Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Interventional Treatment of Abnormal Veins Following Surgical Repair of Complex Congenital Heart Disease

1 Center of Structural Heart Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

2 Center of Pulmonary Vascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

* Corresponding Author: Haibo Hu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 673-682. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2026.069714

Received 29 June 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Background: During the surgical repair of complex congenital heart disease (CCHD), a subset of patients is unable to tolerate abrupt postoperative hemodynamic shifts, which can lead to significant complications. To mitigate this risk, certain abnormal venous channels are deliberately left open at the conclusion of surgery to provide a decompressive route, thereby reducing the likelihood of pulmonary hypertensive crises. Nevertheless, the continued patency of these vessels may induce chronic hemodynamic disturbances, often requiring subsequent treatment. This study was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of transcatheter intervention for such persistent anomalous systemic veins in CCHD patients following initial corrective operation. Methods: We performed a retrospective review of 14 CCHD patients who underwent transcatheter closure of residual anomalous systemic veins—including azygos, hemiazygos, and vertical veins—after prior corrective surgery at Fuwai Hospital from December 2007 to September 2019. Results: All procedures were completed successfully. Following closure of the azygos or hemiazygos veins, femoral arterial oxygen saturation increased significantly (SFAO2: 87.0 ± 2.7% vs. 75.1 ± 3.7%, p < 0.001). Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) rose slightly but statistically significantly post-intervention, although it remained within normal limits (12.3 ± 2.7 mmHg vs. 10.8 ± 3.3 mmHg, p = 0.027). In the two patients undergoing vertical vein closure, SFAO2 also improved markedly (Case 13: 98% vs. 86%; Case 14: 99% vs. 88%). Over a mean follow-up period of 26.3 ± 13.9 months, all patients remained clinically stable without major adverse events. Conclusions: Transcatheter closure of residual anomalous systemic veins after corrective surgery for CCHD is a safe and effective therapeutic option, associated with high procedural success and favorable short- to mid-term clinical outcomes.Keywords

The bidirectional Glenn procedure (BGP) is a standard palliative surgery for complex congenital heart disease (CCHD) in patients with single-ventricle physiology or those unsuitable for biventricular repair. This procedure involves anastomosing the superior vena cava directly to the ipsilateral pulmonary artery, thereby creating a passive cavopulmonary connection. By diverting systemic venous blood from the upper body to the lungs, the BGP increases pulmonary blood flow, enhances arterial oxygen saturation, and reduces ventricular volume load. It is primarily employed as an intermediate stage prior to definitive Fontan completion [1,2]. During the BGP, the azygos or hemiazygos vein is routinely ligated to prevent the development of systemic-to-pulmonary venous collaterals, which can cause intracardiac right-to-left shunting, thereby reducing effective pulmonary blood flow and arterial oxygen saturation. However, in patients with risk factors such as underdeveloped pulmonary arteries, elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, or high cavopulmonary pathway pressures, surgeons may elect to leave these veins patent. This intentional preservation serves as a “decompression pathway,” aiming to mitigate postoperative risks like pulmonary hypertensive crises and superior vena cava syndrome.

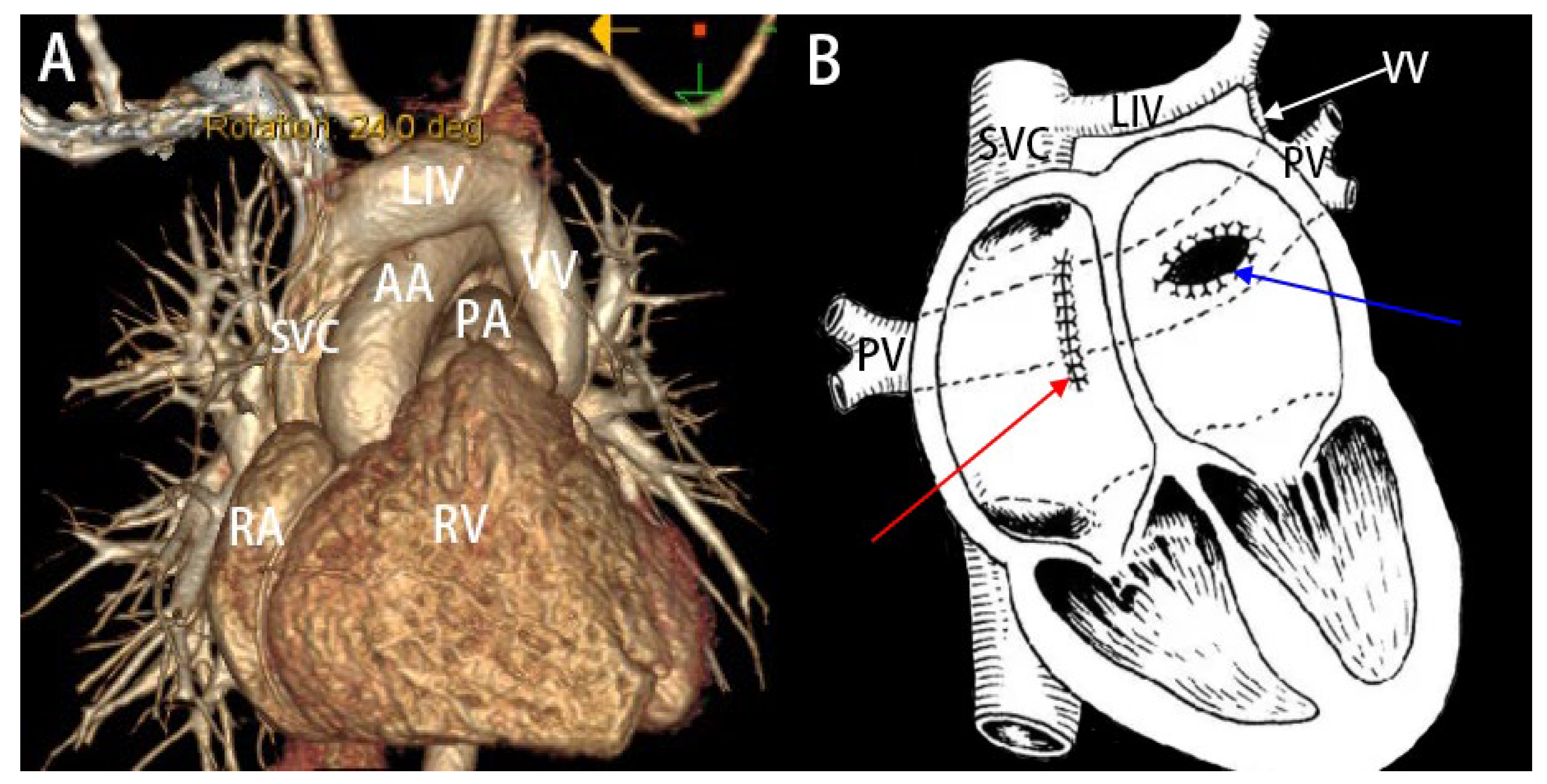

Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) is a congenital cardiovascular malformation in which the pulmonary veins drain anomalously into the right atrium or the systemic venous circulation rather than directly into the left atrium; it is frequently associated with an atrial septal defect (ASD) [3,4]. In the supracardiac type, the pulmonary veins converge posterior to the heart into a common venous trunk, which ascends via a vertical vein to drain into the left innominate vein and ultimately the superior vena cava (Fig. 1A). Surgical repair is indicated for all patients with TAPVC, urgently in obstructive forms. For supracardiac and infracardiac types, the procedure involves ligation of the vertical vein and creation of a wide anastomosis between the common pulmonary venous chamber and the left atrium to prevent postoperative stenosis. Finally, any concomitant atrial septal defect is closed, usually with a pericardial patch (Fig. 1B) [5]. However, many patients exhibit poor tolerance to the abrupt hemodynamic shifts following repair. To mitigate perioperative risks, particularly pulmonary hypertensive crisis, the vertical vein is often intentionally left patent as a “decompression pathway”.

Figure 1: (A): Three-dimensional CT reconstruction image of a patient with supracardiac TAPVC. (B): Schematic illustration of the surgical correction for supracardiac TAPVC. (1): Creation of an anastomosis between the common pulmonary vein trunk and the left atrium (indicated by the blue arrow). (2): Ligation of the VV (indicated by the white arrow). (3): Closure of the ASD (indicated by the red arrow). SVC: superior vena cava; LIV: left innominate vein; VV: vertical vein; AA: aortic arch; PA: pulmonary artery; PV: pulmonary vein; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle.

Nevertheless, long-term patency of this anomalous channel can result in persistent left-to-right shunting, leading to chronic arterial desaturation and hemodynamic compromise, thereby necessitating subsequent occlusion. To obviate the need for redo sternotomy, we performed transcatheter closure of such residual anomalous veins in 14 postoperative CCHD patients. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this interventional approach.

We retrospectively analyzed 14 consecutive CCHD patients who underwent transcatheter closure of residual shunts through anomalous systemic veins (azygos, hemiazygos, or vertical veins) at Fuwai Hospital between December 2007 and September 2019. The cohort comprised 9 males and 5 females, with a mean age of 15.4 ± 10.4 years (range: 6–41 years). Mean height and weight were 142.9 ± 22.4 cm and 35.3 ± 12.1 kg, respectively. Twelve patients had previously undergone a BGP for conditions including single ventricle and tetralogy of Fallot, and had subsequent residual shunts via the azygos or hemiazygos veins. The remaining two patients, with a history of TAPVC repair, presented with residual shunts via vertical veins. All patients were symptomatic, presenting with cyanosis, exertional dyspnea, and palpitations. Cardiac murmurs were audible on auscultation. Additionally, one patient (Case 11) reported hemoptysis, and another (Case 4) exhibited digital clubbing. According to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification, 79% of patients were class II and 21% were class III. Prior to the intervention, all patients underwent a standardized preoperative assessment, including a detailed history, physical examination, electrocardiography, chest radiography, computed tomography, transthoracic echocardiography, and diagnostic cardiac catheterization with angiography. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. 2021-1551). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1: The baseline characteristics of the 14 patients.

| Case | Sex | Age (year) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BP (mmHg) | NYHA | Venous Shunt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 11 | 125 | 23 | 128/96 | 2 | AV |

| 2 | M | 15 | 170 | 50 | 124/90 | 2 | AV |

| 3 | M | 8 | 120 | 21 | 96/78 | 3 | AV |

| 4 | M | 11 | 125 | 26 | 108/72 | 2 | AV |

| 5 | M | 15 | 165 | 37 | 90/65 | 2 | HV |

| 6 | F | 8 | 112 | 28 | 90/60 | 2 | AV |

| 7 | M | 9 | 113 | 26 | 85/94 | 2 | AV |

| 8 | F | 36 | 154 | 46 | 105/75 | 3 | AV |

| 9 | M | 17 | 172 | 52 | 143/72 | 2 | AV |

| 10 | F | 17 | 165 | 45 | 94/58 | 2 | AV |

| 11 | F | 13 | 157 | 36 | 102/48 | 3 | AV |

| 12 | M | 9 | 136 | 25 | 102/63 | 2 | AV |

| 13 | F | 41 | 160 | 55 | 158/107 | 2 | VV |

| 14 | M | 6 | 126 | 24 | 118/67 | 2 | VV |

All interventions were carried out under either local or general anesthesia. Femoral arterial oxygen saturation (SFAO2) and relevant hemodynamic parameters were recorded both before and immediately after device implantation to evaluate procedural effectiveness.

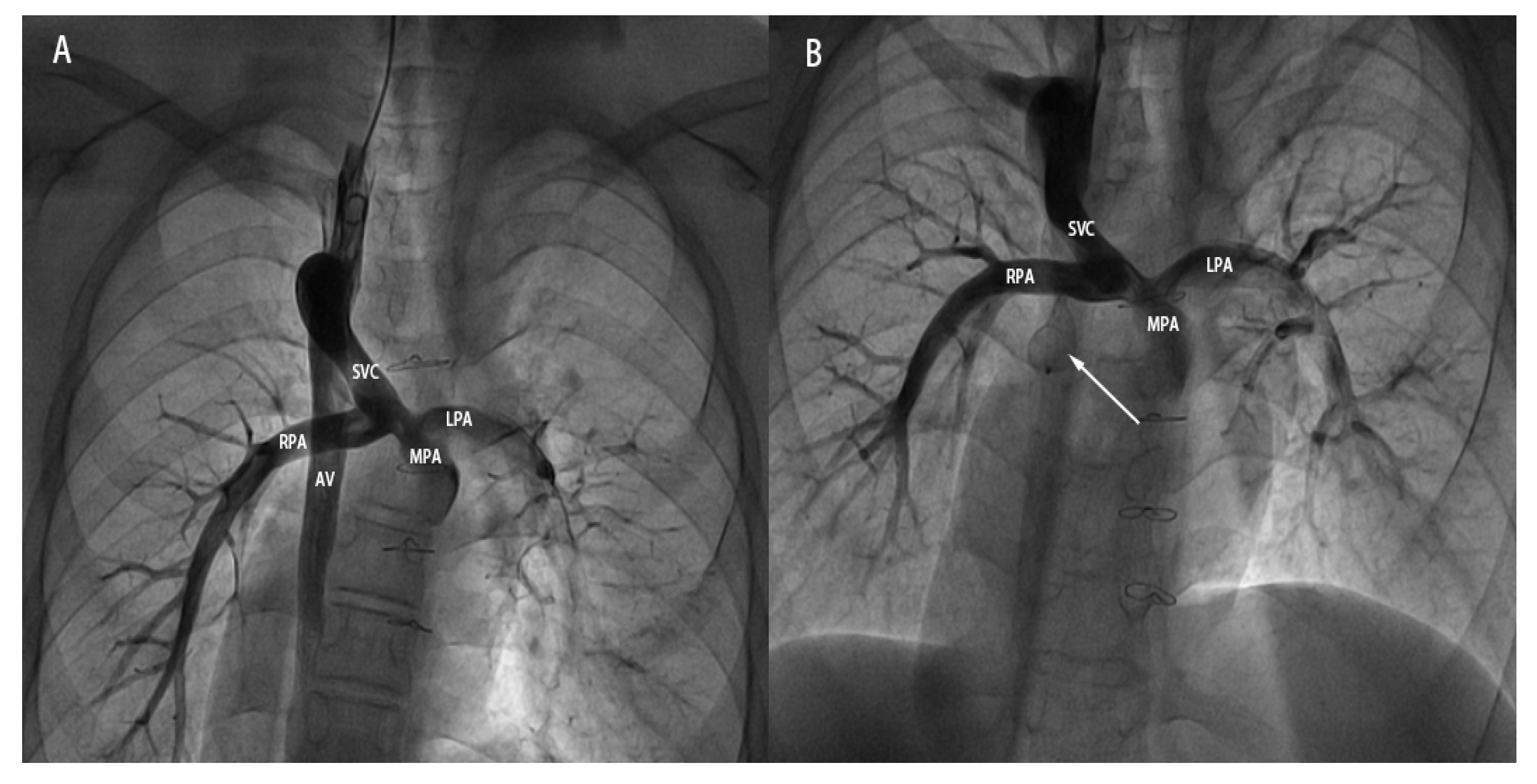

- (1)Case under local anesthesia: Vascular access was achieved via the right internal jugular vein. A 5-French pigtail catheter was introduced to perform angiography of the superior vena cava, pulmonary artery, and azygos vein (Fig. 2A). Through the same access route, a 16-mm atrial septal defect occluder was subsequently positioned and released to seal the proximal segment of the azygos vein. Post-deployment angiography verified complete occlusion, with no contrast filling observed in the mid- and distal portions of the vessel (Fig. 2B). The procedure concluded without any complications.

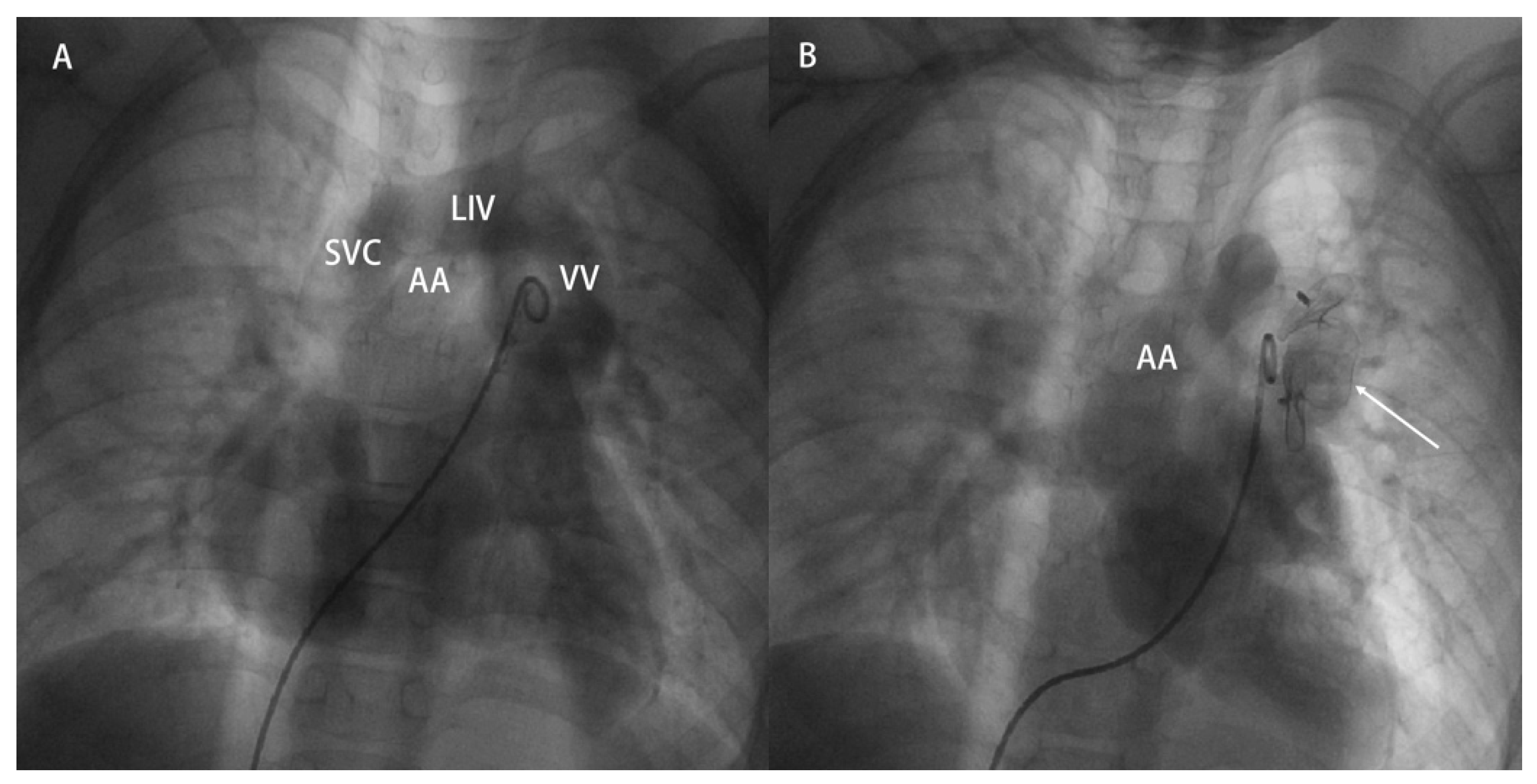

- (2)Case under general anesthesia: Access was obtained through the right femoral vein. Right-heart catheterization was performed using a 5-French pigtail catheter along with a 5-French side-hole catheter. Angiographic imaging delineated the pulmonary artery and the targeted vertical vein (Fig. 3A). A 22-mm vascular plug was then advanced along a pathway from the femoral vein through the superior vena cava and left innominate vein into the vertical vein, where it was deployed to occlude the distal segment of the vein. Post-occlusion pulmonary artery angiography confirmed total cessation of flow through the vertical vein (Fig. 3B). The intervention was completed uneventfully.

Figure 2: A 15-year-old male patient undergoing transcatheter closure of the dilated AV after BGP. (A): Pre-occlusion angiographic image showing the dilated AV originating from the SVC and draining downward. (B): Post-occlusion angiographic image showing the ASD occluder (indicated by the white arrow) in good shape and position, with no visualization of the middle and distal segments of the AV. SVC: superior vena cava; AV: azygos vein; MPA: main pulmonary artery; RPA: right pulmonary artery; LPA: left pulmonary artery.

Figure 3: A 6-year-old male patient who underwent percutaneous VV closure due to residual shunt after TAVPC correction. (A): Preoperative pulmonary angiography, recirculation showing VV injected through LIV into SVC. (B): Postoperative pulmonary angiography, recirculation showing the vascular plug shape and position are good (as indicated by the arrow), with no visualization of VV. SVC: superior vena cava; LIV: left innominate vein; VV: vertical vein; AA: aortic arch.

Patients underwent regular follow-up either in the outpatient clinic or via telephone after surgery. During follow-up visits, physical examinations were conducted, and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) was measured. Additional tests included electrocardiography, chest X-rays, and echocardiography.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 27.0). The normality of all continuous variables was assessed using appropriate tests. Normally or approximately normally distributed data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas data with a non-normal distribution are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR: P25, P75). Given the paired, within-subject design of this study, comparisons of pre- and post-occlusion parameters were performed using paired statistical tests. The paired t-test was applied if the differences between paired measurements followed a normal distribution; otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The significance level was set at 0.05 for both sides, with p < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant difference.

All targeted abnormal veins were successfully occluded. Immediate post-procedural assessment confirmed complete occlusion in 12 patients (86%), while two patients exhibited minor residual shunting. For azygos or hemiazygos vein occlusion, ASD occluders were utilized in the majority of cases, with PDA occluders employed in only two instances. Notable concomitant conditions addressed during the same procedure included preoperative cavopulmonary anastomosis stenosis (Case 3) and a pulmonary arteriovenous fistula (PAVF) (Case 9), both of which were successfully managed. Vertical veins were occluded using vascular plugs.

Occlusion of the azygos or hemiazygos veins resulted in a statistically significant increase in femoral arterial oxygen saturation (SFAO2: 87.0 ± 2.7% vs. 75.1 ± 3.7%, p < 0.001; mean difference: 12.0%, 95% CI: 9.3–14.3). Both mean and diastolic pulmonary arterial pressures (mPAP, dPAP) also showed small but statistically significant increases post-occlusion, though values remained within normal limits (mPAP: 12.3 ± 2.7 mmHg vs. 10.8 ± 3.3 mmHg, p = 0.027; mean difference: 1.6 mmHg, 95% CI: 0.2–3.0. dPAP: 10.3 ± 3.2 mmHg vs. 8.6 ± 3.4 mmHg, p = 0.037; mean difference: 1.8 mmHg, 95% CI: 0.1–3.4). In contrast, the pressure in the superior vena cava (SVCP) did not change significantly after the procedure (12.6 ± 3.2 mmHg vs. 11.3 ± 3.7 mmHg, p = 0.058; mean difference: 1.3 mmHg, 95% CI: −0.1–2.7). The minimal post-occlusion pressure gradient between the SVCP (12.6 ± 3.2 mmHg) and the mPAP (12.3 ± 2.7 mmHg) suggests the absence of significant stenosis at the cavopulmonary anastomosis.

Following vertical vein occlusion, SFAO2 markedly improved in both cases (Case 13: 98% vs. 86%; Case 14: 99% vs. 88%). Detailed pre- and post-operative hemodynamic data for all patients are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of characteristics before and after interventional treatment.

| Azygos/Hemiazygos Vein | Pre | Post | t/z | p | D and 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | z = −1.6 | 0.115 | / |

| SFAO2% | 75.1 ± 3.7 | 87.0 ± 2.7 | t = 10.3 | <0.001 | 12.0 (9.3–14.3) |

| sPAP, mmHg | 13.0 ± 3.9 | 14.4 ± 3.2 | t = 1.5 | 0.167 | 1.4 (−0.7–3.5) |

| dPAP, mmHg | 8.6 ± 3.4 | 10.3 ± 3.2 | t = 2.4 | 0.037 | 1.8 (0.1–3.4) |

| mPAP, mmHg | 10.8 ± 3.3 | 12.3 ± 2.7 | t = 2.5 | 0.027 | 1.6 (0.2–3.0) |

| SVCP, mmHg | 11.3 ± 3.7 | 12.6 ± 3.2 | t = 2.1 | 0.058 | 1.3 (−0.1–2.7) |

| AA, mm | 28.0 ± 6.3 | 28.9 ± 5.3 | t = 1.1 | 0.308 | 0.9 (−1.0, 2.8) |

| LA, mm | 27.0 ± 6.1 | 27.3 ± 7.7 | t = 0.3 | 0.087 | 0.3 (−2.0, 2.5) |

| LV, mm | 40.0 ± 10.0 | 38.9 ± 8.0 | t = −0.8 | 0.440 | −1.2 (−4.4, 2.0) |

| EF, % | 62.5 (59.3, 64.9) | 60.0 (60.0, 65.2) | z = −0.9 | 0.385 | / |

| MPA, mm | 13.3 ± 2.4 | 13.9 ± 2.9 | t = 0.7 | 0.517 | 0.7 (−1.5, 2.9) |

| Vertical vein | Case 14 | Case 15 | |||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| CTR | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| SFAO2 | 86 | 98 | 88 | 99 | |

| mPAP, mmHg | 20 | 22 | 28 | 30 | |

| AA, mm | 23 | 26 | 24 | 20 | |

| EF, % | 71 | 60 | 63 | 65 | |

| MPA, mm | 27 | 21 | 16 | 18 | |

During a mean follow-up period of 26.3 ± 13.9 months (range: 6–50 months), all patients exhibited marked clinical improvement with resolution of cyanosis. No instances of facial or neck edema, jugular venous distension, or recanalization of the occluded veins were observed. SpO2 remained stable above 90% throughout the follow-up period. In the two patients with minor residual shunts identified immediately post-procedure, the shunt size remained stable without progression. Subsequent to the occlusion procedure, three patients successfully underwent Fontan completion surgery within six months, all recovering without complications. In the two cases of vertical vein closure, a transient postoperative increase in mPAP was noted, which returned to normal levels within one month.

4.1 The Causes of Exacerbated Cyanosis in Patients with CCHD after Surgery

Although the BGP is an effective palliation, patients remain at risk for postoperative sequelae, most notably hypoxia and progressive cyanosis. Common underlying mechanisms include an age-related increase in systemic oxygen demand coupled with a relative reduction in the proportion of superior vena cava flow contributing to total pulmonary blood flow. This mismatch creates a state of “supply-demand imbalance.” The development of systemic venous collaterals and PAVF further exacerbates cyanosis. Venous collateral formation is a frequent occurrence after BGP, with an incidence reported between 17% and 33% [2,6]. Recruitment of the azygos or hemiazygos veins is most common. Elevated pressure within the cavopulmonary pathway post-BGP drives decompressive flow through these collateral channels toward lower-pressure territories—such as the inferior vena cava, right atrium, or pulmonary veins—representing an adaptive response to altered hemodynamics. Persistent flow through these channels has two principal detrimental effects: it directly reduces effective pulmonary blood flow (thereby increasing cardiac preload) and allows desaturated blood to enter the systemic circulation via the right atrium or pulmonary veins, significantly lowering systemic arterial oxygen saturation and worsening cyanosis. The underlying elevated driving pressure can result from multiple factors, including thrombosis within the cavopulmonary pathway, stenosis at the cavopulmonary anastomosis, pulmonary artery hypoplasia, or inadequate pulmonary artery ligation [6]. Collateral formation may also involve the recruitment of pre-existing but non-patent venous channels, such as postnatally occluded vessels or a persistent left superior vena cava that recanalizes [7]. PAVF formation represents another major sequel, particularly following the Kawashima procedure in patients with left atrial isomerism (polysplenia syndrome), where incidence may reach 32% and tends to increase over time [8]. Physiologically, PAVF constitute an extracardiac right-to-left shunt, allowing pulmonary arterial blood to bypass the alveolar capillary bed and shunt directly into the pulmonary veins. This creates a functional ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, which manifests clinically as worsening cyanosis.

Surgical repair is indicated for all patients with TAPVC, urgently in obstructive forms. However, due to the lack of normal pulmonary venous return preoperatively, patients with TAPVC often have an underdeveloped left heart with reduced chamber volume and poor compliance. When pulmonary venous obstruction coexists, ligation of the vertical vein during repair can precipitate an acute pulmonary hypertensive crisis. Consequently, for patients with a small left ventricle, poor compliance, or venous obstruction, vertical vein ligation may be unnecessary and is potentially harmful [9,10]. In such high-risk scenarios, leaving the vertical vein patent is a deliberate surgical strategy. It functions analogously to a retained ASD, providing a crucial decompression pathway and allowing right-to-left shunting to support systemic cardiac output in the early postoperative period. These patent veins help mitigate the risk of life-threatening pulmonary hypertensive crises. In most patients, they undergo spontaneous closure as hemodynamics adapt to the corrected circulation [11]. However, in a minority of cases, it remains patent; persistent left-to-right shunting can lead to excessive right heart pressure and pulmonary hypertension. This may eventually result in right ventricular pressure exceeding left ventricular pressure, causing a reversal to right-to-left shunting, which in turn leads to decreased arterial oxygen saturation and progressive cyanosis [11].

4.2 The Safety and Effectiveness of Interventional Treatment

Khajali et al. [12] first reported a case of successful occlusion of a residual shunt in the azygos vein after BGP in a patient with CCHD using a ventricular septal defect occluder. Maddali et al. [7] also reported a case of successful occlusion of a recanalized azygos vein after BGP in a patient with CCHD using a vascular plug.

Lu et al. [13] evaluated the safety and efficacy of transcatheter closure for residual azygos or hemiazygos vein shunts after BGP in nine patients with CCHD. The procedure was successful in all patients, resulting in complete occlusion in 81.8% of vessels, with a mild residual shunt persisting in 18.2%. Post-procedurally, SFAO2% increased from 81% to 88%, while SVCP and mPAP remained stable. No serious adverse events were reported during follow-up. In the largest retrospective series to date, Dai et al. [14] reported on 24 patients with CCHD who underwent the same intervention for residual shunts after BGP. All procedures were successful. SpO2 increased significantly from 78% to 85% (p < 0.05), whereas SVCP showed no significant change (13.94 mmHg vs. 14.22 mmHg, p > 0.05). Over a two-year follow-up, no patient developed complications such as facial/limb edema or abdominal varicosities, and no significant decline in SpO2 was observed. The feasibility of percutaneous vertical vein occlusion has also been documented. For example, Kobayashi et al. were the first to report successful occlusion of a residual vertical vein shunt (approximately 8.2 mm in diameter) after repair of subcardiac TAPVC, using a 10 mm Amplatzer Vascular Plug I; a Gianturco coil was also deployed to ensure complete closure [15]. Subsequently, Lombardi [16], Charbel [17], and Akam-Venkata [18], among others, have also reported successful occlusion of residual vertical vein shunts after supracardiac TAPVC repair using the Amplatzer Vascular Plug II. Gumustas et al. [19] conducted a retrospective study (2011–2018) to evaluate the efficacy of this intervention in five patients with residual vertical vein shunts after supracardiac TAPVC repair. All procedures were technically successful. During a follow-up of 3 to 6 years, transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated normal right heart dimensions in all patients, with no evidence of pulmonary hypertension, device dislocation, residual shunt, or device-related thrombosis.

In clinical practice, the management strategy for shunts involving the azygos or hemiazygos vein is typically stratified based on shunt severity and venous diameter relative to the innominate vein. For mild shunts (diameter ≤ 25% of the innominate vein), intervention is generally not required, and periodic follow-up is considered sufficient. Moderate shunts with mild to moderate venous dilation (diameter ≤ 50% of the innominate vein) are usually addressed with coil embolization. For severe shunts accompanied by marked venous dilation (diameter > 50% of the innominate vein), the use of atrial septal defect (ASD) or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) occluders is recommended [13]. In our protocol, ASD occluders are often preferred for such venous occlusions. This preference is based on the relatively thinner wall of veins compared to arteries; ASD occluders exert lower radial force upon deployment, which may help mitigate the risk of procedure-related complications.

For transcatheter closure of vertical veins, available devices include vascular plugs, ASD occluders, and PDA occluders. Among these, vascular plugs offer several technical advantages that make them particularly suitable for this application. These advantages include a membrane-free design, a lower-profile delivery system, a reduced risk of embolization, retrievability prior to final release, and the ability to be repositioned during the procedure.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the investigation was designed as a single-center, retrospective analysis with a relatively small cohort. This design inherently carries the potential for selection bias and limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, many of the measured postoperative hemodynamic parameters did not demonstrate statistically significant changes. We attribute this likely to the timing of data collection, as most post-procedural measurements were obtained immediately or within the first day after intervention—a period that may be insufficient for significant physiological alterations to manifest. Third, although the short- and mid-term clinical outcomes appear favorable over a mean follow-up period of 26.3 ± 13.9 months (range 6–50 months), the long-term safety and durability of the procedure remain uncertain. Consequently, further validation through multicenter, prospective studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up is warranted. Finally, a significant portion of our study cohort remained at the Glenn stage and did not proceed to subsequent Fontan surgery. This may reflect that, during that historical period, institutional practices were influenced by conventional approaches, rather than incorporating more current perspectives on surgical management.

In patients with CCHD, transcatheter closure of abnormal systemic venous collaterals constitutes a safe and effective therapeutic strategy following initial palliative surgery. The procedure significantly improves systemic arterial oxygen saturation, alleviates cyanosis, and enhances cardiac performance. Characterized by a high technical success rate and favorable short- to mid-term outcomes, this intervention effectively obviates the need for repeat thoracotomy, thereby sparing patients the associated physical trauma and psychological burden.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission “Capital Clinical Characteristic Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Research and Transformation Application” Special Fund (grant number: Z201100005520075), Central High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Operating Funds (grant number: 2022-GSP-GG-18) and China Academy of Medical Sciences Central-Level Public Welfare Research Institute Basic Scientific Research Operating Funds (grant number: 2022-RW320-09).

Author Contributions: Haibo Hu contributed to the design of the study. Zhengwei Li contributed to the data collection and analysis, while all authors contributed to data interpretation. Zhengwei Li drafted the manuscript andXin Li, Dong Luo, Meijun Liu, and Luxi Guan all gave valuable suggestions on the progress of the research. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Haibo Hu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. 2021-1551). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Diliz-Nava HS , Barrera-Fuentes M , Castañuela-Sanchez VL , Martinez MM , Palacios-Macedo A . Early bidirectional glenn procedure as initial surgical palliation for functionally univentricular heart with common arterial trunk. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2023; 14( 1): 673– 682. doi:10.1177/21501351221126097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jiang L , Li Y , Yang ZG . Azygos vein steal syndrome after Glenn procedure in a rare single atrium-single ventricle: Computed tomography insights in management of palliative cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2025; 46( 37): 3668. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li C-X , Gong X-L , Zhu L-M , Du X-W , Zhang H-B , Xu Z-M . Predictive factors for prolonged ventilatory support in infants undergoing total anomalous pulmonary venous connection repair: A retrospective cohort study. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 26( 10): 39215. doi:10.31083/RCM39215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Alanís-Naranjo JM , Inquilla-Coyla MJ , Barrera-Colín MF , de la Mora-Cervantes R . Dual drainage total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: diagnosis by cardiac computed tomography angiography. JACC Case Rep. 2025; 30( 26): 104891. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2025.104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vanderlaan RD , Caldarone CA . Surgical approaches to total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2018; 21: 83– 91. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2017.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Maddali MM , Adhikari RK , Al-Yamani MI . Hypoxemia due to intercostal and accessory hemiazygos veins following bidirectional glenn procedure in a 3-year-old boy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2024; 38( 12): 3281– 3. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2024.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maddali MM , Aamri IA , Kandachar PS , Saxena P , Alawi KA . Collateral-induced hypoxemia after bidirectional glenn procedure. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2024; 38( 9): 2118– 21. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2024.04.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lively-Endicott H , Lara DA . Successful palliation via kawashima procedure of an infant with heterotaxy syndrome and left-atrial isomerism. Ochsner J. 2018; 18( 4): 406– 12. doi:10.31486/toj.18.0042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao K , Wang H , Wang Z , Zhu H , Fang M , Zhu X , et al. Early- and intermediate-term results of surgical correction in 122 patients with total anomalous pulmonary venous connection and biventricular physiology. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015; 10( 1): 172. doi:10.1186/s13019-015-0387-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Seale AN , Uemura H , Webber SA , Partridge J , Roughton M , Ho SY , et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: Morphology and outcome from an international population-based study. Circulation. 2010; 122( 25): 2718– 26. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.940825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gupta A , Gunsaulus M , Erdmann A , Medina MC , Alsaied T , Kreutzer J . Persistent patent vertical vein after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVR): A rare cause of hypoxemia post-fontan procedure. Pediatr Cardiol. 2025; 46( 1): 222– 6. doi:10.1007/s00246-023-03363-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Khajali Z , Firouzi A , Pashapour P , Ghaderian H . Trans catheter device closure of a large azygos vein in adult patient with systemic venous collateral development after the bidirectional Glenn shunt. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2021; 13( 4): 367– 9. doi:10.34172/jcvtr.2021.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lu M , Wu W , Zhang G , So A , Zhao T , Xu Z , et al. Transcatheter occlusion of azygos/hemiazygos vein in patients with systemic venous collateral development after the bidirectional Glenn procedure. Cardiology. 2014; 128( 3): 293– 300. doi:10.1159/000362157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Dai C , Guo B-J , Ling Y , Chen L , Jin M . Effect of transcatheter occlusion of azygos/hemiazygos vein in patients with venous stealing after the bidirectional Glenn procedure-analysis of 24 cases. Chin J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020; 36( 3): 156– 61. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112434-20190831-00291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kobayashi D , Forbes TJ , Delius RE , Aggarwal S . Amplatzer vascular plug for transcatheter closure of persistent unligated vertical vein after repair of infracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012; 80( 2): 192– 8. doi:10.1002/ccd.23497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lombardi M , Tagliente MR , Pirolo T , Massari E , Sisto M , Vairo U . Transcatheter closure of an unligated vertical vein with an Amplatzer Vascular Plug-II device. J Cardiovasc Med. 2016; 17: e221– 3. doi:10.2459/JCM.0000000000000197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Charbel R , Hanna N , Daou L , Saliba Z . Catheter closure of a recanalized vertical vein after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Clin Case Rep. 2018; 6( 5): 843– 6. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Akam-Venkata J , Turner DR , Joshi A , Aggarwal S , Gupta P . Diagnosis and Management of the Unligated Vertical Vein in Repaired Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2020; 11( 4): NP229– 31. doi:10.1177/2150135118817491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gumustas M , Donmez YN , Aykan HH , Demircin M , Karagoz T . Transcatheter closure of patent vertical vein after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: A case series. Cardiol Young. 2021; 31( 11): 1853– 7. doi:10.1017/S1047951121001517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools