Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Right Axillary Thoracotomy for Anomalous Aortic Origin of a Coronary Artery in Children

1 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 400014, China

2 Chongqing Key Laboratory of Structural Birth Defect and Reconstruction, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Child Development and Disorders, National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders, Chongqing, 400014, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yonggang Li. Email: ; Yuhao Wu. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 693-702. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2026.076517

Received 21 November 2025; Accepted 05 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Background: There has been an increasing number of studies documenting the application of the right axillary thoracotomy (RAT) approach for the repair of congenital heart diseases. However, no research has reported the RAT approach in repairing the anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery (AAOCA). This study aims to investigate the feasibility and safety of the RAT approach for repairing AAOCA in children. Methods: We performed a retrospective study at the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University between January 2024 and October 2025 to investigate the clinical outcomes of the RAT approach for repairing AAOCA in children. Results: A total of twelve patients with AAOCA were operated on via a RAT approach. Conventional unroofing was performed in eight cases, and a modified unroofing procedure was performed in four cases. Simultaneous repair of associated cardiac defects was conducted in eight cases. Postoperative pneumonia occurred in one patient. There were no early deaths during the hospitalization. The postoperative ostial diameter was significantly larger than the preoperative diameter (p = 0.0005). No patients were lost to follow-up, and aortic valve insufficiency was not observed during the follow-up. There were no late deaths reported following discharge, and ischemic signs were also not documented. Conclusions: Surgical repair via the RAT approach may serve as a safe and effective alternative for children with AAOCA. However, surgical strategies should be carefully determined based on preoperative assessment of the anomalous coronary arteries.Keywords

Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery (AAOCA) is a rare congenital heart disease (CHD) where a coronary artery originates abnormally from the aorta [1]. AAOCA can lead to myocardial ischemia and sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes [2]. Due to limited understanding of risk factors for myocardial ischemia, indications of surgery remain debated. Generally, patients with an anomalous left coronary artery arising from the right sinus of Valsalva (ALCA) require surgical repair [3]. In contrast, in patients with an anomalous right coronary artery arising from the left sinus of Valsalva (ARCA), surgery is indicated for symptomatic individuals who exhibit signs of myocardial ischemia [1]. Surgical repair of AAOCA can be performed efficiently and safely with low mortality and incidence of complications [4]. Common surgical techniques include unroofing, coronary reimplantation, pulmonary artery translocation, and neo-ostium creation [5].

Median sternotomy is standard for CHD repair but may lead to chest wall deformity like pectus excavatum later in life [6], along with cosmetic concerns [7]. Recent studies have reported using the right axillary thoracotomy (RAT) approach for various CHDs such as atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC), and partial atrioventricular septal defect (PAVSD) [8,9,10]. To the best of our knowledge, no research has employed the RAT approach specifically for repairing AAOCA in children. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the feasibility and safety of the RAT approach for repairing AAOCA in children.

We conducted a retrospective case series at the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (CHCQMU). This study received approval from the Ethical Committee of CHCQMU (2025479). Our research adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [11]. We consecutively involved patients under 18 years of age who underwent AAOCA repair via the RAT approach between January 2024 and October 2025. Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to operations.

2.2 Demographics, Diagnosis, and Postoperative Outcomes

We collected data on sex, age, coronary artery origin, symptoms, electrocardiogram (EKG), and combined CHDs prior to surgery. The diagnosis of AAOCA was confirmed through transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) [12]. We repaired AAOCA via the RAT approach in patients meeting these criteria: (1) Isolated ALCA; (2) Isolated ARCA with signs of myocardial ischemia; or (3) Combined CHDs requiring simultaneous interventions. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Critical conditions needing emergency operations or preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support; (2) Prior right thoracotomy history; or (3) Absence of an intramural course. We recorded clinical outcomes such as coronary artery courses, surgical techniques, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) duration, cross-clamp time, mechanical ventilation time, intensive care unit (ICU) stay length, postoperative hospital stay duration, complications, and follow-up data. All patients underwent TTE and coronary CTA before discharge. Each patient received oral aspirin for six months. Outpatient follow-ups were scheduled at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post-discharge.

AAOCA repair via the RAT approach was mainly performed by Dr. L. Y. G at our institution. Following general anesthesia, the left lung was ventilated. The patient was positioned in a left lateral decubitus posture, with the right arm elevated and placed over the head [13]. A 3 to 4 cm anterior-to-middle axillary vertical incision was made for access to the thoracic cavity through the fourth intercostal space. The pericardium was incised and retracted with traction sutures while preserving the phrenic nerve. CPB was conducted as usual.

In patients with isolated AAOCA, a single right atrial cannulation was performed, accompanied by left atrial drainage. For patients presenting with combined intracardiac defects, both vena cava were cannulated and snared. Careful dissection of the aortic root was conducted, particularly at the site where the coronary artery arose from the aorta. To enhance exposure during the operations, the inferior vena cava was cannulated via a separate incision, which subsequently served for chest tube placement. The cardioplegic cannula was removed following the infusion of cardioplegia. An aortotomy was performed, with the incision extended to allow visualization of the coronary ostia and proximal segment of the coronary artery. A coronary probe was used to assess the trajectory and length of the intramural segment.

In patients with a long intramural segment extending above the commissure, conventional unroofing was performed to ensure that the entire intramural segment was adequately unroofed, resulting in an unobstructed ostium originating from the appropriate sinus. To secure the intimal edges of the aortic wall, 7-0 interrupted Prolene sutures were utilized (Fig. 1A). In patients with a short intramural segment, conventional unroofing might not reposition the ostium to the appropriate sinus and could leave compression by the intercoronary pillar. We utilized a modified unroofing procedure, also known as aortocoronary window repair [14,15], for these cases (Fig. 1B). The intramural segment was carefully unroofed using fine scissors, followed by an ‘over-unroofing’ procedure to extend the aortic incision to the appropriate sinus. The anomalous coronary artery was also laterally incised. Subsequently, a side-to-side anastomosis with 7-0 interrupted sutures was then performed between the incised aortic wall and the anomalous coronary artery. This approach facilitated the creation of an unobstructed ostium originating from the appropriate sinus. If valve support structures were compromised, we resuspended the commissure accordingly. Upon completion of the operation, a transesophageal echocardiogram was conducted to assess both morphology and function of the aortic valves (AV).

Figure 1: Surgical procedures performed in this study. (A) Conventional unroofing procedure for patients with a long intramural segment extending above the commissure (1) ensures that the entire intramural segment is adequately unroofed (2, view from inside). This approach results in an unobstructed ostium originating from the appropriate sinus (3, view from outside). (B) Modified unroofing technique for patients with a short intramural segment (1) involves careful unroofing of the intramural segment using fine scissors, followed by an ‘over-unroofing’ procedure to extend the aortic incision to reach the appropriate sinus (2, short arrow). The anomalous coronary artery was also laterally incised (2, long arrow). Subsequently, a side-to-side anastomosis with 7-0 interrupted sutures was then performed between the incised aortic wall and the anomalous coronary artery (3) while preserving the proximal segment of the anomalous coronary artery intact (asterisk).

Descriptive statistics were employed to evaluate the demographic data of the included patients. Continuous variables were summarized using medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). The Shapiro-Wilk tests were utilized to assess normal distribution. We conducted a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test to compare the ostial diameters before and after surgical repair. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the GraphPad Prism 10.0 software.

Wed involved a total of twelve patients with AAOCA who underwent surgical repair via the RAT approach (Table 1). The median age at the time of surgery was 45.0 (IQR, 39.3 to 69.8) months. The median weight was 16.5 (IQR, 14.0 to 19.8) Kg. Diagnosis of AAOCA was confirmed through pre-operative TTE and coronary CTA for all patients included in our study. ARCA was diagnosed in eleven cases (Fig. 2), while ALCA was diagnosed in one case (Fig. 3A–D). All twelve cases had an interarterial anomalous coronary artery with an intramural course. Chest pain with exertion was observed in three cases, and syncope was noted in two cases. Abnormal EKG was found in two cases presenting with I° atrioventricular block, as well as three cases exhibiting ST-segment depression.

Figure 2: Pre-operative coronary CTA of ARCA. (A) Preoperative coronary CTA of a six-year-old child with ARCA. (B) Preoperative coronary CT of an eight-year-old child with ARCA. CTA Computed tomography angiography, ARCA Anomalous right coronary artery arises from the left sinus.

Figure 3: Three-dimensional reconstruction of CTA in a three-year-old child diagnosed with ALCA. (A,B) Pre-operative CTA indicates that the anomalous left coronary artery arises from the right sinus. (C,D) Post-operative CTA indicates that the left coronary artery arises from the correct sinus. CTA Computed tomography angiography, ALCA Anomalous left coronary artery arises from the right sinus.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of included patients.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Sex (Male/Female) | 7/5 |

| Age (months) | 45.0 [39.3–69.8] |

| Weight (kg) | 16.5 [14.0–19.8] |

| LVEF (%) | 67.5 [62.8–70.3] |

| Ostial diameter (mm) | 1.6 [1.2–1.7] |

| EKG | |

| I° AVB (n) | 2 |

| ST-segment depression (n) | 3 |

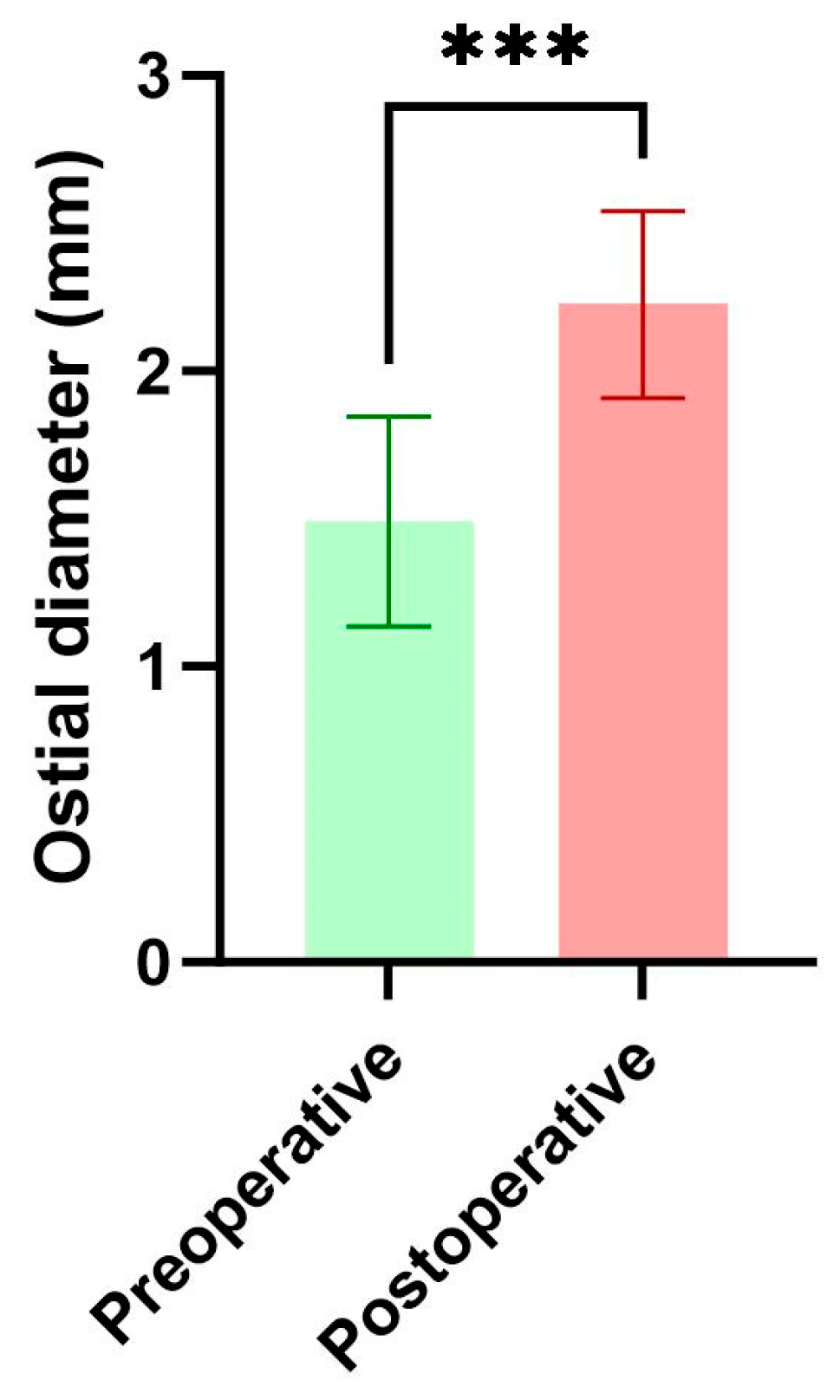

Surgical procedures are summarized in Table 2. Surgical indications included five patients with symptomatic ARCA, six patients with ARCA and concomitant CHDs, and one patient with ALCA. A slit-like orifice was found in nine patients (75%). Simultaneous repair of associated cardiac defects was conducted in eight cases. VSDs were repaired in four cases, ASDs were repaired in four cases, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) was ligated in one case, and mitral valvuloplasty was performed in two cases. Commissural resuspension was performed in two cases due to compromised valve support structures following the unroofing procedure. Conventional unroofing was performed in eight cases with a long intramural segment that travels above the commissure. Given that conventional unroofing could not reposition the ostium to the appropriate sinus, a modified unroofing procedure was performed in four cases with a short intramural segment (Fig. 4). Notably, we did not find any patients in this group with a single coronary ostium or an intramural course below the commissure. Consequently, procedures like coronary artery reimplantation, pulmonary artery translocation, or neo-ostium creation were not performed in this group. The median CPB time was 120.5 (IQR, 95.0 to 138.8) minutes (Table 3). The median cross-clamp time was 93.0 (IQR, 73.0–105.3) minutes. The median ventilation time was 6.5 (IQR, 3.5 to 8.8) hours. The median ICU stay was 4 (IQR, 3 to 4) days. The median postoperative hospital stay was 8 (IQR, 8 to 9) days. Postoperative pneumonia occurred in one patient but resolved following antibiotic treatment. There were no early deaths during the hospitalization. The postoperative ostial diameter was significantly larger than the preoperative diameter, as assessed by TTE before discharge (Fig. 5, p = 0.0005).

Figure 4: Intraoperative images and post-operative CTA in a three-year-old child diagnosed with ALCA via a RAT approach. (A) A coronary probe was employed to investigate the course of the normal RCA. (B) A coronary probe was employed to investigate the trajectory and length of the ALCA. (C) A neo-ostium was created by using a modified unroofing procedure to create an unobstructed ostium (asterisk) originating from the appropriate sinus. (D) Post-operative CTA of the coronary arteries following a modified unroofing procedure, with an asterisk indicating the LCA. CTA Computed tomography angiography, RCA Right coronary artery, LCA Left coronary artery, ALCA Anomalous left coronary artery arises from the right sinus, AC Aortic cannulation, LAD Left atrial drainage via the right superior pulmonary vein, RAC Right atrial cannulation.

Figure 5: Comparison of ostial diameters before and after surgical intervention (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, ***, p = 0.0005).

Table 2: Diagnoses and surgical procedures of included patients.

| Patients | Age (months) | Symptoms | Types of AAOCA | Combined CHDs | Operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 103 | Chest pain with exertion | ARCA, interarterial, short intramural segment, slitlike orifice | - | Modified unroofing |

| #2 | 14 | - | ARCA, interarterial, short intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 7 mm VSD | Modified unroofing + VSD repair |

| #3 | 9 | - | ARCA, interarterial, short intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 10 mm VSD | Modified unroofing + VSD repair |

| #4 | 63 | Syncope | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | - | Unroofing + Commissure resuspend |

| #5 | 49 | Syncope | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | - | Unroofing |

| #6 | 67 | Chest pain with exertion | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment | 8 mm ASD | Unroofing + ASD repair |

| #7 | 78 | - | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 9 mm ASD | Unroofing + ASD repair |

| #8 | 39 | - | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 10 mm ASD + 3 mm PDA | Unroofing + ASD repair + PDA ligation |

| #9 | 26 | - | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 8 mm VSD/Anterior mitral valve cleft | Unroofing + VSD repair + Mitral valvuloplasty |

| #10 | 37 | - | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment, slitlike orifice | 9 mm VSD/Anterior mitral valve prolapse | Unroofing + VSD repair + Mitral annuloplasty/Leaflet plication |

| #11 | 82 | Chest pain with exertion | ARCA, interarterial, long intramural segment | 3 mm ASD | Unroofing + ASD repair |

| #12 | 41 | - | ALCA, interarterial, short intramural segment | - | Modified unroofing + Commissure resuspend |

Table 3: Postoperative outcomes of included patients.

| Clinical Outcomes | |

|---|---|

| CPB time (minutes) | 120.5 [95.0–138.8] |

| Cross-clamp time (minutes) | 93.0 [73.0–105.3] |

| Mechanical ventilation (hours) | 6.5 [3.5–8.8] |

| ICU stay (days) | 4 [3, 4] |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 8 [8, 9] |

| Postoperative complications (n) | 1 |

| Early death (n) | 0 |

| Follow-up (months) | 10.5 [7.8–13.0] |

| Late death (n) | 0 |

| Residual myocardial ischemia (n) | 0 |

| AI insufficiency (n) | 0 |

No patients were lost to follow-up, and AV insufficiency was not observed in any of the patients during a median follow-up period of 10.5 (IQR, 7.8–13.0) months. Trivial-to-mild mitral valve regurgitation was observed in two patients who underwent simultaneous mitral valve repair. There were no late deaths reported following discharge, and ischemic signs were also not documented in symptomatic patients.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate clinical outcomes of the RAT approach for treating children with AAOCA. We successfully repaired AAOCA using the RAT approach in twelve children without early mortality or severe adverse events. By employing a single left lung ventilation strategy and appropriate pericardial suspension, we achieved satisfactory exposure without conversion to median sternotomy. The postoperative outcomes were generally acceptable when compared to the existing literature [15,16,17,18]. During a short-term follow-up, we did not observe late death, significant AV insufficiency, or residual ischemia within this group.

This method is beneficial as it meets cosmetic needs [9], reduces psychological stress on patients [19], and maintains breast symmetry and nipple sensitivity [20,21]. Hong et al. [22] noted that median sternotomy can cause chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum; however, no such malformations were reported in their RAT group during the follow-up. Similarly, Yan et al. [19] found no asymmetrical breast development or thoracic deformities with the RAT approach. In recent years, some surgeons have applied this technique to more complex conditions such as doubly committed VSD, tetralogy of Fallot, and cor triatriatum [8,13,23,24]. In 2015, Conway et al. [25] introduced upper hemisternotomy for AAOCA repair. As our experience grew over time, we began selectively performing surgical repairs for AAOCA via the RAT approach starting in 2024. In this group, we also use a modified unroofing technique in three children with short intramural segments. A recent review [26] suggests that conventional unroofing may be inadequate for patients with short intramural segments because of potential compression by the intercoronary pillar. However, in younger patients (Table 2, Patient #2 and Patient #3) requiring timely interventions due to other cardiac defects, coronary reimplantation can be challenging. Therefore, we repaired AAOCA using the modified unroofing procedure in two young patients (Patient #2 and #3) while preserving the proximal segment of the anomalous coronary artery intact (Fig. 1(B3)). We believe that this modified procedure allows the RAT approach to be feasible for both short and long intramural courses. Although clinical outcomes from the RAT approach are acceptable, surgeons should choose surgical methods based on preoperative evaluations rather than solely aiming for better cosmetic incisions [10]. Median sternotomy may be preferable for patients without an intramural course who require procedures like re-implantation or pulmonary artery translocation [1].

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, this was a retrospective analysis at a single institution with a limited number of participants, which may introduce selection bias. Second, the current study provides preliminary experience with the RAT approach for repairing AAOCA without comparison to median sternotomy. Third, the median age of this cohort is relatively young; thus, performing the RAT approach in adolescents may be challenging due to the aortic position being further from the chest wall [8]. Endoscopic instruments like forceps and needle holders could be considered for use in adolescents [13]. Lastly, while the modified unroofing is less complex in young children than reimplantation, additional commissural re-suspension might be necessary if valve support structures are compromised.

In conclusion, our study indicates that the RAT approach for surgical repair may be a safe and effective alternative for children with AAOCA. Surgical strategies should be tailored based on preoperative assessments of anomalous coronary arteries. Further prospective multi-center cohort studies are needed to compare the RAT approach with sternotomy in managing AAOCA.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82500029); Chongqing Postdoctoral Research Project Special Support (2023CQBSHTB3074); Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJQN202400421).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Kuo Li and Yuhao Wu; Data acquisition: Yue Tang; Analysis and data interpretation: Yonggang Li; Drafting of the manuscript: Kuo Li; Critical revision: Yuhao Wu. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data of this study were available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University approved this study (2025479).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to operations.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| RAT | Right axillary thoracotomy |

| CHD | Congenital heart disease |

| AAOCA | Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery |

| ALCA | An anomalous left coronary artery arising from the right sinus |

| ARCA | An anomalous right coronary artery arising from the left sinus |

| ASD | Atrial septal defect |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

| PAPVC | Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection |

| PAVSD | Partial atrioventricular septal defect |

| EKG | Electrocardiogram |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| CTA | Computed tomography angiography |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| AV | Aortic valve |

| IQR | Interquartile ranges |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

1. Mainwaring RD , Murphy DJ , Rogers IS , Chan FP , Petrossian E , Palmon M , et al. Surgical repair of 115 patients with anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery from a single institution. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2016; 7( 3): 693– 703. doi:10.1177/2150135116641892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Basso C , Maron BJ , Corrado D , Thiene G . Clinical profile of congenital coronary artery anomalies with origin from the wrong aortic sinus leading to sudden death in young competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35( 6): 1493– 501. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00566-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheezum MK , Liberthson RR , Shah NR , Villines TC , O’Gara PT , Landzberg MJ , et al. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery from the inappropriate sinus of Valsalva. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69( 12): 1592– 608. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mainwaring RD , Ma M , Maskatia S , Petrossian E , Reinhartz O , Lee J , et al. Outcomes of 230 patients undergoing surgical repair of anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2025; 119( 6): 1297– 305. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2025.01.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mery CM , Beckerman Z . What is the optimal surgical technique for anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery? Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2025; 28: 94– 100. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2025.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kenney LM , Obermeyer RJ . Pectus repair after prior sternotomy: clinical practice review and practice recommendations based on a 2,200-patient database. J Thorac Dis. 2023; 15( 7): 4114– 9. doi:10.21037/jtd-22-1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Luo H , Wang J , Qiao C , Zhang X , Zhang W , Song L . Evaluation of different minimally invasive techniques in the surgical treatment of atrial septal defect. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014; 148( 1): 188– 93. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Said SM , Greathouse KC , McCarthy CM , Brown N , Kumar S , Salem MI , et al. Safety and efficacy of right axillary thoracotomy for repair of congenital heart defects in children. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2023; 14( 1): 47– 54. doi:10.1177/21501351221127283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang X , Hu Y , Dong J , Huang P , Luo J , Yang G , et al. Rightvertical axillary incision for atrial septal defect: a propensity score matched study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022; 17( 1): 256. doi:10.1186/s13019-022-01999-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dodge-Khatami J , Noor R , Riggs KW , Dodge-Khatami A . Mini right axillary thoracotomy for congenital heart defect repair can become a safe surgical routine. Cardiol Young. 2023; 33( 1): 38– 41. doi:10.1017/S1047951122000117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014; 12( 12): 1495– 9. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alshumrani GA . High prevalence of anatomical variations and anomalies of the coronary arteries detected by CT angiography in symptomatic patients. Congenit Heart Dis. 2024; 19( 2): 197– 206. doi:10.32604/chd.2024.049401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nguyen UH , Nguyen TLT , Kotani Y , Nguyen MT , Mai DD , Nguyen VAT , et al. Doubly committed ventricular septal defect: is it safe to perform surgical closure through the pulmonary trunk approached by right vertical axillary thoracotomy? JTCVS Open. 2023; 15: 368– 73. doi:10.1016/j.xjon.2023.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jegatheeswaran A , Devlin PJ , Williams WG , Brothers JA , Jacobs ML , DeCampli WM , et al. Outcomes after anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery repair: a congenital heart surgeons’ society study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020; 160( 3): 757– 71.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.01.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kohlsaat K , Gauvreau K , Beroukhim R , Newburger JW , Quinonez L , Nathan M . Trends in surgical management of anomalous aortic origin of the coronary artery over 2 decades. JTCVS Open. 2023; 16: 757– 70. doi:10.1016/j.xjon.2023.07.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sachdeva S , Frommelt MA , Mitchell ME , Tweddell JS , Frommelt PC . Surgical unroofing of intramural anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery in pediatric patients: single-center perspective. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018; 155( 4): 1760– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Balasubramanya S , Mongé MC , Eltayeb OM , Sarwark AE , Costello JM , Rigsby CK , et al. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery: symptoms do not correlate with intramural length or ostial diameter. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2017; 8( 4): 445– 52. doi:10.1177/2150135117710926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bonilla-Ramirez C , Molossi S , Sachdeva S , Reaves-O’Neal D , Masand P , Mery CM , et al. Outcomes in anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery after surgical reimplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021; 162( 4): 1191– 9. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.12.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yan L , Zhou ZC , Li HP , Lin M , Wang HT , Zhao ZW , et al. Right vertical infra-axillary mini-incision for repair of simple congenital heart defects: a matched-pair analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013; 43( 1): 136– 41. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezs280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yaliniz H , Topcuoglu MS , Gocen U , Atalay A , Keklik V , Basturk Y , et al. Comparison between minimal right vertical infra-axillary thoracotomy and standard Median sternotomy for repair of atrial septal defects. Asian J Surg. 2015; 38( 4): 199– 204. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2015.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang D , Wang Q , Yang X , Wu Q , Li Q . Mitral valve replacement through a minimal right vertical infra-axillary thoracotomy versus standard Median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009; 87( 3): 704– 8. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hong ZN , Chen Q , Lin ZW , Zhang GC , Chen LW , Zhang QL , et al. Surgical repair via submammary thoracotomy, right axillary thoracotomy and Median sternotomy for ventricular septal defects. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018; 13( 1): 47. doi:10.1186/s13019-018-0734-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lee T , Weiss AJ , Williams EE , Kiblawi F , Dong J , Nguyen KH . The right axillary incision: a potential new standard of care for selected congenital heart surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018; 30( 3): 310– 6. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2018.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dodge-Khatami A , Gil-Jaurena JM , Hörer J , Heinisch PP , Cleuziou J , Arrigoni SC , et al. Over 3,000 minimally invasive thoracotomies from the European congenital heart surgeons association for quality repairs of the most common congenital heart defects: safe and routine for selected repairs. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2025; 16( 5): 578– 84. doi:10.1177/21501351251322155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Conway BD , Bates MJ , Hanfland RA , Yerkes NS , Patel SS , Calcaterra D , et al. A minimally invasive, algorithm-based approach for anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Innovations. 2015; 10( 2): 101– 5. doi:10.1097/IMI.0000000000000135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Stephens EH , Jegatheeswaran A , Brothers JA , Ghobrial J , Karamlou T , Francois CJ , et al. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024; 117( 6): 1074– 86. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools