Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Genetic Factors Influencing Response to Lipid-Lowering Therapies in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review

1 Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Engineering, University of Caldas, Manizales, 170001, Colombia

2 Faculty of Technology, Technological University of Pereira, Pereira, 660003, Colombia

3 Departamento de Electrónica y Automatización, Universidad Autónoma de Manizales, Manizales, 170001, Colombia

* Corresponding Author: Miguel Meñaca-Puentes. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 743-767. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.070423

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of global mortality, with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol established as a primary causal risk factor. Despite widespread implementation of statin therapy, substantial interindividual variability in treatment response persists, necessitating precision medicine approaches to optimize therapeutic outcomes. This comprehensive narrative review synthesizes current understanding of pharmacogenomic determinants influencing lipid-lowering therapy efficacy, examines mechanisms underlying residual cardiovascular risk, and evaluates emerging therapeutic modalities targeting previously unexploited pathways in lipid metabolism. Genetic variants in key genes including 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, apolipoprotein E, low-density lipoprotein receptor, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 demonstrate significant associations with differential treatment responses, with specific polymorphisms conferring enhanced efficacy or increased intolerance risk. Beyond traditional statin therapy, novel therapeutic approaches targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, angiopoietin-like protein 3, apolipoprotein C-III, and ATP citrate lyase offer substantial low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reductions of 50–80%, while RNA-based therapies including antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNA provide precise molecular targeting capabilities. Despite intensive lipid-lowering interventions, residual cardiovascular risk persists through four principal mechanisms: triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a), inflammatory processes, and suboptimal treatment adherence. Integration of pharmacogenomic insights with emerging therapeutic modalities enables personalized risk stratification and treatment selection, representing a paradigm shift toward precision medicine in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.Keywords

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) established as a primary causal risk factor through extensive epidemiological, clinical, and genetic evidence [1]. The linear relationship between LDL-C reduction and cardiovascular benefit has been consistently demonstrated across diverse populations, with meta-analyses revealing that the magnitude of risk reduction increases progressively with longer treatment durations, from 12% relative risk reduction per mmol/L LDL-C lowering in the first year to 29% by the seventh year of therapy [2].

Statins, as inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), have served as the cornerstone of lipid-lowering therapy since their introduction, demonstrating consistent efficacy in reducing cardiovascular events across primary and secondary prevention populations [1,3]. However, despite the widespread implementation of guideline-directed statin therapy, substantial interindividual variability in treatment response persists, with clinical observations indicating that many patients continue to experience elevated cholesterol levels despite optimal dosing [4]. This heterogeneity in therapeutic response is attributed to complex interactions between genetic polymorphisms, drug metabolism pathways, and patient-specific factors that collectively influence both efficacy and tolerability.

The genetic architecture underlying statin response involves multiple pathways, with variants in HMGCR itself, demonstrating associations with enhanced LDL-C reduction capacity [5]. Pharmacokinetic determinants further modulate treatment outcomes, as exemplified by the CYP3A4*16 variant (rs12721627 dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs12721627, accessed on 01 July 2025), which increases atorvastatin exposure and contributes to statin intolerance in Japanese populations [6]. Similarly, the CYP2C19 poor metabolizer phenotype associates with significantly reduced atorvastatin efficacy [7].

Beyond pharmacokinetic considerations, genetic variants in lipid metabolism pathways critically influence treatment response. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) polymorphisms demonstrate profound effects on statin efficacy [8]. The APOE p.(Leu167del) variant presents a particularly complex clinical phenotype, causing hypercholesterolemia with resistance to PCSK9 inhibitors while maintaining responsiveness to bempedoic acid and ezetimibe [9]. Low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) variants further contribute to therapeutic variability, with null variants in familial hypercholesterolemia patients associated with higher baseline LDL-C levels, greater coronary disease risk, and suboptimal responses to conventional therapies [10,11].

Despite intensive lipid-lowering interventions, significant residual cardiovascular risk persists. The recognition of these limitations has catalyzed the development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting previously unexploited pathways in lipid metabolism. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) has emerged as a pivotal regulatory protein that mediates LDLR degradation, with both gain-of-function and loss-of-function variants demonstrating profound effects on cholesterol homeostasis and cardiovascular risk [12]. Genetic studies have revealed that PCSK9 loss-of-function mutations confer protection against coronary heart disease, providing the biological rationale for therapeutic PCSK9 inhibition [13].

This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of lipid-lowering therapeutic approaches, examining the genetic determinants of treatment response, mechanisms underlying residual cardiovascular risk, and the clinical development of novel agents targeting previously unexploited pathways. By integrating pharmacogenomic insights with emerging therapeutic modalities, this analysis provides a framework for optimizing cardiovascular risk reduction through precision medicine approaches in lipid management.

2 Literature Review Methodology

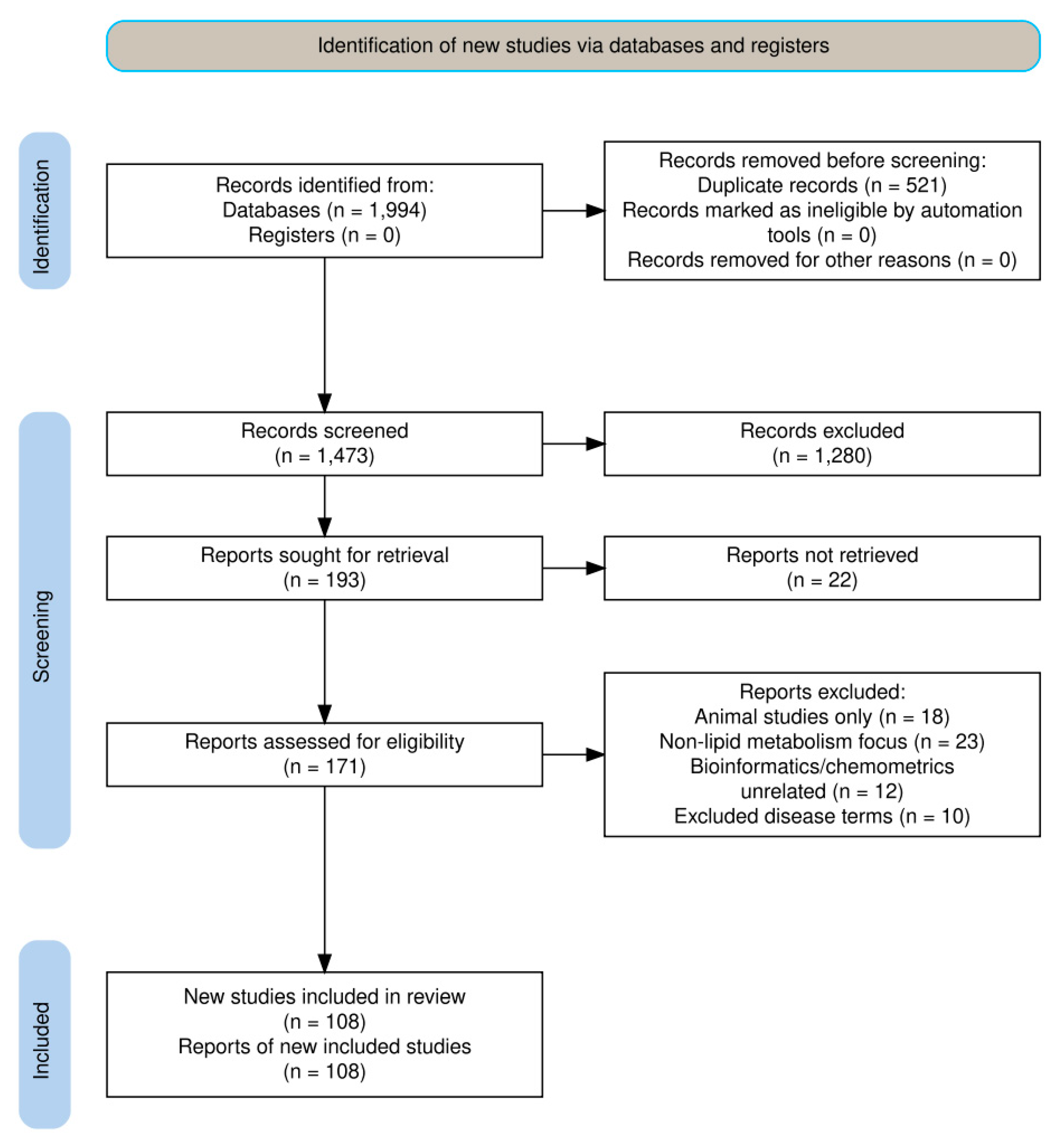

This research process was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [14] guidelines to ensure a comprehensive and transparent literature search process.

