Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Monocyte Phenotypic Plasticity in Peripheral Artery Disease: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Targets

1 Hamidiye Health Sciences Institute, Department of Immunology, Health Sciences University, Istanbul, 34668, Türkiye

2 Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Health Sciences University, Istanbul, 34760, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Gizem Kaynar Beyaz. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mechanisms Driving COPD, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Innovations)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072368

Received 25 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) remains a significant global health issue, with current treatments primarily focused on relieving symptoms and addressing macrovascular issues. However, critical immunoinflammatory mechanisms are often overlooked. Recent evidence suggests that monocyte phenotypic plasticity plays a central role in PAD development, affecting atherogenesis, plaque progression, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and chronic ischemic remodeling. This narrative review aims to summarize the latest advances (2023–2025) in understanding monocyte diversity, functional states, and their changes throughout different stages of PAD. We discuss both established and emerging biomarkers, such as circulating monocyte subset proportions, functional assays, immune checkpoint expression, and multi-omics signatures, highlighting their potential for prognosis and the challenges in translating them to clinical practice. We also present a stage-specific approach to mapping out potential therapies, linking monocyte phenotypes to molecular targets and possible interventions. Additionally, we address regulatory, economic, and implementation considerations for applying these findings in a clinical setting. The goal of this review is to facilitate the development of targeted immunomodulatory strategies to improve limb and cardiovascular outcomes in PAD by combining mechanistic understanding with therapeutic innovation.Keywords

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) affects more than 230 million people worldwide and carries a high burden of limb morbidity and cardiovascular mortality [1,2]. Without efficient treatment, patients with PAD face an increased risk of cardiovascular conditions such as myocardial infarction and stroke [3]. Even with contemporary management (antiplatelet agents, statin-based lipid-lowering agents, supervised exercise therapy, and endovascular or surgical revascularization), long-term outcomes remain suboptimal, with a persistent excess of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and major adverse limb events (MALE). The 2024 European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) recommendations underscore the lack of truly disease-modifying therapies, particularly for chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) or recurrent diseases. Therefore, they emphasize personalized care combining optimal medical therapy, structured exercise programs, and revascularization when indicated [4].

Atherogenesis and progression in PAD are increasingly recognized as an immunoinflammatory process. Endothelial dysfunction promotes monocyte recruitment and immune cell-mediated plaque remodeling [5,6]. Elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) have been linked to thrombotic events after revascularization [1]. These highlight the prognostic and potentially pathogenic role of immune activation in PAD. Within this inflammatory milieu, monocytes exhibit remarkable phenotypic plasticity (CD14++CD16− classical, CD14++CD16+ intermediate, CD14+CD16++ non-classical monocytes) [7]. This phenotypic plasticity allows these cells to adopt diverse functional states, ranging from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory and tissue repair. This plasticity is governed by complex networks of transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic regulatory mechanisms. A deeper understanding of these processes offers the potential to uncover both biomarkers of disease progression and therapeutic targets that regulate monocyte behavior [3,8].

Beyond subset identity, metabolic and transcriptional programming also shape monocyte behavior in PAD. Key regulators include the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) axis, which drives glycolysis, and the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)–nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway [9,10]. In parallel, immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed death-ligand 2 (PD-L2), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM-3), and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) have an impact on monocyte behavior [2]. These mechanistic processes regulate monocyte activity across the stages of PAD, from early lesion formation to ischemia-reperfusion and chronic ischemic remodeling [2,11]. This may reflect chronic immune activation or exhaustion and serve as novel biomarkers or regulators of disease activity.

This narrative review aims to critically synthesize current knowledge on the phenotypic plasticity of monocytes in PAD. The article also highlights the molecular and metabolic drivers of monocyte transitions, highlights their importance as biomarkers of disease progression and outcome, and discusses the feasibility of targeting these pathways for therapeutic benefit. By integrating mechanistic insight with translational perspectives, it is aimed to establish a stage-specific framework for incorporating monocyte-focused strategies into the future management of PAD.

This narrative review examines current (2020–2025 priority) human and translational studies on monocyte plasticity in PAD. A search of PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar was conducted using the key terms peripheral artery disease, monocyte subsets, phenotypic plasticity, and immunomodulation. Studies from other disciplines (e.g., rheumatology, oncology) were included only when pathways were conserved and clearly related to vascular inflammation or repair by mechanistic analogy. No quantitative synthesis or formal risk of bias assessment was performed. Limitations of evidence were highlighted where appropriate.

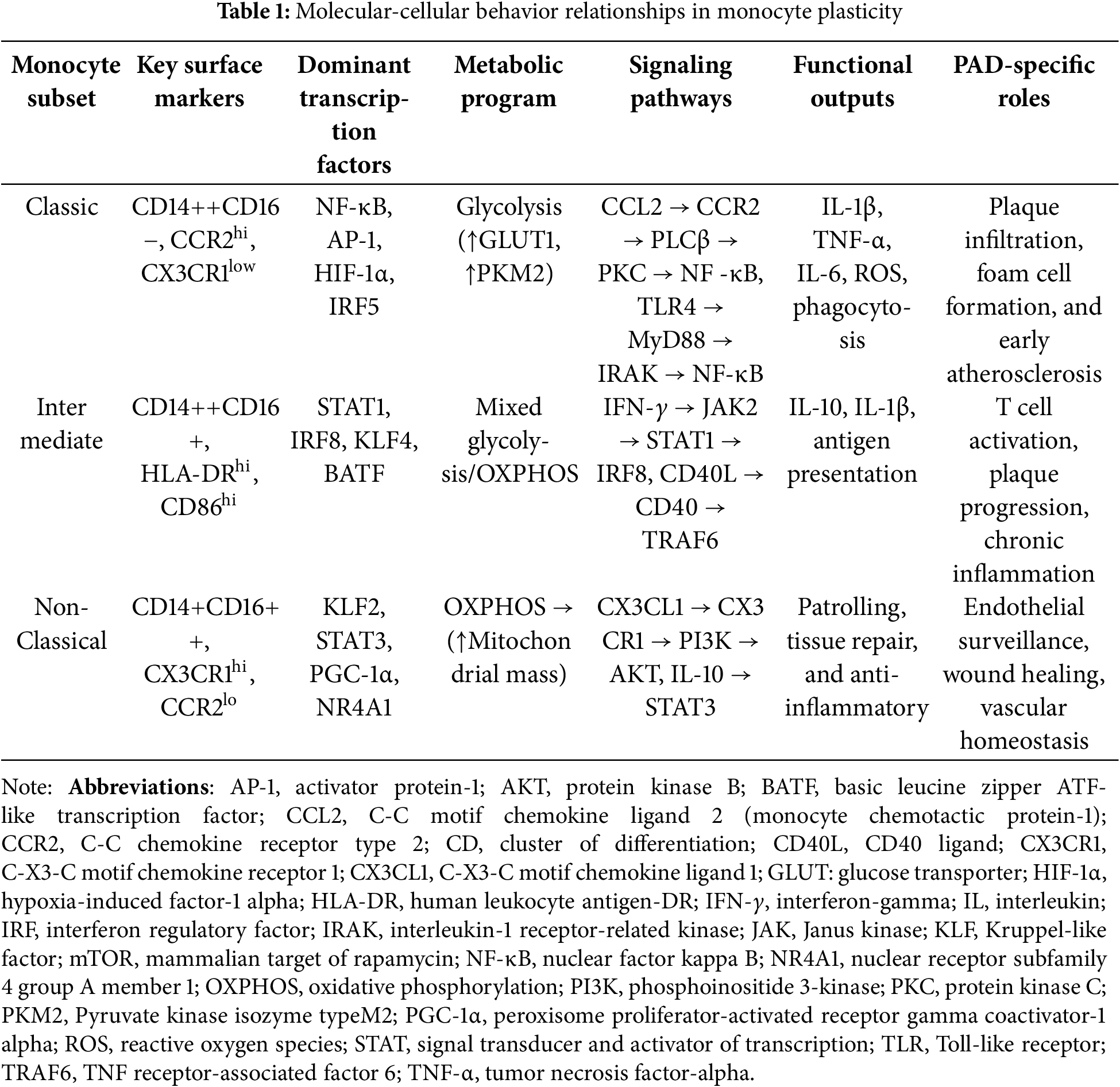

3 Monocyte Heterogeneity and Plasticity

Monocytes are a phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous population circulating in the blood. In humans, three subgroups are defined based on CD14 and CD16 expression: classical monocytes (CD14++CD16−), intermediate monocytes (CD14++CD16+), and non-classical monocytes (CD14+CD16++). Classical monocytes constitute 85%–90% of circulating monocytes, while nonclassical and intermediate monocytes each constitute 5%–10% of circulating monocytes [12]. Emerging evidence suggests that each subgroup exhibits significant variability and a transitional continuum within the subgroup, rather than a distinct classification [11].

Classical monocytes are the predominant proinflammatory subgroup, exhibiting high phagocytic capacity and rapid responses to danger signals [12]. Intermediate monocytes display a mixed profile with potent antigen-presenting properties and context-dependent inflammatory activity that can sustain chronic immune activation in vascular diseases [13]. Non-classical monocytes (patrolling monocytes) primarily infiltrate the endothelium and are enriched for vascular surveillance and tissue repair functions [14–17].

3.2 Signaling and Transcriptional Control

Inflammatory activation in classical monocytes is associated with Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and downstream nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) programs, with contributions from interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) also present [18,19]. Intermediate monocytes exhibit high activity of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–Janus kinase (JAK)–transcription 1 (STAT1) signal transducer and activator and CD40–CD40 ligand co-stimulatory pathways [13,14]. Non-classical monocytes are maintained by C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) signaling and IL-10–STAT3 tone, while receiving transcriptional support from Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) [20,21].

3.3 Metabolic Programming and Plasticity

Classical monocytes promote glycolysis via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) axis that increases glucose uptake via glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Subsequently, they support rapid cytokine synthesis, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 [9,10]. Non-classical monocytes favor oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) with increased mitochondrial mass, regulated by PGC-1α [20]. Intermediate monocytes exhibit a mixed glycolytic/OXPHOS metabolism [21]. Subset transitions involve epigenetic reprogramming (e.g., trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 [H3K4me3] in metabolic genes; demethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 [H3K27me3] in anti-inflammatory loci), enabling rapid switching between inflammatory and reparative states [21–23].

In PAD, classical monocytes contribute to early lesion formation through endothelial adhesion, arterial wall infiltration, lipid uptake, and proinflammatory mediator release [19,24]. Intermediate monocytes expand in advanced plaques and can sustain chronic inflammation through antigen presentation and costimulation [24]. The decreased frequency of non-classical monocytes in advanced disease is consistent with impaired endothelial homeostasis and diminished repair capacity [5,6]. High-dimensional profiling methods such as flow cytometry, single-cell transcriptomics, and spatial immunology have revealed PAD-specific transcriptional and metabolic signatures in these subsets, reinforcing their stage-dependent roles in atherogenesis, ischemia-reperfusion responses, and tissue remodeling [7,17]. Similar to macrophages in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases, demonstrating a continuum of plasticity beyond the traditional M1/M2 paradigm, monocytes in PAD exhibit dynamic transitions shaped by metabolic, transcriptional, and environmental cues [25].

The molecular basis of these phenotypic transitions is detailed in Table 1, which summarizes the key signaling pathways.

4 Monocyte Plasticity in PAD Pathophysiology

The functional roles of monocytes in PAD follow a temporal continuum that reflects disease progression. During early lesion formation, classical monocytes predominate and direct endothelial adhesion, arterial wall infiltration, and lipid uptake [19,24]. As the disease progresses, the phenotype shifts toward intermediate monocytes that expand and maintain chronic vascular inflammation, promoting plaque progression and destabilization [13,24]. In late-stage ischemic states, especially after revascularization, monocytes exhibit context-dependent functions. They can amplify tissue damage through reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proinflammatory signaling or contribute to repair through proangiogenic and remodeling pathways. Non-classical monocytes become increasingly important during chronic ischemia and remodeling, where they support endothelial surveillance, vascular homeostasis, and collateral formation [26–28].

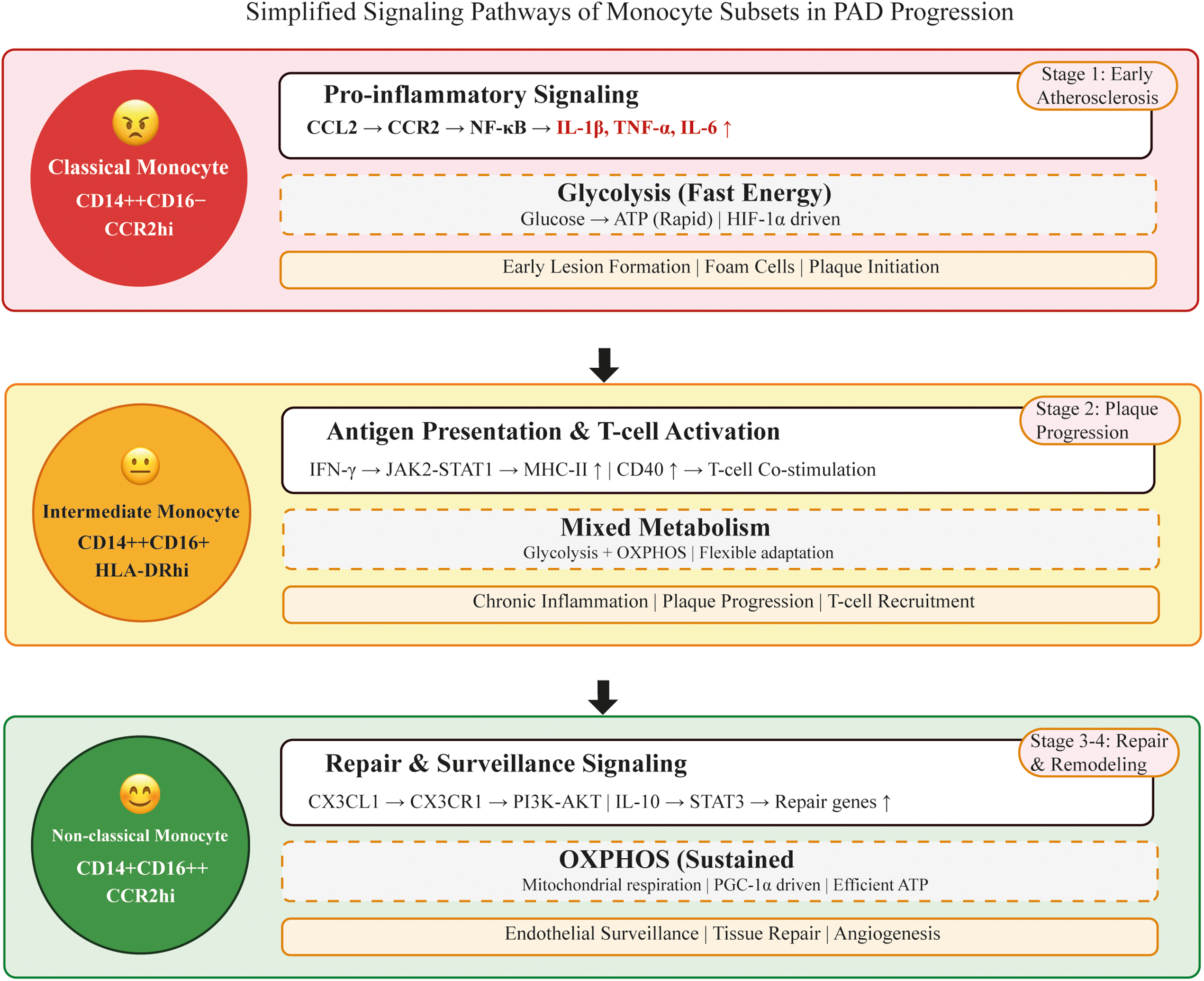

Together, these dynamic changes highlight the resilience of monocyte subsets: from proinflammatory drivers of atherogenesis to reparative regulators of ischemic recovery. The following subsections summarize these contributions in a stage-specific sequence reflecting the PAD continuum from lesion initiation through plaque progression to ischemia-reperfusion and chronic remodeling (Figs. 1 and 2). Fig. 1 illustrates the detailed molecular pathways governing monocyte plasticity and their integration across the stages of PAD, while Fig. 2 provides a simplified graphical summary of the three monocyte subsets and their key signaling cascades for easy identification.

Figure 1: Molecular signaling pathways governing monocyte plasticity in PAD. Molecular signaling pathways governing monocyte phenotypic plasticity in peripheral artery disease. The diagram shows the different signaling pathways that drive classical (pro-inflammatory), intermediate (mixed), and non-classical (anti-inflammatory/patrol) monocyte phenotypes. Each pathway progresses from extracellular stimuli to receptor engagement, intracellular signaling, transcriptional control, metabolic reprogramming, and functional outputs. The lower panel illustrates how these molecular mechanisms integrate at different stages of PAD pathophysiology. Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; AMPK: Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; CCR2, C-C chemokine receptor type 2; CD, cluster of differentiation; CD40L: CD40 ligand; CX3CL1, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; CX3CR1, C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1; HIF-1α, hypoxia-induced factor-1 alpha; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen-DR; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; IL, interleukin; IRAK, interleukin-1 receptor-related kinase; IRF: interferon regulatory factor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; KLF2: Kruppel-like factor 2; MyD88, Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response 88; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light chain enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3: NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; oxLDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PD-L2: programmed death-ligand 2; PPARγ: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; PKC, Protein Kinase C; PKM2, Pyruvate kinase isozyme typeM2; PLC, Phospholipase C; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; ROS: reactive oxygen species; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TRAF: TNF receptor-associated factor; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TIM-3, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor

Figure 2: Simplified cartoon depicting monocyte subset signaling pathways in PAD progression. Top panel (Red): Classical monocytes drive early atherosclerotic lesion formation via CCL2-CCR2 proinflammatory signaling and glycolytic metabolism. These cells produce high levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and contribute to foam cell formation and plaque formation. Middle panel (Yellow): Intermediate monocytes sustain chronic inflammation during plaque progression via the IFN-γ-JAK2-STAT1 signaling pathway. They exhibit enhanced antigen presentation capacity by upregulating MHC-II and CD40, activate T cells, and sustain adaptive immune responses. These cells utilize complex metabolic programming for functional flexibility. Lower panel (Green): Non-classical monocytes support tissue repair and endothelial surveillance through the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 and IL-10-STAT3 anti-inflammatory pathways. They rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for sustained energy production and promote angiogenesis and vascular remodeling during chronic ischemic stages. Arrows between panels indicate disease progression from early atherosclerosis to chronic inflammation and tissue repair stages. Each monocyte subset is represented with distinct visual features (facial expressions and colors) to facilitate easy recognition of their functional roles in PAD pathophysiology. Abbreviations: MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase

4.1 Early Atherosclerotic Development

The initiation of atherosclerotic lesions in peripheral arteries involves complex interactions. The earliest stage is characterized by endothelial dysfunction, lipid accumulation, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Classical monocytes (CD14++CD16−) are the predominant subset recruited to the arterial wall at this stage. Their migration occurs primarily through the C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)2-C-C chemokine receptor type (CCR)2 axis. This axis directs circulating monocytes to sites of endothelial activation. This proinflammatory cell population expresses vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), nitric oxide (NO) synthase, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [24,29,30]. Upon entering the arterial wall, classical monocytes differentiate into macrophages, contributing to foam cell formation and the initiation of atherosclerotic lesions [19,31].

Based on signaling pathways, classical monocytes activate the TLR4-myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)-NF-κB pathways, leading to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [18,19,32]. These responses potentiate endothelial activation, promote vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, and perpetuate local inflammation [6].

At the molecular level, early atherosclerotic development involves specific mechanistic cascades. Recognition of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by CD36 and SR-A1 receptors on classical monocytes triggers calcium influx and PKC activation, leading to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase formation and ROS production [31]. This oxidative stress stabilizes HIF-1α, leading to HIF-1α-associated proinflammatory gene expression. In this process, activation of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome leads to the production of mature IL-1β and IL-18, the inflammatory cytokines, from their precursor forms [33,34]. At the same time, the CCL2-CCR2 axis activates the JAK2-STAT3 pathway, promoting survival signals that prevent apoptosis during the inflammatory phase [29].

In terms of clinical implications, elevated circulating classical monocyte counts and increased CCR2 expression have been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events in PAD patients [1,19]. Genetic studies have also shown that rare loss-of-function CCR2 variants are associated with reduced lifetime cardiovascular risk, highlighting the importance of CCR2 involvement in the early stages of disease [30].

4.2 Plaque Progression and Complications

As PAD progresses, the monocyte compartment shifts toward an expansion of intermediate monocytes. These subgroup cells exhibit enhanced antigen-presenting capacity and sustain chronic vascular inflammation. They express high levels of human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) and costimulatory molecules such as CD40, supporting long-term T cell activation [13].

The intermediate monocytes are strongly influenced by the interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and STAT1 axis, which directs the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and promotes antigen presentation [13]. The CD40–CD40 ligand (CD40L) pathway is also central. It amplifies NF-κB signaling and induces proinflammatory cytokine production, which further destabilizes the plaque microenvironment [9,14].

Sustained activation facilitates lymphocyte-monocyte interactions and promotes the persistence of activated T cells. This environment increases the release of matrix-degrading enzymes and oxidative mediators, weakening the fibrous cap and predisposing plaques to rupture. Indeed, the patients with advanced PAD exhibit an increased number of circulating intermediate monocytes, which are associated with worse limb outcomes and accelerated atherosclerotic progression [24]. Therapeutic strategies targeting this stage (such as immune checkpoint modulation or inflammasome blockade) are currently being investigated as potential approaches to limit plaque instability [2,16].

4.3 Ischemia-Reperfusion and Tissue Repair

Acute tissue ischemia followed by reperfusion, such as after revascularization procedures, causes an increase in ROS and inflammatory mediators. These factors activate multiple monocyte subsets simultaneously [35,36]. Under oxidative stress conditions, both classical and intermediate monocyte populations are recruited, while nonclassical monocytes undergo phenotypic switching [37].

In the signaling context, hypoxia triggers HIF-1α accumulation and the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation. These changes shift metabolism toward glycolysis and impair mitochondrial function [34,37]. The metabolic reprogramming amplifies cytokine secretion, particularly IL-1β and TNF-α, worsening tissue injury [10,18].

Experimental studies indicate that ischemia can train monocytes toward a heightened inflammatory phenotype upon re-exposure, mediated by metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming [35,36]. Conversely, ischemic conditioning has also been shown to direct monocytes toward pro-angiogenic and tissue-reparative functions, depending on the duration and context [37].

In PAD patients undergoing revascularization, exaggerated ischemia-reperfusion responses are associated with major adverse limb events (MALEs) and impaired recovery [38]. Therapeutic modulation of monocyte metabolism or trained immunity may offer strategies to mitigate reperfusion injury [35,37].

4.4 Chronic Ischemia and Remodeling

In the chronic phase of PAD, tissues are subjected to persistent hypoperfusion and low-grade inflammation. This environment drives maladaptive remodeling in the vascular wall and skeletal muscle. Non-classical monocytes become increasingly important at this stage. They patrol the endothelium and support repair processes [26–28].

Non-classical monocytes rely on CX3CR1-CX3CL1 interactions for survival and endothelial surveillance [27]. Tissue repair functions are facilitated by oxidative phosphorylation-based metabolism promoted through anti-inflammatory signals, including IL-10–STAT3 pathways and PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis [20,37]. These monocytes secrete VEGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and other reparative cytokines that stimulate angiogenesis and collateral vessel formation [39]. Experimental data suggest that tissue remodeling monocytes enhance revascularization of ischemic limbs and improve perfusion recovery [37,39].

Decreased numbers or dysfunction of nonclassical monocytes have been associated with poor wound healing and an increased risk of limb events in patients with PAD [26,38]. Interventions such as structured exercise programs increase monocyte repair activity, reduce muscle inflammation, and improve blood flow [40]. These findings highlight the potential of therapies aimed at enhancing nonclassical monocyte function to promote vascular remodeling and limb salvage in advanced PAD.

5 Clinical Correlations and Biomarkers

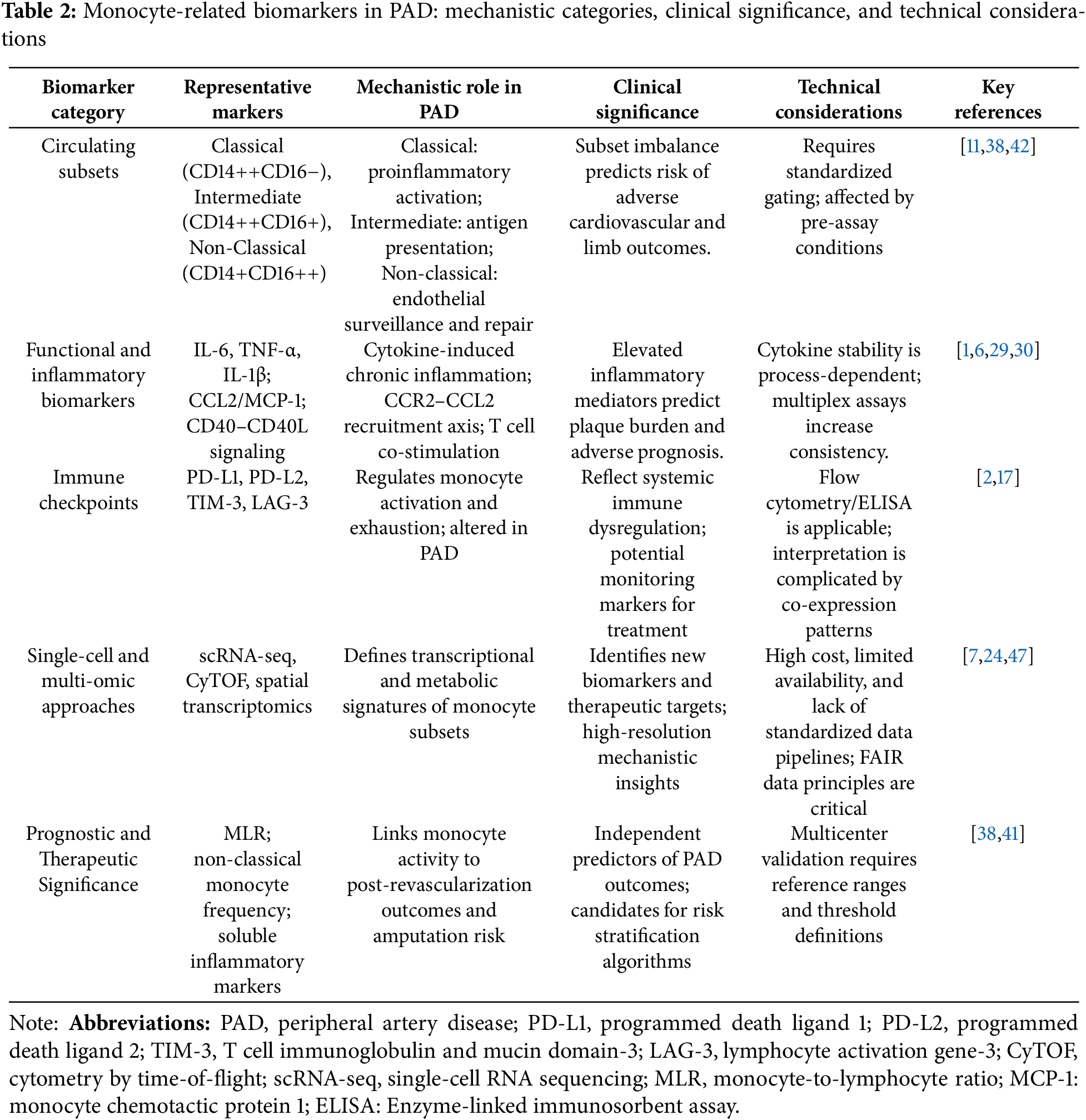

Monocyte heterogeneity has direct clinical implications in PAD, affecting both disease progression and treatment outcomes. Circulating subset distribution, functional markers, and soluble biomarkers provide prognostic information beyond traditional risk factors. Emerging evidence suggests that monocyte-based markers can serve as predictors of adverse events, guide treatment strategies, and inform risk stratification in vascular medicine [41].

5.1 Circulating Monocyte Subsets as Biomarkers

Variations in monocyte subset distribution are common in PAD. High classical monocyte counts are associated with higher rates of systemic inflammation and major adverse cardiovascular and extremity events [2,42]. Conversely, decreased nonclassical monocyte frequencies may reflect impaired endothelial maintenance, poor wound healing, and poorer prognosis after revascularization [26–28].

Intermediate monocytes (CD14++CD16+) are often expanded in advanced PAD and predict disease severity and plaque instability [42]. High-dimensional profiling confirms that these patients exhibit distinct transcriptional and metabolic programs, supporting their role as drivers of chronic inflammation [43]. Collectively, the subset distribution provides a simple yet powerful biomarker panel that integrates inflammatory activity with vascular outcomes.

5.2 Functional and Inflammatory Biomarkers

Beyond subset distribution, the functional and inflammatory activity of monocytes provides additional prognostic insight. Expression of activation markers such as CD11b, CD14, and CD16 on circulating monocytes correlates with inflammatory status and tissue recruitment potential [42]. Increased production of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α by classical circulating monocytes reflects persistent vascular inflammation and predicts adverse limb outcomes [6,42]. Similarly, increased levels of C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2, also known as monocyte chemotactic protein-1, MCP-1) confer CCR2-dependent recruitment of classical monocytes to atherosclerotic lesions and are associated with plaque burden and poorer clinical prognosis [29,39].

Metabolic activities of monocytes also serve as functional biomarkers. Increased reliance on aerobic glycolysis via mTOR-HIF-1α identifies highly inflammatory monocytes. Contrary, increased OXPHOS is associated with reparative phenotypes [9,23]. Patient studies confirm that these metabolic profiles are associated with PAD severity and therapeutic response [10].

Epigenetic programming further stabilizes these phenotypes. Persistent histone modifications, such as H3K4 trimethylation and lactate-induced histone lactylation at glycolytic genes, maintain trained immunity in monocytes. These modifications ultimately enhance vascular inflammation even after the initial trigger has been removed [22,44]. These molecular changes not only reflect current disease activity but also predict long-term risk.

5.3 Immune Checkpoint Expression

Immune checkpoint molecules on monocytes regulate inflammatory tone. Patients with PAD exhibit altered expression of both soluble and membrane-bound checkpoints, including PD-L2 and TIM-3, and LAG-3. These molecules are being investigated as potential therapeutic targets to restore immune homeostasis and normally suppress excessive activation and promote resolution of inflammation. In PAD, their dysregulation contributes to persistent monocyte activation and impaired immune balance [2]. Experimental studies also indicate that checkpoint pathways intersect with metabolic programs; for example, PD-L1 signaling can regulate glycolysis and mitochondrial function in myeloid cells [23].

Clinically, checkpoint-related alterations have been associated with disease severity and systemic immune dysfunction. While most evidence is correlational, these findings raise the possibility that checkpoint-based therapies could be repurposed to normalize monocyte activity in vascular disease, provided safety concerns from oncology are carefully addressed [3].

5.4 Single-Cell and Multi-Omic Approaches

High-dimensional technologies have transformed our understanding of monocyte biology in PAD. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and multi-omics profiling reveal transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic diversities within monocyte and macrophage subsets. These diversities may reflect disease-specific states that are undetectable by traditional gating strategies [17,43]. For example, single-cell profiling has identified PAD-associated monocyte programs enriched in inflammatory mediators and antigen presentation pathways [7,24,38].

Spatial transcriptomic and multi-omics integration further expands this knowledge by linking monocyte heterogeneity to plaque microenvironments and ischemic muscle tissue [7]. These methods demonstrate that monocyte-derived macrophages in PAD lesions acquire distinct signatures compared to coronary or carotid disease, reflecting vascular bed specificity [24].

Standardization of single-cell workflows remains critical. Technical variability in sample processing, sequencing depth, and computational processes can impact results. International efforts such as EuroFlow and the Human Immunophenotyping Consortium have published guidelines to improve reproducibility and inter-cohort comparability [45,46].

Looking ahead, multi-omic datasets combined with artificial intelligence (AI)-based integration could enable predictive modeling of PAD outcomes and the identification of therapeutic targets. These approaches hold promise for shifting monocyte biomarkers from exploratory research tools to clinically applicable analyses [47].

Table 2 summarizes the major classes of monocyte-related biomarkers in PAD from mechanistic, clinical, and technical perspectives. Circulating subsets, inflammatory mediators, and immune checkpoints capture mechanistic activity, while advanced single-cell approaches identify novel signatures. Prognostic markers such as the monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio and nonclassical monocyte frequency demonstrate independent predictive value but require validation. Technical considerations include pre-analytical control, compatible gating strategies, and data standardization to ensure reproducibility and clinical translation.

5.5 Prognostic and Therapeutic Significance

Monocyte-derived biomarkers are increasingly recognized as independent predictors of PAD outcomes. High monocyte counts and a high monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) predict worse prognosis after revascularization and are associated with MALEs [38,41]. Reductions in non-classical subsets further increase the risk of impaired vascular repair and higher amputation [26,38].

Therapeutic studies also highlight monocytes as dynamic markers of treatment response. Inflammatory modulation with IL-1β blockade (canakinumab) reduced systemic monocyte activation and improved cardiovascular outcomes in large-scale studies [16]. Similarly, colchicine therapy, currently under investigation in PAD (e.g., LEADER-PAD, NCT04774159), is expected to attenuate monocyte-mediated inflammation and reduce adverse events [48,49].

Emerging metabolic and epigenetic biomarkers may enhance this approach. For example, glycolysis-dependent monocyte signatures and persistent histone modifications (trained immunity) are associated with plaque instability and poor clinical outcomes [9,22,44]. Monitoring such functional states could enable precise stratification and early identification of high-risk patients.

Taken together, these findings highlight the dual role of monocyte biomarkers: they provide prognostic insight into PAD progression and serve as real-time indicators of therapeutic efficacy. Integrating subset distribution, functional analyses, and checkpoint profiles into clinical practice could improve both risk prediction and treatment personalization in vascular diseases.

5.6 Technical Considerations for Monocyte Biomarkers in PAD

The clinical translation of monocyte-based biomarkers depends heavily on technical robustness and standardization. Flow cytometry remains the primary tool for immunophenotyping. However, it is highly pre-analytical variables such as anticoagulant choice, sample processing time, and storage conditions, which can significantly alter monocyte surface marker expression and functional outcomes [45]. Standardization efforts, including the use of compatible gating strategies, EuroFlow protocols, and calibration beads, have improved reproducibility across laboratories [45,46].

Advanced profiling methods such as single-cell RNA sequencing, cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF), and multiplex proteomics offer unique insight into monocyte heterogeneity. However, they remain expensive, technologically challenging, and limited to specialized centers [46]. Cross-platform data integration also presents challenges and requires compatible bioinformatics pipelines. Efforts to implement FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles and standardized computational data pipelines are essential to ensure cross-cohort reproducibility and clinical utility [47].

Another limitation is clinical validation. Most studies on monocyte biomarkers in PAD are small, cross-sectional, or exploratory, with limited multicenter standardization. Large, prospective, multicenter studies are needed to establish reference intervals, prognostic thresholds, and decision-making cutoffs [41].

Practical recommendations to overcome these obstacles include:

1. Standardize measurement protocols. Use compatible flow cytometry gating strategies and marker panels to ensure consistency across laboratories [50,51].

2. Control pre-analytical variables. Minimize delays from blood collection to processing, standardize anticoagulant selection, and ensure stable storage conditions to preserve monocyte phenotype. Even short delays or temperature changes can alter monocyte markers and functional analyses, so standard operating procedures (SOPs) should specify sampling windows and stabilization options [52].

3. Use reference materials and inter-center calibration. Include daily beads and reference samples; implement instrument standardization frameworks (e.g., EuroFlow SOPs) to minimize inter-center drift and ensure longitudinal comparability in multicenter PAD cohorts [53]. Also, share data in standardized formats to facilitate validation and meta-analysis in PAD studies [47].

Taken together, these steps provide the technical basis for incorporating monocyte-based biomarkers into PAD research and clinical decision-making.

6 Molecular Approaches to Modulate Monocyte Plasticity in PAD: A Stage-Specific Framework

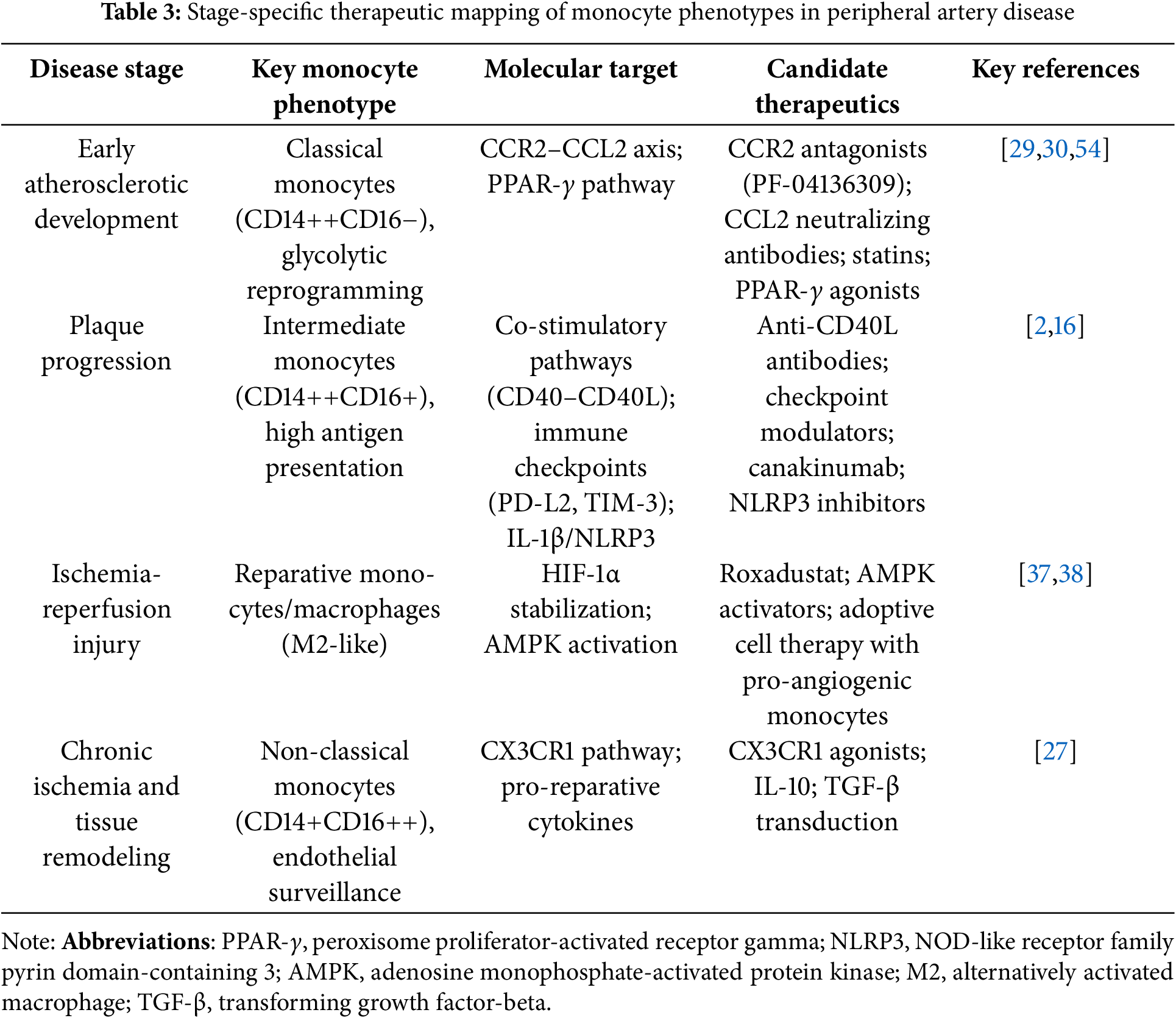

Monocytes do not behave uniformly and adapt to the changing vascular and tissue microenvironment as PAD progresses. In addition to their phenotypic evolution, they express distinct molecular pathways in each stage of PAD. Mapping temporal monocyte phenotypes creates opportunities for stage-specific interventions targeting distinct molecular pathways during disease evolution. Below, we summarize the translational roadmap of candidate strategies for precise immunomodulation in PAD emerges.

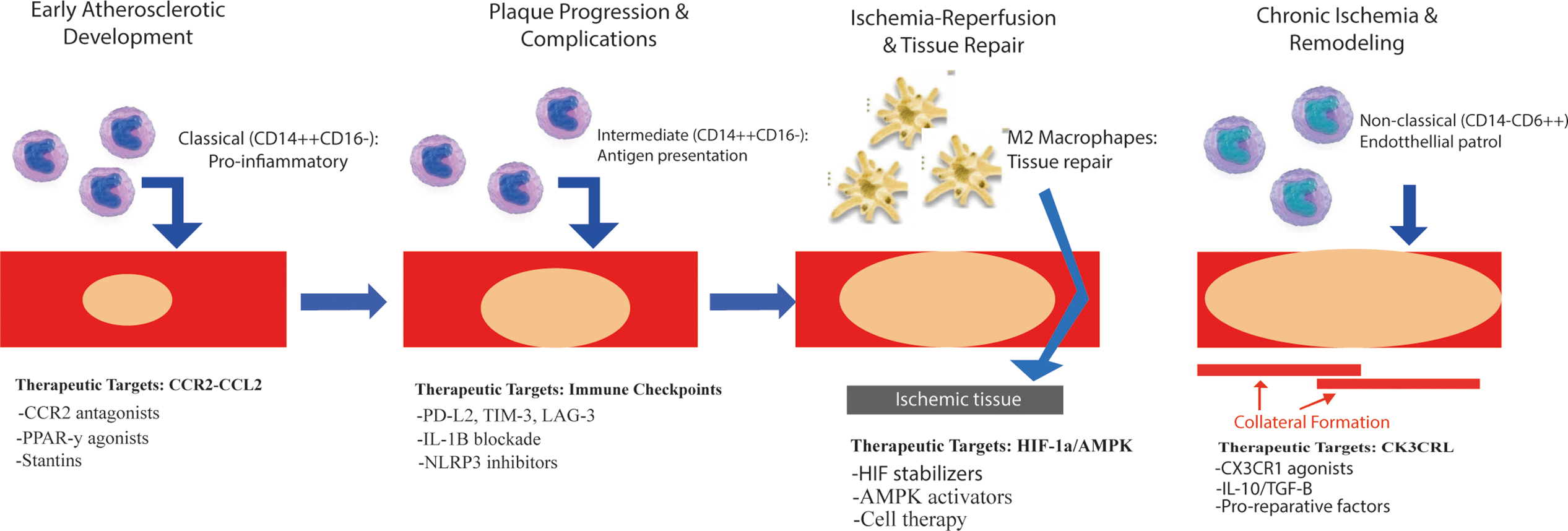

6.1 Early Atherosclerotic Development: Inhibition of Recruitment and Pro-Inflammatory Reprogramming

During the lesion initiation phase, CCR2–CCL2-mediated recruitment of classical monocytes is a central driving force. These cells drive endothelial adhesion, foam cell formation, and cytokine release. Mechanistically, blocking CCL2-CCR2 signaling prevents activation of downstream PLCβ–PKC–NF-κB signaling and thereby reduces monocyte recruitment and inflammatory gene transcription [29]. CCR2 inhibitors (e.g., PF-04136309) or upstream chemokines have been shown to reduce plaque burden in preclinical atherosclerosis models [29,30]. Statins not only lower lipids but also reduce glycolysis via the mTOR-HIF-1α axis [10]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ agonists may further limit glycolytic activation and promote anti-inflammatory reprogramming [5,54]. Therapeutic targeting here aims to prevent the conversion of circulating classical monocytes into proinflammatory plaque macrophages.

6.2 Plaque Progression: Modulation of Antigen Presentation and Chronic Inflammation

In advanced plaques, intermediate monocytes expand and sustain chronic inflammation through interferon-γ-JAK STAT1 and CD40-CD40 ligand costimulation. Checkpoint inhibition, currently used in oncology, is also being investigated in vascular inflammation. In PAD, altered PD-L1, PD-L2, and TIM-3 expression suggests a role for immune checkpoint modulators [2]. Blockade of IL-1β with CD40-CD40 ligand antagonists or canakinumab (currently tested in cardiovascular diseases) may reduce plaque progression. NLRP3 inhibitors also show promise in reducing monocyte-macrophage inflammatory output [16].

6.3 Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury—Enhancing Reparative Polarization

Following revascularization, monocytes variably contribute to repair or maladaptive inflammation. Therapies targeting metabolic stress, such as HIF stabilizers (e.g., roxadustat) and AMPK activators, may limit ischemia-induced damage while promoting angiogenic repair [35,37]. Antioxidant interventions (e.g., mitochondrial support via PGC-1α induction) further protect endothelial function and reduce reperfusion injury [20]. As shown in experimental PAD models, adoptive transfer of pro-angiogenic monocyte subsets offers a cell-based repair strategy [39].

6.4 Chronic Ischemia and Tissue Regeneration—Supporting Endothelial Surveillance

In advanced PAD, decreased non-classical monocyte numbers are associated with endothelial dysfunction. CX3CR1 agonists or strategies to enhance non-classical monocyte survival may restore endothelial surveillance and microvascular stability. Pro-reparative cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β) may also enhance tissue healing [27,28]. Exercise therapy remains a powerful nonpharmacological strategy that induces ischemia-trained monocytes with enhanced pro-angiogenic and arteriogenic potential [36,39,40].

As shown in Fig. 3, monocyte phenotypes in PAD change dynamically between disease stages and are each associated with distinct molecular targets that form the basis of stage-specific treatment strategies described in more detail in Table 3.

Figure 3: Monocyte phenotypic evolution and stage-specific therapeutic targets in peripheral arterial disease. The diagram illustrates the sequential stages of PAD pathophysiology, the predominant monocyte/macrophage phenotypes in each stage, and the associated molecular targets: 1) Early atherosclerotic development: Targets monocyte recruitment and proinflammatory programming (e.g., CCR2 antagonists, PPAR-γ agonists, statins). 2) Plaque progression and complications: Regulates antigen presentation and chronic inflammation (e.g., PD-L2, TIM-3, LAG-3 modulation; IL-1β blockade; NLRP3 inhibitors). 3) Ischemia-reperfusion and tissue repair: Enhances reparative polarization and angiogenesis (e.g., HIF stabilizers, AMPK activators, cell therapy). 4) Chronic ischemia and remodeling: Promotes endothelial surveillance and tissue remodeling (e.g., CX3CR1 agonists, IL-10/TGF-β, repair-promoting factors). Abbreviations: PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; LAG-3, lymphocyte activation gene-3; M2, alternatively activated macrophage.

CCR2 antagonists, such as PF-04136309, act as allosteric inhibitors by binding to transmembrane domains 3 and 7 and preventing the conformational changes required for Gαq coupling. This blockade disrupts the downstream signaling cascade, preventing both monocyte recruitment and local inflammatory amplification that occurs during tissue infiltration [55].

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation by agents such as metformin promotes oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis. By altering the NAD+/NADH ratio, this metabolic reprogramming shifts monocytes from glycolytic proinflammatory states toward reparative oxidative phenotypes [54].

6.5 Translational Perspectives: Combination, Biomarker Guidance, and Patient Selection

Given stage-dependent changes in monocyte phenotype and function, monocyte-focused interventions in PAD should be adapted to the evolving immune microenvironment rather than implemented as a single strategy. Combination or sequential strategies may be the most effective. For instance, blocking CCR2-CCL2 in the early stage could be followed by metabolic reprogramming to reduce inflammation persistence and then pro-reparative strategies after the revascularization phase. Similarly, combining anti-inflammatory agents with angiogenesis-promoting therapies could help stabilize plaques and improve tissue perfusion. These approaches will need precise dosing and timing to avoid immune suppression during critical repair periods, as seen in combination immunotherapy studies for other vascular inflammatory conditions [16,39].

Patient selection is of critical importance. Tailoring interventions based on biomarker profiles outlined in Section 5 can enhance the effectiveness of stage-specific treatment. Elevated intermediate monocyte counts and plasma CCL2 levels may indicate potential benefits from CCR2 antagonism. Whereas increased PD-L2 or TIM-3 expression may respond to immune checkpoint modulation [2]. Conversely, decreased nonclassical monocyte frequencies may favor CX3CR1-based or pro-reparative approaches [27].

Future clinical trial design should integrate both temporal disease stage and patient-specific immune phenotypes, using biomarker-guided recruitment to increase sensitivity. Ultimately, successful implementation will depend not only on efficacy but also on regulatory guidance, dosing strategies, and real-world applicability in vascular care.

6.6 Clinical Implications for PAD Management

The molecular and cellular insights into monocyte plasticity described above are translating into a variety of clinically important applications for PAD patient management. While most monocyte-targeted interventions are investigational, current evidence supports integrating monocyte biology into patient assessment and treatment decision-making.

Monocyte profiling for risk stratification: Monocyte subset distribution provides prognostic information complementary to traditional cardiovascular risk factors. High intermediate monocyte counts (greater than 10% of total monocytes) identify patients at higher risk for adverse limb outcomes after revascularization, reflecting chronic immune activation that may predispose to accelerated restenosis [38,42]. Similarly, a high monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR > 0.5) independently predicts major adverse limb events and may guide the timing of intervention [38,41]. Conversely, a decreased frequency of nonclassical monocytes (less than 5%) indicates impaired endothelial surveillance capacity and is associated with poor wound healing and a higher risk of amputation [26,38]. These easily measured parameters offer the potential for improved risk stratification beyond ankle-brachial index alone.

Linking immune phenotypes to therapeutic selection: The stage-specific evolution of monocyte phenotypes creates biomarker-guided treatment opportunities. Patients with elevated classical monocyte counts and increased plasma CCL2 levels are biologically amenable to interventions targeting the CCR2-CCL2 axis in early atherosclerotic stages [29,30]. Those with expanded intermediate monocyte populations exhibiting increased checkpoint molecule expression (PD-L2, TIM-3) are candidates for immune checkpoint modulation in stages of plaque progression [2]. Patients with reduced non-classical monocyte counts may benefit from strategies that enhance CX3CR1 signaling or pro-reparative cytokine transmission during chronic ischemic remodeling [27]. This phenotype-target mapping parallels precision oncology approaches and represents a shift toward mechanism-based patient selection.

Monocyte biomarkers as indicators of treatment response: Serial monocyte profiling provides a dynamic assessment of therapeutic efficacy. Reductions in intermediate monocyte counts and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β) during anti-inflammatory therapy suggest favorable immune modulation [16,48]. Restoration of non-classical monocyte frequencies during exercise programs is associated with improved perfusion and functional outcomes and provides molecular evidence of exercise-induced vascular repair [40]. Conversely, persistently elevated classical monocyte levels despite optimal medical therapy may indicate the need for treatment intensification or alternative approaches. These functional biomarkers complement anatomical imaging by revealing underlying immunometabolic responses to treatment.

Mechanistic rationale for established therapies: Understanding monocyte plasticity provides the molecular rationale for current PAD treatments. Statins reduce CCR2 expression in classical monocytes and inhibit glycolytic reprogramming through mTOR-HIF-1α suppression, explaining their anti-inflammatory effects beyond lipid lowering [10,54]. Exercise therapy promotes metabolic reprogramming of circulating monocytes toward oxidative metabolism and pro-angiogenic phenotypes through AMPK activation, mechanistically supporting its potential to modify disease [40]. Low-dose colchicine, currently being evaluated in LEADER-PAD (NCT04774159), directly targets inflammatory amplification that leads to adverse outcomes by impairing NLRP3 inflammasome activation in monocytes [48,49]. These mechanistic insights translate empirical therapies into rationally targeted interventions.

Integration with emerging immunotherapeutic strategies: As monocyte-targeted therapies progress through clinical development, biomarker-guided patient selection will become increasingly important. Cell-based therapies using autologous PBMNCs may benefit patients with high classical monocyte counts, where cells can be directed toward pro-angiogenic phenotypes ex vivo before reinfusion [56–58]. Immune checkpoint modulation may be most effective in patients with dysregulated PD-L2 or TIM-3 expression on circulating monocytes [2]. CCR2 antagonists would logically target patients with high CCL2 and increased classical monocyte recruitment [29,30]. This biomarker enrichment approach maximizes the likelihood of demonstrating efficacy in clinical trials and allows for personalized treatment selection once treatments receive regulatory approval.

Practical considerations for clinical application: Flow cytometry-based monocyte subset profiling can be implemented in most tertiary centers using standard protocols similar to those used for hematologic malignancy immunophenotyping [50,51]. Plasma inflammatory markers (IL-6, CCL2, TNF-α) are accessible through multiplex assays. However, several limitations prevent their immediate widespread adoption: most biomarker-outcome associations originate from relatively small observational studies requiring large-scale validation; monocyte subsets exhibit significant interindividual variability, necessitating serial rather than single-point measurements; and optimal prognostic thresholds have not yet been defined across diverse patient populations. These considerations suggest that monocyte profiling is currently best suited for research settings and specialized vascular centers participating in biomarker validation studies or clinical trials of immunomodulatory therapies.

Advance toward precision vascular medicine: Integrating monocyte phenotyping with genomic, metabolomic, and imaging data holds promise for comprehensive patient characterization that can inform personalized treatment strategies. As evidence from ongoing clinical trials accumulates and standardized protocols emerge, monocyte biology may evolve from a research tool to a clinical decision-support system, particularly for high-risk populations with CLTI or recurrent disease after revascularization. This evolution parallels advances in precision oncology and cardiology, where molecular profiling increasingly guides treatment selection. The ultimate goal is a precision vascular medicine paradigm where immune profiling, combined with anatomic and hemodynamic assessment, allows for optimal matching of patients to mechanism-based interventions, thereby improving both limb and cardiovascular outcomes in PAD.

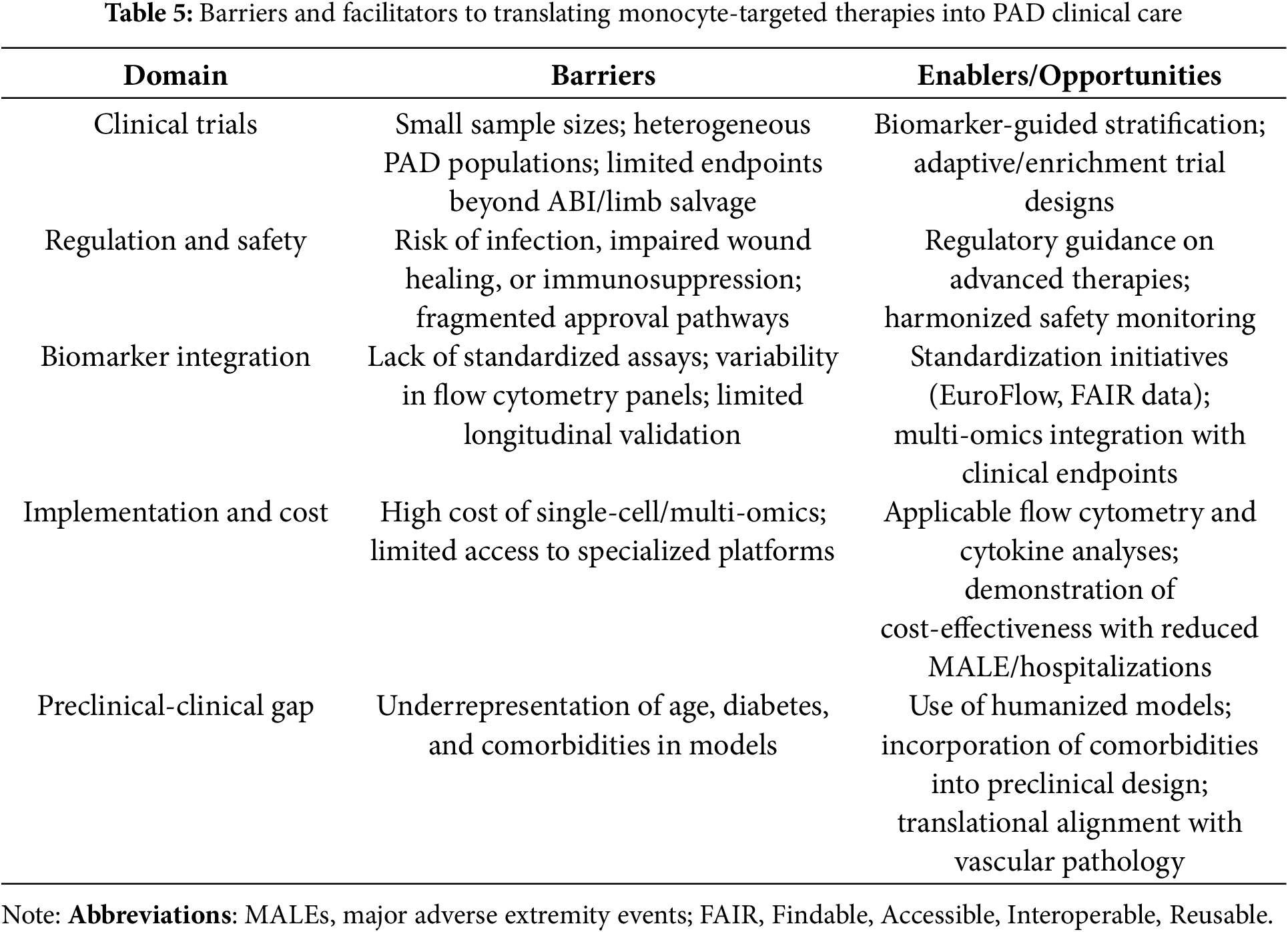

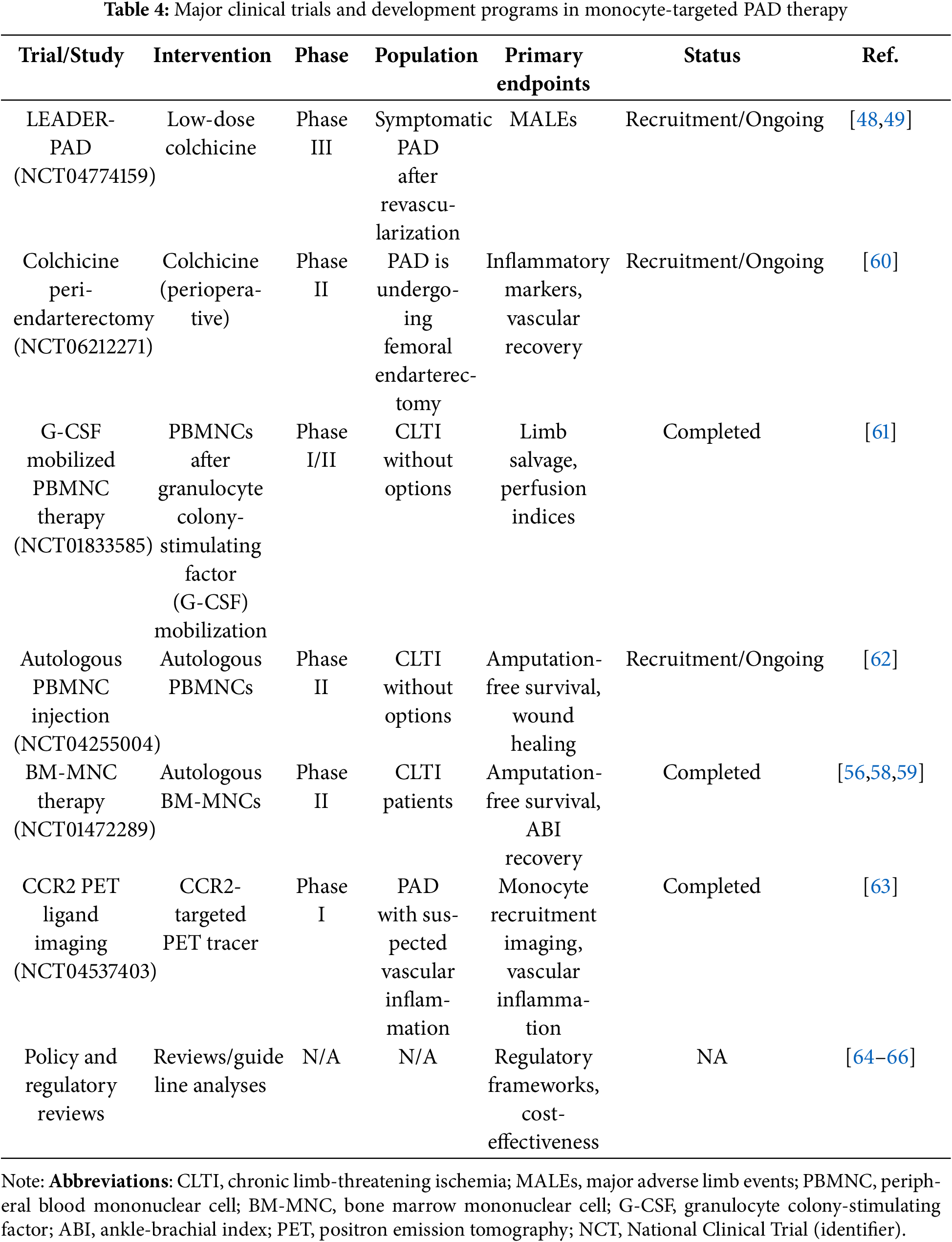

7 Translating Monocyte-Targeted Therapies into the Clinic in PAD

Preclinical studies have shown promising results. Even so, the successful translation of monocyte-targeted interventions into routine care for PAD faces numerous challenges, such as population diversity, comorbidities, and disease stage. Therefore, translating monocyte-targeted therapies into clinical care requires harmonization of clinical evidence, regulatory guidance, biomarker integration, and cost-effectiveness.

Clinical Studies. Many early-stage and repurposing studies are targeting monocyte-related inflammatory pathways in PAD. Low-dose colchicine is being evaluated in the LEADER-PAD trial (NCT04774159), which further explores its anti-inflammatory effect observed in coronary heart disease [48,49]. Cell-based therapies using autologous bone marrow or peripheral blood mononuclear cells have shown potential to improve limb perfusion in the setting of suboptimal critical limb-threatening ischemia, but large, multicenter randomized trials are still needed [56–59]. Ongoing and recent clinical trials targeting monocyte-derived inflammation, immune checkpoints, and cell-based therapies in PAD are summarized in Table 4. These studies highlight strategies ranging from anti-inflammatory small molecules to reparative cell therapies and biomarker-driven imaging. Collectively, these initiatives not only demonstrate the potential for therapeutic modulation of monocyte plasticity while also illustrating the challenges and opportunities of translating immunobiology into vascular medicine.

Regulatory and safety considerations. Interventions that modulate monocyte activation or metabolism must carefully balance efficacy and safety. Oversuppression of inflammation can lead to impaired wound healing or increased infection, while uncontrolled activation can exacerbate tissue damage. Regulatory agencies emphasize aligned endpoints, long-term monitoring, and adaptive trial design before adopting advanced cell- and gene-based therapies [64,66].

Trial methodology. Traditional clinical endpoints such as ankle-brachial index and limb salvage, while centrally important, do not adequately reflect immune modulation. Integration of circulating biomarkers, advanced imaging, and single-cell profiling can provide more sensitive inferences about monocyte-targeted effects [41,47]. Prospective biomarker-guided stratification can align treatment mechanisms with patient subgroups most likely to benefit.

Implementation and cost-effectiveness. While flow cytometry and cytokine analyses are generally applicable, advanced single-cell and multi-omics profiling remains costly and limited to specialized centers [46]. Economic evaluations suggest that implementation will require demonstrating reductions in major adverse limb events, hospitalizations, and amputation rates to justify system-wide adoption [67].

Bridging preclinical and clinical evidence. Translational accuracy is further limited by the underrepresentation of older age, diabetes, and comorbid atherosclerosis in preclinical models [68]. Greater convergence between models and human diseases, combined with innovative adaptive or enrichment trial designs, could accelerate progress by accounting for real-world heterogeneity.

Taken together, the development of monocyte-targeted therapies in PAD will require a laboratory-to-bedside framework that integrates biomarker-guided patient selection, adaptive trial methodologies, regulatory oversight, and pragmatic assessment of cost and implementation. Table 5 provides a structured overview of the main barriers and facilitators affecting this translation.

8 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Monocytes impact nearly every stage of PAD, from the onset of atherosclerotic lesions to ischemia-reperfusion injury and late-stage tissue remodeling. They have a remarkable flexibility, encompassing inflammatory activation, antigen presentation, metabolic reprogramming, and reparative signaling. Advances in high-dimensional profiling, along with the identification of circulating and functional biomarkers, have created opportunities for stage-specific, precision-targeted interventions. The emerging clinical and translational evidence has consistently linked monocyte subsets and their derived mediators to adverse cardiovascular and limb outcomes, highlighting their importance as biomarkers and intervention points. We can also strengthen the translational potential of targeting myeloid plasticity by learning from other immune-mediated conditions. For example, macrophage persistence states identified in rheumatology provide a useful framework for understanding how monocyte plasticity can be exploited in vascular diseases [25].

While early-phase studies and proof-of-concept clinical trials demonstrate feasibility for both pharmacological and cell-based approaches, the translation into practice remains incomplete. Technical barriers, such as variability in sample processing, inconsistent phenotyping, and the cost of advanced multi-omics approaches, limit the use of biomarkers. Therapeutic targeting of monocyte pathways remains largely in early-phase or exploratory studies, and heterogeneity in study design and outcome measures makes comparisons difficult.

Looking ahead, three priorities are essential for advancing the field. First, clinical validation: Large, prospective, multicenter studies with standardized protocols are needed for reproducibility and the establishment of clinical thresholds. Second, precise immunomodulation: Biomarker-guided therapies that align monocyte-targeted interventions with PAD stage and immune phenotype can maximize benefit while minimizing the risks of immunosuppression. Third, integrative translational strategies: Correlating single-cell and multi-omics datasets with clinical endpoints will provide a mechanistic basis for regulatory approval and real-world application.

When combined, these steps can advance the field from definitive immunology to actionable vascular immunotherapy. Monocyte-targeted strategies represent a paradigm shift: a shift from interventions focused primarily on hemodynamics to an integrated precision vascular medicine model in which immune profiling directly informs therapeutic decision-making and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Nurittin Ardic for his critical review of this article.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Gizem Kaynar Beyaz, Ahmet Kirbas, and Sevgi Kalkanli Tas designed the study, drafted the manuscript, and supervised and edited it. Gizem Kaynar Beyaz wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All supporting data is included in the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rodriguez Alvarez AA, Cieri IF, Boya MN, Patel S, Agrawal A, Suarez Ferreira SP, et al. Pro-inflammatory markers as predictors of arterial thrombosis in aged patients with peripheral arterial disease post revascularization. Front Med. 2025;12:1615816. doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1615816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Reitsema RD, Kurt S, Rangel I, Hjelmqvist H, Dreifaldt M, Sirsjö A, et al. Patients with peripheral artery disease demonstrate altered expression of soluble and membrane-bound immune checkpoints. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1568431. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1568431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Dinc R. A review of the current state in neointimal hyperplasia development following endovascular intervention and minor emphasis on new horizons in immunotherapy. Transl Clin Pharmacol. 2023;31(4):191–201. doi:10.12793/tcp.2023.31.e18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, Arya S, Brewster LP, Byrd L, et al. Correction to: 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the management of lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2025;151(14):e918. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kavurma MM, Bursill C, Stanley CP, Passam F, Cartland SP, Patel S, et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction: implications for the pathogenesis of peripheral artery disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1054576. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.1054576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Brevetti G, Giugliano G, Brevetti L, Hiatt WR. Inflammation in peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1862–75. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.918417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Turiel G, Desgeorges T, Masschelein E, Birrer M, Zhang J, Engelberger S, et al. Single cell compendium of the muscle microenvironment in peripheral artery disease reveals capillary endothelial heterogeneity and activation of resident macrophages. bioRxiv. 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.06.21.545899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, Berthiaume F. The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:419. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345(6204):1250684. doi:10.1126/science.1250684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Bekhbat M. Glycolytic metabolism: food for immune cells, fuel for depression? Brain Behav Immun Health. 2024;40(6):100843. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Medbury HJ, Pang J, Bethunaickan R. Editorial: monocyte heterogeneity and plasticity. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1601503. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1601503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Savinetti I, Papagna A, Foti M. Human monocytes plasticity in neurodegeneration. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):717. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9070717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dong Z, Hou L, Luo W, Pan LH, Li X, Tan HP, et al. Myocardial infarction drives trained immunity of monocytes, accelerating atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(9):669–84. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jauregui P. Trained immunity across organs. Nat Immunol. 2024;25(9):1509. doi:10.1038/s41590-024-01958-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang J, Liu YM, Hu J, Chen C. Trained immunity in monocyte/macrophage:novel mechanism of phytochemicals in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1109576. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1109576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Guglietta S, Krieg C. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of monocytes in health and cancer in the era of high dimensional technologies. Blood Rev. 2023;58:101012. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2022.101012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Márquez-Sánchez AC, Koltsova EK. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front Immunol. 2022;13:989933. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.989933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kim KW, Ivanov S, Williams JW. Monocyte recruitment, specification, and function in atherosclerosis. Cells. 2020;10(1):15. doi:10.3390/cells10010015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Qian L, Zhu Y, Deng C, Liang Z, Chen J, Chen Y, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):50. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01756-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Guan F, Wang R, Yi Z, Luo P, Liu W, Xie Y, et al. Tissue macrophages: origin, heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):93. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02124-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HHD, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F, et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science. 2014;345(6204):1251086. doi:10.1126/science.1251086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhao F, Yue Z, Zhang L, Qi Y, Sun Y, Wang S, et al. Emerging advancements in metabolic properties of macrophages within disease microenvironment for immune therapy. J Innate Immun. 2025;17(1):320–40. doi:10.1159/000546476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Dib L, Koneva LA, Edsfeldt A, Zurke YX, Sun J, Nitulescu M, et al. Lipid-associated macrophages transition to an inflammatory state in human atherosclerosis increasing the risk of cerebrovascular complications. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2(7):656–72. doi:10.1038/s44161-023-00295-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Cutolo M, Soldano S, Smith V, Gotelli E, Hysa E. Dynamic macrophage phenotypes in autoimmune and inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2025;21(9):546–65. doi:10.1038/s41584-025-01279-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Olingy CE, San Emeterio CL, Ogle ME, Krieger JR, Bruce AC, Pfau DD, et al. Non-classical monocytes are biased progenitors of wound healing macrophages during soft tissue injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):447. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00477-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Thierry GR, Baudon EM, Bijnen M, Bellomo A, Lagueyrie M, Mondor I, et al. Non-classical monocytes scavenge the growth factor CSF1 from endothelial cells in the peripheral vascular tree to ensure survival and homeostasis. Immunity. 2024;57(9):2108–21.e6. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2024.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Thomas G, Tacke R, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN. Nonclassical patrolling monocyte function in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(6):1306–16. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Guo S, Zhang Q, Guo Y, Yin X, Zhang P, Mao T, et al. The role and therapeutic targeting of the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis in inflammatory and fibrotic diseases. Front Immunol. 2025;15:1497026. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1497026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Georgakis MK, Malik R, El Bounkari O, Hasbani NR, Li J, Huffman JE, et al. Rare damaging CCR2 variants are associated with lower lifetime cardiovascular risk. Genome Med. 2025;17(1):27. doi:10.1186/s13073-025-01456-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Khatana C, Saini NK, Chakrabarti S, Saini V, Sharma A, Saini RV, et al. Mechanistic insights into the oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced atherosclerosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5245308. doi:10.1155/2020/5245308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Laird MHW, Rhee SH, Perkins DJ, Medvedev AE, Piao W, Fenton MJ, et al. TLR4/MyD88/PI3K interactions regulate TLR4 signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(6):966–77. doi:10.1189/jlb.1208763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Batty M, Bennett MR, Yu E. The role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Cells. 2022;11(23):3843. doi:10.3390/cells11233843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhu X, Dingkao R, Sun N, Han L, Yu Q. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α nuclear accumulation via a MAPK/ERK-dependent manner partially explains the accelerated glycogen metabolism in yak longissimus dorsi postmortem under oxidative stress. LWT. 2022;168:113951. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Falero-Diaz G, de A Barboza C, Pires C, Fanchin F, Ling M, Zigmond J, et al. Ischemic-trained monocytes improve arteriogenesis in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(2):175–88. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.317197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Falero-Diaz G, de A Barboza C, Kaiser C, Tallman K, Montoya KA, Patel C, et al. The systemic effect of ischemia training and its impact on bone marrow-derived monocytes. Cells. 2024;13(19):1602. doi:10.3390/cells13191602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yadav S, Ganta VC, Varadarajan S, Ong V, Shi Y, Das A, et al. Myeloid DRP1 deficiency limits revascularization in ischemic muscles via inflammatory macrophage polarization and metabolic reprogramming. JCI Insight. 2025;10(1):e177334. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.177334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Pereira-Neves A, Dias L, Fragão-Marques M, Vidoedo J, Ribeiro H, Andrade JP, et al. Monocyte count as a predictor of major adverse limb events in aortoiliac revascularization. J Clin Med. 2024;13(21):6412. doi:10.3390/jcm13216412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Patel AS, Ludwinski FE, Kerr A, Farkas S, Kapoor P, Bertolaccini L, et al. A subpopulation of tissue remodeling monocytes stimulates revascularization of the ischemic limb. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(752):eadf0555. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.adf0555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pellegrin M, Bouzourène K, Mazzolai L. Exercise prior to lower extremity peripheral artery disease improves endurance capacity and hindlimb blood flow by inhibiting muscle inflammation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:706491. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.706491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Khan H, Girdharry NR, Massin SZ, Abu-Raisi M, Saposnik G, Mamdani M, et al. Current prognostic biomarkers for peripheral arterial disease: a comprehensive systematic review of the literature. Metabolites. 2025;15(4):224. doi:10.3390/metabo15040224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Dopheide JF, Obst V, Doppler C, Radmacher MC, Scheer M, Radsak MP, et al. Phenotypic characterisation of pro-inflammatory monocytes and dendritic cells in peripheral arterial disease. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(6):1198–207. doi:10.1160/TH12-05-0327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Bashore AC, Xue C, Kim E, Yan H, Zhu LY, Pan H, et al. Monocyte single-cell multimodal profiling in cardiovascular disease risk states. Circ Res. 2024;135(6):685–700. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.324457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Kuznetsova T, Prange KHM, Glass CK, de Winther MPJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(4):216–28. doi:10.1038/s41569-019-0265-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Finak G, Langweiler M, Jaimes M, Malek M, Taghiyar J, Korin Y, et al. Standardizing flow cytometry immunophenotyping analysis from the human ImmunoPhenotyping consortium. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):20686. doi:10.1038/srep20686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Brummelman J, Haftmann C, Núñez NG, Alvisi G, Mazza EMC, Becher B, et al. Development, application and computational analysis of high-dimensional fluorescent antibody panels for single-cell flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2019;14(7):1946–69. doi:10.1038/s41596-019-0166-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Mugahid D, Lyon J, Demurjian C, Eolin N, Whittaker C, Godek M, et al. A practical guide to FAIR data management in the age of multi-OMICS and AI. Front Immunol. 2025;15:1439434. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1439434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Colchicine (LEADER-PAD)—ClinicalTrials.gov. LEADER-PAD: Low-dose colchicine for preventing major vascular events in peripheral arterial disease. NCT04774159 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04774159. [Google Scholar]

49. Tardif JC, Cuthill S. Colchicine improves clinical outcomes in patients with coronary disease, will it result in similar benefits in peripheral artery disease? Eur Heart J Open. 2024;4(4):oeae063. doi:10.1093/ehjopen/oeae063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cossarizza A, Chang HD, Radbruch A, Akdis M, Andrä I, Annunziato F, et al. Guidelines for the use of flow cytometry and cell sorting in immunological studies. Eur J Immunol. 2017;47(10):1584–797. doi:10.1002/eji.201646632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Maecker HT, McCoy JP, Nussenblatt R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the human immunology project. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(3):191–200. doi:10.1038/nri3158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Sędek Ł, Flores-Montero J, van der Sluijs A, Kulis J, Te Marvelde J, Philippé J, et al. Impact of pre-analytical and analytical variables associated with sample preparation on flow cytometric stainings obtained with EuroFlow panels. Cancers. 2022;14(3):473. doi:10.3390/cancers14030473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kalina T, Flores-Montero J, van der Velden VJ, Martin-Ayuso M, Böttcher S, Ritgen M, et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):1986–2010. doi:10.1038/leu.2012.122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Wu J, He S, Song Z, Chen S, Lin X, Sun H, et al. Macrophage polarization states in atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1185587. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1185587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Dawson JRD, Kufareva I. Molecular determinants of antagonist interactions with chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5. Biophys J. 2023;122(3):185a. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Idei N, Soga J, Hata T, Fujii Y, Fujimura N, Mikami S, et al. Autologous bone-marrow mononuclear cell implantation reduces long-term major amputation risk in patients with critical limb ischemia: a comparison of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease and Buerger disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(1):15–25. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.955724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Kareti YB, Kumar V, Desai SC, Ramswamy CA, Gowda SS. Stem cell therapy in No option chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Indian J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2025;12(2):117–21. doi:10.4103/ijves.ijves_101_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Sermsathanasawadi N, Pruekprasert K, Chruewkamlow N, Kittisares K, Warinpong T, Chinsakchai K, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell transplantation to treat no-option critical limb ischaemia: effectiveness and safety. J Wound Care. 2021;30(7):562–7. doi:10.12968/jowc.2021.30.7.562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Powell RJ, Marston WA, Berceli SA, Guzman R, Henry TD, Longcore AT, et al. Cellular therapy with Ixmyelocel-T to treat critical limb ischemia: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled RESTORE-CLI trial. Mol Ther. 2012;20(6):1280–6. doi:10.1038/mt.2012.52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Mechanistic Clinical Trial of Colchicine in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06212271 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06212271. [Google Scholar]

61. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01833585 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?term=NCT01833585. [Google Scholar]

62. Autologous Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in Diabetic Foot Patients with No-option Critical Limb Ischemia. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04255004 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04255004. [Google Scholar]

63. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04537403 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?term=NCT04537403. [Google Scholar]

64. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on quality, non-clinical and clinical requirements for investigational advanced therapy medicinal products in clinical trials. EMA/CAT/852602/2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/guideline-quality-non-clinical-clinical-requirements-investigational-advanced-therapy-medicinal-products-clinical-trials-scientific-guideline. [Google Scholar]

65. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Cellular & Gene Therapy Products. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products. [Google Scholar]

66. US FDA. Cellular & Gene Therapy Guidances [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/biologics-guidances/cellular-gene-therapy-guidances?utm_source=chatgpt.com. [Google Scholar]

67. Goudarzi Z, Najafpour Z, Gholami A, Keshavarz K, Mojahedian MM, Babayi MM. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis of rivaroxaban with or without aspirin compared to aspirin alone in patients with coronary and peripheral artery diseases in Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):326. doi:10.1186/s12913-025-12431-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Webster KA. Translational relevance of advanced age and atherosclerosis in preclinical trials of biotherapies for peripheral artery disease. Genes. 2024;15(1):135. doi:10.3390/genes15010135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools