Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Association Between Blood Biomarkers and Hemodynamic Parameters in Adolescents and Adults After the Fontan Procedure: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Department of Pediatrics, The Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, 105-8471, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Kentaro Kogawa. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Insights into Congenital Heart Disease: Pathophysiology, Biomarkers, and Future Directions)

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 659-671. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.073864

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 23 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Background: An increasing number of patients with Fontan circulation are reaching adulthood; however, long-term outcomes remain limited by Fontan failure, which is characterized by elevated central venous pressure (CVP) and reduced cardiac output. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW), a readily available hematological parameter, is a known prognostic marker of heart failure. However, its relationship with invasive hemodynamics in adolescent and adult Fontan patients has not been fully examined. Objectives: To clarify the association between RDW and invasive hemodynamic indices in adolescent and adult Fontan patients and assess the utility of RDW as a noninvasive circulatory marker. Methods: This single-center retrospective study included consecutive Fontan patients aged ≥16 years who underwent routine cardiac catheterization ≥5 years after surgery, between June 2014 and July 2025. Laboratory data and catheter-derived hemodynamics were also analyzed. The primary endpoint was the correlation between RDW and CVP, and the secondary endpoint was the correlation between RDW and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). Results: Forty patients (median age: 22 years) were analyzed. The median RDW was 13.3%, and the median CVP was 11.0 mmHg. RDW correlated positively with CVP (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001) and negatively with ScvO2 (ρ = –0.66, p < 0.001) and the cardiac index (ρ = –0.34, p = 0.03). Patients with elevated RDW (>14.5%) had higher CVP (14.5 vs. 10.5 mmHg, p < 0.001) and lower ScvO2 (63.8% vs. 76.1%, p < 0.001), compared with those with normal RDW. Multivariable analysis identified RDW as an independent predictor of ScvO2 (p < 0.001). Conclusions: In adolescents and adults after the Fontan procedure, RDW was significantly associated with elevated CVP and reduced ScvO2 and independently predicted impaired oxygen delivery. RDW is inexpensive, widely accessible, and may serve as a practical noninvasive biomarker for the early detection of Fontan failure and the optimization of invasive testing and interventions during long-term follow-up.Keywords

The Fontan procedure, first introduced in 1968, is an established surgical treatment for patients with single-ventricle physiology. Advances in medical and surgical techniques have enabled the survival of a growing number of adolescents and adults [1,2,3,4]. Globally, an estimated 50,000–70,000 individuals live with Fontan circulation, of whom approximately 40% are adults [5]. Although the 30-year survival rate has improved to approximately 85% [2,6,7], serious complications related to hemodynamic abnormalities, primarily elevated central venous pressure (CVP) and reduced cardiac output, remain common [5,8,9]. These complications include arrhythmias, thromboembolisms, hepatic dysfunction, and protein-losing enteropathy, all of which significantly worsen long-term outcomes [5,10]. Collectively, these conditions are referred to as “Fontan failure,” the most critical determinant of premature death or indication for heart transplantation [11].

The population of patients living with Fontan circulation is expected to grow substantially in the coming decades. Rychik et al. projected that the number of survivors will double within 20 years [5], and Plappert et al., using epidemiologic data from 11 countries, estimated that the proportion of adults will increase from 55% in 2020 to 64% by 2030 [12]. With the increasing prevalence and aging of this population [12,13,14], early detection and preventive interventions for circulatory failure have become central challenges in the management of adult congenital heart disease. However, standardized methods for the comprehensive assessment of Fontan circulation remain insufficient. A comprehensive review published in 2025 concluded that the available evidence was inadequate with regard to the establishment of evidence-based recommendations for evaluating Fontan physiology [15]. This underscores the urgent need to develop novel strategies for hemodynamic assessment.

Accurate evaluation of hemodynamic parameters, such as CVP, central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2), and the cardiac index (CI), is essential for the optimal management of Fontan patients [5]. However, these measurements can only be obtained through invasive cardiac catheterization, which is limited by procedural risks and patient burden, making frequent monitoring impractical. Furthermore, these parameters often lack strong correlations with adverse outcomes unless they are markedly abnormal [5]. Therefore, attention has turned toward less invasive blood-based biomarkers. B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP), widely used for heart failure assessment in biventricular circulation, demonstrate limited diagnostic accuracy in the Fontan population due to preload reduction [16,17,18].

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW), a measure of anisocytosis readily obtained from routine complete blood counts (CBC), has emerged as a potential biomarker of cardiovascular disease. An elevated RDW is an established predictor of mortality in heart failure and an independent prognostic factor in myocardial infarction and pulmonary hypertension [19,20,21]. Mechanistically, increased RDW is thought to reflect impaired erythropoiesis, inflammation-mediated inhibition of red blood cell maturation, and oxidative stress, all of which are pathophysiologically linked to heart failure [22,23,24]. Its accessibility, noninvasiveness, and low cost make RDW an attractive biomarker [15]. However, evidence regarding the clinical significance of RDW in the Fontan population remains limited. Kojima et al. demonstrated a significant correlation between RDW and CVP in pediatric Fontan patients (mean age: 4.1 ± 2.8 years) [16]. However, as reference values for CBC parameters differ between children and adults, extrapolation to adult patients is not straightforward. Kramer et al. reported an association between elevated RDW and Fontan failure in adults [11], and Fuentes et al. identified RDW ≥ 14.5% as a predictor of Fontan failure [25]. Nevertheless, these studies defined Fontan failure primarily based on clinical symptoms rather than on quantitative hemodynamic measurements. In Kramer’s study, catheterization data were missing in 26% of the nonfailing group, limiting the ability to examine the correlations between RDW and specific hemodynamic parameters [11]. Recent reviews have highlighted the need for more rigorous studies to establish the predictive value of RDW in this population [15].

Given these gaps, clarifying the quantitative relationship between hematological indices, particularly RDW, and invasive hemodynamic parameters in adolescents and adults with Fontan circulations is essential. Specifically, investigating the correlation between CVP and ScvO2 may provide a basis for developing new, less invasive assessment strategies. Therefore, we aimed to clarify the quantitative relationship between RDW and invasive hemodynamic parameters in adolescents and adults with Fontan circulation.

This retrospective observational study included adolescent and adult patients (≥16 years of age) with a history of the Fontan procedure who underwent routine cardiac catheterization at Jikei University Hospital between June 2014 and July 2025. Patients were identified from the institutional Fontan database. Only the most recent examinations were analyzed to maintain data independence for patients who had undergone multiple catheterizations during the study period.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ≥5 years after the Fontan procedure; (2) cardiac catheterization performed as part of routine follow-up; and (3) availability of blood test results obtained within 48 h before the procedure. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) missing laboratory or hemodynamic data, (2) transfusion of blood products within 30 days prior to catheterization, (3) emergency catheterization for acute illness, and (4) history of hematologic disease. These criteria were applied to ensure reliable hematological parameters and to evaluate patients in a clinically stable state.

Clinical and laboratory data were systematically extracted from medical records and institutional databases. Collected variables included demographic and baseline characteristics (age, sex, body surface area, underlying cardiac diagnosis, surgical history, comorbidities, and medications); laboratory values (hemoglobin, platelet count, RDW, lymphocyte count, brain natriuretic peptide, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase); and hemodynamic indices (CVP, arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), ScvO2, CI, and pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRi)). Ejection fraction (EF) of the dominant systemic ventricle was obtained from catheterization-derived measurements. The FIB-4 index was calculated using the formula: FIB-4 = (age [years] × AST [U/L])/(platelet count [10⁹/L] × √ALT [U/L]). All laboratory samples were obtained prior to catheterization. To minimize observer bias, data analysis was independently performed by multiple specialists following standardized protocols.

2.4 Study Endpoints and Hemodynamic Definitions

The primary endpoint was the correlation between RDW and CVP. Secondary endpoints include the following: (1) correlations of RDW with ScvO2 and CI, and (2) the prevalence of hemodynamic abnormalities in patients with elevated RDW (>14.5%). The CVP was defined as the mean pressure measured in the superior or inferior vena cava. ScvO2 was determined from samples obtained from both the superior and inferior vena cava, and CI was calculated using the Fick method. An at-risk range for Fontan failure was defined as CVP ≥ 15 mmHg or CI < 2.5 L/min/m2, consistent with previous reports and clinical relevance [26,27,28].

Continuous variables were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. As several key variables, including RDW, CVP, and BNP, showed significant deviations from normality (all p < 0.05), associations between laboratory parameters and hemodynamic indices (CVP, ScvO2) were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Bootstrap resampling with 10,000 iterations was performed to estimate robust 95% confidence intervals for correlation coefficients [29]. Patients were stratified into two groups according to RDW (≤14.5% vs. >14.5%), and group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Multivariable linear regression analyses were conducted with CVP and ScvO2 as dependent variables to evaluate the independent predictive value of RDW. Covariates included established confounders known to influence RDW [16], such as sex and hemoglobin, serum albumin, and C-reactive protein (CRP). Model fit was evaluated using R2 and adjusted R2. Effect sizes were quantified using Cohen’s f2. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of findings. Outliers were identified using the interquartile range (IQR) method (1.5 × IQR), and correlation analyses were repeated after their exclusion. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value of <0.05, and 95% confidence intervals were reported. All statistical analyses were performed using Easy R (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Easy R is a modified version of the R Commander with additional functions for biostatistics [30].

2.6 Ethical Compliance Statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jikei University Hospital (approval number: 37-232[12875]). Given the retrospective design, the requirement for written informed consent was waived, and patient notifications were provided via an opt-out process.

A total of 40 patients met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed. The median age at the time of catheterization was 22 years, and approximately 70% of the participants were male. The median age at Fontan completion was 2.5 years, with a median follow-up of 19.5 years after surgery. The most common underlying diagnosis was a single right ventricle (n = 10, 25.0%), followed by a double-outlet right ventricle (n = 8, 20.0%) and a transposition of the great arteries (n = 6, 15.0%). Morphologically, the systemic ventricle was the right ventricle in 21 patients (52.5%). The Fontan type included an extracardiac conduit in 24 patients (60.0%), a lateral tunnel in 15 patients (37.5%), and an atriopulmonary connection in 1 patient (2.5%). Regarding medical therapy, antiplatelet agents were prescribed in approximately 70% of patients, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in 50%, diuretics in 40%, and β-blockers in 30% (Table 1).

3.2 Assessment of Data Distribution

Shapiro-Wilk tests revealed that several key variables, including RDW (W = 0.77, p < 0.001), CVP (W = 0.93, p = 0.02), and BNP (W = 0.71, p < 0.001), significantly deviated from normal distribution, supporting the use of Spearman’s rank correlation for analyses.

Table 1: Clinical characteristics between the elevated and normal RDW groups.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 40) | RDW ≤ 14.5% (n = 30) | RDW > 14.5% (n = 10) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age at study entry, month (IQR) | 22.0 (18.0–29.3) | 21.5 (18.0–29.0) | 25.5 (20.3–29.8) | 0.43 |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (65.0) | 23 (76.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.02* |

| Age at Fontan procedure, year (IQR) | 2.5 (1.0–5.5) | 2.0 (1.0–8.5) | 3.0 (1.3–5.0) | 0.86 |

| Duration after Fontan procedure, year (IQR) | 19.5 (16.0–23.3) | 19.0 (16.0–21.8) | 20.5 (16.8–24.0) | 0.36 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 19.8 (18.1–23.0) | 19.7 (18.0–22.9) | 21.0 (18.2–24.9) | 0.48 |

| BSA, m2 (IQR) | 1.56 (1.42–1.7) | 1.56 (1.50–1.71) | 1.57 (1.41–1.61) | 0.63 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Single right ventricle, n (%) | 10 (25.0) | 9 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0.40 |

| Double-outlet right ventricle, n (%) | 8 (20.0) | 7 (23.3) | 1 (10.0) | 0.65 |

| TGA, n (%) | 6 (15.0) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (10.0) | >0.99 |

| Tricuspid atresia, n (%) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.56 |

| Single left ventricle, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.56 |

| PAIVS, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.01* |

| ccTGA, n (%) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (10.0) | 0.44 |

| Others, n (%) | 4 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (30.0) | - |

| Morphology of systemic right ventricle, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 18 (60.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.15 |

| APC/LT/ECC, n (%) | 1 (2.5)/15 (37.5)/24 (60.0) | 1 (3.3)/10 (33.3)/19 (63.3) | 0 (0.0)/5 (50.0)/5 (50.0) | 0.60 |

| Fenestration, n (%) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.15 |

| Medication use | ||||

| Diuretics, n (%) | 17 (42.5) | 10 (33.3) | 7 (70.0) | 0.07 |

| β-adrenergic blocker, n (%) | 10 (25.0) | 8 (26.7) | 2 (20.0) | >0.99 |

| Systemic vasodilator, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 15 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 0.72 |

| Pulmonary vasodilator, n (%) | 9 (22.5) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.67 |

| Antiarrhythmic agent, n (%) | 10 (25.0) | 8 (26.7) | 2 (20.0) | 0.32 |

| Antiplatelet agent, n (%) | 29 (72.5) | 23 (76.7) | 6 (60.0) | 0.42 |

| Anticoagulant agent, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (16.7) | 2 (20.0) | >0.99 |

3.3 Laboratory and Hemodynamic Findings

The median laboratory values were as follows: RDW 13.3% (12.7–14.4) and hemoglobin and BNP levels of 15.5 (13.5–16.6) g/dL and 21.5 (10.6–35.2) pg/mL, respectively. Hemodynamic parameters showed a median CVP of 11.0 (9.0–13.3) mmHg, ScvO2 of 73.1 (69.5–78.6)%, SaO2 of 94.6 (92.3–96.1)%, CI of 4.4 (3.0–5.3) L/min/m2, and PVRi of 1.15 (0.78–1.50) Wood Units-m2 (Table 2).

Table 2: Laboratory and hemodynamic findings.

| Total (n = 40) | RDW ≤ 14.5% (n = 30) | RDW > 14.5% (n = 10) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory parameters (IQR) | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 15.5 (13.5–16.6) | 15.9 (15.0–16.8) | 13.2 (12.6–13.6) | 0.004* |

| MCV, fL | 90.8 (87.0–93.7) | 92.4 (89.3–94.0) | 85.5 (81.0–87.5) | 0.002* |

| RDW, % | 13.3 (12.7–14.4) | - | - | |

| White blood cell, μL | 4650 (3775–5225) | 4900 (4200–5800) | 3300 (2825–3925) | <0.001* |

| Lymphocytes, /μL | 1126 (855–1305) | 1153 (991–1454) | 803 (645–1137) | 0.04* |

| Platelet, ×103/μL | 146 (102–177) | 156 (109–178) | 103 (72–126) | 0.053 |

| AST, U/L | 23.5 (20.8–28.8) | 25.0 (22.0–30.3) | 23.0 (20.3–26.0) | 0.61 |

| ALT, U/L | 21.5 (17.0–29.3) | 23.5 (19.3–30.0) | 17.5 (13.3–19.8) | 0.02* |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.5 (4.3–4.8) | 4.6 (4.4–4.9) | 4.3 (4.3–4.4) | 0.01* |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.70 (0.62–0.77) | 0.70 (0.62–0.74) | 0.72 (0.60–0.91) | 0.60 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 100.4 (84.1–112.2) | 103.6 (95.0–117.9) | 81.2 (74.6–95.4) | 0.006* |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.04 (0.04–0.08) | 0.04 (0.04–0.06) | 0.08 (0.04–0.12) | 0.11 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 21.5 (10.6–35.2) | 17.9 (9.8–27.0) | 34.4 (22.9–68.7) | 0.03* |

| Cardiac function and hemodynamic parameters (IQR) | ||||

| Cardiothoracic ratio (%) | 42.9 (40.5–46.4) | 42.5 (39.4–46.1) | 43.2 (40.9–46.4) | 0.65 |

| SBP, mmHg | 106.5 (101.8–114.3) | 108 (103.0–114.8) | 104 (96.5–107.5) | 0.27 |

| DBP, mmHg | 65.5 (61.0–71.3) | 66.5 (62.3–71.8) | 64.0 (58.0–70.0) | 0.54 |

| CVP, mmHg | 11.0 (9.0–13.3) | 10.5 (8.0–12.0) | 14.5 (13.3–15.8) | <0.001* |

| mPAP, mmHg | 10.5 (8.8–12) | 9.5 (8.0–11.0) | 13.0 (12.0–14.8) | 0.002* |

| PCWP, mmHg | 8.0 (5.0–10) | 6.5 (5.0–8.0) | 10.0 (9.0–11.0) | 0.005* |

| SaO2, % | 94.6 (92.3–96.1) | 95.6 (93.7–96.4) | 91.3 (87.1–93.4) | 0.003* |

| ScvO2, % | 73.1 (69.5–78.6) | 76.1 (72.8–79.7) | 63.8 (61.1–69.0) | <0.001* |

| PVRi, Wood Unit·m2 | 1.15 (0.78–1.50) | 1.08 (0.66–1.48) | 1.20 (1.09–1.48) | 0.44 |

| SVRi, Wood Unit·m2 | 24.6 (18.7–30.3) | 25.1 (20.2–30.4) | 18.5 (12.0–25.8) | 0.12 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 57.5 (52.0–63.3) | 57.0 (52.3–62.9) | 62.0 (53.3–66.0) | 0.44 |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 4.4 (3.0–5.3) | 4.7 (3.7–5.4) | 2.7 (2.2–3.2) | 0.003* |

3.4 Correlation between RDW and Hemodynamic Parameters

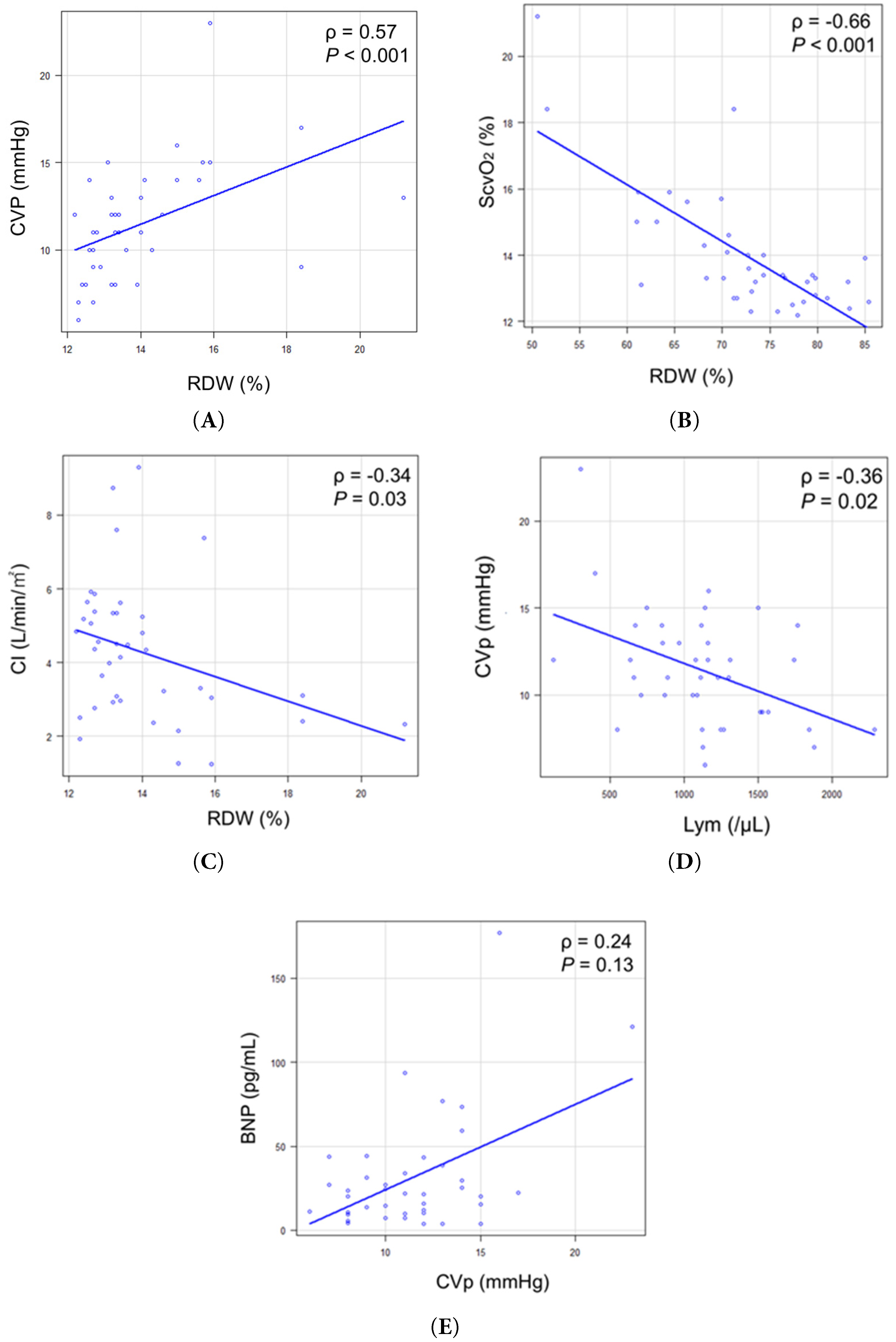

RDW showed significant correlations with multiple hemodynamic parameters. Bootstrap analysis with 10,000 iterations provided robust 95% confidence intervals: RDW correlated positively with CVP (ρ = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.28–0.79, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A) and negatively with ScvO2 (ρ = −0.66, 95% CI: −0.82 to −0.42, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B) and cardiac index (ρ = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.001, p = 0.03) (Fig. 1C). The confidence intervals for RDW-CVP and RDW-ScvO2 correlations did not include zero, confirming statistical significance even with conservative estimation. Additionally, CVP showed a negative correlation with lymphocyte count (ρ = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.62 to −0.04, p = 0.02) (Fig. 1D). No significant correlation was observed between CVP and BNP levels (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1: Correlation between RDW and hemodynamic parameters. (A) Correlation between RDW and CVP. (B) Correlation between RDW and ScvO2. (C) Correlation between RDW and CI. (D) Correlation between CVP and Lym. (E) Correlation between CVP and BNP. BNP = b-type natriuretic peptide; CI = cardiac index; CVP = central venous pressure; Lym = lymphocyte count; RDW = red cell distribution width; ScvO2 = central venous oxygen saturation.

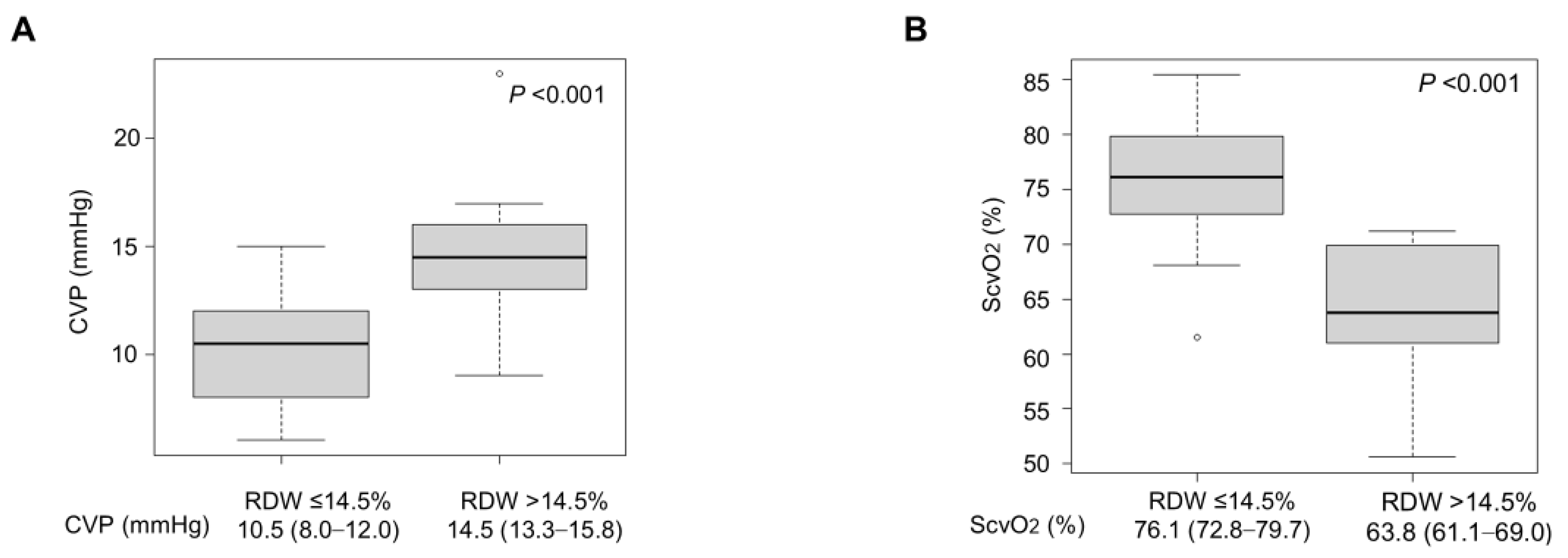

When stratified by RDW (cutoff: 14.5%), the elevated RDW group (n = 10) demonstrated significantly higher CVP compared with the normal RDW group (n = 30) (14.5 [13.3–15.8] vs. 10.5 [8.0–12.0] mmHg; difference 4.0 mmHg (95% CI: 2.3–5.7 mmHg), p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, ScvO2 was significantly lower in the elevated RDW group: median 63.8 [61.1–69.0]% vs. 76.1 [72.8–79.7]%; difference −12.3% (95% CI: −17.8 to −6.8%), p < 0.001 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Comparison of hemodynamic parameters between RDW groups. (A) CVP was significantly higher in the elevated RDW group than in the normal RDW group (difference: 4.0 mmHg, p < 0.001). (B) ScvO2 was significantly lower in the elevated RDW group than in the normal RDW group (difference: −12.3%, p < 0.001). Box plots show median (line), interquartile range (box), and range (whiskers). CVP = central venous pressure; RDW = red cell distribution width; ScvO2 = central venous oxygen saturation.

3.6 Regression Analyses and Effect Sizes

Univariate linear regression demonstrated that RDW significantly predicted both CVP and ScvO2. For CVP, the model yielded R2 = 0.22 (adjusted R2 = 0.2, RSE = 2.96, p < 0.001), with a medium effect size (Cohen’s f2 = 0.28). For ScvO2, the model showed stronger predictive power (R2 = 0.55, adjusted R2 = 0.53, RSE = 5.56, p < 0.001) with a large effect size (Cohen’s f2 = 1.20). Sensitivity analyses excluding outliers (n = 4, identified by IQR method) yielded essentially unchanged correlations (RDW-CVP: ρ = 0.57, Δρ = −0.01; RDW-ScvO2: ρ = −0.56, Δρ = +0.09), confirming the robustness of findings.

3.7 Comparison with Liver Fibrosis Marker

To evaluate RDW relative to established noninvasive markers of organ congestion [31,32], we examined correlations between FIB-4 index and hemodynamic parameters. The median FIB-4 index was 0.95 (IQR: 0.64–1.48). FIB-4 showed a weak-to-moderate positive correlation with CVP (ρ = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.009 to 0.59, p = 0.04), whereas RDW demonstrated a significantly stronger correlation (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001). The correlation between RDW and FIB-4 was weak and not statistically significant (ρ = 0.29, 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.56, p = 0.07), suggesting these markers capture different pathophysiologic aspects.

3.8 Catheterization-Derived Ventricular Function Parameters

The median EF was 57.5% (IQR: 52.0–63.3%). However, 21 patients (52.5%) had right ventricular morphology, limiting EF accuracy. Exploratory analysis showed no significant correlation between EF and hemodynamic parameters: EF vs. CVP (ρ = 0.3, p = 0.06), EF vs. ScvO2 (ρ = −0.18, p = 0.28), or EF vs. cardiac index (ρ = 0.06, p = 0.73). Similarly, RDW did not correlate with EF (ρ = 0.21, p = 0.19).

In multivariable regression analysis with CVP as the dependent variable and sex, hemoglobin, serum albumin, and CRP as covariates, RDW showed a positive regression coefficient (β = 0.55, 95% CI: −0.08 to 1.18) but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08) (Table 3). By contrast, when ScvO2 was the dependent variable, RDW was identified as an independent negative predictor (β = −2.92, 95% CI: −4.22 to −1.62, p < 0.001) (Table 4). This association remained significant after adjustment for sex, hemoglobin, serum albumin, and CRP levels, with an adjusted R2 of 0.55.

Table 3: Multivariable linear regression analysis for central venous pressure.

| Independent Variable | β-Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 2.71 | (−0.05, 5.46) | 0.054 |

| RDW (%) | 0.55 | (−0.08, 1.18) | 0.08 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.72 | (−1.52, 0.08) | 0.08 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | −2.80 | (−6.04, 0.43) | 0.09 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | −0.37 | (−17.66, 16.92) | 0.97 |

Table 4: Multivariable linear regression analysis for mixed venous oxygen saturation.

| Independent Variable | β-Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 0.10 | (−5.58, 5.78) | 0.97 |

| RDW (%) | −2.92 | (−4.22, −1.62) | <0.001* |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.42 | (−1.23, 2.08) | 0.61 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.67 | (−6.01, 7.34) | 0.84 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | −1.25 | (−36.91, 34.42) | 0.94 |

In this study of adolescent and adult patients who underwent the Fontan procedure, RDW demonstrated a moderate positive correlation with CVP, a moderate to strong negative correlation with ScvO2, and a moderate correlation with CI, supporting its potential role as a noninvasive hemodynamic marker. Importantly, RDW was identified as an independent predictor of ScvO2. These findings suggest that increased RDW is not merely a reflection of anemia or inflammation but rather a sensitive indicator of the unique pathophysiology of Fontan circulation, particularly tissue-level oxygenation abnormalities. Although the correlation between RDW and CVP was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis (p = 0.08), the positive regression coefficient (0.55) and wide confidence interval suggest that significance may emerge in larger cohorts.

Our results differ from those reported by Kojima et al. who reported a direct correlation between RDW and CVP in pediatric Fontan patients [16]. In our adult cohort (median age: 22 years, median: 19.5 years post-Fontan), RDW remained correlated with CVP in univariable analysis but lost significance after adjustment, whereas its association with ScvO2 remained robust. This divergence likely reflects longitudinal pathophysiological evolution. In early childhood, fluctuations in CVP directly affect systemic hemodynamics and may be mirrored by RDW. In adulthood, however, chronic hemodynamic stress drives ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary vascular remodeling, neurohormonal activation, and progression from a “good Fontan” to a “failing Fontan.” As chronic disease advances, CVP becomes influenced by multiple confounders—diastolic dysfunction, arrhythmias, and atrioventricular valve regurgitation—reducing its direct relationship with RDW. ScvO2, in contrast, integrates global circulatory adequacy and may detect impaired oxygen utilization earlier than rising CVP.

The clinical relevance of these findings is supported by our subgroup analysis. Patients with elevated RDW (>14.5%) had significantly higher CVP (median 14.5 vs. 10.5 mmHg, p < 0.001) and lower ScvO2 and CI compared to those with normal RDW. The 4.0 mmHg difference in CVP is clinically relevant, particularly in light of the hemodynamic criteria for identifying a risk range for Fontan failure, which consider CVP ≥15 mmHg as pathological [26,27,28]. Previous studies have further indicated that even modest increases in CVP are associated with significant reductions in peak VO2 (peak oxygen uptake) [33], and that even minor elevations of only a few mmHg in CVP may precipitate complications such as hepatic dysfunction and protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) [5]. Our comparative analysis demonstrated that RDW exhibited substantially stronger correlation with CVP (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001) than FIB-4 index (ρ = 0.33, p = 0.04). The weak correlation between RDW and FIB-4 (ρ = 0.29, p = 0.07) further indicates that these biomarkers reflect distinct physiological processes. Whereas FIB-4 reflects hepatic congestion, RDW appears to integrate broader systemic derangements, including impaired erythropoiesis, cytokine-mediated suppression of red cell maturation, and oxidative stress from chronic hypoxemia. The stronger correlation between RDW and ScvO2 than between RDW and CVP may reflect RDW’s sensitivity to tissue-level oxygen delivery rather than pressure alone, suggesting that RDW captures the cumulative impact of chronic circulatory stress on erythropoiesis. This sensitivity may allow RDW to identify early circulatory deterioration before overt hemodynamic decompensation, offering a potential window for timely intervention.

Several mechanisms likely contribute to RDW elevation in the Fontan population. Chronically low cardiac output may suppress erythropoietin production, while venous congestion may activate inflammatory pathways such as IL-6 signaling, inhibiting erythroid maturation [34,35,36,37]. Chronic mild hypoxemia and impaired iron utilization may further increase erythrocyte heterogeneity [35,38]. These factors may interact to generate a Fontan-specific pattern of RDW elevation that becomes more pronounced during the chronic phase.

From a clinical standpoint, RDW may serve as a practical biomarker for noninvasive assessment. Unlike invasive catheterization, RDW can be measured routinely at a low cost, allowing noninvasive monitoring of circulatory status during outpatient follow-up. Notably, our study minimized temporal bias by evaluating RDW and hemodynamic parameters during the same hospitalization. Because RDW is universally available at no additional cost, serial monitoring during outpatient follow-up may help detect subclinical circulatory deterioration and identify patients who may benefit from earlier catheterization or intensified surveillance. While RDW cannot replace comprehensive hemodynamic evaluation, it may serve as a meaningful screening tool to optimize the timing of invasive assessment.

The 14.5% cutoff corresponds to the established upper limit of normal for RDW in the general adult population [39,40] and has been consistently used in prior Fontan studies, including Kramer et al. and Buendía Fuentes et al. [11,25], both demonstrating associations with adverse outcomes. In our cohort, this threshold effectively discriminated hemodynamic abnormalities, with the elevated RDW group showing substantially higher CVP (14.5 vs. 10.5 mmHg, p < 0.001) and lower ScvO2 (63.8% vs. 76.1%, p < 0.001), with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.66 and 2.15). These findings support the clinical validity of 14.5% in adult Fontan patients. We acknowledge that Fontan-specific RDW reference ranges have not been established, and the optimal threshold may differ due to unique physiologic features such as chronic mild hypoxemia and altered erythropoiesis. While our results suggest 14.5% is appropriate for initial screening, future studies with larger cohorts and long-term outcome data are needed to determine whether population-specific standards would enhance risk stratification.

This study has limitations. It was conducted retrospectively at a single center with a limited sample size, which may reduce statistical power and external validity. Although we performed normality testing, sensitivity analyses, bootstrap confidence intervals, and calculated Cohen’s f2, the cohort size still constrains the strength of conclusions. Residual confounders affecting erythropoiesis cannot be excluded. Although we compared RDW with the FIB-4 index, more comprehensive echocardiographic measures such as strain imaging were not systematically obtained. However, echocardiographic EF assessment is inherently limited, particularly in patients with a dominant right ventricle, due to its anatomical characteristics. While alternative echocardiographic indices such as fractional area change (FAC) and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) may provide additional information, these parameters were not routinely measured under our institutional protocol during the study period. Future studies should evaluate longitudinal RDW changes in relation to clinical deterioration and incorporate multimodality imaging—including echocardiography and liver elastography—to refine risk stratification.

In adolescents and adults with Fontan circulation, RDW is associated with hemodynamic abnormalities, particularly elevated CVP and reduced ScvO2, and is independently predictive of ScvO2. These findings indicate that RDW reflects tissue-level circulatory dysfunction and may serve as a sensitive, low-cost, and noninvasive biomarker in this growing patient population. Incorporating RDW into routine follow-ups may facilitate the early detection of Fontan failure and guide timely interventions, complementing invasive assessments when needed.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Kentaro Kogawa; methodology, Kentaro Kogawa, Daishi Hirano, and Reiji Ito; validation, Kentaro Kogawa, Yuka Okawa, Emi Kittaka, Shunsuke Baba, Daishi Hirano, and Reiji Ito; formal analysis, Kentaro Kogawa, Daishi Hirano, and Reiji Ito; investigation, Kentaro Kogawa, Yuka Okawa, Emi Kittaka, Shunsuke Baba, and Reiji Ito; data curation, Kentaro Kogawa; writing-original draft preparation, Kentaro Kogawa; writing-review and editing, Kentaro Kogawa, Daishi Hirano, and Reiji Ito; visualization, Kentaro Kogawa; supervision, Daishi Hirano and Reiji Ito; project administration, Kentaro Kogawa. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Kentaro Kogawa, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan) [41] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jikei University Hospital (approval number: 37-232[12875]). Given the retrospective design, the requirement for written informed consent was waived, and patient notifications were provided via an opt-out process.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests to report regarding the present study.

Glossary

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptides |

| CBC | Complete blood counts |

| CI | Cardiac index |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CVP | Central venous pressure |

| PVRi | Pulmonary vascular resistance index |

| RDW | Red blood cell distribution width |

| SaO2 | Arterial oxygen saturation |

| ScvO2 | Central venous oxygen saturation |

References

1. Fontan F , Baudet E . Surgical repair of tricuspid atresia. Thorax. 1971; 26( 3): 240– 8. doi:10.1136/thx.26.3.240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. d’Udekem Y , Iyengar AJ , Galati JC , Forsdick V , Weintraub RG , Wheaton GR , et al. Redefining expectations of long-term survival after the Fontan procedure: twenty-five years of follow-up from the entire population of Australia and New Zealand. Circulation. 2014; 130( 11 Suppl. 1): S32– 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kverneland LS , Kramer P , Ovroutski S . Five decades of the Fontan operation: a systematic review of international reports on outcomes after univentricular palliation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018; 13( 2): 181– 93. doi:10.1111/chd.12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pundi KN , Johnson JN , Dearani JA , Pundi KN , Li Z , Hinck CA , et al. 40-Year follow-up after the Fontan operation: long-term outcomes of 1,052 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 66( 15): 1700– 10. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rychik J , Atz AM , Celermajer DS , Deal BJ , Gatzoulis MA , Gewillig MH , et al. Evaluation and management of the child and adult with Fontan circulation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019; 140( 6): e234– 84. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khairy P , Fernandes SM , Mayer JE Jr , Triedman JK , Walsh EP , Lock JE , et al. Long-term survival, modes of death, and predictors of mortality in patients with Fontan surgery. Circulation. 2008; 117( 1): 85– 92. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Downing TE , Allen KY , Glatz AC , Rogers LS , Ravishankar C , Rychik J , et al. Long-term survival after the Fontan operation: twenty years of experience at a single center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017; 154( 1): 243– 53.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.01.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mazza GA , Gribaudo E , Agnoletti G . The pathophysiology and complications of Fontan circulation. Acta Biomed. 2021; 92( 5): e2021260. [Google Scholar]

9. Vecoli C , Ait-Alì L , Storti S , Foffa I . Circulating biomarkers in failing Fontan circulation: current evidence and future directions. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2025; 12( 9): 358. doi:10.3390/jcdd12090358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Inai K . Biomarkers for heart failure and prognostic prediction in patients with Fontan circulation. Pediatr Int. 2022; 64( 1): e14983. doi:10.1111/ped.14983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kramer P , Schleiger A , Schafstedde M , Danne F , Nordmeyer J , Berger F , et al. A multimodal score accurately classifies Fontan failure and late mortality in adult Fontan patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 9: 767503. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.767503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Plappert L , Edwards S , Senatore A , De Martini A . The epidemiology of persons living with Fontan in 2020 and projections for 2030: development of an epidemiology model providing multinational estimates. Adv Ther. 2022; 39( 2): 1004– 15. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-02002-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Schilling C , Dalziel K , Nunn R , Du Plessis K , Shi WY , Celermajer D , et al. The Fontan epidemic: population projections from the Australia and New Zealand Fontan Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 219: 14– 9. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tsuchihashi T , Cho Y , Tokuhara D . Fontan-associated liver disease: the importance of multidisciplinary teamwork in its management. Front Med. 2024; 11: 1354857. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1354857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wittczak A , Mazurek-Kula A , Banach M , Piotrowski G , Bielecka-Dabrowa A . Blood biomarkers as a non-invasive method for the assessment of the state of the Fontan circulation. J Clin Med. 2025; 14( 2): 496. doi:10.3390/jcm14020496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kojima T , Yasuhara J , Kumamoto T , Shimizu H , Yoshiba S , Kobayashi T , et al. Usefulness of the red blood cell distribution width to predict heart failure in patients with a Fontan circulation. Am J Cardiol. 2015; 116( 6): 965– 8. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.06.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Koch AME , Zink S , Singer H , Dittrich S . B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with functionally univentricular hearts after total cavopulmonary connection. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008; 10( 1): 60– 2. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nguyen VP , Li S , Dolgner SJ , Steinberg ZL , Buber J . Utility of biomarkers in adult Fontan patients with decompensated heart failure. Cardiol Young. 2020; 30( 7): 955– 61. doi:10.1017/S1047951120001250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Felker GM , Allen LA , Pocock SJ , Shaw LK , McMurray JJV , Pfeffer MA , et al. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50( 1): 40– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dabbah S , Hammerman H , Markiewicz W , Aronson D . Relation between red cell distribution width and clinical outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010; 105( 3): 312– 7. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hampole CV , Mehrotra AK , Thenappan T , Gomberg-Maitland M , Shah SJ . Usefulness of red cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104( 6): 868– 72. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pierce CN , Larson DF . Inflammatory cytokine inhibition of erythropoiesis in patients implanted with a mechanical circulatory assist device. Perfusion. 2005; 20( 2): 83– 90. doi:10.1191/0267659105pf793oa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lippi G , Plebani M . Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and human pathology. one size fits all. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014; 52( 9): 1247– 9. doi:10.1515/cclm-2014-0585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. García-Escobar A , Lázaro-García R , Goicolea-Ruigómez J , Pizarro G , Jurado-Román A , Moreno R , et al. Red blood cell distribution width as a biomarker of red cell dysfunction associated with inflammation and macrophage iron retention: a prognostic marker in heart failure and a potential predictor for iron replacement responsiveness. Card Fail Rev. 2024; 10: e17. doi:10.15420/cfr.2024.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Buendía Fuentes F , Jover Pastor P , Arnau Vives MA , Lozano Edo S , Rodríguez Serrano M , Aguero J , et al. CA125: a new biomarker in patients with Fontan circulation. Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed. 2023; 76( 2): 112– 20. doi:10.1016/j.recesp.2022.05.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Miranda WR , Borlaug BA , Hagler DJ , Connolly HM , Egbe AC . Haemodynamic profiles in adult Fontan patients: associated haemodynamics and prognosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019; 21( 6): 803– 9. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Miranda WR , Hagler DJ , Connolly HM , Kamath PS , Egbe AC . Invasive hemodynamics in asymptomatic adult Fontan patients and according to different clinical phenotypes. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022; 34( 5): E374– 9. doi:10.25270/jic/21.00188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Belahnech Y , Martí Aguasca G , Dos Subirà L . Advances in diagnostic and interventional catheterization in adults with Fontan circulation. J Clin Med. 2024; 13( 16): 4633. doi:10.3390/jcm13164633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Haukoos JS , Lewis RJ . Advanced statistics: bootstrapping confidence intervals for statistics with “difficult” distributions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005; 12( 4): 360– 5. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2005.tb01958.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kanda Y . Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013; 48: 452– 8. doi:10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Heering G , Lebovics N , Agarwal R , Frishman WH , Lebovics E . Fontan-associated liver disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2024. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fuji T , Otoyama Y , Sakaki M , Nomura E , Sugiura I , Nakajima Y , et al. Combined assessment findings of high spleen index and fibrosis-4 index correlate with fibrosis progression in Fontan-associated liver disease: a retrospective study. Cureus. 2025; 17( 11): e97976. doi:10.7759/cureus.97976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Egbe AC , Ali AE , Miranda WR , Connolly HM , Borlaug BA . Aerobic capacity of adults with Fontan palliation: disease-specific reference values and relationship to outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2025; 18( 2): e011981. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.124.011981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tang YD , Katz SD . Anemia in chronic heart failure: prevalence, etiology, clinical correlates, and treatment options. Circulation. 2006; 113( 20): 2454– 61. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Weiss G , Goodnough LT . Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352( 10): 1011– 23. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Van der Putten K , Braam B , Jie KE , Gaillard CAJM . Mechanisms of disease: erythropoietin resistance in patients with both heart and kidney failure. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008; 4( 1): 47– 57. doi:10.1038/ncpneph0655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Weiss G , Ganz T , Goodnough LT . Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019; 133( 1): 40– 50. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-06-856500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zalawadiya SK , Veeranna V , Niraj A , Pradhan J , Afonso L . Red cell distribution width and risk of coronary heart disease events. Am J Cardiol. 2010; 106( 7): 988– 93. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bessman JD , Gilmer PR Jr , Gardner FH . Improved classification of anemias by MCV and RDW. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983; 80( 3): 322– 6. doi:10.1093/ajcp/80.3.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Salvagno GL , Sanchis-Gomar F , Picanza A , Lippi G . Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015; 52( 2): 86– 105. doi:10.3109/10408363.2014.992064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Eba J , Nakamura K . Overview of the ethical guidelines for medical and biological research involving human subjects in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022; 52( 6): 539– 44. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyac034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools