Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Value of Four-Dimensional Ultrasound in Diagnosing Fetal Congenital Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

1 College of Public Health, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

2 School of Basic Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

3 Institute of Reproductive Health, Henan Academy of Innovations in Medical Science, National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Birth Defects Prevention, Zhengzhou 450000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Li Liu. Email: ; Panpan Sun. Email:

; Zhiguang Ping. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease)

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 717-727. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2026.075611

Received 04 November 2025; Accepted 21 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Background: Four-dimensional (4D) ultrasound is increasingly being used for prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease (CHD). We aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate its diagnostic accuracy for fetal CHD. Methods: This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-DTA guidelines. We systematically searched eight databases for studies published up to July 22, 2025. Data were extracted to calculate diagnostic accuracy metrics, study quality was assessed using QUADAS-2, and a bivariate random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis. Results: A total of 49 studies were included, comprising 45 retrospective and 4 prospective studies, which were mainly (91.8%) conducted in China. These studies involved 23,397 fetuses, among which 2115 were diagnosed with congenital heart disease. The pooled sensitivity of 4D ultrasound for diagnosing fetal congenital heart disease was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.93), the pooled specificity was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.97–0.99), and the area under the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve (AUC) was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99). Although 4D ultrasound technology can be implemented as early as 11 weeks of gestation, its diagnostic sensitivity and specificity reached a superior level and stabilized at an average of 20 weeks of gestation (range 14–28 weeks). Meta-regression indicated that sample size and prior suspicion of fetal CHD were significant contributors to heterogeneity (p < 0.05). Conclusion: Four-dimensional ultrasound has high diagnostic efficacy for fetal CHD and is suitable for prenatal screening of fetal CHD, and the diagnostic effect is optimal and stable at an average gestational age of 20 weeks (range 14–28 weeks).Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCongenital heart disease (CHD), the most prevalent type of birth defect and a primary cause of neonatal mortality, has an incidence of 1%–2% [1]. CHD not only severely impairs fetal development, but also imposes a substantial burden on society, family, and medical care. Therefore, early screening, diagnosis and intervention are particularly important. For CHD, the current clinical screening methods are diverse, such as ultrasound, hemodynamics, and electrocardiography. Among these methods, ultrasonography is highly acceptable and provides the most direct visualization. It has advantages such as reproducibility and non-invasiveness, and plays an important role in the screening of CHD in fetuses, making it the preferred method [2]. Fetal echocardiography and two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound were commonly used to screen for CHD in the past, but their diagnostic efficacy for CHD is still somewhat limited [3]. In the late 1990s, with the upgrading of ultrasound equipment and the improvement of imaging examination levels, four-dimensional (4D) ultrasound, developed from 2D and three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound, began to be used in clinical practice, providing a new method for the diagnosis of fetal heart malformations [4]. Compared with conventional 2D imaging, 4D ultrasound provides superior stereoscopic visualization. Crucially, when combined with Spatio-Temporal Image Correlation (STIC) technology, 4D ultrasound enables the automated acquisition of a full fetal cardiac volume dataset over a single motion cycle [5]. This integration facilitates multi-planar offline analysis and reduces operator dependency, thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional planar imaging in capturing complex dynamic cardiac structures and significantly reducing the risk of missed diagnoses [6,7]. In recent years, although the diagnostic value of prenatal 4D ultrasound for fetal CHD has been widely explored, a comprehensive meta-analysis is lacking to assess its diagnostic accuracy, which has resulted in a fragmented body of evidence. In this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to provide more robust and comprehensive evidence for the prenatal diagnosis of fetal CHD.

2.1 Guideline Compliance and Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in strict accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) statement [8]. The completed PRISMA-DTA checklist is provided in Table S1. The study protocol was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO registration number: CRD420251109097).

Eight databases (Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Biology Medicine (CBM), WanFang Database, VIP, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus) were systematically searched to obtain literature on 4D ultrasound diagnosis of fetal CHD. The search period was from the inception of each database to 22 July 2025. The search terms included “four-dimensional ultrasound”, “congenital heart disease”, among others. The search strategy employed a combination of subject headings and free words. Taking the PubMed database as an example, the search strategy was constructed by combining keywords and synonyms related to “congenital heart disease” (e.g., “Congenital heart disease” OR “Heart Abnormality”) with terms for “four-dimensional ultrasound” using the Boolean operator “AND”. The detailed search strategies for all databases are provided in Table S2.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Study type: Diagnostic accuracy studies evaluating 4D ultrasound for fetal CHD; (2) Participants: Pregnant women undergoing prenatal 4D ultrasound examination, with fetal CHD status confirmed by a reference standard (postnatal follow-up, echocardiography or autopsy); (3) Values for true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN), and true negative (TN) in the prenatal diagnosis of fetal CHD by 4D ultrasound could be obtained directly or indirectly.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies without full-text access, reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, etc.; (2) Literature with duplicate data; (3) Literature lacking follow-up information after fetal birth; (4) Literature assessed as having a high risk of bias according to the literature quality assessment results.

The retrieved records were imported into Endnote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, US). Two investigators independently screened the records. For the studies meeting the inclusion criteria, the following information was extracted using a standardized form: first author, year of publication, ultrasound system (Manufacturer/Model), probe frequency (MHz), gestational age range at examination (weeks), average gestational age (weeks), and diagnostic outcome (TP, FP, FN, TN). If diagnostic outcomes were not directly or explicitly reported in the literature, two investigators independently derived them from the available data and cross-checked the calculations.

Handling of missing data: For missing baseline characteristics (e.g., average gestational age), we attempted to contact the corresponding authors via email to request the missing information. If no response was received or the data were unavailable, these variables were treated as missing. Consequently, analyses involving these specific variables (such as the subgroup analysis by gestational age) were restricted to the subset of studies that reported complete data.

Two investigators independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2) [9]. This tool mainly consists of four parts: (1) patient selection; (2) index test; (3) reference standard; (4) flow and timing. After the evaluation was completed, the evaluation results of the two investigators were compared. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third investigator. The Review Manager (RevMan) software (version 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration) was used to generate the risk-of-bias graph.

The meta-analysis was performed using the midas command in Stata 16.0 (StataCorp, USA). A bivariate random-effects model was fitted to jointly pool the estimates of sensitivity and specificity, accounting for the inherent negative correlation between them within studies. This model incorporates random effects at the study level to address the heterogeneity in both logit(sensitivity) and logit(specificity) across studies. The results are presented as pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve was derived from the bivariate model parameters, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Subgroup meta-analysis was performed based on average gestational weeks to explore the range of optimal diagnostic gestational weeks. If significant heterogeneity persisted, meta regression was applied to analyze the cause of heterogeneity. Deeks’ funnel plot was performed to assess potential publication bias, with a significance level of p < 0.05 indicating significant asymmetry suggestive of publication bias. If publication bias was present, the trim-and-fill method was employed to adjust for potential bias, and the robustness of the results was assessed [10]. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

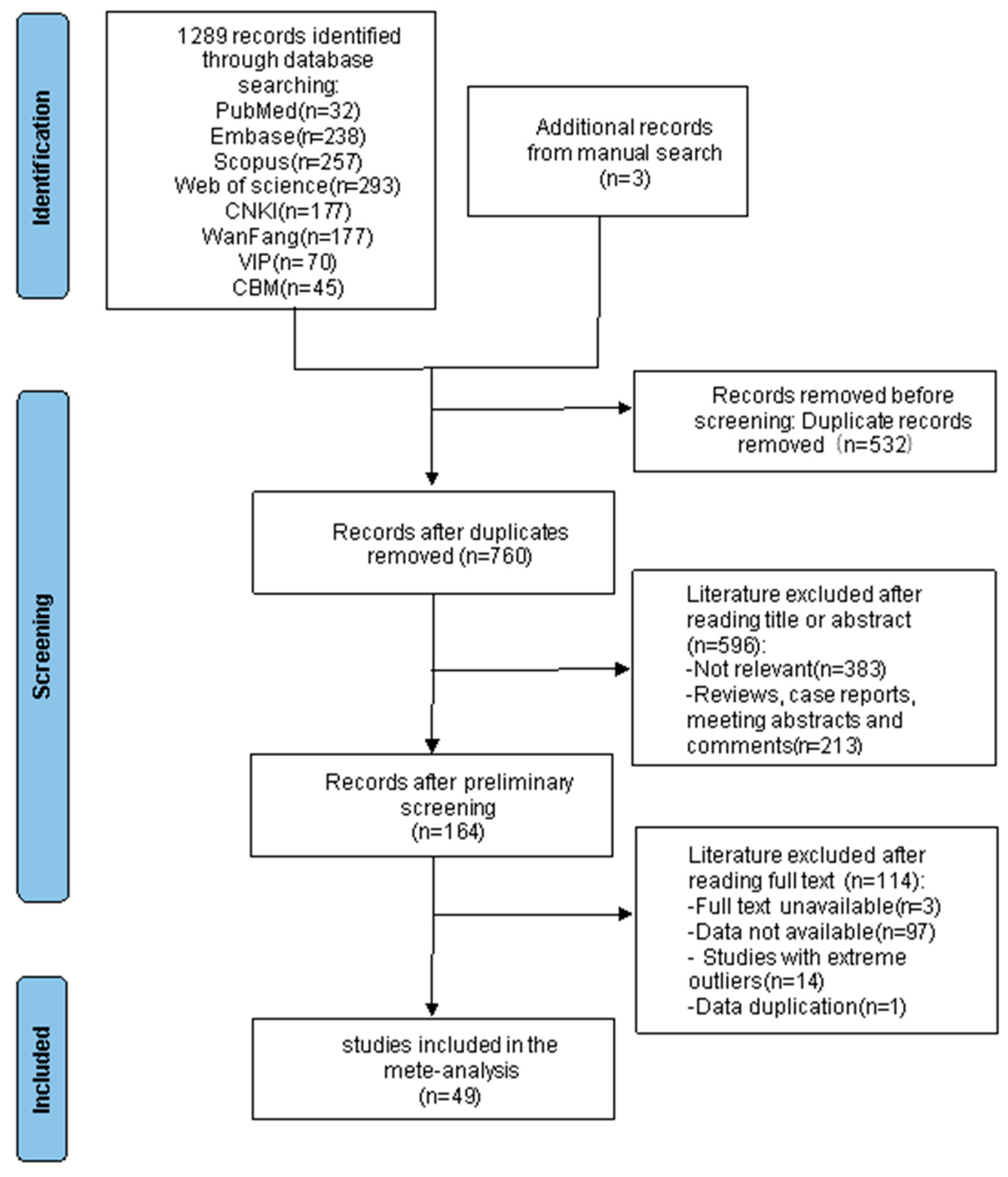

A total of 1289 articles were retrieved from Chinese and English databases, and 3 additional articles were identified through by manual search. After removing 545 duplicates using EndNote software, 747 records remained. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of these records against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 581 articles. Subsequently, the two reviewers independently assessed the full texts of the remaining articles. Through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer when disagreements arose, 49 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. The study selection process is detailed in Fig. 1 (PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1: Flowchart of the study selection process.

3.2 Characteristics of the Included Studies

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 49 studies were included, consisting of 4 prospective studies and 45 retrospective studies. A total of 23,397 fetuses were examined, among which 2115 fetuses were diagnosed with CHD. The gestational age at the time of 4D ultrasound examination ranged from 11 to 39 weeks across the studies. The key characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table S3.

3.3 Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

The QUADAS-2 assessment indicated that while the overall methodological quality was acceptable, the dominant sources of risk or uncertainty were identified in three domains: Patient Selection, Reference Standard, and Flow and Timing. Specifically, these risks primarily stemmed from the following aspects: some studies did not adequately specify whether consecutive or random samples were used; others failed to clarify whether reference standards were interpreted blindly; and a small number of studies excluded a limited number of patients from the analysis due to loss to follow-up. The summary risk-of-bias graph was presented in Fig. S1.

A meta-analysis with 49 included studies revealed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001). The bivariate box plot (Fig. S2) showed that 5 studies fell outside the center region and 42 studies were within the center region, indicating substantial heterogeneity among studies.

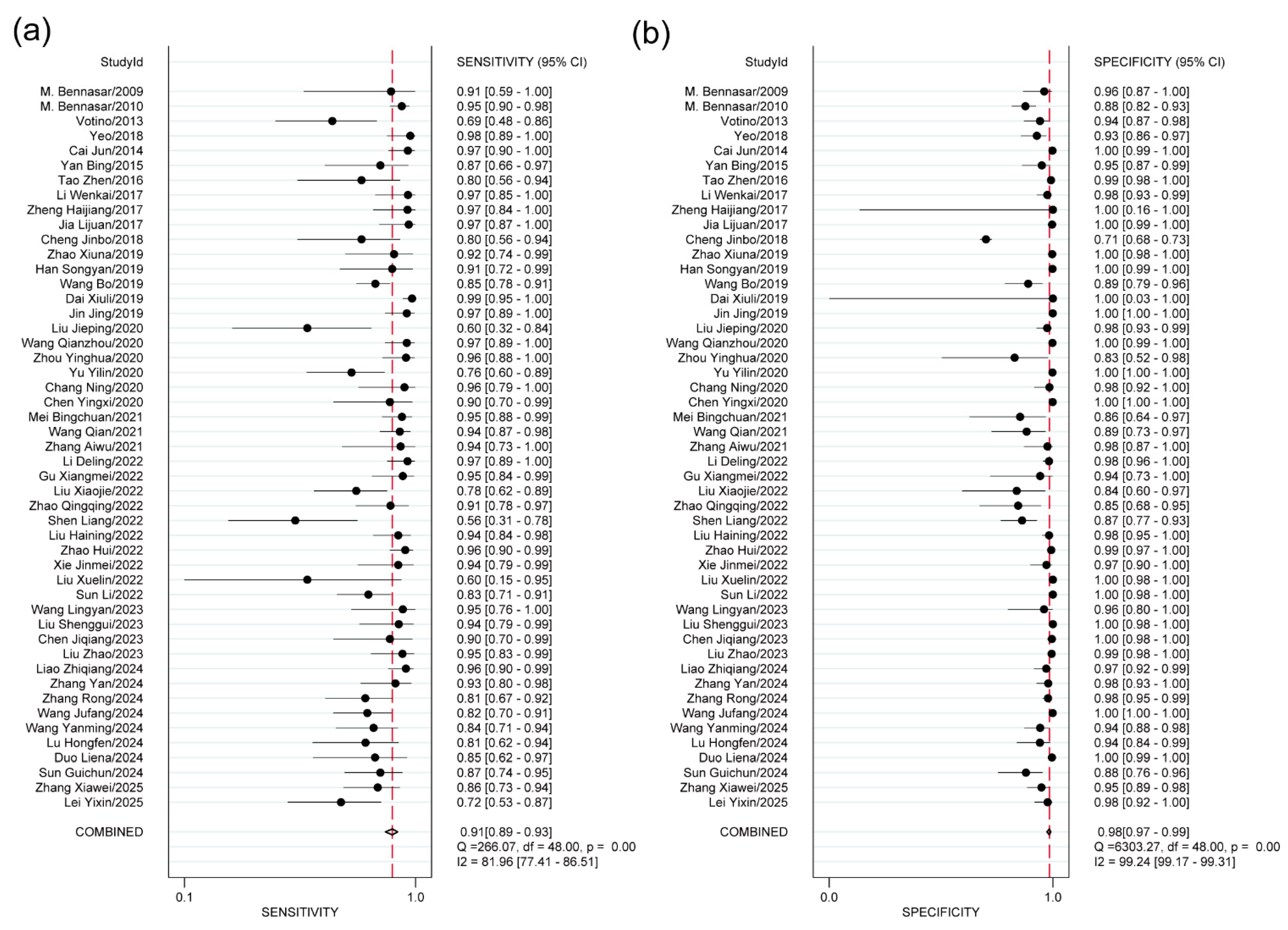

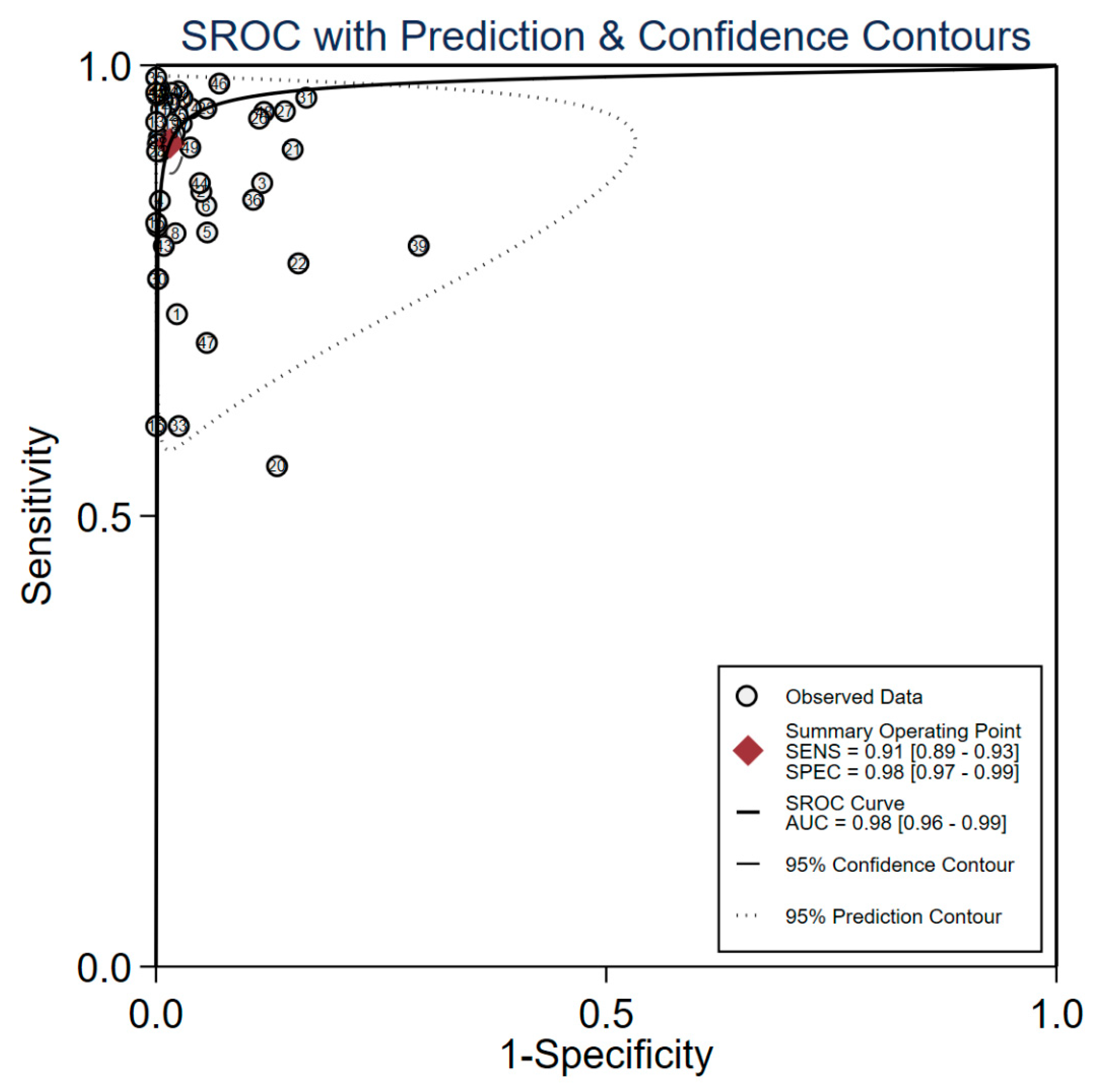

A bivariate random-effects model was used to quantify the diagnostic accuracy metrics. A bivariate random effects model meta-analysis was performed based on the results of heterogeneity test. The overall sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.93), 0.98 (95% CI: 0.97–0.99), 58.93 (95% CI: 35.02–99.15), 0.09 (95% CI: 0.07–0.11), 439.74 (95% CI: 244.89–789.63) and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99). The forest plots of the pooled sensitivity and specificity are shown in Fig. 2, and the SROC curve is presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 2: Forest plots of the pooled sensitivity and specificity. (a) the Forest plot of pooled sensitivity; (b) the Forest plot of pooled specificity.

Figure 3: The SROC curve Abbreviations: SROC: summary receiver operating characteristic.

3.5 Meta-Analysis of Subgroups by Average Gestational Age

A subgroup meta-analysis was conducted on the 39 studies that reported average gestational age. As shown in Table 1, 4D ultrasound was able to detect CHD as early as 11 weeks, albeit with a lower pooled sensitivity of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.15–0.95). When the average gestational age reached 20 weeks (range: 14–28 weeks), both the pooled sensitivity (0.94; 95% CI: 0.84–0.98) and specificity (0.94; 95% CI: 0.83–0.99) were high. This high diagnostic performance was maintained within the 20–28 weeks range. However, a significant decrease in pooled sensitivity to 0.60 (95% CI: 0.32 to 0.84) was observed at an average gestational age of 32 weeks.

Table 1: Meta-analysis of subgroups of average gestational weeks.

| Average Gestational Age (Weeks) | Gestational Age Range (Weeks) | Number of Literature (n) | Number of Fetuses | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 12–15 | 1c | 215 | 0.60 (0.15–0.95) | 1.00 (0.98–1.00) | 0.80 (0.53–1.00) |

| 15 | 13–24 | 1c | 90 | 0.96 (0.79–1.00) | 0.98 (0.92–1.00) | 0.97 (0.92–1.00) |

| 16 | NA | 1c | 206 | 0.85 (0.78–0.91) | 0.89 (0.79–0.96) | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) |

| 17 | 11–25 | 3b | 4413 | 0.81 (0.71–0.89) | 0.92 (0.91–0.93) | N/A |

| 20 | 14–28 | 2b | 258 | 0.94 (0.84–0.98) | 0.94 (0.83–0.99) | N/A |

| 21 | 17–24 | 1c | 85 | 0.87 (0.66–0.97) | 0.95 (0.87–0.99) | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) |

| 22 | 18–30 | 1c | 150 | 0.86 (0.73–0.94) | 0.95 (0.89–0.98) | 0.91 (0.84–0.07) |

| 23 | 18–26 | 5a | 6417 | 0.89 (0.91–0.94) | 0.99 (0.95–1.00) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) |

| 24 | 16–31 | 10a | 1806 | 0.92 (0.88–0.95) | 0.98 (0.94–0.99) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) |

| 25 | 21–29 | 7a | 4741 | 0.94 (0.84–0.98) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

| 26 | 13–38 | 4a | 1875 | 0.86 (0.78–0.92) | 0.99 (0.92–1.00) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) |

| 27 | 18–39 | 1c | 413 | 0.95 (0.83–0.99) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.97 (0.93–1.00) |

| 28 | 24–37 | 1c | 360 | 0.92 (0.74–0.99) | 1.00 (0.98–1.00) | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

| 32 | 22–38 | 1c | 135 | 0.60 (0.32–0.84) | 0.98 (0.93–0.99) | 0.79 (0.63–0.94) |

Due to significant heterogeneity among the 49 included studies, meta-regression analysis was performed to explore potential sources. Covariates were coded as follows:

(1) Study design: Retrospective studies = 0, prospective studies = 1; (2) Sample size: <300 = 0, ≥300 = 1; (3) Maternal risk status: No high-risk factors = 0, presence of high-risk factors = 1; (4) Prior suspicion of fetal CHD: Suspected before 4D ultrasound = 1, not suspected = 0; (5) STIC technology integration: 4D ultrasound without STIC = 0, with STIC = 1; (6) Ultrasound system origin: China = 1, Austria = 2, other regions = 3.

Meta-regression identified sample size and prior suspicion of fetal CHD as significant sources of heterogeneity (p < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2: Meta-regression analysis of potential sources of heterogeneity.

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | −1.46 | 0.99 | −1.47 | 0.14 |

| Sample size | 1.36 | 0.66 | 2.05 | 0.04 |

| Maternal risk status | −0.28 | 0.67 | −0.41 | 0.68 |

| Prior suspicion of fetal CHD | −1.87 | 0.71 | −2.65 | 0.01 |

| STIC technology integration | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| Ultrasound system origin | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.75 |

3.7 Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

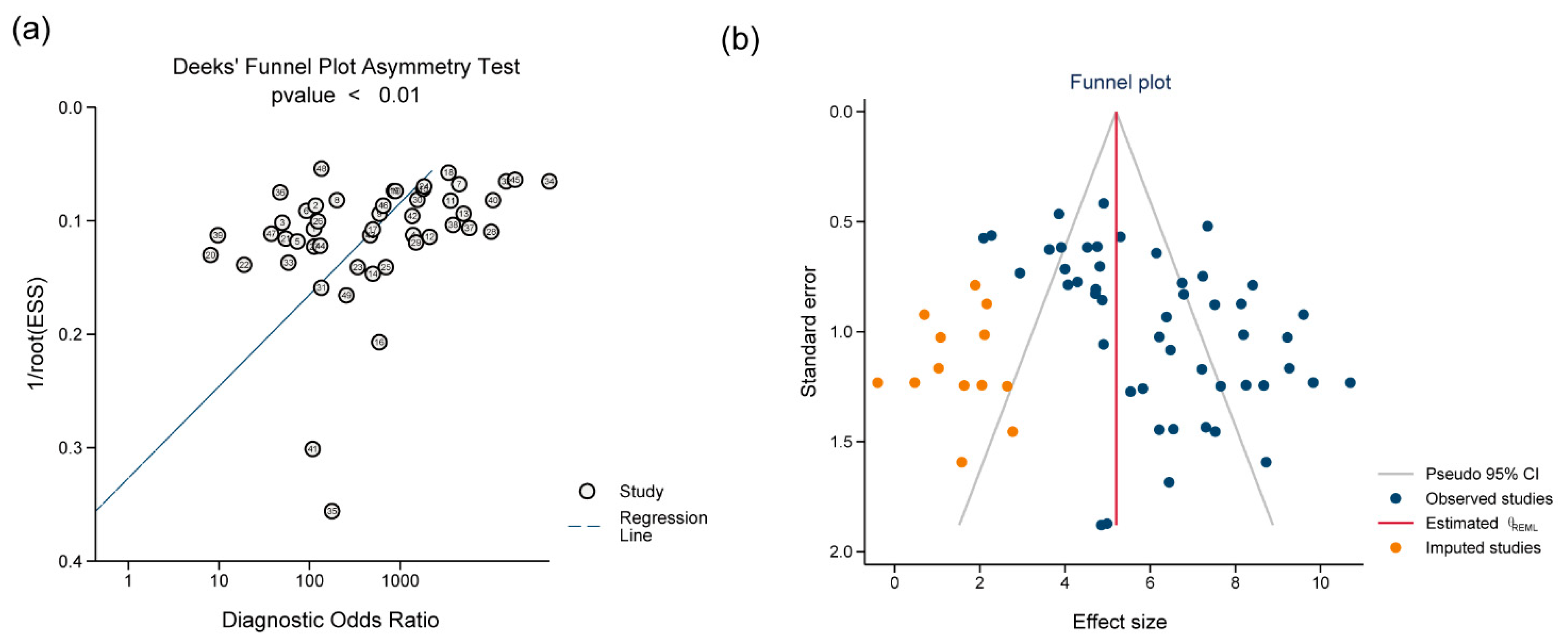

Sensitivity analysis, performed by excluding the five outlier studies identified in the bivariate box plot (Fig. S2), demonstrated that the pooled effect estimates remained largely unchanged (details in Table S4). Deeks’ funnel plot asymmetry test indicated significant asymmetry (p < 0.01), suggesting the presence of potential publication bias. The trim-and-fill method (using the linear estimator) was applied to adjust for this potential bias, imputing 13 hypothetical missing studies on the left side of the funnel plot. Following adjustment, the funnel plot showed reduced asymmetry. Funnel plots before and after trim-and-fill adjustment are presented in Fig. 4. The adjusted pooled DOR decreased to 181.53 (95% CI: 94.46–348.85) from the original 439.74 (95% CI: 244.89–789.63). Despite this attenuation, the adjusted DOR remained statistically significant (95% CI excluding 1).

Figure 4: Funnel plots (a) Deeks’ funnel plot; (b) the funnel plot after trim-and-fill adjustment.

CHD severely affects intrauterine fetal development and neonatal survival, and its etiology is multifactorial and not fully understood [11]. Currently, a large number of studies have concluded that maternal pregnancy status, environmental and genetic factors can contribute to its development [12,13,14]. Therefore, effective prenatal screening of pregnant women, early diagnosis of fetal CHD at an early stage, and timely termination of pregnancy or timely treatment after delivery can reduce the adverse prognosis and improve the quality of birth. Conventional 2D ultrasound is an important screening tool for CHD, but it can only provide planar views of cardiac structures [15], which may lead to missed or misdiagnosed cases, and it performs poorly in detecting complex cardiac malformations [16]. Furthermore, its diagnostic performance is operator-dependent and can be influenced by instrumentation, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal position, with a wide range of detection rates [17,18,19]. Compared with two-dimensional ultrasound, prenatal four-dimensional ultrasound provides superior image clarity and stereoscopic visualization, leading to higher diagnostic accuracy. This is particularly advantageous for detecting subtle anomalies such as cardiac septal defects and valvular abnormalities, as well as complex structural heart diseases, thereby significantly enhancing diagnostic efficacy [20]. Additionally, the combination of 4D ultrasound with STIC technology enables automated acquisition of fetal cardiac volume datasets, facilitating offline analysis. This combination not only saves examination time but also reduces operator-dependent errors, compensating for the key limitations of 2D ultrasonography.

The results of this meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled sensitivity of 0.91 for 4D ultrasound in diagnosing fetal CHD. This finding not only surpasses the overall sensitivity (0.69) of 2D echocardiography reported by Zhang et al., but also exceeds the sensitivity of the isolated four-chamber view (0.49) and the combination of four-chamber and outflow tract views (0.58) documented in their study. Even compared to their highest-sensitivity protocol combining four-chamber, outflow tract, and three-vessel-trachea views (0.74), 4D ultrasound shows an improvement of approximately 17 percentage points, highlighting its substantial advantage in holistic spatial structural assessment [21]. Additionally, the sensitivity of 0.91 is moderately higher than the 0.75 sensitivity for first-trimester (11–14 weeks) fetal echocardiography in diagnosing CHD reported by Yu et al. [22]. Notably, Yu et al. emphasized that while first-trimester screening is clinically feasible, it cannot replace second-trimester examinations due to the risk of missed diagnoses caused by the progressive intrauterine development of certain cardiac anomalies (e.g., valvulopathies, aortic coarctation). However, 4D ultrasound—through its dynamic volumetric imaging capabilities—not only provides more comprehensive spatial information to enhance early detection of complex malformations (reflected in its higher sensitivity) but also reduces fetal cardiac exposure time due to shorter examination durations [23,24,25]. Thus, it achieves improved diagnostic performance while concurrently ensuring safety, offering clinicians an efficient and risk-controllable diagnostic tool.

This meta-analysis demonstrated substantial heterogeneity. Meta-regression identified sample size and prior suspicion of fetal CHD as the significant sources of heterogeneity. Sample size directly impacts result stability and effect size estimation; small samples increase heterogeneity due to greater random fluctuations, while larger samples provide more stable estimates. Thus, differences in sample size across studies themselves contribute to heterogeneity. Furthermore, the selective inclusion of high-risk fetuses in the included retrospective studies may introduce spectrum bias. While the pooled sensitivity (0.91) suggests excellent performance, these results reflect accuracy in prevalence-enriched referral centers rather than routine screening settings. Caution is warranted when extrapolating to the general low-risk population. In such settings, where CHD prevalence is low, the Positive Predictive Value (PPV) drops significantly even if sensitivity remains high. Consequently, the utility of 4D ultrasound in unselected screening is limited by a higher rate of false positives, meaning a positive finding is less likely to indicate a true anomaly compared to high-risk cohorts. In addition to study design and patient characteristics, methodological variations in 4D ultrasound techniques likely contributed significantly to the observed statistical heterogeneity, although these factors could not be fully quantified due to inconsistent reporting in primary studies. The term ‘4D ultrasound’ encompasses a spectrum of advanced imaging modalities, including Spatio-Temporal Image Correlation (STIC), Tomographic Ultrasound Imaging (TUI), and volume rendering, each possessing distinct diagnostic strengths. For instance, STIC is superior for assessing valvular motion and dynamic blood flow (especially when combined with color Doppler), whereas TUI excels in multi-planar structural assessment [26,27]. Furthermore, heterogeneity in acquisition protocols—such as the specific cardiac planes analyzed and the application of diverse post-processing software—inevitably leads to variability in diagnostic performance. Consequently, the ‘overall’ performance of 4D ultrasound reported here represents an aggregate of these diverse methodologies, implying that the standardization of imaging protocols could further enhance diagnostic consistency in future practice. Nevertheless, sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of our primary findings: exclusion of outlier studies did not materially alter the pooled effect estimates. This consistency underscores the validity of the conclusion that 4D ultrasound maintains high diagnostic efficacy for fetal CHD despite these diverse sources of heterogeneity. Notably, maternal age, contrast dose, operator technique, and clinician experience may also contribute to heterogeneity. However, incomplete reporting of these variables in the primary studies precluded their inclusion as covariates in the regression models.

There are no conclusive findings regarding the optimal gestational age for early ultrasound screening for fetal CHD. Our subgroup analysis suggests that the pooled sensitivity and specificity of 4D ultrasound for the diagnosis of CHD were higher when the average gestational age was 20 weeks, corresponding to a range of 14 to 28 weeks, which is similar to the findings of previous study [28]. Some studies have concluded that it is reasonable and feasible to perform fetal cardiac ultrasound as early as after 12 weeks of gestation [29]. Overall, moving the screening time from 20–24 weeks’ gestation forward can provide more options for high-risk pregnant women and their families. Earlier detection of fetal CHD facilitates timely examination and intervention, reducing the physical and psychological trauma associated with termination of pregnancy at advanced gestational ages [30,31]. However, earlier screening may also result in missed diagnoses of some malformations, such as mild valve stenosis and smaller ventricular septal defects [32]. Therefore, a staged and individualized screening strategy is recommended in clinical practice. For high-risk pregnant women, early fetal echocardiography screening can be attempted at 13 to 16 weeks of gestation for early recognition of severe structural malformations. For low-risk pregnant women or routine screening, systematic fetal malformation screening is recommended at 20–24 weeks of gestation, when fetal organs are fully developed and the images are clearer with more amniotic fluid, which helps to increase the detection rate of subtle structural anomalies and reduce the risk of underdiagnosis.

Overall, 4D ultrasound demonstrates high accuracy and sensitivity in fetal CHD diagnosis, which helps reduce the risk of missed and misdiagnosis, and can be used as an important means of fetal CHD screening during pregnancy, providing a reliable basis for prenatal screening. However, this study has several limitations: (1) The majority of included studies were retrospective in design, which may introduce selection bias; (2) Most studies were conducted within single centers in China, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations and healthcare settings; (3) Significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, despite our comprehensive investigation of potential sources.

In conclusion, the pooled sensitivity, pooled specificity, diagnostic odds ratio and AUC of the SROC curve indicate that 4D ultrasound exhibits high diagnostic efficacy for fetal CHD. The optimal diagnostic window occurs when the average gestational age is 20 weeks (gestational age range: 14–28 weeks), during which both sensitivity and specificity reach an optimal level. Future studies should focus on further refining ultrasound technology for early diagnosis and intervention of fetal CHD.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Open Research Fund of National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Birth Defects Prevention & Henan Key Laboratory of Population Defects Prevention (ZD202308). The funder of this study had no role in the data collection, study design, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit for publication.

Author Contributions: Yuanyuan Li, Panpan Sun, and Zhiguang Ping conceived the study; Xingyue Wang, Yucan Deng, and Runfang Tian collected the data; Yuanyuan Li, Xingyue Wang, Yucan Deng, Runfang Tian, and Jinfeng Zhao performed data analysis and visualization; Li Liu and Zhiguang Ping supervised the project; Yuanyuan Li drafted the manuscript which was revised following critical review by Li Liu, Panpan Sun, and Zhiguang Ping. Zhiguang Ping acquired funding and validated the results. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets supporting this meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request following publication.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.075611/s1. Fig. S1. The summary risk-of-bias graph; Fig. S2. Bivariate boxplot; Table S1. PRISMA-DTA checklist; Table S2. Complete search strategies for eight databases; Table S3. Characteristics of included studies. Table S4. Sensitivity analysis results.

References

1. Srisupundit K , Luewan S , Tongsong T . Prenatal diagnosis of fetal heart failure. Diagnostics. 2023; 13( 4): 719. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13040779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wu YY , Yang JT , Qin CH , Yang JE , Dou TJ . Analysis of the value of multisection echocardiography for the early diagnosis of congenital heart disease and the factors influencing the missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis. Clin J Med Off. 2022; 50( 08): 839– 730. (In Chinese). doi:10.16680/j.1671-3826.2022.08.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang YM , Wang LF , Zang HF , Wang J , Wu H , Zhao W . Comparison of different ultrasonic screening methods and analysis of high risk factors for fetal cardiac malformation in second trimester of pregnancy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2024; 46( 4): 769– 77. (In Chinese). doi:10.1007/s00246-024-03525-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hata T , Kanenishi K , Mori N , Yazon AO , Hanaoka U , Tanaka H . Four-dimensional color Doppler reconstruction of the fetal heart with glass-body rendering mode. Am J Cardiol. 2014; 114( 10): 1603– 6. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Viñals F , Poblete P , Giuliano A . Spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC): A new tool for the prenatal screening of congenital heart defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 22( 4): 388– 94. doi:10.1002/uog.883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu HY , Liang X , Wang XL , Luo L , Wang HH . The Application value of two-dimensional ultrasound combined with four-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of fetal heart malformation. Chin J Birth Health Heredity. 2019; 27( 02): 217– 36. (In Chinese). doi:10.13404/j.cnki.cjbhh.2019.02.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bravo-Valenzuela NJ , Giffoni MC , Nieblas CO , Werner H , Tonni G , Granese R , et al. Three-Dimensional Ultrasound for Physical and Virtual Fetal Heart Models: Current Status and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2024; 13( 24): 7605. doi:10.3390/jcm13247605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. McInnes MDF , Moher D , Thombs BD , McGrath TA , Bossuyt PM , Clifford T , et al. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA. 2018; 319( 4): 388– 96. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wade R , Corbett M , Eastwood A . Quality assessment of comparative diagnostic accuracy studies: Our experience using a modified version of the QUADAS-2 tool. Res Synth Methods. 2013; 4( 3): 280– 6. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Duval S , Tweedie R . Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000; 56( 2): 455– 63. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Meng X , Song M , Zhang K , Lu W , Li Y , Zhang C , et al. Congenital heart disease: Types, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. MedComm. 2024; 5( 7): e631. doi:10.1002/mco2.631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang DW , Zhu YB , Zhou SJ , Chen XH , Li HB , Liu WJ , et al. Maternal cardiovascular health in early pregnancy and the risk of congenital heart defects in offspring. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024; 24( 1): 325. doi:10.1186/s12884-024-06529-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nie X , Liu X , Wang C , Wu Z , Sun Z , Su J , et al. Assessment of evidence on reported non-genetic risk factors of congenital heart defects: The updated umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22( 1): 371. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-04600-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang X , Qi M , Fu Q . Molecular genetics of congenital heart disease. Sci China Life Sci. 2025; 68( 8): 2225– 42. doi:10.1007/s11427-024-2861-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yagel S , Cohen SM , Rosenak D , Messing B , Lipschuetz M , Shen O , et al. Added value of three-/four-dimensional ultrasound in offline analysis and diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 37( 4): 432– 7. doi:10.1002/uog.8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ding GF , Liu JH . Analysis of the accuracy of ultrasound screening for fetal congenital heart disease. Med Forum. 2025; 29( 09): 36– 9. (In Chinese). doi:10.19435/j.1672-1721.2025.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. DeVore GR , Medearis AL , Bear MB , Horenstein J , Platt LD . Fetal echocardiography: Factors that influence imaging of the fetal heart during the second trimester of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1993; 12( 11): 659– 63. doi:10.7863/jum.1993.12.11.659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tegnander E , Eik-Nes SH . The examiner’s ultrasound experience has a significant impact on the detection rate of congenital heart defects at the second-trimester fetal examination. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 28( 1): 8– 14. doi:10.1002/uog.2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang J , Xiao S , Zhu Y , Zhang Z , Cao H , Xie M , et al. Advances in the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024; 37( 5): 550– 61. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2023.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pinheiro DO , Varisco BB , Silva MBD , Duarte RS , Deliberali GD , Maia CR , et al. Accuracy of Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Cardiac Malformations. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2019; 41( 1): 11– 6. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang YF , Zeng XL , Zhao EF , Lu HW . Diagnostic Value of Fetal Echocardiography for Congenital Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94( 42): e1759. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yu D , Sui L , Zhang N . Performance of First-Trimester Fetal Echocardiography in Diagnosing Fetal Heart Defects: Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. J Ultrasound Med. 2020; 39( 3): 471– 80. doi:10.1002/jum.15123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cheng JB . Analysis of the clinical diagnostic value of four-dimensional ultrasonography with STIC for fetal congenital heart disease in early pregnancy. China Med Device Inform. 2018; 24( 22): 95– 6. (In Chinese). doi:10.15971/j.cnki.cmdi.2018.22.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tonni G , Centini G , Taddei F . Can 3D ultrasound and doppler angiography of great arteries be included in second trimester ecocardiographic examination? A prospective study on low-risk pregnancy population. Echocardiography. 2009; 26( 7): 815– 22. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00874.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Turan S , Turan OM , Desai A , Harman CR , Baschat AA . First-trimester fetal cardiac examination using spatiotemporal image correlation, tomographic ultrasound and color Doppler imaging for the diagnosis of complex congenital heart disease in high-risk patients. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 44( 5): 562– 7. doi:10.1002/uog.13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Araujo Júnior E , Tonni G , Bravo-Valenzuela NJ , Da Silva Costa F , Meagher S . Assessment of Fetal Congenital Heart Diseases by 4-Dimensional Ultrasound Using Spatiotemporal Image Correlation: Pictorial Review. Ultrasound Q. 2018; 34( 1): 11– 7. doi:10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Paladini D , Vassallo M , Sglavo G , Lapadula C , Martinelli P . The role of spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC) with tomographic ultrasound imaging (TUI) in the sequential analysis of fetal congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 27( 5): 555– 61. doi:10.1002/uog.2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Allan L . Technique of fetal echocardiography. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004; 25( 3): 223– 33. doi:10.1007/s00246-003-0588-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wiechec M , Knafel A , Nocun A . Prenatal detection of congenital heart defects at the 11- to 13-week scan using a simple color Doppler protocol including the 4-chamber and 3-vessel and trachea views. J Ultrasound Med. 2015; 34( 4): 585– 94. doi:10.7863/ultra.34.4.585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Spingler T , Sonek J , Hoopmann M , Prodan N , Abele H , Kagan KO . Complication rate after termination of pregnancy for fetal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 62( 1): 88– 93. doi:10.1002/uog.26157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Davies V , Gledhill J , McFadyen A , Whitlow B , Economides D . Psychological outcome in women undergoing termination of pregnancy for ultrasound-detected fetal anomaly in the first and second trimesters: A pilot study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 25( 4): 389– 92. doi:10.1002/uog.1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang S , Qin G , He G , Liang M , Liang Y , Luo S , et al. Evaluation of first-trimester ultrasound screening strategy for fetal congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025; 65( 4): 478– 86. doi:10.1002/uog.29186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools