Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

USP29 Represses the Osteoclastic Differentiation of Human CD14+ Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells by Stabilizing MafB

1 Department of Joint and Sports Medicine, Zhuhai Hospital Affiliated with Jinan University (Zhuhai People’s Hospital), Zhuhai, China

2 Department of Joint Surgery, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

3 Department of Hepatobiliary Breast Surgery, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

4 Department of Sports Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Speed Capability, The Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Precision Orthopedics and Regenerative Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaofei Zheng. Email: ; Yongheng Ye. Email:

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 9 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2026.071651

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 17 December 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Objectives: Dysregulated osteoclast function contributes to skeletal diseases. However, the specific ubiquitination regulators of the osteoclastogenesis repressor MafB, particularly at the post-translational level, remain undefined. This study aims to identify ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) that deubiquitinate MafB and enhance its stability. Methods: We constructed a MafB-conjugated luciferase and overexpressed 40 individual USPs, measuring changes in luciferase activity. The identified USP was overexpressed in human CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to evaluate its effect. Osteoclast differentiation was assessed through osteoclast marker Integrin alpha-V (CD51) staining and Western blot analysis. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) was performed to assess the interplay. The influence on MafB ubiquitination and degradation was evaluated via immunoprecipitation and Western blot. Finally, MafB was knocked down in the USP-overexpressing PBMCs to analyze its effect on osteoclast differentiation. Results: Overexpression of ubiquitin-specific protease 29 (USP29) significantly increased MafB expression by approximately 75% (p < 0.0001). Elevated USP29 levels strongly inhibited osteoclastic differentiation in CD14+ PBMCs (p < 0.0001). USP29 was found to interact with MafB, markedly reducing its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation in PBMCs (p < 0.001). Knocking down MafB in USP29-overexpressing PBMCs alleviated the inhibitory effect of USP29 on osteoclastogenesis. Conclusion: USP29 acts as a potent stabilizer of MafB, inhibiting osteoclastogenesis in human CD14+ PBMCs, at least in part, by enhancing MafB stability. These findings expand our understanding of USP29’s role and the post-translational regulation of MafB. Furthermore, USP29 serves as a vital factor that controls osteoclast differentiation, and its regulatory function is at least partially mediated by deubiquitinating and stabilizing MafB.Keywords

Osteoclasts are sizable cells containing multiple nuclei that function primarily in the degradation and resorption of bone. This activity creates space for osteoblasts, which undergo osteogenesis to form new bone tissue in areas undergoing growth or remodeling [1,2]. Dysregulated osteoclast function is linked to several skeletal diseases, including osteoporosis and osteopetrosis [3,4]. Osteoclasts developed from hematopoietic precursors derived from the monocyte-macrophage lineage. Their differentiation depends on two key factors: macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells(NF-κB) ligand (RANKL) [5]. M-CSF supports the division and maintenance of osteoclast precursor cells, while RANKL drives their maturation into fully differentiated osteoclasts [2].

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) comprise a heterogeneous group of circulating cells characterized by a singular, round-shaped nucleus. Among these, CD14+ PBMCs are recognized as precursors to osteoclasts [6,7]. Their differentiation into osteoclasts is controlled by an intricate interplay of signaling cascades and regulatory molecules, extending beyond the influences of M-CSF and RANKL [8,9]. These regulatory factors play distinct roles in controlling osteoclast differentiation. For instance, Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells, Cytoplasmic 1(NFATc1), a key transcription factor, stimulates the transcription of essential genes like cathepsin K, Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase(TRAP), and calcitonin receptor to promote osteoclast activation [10]. Osteoclast-Associated Receptor (OSCAR) interacts with its collagen ligands to further promote osteoclast differentiation [11]. Conversely, MafB negatively controls RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation via interfering with NFATc1 along with OSCAR signaling pathways [12].

MafB belongs to the Maf family, which comprises several basic leucine zipper transcription factors that regulate diverse biological processes [13]. Although the role of MafB has been extensively studied, the mechanisms governing its expression—particularly at the post-translational level during osteoclast differentiation—are not yet fully understood.

Ubiquitination is a crucial and reversible post-translational modification essential for modulating protein degradation, intracellular distribution, and function, and this process is mediated by a cascade of enzymes, including E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases [14]. Conversely, deubiquitination is performed by deubiquitinases (DUBs), such as ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), which constitute the largest subfamily of DUBs (more than 50 members) in the human genome [15]. Emerging evidence highlights the critical roles of USPs in osteoclast differentiation. For example, USP7 promotes osteoclast differentiation in human CD14+ PBMCs associated with osteoporosis by deubiquitinating High Mobility Group Box 1(HMGB1) [16], whereas USP18 suppresses the differentiation of osteoclasts by blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway [17]. However, many other USPs’ functions in osteoclast differentiation are unexplored.

Herein, we aimed to systematically screen USPs to determine which candidates could potentially regulate osteoclast differentiation by regulating MafB stability. We hypothesized that USP29 interacts with MafB, attenuates its ubiquitination, and thereby enhances MafB protein stability, which in turn suppresses osteoclastogenesis. The primary objective was to validate the functional role of the USP29-MafB axis in human CD14+ PBMCs and to establish its significance in osteoclast differentiation.

HEK293T cells (Immocell Biotechnology, IML-091, Xiamen, China), which were routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination, were used in this study and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, 10099141, Waltham, MA, USA) as well as 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Immocell Biotechnology, 15070063). Cells were kept in a designated incubator set at 37°C with proper humidity and 5% CO2.

Human CD14+ PBMCs were isolated from PBMCs (Immocell Biotechnology, IMP-H022) using MACS Running Buffer (T&L Biotechnology, 130-091-221, Beijing, China) and NanoSep™ CD14 magnetic beads (TL-625, T/L Biotechnology), strictly following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The purity of the isolated cells was assessed by flow cytometry using a NovoCyteTM Flow Cytometer (Agilent Technologies, 1300, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Cells were stained with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against CD14 at predetermined optimal dilutions (1:100) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. The FITC Mouse IgG2a, κIsotype Ctrl antibody and THP-1 cells were used as the negative staining control and positive biological control, respectively.

To stimulate osteoclast differentiation, CD14+ PBMCs were grown in α-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12571063, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 25 pg/μL M-CSF (Merck, SRP3110, Darmstadt, Germany) and 30 pg/μL RANKL (Yeasen, 90629ES50, China) for six days. The culture medium was replaced every two days to maintain optimal differentiation conditions.

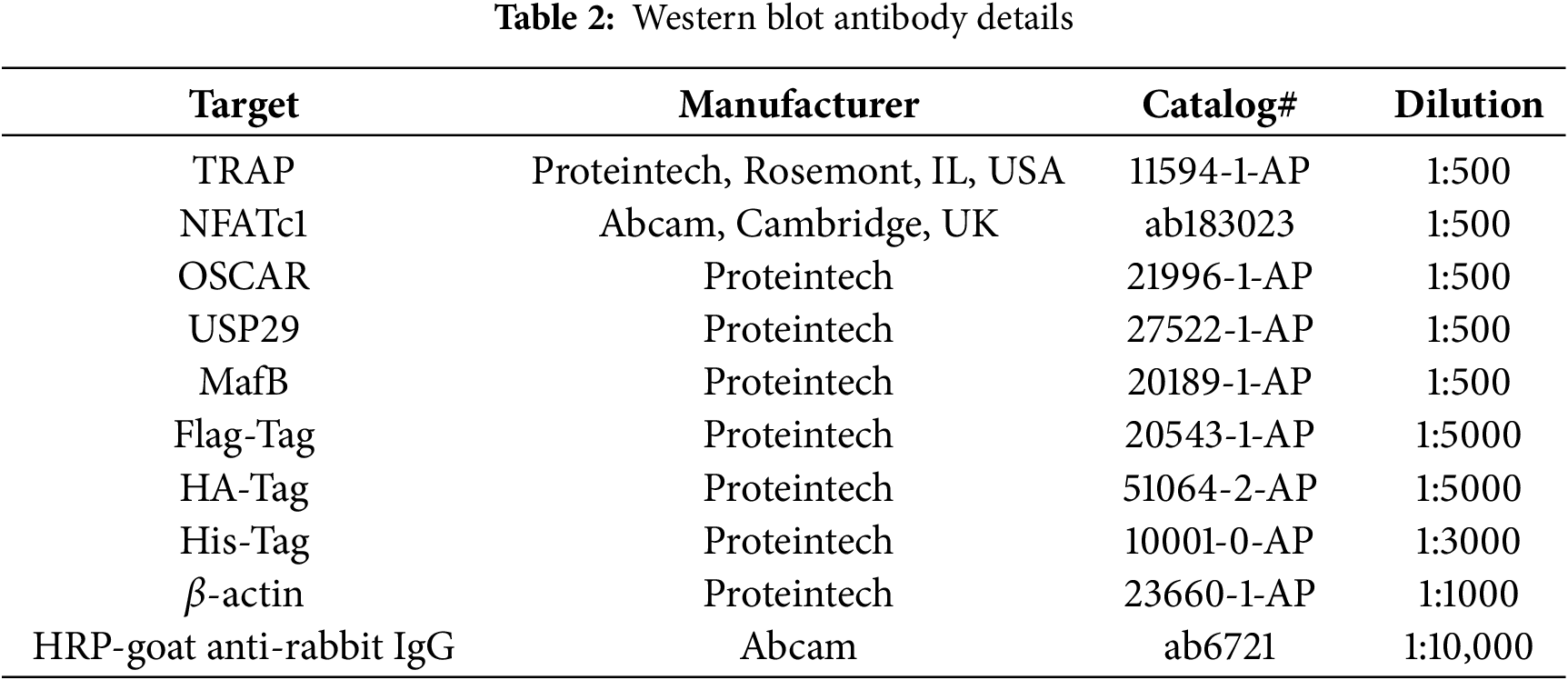

Forty USP overexpression plasmids were acquired from Anti-Hela Biotechnology (Xiamen, China). The cDNA for USP29 was inserted into the pcDNA3.3-HA backbone to construct the HA-USP29 expression (USP29 OE) plasmid. Similarly, the cDNA for MafB was ligated with the pLV-Flag and pmirGLO vectors to produce the Flag-MafB and MafB-Nanoluc plasmids, respectively. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting MafB were integrated into linearized pLKO.1-puro plasmids, creating shMafB-1 and shMafB-2 constructs. The sequence details of primers utilized to create plasmids are provided in Table 1. Additionally, the His-tagged ubiquitin (His-Ub)-encoding plasmid was generated by Miaoling Biotechnology (Miaoling Biotechnology, Wuhan, China).

2.3 Non-Viral Cell Transfection and Lentivirus Infection

Non-viral plasmid introduction into cells was carried out using ExFect Transfection Reagent (Vazyme, T101-01, Nanjing, China). The lentivirus was produced using a third-generation packaging system, which involved co-transfecting the transfer plasmids (pLKO.1-puro-shMafB-1, pLKO.1-puro-shMafB-2, and pLV-Flag-MafB) along with the psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids into HEK293T cells, a service provided by Anti-Hela Biotechnology. The virus titer was determined by measuring the p24 antigen concentration using an ELISA kit (Gelatins, JLC22956, Jiangxi, China). Based on this titer, the multiplicity of infection (MOI) was calculated and optimized to 30 for subsequent experiments.

Stable cell lines were established by culturing cells under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) in medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin (Yeasen, 60210ES25) for seven days, with medium changes every two days. After the selection period, cells that survived were maintained in puromycin-free medium (Immocell Biotechnology, IMC-603-1) for subsequent assays.

HEK293T cells were plated in 96-well plates at 3 × 104 cells/well and cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). After attachment, cells were co-transfected with 0.6 μg MafB-Fluc reporter plasmid and 0.3 μg USP expression plasmid using ExFect Transfection Reagent (Vazyme, T101-01). Following 48 h of incubation, cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, FNN0021) for subsequent luciferase assays. Luciferase activity was assayed after a 10-min reaction at room temperature with the Nano&Firefly-Glo kit (Meilunbio, MA0522, Dalian, China) on a Microplate Luminometer Orion II (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany). For the assay in 96-well plates, the manufacturer recommends adding 80 μL of culture medium per well and then adding 80 μL of detection reagent. For each sample, firefly luciferase activity was adjusted relative to Renilla luciferase activity to ensure accurate comparisons. Data from three independent biological replicates are presented as the mean ± SD.

2.5 CD51 Expression Analysis by Flow Cytometry

Before flow cytometry, human CD14+ PBMCs were counted and resuspended at a density of 1 × 107 cells/mL. The cells were then incubated with an Fc receptor blocking reagent (Beyotime, C1752S) for 10 min on ice, followed by staining with the FlTC anti-human CD51 Antibody (Biolegend, 327906) or its isotype control at a 1:100 dilution for 30 min in the dark. After staining, the cells were washed twice with cold staining buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS) to remove unbound antibodies before being analyzed on a NovoCyteTM Flow Cytometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The analysis of results was performed with the NovoExpress® (v1.4.1, Agilent Technologies).

2.6 Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

RNA isolation and purification were done by the RaPure Total RNA Kit (Magen Biotech, R4011-02, Guangzhou, China). Reverse transcription from RNA into cDNA was done utilizing the All-in-One First-Strand SuperMix (NYBio, EG15133S, Hangzhou, China), following the provided protocol. The ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR Master Mix (Q431-02, Vazyme) and a QuantStudio 3 machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used for qPCR reactions. The relative levels of targets were determined by normalizing to 18S RNA based on the 2−ΔΔCT method. The qPCR primer sequences are listed as follows: USP29-qF: 5′-TTAACAATTCCCGGCGTGGT-3′, USP29-qR: 5′-CGGCAGGAGTTAGGGTTCAG-3′; MafB-qF: 5′-AGACGCCTACAAGGTCAAGTGC-3′, MafB-qR: 5′-CGACTCACAGAAAGAACTCGGG-3′; 18S-qF: 5′-CGACGACCCATTCGAACGTCT-3′, 18S-qR: 5′-CTCTCCGGAATCGAA CCCTGA-3′. Data from three independent biological replicates are presented as the mean ± SD.

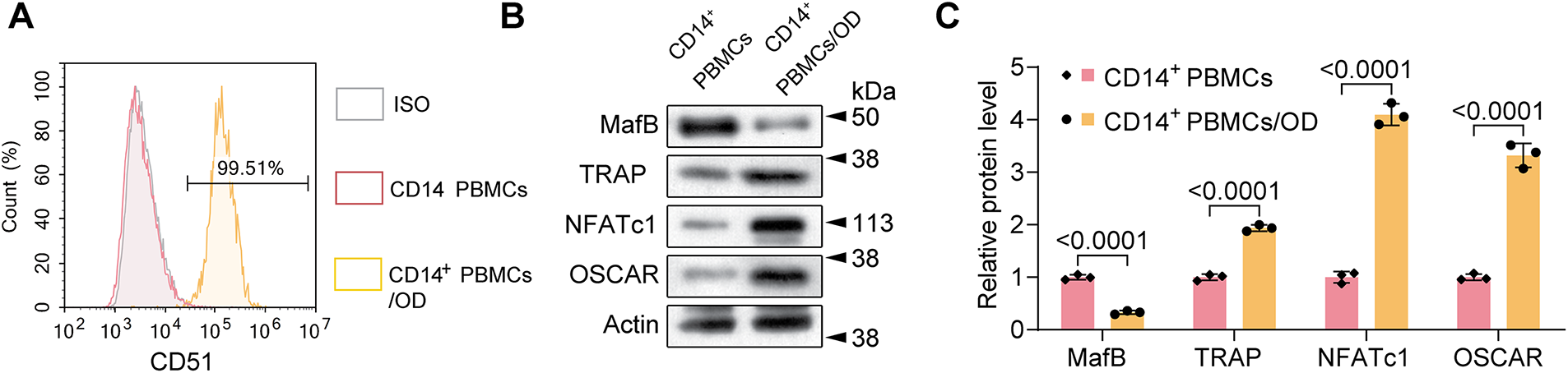

Cells were lysed on ice using RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0013C, Shanghai, China) and thorough homogenization. The supernatants were collected following centrifugation at 1000 × g for 4 min at 4°C, and protein levels were measured with a BCA assay kit (TIANGEN Biotechnology, PA115-02, Beijing, China). Samples were subsequently boiled, resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were treated with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature (RT) for 1 h and then placed in primary antibody solutions at RT for 2 h with continuous shaking. After three washes with 1× Tris-Buffered Saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST, Merck, T9039), membranes were placed in the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. Following another triple-washing of TBST, the membranes were incubated with a Novex™ ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, WP20005), and signals were detected and recorded using X-ray films and a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Band intensities were calculated with ImageJ software (NIH, v1.8.0, Bethesda, MD, USA). Detailed antibody information is provided in Table 2.

2.8 Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

CD14+ PBMCs were transfected with HA-USP29 and/or Flag-MafB with or without His-Ub. One day later, cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Merck, 20-188) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, 329-98-6) on ice for 30 min. The total cell lysate (TCL) was then centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for co-IP analysis of 500 µL protein lysate with 100 µL magnetic beads at 4°C overnight, using the HA-tag Protein IP Assay Kit (Magnetic Beads, Beyotime, P2185S) and Flag-tag Protein IP Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, P2115). Following this, the eluted proteins from pelleted beads were boiled and analyzed by Western blot.

All quantitative experiments were performed with three independent biological replicates (n = 3). For each biological replicate, measurements were conducted in technical triplicates. In the presented bar charts, the mean value of the technical triplicates from each independent experiment is plotted as an individual data point, and the overall bar height represents the mean ± SD derived from these three biological replicates. The normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical significance between groups was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test, as detailed in the respective figure legends. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3.1 USP29 Increases the Expression of MafB in HEK293T Cells

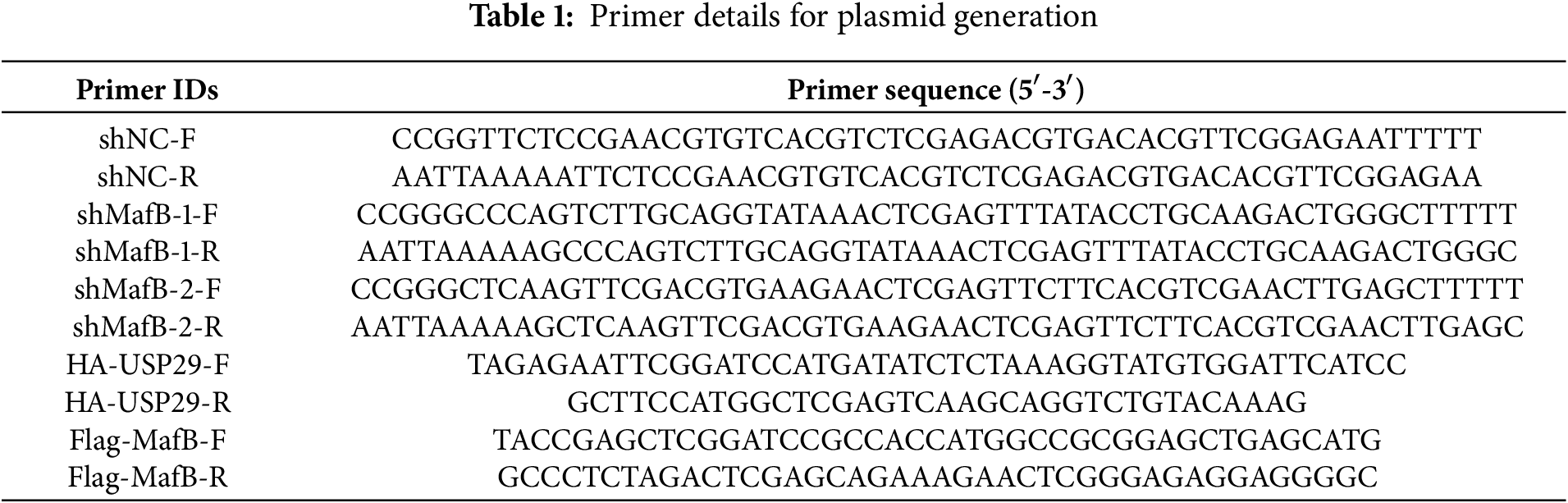

To find out USPs possibly modulating MafB expression and osteoclast differentiation, we created a MafB-conjugated luciferase vector (MafB-Nanoluc) and assessed the effect of individual USP overexpression on its activity. The results showed that HEK293T cells overexpressing USP21, USP29, or USP20 exhibited the highest luciferase activity (Fig. 1A). Further Western blot analysis revealed that only USP29 was able to increase the protein level of MafB (F(3, 8) = 45.76, p < 0.001; Fig. 1B,C). These findings suggest that USP29 may function as a stabilizer of MafB.

Figure 1: USP29 upregulates MafB expression in HEK293T cells. (A) Luciferase assay data showing MafB-Nanoluc activity in HEK293T cells overexpressing individual USPs. (B,C) Western blotting indicates the expression of Flag-MafB in HEK293T cells transfected with HA-USP20, HA-USP21, or USP29. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test

3.2 USP29 Overexpression Inhibits Osteoclastic Differentiation of Human CD14+ PBMCs

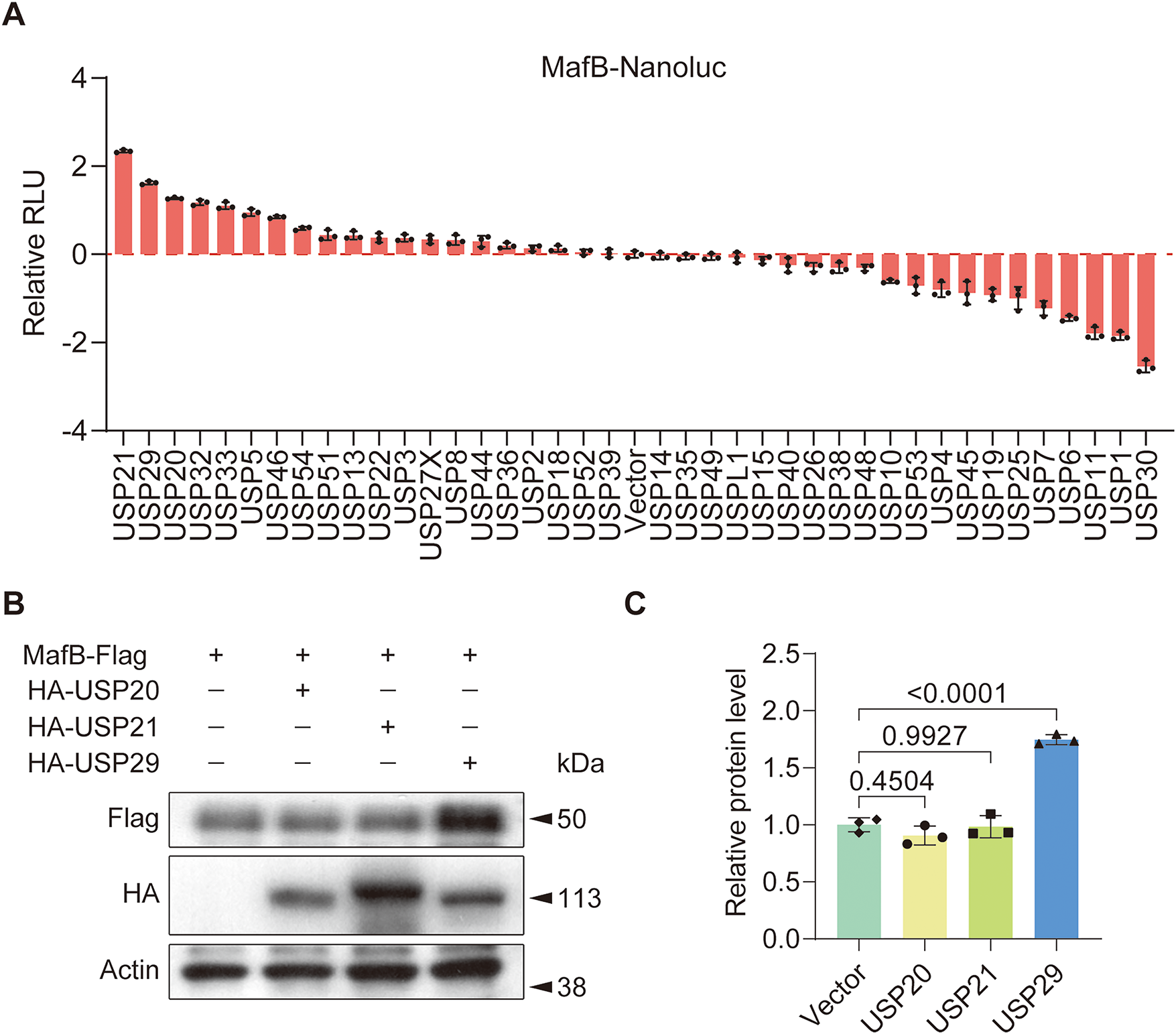

To study USP29’s function in osteoclast differentiation, human CD14+ PBMCs were purified and induced with M-CSF and RANKL. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that differentiated CD14+ PBMCs expressed the osteoclast marker CD51 [18] (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this, Western blot analysis revealed that differentiated cells had lower expression of MafB (F(1, 4) = 102.27, p < 0.001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001) and higher expression of TRAP (F(1, 4) = 81.98, p < 0.001), NFATc1 (F(1, 4) = 359.02, p < 0.001), and OSCAR (F(1, 4) = 217.43, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B,C), confirming successful osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 2: Characterization of the osteoclastic differentiation of human CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). (A) Flow cytometry results showing the expression of CD51 in M-CSF/RANKL-induced PMBCs. (B,C) Western blotting demonstrating the expression of MafB, TRAP, NFATc1, and OSCAR in control and M-CSF/RANKL-induced PMBCs. An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test is utilized for p-value calculation

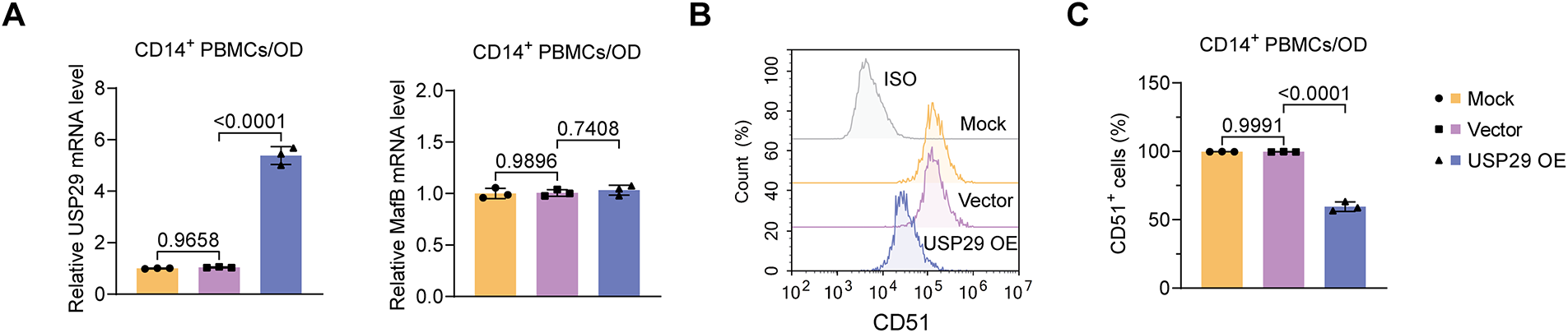

We then overexpressed USP29 in CD14+ PBMCs to assess its impact on osteoclast differentiation. qPCR results indicated that USP29 expression was significantly upregulated in cells transfected with HA-USP29 (F(2, 6) = 422.01, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001), although MafB mRNA levels remained unchanged (F(2, 6) = 0.11, p = 0.7408; Tukey-adjusted p = 0.4776; Fig. 3A). This pattern was confirmed in RAW264.7 cells, where USP29 overexpression likewise did not affect MafB mRNA levels (Fig. A1A,B). Flow cytometry revealed that CD51 expression was reduced upon USP29 overexpression (F(2, 6) = 501.09, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001, Fig. 3B,C). Correspondingly, Western blotting showed that overexpression of USP29(F(2, 6) = 7.87, p < 0.0001;Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001) led to increased MafB protein(F(2, 6) = 55.93, p < 0.0001;Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001) levels and downregulated the expression of TRAP(F(2, 6) = 1.67, p = 0.0097;Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0192),NFATc1(F(2, 6) = 3.93, p = 0.3047; Tukey-adjusted p = 0.3047), and OSCAR (F(2, 6) = 8.71, p = 0.002;Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0060, Fig. 3D,E). This finding was further confirmed in the RAW264.7 cell line (Fig. A1C–H). Together, these findings suggest that USP29 negatively regulates osteoclast differentiation of CD14+ PBMCs, potentially through the stabilization of MafB.

Figure 3: USP29 overexpression represses osteoclastic differentiation of human CD14+ PBMCs. (A) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) revealing USP29 and MafB mRNA levels in PMBCs with the indicated treatments. (B,C) Flow cytometry results indicating CD51 expression in PMBCs with the indicated treatments. (D,E) Western blotting illustrating the USP29, MafB, TRAP, NFATc1, and OSCAR levels in PMBCs under the indicated conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test

3.3 USP29 Interacts with and Deubiquitinates MafB in CD14+ PBMCs

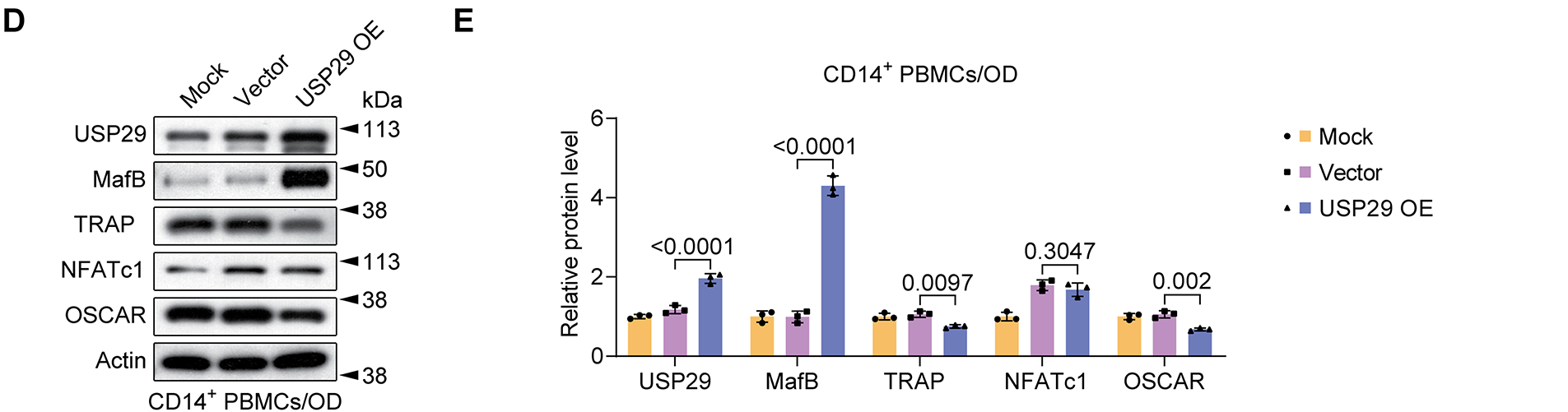

To delineate the mechanism through which USP29 inhibits osteoclast differentiation, we investigated its interaction with MafB. Co-IP assays demonstrated that USP29 strongly interacted with MafB in CD14+ PBMCs (Fig. 4A). Given the DUB activity of USP29, we next examined its effect on the ubiquitination of MafB in these cells. IP results uncovered that USP29 overexpression (F(2, 6) = 79.69, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001) remarkably decreased the ubiquitination level of MafB in CD14+ PBMCs (F(2, 6) = 41.25, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.001, Fig. 4B,C). Additionally, we assessed the degradation of MafB in CHX-treated CD14+ PBMCs, where protein synthesis was inhibited. Western blot analysis showed that USP29 overexpression reduced MafB degradation over an 18-h period (F(1, 4) = 53.60, p = 0.0005; Fig. 4D,E). Together, these results suggest that USP29 stabilizes MafB by deubiquitinating it, thereby preventing its degradation.

Figure 4: USP29 interacts with and regulates the ubiquitination and stability of MafB in human CD14+ PBMCs. (A) Co-IP showing the interplay between USP29 and MafB in PBMCs. (B,C) IP demonstrating the influence of excessive USP29 on MafB ubiquitination in PBMCs. (D,E) Western blotting indicates the degradation of MafB in control and USP29-overexpressing PBMCs. Two-way ANOVA was used for p-value calculation

3.4 MafB Deficiency Mitigates the Inhibitory Effect of USP29 in the Osteoclastic Differentiation of CD14+ PBMCs

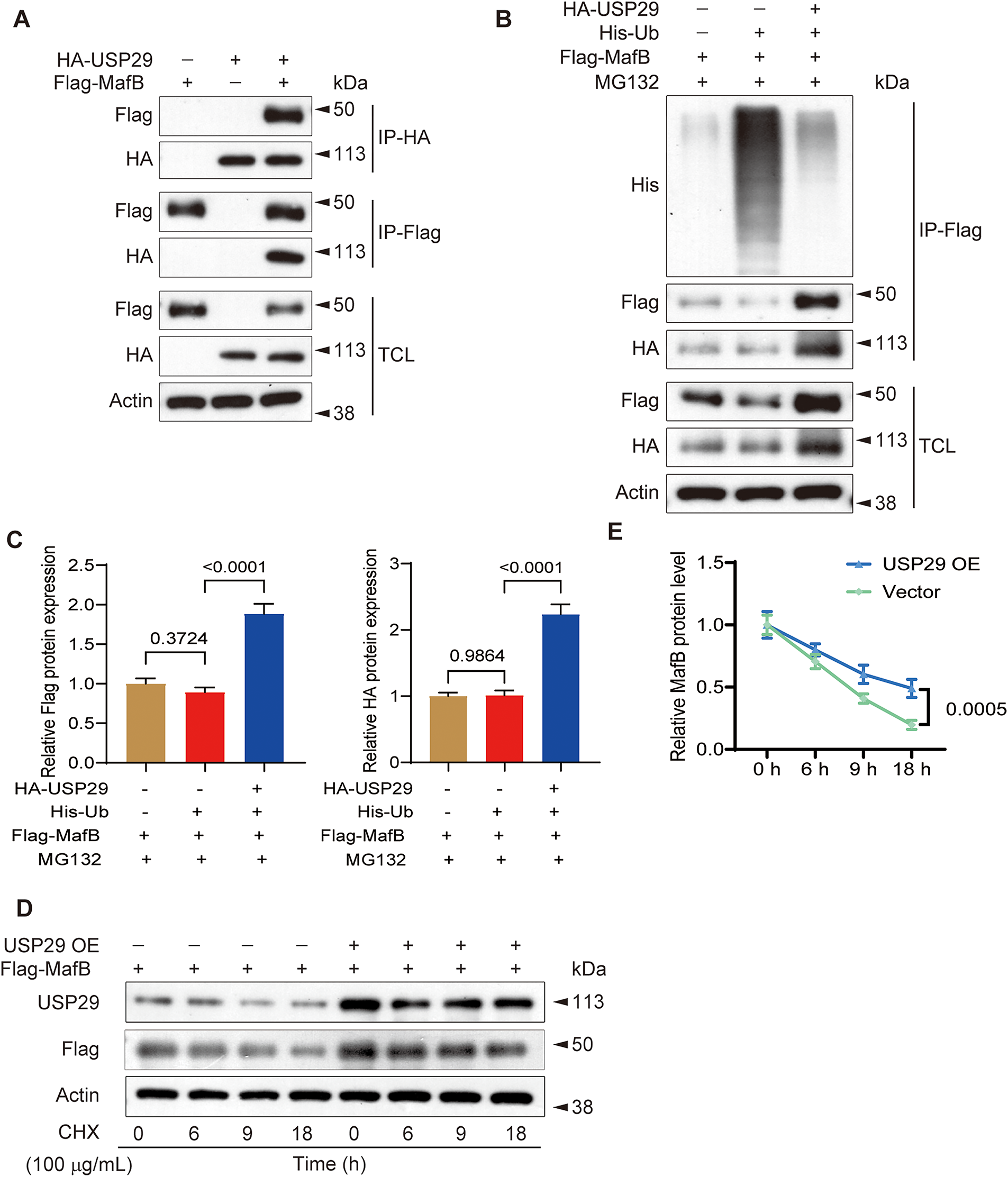

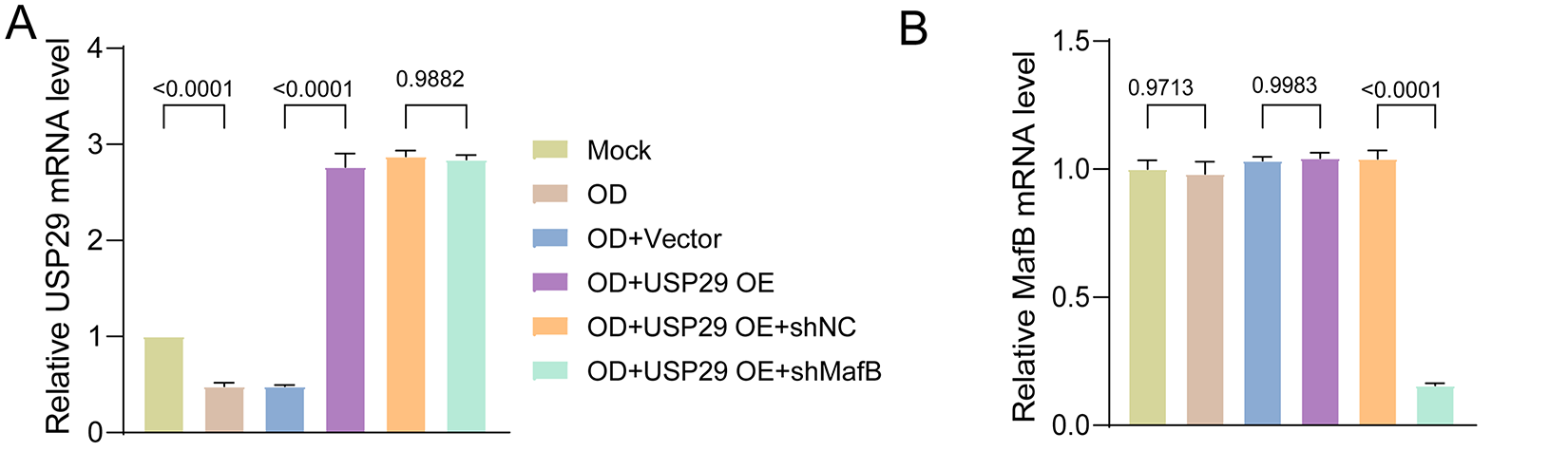

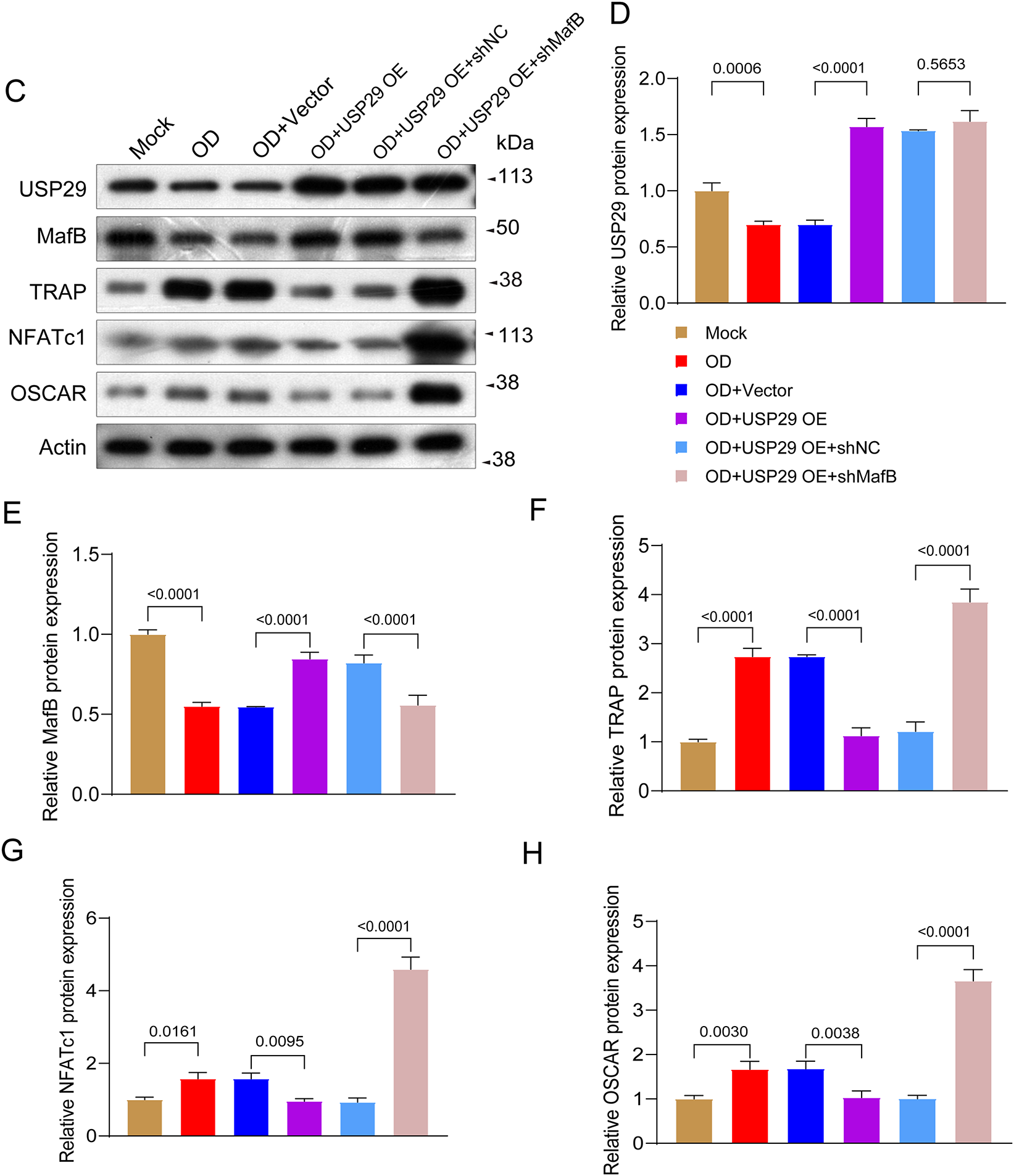

To determine whether MafB is crucial in mediating the effect of USP29 on osteoclastic differentiation of PBMCs, we knocked down MafB in USP29-overexpressing cells. qPCR analysis showed that both shRNAs targeting MafB significantly reduced MafB mRNA levels in HEK293T cells, with shMafB-1 exhibiting a higher knockdown efficiency (F(2, 6) = 31.88, p = 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0194, Fig. 5A), and this was selected for further experiments. Both qPCR (F(2, 6) = 585.13, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001) and Western blot (F(2, 6) = 84.86, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001) results confirmed that MafB expression was efficiently downregulated in USP29-overexpressing CD14+ PBMCs (Fig. 5B,E,F). This effect was corroborated in RAW264.7 cells, where USP29 overexpression also induced a consistent downregulation of MafB at the mRNA level (Fig. A1A,B). Flow cytometry uncovered that CD51 expression in USP29-overexpressing PBMCs was enhanced upon MafB knockdown (F(2, 6) = 1215.15, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001, Fig. 5C,D). Consistent with this, Western blotting showed that the levels of TRAP (F(2, 6) = 79.63, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), NFATc1 (F(2, 6) = 28.66, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), and OSCAR (F(2, 6) = 13.65, p = 0.0011; Tukey-adjusted p = 0.0032) were elevated in MafB-deficient USP29-overexpressing cells compared to USP29-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5E,F). This finding was further confirmed in the RAW264.7 cell line (Fig. A1C–H). Together, these findings further support the conclusion that USP29 inhibits osteoclastic differentiation of CD14+ PBMCs by stabilizing MafB.

Figure 5: MafB deficiency mitigates the inhibition of USP29 on the osteoclastogenesis of human CD14+ PBMCs. (A) qPCR data showing the expression of MafB mRNA in HEK293T cells transfected with shRNAs targeting MafB. (B) qPCR data indicating the expression of MafB and USP29 in PBMCs with the indicated treatments. (C,D) Flow cytometry data indicating the expression of CD51 in PMBCs with the indicated treatments. (E,F) Western blot data demonstrating the expression of MafB, TRAP, NFATc1, and OSCAR in PMBCs with the indicated treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test

While USPs’ function in the differentiation of osteoblasts has been extensively studied [19,20], their involvement in regulating osteoclastogenesis has received less attention. Given that the balance between osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation is essential for normal bone homeostasis [21], it is not surprising that USPs are key players in osteoclast differentiation. Supporting this hypothesis, our study reveals a previously unrecognized function of USP29 in regulating osteoclastogenesis.

The function of USP29 in other contexts has been well-documented. For instance, USP29 promotes tumor metabolism and progression by modulating MYC and HIF1α [22]. It also enhances cellular antiviral responses and autoimmunity by stabilizing cGAS [23], and alleviates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by deubiquitinating TGF-β-activated kinase 1 [24]. Although the role of USP29 in bone biology is not yet fully understood, genetic variants in the USP29 locus have been associated with osteoporosis [25]. While our data provide direct evidence that USP29 regulates osteoclast differentiation, its potential impact on osteoblasts remains to be explored.

MafB expression in hematopoietic cells is modulated by multiple factors like IL-10 and GM-CSF, which respectively induce or reduce its mRNA expression [26]. Additionally, the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways play a role in regulating MafB transcription [12]. Several publications have highlighted the importance of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in regulating MafB stability and degradation. For example, MafB stability is enhanced in protease inhibitor MG132-treated COS7 cells and mouse macrophages [27,28]. Although the specific E3 ligase responsible for MafB ubiquitination remains unidentified, USP7 has been shown to deubiquitinate MafB in HEK293T and myeloma cells [29]. Our findings that USP29 stabilizes MafB in PBMCs further support the idea that post-translational regulation is crucial for MafB expression. However, additional investigation is required for the identification of E3 ligases and DUBs regulating MafB stability in different biological contexts. This study reveals a novel mechanism whereby USP29 promotes osteoclast differentiation by stabilizing MafB. Unlike USP7—which regulates osteoclast formation through HMGB1 deubiquitination [16,30]—or USP26, which stabilizes β-catenin to promote osteogenesis while inhibiting osteoclast differentiation [31,32], USP29 specifically acts by lifting a differentiation “brake” via MafB stabilization, thereby expanding the USP regulatory network in bone homeostasis. Targeting USP29 may thus represent a therapeutic strategy analogous to the USP7 inhibitor P5091.

It is important to acknowledge a limitation of this study. While we provide molecular evidence through the activation of NFATc1 and its target genes, our conclusions primarily rely on cell-based models and lack direct functional assessments of mature osteoclast activity, such as TRAP staining or bone resorption assays. These experiments would be crucial to unequivocally confirm that the observed phenotypic changes in precursor cells translate into altered bone-resorptive function. Therefore, the definitive role of USP29 in regulating the bone-resorbing activity of mature osteoclasts remains an open and important question for future investigation. Notwithstanding this limitation, our discovery of the USP29-MafB axis provides a solid foundation for future work. Further functional validation in primary cells and animal models, as well as investigation of crosstalk with established pathways such as NF-κB, will be essential to understand its role in bone loss and enable clinical translation. USPs often regulate multiple substrate proteins to fulfill their functions. While our data may indicate that MafB is crucial for USP29 to inhibit osteoclastogenesis, it remains to be determined whether USP29 controls this process through additional mechanisms. Furthermore, the specific type of ubiquitination on MafB that is removed by USP29, as well as the interacting domains involved, have yet to be characterized. It is also important to note that our findings are primarily based on in vitro cell biology experiments using a single cell source. Validating these findings in other osteoclast precursors and animal models would be essential to confirm their relevance.

In summary, our study demonstrates that USP29 acts as a potent stabilizer of MafB, inhibiting osteoclastogenesis of human CD14+ PBMCs, at least in part, by enhancing MafB stability. These results expand our understanding of the role of USP29 and the post-translational regulation of MafB. Modulating the USP29-MafB cascade may provide a potential therapeutic strategy for diseases associated with dysregulated osteoclast function.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Shaoyu Hu, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; methodology, Shaoyu Hu, Bingquan Li, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng, Jian Ji, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; software, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng and Jian Ji; validation, Shaoyu Hu, Bingquan Li, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng, Jian Ji, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; formal analysis, Shaoyu Hu, Bingquan Li, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng, Jian Ji, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; resources, Shaoyu Hu, Bingquan Li, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng, Jian Ji, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; writing—original draft preparation, Shaoyu Hu; writing—review and editing, Bingquan Li, Jianfeng Ouyang, Yue Meng, Jian Ji, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; supervision, Shaoyu Hu, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye; project administration, Shaoyu Hu, Xiaofei Zheng and Yongheng Ye. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Yongheng Ye], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| USPs | Ubiquitin-specific proteases |

| co-IP | Co-immunoprecipitation |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand |

| shRNAs | Short hairpin RNAs |

| RT | Room temperature |

| TCL | Total cell lysate |

Appendix A

Figure A1: MafB deficiency mitigates the inhibition of USP29 on the osteoclastogenesis of human CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). (A,B) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) data showing the expression of USP29 (F(5, 12) = 180.43, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001) and MafB (5, 12) = 384.42, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001) mRNA in RAW264.7 cells transfected with shRNAs targeting MafB. (C–H) Western blot data demonstrating the expression of (D) USP29 (F(5, 12) = 128.56, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), (E) MafB (F(5, 12) = 27.55, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), (F) TRAP (F(5, 12) = 106.16, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), (G) NFATc1 (F(5, 12) = 75.18, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001), and (H) OSCAR (F(5, 12) = 54.25, p < 0.0001; Tukey-adjusted p < 0.0001) in PMBCs with the indicated treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test

References

1. Veis DJ, O’Brien CA. Osteoclasts, master sculptors of bone. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2023;18(1):257–81. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031521-040919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Xu F, Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: new insights. Bone Res. 2013;1(1):11–26. doi:10.4248/BR201301003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Funck-Brentano T, Zillikens MC, Clunie G, Siggelkow H, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Cohen-Solal M. Osteopetrosis and related osteoclast disorders in adults: a review and knowledge gaps on behalf of the European calcified tissue society and ERN BOND. Eur J Med Genet. 2024;69:104936. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2024.104936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Da W, Tao L, Zhu Y. The role of osteoclast energy metabolism in the occurrence and development of osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:675385. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.675385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kodama J, Kaito T. Osteoclast multinucleation: review of current literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5685. doi:10.3390/ijms21165685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Sørensen MG, Henriksen K, Schaller S, Henriksen DB, Nielsen FC, Dziegiel MH, et al. Characterization of osteoclasts derived from CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25(1):36–45. doi:10.1007/s00774-006-0725-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xue J, Xu L, Zhu H, Bai M, Li X, Zhao Z, et al. CD14+CD16− monocytes are the main precursors of osteoclasts in rheumatoid arthritis via expressing Tyro3TK. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):221. doi:10.1186/s13075-020-02308-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Amarasekara DS, Yun H, Kim S, Lee N, Kim H, Rho J. Regulation of osteoclast differentiation by cytokine networks. Immune Netw. 2018;18(1):e8. doi:10.4110/in.2018.18.e8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Takegahara N, Kim H, Choi Y. Unraveling the intricacies of osteoclast differentiation and maturation: insight into novel therapeutic strategies for bone-destructive diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(2):264–72. doi:10.1038/s12276-024-01157-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kim JH, Kim N. Regulation of NFATc1 in osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Metab. 2014;21(4):233. doi:10.11005/jbm.2014.21.4.233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Nedeva IR, Vitale M, Elson A, Hoyland JA, Bella J. Role of OSCAR signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:641162. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.641162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kim K, Kim JH, Lee J, Jin HM, Kook H, Kim KK, et al. MafB negatively regulates RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation. Blood. 2007;109(8):3253–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-09-048249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tsuchiya M, Misaka R, Nitta K, Tsuchiya K. Transcriptional factors, Mafs and their biological roles. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(1):175–83. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Mulder MPC, Witting K, Berlin I, Pruneda JN, Wu KP, Chang JG, et al. A cascading activity-based probe sequentially targets E1–E2–E3 ubiquitin enzymes. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(7):523–30. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Davis MI, Simeonov A. Ubiquitin-specific proteases as druggable targets. Drug Target Rev. 2015;2(3):60–4. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818168-3.00004-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lin YC, Zheng G, Liu HT, Wang P, Yuan WQ, Zhang YH, et al. USP7 promotes the osteoclast differentiation of CD14+ human peripheral blood monocytes in osteoporosis via HMGB1 deubiquitination. J Orthop Translat. 2023;40(5):80–91. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2023.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Fan X, Li B, Chai S, Zhang R, Cai C, Ge R. Hypoxia promotes osteoclast differentiation by weakening USP18-mediated suppression on the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):10. doi:10.3390/ijms26010010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Maggiani F, Forsyth R, Hogendoorn PCW, Krenacs T, Athanasou NA. The immunophenotype of osteoclasts and macrophage polykaryons. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(8):701–5. doi:10.1136/jcp.2011.090852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hariri H, St-Arnaud R. Expression and role of ubiquitin-specific peptidases in osteoblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7746. doi:10.3390/ijms22147746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yan J, Gu X, Gao X, Shao Y, Ji M. USP36 regulates the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of hFOB1.19 osteoblast. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):483. doi:10.1186/s13018-024-04893-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kim JM, Lin C, Stavre Z, Greenblatt MB, Shim JH. Osteoblast-osteoclast communication and bone homeostasis. Cells. 2020;9(9):2073. doi:10.3390/cells9092073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tu R, Kang W, Yang M, Wang L, Bao Q, Chen Z, et al. USP29 coordinates MYC and HIF1α stabilization to promote tumor metabolism and progression. Oncogene. 2021;40(46):6417–29. doi:10.1038/s41388-021-02031-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang Q, Tang Z, An R, Ye L, Zhong B. USP29 maintains the stability of cGAS and promotes cellular antiviral responses and autoimmunity. Cell Res. 2020;30(10):914–27. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0341-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen Z, Hu F, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Wang T, Kong C, et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 29 attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by mediating TGF-β-activated kinase 1 deubiquitination. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1167667. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1167667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Alonso N, Albagha OME, Azfer A, Larraz-Prieto B, Berg K, Riches PL, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants which predict the response of bone mineral density to teriparatide therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(7):985–91. doi:10.1136/ard-2022-223618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Daassi D, Hamada M, Jeon H, Imamura Y, Nhu Tran MT, Takahashi S. Differential expression patterns of MafB and c-Maf in macrophages in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;473(1):118–24. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Tanahashi H, Kito K, Ito T, Yoshioka K. MafB protein stability is regulated by the JNK and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;494(1):94–100. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Cui H, Banerjee S, Xie N, Dey T, Liu RM, Sanders YY, et al. MafB regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by sustaining p62 expression in macrophages. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):1047. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-05426-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. He Y, Wang S, Tong J, Jiang S, Yang Y, Zhang Z, et al. The deubiquitinase USP7 stabilizes Maf proteins to promote myeloma cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(7):2084–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.010724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Xie Z, Wu Y, Shen Y, Guo J, Yuan P, Ma Q, et al. USP7 inhibits osteoclastogenesis via dual effects of attenuating TRAF6/TAK1 axis and stimulating STING signaling. Aging Dis. 2023;14(6):2267–83. doi:10.14336/AD.2023.0325-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zheng J, Li X, Zhang F, Li C, Zhang X, Wang F, et al. Targeting osteoblast-osteoclast cross-talk bone homeostasis repair microcarriers promotes intervertebral fusion in osteoporotic rats. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(31):e2402117. doi:10.1002/adhm.202402117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Li C, Qiu M, Chang L, Qi J, Zhang L, Ryffel B, et al. The osteoprotective role of USP26 in coordinating bone formation and resorption. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(6):1123–36. doi:10.1038/s41418-021-00904-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools