Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Therapeutic Potential of CAR γδ T Cells: From Cancer to Autoimmune Disease

School of Life Science, Handong Global University, Pohang, 37554, Gyeongbuk, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jea-Hyun Baek. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Role of γδ T Cells and iNKT Cells in Cancer: Unraveling Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 4 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073551

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

The paradigm of cancer treatment has been reshaped by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) αβ T cell therapy, yet its full potential remains constrained by fundamental limitations. While conventional CAR αβ T cells have achieved notable success in hematological malignancies, their broader application is hindered by the high cost and delays of autologous manufacturing, as well as the critical risk of graft-vs-host disease (GvHD). In addition, their efficacy against solid tumors is often compromised by the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). As a promising solution, γδ T cells are being developed as an alternative CAR platform. Their intrinsic ability to recognize transformed cells in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent manner minimizes the risk of GvHD and supports the creation of safe, effective allogeneic therapies. Building on this unique biology, the therapeutic efficacy of CAR γδ T cells is being enhanced through advanced engineering strategies. Key innovations include “armoring” technologies, such as cytokine secretion, checkpoint blockade, and metabolic rewiring, to overcome local immunosuppression and improve persistence, as well as the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to generate standardized products from a renewable and consistent source. This expanding technological toolbox is also enabling novel applications beyond oncology. For example, chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR) constructs built on γδ T cells integrate both classical and emerging insights into CAR γδ T cell therapy, highlighting innovations that are driving the field toward safer, more versatile, and longer-lasting treatments for cancer and autoimmunity. In light of these advancements, this review provides an overview of the current understanding of γδ T cell biology and highlights emerging engineering strategies that enhance the efficacy and durability of CAR γδ T cells across oncologic and autoimmune contexts.Keywords

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) αβ T cell therapy has established a new paradigm in oncology, achieving remarkable remission rates against B-cell malignancies by targeting the CD19 antigen [1]. This success is rooted in the ability to reprogram patient-derived autologous αβ T cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells with high specificity. Beyond oncology, CAR T cell therapy has recently shown promise in severe autoimmune diseases, where early clinical studies have reported sustained remissions in refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), including pediatric cases [2]. These findings highlight that CAR-mediated immune reset can extend beyond cancer eradication to restoring self-tolerance in autoimmunity.

Despite these transformative outcomes, the full therapeutic potential of CAR T cell therapy remains constrained by fundamental hurdles. Allogeneic therapies, which could address the complexities of patient-specific manufacturing, are severely limited by the risks of life-threatening graft-vs-host disease (GvHD) and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) [3]. Furthermore, extending success to solid tumors has been challenging, as T cell function is often suppressed by immunosuppressive mediators such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and inhibitory immune populations within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3].

An ideal CAR T cell platform must combine two key attributes: (1) minimal alloreactivity to ensure safety in allogeneic contexts, and (2) robust functionality within the immunosuppressive TME. γδ T cells have emerged as a compelling solution that naturally fulfills these criteria. A defining characteristic of γδ T cells is their ability to recognize stressed or transformed cells independently of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). This unique recognition system-driven by their γδ TCR and co-expression of natural killer cell (NK) receptors recognizing ligands like MHC class I chain-related protein A (MICA) and B (MICB), bypasses the primary mechanism underlying GvHD. This makes γδ T cells an attractive foundation for universal allogeneic therapies.

These therapies can be manufactured from allogeneic healthy donor cells, cryopreserved, and delivered as “off-the-shelf” products without HLA matching. This addresses critical logistical and safety barriers while enabling broader patient access. Beyond safety, γδ T cells also display functional plasticity that bridges innate and adaptive immunity. They exert direct cytotoxicity via cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [4], while also functioning as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) capable of cross-priming adaptive T cell response [5]. Their natural ability to traffic to peripheral tissues and recognize stressed cells provides a foundation that CARs can redirect toward antigen-specific tumor elimination.

Clinical translation, however, has faced challenges such as limited persistence, exhaustion, and strong immunosuppressive pressures within the TME [6,7]. To address these obstacles, advanced engineering strategies are being developed. These include selective enrichment of specific γδ T cell subsets, armoring cells with dominant-negative TGF-β receptor to resist suppression, and optimizing trafficking for deeper tumor infiltration [8–10]. Such approaches are producing more durable responses in preclinical models and broadening the applicability of CAR γδ T cells to both hematologic and solid tumors [11].

The utility of this platform extends beyond cancer. Autoimmune diseases, driven by persistent autoantibody-producing B cells and plasma cells, represent a new frontier for CAR T cell therapy. By repurposing CAR constructs to target antigens such as B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), pathogenic cells can be selectively eliminated. Importantly, γδ T cells contribute additional therapeutic dimensions beyond CAR-directed cytotoxicity. Their capacity for immunoregulation through secretion of cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and TGF-β, may restore immune homeostasis and dampen chronic inflammation [12]. For autoimmune diseases requiring long-term management, a universal allogeneic γδ T cell platform offers the advantage of standardized, repeatable dosing regimens. The combination of targeted depletion and intrinsic regulatory potential positions γδ T cells as an exceptionally promising platform for autoimmune therapy.

The convergence of fundamental γδ T cell biology with advanced cellular engineering is rapidly expanding the therapeutic landscape from oncology to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. This review will (1) define the biological attributes of γδ T cells that make them a versatile foundation for cellular immunotherapy; (2) critically evaluate preclinical and emerging clinical evidence for CAR γδ T cells across cancers, highlighting key engineering strategies; and (3) explore novel applications in autoimmunity, charting a roadmap for translation into safe, effective, and accessible therapies. Accordingly, the objective of this review is to synthesize current knowledge of γδ T cell biology and recent advances in CAR γδ T cell engineering, highlighting their potential applications in cancer and autoimmune diseases.

γδ T cells, first recognized as a distinct lineage in the mid-1980s, arise from the same thymic progenitors as conventional αβ T cells but are defined by their unique T cell receptors (TCRs) composed of γ and δ chains [13]. Their TCR diversity is generated through V(D)J recombination: the δ chain is assembled from variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) segments, while the γ chain derives from V and J segments only [3]. This combinatorial process theoretically enables an enormous repertoire of up to 1018 different TCR sequences [14].

In practice, however, this diversity is funneled into a few dominant functional subsets. The most prominent in humans are Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3 T cells [14]. These subsets arise in distinct developmental waves. Vδ2 T cells emerge early during fetal life (liver at weeks 5–6, thymus at weeks 8–15), while Vδ1 cells expand significantly after birth, around 4–6 months of age [15]. Vδ3 cells are less frequent but contribute to specialized functions, particularly in mucosal and hepatic compartments. This staggered development underpins their distribution across tissues and circulation and shapes their unique immunological roles. This age-dependent shift in the T cell repertoire is a critical consideration for therapeutic manufacturing, as different cell sources, such as adult peripheral blood (Vδ2 dominant), pediatric peripheral blood, and umbilical cord blood (Vδ1 dominant), yield fundamentally different proportions of Vδ1 and Vδ2 T cells, thus influencing the final product’s characteristics and potential applications in cancer, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Unlike αβ T cells, γδ T cells can mount rapid responses without prior antigen priming. This innate-like reactivity positions them as a crucial bridge between innate and adaptive immunity [4]. Understanding the biology and division of labor among Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3 subsets is therefore central to harnessing γδ T cells for therapeutic applications.

2.1 Subset-Specific Differences

Following TCR development, human γδ T cells are classified by Vδ chain usage into three major groups: Vδ1 (tissue-resident, adaptive-like), Vδ2 (blood-dominant, innate-like), and Vδ3 (minor, functionally similar to Vδ1) [5,12]. Collectively, these subsets demonstrate remarkable flexibility, bridging innate and adaptive immunity through diverse receptor-ligand interactions [16–18].

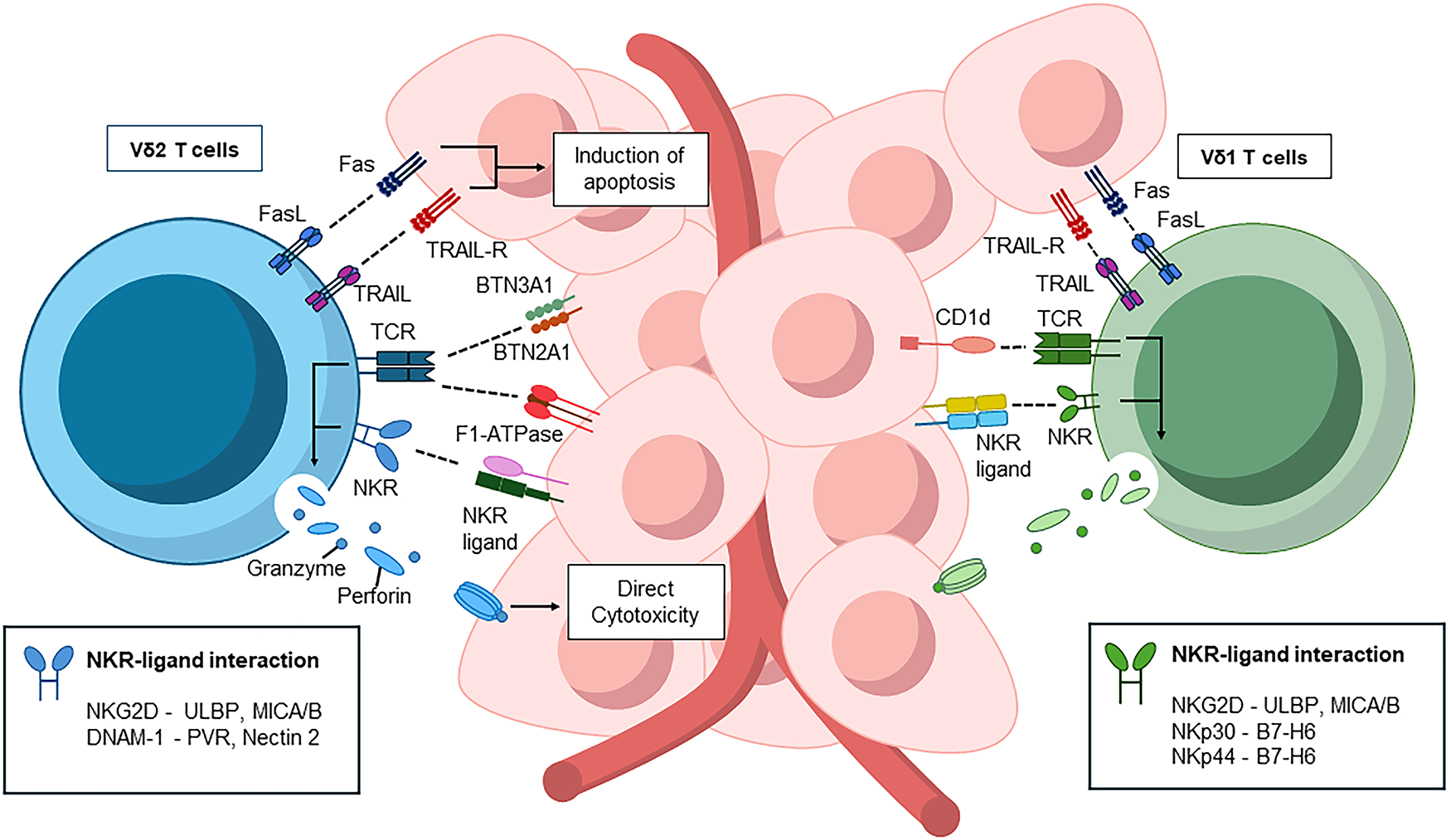

Vδ1 T cells account for roughly one-third of circulating γδ T cells and are enriched in barrier tissues such as the liver, dermis, gut, and epithelium. They can recognize sulfatides presented by CD1d, a non-classical antigen-presenting molecule frequently expressed in cancers [19]. In addition, Vδ1 T cells express activating receptors including natural killer group 2D (NKG2D), NKp30, and NKp44 (Fig. 1). Through NKG2D, they detect stress-induced ligands such as MICA, MICB, and ULBPs, triggering perforin- and granzyme-mediated cytotoxicity [20–22]. NKp30 and NKp44 enable recognition of B7-H6 expressed on tumor cells [23–25]. Developmentally, newborns possess a broad, polyclonal Vδ1 TCR repertoire, whereas adults exhibit “TCR privacy”, where expansion of individual-specific clones leads to unique repertoires [26,27].

Figure 1: Subset-specific recognition of γδ T cells in anti-tumor immunity. Vδ1 T cells, enriched in tissues, recognize CD1d-presented sulfatides and engage NK receptors such as NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, and DNAM-1 to induce cytotoxicity. Vδ2 T cells, dominant in blood, sense phosphoantigen–BTN3A1/BTN2A1 complexes and F1-ATPase/Apo A1, activating cytotoxic programs via perforin, granzymes, Fas/FasL, and TRAIL. All schematics were created in Microsoft PowerPoint. Abbreviations: CD1d, cluster of differentiation 1 D polypeptide; BTN3, butyrophilin subfamily 3 members; DNAM-1, DNAX accessory molecule-1; FasL, Fas ligand; MICA/B: Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I-Related Chain A/B; NK, natural killer; NKG2D, natural killer group 2, member D; NKR, natural killer receptor; PVR, poliovirus receptor; TCR, T-cell receptor; TRAIL-R, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor; ULBP: UL16 Binding Protein

Vδ2, also known as Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, are predominantly found in the adult peripheral blood, comprising 60%–95% of circulating γδ T cells. Their recognition system is highly specialized. The Vγ9Vδ2 TCR detects stress-derived phosphoantigens such as isopentenyl phosphoantigen (IPP) presented by butyrophilins (butyrophilin subfamily 3 member [BTN3]A1/2A) [28–30]. Binding of phosphoantigens to the B30.2 domain of BTN3A1 induces conformational changes that permit BTN2A1 to interact with the Vγ9 chain, forming a recognizable complex [29]. Because the mevalonate pathway, responsible for cholesterol synthesis, is frequently hyperactive in cancer cells, intracellular phosphoantigens (like IPP) accumulate, thereby amplifying BTN3A1-mediated signaling and enhancing γδ TCR activation [31]. In an alternative pathway, Vγ9Vδ2 TCRs recognize surface-expressed F1-ATPase, which complexes with apolipoprotein A I (Apo AI) on tumor cells [32,33] (Fig. 1).

Beyond TCR-mediated recognition, Vδ2 T cells express NK receptors (NKG2D, DNAX accessory molecule-1 [DNAM-1]), CD39, and 4-1BB. NKG2D and DNAM-1 enhance tumor recognition by binding to stress ligands. DNAM-1, in particular, strengthens cytotoxicity by engaging CD155 (poliovirus receptor [PVR] and CD112 (Nectin-2) on tumor cells, promoting immune synapse formation, degranulation, and cytokine release [23]. Upon activation, Vδ2 T cells also upregulate CD16 (FcγRIII), enabling antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against opsonized tumor cells [34]. Functionally, Vδ2 T cells can even cross-present exogenous antigens on MHC class I to CD8+ αβ T cells, further amplifying adaptive responses [34–36]. Complementary molecules such as CD39 and 4-1BB additionally boost secretion of perforin, IFN-γ, and granzymes [37] (Fig. 1).

Vδ3 T cells, although far less frequent in circulation, contribute a distinct functional repertoire. These cells recognize non-peptide antigens presented by CD1d, as well as stress-associated molecules such as Annexin A2, and are particularly enriched in the liver and gut [38–40]. Despite their unique biology, their rarity in peripheral blood, the typical source for clinical manufacturing, has limited their use in therapeutic engineering. Consequently, most translational efforts have centered on the more accessible Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets, which are easier to expand ex vivo and harness for adoptive cell therapy [41–43].

2.2 Anti-Tumor Effects of γδ T Cells

γδ T cells exert potent anti-tumor activity through both direct and indirect mechanisms, setting them apart from conventional αβ T cells [44–46]. Direct mechanisms primarily involve two pathways. First, γδ T cells release perforin and granzymes stored in cytotoxic granules, inducing apoptosis in tumor targets upon TCR or activating receptor engagement (Fig. 1) [47,48]. Second, they trigger death receptor signaling: Fas ligand (FasL) and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expressed on γδ T cells engage Fas and TRAIL receptors on tumor cells, activating caspase-dependent apoptosis [49–51].

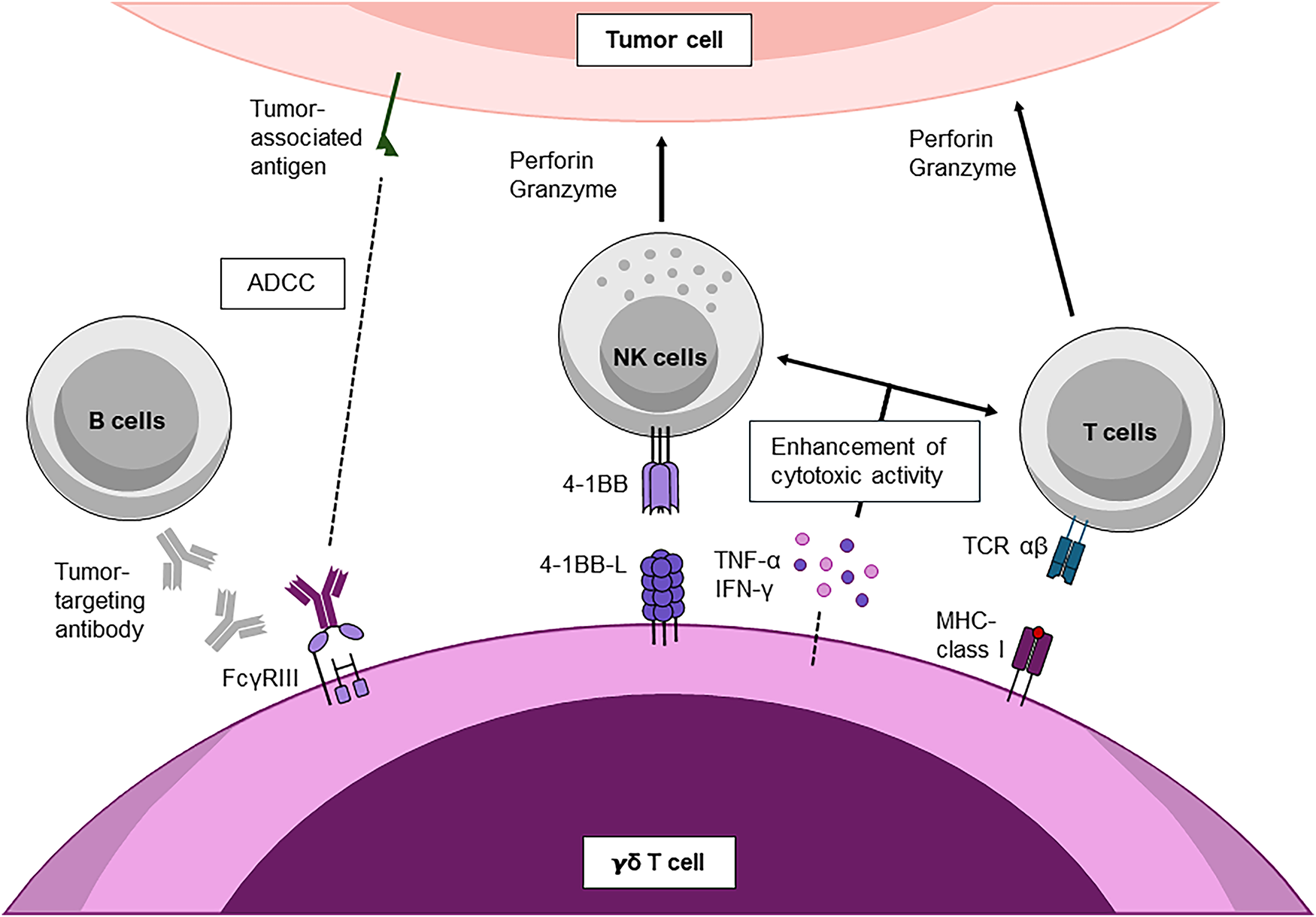

Indirect mechanisms extend their anti-tumor reach by mobilizing other immune cells (Fig. 2). Acting as APCs, γδ T cells activate naïve CD8+ T cells and drive their differentiation into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [52]. This process is reinforced by secreted cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, which enhance CTL effector function [53]. In addition, γδ T cells provide B cell help, promoting differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells. These antibodies not only mediate tumor opsonization but also facilitate ADCC, as activated γδ T cells can upregulate FcγRIII (CD16) and can directly kill antibody-coated tumor cells [34]. γδ T cells also augment NK cell cytotoxicity through co-stimulatory interactions (e.g., 4-1BB Ligand-4-1BB) and cytokine release, further amplifying tumor clearance [37] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Cooperative immune interactions of γδ T cells in anti-tumor immunity. γδ T cells enhance anti-tumor immunity by synergizing with NK, B, and αβ T cells. Through NKG2D, DNAM-1, and 4-1BB/4-1BBL signaling, they amplify NK and T-cell cytotoxicity, while cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) further strengthen responses. Vδ2 subsets can also mediate ADCC through CD16 and cross-present tumor antigens to CD8+ T cells, linking innate recognition to adaptive immunity. All schematics were created in Microsoft PowerPoint. Abbreviations: 4-1BB ligand (CD137 ligand, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9 ligand); ADCC, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; FcγRIII, Fc gamma receptor III; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; T-cell receptor

The therapeutic potential of these mechanisms is magnified when γδ T cells are engineered with CARs. CAR-modified γδ T cells combine MHC-independent innate recognition with CAR-directed specificity, thereby preventing antigen escape while minimizing the risks of GvHD and CRS associated with CAR αβ T cells [54].

Together, these anti-tumor mechanisms highlight the versatility of γδ T cells. They not only deliver direct cytotoxicity but also orchestrate broad immune responses. However, the same functional plasticity that empowers anti-tumor activity can shift toward protective regulation or pathogenic inflammation in autoimmune settings. This dual role positions γδ T cells as a double-edged sword in immunity, a theme explored in the next section.

2.3 Anti-Autoimmune Effects of γδ T Cells

The role of γδ T cells in autoimmunity exemplifies their immunological duality as they can act either as potent regulators or pathogenic drivers depending on their subset identity, tissue localization, and the surrounding cytokine environment [55–57]. This plasticity creates both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic exploitation. On the regulatory side, Vδ1 T cells and FOXP3+ γδ regulatory T cells (γδ-Tregs) contribute to the maintenance of tolerance by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, which suppress autoreactive Th1 and Th17 responses, and by directly eliminating pathogenic lymphocytes through perforin and granzyme release or Fas–FasL–mediated apoptosis [55,56,58]. In addition to suppressing inflammation, these subsets play crucial roles in promoting tissue repair and maintaining barrier homeostasis, highlighting their protective contribution during the resolution phase of autoimmune injury.

Conversely, on the pathogenic edge, Vδ2 T cells exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-23 and IL-1β can differentiate into γδ17 cells, which rapidly produce IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 within hours, well before conventional Th17 cells [59,60]. The secretion of these cytokines recruits neutrophils, damages tissue, and amplifies Th17 responses, thereby establishing a self-sustaining pro-inflammatory loop that drives chronic disease. Such γδ17 activity has been implicated in a range of autoimmune disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis, and osteoarthritis (OA) [59,61,62].

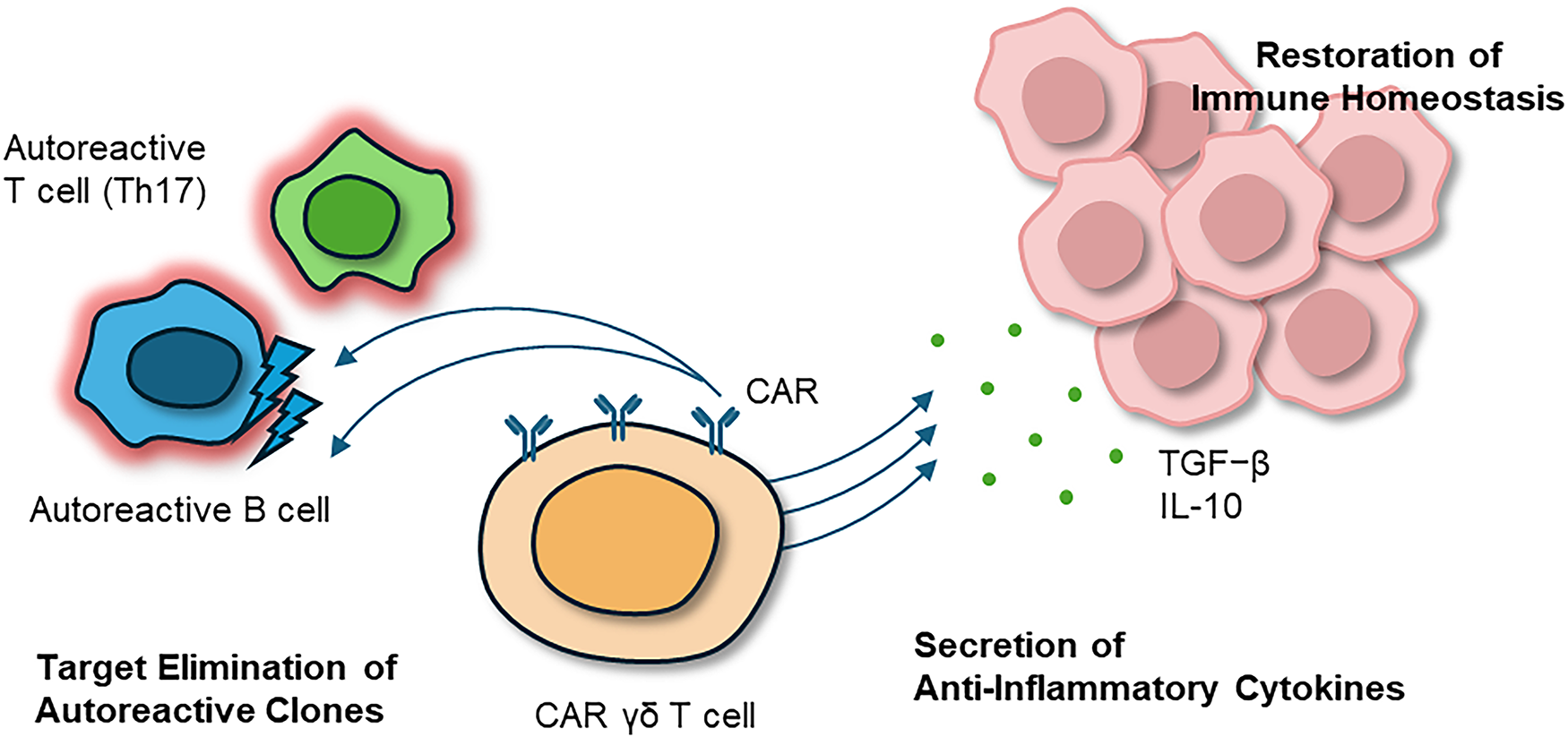

This duality highlights the delicate balance that defines γδ T cell biology in autoimmunity and underscores the need for precise therapeutic steering [63]. CAR γδ T cells can be designed to favor regulatory functions, for instance, by targeting CD19+ autoantibody-producing B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and anti-synthetase syndrome. Such approaches combine two complementary benefits: the selective elimination of autoreactive clones and localized suppression of inflammation through IL-10 and TGF-β release [64–66]. The central challenge remains the enrichment of regulatory-prone subsets while minimizing their conversion into pro-inflammatory γδ17 cells.

Other unconventional T cell subsets also contribute to immune regulation and may intersect with γδ T cell biology in autoimmune contexts. Natural killer T (NKT) cells, a subset of αβ T cells that recognize glycolipid antigens presented by CD1d, rapidly secrete both IFN-γ and IL-4 and can either promote or restrain inflammation depending on the cytokine milieu. Altered NKT cell frequencies and function have been associated with loss of tolerance in rheumatic and autoimmune diseases such as primary Sjögren’s syndrome, SS, SLE, and type 1 diabetes [67]. Double-negative T (DNT) cells, defined as CD3+CD4−CD8− lymphocytes, represent another unconventional subset with emerging regulatory functions. These cells suppress autoreactive B and T cells, and their depletion correlates with heightened disease activity in pediatric and adult autoimmune disorders [68]. Together with γδ T cells, these innate-like lymphocytes form an integrated regulatory axis that bridges adaptive and innate immunity, collectively maintaining immune homeostasis in health and disease.

Building on this foundation, the next section turns to the role of CAR γδ T cells in cancer immunotherapy, where their unique biological features are being actively translated into therapeutic applications.

3.1 Engineering and Expansion Methods

The manufacturing process for CAR γδ T cells begins with a critical strategic decision: selecting the starting population from the two major γδ T cell subsets, Vδ1 and Vδ2 [69,70]. This choice dictates the entire downstream process, from the expansion methodology to the expected in vivo behavior of the final product. For therapies where long-term persistence and durable function within tissue microenvironments are essential, the tissue-resident Vδ1 subset offers distinct advantages. These cells are intrinsically resistant to activation-induced cell death (AICD) and exhaustion [71]. To expand these typically rare cells, specialized protocols have been developed that begin with the depletion of αβ T cells and NK cells to enrich the Vδ1 population. The purified Vδ1 cells are then stimulated with anti-CD3 and IL-15 to drive proliferation [6,70,72]. This approach, often referred to as a Delta One T (DOT) protocol, yields a high-purity Vδ1 product with potent anti-tumor activity, characterized by high expression of activating receptors such as NKG2D and DNAM-1 and low expression of exhaustion markers, including programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-containing protein 3 (TIM-3) [23,70,73].

In contrast, when rapid, scalable, and cost-effective manufacturing is the priority, the peripheral blood-dominant Vδ2 subset presents a more practical option. Unlike Vδ1 cells, Vδ2 TCRs can be directly and potently activated by small phosphoantigens such as 2M3B1PP or nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates like zoledronate [69,71,74]. This unique feature makes their expansion relatively straightforward and typically involves stimulating total peripheral blood mononuclear cells with these agents in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. To support more robust and large-scale expansion for clinical applications, engineered artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) have also been employed. These cells, often derived from the K562 line, are modified to express multiple co-stimulatory ligands that drive sustained proliferation of γδ T cells [75].

Once sufficient expansion has been achieved, the next critical step is genetic engineering to equip γδ T cells with a CAR, thereby redirecting their specificity toward a defined tumor antigen [75]. The design of the CAR construct is central to achieving a robust and sustained anti-tumor response. Effective CAR signaling required the integration of a primary activation signal, provided by the CD3ζ domain, with a co-stimulatory signal that supports survival and proliferation [76]. For this reason, most current clinical candidates employ second-generation CARs that combine CD3ζ with either CD28 or 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains [77]. The choice of co-stimulatory domain has significant functional consequences. CARs containing CD28 drive immediate and potent effect responses, including high levels of IFN-γ secretion, while CARs incorporating 4-1BB promote greater persistence and long-term memory formation [77].

The method for transferring the CAR gene is another critical consideration, as the desired duration of expression determines the most appropriate delivery strategy. When safety is the primary concern, or when exploring new targets, transient expression is advantageous. mRNA electroporation is the leading approach in this context and yields high levels of CAR expression that gradually decline within three to five days, providing a built-in safety switch [78]. For applications requiring durable responses and long-term remission, stable integration of the CAR gene is necessary. Viral vectors remain the most established tools for this purpose. γ-retroviral vectors, though effective, are limited to transducing dividing cells and therefore require cell activation [69,71,74]. Lentiviral vectors, by contrast, can efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, making them a more versatile option [79,80]. Beyond viral systems, non-viral platforms such as DNA transposons, including Sleeping Beauty, are also being developed to provide stable integration with potentially lower costs and reduced regulatory hurdles [75].

Ultimately, the optimal combination of γδ T cell subset, expansion platform, CAR design, and gene delivery method must be chosen to balance therapeutic potency, persistence, and safety. This careful orchestration of engineering and manufacturing strategies is central to realizing the full clinical potential of CAR γδ T cells in cancer therapy.

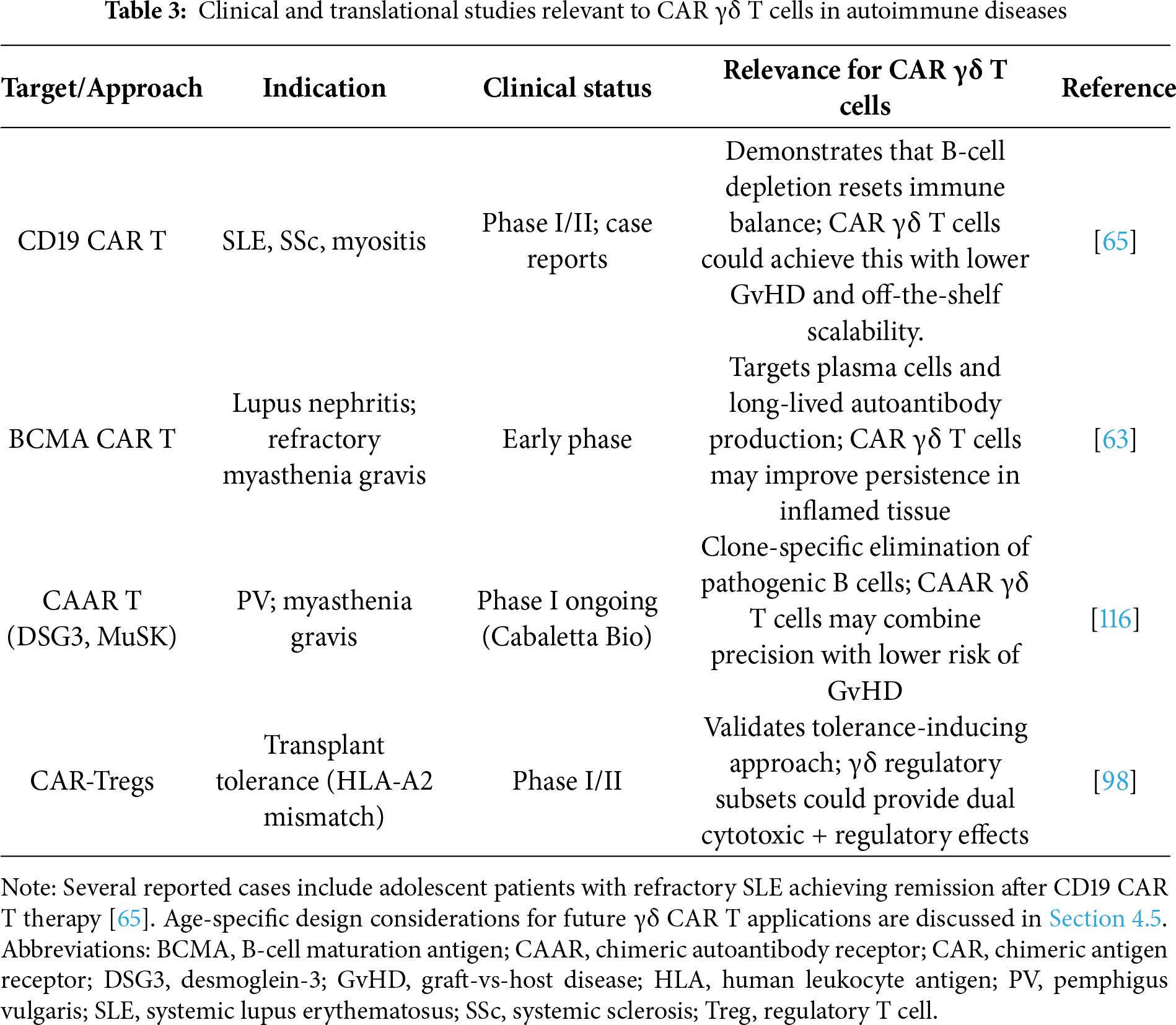

3.2 Applications in Hematologic Malignancies and CAR Targets

The therapeutic application of CAR γδ T cells in hematologic malignancies is guided by the expression of lineage-specific surface antigens on malignant cells. B-cell cancers have provided the prototypical disease model, building on the remarkable success of CD19 as a CAR T target [75]. Preclinical studies confirmed that CAR γδ T cells can be engineered to target CD19 effectively, establishing a foundation for further development [75]. However, tumor relapse due to antigen loss or downregulation remains a major challenge in CAR therapies. To address this, CD20, a B-cell-restricted antigen and long-standing target of monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab, has emerged as an alternative [74,81]. CD22 is also under investigation, particularly in patients relapsing after CD19-directed therapies [82].

Expanding beyond lymphoid malignancies, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presents a more complex challenge due to its heterogeneity and the overlap of antigen expression between leukemic and normal hematopoietic stem cells. The goal in AML is to identify antigens expressed on leukemia stem cells but absent from vital progenitors. CD123, the α chain of the IL-3 receptor, has been validated as one such target [70]. Preclinical studies with allogeneic Vδ1 CAR γδ T cells against CD123 demonstrated robust anti-leukemic activity without evidence of immunogenicity in xenograft models [70]. Another promising target is c-kit (CD117), a receptor crucial for AML cell survival, where an innovative CAR design utilized the natural c-kit ligand (stem cell factor) in place of the traditional antibody fragment (Table 1) [83].

Encouraging preclinical data have paved the way for early-phase clinical trials. A Phase I trial of Vδ1 CAR γδ T cells targeting CD20 in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NCT04735471) reported a 78% complete remission rate with only mild CRS (Grades 1–2) [6]. Similarly, an early clinical trial of CD19-directed CAR γδ T cells (NCT02656147) confirmed the fundamental safety of the platform, with no severe adverse events and initial signals of efficacy [87].

3.3 Applications in Solid Tumor Therapy

While CAR αβ T cells have revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies, their efficacy in solid tumors has been limited. Solid tumors pose multiple barriers, including dense stromal architecture that restricts infiltration and highly immunosuppressive microenvironments that promote T cell exhaustion. γδ T cells are particularly well suited to address these challenges because of their innate tissue-homing capacity and their ability to recognize stressed cells independently of MHC presentation.

Building on these advantages, CAR γδ T cells are being engineered against a wide range of solid tumor antigens. Preclinical studies demonstrate that these cells often outperform CAR αβ T cells because of their dual-recognition capacity, combining CAR specificity with intrinsic recognition of stress ligands [93]. For example, CAR γδ T cells directed against claudin18.2 showed superior cytotoxicity compared with CAR αβ T cells, likely due to synergistic recognition of both the CAR antigen and stress-associated molecules [88]. Similar strategies are now being extended to diverse antigens, including glypican-3 (GPC-3) in hepatocellular carcinoma [71,94], folate receptor-α in triple-negative breast cancer [90], CD44v6 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [95], and the aberrant glycoform MUC1-Tn in adenocarcinomas [91] (Table 1).

γδ T cells are also being deployed against particularly difficult-to-treat malignancies such as glioblastoma. This tumor is protected by the blood-brain barrier and an intensely suppressive TME, making it highly resistant to conventional therapies. To overcome these defenses, researchers are combining CAR γδ T cells with oncolytic viruses, using the virus to inflame the tumor and convert a “cold” microenvironment into one more permissive for T-cell activity [89,96,97].

3.4 Interactions with Immunosuppressive TME

The long-term success of CAR γδ T cells in solid tumors depends on their ability to withstand and remodel the immunosuppressive TME. The TME deprives T cells of essential survival signals while delivering inhibitory cues that induce dysfunction. One major limitation is the scarcity of homeostatic cytokines such as IL-15, which leads to poor persistence. To overcome this, CAR γδ T cells have been engineered to co-express the IL-15/IL-15Rα complex, creating an autocrine survival loop that sustains their function [70,71].

Resistant to suppressive signaling is equally important. “Armoring” strategies have been introduced to protect engineered cells from inhibitory pathways and enhance their activity [10]. For example, CAR γδ T cells can be designed to secrete anti-PD-1 antibodies locally, neutral PD-L1-mediated suppression. Similarly, expression of a dominant-negative TGF-β receptor (dnTGFβRII) renders them insensitive to one of the TME’s most potent inhibitory cytokines [10].

Armoring also expands therapeutic breadth by equipping cells to counter tumor heterogeneity. An innovative approach is to engineer CAR γδ T cells to secrete Bispecific T-cell Engagers (BiTEs), which recruit bystander αβ T cells by binding both CD3 and a secondary tumor antigen [98,99]. This transforms the suppressive TME into a cooperative anti-tumor environment, broadening the scope of tumor cell elimination and reducing the risk of antigen escape. Early clinical studies are now beginning to test such multifunctional CAR γδ T cells against targets including NKG2D ligands or GPC3 [100].

3.5 New Advancements and Future Directions in CAR γδ T Cells

A persistent challenge for CAR therapies is tumor relapse driven by antigen escape, in which cancer cells downregulate or lose the targeted antigen. To address this, γδ T cells are being equipped with novel receptor designs that enhance recognition breadth. One such innovation is the dual-specificity γδ TCR (DS-TCR), which combines a high-affinity Vγ9 TCR domain targeting tumor-associated antigens such as MAGE-A4 with a Vδ2 domain [101]. This hybrid design enables simultaneous recognition of the primary antigen and stress-associated ligands, thereby reducing the likelihood of antigen escape. Another novel construct is the TCR-Ig receptor, in which a short-chain variable fragment (scFV) is fused directly to the constant region of the TCR γ chain. This design achieved robust signaling without requiring a separate co-stimulatory domain and may help mitigate toxicities associated with chronic CAR activation [92].

Progress is also being made in overcoming manufacturing barriers. A major limitation for Vδ1 T cells has been their resistance to viral transduction. This obstacle has largely been resolved through lentiviral vectors pseudo-typed with a baboon envelope (BaEV-LV), which achieved up to 80% transduction efficiency in these difficult-to-engineer cells [102]. mRNA electroporation offers a complementary strategy by providing transient CAR expression with a built-in safety switch, as the effect naturally wanes after several days [86]. Expansion protocols are being further optimized; for instance, a novel bisphosphonate prodrug ThP enables highly selective Vδ2 expansion to >90% purity with over 1000-fold proliferation [8].

Ultimately, the field aims to eliminate donor dependence by generating universal, standardized cell products. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer a transformative solution by providing an unlimited source of CAR γδ T cells that are genetically uniform, quality-controlled, and truly “off-the-shelf” [9,103]. Combination therapies represent another exciting frontier. A guiding principle here is chemo-immunotherapy, in which chemotherapy is not only cytotoxic but also sensitizes tumors to immune attack. The pegylated liposomal alendronate-doxorubicin (PLAD) nanomedicine platform exemplifies this approach, co-delivering doxorubicin and the γδ T cell activator alendronate in a single liposome. Doxorubicin induces immunogenic cell death, while alendronate sensitizes tumor cells to γδ T cell killing, producing complete tumor regression in preclinical models [104].

Together, these innovations highlight the rapid evolution of CAR γδ T cell therapy. By combining advances in receptor design, gene transfer technologies, manufacturing platforms, and combination strategies, the field is moving steadily toward safe, durable, and broadly accessible treatments for both hematologic and solid malignancies.

4 CAR γδ T Cells in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases

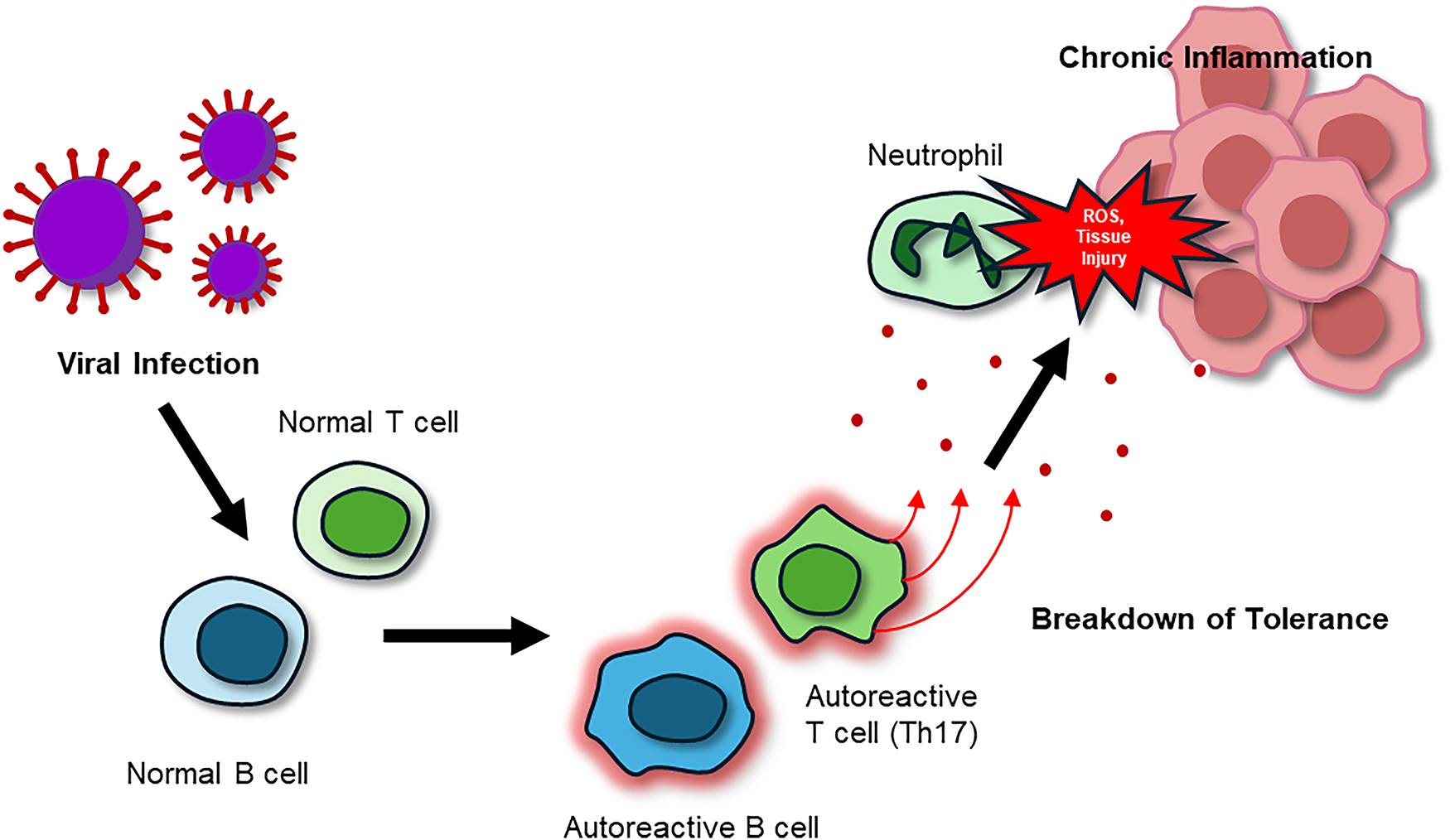

Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (AIDs) arise from dysregulated immune tolerance, resulting in persistent autoreactive B and T cell activity. Classical examples include SLE, MS, RA, and type 1 diabetes (T1D) (Fig. 3). Current therapies, such as immunosuppressants, biologics including anti-CD20 or anti-TNF antibodies, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, can reduce disease activity but remain limited by incomplete efficacy, frequent relapses, and significant toxicity. Inspired by the success of CAR T cell therapies in cancer, researchers are now exploring engineered immune cell strategies to reset immune balance and restore tolerance [11,105].

Figure 3: The pathogenic cycle of AIDs. Viral or environmental triggers activate autoreactive B cells and Th17 T cells, resulting in autoantibody production, pro-inflammatory cytokine release (IL-17, TNF-α), and neutrophil recruitment. Neutrophils intensify tissue destruction by releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS), reinforcing a chronic feedback loop of inflammation, immune cell activation, and progressive tissue injury. Abbreviations: AIDs, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases; IL-17, interleukin-17; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Th17, T helper 17 cell

Although most studies to date have centered on cancer, the biology of γδ T cells uniquely positions them as candidates for autoimmune therapy. Their combination of MHC-independent recognition, potent cytotoxicity, and intrinsic regulatory capacity allows them not only to eliminate autoreactive clones but also to promote tissue repair and restore homeostasis [53,55,56] (Fig. 4). Early clinical trials with CD19-directed CAR αβ T cells in lupus and other autoantibody-driven diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc) and myositis, have already demonstrated that targeted B cell depletion can induce remissions [64,106,107]. However, conventional CAR αβ T strategies remain constrained by reliance on autologous products, prolonged B cell aplasia, and risks of toxicities such as CRS and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) [108–110]. In this setting, CAR γδ T cells may offer a safer and more versatile alternative, combining targeted cytotoxicity with immunoregulatory effects while minimizing alloreactivity and targeted toxicity [53,55,56].

Figure 4: Therapeutic intervention with CAR γδ T cells in AIDs. Engineered CAR γδ T cells interrupt this cycle by selectively eliminating autoreactive B and T cells while secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β). Through this combined cytotoxic and regulatory activity, CAR γδ T cells not only suppress chronic inflammation but also re-establish immune tolerance and promote long-term tissue repair and functional recovery. Abbreviations: AIDs, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor

4.1 Engineering and Expansion Strategies of CAR γδ T Cells in AIDs

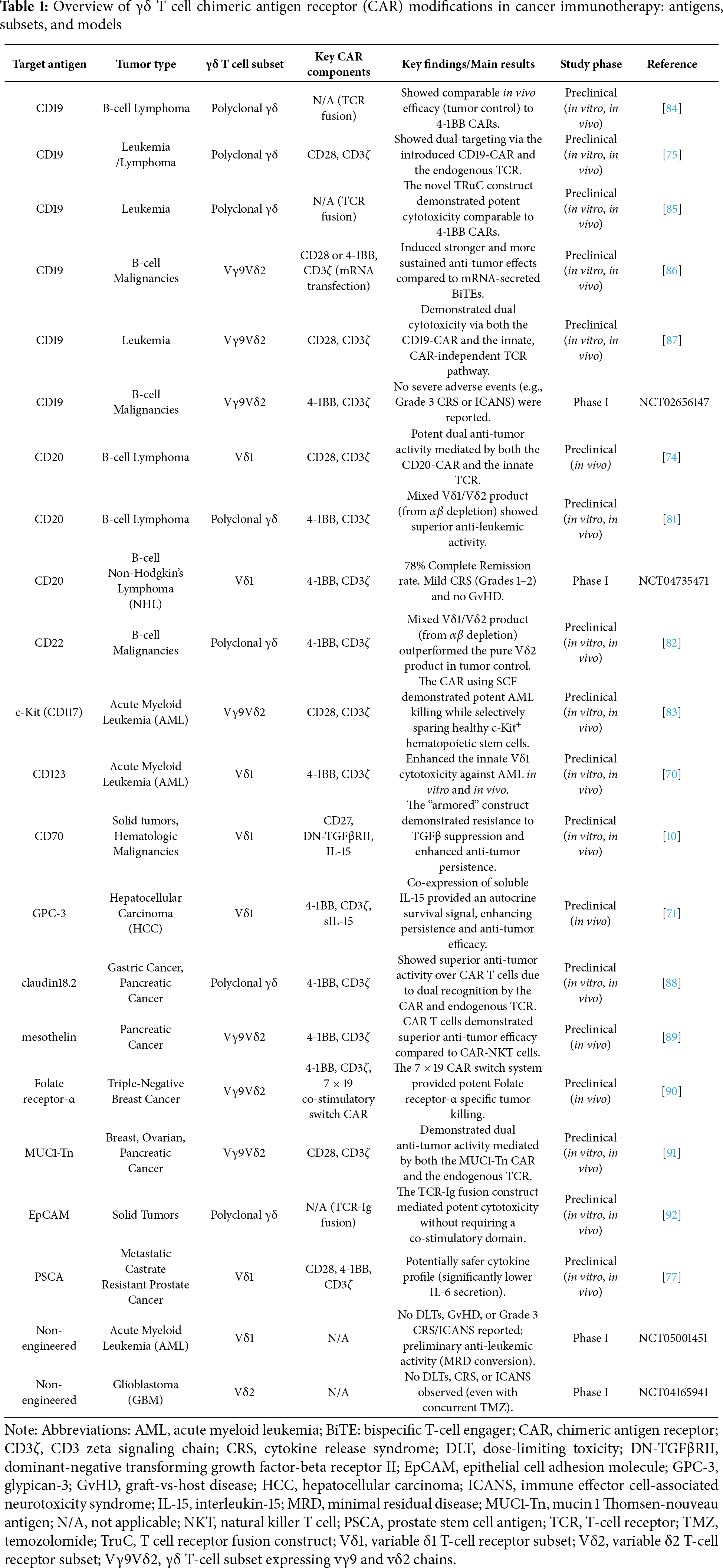

While many of the same platforms used to engineer γδ T cells for cancer therapy are technically applicable to autoimmunity [69,72], their therapeutic purpose differs substantially. In oncology, persistence and high-level cytotoxicity are desirable, whereas in autoimmunity, the aim is to selectively eliminate autoreactive clones and re-establish tolerance without inducing chronic immunosuppression [11,63]. For this reason, transient CAR expression is especially attractive. Short-lived CAR γδ T cells can provide controlled clearance of autoreactive cells while preserving protective immunity; in T1D, for example, transient therapy may conserve residual β-cell function [11,111]. When longer-term control is required, stable CAR integration can be combined with tolerogenic programming, such as IL-10 or TGF-β knock-ins, pushing engineered γδ T cells toward regulatory phenotypes [11,63]. These approaches provide flexible platforms for disease-specific applications, summarized in Table 2.

Advanced genome editing adds another layer of precision. CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to delete inhibitory checkpoints, such as PD-1, or to insert immunoregulatory cytokine genes, reinforcing tolerance. Logic-gated CARs, designed to restrict activation to inflammatory contexts, offer an additional safeguard [112,113]. In parallel, armoring strategies such as IL-15 co-expression or dnTGF-β receptors can enhance persistence and stability in chronically inflamed tissues [63,114]. Manufacturing considerations are also particularly relevant, since autoimmune patients may require repeat dosing or broad access. iPSC-derived γδ T cells represent a scalable, renewable source of “off-the-shelf” products, enabling standardized treatment at the population scale [9,103].

4.2 Precision Targeting Approaches

Autoreactive B cells are central drivers of many autoimmune disorders, and clinical evidence in SLE and SS shows that anti-CD19 CAR T therapy can induce long-term remission [65,106,107]. These results support extending CAR γδ approaches to CD19, CD20, and BCMA, where MHC-independent recognition may provide additional safety and efficacy [112]. Beyond broad depletion, precision strategies are emerging to preserve protective immunity. Chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR) T cells, which display autoantigen domains, have already shown success in pemphigus vulgaris (PV) with desmoglein-3 (DSG3)-CAAR and in myasthenia gravis (MG) with muscle-specific kinase (MuSK)-CAAR. Applying CAAR designs to γδ T cells could merge antigen-level precision with the reduced risk of GvHD inherent to this lineage [115,116].

γδ T cells may also be engineered to mimic tolerogenic regulatory cells. Designs that program IL-10 or TGF-β secretion parallel the approach of CAR Tregs, which have shown promise in restoring tolerance in transplantation and autoimmunity [117–119]. The stability of these regulatory phenotypes, however, remains a challenge, as regulatory cells can convert into effector-like states under inflammatory pressure. In addition to B cells, autoreactive T cells remain key drivers in conditions such as MS, RA, and T1D. The tissue-tropic nature of Vδ1 subsets could be exploited to engineer CAR γδ T cells with organ-specific homing properties, such as to the central nervous system (CNS) or pancreatic islets, where they could exert localized immunoregulation while minimizing systemic immunosuppression.

Synthetic biology provides further precision. Switchable CARs controlled by small molecules allow temporal regulation of therapeutic activity, while SynNotch or dual-input CARs restrict activation to inflamed tissues by requiring both antigen recognition and inflammatory signals [54,108,120]. Integrating such systems into γδ T cells may yield highly localized control of autoimmunity, balancing elimination of pathogenic clones with preservation of protective immunity.

4.3 Applications across Autoimmune Indications

Different autoimmune diseases present distinct therapeutic opportunities for CAR γδ T cells. In SLE, where autoreactive B cells drive pathology, γδ T cells engineered to target CD19 or BCMA and to co-secrete IL-10 could reduce autoantibody production while simultaneously restoring tolerance [64,106,117]. In RA and MS, where γδ17–Th17 loops sustain inflammation, logic-gated CAR γδ T cells responsive to IL-17 signals could disrupt pathogenic feedback circuits without broadly suppressing immunity [59,112,121]. Organ-specific antibody-mediated diseases represent natural candidates for CAAR strategies, such as DSG3-CAAR T cells in PV or MuSK-CAAR γδ T cells in MG, which could precisely eliminate autoreactive clones while preserving protective immunity [117,118].

In T1D, CAR γδ T cells could selectively clear autoreactive lymphocytes while preserving β-cell function. The natural epithelial-homing properties of Vδ1 subsets may provide an additional advantage by directing engineered cells to pancreatic islets [53,111]. Chronic inflammatory conditions may also benefit. In psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease, designs that suppress γδ17 activity while enhancing IL-10 and TGF-β responses could restore tissue tolerance [56,57,59]. In OA, where IL-17 and senescent cells accelerate joint damage, CAR γδ T cells targeting stress ligands may protect cartilage and slow disease progression [57,61]. These disease-specific applications illustrate the potential of γδ CARs to provide tailored interventions that combine cytotoxic and regulatory functions according to the context (Table 2).

4.4 Safety, Toxicity, and Control Mechanisms

Safety remains a central concern in adoptive immunotherapy. Conventional αβ CAR T cells often induce CRS, neurotoxicity, and prolonged B-cell aplasia [108,110,113]. In contrast, CAR γδ T cells may offer intrinsic safety advantages due to their MHC-independent recognition, lower alloreactivity, and ability to secrete IL-10 and TGF-β, which can dampen excessive inflammation. Subset choice may influence risk, since Vδ1 T cells with tissue-homing potential could drive localized inflammation if dysregulated, while Vδ2 T cells, as strong cytokine producers, may increase the risk of excessive IL-17 or IFN-γ release.

To mitigate risks, multiple control strategies are being developed. Suicide switches such as inducible caspase-9 allow emergency ablation of infused cells [93,122]. Transient CAR expression via mRNA electroporation can provide short-term clearance of autoreactive clones during acute flares without long-lasting immunosuppression [79,113,123]. Long-gated or dual-input CARs further refine control by restricting activity to the inflamed environment [115,116]. Yet each approach has limitations, such as delayed action of suicide switches, repeated dosing requirement for transient CARs, and experimental status for logic-gated systems. Achieving the right balance between efficacy and safety will require matching control mechanisms to clinical context, such as transient interventions for acute relapses versus durable tolerogenic reprogramming for chronic disease.

4.5 Clinical Translation and Future Directions

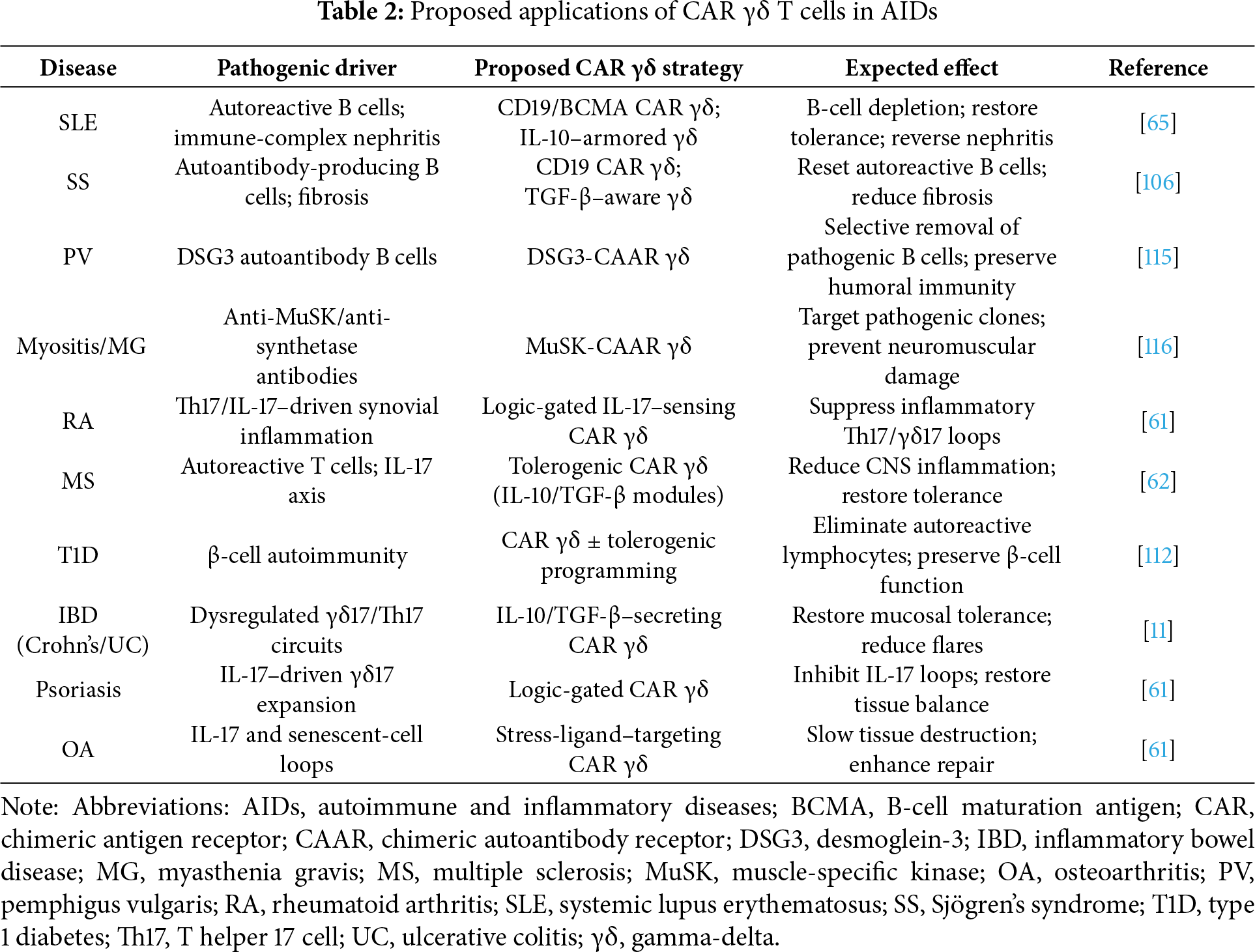

Collectively, preclinical investigations of CAR γδ T cells across autoimmune and inflammatory indications (Table 2) highlight their versatility as next-generation immune modulators and lay the groundwork for translation into clinical studies. Although direct clinical evidence for CAR γδ T cells in autoimmunity is not yet available, the success of αβ CAR T cells in SLE, SS, and anti-synthetase syndrome provides compelling proof of principle (Table 3) [65,106,107]. Extending this to γδ T cells offers additional benefits, including reduced GvHD risk, intrinsic cytokine-mediated immunoregulation, and the feasibility of allogeneic manufacturing [11,63]. Advances in iPSC technology now allow standardized γδ T cell sources, and automated closed system processes are improving scalability. Gene delivery options such as mRNA electroporation provide transient expression for flares, while viral integration can provide durable effects when paired with tolerogenic modifications such as IL-10 or TGF-β knock-ins [63,78,86,103].

Age-specific immune considerations present both challenges and opportunities for translating CAR γδ T cell therapies into autoimmune diseases. γδ T cell ontogeny also varies with age: neonates and children are dominated by highly reactive Vγ9Vδ2 cells with potent innate-like cytotoxicity, whereas adults harbor greater proportions of tissue-resident Vδ1 cells with adaptive-like or regulatory traits [124,125]. Pediatric cases, particularly childhood-onset SLE and T1D, often display greater disease activity, earlier organ involvement, and stronger interferon and IL-17-driven inflammation than adult-onset forms [11,65]. Recent reports have documented complete remission of refractory pediatric lupus nephritis following CD19-CAR T therapy, including a 15-year-old patient who achieved rapid renal recovery and sustained B-cell depletion [11,116]. These findings demonstrate that immune-reset therapy is feasible and effective even within developing immune systems, supporting cautious extension to younger patients. These age-specific developmental distinctions have direct engineering implications: transient, mRNA-based CAR γδ products or reduced-intensity conditioning may best suit pediatric use to avoid prolonged immunosuppression and preserve vaccine responsiveness, whereas durable, tolerogenic CAR γδ cells incorporating IL-10 or TGF-β modules may benefit adults with chronic, fibrosis-prone inflammation. Age-tailored dosing, persistence control, and long-term follow-up for growth and revaccination should therefore accompany future γδ CAR T cell trials.

The potential skewing of γδ T cells toward pathogenic γδ17 phenotypes in inflammatory environments must be addressed through optimized culture, checkpoint editing, or logic-gated designs [59,60,101]. Target identification beyond bulk B cell depletion will be necessary, with CAAR-based strategies against autoantigen-specific clones offering one promising avenue [115,116]. Looking ahead, CAR γδ T cells may emerge as dual-function therapies that combine targeted cytotoxicity with active restoration of tolerance. Advances in antigen discovery, synthetic biology circuits, and microbiome modulation are opening new horizons for precision design [28,29,113,122].

For early clinical translation, initial studies will likely focus on well-defined patient groups with clear biomarkers of autoreactivity, such as high autoantibody titers in SLE or DSG3-specific B cells in PV. Safety-first designs incorporating suicide switches, transient expression, or logic-gated systems should guide these trials. Over time, combination strategies may broaden their application. Pairing CAR γδ T cells with tolerogenic vaccines or low-dose IL-2 could reinforce regulatory networks, while integration with checkpoint blockade or anti-fibrotic therapies may overcome resistance in refractory settings [114,120]. These early and ongoing studies are summarized in Table 3, which outlines how foundational preclinical advances are now transitioning toward clinical translation.

CAR γδ T cells have progressed from an intriguing idea to a rapidly advancing therapeutic platform with the potential to reshape cellular immunotherapy across cancer and autoimmunity. They are not simply an alternative to CAR αβ T cells but a biologically distinct and versatile system that merges innate stress sensing with adaptive precision. Their defining features, like the MHC-independent recognition, innate stress sensing, and the feasibility of universal “off-the-shelf” manufacturing, position them as a superior foundation for next-generation therapies. Preclinical studies in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors have demonstrated potent antitumor activity, while emerging data in autoimmune models highlight their ability to eliminate autoreactive clones, restore immune tolerance, and promote tissue homeostasis. Together, these findings suggest that CAR γδ T cells bridge two historically separate domains, offering a unified framework for both immune activation and immune regulation.

The field now faces the pivotal task of answering the question of whether CAR γδ therapies can fully deliver this promise. Key translational challenges persist: achieving subset-specific expansion, maintaining persistence without exhaustion, and preventing cytokine-driven toxicities. Yet rapid advances in single-cell multi-omics, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven antigen discovery, and iPSC-derived manufacturing are converging to address these limitations by enhancing precision, safety, and scalability. Simultaneously, synthetic biology tools-including logic gates, switchable circuits, and cytokine armoring-are transforming γδ T cells into programmable immune agents that can be tailored to disease-specific demands.

Clinically, success will depend on integrating engineering advances with patient-specific biology. Pediatric and adult experiences with CAR T therapy in lupus illustrate the feasibility of immune-reset approaches and highlight the need for age-tailored dosing, persistence control, and long-term safety monitoring. Early trials combining CAR γδ T cells with checkpoint blockade, TGF-β inhibition, or tolerogenic modules will test whether this balance can be achieved.

If these efforts succeed, CAR γδ T cells could inaugurate a new therapeutic paradigm: a single, flexible platform that bridges tumor eradication and immune restoration, transforming immune reprogramming from disease-specific intervention into a broadly accessible form of precision medicine that no other immunotherapy has been able to achieve so far.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1A3059820) (to Jea-Hyun Baek).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jea-Hyun Baek; writing—original draft preparation, Chanu Lee, Suhyun Che; writing—review and editing, Jea-Hyun Baek; supervision, Jea-Hyun Baek. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| aAPCs | Artificial antigen-presenting cells |

| ADCC | Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AICD | Activation-induced cell death |

| AIDs | Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases |

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| Apo AI | Apolipoprotein AI |

| BaEV-LV | Baboon envelope–pseudotyped lentiviral vector |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BiTE | Bispecific T-cell engager |

| BTN2A1 | Butyrophilin subfamily 2 member A1 |

| BTN3A1 | Butyrophilin subfamily 3 member A1 |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CAR αβ T cells | Chimeric antigen receptor alpha beta T cells |

| CAR γδ T cells | Chimeric antigen receptor gamma delta T cells |

| CAR-Tregs | Chimeric antigen receptor regulatory T cells |

| CAAR | Chimeric autoantibody receptor |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats–Cas9 |

| CRS | Cytokine release syndrome |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DLBCL | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| DLT | Dose-limiting toxicity |

| DNAM-1 | DNAX accessory molecule-1 (CD226) |

| dnTGFβRII | Dominant-negative transforming growth factor-β receptor II |

| DOT | Delta One T protocol |

| DSG3-CAAR | Desmoglein-3 chimeric autoantibody receptor |

| DS-TCR | Dual-specificity T cell receptor |

| EAE | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| FasL | Fas ligand |

| F1-ATPase | F1 adenosine triphosphatase |

| GPC2 | Glypican-2 |

| GPC3 | Glypican-3 |

| GvHD | Graft-vs-host disease |

| HLA-E | Human leukocyte antigen-E |

| ICANS | Immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| IL-2/-7/-10/-12/-15/-17/-18/-21 | Interleukins 2, 7, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, and 21 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IPP | Isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| ITAMs | Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs |

| MAGE-A4 | Melanoma-associated antigen A4 |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| MHC-independent | Major histocompatibility complex–independent |

| MICA | MHC class I chain-related protein A |

| MICB | MHC class I chain-related protein B |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MRS | Minimal residual disease |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| MuSK-CAAR | Muscle-specific tyrosine kinase chimeric autoantibody receptor |

| MUC1-Tn | Mucin 1-Thomsen nouveau glycoform |

| NCRs | Natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp30, NKp44) |

| NK | Natural killer |

| NKG2D | Natural killer group 2, member D |

| NKR | Natural killer receptor |

| NKp30 | Natural cytotoxicity receptor p30 |

| NKp44 | Natural cytotoxicity receptor p44 |

| NKT | Natural killer T cell |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PLAD | Phosphoantigen–loaded alendronate–doxorubicin platform |

| PVR | Poliovirus receptor (CD155) |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| scFv | Single-chain variable fragment |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| SS | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| SSc | Systemic sclerosis |

| T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| Th17 | T helper 17 cell |

| TIM-3 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain–containing protein 3 |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TruC | T cell receptor fusion construct |

| Vδ1/Vδ2 | Variable delta 1/variable delta 2 T-cell receptor subsets |

| Vγ9Vδ2 | Gamma delta T-cell subset expressing Vγ9 and Vδ2 chains |

| ZOL | Zoledronate |

References

1. Raute K, Strietz J, Parigiani MA, Andrieux G, Thomas OS, Kistner KM, et al. Breast cancer stem cell-derived tumors escape from γδ T-cell immunosurveillance in vivo by modulating γδ T-cell ligands. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11(6):810–29. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kattamuri L, Mohan Lal B, Vojjala N, Jain M, Sharma K, Jain S, et al. Safety and efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2025;45(1):18. doi:10.1007/s00296-024-05772-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cieslak SG, Shahbazi R. Gamma delta T cells and their immunotherapeutic potential in cancer. Biomark Res. 2025;13(1):51. doi:10.1186/s40364-025-00762-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zlatareva I, Wu Y. Local γδ T cells: translating promise to practice in cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2023;129(3):393–405. doi:10.1038/s41416-023-02303-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Holtmeier W, Pfänder M, Hennemann A, Zollner TM, Kaufmann R, Caspary WF. The TCR-delta repertoire in normal human skin is restricted and distinct from the TCR-delta repertoire in the peripheral blood. J Investig Dermatol. 2001;116(2):275–80. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01250.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Neelapu SS, Hamadani M, Miklos DB, Holmes H, Hinkle J, Kennedy-Wilde J, et al. A phase 1 study of ADI-001: anti-CD20 CAR-engineered allogeneic gamma delta (γδ) T cells in adults with B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):7509. doi:10.1200/jco.2022.40.16_suppl.7509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Jung S, Baek JH. The potential of T cell factor 1 in sustaining CD8+ T lymphocyte-directed anti-tumor immunity. Cancers. 2021;13(3):515. doi:10.3390/cancers13030515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Y, Wang L, Seo N, Okumura S, Hayashi T, Akahori Y, et al. CAR-modified Vγ9Vδ2 T cells propagated using a novel bisphosphonate prodrug for allogeneic adoptive immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10873. doi:10.3390/ijms241310873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou Y, Li M, Zhou K, Brown J, Tsao T, Cen X, et al. Engineering induced pluripotent stem cells for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2022;14(9):2266. doi:10.3390/cancers14092266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nishimoto KP, Lamture G, Chanthery Y, Teague AG, Verma Y, Au M, et al. ADI-270: an armored allogeneic gamma delta T cell therapy designed to target CD70-expressing solid and hematologic malignancies. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(7):e011704. doi:10.1136/jitc-2025-011704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Yu J, Yang Y, Gu Z, Shi M, La Cava A, Liu A. CAR immunotherapy in autoimmune diseases: promises and challenges. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1461102. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1461102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kabelitz D, Kalyan S, Oberg HH, Wesch D. Human Vδ2 versus non-Vδ2 γδ T cells in antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(3):e23304. doi:10.4161/onci.23304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Born W, Miles C, White J, O’Brien R, Freed JH, Marrack P, et al. Peptide sequences of T-cell receptor delta and gamma chains are identical to predicted X and gamma proteins. Nature. 1987;330(6148):572–4. doi:10.1038/330572a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sebestyen Z, Prinz I, Déchanet-Merville J, Silva-Santos B, Kuball J. Translating gammadelta (γδ) T cells and their receptors into cancer cell therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(3):169–84. doi:10.1038/s41573-019-0038-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. McVay LD, Carding SR. Extrathymic origin of human gamma delta T cells during fetal development. J Immunol. 1996;157(7):2873–82. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.157.7.2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bigby M, Markowitz JS, Bleicher PA, Grusby MJ, Simha S, Siebrecht M, et al. Most gamma delta T cells develop normally in the absence of MHC class II molecules. J Immunol. 1993;151(9):4465–75. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.151.9.4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Deseke M, Prinz I. Ligand recognition by the γδ TCR and discrimination between homeostasis and stress conditions. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(9):914–24. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0503-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Mokuno Y, Matsuguchi T, Takano M, Nishimura H, Washizu J, Ogawa T, et al. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 on gamma delta T cells bearing invariant V gamma 6/V delta 1 induced by Escherichia coli infection in mice. J Immunol. 2000;165(2):931–40. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Harly C, Joyce SP, Domblides C, Bachelet T, Pitard V, Mannat C, et al. Human γδ T cell sensing of AMPK-dependent metabolic tumor reprogramming through TCR recognition of EphA2. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(61):eaba9010. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aba9010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Choi H, Lee Y, Park SA, Lee JH, Park J, Park JH, et al. Human allogenic γδ T cells kill patient-derived glioblastoma cells expressing high levels of DNAM-1 ligands. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11(1):2138152. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2022.2138152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. El-Gazzar A, Groh V, Spies T. Immunobiology and conflicting roles of the human NKG2D lymphocyte receptor and its ligands in cancer. J Immunol. 2013;191(4):1509–15. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1301071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Niu C, Jin H, Li M, Xu J, Xu D, Hu J, et al. In vitro analysis of the proliferative capacity and cytotoxic effects of ex vivo induced natural killer cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and gamma-delta T cells. BMC Immunol. 2015;16(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12865-015-0124-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Almeida AR, Correia DV, Fernandes-Platzgummer A, da Silva CL, da Silva MG, Anjos DR, et al. Delta one T cells for immunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical-grade expansion/differentiation and preclinical proof of concept. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(23):5795–804. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Knight A, MacKinnon S, Lowdell MW. Human Vdelta1 gamma-delta T cells exert potent specific cytotoxicity against primary multiple myeloma cells. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(9):1110–8. doi:10.3109/14653249.2012.700766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Bruni E, Roberto A, Colombo FS, Villa A, et al. NKp46-expressing human gut-resident intraepithelial Vδ1 T cell subpopulation exhibits high antitumor activity against colorectal cancer. JCI Insight. 2019;4(24):e125884. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Davey MS, Willcox CR, Joyce SP, Ladell K, Kasatskaya SA, McLaren JE, et al. Clonal selection in the human Vδ1 T cell repertoire indicates γδ TCR-dependent adaptive immune surveillance. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14760. doi:10.1038/ncomms14760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ravens S, Schultze-Florey C, Raha S, Sandrock I, Drenker M, Oberdörfer L, et al. Human γδ T cells are quickly reconstituted after stem-cell transplantation and show adaptive clonal expansion in response to viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(4):393–401. doi:10.1038/ni.3686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Sandstrom A, Peigné CM, Léger A, Crooks JE, Konczak F, Gesnel MC, et al. The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Immunity. 2014;40(4):490–500. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Karunakaran MM, Subramanian H, Jin Y, Mohammed F, Kimmel B, Juraske C, et al. A distinct topology of BTN3A IgV and B30.2 domains controlled by juxtamembrane regions favors optimal human γδ T cell phosphoantigen sensing. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7617. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41938-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Herrmann T, Karunakaran MM. Butyrophilins: γδ T cell receptor ligands, immunomodulators and more. Front Immunol. 2022;13:876493. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.876493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Gober HJ, Kistowska M, Angman L, Jenö P, Mori L, De Libero G. Human T cell receptor gammadelta cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(2):163–8. doi:10.1084/jem.20021500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Mookerjee-Basu J, Vantourout P, Martinez LO, Perret B, Collet X, Périgaud C, et al. F1-adenosine triphosphatase displays properties characteristic of an antigen presentation molecule for Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6920–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0904024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Scotet E, Martinez LO, Grant E, Barbaras R, Jenö P, Guiraud M, et al. Tumor recognition following Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cell receptor interactions with a surface F1-ATPase-related structure and apolipoprotein A-I. Immunity. 2005;22(1):71–80. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Angelini DF, Borsellino G, Poupot M, Diamantini A, Poupot R, Bernardi G, et al. FcgammaRIII discriminates between 2 subsets of Vgamma9Vdelta2 effector cells with different responses and activation pathways. Blood. 2004;104(6):1801–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-01-0331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gertner-Dardenne J, Bonnafous C, Bezombes C, Capietto AH, Scaglione V, Ingoure S, et al. Bromohydrin pyrophosphate enhances antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity induced by therapeutic antibodies. Blood. 2009;113(20):4875–84. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-08-172296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Tokuyama H, Hagi T, Mattarollo SR, Morley J, Qiao W, So HF, et al. V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cell cytotoxicity against tumor cells is enhanced by monoclonal antibody drugs—rituximab and trastuzumab. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(11):2526–34. doi:10.1002/ijc.23365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Rancan C, Arias-Badia M, Dogra P, Chen B, Aran D, Yang H, et al. Exhausted intratumoral Vδ2–γδ T cells in human kidney cancer retain effector function. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(4):612–24. doi:10.1038/s41590-023-01448-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Rice MT, von Borstel A, Chevour P, Awad W, Howson LJ, Littler DR, et al. Recognition of the antigen-presenting molecule MR1 by a Vδ3(+) γδ T cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(49):e2110288118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110288118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Marlin R, Pappalardo A, Kaminski H, Willcox CR, Pitard V, Netzer S, et al. Sensing of cell stress by human γδ TCR-dependent recognition of annexin A2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(12):3163–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621052114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Le Nours J, Gherardin NA, Ramarathinam SH, Awad W, Wiede F, Gully BS, et al. A class of γδ T cell receptors recognize the underside of the antigen-presenting molecule MR1. Science. 2019;366(6472):1522–7. doi:10.1126/science.aav3900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Déchanet J, Merville P, Lim A, Retière C, Pitard V, Lafarge X, et al. Implication of γδ T cells in the human immune response to cytomegalovirus. J Clin Investig. 1999;103(10):1437–49. doi:10.1172/jci5409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kenna T, Golden-Mason L, Norris S, Hegarty JE, O’Farrelly C, Doherty DG. Distinct subpopulations of gamma delta T cells are present in normal and tumor-bearing human liver. Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):56–63. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Dunne MR, Elliott L, Hussey S, Mahmud N, Kelly J, Doherty DG, et al. Persistent changes in circulating and intestinal γδ T cell subsets, invariant natural killer T cells and mucosal-associated invariant T cells in children and adults with coeliac disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76008. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang J, Lin C, Li H, Li R, Wu Y, Liu H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating γδT cells predict prognosis and adjuvant chemotherapeutic benefit in patients with gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(11):e1353858. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2017.1353858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Meraviglia S, Presti EL, Tosolini M, Mendola CL, Orlando V, Todaro M, et al. Distinctive features of tumor-infiltrating γδ T lymphocytes in human colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(10):e1347742. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2017.1347742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Liu Y, Zhang C. The role of human γδ T cells in anti-tumor immunity and their potential for cancer immunotherapy. Cells. 2020;9(5):1206. doi:10.3390/cells9051206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Devilder MC, Maillet S, Bouyge-Moreau I, Donnadieu E, Bonneville M, Scotet E. Potentiation of antigen-stimulated V gamma 9V delta 2 T cell cytokine production by immature dendritic cells (DC) and reciprocal effect on DC maturation. J Immunol. 2006;176(3):1386–93. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Sedlak C, Patzl M, Saalmüller A, Gerner W. IL-12 and IL-18 induce interferon-γ production and de novo CD2 expression in porcine γδ T cells. Dev Comp Immunol. 2014;47(1):115–22. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2014.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Feurle J, Weissinger F, Tony HP, Wilhelm M. Stimulation of gammadelta T cells by aminobisphosphonates and induction of antiplasma cell activity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;96(2):384–92. doi:10.1182/blood.v96.2.384.013k07_384_392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Mattarollo SR, Kenna T, Mie N, Nicol AJ. Chemotherapy and zoledronate sensitize solid tumour cells to Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(8):1285–97. doi:10.1007/s00262-007-0279-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ponomarev ED, Dittel BN. Gamma delta T cells regulate the extent and duration of inflammation in the central nervous system by a Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4678–87. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Brandes M, Willimann K, Bioley G, Lévy N, Eberl M, Luo M, et al. Cross-presenting human gammadelta T cells induce robust CD8+ alphabeta T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(7):2307–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810059106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ribot JC, Lopes N, Silva-Santos B. γδ T cells in tissue physiology and surveillance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(4):221–32. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00452-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Andrea AE, Chiron A, Mallah S, Bessoles S, Sarrabayrouse G, Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Advances in CAR-T cell genetic engineering strategies to overcome hurdles in solid tumors treatment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:830292. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.830292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Castro CD, Boughter CT, Broughton AE, Ramesh A, Adams EJ. Diversity in recognition and function of human γδ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2020;298(1):134–52. doi:10.1111/imr.12930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Willcox CR, Mohammed F, Willcox BE. The distinct MHC-unrestricted immunobiology of innate-like and adaptive-like human γδ T cell subsets-nature’s CAR-T cells. Immunol Rev. 2020;298(1):25–46. doi:10.1111/imr.12928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Lee BW, Kwon EJ, Ju JH. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases: current insights and future prospects. J Rheum Dis. 2025;32(3):154–65. doi:10.4078/jrd.2024.0122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Kang N, Tang L, Li X, Wu D, Li W, Chen X, et al. Identification and characterization of Foxp3+ γδ T cells in mouse and human. Immunol Lett. 2009;125(2):105–13. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2009.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Sun D, Ko MK, Shao H, Kaplan HJ. Augmented Th17-stimulating activity of BMDCs as a result of reciprocal interaction between γδ and dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2021;134:13–24. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2021.02.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Moser T, Akgün K, Proschmann U, Sellner J, Ziemssen T. The role of TH17 cells in multiple sclerosis: therapeutic implications. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(10):102647. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Faust HJ, Zhang H, Han J, Wolf MT, Jeon OH, Sadtler K, et al. IL-17 and immunologically induced senescence regulate response to injury in osteoarthritis. J Clin Investig. 2020;130(10):5493–507. doi:10.1172/JCI134091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Monteiro A, Cruto C, Rosado P, Martinho A, Rosado L, Fonseca M, et al. Characterization of circulating gamma-delta T cells in relapsing vs remission multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2018;318(1):65–71. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Blache U, Tretbar S, Koehl U, Mougiakakos D, Fricke S. CAR T cells for treating autoimmune diseases. RMD. 2023;9(4):e002907. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Kansal R, Richardson N, Neeli I, Khawaja S, Chamberlain D, Ghani M, et al. Sustained B cell depletion by CD19-targeted CAR T cells is a highly effective treatment for murine lupus. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(482):eaav1648. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Mackensen A, Müller F, Mougiakakos D, Böltz S, Wilhelm A, Aigner M, et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2124–32. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02017-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Müller F, Boeltz S, Knitza J, Aigner M, Völkl S, Kharboutli S, et al. CD19-targeted CAR T cells in refractory antisynthetase syndrome. Lancet. 2023;401(10379):815–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00023-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Rizzo C, La Barbera L, Lo Pizzo M, Ciccia F, Sireci G, Guggino G. Invariant NKT cells and rheumatic disease: focus on primary sjogren syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5435. doi:10.3390/ijms20215435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Dossybayeva K, Zhubanova G, Mussayeva A, Mukusheva Z, Dildabayeva A, Nauryzbayeva G, et al. Nonspecific increase of αβTCR(+) double-negative T cells in pediatric rheumatic diseases. World J Pediatr. 2024;20(12):1283–92. doi:10.1007/s12519-024-00854-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Capsomidis A, Benthall G, Van Acker HH, Fisher J, Kramer AM, Abeln Z, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered human gamma delta T cells: enhanced cytotoxicity with retention of cross presentation. Mol Ther. 2018;26(2):354–65. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Sánchez Martínez D, Tirado N, Mensurado S, Martínez-Moreno A, Romecín P, Gutiérrez Agüera F, et al. Generation and proof-of-concept for allogeneic CD123 CAR-Delta One T (DOT) cells in acute myeloid leukemia. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(9):e005400. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-005400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Makkouk A, Yang XC, Barca T, Lucas A, Turkoz M, Wong JTS, et al. Off-the-shelf Vδ1 gamma delta T cells engineered with glypican-3 (GPC-3)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) and soluble IL-15 display robust antitumor efficacy against hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(12):e003441. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-003441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Ferry GM, Agbuduwe C, Forrester M, Dunlop S, Chester K, Fisher J, et al. A simple and robust single-step method for CAR-Vδ1 γδT cell expansion and transduction for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:863155. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.863155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Wang R, Wen Q, He W, Yang J, Zhou C, Xiong W, et al. Optimized protocols for γδ T cell expansion and lentiviral transduction. Mol Med Report. 2019;19(3):1471–80. [Google Scholar]

74. Nishimoto KP, Barca T, Azameera A, Makkouk A, Romero JM, Bai L, et al. Allogeneic CD20-targeted γδ T cells exhibit innate and adaptive antitumor activities in preclinical B-cell lymphoma models. Clin Transl Immunol. 2022;11(2):e1373. doi:10.1002/cti2.1373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Deniger DC, Switzer K, Mi T, Maiti S, Hurton L, Singh H, et al. Bispecific T-cells expressing polyclonal repertoire of endogenous γδ T-cell receptors and introduced CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Mol Ther. 2013;21(3):638–47. doi:10.1038/mt.2012.267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Schamel WW, Zintchenko M, Nguyen T, Fehse B, Briquez PS, Minguet S. The potential of γδ CAR and TRuC T cells: an unearthed treasure. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54(11):2451074. doi:10.1002/eji.202451074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Frieling JS, Tordesillas L, Bustos XE, Ramello MC, Bishop RT, Cianne JE, et al. γδ-Enriched CAR-T cell therapy for bone metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Adv. 2023;9(18):eadf0108. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf0108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Harrer DC, Simon B, Fujii SI, Shimizu K, Uslu U, Schuler G, et al. RNA-transfection of γ/δ T cells with a chimeric antigen receptor or an α/β T-cell receptor: a safer alternative to genetically engineered α/β T cells for the immunotherapy of melanoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):551. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3539-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Fleischer LC, Becker SA, Ryan RE, Fedanov A, Doering CB, Spencer HT. Non-signaling chimeric antigen receptors enhance antigen-directed killing by γδ T cells in contrast to αβ T cells. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;18:149–60. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2020.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Lee D, Dunn ZS, Guo W, Rosenthal CJ, Penn NE, Yu Y, et al. Unlocking the potential of allogeneic Vδ2 T cells for ovarian cancer therapy through CD16 biomarker selection and CAR/IL-15 engineering. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6942. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42619-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Li HK, Wu TS, Kuo YC, Hsiao CW, Yang HP, Lee CY, et al. A novel allogeneic rituximab-conjugated gamma delta T cell therapy for the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma. Cancers. 2023;15(19):4844. doi:10.3390/cancers15194844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Song HW, Benzaoui M, Dwivedi A, Underwood S, Shao L, Achar S, et al. Manufacture of CD22 CAR T cells following positive versus negative selection results in distinct cytokine secretion profiles and γδ T cell output. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2023;32(1):101171. doi:10.1016/j.omtm.2023.101171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Branella GM, Lee JY, Okalova J, Parwani KK, Alexander JS, Arthuzo RF, et al. Ligand-based targeting of c-kit using engineered γδ T cells as a strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1294555. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1294555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Li C, Zhou F, Wang J, Chang Q, Du M, Luo W, et al. Novel CD19-specific γ/δ TCR-T cells in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):5. doi:10.1186/s13045-023-01402-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Juraske C, Krissmer SM, Teuber ES, Parigiani MA, Strietz J, Wesch D, et al. Reprogramming of human γδ T cells by expression of an anti-CD19 TCR fusion construct (εTRuC) to enhance tumor killing. J Leukoc Biol. 2024;115(2):293–305. doi:10.1093/jleuko/qiad128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Becker SA, Petrich BG, Yu B, Knight KA, Brown HC, Raikar SS, et al. Enhancing the effectiveness of γδ T cells by mRNA transfection of chimeric antigen receptors or bispecific T cell engagers. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2023;29:145–57. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2023.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]