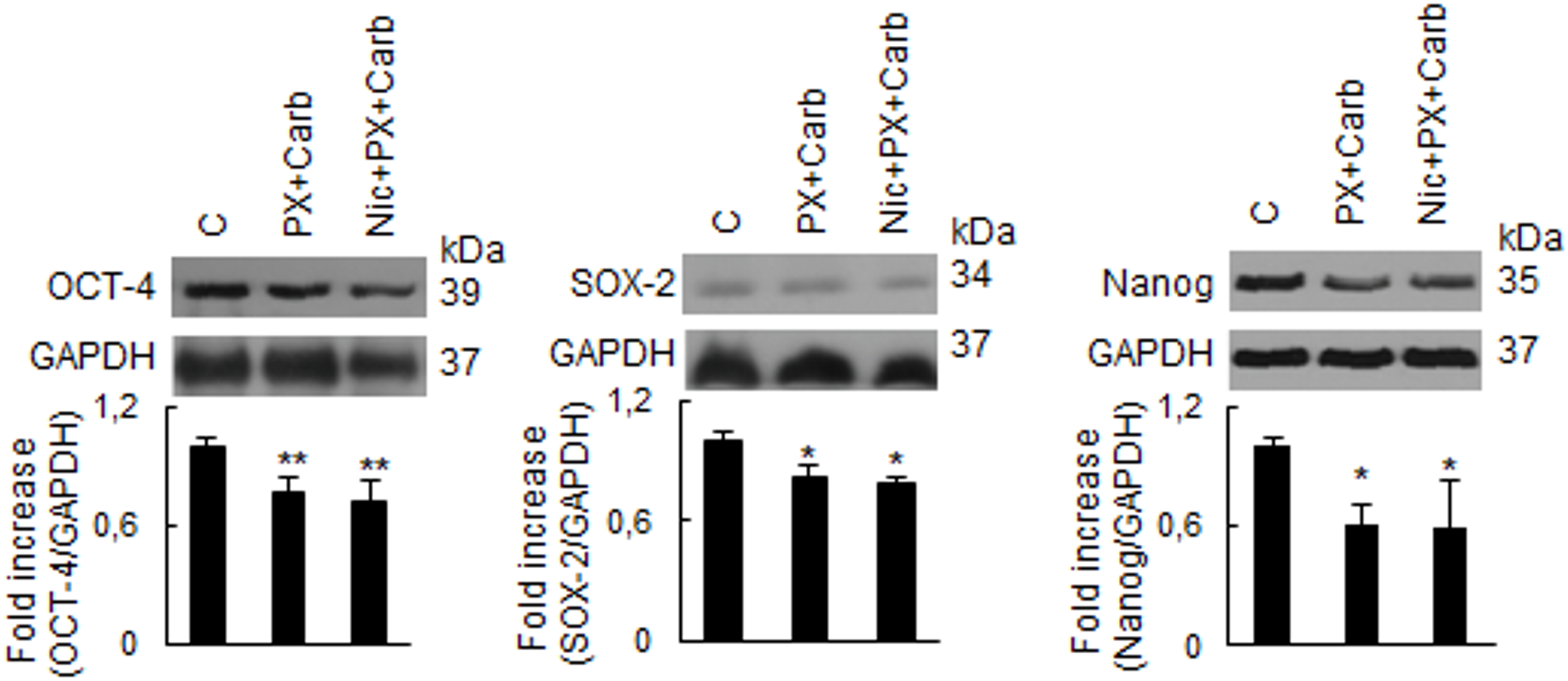

Since metronomic chemotherapy targeting tyrosine kinases has been shown to modulate the expression of CSC stemness markers, including Nanog [40], and given that the effects of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb were mediated by the activation of several kinases (Fig. 4), we next investigated the expression of the stemness-related proteins OCT-4, SOX-2 and Nanog. As shown in Fig. 8, treatment with our metronomic chemotherapy regimen induced a significant decrease in the expression of all three proteins, both in the absence (SOX-2: 17.8 ± 5.1%, OCT-4: 22.9 ± 8.2%; Nanog: 38.9 ± 10.1%, n = 3) and presence of Nic (SOX-2: 20.8 ± 2.8%, OCT-4: 28.1 ± 10.9%; Nanog: 40.6 ± 23.5%, n = 3). These effects were not significantly modified in the presence of Nic (p > 0.05 vs. PX + Carb, n = 3).

Figure 8: Expression of stemness proteins in MDA-MB-231 cells. The expression of OCT-4, SOX-2 and Nanog was analyzed by Western blot. Cells were treated with a metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence and absence of nicotine (Nic) (100 nM). Molecular weights are indicated on the right. The densitometric analysis of the bands is expressed as fold increase units relative to the expression of controls. One representative experiment of three is shown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs. control (C), n = 3

Since our metronomic chemotherapy modulated the stemness proteins that characterize CSC (Figs. 7B and 8), we also decided to determine the proportion of this subpopulation. Given that the MDA-MB-231 cell line harbors a CSC subpopulation [41], and that individual CSC are capable of generating mammospheres under non-adherent conditions [42], we used both approaches to evaluate whether our metronomic chemotherapy modulates the proportion of CSC.

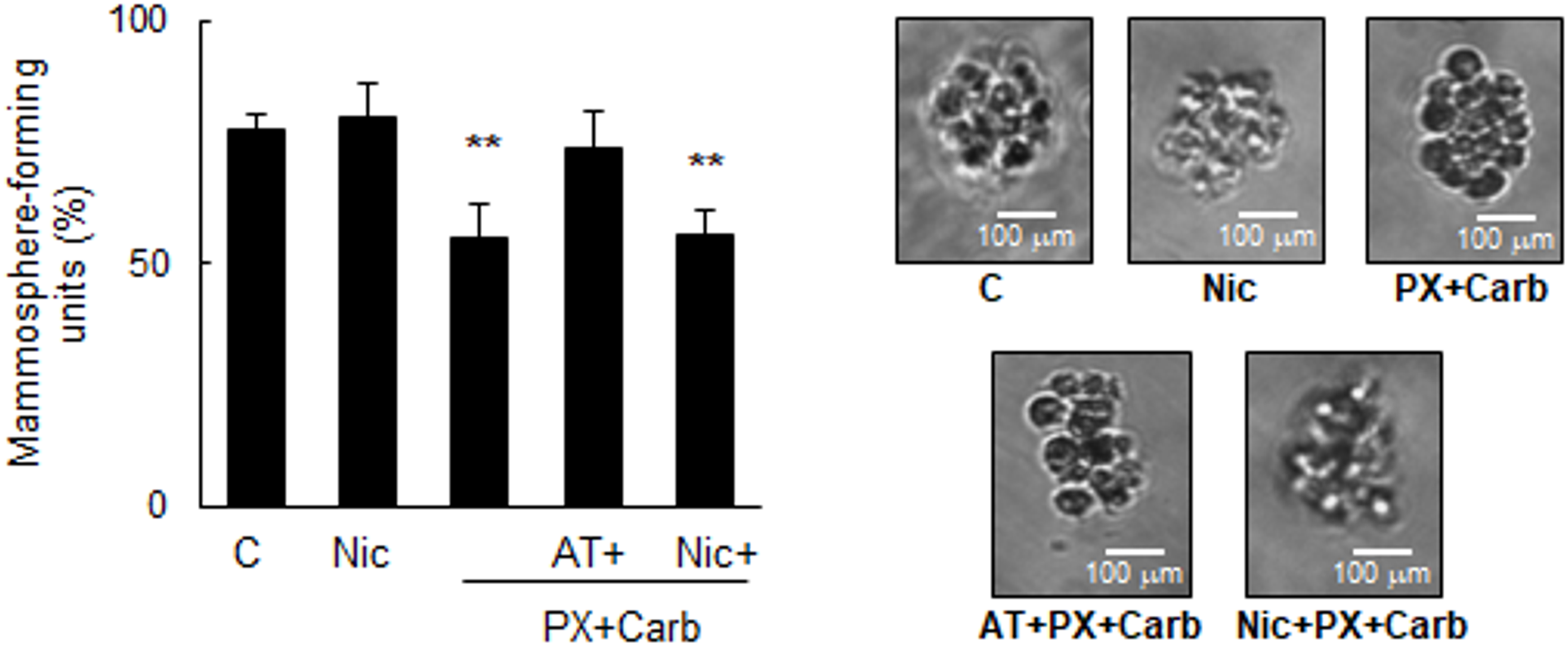

By using an ELDA, we determined that our metronomic chemotherapy reduced the mammosphere-forming ability (basal: 77.5 ± 3.0%) both in the absence (55.5 ± 6.6%) and presence of Nic (56.1 ± 4.8%), suggesting a lower proportion of CSC compared to controls. This effect was reversed by pretreatment for 30 min with AT (74.0 ± 7.2%). No significant differences were observed in mammosphere morphology or size across the treatments studied (Fig. 9). AT alone, at the concentration used, did not modify mammosphere formation (basal: 77.5 ± 3.0%, AT: 81.9 ± 3.4%, p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 3).

Figure 9: Mammosphere formation assays. A) Quantification of mammosphere-forming units in MDA-MB-231 cells (ELDA) treated with nicotine (Nic) (100 nM) or metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT) (1 μM) or Nic (100 nM). Values are expressed as the mean ±SD from independent quadruplicate experiments performed in duplicate. One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. **p < 0.01 vs. n = 4. Control. B) Representative images of mammospheres obtained from treated MDA-MB-231 cells (scale bar: 100 μm)

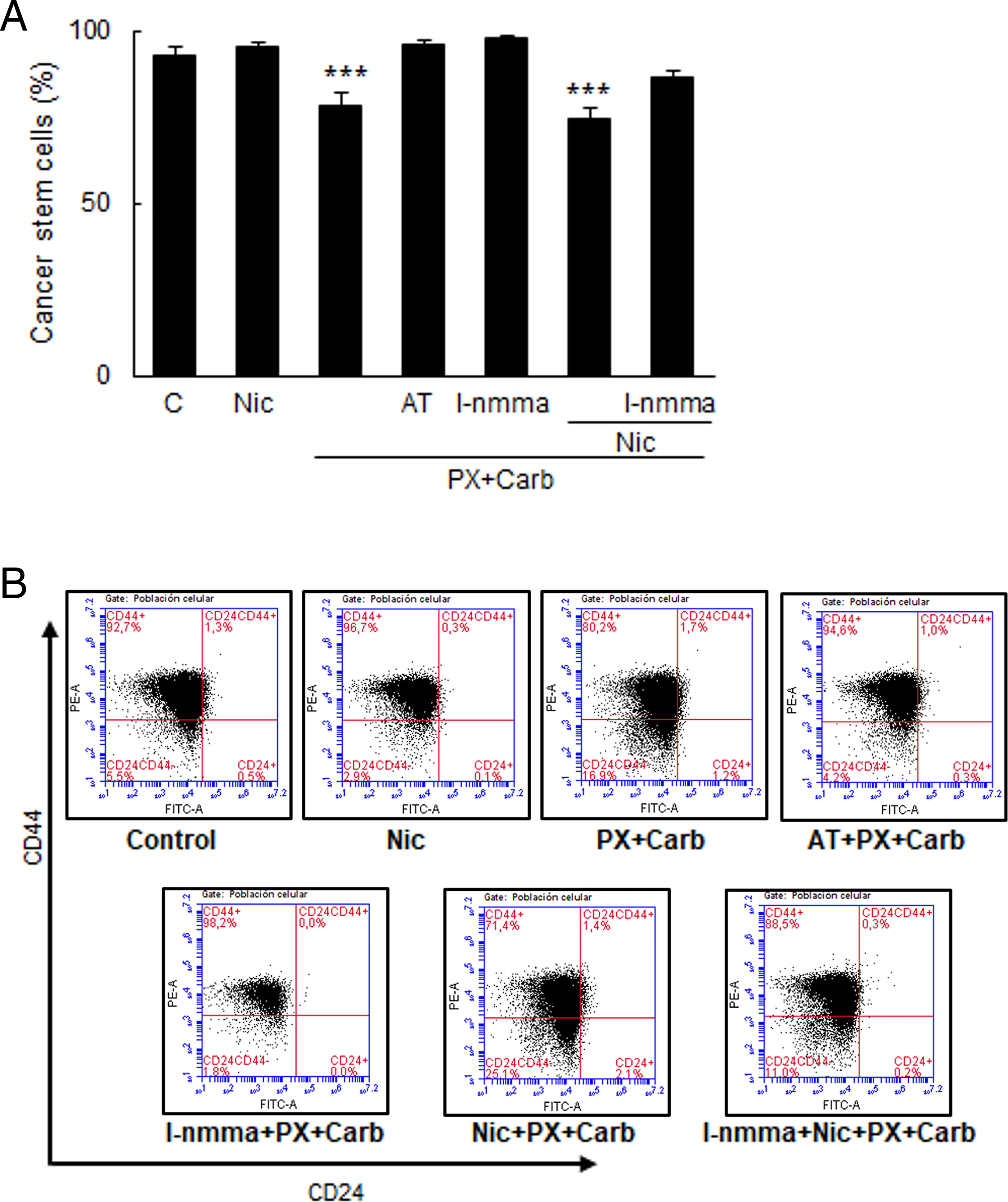

Finally, since results showed that the metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb decreased both the expression of stemness markers and mammosphere-forming units, we studied whether the proportion of CSC determined by the expression of the surface markers CD44 and CD24 were modified. Fig. 10 shows that these cells basally present 92.8 ± 2.1% of CSC, and that this value decreased in residual cells after our metronomic chemotherapy treatment in the absence (78.0 ± 4.0%, p < 0.001) and presence of Nic (74.6 ± 2.8%, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test, n = 3). This effect of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb was mediated by NOS activation as pretreatment with the non-selective NOS inhibitor l-nmma reversed the observed effect (l-nmma + PX + Carb: 98.1 ± 0.5%; l-nmma + Nic + PX + Carb: 86.6 ± 1.6%, both p > 0.05 vs. basal, one-way ANOVA and Tukey test, n = 3). Results confirmed that this modification in the proportion of CSC was due to the activation of mAChRs since the pretreatment with the muscarinic antagonist AT reversed the effect of the metronomic chemotherapy (96.0 ± 1.2%) (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Levels of MDA-MB-231 cancer stem cells. (A) Percentage of cancer stem cells (CSC) in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with nicotine (Nic) (100 nM) or metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of the muscarinic antagonist atropine (AT) (1 μM), non-selective NOS inhibitor NGmonomethyl-L arginine (l-nmma) (100 μM) or Nic (100 nM). One-way ANOVA and supplementary Tukey test were performed. ***p < 0.001 vs. control. n = 3. The percentages of the upper left quadrants correspond to CD44+/CD24− cells corresponding to CSC. Values are expressed as the mean ±SD from independent triplicate experiments. (B) Dot plots representative of the different treatments are shown

Previously, we described that, in different types of breast tumor cells, metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb was as effective as conventional chemotherapy based on the administration of high doses of PX [19,43]. These previous results showed that, unlike conventional therapy, which has low specificity, the metronomic chemotherapy was selective only for breast tumor cells [19,43]. In addition, we described that the efficacy of conventional chemotherapy with PX could be negatively modulated by the action of Nic, which could lead to a poor prognosis for the patient [25]. However, no previous publications have described the action of Nic treatment on the efficacy of the metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb or its signaling pathways.

In our previous studies, we also determined that breast tumor cells express α7 and α9 nAChRs, which are functional in response to Nic stimulation for short time periods [25]. However, there is no evidence of a chronic effect of this nicotinic agonist on these cells. Several authors have described that chronic treatment with Nic induces the proliferation of lung [44], kidney [45], heart [46], brain [47] and breast [48] cancer cells. In the present study, we determined that MDA-MB-231 cells responded to chronic Nic administration by increasing their cell viability, with a significant effect observed only in the concentration range of 1 to 100 nM (Fig. 2). These results are in agreement with those described by other authors in lung tumor cells [49] and mammary tumor cells [50]. Previous publications have described the expression of α7 and α9 nAChRs in human breast tissue [51,52], and we have also previously described the expression of these nAChR subtypes in MDA-MB-231 cells [25]. In the present study, we determined that the stimulatory effect of Nic on cell viability was mediated by the activation of the α7 and α9 nAChR subtypes, since pretreatment with their selective antagonists reduced the nicotinic effect. These results are similar to those obtained by Oz et al. [53] and Liao et al. [54], who determined the participation of both nAChR subtypes in the chronic effect of Nic on breast tumor cell viability.

Although we have previously demonstrated that treatment with low concentrations of Nic for 48 h induces a decrease in the efficacy of traditional chemotherapy in breast cancer [25], there is no evidence of the effect of chronically administered Nic on metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb. Therefore, we first confirmed that these cells were sensitive to metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb, as previously described [19,25]. As expected, results confirmed that the treatment reduced the viability of these cells in a PX concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3), in line with that previously described by several authors [19,55,56]. Previously, we also determined that the metronomic combination of muscarinic agonists with PX is effective as antitumor therapy in breast tumor cells [19]. Here, we confirmed that the presence of the EC25 of Carb increased the potency of PX by more than one order of magnitude. We also confirmed that this effect was selective to tumor cells, since non-tumorigenic breast cells did not express mAChRs, which are necessary targets for the action of our metronomic chemotherapy [19]. Although the target of PX has been historically defined to be the tubulin/microtubule system, this depends on the concentration at which it is administered. Previously, we and other authors have shown that low concentrations of PX can block mitosis at the metaphase/anaphase transition without affecting the cytoskeleton, increasing cell apoptosis by mAChR activation [20,57].

Since previous studies have shown that Nic decreases the efficacy of different antitumor therapies [25,28,58,59], it is relevant to highlight that the antitumor efficacy of the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb was not affected by the chronic presence of Nic at a concentration similar to that found in the blood of smoking patients (100 nM) [38].

Our present results showed that the effect of the metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb was mediated by the activation of the mAChR subtypes M1, M2 and M5 since pretreatment with their selective antagonists reduced the effect. Although we have previously described, through the use of non-selective muscarinic antagonists, that metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb exerts its antitumor effect mainly through the activation of mAChRs [19,25,60], in this study, we identified, for the first time, the mAChR subtypes involved. Although the activation of M1 and M5 mAChRs is typically associated with increased cell proliferation, when the treatment time with the non-selective muscarinic agonist is prolonged (greater than 6 h), an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation can be observed [20]. Previous results from us and others have shown that the inhibition of cell viability is mediated by the activation of the M1 [61], M2 [19,62] and M4 mAChR subtypes [63]. However, this is the first study to show that M5 mAChR activation induced a decrease in cell viability.

Although the mechanism by which M5 mAChR activation exerts its inhibitory effect on cell viability is unknown, it may be similar to that described in Chinese hamster ovary cells by Shafer et al. [64], who showed that M3 mAChR activation could induce the inhibition of proliferation via Rac1 activation. Given the similar structure and signaling pathways involved in the activation of the M3 and M5 mAChR subtypes, it is possible that something similar may occur in our model. Since the results of cell viability and viable cells presented similar values (Figs. 2 and 3), it is reasonable to conclude that the treatments studied really modulated cell proliferation.

After having demonstrated the efficacy of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb in MDA-MB-231 cells chronically treated with Nic, we decided to investigate the mediators involved. Since the effects of both PX at low doses and the muscarinic agonist Carb are mediated by mAChR activation [20], we decided to investigate the involvement of mediators classically associated with activation of the muscarinic pathway. Furthermore, given that protein kinases are common mediators in the activation of nicotinic [65], muscarinic [66] and PX [25] effects, we also decided to investigate the involvement of these mediators in the effect of our metronomic chemotherapy.

A classical mediator of M1, M3 and M5 mAChR activation is PLC, which hydrolyzes membrane lipids, to produce inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol [67]. By using specific inhibitors, here we determined the participation of PLC in the effects of our metronomic chemotherapy. This mediator plays a key role in regulating intracellular calcium levels necessary for activating different calcium-dependent proteins that can modulate cell proliferation, such as PKC [68]. Here, through the use of a specific inhibitor, we also demonstrated the participation of PKC in mAChR activation induced by metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb. Several authors have shown that the short-term activation of mAChRs (less than 6 h) leads to cell proliferation via the PKC-Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK-NF-κB kinase signaling pathway [69–72]. However, when the mAChR activation time is prolonged, as occurs with metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb, cell viability is significantly inhibited through a PKC-dependent pathway. To date, only Sundel et al. [61] described that, in human colon cancer cells, prolonged activation of M1 mAChR inhibits proliferation through a protein kinase-dependent pathway, similarly to that here described.

In agreement with our findings, several other authors have described the participation of different protein kinases such as PKC [73], Ras [74] and MEK [75] in the inhibitory effect on cell viability, although these effects occurred independently of the mAChR pathway. Here we describe, for the first time, a decrease in cell viability by the activation of these protein kinases mediated through a mAChR-dependent pathway. Additionally, several authors have described that mAChR activation can modulate NF-κB pathways [76,77]. In this study, we demonstrated the involvement of NF-κB in the effects of the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb, probably through the participation of the protein kinase pathway. Similar results have been described by Wen et al. [78] and Engin [79], who indicated that protein kinases are capable of activating the NF-κB pathway, altering the expressions of several proteins, and thereby modulating cell viability.

When we studied the mediators involved in the stimulating effect of Nic on cell viability, we observed the participation of several mediators also involved in muscarinic activation by our metronomic chemotherapy, which inhibits cell viability. This apparent contradiction observed with PKC, MEK, and the NF-κB pathway can be explained by the results described previously.

In this sense, several authors have described that the PKCδ isoform is capable of either inducing or inhibiting cell proliferation and apoptosis in the same cell type depending on the signaling pathways that are activated. This may be occurring in our study model with a stimulating nicotinic pathway and an inhibitory muscarinic pathway of cell viability [73,80,81]. Regarding the MEK protein, seven isoforms have been described, and while the activation of some isoforms induces cell proliferation, the activation of others induces apoptosis [75]. These results agree with those obtained by Huth et al. [82], who described that, in MDA-MB-231 cells, MEK2 and MEK1 isoforms exhibit antagonistic effects on cell proliferation, inducing and inhibiting it, respectively. Since we used nonspecific targeting of MEK isoforms [83], it is possible that this dichotomy occurred in our model, with MEK1 activated by the muscarinic pathway and MEK2 activated by the nicotinic pathway.

Our results also showed the participation of ERK1/2 in the nicotinic effect on cell viability. These results agree with those obtained by Yang et al. [84], who found that α7 nAChR activation induces an ERK1/2-dependent pathway. Similarly, Liao et al. [54] described similar results but owing to α9 nAChR activation. It is worth nothing that both subtypes have been previously described by us in these cells [25].

By combining the activation of the nicotinic and muscarinic pathways, the latter by our metronomic chemotherapy, we determined a predominance of the muscarinic pathway. In line with this, we determined that the mediators involved in the effect of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb on cell viability were the same in the presence or absence of Nic. Notably, blocking mAChRs or inhibiting Ras in the presence of Nic resulted in complete loss of the activation of the muscarinic pathway by our metronomic chemotherapy, leaving only the nicotinic effect. This was not the case when inhibiting the other muscarinic mediators, where only a reduction in the effect was observed. This suggests that both mAChRs and Ras are specific and primary intermediaries in the effect of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb. In agreement with this, similar results have shown that Ras acts as a main intermediary in non-neuronal muscarinic activation of the M2 [70] and M3 mAChRs [85].

The activation of different protein kinases can activate the NF-κB pathway, modulating cell proliferation [86]. In our model, we determined the participation of the NF-κB pathway in the activation of both the nicotinic and muscarinic pathways. In the former, this would be related to the induction of proliferation and in the latter to the inhibition of proliferation. Our results regarding nicotinic NF-κB interactions resemble those reported by He et al. [87], who described that nicotinic activation of α7 nAChR induces hepatocarcinoma cell proliferation via NF-κB. However, no previous publications have described that muscarinic stimulation inhibits cell viability through an NF-κB-dependent pathway, making our study the first to do so. This signaling pathway could be related to the increase in NOS expression [88], whose product, NO, can inhibit proliferation [89].

We also determined the participation of the iNOS and eNOS isoforms in the effect of our metronomic chemotherapy, which is dependent on the increase in NO levels. These results are consistent with previous studies in murine salivary glands, where muscarinic activation was found to increase NO production [90]. Our present results confirmed that these cells express only the iNOS and eNOS isoforms, with the former showing increased expression in response to metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb. In agreement with our results, several authors have described that MDA-MB-231 cells express only the iNOS and eNOS isoforms [91,92]. Consistent results were obtained in salivary glands by Sterin Borda et al. [93], who described that muscarinic activation increases eNOS expression in a way similar to the one here described. Notably, this is the first study to describe the modulation of NOS isoform expression by metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb.

The type of cell death induced by a particular treatment is not indistinct, and therapies that induce apoptosis are relevant to prevent unregulated inflammation that can induce injury [94]. Some antitumor treatments exert their effects by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [95] and this increase can induce cellular apoptosis [96]. One of the mechanisms by which ROS levels increase in tumor cells is through the induction of NOS protein and its product NO [97]. In the present study, we determined that our metronomic chemotherapy reduced the viability of breast tumor cells, at least in part, through the induction of apoptosis by a NOS-dependent mechanism in the presence or absence of Nic. Although previous results have shown that PX at high concentrations exerts its antitumor effect by increasing apoptosis [20,25,98], this is the first reference to the mechanism of action of the metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb, as well as to the signaling pathways involved. Although this is not the only antitumor therapy that induces apoptosis by increasing NO levels [95,99,100], metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb presents specificity since it requires the presence of mAChRs as therapeutic targets, which are present only in breast tumor tissue, a fact that highlights its therapeutic benefits in breast cancer. Since the main cause of therapeutic failure in breast cancer is resistance to chemotherapy, both the type of cell death and the sensitivity of the residual cells after treatment are relevant in the antitumor therapy [101]. In this sense, conventional chemotherapy with high doses of PX causes significant cell death, but can generate resistance to the cytostatic agent in the residual cells [8]. This effect is caused, at least in part, by the increased expression of multidrug resistance proteins induced by PX, which leads to treatment failure and relapse [102]. In the present study, when we investigated the effect of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb on cells remaining after treatment, we determined an increase in their sensitivity to a new cycle with the cytostatic agent alone both in the absence and presence of Nic. These results highlight the importance of our metronomic chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant to subsequent conventional chemotherapy.

Chemosensitivity can be modulated by several mechanisms. One of the most important is the expression of the multidrug resistance protein ABCG2, also known as breast cancer resistance protein. This transporter rapidly extrudes PX into the extracellular space, reducing its duration of action and efficacy [103]. Previous reports have shown that MDA-MB-231 cells basally express ABCG2 [19,104]. Our present results confirmed this, and also that the metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb decreased ABCG2 expression both in the absence and presence of Nic. A decrease in ABCG2 expression would increase the time necessary for PX to exert its effect inside the cells, enhancing its cytostatic effect [19]. In agreement with our results, studies with other metronomic chemotherapy combinations have also reported a decrease in ABGC2 expression [105–107]. Considering that Nic treatment per se increases ABCG2 expression in breast and head and neck cancer cells [25,108] thereby reducing the effectiveness of conventional chemotherapy with PX, our results highlight the benefit of switching to our metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb.

Furthermore, Nic has been described to reduce the antitumor efficacy of doxorubicin, another chemotherapy drug, by increasing the proportion of CSC [109], which are a cell subpopulation characterized by resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [110]. This cell subpopulation presents an increased expression of ABCG2 transporter [111], which is considered a marker of CSC [112,113].

In the present study, we demonstrated that metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb induced a decrease in ABCG2 expression in residual cells after treatment, enhancing their sensitivity to a subsequent cycle with PX (Fig. 7). In line with these results, Salem et al. [43] and Sanchez et al. [31] have described that metronomic mAChR activation decreases ABCG2 expression in breast cancer cells, enhancing the sensitivity of residual cells. Other CSC markers are SOX-2, OCT-4 and Nanog [114], which can be modulated by ABCG2 [115–117]. In breast cancer cells, Shan et al. [118] reported that increased expression of these markers is associated with greater pluripotency, less differentiation and less apoptosis, all characteristics of CSC. Following administration of metronomic chemotherapy, we observed a decrease in the expression of these key pluripotency markers, both in the absence and presence of Nic. These results are particularly relevant considering that Nic has been associated with an increase in SOX-2 [119], OCT-4 [120] and Nanog [119,120].

CSC are also characterized by anchorage-independent growth [118]. By using anchorage-independent growth assays and flow cytometry of CD44/CD24 markers, we determined that metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb decreased the proportion CSC both in the absence and presence of Nic. In line with these results, in human cells of glioblastoma [121–124], gastrointestinal cancer [125] and breast cancer [43], several authors have described that mAChR activation causes a decrease in the proportion of CSC similar to that here observed. However, those studies used muscarinic agonist concentrations several orders of magnitude higher than those used in the present study, which can lead to unwanted effects [126]. Likewise, it has been previously described that the activation of different mediators that participate in the muscarinic pathway induces a decrease in the proportion of CSC. In this sense, Justilien et al. [127] reported that PKC activation negatively modulates SOX-2 expression, decreasing the proportion of CSC in human lung squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, Yoshid-Koide et al. [128] and Chu et al. [129] described a negative modulation of Nanog expression and a decrease in CSC due to the activation of Ras and PKC, respectively. These findings are consistent with ours, which demonstrate the participation of these mediators as well as a decrease in these stemness marker proteins as a result of our metronomic chemotherapy.

In breast cancer cells, a subpopulation of CSC is identified as CD44+/CD24− [130]. To further investigate these CSC, we analyzed this cell subpopulation, and confirmed that metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb reduced the proportion of CSC among residual cells both in the absence and presence of Nic. These results were expected, given the previously determined low expression levels of the stemness proteins SOX-2, OCT-4 and Nanog. Furthermore, these results are in line with those described by Kuo et al. [131] and Park et al. [132] in MDA-MB-231 cells, showing a decrease in both the proportion of CSC determined as CD44+/CD24− and in the levels of SOX-2, OCT-4 and Nanog.

The reduction in the proportion of CSC induced by our metronomic chemotherapy was probably due to high levels of NO present, since Zhou et al. [133] and Park et al. [132] described that increased levels of this ROS induce differentiation, senescence and apoptosis of CSC. Similarly, Shi et al. [134] described that increased ROS levels in MDA-MB-231 cells lead to CSC differentiation, thereby reducing their proportion. Given the role of CSC in cancer treatment resistance and disease relapse [135,136], targeting this subpopulation is essential in antitumor therapy. Our findings demonstrate the ability of metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb to reduce the proportion of CSC, highlighting its potential to prevent tumor resistance and recurrence.

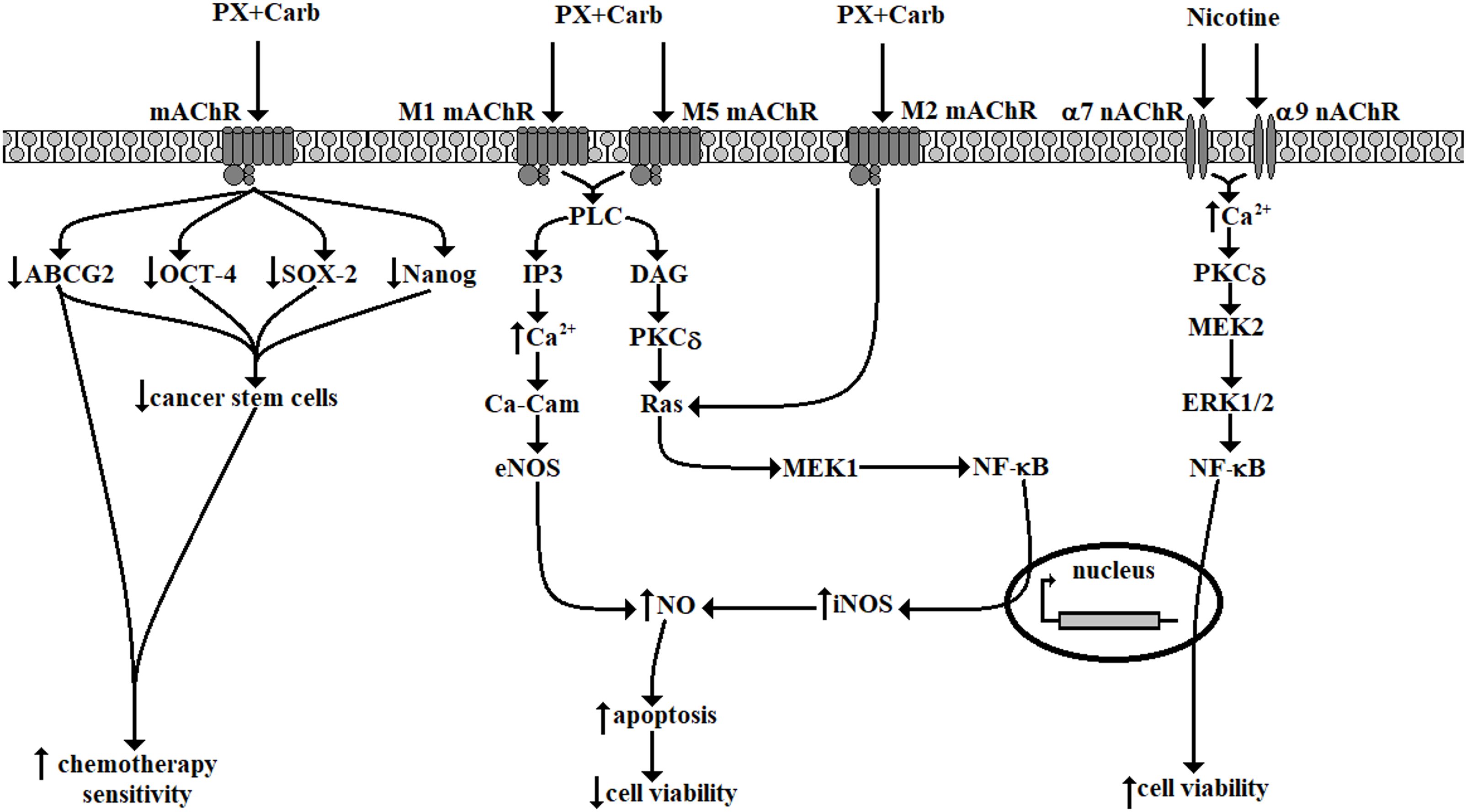

A possible mechanism of action of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb both in the absence and presence of Nic in TN breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells is proposed in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Possible signal transduction pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells activated by metronomic chemotherapy combining paclitaxel (PX) with carbachol (Carb) (10 nM and 8.6 pM, respectively) in the presence or absence of nicotine (100 nM). mAChR: muscarinic acetylcholine receptor; nAChR: nicotinic acetylcholine receptors; ABCG2: ATP “binding cassette” G2 drug transporter; OCT-4: octamer-binding transcription factor 4; SOX-2: sex-determining region Y-box 2; PLC: phospholipase C; IP3: inositol trisphosphate; DAG: diacylglycerol; Ca2+: calcium; PKCδ: protein kinase C subtype δ; Ca-Cam: calcium calmodulin; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinases; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NO: nitric oxide; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase. Diagram made using Microsoft Paint software

The main limitation of this study is that the conclusions drawn from the results are applicable only to human TN MDA-MB-231 cells. Additional experiments using other human TN breast cancer cell lines are necessary to support the extrapolation of these findings to all TN breast tumors. Another limitation is that, for some of the proposed signaling mediators, we assessed only their protein expression levels but not their functionality. Thus, additional functional assays of these mediators are necessary to confirm their involvement in the observed effect and to validate the proposed signaling pathway model.

Unlike that previously described in the conventional chemotherapy of breast cancer [25], the efficacy of metronomic chemotherapy combining PX with Carb was not modified in the presence of Nic. Cell viability was reduced by a mAChR-dependent mechanism with the participation of the intermediaries PLC, PKC, Ras, MEK and NF-κB, which would induce the expression and activity of NOS and whose product, NO, would induce cell apoptosis. We also determined an increase in chemotherapy sensitivity in the residual cells after our metronomic chemotherapy. This could be due to the decreased pluripotency of MDA-MB-231 cells, as determined by the observation of several pluripotency markers, including the expression of Nanog, SOX-2, OCT-4, and ABCG2. Their decrease could sensitize CSC to apoptosis, reduce their pluripotency and decrease their proportion in the residual cells after our metronomic chemotherapy.

In conclusion, the present results demonstrate that metronomic chemotherapy with PX and Carb is effective and selective for TN breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, both in the absence and presence of Nic. Results also demonstrate that our metronomic chemotherapy could be a useful neoadjuvant strategy for the treatment of TN breast tumors, as it increases the sensitivity of residual cells after treatment. This effect was likely due, at least in part, to a decrease in the proportion of CSC.

Acknowledgement: We thank Patricia M. Fernández, M. Alejandra Verón, M. Cristina Lincon, Daniela C. Néspola, Alcira Mazziotti, Vanesa Fernández, Rosana Leiva and Daniel Guerrero from the Centro de Estudios Farmacológicos y Botánicos (CEFYBO), Buenos Aires, Argentina, for their technical assistance.

Funding Statement: This research was carried out with grants from the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion (ANPCyT) [2015-2396] and ORT Argentina’s 2021–2025 Scientific Research Internship Program.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Alejandro Javier Español; methodology, Alejandro Javier Español; validation, Alejandro Javier Español; formal analysis, Alejandro Javier Español, Yamila Sanchez; investigation, Alejandro Javier Español, Yamila Sanchez, Sofia Volpi; resources, Alejandro Javier Español; writing—original draft preparation, Alejandro Javier Español; writing—review and editing, Alejandro Javier Español, Yamila Sanchez, Sofia Volpi; visualization, Alejandro Javier Español; supervision, Alejandro Javier Español; project administration, Alejandro Javier Español; funding acquisition, Alejandro Javier Español. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sets are available upon request at Alejandro Javier Español. Email: aespan_1999@yahoo.com. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Fig. S1. Viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. Concentration-response curves of nicotine on MDA-MB-231 cell viability treated for 2, 8, 15 or 22 days. One-way ANOVA and complementary Tukey test were performed. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. control considered as 100%. Values are the mean±SD of four experiments performed in duplicate. n = 4. Table S1. Relationship between targets, ligands and their concentration. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.068034/s1.

Abbreviations

| 7-AAD | 7-aminoactinomycin D |

| 4S-AEPN | N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]pentyl]-N′-nitroguanidine Tris |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ABCG2 | ABC super-family G member 2 |

| AG | Aminoguanidine |

| AT | Atropine |

| Carb | Carbachol |

| CSC | Cancer stem cells |

| Damp | 4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methyl-piperidine |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EC | Effective concentration |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ELDA | Extreme limiting dilution assay |

| eNOS | Endothelial NOS |

| ER | Estrogen receptors |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FIT-C | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FTS | S-trans,trans-farnesylthiosalicylic acid |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| IKKβ | Ikappa kinase subunit beta |

| IMD | IMD354 |

| iNOS | Inducible NOS |

| L-NIO | L-N5-(1-iminoethyl) ornithine hydrochloride |

| l-nmma | NGmonomethyl-L arginine |

| Lut | Luteolin |

| mAChRs | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| Met | Methoctramine |

| MLA | Methyllycaconitine |

| MM | Mecamylamine |

| MTT | Etrazolium salt 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| nAChRs | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors |

| NCDC | 2-nitro-4-carboxyphenyl N,N-diphenyl carbamate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Nic | Nicotine |

| nNOS | Neuronal NOS |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NO2- | nitrite |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| OCT-4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PD | PD098059 |

| Pir | Pirenzepine |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PR | Progesterone receptors |

| PX | Paclitaxel |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SOX-2 | Sex-determining region Y-box 2 |

| Stau | Staurosporine |

| TN | Triple-negative |

| Trop | Tropicamide |

| Xan | Xanomeline |

References

1. Cancer Today. World Health Organization. [cited 2024 Feb 8]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. [Google Scholar]

2. Ma L, Jiang Z, Hou X, Xu Y, Chen Z, Zhang S, et al. LA-D-B1, a novel Abemaciclib derivative, exerts anti-breast cancer effects through CDK4/6. Biocell. 2024;48(5):847–60. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.050868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dai X, Cheng H, Bai Z, Li J. Breast cancer cell line classification and its relevance with breast tumor subtyping. J Cancer. 2017;8(16):3131–41. doi:10.7150/jca.18457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Roy M, Fowler AM, Ulaner GA, Mahajan A. Molecular classification of breast cancer. PET Clin. 2023;18(4):441–58. doi:10.1016/j.cpet.2023.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen international expert consensus conference on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1181. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mosca L, Ilari A, Fazi F, Assaraf YG, Colotti G. Taxanes in cancer treatment: activity, chemoresistance and its overcoming. Drug Resist Updat. 2021;54:100742. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2020.100742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rowinsky EK, Cazenave LA, Donehower RC. Taxol: a novel investigational antimicrotubule agent. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(15):1247–59. doi:10.1093/jnci/82.15.1247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Abu Samaan TM, Samec M, Liskova A, Kubatka P, Büsselberg D. Paclitaxel’s mechanistic and clinical effects on breast cancer. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):789. doi:10.3390/biom9120789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Moon DO. Interplay between paclitaxel, gap junctions, and kinases: unraveling mechanisms of action and resistance in cancer therapy. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):472. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-09411-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yin S, Bhattacharya R, Cabral F. Human mutations that confer paclitaxel resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(2):327–35. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Hu T, Li Z, Gao CY, Cho CH. Mechanisms of drug resistance in colon cancer and its therapeutic strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(30):6876–89. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. McFadden M, Singh SK, Kinnel B, Varambally S, Singh R. The effect of paclitaxel- and fisetin-loaded PBM nanoparticles on apoptosis and reversal of drug resistance gene ABCG2 in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2023;16(1):220. doi:10.1186/s13048-023-01308-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hong WC, Kim M, Kim JH, Kang HW, Fang S, Jung HS, et al. The FOXP1-ABCG2 axis promotes the proliferation of cancer stem cells and induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025;32(5):563–72. doi:10.1038/s41417-025-00896-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Prieto-Vila M, Takahashi RU, Usuba W, Kohama I, Ochiya T. Drug resistance driven by cancer stem cells and their niche. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2574. doi:10.3390/ijms18122574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Duz MB, Karatas OF. Differential expression of ABCB1, ABCG2, and KLF4 as putative indicators for paclitaxel resistance in human epithelial type 2 cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(2):1393–400. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06167-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]