Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Familial Uhl’s Anomaly: A Congenital Heart Disease Case Report

1 Heart Center, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing, 100045, China

2 Department of Medical Genetics and Developmental Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 100069, China

3 Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, 310052, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xin Zhang. Email: ; Xiaofeng Li. Email:

# Yufei Xie and Jing Wang contributed equally to this study

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 737-742. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.073905

Received 28 September 2025; Accepted 23 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Uhl’s anomaly is an exceedingly rare (fewer than 1 in 1,000,000 live births) and often fatal congenital heart disease characterized by the near-complete absence of the right ventricular (RV) myocardium. Although typically considered sporadic, we report a familial case suggesting an inherited etiology. A 12-year-old boy presented with exertional chest pain and a decade-long history of an abnormal cardiac silhouette. Comprehensive imaging revealed apical RV wall thinning, aneurysmal bulging with trabeculations, and severely impaired RV function, with a Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) of 10 mm and a Fractional Area Change (FAC) of 35%. These findings are consistent with a Uhl-like phenotype. Family screening identified similar, though less severe, RV structural anomalies in the patient’s father and sister, supporting an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a rare heterozygous TTN variant (NM_003319:exon154:c.C56156T:p.T18719M) that co-segregated with the disease phenotype. The proband was treated with medical therapy targeting heart failure and remained clinically stable at discharge. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of familial Uhl’s anomaly associated with a TTN gene mutation. These findings support a possible genetic basis for Uhl’s anomaly and highlight the importance of genetic screening in patients with familial cardiac structural abnormalities.Keywords

