Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hederagenin Alleviated Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss through the Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling in Mice

1 First Affiliated Hospital of Fuyang Normal University, Fuyang Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Biology and Food Engineering, Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Embryo Development and Reproductive Regulation, Fuyang Normal University, Fuyang, 236037, China

2 College of Life Science, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, 230036, China

* Corresponding Authors: Hongcheng Wang. Email: ; Yong Liu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural Compounds in Metabolic Health: Mechanisms and Applications)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 11 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072736

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Objectives: Postmenopausal osteoporosis is the most common form of osteoporosis in clinical practice, affecting millions of postmenopausal women worldwide. Postmenopausal osteoporosis demands safe and effective therapies. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of hederagenin (Hed) for treating osteoporosis and to elucidate its underlying mechanisms of action. Methods: The anti-osteoporotic potential of Hed was assessed by investigating its effects on ovariectomy (OVX)-induced bone loss in mice and on receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclast differentiation in RAW264.7 cells. Network pharmacology analysis and molecular docking were employed to identify key targets, which were subsequently validated experimentally. Results: In vitro, Hed suppressed osteoclastogenesis by inhibiting the formation of osteoclasts and F-actin rings and by down-regulating osteoclast-specific genes (Atp6v0d2 and Acp5). In vivo, Hed significantly ameliorated OVX-induced bone loss, restoring trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N), while reducing trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). Network pharmacology analysis identified 142 overlapping targets linking Hed to osteoporosis, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β, with enrichment in innate immune signaling and osteoclast differentiation. Molecular docking analysis indicated strong binding affinities between Hed and targets such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. Experimentally, Hed was found to decrease RANKL, elevate osteoprotegerin (OPG), and suppress intestinal mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, and TNF-α. Conclusion: Hed exerts significant anti-osteoporotic effects in OVX-induced osteoporosis through a dual mechanism involving the suppression of both osteoclastogenesis and innate immune signaling pathways. These findings highlighted Hed’s novel role in modulating immune-bone crosstalk, offering a promising strategy for treating osteolytic diseases without estrogenic side effects.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileOsteoporosis is a widespread skeletal condition marked by weakened bone strength and an increased risk of fractures, representing a significant global health issue that impacts more than 200 million people around the world [1,2]. Postmenopausal osteoporosis, driven by estrogen deficiency, accounts for 80% of cases in aging women due to an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation that results in a loss of bone mass [3,4]. The ovariectomy (OVX)-induced mice model has become the standard for simulating postmenopausal bone loss, which could recapitulate key features such as trabecular deterioration, cortical porosity, and increased osteoclast activity [5,6]. Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of chronic inflammation in OVX-induced osteoporosis, where estrogen withdrawal amplifies pro-osteoclastogenic cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)) via innate immune activation [7]. While current therapies like bisphosphonates and receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibitors reduce fracture risk by suppressing resorption, their long-term use raises concerns about atypical fractures and impaired bone remodeling [8,9]. Therefore, we urgently need to find new traditional Chinese medicine for targeting osteoimmune dysregulation and bone metabolic imbalance [10].

Hederagenin (Hed) is a naturally occurring oleanane-type triterpenoid saponin, which has received widespread attention for its excellent bioactivities across inflammatory and metabolic disorders [11,12]. Hed is abundantly found in Hedera helix and other medicinal plants, and this compound exhibits remarkable anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties [13]. Mechanistically, Hed suppresses nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) nuclear translocation and inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages, thereby attenuating IL-1β and IL-18 secretion [14]. Previous studies demonstrated that Hed suppressed RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by downregulating c-Fos/NFATc1 signaling in vitro [15]. However, its immunometabolic interplay within the bone microenvironment remains unexplored. These limitations highlight the necessity for a comprehensive preclinical evaluation of Hed’s therapeutic potential.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, encompassing the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38 subfamilies, is a central regulatory pathway that orchestrates cellular responses to inflammatory stimuli [16]. In osteoporosis pathogenesis, MAPK activation exhibits dual effects: p38/JNK pathways promote osteoclast differentiation via AP-1-mediated upregulation of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and cathepsin K, whereas ERK signaling enhances osteoblast survival under oxidative stress [17,18]. Notably, OVX-induced estrogen deficiency triggers sustained MAPK activation in bone marrow macrophages, amplifying RANKL responsiveness and osteoclast hyperactivation [19]. Emerging evidence suggests that MAPK signaling interacts with innate immune receptors, synergistically exacerbating inflammatory bone loss—a process further aggravated by estrogen deficiency [20]. For example, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MAPK/NF-κB axis activation in OVX-induced mice drives IL-6 overproduction, which creates a pro-osteoclastic microenvironment [21,22]. However, the pharmacological targeting of this axis in the protective effect of Hed on the OVX-induced osteoporosis remains poorly understood.

In this study, we systematically evaluated the therapeutic potential of Hed against OVX-induced osteoporosis in a murine model, aiming to determine whether Hed can mitigate bone loss by modulating osteoclast activity and innate immune responses. Using integrated network pharmacology and molecular docking analyses, we further sought to identify potential therapeutic targets and elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of Hed in osteoporosis.

Hederagenin (CAS No. 465-99-6, HPLC > 98%) was purchased from Chengdu Must Bio-Technology (Chengdu, China). The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, catalog No. 96992), Mouse Osteoprotegerin (OPG) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit (catalog No. RAB0493), and phalloidin-TRITC (catalog No. P1951) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (catalog No. A4192101), fetal bovine serum (catalog No. 10099141C), and α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM) (catalog No. 12571063) were purchased from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The RANKL Mouse ELISA Kit (TNFSF11) (catalog No. ab100749, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Staining Kit (catalog No. G1492, Solarbio, Beijing, China), and recombinant murine sRANKL (catalog No. 315-11, Peprotech, NJ, USA) were obtained from the CASMart webshop (Beijing, China). Besides, all other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2 Evaluation of Cell Toxicity

The cytotoxic effects of Hed on RAW264.7 cells were assessed utilizing the CCK-8 assay. Mycoplasma-free RAW264.7 murine macrophage cell line was acquired from the Shanghai Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and maintained as described previously [23]. In summary, cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and were cultured in DMEM that was supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at a temperature of 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Following 24 h of adherence, the cells were exposed to a range of Hed concentrations (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 50, and 100 µM) for another 24 h (Five replicate wells were set for each concentration). Following this, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was introduced into each well, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan GO, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The anti-osteoclastogenic effect of Hed was assessed using TRAP staining. RAW264.7 cells (3 × 103/well) were stimulated with 50 ng/mL RANKL to induce osteoclast differentiation. Based on cytotoxicity data (<10 µM non-toxic), 5 µM was chosen as the maximum concentration and 0.5 µM (1/10 of max) as the minimum. Simultaneously, Hed (0.5 or 5 µM) or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) was added to the α-MEM, which was refreshed every 48 h. Following 7 days of culture, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained for 50 min using a TRAP staining kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (≥3 nuclei) were quantified under a light microscope.

2.4 Analysis of F-Actin Ring Formation by Phalloidin-TRITC Staining

F-actin cytoskeleton in osteoclasts was analyzed through phalloidin-TRITC staining. Briefly, RANKL (50 ng/mL)-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (2 × 104/well) were co-treated with Hed (0.5 and 5 µM) for 7 days. Post-treatment processing included 4% PFA fixation (20 min), 0.5% Triton X-100 permeabilization (10 min), and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (B2064, Sigma-Aldrich) blocking (1 h). Specimens were stained with TRITC-phalloidin (1 µg/mL, 30 min) and DAPI (100 nM, 30 s) in the dark before confocal imaging using a Leica SP5 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.5 Mouse Feeding and Preparation of Osteoporosis Model by Ovariectomy Surgery

45 Female ICR mice, aged 8 weeks and weighing 23–27 g, were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (23 ± 2°C, 50% ± 10% humidity, with a 12 h light/dark cycle), with free access to standard rodent diet and water.

After one week of acclimatization, the mice were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 15 per group) using a random number table: (1) Sham group; (2) OVX group (bilateral ovariectomy); (3) OVX + Hed group (OVX + Hed treatment). For the OVX procedure, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and bilateral dorsal incisions were made to excise the ovaries. Sham-operated mice underwent identical surgical procedures without ovary removal. Beginning in the second week post-surgery, the OVX + Hed group was administered intraperitoneal injections of Hed (0.02 g/kg body weight) every other day for 6 weeks [24], whereas the Sham and OVX groups received equivalent volumes of vehicle (saline containing 5% DMSO).

After 6 weeks of treatment, the mice were humanely euthanized by cervical dislocation. Femurs, small intestine (ileum), and serum samples were harvested for micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), and ELISA, respectively. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Fuyang Normal University (ethical approval code: FYNU2022AP017; date of approval: 20 September 2022).

2.6 Micro-CT Analysis of Osteoporosis in Mice

The trabecular microstructure of mouse femurs was examined using micro-CT (μCT100, Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) under standardized protocols. Femurs from Sham, OVX, and OVX + Hed groups (n = 8/group) were fixed in 4% PFA, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, and scanned at an isotropic resolution of 7.5 µm with the following parameters: 55 kV X-ray voltage, 200 µA current, 230 ms integration time, and 0.5 mm aluminum filter. A region of interest (ROI) spanning 1 mm below the distal femoral growth plate was selected for trabecular bone analysis. Raw projection images were reconstructed using X-ray V4.2 software (Scanco Medical AG). The morphometric parameters, including bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N, 1/mm), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, mm), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, mm), were quantified using Evaluation Program V6.6 software. In the software, the grayscale values were divided into 2000 equal intervals ranging from −1000 to 1000. The optimal threshold was determined as the value at which the binarized image matched the original grayscale image most closely, with no observable increase or decrease in bone area. Based on this process, the grayscale range of 240 to 1000 was selected for bone segmentation. The threshold for bone segmentation was consistently applied across all samples. To ensure reproducibility, three blinded operators independently verified ROIs and parameters.

Osteoclastogenic and inflammatory gene expression was quantified by qRT-PCR analysis. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from RAW264.7 cells or small intestine tissues using an RNAsimple Total RNA Kit (DP419, TIANGEN, Beijing, China) and was spectrophotometrically assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 (A260/A280 = 2.0–2.1). A 20 μL cDNA synthesis reaction was performed using 1 μg of RNA with Oligo dT Primer and Random 6 mers under the following conditions: 15 min at 37°C followed by 5 s at 85°C, using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (RR037A, Takara, Japan). Amplification was performed on a CFX ConnectTM Real-Time System (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) with TB Green® Fast qPCR Mix reagents (Takara, Japan, RR430A) under standard cycling: 95°C/30 s, 40 cycles of 95°C/5 s and 60°C/10 s. Relative expression (2−ΔΔCt vs. Gapdh) was determined through triplicate measurements across three replicates. Primer sequences are detailed in Table S1.

2.8 Biochemical Analysis of Serum

Serum OPG/RANKL levels were measured using ELISA kits. Briefly, the blood from Sham, OVX, and OVX + Hed mice (n = 15/group) was centrifuged (1500× g/10 min/4°C) to isolate serum. After 3-fold dilution, OPG and RANKL serum levels were determined via commercially available mouse ELISA kits with absorbance at 450 nm (Multiskan GO, ThermoFisher Scientific).

2.9 Network Pharmacology Study

Target prediction for Hed and osteoporosis was performed as follows: The three-dimensional structure and SMILES representation of Hed were sourced from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and subsequently imported into CHEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/, accessed on 21 April 2025), ETCM (http://www.tcmip.cn/ETCM/), and the PubChem Target Prediction platform (with a probability threshold of ≥0.1). Additionally, Cytoscape version 3.9.1 (Cytoscape Consortium, San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized to create a network that illustrates the connections between the active drug components and their target genes. To uncover potential therapeutic targets for Hed, the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and OMIM (https://omim.org/) databases were examined using the terms “bone loss” and “osteoporosis.” Moreover, Venn diagrams were used to find common targets between osteoporosis and Hed, identifying overlapping targets as potential Hed-related candidates against osteoporosis. The identified targets were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, including the biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) categories, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis using the DAVID tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). Terms with a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The STRING platform (https://cn.string-db.org/cgi/input.pl, accessed on 21 April 2025) was utilized to construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. The analysis of the core PPI network involved calculating node topology scores, such as node-to-node and subgraph centrality, with the CytoNCA plugin (version 2.1.6). Furthermore, the relationship between the primary PPI targets and innate immune pathways was also further investigated. Source data utilized for the network pharmacology analysis are provided in Supplementary Materials.

2.10 Molecular Docking Analysis

The binding affinity of Hed to pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) was investigated using AutoDock Vina software 1.5.7. Crystal structures of IL-6 (PDB ID: 8QY5), TNF-α (PDB ID: 7KP7), and IL-1β (PDB ID: 2KH2) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. Proteins were prepared by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Gasteiger charges via AutoDock Tools. The 3D structure of Hed was optimized using Avogadro (MMFF94 force field) and converted to PDBQT format. Blind docking was performed with a grid box (60 × 60 × 60 Å) encompassing the entire protein surface. For site-specific docking, grids were centered on functional domains. Each docking run included 20 genetic algorithm iterations, and the top 10 binding poses were ranked by binding energy (ΔG, kcal/mol). Key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) were visualized using PyMOL 2.5.4.

The data was processed utilizing GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with results presented as mean ± SEMs. Statistical comparison was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. A significance level of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 was established.

3.1 Hed Suppressed RANKL-Mediated Osteoclastogenesis in RAW264.7 Cells

To investigate the protective effects of Hed against osteoporosis, we established an in vitro osteoclastogenesis model using RANKL stimulation in RAW264.7 cells. The experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Prior to evaluating osteoclast inhibition, we assessed the cytotoxicity of Hed using the CCK-8 assay. RAW264.7 cells were treated with varying concentrations of Hed (0–100 μM) for 24 h. The results demonstrated that Hed at concentrations ≤10 μM exhibited no significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B), confirming its suitability for subsequent osteoclastogenesis experiments. Based on these findings, a maximum concentration of 5 μM Hed was selected for further studies to ensure cellular viability while allowing for dose-dependent analysis.

Figure 1: Hederagenin suppressed osteoclastogenesis and modulated osteoclast-related gene expression in RAW264.7 cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment design in vitro drawn by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com). (B) Cell viability assay (CCK-8, 24 h) was conducted to assess the cytotoxic effects of various Hed concentrations in RAW264.7 cells. (C,D) Hed dose-dependently inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and multinucleated formation in RAW264.7 cells by TRAP staining. Black arrows indicate osteoclasts. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E,F) Hed disrupted the formation of F-actin rings, which were marked red via phalloidin-TRITC, and the nuclei were counterstained blue with DAPI. White arrows indicate F-actin rings. Scale bar = 100 μm. (G,H) The relative mRNA expression of key genes involved in osteoclast differentiation (Atp6v0d2 and Acp5) in RAW264.7 cells supplemented with RANKL, with or without Hed (0.5 μM, 5 μM) by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, ns: no significance; n = 4

TRAP staining, a hallmark assay for osteoclast activity, was employed to evaluate osteoclast differentiation and multinucleation. As expected, RANKL stimulation robustly induced osteoclast formation in RAW264.7 cells. However, Hed treatment significantly suppressed RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C,D). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that Hed remarkably disrupted F-actin ring formation—a cytoskeletal structure critical for osteoclast bone resorption (Fig. 1E,F). To elucidate the molecular mechanisms, we analyzed osteoclast-related genes by qRT-PCR. Hed downregulated Atp6v0d2, a key subunit of the V-ATPase complex essential for osteoclast function, and suppressed Acp5 (encoding TRAP), a biomarker of osteoclast activity (Fig. 1G,H). These results demonstrated that Hed mitigates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by impairing differentiation, cytoskeletal organization, and resorption-related gene expression, suggesting therapeutic potential for osteoporosis.

3.2 Hed Significantly Ameliorated OVX-Induced Bone Loss in Mice

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of Hed against osteoporosis in vivo, we established an OVX-induced bone loss mouse model (Fig. 2A). Micro-CT, a high-resolution, non-destructive 3D imaging technique, was employed to assess trabecular bone structure and bone density distribution, enabling precise evaluation of microscopic pathological changes in osteoporosis and related bone disorders. Micro-CT analysis demonstrated that Hed treatment significantly ameliorated OVX-induced bone loss and microstructural deterioration in mice (Fig. 2B). Further quantitative assessment revealed that, compared to the Sham group, OVX mice exhibited a pronounced decline in bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N). However, Hed administration (0.02 g/kg, intraperitoneal) partially reversed these alterations, increasing BV/TV and Tb.N by 129% and 89%, respectively (Fig. 2C,D). In addition, OVX mice displayed elevated trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), indicative of severe trabecular bone loss. In contrast, Hed treatment reduced Tb.Sp by 48% compared to the OVX group (Fig. 2E). Although trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) exhibited opposite trends between the OVX and Hed-treated groups, the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that Hed improves trabecular microarchitecture in OVX mice.

Figure 2: Hederagenin alleviated ovariectomy (OVX)-induced osteoporosis by modulating trabecular microstructure in mice. (A) Schematic of experimental design (by Figdraw): Ovariectomized (OVX) mice received intraperitoneal injections of hederagenin (Hed, 0.02 g/kg) every other day for six weeks; sham-operated mice served as controls. (B) Representative micro-CT images of trabecular bone in Sham, OVX, and OVX + Hed groups. Scale bar = 200 μm. (C) Quantitative analysis of key bone structural parameters (Bone Volume/Total Volume, BV/TV) was shown in each group. (D) Quantitative analysis of key bone structural parameters (Trabecular Number, Tb.N) was shown in each group. (E) Quantitative analysis of key bone structural parameters (Trabecular Separation/Spacing, Tb.Sp) was shown in each group. (F) Statistical graph of trabecular thickness (Tb.Th). In (C–F), n = 8 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SEMs; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: no significance

3.3 Network Pharmacology Uncovers the Multi-Target Mechanism of Hed against Osteoporosis

To elucidate the therapeutic mechanism of Hed, we adopted a network pharmacology approach to identify its potential anti-osteoporosis targets and associated pathways systematically. Compound-target network analysis demonstrated that Hed interacts with 199 candidate genes, forming a highly interconnected network with core nodes including prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), MAPK1, nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1 (NFKB1), and IL-6, indicative of its broad regulatory capacity (Fig. 3A). By integrating disease-associated targets from GeneCards and OMIM databases, 7259 osteoporosis-related genes were identified (Fig. 3B). Venn analysis obtained 142 overlapping genes between Hed targets and osteoporosis, encompassing key regulators of bone remodeling (TNF, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)) and immune-inflammatory signaling (IL-1β), suggesting Hed’s dual role in bone metabolism and innate immunity (Fig. 3C). In addition, functional enrichment analysis provided mechanistic insights into Hed’s anti-osteoporotic effects. GO terms were significantly enriched in biological processes such as response to lipopolysaccharide, regulation of apoptotic process, and inflammatory response, with molecular functions including nuclear receptor activity, transcription coactivator binding, and steroid binding (Fig. 3D). KEGG pathway analysis highlighted pivotal pathways, including pathways in lipid and atherosclerosis, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, Th17 cell differentiation, and IL-17 signaling pathway (Fig. 3E). The top 20 KEGG terms exhibited strong statistical significance (p < 0.001, FDR < 0.05), with hub genes (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) recurrently mapped across these pathways. These findings suggest that Hed alleviates osteoporosis by synergistically attenuating pro-osteoclastic inflammation while enhancing osteogenic signaling.

Figure 3: Identification of candidate anti-osteoporosis Hed target genes via network pharmacology. (A) Diagram of the compound-target gene network of Hed. (B) Prediction of target genes related to osteoporosis disease by GeneCards and OMIM databases. (C) Venn diagram depicting the overlapped target genes associated with Hed and osteoporosis. (D) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the anti-osteoporosis Hed targets (BP: biological process; CC: cellular component; MF: molecular function). (E) Bubble chart of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis for potential targets of Hed in anti-osteoporosis. In these diagrams, the size of each circle indicates the number of genes linked to each term, while the p-value is represented by different color gradients

3.4 PPI Network Analysis Uncovers Core Genes Enriched in Innate Immunity Pathways

To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying Hed’s anti-osteoporotic effects, we performed comprehensive PPI network analysis. The constructed PPI network highlighted 20 highly interconnected hub genes (Fig. 4A), including key regulators of bone metabolism and inflammatory signaling such as IL-6, AKT1, TNF, IL-1β, MAPK1, and NFKB1. STRING database analysis demonstrated significant functional clustering among these targets, with modules associated with NF-κB activation, cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, and osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 4B). Notably, IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β served as central network nodes, establishing direct molecular connections between Hed’s therapeutic targets and innate immune regulation.

Figure 4: Identification of candidate targets of Hed in osteoporosis via network pharmacology. (A) The interaction network of Hed-related osteoporosis targets, protein-protein interactions (PPI) network construction, and hub gene screening. (B) The PPI network of core genes in the Hed-osteoporosis target. (C) Hub gene’s KEGG enrichment analysis was carried out using the DAVID tools. (D) Venn diagram of 20 core PPI targets with innate immune signaling pathways-related genes

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of these hub genes demonstrated robust associations with critical osteoporosis-related pathways, including: AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, and Atherosclerosis-related lipid metabolism pathways (Fig. 4C), highlighting Hed’s potential to modulate immune-bone crosstalk. Furthermore, the Venn diagram showed that 3 of the 20 hub genes (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) were directly associated with innate immune signaling (Fig. 4D), indicating Hed’s dual therapeutic mechanism targeting both osteoclast differentiation and inflammatory bone loss pathways. Taken together, these findings underscore Hed’s multi-target capacity to alleviate osteoporosis by disrupting pro-osteoclastic signaling networks and attenuating innate immune-driven bone loss.

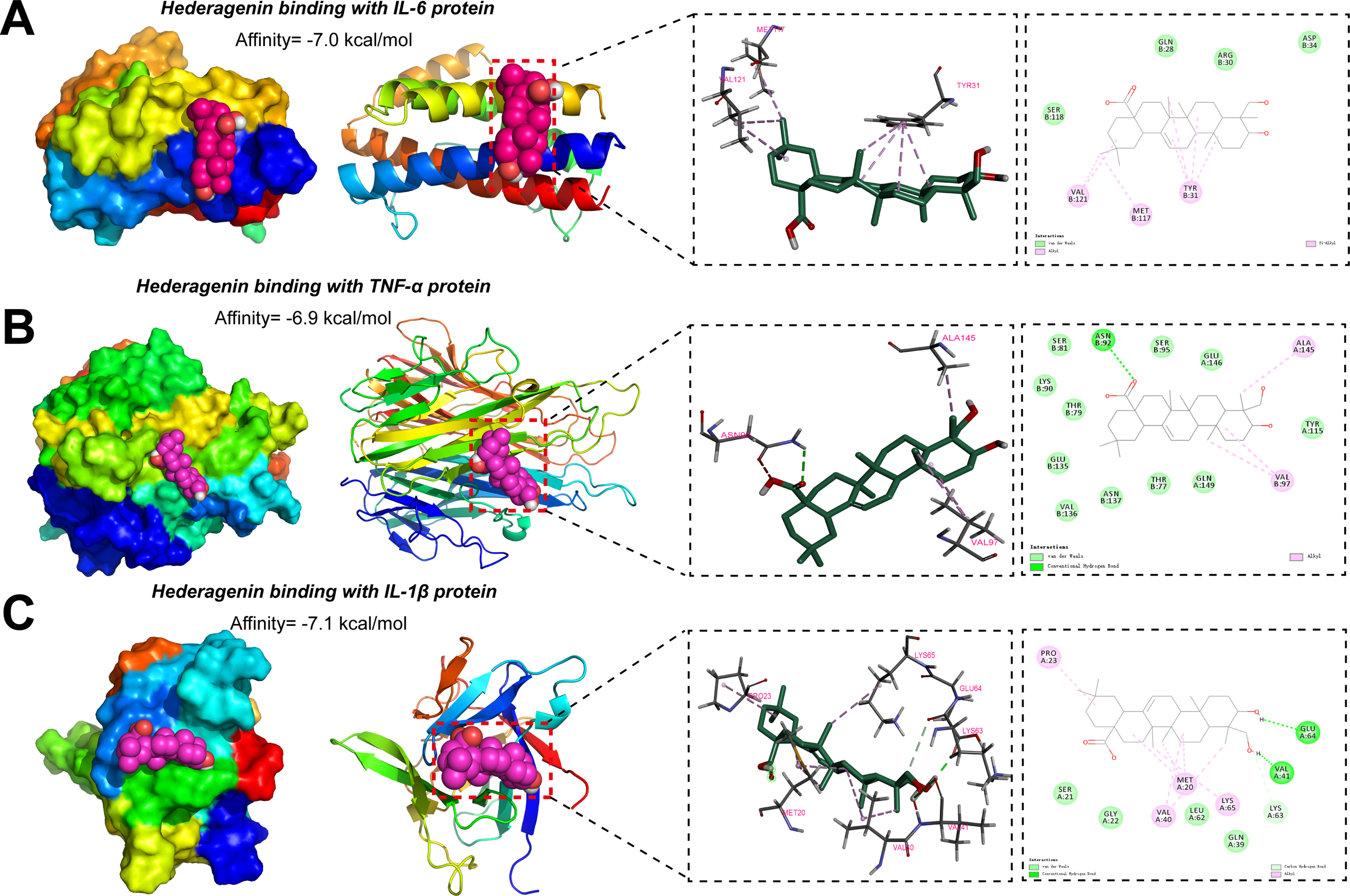

3.5 The Binding of Hed to Core Immune Proteins by Molecular Docking Analysis

The robust binding interactions between Hed and key innate immune proteins were analyzed by molecular docking simulations. Our results suggested that Hed exhibited strong binding affinities to IL-6 (ΔG = −7.0 kcal/mol), TNF-α (ΔG = −6.9 kcal/mol), and IL-1β (ΔG = −7.1 kcal/mol), as calculated by AutoDock Vina. For IL-6, Hed primarily engaged in hydrophobic interactions with MET117, VAL121, and TYR31 near the IL-6 binding site (Fig. 5A). The 2D interaction diagrams further revealed π-π stacking between Hed’s triterpenoid core and aromatic residues, indicative of structural specificity. In TNF-α, Hed formed hydrogen bonds with ASN92, VAL97 and ALA145 within the receptor-binding domain and complemented by hydrophobic interactions, which stabilizing the ligand-protein complex (Fig. 5B). Similarly, Hed bound to IL-1β via hydrogen bonds with MET20, VAL40 and LYS65, critical residues for cytokine activity, while hydrophobic contacts with VAL41 and PRO23 enhanced binding stability (Fig. 5C). These findings further supported Hed as a promising therapeutic agent for osteoporosis, which acting via synergistic modulation of immune-bone crosstalk.

Figure 5: Predicting the theoretical binding ability of Hed with innate immune proteins through molecular docking analysis. (A) The docking pose of Hed binding to IL-6 protein was performed with the AutoDock Vina and visualized with the PyMOL software. (B) The docking pose of Hed binding to tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) protein was performed with the AutoDock Vina and visualized with the PyMOL software. (C) The docking pose of Hed binding to IL-1β protein was performed with the AutoDock Vina and visualized with the PyMOL software. For all these images, the optimal binding positions were displayed in the left panel, and the enlarged 3D diagram and 2D diagram of molecular docking were presented in the right panel. The dashed line represented the distance between hydrogen bonds

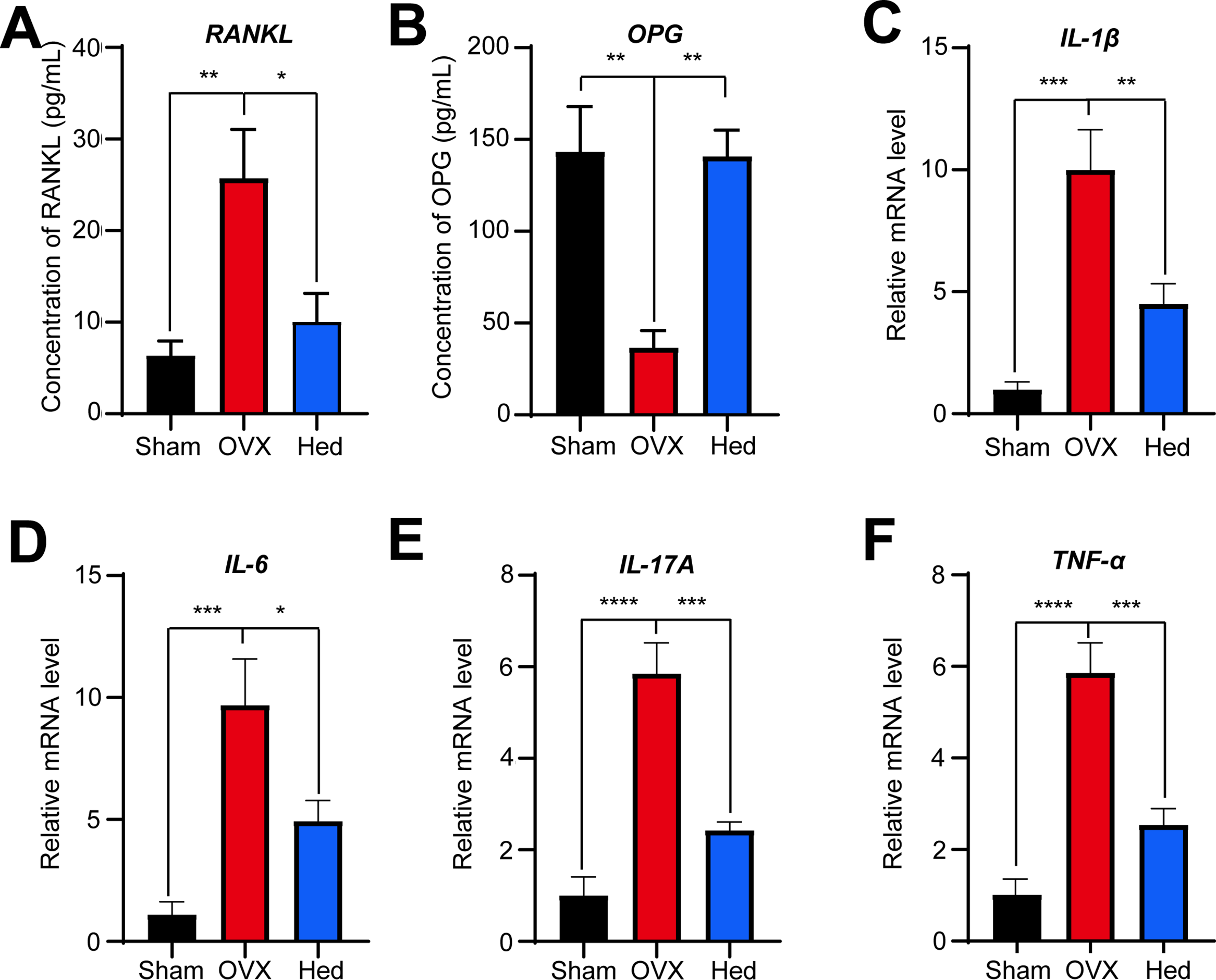

3.6 Molecular Experiments Validate the Regulatory Role of Innate Immunity in Osteoporosis

Consistently, Hed significantly modulated the RANKL/OPG axis and suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in OVX mice, as demonstrated by ELISA and qRT-PCR analysis. Specifically, serum levels of RANKL were markedly elevated in OVX mice vs. Sham controls, whereas Hed treatment significantly attenuated this increase (Fig. 6A). On the contrary, the concentrations of OPG, which were reduced by 74% in the OVX group, were restored to near-normal levels following Hed administration (Fig. 6B). These results suggested that Hed treatment restored the RANKL/OPG ratio—a key driver of osteoclast activation.

Figure 6: Hed dynamically affected the levels of RANKL/OPG and mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice. (A,B) The serum levels of RANKL and OPG in mice were quantified using ELISA (n = 8), respectively. (C–F) The mRNA abundance of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, and TNF-α in the small intestines of mice across different groups was assessed using qRT-PCR analysis. All data were presented as mean ± SEMs (n = 4). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

In the meantime, qRT-PCR revealed that Hed inhibited intestinal mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines linked to bone resorption (Fig. 6C–F). IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, and TNF-α transcripts in OVX mice were up-regulated by 8.9-, 7.8-, 4.8-, and 4.8-fold compared to the Sham group, while Hed treatment significantly suppressed these increases by 55%, 49%, 59%, 57%, respectively. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Hed alleviates OVX-induced osteoporosis through dual regulation of bone remodeling (via RANKL/OPG) and innate immune signaling (via cytokine suppression), positioning it as a multi-target therapeutic agent for osteolytic diseases.

Hederagenin (Hed) is a triterpenoid compound derived from natural plants, which has emerged as a promising therapeutic agent for osteoporosis, particularly through its dual regulation of bone remodeling and innate immune signaling [25,26]. Our study systematically demonstrated that Hed alleviated OVX-induced bone loss by suppressing osteoclastogenesis, modulating the RANKL/OPG axis, and attenuating pro-inflammatory cytokine activity. These findings not only validated the anti-osteoporotic effects of Hed but also unraveled its multi-target mechanisms bridging bone metabolism and immune homeostasis.

The in vitro experiments revealed that Hed potently inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation in RAW264.7 cells. This effect was mediated through two critical mechanisms: disruption of F-actin ring formation and down-regulation of osteoclast-specific genes (Atp6v0d2 and Acp5). F-actin rings are essential for osteoclast resorptive activity because they create a sealed microenvironment for acid secretion and bone matrix degradation [27]. By impairing F-actin organization, Hed directly compromises osteoclast functionality, a mechanism consistent with previous studies on natural compounds like resveratrol and icariin, which also target cytoskeletal dynamics [28,29]. Furthermore, the suppression of Atp6v0d2—a key subunit of the V-ATPase proton pump, suggests that Hed disrupted osteoclast acidification, a prerequisite for bone resorption. Similarly, the reduction of Acp5 (encoding TRAP) aligns with its role as a biomarker of osteoclast activity. These findings demonstrated that Hed is a dual-action inhibitor, which targets both structural and enzymatic components of osteoclasts. In vivo, Hed administration significantly improved trabecular bone parameters in OVX mice, restoring BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp to near normal levels.

The integrative network pharmacology approach provides a systemic framework to explain Hed’s therapeutic efficacy through multi-target immune-bone crosstalk. The identification of 142 overlapping targets between Hed and osteoporosis, including TNF, IL-6, STAT3, MAPK1, and NFKB1, highlighted its capacity to modulate both bone remodeling and inflammatory pathways. Previous studies have shown that Hed reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 [30], NF-κB [23], and p38 MAPK pathways [31]. Notably, the enrichment of innate immune signaling pathways in KEGG analysis aligned with established models of osteoporosis pathogenesis, where chronic inflammation exacerbates bone loss by promoting osteoclast survival and activity [32,33]. Moreover, potential binding between Hed and these inflammatory mediators was supported by molecular docking simulations, which predicted strong binding affinities to TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. For example, IL-6 binding to its receptor (IL-6Rα) activates JAK-STAT3 signaling, which promotes osteoclast formation and survival [34,35]. This dual targeting of cytokines and osteoclast-specific genes explained the compound’s superior efficacy in vivo compared to single-target therapies. Moreover, the overlap between core genes and innate immune pathways suggested that Hed alleviated osteoporosis by attenuating systemic inflammation.

The RANKL/OPG ratio is a major regulator of osteoclastogenesis, and elevated RANKL or reduced OPG in OVX mice created a permissive environment for osteoclast activation, which is a hallmark of postmenopausal osteoporosis [36]. Hed’s ability to reverse this imbalance (reducing RANKL and increasing OPG) suggested its potential to mimic the protective effects of estrogen, as confirmed in our study. Furthermore, the suppression of intestinal pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, TNF-α) by Hed presented a novel dimension to its mechanism: modulation of the gut-bone axis. Emerging evidence implicated that gut-derived inflammation contributes to osteoporosis progression [37]. By targeting intestinal cytokine expression, Hed may block this axis and offer a systemic therapeutic approach distinct from localized bone-targeting agents.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered. First, our micro-CT analysis did not include certain parameters, such as structure model index (SMI), porosity, and other specific cortical parameters. The inclusion of these parameters would have provided a more comprehensive characterization of bone health. Second, due to technical constraints, we were unable to perform bone cellular histomorphometry and TRAP staining. Including these analyses would have provided deeper insight into bone remodeling dynamics and osteoclast activity. Third, our experimental design focused primarily on intestinal inflammatory factors and did not include assessment of bone marrow cytokines. Future studies should examine cytokine profiles in the bone marrow to more fully elucidate the gut–bone axis in this context. Finally, the study did not incorporate a positive control group. Future experiments would benefit from using estrogen or other established agents to better benchmark treatment effects.

Taken together, while our study provided compelling evidence for Hed’s therapeutic potential, several limitations warrant consideration. Although predictions and experimental evidence indicating that Hed treatment modulates the expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β suggest potential binding interactions, direct evidence of such binding remains lacking. Future studies should employ aged female mice or human bone marrow-derived osteoclasts to enhance translational relevance. In addition, clinical trials are essential to evaluate Hed’s safety and efficacy in humans, particularly in comparison to existing therapies like denosumab or romosozumab.

In summary, this study established Hed as a multi-target agent capable of alleviating osteoporosis through synergistic regulation of innate immune signaling and bone remodeling. By suppressing osteoclastogenesis, restoring the RANKL/OPG balance, and attenuating pro-inflammatory cytokine activity, Hed addressed both the skeletal and systemic drivers of bone loss. The integration of network pharmacology and molecular docking analysis demonstrated that Hed effectively reduced bone loss in mice by targeting pathways associated with inflammation. Future research should focus on the mechanistic validation of predicted targets, and the efforts could pave the way for Hed to become a candidate drug in the treatment of osteoporosis and other osteolytic disorders.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Scientific Research Project of Anhui Provincial Health Commission (Grant No. AHWJ2021b063), National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (Grant No. 82160048), Natural Science Foundation Project of Anhui Province (Grant No. 2308085MH265), and Major Scientific Research Project of Anhui Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 2024AH040205).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhitao Yang, Huanyu Cheng, Beibei Li, Luyao Zhang, Chunqing Ma, and Yi Jiao; data collection: Huanyu Cheng, Xinli Liu, Jie Li, and Xin Ming; analysis and interpretation of results: Huanyu Cheng, Xinli Liu, Guanghua Xiong, and Shenjia Wu; draft manuscript preparation: Yong Liu, Hongcheng Wang, Guanghua Xiong, Ibrar Muhammad Khan, and Zhitao Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Fuyang Normal University (ethical approval code: FYNU2022AP017; date of approval: 20 September 2022).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.072736/s1. Table S1: qRT-PCR primer sequences. Source data: for the network pharmacology analysis are provided in Supplementary Materials.

References

1. Liu J, Gao Z, Liu X. Mitochondrial dysfunction and therapeutic perspectives in osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1325317. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1325317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Tonk CH, Shoushrah SH, Babczyk P, El Khaldi-Hansen B, Schulze M, Herten M, et al. Therapeutic treatments for osteoporosis-which combination of pills is the best among the bad? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1393. doi:10.3390/ijms23031393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fischer V, Haffner-Luntzer M. Interaction between bone and immune cells: implications for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;123:14–21. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yao Y, Cai X, Chen Y, Zhang M, Zheng C. Estrogen deficiency-mediated osteoimmunity in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Med Res Rev. 2025;45(2):561–75. doi:10.1002/med.22081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Inoue S, Fujikawa K, Matsuki-Fukushima M, Nakamura M. Effect of ovariectomy induced osteoporosis on metaphysis and diaphysis repair process. Injury. 2021;52(6):1300–9. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.02.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Q, Yao Q, Li C, Yang H, Liang Y, Yang H, et al. Bone protective effects of the polysaccharides from Grifola frondosa on ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in mice via inhibiting PINK1/Parkin signaling, oxidative stress and inflammation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;270(Pt 2):132370. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Livshits G, Kalinkovich A. Targeting chronic inflammation as a potential adjuvant therapy for osteoporosis. Life Sci. 2022;306:120847. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bonnet N, Bourgoin L, Biver E, Douni E, Ferrari S. RANKL inhibition improves muscle strength and insulin sensitivity and restores bone mass. J Clin Investig. 2019;129(8):3214–23. doi:10.1172/jci169317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Saunders SL, Chaudhri K, McOrist NS, Gladysz K, Gnanenthiran SR, Shalaby G. Do bisphosphonates and RANKL inhibitors alter the progression of coronary artery calcification? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2024;14(9):e084516. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Fan K, Hua X, Wang S, Efferth T, Tan S, Wang Z. A promising fusion: traditional Chinese medicine and probiotics in the quest to overcome osteoporosis. FASEB J. 2025;39(5):e70428. doi:10.1096/fj.202403209r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zeng J, Huang T, Xue M, Chen J, Feng L, Du R, et al. Current knowledge and development of hederagenin as a promising medicinal agent: a comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 2018;8(43):24188–202. doi:10.1039/c8ra03666g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang H, Li Y, Liu Y. An updated review of the pharmacological effects and potential mechanisms of hederagenin and its derivatives. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1374264. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1374264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Huang X, Shen QK, Guo HY, Li X, Quan ZS. Pharmacological overview of hederagenin and its derivatives. RSC Med Chem. 2023;14(10):1858–84. doi:10.1039/d3md00296a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang L, Zhao M. Suppression of NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activation and macrophage M1 polarization by hederagenin contributes to attenuation of sepsis-induced acute lung injury in rats. Bioengineered. 2022;13(3):7262–76. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2047406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang K, Lei J, He Y, Yang X, Zhang Z, Hao D, et al. A flavonoids compound inhibits osteoclast differentiation by attenuating RANKL induced NFATc-1/c-Fos induction. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;61:150–5. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2018.05.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Z, Yang Z, Wang S, Wang X, Mao J. Targeting MAPK-ERK/JNK pathway: a potential intervention mechanism of myocardial fibrosis in heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;173:116413. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kar R, Riquelme MA, Hua R, Jiang JX. Glucocorticoid-induced autophagy protects osteocytes against oxidative stress through activation of MAPK/ERK signaling. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(4):e10077. doi:10.1002/jbm4.10077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang MY, An MF, Fan MS, Zhang SS, Sun ZR, Zhao YL, et al. FAEE exerts a protective effect against osteoporosis by regulating the MAPK signalling pathway. Pharm Biol. 2022;60(1):467–78. doi:10.1080/13880209.2022.2039216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Long F, Chen R, Su Y, Liang J, Xian Y, Yang F, et al. Epoxymicheliolide inhibits osteoclastogenesis and resists OVX-induced osteoporosis by suppressing ERK1/2 and NFATc1 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107:108632. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Mi B, Xiong Y, Knoedler S, Alfertshofer M, Panayi AC, Wang H, et al. Ageing-related bone and immunity changes: insights into the complex interplay between the skeleton and the immune system. Bone Res. 2024;12(1):42. doi:10.1038/s41413-024-00346-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Cui H, Li J, Li X, Su T, Wen P, Wang C, et al. TNF-α promotes osteocyte necroptosis by upregulating TLR4 in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2024;182:117050. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3397193/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng X, Wang J, Bi F, Li Y, Xiao J, Chai Z, et al. Protective effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide on ovariectomy-induced cognition reduction in aging mice. Int J Mol Med. 2021;48(1):4954. [Google Scholar]

23. Lee CW, Park SM, Zhao R, Lee C, Chun W, Son Y, et al. Hederagenin, a major component of Clematis mandshurica Ruprecht root, attenuates inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 cells and in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;29(2):528–37. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2015.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Tian K, Su Y, Ding J, Wang D, Zhan Y, Li Y, et al. Hederagenin protects mice against ovariectomy-induced bone loss by inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Life Sci. 2020;244:117336. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li X, Hu M, Zhou X, Yu L, Qin D, Wu J, et al. Hederagenin inhibits mitochondrial damage in Parkinson’s disease via mitophagy induction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;224:740–56. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.09.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Xie ZS, Zhao JP, Wu LM, Chu S, Cui ZH, Sun YR, et al. Hederagenin improves Alzheimer’s disease through PPARα/TFEB-mediated autophagy. Phytomedicine. 2023;112:154711. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gong S, Ma J, Tian A, Lang S, Luo Z, Ma X. Effects and mechanisms of microenvironmental acidosis on osteoclast biology. Biosci Trends. 2022;16(1):58–72. doi:10.5582/bst.2021.01357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Liu X, Wang Z, Qian H, Tao W, Zhang Y, Hu C, et al. Natural medicines of targeted rheumatoid arthritis and its action mechanism. Front Immunol. 2022;13:945129. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.945129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shi G, Yang C, Wang Q, Wang S, Wang G, Ao R, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine compound-loaded Materials in bone regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:851561. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.851561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Fang L, Liu M, Cai L. Hederagenin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of cervical cancer CaSki cells by blocking STAT3 pathway. Chin J Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;35(2):140–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

31. Yang M, Wang J, Wang Q. Hederagenin exerts potential antilipemic effect via p38MAPK pathway in oleic acid-induced HepG2 cells and in hyperlipidemic rats. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2022;94(4):e20201909. doi:10.1590/0001-3765202220201909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Saxena Y, Routh S, Mukhopadhaya A. Immunoporosis: role of innate immune cells in osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:687037. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.687037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang W, Gao R, Rong X, Zhu S, Cui Y, Liu H, et al. Immunoporosis: role of immune system in the pathophysiology of different types of osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:965258. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.965258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Aliyu M, Zohora FT, Anka AU, Ali K, Maleknia S, Saffarioun M, et al. Interleukin-6 cytokine: an overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;111:109130. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Taylor PC, Feist E, Pope JE, Nash P, Sibilia J, Caporali R, et al. What have we learnt from the inhibition of IL-6 in RA and what are the clinical opportunities for patient outcomes? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2024;16:1759720x241283340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Abid S, Lee M, Rodich B, Hook JS, Moreland JG, Towler D, et al. Evaluation of an association between RANKL and OPG with bone disease in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22(1):140–5. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ke K, Arra M, Abu-Amer Y. Mechanisms underlying bone loss associated with gut inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6323. doi:10.3390/ijms20246323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools