Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Comprehensive Brain MRI and Neurodevelopmental Dataset in Children with Tetralogy of Fallot

1 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210008, China

2 Nanjing Children’s Hospital, Clinical Teaching Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210008, China

3 Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210008, China

4 College of Artificial Intelligence, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Jiangning District, Nanjing, 211106, China

5 State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine and Offspring Health,Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210008, China

* Corresponding Author: Xuming Mo. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work as joint the first author

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 559-570. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.072242

Received 22 August 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Background: The life-course management of children with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) has focused on demonstrating brain structural alterations, developmental trajectories, and cognition-related changes that unfold over time. Methods: We introduce an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) dataset comprising TOF children who underwent brain MRI scanning and cross-sectional neurocognitive follow-up. The dataset includes brain three-dimensional T1-weighted imaging (3D-T1WI), three-dimensional T2-weighted imaging (3D-T2WI), and neurodevelopmental evaluations using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV). Results: Thirty-one children with TOF (age range: 4–33 months; 18 males) were recruited and completed corrective surgery at the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China. Aiming to promote the neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with TOF, we have meticulously curated a comprehensive dataset designed to dissect the complex interplay among risk factors, neuroimaging findings, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Conclusion: This article aims to introduce our open-source dataset on neurodevelopment in children with TOF, which covers the data types, data acquisition and processing methods, the procedure for accessing the data, and related publications.Keywords

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects worldwide, with an incidence rate of approximately 9.41 per 1000 births. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic congenital heart disease (CCHD) in Asia, accounting for 7–10% of CHD [1]. Over the past decade, advances in surgical techniques for CHD have enabled an increasing number of children with TOF to reach adulthood and even geriatrics [2]. Studies have found that 50% of children with CCHD may experience neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) at different stages of their life cycles [3]. The primary manifestations include cognitive and attentional impairments [4,5], motor and communication deficits [6,7], as well as delays in executive function [8]. These symptoms can emerge as early as infancy and may persist through adolescence and beyond [9,10]. There has been increased focus on the NDDs and mental health of patients with these conditions [11]. The American Heart Association has identified addressing neurodevelopmental dysfunction in children with CHD as one of the most critical challenges of the 21st century [12]. Therefore, the identification and intervention of NDDs become particularly crucial. The relationship between risk factors, imaging findings, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with TOF remains a significant unresolved issue. Therefore, we have established this dataset to provide support for improving their neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes in children with CHD are closely associated with NDDs. These changes are currently known to be related to chronic preoperative cerebral hypoxia, perioperative inflammatory responses, intraoperative reperfusion, and rapid changes in body temperature leading to brain injury [8,13]. During the perioperative period, children experience significant hemodynamic alterations due to anesthesia and surgery, which may represent a critical window for intervention. Advancements in neuroimaging technology have broadened our understanding of NDDs in the context of CCHD. The common risk factors are concentrated in the perioperative period, mainly including cardiopulmonary bypass, cerebral perfusion during bypass [14], postoperative arrhythmias, low cardiac output, and prolonged mechanical respiratory support [15,16,17]. These factors are all associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, but the specific mechanisms remain unclear. Total brain volume, white matter volume, cortical volume, and deep gray matter volume are smaller in patients with CCHD [18,19]. Structural MRI studies have detected a correlation between larger hippocampal volume and better memory in children with CCHD [20]. Additionally, symmetry of brain sulci and increased brain volume are associated with better neurodevelopmental outcomes in adolescents with CCHD, including intelligence quotient (IQ), executive function, and attention [21,22,23,24]. Compared to structural brain abnormalities, the relationship between microstructural changes in the brains of children with CCHD and functional outcomes is more consistent. Early alterations in brain structure and function may arise from subsequent remodeling of microstructural integrity and functional network organization [25]. However, neuroimaging findings remain fragmented across the research. In addition, the complete pattern of brain changes and developmental trajectories in children with TOF remain unclear. These findings are hard to integrate into detailed mechanistic research or routine clinical practice., necessitating long-term developmental monitoring and follow-up. Therefore, establishing a dataset that includes imaging and clinical information is crucial for the prediction and early diagnosis of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Here, we introduce a comprehensive knowledgebase pertaining to children with TOF, which addresses the paucity of CHD neurodevelopmental databases within the international scientific community. The dataset is intended to facilitate the prediction and early auxiliary diagnosis of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes, enable researchers to replicate previous findings, and provide an empirical basis for mapping the evolving structural and functional trajectories of the developing brain in TOF children. Moreover, it serves as a small-sample benchmark for artificial intelligence algorithms in children with TOF, thereby promoting algorithm optimization and external validation.

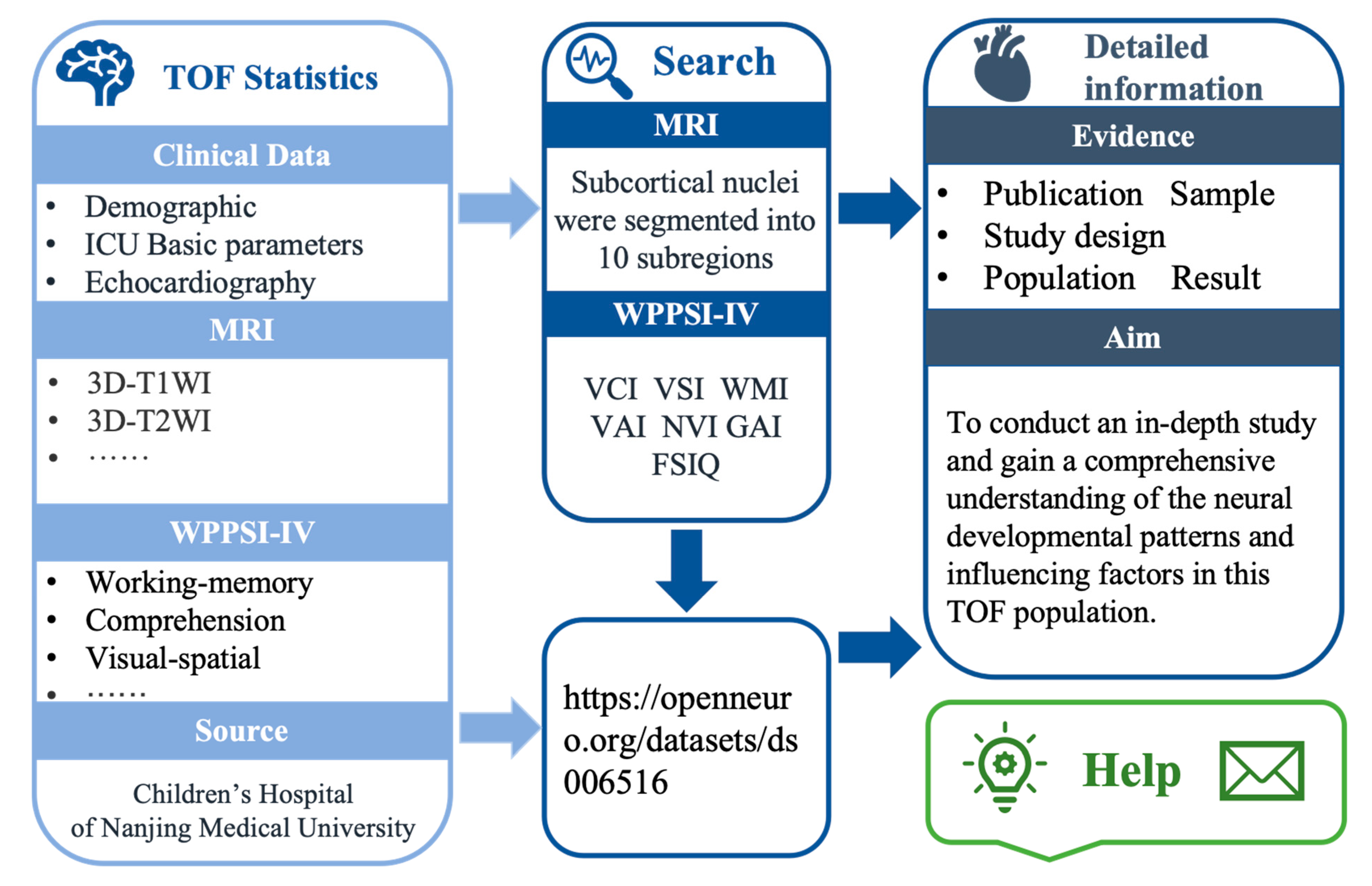

The aim of our study is to build a representative, multidimensional dataset focusing on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with TOF following surgical intervention. Our dataset is single-center, covering children with TOF who underwent surgery between 2019 and 2023 at the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Children with TOF are at a higher risk for NDDs. Our long-term goal is to expand this dataset to cover a broader population and geographic area to better understand the impact of TOF on neurodevelopment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Overview of the framework of CHDbase. TOF, Tetralogy of Fallot; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging; WPPSI-IV, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Fourth Edition; VCI, verbal comprehension index; VSI, visual-spatial index; WMI, working memory index; VAI, vocabulary acquisition index; NVI, non-verbal index; GAI, general ability index.

Thirty-one children (18 males, aged 4 to 33 months) recruited for the study were admitted for treatment at the Cardiac Center of the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from January 2019 to December 2023. The inclusion criteria are as follows: children aged 0–3 years with a confirmed diagnosis of TOF who underwent corrective surgery and completed scheduled postoperative neurodevelopmental assessments. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Presence of diseases in other organs/systems; (2) History of traumatic brain injury or prior use of psychotropic medications; (3) Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgeries performed after the age of three years; (4) Incomplete corrective surgery for TOF; (5) Inability to meet the requirements for the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV) testing; and (6) Loss to follow-up. All children with TOF underwent neurodevelopmental assessments and brain MRI scans during postoperative follow-up. All data collected were meticulously cross-verified with the information provided by the caregivers of the participants to ensure accuracy.

2.3 Clinical and Demographic Metrics

The data collection process encompassed multiple facets that could potentially influence neurodevelopmental outcomes. Key clinical variables extracted from electronic medical records included: age, male, preoperative resting oxygen saturation, history of hypoxic spells, and degree of cyanosis. Body mass index, McGoon index, aortic override, pulse oxygen saturation, ventricular septal defect (VSD), CPB time, aortic cross-clamp time, and duration of hospital stay, were extracted from electronic medical records. Questionnaires were used to assess maternal education and family annual income, as these factors are known to influence neurodevelopment.

3 Neurodevelopmental Assessment

Children with TOF underwent a neurodevelopmental assessment of WPPSI-IV after discharge from the hospital. The WPPSI-IV testing was conducted by specifically trained personnel. Testing was carried out by two examiners, one administering and one observing, while parents waited outside. The assessors were professionally trained and qualified to conduct this evaluation. After a 5-min acclimation period in a standardized room, each child was assessed using the age-appropriate record form. Brief rapport and comfort checks (e.g., hunger, discomfort) were performed before testing began. According to the participant’s age, two different scoring books were applied: one for children aged 2 years 6 months to 3 years 11 months, and the other for those aged 4 years to 6 years 11 months. Younger children (aged 2 years 6 months to 3 years 11 months) completed seven subtests. Results yielded the full-scale IQ (FSIQ) along with three primary composite scores—verbal comprehension index (VCI), visual-spatial index (VSI), and working memory index (WMI)—and three ancillary composite scores: vocabulary acquisition index (VAI), non-verbal index (NVI), and general ability index (GAI). Older children (aged 4 years to 6 years 11 months) completed thirteen subtests. From these, the fluid reasoning index (FRI) and processing speed index (PSI) were added as primary composite scores, and the cognitive efficiency index (CEI) was also derived as an ancillary composite score.

All raw scores from the subtests were converted to standardized scores based on the age-specific norms provided in the WPPSI-IV manual. The primary outcome metric was the FSIQ, which has a population mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The primary index scores were also analyzed to identify potential domain-specific cognitive weaknesses. According to the test’s standardized classification system:

Scores ≥90 are classified as Average to High Average.

Scores between 80–89 are classified as Low Average.

Scores between 70–79 are classified as Borderline.

Scores ≤69 are classified as Extremely Low.

3.1 MRI Acquisition and Processing

Philips Ingenia 3.0T MR (Ingenia 3.0, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) scanner, head 16-channel coil, with parental consent, Children < 3 years old were sedated with 5% chloral hydrate (1 mL/kg) 20 min before scanning, and earplugs and foam were used to reduce scanning noise and head movement noise, respectively, after sleeping. Scanning sequence: three-dimensional T1-weighted (3D-T1WI) images high-resolution structural image (ultra-fast gradient Echo sequence): TE = 3.5 ms, TR = 7.9 ms, FOV = 200 × 200 × 200 mm, slice thickness 1 mm, acquisition time = 4 min 24 s; Axial three-dimensional T2-weighted (3D-T2WI) (fast spin echo): TE = 110 ms, TR = 4000 ms, FOV = 200 × 200 × 119 mm, section thickness 5 mm, acquisition time = 1 min 28 s; Two experienced pediatric neuroradiologists, blinded to each participant’s medical history, independently reviewed all images. In cases where there was a difference of opinion, a consensus was reached through discussion.

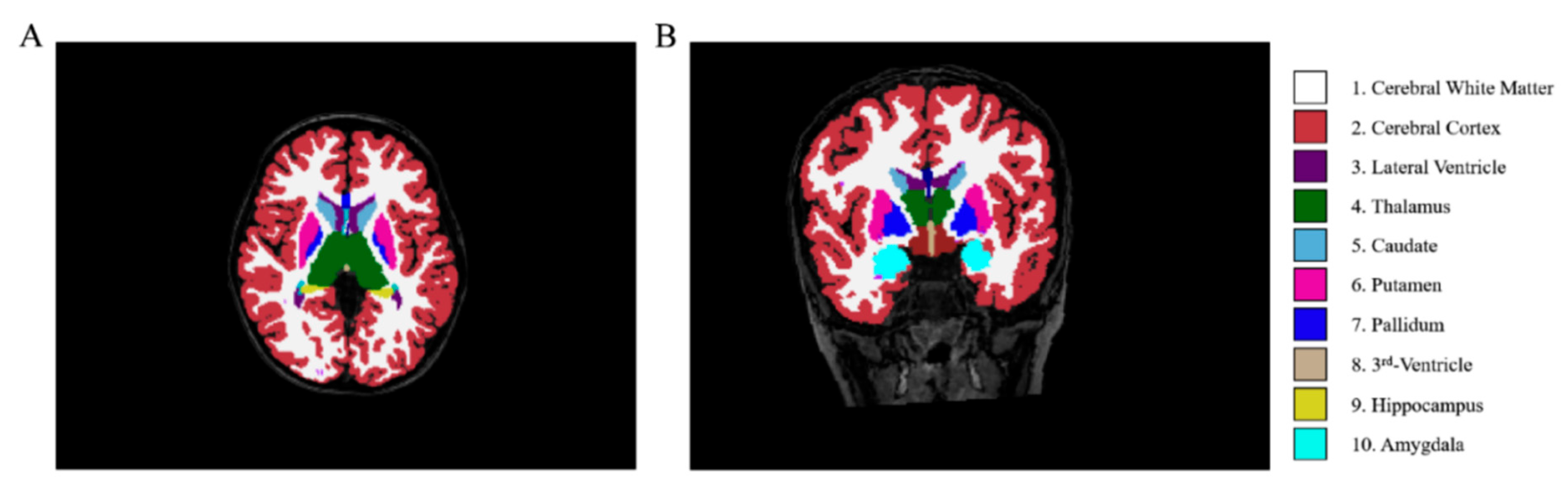

3D-T1WI images were processed with FreeSurfer v6.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu, accessed on 22 August 2025) using the automated recon-all pipeline, and the quality of the preprocessed images was verified. The subcortical nuclei were segmented into 7 subregions (Fig. 2): left thalamus proper nucleus (LTHA), left amygdala nucleus (LAM), right thalamus proper nucleus (RTHA), right caudate nucleus (RCAU), right putamen nucleus (RPU), right pallidum nucleus (RPA), and right amygdala nucleus (RAM).

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of brain region segmentation results processed by FreeSurfer. (A) (axial view) and (B) (coronal view) display a 3D T1-weighted MRI scan with segmented subcortical structures. The color codes are as follows: cerebral white matter (1), cerebral cortex (2), lateral ventricle (3), thalamus (4), caudate (5), putamen (6), pallidum (7), third ventricle (8), hippocampus (9), and amygdala (10).; Note: Adapted from Ref. [19].

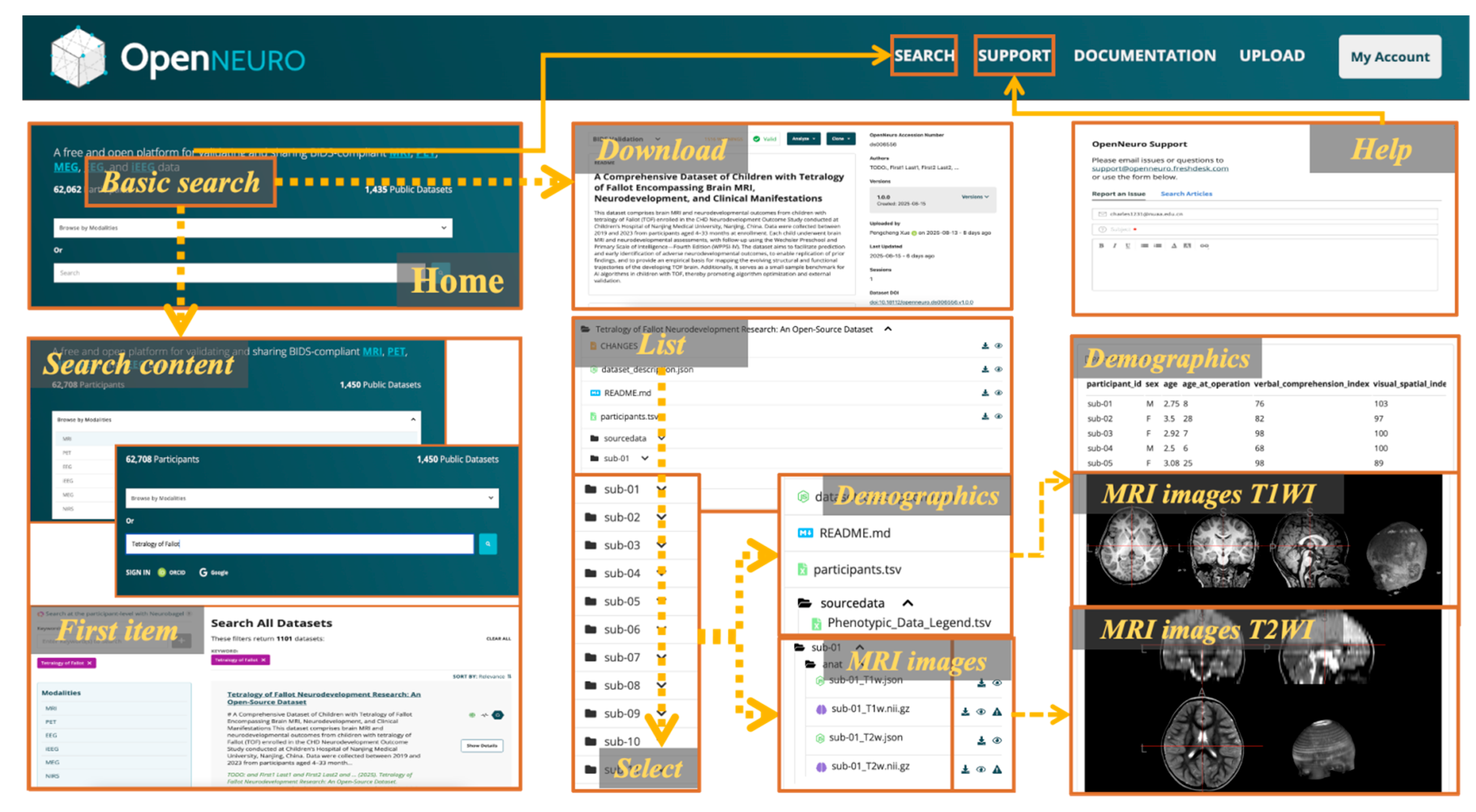

The dataset is available at Open Neuro (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds006556, accessed on 22 August 2025). The database comprises neurodevelopmental data from 31 children who have undergone surgery for TOF. To protect participant privacy, all data were de-identified prior to analysis. Personal identifying information was removed, and data were anonymized to ensure that no individual could be identified. The “DATA” folder contains 31 subfolders labeled with de-identified participant ID numbers (e.g., sub-01, sub-02). Each folder contains subfolders labeled “anat” which include T1WI and T2WI structural images. The T1WI and T2WI imaging data of each subject are stored in NIfTI format (.nii.gz), while the corresponding metadata are stored in JSON format (.json). We have provided a flowchart for data download, facilitating quick access to the data for users (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The web interface of OpenNeuro TOF dataset. The major components of the web interface of OpenNeuro are shown.

Table 1 exhibits the individual and clinical characteristics of children with TOF. A total of 31 children with TOF were enrolled (age 4–33 months; 18 males). Assessment of preoperative hypoxia status revealed that no patient had a history of hypoxic spells. The median preoperative resting oxygen saturation was 100% (98%, 100%). The median hospital stay was 26 (20, 29) days, and the McGoon index was 1.71 ± 0.33. Table 2 presents the specific numerical values measured by MRI for subcortical nuclei volume. The subcortical nuclei volumes were segmented into the basal ganglia (caudate: 3491.20 ± 409.66 mm3, putamen: 4915.39 ± 630.88 mm3, globus pallidus: 1658.21 ± 224.93 mm3), amygdala (left: 1294.87 ± 165.42 mm3, right: 1477.87 ± 179.84 mm3), and thalamus (left: 6811.93 ± 691.86 mm3, right: 6557.80 ± 750.39 mm3).

Table 1: Individual and Clinical Characteristics.

| Variables | TOF | Variables | TOF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of surgery, mon | 9 (7, 16) | Aortic override, % | 0.5 (0.5, 0.5) |

| Male, % | 18 (58%) | McGoon | 1.71 ± 0.33 |

| BMI | 15.87 ± 1.95 | Pre-RVOT-PG, mmHg | 66.39 ± 14.78 |

| Preoperative SpO2, % | 100 (98, 100) | Post-RVOT-PG, mmHg | 16 (12, 20) |

| Preoperative hypoxic spells, % | 0 | VT, mL | 81.55 ± 19.44 |

| Time of surgery, min | 185 (160, 220) | FiO2, % | 80 (80, 80) |

| Time of CPB, min | 75 (63, 90) | PEEP, cmH2O | 3 (3, 3) |

| Time of ACC, min | 54 (41, 67) | f, times per min | 25.65 ± 2.90 |

| Stay in ICU, day | 5 (4, 6) | Duration of ventilation, day | 5 (4, 6) |

| Stay in Hospital, day | 26 (20, 29) | HR, times per min | 157 (130, 168) |

| Height, cm | 97 (94, 110) | T, °C | 36.64 ± 0.32 |

| Weight, kg | 15 (14, 18) | Time of follow-up, mon | 35.56 ± 17.96 |

| Family annual income, thousand yuan per year | 6 (4, 10) | Age at neurodevelopment accessment, year | 3.5 (2.9, 5.1) |

| Parental education, year | 12 (9, 16) | SBP, mmHg | 87.35 ± 13.46 |

Table 2: Volume of subcortical nuclei in patients of TOF.

| Variables | TOF |

|---|---|

| LTHA, mm3 | 6811.93 ± 691.86 |

| LAM, mm3 | 1294.87 ± 165.42 |

| RTHA, mm3 | 6557.80 ± 750.39 |

| RCAU, mm3 | 3491.20 ± 409.66 |

| RPU, mm3 | 4915.39 ± 630.88 |

| RPA, mm3 | 1658.21 ± 224.93 |

| RAM, mm3 | 1477.87 ± 179.84 |

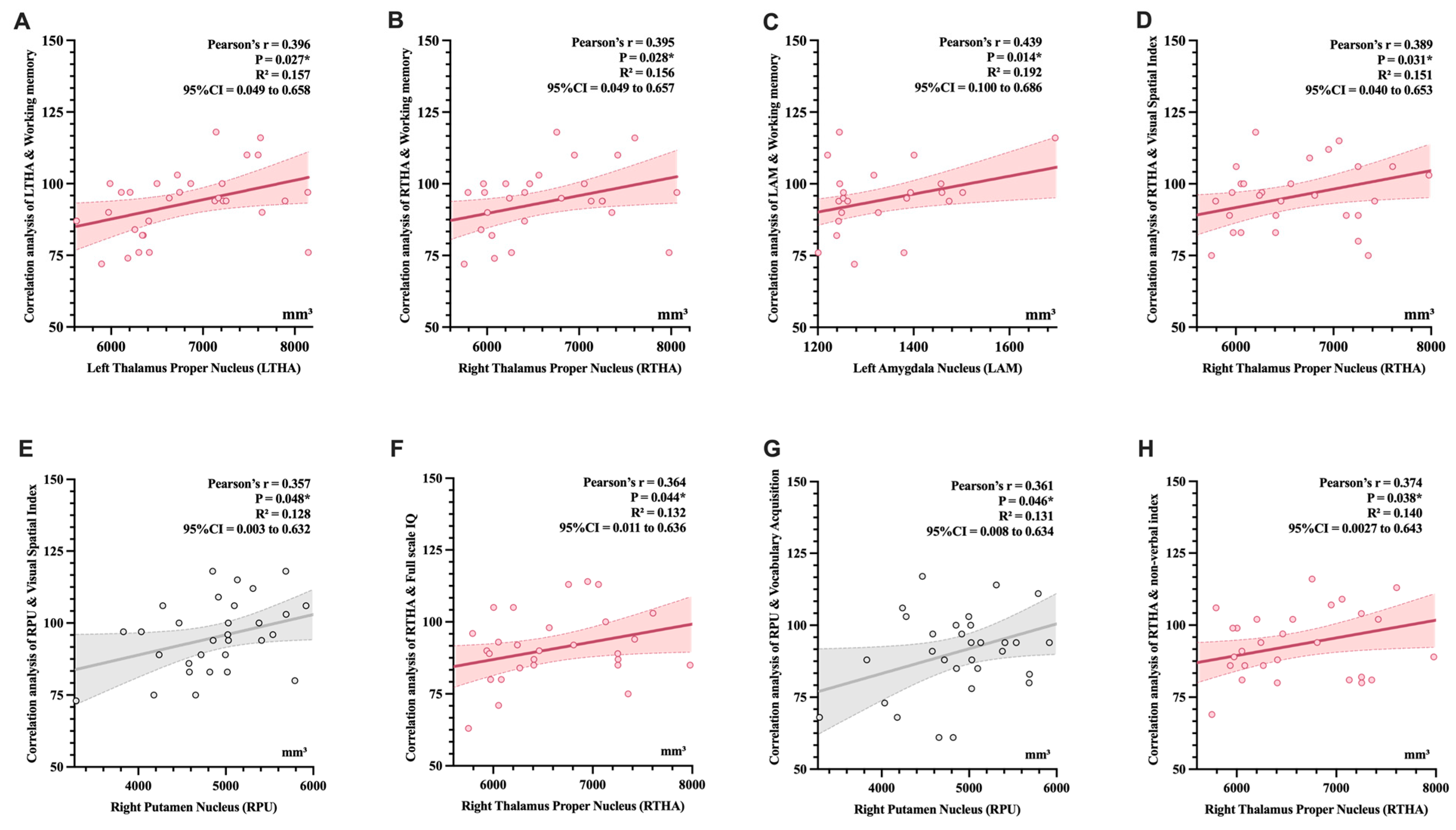

After a mean follow-up period of 35.56 ± 17.96 months, neurodevelopmental outcomes assessed by the WPPSI-IV scales covered seven domains: FSIQ (90.10 ± 12.35), VCI (87.32 ± 13.90), VSI (95.32 ± 12.41), WMI (93.13 ± 11.81), VAI (91.13 ± 15.07), NVI (92.87 ± 12.31), and GAI (90.35 ± 12.68) (Table 3). Preliminary correlation analyses revealed that LTHA (r = 0.389, p = 0.031), RTHA (r = 0.395, p = 0.028), LAM (r = 0.439, p = 0.014) were positively correlated with WMI. Positive correlations were also observed between RTHA (r = 0.389, p = 0.031) and RPU (r = 0.357, p = 0.048) with VSI, and between RTHA and FSIQ (r = 0.364, p = 0.044). Additionally, RPU was correlated with VAI (r = 0.361, p = 0.046), while RTHA showed a significant association with NVI (r = 0.374, p = 0.038) (Fig. 4).

Table 3: The WPPSI-IV results in patients of TOF.

| Variables | TOF |

|---|---|

| Verbal comprehension index | 87.32 ± 13.90 |

| Visual-spatial index | 95.32 ± 12.41 |

| Working memory index | 93.13 ± 11.81 |

| Full-scale IQ | 90.35 ± 12.68 |

| Vocabulary acquisition index | 91.13 ± 15.07 |

| Non-verbal index | 92.87 ± 12.31 |

| General ability index | 90.10 ± 12.35 |

Figure 4: Correlation analysis between subcortical nuclei subregions and domain scores of the WPPSI-IV. (A) LTHA & WMI; (B) RTHA & WMI; (C) LAM & WMI; (D) RTHA & VSI; (E) RPU & VSI; (F) RTHA & FSIQ; (G) RPU & VAI; (H) RTHA & NVI; Pearson correlation was used to analyze the associations. Gray indicates marginal significance, while pink represents statistical significance. We observed significant positive correlations between specific subcortical nuclei and WPPSI-IV domain scores. *indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

The long-term NDDs associated with CHD have been increasingly recognized over the past decade. However, several fundamental questions remain unanswered, including the mechanisms underlying NDDs, as well as limitations in long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up and assessment [26]. These unresolved issues hinder the application of current knowledge to clinical practice. In this study, we created the TOF Dataset, an evidence-based, manually curated knowledgebase for TOF, which links surgical and neurodevelopmental outcomes with brain MRI. Users can easily access MRI or clinical data for exploring the mechanism through our user-friendly data search interface. Thus, the TOF dataset provides a “one-stop” solution, offering a comprehensive landscape of TOF clinical data, MRI images, and cognitive evaluations.

TOF is the most common subtype of CCHD. The anatomical abnormalities of TOF include VSD, overriding aorta, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and right ventricular hypertrophy. These features lead to abnormal hemodynamics, resulting in a range of ischemic and hypoxic manifestations [27]. Given the heightened susceptibility of brain tissue to ischemia and hypoxia, MRI has revealed a spectrum of injury-related alterations [28,29]. These alterations include reductions in whole-brain gray matter volume, white matter injury, microstructural abnormalities, abnormal sulcal and gyral patterns, and disrupted neural network connectivity [18,30,31,32]. Research indicates that white matter injury detected by MRI is significantly correlated with neurodevelopmental cognitive scores [25,33], while ischemic-hypoxic damage exerts a pronounced negative impact on FSIQ and motor performance metrics [34,35,36]. Consequently, children with TOF are predisposed to a range of NDDs, including impaired executive functioning, deficits in gross and fine motor skills, and language impairments [36,37,38]. The precise pathogenic mechanisms underlying these deficits remain elusive, thereby constraining the scope of current interventional strategies, which primarily revolve around early surgical intervention, minimizing operative duration, and reducing the incidence of adverse events such as low cardiac output syndrome [39,40]. Therefore, elucidating the underlying mechanisms of NDDs in TOF and identifying reliable imaging biomarkers are pressing issues that need to be addressed to facilitate early clinical identification, diagnosis, and targeted intervention for NDDs.

At present, data for CHD are anchored by two international registries: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database and the European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association Congenital Cardiac Database, which rank as the largest and second-largest CHD surgical repositories worldwide, respectively. Collectively, they capture nearly all pediatric cardiac surgical centers in North America and Europe, stratifying cases by age group and benchmark procedure categories while systematically recording key performance indicators such as operative mortality and length of stay, with periodic dissemination of quality-improvement reports [41,42]. In the imaging field, the publicly available Whole-Heart Segmentation in Congenital Heart Disease-2.0 database provides 3D cardiovascular magnetic resonance whole-heart segmentations specifically curated for CHD, serving as a critical resource for algorithm development and validation [43]. Although several centers have released brain MRI datasets in children with CHD [44,45], these resources have yet to be integrated into a systematic, large-scale repository.

Given the impact of TOF on children’s neurodevelopment, establishing a “TOF Neurodevelopmental Imaging Dataset” is particularly important. The main purpose of this dataset is to integrate and make public the neurodevelopmental imaging data and related metadata of patients with TOF, aiming to provide a data sharing and communication platform for scholars in the field of congenital heart disease neurodevelopmental research worldwide. The significance of launching this open-source dataset by our center lies in promoting global research and collaboration. By providing a centralized data resource, we aim to accelerate the exploration of the mechanisms by which CHD affects children’s neurodevelopment. This research lays the groundwork for further development of customized treatments for congenital heart disease, improving the quality of life for affected children.

Our dataset has some limitations. Firstly, as a single-center dataset, the relatively small sample size limits generalizability to the broader TOF population and introduces potential selection bias. Furthermore, the fact that none of the children in our cohort experienced preoperative hypoxic spells suggests that our sample may not be fully representative of the entire TOF population, which includes patients with a history of such events. Secondly, imaging and cognition assessments require prolonged follow-up; early attrition at different time-points compromises data continuity. Although the WPPSI-IV was administered, the precise timing of neurodevelopment change could not be determined. Moreover, neurodevelopment is shaped by genetic, environmental, and socio-economic factors that are not fully captured, restricting interpretability. Finally, at the end of follow up, the oldest participant with TOF was 6 years old, whereas published series have reported follow-up to 16 years (non-contiguous) [46]. Therefore, ongoing longitudinal surveillance is essential to delineate long-term neurodevelopment outcomes and to generate a dynamic brain-development atlas for TOF. Consequently, the dataset will be updated regularly and maintained under version control to allow full traceability of historical data.

This dataset is intended for researchers interested in exploring the relationship between neurodevelopment and the long-term hypoxia and risk factors associated with TOF. It includes clinical variables and imaging data from 31 cases of TOF during the perioperative period, collected by cardiothoracic surgeons and radiologists from a center that has been dedicated to studying neurodevelopment over a span of six years. Our previous research has confirmed that chronic hypoxia can lead to changes in brain volume, which is related to cognition and other factors. Children with TOF are relatively few in number, making this data suitable for multi-center analysis. We have previously analyzed a fraction of this dataset in earlier work.

Please be advised that this dataset is derived from a single study with a limited sample size (n = 31). Consequently, the findings may have limited generalizability across diverse populations or settings. The dataset is publicly available on the Open Neuro platform. Users should acknowledge the original authors’ contributions. Appropriate citation of this paper is required when using this dataset. We hope this resource will contribute to elucidating the relationship between neurodevelopment and long-term hypoxia and risk factors in TOF.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270310), Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2024ZD0527000 and No. 2024ZD0527005), Jiangsu Provincial key research and development program (BE2023662), General project of Nanjing Health Commission (YKK22166).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Yang Xu and Yaqi Zhang contributed equally to this manuscript. Yang Xu, Yaqi Zhang and Xuming Mo: conceived the project. Yang Xu and Yaqi Zhang: wrote the manuscript text and prepared figures and tables. Meijiao Zhu and Ming Yang: provided MRI images and performed preprocessing. Pengcheng Xue: uploaded the data and carried out subsequent version updates. Siyu Ma, Di Yu, Liang Hu and Yuxi Zhang: critically revising the work for intellectual content. Wei Peng, Jirong Qi, Xuyun Wen, Xuming Mo: gave approval of the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All datasets mentioned in the article are publicly available on OpenNeuro (https://openneuro.org) under a CC0 1.0 Universal license. The data may be downloaded free of charge and reused without restriction, provided that this paper is cited.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and National research Committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board in Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and the approval number is 202507014-1 and informed consent was acquired. Long-term data updates and access can be obtained by visiting https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds006556 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Aortic Cross-Clamp | |

| Body Mass Index | |

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass | |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | |

| Frequency | |

| Full-scale IQ | |

| General ability index | |

| Heart Rate | |

| Intensive Care Unit | |

| Left Amygdala Nucleus | |

| Left Thalamus Proper Nucleus | |

| Non-verbal index | |

| Postoperative pressure in the right ventricular outflow tract | |

| Preoperative pressure gradient in the right ventricular outflow tract | |

| Wechsler Pre-school and Primary School Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition | |

| Right Amygdala Nucleus | |

| Right Caudate Nucleus | |

| Right Pallidum Nucleus | |

| Right Putamen Nucleus | |

| Right Thalamus Proper Nucleus | |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | |

| Temperature | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | |

| Vocabulary acquisition index | |

| Verbal comprehension index | |

| Ventricular Septal Defect | |

| Visual-spatial index | |

| Tidal Volume | |

| Working memory index |

References

1. Horenstein MS , Diaz-Frias J , Guillaume M . Tetralogy of fallot. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls; 2025. [Google Scholar]

2. Miller JR , Stephens EH , Goldstone AB , Glatz AC , Kane L , Van Arsdell GS , et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) 2022 Expert consensus document: management of infants and neonates with tetralogy of fallot. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023; 165( 1): 221– 50. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.07.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lee FT , Sun L , van Amerom JFP , Portnoy S , Marini D , Saini A , et al. Fetal hemodynamics, early survival, and neurodevelopment in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024; 83( 13): 1225– 39. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mebius MJ , Kooi EMW , Bilardo CM , Bos AF . Brain injury and neurodevelopmental outcome in congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017; 140( 1): e20164055. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Holst LM , Kronborg JB , Jepsen JRM , Christensen JO , Vejlstrup NG , Juul K , et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children with surgically corrected ventricular septal defect, transposition of the great arteries, and tetralogy of fallot. Cardiol Young. 2020; 30( 2): 180– 7. doi:10.1017/S1047951119003184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bolduc ME , Dionne E , Gagnon I , Rennick JE , Majnemer A , Brossard-Racine M . Motor impairment in children with congenital heart defects: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2020; 146( 6): e20200083. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-0083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sprong MCA , Broeders W , van der Net J , Breur J , de Vries LS , Slieker MG , et al. Motor developmental delay after cardiac surgery in children with a critical congenital heart defect: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2021; 33( 4): 186– 97. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zampi JD , Ilardi DL , McCracken CE , Zhang Y , Glatz AC , Goldstein BH , et al. Comparing parent perception of neurodevelopment after primary versus staged repair of neonatal symptomatic tetralogy of fallot. J Pediatr. 2025; 276: 114357. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sun L , van Amerom JFP , Marini D , Portnoy S , Lee FT , Saini BS , et al. MRI Characterization of hemodynamic patterns of human fetuses with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021; 58( 6): 824– 36. doi:10.1002/uog.23707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sajid A , Chavez-Valdez R , Sharp AN , Shah DK . Neurodevelopment in congenital heart disease: a review of antenatal mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Pediatr Res. 2025. doi:10.1038/s41390-025-04360-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Woo JP , McElhinney DB , Lui GK . The challenges of an aging tetralogy of Fallot population. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2021; 19( 7): 581– 93. doi:10.1080/14779072.2021.1940960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Marino BS , Lipkin PH , Newburger JW , Peacock G , Gerdes M , Gaynor JW , et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012; 126( 9): 1143– 72. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sadhwani A , Wypij D , Rofeberg V , Gholipour A , Mittleman M , Rohde J , et al. Fetal brain volume predicts neurodevelopment in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2022; 145( 15): 1108– 19. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bonthrone AF , Stegeman R , Feldmann M , Claessens NHP , Nijman M , Jansen NJG , et al. Risk factors for perioperative brain lesions in infants with congenital heart disease: a european collaboration. Stroke. 2022; 53( 12): 3652– 61. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.039492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Faerber JA , Huang J , Zhang X , Song L , DeCost G , Mascio CE , et al. Identifying risk factors for complicated post-operative course in tetralogy of fallot using a machine learning approach. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8: 685855. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.685855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Leon RL , Mir IN , Herrera CL , Sharma K , Spong CY , Twickler DM , et al. Neuroplacentology in congenital heart disease: placental connections to neurodevelopmental outcomes. Pediatr Res. 2022; 91( 4): 787– 94. doi:10.1038/s41390-021-01521-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. O’Byrne ML , DeCost G , Katcoff H , Savla JJ , Chang J , Goldmuntz E , et al. Resource utilization in the first 2 years following operative correction for tetralogy of fallot: study using data from the Optum’s de-identified clinformatics data mart insurance claims database. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020; 9( 15): e016581. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.016581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. von Rhein M , Buchmann A , Hagmann C , Huber R , Klaver P , Knirsch W , et al. Brain volumes predict neurodevelopment in adolescents after surgery for congenital heart disease. Brain. 2014; 137( Pt 1): 268– 76. doi:10.1093/brain/awt322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hu L , Wu K , Li H , Zhu M , Zhang Y , Fu M , et al. Association between subcortical nuclei volume changes and cognition in preschool-aged children with tetralogy of Fallot after corrective surgery: a cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr. 2024; 50( 1): 189. doi:10.1186/s13052-024-01764-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Muñoz-López M , Hoskote A , Chadwick MJ , Dzieciol AM , Gadian DG , Chong K , et al. Hippocampal damage and memory impairment in congenital cyanotic heart disease. Hippocampus. 2017; 27( 4): 417– 24. doi:10.1002/hipo.22700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Heinrichs AK , Holschen A , Krings T , Messmer BJ , Schnitker R , Minkenberg R , et al. Neurologic and psycho-intellectual outcome related to structural brain imaging in adolescents and young adults after neonatal arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014; 148( 5): 2190– 9. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Morton SU , Maleyeff L , Wypij D , Yun HJ , Newburger JW , Bellinger DC , et al. Abnormal left-hemispheric sulcal patterns correlate with neurodevelopmental outcomes in subjects with single ventricular congenital heart disease. Cereb Cortex. 2020; 30( 2): 476– 87. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhz101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Verrall CE , Yang JYM , Chen J , Schembri A , d’Udekem Y , Zannino D , et al. Neurocognitive Dysfunction and smaller brain volumes in adolescents and adults with a Fontan circulation. Circulation. 2021; 143( 9): 878– 91. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pike NA , Roy B , Moye S , Cabrera-Mino C , Woo MA , Halnon NJ , et al. Reduced hippocampal volumes and memory deficits in adolescents with single ventricle heart disease. Brain Behav. 2021; 11( 2): e01977. doi:10.1002/brb3.1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Phillips K , Callaghan B , Rajagopalan V , Akram F , Newburger JW , Kasparian NA . Neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental outcomes among individuals with complex congenital heart disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023; 82( 23): 2225– 45. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang YS , Su XT , Ke L , He QH , Chang D , Nie J , et al. Initiating PeriCBD to probe perinatal influences on neurodevelopment during 3–10 years in China. Sci Data. 2024; 11( 1): 463. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-03211-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Loh TF , Ang YH , Wong YK , Tan HY . Fallot’s tetralogy–natural history. Singapore Med J. 1973; 14( 3): 169– 71. [Google Scholar]

28. Beca J , Gunn JK , Coleman L , Hope A , Reed PW , Hunt RW , et al. New white matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation. 2013; 127( 9): 971– 9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Dimitropoulos A , McQuillen PS , Sethi V , Moosa A , Chau V , Xu D , et al. Brain injury and development in newborns with critical congenital heart disease. Neurology. 2013; 81( 3): 241– 8. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfdcf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fontes K , Rohlicek CV , Saint‐Martin C , Gilbert G , Easson K , Majnemer A , et al. Hippocampal alterations and functional correlates in adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019; 40( 12): 3548– 60. doi:10.1002/hbm.24615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rollins CK , Watson CG , Asaro LA , Wypij D , Vajapeyam S , Bellinger DC , et al. White matter microstructure and cognition in adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2014; 165( 5): 936– 44.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kelly CJ , Christiaens D , Batalle D , Makropoulos A , Cordero‐Grande L , Steinweg JK , et al. Abnormal microstructural development of the cerebral cortex in neonates with congenital heart disease is associated with impaired cerebral oxygen delivery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8( 5): e009893. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.009893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Peyvandi S , Chau V , Guo T , Xu D , Glass HC , Synnes A , et al. Neonatal brain injury and timing of neurodevelopmental assessment in patients with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71( 18): 1986– 96. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wypij D , Newburger JW , Rappaport LA , J duPlessis A , Jonas RA , Wernovsky G , et al. The effect of duration of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in infant heart surgery on late neurodevelopment: the Boston circulatory arrest trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003; 126( 5): 1397– 403. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00940-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Newburger JW , Jonas RA , Soul J , Kussman BD , Bellinger DC , Laussen PC , et al. Randomized trial of hematocrit 25% versus 35% during hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in infant heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008; 135( 2): 347– 54.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Morton SU , Maleyeff L , Wypij D , Yun HJ , Rollins CK , Watson CG , et al. Abnormal right-hemispheric sulcal patterns correlate with executive function in adolescents with tetralogy of fallot. Cereb Cortex. 2021; 31( 10): 4670– 80. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhab114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hovels-Gurich HH , Bauer SB , Schnitker R , Willmes-von Hinckeldey K , Messmer BJ , Seghaye MC , et al. Long-term outcome of speech and language in children after corrective surgery for cyanotic or acyanotic cardiac defects in infancy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008; 12( 5): 378– 86. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Favilla E , Faerber JA , Hampton LE , Tam V , DeCost G , Ravishankar C , et al. Early evaluation and the effect of socioeconomic factors on neurodevelopment in infants with tetralogy of fallot. Pediatr Cardiol. 2021; 42( 3): 643– 53. doi:10.1007/s00246-020-02525-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lynch JM , Buckley EM , Schwab PJ , McCarthy AL , Winters ME , Busch DR , et al. Time to surgery and preoperative cerebral hemodynamics predict postoperative white matter injury in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014; 148( 5): 2181– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. LaRonde MP , Connor JA , Cerrato B , Chiloyan A , Lisanti AJ . Individualized family-centered developmental care for infants with congenital heart disease in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2022; 31( 1): e10– 9. doi:10.4037/ajcc2022124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kumar SR , Gaynor JW , Heuerman H , Mayer JE Jr , Nathan M , O’Brien JE Jr , et al. The Society of thoracic surgeons congenital heart surgery database: 2023 update on outcomes and research. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024; 117( 5): 904– 14. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Protopapas E , Padalino M , Tobota Z , Ebels T , Speggiorin S , Horer J , et al. The European congenital heart surgeons association congenital cardiac database: a 25-year summary of congenital heart surgery outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025; 67( 4): ezaf119. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaf119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Pace DF , Contreras HTM , Romanowicz J , Ghelani S , Rahaman I , Zhang Y , et al. HVSMR-2.0: A 3D cardiovascular MR dataset for whole-heart segmentation in congenital heart disease. Sci Data. 2024; 11( 1): 721. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-03469-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wilson S , Yun HJ , Sadhwani A , Feldman HA , Jeong S , Hart N , et al. Foetal cortical expansion is associated with neurodevelopmental outcome at 2-years in congenital heart disease: a longitudinal follow-up study. EBioMedicine. 2025; 114: 105679. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Steger C , Feldmann M , Borns J , Hagmann C , Latal B , Held U , et al. Neurometabolic changes in neonates with congenital heart defects and their relation to neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatr Res. 2023; 93( 6): 1642– 50. doi:10.1038/s41390-022-02253-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Cassidy AR , Newburger JW , Bellinger DC . Learning and memory in adolescents with critical biventricular congenital heart disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017; 23( 8): 627– 39. doi:10.1017/S1355617717000443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools