Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mistletoe Lectin Overcomes Macrophage-Mediated Chemo-Resistance in 3D Co-Culture Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

1 Department of Pharmacy; Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

2 Smart Beautytech Research Institute, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

3 Research Institute of Life and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 57922, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Su-Yun Lyu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural Product-Based Anticancer Drug Discovery)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 11 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.075574

Received 04 November 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Objective: Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) contribute to chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), yet strategies to reprogram TAMs while enhancing chemotherapy efficacy remain limited. This study investigated whether Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin (VCA) could sensitize TNBC cells to doxorubicin (DOX) and modulate TAM-mediated chemoresistance in three-dimensional (3D) co-culture models. Methods: MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells were co-cultured with RAW264.7 macrophages in collagen-embedded 3D spheroids. Spheroid viability was assessed using an ATP-based luminescent assay. Cytokine secretion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers were measured using ELISA and Western blotting. Drug synergy was evaluated using combination index (CI) calculations. Results: VCA-DOX combination demonstrated synergistic cytotoxicity exclusively in co-culture spheroids (CI = 0.72), reducing viability to 25.9% (p < 0.001), while showing no synergy in monoculture (CI = 1.52). Combination treatment decreased VEGF secretion by 49% and IL-6 by 74%, while elevating TNF-α 2.7-fold, suggesting macrophage reprogramming. VCA enhanced E-cadherin expression while suppressing mesenchymal markers in co-culture spheroids and reduced Matrigel invasion by 60% (p < 0.001). Conclusion: VCA-DOX combination demonstrates synergistic anticancer effects through TAM reprogramming and enhanced chemosensitization specifically in 3D co-culture models, warranting further investigation for overcoming macrophage-mediated chemoresistance in TNBC.Keywords

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), defined by a lack of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, accounts for 15%–20% of breast malignancies and demonstrates aggressive tumor behavior, higher metastatic potential, and poorer prognosis compared to other breast cancer subtypes [1,2]. TNBC patients experience elevated recurrence and mortality following surgical resection, demonstrating five-year survival at 65% in regional disease and merely 11% after distant metastasis [3]. Due to the lack of targeted receptors, chemotherapy remains the standard treatment for TNBC, with doxorubicin (DOX) being an effective anthracycline chemotherapy agent widely used in breast cancer treatment. Nevertheless, treatment failure occurs in some patients due to DOX resistance and cardiotoxic effects [4]. The tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), plays a critical role in TNBC therapeutic resistance [5]. TAMs secrete various cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which activate the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathways, contributing to immune evasion and therapeutic resistance in TNBC [6]. Natural products have emerged as potential candidates for combination therapy to overcome drug resistance, with various plant-derived compounds demonstrating the ability to enhance chemosensitivity, induce apoptosis, and modulate immune responses in breast cancer cells [7,8].

TAMs are the most abundant immune cells in breast cancer, constituting approximately 50% of the tumor mass and playing a critical role in malignant breast cancer aggressiveness [9]. In the tumor microenvironment, macrophages acquire diverse functional states through interactions with cancer cells, exhibiting both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory characteristics that promote tumor progression through angiogenesis and invasion [9]. In TNBC specifically, tumor cells educate primary monocytes through the secretion of various factors, such as monocyte colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), generating TAMs displaying distinct phenotypes expressing mixed inflammatory markers [10]. These tumor-educated macrophages secrete both anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 and tumor-promoting factors, like IL-6 and TNF-α, which collectively contribute to the aggressive behavior of TNBC cells [10]. High macrophage infiltration correlates with unfavorable prognostic features, including high histological grade, negative estrogen receptor expression, and elevated Ki-67 proliferation index in breast cancer [11]. Given the crucial role of TAMs in tumor progression and drug resistance, targeting tumor-macrophage interactions is a potential therapeutic approach to enhance chemotherapy efficacy in TNBC treatment. However, despite extensive characterization of TAM-mediated resistance, few studies have explored natural products that simultaneously modulate TAM phenotype and enhance chemotherapy efficacy.

Based on these findings, strategies targeting tumor-macrophage interactions have emerged as potential therapeutic approaches. Viscum album L. (European mistletoe) extracts, containing bioactive compounds including lectins, viscotoxins, and triterpene acids, have demonstrated both direct cytotoxic effects on cancer cells and immunomodulatory properties [12,13]. Korean mistletoe lectin (V. album L. var. coloratum agglutinin, VCA) induces apoptosis in tumor cells through activation of caspases [14], and clinical studies have shown that combining V. album with conventional therapy reduced treatment discontinuation by 70% [15]. V. album preparations are widely utilized in integrative oncology, with up to 63% of cancer patients in German-speaking European countries receiving mistletoe therapy [15]. The immunomodulatory effects include activation of natural killer cells and macrophages, contributing to enhanced host defense against tumors [16,17]. Systematic reviews have confirmed that V. album therapy improves health-related quality of life and reduces chemotherapy-induced adverse events [18]. To investigate the mechanisms underlying these effects, RAW264.7 macrophages have been established as a standard model for studying tumor-macrophage interactions, as they acquire TAM-like properties when co-cultured with breast cancer cells [19]. Studies have shown that tumor-educated macrophages exhibit enhanced secretion of pro-tumoral factors, including OSM and IL-6 [20]. Additionally, three-dimensional (3D) culture models more accurately recapitulate the TME compared to two-dimensional (2D) cultures, demonstrating altered drug sensitivity patterns [21,22]. Therefore, we investigated whether VCA could overcome DOX resistance in TNBC by modulating tumor-macrophage interactions using RAW264.7 and MDA-MB-231 co-culture models in 3D collagen-embedded spheroid systems.

While previous studies have shown that VCA can affect macrophage function and cancer cell viability, the specific mechanism by which VCA modulates these interactions in 3D tumor microenvironments remains incompletely defined. Most studies investigating TAM-mediated drug resistance have relied on 2D culture systems, which fail to capture the complex spatial organization and cell-matrix interplay affecting drug sensitivity in vivo. In this study, we employed 3D collagen-embedded spheroid models to elucidate the functional changes in tumor-associated macrophages upon VCA treatment. We hypothesized that VCA treatment would enhance DOX efficacy by altering macrophage-cancer cell interactions in 3D spheroid models where cell-cell and cell-matrix interplay more accurately mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment. Specifically, we investigated whether VCA could modulate macrophage cytokine secretion patterns (IL-6, TNF-α) to reverse their tumor-protective effects and inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes.

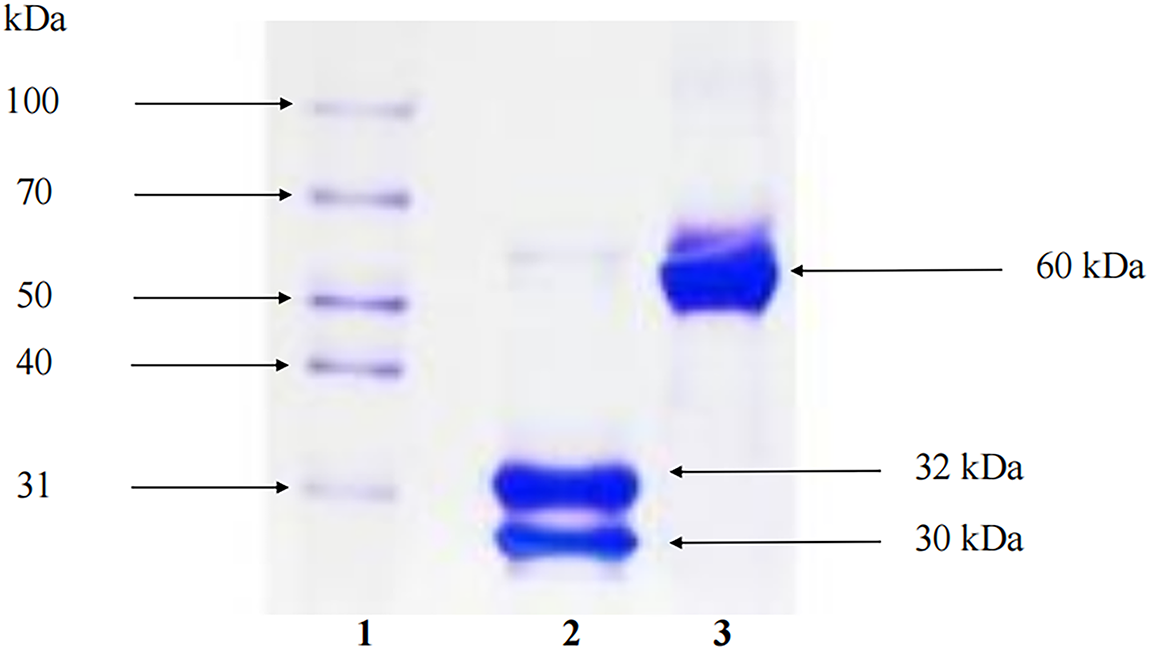

2.1 Cell Culture and Reagents Purification of VCA

VCA was isolated and purified from Korean mistletoe following our previously established protocols [23–25]. Briefly, Korean mistletoe harvested from oak trees in Kangwon-do, Korea, was processed using sequential cation exchange chromatography (SP Sephadex C-50; Cytiva, 17-0720-01, Marlborough, MA, USA) and affinity chromatography (asialofetuin-Sepharose 4B; 17-0120-01, Cytiva). The purified lectin was concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-15; UFC901024, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (500-0006, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The purity and biological activity of VCA used in this study were confirmed to be consistent with our previous reports (Fig. A1) [24,26,27]. Endotoxin contamination was assessed using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) Chromogenic Endpoint Assay (QCL-1000; 50-647U, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) and confirmed to be below the detection limit (<0.1 EU/mL).

2.2 Cell Culture and Maintenance

MDA-MB-231 human triple-negative breast cancer cells and RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; 11965-092, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; 16000-044, Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (15140-122, Gibco). RAW264.7 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Both cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. MDA-MB-231 cells were subcultured every 3–4 days when reaching 70%–80% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; 25200-056, Gibco) for 3–5 min at 37°C. RAW264.7 cells, being semi-adherent, were subcultured every 2–3 days by scraping using a cell scraper followed by centrifugation at 300× g for 5 min. Cell viability was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion method with 0.4% trypan blue solution (T8154, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a hemocytometer, and only cell preparations with >95% viability were used for experiments. Both cell lines were authenticated by Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling at the Korean Cell Line Bank, and mycoplasma contamination was tested monthly using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (LT07-318, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). All experiments were performed using cells between passages 5–20 for MDA-MB-231 and passages 5–15 for RAW264.7 to ensure consistency.

2.3 3D Spheroid Formation and Co-Culture

Three-dimensional spheroids were generated using a collagen matrix embedding protocol. MDA-MB-231 cells were harvested from T75 flasks at 70%–80% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA treatment for 3 min at 37°C. After neutralization with complete medium containing 10% FBS, cells were centrifuged at 300× g for 5 min and resuspended in fresh DMEM to achieve a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL.

For monoculture spheroids, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in ultra-low attachment 96-well round-bottom plates (3474, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in 100 μL of complete medium. For co-culture spheroids, MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 103 cells) were mixed with RAW264.7 macrophages (2.5 × 103 cells) by pipetting in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube to achieve a homogeneous 2:1 ratio before seeding. The cell suspension was then transferred to the wells, and the plates were centrifuged at 200× g for 3 min to promote initial cell aggregation at the well bottom.

After 24 h of initial spheroid formation at 37°C with 5% CO2, rat tail collagen type I (354236, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was prepared on ice. The stock collagen solution was diluted to 3 mg/mL using ice-cold 10× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10% v/v), 1 N NaOH to adjust pH to 7.4 (confirmed with pH strips), and ice-cold serum-free DMEM. Fifty microliters of the neutralized collagen solution was added to each well using a positive displacement pipette to minimize air bubble formation. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min without disturbance to allow collagen polymerization, which was confirmed by the transition from transparent to opaque appearance. Following polymerization, 100 μL of fresh complete medium was added along the well wall to avoid disrupting the collagen matrix. Spheroids were maintained for 3–4 days with daily half-volume medium changes to minimize mechanical disruption. Spheroid morphology, size, and integrity were monitored daily using an inverted phase-contrast microscope (IX71, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and only spheroids with diameters between 400–500 μm were selected for subsequent experiments.

Spheroid morphometric parameters, including projected area, integrated density, and roundness, were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54f, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Projected area was measured by manually outlining the spheroid boundary, and values were normalized to Day 0 (set as 100%). Integrated density was calculated as the product of area and mean gray value. Roundness was calculated as 4 × area/(π × major axis2), with values approaching 1.0 indicating a perfect circle.

2.4 Cell Tracker Staining for Co-Culture Visualization

To visualize the spatial distribution and organization of different cell types within co-culture spheroids, cells were pre-labeled with fluorescent dyes before spheroid formation. MDA-MB-231 cells were stained with CellTracker Green 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA; C7025, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and RAW264.7 cells with CellTracker Red chloromethyl tetramethylrhodamine (CMTPX; C34552, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells at 70%–80% confluence were washed twice with 1× PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated with 5 μM of the respective dyes diluted in serum-free DMEM for 30 min at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were washed three times with pre-warmed PBS to remove excess dye and allowed to recover in complete medium for 30 min to ensure dye retention and cell viability.

Labeled cells were then harvested and used immediately for spheroid formation. Fluorescently labeled spheroids were imaged using a Nikon fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at days 1, 2, 3, and 4 post-seeding. Green fluorescence (MDA-MB-231 cells) was visualized using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter set, and red fluorescence (RAW264.7 cells) using a tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) filter set. Multiple images at different focal planes were captured manually through the spheroid depth at approximately 20–30 μm intervals. Images were processed and merged using Nikon Imaging Software (NIS)-Elements software (version 5.21.00, Nikon Corporation) to create composite images showing the distribution pattern of both cell types within the spheroids.

Colocalization analysis [28] was performed using the JACoP (Just Another Co-localization Plugin) plugin in ImageJ software (version 1.54f, NIH). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) was calculated to assess the linear relationship between fluorescence intensities of the two channels. Manders’ coefficients (M1 and M2) were used to quantify the fraction of overlapping pixels, where M1 represents the fraction of RAW264.7 signal overlapping with MDA-MB-231, and M2 represents the fraction of MDA-MB-231 signal overlapping with RAW264.7. Costes’ automatic threshold method was applied to objectively determine background threshold values for colocalization analysis. Van Steensel’s cross-correlation function was used to verify spatial alignment by calculating cross-correlation coefficients at various pixel shifts, with maximum correlation at zero shift (dx = 0) indicating true colocalization. Colocalization masks were generated to visualize regions of spatial overlap between the two cell populations.

MDA-MB-231 spheroids were treated after 4 days of culture when they reached optimal size and structural integrity. Concentration ranges for dose-response studies were VCA (0–10 μg/mL) and DOX (0–30 μg/mL), based on the higher drug concentrations required in 3D spheroid models due to limited penetration [29,30]. Dose-response experiments revealed differential drug sensitivity: at VCA 5 μg/mL, RAW264.7 retained 51% viability while MDA-MB-231 retained 82%; at VCA 10 μg/mL, RAW264.7 viability dropped to 21%. For combination studies, sub-cytotoxic concentrations (VCA 1–5 μg/mL, DOX 5–10 μg/mL) were selected to maintain macrophage viability (>50%) while enabling detection of synergistic effects in the co-culture system. Treatment groups included: (1) vehicle control (1× PBS, pH 7.4), (2) DOX (D1515, Sigma-Aldrich) at 20 μg/mL, (3) VCA at 10 μg/mL, and (4) combination of DOX (20 μg/mL) and VCA (10 μg/mL). Stock solutions were prepared fresh: DOX was dissolved in sterile water at 2 mg/mL and VCA in PBS at 1 mg/mL, both stored at 4°C and used within one week. Working dilutions were prepared immediately before use in complete medium. Drug-containing medium (150 μL per well) was replaced every 24 h during the 48-h treatment period to maintain consistent drug concentrations. All treatments were performed in triplicate wells, and experiments were repeated at least three times independently.

Cell viability was quantified using the CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay (G9681, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), which measures adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content as an indicator of metabolically active cells. This assay was chosen for its penetration capability into 3D structures compared to traditional tetrazolium-based assays. Following 48 h of drug treatment, spheroids were transferred using a wide-bore pipette tip to opaque-walled 96-well plates containing 100 μL of fresh phenol red-free medium. An equal volume of CellTiter-Glo 3D reagent was added to each well, and plates were placed on an orbital shaker (Orbital Shaker SO1, Stuart, Staffordshire, UK; orbital diameter 16 mm) at 200 rpm for 5 min at room temperature to induce cell lysis. Plates were then incubated at room temperature for an additional 25 min to stabilize the luminescent signal. Luminescence was measured using a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an integration time of 0.5 s per well. Cell viability was calculated as a percentage relative to vehicle control: % viability = (luminescence of treated spheroid/luminescence of control spheroid) × 100. Background luminescence from wells containing medium only was subtracted from all readings.

Spheroid viability and spatial distribution of cell death were visualized using the LIVE/DEAD Cell Imaging Kit (L3224, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Spheroids were washed once with PBS (1×, pH 7.4) and incubated with 2 μM calcein acetoxymethyl (AM; C3100MP, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (E1169, Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in PBS for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. After incubation, spheroids were washed twice with PBS and transferred to glass-bottom dishes for imaging. Fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon Corporation) equipped with appropriate filter sets. Live cells (green fluorescence) were detected using a FITC filter (excitation 488 nm/emission 530 nm), and dead cells (red fluorescence) using a TRITC filter (excitation 530 nm/emission 645 nm). Multiple focal planes were manually captured through the spheroid depth at 20 μm intervals using the microscope’s z-axis control. Images were processed and merged using NIS-Elements software (Nikon Corporation) to create composite images showing the distribution of viable and dead cells throughout the spheroid structure.

Cytokine secretion was quantified as markers of angiogenic potential and macrophage functional status using human VEGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (DVE00, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), human IL-6 ELISA kit (D6050, R&D Systems), and human TNF-α ELISA kit (DTA00C, R&D Systems). Culture supernatants were collected after 48 h of treatment, centrifuged at 1000× g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris, and stored at −80°C until analysis. ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, 100 μL of sample or standard was added to pre-coated wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the detection antibody was added for 2 h, followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 20 min. Substrate solution was added, and color development was stopped after 20 min. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with wavelength correction at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Cytokine concentrations were calculated from the standard curves and expressed as pg/mL. All samples were analyzed in duplicate.

Spheroids (20–30 per condition) were collected, washed twice with ice-cold PBS (1×, pH 7.4), and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (89901, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (11836170001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Spheroids were mechanically disrupted by pipetting and sonication (3 × 10 s on ice, Branson Sonifier 450, Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT, USA), followed by centrifugation at 14,000× g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (23225, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were denatured in Laemmli sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min, separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (1620177, Bio-Rad) using a semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: anti-vimentin (5741, 1:1000), anti-β-catenin (8480, 1:1000), anti-E-cadherin (3195, 1:1000), anti-N-cadherin (13116, 1:1000), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 5174, 1:5000) as loading control (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (7074, 1:5000, Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL; RPN2106, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and imaged using a ChemiDoc system (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (version 1.54f, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) and normalized to GAPDH.

The invasive capacity of spheroids was assessed using the Cultrex 3D Spheroid Cell Invasion Assay (3500-096-K, R&D Systems). Pre-formed spheroids were transferred to a 96-well plate containing 50 μL of invasion matrix (basement membrane extract diluted 1:1 with serum-free medium) per well. An additional 50 μL of invasion matrix was overlaid on top of the spheroids, and plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h to allow matrix polymerization. Complete medium (100 μL) containing treatments was then added on top of the matrix. Spheroid invasion was monitored daily for 72 h using an inverted phase-contrast microscope. Images were captured at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post-embedding. The invasion area was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54f, NIH) by measuring the total area covered by invading cells and subtracting the original spheroid core area. Invasion index was calculated as: (invasion area at time point − original spheroid area)/original spheroid area × 100.

All experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates, each containing three technical replicates. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Normal distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For comparisons between two groups, the unpaired Student’s t-test was used. For multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was performed. Each cytokine (VEGF, IL-6, TNF-α) was analyzed as an independent endpoint; no additional correction for multiple hypothesis testing was applied across cytokine panels, as each represents a distinct biological outcome. For analysis of drug combination effects, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was used. Drug combination effects were evaluated using the combination index (CI) method as described by Chou [31], where CI < 1 indicates synergy, CI = 1 indicates an additive effect, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

3.1 Establishment and Characterization of 3D Tumor-Macrophage Co-Culture Spheroids

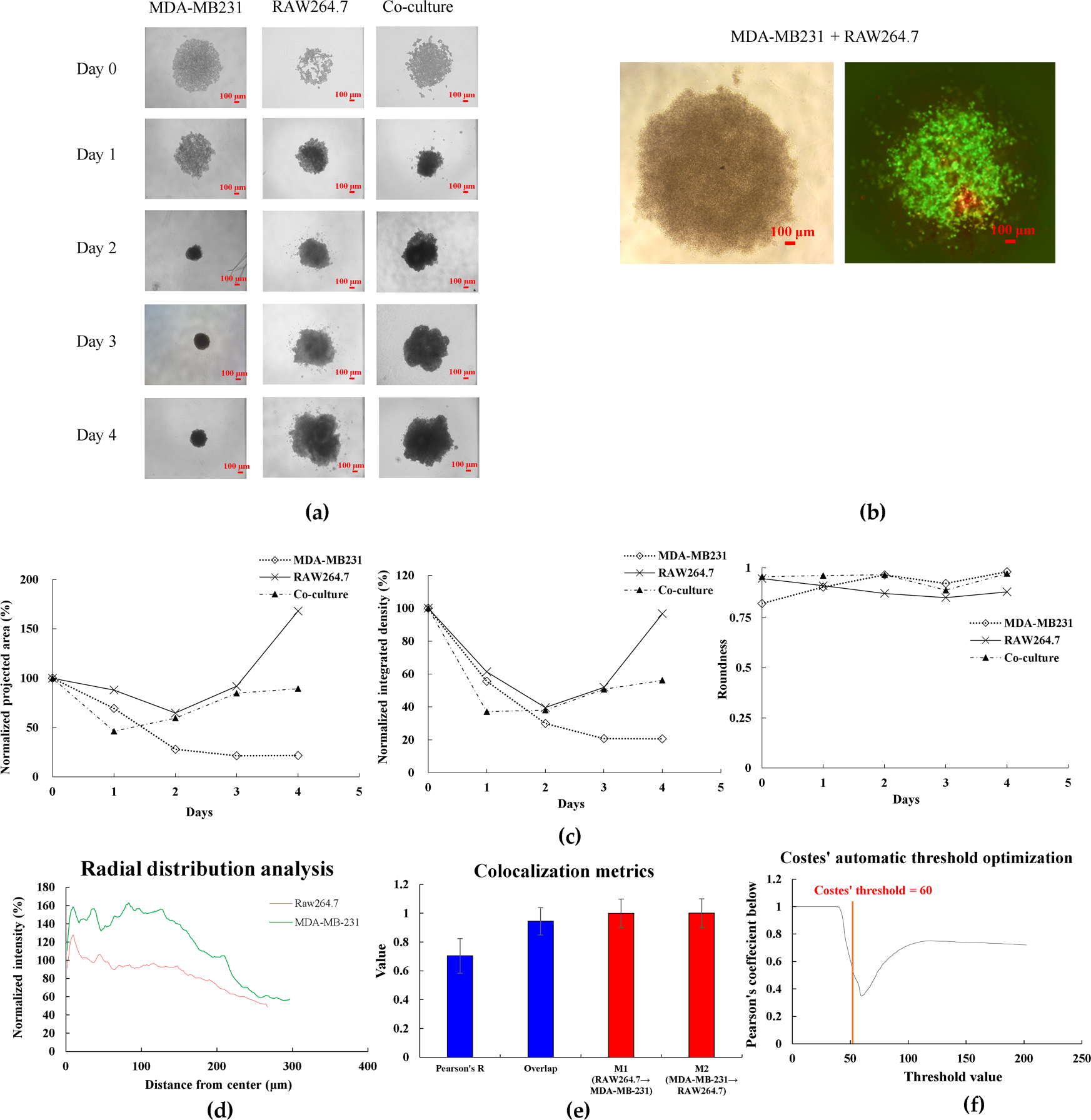

To investigate tumor-macrophage interactions in a physiologically relevant model, we established 3D spheroids using MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells alone or in co-culture with RAW264.7 macrophages embedded in collagen matrix. Phase-contrast microscopy revealed morphological changes over 4 days of culture (Fig. 1a). MDA-MB-231 monoculture spheroids underwent progressive compaction, with normalized projected area decreasing from 100% at day 0% to 21.8% by day 4, while maintaining high roundness (0.98), indicating formation of tightly packed spheroids. In contrast, RAW264.7 monoculture spheroids showed expansion to 168% of the initial area by day 4. Co-culture spheroids containing both cell types (2:1 ratio) displayed intermediate behavior, reaching 89.4% normalized area at day 4 with consistently high roundness (0.971) (Fig. 1c). To visualize cell distribution within co-culture spheroids, MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-labeled with CellTracker Green and RAW264.7 cells with CellTracker Red. Fluorescence microscopy at day 4 revealed uniform intermixing of both cell types throughout the spheroid structure, with no segregation into distinct regions (Fig. 1b). This homogeneous distribution indicates stable cell-cell interactions between cancer cells and macrophages within the 3D architecture.

Figure 1: Characterization of 3D spheroid formation and growth. (a) Brightfield images of MDA-MB231, RAW264.7, and co-culture spheroids from Day 0 to Day 4 showing morphological changes and compaction. (b) Fluorescent staining of co-culture spheroids at Day 4 showing spatial distribution of MDA-MB231 cells (green) and RAW264.7 macrophages (red). (c) Quantitative analysis of spheroid characteristics: normalized projected area (%), integrated density (%), and roundness from Day 0 to Day 4. (d) Radial distribution profiles showing normalized fluorescence intensity of MDA-MB-231 cells and RAW264.7 macrophages from spheroid center to periphery, analyzed using ImageJ software. (e) Quantitative colocalization metrics from 3D co-culture spheroids. Data shows Pearson’s correlation coefficient, overlap coefficient, and Manders’ coefficients (M1: fraction of RAW264.7 overlapping with MDA-MB-231; M2: fraction of MDA-MB-231 overlapping with RAW264.7). Data represent mean ± SD from n = 3 independent spheroids. (f) Costes’ automatic threshold optimization for colocalization analysis. The vertical red line indicates the automatically determined optimal threshold value (60), where Pearson’s coefficient below the threshold reaches its minimum. (g) Van Steensel’s cross-correlation function analysis showing maximum correlation at zero pixel shift (dx = 0), confirming near-complete spatial alignment between RAW264.7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. (h) Costes’ mask visualization of colocalized regions. White areas indicate regions where both cell types are present, demonstrating successful intermixing throughout the spheroid. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Scale bar: 100 μm for all images

To quantitatively assess the spatial distribution of cells within the spheroids, we performed comprehensive image analysis using ImageJ software. Radial profile analysis revealed that MDA-MB-231 cancer cells formed the main body of spheroids with higher intensity in the core region, while RAW264.7 macrophages were distributed throughout the spheroid at relatively consistent levels, suggesting successful infiltration and intermixing of macrophages within the tumor spheroid (Fig. 1d). Colocalization analysis demonstrated strong spatial association between the two cell types (Pearson’s R = 0.705 ± 0.08, n = 3), with nearly complete overlap as indicated by Manders’ coefficients (M1 = 0.999 ± 0.05, M2 = 1.000 ± 0.05), confirming the intermixed nature of the co-culture spheroids (Fig. 1e). The automatic threshold optimization using Costes’ method validated our analysis approach (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, Van Steensel’s cross-correlation analysis showed maximum correlation (0.705) at zero pixel shift, indicating near-complete spatial alignment between the two cell types (Fig. 1g). Visual confirmation through colocalization masking further supported these quantitative findings (Fig. 1h).

3.2 VCA and DOX Combination Shows Synergistic Cytotoxicity Specifically in Co-Culture Spheroids

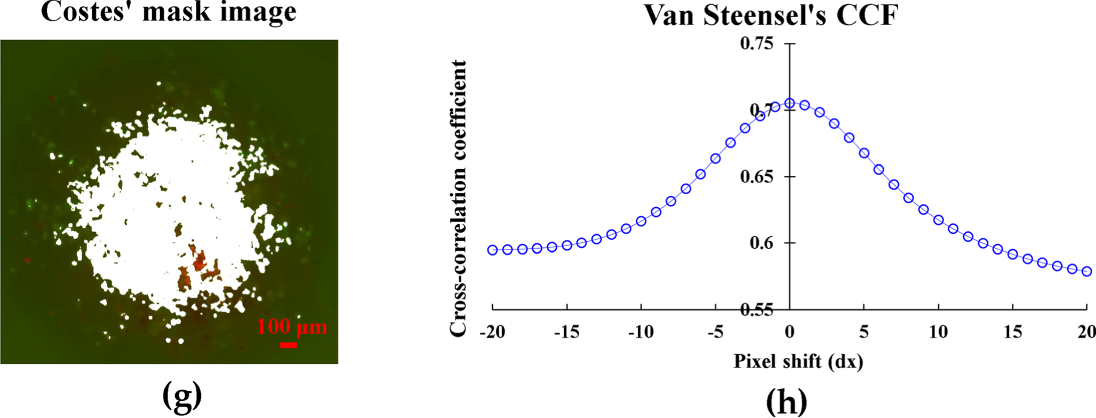

Dose-response analysis revealed differential drug sensitivity between monoculture and co-culture spheroids. VCA treatment (1–10 μg/mL) showed minimal cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 monoculture spheroids (64.5% viability at 10 μg/mL) but reduced viability in co-culture spheroids at concentrations ≥5 μg/mL (36.1% viability at 5 μg/mL, p < 0.01 vs. control) (Fig. 2a). DOX treatment (1–30 μg/mL) moderately reduced viability in both systems, with co-culture spheroids showing enhanced sensitivity at higher concentrations (66.2% viability at 20 μg/mL, p < 0.05 vs. control) (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2: Cell viability assessment in 3D spheroid cultures. (a,b) Dose-response curves of (a) VCA and (b) DOX treatment for 48 h. (c) Combination treatment effects of VCA and DOX. (d) Representative live/dead staining images of spheroids after treatment with VCA (5 μg/mL), DOX (10 μg/mL), or combination for 48 h. Green indicates live cells (calcein-AM) and red indicates dead cells (ethidium homodimer-1). (e) Quantification of live/dead staining showing the percentage of live and dead cells in MDA-MB-231 monoculture, RAW264.7 monoculture, and co-culture spheroids following each treatment. Scale bar = 100 μm. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to untreated control (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test)

Combination treatment revealed different responses between spheroid types. In MDA-MB-231 monoculture, VCA (5 μg/mL) plus DOX (10 μg/mL) showed no enhanced effect compared to single agents (83.8% viability, CI = 1.52). However, the same combination in co-culture spheroids resulted in cytotoxicity (25.9% viability, p < 0.001 vs. control), with a CI value of 0.72 indicating moderate synergistic interaction (Fig. 2c). Live/Dead staining confirmed these findings: control co-culture spheroids showed predominantly live cells (green), while combination treatment resulted in extensive cell death (red), with quantification revealing 74% dead cells in co-culture, 58% in RAW264.7 alone, vs. only 16% in monoculture following combination treatment (Fig. 2d,e).

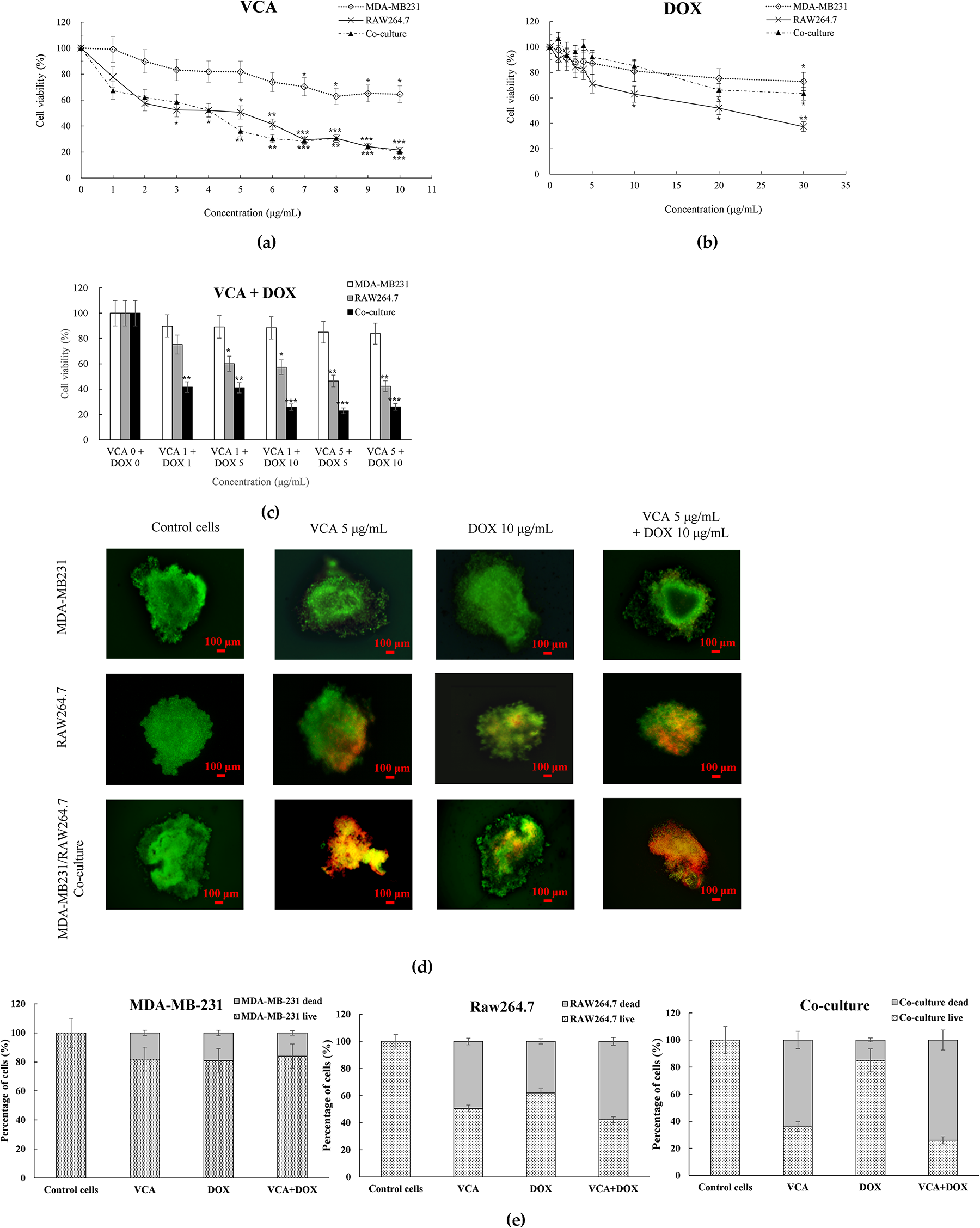

3.3 Combination Treatment Modulates Cytokine Secretion in Spheroid Cultures

To assess effects on angiogenic and inflammatory signaling, we measured VEGF, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion after 48-h treatment. VEGF analysis revealed dose-dependent suppression with combination treatment, achieving 39% reduction at VCA 5 μg/mL + DOX 10 μg/mL (990.8 pg/mL, p < 0.01) and 49% reduction at VCA 10 μg/mL + DOX 10 μg/mL (837.2 pg/mL, p < 0.001) in co-culture spheroids (Fig. 3a). IL-6, a key EMT-inducing cytokine, showed elevated baseline levels in co-culture spheroids (842.7 pg/mL) compared to MDA-MB-231 monoculture (245.3 pg/mL). VCA monotherapy dose-dependently reduced IL-6 in co-culture, with 10 μg/mL achieving 51% reduction (412.8 pg/mL, p < 0.01). Combination treatments showed enhanced suppression: VCA 5 + DOX 10 reduced IL-6 by 66% (287.3 pg/mL, p < 0.01), and VCA 10 + DOX 10 achieved 74% reduction (215.8 pg/mL, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). Conversely, TNF-α levels increased with VCA treatment. In co-culture spheroids, VCA 10 μg/mL elevated TNF-α from 156.8 to 298.5 pg/mL (1.9-fold, p < 0.01). Combination treatments further enhanced TNF-α: VCA 5 + DOX 10 increased levels 2.5-fold (385.2 pg/mL, p < 0.01), while VCA 10 + DOX 10 achieved 2.7-fold elevation (428.9 pg/mL, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3c). RAW264.7 macrophages alone showed no detectable VEGF or IL-6 secretion, while TNF-α levels remained at baseline (approximately 180–240 pg/mL) regardless of VCA treatment, indicating that the significantly elevated cytokine responses observed in co-cultures resulted from tumor-macrophage interactions. These reciprocal changes in IL-6 (decreased) and TNF-α (increased) suggest a shift in macrophage secretory profile from pro-tumoral to anti-tumoral phenotype, correlating with the enhanced cytotoxicity observed at these dose combinations.

Figure 3: Cytokine secretion profiles in 3D spheroid cultures. (a) VEGF secretion levels, (b) IL-6 secretion levels, and (c) TNF-α secretion levels following 48 h treatment with VCA at indicated concentrations in MDA-MB-231 monoculture spheroids, RAW264.7 macrophages alone, and co-culture spheroids. Cytokine concentrations in conditioned media were determined by ELISA. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test comparing each treatment to the untreated control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

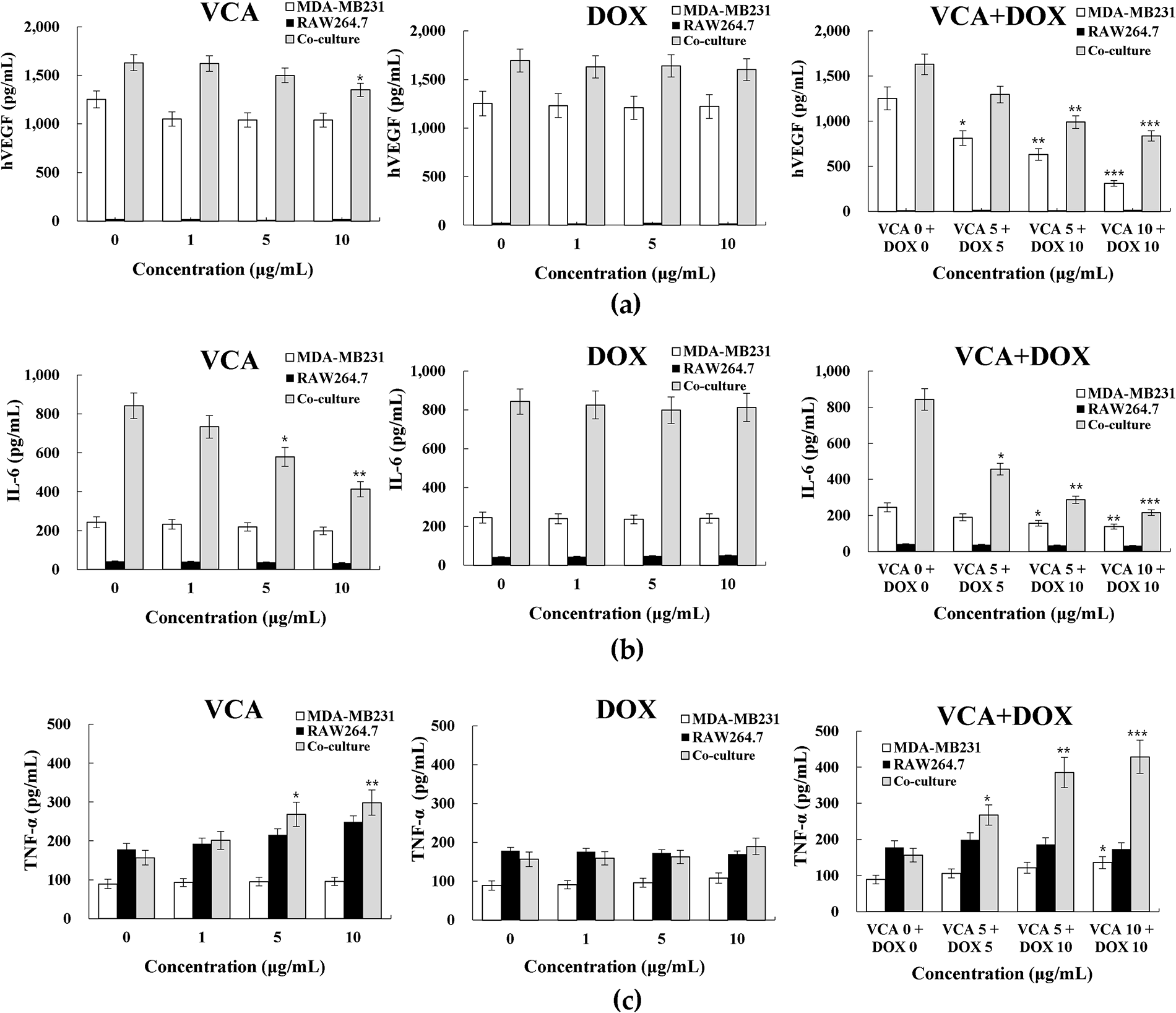

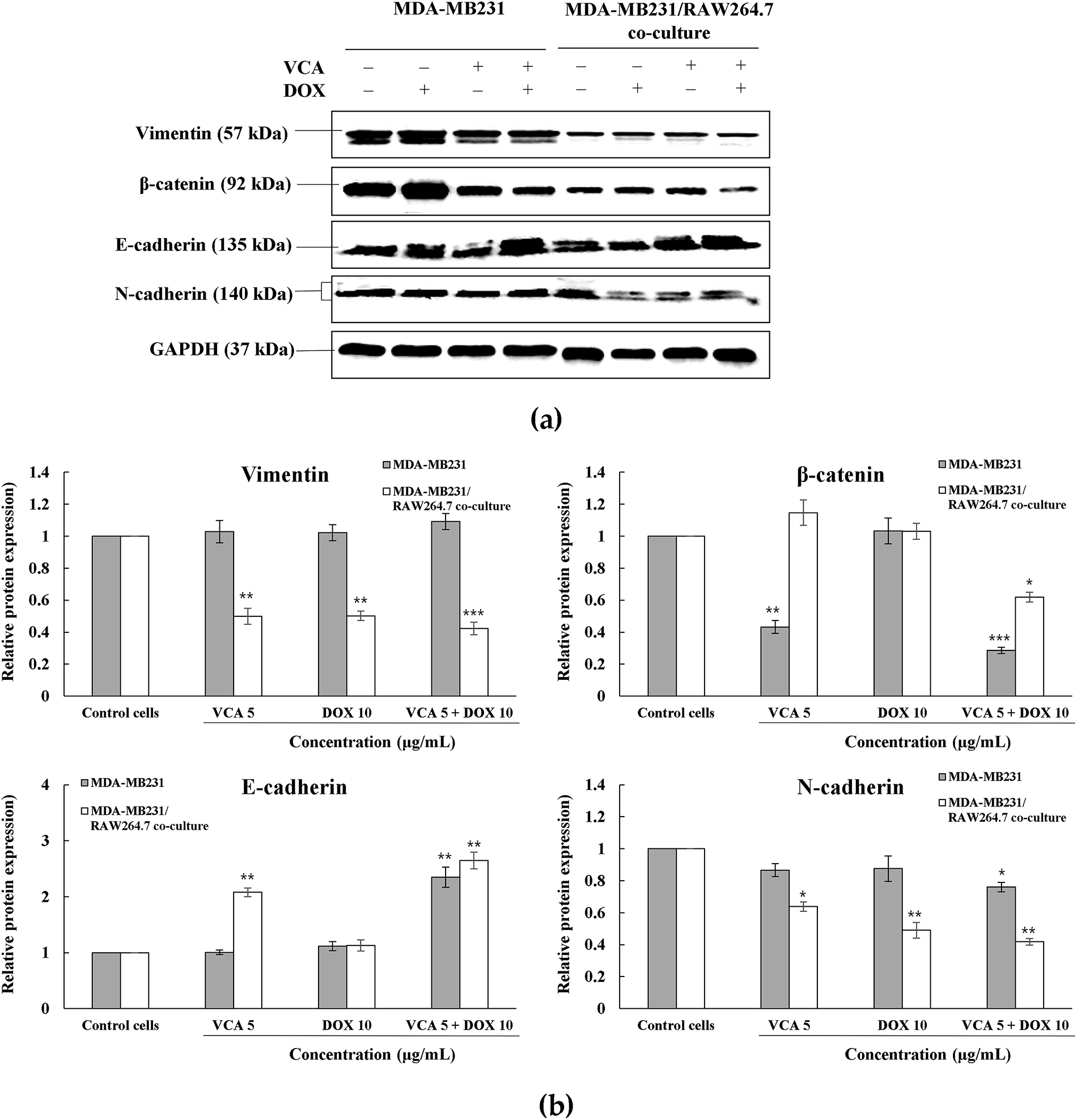

3.4 Modulation of EMT-Related Proteins by Combination Treatment

Western blot analysis revealed differential expressions of EMT markers between monoculture and co-culture spheroids (Fig. 4a). Vimentin expression showed contrasting responses: in MDA-MB-231 monoculture, all treatments had minimal effect (1.03–1.09 fold, all p > 0.05), while in co-culture spheroids, VCA alone suppressed vimentin (0.50-fold, p < 0.01) with further reduction by combination treatment (0.42-fold, p < 0.001). β-catenin expression was reduced by VCA treatment in both systems. In MDA-MB-231 spheroids, VCA alone reduced β-catenin to 0.43-fold (p < 0.01), with combination treatment causing further suppression (0.29-fold, p < 0.001). Co-culture spheroids showed more modest but reduction only with combination treatment (0.62-fold, p < 0.05). E-cadherin, an epithelial marker typically lost during EMT, was upregulated by combination treatment in both MDA-MB-231 (2.35-fold, p < 0.01) and co-culture spheroids (2.65-fold, p < 0.01). VCA monotherapy also increased E-cadherin in co-culture (2.08-fold, p < 0.01) but not in monoculture. N-cadherin expression patterns differed between spheroid types. In MDA-MB-231 monoculture, only the combination treatment reduced N-cadherin (0.76-fold, p < 0.05). However, in co-culture spheroids, all treatments suppressed N-cadherin: VCA (0.64-fold, p < 0.05), DOX (0.49-fold, p < 0.01), and combination (0.42-fold, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that the VCA-DOX combination promotes mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, with enhanced effects in the presence of macrophages, observed in vimentin suppression and E-cadherin upregulation.

Figure 4: Western blot analysis of EMT markers in 3D spheroid cultures. (a) Representative Western blot images showing the expression of vimentin, β-catenin, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin in MDA-MB231 and MDA-MB231/RAW264.7 co-culture spheroids following 48 h treatment with VCA (5 μg/mL), DOX (10 μg/mL), or combination. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (b) Densitometric quantification of protein expression normalized to GAPDH and presented as fold change relative to the respective control. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test comparing each treatment to the untreated control within each cell type. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

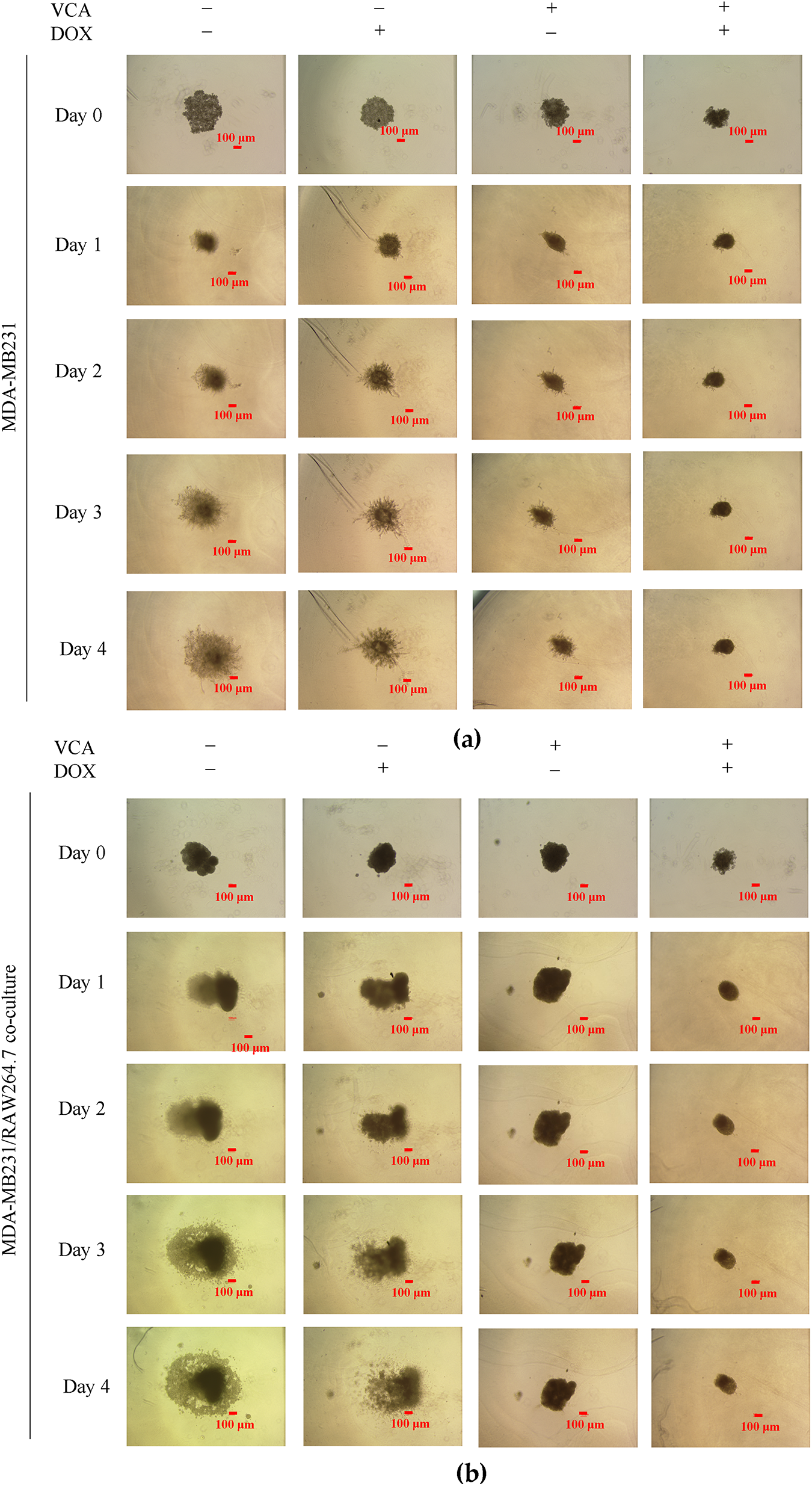

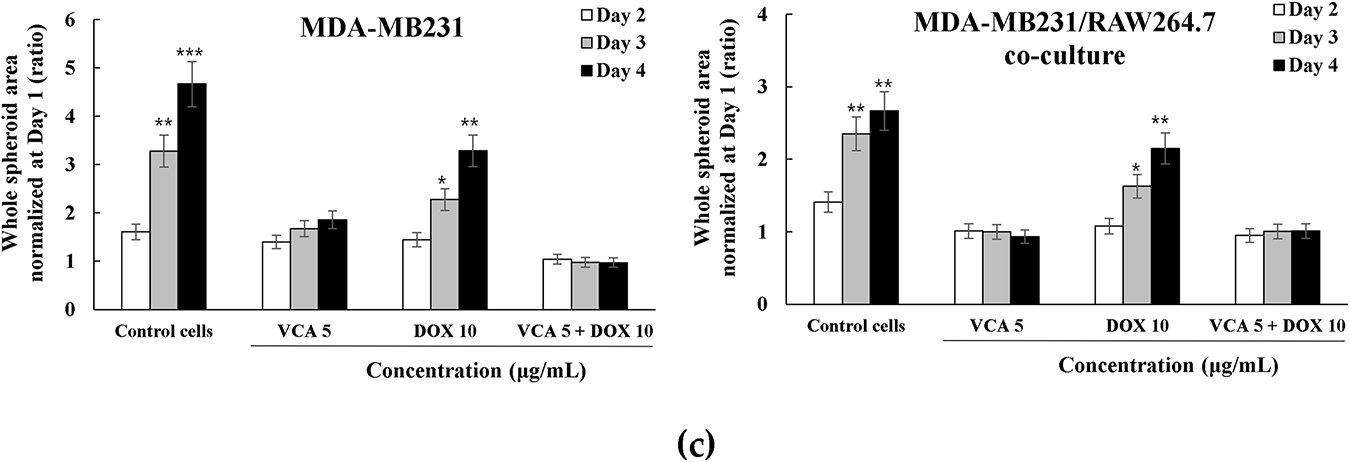

3.5 Inhibition of Spheroid Invasion by Combination Treatment

To evaluate the anti-metastatic potential of treatments, we assessed spheroid invasion capacity using Matrigel-embedded invasion assays over 4 days (Fig. 5a,b). Untreated MDA-MB-231 spheroids exhibited aggressive invasive behavior, with cells migrating radially from the spheroid core into the surrounding matrix. Quantitative analysis revealed progressive expansion of the whole spheroid area (including invading cells) from day 1 baseline to 4.67-fold by day 4 (p < 0.001 vs. day 1). VCA monotherapy (5 μg/mL) suppressed this invasive phenotype, limiting expansion to only 1.86-fold by day 4. DOX treatment (10 μg/mL) showed intermediate inhibition, with spheroids expanding 3.28-fold (p < 0.01 vs. day 1). Strikingly, combination treatment abolished invasive capacity, maintaining spheroid area at baseline levels throughout the 4-day period (0.97-fold at day 4, p > 0.05 vs. day 1) (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5: 3D spheroid invasion assay in Matrigel-coated plates. (a) Representative brightfield images showing spheroid morphology and invasion patterns of MDA-MB231 cells from Day 0 to Day 4 following treatment with VCA (5 μg/mL), DOX (10 μg/mL), or combination. (b) Representative brightfield images of MDA-MB231/RAW264.7 co-culture spheroids under the same treatment conditions. (c) Quantification of whole spheroid area (including invading cells) normalized to Day 1 (set as 1.0) for both MDA-MB231 monoculture and co-culture spheroids. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test comparing each time point to Day 1 within each treatment group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Scale bar: 100 μm for all images

Co-culture spheroids containing both MDA-MB-231 and RAW264.7 cells displayed distinct invasion patterns. Control co-culture spheroids showed reduced baseline invasiveness compared to MDA-MB-231 monoculture, expanding only 2.67-fold by day 4 (p < 0.01 vs. day 1), suggesting macrophages may initially restrict cancer cell invasion. However, this invasive growth was still significant. DOX monotherapy partially suppressed invasion in co-culture (2.15-fold by day 4, p < 0.01), while VCA alone showed anti-invasive efficacy, maintaining spheroids at baseline size (0.93-fold). Combination treatment prevented invasion in co-culture spheroids (1.01-fold at day 4) (Fig. 5c).

These results demonstrate that while macrophages modulate baseline invasive behavior, VCA-DOX combination suppresses tumor invasion regardless of macrophage presence, with VCA contributing the primary anti-invasive activity.

The tumor microenvironment, particularly tumor-associated macrophages, represents a critical determinant of chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer. TAMs constitute up to 50% of the tumor mass in breast cancers and demonstrate phenotypic plasticity that enables them to modulate drug sensitivity through multiple mechanisms [5]. Studies have shown that TAMs can limit DOX delivery to tumors by producing MMP9, which decreases blood vessel permeability, and that recruitment of monocytes increases after DOX treatment, contributing to resistance [32]. In TNBC specifically, where treatment options remain limited to cytotoxic chemotherapy [1,3], understanding how TAMs influence drug response has become important for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Our findings demonstrate that VCA enhances DOX efficacy specifically in the presence of TAMs, suggesting that macrophage reprogramming rather than direct cytotoxicity may contribute to the mechanism. This observation is consistent with findings that high CD163+ TAM infiltration correlates with poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients [33]. Such macrophage-dependent drug responses underscore the limitations of traditional monoculture drug screening approaches and highlight the importance of incorporating stromal components, particularly TAMs, in preclinical drug evaluation models [21,22]. While our use of murine RAW264.7 macrophages with human TNBC cells represents a xenogeneic model, the key signaling pathways governing macrophage polarization and tumor-macrophage crosstalk are evolutionarily conserved between mice and humans.

Building on the importance of macrophage-tumor interactions in drug response, we employed human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells and murine RAW264.7 macrophages in 3D spheroid co-cultures to dissect the underlying mechanisms. RAW264.7 macrophages acquire TAM-like properties when co-cultured with breast cancer cells, exhibiting enhanced secretion of pro-tumoral factors, including OSM and IL-6 [20], and respond to tumor-derived factors through conserved signaling pathways including NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT [34]. Importantly, the 3D format captures spatial gradients and cell-cell interactions that 2D cultures cannot replicate, particularly for macrophage polarization [35,36]. Similar xenogeneic models have successfully elucidated tumor-macrophage interactions: Heaster et al. used RAW264.7 with PyVMT mouse breast carcinoma cells to study metabolic heterogeneity [37], and Mas-Rosario et al. tracked macrophage polarization using RAW264.7 with human breast cancer cells [34]. Critically, we have extensively validated VCA’s immunomodulatory effects using human macrophages in previous studies. THP-1 human macrophages co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells [38] demonstrated that human macrophages significantly modulate VCA-induced apoptosis and cytokine secretion (IL-6, TNF-α). Subsequently, our work with THP-1-derived M1/M2 polarized macrophages in both 2D and 3D systems [39] comprehensively characterized how polarized human macrophages differentially respond to VCA treatment and influence breast cancer cell survival. These prior studies with human macrophages support VCA’s immunomodulatory mechanisms. However, translational relevance should be interpreted cautiously as the current study used murine rather than human macrophages. Nevertheless, the highly conserved TAM-related signaling pathways between murine and human systems support our model’s validity for investigating fundamental TAM-tumor interactions.

The intermediate compaction phenotype of co-culture spheroids reflects balanced heterotypic cell-cell interactions, consistent with previous reports demonstrating that tumor-macrophage crosstalk modulates spheroid assembly dynamics [40]. The uniform distribution of fluorescently-labeled cells throughout our co-culture spheroids, rather than segregation into distinct regions, indicates stable intercellular adhesion between MDA-MB-231 and RAW264.7 cells and persistent tumor-macrophage contacts, rather than the dynamic rearrangement observed in other heterotypic models [41,42]. Such stable heterotypic interactions have been shown to be critical for maintaining long-term co-culture viability and function [43]. The observation that VCA-DOX synergy occurs exclusively in co-culture suggests that macrophages play a critical role in VCA’s chemosensitizing effects. This co-culture-specific enhancement builds upon our systematic prior characterization of VCA-DOX interactions in 2D monoculture systems. We previously established VCA-DOX synergistic effects in 2D MDA-MB-231 cells [26], demonstrating enhanced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through direct drug-cell interactions. This foundational work has been comprehensively extended in our recent mechanistic study [44] which provides a detailed characterization of VCA-DOX interactions in 2D MDA-MB-231 monocultures, including oxidative stress modulation, apoptotic pathway activation, migration inhibition, and proliferative recovery. These 2D studies established the baseline cellular mechanisms of VCA-DOX synergy. Beyond doxorubicin, we have investigated VCA in combination with cisplatin. Our recent study [45] examined VCA combined with cisplatin in both 2D and 3D spheroid models, demonstrating synergistic effects through apoptosis induction and EMT modulation. This work also confirmed that 3D cultures exhibit differential drug sensitivity compared to 2D cultures, validating the importance of dimensionality in drug combination studies. The consistency of VCA’s chemosensitizing effects with different chemotherapeutic agents suggests broader therapeutic potential in TNBC treatment. The dramatic enhancement of chemosensitivity observed specifically in 3D co-culture (IC50 reduction from 18.4 to 0.8 μM) cannot be attributed solely to the direct drug interactions characterized in 2D studies. Instead, this co-culture-specific synergy directly implicates macrophage-mediated mechanisms as an additional layer enhancing the baseline drug effects. The enhanced sensitivity of co-culture spheroids to VCA monotherapy compared to minimal effects in monoculture further supports this macrophage-dependent mechanism. Previous studies have demonstrated that VCA can modulate macrophage phenotype and function, including the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and enhanced antigen presentation [8,46]. V. album lipophilic extract has been shown to modulate tumor cell-induced macrophage polarization in vitro, shifting them away from the tumor-supportive M2 phenotype [47]. TAMs promote cancer cell survival through various mechanisms, including COX-2-mediated positive feedback loops between macrophages and cancer cells [48], which could contribute to how disrupting these interactions with VCA results in enhanced chemosensitivity. The moderate synergy rather than strong synergy suggests that while VCA and DOX work cooperatively, they may not target completely independent pathways, which is consistent with both agents ultimately inducing apoptosis [49]. Our findings align with Hong and Lyu’s recent demonstration that VCA reversed the protective effect of M2 macrophages on breast cancer cells in 3D models [39].

Co-culture spheroids exhibited elevated baseline VEGF, confirming that macrophages contribute significantly to pro-angiogenic signaling in the tumor microenvironment [32,50]. This aligns with previous studies demonstrating that TAMs are major sources of VEGF in solid tumors, promoting angiogenesis through paracrine signaling [51]. The combination treatment significantly suppressed VEGF secretion in both monoculture and co-culture systems, suggesting that VCA-DOX targets angiogenic signaling. However, partial resistance to anti-angiogenic effects persisted in the presence of macrophages, which may be attributed to alternative pro-angiogenic factors secreted by TAMs, including IL-8, basic fibroblast growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinases [52,53]. The ability of the VCA-DOX combination to reduce macrophage-enhanced angiogenic potential represents a significant therapeutic advance, given that VEGF-mediated angiogenesis is a primary driver of tumor progression and metastasis in TNBC [54].

The cytokine profiling revealed mechanistic insights into VCA’s immunomodulatory effects. The reciprocal modulation of cytokines—decreased IL-6 and increased TNF-α—indicates a shift in macrophage functional state that correlates with enhanced chemosensitivity. IL-6, which promotes EMT through STAT3 activation [55] and cancer cell survival through anti-apoptotic signaling [56], was significantly suppressed by VCA treatment, potentially explaining the enhanced DOX sensitivity observed in co-cultures. Previous studies have demonstrated that mistletoe lectin can induce TNF-α secretion from human mononuclear cells [57], supporting our observation. The shift from high IL-6/low TNF-α to low IL-6/high TNF-α profile is consistent with altered cytokine balance, but additional markers (iNOS, CD206, ARG1) are needed to confirm macrophage polarization [58,59]. This cytokine shift has direct implications for EMT regulation, as IL-6 is a key inducer of mesenchymal transformation.

The implications of our findings extend beyond cytotoxicity to potential modulation of EMT, a critical process in cancer metastasis and therapeutic resistance. TAMs are known to promote EMT through the secretion of various factors, including TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-8, which activate transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, and ZEB1 that drive mesenchymal transformation [60,61]. TAMs have been shown to induce cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in multiple malignant tumors, including breast cancer, with their tumor-promoting effects closely associated with EMT induction [48]. The EMT marker modulation observed in our study—enhanced E-cadherin expression and reduced mesenchymal markers specifically in co-culture—indicates that VCA reverses TAM-induced EMT, potentially explaining the synergistic effects. The intermediate compaction phenotype observed in our co-culture spheroids could reflect a partial EMT state, which has been associated with maximum metastatic potential [62]. Given that EMT represents a major therapeutic challenge in TNBC, particularly in tumors with high TAM infiltration [63], combining VCA with conventional chemotherapy could address multiple aspects of tumor progression simultaneously through direct cytotoxicity, TAM reprogramming, and EMT reversal.

Beyond EMT modulation, the molecular mechanisms underlying VCA’s dual effects merit consideration. VCA’s dual anticancer mechanism warrants mechanistic exploration beyond the observed functional outcomes. The ribosome-inactivating A-chain and galactose-binding B-chain structure [64] enables simultaneous direct cytotoxicity and immune modulation. The observed functional outcomes—including enhanced apoptosis, EMT reversal, and cytokine modulation—are consistent with established mistletoe lectin signaling patterns involving ERK phosphorylation [65] and STAT3 inhibition [66]. Critically, VCA induced a mixed M1/M2 macrophage phenotype—characterized by co-expression of iNOS/TNF-α and Arg-1/IL-10—rather than complete polarization [39,47]. This phenotypic plasticity challenges the binary M1/M2 paradigm and may explain the enhanced cancer cell killing despite retained M2 markers. Previous studies demonstrate that VCA activates caspase-8 through TNFR1 signaling [14] while simultaneously triggering mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis [67], providing parallel death pathways that could account for the synergy (CI = 0.72) with DOX. Macrophage-derived cytokines, particularly the elevated TNF-α observed in this study, likely amplify these direct cytotoxic effects, as mistletoe lectins potentiate TNF-α-induced apoptosis [68]. This convergence of direct and indirect mechanisms—where immune modulation enhances chemosensitivity while preserving cytotoxic functions—represents a therapeutic advantage over single-pathway targeting.

While our study provides valuable insights into macrophage-mediated chemosensitization, several limitations should be acknowledged. The key limitations of this study include: (1) use of a single TNBC cell line (MDA-MB-231), (2) the xenogeneic co-culture model using murine macrophages with human cancer cells, and (3) lack of vascular and perfusion components, and (4) limited dose combination matrix for synergy analysis. Regarding the first limitation, the current study focused exclusively on MDA-MB-231 cells to enable in-depth mechanistic characterization of TAM-cancer cell interactions in 3D co-culture. However, we have previously validated VCA’s anticancer effects across multiple breast cancer cell lines [39], including MCF-7 (ER-positive breast cancer), BT-549 (another TNBC line showing comparable VCA sensitivity to MDA-MB-231), and MCF-10A normal breast epithelial cells. Critically, MCF-10A cells exhibited significantly lower VCA sensitivity (>3-fold higher IC50 compared to cancer cells), demonstrating cancer cell selectivity and addressing potential normal tissue toxicity concerns. These multi-cell line validations provide confidence that VCA’s effects extend beyond the single MDA-MB-231 model used in the current 3D co-culture study, though direct validation of the VCA-DOX combination in 3D co-culture systems with additional TNBC cell lines remains an important future direction. Regarding the second limitation, while the use of murine RAW264.7 macrophages with human MDA-MB-231 cells represents a xenogeneic model, this combination is well-established in breast cancer research with demonstrated biological relevance [69–72]. Multiple studies have successfully used this exact cell combination to investigate tumor-macrophage interactions, including NO production, migration, cytokine signaling, and osteoclast differentiation [69,70,72]. The key pathways we investigate—NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, and MAPK—are highly conserved between murine and human systems, as confirmed by comparative studies using this model [69,70]. RAW264.7 cells have been shown to respond appropriately to human breast cancer cell-derived signals, validating their use in modeling TAM behavior and tumor-immune crosstalk [71,72]. Nevertheless, species-specific differences in certain cytokine-receptor interactions may not be fully captured. Regarding the third limitation, our spheroid model, though more physiologically relevant than 2D cultures, lacks the dynamic perfusion and vascular components present in vivo [73,74]. The incorporation of endothelial cells and flow-based culture systems could better recapitulate drug delivery kinetics and immune cell recruitment observed in tumors [75]. Future studies should employ patient-derived organoid models with autologous immune cells to better predict individual therapeutic responses [76]. Regarding the fourth limitation, although a full 5 × 5 dose combination matrix would provide more comprehensive synergy characterization, our analysis of multiple dose combinations consistently demonstrated synergy in co-culture (CI = 0.26–0.72) vs. antagonism in monoculture (CI > 1).

The DOX concentration used in our study (20 μg/mL, approximately 34.5 μM) requires contextualization within the framework of 3D culture requirements. While this exceeds typical clinical plasma concentrations (0.5–1 μM), extensive literature demonstrates that 3D spheroid models consistently require 10-fold higher drug concentrations compared to 2D cultures [77]. This requirement stems from drug penetration following a broadened random walk pattern in 3D structures, reducing sustained drug-target interactions [78]. Multiple studies using breast cancer spheroids report DOX IC50 values ranging from 1.0–50 μM [79–81], with our concentration falling within this established range. The penetration barriers created by hypoxic and acidic microenvironments within spheroids necessitate these elevated concentrations [82]. Furthermore, comparative analyses show that chemotherapeutics, including doxorubicin, require 1.2- to 10-fold concentration increases in 3D vs. 2D systems [29,30]. Our approach aligns with standard protocols using 5–50 μg/mL DOX in 3D breast cancer studies [83–85], enabling meaningful cross-study comparisons. These concentrations, while supra-physiological, are essential to overcome the well-documented barriers of cell-cell adhesion, extracellular matrix resistance, and limited drug penetration characteristic of 3D tumor models [86,87].

The potential for VCA to mitigate DOX-induced cardiotoxicity warrants consideration, given the dose-limiting cardiac toxicity of anthracyclines [88]. DOX cardiotoxicity, mediated primarily through oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species generation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, limits cumulative doses to 450–550 mg/m2 [89,90]. While our study did not directly assess cardiac parameters, the synergistic anticancer effects observed at potentially lower effective doses suggest possible cardioprotective benefits through dose reduction. VCA-DOX combination achieved CI values of 0.72 in co-culture, indicating that lower doses of each agent could achieve equivalent therapeutic effects. This dose-sparing potential is particularly relevant as mistletoe extracts have demonstrated antioxidant properties and free radical scavenging activity [91,92], mechanisms that could theoretically counteract DOX-induced oxidative cardiac damage. Additionally, Viscum album preparations have shown cardiovascular benefits, including modulation of cardiac function parameters and reduction of oxidative stress markers [91]. However, direct evaluation of cardiac biomarkers, troponin levels, and left ventricular ejection fraction in VCA-DOX-treated models remains essential to confirm cardioprotective effects. Such studies would be crucial for clinical translation, particularly for TNBC patients requiring aggressive chemotherapy who are at high risk for anthracycline-associated cardiac complications.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that VCA exhibits dual anticancer mechanisms in TNBC-TAM reprogramming and enhanced chemosensitization. The synergistic effects observed exclusively in the presence of TAMs highlight the critical role of tumor-immune interactions in drug response. While Viscum album extracts have shown clinical benefits in improving the quality of life and reducing adverse events in cancer patients [93,94], our findings provide mechanistic insights into how VCA specifically targets the tumor-immune microenvironment. Our 3D co-culture model proved valuable for capturing complex tumor-immune interactions that are missed in conventional 2D cultures, emphasizing the importance of physiologically relevant models in drug discovery. The ability of VCA to sensitize TNBC cells to chemotherapy while simultaneously reprogramming TAMs addresses a critical clinical need, as TAM infiltration is associated with poor prognosis and therapeutic resistance in TNBC patients [95].

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-14-003).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Su-Yun Lyu; methodology, Chang-Eui Hong; validation, Chang-Eui Hong; formal analysis, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; investigation, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; resources, Su-Yun Lyu; data curation, Chang-Eui Hong; writing—original draft preparation, Chang-Eui Hong; writing—review and editing, Su-Yun Lyu; visualization, Chang-Eui Hong and Su-Yun Lyu; supervision, Su-Yun Lyu; project administration, Su-Yun Lyu; funding acquisition, Su-Yun Lyu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix

Figure A1: Viscum album L. var. coloratum agglutinin (VCA) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Twelve percent of polyacrylamide gel was used as separating gel and 4% was used as stacking gel. The samples were treated with a reducing agent, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), if necessary and loaded into the wells of the gel. The samples were electrophoresed at 100 V for 1 h and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Lane 1: molecular marker, lane 2: VCA with 2-ME, lane 3: VCA without 2-ME. In the absence of the reducing agent, the molecular mass of VCA was 60 kDa. On the other hand, in the presence of the reducing agent, VCA showed two bands consisting of a 30 kDa A-chain and a 32 kDa B-chain

References

1. Chen IE, Lee-Felker S. Triple-negative breast cancer: multimodality appearance. Curr Radiol Rep. 2023;11(4):53–9. doi:10.1007/s40134-022-00410-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Qavi Q, Alkistawi F, Kumar S, Ahmed R, Saad Abdalla Al-Zawi A. Male triple-negative breast cancer. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14542. doi:10.7759/cureus.14542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fasril T, Hilbertina N, Elliyanti A. Treatment problems in triple negative breast cancer. Int Islam Med J. 2023;4(2):51–8. doi:10.33086/iimj.v4i2.3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jiang CF, Xie YX, Qian YC, Wang M, Liu LZ, Shu YQ, et al. TBX15/miR-152/KIF2C pathway regulates breast cancer doxorubicin resistance via promoting PKM2 ubiquitination. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):542. doi:10.1186/s12935-021-02235-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Xiao M, He J, Yin L, Chen X, Zu X, Shen Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: critical players in drug resistance of breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12:799428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.799428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Qiu X, Zhao T, Luo R, Qiu R, Li Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: key players in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:772615. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.772615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Fu W, Song J, Li H. Breviscapine reverses doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer and its related mechanisms. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(27):2785–92. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.15072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Saha C, Das M, Stephen-Victor E, Friboulet A, Bayry J, Kaveri SV. Differential effects of Viscum album preparations on the maturation and activation of human dendritic cells and CD4+ T cell responses. Molecules. 2016;21(7):912. doi:10.3390/molecules21070912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xiao M, Bian Q, Lao Y, Yi J, Sun X, Sun X, et al. SENP3 loss promotes M2 macrophage polarization and breast cancer progression. Mol Oncol. 2022;16(4):1026–44. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pe KCS, Saetung R, Yodsurang V, Chaotham C, Suppipat K, Chanvorachote P, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer influences a mixed M1/M2 macrophage phenotype associated with tumor aggressiveness. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273044. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0273044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Oda H, Hedayati E, Lindström A, Shabo I. GATA-3 expression in breast cancer is related to intratumoral M2 macrophage infiltration and tumor differentiation. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0283003. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0283003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Nicoletti M. The anti-inflammatory activity of Viscum album. Plants. 2023;12(7):1460. doi:10.3390/plants12071460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yosri N, Kamal N, Mediani A, AbouZid S, Swillam A, Swilam M, et al. Immunomodulatory activity and inhibitory effects of Viscum album on cancer cells, its safety profiles and recent nanotechnology development. Planta Med. 2024;90(14):1059–79. doi:10.1055/a-2412-8471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Khil LY, Kim W, Lyu S, Park WB, Yoon JW, Jun HS. Mechanisms involved in Korean mistletoe lectin-induced apoptosis of cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(20):2811–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Thronicke A, Oei SL, Merkle A, Matthes H, Schad F. Clinical safety of combined targeted and Viscum album L. therapy in oncological patients. Medicines. 2018;5(3):100. doi:10.3390/medicines5030100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yoon TJ, Yoo YC, Kang TB, Song SK, Lee KB, Her E, et al. Antitumor activity of the Korean mistletoe lectin is attributed to activation of macrophages and NK cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26(10):861–7. doi:10.1007/BF02980033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Braedel-Ruoff S. Immunomodulatory effects of Viscum album extracts on natural killer cells: review of clinical trials. Forsch Komplementmed. 2010;17(2):63–73. doi:10.1159/000288702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kienle GS, Kiene H. Review article: influence of Viscum album L (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9(2):142–57. doi:10.1177/1534735410369673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Khabbazi S, Goumon Y, Parat MO. Morphine modulates interleukin-4- or breast cancer cell-induced pro-metastatic activation of macrophages. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11389. doi:10.1038/srep11389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Peyvandi S, Bulliard M, Yilmaz A, Kauzlaric A, Marcone R, Haerri L, et al. Tumor-educated Gr1+CD11b+ cells drive breast cancer metastasis via OSM/IL-6/JAK-induced cancer cell plasticity. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(6):e166847. doi:10.1172/JCI166847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Jeong SY, Lee JH, Shin Y, Chung S, Kuh HJ. Co-culture of tumor spheroids and fibroblasts in a collagen matrix-incorporated microfluidic chip mimics reciprocal activation in solid tumor microenvironment. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lee JH, Kim SK, Khawar IA, Jeong SY, Chung S, Kuh HJ. Microfluidic co-culture of pancreatic tumor spheroids with stellate cells as a novel 3D model for investigation of stroma-mediated cell motility and drug resistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):4. doi:10.1186/s13046-017-0654-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lyu SY, Park SM, Choung BY, Park WB. Comparative study of Korean (Viscum album var. coloratum) and European mistletoes (Viscum album). Arch Pharm Res. 2000;23(6):592–8. doi:10.1007/BF02975247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lyu SY, Park WB, Choi KH, Kim WH. Involvement of caspase-3 in apoptosis induced by Viscum album var. coloratum agglutinin in HL-60 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65(3):534–41. doi:10.1271/bbb.65.534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Park WB, Lyu SY, Kim JH, Choi SH, Chung HK, Ahn SH, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by Korean mistletoe lectin is associated with apoptosis and antiangiogenesis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2001;16(5):439–47. doi:10.1089/108497801753354348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hong CE, Park AK, Lyu SY. Synergistic anticancer effects of lectin and doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;394(1–2):225–35. doi:10.1007/s11010-014-2099-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lyu SY, Park WB. Effects of Korean mistletoe lectin (Viscum album coloratum) on proliferation and cytokine expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T-lymphocytes. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30(10):1252–64. doi:10.1007/BF02980266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bolte S, Cordelières FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224(Pt 3):213–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Elliott NT, Yuan F. A review of three-dimensional in vitro tissue models for drug discovery and transport studies. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(1):59–74. doi:10.1002/jps.22257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Huang L, Bockorny B, Paul I, Akshinthala D, Frappart PO, Gandarilla O, et al. PDX-derived organoids model in vivo drug response and secrete biomarkers. JCI Insight. 2020;5(21):e135544. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.135544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):440–6. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Larionova I, Cherdyntseva N, Liu T, Patysheva M, Rakina M, Kzhyshkowska J. Interaction of tumor-associated macrophages and cancer chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(7):1596004. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2019.1596004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Oner G, Praet M, Stoop H, Devi G, Canturk NZ, Altintas S, et al. Tumor microenvironment modulation by tumor-associated macrophages: implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2025;17:211–24. doi:10.2147/bctt.s493085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Mas-Rosario JA, Medor JD, Jeffway MI, Martínez-Montes JM, Farkas ME. Murine macrophage-based iNos reporter reveals polarization and reprogramming in the context of breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1151384. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1151384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Joris F, Manshian BB, Peynshaert K, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, Soenen SJ. Assessing nanoparticle toxicity in cell-based assays: influence of cell culture parameters and optimized models for bridging the in vitro-in vivo gap. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(21):8339–59. doi:10.1039/c3cs60145e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kumar V, Naqvi SM, Verbruggen A, McEvoy E, McNamara LM. A mechanobiological model of bone metastasis reveals that mechanical stimulation inhibits the pro-osteolytic effects of breast cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2024;43(5):114043. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Heaster TM, Humayun M, Yu J, Beebe DJ, Skala MC. Autofluorescence imaging of 3D tumor-macrophage microscale cultures resolves spatial and temporal dynamics of macrophage metabolism. Cancer Res. 2020;80(23):5408–23. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Lim WT, Hong CE, Lyu SY. Immuno-modulatory effects of Korean mistletoe in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and THP-1 macrophages. Sci Pharm. 2023;91(4):48. doi:10.3390/scipharm91040048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hong CE, Lyu SY. Modulation of breast cancer cell apoptosis and macrophage polarization by mistletoe lectin in 2D and 3D models. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(15):8459. doi:10.3390/ijms25158459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Vakhshiteh F, Bagheri Z, Soleimani M, Ahvaraki A, Pournemat P, Alavi SE, et al. Heterotypic tumor spheroids: a platform for nanomedicine evaluation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):249. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-02021-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Carey SP, Starchenko A, McGregor AL, Reinhart-King CA. Leading malignant cells initiate collective epithelial cell invasion in a three-dimensional heterotypic tumor spheroid model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30(5):615–30. doi:10.1007/s10585-013-9565-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Franchi-Mendes T, Lopes N, Brito C. Heterotypic tumor spheroids in agitation-based cultures: a scaffold-free cell model that sustains long-term survival of endothelial cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:649949. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.649949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Chen AX, Chhabra A, Song HG, Fleming HE, Chen CS, Bhatia SN. Controlled apoptosis of stromal cells to engineer human microlivers. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(48):1910442. doi:10.1002/adfm.201910442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hong CE, Lyu SY. VCA augments doxorubicin efficacy in triple-negative breast cancer: evidence for multi-pathway synergism. Biocell. 2025;49:1–10. doi:10.32604/biocell.2025.072360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Lyu SY, Meshesha SM, Hong CE. Synergistic effects of mistletoe lectin and cisplatin on triple-negative breast cancer cells: insights from 2D and 3D in vitro models. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):366. doi:10.3390/ijms26010366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Mossalayi MD, Alkharrat A, Malvy D. Nitric oxide involvement in the anti-tumor effect of mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador on human macrophages. Arzneimittelforschung. 2006;56(6A):457–60. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1296812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Estko M, Baumgartner S, Urech K, Kunz M, Regueiro U, Heusser P, et al. Tumour cell derived effects on monocyte/macrophage polarization and function and modulatory potential of Viscum album lipophilic extract in vitro. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:130. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0650-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li H, Yang B, Huang J, Lin Y, Xiang T, Wan J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 in tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer cell survival by triggering a positive-feedback loop between macrophages and cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):29637–50. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.4936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Joice AC, Yang S, Farahat AA, Meeds H, Feng M, Li J, et al. Antileishmanial efficacy and pharmacokinetics of DB766-azole combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62(1):e01129–17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01129-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Vicioso L, Gonzalez FJ, Alvarez M, Ribelles N, Molina M, Marquez A, et al. Elevated serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor are associated with tumor-associated macrophages in primary breast cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125(1):111–8. doi:10.1309/0864af2u3lgpcf3j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Roland CL, Dineen SP, Lynn KD, Sullivan LA, Dellinger MT, Sadegh L, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor reduces angiogenesis and modulates immune cell infiltration of orthotopic breast cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(7):1761–71. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56(4):549–80. doi:10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Abou Shousha SA, Hussein B, Shahine Y, Fadali G, Zohir M, Hamed Y, et al. Angiogenic activities of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in breast cancer. Egypt J Immunol. 2022;29(3):54–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

54. Brogowska KK, Zajkowska M, Mroczko B. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6):2412. doi:10.3390/jcm12062412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Liu J, Liu Q, Qian W, Zong C, Wang R. IL-6 promotes metastasis and EMT of non-small cell lung cancer cells by up-regulating FGL1 via STAT3 pathway. Transl Cancer Res. 2025;14(7):3973–90. doi:10.21037/tcr-2025-119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(4):234–48. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Hajto T, Hostanska K, Frei K, Rordorf C, Gabius HJ. Increased secretion of tumor necrosis factors alpha, interleukin 1, and interleukin 6 by human mononuclear cells exposed to beta-galactoside-specific lectin from clinically applied mistletoe extract. Cancer Res. 1990;50(11):3322–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-75510-1_46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–86. doi:10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:13. doi:10.12703/P6-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Li X, Chen L, Peng X, Zhan X. Progress of tumor-associated macrophages in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tumor. Front Oncol. 2022;12:911410. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.911410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Chattopadhyay I, Ambati R, Gundamaraju R. Exploring the crosstalk between inflammation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Mediat Inflamm. 2021;2021:9918379. doi:10.1155/2021/9918379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Vasaikar SV, Deshmukh AP, Den Hollander P, Addanki S, Kuburich NA, Kudaravalli S, et al. EMTome: a resource for pan-cancer analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition genes and signatures. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(1):259–69. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01178-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Famta P, Shah S, Dey B, Kumar KC, Bagasariya D, Vambhurkar G, et al. Despicable role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer metastasis: exhibiting de novo restorative regimens. Cancer Pathog Ther. 2024;3(1):30–47. doi:10.1016/j.cpt.2024.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Han SY, Hong CE, Kim HG, Lyu SY. Anti-cancer effects of enteric-coated polymers containing mistletoe lectin in murine melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;408(1–2):73–87. doi:10.1007/s11010-015-2484-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Byeon SE, Lee JH, Yu T, Kwon MS, Hong SY, Cho JY. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase is a major enzyme in Korean mistletoe lectin-mediated regulation of macrophage functions. Biomol Ther. 2009;17(3):293–8. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2009.17.3.293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Park YR, Jee W, Park SM, Kim SW, Bae H, Jung JH, et al. Viscum album induces apoptosis by regulating STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):11988. doi:10.3390/ijms241511988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Choi SH, Lyu SY, Park WB. Mistletoe lectin induces apoptosis and telomerase inhibition in human A253 cancer cells through dephosphorylation of Akt. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27(1):68–76. doi:10.1007/BF02980049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Pae HO, Seo WG, Oh GS, Shin MK, Lee HS, Lee HS, et al. Potentiation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis by mistletoe lectin. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2000;22(4):697–709. doi:10.3109/08923970009016433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Lin CW, Shen SC, Ko CH, Lin HY, Chen YC. Reciprocal activation of macrophages and breast carcinoma cells by nitric oxide and colony-stimulating factor-1. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(12):2039–48. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Yamaguchi M, Murata T, Shimokawa N. Overexpression of RGPR-p117 reveals anticancer effects by regulating multiple signaling pathways in bone metastatic human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. IUBMB Life. 2025;77(1):e2939. doi:10.1002/iub.2939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Li B, Liu S, Yang Q, Li Z, Li J, Wu J, et al. Macrophages in tumor-associated adipose microenvironment accelerate tumor progression. Adv Biol. 2023;7(1):e2200161. doi:10.1002/adbi.202200161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Hollmén M, Roudnicky F, Karaman S, Detmar M. Characterization of macrophage-cancer cell crosstalk in estrogen receptor positive and triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9188. doi:10.1038/srep09188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Al Hrout A, Cervantes-Gracia K, Chahwan R, Amin A. Modelling liver cancer microenvironment using a novel 3D culture system. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8003. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11641-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yousafzai NA, El Khalki L, Wang W, Szpendyk J, Sossey-Alaoui K. Advances in 3D culture models to study exosomes in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers. 2024;16(5):883. doi:10.3390/cancers16050883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]