2.1 Search Strategy and Databases

A systematic search was performed on 03 July 2024, covering publications from 2020 onwards. The temporal limit was chosen to align with the updated PRISMA 2020 guidelines [14] and recent key reviews/meta-analyses (e.g., [1,2,3]), capturing advancements in emerging lipid-lowering therapies (e.g., PCSK9 inhibitors, ANGPTL3 targets) and pharmacogenomic associations post-2020. This ensures focus on clinically relevant, post-pandemic data with standardized omics integration, reducing heterogeneity from pre-2020 methodologies and avoiding overlap with earlier syntheses (e.g., [10,11]). The following databases were queried:

- PubMed

- Web of Science

- Scopus

- Science Direct

The search string used was: (variant OR polymorphism OR mutations*) AND (“lipid-lowering” OR “cholesterol-lowering”). For Science Direct, which does not support wildcards, the search string was modified and further limited due to excess results:

(variant OR polymorphism OR mutation) AND (“lipid-lowering” OR “cholesterol-lowering”) -microbiota -allergic -cancer -plantarum -diabetic -diabetes -ganodermalucidum -leaves.

Grey literature (e.g., conference abstracts, theses) and unpublished data were not included to prioritize peer-reviewed evidence and maintain methodological rigor, as per PRISMA recommendations.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

- Pub Human studies only

- Focus on lipid-lowering therapies (statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and other emerging agents)

- Studies on heart diseases and dyslipidemias in specific populations with omics data

- Examination of genetic variants’ association with response to lipid-lowering therapies

- Study designs: Clinical trials (randomized controlled trials) and observational studies (cohort, case-control)

- Publication type: Original research articles in peer-reviewed journals and review articles.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Studies focusing on bioinformatics and chemometrics unrelated to lipid metabolism

- Engineering of biological systems unrelated to lipid pathways

- Industrial applications of biochemical processes

- Environmental science and remediation

- Spectroscopy techniques for compound characterization

- Food science and nutrition unrelated to lipid metabolism

- Non-lipid related vascular diseases

- Genetic diseases not primarily affecting lipid metabolism

- Animal models not directly translatable to human lipid disorders

- Studies on diseases or conditions unrelated to lipid metabolism or cardiovascular health. For a visual representation of the full retrieval strategy, including identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages, see Fig. 1 (PRISMA flow diagram)

- Studies containing the following terms were excluded: Cancer, covid, sars, sepsis, osteo, parkinson, alzheimer, hiv, rheumatoid, prostate, diabetes, brain, epilepsy.

Figure 1: PRISMA methodology charter flow.

The initial search yielded 1994 articles across all databases (PubMed: 364, Web of Science: 453, Scopus: 416, Science Direct: 761). After removing duplicates using EndNote software, 1473 unique articles remained.

A two-phase filtering process was then applied:

- 1.First Filtering Step: Exclusion of studies based on general themes unrelated to lipid metabolism and cardiovascular health;

- 2.Second Filtering Step: Further refinement based on specific exclusion criteria related to diseases and conditions outside the scope of the review.

Following the systematic application of inclusion and exclusion criteria through the two-phase filtering process, a total of 108 articles were ultimately selected for inclusion in this comprehensive review. These selected studies formed the evidence base ensuring that all included publications directly addressed the research objectives within the defined scope of lipid metabolism and cardiovascular health.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction from the 108 selected articles was performed systematically using a standardized data extraction form designed specifically for this review. Two independent reviewers extracted data from each included study, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer when consensus could not be reached.

The following data items were systematically extracted from each study:

- Study design: There were 23 randomized trials, 67 observational studies and 18 meta-analysis and systematic reviews

- Geographic distribution: for the populations studied in this issue there were European (34), Asian (28), north American (12), middle eastern (8), multi-ethnic/global (26)

- Baseline features: Sample sizes ranged from 10 to over 100,000 participants (median: 500; aggregated total across studies: approximately 250,000); racial/ethnic distribution included Caucasian (45%), Asian (30%), African/Black (10%), Hispanic/Latino (8%), and other/mixed (7%), reflecting multi-ethnic/global emphases in recent literature

- Genetic variants investigated (gene names, specific polymorphisms, allele frequencies) file

- Lipid-lowering interventions (drug type, dosage, duration of treatment)

- Primary and secondary outcomes (LDL-C reduction, HDL-C changes, triglyceride levels, cardiovascular events)

- Pharmacogenomic associations (effect sizes, odds ratios, confidence intervals, p-values).

Data synthesis was primarily narrative due to heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and genetic variants investigated. Heterogeneity was handled by avoiding quantitative meta-analysis (due to variability in effect sizes and populations) and instead using qualitative tabulation for comparisons, subgroup analyses by geographic/racial groups where feasible, and sensitivity checks for high-impact variants (e.g., PCSK9, APOE). Where appropriate, results were tabulated to facilitate comparison across studies, with particular attention to effect sizes, population characteristics, and clinical significance of findings. All extracted data were independently verified by a third reviewer to ensure accuracy and completeness.

3 Current Lipid-Lowering Therapies

3.1 Statins: The Cornerstone of ASCVD Prevention

Statins, inhibitors of HMGCR, constitute the cornerstone of lipid-lowering therapy, significantly reducing ASCVD risk by lowering LDL-C levels [1,3]. Large-scale clinical trials consistently demonstrate their efficacy in reducing cardiovascular events across diverse populations. A meta-analysis by Wang et al. [2] demonstrated that the benefits of LDL-C reduction increase progressively with longer treatment durations, underscoring the value of sustained statin therapy. International guidelines recommend statins as first-line therapy for primary and secondary ASCVD prevention, with high-potency agents like rosuvastatin and atorvastatin frequently prescribed for conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

In pediatric populations, statins demonstrate safety and efficacy. Llewellyn et al. [15] reported a substantial 33.61% LDL-C reduction in children with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH). Martinsen et al. [16] demonstrated significant LDL-C reductions in children homozygous for an LDLRAP1 frameshift mutation using high-intensity statins, administered either alone or in combination with ezetimibe. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of commonly prescribed statins, detailing their LDL-C reduction capacity, key benefits and notable side effects.

Table 1: Characteristics of commonly prescribed statins.

| Statin | LDL-C Reduction | Key Benefits | Notable Side Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin | 35–60% | Reduces cardiovascular events, long half-life, lowers plasma ANGPTL3 by 15% (p = 0.012) | Myalgia, elevated liver enzymes | [17,18] |

| Rosuvastatin | 45–63% | Most potent LDL-C reduction, decreases carotid intima-media thickness | Increased risk of new-onset diabetes, potential for rhabdomyolysis in high-risk patients | [19,20] |

| Simvastatin | 30–50% | Well-established long-term safety data | Increased myopathy risk at high doses, efficacy affected by CYP7A1 and MTHFR polymorphisms | [21,22,23] |

Comparative analysis of major statin formulations. ANGPTL3, Angiopoietin-like protein 3; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Genes are written in italics. Data for Atorvastatin and Rouvastatin was obtained from European populations, data for Simvastatin was obtained from Asian populations. This suggests potential preferences or responses to statin formulations across populations or a variation in treatment response.

Pharmacogenetic research highlights inter-individual variability in statin response. Abdulfattah et al. 24] report polymorphisms such as rs200727689 and rs72658860 are associated with atorvastatin efficacy, with increased A allele frequencies in coronary artery disease patients (odds ratios of 2.46 and 2.22, respectively). Subsequently, Abdulfattah et al. [25] linked the SR-B1 gene polymorphism rs4238001 (CC genotype, dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs4238001, accessed on 01 July 2025) to higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in response to rosuvastatin. Shi et al. [26] noted that polymorphisms in statin-metabolizing enzymes and transport proteins influence therapeutic efficiency and adverse effects. Čereškevičius et al. [7] reported significantly reduced atorvastatin response in 29% of acute coronary syndrome patients exhibiting the CYP2C19 slow metabolizer phenotype.

Molecular mechanisms further elucidate statin actions. Das et al. [5] identified seven HMGCR single nucleotid polymorphisms (SNPs) (e.g., rs147043821, rs193026499) predicted to cause significant structural and functional instability. Corral et al. [27] noted that statins increase circulating PCSK9 levels, potentially attenuating their LDL-C-lowering effect. Ghiasvand et al. [28] found that statin therapy in coronary artery disease patients significantly reduced LDLR gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) while significantly increasing PCSK9, LASER gene expression and PCSK9 blood concentrations compared to controls. Reeskamp et al. [18] demonstrated that statins lower plasma Angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) concentrations by 15% (p = 0.012) in FH patients, with levels increasing by 21% (p < 0.001) upon discontinuation.

Despite their efficacy, statins possess limitations. There are reports of a modest increase in lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels, insufficient to significantly mitigate Lp(a)-associated risk [29]. Low effectiveness in chronic heart failure patients has been reported, with only 38.1% achieving total cholesterol < 4.5 mmol/L and merely 11% reaching LDL-C < 1.8 mmol/L [30]. Ye et al. [31] reported an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease development with statin use compared to non-users, although a protective effect was observed in individuals carrying two APOE E4 alleles. Baptista et al. [32] highlighted persistent concerns regarding myopathy, myalgia, liver injury, digestive problems, mental fuzziness, and interactions with other drugs or specific foods, proposing adjuvant dietary interventions to enhance efficacy and reduce adverse effects. Li et al. [33], using Mendelian Randomization, determined that genetically mimicking effects of statins reduce the risk of ischemic heart disease (OR 0.55 per unit decrease in LDL-C, 95% CI 0.40–0.76) but pleiotropically increase body mass index (BMI) (0.33 units, 95% CI 0.28–0.38).

Ezetimibe, approved in 2002, inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption via the Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) protein, achieving an additional 15–20% LDL-C reduction when combined with statins [1]. Llewellyn et al. [15] reported an additional 15.85% LDL-C reduction in HeFH children when added to statins. Martinsen et al. [16] demonstrated a 75% LDL-C reduction and near-complete xanthoma regression in a child with autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia using atorvastatin (40 mg/d) combined with ezetimibe (10 mg/d). Wang et al. [2], in a meta-analysis including ezetimibe, confirmed that each mmol/L LDL-C reduction correlates with greater risk reduction over longer treatment durations. Unlike statins, genetically mimicked ezetimibe effects effectively reduce LDL-C and ischemic heart disease risk without increasing BMI [33]. However, Ling et al. [3] noted that some FH patients remain unresponsive to ezetimibe. Most of these reports come from European populations.

PCSK9 inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (evolocumab, alirocumab) and small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) (inclisiran), target PCSK9, a protein mediating LDL receptor degradation, thereby enhancing LDL-C clearance. These agents achieve substantial LDL-C reductions, ranging from 41.7% to 60%, when added to statin therapy [34], providing up to 50% additional reduction beyond statin therapy [35]. In FH, PCSK9 inhibitors are effective for both HeFH and some homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) patients [36]. Alonso et al. [37] noted their use in 28% of HoFH patients, with 36% achieving LDL-C < 100 mg/dL when combined with other therapies.

Bempedoic acid, an adenosin triphosphate citrate lyase (ACLY) inhibitor, reduces LDL-C by 15–25% when added to statins, offering an alternative for statin-intolerant patients [38]. Agha et al. [39] reported significant LDL-C reductions in an HeFH patient intolerant to statins.

3.2.4 Fibrates and Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids, and niacin reduce triglycerides (TG) in severe hypertriglyceridemia but lack robust evidence for ASCVD risk reduction in the statin era [40]. Ying et al. [41] found that high-dose omega-3 fatty acids (4 g/day) significantly improve postprandial arterial elasticity in FH adults, suggesting non-lipid benefits.

3.3 Residual Cardiovascular Risk

Despite intensive lipid-lowering therapies, residual cardiovascular risk persists. Alonso et al. [37] reported that 15% of HoFH patients developed new ASCVD events. Choi et al. [42] noted that many FH patients fail to reach LDL-C targets, and Coutinho et al. [43] linked prior ASCVD to incident events in elderly patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. Residual risk arises from four key components:

- 1.TG-Rich Lipoproteins and Remnants: Chen et al. [44] highlighted very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) as contributors to residual risk, with statins inadequately lowering TG [45]. Ko et al. [46] linked higher remnant cholesterol to cardiometabolic risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, microalbuminuria, and metabolic liver disease. Lindhardt Johannesen et al. [47] noted elevated non-HDL-C and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) as residual risk markers in treated patients.

- 2.Lp(a): Lp(a) is the most prevalent inherited risk factor for cardiovascular disease [48]. Averna et al. [29] noted persistent risk in patients with high Lp(a) despite LDL-C control, as statins may increase Lp(a) levels. PCSK9 inhibitors offer modest Lp(a) reduction (10% median reduction, p < 0.001) but leave significant residual risk [49].

- 3.Inflammation and Non-Lipid Factors: Inflammation contributes significantly to residual risk. Chen et al. [50] linked lipid dysfunction to aneurysms through Mendelian randomization. Gigante et al. [51] associated HDL composition changes with dysglycemia and subclinical atherosclerosis and Pedro-Botet et al. [52] highlighted atherogenic dyslipidemia and hyperlipoproteinemia(a) in type 2 diabetes as key residual risk drivers.

- 4.Suboptimal Adherence and Treatment Gaps: Poor adherence undermines therapy efficacy. Butty et al. [53] noted worse control in PCSK9 inhibitor-eligible patients post-acute coronary syndrome, and Catapano et al. [54] emphasized that half of clinicians that routinely measure Lp(a) recognize 50 mg/dL as the threshold for elevated Lp(a) risk, indicating the need for standardized assessment.

4 Genetic Factors Influencing Treatment Response

Genetic studies have facilitated the development of inhibitors targeting PCSK9 and ANGPTL3, now clinically utilized to reduce LDL-C levels in patients with hypercholesterolemia [13]. These therapies exemplify how genomic insights translate into practical treatment options. Moreover, variants in PCSK9 and APOB have been leveraged to identify drug candidates and enrich clinical trial designs, accelerating the integration of genomics into lipid therapy [13]. The application of results may be subjected to changes across different populations and specific gene variants present within those population.

Variants in the PCSK9 gene are associated with altered responses to lipid-lowering therapies. For instance, the rs28942111 (ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000003007/, accessed on 01 July 2025) SNP is linked to higher LDL-C and total cholesterol levels, with AA carriers showing reduced efficacy of atorvastatin [4]. Additionally, variants near KCNA5, KCNA1, and LINC00353 influence plasma PCSK9 levels, explaining approximately 4% of interindividual variation [55]. Increased PCSK9 gene expression in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients further affects treatment response, highlighting the gene’s role in lipid metabolism [28]. These findings underscore the need to consider PCSK9 variants when tailoring statin and PCSK9 inhibitor therapies.

The APOE gene, integral to lipoprotein metabolism, exhibits variants that differentially affect lipid-lowering therapy outcomes. The p.(Leu167del) variant is associated with resistance to PCSK9 inhibitors but retains responsiveness to bempedoic acid and ezetimibe [9]. APOE genotypes (E2, E3, E4) influence statin efficacy, with E2 carriers demonstrating greater LDL-C reduction and carotid plaque stabilization with atorvastatin compared to E3 or E4 carriers [8]. Carriers of the T allele of rs7412 (ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/17848/, accessed on 01 July 2025), despite higher baseline LDL-C, exhibit lower coronary disease risk and enhanced response to rosuvastatin [56]. Dietary interventions also interact with APOE variants, as E3 carriers show significant LDL-C reduction (−0.251 mmol/L, 95% CI −0.488 to −0.015) with plant sterol supplementation compared to E4 and E2 carriers [57], based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials. E4 carriers demonstrated benefits from higher doses and longer durations (−0.088027 mmol/L; 95% CI: −0.154690 to −0.021364).

LDLR variants are particularly relevant in FH patients, where they contribute to variable treatment responses. Abdulfattah et al. [24] evaluated LDLR variants (rs200727689; rs72658860) in Iraqi atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (ACAD) patients, finding significantly higher A allele frequencies compared to controls for both rs200727689 (43% vs. 23.5%; OR = 2.46; p = 0.000) and rs72658860 (40.5% vs. 23.5%; OR = 2.22; p = 0.0003). The rs72658860 AA genotype significantly affected atorvastatin response between 20 mg and 40 mg doses, while the rs200727689 AA genotype showed non-significant reductions in total cholesterol and LDL-C versus the GG genotype at 20 mg. Heterozygous FH patients with null LDLR variants exhibit higher LDL-C levels and greater coronary disease risk [10]. On-treatment LDL-C levels remain elevated in FH variant carriers (5.7 ± 1.5 vs. 4.7 ± 1.0 mmol/L; p = 3.7E−04) despite therapy [11]. Novel LDLR variants, including a frameshift variant (c.666_670dup), further expand the genetic landscape of FH [58]. Key genetic variants and their impact are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Key genetic variants and their impact on lipid metabolism and ASCVD risk.

| Gene/Variant | Impact on Lipid Metabolism | Association with ASCVD Risk | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDLR mutations | Elevated LDL-C levels in FH | Increased risk of premature coronary disease | [11,59] |

| APOE p.(Leu167del) | Causes hypercholesterolemia | Increased ASCVD risk | [9] |

| LDLRAP1 variants | Causes autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia | Increased ASCVD risk | [60] |

| ANGPTL3 loss-of-function | Low LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG levels | Reduced ASCVD risk compared to non-carriers (34%) | [3] |

| PCSK9/APOB rare variants | Low LDL-C | Reduced statin use in elderly | [61] |

| MYLIP, APOC1, LDLR, APOE, ABCG2 polymorphisms | Altered lipid metabolism | Significant association with CAD susceptibility (p = 0.016 to <0.0001) | [20] |

| SLCO1B1 variant | Affects statin metabolism | Associated with statin-induced myopathy | [62] |

Principal genetic variants affecting lipid homeostasis and cardiovascular risk, illustrating the molecular basis for personalized lipid-lowering therapeutic approaches and risk stratification. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; ASCVD, astherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAD, coronary artery disease. Genes are written in italics.

Drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters also modulate lipid-lowering therapy responses. The CYP3A416 variant (rs12721627 dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs12721627, accessed on 01 July 2025) is linked to increased atorvastatin plasma concentrations with 3.3-fold higher maximum concentration (Cmax) and 4.2-fold higher area under the curve (AUC) in homozygotes, contributing to statin intolerance in Japanese patients [6]. This study surveyed 483 Japanese patients on atorvastatin, identifying the CYP3A416 variant (allele frequency 2.2%) as a contributor to statin intolerance, with 258 patients discontinuing due to toxicity. It has also been noted that poor CYP2C19 metabolizer phenotypes, observed in 29% of patients with *2, *4, and *8 alleles in a cohort of 92 acute coronary syndrome patients, are associated with reduced atorvastatin efficacy [7]. Synergistic effects between SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 variants enhance atorvastatin-mediated reduction of LDL-C and total cholesterol in South Indian coronary artery disease patients in 86 South Indian coronary artery disease patients (n = 412 genotyped) [63].

The SR-B1 gene, involved in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism, influences treatment response through the rs4238001 variant (dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs4238001, accessed on 01 July 2025), examined in 150 Iraqi myocardial infarction patients treated with rosuvastatin 20 mg/day for 4 weeks, compared to 150 controls. A higher frequency of the T allele and TT genotype was observed in myocardial Infarction (MI) patients (p = 0.173; OR = 3.62; 95% CI: 0.74–17.64), while the CC genotype was associated with a significant rosuvastatin response (29.08 ± 53.2% change; p = 0.021) [25]. Genetic variants associated with response to lipid lowering therapies are further shown in Table 3.

Genetic mimicry of HMGCR and APOB inhibition is associated with increased type 2 diabetes risk, whereas lipoprotein lipase (LPL) enhancement correlates with reduced risk [64]. Genetic burden testing indicates that truncating mutations in both APOB and either PCSK9 or LPL (“human double knock-outs”) result in additive lipid profile changes, suggesting potential benefits from combination therapies [65]. 61 lead variants influencing remnant cholesterol levels were identified through genome-wide associations, with 21 gene sets enriched in lipid metabolism pathways [46]. Endothelial cell-related variants further refine our understanding of lipid metabolism and treatment response. Marston et al. [66] demonstrated that a 35-variant endothelial cell polygenic risk score (EC PRS) exhibits significant interaction with LDL-C levels for cardiovascular risk (p-interaction = 0.004), where individuals with elevated EC PRS show greater sensitivity to atherogenic LDL-C effects and derive substantially superior benefits from aggressive LDL-C lowering (68% and 29% relative risk reduction in primary prevention, p-interaction = 0.02). Dietary interventions also exhibit genotype-dependent effects. Higher carbohydrate intake in individuals with elevated genetic risk scores is associated with lower HDL-C levels, emphasizing gene-diet interactions [67].

Table 3: Genetic variants associated with responses to lipid-lowering therapies.

| Gene | Variant(s) | Potential Clinical Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMGCR | rs12916 (dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs12916, accessed on 01 July 2025), rs3931914, rs3846662, rs3846662 | Predict statin efficacy | [68,69] |

| SREBF1 | rs11591147, rs505151, rs9902941 | Predict statin efficacy | [68] |

| NPC1L1 | rs2072183 | Guide ezetimibe treatment | [70] |

| PCSK9 | rs505151, rs662145, rs487230, rs555687 | Inform PCSK9 inhibitor response | [13,55] |

| APOC3 | rs12294259, rs180326, rs2187126 | Predict response to TG-lowering therapies | [71,72] |

| ANGPTL8 | rs145464906T, rs760351239T | Guide ANGPTL8 inhibitor treatment | [73] |

| LDLR | c.666_670dupA1, p.(Asp224Alafs*43), rs1433099, rs1010679, rs3786721, rs3786722, rs379309, rs5742911, rs7188, rs73015030, c.631C > T, c.313 + 1G > A | Guide intensity of lipid-lowering therapy in FH | [58,68,72,74,75,76] |

| APOB | c.10580G>A: p.(Arg3527Gln)A2 | Inform diagnosis and treatment of FH | [77] |

| miR-499a | rs3746444 | Inform response to lipid-lowering agents | [78] |

| VEGFA | rs699947, rs2010963 | Beneficial association possibly lost because of statin therapy | [78] |

| ABCG5 | c.575delG, p.G192Afs*35 | Inform diagnosis for FH | [13,79] |

Pharmacogenomic variants influencing therapeutic response to specific lipid-lowering agents, providing genetic determinants for precision medicine implementation in dyslipidemia management. PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; TG, triglycerides; ANGPTL8, Angiopoietin-like protein 8; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia. Genes are written in italics. Most of the gene variants in this table were reported for Asian populations

Recent innovations, such as Li et al.’s [80] “mBAT-combo” test-based ensemble method, enhance the detection of multi-SNP associations in the context of masking effects, refining hidden trait association signals in genomic regions for improved cardiovascular risk stratification. Similarly, integrating Lp(a) screening into routine risk assessment, supported by improved assays and genetic testing, leverages genetic determinants of Lp(a) levels to bolster early detection and prevention strategies [81].

4.2 Pharmacogenomics of Lipid-Lowering Therapies

Statins inhibit HMGCR to reduce LDL-C. HMGCR variants, such as rs12916 (dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs12916, accessed on 01 July 2025) and rs17238484, enhance LDL-C reduction, though the CC genotype of rs12916 is associated with inadequate response in premature triple-vessel disease patients [5]. APOE variants, including p.(Leu167del) and rs7412 (ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/17848/, accessed on 01 July 2025), influence atorvastatin and rosuvastatin responses, with E2 carriers showing enhanced LDL-C reduction and plaque stabilization, while T allele carriers of rs7412 exhibit no intima-media thickness regression [8,56].

LDLR variants, such as rs200727689 and rs72658860, modulate atorvastatin efficacy in coronary artery disease patients, with AA genotypes showing dose-dependent LDL-C and total cholesterol reductions [24]. Null LDLR variants in FH patients are associated with suboptimal responses [58]. The SR-B1 rs4238001 variant (dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs4238001, accessed on 01 July 2025) influences rosuvastatin response, with the CC genotype linked to significant LDL-C reduction and higher HDL-C levels [24]. Mediation analysis has suggested that association of variants in the LDLR gene with extended lifespan is partly due to a 22.8% lifespan extension mediated through a reduced risk of coronary heart disease, reinforcing LDL-C’s pivotal role in ASCVD pathogenesis [72]. Chen et al. [72] further identifies LDLR as a promising genetic target for human longevity, with PCSK9, CETP, and APOC3 offering promising perspectives for non-statin therapies.

Metabolism and transport genes further refine statin pharmacogenomics. The CYP3A4*16 variant increases atorvastatin exposure, contributing to intolerance [6]. CYP2C19 poor metabolizers exhibit reduced atorvastatin efficacy, with age and smoking exacerbating undertreatment [7]. The UGT1A1 rs4148323 A allele is associated with increased 2-hydroxy atorvastatin formation and higher mortality risk in Chinese patients (hazard ratio 1.774; 95% CI, 1.031–3.052; p = 0.0198) [82]. SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 variants synergistically enhance atorvastatin and simvastatin efficacy, with population-specific haplotype distributions [63,83]. SLCO1B1 is located in the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes, it functions as a hepatic uptake transporter for atorvastatin. ABCB1 is located in the apical brush border of both enterocytes (intestinal) and hepatocytes, it functions in drug efflux/transport from cells. SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 variants work synergistically with SLCO1B1 metabolizing atorvastatin while ABCB1 variants affect drug transport. The interaction between these transporters affects overall drug bioavailability and therapeutic response [83]. The ABCG2 Q141K variant increases rosuvastatin exposure, supporting lower starting doses in Asian populations [84].

Ezetimibe, targeting NPC1L1, shows variable efficacy in LDL-C reduction that may be modulated by genetic variants in NPC1L1, which have been identified as factors influencing intestinal cholesterol absorption [70]. TG-lowering therapies, such as fibrates, are influenced by APOC3 and ANGPTL3 variants, which reduce TG-lowering efficacy [71]. PCSK9 inhibitors are affected by PCSK9 variants, with rs28942111 (ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000003007/, accessed on 01 July 2025) reducing atorvastatin efficacy [4]. Novel therapies, such as Ongericimab, demonstrate significant LDL-C reduction in FH patients, highlighting the role of genetic profiling [85].

Non-statin agents, including plant sterols, exhibit genotype-dependent effects. APOE E3 carriers show significant LDL-C reduction with plant sterol supplementation, while E4 carriers benefit from higher doses and longer durations [57]. In FH patients, genetic variants predict suboptimal responses to conventional therapies, supporting multidisciplinary pharmacogenomic approaches [86].

Variants in drug metabolism (CYP enzymes, UGT1A1), transport (SLCO1B1, ABCB1, ABCG2), and target genes (HMGCR, PCSK9, NPC1L1) contribute to variability in efficacy and tolerability. Additional effects have been recently addressed by Yang et al. [87], who report increased diabetic microvascular complication risk with HMGCR and PCSK9 inhibitors. This drug-target Mendelian randomization study analyzed SNPs associated with three major cholesterol-lowering drug targets to investigate their causal relationships with diabetic microvascular complications, including nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy. The analysis revealed that HMGCR inhibition significantly increased risks across all three complications: diabetic nephropathy (OR = 1.88 [1.50, 2.36], p = 5.55 × 10−8), diabetic retinopathy (OR = 1.86 [1.54, 2.24], p = 6.28 × 10−11), and diabetic neuropathy (OR = 2.63 [1.84, 3.75], p = 1.14 × 10−7). PCSK9 inhibitors demonstrated more selective effects, increasing risks of diabetic nephropathy (OR = 1.30 [1.07, 1.58], p = 0.009) and diabetic neuropathy (OR = 1.40 [1.15, 1.72], p = 0.001), but showing no significant association with diabetic retinopathy. It has been stated that integrating these insights into clinical practice through genetic panels and algorithms promises to enhance personalized dyslipidemia management [26]. The complexity of these relationships is highlighted by ethnic population differences and the need for validation across diverse populations.

HMGCR variants like rs12916 (dbSNP, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs12916, accessed on 01 July 2025) and rs17238484 are associated with statin efficacy, providing a genetic basis for optimizing statin therapy. Similarly, NPC1L1 variants guide ezetimibe treatment by predicting responsiveness. PCSK9 variants inform the use of PCSK9 inhibitors, with the work by Bensenor et al. [55] further elucidating genetic and environmental predictors of PCSK9 levels. For APOC3, variants like rs734104 predict responses to TG-lowering therapies, with Chen et al. [72] highlighting APOC3 as a promising target for non-statin therapies. The ANGPTL3 variant rs12654264 is linked to ANGPTL3 inhibitor treatment efficacy. Multiple pathogenic variants in LDLR guide the intensity of lipid-lowering therapy in FH, while the APOB variant c.10580G>A: p.(Arg3527Gln) and others inform FH diagnosis and treatment. These variants, once validated across diverse populations, could serve as the foundation for personalized treatment approaches.

4.3 Implementation Challenges Driven by Genetic Factors

The implementation of genetic variant-guided lipid-lowering therapy faces substantial economic and accessibility barriers that limit widespread clinical adoption. Cost-effectiveness remains a primary concern, with PCSK9 inhibitors experiencing elevated annual costs per patient and limited reimbursement from healthcare insurances in many countries, requiring price reductions to meet conventional cost-effectiveness thresholds [53]. Genetic testing accessibility is further constrained by lack of reimbursement, high laboratory testing costs, and limited payer coverage, with many insurers not including specialized testing such as Lp(a) measurement in traditional lipid panels [54]. Geographic and infrastructure limitations compound these challenges, as non-availability of genetic testing and uneven distribution of testing capabilities exist even among specialized European lipid clinics [54]. Insurance coverage dependencies significantly impact patient access, with reflex genetic testing contingent upon coverage and patient preference, while laboratory selection remains restricted by insurance networks and limited laboratory offerings [79]. The economic burden extends beyond initial testing costs, as prior authorization requirements for PCSK9 inhibitors are more extensive compared to other cardiometabolic drugs, creating prescription procedure difficulties despite attempted price reductions of approximately 60% in some markets [88].

Clinical implementation is complicated by significant inter-individual variability in treatment responses and challenges in applying genetic insights across diverse populations. Patients with severe genetic mutations, particularly those with LDLR activity below 2% of normal, demonstrate poor treatment responses to standard LDLR-dependent therapies, with PCSK9 inhibitor efficacy varying substantially based on mutation status [42]. The clinical utility is further limited by incomplete population-specific pharmacogenomic data, particularly in lower-income European countries, and significant interethnic variability that necessitates population-specific reference data rather than ethnicity-based prescribing approaches [89]. Technical standardization challenges persist, including lack of standardized Lp(a) measurement methodologies requiring apo(a) isoform-insensitive antibodies and worldwide implementation gaps [54]. Clinical trial design faces recruitment difficulties for specific genetic variants, requiring long study periods for cardiovascular outcome trials in genetically defined populations and validated surrogate endpoints for smaller studies [42]. Additionally, ethical considerations include patient psychological impact from variants of uncertain significance associated with increased anxiety and decisional regret, while population diversity limitations in research cohorts may impact genetic testing yield and generalizability across different ancestry groups [79].

5 Emerging Lipid-Lowering Agents

PCSK9 plays a critical role in lipid metabolism by promoting the degradation of LDLR. When unchecked, this process elevates circulating LDL-C levels, contributing to cardiovascular disease, viral infections, cancer, and sepsis [12]. PCSK9 inhibitors have emerged as a cornerstone of modern lipid-lowering strategies, with multiple therapeutic approaches.

Emerging developments in PCSK9 inhibition include oral and vaccine-based strategies. MK-0616, an oral peptide macrocyclic compound, binds PCSK9 and inhibits its interaction with LDLR, achieving LDL-C reductions comparable to injectable inhibitors in early trials [88]. After the phases 1 and 2 the safety profile remained favorable, with adverse event rates of 39–44% across all groups including placebo and discontinuation rates of only 0–3%. Currently, three Phase 3 trials are ongoing and completion is expected in 2029 [35,88]. Vaccine-based approaches, meanwhile, induce antibodies against PCSK9, reducing serum lipid levels in hypercholesterolemia models, with variable efficacy still under investigation [90]. The vaccine approach addresses key limitations of current monoclonal antibody therapy, including high cost, frequent high-dose administration requirements, potential anti-drug immunity, and loss of efficacy, potentially providing longer-lasting protection compared to repeated mAb injections [90]. Table 4 underscores the diversity within the PCSK9 inhibitor class. Evolocumab and alirocumab remain the standard of care, with well-established efficacy and safety profiles while emerging agents like ongericimab and MK-0616 promise higher efficacy and accessibility. The development pipeline shows vaccine approaches remaining in early preclinical stages but showing promising proof-of-concept data [35,89].

Table 4: Characteristics of PCSK9 inhibitors.

| Agent | Mechanism of Action | LDL-C Reduction | Lp(a) Reduction | Administration | Side Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolocumab | mAb against PCSK9 | 50–60% | 25–30% | Subcutaneous injection (monthly or bimonthly) | Injection site reactions, flu-like symptoms | [34,35,90] |

| Alirocumab | mAb against PCSK9 | 50–60% | 25–30% | Subcutaneous injection (biweekly or monthly) | Injection site reactions, flu-like symptoms | [34,35,90] |

| Inclisiran | siRNA targeting PCSK9 mRNA | 50–55% | Under study | Subcutaneous injection (biannual) | Injection site reactions | [91,92] |

| Ongericimab | Novel anti-PCSK9 mAb | 69.4–80.6% (in HeFH) | Under study | Under development | Under study | [85] |

| MK-0616 | Oral peptide macrocyclic PCSK9 inhibitor | 41–61% (dose-dependent) | Under study | Oral | Well tolerated; similar adverse event rates to placebo (39–44%) | [88] |

| PCSK9 Vaccines | Induce antibodies against PCSK9 | 14.4–19.6% (preclinical) | Under study | Injection (vaccination schedule) | No apparent side effects in preclinical studies | [89] |

Comprehensive overview of PCSK9 inhibitor mechanisms, efficacy profiles, and administration protocols, representing second-generation lipid-lowering therapeutics for residual cardiovascular risk reduction. Most of the information for this table was studied in European populations. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); mAb, monoclonal antibody; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; siRNA, small interfering ribonucleic acid; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; MK-0616, Enlicitide chloride.

Genetic insights further support PCSK9 inhibition. Mendelian randomization studies link PCSK9-lowering variants to longer lifespans and reduced stroke risk [72], while trans-genetic variations outside the PCSK9 gene influence plasma levels, suggesting broader modulatory potential [55]. Clinically, PCSK9 inhibitors benefit diverse populations, including homozygous HoFH patients with residual LDLR activity, though LDL-C reductions may be less pronounced [36].

Combination therapies also show promise. In post-acute coronary syndrome patients, combining PCSK9 inhibitors with statins stabilizes plaques via reduced apolipoprotein B levels, extending their cardiovascular benefits [93]. Dual therapy with evolocumab and inclisiran enhances LDL-C reduction in high-risk patients with PCSK9 gain-of-function mutations [94]. Safety data remain favorable, with systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regression analyses demonstrating no significant increase in neurocognitive adverse events [95], supporting long-term use in high-risk groups.

Beyond PCSK9, novel lipid-lowering agents target ACLY, ApoC-III, ANGPTL3 and Lp(a) mRNA, addressing distinct lipid metabolism pathways and providing therapeutic alternatives for patients with statin intolerance or suboptimal response to statin therapy, each target offeres advantages for specific patient populations and dyslipidemia phenotypes. Table 5 describes these agents and highlights a shift toward precise molecular targeting in lipid management.

Table 5: Characteristics of inhibitors for novel targets.

| Inhibitor | Target | Mechanism of Action | Effects | Administration | Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bempedoic acid | ACLY | cholesterol synthesis upstream of HMG-CoA reductase | LDL-C reductiof 15–25%. Reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events | Daily oral administration | Minimizes muscle-related side effects | [1,37,38] |

| Volanesorsen | ApoC-III | LPL activity enhanced through reduction of ApoC-III mRNA | 70–90% TG reduction. Decreases in VLDL-C, Apo-B48, and ApoC-III | Injections | There could be injection site reactions and thrombocytopenia | [71,96,97,98] |

| IONIS ANGPTL3-LRx | ANGPTL3 | Reducing ANGPTL3 enhances LPL activity, lowering TG levels | TG reduction. 50% LDL-C reduction in HoFH patients | Injections | There could be injection site reactions and thrombocytopenia | [45,71,90,97] |

| IONIS APO(a)-LRx and Pelacarsen | Lp(a) mRNA | Lp(a) levels lowered 80–90% in clinical trials | Lp(a) reduction | Injections | Under study | [91] |

ACLY functions as an enzyme integral to lipid metabolism, converting citrate into acetyl-CoA and operating upstream of HMG-CoA reductase in the cholesterol synthesis pathway [38]. Bempedoic acid serves as a direct and competitive inhibitor of ACLY, functioning as a prodrug requiring transformation by very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase-1 (ACSVL1) enzyme in hepatocytes. Upon hepatic activation, bempedoic acid converts to its active metabolite bempedoic acid-CoA, which inhibits cholesterol synthesis [1]. Inhibition of ACLY reduces hepatic cholesterol synthesis, leading to increased LDL receptor expression and enhanced LDL-C uptake [1,38]. The CLEAR Outcomes trial demonstrated significant cardiovascular benefits in 13,970 patients followed for a median of 40.6 months, the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization) occurred in 11.7% versus 13.3% with placebo (HR = 0.87, 95%CI 0.79–0.96), with a number needed to treat of 63 [1]. Phase III CLEAR studies demonstrated consistent LDL-C reductions. General pharmacogenetic factors affecting lipid-lowering agents include CYP450 polymorphisms [1].

ApoC-III is a 79 amino acid peptide synthesized in liver and intestine, serving as a major component of circulating lipoproteins, particularly chylomicrons and VLDL [45]. ApoC-III exerts multiple pathophysiological effects: it inhibits lipolysis by blocking lipoprotein lipase (LPL)-mediated hydrolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, impairs hepatic catabolism by reducing hepatic uptake of TRLs via LDL receptors and hepatic sulfate proteoglycans, and promotes VLDL secretion by enhancing assembly and secretion of VLDL-like particles in hepatocytes under lipid-rich conditions [45]. Phase III trials for Volanesorsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting ApoC-III, involving 179 patients showed 70–80% triglyceride reduction with significant pancreatitis reduction (1 case versus 9 in placebo, p = 0.0185) [45]. Loss-of-function APOC3 variants provide strong evidence for therapeutic targeting. Studies in the Amish population revealed that APOC3 mutation carriers had very low plasma triglyceride levels and demonstrated 40% reduction in coronary artery disease risk in Mendelian randomization studies [45]. Meta-regression analysis identified age as a predictor of response, with higher age associated with less significant triglyceride reduction, while LPL gene mutation status did not significantly impact treatment efficacy [98].

ANGPTL3 is a secreted protein exclusively expressed in the liver that forms intracellular complexes with ANGPTL8, enhancing ANGPTL3 function [45]. The protein inhibits lipoprotein lipase, hepatic lipase, and endothelial lipase, leading to reduced lipolysis of plasma lipoprotein triglycerides and phospholipids [71,90]. ANGPTL3 silencing reduces biosynthesis, lipidation, and secretion of VLDL by human hepatocytes, and may increase uptake while decreasing hepatic secretion of ApoB-containing lipoproteins [71]. ANGPTL3 controls VLDL catabolism upstream of LDL, and its inhibition lowers LDL-C levels by limiting LDL particle production through delayed VLDL catabolism [97]. For Evinacumab, a monoclonal antibody against ANGPTL3, Phase III trial in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia showed 49% LDL-C reduction versus placebo at 24 weeks, with additional reductions in total cholesterol (−48.4%), ApoB (−36.9%), non-HDL-C (−51.7%), and triglycerides (−50.4%) [91]. Notably, significant effects were observed even in null/null mutation patients [91]. Homozygous loss-of-function mutations are associated with familial combined hypolipoproteinemia, characterized by low TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C, but reduced overall atherosclerosis risk despite HDL-C reduction [71,91]. Rare loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3 are consistently associated with favorable lipid profiles and decreased cardiovascular risk, supporting the therapeutic rationale for ANGPTL3 inhibition [97].

Lp(a) is a cholesterol-rich lipoprotein bound by apoB in addition to apoliprotein(a) (apo[a]). The development of an ASO against apo(a) provides a potential means of directly targeting Lp(a) [79]. ASOs act by directly binding to their complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, resulting in RNase-mediated degradation IONIS-APO(a)-LRx underwent a phase 2 trial with a dose-dependent response in decrease in Lp(a). Mean percent decreases of Lp(a) among other dosing regimens ranged from 35 to 72% compared with 6% observed with placebo at 6 months [79]. Adverse events occurred in 90% of patients in the treatment groups and 83% of those in the placebo group, serious adverse events occurred in 10% of patients receiving active therapy and 2% of those receiving placebo. Pelacarsen is a siRNA that also targets Lp(a) and is still undergoing phase 1 studies.

Comprehensive overview of inhibitors used for novel targets in ASCVD treatment, mechanisms of action for lipid reduction and mechanisms for drug administration. The majority of the information in this table comes from european population studies. ACLY, ATP citrate lyase; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ApoC-III, apolipoprotein C-III; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; mRNA, messenger RNA; TG, triglycerides; VLDL-C, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Apo-B48, apolipoprotein B-48; ANGPTL3, angiopoietin-like protein 3; HoFH, homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a).

RNA-based therapies leverage technologies to modulate lipid metabolism, expanding options for dyslipidemia management, especially in refractory cases [13]. These emerging RNA-based lipid-lowering agents offer new opportunities for managing ASCVD risk, particularly in patients with inadequate response to or intolerance of standard therapies.

The integration of these technologies into clinical practice represents a paradigm shift in the treatment and prevention of dyslipidemia [99,100]. Key RNA-based therapies are shown in Table 6 and further analyzed. However, long-term safety and efficacy data, as well as studies on hard cardiovascular outcomes, are still needed for many of these agents. For instance, Arnold et al. [101] notes that cardiovascular outcome trials for inclisiran are still pending. Furthermore, the high cost of some of these therapies, particularly mAbs and RNA-based therapies, may limit their widespread use and necessitate careful patient selection based on risk-benefit and cost-effectiveness considerations. Most of the information reported for RNA-based therapies comes from European and Asian population.

Table 6: Key RNA-based therapies for lipid management.

| Therapy Type | Agent | Target | Mechanism | Clinical Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASOs | Mipomersen | ApoB-100 mRNA | Prevents translation of ApoB-100 | Colesterol reduction via VLDL production targeting | [44,90] |

| vupanorsen | ANGPTL3 mRNA | Prevents translation of ANGPTL3 | LDL-C and TG reduction | [3] | |

| Volanesorsen | ApoC-III mRNA | Prevents translation of ApoC-III | TG reduction (up to 90%), VLDL-C, ApoB-48 and ApoC-III reduction. Effective for severe hypertriglyceridemia | [45,71,98] | |

| IONIS-APO(a)-LRx/Pelacarsen | Apo(a) mRNA | Prevents translation of Apo(a) | Lp(a) reduction (80–90%) | [29] | |

| siRNA | Inclisiran | PCSK9 mRNA | Silences PCSK9 expression. inhibits hepatic synthesis of PCSK9 | LDL-C reduction (~50%). It can be used in dual therapy with evolocumab in FH patients with PCSK9 gain-of-function mutations | [1,35,91,94,101,102] |

| ARO-ANG3 | ANGPTL3 mRNA | Silences ANGPTL3 expression | TG and LDL-C reduction | [71] | |

| ARO-APOC3 (plozasiran) | ApoC-III mRNA | Silences ApoC-III expression | Significant reduction of TG | [71] | |

| Olpasiran | Lp(a) mRNA | Silences Lp(a) expression | Lp(a). Specifically designed for Lp(a) reduction | [92] | |

| Gene Editing | TALEN mRNA in lipid nanoparticles | LPA gene | Disrupts LPA gene | Lp(a) reduction (>80% for ≥5 weeks) | [103] |

| Lentiviral Vector | IDOL-shRNA | IDOL mRNA | Silences IDOL expression | Cholesterol reduction | [104] |

Emerging RNA-targeted therapeutic modalities including antisense oligonucleotides and siRNA approaches for precise modulation of lipid metabolism pathways and novel cardiovascular risk factors. ASOs, antisense oligonucleotides; ApoB-100, apolipoprotein B-100; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; ANGPTL3, angiopoietin-like protein 3; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; ApoC-III, apolipoprotein C-III; VLDL-C, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ApoB-48, apolipoprotein B-48; Apo(a), apolipoprotein(a); Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); siRNA, small interfering ribonucleic acid; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nucleases; LPA, lipoprotein(a) gene; IDOL, inducible degrader of the LDL receptor; shRNA, short hairpin ribonucleic acid.

A more comprehensive understanding of genetic determinants of lipid metabolism continues to inform the development of novel therapeutic approaches. Kim et al. [73] discusses new, novel lipid-lowering agents for reducing cardiovascular risk beyond statins, many of which are inspired by genetic insights. Giuliani et al. [78] studied the association between single nucleotide polymorphisms, including miR-499a genetic variants, and dyslipidemia in subjects treated with pharmacological or phytochemical lipid-lowering agents, highlighting the potential role of microRNA-related genetic variants in lipid metabolism.

Large-scale genetic analyses add further complexity to lipid regulation insights. Combining genetics with combinatorial RNA interference (RNAi) across 240,970 exomes, researchers have identified gene pairs like APOB-PCSK9 and APOB-LPL with additive effects on plasma lipid levels, nominating targets for combination therapies [65]. Islam et al. [105] have advanced risk assessment by characterizing LDLR gene variants on a large scale, enhancing cardiovascular disease prevention capabilities. There is a shift in the risk profiles of atherosclerotic disease caused by the widespread use of lipid lowering therapies. High-risk atherosclerotic plaques, characterized by lipid-rich cores, are key contributors to acute coronary syndromes and sudden cardiac death [106].

Future research priorities to maximize genomics’ clinical impact include:

- 1.Enhanced Genetic Risk Scores: Incorporating both common and rare variants, plus gene-gene interactions (e.g., APOB-PCSK9 and APOB-LPL), to refine ASCVD risk prediction [65], potentially accelerated by validated surrogate atherosclerosis measures that could enable clinical trials with fewer participants and shorter duration [42].

- 2.Pharmacogenomic Algorithms: Developing tools to guide drug selection and dosing based on individual genetic profiles, accounting for gene interactions, polygenic effects, and ethnic differences [65,69]. Proietti et al. [107] highlights interethnic differences in common pharmacogenetic variants between Czech and Finnish populations, suggesting the utility of pharmacogenomics informed (PGx-informed) prescribing in diverse populations.

- 3.Point-of-Care Testing: Implementing rapid genetic tests for variants in key genes like PCSK9 and ANGPTL3 to enable immediate clinical decision-making [5,79]. Brown et al. [79] evaluate expanded genetic testing for FH, finding that in rare cases, it can provide answers for patients with minimal probability of variants of uncertain significance.

- PCSK9 inhibitors, such as evolocumab, alirocumab, and inclisiran, provide substantial LDL-C reduction (50–60%) and are particularly beneficial for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or those who are statin-intolerant, with emerging oral formulations and vaccine-based strategies showing promise.

- Population-specific patterns emerge in the literature, with genetic variant studies showing enrichment in Asian populations while emerging lipid-lowering agent studies predominantly derive from European populations. Ethnical origin of results may affect its use across different population and highlights the need for expanding pharmacogenomic research to include diverse global populations to ensure therapeutic approaches are applicable across different ancestry groups.

- Genetic profiling shows promise for enabling personalized lipid-lowering strategies, with specific variants in LDLR, APOE, PCSK9, ANGPTL3, CYP3A4, SLCO1B1, and ABCB1 demonstrating associations with differential therapeutic responses and adverse event risk This suggests potential for optimizing treatment selection and monitoring through pharmacogenomic testing.

- Specific genetic variants in HMGCR (e.g., rs12916, rs17238484), APOE (e.g., E2/E3/E4, p.(Leu167del)), and LDLR (e.g., rs200727689, rs72658860) are associated with differential responses to statins and other lipid-lowering therapies, indicating that pharmacogenomic testing could optimize treatment efficacy and safety.

- Beyond LDL-C reduction, targeting elevated Lipoprotein(a), TG-rich lipoproteins, dysregulated HDL, inflammation, and altered intestinal lipid metabolism represents critical approaches to address residual cardiovascular risk, with therapies including RNA-based treatments targeting APOC3 and LPA, and ANGPTL3 inhibitors showing promise for comprehensive risk reduction.

- RNA-based therapies, including antisense oligonucleotides and siRNA targeting APOC3, ANGPTL3, and LPA, offer novel mechanisms to reduce TG and Lp(a) levels, addressing residual cardiovascular risk not fully mitigated by LDL-C lowering alone.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Miguel Meñaca-Puentes contributed to the conceptualization of the research framework, preparation of the initial manuscript draft, and contributed to the writing and revision of the final article. Juan-Camilo Arias-Ospina participated in the preparation of the manuscript draft and contributed to the writing and revision of the final article. Narmer F. Galeano provided critical revisions, served as the decisive authority for solving disagreements and conducted comprehensive manuscript reviews. Reinel Tabares-Soto contributed to the conceptualization of the research framework and provided supervisory oversight throughout the project. Carlos Alberto Ruiz Villa provided supervisory guidance and oversight during the research and manuscript preparation phases. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable, as this is a narrative review based on existing literature.

Ethics Approval: Not required, as this is a narrative review without original human or animal data.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.070423/s1.

Glossary

| The rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis that catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate. This enzyme serves as the primary therapeutic target for statin medications and exhibits genetic polymorphisms that influence individual treatment response variability. | |

| A hepatically-secreted glycoprotein that functions as an endogenous inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase, thereby regulating triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Loss-of-function mutations in ANGPTL3 are associated with familial combined hypolipidemia and reduced atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. | |

| Single-stranded DNA molecules of 12–25 nucleotides designed to bind complementary messenger RNA sequences, thereby preventing translation of target proteins. In lipid metabolism, ASOs targeting PCSK9, apolipoprotein C-III, and lipoprotein(a) have demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy. | |

| A multifunctional protein essential for lipoprotein metabolism and cholesterol homeostasis. The three common isoforms (E2, E3, E4) exhibit differential effects on lipid levels and cardiovascular risk, with significant implications for statin therapy efficacy and Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility. | |

| A pathological condition characterized by the formation of atherosclerotic plaques within arterial walls, leading to clinical manifestations including coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease. ASCVD represents the leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. | |

| An autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by defective low-density lipoprotein receptor function, resulting in markedly elevated LDL-cholesterol levels from birth and premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. FH affects approximately 1 in 250 individuals globally. | |

| The cholesterol content of low-density lipoproteins, representing the primary target for cardiovascular risk reduction. LDL-C exhibits a continuous, log-linear relationship with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk across diverse populations. | |

| A cell surface receptor responsible for the uptake of LDL particles from plasma through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mutations in the LDLR gene constitute the most common cause of familial hypercholesterolemia. | |

| A serine protease that regulates cholesterol homeostasis by promoting degradation of LDL receptors. PCSK9 represents a major therapeutic target, with both genetic and pharmacological inhibition demonstrating significant cardiovascular benefits. | |

| A class of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors that represent the cornerstone of lipid-lowering therapy. Statins reduce cholesterol synthesis, upregulate LDL receptor expression, and demonstrate consistent cardiovascular benefits across diverse populations. |

References

1. Ferri N , Ruscica M , Fazio S , Corsini A . Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering drugs: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2024; 13( 4): 943. doi:10.3390/jcm13040943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang N , Woodward M , Huffman MD , Rodgers A . Compounding benefits of cholesterol-lowering therapy for the reduction of major cardiovascular events: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022; 15( 6): e008552. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ling P , Zheng X , Luo S , Ge J , Xu S , Weng J . Targeting angiopoietin-like 3 in atherosclerosis: from bench to bedside. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021; 23( 9): 2020– 34. doi:10.1111/dom.14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mohammed KQ , Ouda MH , Jubair S . Impact of PCSK9 gene polymorphism on atorvastatin efficacy in Iraqi hyperlipidemic patients. Gene Rep. 2025; 39: 102181. doi:10.1016/j.genrep.2025.102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Das KC , Hossain MU , Moniruzzaman M , Salimullah M , Akhteruzzaman S . High-risk polymorphisms associated with the molecular function of human HMGCR gene infer the inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis. Biomed Res Int. 2022; 2022: 4558867. doi:10.1155/2022/4558867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Adachi K , Ohyama K , Tanaka Y , Sato T , Murayama N , Shimizu M , et al. High hepatic and plasma exposures of atorvastatin in subjects harboring impaired cytochrome P450 3A4 ∗ 16 modeled after virtual administrations and possibly associated with statin intolerance found in the Japanese adverse drug event report database. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2023; 49: 100486. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2022.100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Čereškevičius D , Zabiela V , Aldujeli A , Lesauskaitė V , Zubielienė K , Raškevičius V , et al. Impact of CYP2C19 gene variants on long-term treatment with atorvastatin in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25( 10): 5385. doi:10.3390/ijms25105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bi Q , Zhou X , Lu Y , Fu W , Wang Y , Wang F , et al. Polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein E gene affect response to atorvastatin therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 9: 1024014. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.1024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Civeira F , Martín C , Cenarro A . APOE and familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2024; 35( 4): 195– 9. doi:10.1097/mol.0000000000000937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Di Taranto MD , Giacobbe C , Fortunato G . Familial hypercholesterolemia: a complex genetic disease with variable phenotypes. Eur J Med Genet. 2020; 63( 4): 103831. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gratton J , Humphries SE , Futema M . Prevalence of FH-causing variants and impact on LDL-C concentration in European, south Asian, and African ancestry groups of the UK biobank-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023; 43( 9): 1737– 42. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.123.319438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ajoolabady A , Pratico D , Mazidi M , Davies IG , Lip GYH , Seidah N , et al. PCSK9 in metabolism and diseases. Metabolism. 2025; 163: 156064. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2024.156064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abou-Karam R , Cheng F , Gady S , Fahed AC . The role of genetics in advancing cardiometabolic drug development. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2024; 26( 5): 153– 62. doi:10.1007/s11883-024-01195-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Page MJ , McKenzie JE , Bossuyt PM , Boutron I , Hoffmann TC , Mulrow CD , et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372: n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Llewellyn A , Simmonds M , Marshall D , Harden M , Woods B , Humphries SE , et al. Efficacy and safety of statins, ezetimibe and statins-ezetimibe therapies for children and adolescents with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: systematic review, pairwise and network meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Atherosclerosis. 2025; 401: 118598. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.118598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Martinsen MH , Klausen IC , Tybjaerg-Hansen A , Hedegaard BS . Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia in a kindred of Syrian ancestry. J Clin Lipidol. 2020; 14( 4): 419– 24. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2020.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lauritzen T , Munkhaugen J , Bergan S , Peersen K , Svarstad AC , Andersen AM , et al. The atorvastatin metabolite pattern in muscle tissue and blood plasma is associated with statin muscle side effects in patients with coronary heart disease; an exploratory case-control study. Atheroscler Plus. 2024; 55: 31– 8. doi:10.1016/j.athplu.2024.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Reeskamp LF , Tromp TR , Huijgen R , Stroes ESG , Hovingh GK , Grefhorst A . Statin therapy reduces plasma angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) concentrations in hypercholesterolemic patients via reduced liver X receptor (LXR) activation. Atherosclerosis. 2020; 315: 68– 75. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.11.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kononov S , Azarova I , Klyosova E , Bykanova M , Churnosov M , Solodilova M , et al. Lipid-associated GWAS loci predict antiatherogenic effects of rosuvastatin in patients with coronary artery disease. Genes. 2023; 14( 6): 1259. doi:10.3390/genes14061259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kononov S , Mal G , Azarova I , Klyosova E , Bykanova M , Churnosov M , et al. Pharmacogenetic loci for rosuvastatin are associated with intima-media thickness change and coronary artery disease risk. Pharmacogenomics. 2022; 23( 1): 15– 34. doi:10.2217/pgs-2021-0097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu N , Yang G , Liu Y , Hu M , Cai Y , Hu Z , et al. Effect of cytochrome P450 7A1 (CYP7A1) polymorphism on lipid responses to simvastatin treatment. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020; 75( 2): 168– 73. doi:10.1097/FJC.0000000000000774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jiang L , Stoekenbroek RM , Zhang F , Wang Q , Yu W , Yuan H , et al. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in China: genetic and clinical characteristics from a real-world, multi-center, cohort study. J Clin Lipidol. 2022; 16( 3): 306– 14. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2022.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Andrianto , Puspitasari M , Ardiana M , Dewi IP , Shonafi KA , Kusuma Wardhani LF , et al. Association between single nucleotide polymorphism SLCO1B1 gene and simvastatin pleiotropic effects measured through flow-mediated dilation endothelial function parameters. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2022; 16: 17539447221132367. doi:10.1177/17539447221132367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Abdulfattah SY , Abdullah SJ , Alsaffar HB . A study to explore the LDLR gene polymorphisms contribute to atorvastatin response in a sample of Iraqi population with atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Karbala Int J Mod Sci. 2020; 6( 1): 44– 52. doi:10.33640/2405-609x.1361 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Abdulfattah SY , Alagely HS , Samawi FT . Influence of the rs4238001 genetic polymorphism of the SR-B1 gene on serum lipid levels and response to rosuvastatin in myocardial infarction Iraqi patients. Biochem Genet. 2024; 62( 5): 3557– 67. doi:10.1007/s10528-023-10613-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Shi Z , Han S . Personalized statin therapy: targeting metabolic processes to modulate the therapeutic and adverse effects of statins. Heliyon. 2025; 11( 1): e41629. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Corral P , Berg G , Zago V , Bursztyn M , López GI , Schreier LE . Effects of lipid-modifying pharmacological agents on circulating PCSK9 in severe and familial hypercholesterolemic (FH) patients in Argentina. Atherosclerosis. 2022; 355: 256– 7. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.06.974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ghiasvand T , Karimi J , Khodadadi I , Yazdi A , Khazaei S , Kichi ZA , et al. The interplay of LDLR PCSK9 and lncRNA-LASER genes expression in coronary artery disease: implications for therapeutic interventions. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2025; 177: 106969. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2025.106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Averna M , Cefalù AB . LP(a): the new marker of high cardiovascular risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025; 35( 3): 103845. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2024.103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. University KSM , Khazova EV , Bulashova OV , University KSM , Valeeva EV , University KSM , et al. Cetp rs247616 polymorphism in patients with chronic heart failure and coronary heart disease: traits of lipid metabolism and effectiveness of statin therapy. Bull Contemp Clin Med. 2023; 16( 6): 67– 77. doi:10.20969/vskm.2023.16(6).67-77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ye Z , Deng J , Wu X , Cai J , Li S , Chen X , et al. Association of statins use and genetic susceptibility with incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2025; 12( 2): 100025. doi:10.1016/j.tjpad.2024.100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Baptista ECMS , Pereira CSGP , García PA , Ferreira ICFR , Barreira JCM . Combined action of dietary-based approaches and therapeutic agents on cholesterol metabolism and main related diseases. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2025; 66: 51– 68. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2025.01.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li S , Schooling CM . Investigating the effects of statins on ischemic heart disease allowing for effects on body mass index: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2022; 12( 1): 3478. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-07344-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nurmohamed N , Reeskamp R , Bom M , Planken N , Driessen R , Van Diemen P , et al. Plaque burden in two adolescents with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: turning back the clock with aggressive LDL-c lowering. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021; 77( 18): 126. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(21)01485-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Corsini A , Ginsberg HN , Chapman MJ . Therapeutic PCSK9 targeting: inside versus outside the hepatocyte? Pharmacol Ther. 2025; 268: 108812. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2025.108812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pirillo A , Catapano AL , Norata GD . Monoclonal antibodies in the management of familial hypercholesterolemia: focus on PCSK9 and ANGPTL3 inhibitors. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021; 23( 12): 79. doi:10.1007/s11883-021-00972-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Alonso R , Arroyo-Olivares R , Díaz-Díaz JL , Fuentes-Jiménez F , Arrieta F , de Andrés R , et al. Improved lipid-lowering treatment and reduction in cardiovascular disease burden in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: the SAFEHEART follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 2024; 393: 117516. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Capuozzo M , Ottaiano A , Cinque C , Farace S , Ferrara F . Cutting-edge lipid-lowering pharmacological therapies: improving lipid control beyond statins. Hipertens Riesgo Vasc. 2025; 42( 2): 116– 27. doi:10.1016/j.hipert.2024.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Agha AM , Jones PH , Ballantyne CM , Virani SS , Nambi V . Greater than expected reduction in low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) with bempedoic acid in a patient with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH). J Clin Lipidol. 2021; 15( 5): 649– 52. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2021.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mszar R , Bart S , Sakers A , Soffer D , Karalis DG . Current and emerging therapies for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk reduction in hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Med. 2023; 12( 4): 1382. doi:10.3390/jcm12041382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ying Q , Chan DC , Pang J , Croyal M , Blanchard V , Krempf M , et al. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid ethyl esters on postprandial arterial elasticity in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2023; 55: 174– 7. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.03.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]