Supplementary Material

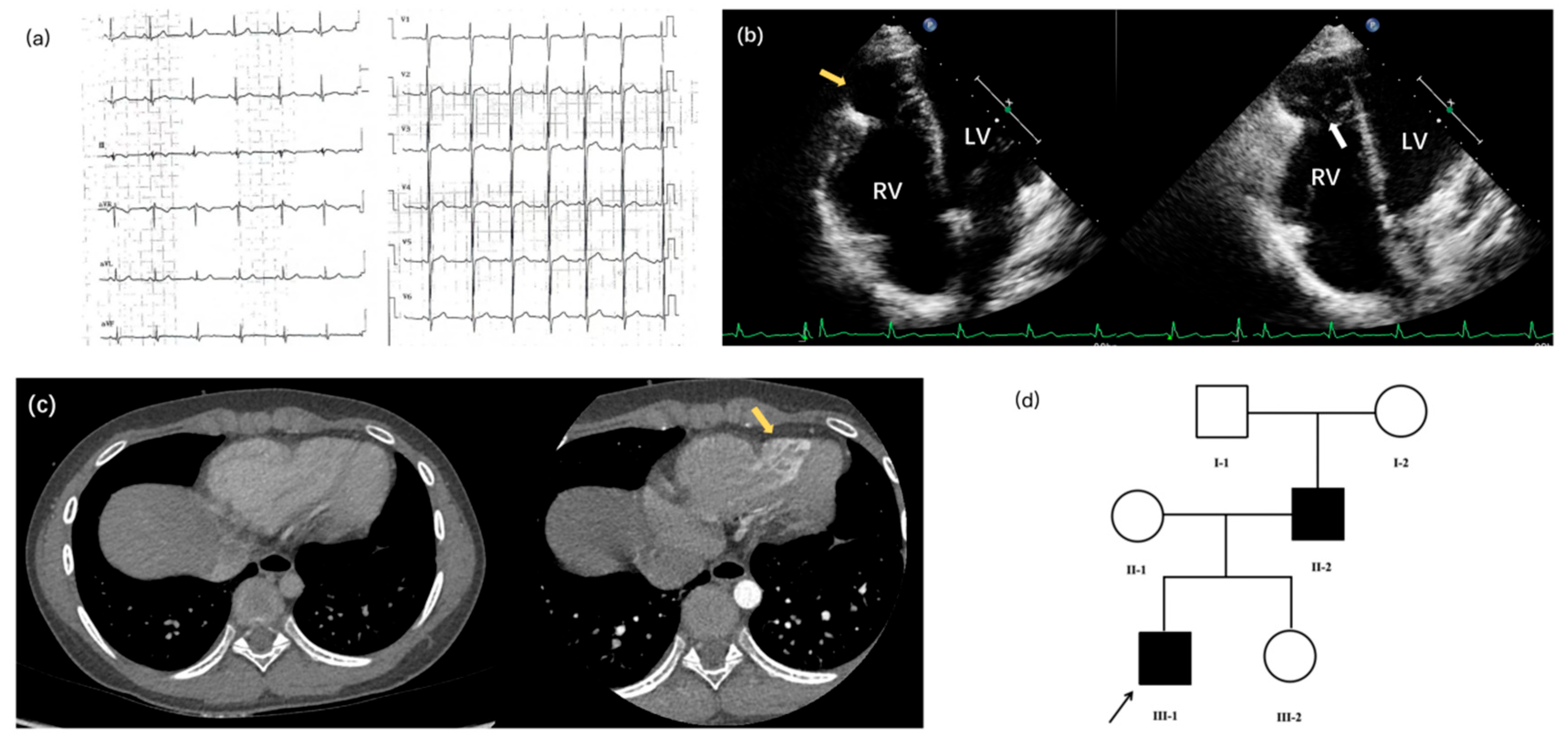

Supplementary Material FileA 12-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with a ten-year history of a congenital cardiac structural abnormality first identified in infancy, and a recent one-month history of exertional chest pain. At age two, he had been hospitalized for pneumonia at a local facility, where a posteroanterior chest radiograph incidentally revealed abnormal cardiac morphology. No follow-up investigations were pursued at that time. Recently, the patient returned to the same facility due to new-onset exertional chest pain and fatigue. Echocardiography performed during this visit revealed outward bulging of the apical segment of the right ventricular (RV) wall. However, no definitive diagnosis was established, and medical management was not initiated. He was subsequently referred to our center for further evaluation. A comprehensive diagnostic workup was performed, including electrocardiography, coronary artery-enhanced computed tomography (CT), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and repeat echocardiography. Electrocardiography demonstrated sinus arrhythmia (Fig. 1a), with a maximum heart rate of 94 beats per minute and a minimum of 77 beats per minute.

Echocardiography and contrast-enhanced CT revealed prominent outward bulging of the apical RV free wall, accompanied by marked myocardial thinning resembling replacement by fibroelastic tissue. Notably, prominent trabeculations were observed within the aneurysmal regions (Fig. 1b,c). Coronary CT angiography additionally showed a thinner right coronary artery and its branches. The RV appeared dilated and hypokinetic on echocardiography, reflecting significant functional impairment. The Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) was measured at 10.0 mm, and the Fractional Area Change (FAC) was 35%, both consistent with severely reduced RV systolic function. Color Doppler flow imaging demonstrated mild tricuspid regurgitation. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with Uhl’s anomaly, which was first described by Dr. Henry Uhl in 1952, defined by the complete absence of myocardium in the RV free wall [1].

Figure 1: Clinical features of the proband and genetic background of the family with familial Uhl’s anomaly. (a) Electrocardiogram demonstrating sinus arrhythmia in the proband, characterized by irregular P-P intervals; (b) Echocardiographic four-chamber view of the proband revealing apical right ventricular (RV) free wall bulging and thinning (yellow arrow), with near-complete congenital absence of myocardium replaced by fibroelastic tissue. Note the prominent trabeculations in the aneurysmal area (white arrow); (c) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the proband corroborating the apical RV wall bulge and extensive trabeculation (arrow); (d) Pedigree showing an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. The arrow indicates the proband (III-1). The heterozygous TTN variant co-segregates with all affected family members.

The patient was initiated on a comprehensive medical regimen during hospitalization. Sodium creatine phosphate was administered to provide myocardial metabolic support. Aspirin was prescribed for anticoagulation to reduce the risk of thrombus formation associated with right ventricular dysfunction. Captopril was introduced to inhibit maladaptive ventricular remodeling, while metoprolol was used to decrease myocardial oxygen demand and enhance coronary perfusion. After eight days of therapy, the patient was asymptomatic.

Following discharge, the patient has been under close outpatient follow-up for nearly two years. Serial clinical and imaging assessments have demonstrated sustained stability in his cardiac condition. Right ventricular geometry and systolic function have remained unchanged, with no evidence of disease progression or functional deterioration. In light of this stable clinical course, the current medical regimen has been continued without modification. Ongoing long-term follow-up and functional monitoring remain essential for elucidating the natural history and therapeutic response in this rare congenital heart disease.

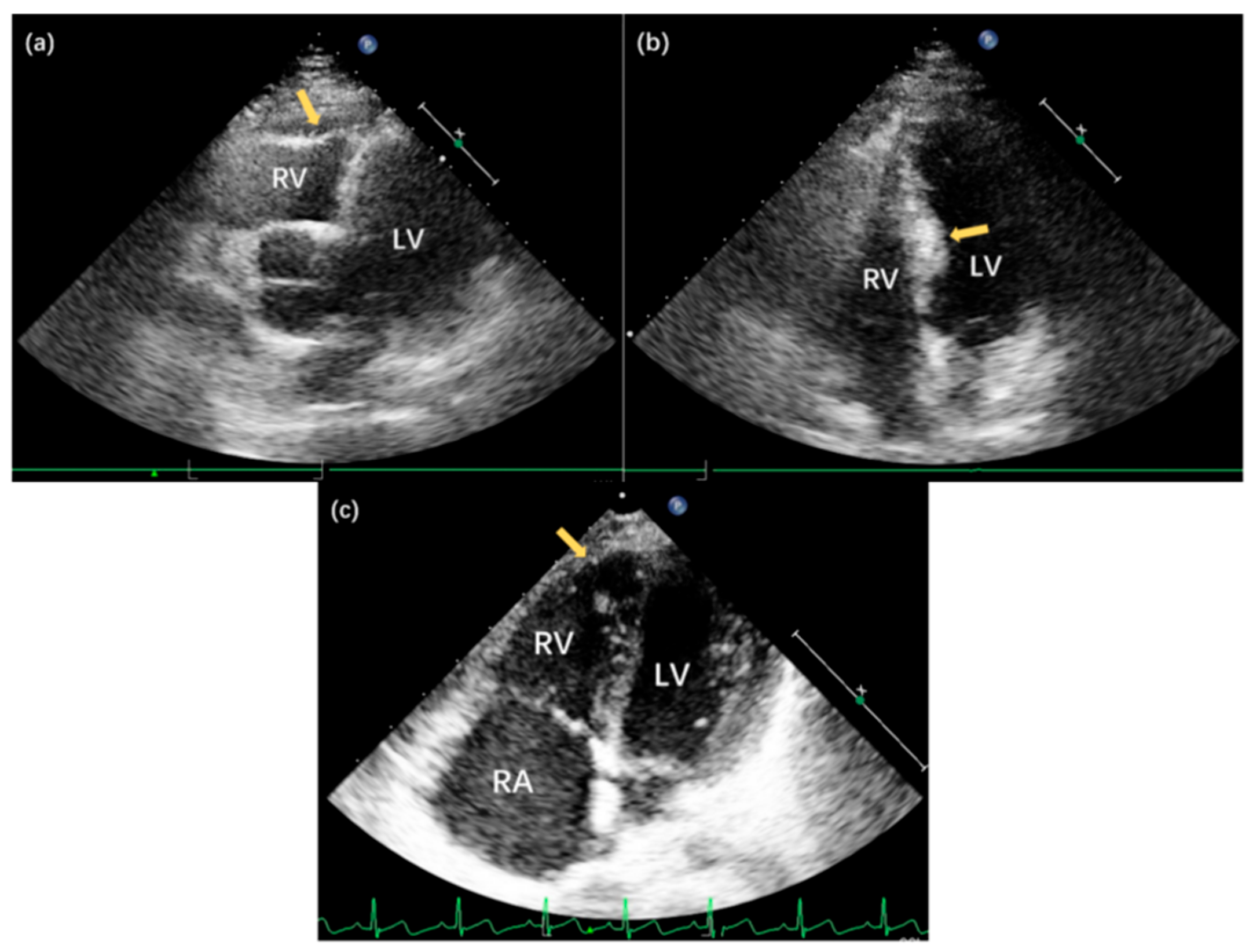

Given the suspected genetic basis of the proband’s cardiac structural abnormalities, all four family members underwent transthoracic echocardiography. The proband’s mother demonstrated no cardiac abnormalities. In contrast, the father and sister exhibited right ventricular structural changes similar to those observed in the proband, although with milder phenotypic expression (Table 1, Fig. 1d and Fig. 2). These findings supported the possibility of a familial form of the disease.

Figure 2: Echocardiographic findings in family members with familial Uhl’s anomaly. (a) Apical five-chamber view of II-2, demonstrating pronounced thinning of the right ventricular (RV) apical wall (arrow) with slight bulging; (b) Apical four-chamber view of II-2, revealing asymmetric septal hypertrophy with a maximal thickness of 13.0 mm in the mid-septal region (arrow); (c) Apical four-chamber view of III-2, showing significant thinning of the RV apical wall (arrow) without substantial bulging, demonstrating the variable expressivity of the congenital anomaly among affected family members.

Table 1: Positive echocardiography findings in each family member.

| Member Code | Positive Echocardiography Findings |

|---|---|

| II-2 | Echocardiography revealed thinning of the right ventricular (RV) apical wall with a slight outward bulge. Additionally, the mid-septal region showed localized thickening, measuring 13.0 mm (Fig. 2a,b). |

| III-1, proband | Echocardiography showed outward bulging of the apical region of the RV free wall, accompanied by myocardial thinning suggestive of fibroelastic tissue replacement. Prominent trabeculations were observed within the bulging areas. The RV was also dilated with globally hypokinetic walls. The TAPSE measured 10.0 mm, and the FAC was 35%, both indicative of significantly reduced RV systolic function. Color Doppler flow mapping revealed mild tricuspid regurgitation. |

| III-2 | Echocardiography revealed thinning of the RV apical wall (Fig. 2c) |

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed for four family members (II-1, II-2, III-1, III-2) using the Illumina HiSeq XTEN platform and the Agilent SureSelect V6 capture kit. Bioinformatic processing, including alignment to the hg38 reference genome (BWA v0.5.1) and variant calling (SAMtools/Picard), prioritized rare protein-altering variants predicted to be deleterious by PolyPhen, SIFT, and MutationTaster. Candidate variants were further filtered using a curated cardiovascular gene panel comprising 181 genes (Supplementary Table S1) and by assessing inheritance consistency within the pedigree. Five variants initially met these criteria, but only one was retained after excluding variants that did not segregate with the phenotype.

A heterozygous TTN variant (NM_003319:exon154:c.C56156T:p.T18719M) was the only variant that co-segregated with disease status. This variant was present in the proband (III-1) and both affected relatives (II-2, III-2), but absent in the unaffected mother (II-1). No co-segregated variants were identified in CCDC78, COL6A3, COL9A3, or MEGF10 (Table 2).

Table 2: Genetic sequencing results in each family member.

| CCDC78 (NM_001031737:exon1:c.A58C:p.N20H) | COL6A3 (NM_057166:exon17:c.A4568C:p.K1523T) | COL9A3 (NM_001853:exon4:c.C245T:p.P82L) | MEGF10 (NM_032446:exon19:c.2362+1->T) | TTN (NM_003319:exon154:c.C56156T:p.T18719M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II-1 | AC | AC | CT | No insertion | CC |

| II-2 | AA | AA | CC | Insertion (T) | CT |

| III-1 | AC | AC | CT | Insertion (T) | CT |

| III-2 | AA | AA | CC | No insertion | CT |

The clinical spectrum of Uhl’s anomaly is broad, with severe forms often diagnosed prenatally or during infancy and associated with poor prognosis [2]. However, a growing body of literature has documented survival into adulthood, where patients typically present with refractory right heart failure and life-threatening arrhythmias [3,4]. Therapeutic strategies vary based on age and disease severity, ranging from surgical palliation in pediatric patients [5] to advanced heart failure therapies in adults, including cardiac transplantation [3,6,7]. In rare cases with multiorgan involvement, combined heart-liver transplantation has also been reported [8]. Although Uhl’s anomaly predominantly affects the RV, phenotypic expression to the left ventricle has been described, including associations with left ventricular noncompaction [9]. Despite its serious clinical course and high mortality, the genetic basis of Uhl’s anomaly remains poorly understood. Most reports in the literature are descriptive and focus on clinical phenotypes rather than genetic mechanisms. One notable exception is a case linking thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia (TRMA) and an Uhl’s-like phenotype to a pathogenic variant in the SLC19A2 gene [10]. In our study, no pathogenic SLC19A2 variants were detected among family members, suggesting a distinct underlying genetic cause.

The TTN gene, which encodes the giant sarcomeric protein titin has emerged as a major contributor to inherited cardiomyopathies and congenital heart defects [11,12,13,14]. Biallelic truncating variants in TTN are known to cause severe, early-onset dilated cardiomyopathy and congenital structural abnormalities in children [15]. Furthermore, TTN has been implicated in congenital malformations such as atrioventricular septal defects [16] and functional deterioration in conditions such as bicuspid aortic valve [17]. In this study, we identified a rare heterozygous TTN variant (NM_003319:exon154:c.C56156T:p.T18719M) with an allele frequency of 1.36 × 10−5 in the gnomAD v4.1.0 database. This was the only variant that co-segregated with the disease phenotype across three affected family members, providing PP1 level evidence and classifying it as a VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance) under ACMG criteria. The variant is located in a region of titin associated with Z-disk anchoring, a structural domain essential for sarcomere stability. While Z-disk–related titin mutations have been implicated in dilated cardiomyopathy, their involvement in congenital RV malformations has not been systematically described [18,19]. These findings raise the possibility of a broader genotype-phenotype continuum within titin-associated disorders that may span both congenital and acquired RV dysfunction.

Nevertheless, this study has inherent limitations. It is based on a single pedigree, which limits its generalizability. Although the identified TTN variant co-segregates with the disease, definitive pathogenicity cannot be established without additional independent families or functional analyses.

In conclusion, this study reports the first familial case of Uhl’s anomaly associated with a TTN gene mutation, providing preliminary evidence for a genetic etiology, inheritance mode and variable expressivity. This finding challenges the traditional view of Uhl’s anomaly as a sporadic condition and underscores the importance of genetic screening in patients with familial cardiac structural abnormalities. Transthoracic echocardiography remains a key diagnostic modality for early identification and functional assessment.

Our results also suggest a broader genotype-phenotype continuum within titin-associated disorders. Future studies employing in vitro or in vivo models will be essential to clarify the mechanistic impact of this variant on myocardial development and structural integrity.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation Haidian Joint Fund (L222079), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470313).

Author Contributions: Yufei Xie and Jing Wang contributed equally to this work. They drafted the manuscript, prepared figures, collected data, and performed analysis. Qun Wu and Haoxuan Li contributed to data collection and organization. Xiaomin Duan and Fangyun Wang assisted with data analysis and manuscript review. Xin Zhang and Xiaofeng Li supervised the research, reviewed the manuscript, and provided final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and information used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University (2024-301-D). Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.073905/s1.

References

1. Uhl HS . A previously undescribed congenital malformation of the heart: almost total absence of the myocardium of the right ventricle. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1952; 91( 3): 197– 209. [Google Scholar]

2. Vaidyanathan B , Soman S , Karmegaraj B . Utility of the novel fetal heart quantification (fetal HQ) technique in diagnosing ventricular interdependence and biventricular dysfunction in a case of prenatally diagnosed Uhl’s anomaly. Echocardiography. 2024; 41( 7): e15862. doi:10.1111/echo.15862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bacigalupe JJ , Vensentini N , Torroba S , Mariani JA , Defelitto S , Blanco N , et al. Cardiac transplantation as resolution for Uhl’s anomaly: a case report. JHLT Open. 2025; 9: 100343. doi:10.1016/j.jhlto.2025.100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mohamed OAM , El-Dardeery M , Zayed K , Mosaad E , Abdulwahhab MM , Romeih S . Uhl’s Anomaly in Adulthood. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2024; 15( 4): 523– 5. doi:10.1177/21501351241236720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Oka N , Tomoyasu T , Kaneko M , Matsui K . Surgical treatment of a rare case of Uhl anomaly, tricuspid atresia, absent pulmonary valve, hypoplastic right ventricle, and right ventricular coronary artery fistula. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2025; 16( 6): 855– 58. doi:10.1177/21501351251345787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Caruso S , Cannataci C , Romano G . Case 288: Uhl anomaly. Radiology. 2021; 299( 1): 237– 41. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021192475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Toubat O , Han JJ , Predina JD , Goldberg LR , Ibrahim ME . Heart transplantation for Uhl anomaly in an adult. JACC Case Rep. 2024; 29( 10): 102322. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2024.102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Landi F , Sandoval E , Martinez J , Blasi A , Arguis MJ , Colmenero J , et al. Combined heart and liver transplantation for Uhl’s anomaly: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2021; 53( 9): 2751– 3. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2021.08.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mohammad A , Parwani P , Manalo C , Gordon BM , Kheiwa A . Uhl’s anomaly with left ventricular noncompaction: role of multimodality imaging in a rare association. JACC Case Rep. 2021; 3( 12): 1463– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.06.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Beshlawi I , Al Zadjali S , Bashir W , Elshinawy M , Alrawas A , Wali Y . Thiamine responsive megaloblastic anemia: the puzzling phenotype. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014; 61( 3): 528– 31. doi:10.1002/pbc.24849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Çap M , Tatli İ , Comert AD , Polat H , Erdogan E . Familial spontaneous coronary artery dissection involving the left main coronary artery in a young male: a case report. Am J Cardiol. 2025; 256: 34– 7. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2025.07.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Granzier HL , Labeit S . Discovery of titin and its role in heart function and disease. Circ Res. 2025; 136( 1): 135– 57. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.323051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang L , Liu H , Zhao Q , Chen Y , Sun Y , Li R , et al. Identification of the non-canonical splice-disrupting variants of TTN in dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2025; 445: 134044. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2025.134044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang TL , Ting J , Lin MR , Chang WC , Shih CM . Identification of genetic variants associated with severe myocardial bridging through whole-exome sequencing. J Pers Med. 2023; 13( 10): 1509. doi:10.3390/jpm13101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Baban A , Cicenia M , Magliozzi M , Parlapiano G , Cirillo M , Pascolini G , et al. Biallelic truncating variants in children with titinopathy represent a recognizable condition with distinctive muscular and cardiac characteristics: a report on five patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023; 10: 1210378. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1210378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu H , Geng Z , Zhang S , Xu Y , Wang Q , Chen S , et al. Rare copy number variation analysis identifies disease-related variants in atrioventricular septal defect patients. Front Genet. 2023; 14: 1075349. doi:10.3389/fgene.2023.1075349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen S , Jin Q , Hou S , Li M , Zhang Y , Guan L , et al. Identification of recurrent variants implicated in disease in bicuspid aortic valve patients through whole-exome sequencing. Hum Genomics. 2022; 16( 1): 36. doi:10.1186/s40246-022-00405-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Stroeks S , Merlo M , Mora-Ayestaran N , Jason M , Tayal U , Wang P , et al. Sex differences in prognosis of patients with genetic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2025; 18( 11): e012592. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.124.012592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Vikhorev PG , Vikhoreva NN , Yeung W , Li A , Lal S , Dos Remedios CG , et al. Titin-truncating mutations associated with dilated cardiomyopathy alter length-dependent activation and its modulation via phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res. 2022; 118( 1): 241– 53. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools