Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lithospermic Acid Promotes Osteoblast Proliferation and Differentiation through the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

Department of Orthopaedics, Hangzhou Ninth Hospital, Hangzhou, 311225, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jinxi Zhang. Email: ; DONGAN HE. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072227

Received 22 August 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

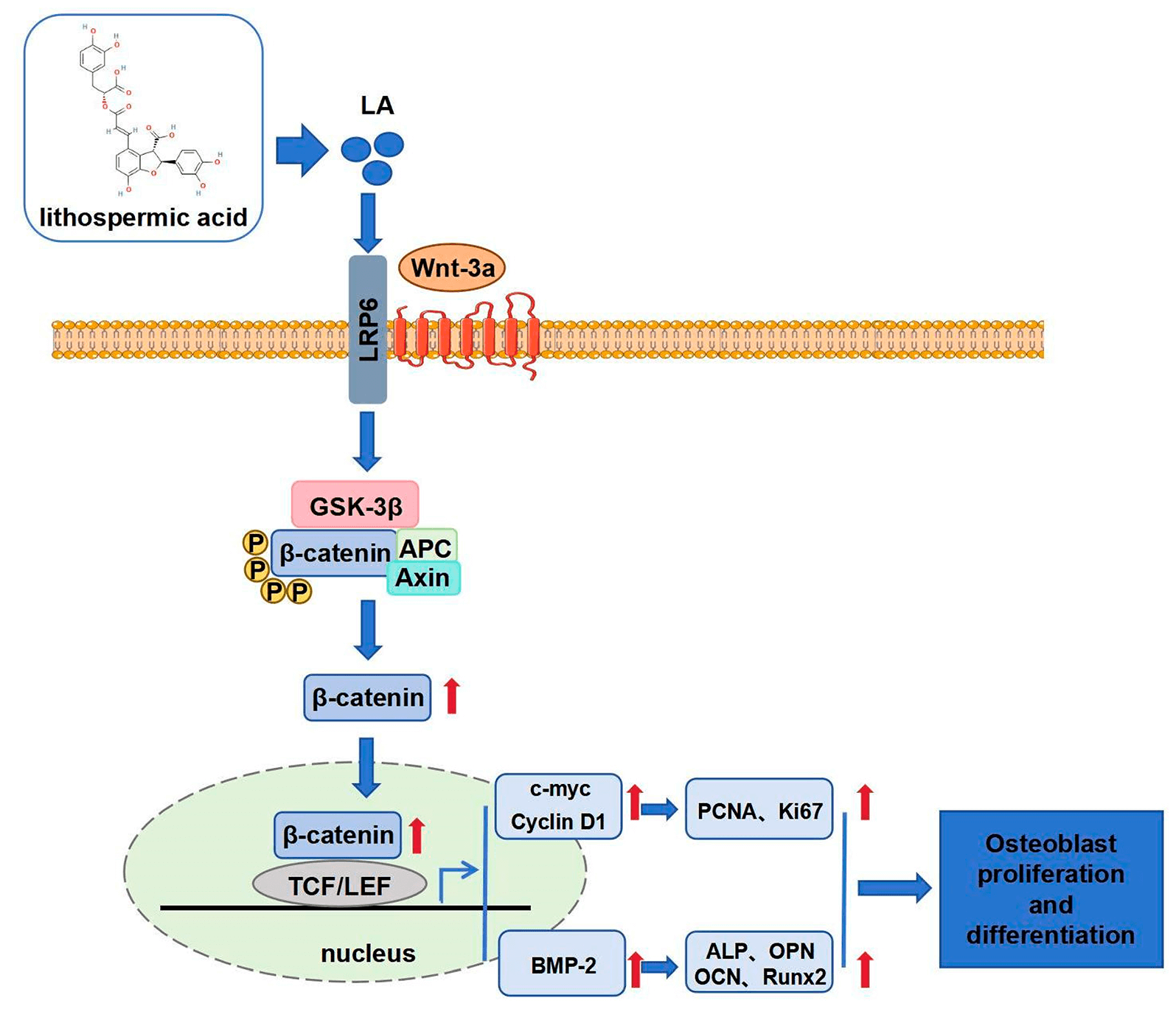

Objectives: Therapeutic strategies for enhancing bone regeneration and combating osteoporosis remain a significant unmet medical need. This study aims to elucidate Lithospermic acid (LA)’s regulatory effects on osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, investigating its viability as a bone-healing agent. Methods: This study employed various cellular and molecular biology experiments to assess the effects of LA on the viability, proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis, differentiation, mineralization, and migration of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. Immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses were conducted to detect the expression of proteins related to the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, investigating the regulatory mechanisms by which LA promotes osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. Additionally, Wnt inhibitor dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) and β-catenin-silenced cell models were used to further validate the role of LA in modulating this signaling pathway. Results: LA significantly promoted osteoblast proliferation without apparent cytotoxicity. Flow cytometry showed that LA regulated the cell cycle by reducing G0/G1 phase arrest and promoting G2/M phase progression. Western blot results indicated that LA upregulated the expression of proteins associated with cell proliferation and enhanced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. Immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses further confirmed that LA markedly increased the expression of Wnt and β-catenin, facilitating β-catenin nuclear translocation. Treatment with the DKK-1 inhibitor significantly diminished the proliferative and differentiation-promoting effects of LA, confirming the critical role of this pathway. β-catenin knockdown experiments further substantiated its central role in LA-mediated regulation. Conclusion: This study confirms that LA promotes osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, mineralization, and migration by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

As a vital structural element of the human body, bone performs essential physiological roles including mechanical support, organ protection, and locomotion facilitation while simultaneously contributing significantly to systemic metabolic regulation [1–3]. Recent advances in bone biology have revealed that skeletal tissue represents a dynamic, metabolically active organ system rather than an inert structural framework [4,5]. Bone tissue can achieve self-repair and regeneration through complex molecular and cellular mechanisms [6], making it one of the few organs in the human body with regenerative potential. Critical to skeletal physiology is the tissue’s inherent regenerative capacity, which becomes activated following various insults, including trauma-induced fractures, oncological resections, or metabolic bone diseases, ultimately leading to morphological and functional restoration [7,8]. However, the bone regeneration process is influenced by various factors, including age, overall health, local blood supply, mechanical environment, and molecular signaling pathways [9–11]. Impairment of osseous regenerative potential can result in complications, including fracture nonunion, delayed osseous consolidation, or persistent bone defects, significantly compromising patient outcomes and quality of life [12,13]. Consequently, elucidating the molecular pathways and regulatory circuits governing bone regeneration holds substantial clinical relevance for both preventive and therapeutic approaches in orthopedic medicine.

Understanding osteoblast ontogeny and differentiation mechanisms represents a central theme in bone regeneration studies. These bone-forming cells originate from multipotent mesenchymal stem cells, with their differentiation program being meticulously regulated by several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways, including bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/Smad, Notch, and Wnt/β-catenin systems [14–16]. Among various signaling pathways, Wnt/β-catenin stands out as a master regulator of bone formation. Its activation stimulates both the expansion of osteoblast precursors and their subsequent differentiation, while simultaneously accelerating bone matrix calcification [17,18]. Numerous experimental studies have established that targeted stimulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling substantially augments bone formation processes. For example, Wnt3a treatment enhances osteogenic differentiation [19], while mice with specific knockout of β-catenin exhibit severe bone loss [20]. Although Wnt/β-catenin signaling is fundamental to bone formation, uncontrolled activation may contribute to degenerative joint disease and tumorigenesis [21,22], underscoring the critical need for targeted pathway regulation.

Lithospermic acid (LA) represents a bioactive, aqueous-soluble polyphenolic compound isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza, whose therapeutic applications in traditional Chinese practice stem from its anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and wound-healing properties [23,24]. Contemporary pharmacological research has revealed that LA exhibits multiple therapeutic potentials beyond its traditional uses, demonstrating significant antitumor activity, free radical scavenging capacity, and immunomodulatory properties [25,26]. The expanding therapeutic profile of LA contrasts with the limited understanding of its skeletal effects.

This study bridges this knowledge gap by systematically investigating LA’s osteogenic potential through the lens of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, a central pathway in bone biology. By characterizing LA’s ability to activate this pathway and enhance osteoblast function, we aim to provide mechanistic support for its application in bone repair.

2.1 Cell Culture and Transfection

MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts (SCSP-5218) were acquired from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China). Cellular propagation was maintained in α-MEM (Gibco, 12571063, Grand Island, NY, USA) enriched with 10% FBS (Gibco, A5669701) and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (1% penicillin-streptomycin, Pricella, PB180120, Wuhan, China), incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 saturation. The nutrient medium was renewed every third day.

Osteogenic differentiation was induced by culturing MC3T3-E1 cells in MEM-α containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, along with osteogenic supplements: 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (MCE, HY-126304, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma, 1043003, St Louis, MO, USA), and 100 nM dexamethasone (265005, Sigma). Cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2, with medium changes every 3 days (days 1–14) followed by every 2 days (days 15–21) throughout the 21-day differentiation protocol.

The β-catenin knockdown model was generated using RNA interference technology. Briefly, β-catenin-specific siRNA (Final concentration: 50 nM; Si-β-catenin: CCCUCAGAUGGUGUCUGCCAUUGUA-sense, UACAAUGGCAGACACCAUCUGAGGG-antisense) and negative control siRNA (UUCUCCGAACGUCACGUTT-sense, ACGUGACGUUCGGAGAATT-antisense; RIBOBIO, Suzhou, China) were delivered into 70%–90% confluent MC3T3-E1 cells (cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/cm2) using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection system (Invitrogen, L3000150,Carlsbad, CA, USA). The transfection mixture containing siRNA, P3000 reagent, and Lipofectamine 3000 in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, 11058021) was incubated for 15 min before application. After 6 h of exposure, cells were maintained in fresh α-MEM medium for 48 h before collection.

To determine the optimal non-toxic concentrations and exposure times of LA, cell viability was quantitatively analyzed via MTT assay. MC3T3-E1 cells were plated in 96-well culture plates at an initial density of 5 × 10³ cells/well. Following 24/48 h exposure to LA (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μM, MCE, HY-N0823,), 10 μL of MTT reagent (5 mg/mL, Beyotime, C0009, Shanghai, China) was introduced to each well, followed by 4 h incubation under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). Following this step, each well received 100 μL of formazan dissolution buffer and was subjected to an additional 4 h incubation period. Optical density measurements were then performed at 570 nm wavelength using the microplate reader (Benchmark™ Plus, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cell viability (%) = [(ODexperimental group − ODcontrol group)/(ODcontrol group − ODblank group)] × 100%.

2.3 Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Assay

The cytotoxic effects of LA on cell membrane stability were quantitatively analyzed using the LDH release assay. After seeding cells (5 × 103 cells/well) in 96-well plates, they were treated with graded LA concentrations (25, 50, 100 μM) for a 24 h period. Processed samples were centrifuged at 400× g for 5 min post-lysis, with the obtained supernatants evaluated for LDH activity according to standardized protocols (Solarbio, BC0680, Beijing, China). Microplate analysis (BioTek, Synergy H1, Winooski, VT, USA) at 450 nm wavelength enabled cytotoxicity determination, resulting in the identification of three working concentrations (25, 50, 100 μM) for extended experimentation. The LDH activity (U/mL) was calculated by establishing a standard curve based on the kit’s standards. The LDH release rate (%) was determined using the formula: (LDHexperimental group − LDHblank control group)/(LDHmaximum enzyme activity control group − LDHblank control group) × 100%.

The study employed a controlled experimental design to evaluate LA’s influence on osteoblast function, incorporating four treatment conditions: an untreated control group alongside three LA-treated groups (25, 50, and 100 μM concentrations). Following a standardized 24 h exposure period, all groups underwent a comprehensive analysis to assess proliferative and differentiation capacity.

The study design included four treatment arms to dissect LA’s molecular actions: a vehicle control group, a group receiving 100 μM LA monotherapy, a group treated with the Wnt antagonist DKK-1 (100 ng/mL, MCE, HY-P72969), and a combination group receiving both 100 μM LA and DKK-1 to evaluate their functional interplay in osteoblast regulation. To specifically investigate ββ-catenin’s essential involvement, the study incorporated two additional intervention groups: cells receiving 100 μM LA with non-targeting control siRNA (si-NC) and those treated with 100 μM LA plus β-catenin-specific siRNA (si-β-catenin). Post-transfection administration of LA enabled precise evaluation of β-catenin’s contribution to LA’s regulatory effects.

The EdU incorporation assay was performed to assess proliferative activity. Plate cells at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. After 24 h LA treatment, cells were labeled with 50 μM EdU (37°C, 2 h, RiboBio, C10310-1, Guangzhou, China), fixed (4% PFA, 30 min), and permeabilized (0.5% Triton X-100, 10 min). Click chemistry staining was performed in the dark for 30 min using Apollo solution, followed by DAPI (Beyotime, C1006) nuclear staining (5 min). Proliferating cells were quantified via fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, CKX53, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell cycle progression was assessed through PI-based flow cytometric analysis. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well and subsequently divided into experimental groups according to the methodology described in Section 2.4. Following collection, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol (−20°C, 4 h), washed with chilled PBS, and stained with PI/RNase solution (C1052, Beyotime) for 30 min at 37°C in darkness. Samples were then analyzed on the specified flow cytometer (FACSCanto™ II, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), with PI fluorescence emission data processed through Flow Jo software (v 10.8.1, BD Biosciences) to determine phase distribution (G0/G1, S, G2/M).

Apoptotic cell populations were quantified using the specified Annexin V-FITC/PI staining kit (HY-K1073, MCE). Following standard collection procedures, cells were simultaneously labeled with Annexin V-FITC and PI as per the manufacturer’s protocol, with gentle mixing followed by 20 min dark incubation at ambient temperature. Prior to flow cytometric analysis, the reaction was terminated by adding binding buffer to stabilize fluorescence signals. The apoptosis rate was quantified using Flow Jo software (v 10.8.1).

2.7 Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Assay

ALP enzymatic activity was assessed to monitor osteogenic differentiation using a commercial assay kit (P0321M, Beyotime). MC3T3-E1 cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in 6-well plates and treated as specified. Following PBS washing, cells were lysed on ice with 100 μL lysis buffer (P0013J, Beyotime) using ultrasonic disruption (Qixun Instruments Co., Ltd., ST-250D, Shanghai, China). After centrifugation (9000× g, 4°C, 15 min), supernatants were analyzed for protein content via BCA assay (P0012, Beyotime). Equal protein aliquots were reacted with substrate (37°C, 10 min), and absorbance at 405 nm was measured via a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy H1) for ALP activity determination relative to a standard curve.

Following medium removal and PBS washing, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (30 min) prior to enzymatic staining. The BCIP/NBT ALP detection kit (Beyotime, C3206) was employed according to manufacturer specifications. After applying the working solution, samples were protected from light during 3 h incubation at ambient temperature. The reaction was stopped by distilled water washing. Stained cells were visualized under bright-field microscopy (Olympus, CKX 53), with quantitative analysis performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53c, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Relative ALP activity was normalized to the control group (set as 1) for comparative analysis.

2.9 Alizarin Red S (ARS) Staining

Following the 21-day differentiation induction, cultures were PBS-washed and fixed with 95% ethanol (30 min). After removal of fixative, cells were completely covered with ARS solution (Beyotime, C0148S) for 30 min staining at room temperature. Excess dye was removed by distilled water rinsing prior to microscopic imaging and quantitative analysis using ImageJ software (version 1.53c, NIH).

2.10 Osteocalcin (OCN) Detection

Post-treatment cell lysates were prepared by ultrasonic disruption followed by centrifugation (8000× g, 4°C, 10 min). Supernatants were analyzed for osteocalcin content using a commercial ELISA system (Solarbio, SEKM-0301) per manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance readings at 450 nm were converted to concentration values via standard curve interpolation.

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. After cell attachment, specific treatments were applied. A scratch was created using a pipette tip with consistent pressure and force. Cells were gently washed with PBS to remove detached cells, and the medium was replaced with serum-free culture medium (Gibco, 31985062). Cell migration was observed and photographed under a microscope (Nikon, Eclipse Ti-S, Tokyo, Japan) at 0 h and 24 h. Quantitative analysis and calculation of cell migration rates were performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53c, NIH).

Following experimental treatments, cellular samples underwent fixation with 4% PFA, membrane permeabilization using 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocking with 5% BSA (Gibco, 30066575). Primary antibody incubation was performed with anti-β-catenin (1:200, #8480, CST, Danvers, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Subsequent detection employed Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500, ab150077, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) with 1 h (room temperature, RT) incubation in darkness. Nuclear counterstaining with DAPI preceded confocal microscopic examination (Nikon, A1R HD) for assessment of β-catenin subcellular localization and quantitative fluorescence intensity analysis across experimental groups.

Total cellular proteins were isolated from MC3T3-E1 cells using RIPA buffer (R0010, Solarbio). Protein concentrations were measured with the BCA assay (PC0040, Solarbio), and equal protein quantities were resolved through SDS-PAGE before electrophoretic transfer to PVDF membranes. Following membrane blocking with 5% non-fat milk (1 h, RT), primary antibody incubations were performed at 4°C overnight targeting: PCNA (1:1000, #13110, CST), Ki67 (5 μg/mL, ab16667, Abcam), Cyclin D1 (1:1000, #2978, CST), c-myc (1:800, #13987, CST), RUNX2 (1:1000, ab192256, Abcam), OCN (1:800, bs-4917R, Bioss, Beijing, China), OPN (1:1000, ab218237, Abcam), OSX (1:800, bs-1110R, Bioss), BMP-2 (1:1000, ab284387, Abcam), Collagen I (1:500, bs-10423R, Bioss), Wnt-3a (1:1000, PA5-37320, Invitrogen), β-catenin (1:1000, #9562, CST), p-GSK-3β (1:1000, #5558, CST), GSK-3β (1:1000, #9315, CST), and β-actin (1:10,000, bsm-63325R, Bioss). After TBST washes, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000, #7074, CST) were applied (1 h, RT). Signal detection employed ECL substrate (P0018, Beyotime), with β-actin as loading control and ImageJ-based band quantification (version 1.53c, NIH).

Quantitative data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA (Tukey’s post-test) in GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), where p-values < 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

3.1 LA Promotes Osteoblast Proliferation

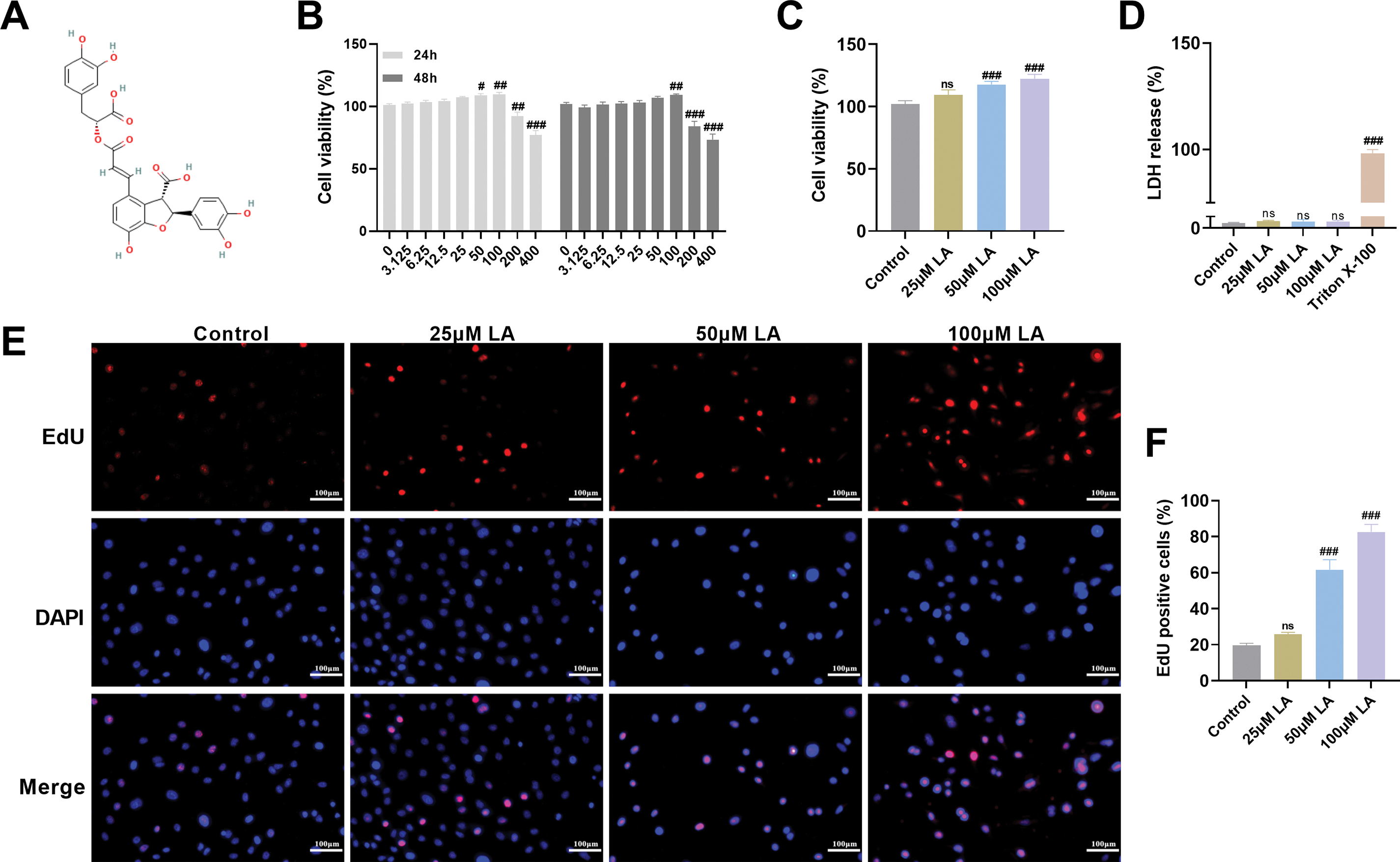

This study systematically evaluated the effect of LA (structural formula shown in Fig. 1A) on osteoblast proliferation. First, the effects of LA on osteoblast viability at different concentrations and treatment durations were evaluated using the MTT assay. The data showed a positive correlation between LA concentration (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μM) and osteoblast viability, with this proliferative effect being maintained throughout the 24 h/48 h observation period. However, at concentrations of 200 and 400 μM, LA significantly inhibited cell viability (Fig. 1B,C). To complement viability studies, LDH release was quantified as an indicator of membrane integrity. This stable cytosolic enzyme remains intracellular in viable cells but is extruded following membrane compromise during apoptosis or necrosis [27,28]. The results showed that treatment with 25, 50, and 100 μM of LA did not significantly increase LDH release (Fig. 1D), indicating that these concentrations do not compromise cell membrane integrity and possess good biocompatibility. Therefore, subsequent experiments selected 25, 50, and 100 μM as the concentrations of LA.

Figure 1: Lithospermic acid (LA) Promotes Osteoblast Proliferation. (A) The chemical structure of LA. Molecular structures were drawn using KingDraw Professional for Windows (version 5.0, Qingdao KingOrigin Agrotech Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). (B,C) The effect of different concentrations (0, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μM) of LA on osteoblast proliferation activity after 24 and 48 h, assessed by the MTT assay. (D) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity screening revealed concentration-dependent effects of LA (25, 50, 100 μM), establishing 25, 50, and 100 μM as the optimal non-toxic range for subsequent experiments. (E,F) EdU incorporation assays visualized proliferating cells (red fluorescence) against nuclear staining (blue), quantitatively demonstrating LA’s pro-proliferative effects. Scale bar 100 μm. n = 3. ns: p > 0.05; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. Control

EdU, a thymidine analog, is widely used for detecting cell proliferation [29]. EdU incorporation assays revealed a significant, concentration-dependent elevation in proliferating cell populations across LA-treated groups compared to controls (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 1E,F), demonstrating LA’s potent mitogenic effects on osteoblasts. In summary, this study confirmed that within an appropriate concentration range, LA not only safely and effectively promotes osteoblast proliferation but also does not induce significant cytotoxicity, highlighting its potential application as a therapeutic agent for bone regeneration. These findings lay a foundation for further investigation into its molecular mechanisms.

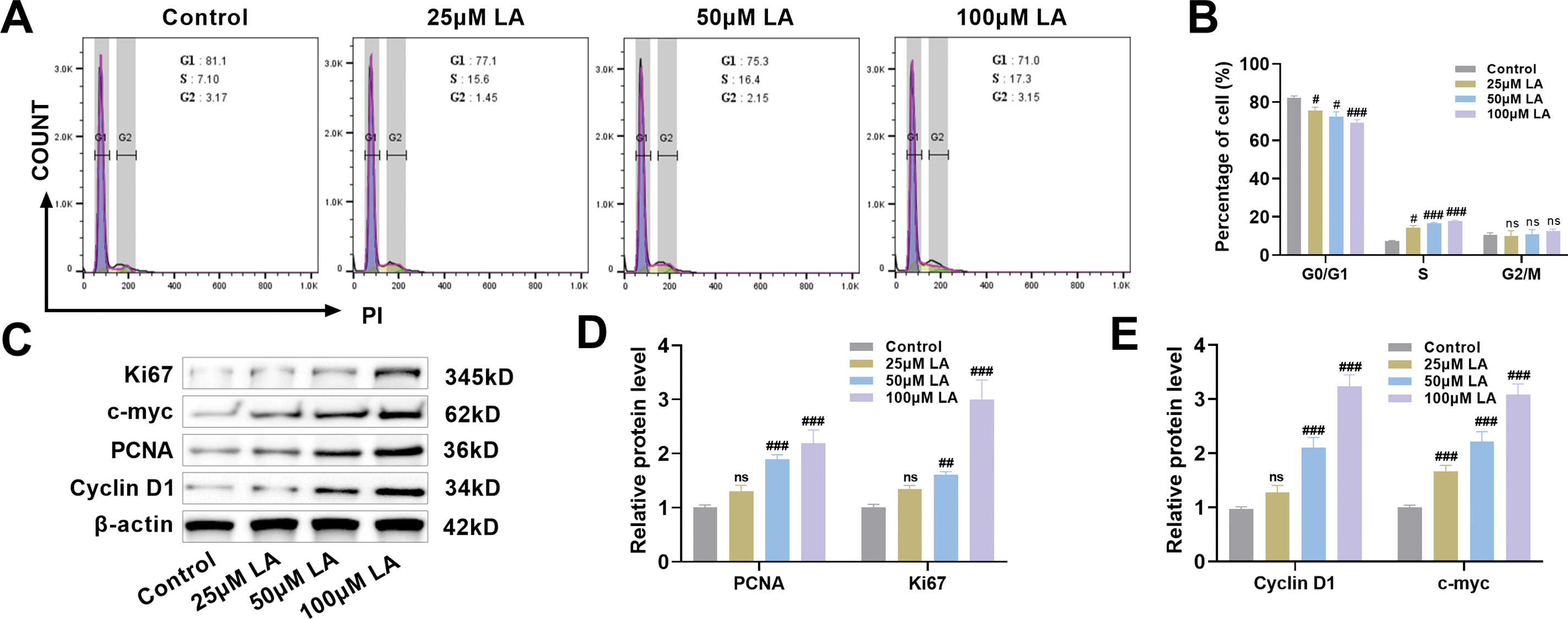

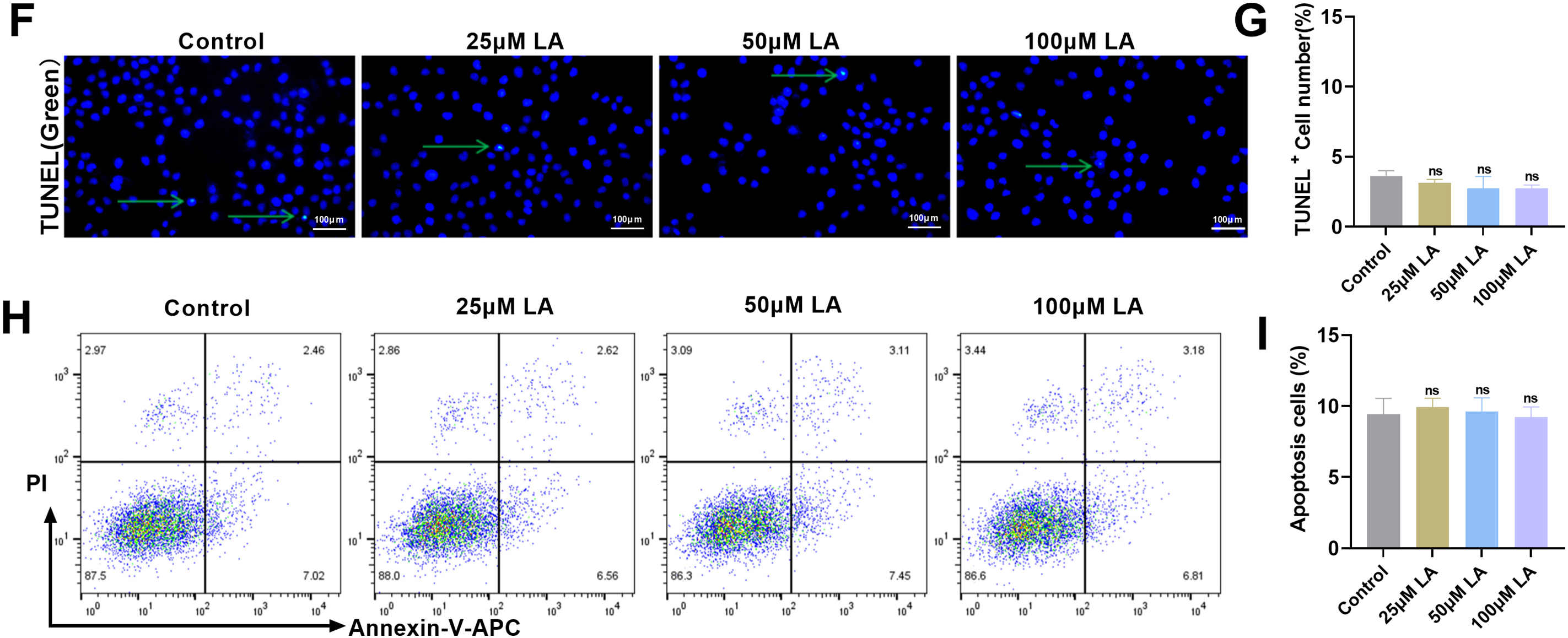

3.2 LA Promotes Cell Cycle Progression but Does Not Affect Osteoblast Apoptosis

Flow cytometric evaluation of MC3T3-E1 cell cycle progression (Fig. 2A,B) was conducted to elucidate the mechanistic basis of LA-mediated proliferation enhancement. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that 50 μM LA treatment significantly decreased the G0/G1 population while increasing S phase proportions compared to controls. This effect was more pronounced at 100 μM LA, demonstrating concentration-dependent cell cycle acceleration through G0/G1 arrest reduction and G2/M progression enhancement (Fig. 2A,B). Western blot analysis confirmed LA’s proliferative mechanism through dose-dependent upregulation of key cell cycle regulators (PCNA, Ki67, Cyclin D1, c-myc) (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 2C–E). These proteins, essential for cell cycle progression, showed significantly enhanced expression in LA-treated osteoblasts compared to controls.

Figure 2: LA promotes cell cycle progression but does not affect osteoblast apoptosis. (A,B) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle progression in osteoblasts following treatment with LA (25, 50, 100 μM), quantifying phase distribution (G0/G1, S, G2/M). (C–E) Western blot detection of cell cycle regulators expression patterns: Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA), Kiel-67 (Ki67), Cyclin D1, cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-myc). (F,G) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay for apoptotic cell quantification across LA concentrations. Green arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bar 100 μm. (H,I) Flow cytometric assessment of LA-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts. n = 3. ns: p > 0.05; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. control

To assess potential cytotoxic effects, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining and flow cytometric analysis were performed. Results demonstrated comparable apoptosis rates between LA-treated and control groups across all tested concentrations (Fig. 2F–I), confirming LA’s proliferative effects are not accompanied by increased programmed cell death. LA exerts pro-proliferative effects on osteoblasts through coordinated regulation of cell cycle dynamics, specifically by attenuating G0/G1 phase arrest while enhancing progression through the G2/M phase checkpoint. This proliferative activity is further supported by the compound’s ability to upregulate critical cell cycle regulatory proteins, all while maintaining physiological apoptosis levels, thereby demonstrating its selective mitogenic properties.

3.3 LA Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation, Mineralization, and Migration

Osteogenic differentiation represents an essential biological process during skeletal tissue formation and mineralization [30]. ALP activity serves as a marker of early osteogenic differentiation; the more mature the osteoblast differentiation, the higher the ALP expression activity [31]. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of ALP, a key early osteogenic marker, showed significant increases in enzymatic activity and staining intensity across LA-treated groups (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 3A–C), confirming its ability to enhance osteoblast differentiation. OCN serves as a biochemical indicator of osteoblast maturation, reflecting both the degree of bone matrix formation and cellular differentiation status [32]. LA treatment markedly upregulated OCN expression in a concentration-dependent manner (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 3D), indicating its efficacy in promoting late-stage osteoblast maturation and bone formation. Following a 21-day differentiation period, quantitative ARS staining demonstrated significantly elevated calcium deposition in LA-treated cultures (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 3E,F), verifying its capacity to stimulate extracellular matrix mineralization. Scratch assay results demonstrated progressive enhancement of osteoblast migration rates corresponding to increasing LA concentrations (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 3G,H).

Figure 3: LA promotes osteoblast differentiation, mineralization, and migration. (A–C) ALP activity was measured using a kit and ALP staining was performed to evaluate the effect of LA on osteoblast differentiation. Scale bar 100 μm. (D) Osteocalcin (OCN) concentration was determined by Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to analyze the regulatory role of LA in osteoblast differentiation. (E,F) After 21 days of culture in osteogenic induction medium, Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining was conducted to observe mineralized nodule formation. Scale bar 100 μm. (G,H) Cell scratch assays were used to assess the effect of LA on osteoblast migration capacity. Scale bar 200 μm. (I–K) Western blot analysis was performed to detect the expression levels of osteogenic differentiation-related proteins, including Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2), Collagen I, Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), OCN, Osteopontin (OPN) and Osterix (OSX). n = 3. ns: p > 0.05; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. control

RUNX2 and OSX (SP7) are key transcription factors involved in bone formation, jointly regulating osteoblast proliferation and differentiation [33]. OPN participates in osteoblast adhesion and migration, while OCN promotes osteoblast maturation and mineralization of the bone matrix [34]. These proteins are markers of mid- and late-stage osteogenesis, respectively. As a pivotal growth factor in skeletal development, BMP2 stimulates osteoblast proliferation and bone matrix synthesis through coordinated upregulation of key extracellular components (osteopontin, collagen, proteoglycans) while simultaneously activating ALP [35]. Collagen I, the main matrix protein secreted by osteoblasts, not only provides a scaffold in bone regeneration but also facilitates osteoblast adhesion, migration, and proliferation, while regulating differentiation and activating mineralization-related enzymes, thereby promoting mineralization of the bone matrix [36,37]. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that LA treatment markedly increased expression levels of critical osteogenic regulators (RUNX2, OSX) and functional markers (OCN, OPN, BMP-2, Collagen I) (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 3I–K). These findings collectively demonstrate that LA stimulates osteoblast differentiation and function through multiple mechanisms: activation of the RUNX2/OSX transcriptional axis, potentiation of BMP-2 signaling, promotion of bone matrix protein synthesis, and augmentation of cellular migratory potential.

3.4 LA Activates Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway to Promote Osteoblast Proliferation

Quantitative fluorescence imaging revealed that LA administration stimulated dose-responsive accumulation of β-catenin in the nuclear compartment while simultaneously elevating its cellular expression (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 4A,B). As a critical modulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, GSK-3β exerts regulatory control over β-catenin degradation through its phosphorylation state, thereby influencing fundamental cellular processes including osteogenesis, proliferation, and oncogenesis [38,39]. Immunoblotting results demonstrated that LA administration significantly enhanced Wnt-3a and β-catenin protein levels while elevating GSK-3β phosphorylation (p100μM LA < 0.001, Fig. 4C,D). Collectively, these biochemical changes demonstrate LA-mediated activation of Wnt signaling, implicating this pathway as a key mechanism underlying its dual effects on cellular proliferation and differentiation.

Figure 4: LA activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote osteoblast proliferation. (A,B) Immunofluorescence was used to detect the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. Scale bar 100 μm. (C,D) Western blot analysis was performed to assess the expression of key proteins in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, including Wnt-3a, β-catenin, p-GSK-3β, and GSK-3β. n = 3. ns: p > 0.05, #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 vs. control. (E,F) To further investigate the role of LA through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, the Wnt pathway inhibitor DKK-1 was used for intervention. The experimental groups included: control, 100 μM LA, DKK-1, and 100 μM LA + DKK-1 combined group. Changes in the expression of proteins related to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway were analyzed to elucidate the mechanism of LA’s action within this pathway. (G,H) EdU staining was used to detect cell proliferation activity. Red arrows indicate EdU-positive cells. Scale bar 100 μm. (I,J) TUNEL staining was employed to assess cell apoptosis. Green arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bar 100 μm. (K,L) Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry. n = 3. ns: p > 0.05; #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 vs. Control; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01, &&&p < 0.001 vs. 100 μM LA

The critical involvement of Wnt signaling was validated through DKK-1 blockade experiments. Western blot data demonstrated that LA-induced upregulation of Wnt, β-catenin, and phosphorylated GSK-3β was completely attenuated by concurrent DKK-1 treatment, providing definitive evidence that LA’s mechanism of action depends on Wnt pathway stimulation. Furthermore, DKK-1 could reverse LA-induced β-catenin accumulation and GSK-3β phosphorylation (Fig. 4E,F), further supporting that LA functions via the classical Wnt pathway. The results of EdU staining showed that LA significantly promoted the proliferation of osteoblasts, whereas DDK-1 inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. 4G,H). TUNEL staining indicated that LA had no significant effect on cell apoptosis, but the addition of DDK-1 markedly increased the apoptosis rate (Fig. 4G–J). Furthermore, compared with the LA group, the combination of LA and DDK-1 inhibited osteoblast proliferation and promoted cell apoptosis. Cell cycle profiling via flow cytometry demonstrated that LA treatment significantly decreased G0/G1 phase occupancy while concurrently elevating S phase populations (Fig. 4K,L), consistent with enhanced proliferative activity. Conversely, DKK-1 inhibited cell proliferation, and when used in combination, DKK-1 could reverse the proliferative effect of LA on osteoblasts. LA activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which in turn promotes osteoblast growth. This mechanism highlights LA’s potential role in bone regeneration therapy.

3.5 LA Activates the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway to Promote Osteoblast Differentiation and Migration

The molecular mechanisms underlying LA-mediated regulation of osteoblast differentiation and migration were further examined, with a focus on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Enhanced ALP activity was observed upon treatment with 100 μM LA (p < 0.001), whereas DKK-1 exposure led to significant inhibition (Fig. 5A–C). Assessment of OCN levels and ARS staining revealed a pronounced increase in both differentiation potential and mineralization capability in LA-treated cells relative to controls (p < 0.001), while DKK-1 administration significantly attenuated these osteogenic properties (Fig. 5D–F). Scratch assays demonstrated that LA markedly promoted osteoblast migration, whereas DKK-1 significantly inhibited migratory capacity (Fig. 5G,H). A significant suppression of ALP activity, mineralization capacity, and migration ability was observed in the LA+DKK-1 group when compared to LA treatment alone, further substantiating the crucial role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mediating LA’s osteogenic effects.

Figure 5: LA activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote osteoblast differentiation and migration. (A–C) ALP activity detection and staining were used to evaluate osteogenic differentiation capacity. Scale bar 100 μm. (D) OCN secretion levels were measured by ELISA. (E,F) After 21 days of osteogenic induction culture, ARS staining was performed to observe mineralized nodule formation. Scale bar 100 μm. (G,H) Cell scratch assays were employed to assess cell migration ability. Scale bar 200 μm. (I–N) Western blot analysis was conducted to detect the expression levels of osteogenic differentiation marker proteins, including Collagen I, OPN, RUNX2, OSX, OCN, and BMP2. n = 3. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. Control; &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01, &&&p < 0.001 vs. 100 μM LA

LA was shown to markedly elevate expression of osteogenic transcription factors (RUNX2, OSX) and differentiation markers (OCN, OPN, BMP2, Collagen I) in Western blot assays. Conversely, DKK-1 suppressed the expression of these proteins and reversed the upregulation induced by LA (Fig. 5I–N). The experimental data demonstrate that LA facilitates osteogenic processes, including cellular differentiation, mineral deposition, and migratory capacity through coordinated activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, subsequent induction of RUNX2/OSX transcription factors, and concomitant stimulation of BMP2 production along with extracellular matrix biosynthesis.

3.6 β-Catenin as a Downstream Wnt Signaling Molecule Influencing Osteoblast Proliferation, Differentiation, and Migration

To determine β-catenin’s critical role in LA-induced bone formation, β-catenin-deficient osteoblast models were generated. Protein analysis confirmed efficient gene knockdown, showing substantial β-catenin reduction in siRNA-treated cells (p < 0.001, Fig. 6A,B). At the molecular level, LA treatment activated the Wnt pathway through coordinated upregulation of Wnt-3a and β-catenin expression coupled with GSK-3β phosphorylation. While the LA+si-NC control group exhibited no notable changes, these regulatory effects were significantly diminished in β-catenin-deficient cells (Fig. 6C,D), providing additional evidence for β-catenin’s crucial role as a downstream mediator in Wnt signaling transduction.

Figure 6: β-catenin as a downstream Wnt signaling molecule influencing osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and migration. (A,B) Construction of β-catenin knockdown cell lines (si-β-catenin), with Western blot verification of β-catenin knockout efficiency (si-NC serving as negative control). n = 3. ###p < 0.001 vs. si-NC. (C,D) Western blot analysis of the expression changes of key proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway (Wnt-3a, β-catenin, p-GSK-3β, GSK-3β) across different treatment groups (Control, 100 μM LA, 100 μM LA + si-NC, 100 μM LA + si-β-catenin). (E,F) Western blot analysis of the expression levels of cell proliferation-related proteins (PCNA, Ki67, Cyclin D1, c-myc). (G–I) Western blot detection of osteogenic differentiation markers (RUNX2, OCN, OPN, OSX, BMP2, Collagen I). n = 3. ###p < 0.001 vs. Control, &&&p < 0.001 vs. 100 μM LA+ si-β-catenin

Regarding proliferation, the LA-induced upregulation of proliferation-related proteins PCNA, Ki67, Cyclin D1, and c-Myc was significantly suppressed in β-catenin knockdown cells (p < 0.001, Fig. 6E,F), indicating that β-catenin mediates LA’s proliferative effects. Comprehensive evaluation of osteogenic markers revealed that LA-mediated upregulation of critical transcription factors (RUNX2, OSX, BMP2) and differentiation markers (OCN, OPN, Collagen I) was β-catenin-dependent (Fig. 6G–I). Collectively, these findings establish β-catenin as a crucial Wnt pathway effector that is essential for mediating LA-induced osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and extracellular matrix production. This finding not only clarifies the signal transduction mechanism underlying LA’s osteogenic effects but also provides an important theoretical basis for targeted β-catenin-based bone regeneration therapies.

Bone regeneration is a vital physiological process for repairing bone defects and injuries in the human body, with extensive clinical application value [40]. With the increasing prevalence of orthopedic diseases and the growing demand for bone grafts, research into the mechanisms of bone regeneration has become a focal point in both academia and clinical medicine [41]. Osteoblast-mediated bone formation encompasses multiple coordinated processes (proliferation, differentiation, mineralization) that are tightly regulated at molecular level through diverse signaling mechanisms [42,43]. Comprehensive understanding of bone regeneration pathways facilitates the discovery of pivotal osteoblast modulators, offering both theoretical support for precision medicine in bone repair and technological innovations for regenerative applications. These advancements promise to elevate therapeutic efficacy while reducing morbidity and treatment burdens, highlighting the dualsignificance of basic research exploration and clinical implementation.

The proliferation of osteoblasts is a critical step in bone formation, directly affecting the capacity for bone tissue repair and reconstruction. This study found that LA treatment significantly promoted osteoblast proliferation activity. These findings align with previous work by Guan et al. [44], which reported that aqueous extracts from Eucommia ulmoides leaves enhance proliferation in MC3T3-E1 preosteoblastic cells. Cell proliferation is precisely regulated through the cell cycle, comprising distinct phases (G0/G1, S, G2, and M), each governed by stringent molecular controls [45,46]. The progression of the cell cycle is primarily controlled by cyclins and their associated cyclin-dependent kinases, which function through the formation of active complexes that catalyze the phosphorylation of specific substrate proteins, consequently facilitating transition between cell cycle phases. For example, Cyclin D1 binds to CDK4/6 to promote the transition from G1 to S phase [47]. As established proliferation markers, PCNA and Ki67 are commonly employed in cell cycle studies. PCNA functions as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase during replication, and its expression levels directly reflect cellular proliferative capacity [48]. Ki67 is a nuclear protein expressed in G1, S, G2, and M phases but absent in G0, making it a reliable indicator of cell proliferation [49,50]. The multifunctional transcription factor encoded by the c-myc proto-oncogene plays central roles in governing cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. High levels of c-myc expression are characteristically associated with heightened proliferative states [51,52]. In this study, flow cytometry was used to analyze the effect of LA on the cell cycle distribution of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. The results showed that LA treatment significantly reduced the proportion of cells in the G0/G1 phase while increasing the proportion of cells in the S phase. These findings indicate that LA can effectively promote the transition of cells from the quiescent phase (G0) or G1 phase to the active DNA synthesis phase (S phase), thereby accelerating cell cycle progression and ultimately enhancing cell proliferation. The concentration-dependent effects further corroborate LA’s regulatory capacity in cell cycle modulation. To molecularly corroborate these observations, we conducted Western blot analysis of key proliferation markers and cell cycle regulators. Quantitative protein analysis revealed dose-dependent elevations in PCNA, Ki67, Cyclin D1, and c-myc expression in LA-exposed osteoblasts. Particularly, the upregulated expression of PCNA (a DNA replication cofactor) and Ki67 (a cell cycle progression marker) provides direct molecular evidence for LA’s pro-proliferative effects on osteoblasts. The upregulation of Cyclin D1 indicates that LA facilitates the G1 to S phase transition, consistent with the observed reduction in G0/G1 phase cells from flow cytometry. As an important regulator of cell proliferation, increased c-myc expression further supports LA’s role in promoting osteoblast proliferation. These molecular evidence and cell cycle analysis results complement each other, collectively revealing that LA promotes osteoblast proliferation by accelerating cell cycle progression.

The progression of osteogenic differentiation involves sequential phases, each governed by the synergistic interaction of key transcription factors and signaling pathways. Runx2 is the primary transcription factor governing osteogenic differentiation; its expression level directly determines the extent of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into osteoblasts [53]. The elevated Runx2 expression observed in osteoblasts likely stems from LA-mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade. Concurrently, the increased ALP activity, serving as a characteristic early-phase osteogenic marker, indicates functional activation of osteoblast differentiation processes. OCN, a marker of late-stage osteogenic differentiation, indicates that osteoblasts have entered a mature stage when its expression is upregulated [54]. The concomitant elevation of these stage-specific markers demonstrates LA’s ability to regulate the full osteogenic differentiation cascade, spanning from progenitor cell determination to functional osteoblast development. Experimental results reveal that LA administration markedly enhances expression of critical osteogenic markers (Runx2, ALP, and OCN), demonstrating its strong potential to stimulate osteoblast differentiation.

Recent studies demonstrate that natural compounds (quercetin, icariin) promote osteogenesis through coordinated activation of Wnt/β-catenin, BMP-2/Smad5, and ERK/MAPK signaling, enhancing BMSC proliferation and differentiation [55,56]. The canonical Wnt pathway, fundamental to skeletal biology, regulates β-catenin stability through a destruction complex (GSK-3β/APC/Axin) that targets it for ubiquitination [57]. Wnt ligand binding to Frizzled/LRP5/6 receptors disrupts this complex, enabling β-catenin nuclear translocation and TCF/LEF-mediated transcription [58]. This study elucidates that LA exerts its pro-osteogenic effects principally via Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. Molecular analyses demonstrated LA-induced upregulation of Wnt-3a and β-catenin expression, enhanced β-catenin nuclear accumulation, and increased GSK-3β phosphorylation in osteoblasts. Importantly, both pharmacological Wnt inhibition and genetic β-catenin ablation substantially attenuated osteogenic processes, confirming the pathway’s essential role in bone regeneration. These findings underscore the fundamental contribution of Wnt/β-catenin signaling to skeletal development, homeostasis, and pathology. This pathway not only regulates osteoblast proliferation and differentiation but also participates in various essential physiological processes. Excessive activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling can induce pathological chondrocyte hypertrophy and accelerate osteoarthritis development [59]. Therefore, precise regulation of its activity presents a significant challenge for future drug development. LA regulates Wnt/β-catenin axis proteins in a dose-dependent manner (25, 50, 100 μM), reflecting its natural pharmacodynamic profile. Compared to other activators, LA demonstrates a milder and more controllable regulatory profile, which may reduce potential adverse reactions.

In the fields of bone regeneration and osteoporosis treatment, various drugs and natural compounds have been confirmed to possess osteogenic activity. Comparing the mechanisms and effects of LA with these known compounds can facilitate a better understanding of its potential clinical applications. The oral bioavailability of icariin and its derivatives is also notably low (approximately 12%) and accompanied by poor absorption, which consequently restricts their clinical application [60]. Similarly, quercetin exhibits limitations in aqueous solubility, chemical stability, and absorption characteristics, typically resulting in a relatively low bioavailability (<10%) [61]. Contemporary osteoporosis management primarily employs two pharmacological approaches: anti-resorptive drugs (e.g., bisphosphonates) and bone-forming agents (e.g., parathyroid hormone analogues). Nevertheless, these therapeutic options are frequently associated with adverse effects or clinical application constraints [62]. Semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, has recently been demonstrated to enhance the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. However, its administration may induce adverse effects, including hypoglycemia, nausea, vomiting, and pancreatitis [63,64]. Given its natural origin, LA combines low toxicity with potent bone-forming capabilities, highlighting its therapeutic promise. Future applications may include bone repair strategies and engineered constructs for skeletal regeneration. Research by Zhang et al. has demonstrated the application of LA in nanocarrier systems, combining LA with ZIF-8 nanoparticles to achieve effective treatment of osteoarthritis [65]. This study provides an important reference for the application of LA in bone regeneration materials. Notably, LA’s unique advantages in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties confer it with special value in bone regeneration applications [66,67]. Many patients with bone defects and osteoporosis often suffer from chronic inflammatory states [68,69]. The multifunctional nature of LA enables simultaneous anti-inflammatory action and pro-osteogenic activity, a therapeutic profile that outperforms many monofunctional pharmacological agents and positions it as a highly promising candidate for bone repair applications.

This study demonstrates that LA promotes osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, mineralization, and migration in vitro, mediated through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Although MC3T3-E1 cells are a commonly used in vitro model in osteogenesis research, they cannot fully replicate the complex in vivo physiological environment. Future studies should incorporate more physiologically relevant cell models, such as primary osteoblasts or human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), and perform in vivo animal experiments to more comprehensively evaluate the osteogenic potential of LA. The pathogenesis of osteoporosis involves an imbalance between bone formation and resorption. Thus, the lack of assessment regarding LA’s potential inhibitory effects on osteoclast activity limits a holistic understanding of its capacity to achieve “net bone gain”. Future investigations should include evaluations of bone resorption. Furthermore, this study does not provide a comprehensive exploration of the molecular regulatory network of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Although LA-induced activation of the pathway was confirmed, detailed mechanisms upstream-such as Wnt ligand-receptor interactions—were not thoroughly investigated. Deeper mechanistic studies would help clarify how LA initiates Wnt signaling. Moreover, the reliance on DKK-1 as the only inhibitor for pathway validation is insufficient. Future work should employ additional specific inhibitors targeting different nodes of the pathway or utilize genetic editing techniques to more precisely and comprehensively verify LA’s regulatory mechanism, thereby providing a stronger foundation for developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

This investigation represents the first systematic demonstration of LA’s pro-osteogenic effects mediated via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. These findings significantly advance our understanding of LA’s pharmacological properties while offering important mechanistic insights for developing novel bone therapeutic strategies. Future research should further verify its in vivo effects, elucidate detailed molecular mechanisms, and evaluate its feasibility for clinical translation.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan Project (2023ZL128) and Zhejiang Province Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (2022504276) and Hangzhou Municipal Health and Family Planning Science and Technology Program General Project (A20210086).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Jianfeng Wang, Zhongqing Hu; Data collection: Jiandong Guo, Xin Jin; Analysis and interpretation of results: Lei Cai, Jian Li; Draft manuscript preparation: Jinxi Zhang, Dongan He. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (Jinxi Zhang, Dongan He) upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full Name |

| LA | Lithospermic acid |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| Smad | Sma- and mad-related proteins |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ARS | Alizarin red S |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| RUNX2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| OSX | Osterix |

| hMSCs | Human mesenchymal stem cells |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| ELISA | Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

| Ki67 | Kiel-67 |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| DKK-1 | Dickkopf-1 |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

References

1. Wawrzyniak A, Balawender K. Structural and metabolic changes in bone. Animals. 2022;12(15):1946. doi:10.3390/ani12151946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Srivastava RK, Sapra L, Mishra PK. Osteometabolism: metabolic alterations in bone pathologies. Cells. 2022;11(23):3943. doi:10.3390/cells11233943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cooney OD, Nagareddy PR, Murphy AJ, Lee MKS. Healthy gut, healthy bones: targeting the gut microbiome to promote bone health. Front Endocrinol. 2021;11:620466. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.620466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Chen S, Chen X, Geng Z, Su J. The horizon of bone organoid: a perspective on construction and application. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:15–25. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.01.048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Duda GN, Geissler S, Checa S, Tsitsilonis S, Petersen A, Schmidt-Bleek K. The decisive early phase of bone regeneration. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023;19(2):78–95. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00887-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hong MH, Lee JH, Jung HS, Shin H, Shin H. Biomineralization of bone tissue: calcium phosphate-based inorganics in collagen fibrillar organic matrices. Biomater Res. 2022;26(1):42. doi:10.1186/s40824-022-00288-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xue N, Ding X, Huang R, Jiang R, Huang H, Pan X, et al. Bone tissue engineering in the treatment of bone defects. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(7):879. doi:10.3390/ph15070879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Patel D, Wairkar S. Bone regeneration in osteoporosis: opportunities and challenges. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13(2):419–32. doi:10.1007/s13346-022-01222-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Singh S, Sarma DK, Verma V, Nagpal R, Kumar M. From cells to environment: exploring the interplay between factors shaping bone health and disease. Medicina. 2023;59(9):1546. doi:10.3390/medicina59091546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wu Z, Li W, Jiang K, Lin Z, Qian C, Wu M, et al. Regulation of bone homeostasis: signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. MedComm. 2024;5(8):e657. doi:10.1002/mco2.657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang L, Guan Q, Wang Z, Feng J, Zou J, Gao B. Consequences of aging on bone. Aging Dis. 2023;15(6):2417. doi:10.14336/ad.2023.1115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li J, Li L, Wu T, Shi K, Bei Z, Wang M, et al. An injectable thermosensitive hydrogel containing resveratrol and dexamethasone-loaded carbonated hydroxyapatite microspheres for the regeneration of osteoporotic bone defects. Small Methods. 2024;8(1):e2300843. doi:10.1002/smtd.202300843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Xu Y, Huang R, Shi W, Zhou R, Xie X, Wang M, et al. ROS-responsive hydrogel delivering METRNL enhances bone regeneration via dual stem cell homing and vasculogenesis activation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025;14(16):e2500060. doi:10.1002/adhm.202500060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Gao Y, Chen N, Fu Z, Zhang Q. Progress of Wnt signaling pathway in osteoporosis. Biomolecules. 2023;13(3):483. doi:10.3390/biom13030483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Arya PN, Saranya I, Selvamurugan N. Crosstalk between Wnt and bone morphogenetic protein signaling during osteogenic differentiation. World J Stem Cells. 2024;16(2):102–13. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v16.i2.102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Dilawar M, Yu X, Jin Y, Yang J, Lin S, Liao J, et al. Notch signaling pathway in osteogenesis, bone development, metabolism, and diseases. FASEB J. 2025;39(4):e70417. doi:10.1096/fj.202402545R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Tian Y, Liang X, Yin C, Huai Y, Zhao Y, et al. Bergamottin promotes osteoblast differentiation and bone formation via activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2022;13(5):2913–24. doi:10.1039/d1fo02755g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang DH, Shao J. Research progress of basing on Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the treatment of bone tissue diseases. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2025;31(6):555–65. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2024.0170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sukarawan W, Rattanawarawipa P, Yaemkleebbua K, Nowwarote N, Pavasant P, Limjeerajarus CN, et al. Wnt3a promotes odonto/osteogenic differentiation in vitro and tertiary dentin formation in a rat model. Int Endod J. 2023;56(4):514–29. doi:10.1111/iej.13888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jin Z, Da W, Zhao Y, Wang T, Xu H, Shu B, et al. Role of skeletal muscle satellite cells in the repair of osteoporotic fractures mediated by β-catenin. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(2):1403–17. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Krutsenko Y, Singhi AD, Monga SP. β-catenin activation in hepatocellular cancer: implications in biology and therapy. Cancers. 2021;13(8):1830. doi:10.3390/cancers13081830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Liang X, Jin Q, Yang X, Jiang W. Dickkopf-3 and β-catenin play opposite roles in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway during the abnormal subchondral bone formation of human knee osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Med. 2022;49(4):48. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2022.5103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yang W, Li J, Tian J, Liu X, Xie W, Wu X, et al. Pharmacological activity, phytochemistry, and organ protection of lithospermic acid. J Cell Physiol. 2025;240(1):e31460. doi:10.1002/jcp.31460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Semwal BC, Hussain A, Singh S. An overview on naturally occurring phytoconstituent: lithospermic acid. Nat Prod J. 2024;14(1):e270423216291. doi:10.2174/2210315513666230427153251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Luo S, Yang B, Xu H, Pan X, Chen X, Jue X, et al. Lithospermic acid improves liver fibrosis through Piezo1-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation. Phytomedicine. 2024;134:155974. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kaur H, Singh S, Kanagala SG, Gupta V, Patel MA, Jain R. Herbal medicine—a friend or a foe of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2024;22(2):101–5. doi:10.2174/0118715257251638230921045029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ntanzi N, Khan RB, Nxumalo MB, Kumalo HM. Mechanisms of H2pmen-induced cell death: necroptosis and apoptosis in MDA cells, necrosis in MCF7 cells. Heliyon. 2024;10(23):e40654. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Tarek H, Cho SS, Hossain MS, Yoo JC. Attenuation of oxidative damage via upregulating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway by protease SH21 with exerting anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties in vitro. Cells. 2023;12(17):2190. doi:10.3390/cells12172190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Troth EV, Kyle DE. EdU incorporation to assess cell proliferation and drug susceptibility in Naegleria fowleri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(7):e0001721. doi:10.1128/AAC.00017-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Šromová V, Sobola D, Kaspar P. A brief review of bone cell function and importance. Cells. 2023;12(21):2576. doi:10.3390/cells12212576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chan YH, Ho KN, Lee YC, Chou MJ, Lew WZ, Huang HM, et al. Melatonin enhances osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp mesenchymal stem cells by regulating MAPK pathways and promotes the efficiency of bone regeneration in calvarial bone defects. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):73. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02744-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Bayram C, Ozturk S, Karaosmanoglu B, Gultekinoglu M, Taskiran EZ, Ulubayram K, et al. Microfluidic fabrication of gelatin-nano hydroxyapatite scaffolds for enhanced control of pore size distribution and osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Macromol Biosci. 2024;24(12):e2400279. doi:10.1002/mabi.202400279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Komori T. Regulation of skeletal development and maintenance by Runx2 and Sp7. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):10102. doi:10.3390/ijms251810102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Yang M, Gao Z, Cheng S, Wang Z, Ei-Seedi H, Du M. Novel peptide derived from Gadus morhua stimulates osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization through Wnt/β-catenin and BMP signaling pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(17):9691–702. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c06700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhu L, Liu Y, Wang A, Zhu Z, Li Y, Zhu C, et al. Application of BMP in bone tissue engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:810880. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.810880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Hasegawa T, Hongo H, Yamamoto T, Abe M, Yoshino H, Haraguchi-Kitakamae M, et al. Matrix vesicle-mediated mineralization and osteocytic regulation of bone mineralization. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):9941. doi:10.3390/ijms23179941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhu YS, Mo TT, Jiang C, Zhang JN. Osteonectin bidirectionally regulates osteoblast mineralization. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):761. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-04250-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang X, Qu Z, Zhao S, Luo L, Yan L. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway: proteins’ roles in osteoporosis and cancer diseases and the regulatory effects of natural compounds on osteoporosis. Mol Med. 2024;30(1):193. doi:10.1186/s10020-024-00957-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. AlMuraikhi N, Binhamdan S, Alaskar H, Alotaibi A, Tareen S, Muthurangan M, et al. Inhibition of GSK-3β enhances osteoblast differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells through Wnt signalling overexpressing Runx2. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7164. doi:10.3390/ijms24087164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Laubach M, Suresh S, Herath B, Wille ML, Delbrück H, Alabdulrahman H, et al. Clinical translation of a patient-specific scaffold-guided bone regeneration concept in four cases with large long bone defects. J Orthop Translat. 2022;34:73–84. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2022.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liang W, Zhou C, Bai J, Zhang H, Jiang B, Wang J, et al. Current advancements in therapeutic approaches in orthopedic surgery: a review of recent trends. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1328997. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1328997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Yan CP, Wang XK, Jiang K, Yin C, Xiang C, Wang Y, et al. β-ecdysterone enhanced bone regeneration through the BMP-2/SMAD/RUNX2/osterix signaling pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:883228. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.883228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ballhause TM, Jiang S, Baranowsky A, Brandt S, Mertens PR, Frosch KH, et al. Relevance of Notch signaling for bone metabolism and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1325. doi:10.3390/ijms22031325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Guan M, Pan D, Zhang M, Leng X, Yao B. The aqueous extract of Eucommia leaves promotes proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:3641317. doi:10.1155/2021/3641317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sun Y, Liu Y, Ma X, Hu H. The influence of cell cycle regulation on chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):6923. doi:10.3390/ijms22136923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Fischer M, Schade AE, Branigan TB, Müller GA, DeCaprio JA. Coordinating gene expression during the cell cycle. Trends Biochem Sci. 2022;47(12):1009–22. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2022.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Chen S, Li L. Degradation strategy of cyclin D1 in cancer cells and the potential clinical application. Front Oncol. 2022;12:949688. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.949688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Porras-Gómez TJ, Moreno-Mendoza N. Identification of the proliferative activity of germline progenitor cells in the adult ovary of the bat Artibeus jamaicensis. Zygote. 2024;32(5):366–75. doi:10.1017/S0967199424000364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Uxa S, Castillo-Binder P, Kohler R, Stangner K, Müller GA, Engeland K. Ki-67 gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(12):3357–70. doi:10.1038/s41418-021-00823-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Li J, Wang AR, Chen XD, Pan H, Li SQ. Ki67 for evaluating the prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Lett. 2022;23(6):189. doi:10.3892/ol.2022.13309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Wang C, Zhang J, Yin J, Gan Y, Xu S, Gu Y, et al. Alternative approaches to target Myc for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):117. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00500-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Al-Khreisat MJ, Hussain FA, Abdelfattah AM, Almotiri A, Al-Sanabra OM, Johan MF. The role of NOTCH1, GATA3, and c-MYC in T cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Cancers. 2022;14(11):2799. doi:10.3390/cancers14112799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Liu DD, Zhang CY, Liu Y, Li J, Wang YX, Zheng SG. RUNX2 regulates osteoblast differentiation via the BMP4 signaling pathway. J Dent Res. 2022;101(10):1227–37. doi:10.1177/00220345221093518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Wan H-Y, Shin RLY, Chen JCH, Assunção M, Wang D, Nilsson SK, et al. Dextran sulfate-amplified extracellular matrix deposition promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2022;140:163–77. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2021.11.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Bian W, Xiao S, Yang L, Chen J, Deng S. Quercetin promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation through the H19/miR-625-5p axis to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(1):243. doi:10.1186/s12906-021-03418-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang XY, Li HN, Chen F, Chen YP, Chai Y, Liao JZ, et al. Icariin regulates miR-23a-3p-mediated osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via BMP-2/Smad5/Runx2 and WNT/β-catenin pathways in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(12):1405–15. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):3. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00762-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hu L, Chen W, Qian A, Li YP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone formation, homeostasis, and disease. Bone Res. 2024;12(1):39. doi:10.1038/s41413-024-00342-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. He Z, Liu M, Zhang Q, Tian Y, Wang L, Yan X, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is activated in the progress of mandibular condylar cartilage degeneration and subchondral bone loss induced by overloaded functional orthopedic force (OFOF). Heliyon. 2022;8(10):e10847. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Szabó R, Rácz CP, Dulf FV. Bioavailability improvement strategies for icariin and its derivates: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7519. doi:10.3390/ijms23147519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Kandemir K, Tomas M, McClements DJ, Capanoglu E. Recent advances on the improvement of quercetin bioavailability. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;119:192–200. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.11.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhang C, Song C. Combination therapy of PTH and antiresorptive drugs on osteoporosis: a review of treatment alternatives. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:607017. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.607017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Tian Y, Liu H, Bao X, Li Y. Semaglutide promotes the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells through activation of the Wnt/LRP5/β-catenin signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1539411. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1539411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Smits MM, Van Raalte DH. Safety of semaglutide. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:645563. [Google Scholar]

65. Zhang Y, Lou Q, Lian H, Yang R, Cui R, Wang L, et al. sLithospermic acid etched ZIF-8 nanoparticles delays osteoarthritis progression by inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways and rescuing mitochondrial damage. Mater Today Bio. 2025;31:101589. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhao Y, Tian X, Yan Y, Tian S, Liu D, Xu J. Lithospermic acid alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation in DSS-induced colitis through Nrf2. Eur J Pharmacol. 2025;995:177390. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2025.177390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Guo J, Li CG, Mai FY, Liang JR, Chen ZH, Luo J, et al. Lithospermic acid targeting heat shock protein 90 attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory response via NF-кB signalling pathway in BV2 microglial cells. Immunol Res. 2025;73(1):54. doi:10.1007/s12026-025-09600-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Saxena Y, Routh S, Mukhopadhaya A. Immunoporosis: role of innate immune cells in osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:687037. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.687037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Iantomasi T, Romagnoli C, Palmini G, Donati S, Falsetti I, Miglietta F, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoporosis: molecular mechanisms involved and the relationship with microRNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3772. doi:10.3390/ijms24043772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools