Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Novel Optimized Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Efficient Seizure Stage Classification

1 Department of Biomedical Engineering, KIT-Kalaignarkarunanidhi Institute of Technology, Coimbatore, 641402, India

2 Department of Computer Sciences and Engineering, Vel Tech Rangarajan Dr. Sagunthala R&D Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, 600062, India

3 Department of Computer Sciences and Engineering, College of Applied Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11543, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Computer Engineering, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11543, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Mount Zion College of Engineering and Technology, Pudukkottai, 622507, India

* Corresponding Authors: Umapathi Krishnamoorthy. Email: ; Abdulaziz S. Almazyad. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 3903-3926. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.055910

Received 10 July 2024; Accepted 11 October 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Brain signal analysis from electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings is the gold standard for diagnosing various neural disorders especially epileptic seizure. Seizure signals are highly chaotic compared to normal brain signals and thus can be identified from EEG recordings. In the current seizure detection and classification landscape, most models primarily focus on binary classification—distinguishing between seizure and non-seizure states. While effective for basic detection, these models fail to address the nuanced stages of seizures and the intervals between them. Accurate identification of per-seizure or interictal stages and the timing between seizures is crucial for an effective seizure alert system. This granularity is essential for improving patient-specific interventions and developing proactive seizure management strategies. This study addresses this gap by proposing a novel AI-based approach for seizure stage classification using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN). The developed model goes beyond traditional binary classification by categorizing EEG recordings into three distinct classes, thus providing a more detailed analysis of seizure stages. To enhance the model’s performance, we have optimized the DCNN using two advanced techniques: the Stochastic Gradient Algorithm (SGA) and the evolutionary Genetic Algorithm (GA). These optimization strategies are designed to fine-tune the model’s accuracy and robustness. Moreover, k-fold cross-validation ensures the model’s reliability and generalizability across different data sets. Trained and validated on the Bonn EEG data sets, the proposed optimized DCNN model achieved a test accuracy of 93.2%, demonstrating its ability to accurately classify EEG signals. In summary, the key advancement of the present research lies in addressing the limitations of existing models by providing a more detailed seizure classification system, thus potentially enhancing the effectiveness of real-time seizure prediction and management systems in clinical settings. With its inherent classification performance, the proposed approach represents a significant step forward in improving patient outcomes through advanced AI techniques.Keywords

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder marked by recurrent seizures due to sudden electrical discharges in the cerebral cortex. Seizures can range from minor muscle twitches to severe, life-threatening events. Diagnosis typically involves tools such as electroencephalogram (EEG), stereoelectoencephalograpy (SEEG), computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), with EEG being the most cost-effective and accessible for monitoring brain activity. Conventionally, epilepsy is diagnosed from EEG analysis, and antiseizure medication is prescribed for epilepsy patients [1,2]. Despite its advantages, traditional EEG-based seizure detection has limitations due to the need for prolonged recording periods, making it a challenge to capture infrequent seizure events, mainly if they occur irregularly or the patient delays seeking medical attention. Prolonged medicine intake-induced resistance and discomfort-induced medication discontinuation are additional hurdles [3]. The limitations of conventional methods underscore the importance of seizure prediction and management advancements. Recent developments in miniaturized medical devices and artificial intelligence have significantly enhanced the ability to understand and predict seizures on a patient-specific level. By analyzing patterns in EEG signals, these technologies enable the early prediction of seizures, which have profound clinical implications. The ability to predict seizures in real-time offers several critical benefits, which include (i) Preemptive Alerts: Early prediction allows for the development of warning systems that can alert patients and caregivers before a seizure occurs, providing time to take preventive measures, (ii) Personalized Neurostimulation: Advanced systems can trigger neurostimulation devices that deliver medication or other therapeutic interventions precisely when needed, potentially reducing the frequency and severity of seizures, (iii) Reduced Medication Side Effects: By optimizing treatment timing and dosage through real-time monitoring, patients may experience fewer side effects and a lower risk of developing medication resistance. Integrating real-time seizure prediction and monitoring systems can significantly improve patient outcomes by enhancing seizure management, reducing treatment-related discomfort, and potentially saving lives [4].

Electroencephalograms (EEGs) play a crucial role in diagnosing and monitoring neurological disorders such as epilepsy and parasomnias. One of the primary challenges in clinical settings is differentiating between epileptic seizures and non-epileptic events. Epileptic seizures are paroxysmal and involve hypersynchronous neuronal firing, leading to specific EEG patterns, whereas non-epileptic events, such as syncope, benign sleep movements, parasomnias, breath-holding spells (BHS), Pallid BHS, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES), Gastroesophageal reflux and alternating hemiplegia [5,6]. These non-epileptic seizure events are identified as wicket spikes, benign epileptiform transients of sleep, 6 Hz “phantom” spike-and-wave complex (PhSW), rhythmic mid-temporal theta of drowsiness, positive occipital sharp transients of sleep, subclinical rhythmic EEG discharge in adults, 14 and 6 Hz positive spikes, repetitive vertex waves, breach rhythm in the EEG waveform [7]. Thus, a well-annotated dataset could aid in efficiently distinguishing the various epileptic events from non-epileptic seizure events. Distinguishing these accurately is essential for appropriate treatment. For instance, a model with high classification accuracy can significantly improve diagnostic precision by accurately identifying epileptic seizures amidst various non-epileptic events. Consider a scenario where a patient presents episodes of altered consciousness. An accurate AI-powered model could analyze the EEG data and differentiate between epileptic seizures and benign events like breath-holding spells (BHS) [8,9]. This capability reduces the likelihood of misdiagnosis and ensures that the patient receives the correct intervention, optimizing therapeutic outcomes. This distinction is crucial for initiating timely and appropriate treatment for epilepsy, such as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) or surgical interventions [9]. Conversely, misidentification can lead to inappropriate treatments, exacerbating patient conditions, or delaying necessary care.

Furthermore, integrating AI models with patient metadata enhances the context in which EEG data is interpreted, providing a comprehensive view that can lead to better clinical decisions. Accurate models enable clinicians to make informed decisions, improve treatment efficacy, and reduce the burden of unnecessary interventions. In summary, the accuracy of EEG-based models is vital for precise diagnosis and effective patient management, directly impacting treatment outcomes and overall patient care.

An EEG recording of a seizure event is characterized by four phases: preictal, ictal, postictal, and interictal. Each phase has distinct characteristics essential for differentiating between normal and seizure states.

• Ictal Phase: This is the phase where the actual seizure activity occurs. It is characterized by abnormal high-frequency discharges, manifesting as numerous fast EEG spikes. This activity is markedly different from regular brain activity.

• Postictal Phase: Following the ictal phase, the postictal phase involves a return to normal brain activity. However, as the brain recovers from the seizure, it may exhibit transient abnormalities.

• Preictal Phase: This phase precedes a seizure and is characterized by subtle changes in the EEG that may indicate an impending seizure. These changes can include increased spikes or slow-wave activity.

• Interictal Phase: The period between seizures is termed interictal. During this phase, EEG recordings often show some degree of abnormality, such as interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs), which can help in predicting future seizures.

However, capturing IED activity necessitates studying a vast range of EEG recordings from a patient. IED frequency of 60% to 90% is recorded in epilepsy patients and 12% in patients with other cerebral disorders, and it is in the range of 0.5% to 2.5% in the case of healthy individuals [10]. Studies reveal that in about 57% of localized epileptic seizure cases, an ictal onset with increased frequency is observed. To gain knowledge about IED in patients and strengthen epilepsy diagnosis, various activation methods like photic stimulation, hyperventilation, and sleep deprivation are used while recording EEGs [11,12]. Though seizure events are highly irregular, precise analysis of EEG to understand the similarity between seizure events and discriminating the seizure phases aid in predicting seizure events 10 to 20 min before their onset. This is the objective behind seizure warning devices. Primarily, EEG signals are studied by two different methods (i) direct analysis of EEG data or (ii) using surrogate data analysis to study the non-linear behavior of EEG signals to understand their inherent patterns [13,14].

Artificial intelligence techniques rely on learning from examples and thus are valuable tools in predicting and forecasting outcomes by mapping the present input conditions with their learned knowledge. Deep learning architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have shown promising results in learning inherent patterns from images. In contrast, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) excel in learning time series data [15,16]. Such tools, when made to learn EEG recording, could acquire knowledge about the patterns associated with the different phases of a seizure and enable predicting a seizure early [17]. Though started with automating the diagnosis of a seizure event, state-of-the-art seizure prediction tools could classify EEG recordings into different seizure phases, say preictal, ictal, and normal, and use them for predicting a seizure onset [18,19]. Such systems could alert patients about a seizure onset and, if integrated with electrical stimulation or drug delivery systems, could control seizures effectively. Being introduced to the effects of epileptic seizure, the importance of an early prediction and the capabilities of AI tools in seizure management, this paper presents the results of a seizure classification and prediction model developed leveraging the benefits of deep learning. The objective of the study is:

• To conduct an exhaustive literature review of the recent research in EEG signal studies for anomaly prediction and seizure classification.

• To propose a novel methodology utilizing Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) coupled with an efficient optimization followed by k-fold cross-validation for effectively identifying EEG features while optimizing classification performance. The efficiency of stochastic gradient-based optimization and evolutionary algorithm-based GA are studied to compare convergence and prediction accuracy, and model robustness to new inputs is ensured by k-fold cross-validation.

• To test and validate the proposed methodology on performance metrics like accuracy, precision, recall AUC, and loss.

• To compare the proposed methodology with existing techniques, such as multi-layer perceptron (MLP) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) techniques.

The article starts with a brief introduction to epileptic seizures in Section 1, followed by a review of related works in Section 2. Section 3 discusses the input dataset, and the methods used for the experiment. Section 4 details the proposed DCNN architecture, the two-level optimization, and the algorithm. The results obtained from the experiment are presented in Section 5, and the conclusion is presented in Section 6.

Classification of seizures and the ability to detect them are areas that are still under investigation in epilepsy. Proper identification will go a long way toward improving patient management. Due to the challenges that arise from these approaches, several studies have used diverse strategies to analyze EEG signals. This paper discusses previous research in this field, how past works interpret them, and how our proposed method fills the gap.

In addition, Shoka et al. [5] discussed significant concepts and techniques of EEG seizure detection and challenges, highlighting the need to enhance the classifier performance, considering the impact of noise and data variability. Their work involved data preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification based on machine learning techniques for classification. Still, it was challenged by issues of time and accuracy in classifying samples. Although they achieved improved detection rates, their work highlights a recurring problem in existing methods, a few of which are in areas that may cause difficulties in the management of noise and variability of signals to accurate the seizure classification in EEG. On a similar note, Ramakrishnan et al. [6] studied localization-related epilepsies based on EEG records regarding patterns and seizure semiology. Thus, although their studies enhanced assessment abilities, they were limited by small numbers of cases and variability in patient conditions. Such limitations indicate that findings may not be generalizable. This remains a gap in literature in terms of extensibility and strength.

Furthermore, Foldvary et al. [7] examined ictal EEG in focal epilepsy; 486 recordings were studied to determine localization efficacy. They obtained 72% localization accuracy but pointed to possible misinterpretations, such as occipital and parietal seizures. This indicates that achieving high accuracy across the different SE types remains a fond dream, an area where our proposed method seeks to fill the void through improved deep-learning methodologies. Similarly, Jaishankar et al. [10] proposed a deep learning model based on adaptive grey wolf optimization (AGWO) and auto-encoder to obtain 99% accuracy in seizure forecasting. However, the small sample they used in their studies made it difficult to decide whether the results could be generalized to other groups. Also, using the binary dragonfly algorithm and deep neural network, Yogarajan et al. obtained ninety-nine percent accuracy; however, they pointed out that the results may differ in different categories of patients [12]. Both studies concluded that there is an acute need for models that would generalize well across various populations, an area of interest for our work.

In addition, Mir et al. [16] proposed a deep convolutional autoencoder bidirectional long short memory (DCAE-Bi-LSTM) model, which recorded an accuracy level of 99.8%, but this comes with a high computational demand for real-time. Although their framework is compassionate and specific, its computational complexity can hinder practical implementation. In the case of the proposed optimized deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) method, we have considered both the high accuracy of the deep learning method and the relative slowness of the process due to the complex computations performed by the large number of neurons in the deep network in real-time applications. Furthermore, Statsenko et al. [17] also engaged the TUSZ dataset and deep learning models, where the sensitivity found was 87.7%, but they also found an issue in reduced electrode differentiation. Their work indicates that people require better interpretation capabilities when using machine learning in cases such as clinical applications. Our method is designed to improve interpretability while keeping classification accuracy high—a gap that the current literature lacks. Furthermore, Pontes et al. [20] discussed the idea of drifts in the seizure prediction performance in the machine learning algorithm. They observed that performance discrepancies occurred among patients. Consequently, their work indicates the need for models tailored to the patients and their variability. Likely, similar to the work of Costa et al. [21], patient-specific algorithms could be a solution. Still, several problems arise from the increased algorithmic density [22,23]. This strategy focuses on user-friendliness and flexibility regarding patient-specific information, a singular development in the clinical domain. Further, Ibrahim et al. [24] used multiresolution CNNs but pointed out that generalization is difficult for individual patient disparity. It is clear from their work that dealing with a wide range of seizures requires building relatively more complex models to design. Our proposed DCNN method directly addresses this problem by using an optimal structure that boosts the feature extraction, thereby generalizing other datasets.

Therefore, it can be concluded that although there have been improvements in the classification of EEG seizures in prior studies, there are still some limitations, including generalization, real-time implementation, and interpretability. These issues are evident in the current studies. They motivate our novel optimized deep convolutional neural network that will give a better, more efficient, and more understandable method for the identification of the stage of seizures. In addition to increasing classification accuracy, our approach also broadens feature extraction and the model’s applicability to various patient sets, making our work a significant development in epilepsy care. List of past references, including dataset, methodology, limitations, and results are presented in Table 1.

Bonn Dataset: The Bonn time series dataset was first analyzed in [25] and is downloaded from [26], and they are used to train and test the proposed DCNN model. Bonn dataset used for the experiment is a collection of time series EEG data obtained from patients under five different conditions. Set ‘Z’ and ‘O’ are obtained from healthy individuals awake and relaxed with eyes open (Z) and closed (O). Thus, both ‘Z’ and ‘O’ hold EEG data under “Normal” conditions. Set ‘F’ and ‘N’ are obtained from the epileptogenic zone and opposite hemisphere of epilepsy patient volunteers, respectively, under a seizure-free state. Thus, ‘N’ and ‘F’ constitute the “Pre-seizure” condition. Whereas set ‘S’ is obtained from Epilepsy patients under “Seizure” activity. Each of them has 100 EEG segments of 23.6 s. Each EEG sample was recorded using the same 128-channel EEG amplifier system. After artifact removal, the recordings were converted using 12-bit ADC and sampled at a rate of 173.61 Hz, resulting in 4096 samples for each EEG segment.

Summary of the Bonn time series dataset used for training the model is given in Table 2.

The Bonn dataset contains EEG time series data stored in individual text files in five folders: Z, N, O, F, and S. Each ‘.txt’ file has 4096 samples. The data samples are converted to a comma-delimited format and stored in a ‘.csv’ file with their class labels for processing. A min-max scaler is used to ensure a value range of 0 to 1, and the data is reshaped to a sequence with a length of 512. Samples of EEG images reconstructed from time series are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Samples from EEG inputs (a) normal state and (b) seizure state

EEG samples labeled Z and O are grouped and labeled as “Normal,” class samples labeled N and F are grouped under the label “Interictal,” and S is labeled as “Ictal” to train the DCNN model for the classification task. The input dataset is partitioned into 70%, 15%, and 15% for training, validation, and testing phases. The dataset used for learning has an inherent imbalance with fewer samples under the “seizure” class. This imbalance may drive the model to be biased towards the other classes. Thus, class weights are assigned inverse proportion to the number of samples in each class to address this imbalance.

New Delhi Dataset: The New Delhi dataset, detailed in Reference [27], was acquired from the Neurology & Sleep Centre, Hauz Khas, New Delhi, and used for training and testing the model. This dataset contains pre-processed and segmented EEG samples under ictal, preictal, and interictal states obtained from 10 epilepsy patients at Neurology & Sleep Centre, Hauz Khas, New Delhi. EEG signals were recorded at 200 Hz using a standard EEG acquisition system and filtered to obtain signals between 0.5 and 70 Hz. These recordings are stored as MAT files, and each MAT file has 1024 samples representing one EEG time series for 5.12 s. The MAT files are converted to “.csv” for training and testing the proposed model.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) mimic the visual perception of biological systems where simple cells extract features from small visual sub-fields and complex cells strive to combine features from spatial neighborhoods. CNN can extract features from the inputs by performing convolution of the kernel over the input matrix [28,29]. Each convolution layer has ‘n’ kernels (relatively smaller than input) of a fixed size, which performs convolution over the input matrix and results in n-feature maps. These feature maps are down-sampled in the consequent step to extract the most significant features alone. Each of these CNN layers is realized by an arrangement of neurons with initial weights and biases. As the network learns features from input and makes predictions, the prediction error is computed, and the network weights and biases are updated after each training epoch. Thus, prediction accuracy and faster convergence depend on how efficiently weights are updated. Therefore, optimizing weights during backpropagation is beneficial and is used exhaustively in this study. Fig. 2 depicts the structure of a generic CNN architecture.

Figure 2: Convolutional neural network model

Features extracted by convolution layer are down-sampled in order to select the most significant features from the feature map. Such a selection is carried out by pooling layer by selecting the maximum value or average of all pixels in the sub-field. Sub-fields are non-overlapping regions in the feature map and the pooling kernel window fixes their size. Batch normalization helps improve learning performance by providing a normalized output based on the current inputs mean and standard deviation. Flattening converts the output retrieved after the desired number of convolutions and pooling into a 1D array for being fed to the next classification layer. Flattened data is connected fully to the output SoftMax layer and classified in to the desired number of classes.

3.3 Optimized Learning and Robust Validation

Optimized model development demands tuning the model parameters and learning parameters by an appropriate optimization algorithm based on the loss function. Weight optimization with robust validation paves way for harvesting excellent outcomes from the model. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is the most frequently used optimizer for parameter tuning when the training dataset is huge. It calculates the model parameters from small batches of dataset instead of the whole. The parameter update function is given by Eq. (1).

Here,

Here,

4 Proposed DCNN Seizure Classification Framework

Automatic identification of seizures and classification of seizure states play a significant role in developing automatic seizure prediction and alerting systems. Thus, this research seeks to classify seizure stages into three classes, say normal, interictal, and ictal, by using a DCNN model [30,31]. The developed framework is based on a reduced complexity end-to-end CNN model that could automatically learn the features from EEG time series data and classify the seizure stages. The framework achieves faster convergence by adapting stochastic gradient-based/GA-based weight and bias updates and ensures prediction accuracy using a robust validation technique. The model is trained from the time series EEG recordings obtained from normal as well as epileptic subjects to provide efficient learning of seizure features and surpasses current methods in terms of accuracy, FPR, and sensitivity [32]. The search for the efficient model is extended beyond parameter tuning to study the training hyperparameter. Validation aids in evaluating the model against new data and returning the model learning parameters if needed. Robust validation ensures excellent classification efficiency with reduced complexity. Numerous validation methods are available based on optimized search algorithms: random search, grid search, and evolutionary search. In this experiment, a k-fold cross-validation technique is adapted to retrieve the best model. The entire research pipeline is shown below in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Workflow of proposed end-to-end DCNN model

4.1 Fast Converging DCNN Learning Model

Automating the seizure prediction task starts with identifying different seizure stages, say normal, ictal, and interictal, and thus, an end-to-end deep convolutional neural network model capable of learning the seizure features from EEG time series recordings is presented in this study. The DCNN model used for classification uses six-level deep 1D convolutional layers followed by three-level dense layers after flattening. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation introduces non-linearity in neural network [33]. Such non-linearity helps in overcoming the vanishing gradient problem with model training. ReLU relays all its positive inputs while making negative inputs zero. ReLU alters the values alone, and the size of the feature map remains unchanged. Batch normalization is carried out after each convolution to standardize the outputs and increase the generalization. The proposed DCNN architecture is given in Fig. 4 and its constituent layers are presented in Table 3.

Figure 4: DCNN architecture

4.2 Level-1 Model Optimization

Tuning model parameters, say weights and biases based on loss function by an appropriate algorithm, helps in faster model convergence. Two different optimization techniques based on stochastic gradient and evolutionary optimization are used for optimized learning, and the best optimizer that makes the model converge faster is chosen for the final testing [34,35]. Adam optimizer, a stochastic gradient method that uses first and second-order moments to update the network parameters, says weights and biases in each layer are chosen for parameter optimization. Reduced error rates ensure smooth model convergence [36,37]. Algorithm 1 depicts the stochastic gradient based Adam algorithm used for parameter tuning.

Genetic Algorithm (GA): Genetic algorithm is a heuristic optimization technique based on the principle of evolution of offsprings [37,38]. GA based optimizations could achieve excellent results. GA-based parameter tuning assigns the weights and bias (chromosomes) to be tuned to a fitness score. The parameter undergoes mutation and crossover to obtain the fittest value for them. GA based tuning could achieve best performing models as it decides the fittest offspring based on model accuracy. Both optimization techniques were adapted individually for tuning the DCNN model for seizure prediction from EEG signals and their efficiency is verified in this experiment. Genetic Algorithm pseudocode used for model optimization is given by Algorithm 2.

4.3 Level-2 Model Optimization

Validation helps in evaluating a model’s performance against new inputs. k-fold cross-validation is used in this experiment to retrieve the best model hyperparameter. Validation data is partitioned into a validation train and a validation test to train and test the model in the validation phase. This evaluation is done k-times over the Mean Square Error (MSE) value and tested with validation test data. The hyperparameters are tuned and updated for improved model performance, and if desired, the model is retrained using the updated parameters. Pseudocode for cross-validation (CV) algorithm is given by Algorithm 3.

Pseudocode for the two-level optimized DCNN algorithm used for classifying seizure stages is given by Algorithm 4.

The proposed DCNN model is developed in Python using Keras DL API in the Tensorflow library. The model is built in the Google Collab laboratory in Google’s data centers. The developed model is trained and tested using the Bonn EEG and New Delhi datasets. The proposed model is trained and tested using the Bonn EEG and New Delhi datasets. The Bonn EEG dataset includes seizure time series data obtained using intracranial electrodes from epilepsy patients and healthy volunteers. The dataset was pre-processed, and time series data were initially available as text files converted to .csv format for use in the model. To streamline the classification process, the original five classes are consolidated into three: “Normal” (Z and O classes from healthy volunteers), “Interictal” (N and F classes from seizure-free epilepsy patients), and “Seizure” (S class from seizure events). This reclassification introduced some class imbalance, addressed through class-weighted learning, which assigns weights inversely proportional to the sample size in each class to mitigate prediction bias. The second dataset, the New Delhi dataset, has 1024 data points representing each EEG segment, and the proposed model is used to classify these samples into ictal, pre-ictal, and interictal states, and the results are verified to ensure model performance.

The proposed model uses a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) tailored for time-series EEG data from the Bonn dataset. The network architecture consists of six 1D convolutional layers with 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024 filters, each having kernel sizes of 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, and 7, respectively, and strides of 2. These layers utilize ReLU activation functions, while batch normalization is applied after each convolutional layer to mitigate overfitting and enhance model generalization. Following the convolutional layers, the feature maps are flattened and passed through three dense layers with dropout regularization, culminating in a Softmax output layer that classifies the data into three categories: Normal, Interictal, and Seizure.

The dataset is partitioned into 85% for training and 15% for testing, applying a class-weighted learning approach to address class imbalance. A batch size of 64 is used and the model is trained for 30 epochs. The training process employed stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with the Adam optimizer and a genetic algorithm-based optimizer, with initial learning rates of 0.0001. The Adam optimizer achieved an accuracy of 90%, while the genetic algorithm-based optimizer improved this to 92%. Following k-fold cross-validation and evaluation on unseen data, the model was re-trained with the genetic algorithm at a learning rate of 0.001, achieving a final accuracy of 93% in classifying seizure stages. Fig. 5 presents the sample outputs from classification by the proposed method. Fig. 5a,b represents output samples of the Bonn dataset, whereas Fig. 5c,d represents output samples from the New Delhi dataset where the x-axis specifies the sequence of samples, and the y-axis represents EEG signal amplitude in microvolts.

Figure 5: Sample classification results. (a) & (b) Bonn dataset. (c) & (d) New Delhi dataset

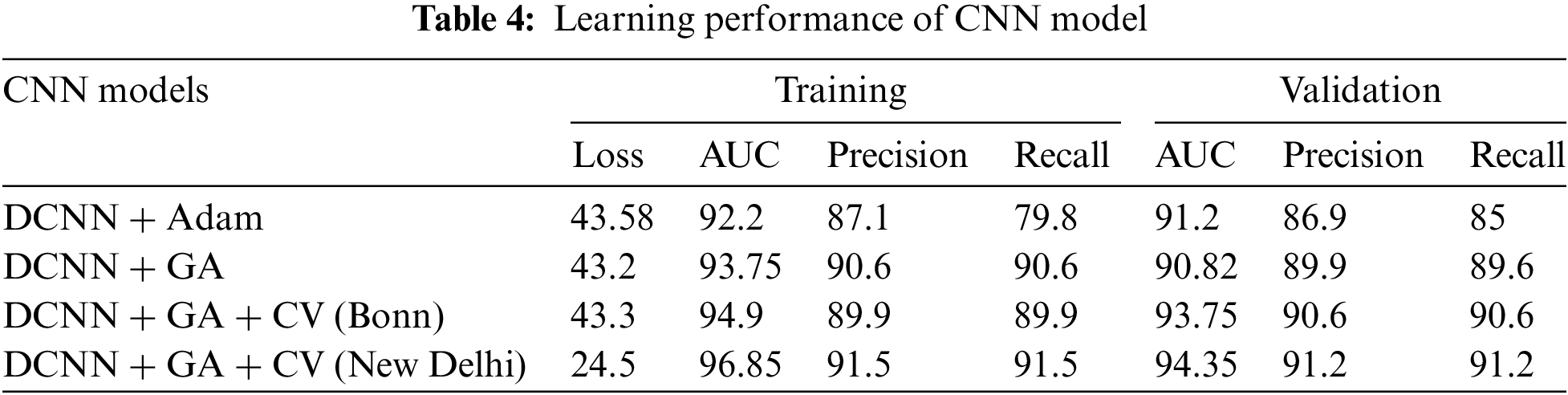

This study compared the results achieved with a DCNN model in classifying EEG signals into three classes with three different optimizations, say (i) DCNN + Adam optimization, (ii) DCNN + GA, and (iii) DCNN + GA + CV. The variation in loss, accuracy, precision, and recall obtained from the training and validation phases of the three variants are shown in Table 4.

The results indicate a performance improvement when applying the Genetic Algorithm (GA) with cross-validation (CV) on the New Delhi dataset compared to the Bonn dataset. Specifically, the model achieved an AUC of 96.85 and 94.35 for training and validation on the New Delhi dataset, outperforming the Bonn dataset results. The performance of the proposed DCNN model is compared with SVM and MLP models in order to study its classification efficiency. It is found that the proposed end-to-end DCNN model tuned by genetic algorithm and k-fold cross-validation could achieve better classification accuracy as compared to MLP and SVM classifiers. The proposed model’s efficiency compared to SVM and MLP is summarized in Table 5. Proposed CNN performs better across the assessment indices.

5.1 Why Our Algorithms Are Selected over Others

Our approach integrates Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN) with Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Cross-Validation (CV) techniques, specifically using two distinct datasets: Bonn and New Delhi. The selection of the method called DCNN is explained by the fact that this approach works well for the classifying tasks involved in analyzing images, as it can identify the necessary features from the raw data by itself. GA improves this by the operations of hyperparameters and feature selection, which ultimately greatly impacts the model. We provide an extensive evaluation of our model to other recognized classifiers, such as MLP, SVM, and the basic structures of the DCNN. Comparing the results of the proposed method with those of the other approaches proves that our hybrid model obtains higher accuracy and is also quite stable under different conditions.

This section has been enriched with the specification of the reasons behind our algorithm choices. For instance, we also illustrate that MLP and SVM are prone to overfitting in high-dimensional data. However, our hybrid model avoids such problems by relying on the optimization properties of GA and, hence, provides a more generalized performance. Further, we explain how the incorporation of CV confirms the model’s effectiveness by preventing information leakage and excluding unfair top performances.

Altogether, the application of DCNN, GA, and CV in the present study can be considered a shift in classification approaches in the given scenario. We think that such detailed justification helps to explain the novelty and significance of the proposed approach as it enables the creation of a classifier of higher quality compared to existing classifiers, thus improving the quality and relevance of our investigation.

Further, classification accuracy represents the percentage of correct predictions made by the classifier over all predictions made. Eqs. (3) and (4) give accuracy. Fig. 6 represents the accuracy of classification obtained with different models. The graph clearly reveals that a two-fold optimization could improve the model’s accuracy.

Figure 6: Accuracy obtained for different models

Precision is a metric that represents the number of correct positive classifications made by the model against the total positive classification. Precision is given by the Eqs. (5) and (6). Fig. 7 represents the precision of different models in classifying EEG signals.

Figure 7: Precision obtained with different classification models

Recall represents the number of correct positive predictions made by the model against actual positive classes. The formula for recall is given by Eqs. (7) and (8). Recall of different models in classifying EEG signals is given in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Recall of different models

The Area Under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) Curve (AUC) signifies the area under the ROC curve. It specifies the model’s performance irrespective of the classification threshold. Fig. 9 shows the AUC obtained for various models in performing the EEG classification task.

Figure 9: AUC comparison for EEG classification task

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed model against several existing methods. In the context of the classification techniques for epilepsy detection, our proposed method achieves high efficiency compared to other works in the Bonn and New Delhi datasets. When comparing different models, it is used not only for accuracy but also recall or sensitivity and specificity, thus giving a somewhat more comprehensive picture of the model’s efficacy. As for the accuracy metrics, our proposed method obtains the accuracy of 93.2% on the Bonn dataset and 92.0% on the New Delhi dataset. Smaller models, like the LS-SVM, get an accuracy of 99.5% on the Bonn dataset, and here again, it is essential to remember that accuracy is not always a trustworthy measure, especially in highly imbalanced data. However, considering the proposed method, its performance is rather suitable, considering its ability to work with several datasets.

Concerning recall, the method we presented attains a sensitivity of 90.0% for the Bonn dataset and 90% for the New Delhi dataset. This is especially so when compared with standard models such as the LS-SVM with a recall of 100%. However, such high sensitivity should be understood in light of the trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity. The proposed technique yields a specificity of 93.0% on the New Delhi dataset, indicating a suitable trade-off between true and false results. This factor is essential in practical applications. ADAM and MLP have very high accuracy, but some do not always report sensitivity or specificity, making evaluating the models’ applicability disputable. For example, although the MLP has boasted a 99.83% accuracy rate, it does not state recall information. As for the SVM and CNN models, the accuracy scores are not bad. However, the variance in the model’s performance between different data sets is rather notable. In addition, the proposed method outperforms competitors regarding average proximity for various datasets. A particular model may perform well on one dataset. Still, our approach seems reliable across the datasets, suggesting that it may be better suited to real-world scenarios where variability in data is usual.

Therefore, while some of the existing approaches may demonstrate higher accuracy numbers, the proposed method is quite unique in that it simultaneously offers relatively high values of sensitivity and specificity. This makes it a laudable contribution to the diagnosis of epilepsy and a useful resource for clinicians who seek to enhance their diagnostic precision to influence the treatment plan and prognosis of epilepsy patients.

An end-to-end light-weight deep CNN model is developed to effectively classify seizure stages into ictal, interictal, and normal stages using EEG time series data. The proposed DCNN with genetic algorithm-based optimization and cross-validation-based tuning converges faster and achieves a good classification accuracy of 93.2%. Faster convergence of the model is attributed to the parameter optimization by evolutionary algorithm GA, and classification accuracy is achieved by robust k-fold cross-validation.

A primary advantage of the proposed model is that it is lightweight and can achieve excellent prediction accuracy. Despite these strengths, the dataset’s fixed length and limited variability pose challenges, particularly in capturing pre-seizure periods that vary among patients.

With its efficient classification accuracy, the model will be enhanced by (i) training the model with diverse datasets for classifying different seizure variants, (ii) modified to learn the interictal lengths, and (iii) integrated with patient metadata to make it a one-step tool for diagnosing seizure and integrating it into clinical practices.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University for funding this research through the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R809), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: The research is funded by the Researchers Supporting Program at King Saud University (RSPD2024R809).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Umapathi Krishnamoorthy; Data curation, Shanmugam Jagan; Formal analysis, Mohammed Zakariah and Abdulaziz S. Almazyad; Investigation, Mohammed Zakariah and Abdulaziz S. Almazyad; Methodology, K. Gurunathan; Writing—original draft, Umapathi Krishnamoorthy; Writing—review & editing, Umapathi Krishnamoorthy. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. D. Lee et al., “A ResNet-LSTM hybrid model for predicting epileptic seizures using a pretrained model with supervised contrastive learning,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 2024, Art. no. 1319. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43328-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. A. Leibetseder, M. Eisermann, W. C. LaFrance, L. Nobili, and T. J. von Oertzen, “How to distinguish seizures from non-epileptic manifestations,” Epileptic Disord., vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 716–738, Dec. 2020. doi: 10.1684/epd.2020.1234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. X. Wang, Y. Zhao, and F. Pourpanah, “Recent advances in deep learning,” Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 747–750, Apr. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s13042-020-01096-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. K. Rasheed et al., “Machine learning for predicting epileptic seizures using EEG signals: A review,” IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng., vol. 14, pp. 139–155, 2021. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2020.3008792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. A. A. Ein Shoka, M. M. Dessouky, A. El-Sayed, and E. E. -D. Hemdan, “EEG seizure detection: Concepts, techniques, challenges, and future trends,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 82, no. 27, pp. 42021–42051, Nov. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11042-023-15052-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. S. Ramakrishnan, R. Asuncion, and A. Rayi, “Localization-related epilepsies on EEG,” 2024. Accessed: Aug. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557645/ [Google Scholar]

7. N. Foldvary, G. Klem, J. Hammel, W. Bingaman, I. Najm and H. Lüders, “The localizing value of ictal EEG in focal epilepsy,” Neurology, vol. 57, no. 11, pp. 2022–2028, Dec. 2001. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.11.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. U. R. Acharya, S. Vinitha Sree, G. Swapna, R. J. Martis, and J. S. Suri, “Automated EEG analysis of epilepsy: A review,” Knowl. Based Syst., vol. 45, pp. 147–165, Jun. 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2013.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Y. Song, J. Crowcroft, and J. Zhang, “Automatic epileptic seizure detection in EEGs based on optimized sample entropy and extreme learning machine,” J. Neurosci Methods, vol. 210, no. 2, pp. 132–146, Sep. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. B. Jaishankar, A. M. Ashwini, D. Vidyabharathi, and L. Raja, “A novel epilepsy seizure prediction model using deep learning and classification,” Healthc. Anal., vol. 4, Dec. 2023, Art. no. 100222. doi: 10.1016/j.health.2023.100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. B. Nanthini and B. Santhi, “Electroencephalogram signal classification for automated epileptic seizure detection using genetic algorithm,” J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med., vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, Art. no. 159. doi: 10.4103/jnsbm.JNSBM_285_16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. G. Yogarajan et al., “EEG-based epileptic seizure detection using binary dragonfly algorithm and deep neural network,” Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, Oct. 2023, Art. no. 17710. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44318-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. G. Chen, W. Xie, T. D. Bui, and A. Krzyżak, “Automatic epileptic seizure detection in EEG using nonsubsampled wavelet-fourier features,” J. Med. Biol. Eng., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 123–131, Feb. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s40846-016-0214-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. K. Samiee, P. Kovacs, and M. Gabbouj, “Epileptic seizure classification of EEG time-series using rational discrete short-time fourier transform,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 541–552, Feb. 2015. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2360101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. N. D. Truong et al., “Convolutional neural networks for seizure prediction using intracranial and scalp electroencephalogram,” Neural Netw., vol. 105, pp. 104–111, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2018.04.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. W. A. Mir, M. Anjum, I. Izharuddin, and S. Shahab, “Deep-EEG: An optimized and robust framework and method for EEG-based diagnosis of epileptic seizure,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 4, Feb. 2023, Art. no. 773. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13040773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Y. Statsenko et al., “Automatic detection and classification of epileptic seizures from EEG data: Finding optimal acquisition settings and testing interpretable machine learning approach,” Biomedicines, vol. 11, no. 9, Aug. 2023, Art. no. 2370. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11092370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. A. K. Jaiswal and H. Banka, “Local pattern transformation based feature extraction techniques for classification of epileptic EEG signals,” Biomed. Signal Process. Control, vol. 34, pp. 81–92, Apr. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2017.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. D. Wang et al., “Epileptic seizure detection in long-term EEG recordings by using wavelet-based directed transfer function,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 65, no. 11, pp. 2591–2599, Nov. 2018. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2018.2809798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. E. D. Pontes, M. Pinto, F. Lopes, and C. Teixeira, “Concept-drifts adaptation for machine learning EEG epilepsy seizure prediction,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, Apr. 2024, Art. no. 8204. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-57744-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. G. Costa, C. Teixeira, and M. F. Pinto, “Comparison between epileptic seizure prediction and forecasting based on machine learning,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, Mar. 2024, Art. no. 5653. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-56019-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. S. Raghu, N. Sriraam, A. S. Hegde, and P. L. Kubben, “A novel approach for classification of epileptic seizures using matrix determinant,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 127, pp. 323–341, Aug. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. U. Orhan, M. Hekim, and M. Ozer, “EEG signals classification using the K-means clustering and a multilayer perceptron neural network model,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 38, no. 10, pp. 13475–13481, Sep. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.04.149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. A. K. Ibrahim, H. Zhuang, E. Tognoli, A. Muhamed Ali, and N. Erdol, “Epileptic seizure prediction based on multiresolution convolutional neural networks,” Front. Signal Process., vol. 3, May 2023, Art. no. 1175305. doi: 10.3389/frsip.2023.1175305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. R. G. Andrzejak, K. Lehnertz, F. Mormann, C. Rieke, P. David and C. E. Elger, “Indications of nonlinear deterministic and finite-dimensional structures in time series of brain electrical activity: Dependence on recording region and brain state,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 64, no. 6, Nov. 2001, Art. no. 061907. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.061907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. R. G. Andrzejak, K. Lehnertz, F. Mormann, C. Rieke, P. David and C. E. Elger, The Bonn EEG Time Series, 2001. Accessed: Mar. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.upf.edu/web/ntsa/downloads/-/asset_publisher/xvT6E4pczrBw/content/2001-indications-of-nonlinear-deterministic-and-finite-dimensional-structures-in-time-series-of-brain-electrical-activity-dependence-on-recording-regi [Google Scholar]

27. P. Swami, B. Panigrahi, S. Nara, M. Bhatia, and T. Gandhi, “EEG epilepsy datasets,” 2016. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.14280.32006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. M. Mursalin, Y. Zhang, Y. Chen, and N. V. Chawla, “Automated epileptic seizure detection using improved correlation-based feature selection with random forest classifier,” Neurocomputing, vol. 241, pp. 204–214, Jun. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2017.02.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. A. Subasi, J. Kevric, and M. Abdullah Canbaz, “Epileptic seizure detection using hybrid machine learning methods,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 317–325, Jan. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00521-017-3003-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. X. Wang, G. Gong, N. Li, and S. Qiu, “Detection analysis of epileptic EEG using a novel random forest model combined with grid search optimization,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., vol. 13, Feb. 2019, Art. no. 52. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. M. Sadiq, M. N. Kadhim, D. Al-Shammary, and M. Milanova, “Novel EEG classification based on hellinger distance for seizure epilepsy detection,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 127357–127367, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3450449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Y. Li et al., “Dynamical graph neural network with attention mechanism for epilepsy detection using single channel EEG,” Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 307–326, Jan. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11517-023-02914-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. A. Aarabi and B. He, “Seizure prediction in patients with focal hippocampal epilepsy,” Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 128, no. 7, pp. 1299–1307, Jul. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.04.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. U. R. Acharya, S. L. Oh, Y. Hagiwara, J. H. Tan, and H. Adeli, “Deep convolutional neural network for the automated detection and diagnosis of seizure using EEG signals,” Comput. Biol. Med., vol. 100, pp. 270–278, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.09.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. H. Ke, D. Chen, X. Li, Y. Tang, T. Shah and R. Ranjan, “Towards brain big data classification: Epileptic EEG identification with a lightweight VGGNet on global MIC,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 14722–14733, 2018. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2810882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. W. Hu, J. Cao, X. Lai, and J. Liu, “Mean amplitude spectrum based epileptic state classification for seizure prediction using convolutional neural networks,” J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput., vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 15485–15495, Nov. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s12652-019-01220-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. R. Hussein, H. Palangi, R. K. Ward, and Z. J. Wang, “Optimized deep neural network architecture for robust detection of epileptic seizures using EEG signals,” Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 130, no. 1, pp. 25–37, Jan. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. T. Maiwald, M. Winterhalder, R. Aschenbrenner-Scheibe, H. U. Voss, A. Schulze-Bonhage and J. Timmer, “Comparison of three nonlinear seizure prediction methods by means of the seizure prediction characteristic,” Physica D, vol. 194, no. 3–4, pp. 357–368, Jul. 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.physd.2004.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. S. Chen, X. Zhang, L. Chen, and Z. Yang, “Automatic diagnosis of epileptic seizure in electroencephalography signals using nonlinear dynamics features,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 61046–61056, May 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2915610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools