Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Case Report: Prominent Coronary Artery Flow in Fetuses with Congenital Heart Disease, Is It a Marker of In Utero Distress?

1 Ward Family Heart Center, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA

2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA

* Corresponding Author: Mohamed Aashiq Abdul Ghayum. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2024, 19(6), 647-651. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.058271

Received 09 September 2024; Accepted 24 January 2025; Issue published 27 January 2025

Abstract

Prominent coronary artery (CA) flow observed on a fetal echocardiogram has been associated with fetal growth restriction and myocardial dysfunction. We present two cases with this finding, in the presence of congenital heart disease (CHD) and absence of growth restriction or myocardial dysfunction. Both the cases rapidly progressed to extremis, necessitating emergent delivery. Our cases highlight the importance of recognizing prominent CA flow in fetuses with CHD as a potential marker for in utero distress.Keywords

Abbreviations

| CA | Coronary Artery |

| CAF | Coronary Artery Fistula |

| CHD | Congenital Heart Disease |

| CPR | Cerebroplacental Ratio |

| CS | Coronary Sinus |

| DV | Ductus Venosus |

| FE | Fetal Echocardiogram |

| GA | Gestational Age |

| IUGR | Intrauterine Growth Restriction |

| LAD | Left Anterior Descending |

| LCA | Left Coronary Artery |

| MCA | Middle Cerebral Artery |

| PI | Pulsatility Index |

| PWD | Pulsed Wave Doppler |

| TGA | Transposition of the Great Arteries |

| UA | Umbilical Artery |

| UV | Umbilical Vein |

| VSD | Ventricular Septal Defect |

Prominent coronary artery (CA) flow is uncommon in healthy fetuses. When present, it has been described as “heart-sparing” in a growth-restricted fetus [1]. Prominent CA flow is attributed to autoregulatory coronary vasodilation in response to hypoxia of a growth-restricted fetus or a fetus with isolated cardiac dysfunction to preserve myocardial oxygen demand [2,3]. Evidence suggests that prominent CA flow in fetuses with growth restriction or with cardiac dysfunction may confer poor outcomes [4]. However, the literature is lacking regarding the clinical implication of this finding in fetuses with congenital heart disease (CHD) in the absence of growth restriction or cardiac dysfunction.

Two cases with CHD are presented where prominent CA flow was inadvertently attributed to coronary artery fistulae in the absence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or myocardial dysfunction.

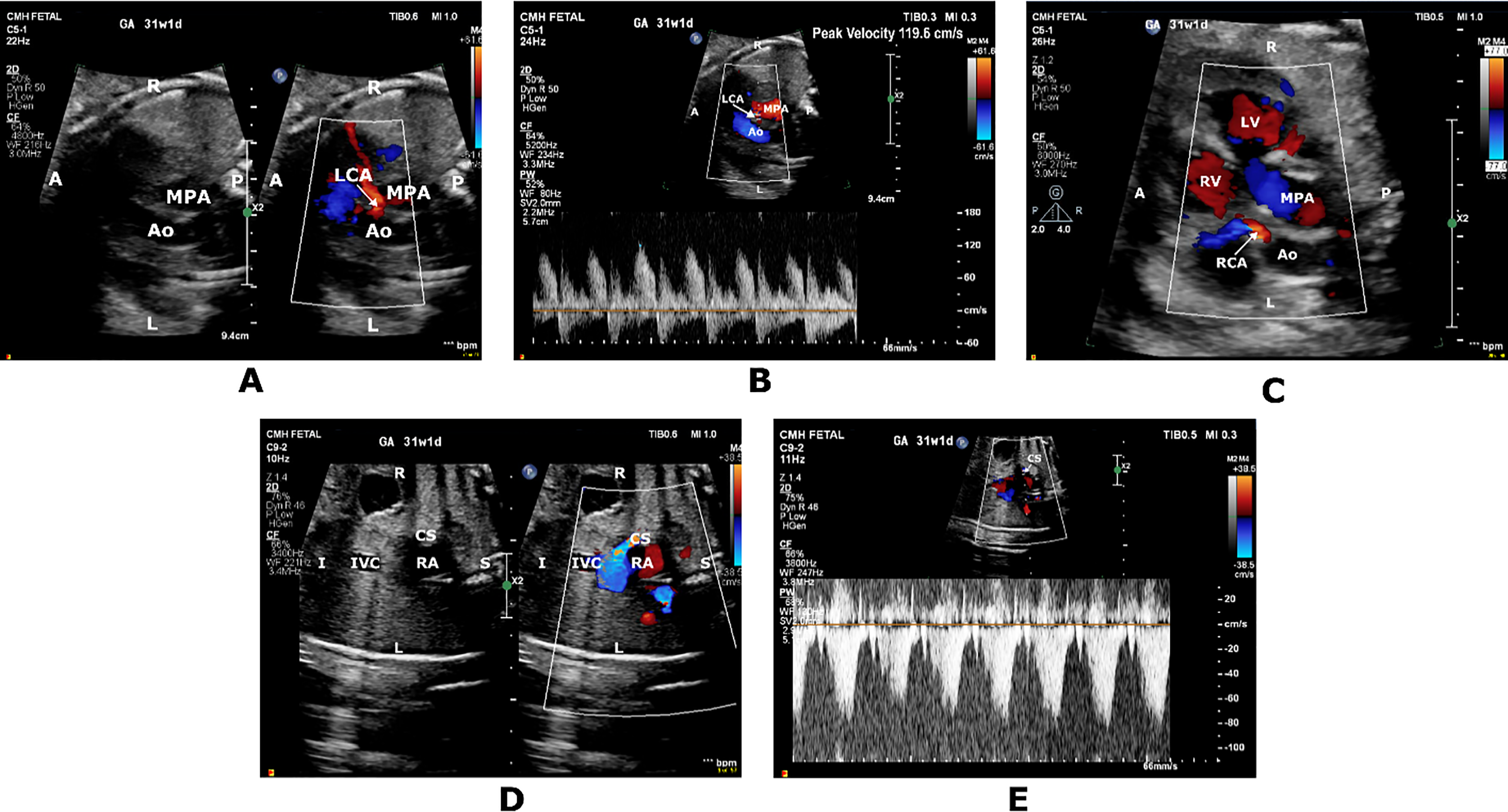

Fetal referral at 31 weeks’ gestational age (GA) for suspected complex CHD indicated the need for a fetal echocardiogram (FE) that demonstrated situs inversus totalis, dextrocardia and transposition of the great arteries (TGA) with atrial situs inversus, l-looped ventricles and l-malposed great vessels. There was mild cardiomegaly (right atrial and ventricular dilation), biphasic inflow Dopplers, and qualitatively normal biventricular systolic function. A CAF from the rightward aortic sinus was suspected to be heading towards the left ventricular free wall and terminating in the coronary sinus (CS) (Fig. 1). No flow reversal was seen in the ascending aorta. Prominent flow was also noted in the right CA. Umbilical artery (UA) pulsed wave Doppler (PWD) showed a pulsatility index (PI) of 0.61 (<5th percentile), Middle cerebral artery (MCA) PWD showed a PI of 0.65 (<5th percentile), and cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) of 1.07 (<5th percentile). Umbilical venous (UV) and ductus venosus (DV) Dopplers were normal. A week later, fetal heart rate decelerations prompted an emergent C-section. A female infant weighing 1810 g (64th percentile) with Apgar scores of 7,8 was delivered. Postnatal echocardiogram confirmed the prenatal CHD diagnoses with typical coronary origins for TGA, but no CAF was identified. Biventricular systolic function was normal with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 61%. Placental histopathology demonstrated evidence of focal chorangiosis. UA pH and pO2 were 7.27 and 21 mmHg, respectively. A successful arterial switch operation was performed at 7 weeks of age.

Figure 1: Short axis color-compare image (A) and pulsed wave Doppler tracing (B) showing prominent high-velocity diastolic flow originating from the rightward aortic sinus into the left coronary artery (LCA) territory. Short axis color Doppler image (C) showing prominent filling of the right coronary artery (RCA). Coronal color-compare image (D) and PWD tracing (E) showing prominent flow at the coronary sinus (CS) ostium returning to the right atrium (RA). A, anterior; Ao, Aorta; I, inferior; IVC, inferior vena cava; L, left; LV, left ventricle; MPA, main pulmonary artery; P, posterior; R, right; RA; right atrium; RV, Right ventricle; S; superior

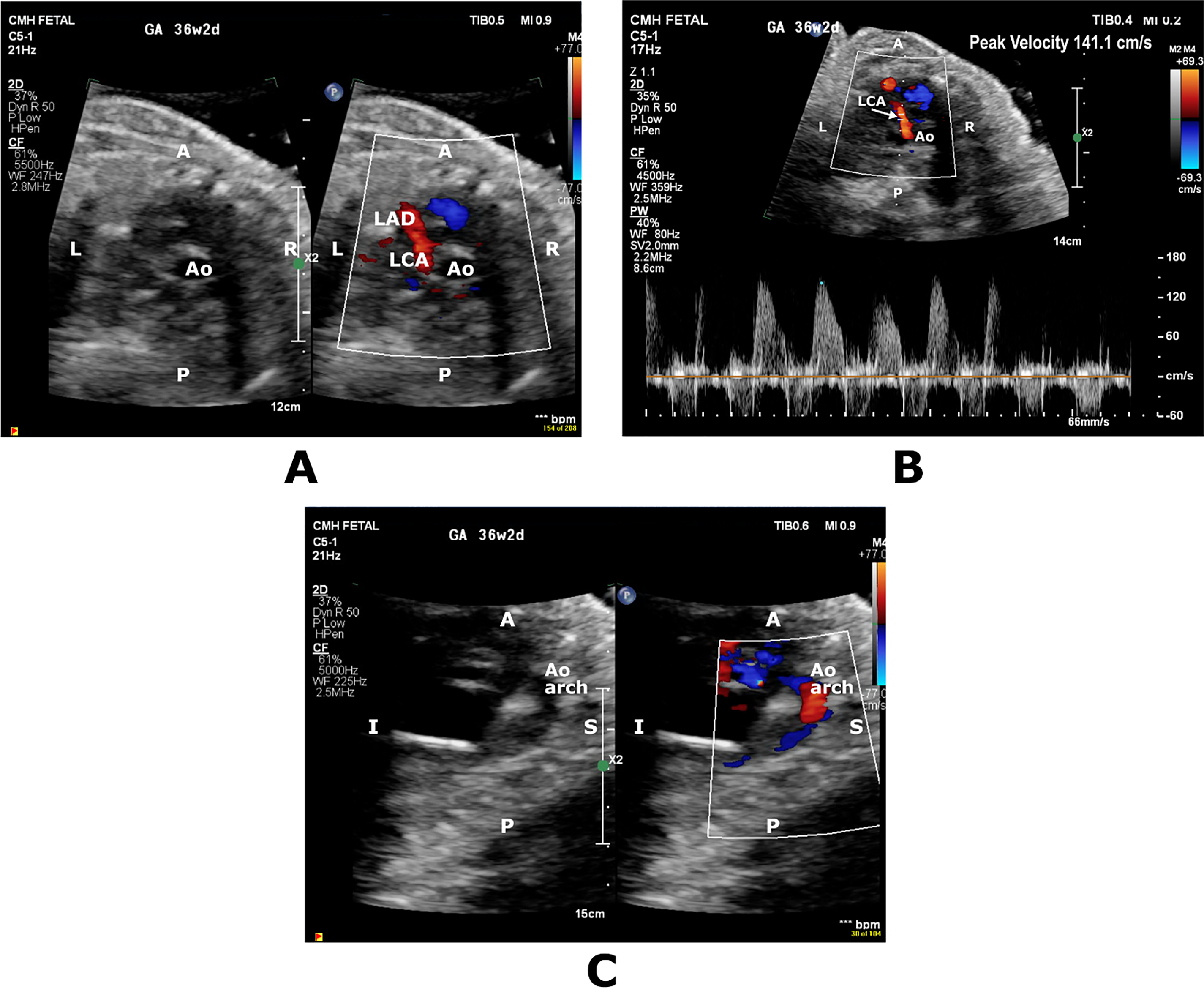

Fetal referral and FE for suspected CHD at 36 weeks’ GA demonstrated membranous ventricular septal defect (VSD) and mildly dilated right heart chambers. There was qualitatively normal biventricular systolic function with biphasic inflow Dopplers. Presence of dilated left main and left anterior descending (LAD) coronary arteries in combination with a dilated CS and retrograde flow in the transverse aortic arch led to suspicion for a CAF diagnosis (Fig. 2). PWD of the UA and MCA showed PI of 1.79 (>95th percentile) and PI 1.19 (<5th percentile), respectively and a CPR of 0.66 (<5th percentile). UV PWD showed pulsations. A DV PWD could not be obtained. Emergent C-section was performed the next day due to worsening extracardiac fetal Dopplers and non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern, delivering a male infant weighing 2530 g (33rd percentile) with Apgar scores of 5,8. Postnatal echocardiogram confirmed the prenatal diagnoses but revealed normal-sized coronaries and no CAF. Biventricular systolic function was normal with LVEF of 55%. Placental pathology revealed histologic features of fetal and maternal vascular malperfusion. UA pH and pO2 were abnormally low at 7.1 and 12 mmHg, respectively. Successful membranous VSD closure was performed at 4 months of age.

Figure 2: Short axis color-compare image and pulsed wave Doppler (A,B) showing prominent diastolic flow in the territory of left coronary artery (LCA) and left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD). Sagittal color-compare image (C) showing flow reversal in the transverse aortic arch (Ao Arch). A, anterior; Ao, Aorta; I, inferior; L, Left; P; Posterior, S; Superior, R; Right

Coronary flow by color Doppler on FE in normal fetuses can typically be visualized in the third trimester [3]. The capability of fetal CA flow autoregulation in response to increases in myocardial oxygen demand has been described as the heart-sparing effect. Acute and chronic fetal stress conditions can result in the heart-sparing effect appearing as prominent CA flow on FE. Such conditions include IUGR, myocardial dysfunction and, more rarely, severe fetal anemia, acute ductal constriction, fetal supraventricular tachycardia, and stress during open fetal surgery [1,5]. CAF can also be associated with prominent CA flow. CAF is confirmed with the identification of the fistulous connection between the coronary and a cardiac chamber or thoracic vessel and is usually present with other CHD [6,7].

In Case 1, we suspected a CAF from left coronary artery (LCA) to the CS. The UA and MCA indices did not corroborate brain sparing given PI values for both parameters were below the 5th percentile. No other markers indicated a fetal hypoxemic state or myocardial dysfunction. Inflow Dopplers were biphasic, and biventricular systolic function was preserved. PWD DV showed no a-wave reversal, and UV Doppler showed no pulsations. However, on follow-up, the fetus clearly demonstrated signs of in utero distress with heart rate decelerations leading to delivery. In retrospect, the finding of prominent CA flow in both coronary territories should have raised the possibility of heart-sparing rather than a CAF. Additionally, we suspect that, in this case, prominent CA flow was an early marker of acute fetal stress preceding the development of extracardiac Doppler abnormalities or cardiac dysfunction.

In Case 2, the suspicion of a CAF from LAD to the CS was raised in presence of retrograde flow in the transverse aortic arch and multiple VSDs. The UA, MCA, and UV indices were suggestive of in utero distress, albeit with normal cardiac function and no growth restriction. Baschat et al. [2] have suggested that prominent CA flow signifies hemodynamic deterioration in fetuses with IUGR and that this finding coincides with worsening extracardiac Dopplers. They postulate that sudden ability to visualize prominent CA flow is secondary to acute-on-chronic hypoxemia response. Our case demonstrated similar findings, and, in retrospect, awareness of this possibility may have led us to consider that, even without IUGR, these findings might be indicative of heart-sparing effect rather than a CHD-associated CAF.

Our cases required emergent delivery within 1–7 days of identification of prominent CA flow, which corroborates previously reported median survival time of 3.5 days after demonstration of prominent CA flow in IUGR fetuses with absent/reversed end-diastolic flow in the UA [8]. This finding highlights the time-sensitive nature of recognizing prominent CA flow as a marker of fetal distress and taking appropriate management steps for a positive outcome.

Prominent CA flow can be present without fetal growth restriction or myocardial dysfunction in fetuses with CHD. Even in the absence of other extracardiac Doppler findings to suggest uteroplacental insufficiency, presence of this finding can be a harbinger of fetal distress and warrants close fetal surveillance.

Acknowledgement: We thank the Medical Writing Center at Children’s Mercy Kansas City for editing this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this case report.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception, design: Mohamed Aashiq Abdul Ghayum, Nitin Madan; data collection: Mohamed Aashiq Abdul Ghayum, Nitin Madan, Maria Kiaffas, Ashley Warta, Melanie Kathol, David C. Mundy, Kelsey Brattrud; analysis and interpretation of results: Mohamed Aashiq Abdul Ghayum, Nitin Madan, Maria Kiaffas, David C. Mundy, Kelsey Brattrud, Melanie Kathol, Ashley Warta; draft manuscript preparation: Mohamed Aashiq Abdul Ghayum, Nitin Madan, Maria Kiaffas, David C. Mundy. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable—No new data generated.

Ethics Approval: This case report was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. According to the approval decision by the Children’s Mercy Kansas City Institutional Review Board (IRB) the study (Ethics Review ID: STUDY00003499) meets the criteria for an Exempt Review under 45 CFR 46.104(d) category 4 and has been approved for exemption. Additionally, the study has been granted a waiver of authorization under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), according to 45 CFR 164.512(i)(2)(ii), as it does not involve the use or disclosure of protected health information. Therefore, no further ethics review or approval is required for this study. Informed consent was obtained to publish this case report as per Children’s Mercy Authorization for Presentation of Case Report.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sehgal A, Menahem S. Evaluation of the coronary arteries in the foetus and newborn and their physiologic significance. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(10):1042–7. doi:10.3109/14767058.2013.766704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Baschat AA, Gembruch U, Reiss I, Gortner L, Weiner CP, Harman CR. Coronary artery blood flow visualization signifies hemodynamic deterioration in growth-restricted fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(5):425–31. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00237.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Maršál K. Physiological adaptation of the growth-restricted fetus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;49(suppl):37–52. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.02.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bui YK, Howley LW, Ambrose SE, Galan HL, Crombleholme TM, Drose J, et al. Prominent coronary artery flow with normal coronary artery anatomy is a rare but ominous harbinger of poor outcome in the fetus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(10):1536–40. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1057492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Baschat AA, Muench MV, Gembruch U. Coronary artery blood flow velocities in various fetal conditions. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(5):426–9. doi:10.1002/uog.82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gómez-Arriaga PI, Escribano D, Gómez-Montes E, Villalaín C, Mendoza A, Galindo A. Prenatal diagnosis of isolated coronary artery fistula: systematic review, analysis of perinatal prognostic factors and case report. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(1):2206938. doi:10.1080/14767058.2023.2206938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pisesky A, Nield LE, Rosenthal J, Jaeggi ET, Hornberger LK. Comparison of pre- and postnatally diagnosed coronary artery fistulae: echocardiographic features and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022;35(12):1322–35. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2022.07.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Baschat AA, Gembruch U, Reiss I, Gortner L, Diedrich K. Demonstration of fetal coronary blood flow by Doppler ultrasound in relation to arterial and venous flow velocity waveforms and perinatal outcome-the ‘heart-sparing effect’. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9(3):162–72. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09030162.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools