Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Physiological Pacing in Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries with Atrioventricular Block

1 Arrhythmia Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100037, China

2 Center for Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100037, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhimin Liu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 625-636. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.069214

Received 17 June 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA) is a rare congenital heart disease characterized by atrioventricular, ventriculoarterial, and conduction system discordance, commonly accompanied by atrioventricular block (AVB). Pacing in patients with CCTGA and AVB (both pediatric and adult) poses challenges in strategy selection, procedural complexity, and clinical decision-making due to limited evidence. Conventional morphological left ventricular pacing is widely adopted but may induce ventricular dyssynchrony, heart failure, and tricuspid valve dysfunction. While cardiac resynchronization therapy serves as an upgrade for pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and heart failure, its application may be limited by coronary sinus anatomical variations and uncertain clinical outcomes. His bundle pacing is rarely reported due to the variation of the His bundle and high pacing threshold. The superficial, wide, multi-branched left bundle branch favors left bundle branch pacing, though delayed systemic right ventricle (sRV) activation may cause ventricular dyssynchrony and impair sRV function. Right bundle branch pacing offers a novel alternative for pacing therapy. Conduction system pacing-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy is preferred in those with evidence of intrinsic ventricular conduction dysfunction. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on pacing strategies for CCTGA with AVB, integrating anatomical and pathophysiological insights to evaluate physiological pacing strategies, while highlighting critical knowledge gaps to guide future research.Keywords

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA) is a rare congenital heart disease characterized by atrioventricular and ventriculoarterial discordance, with the morphological left ventricle (mLV) connected to the pulmonary trunk and the morphological right ventricle (systemic right ventricle, sRV) connected to the aorta. CCTGA accounts for less than 1% of all congenital heart defects and approximately 0.03‰ of all live births [1]. Commonly associated anomalies include ventricular septal defects (VSD), pulmonary stenosis, tricuspid valve (TV) abnormalities, and abnormal cardiac position (dextrocardia/mesocardia) [2]. 7% to 40% of CCTGA cases present with rhythm abnormalities, particularly atrioventricular block (AVB) [1,3,4] due to a tenuous atrioventricular bundle.

For young patients who undergo postnatal interventions, surgical heart block raises concerns about long-term outcomes [5,6]. Among adults, 57% reportedly develop complete AVB by the average age of 40, with an annual progression risk of 2% [7,8]. Both scenarios consequently heighten the likelihood of requiring a permanent pacemaker.

Conventional mLV pacing, involving lead placement at the ventricular apex or septum myocardium, is a proven, reliable, and safe technique. However, it may result in sRV dysfunction and progressive TV regurgitation [9,10,11]. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is beneficial in mitigating or preventing heart failure from mLV pacing [10], while the anatomical variation of the coronary sinus (CS) brings difficulties in the implantation process [12]. Recently, conduction system pacing (CSP) has been demonstrated to promote physiologic activation of the sRV through direct stimulation of the His bundle, left bundle branch (LBB) [13] or the right bundle branch (RBB) [14]. His bundle pacing (HBP) shows promise as an alternative to CRT, but the unique positioning of the atrioventricular node (AVN) and His bundle in CCTGA introduces uncertainty in lead positioning [15]. Left bundle branch pacing (LBBP) effectively delivers physiological pacing and maintains electrical synchrony, demonstrating high implant success rates and low procedural complication rates [16,17]. Notably, the fan-like LBB just beneath the endocardium of the mLV septum may offer a broad target for LBBP in CCTGA [15,18]. Still, long-term and high-burden pacing in the mLV may deteriorate the sRV function. In contrast, pacing in the cord-like RBB can replicate LBBP activation patterns, potentially improving sRV function [19]. Conduction system pacing-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy (CSP-optimized CRT) combines CSP and biventricular resynchronization to address distal conduction abnormalities in CCTGA, particularly for patients with sRV delay or wide QRS duration [20,21].

This narrative review evaluates current pacing strategies for CCTGA with AVB, with particular focus on the anatomical and pathophysiological considerations of physiological pacing approaches, while identifying key knowledge gaps requiring further investigation.

Most CCTGA cases occur in situs solitus, though pediatric series report situs anomalies in 30–40% of patients [22,23]. In situs solitus CCTGA, the right atrium drains into the mLV through the mitral valve (MV), and the mLV supplies the pulmonary trunk. The left atrium empties into the sRV through TV, with the sRV connected to the aorta. Unlike the normal spiral great artery configuration, the aorta typically lies left-anterior to the pulmonary trunk. Thus, systemic venous return still reaches the lungs (pumped by a subpulmonary mLV), and oxygenated pulmonary venous blood is directed to the body (pumped by sRV). In situs inversus, the mLV is left-sided, and the aorta is usually right-positioned [4,24].

A mirror image distribution of coronary vasculature is observed in CCTGA. In situs solitus, the morphological left coronary artery originates from the anterior aortic sinus, with its short main stem dividing into the anterior interventricular and circumflex branches. The circumflex artery encircles the MV orifice. The morphological right coronary artery arises from the posterior aortic sinus and courses through the left atrioventricular groove to become the exclusive blood supply for the sRV [4]. This distinctive coronary anatomy predisposes to sRV hypoperfusion, potentially leading to myocardial ischemia and subsequent ventricular arrhythmias or complete heart block [25,26].

Coronary venous anatomy also demonstrates significant variability in CCTGA, thereby presenting challenges during the process of venous cannulation. While 88% of cases in a postmortem study of 51 specimens exhibited normal CS anatomy [27], common variations including separate or dual ostia and persistence of the vein of Marshall frequently complicate venous cannulation during CRT implantation [12,28].

The malalignment of the atrioventricular (AV) septum alters the conduction system course, resulting in an elongated and aberrant pathway that predisposes to AVB [18,29].

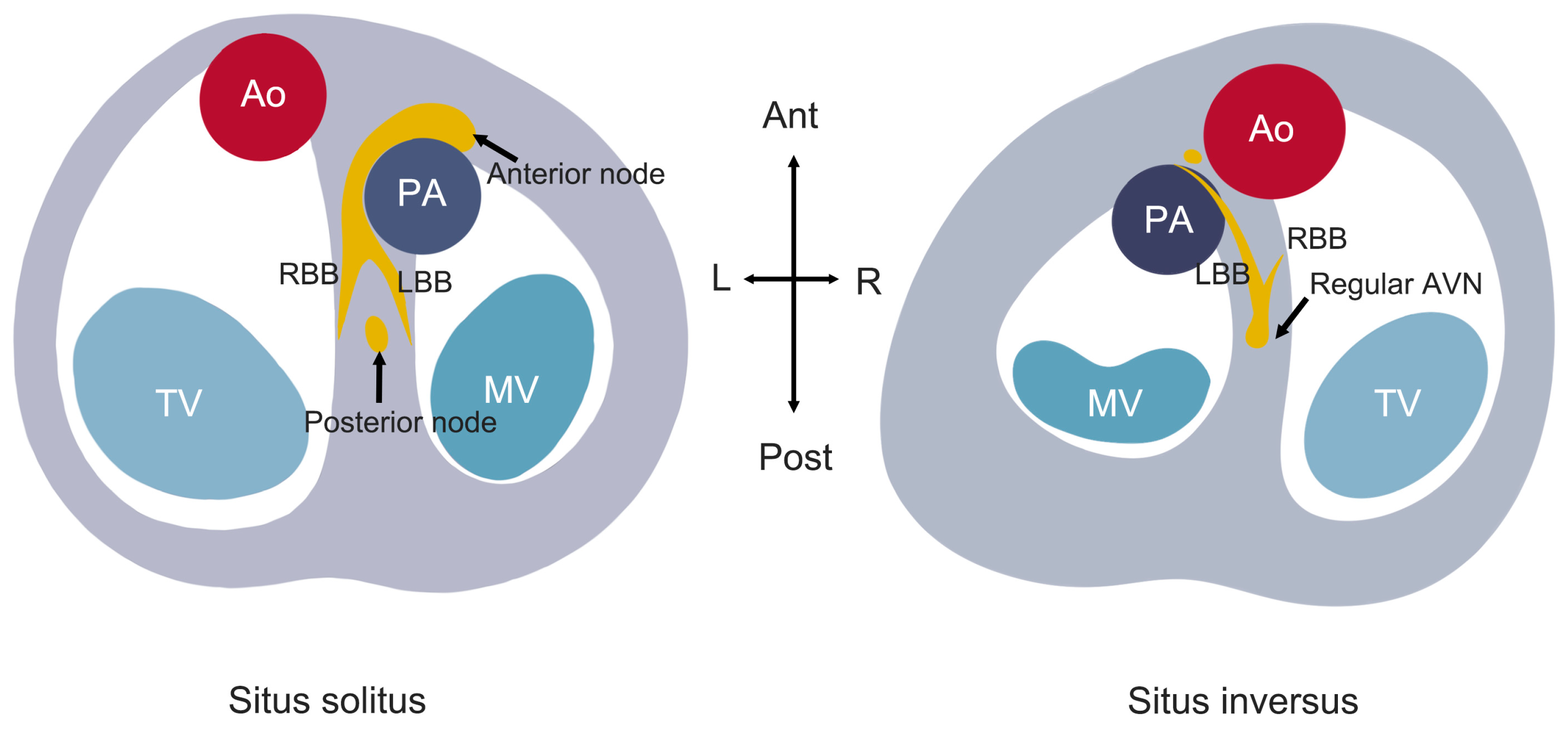

In situs solitus, the anterior node is situated anteriorly within the right atrial septum, giving rise to the penetrating AV bundle. The posterior node is located at the typical AVN position, with the posterior bundle making almost no contact with the ventricular musculature (Fig. 1). Anatomical abnormalities are strongly associated with AVB development. Hudson proposed that the discontinuity between the posterior node and bundle branches could lead to complete heart block [30]. Supporting this, Anderson et al. identified fibrous tissue disruption of the anterior bundle in histopathological analyses of 11 CCTGA cases, further implicating conduction system abnormalities in AVB pathogenesis [18]. These degenerative changes, particularly in older patients, significantly increase AVB susceptibility.

It is particularly noteworthy that in situs inversus, the cardiac anatomy demonstrates more optimal alignment of the atrial and ventricular septa. The His bundle originates from a normally positioned AVN and connects to the conduction bundle in a manner resembling AV-concordant hearts (Fig. 1). This anatomical preservation may explain the lower incidence of AVB in situs inversus—only 1 of 18 adult CCTGA patients developed AVB in a clinical series [23].

The elongated non-branching bundle courses along the subpulmonary outflow tract before dividing into: (1) a cord-like RBB extending to the sRV; (2) a broad, fan-like LBB along the mLV septal endocardium—providing an optimal target for LBBP.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the conduction system in CCTGA, illustrating the anatomical differences between situs solitus and situs inversus configurations.

3 Surgically Induced Atrioventricular Block

Approximately 64.7% of CCTGA patients require surgical intervention for associated defects during childhood [6], which further elevates AVB risk through iatrogenic injury to the already vulnerable conduction system.

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) frequently complicates CCTGA, affecting 50% of situs solitus patients but rarely occurring in situs inversus [23]. TV replacement or repair is the most commonly performed surgery in CCTGA with moderate or severe TR [31]. While TV surgery improves sRV function, it carries a 41% risk of pacemaker-requiring AVB within 10 years, with associated QRS prolongation and worsening heart failure [32]. Novel transcatheter techniques (transcatheter TV replacement, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair) offer alternatives for high-risk CCTGA patients, showing superior outcomes to medical therapy alone [9,11,33]. However, long-term outcomes remain limited regarding: (1) cardiac implantable electronic device-related TR management; (2) lead jailing safety/prognosis; (3) post-procedural mitral regurgitation risk under chronic pacing. Transseptal access further complicates the intervention process in CCTGA.

Postoperative AVB occurs in 1–3% of isolated VSD closure for non-CCTGA patients [34,35,36,37], with a higher risk in infants <4 kg [38]. Anatomic proximity of the AVN to the VSD’s posterior-inferior margin predisposes to conduction system injury during VSD repair, increasing pacemaker dependence [39]. In children <12 years, epicardial pacing shows higher lead failure rates [40], while long-term ventricular pacing reduces battery longevity and may impair ventricular function [41]. Therefore, the aberrant conduction anatomy in CCTGA itself warrants particular clinical attention to the risk of postoperative AVB during VSD closure.

4 Pacing Strategies in Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries

4.1 Conventional Morphological Left Ventricular Pacing

Conventional mLV pacing remains widely used in CCTGA, with the ventricular lead typically positioned at the mLV apex [5]. Evidence has demonstrated that conventional mLV pacing induces ventricular dyssynchrony and pacemaker-induced cardiomyopathy, which progressively impairs sRV function, leading to ventricular dilatation and deterioration [42,43,44,45]. These adverse hemodynamic consequences necessitate alternative pacing strategies in this sRV failure-prone population.

4.2 Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

CRT serves as a therapeutic option for CCTGA patients with AVB, particularly for pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and heart failure. CRT indications for CCTGA generally follow standard criteria but require additional anatomical and functional considerations. For patients in sinus rhythm, CRT carries a Class I recommendation when QRS duration is ≥150 ms with left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%. For pacemaker-dependent patients with LVEF ≤35% and high right ventricular pacing burden (>40%), CRT upgrade may be considered [46,47,48].

While CRT improves ventricular function [49] and transplant-free survival [50] in congenital heart disease with systolic dysfunction and electrical dyssynchrony [51], its application in CCTGA remains limited due to anatomical complexities. Key uncertainties persist regarding CS lead implantation techniques, optimal ventricular lead positioning [52], and long-term outcomes. CS angiography or cardiac computed tomography (CT) helps identify venous variants, facilitating transvenous lead placement in most cases [12]. The optimal ventricular lead configuration and determinants of long-term CRT efficacy in CCTGA remain poorly characterized [53,54,55], compounded by frequent concomitant hemodynamic and arrhythmic comorbidities. Large-scale studies are required to establish evidence-based implantation strategies.

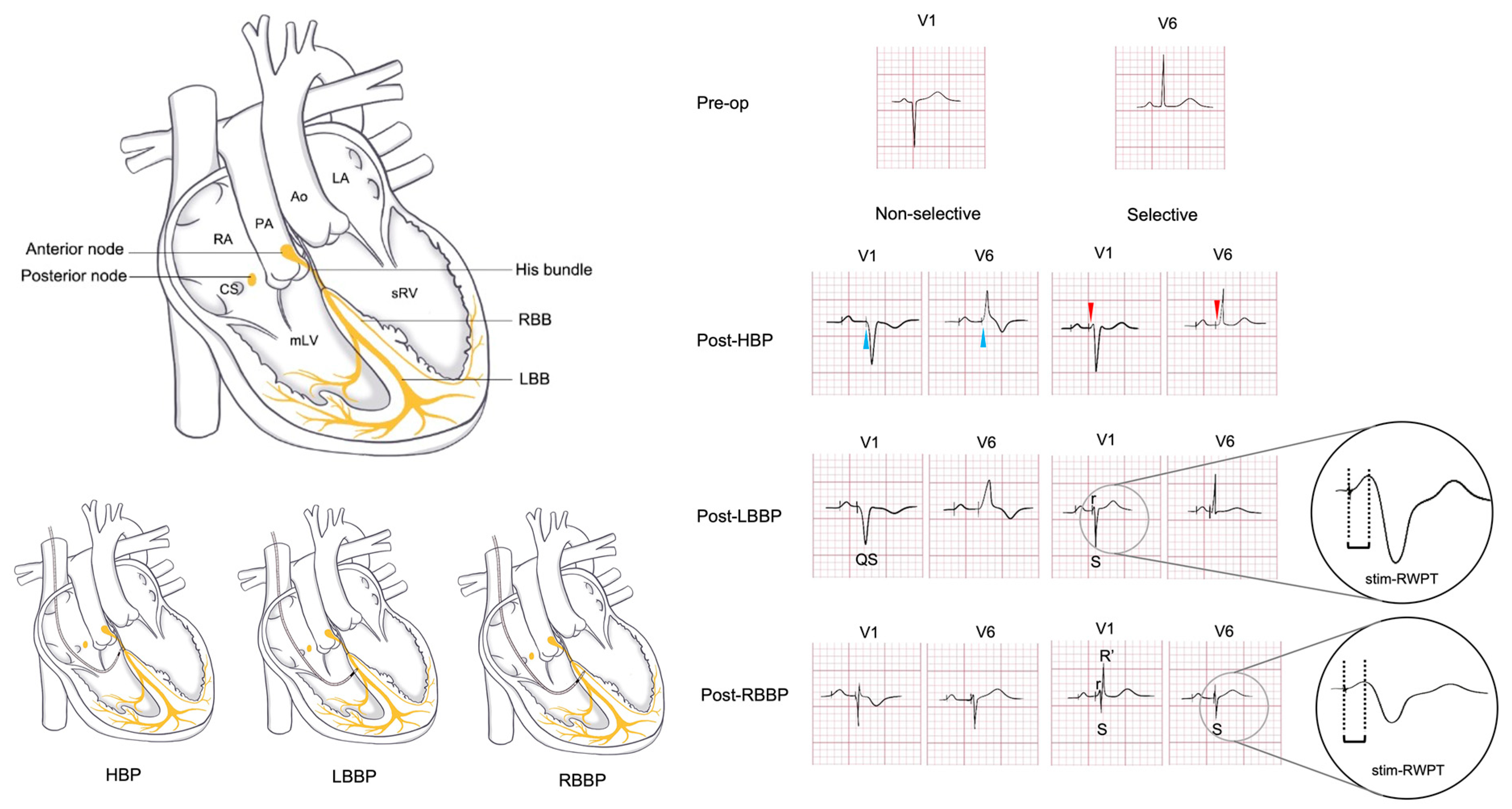

The 2023 CSP guideline recommends HBP/LBBP for CCTGA with AVB (Class IIb, Level of evidence C) [10]. A schematic diagram summarizing the currently reported physiological pacing strategies of HSP, LBBP, and RBBP is provided in Fig. 2. However, key aspects remain undefined, including implantation techniques, His bundle/LBB/RBB anatomy variations, optimal lead positioning, and long-term outcomes.

Figure 2: Preoperative and postoperative ECG patterns in CCTGA with situs solitus. The preoperative ECG of CCTGA patients without pulmonary stenosis or VSD typically shows a QS pattern in the V1 lead. This schematic illustrates the cardiac anatomy and corresponding ECG changes following CSP, delineating the distinctions between selective and non-selective capture. The depicted waveforms are derived from established literature and the authors’ clinical observations.

His-bundle localization is paramount for successful His-bundle pacing (HBP). In most non-congenital patients, His bundle can be mapped using the pacing lead by positioning the electrode tip near the tricuspid annulus under intracardiac electrogram guidance. Alternative approaches include: (1) fluoroscopic-guided positioning in the right anterior oblique (RAO) 30° projection followed by confirmation via high-output, high-frequency unipolar pacing with analysis of QRS morphology; (2) advanced imaging techniques such as three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping (3D-EAM), intracardiac echocardiography (ICE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), and tricuspid annular angiography [10,56].

However, these standard techniques face unique challenges in CCTGA due to the abnormal conduction system anatomy. The elongated His bundle in CCTGA courses anterior to the pulmonary annulus, frequently posing capture challenges. Limited successful cases have been documented: Takemoto et al. achieved HBP in an 8-year-old, demonstrating QRS narrowing (198 ms to 94 ms) with clinical improvement [57]. Vijayaraman et al. utilized 3D-EAM to localize the His bundle and LBB, achieving selective capture (0.5 V/1 ms) from initial nonselective HBP (1.5 V, 132 ms QRS) with 8.5 mV R-wave amplitude and 609 Ω impedance. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 2, selective and non-selective HBP exhibit distinct electrocardiographic features. Selective capture (red arrows) is identified by a consistent paced/native QRS morphology and a clear isoelectric line between the stimulus and QRS. Non-selective capture (blue arrows) demonstrates fusion at the stimulus site, resulting in the loss of the isoelectric line, a wider paced QRS, and T-wave discordance. Echocardiography confirmed lead tip position anterior to the pulmonic valve [58]. While HBP shows therapeutic potential for AVB, concerns remain regarding chronic threshold elevation and battery longevity. Large-scale trials are warranted to establish long-term efficacy.

4.3.2 Left Bundle Branch Pacing

In CCTGA patients, LBBP is typically performed via axillary or subclavian venous access. The procedure employs the widely adopted selected secure pacing lead (model 3830; Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) delivered through a fixed curve sheath (C315 HIS; Medtronic Inc.) under fluoroscopic guidance [13].

Crucially, the precise LBB location is critical for successful lead placement. As demonstrated in prior cadaveric studies, the LBB in CCTGA patients is characteristically superficial within the subendocardium of the mLV, exhibiting a broad, interconnected network that merges with the Purkinje system [15]. Intraoperative localization of the LBB can be achieved through several approaches. 3D-EAM provides optimal guidance, with initial experience in 7 pediatric CCTGA cases confirming the LBB’s accessible position and favorable morphology for pacing [19,59]. In the absence of 3D-EAM, fluoroscopic guidance (RAO 30° with 9-partition method) offers a practical alternative, though it demands substantial operator expertise in LBBP [60]. Also, TTE further aids lead positioning, with the target zone identified 2–3 cm from the tricuspid septal leaflet within the interventricular septum in apical four-chamber or subxiphoid views [61].

Currently, there are no established clinical diagnostic criteria for LBBP in CCTGA. Based on our institutional experience and systematic evaluation, we propose the following diagnostic criteria: (1) pacing lead positioned in the LBB region with a recordable LBB potential; (2) pacing ECG demonstrates RBBB morphology in V1; (3) short and consistent stimulus to R-wave peak (stim-RWPT) in V1 (65–80 ms); (4) sudden shortening of the stim-RWPT in V1 (≥10 ms) with increasing output; (5) for selective LBB capture: V1 shows rS/RS pattern with QRS duration <120 ms; (6) for non-selective LBB capture: non-selective LBB capture: V1 waveform less typical than above, with relatively narrow QRS duration (Fig. 2). We maintain that myocardial capture exhibits characteristics analogous to septal pacing, defined by: (1) paced QRS duration ≥120 ms, lacking typical bundle branch capture patterns; (2) V1 demonstrating a wide QS morphology; (3) stim-RWPT in V1 exceeding 85 ms [10,56].

Following the successful lead positioning, confirmation of adequate helical screw depth and stable fixation is essential. Fluoroscopic assessment of the tip-fulcrum distance helps evaluate septal penetration depth, while left anterior oblique (LAO) 30° sheath angiography and intraprocedural TTE provide additional confirmation. For selected secure pacing lead (model 3830; Medtronic Inc.), rebound testing should be avoided due to perforation risk. Instead, maintain gentle tension during sheath withdrawal, verify electrical parameters for stability, and ensure appropriate lead slack [56,61].

While LBBP demonstrates proven long-term benefits in non-congenital populations, its application in CCTGA raises unique concerns: pacing from the mLV subendocardium may delay transseptal activation, exacerbating ventricular dyssynchrony and potentially worsening sRV dysfunction. Current evidence remains limited, with intermediate-term (≤1 year) data showing preserved QRS duration and stable thresholds [13], though some report QRS widening post-LBBP in previously non-paced patients [19]. While preliminary findings suggest maintained sRV function [19,45], small cohort sizes and absent long-term follow-up necessitate cautious interpretation of these outcomes.

4.3.3 Right Bundle Branch Pacing

Right Bundle Branch Pacing (RBBP) represents an emerging physiological pacing strategy for CCTGA. In situs solitus, the RBB’s anatomical position mirrors the LBB in normal hearts, allowing analogous implantation techniques. A case report confirmed its feasibility using 3D-EAM, demonstrating QRS narrowing, stable parameters, and clinical improvement. Notably, selective RBBP is characterized by V1 showing “M” or rsR’ morphology with notched R’ waves and deep notched S waves in lead I/V5/V6, with short stim-RWPT in V5/V6 (38–72 ms) (Fig. 2) [14].

Challenges include the RBB’s cord-like morphology, which complicates transseptal capture, and its limited branching may reduce resynchronization efficacy versus LBBP. While 3D-EAM may address anatomical localization, further technical refinement is needed to establish RBBP’s safety profile and standardized protocols. Nevertheless, it expands physiological pacing options for CCTGA with AVB.

4.4 Conduction System Pacing-Optimized Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

Despite the successful implantation of CRT, failure can be found in improving ventricular function. Also, CSP may be ineffective in 10% of adult CCTGA patients with intrinsic ventricular conduction dysfunction [12]. Thus, CSP-optimized CRT has been described as a strategy to overcome distal Purkinje or myocardial disease by directly recruiting late-activated myocardial segments [20]. Case reports demonstrated that CSP-optimized CRT could benefit bi-ventricular resynchronization in CCTGA, resulting in an improved electrocardiographic and clinical response. An algorithmic approach to CRT for adult CCTGA is employed. For intact AV conduction with evidence of sRV electrical delay, CSP-optimized CRT is pursued. With narrow QRS, CSP targeting the distal His bundle or proximal LBB alone is expected to maintain electrical synchrony. With wide QRS, CSP-optimized CRT is preferred [21].

CCTGA is a rare congenital heart defect characterized by the abnormal positioning of the heart’s main chambers. AVB, often being intrinsic or caused by surgical impairment, is a common associated rhythm abnormality. Thus, permanent pacing therapy is often required. However, due to limited pacing experiences in such rare cases, the lack of clinical evidence greatly restricts the treatment of CCTGA with AVB. We hope this review on pacing therapy in patients of CCTGA with AVB can increase further clinical research and highlight the emerging role of physiological pacing.

In pediatric populations, surgical intervention can fundamentally address the problem, reducing the implantation rate of pacemaker devices in minors and directly altering the prognosis. However, surgical procedures often lead to serious AVB due to damage to the conduction system. While transient postoperative conduction disturbances may resolve spontaneously, permanent pacemaker implantation introduces long-term device-related complications, including lead dislodgement, lead fracture, and pacing-induced cardiomyopathy—particularly concerning given the anticipated decades of device dependency. We advocate for refined surgical techniques that minimize conduction tissue trauma, thereby reducing permanent pacing requirements in this vulnerable population.

For adult patients, congenital anatomical abnormalities of the conduction system are often caused by the formation of adipose tissue and fibrous tissue with age. While conventional mLV pacing remains widely employed, long-term mLV pacing carries the risk of pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and subsequent heart failure. CRT serves as the primary upgrade strategy for such cases, though its efficacy may be limited by CCTGA’s unique CS anatomy. Recent clinical experience with CSP in CCTGA reveals important anatomical and technical considerations. There are few cases for HBP, probably due to the variation of His bundle (especially when combined with VSD) and high pacing threshold. In contrast, the superficial, wide, and multi-branched LBB in the mLV may provide a proper anatomical basis for pacing assisted by 3D-EAM. However, chronic LBB capture may still induce intraventricular dyssynchrony, resulting in delayed activation of the sRV and subsequent sRV functional deterioration. RBBP in the deeper surface of the ventricular septum (near the sub-endocardium of the sRV) provides new ideas for pacing strategy for such patients. Importantly, these techniques show limited efficacy in patients with extensive distal conduction disease, where a hybrid approach combining CSP with CRT may better address both proximal and distal conduction abnormalities.

Our analysis suggests that while physiological pacing approaches show theoretical promise, future investigations should focus on: (1) technical refinements for CS lead placement in the context of coronary venous anomalies, as well as the optimal ventricular lead position in CRT; (2) improved electrophysiological mapping modalities for precise LBB and RBB localization; (3) development of evidence-based guidelines for physiological pacing in CCTGA. These advancements will require multicenter collaboration to overcome the challenges posed by the rarity and anatomical complexity of this condition.

This review highlights the anatomical and technical considerations for pacing in CCTGA with AVB, emphasizing the potential of physiological pacing. Current evidence remains limited by small cohorts and technical challenges, particularly in lead placement and long-term stability. Future studies should prioritize refining lead positioning techniques and multicenter collaboration to establish standardized approaches.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Zhuoxi Feng, Jinyang Liu; original draft preparation, Zhuoxi Feng, Jinyang Liu; review and editing, Zihao Wu, Zhimin Liu; visualization, Ziran Geng; supervision, Zhimin Liu. Zhuoxi Feng and Jinyang Liu contributed equally to this work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| 3D-EAM | Three-Dimensional Electroanatomical Mapping |

| Ao | Aorta |

| AV | Atrioventricular |

| AVB | Atrioventricular Block |

| AVN | Atrioventricular Node |

| CCTGA | Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries |

| CRT | Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy |

| CS | Coronary Sinus |

| CSP | Conduction System Pacing |

| CSP-optimized CRT | Conduction System Pacing-Optimized Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy |

| HBP | His Bundle Pacing |

| ICE | Intracardiac Echocardiography |

| LA | Left Atrium |

| LBB | Left Bundle Branch |

| LBBB | Left Bundle Branch Block |

| LBBP | Left Bundle Branch Pacing |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| mLV | Morphological Left Ventricle |

| MV | Mitral Valve |

| PA | Pulmonary Artery |

| Pre-op | Pre-Operation |

| Post-op | Post-Operation |

| RA | Right Atrium |

| RBB | Right Bundle Branch |

| RBBP | Right Bundle Branch Pacing |

| sRV | Systemic Right Ventricle |

| stim-RWPT | Stimulus to R-Wave Peak |

| TEE | Transesophageal Echocardiography |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

| TV | Tricuspid Valve |

| TR | Tricuspid Regurgitation |

| VSD | Ventricular Septal Defect |

References

1. Cohen J , Arya B , Caplan R , Donofrio MT , Ferdman D , Harrington JK , et al. Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: fetal diagnosis, associations, and postnatal outcome: a fetal heart society research collaborative study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023; 12( 11): e029706. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.029706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Schwedler G , Lindinger A , Lange PE , Sax U , Olchvary J , Peters B , et al. Frequency and spectrum of congenital heart defects among live births in Germany: a study of the competence network for congenital heart defects. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011; 100( 12): 1111– 7. doi:10.1007/s00392-011-0355-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Tseng WC , Huang CN , Chiu SN , Lu CW , Wang JK , Lin MT , et al. Long-term outcomes of arrhythmia and distinct electrophysiological features in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries in an Asian cohort. Am Heart J. 2021; 231: 73– 81. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2020.10.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wallis GA , Debich-Spicer D , Anderson RH . Congenitally corrected transposition. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011; 6: 22. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kasar T , Ayyildiz P , Tunca Sahin G , Ozturk E , Gokalp S , Haydin S , et al. Rhythm disturbances and treatment strategies in children with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018; 13( 3): 450– 7. doi:10.1111/chd.12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Krummholz A , Gottschalk I , Geipel A , Herberg U , Berg C , Gembruch U , et al. Prenatal diagnosis, associated findings and postnatal outcome in fetuses with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021; 303( 6): 1469– 81. doi:10.1007/s00404-020-05886-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huhta JC , Maloney JD , Ritter DG , Ilstrup DM , Feldt RH . Complete atrioventricular block in patients with atrioventricular discordance. Circulation. 1983; 67( 6): 1374– 7. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.6.1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Baumgartner H , De Backer J , Babu-Narayan SV , Budts W , Chessa M , Diller GP , et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Russ J Cardiol. 2021; 26( 9): 4702. doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2021-4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Andreas M , Burri H , Praz F , Soliman O , Badano L , Barreiro M , et al. Tricuspid valve disease and cardiac implantable electronic devices. Eur Heart J. 2024; 45( 5): 346– 65. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chung MK , Patton KK , Lau CP , Dal Forno ARJ , Al-Khatib SM , Arora V , et al. 2023 HRS/APHRS/LAHRS guideline on cardiac physiologic pacing for the avoidance and mitigation of heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2023; 20( 9): e17– 91. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.03.1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Vaturi M , Kusniec J , Shapira Y , Nevzorov R , Yedidya I , Weisenberg D , et al. Right ventricular pacing increases tricuspid regurgitation grade regardless of the mechanical interference to the valve by the electrode. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010; 11( 6): 550– 3. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jeq018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Moore JP , Cho D , Lin JP , Lluri G , Reardon LC , Aboulhosn JA , et al. Implantation techniques and outcomes after cardiac resynchronization therapy for congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Heart Rhythm. 2018; 15( 12): 1808– 15. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Moore JP , Gallotti R , Shannon KM , Pilcher T , Vinocur JM , Cano Ó , et al. Permanent conduction system pacing for congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: a pediatric and congenital electrophysiology society (PACES)/international society for adult congenital heart disease (ISACHD) collaborative study. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17( 6): 991– 7. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Namboodiri N , Kakarla S , Mohanan Nair KK , Abhilash SP , Saravanan S , Pandey HK , et al. Three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping guided right bundle branch pacing in congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries. Europace. 2023; 25( 3): 1110– 5. doi:10.1093/europace/euac239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Baruteau AE , Abrams DJ , Ho SY , Thambo JB , McLeod CJ , Shah MJ . Cardiac conduction system in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and its clinical relevance. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017; 6( 12): e007759. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.007759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Su L , Wang S , Wu S , Xu L , Huang Z , Chen X , et al. Long-term safety and feasibility of left bundle branch pacing in a large single-center study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021; 14( 2): e009261. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.120.009261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Huang W , Su L , Wu S , Xu L , Xiao F , Zhou X , et al. A novel pacing strategy with low and stable output: pacing the left bundle branch immediately beyond the conduction block. Can J Cardiol. 2017; 33( 12): 1736.e1– 3. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Anderson RH , Becker AE , Arnold R , Wilkinson JL . The conducting tissues in congenitally corrected transposition. Circulation. 1974; 50( 5): 911– 23. doi:10.1161/01.cir.50.5.911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Silvetti MS , Favoccia C , Saputo FA , Tamburri I , Mizzon C , Campisi M , et al. Three-dimensional-mapping-guided permanent conduction system pacing in paediatric patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Europace. 2023; 25( 4): 1482– 90. doi:10.1093/europace/euad026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vijayaraman P . Left bundle branch pacing optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy a novel approach. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021; 7( 8): 1076– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2021.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Su J , Lam WW , Contractor A , Moore JP . Conduction system pacing-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy for congenitally corrected transposition. JACC Case Rep. 2025; 30( 4): 103000. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2024.103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Biliciler-Denktas G , Feldt RH , Connolly HM , Weaver AL , Puga FJ , Danielson GK . Early and late results of operations for defects associated with corrected transposition and other anomalies with atrioventricular discordance in a pediatric population. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001; 122( 2): 234– 41. doi:10.1067/mtc.2001.115241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Oliver JM , Gallego P , Gonzalez AE , Sanchez-Recalde A , Brett M , Polo L , et al. Comparison of outcomes in adults with congenitally corrected transposition with situs inversus versus situs solitus. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 110( 11): 1687– 91. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kowalik E . Management of congenitally corrected transposition from fetal diagnosis to adulthood. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2023; 21( 6): 389– 96. doi:10.1080/14779072.2023.2211264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hauser M , Bengel FM , Hager A , Kuehn A , Nekolla SG , Kaemmerer H , et al. Impaired myocardial blood flow and coronary flow reserve of the anatomical right systemic ventricle in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Heart. 2003; 89( 10): 1231– 5. doi:10.1136/heart.89.10.1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hauser M , Meierhofer C , Schwaiger M , Vogt M , Kaemmerer H , Kuehn A . Myocardial blood flow in patients with transposition of the great arteries—risk factor for dysfunction of the morphologic systemic right ventricle late after atrial repair. Circ J. 2015; 79( 2): 425– 31. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bottega NA , Kapa S , Edwards WD , Connolly HM , Munger TM , Warnes CA , et al. The cardiac veins in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: delivery options for cardiac devices. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6( 10): 1450– 6. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ding L , Zhang H , Yu F , Mi L , Hua W , Zhang S , et al. Angiographic characteristics of the vein of Marshall in patients with and without atrial fibrillation. J Clin Med. 2022; 11( 18): 5384. doi:10.3390/jcm11185384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Filippov AA , Del Nido PJ , Vasilyev NV . Management of systemic right ventricular failure in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2016; 134( 17): 1293– 302. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hudson RE . Surgical pathology of the conducting system of the heart. Heart. 1967; 29( 5): 646– 70. doi:10.1136/hrt.29.5.646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Connolly HM , Miranda WR , Egbe AC , Warnes CA . Management of the adult patient with congenitally corrected transposition: challenges and uncertainties. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2019; 22: 61– 5. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2019.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nederend M , Jongbloed MRM , Kiès P , Vliegen HW , Bouma BJ , Regeer MV , et al. Atrioventricular block necessitating chronic ventricular pacing after tricuspid valve surgery in patients with a systemic right ventricle: long-term follow-up. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 9: 870459. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.870459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Asagai S , Takeuchi D , Sugiyama H , Nagashima M . Successful staged tricuspid valve replacement following cardiac resynchronization therapy in a congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Clin Case Rep. 2019; 7( 8): 1484– 8. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Andersen HØ , de Leval MR , Tsang VT , Elliott MJ , Anderson RH , Cook AC . Is complete heart block after surgical closure of ventricular septum defects still an issue? Ann Thorac Surg. 2006; 82( 3): 948– 56. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lin A , Mahle WT , Frias PA , Fischbach PS , Kogon BE , Kanter KR , et al. Early and delayed atrioventricular conduction block after routine surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010; 140( 1): 158– 60. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.12.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tucker EM , Pyles LA , Bass JL , Moller JH . Permanent pacemaker for atrioventricular conduction block after operative repair of perimembranous ventricular septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50( 12): 1196– 200. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Goldman BS , Williams WG , Hill T , Hesslein PS , McLaughlin PR , Trusler GA , et al. Permanent cardiac pacing after open heart surgery: congenital heart disease. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1985; 8( 5): 732– 9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.1985.tb05885.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Siehr SL , Hanley FL , Reddy VM , Miyake CY , Dubin AM . Incidence and risk factors of complete atrioventricular block after operative ventricular septal defect repair. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014; 9( 3): 211– 5. doi:10.1111/chd.12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Anderson JB , Czosek RJ , Knilans TK , Meganathan K , Heaton P . Postoperative heart block in children with common forms of congenital heart disease: results from the KID database. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23( 12): 1349– 54. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02385.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Fortescue EB , Berul CI , Cecchin F , Walsh EP , Triedman JK , Alexander ME . Patient, procedural, and hardware factors associated with pacemaker lead failures in pediatrics and congenital heart disease. Heart Rhythm. 2004; 1( 2): 150– 9. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.02.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tantengco MV , Thomas RL , Karpawich PP . Left ventricular dysfunction after long-term right ventricular apical pacing in the young. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37( 8): 2093– 100. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01302-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dreger H , Maethner K , Bondke H , Baumann G , Melzer C . Pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with right ventricular stimulation for >15 years. Europace. 2012; 14( 2): 238– 42. doi:10.1093/europace/eur258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Merchant FM , Hoskins MH , Musat DL , Prillinger JB , Roberts GJ , Nabutovsky Y , et al. Incidence and time course for developing heart failure with high-burden right ventricular pacing. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017; 10( 6): e003564. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tayal B , Fruelund P , Sogaard P , Riahi S , Polcwiartek C , Atwater BD , et al. Incidence of heart failure after pacemaker implantation: a nationwide Danish registry-based follow-up study. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40( 44): 3641– 8. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yeo WT , Jarman JWE , Li W , Gatzoulis MA , Wong T . Adverse impact of chronic subpulmonary left ventricular pacing on systemic right ventricular function in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 171( 2): 184– 91. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Glikson M , Nielsen JC , Kronborg MB , Michowitz Y , Auricchio A , Barbash IM , et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2022; 24( 1): 71– 164. doi:10.1093/europace/euab232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Russo AM , Desai MY , Do MM , Butler J , Chung MK , Epstein AE , et al. ACC/AHA/ASE/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2025 appropriate use criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization therapy, and pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025; 85( 11): 1213– 85. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.11.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Šimka J , Sedláček K , Praus R , Pařízek P . A case report of upgrading to cardiac resynchronization therapy in a patient with congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries and dextrocardia. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2023; 7( 9): 1– 6. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytad426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Cecchin F , Frangini PA , Brown DW , Fynn-Thompson F , Alexander ME , Triedman JK , et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (and multisite pacing) in pediatrics and congenital heart disease: five years experience in a single institution. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009; 20( 1): 58– 65. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01274.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chubb H , Rosenthal DN , Almond CS , Ceresnak SR , Motonaga KS , Arunamata AA , et al. Impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy on heart transplant-free survival in pediatric and congenital heart disease patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020; 13( 4): e007925. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Nederend M , van Erven L , Zeppenfeld K , Vliegen HW , Egorova AD . Failing systemic right ventricle in a patient with dextrocardia and complex congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: a case report of successful transvenous cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021; 5( 4): 1– 7. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytab068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Baba S , Miyazaki A , Watanabe T , Shiraishi S , Saitoh A . Cardiac resynchronization therapy by pacing the right ventricular dorsal site of inflow and anterior outflow for congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2024; 8( 12): 1– 7. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytae607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jauvert G , Rousseau-Paziaud J , Villain E , Iserin L , Hidden-Lucet F , Ladouceur M , et al. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on echocardiographic indices, functional capacity, and clinical outcomes of patients with a systemic right ventricle. Europace. 2009; 11( 2): 184– 90. doi:10.1093/europace/eun319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Janousek J , Tomek V , Chaloupecký VA , Reich O , Gebauer RA , Kautzner J , et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: a novel adjunct to the treatment and prevention of systemic right ventricular failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44( 9): 1927– 31. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Cowburn PJ , Parker JD , Cameron DA , Harris L . Cardiac resynchronization therapy: retiming the failing right ventricle. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005; 16( 4): 439– 43. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40590.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chinese Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, Chinese Society of Arrhythmias . Chinese expert consensus on His-Purkinje conduction system pacing. Chin J Card Arrhyth. 2021; 25( 1): 10– 6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

57. Takemoto M , Nakashima A , Muneuchi J , Yamamura KI , Shiokawa Y , Sunagawa K , et al. Para-Hisian pacing for a pediatric patient with a congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (SLL). Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010; 33( 1): e4– 7. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02559.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Vijayaraman P , Mascarenhas V . Three-dimensional mapping-guided permanent His bundle pacing in a patient with corrected transposition of great arteries. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2019; 5( 12): 600– 2. doi:10.1016/j.hrcr.2019.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Nam MCY , Grigg L , Stevenson I . Left bundle branch area pacing in congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries—the obvious choice? J Electrocardiol. 2021; 66: 77– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2021.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Jiang H , Hou X , Qian Z , Wang Y , Tang L , Qiu Y , et al. A novel 9-partition method using fluoroscopic images for guiding left bundle branch pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17( 10): 1759– 67. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Yang Z , Tao J , Fan X , Feng Z , Liu Z . Comparison of clinical outcomes between transthoracic echocardiography- and X-ray-guided left bundle branch pacing for bradycardia: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2024; 35( 5): 875– 82. doi:10.1111/jce.16212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools