Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

UAV-Assisted Multi-Object Computing Offloading for Blockchain-Enabled Vehicle-to-Everything Systems

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 School of Computer Science, Qufu Normal University, Rizhao, 276826, China

3 School of Information Science and Technology, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100083, China

* Corresponding Author: Xin Fan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 3927-3950. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.056961

Received 03 August 2024; Accepted 18 October 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

This paper investigates an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-assisted multi-object offloading scheme for blockchain-enabled Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) systems. Due to the presence of an eavesdropper (Eve), the system’s communication links may be insecure. This paper proposes deploying an intelligent reflecting surface (IRS) on the UAV to enhance the communication performance of mobile vehicles, improve system flexibility, and alleviate eavesdropping on communication links. The links for uploading task data from vehicles to a base station (BS) are protected by IRS-assisted physical layer security (PLS). Upon receiving task data, the computing resources provided by the edge computing servers (MEC) are allocated to vehicles for task execution. Existing blockchain-based computation offloading schemes typically focus on improving network performance, such as minimizing energy consumption or latency, while neglecting the Gas fees for computation offloading and the costs required for MEC computation, leading to an imbalance between service fees and resource allocation. This paper uses a utility-oriented computation offloading scheme to balance costs and resources. This paper proposes alternating phase optimization and power optimization to optimize the energy consumption, latency, and communication secrecy rate, thereby maximizing the weighted total utility of the system. Simulation results demonstrate a notable enhancement in the weighted total system utility and resource utilization, thereby corroborating the viability of our approach for practical applications.Keywords

The emergence of Vehicle to Everything (V2X) has ushered in an era based on ubiquitous connectivity and intelligent data processing. Integrating V2X with edge computing as mobile edge computing (MEC) reduces network load by processing and analyzing data at edge nodes [1–3], thereby decreasing the traffic transmitted to remote data centers. This alleviates the burden on the core network, improving the overall network efficiency and reliability. By deploying computational resources on devices in vehicles near a base station (BS) with MEC servers, MEC can effectively reduce the latency of computation [4,5], conserve computational resources, and minimize the energy consumption of these devices [2]. Therefore, MEC has the potential to handle compute-intensive and latency-critical tasks for V2X systems.

In urban environments where buildings are densely packed, these physical barriers severely block the signal transmission of data sent from vehicles to the BS. This complex urban structure not only weakens the signal strength but also increases the likelihood of multipath propagation and reflection of signals, which significantly reduces the reliability and efficiency of data transmission. In this context, UAV have become a key component of the connected vehicle ecosystem, providing greater flexibility and coverage for communication and data processing tasks. Moreover, edge computing architectures face significant centralization issues, posing several challenges. For example, centralized edge computing architectures have problems with flexibility, data privacy, and security [6]. Centralized storage and processing allow attackers to access large amounts of sensitive information by attacking only a small number of critical nodes, and this centralized vulnerability increases the risk of data leakage, highlighting the need for robust security measures to protect sensitive information. Blockchain can solve these problems [7–9], and integrating V2X and blockchain technology further enhances the security and reliability of data transmission across networks [10]. Smart contracts run on the blockchain and are responsible for performing an automated and trustless task-offloading process between nodes. This mechanism ensures that transactions are not rejected and that malicious behavior can be tracked [11–13].

Computational offloading for V2X currently faces two challenges. First, traditional solutions usually focus on optimizing either computational or communication performance, such as minimizing computational latency, reducing energy consumption, or maximizing network throughput [14,15]. However, edge computing resources are limited, and there may be costs when they are used, which is not considered in most current computing offloading schemes. The efficient allocation and management of these resources to optimize the execution of computational tasks is a major challenge. Secondly, the high-speed movement of vehicles leads to frequent changes in V2X network topology, which increases the difficulty of maintaining stable and secure links. At the same time, due to the presence of eavesdroppers in the environment, rapidly changing topologies make it difficult to apply traditional static security mechanisms effectively. An intelligent reflecting surface (IRS) can effectively solve this problem outlined above, which can enhance signal coverage and connection stability by dynamically adjusting the direction and strength of the reflected signal [16,17]. Moreover, the IRS can modify the reflective surface in real time [18,19] to accommodate fluctuating network conditions and maintain a stable communication link when the vehicle is in motion at high speeds. In contrast to the above joint optimization methods, this paper introduces a unique approach by integrating UAVs, IRS, and blockchain technology to address the multifaceted challenges in Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) networks. Unlike traditional methods that optimize either computational or communication performance, this approach simultaneously optimizes multiple objectives, including energy consumption, latency, communication secrecy rate, and cost. The flexibility of UAVs and the adaptive capabilities of the IRS allow for dynamic adjustments in real-time, maintaining stable communication and security in a fast-changing V2X environment. This distinctive combination provides a more comprehensive solution compared to the existing literature.

In recent years, Blockchain has had a multitude of applications in the field of V2X, due to its decentralized, immutable, and transparent nature providing security and reliability.

Firdaus et al. [20] proposed a decentralized trust system based on the in-vehicle edge computing network that utilizes federated blockchain and smart contracts to ensure a trustworthy environment for securely storing and sharing data in the system. This addresses the challenges of mass data storage, trust management, and information security faced by traditionally architected intelligent transportation system (ITS) applications. Vishwakarma et al. [21] proposed a lightweight blockchain-based security protocol for secure communication and storage in vehicular networking, which supports modern software-defined networks (SDNs). The permission blockchain is used to ensure tamper-proof data storage and a fully traceable network for secure propagation of messages through cryptographic hash functions and encryption techniques. The scheme proposed by Lu et al. [22] can verify a vehicle’s identity in any driving scenario. By extending the traditional blockchain, it effectively satisfies the real-time condition, which presents a revocation-free list authentication scheme. The certificate and the real identity are encrypted with each other and stored in the blockchain, enabling conditional privacy. The scheme proposed by Lin et al. [23] ensured anonymous mutual authentication of vehicles, where only a trusted entity can recover the long-term public key, i.e., the true identity of the vehicle. A balance is struck between the requirements of anonymity, traceability, and key or certificate management in the Internet of Vehicles.

The utilization of a UAV as an MEC node enables the provision of enhanced location flexibility. UAVs can provide services at varying heights and locations, thereby extending the reach of traditional terrestrial BS to areas that would otherwise be inaccessible. Furthermore, the integration of UAV into V2X for task offloading can mitigate the obstruction of communication links, thus enhancing communication quality and reliability.

The UAV-assisted edge computing architecture proposed by Michailidis et al. indicates that hovering UAV can act as an airborne relay for task processing and further offload the computational tasks to ground-based roadside units, significantly reducing latency during data offloading and downloading and minimizing weighted total energy consumption [24]. In the study of Wang et al., the issue that users in heterogeneous wireless networks are unable to process data in a timely manner is addressed [25]. They propose an offloading scheme for UAV-assisted computation in a renewable energy-based MEC framework, which employs a deep reinforcement learning approach to minimize the offloading cost. Chen et al. combined UAV with MEC and proposed an efficient iterative algorithm, which represents the inaugural attempt to study the maximum-minimum average secrecy capacity problem [26]. The algorithm also addresses the security offloading issue that arises due to the absence of the exact location information in eavesdroppers.

In addition, as an emerging technology, the IRS demonstrates notable advantages in the offloading of tasks related to telematics. Optimizing the signal transmission path and improving the signal coverage and transmission efficiency can enhance the task offload performance of telematics. In recent developments, the deployment of IRS on UAVs has demonstrated potential for enhancing the performance of mobile vehicle communications. IRS can dynamically adjust the propagation environment to improve signal quality, thereby increasing system flexibility and reducing the risk of eavesdropping on air-to-ground channels. Another advantage of the IRS is that it can assist PLS, making the mission data upload link from the vehicle to the BS more secure. Upon receipt of the task data, the MEC server is able to allocate its computing resources to execute the task efficiently, thereby ensuring optimal processing. Zhai et al. proposed the use of a UAV as a relay IRS between the MEC server and the terrestrial MEC to minimize the total energy consumption of the system [27]. Wang et al. [28] proposed a secure transmission scheme for the presence of a single eavesdropper. This scheme jointly optimizes the BS transmit power, UAV position, and RIS phase shift to maximize the secure transmission rate. Hu et al. [29] and Xu et al. [30] focused on the energy consumption of IRS-assisted UAV MEC systems, where phase shifts and UAV trajectories are co-optimized by conventional iterative algorithms. In both cases, the IRS is deployed on the UAV, thereby exploiting the flexibility of the UAV to the fullest extent [31,32]. Xu et al. [33] sought to enhance the secrecy rate in the field of IRS-assisted PLS.

Qi et al. [34] proposed a RIS-assisted vehicular edge computing system. In order to minimize the power consumption of task offloading, it investigates the joint RIS phase-shift coefficient optimization and VU power allocation. To maximize energy efficiency, Qin et al. [35] proposed to iteratively optimize the bit allocation, transmit power, phase shift, and UAV trajectory.

Li et al. [36] proposed a novel Riemannian optimization method for optimizing the phase shift matrix with the objective of maximizing the secrecy rate. Liu et al. [37] proposed an IRS-assisted secure offloading scheme to improve the secrecy performance by adjusting the phase-shift matrix and deriving the traversal secrecy rate. This achieves more substantial computational resources for nodes paying higher Gas.

1.2 Motivations and Contributions

When a mobile vehicle offloads a computing task in V2X, factors such as latency, energy consumption, communication secrecy rate, computing resource allocation, and cost affect the offloading and computing of the task. At present, most of the existing mobile vehicle offloading task solutions often only consider a single factor, such as low latency, safety, or low energy consumption, when offloading computing tasks. However, they don’t take into account the full costs associated with task offloading and computation, including the service provider’s service fee. In addition, blockchain-enabled mobile vehicle computational offloading schemes tend to ignore the cost of blockchain, i.e., Gas fees. Scenarios that consider cost or multiple factors do not optimize the management of computing resources for multiple influencing factors at the same time. The proposed scheme in this paper considers the energy consumption, security, and latency of the system, as well as the cost of services for block and edge computing servers. The goal is to maximize the weighted utility in the system, which is defined in Section 2.4, by optimizing the IRS phase shift matrix, the transmit power of the moving vehicle, and the computational resource allocation scheme of the MEC. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) This paper proposes a secure V2X computing task offloading scheme supported by blockchain technology. The proposed solution establishes a PLS-assisted computation offloading model, which comprehensively considers the secrecy rate, latency and energy consumption of communication, service fees, computation latency and energy consumption of MEC, and blockchain Gas fees when offloading computation tasks for mobile vehicles.

(2) In the proposed scheme, the phase shift matrix of IRS and the transmission power of moving vehicles are jointly adjusted to increase the communication secrecy rate and reduce system latency and energy consumption during the communication process. Through this method, communication security can be maximized in the presence of Eve in the communication environment.

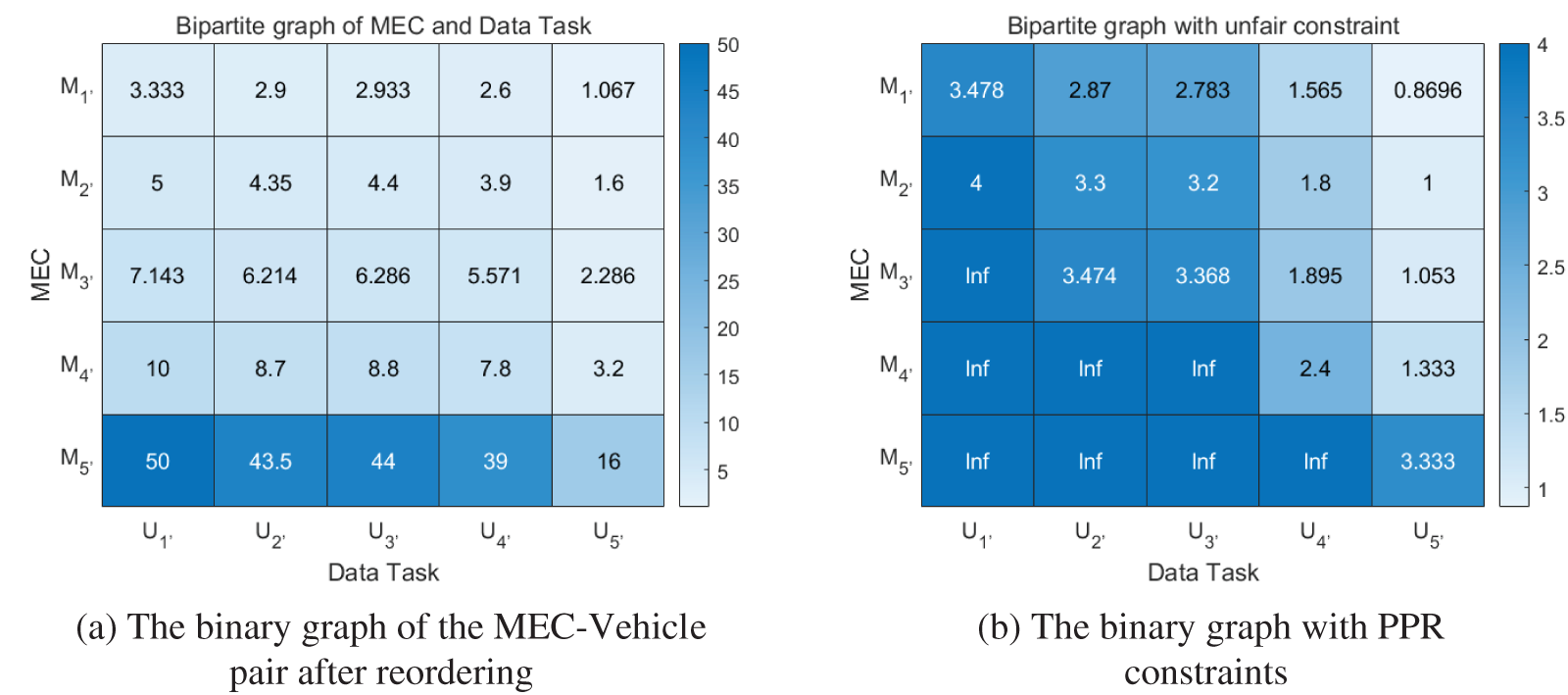

(3) The original computational resource allocation problem is transformed into a two-dimensional matching problem for two-part graphs, which is then solved with the KuhnMunkres (KM) algorithm. In particular, the edges of the bipartite graph are constrained by the balance between vehicle costs and resources. This ensures that vehicles paying high costs receive priority and better computational resources.

(4) The efficacy of our proposed scheme is demonstrated through simulations and performance evaluations. The results demonstrate a notable enhancement in the weighted total utility and resource utilization, thereby corroborating the viability of our approach for practical applications.

The remainder of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents the system model and problem formulation. In Section 3, we present our optimization schemes for phase shift optimization and power optimization. The task offloading scheme is provided in Section 4, while the experimental results are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary of the paper.

Special Notations: Bold uppercase letters, such as A, denote matrices, and bold lowercase letters, such as a, denote column vectors.

2 System Model and Problem Formulation

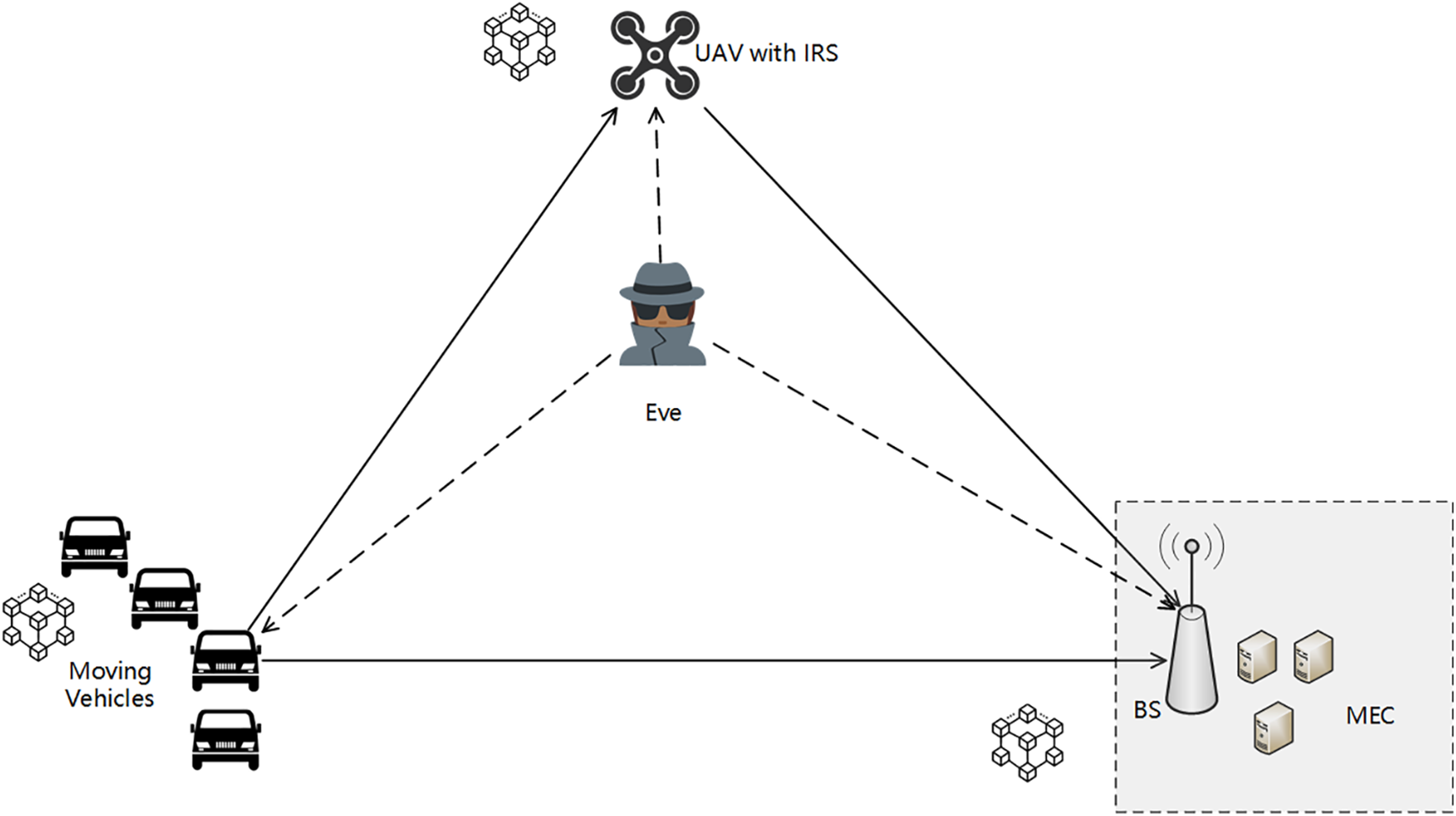

As shown in Fig. 1, this paper considers a blockchain-authorized vehicle network that includes

Figure 1: System model

When a mobile vehicle generates a computation task, it offloads the task to the BS, which in turn instructs an MEC server to perform the computation. Due to the distance between the vehicle and the BS and the presence of Eve, an IRS-equipped UAV (denoted as

In our system, a total of

IRS and phase-shift adjustment techniques increase the security of data transmission, reducing the risk of attack and ensuring data integrity and trustworthiness in the communication process.

To describe the secure transmission process of signals, this paper first assumes that the physical location information of each device including the Eve is available at the BS. The locations of

The distance from the IRS-UAV to the BS and to the Eve are respectively denoted as

The distance between the BS and the Eve is denoted as

In this paper, it is assumed that the signaling takes place in millimeter-wave communication. Then the channel gain link between

where N is the number of reflecting elements of IRS,

The channel gain from the IRS-UAV to the BS and to the Eve is expressed as

Also, the channel from

The diagonal matrix of the IRS reflection element is denoted as

The achievable data rate for unloading tasks is given by

where

Therefore, the transmission delay for the vehicle to offload the task to the BS is

where

The energy consumption of the whole system mainly includes computation energy consumption, transmission energy consumption, and block generation energy consumption. For the block generation energy consumption, it is assumed that the energy consumed by different nodes to generate blocks for this task is the same for task

As for a vehicle node, the energy consumed by the vehicle includes offloading data task energy and generating block energy [41], which are denoted by

where

As for the UAV node, since the UAV does not forward the data, the IRS equipped on the UAV only reflects the signal, and in the process of reflecting the data from the IRS, the UAV hovers at a fixed altitude, so the energy consumption of the UAV consists of hovering energy and generating block energy. The hover energy consumption of the UAV is denoted by

and

As for the energy consumption of BS and MEC, the MEC nodes need to perform task computation, which will generate corresponding energy consumption. In addition, after receiving the data, the BS will assign a suitable MEC to complete the task according to the computation capability of the MEC and the offer it has. After the MEC completes the computation, it will return the result to the BS, which will record the computation result and the identity of the MEC that performs the computation in the block to realize the traceability of the source of the result. Therefore, its energy consumption includes the computation energy consumption of the MEC and the block generation energy consumption of the BS. The energy consumption of the MEC computing task is denoted by

where

The total energy consumption required to complete the task

2.3 Computing Offloading Architecture Supported by Lightweight Blockchain

In our system, the lightweight blockchain is deployed on all participating nodes, including vehicles, UAV, and BS. These nodes all run lightweight blockchain clients that enable them to generate, validate, and store blockchain data. In order to reduce the overhead of the nodes, the specific data content is stored in the Inter Planetary File System (IPFS) [42,43], while only the hash information associated with this data is recorded on the blockchain.

Whenever data is being transferred, the sender needs to publish a task transfer block. The content of this block includes details such as the offloading task

When the receiver receives the task, it also needs to publish a block. The content of the receiver’s block includes the identity and address information of the receiver and the sender, the hash message corresponding to the task

On the blockchain, each block stores only the hash information and metadata of the transaction, while the raw data and detailed information are stored in the IPFS file system. This design effectively reduces the storage burden of the blockchain, and at the same time ensures the security and durability of the data by taking advantage of the decentralized storage characteristics of IPFS.

In this way, all nodes generate and publish blocks when transmitting data, realizing the traceability and non-repudiation of data transmission. At the same time, the combination of blockchain and IPFS can effectively prevent the computational offloading behavior of untrusted nodes and protect the security and privacy of transactions. The blocks of all participating nodes together build a complete blockchain, which ensures the transparency and data consistency of the whole system. The vehicle needs to pay for blockchain and MEC. The payment in the blockchain for the offloading task is denoted as

The cost in MEC is denoted as

where

Based on the above model, the essence of our work is to maximize the weighted total utility of the system by considering the system’s energy consumption, delay, and secrecy rate in the context of task allocation, power optimization, and phase shift optimization.

To measure the security performance, we use the secrecy rate

The utility value of the system for

For the whole system, the utility value is then expressed as

Mathematically, then, the optimization problem can be expressed as

The meaning of each of the above constraints is explained below.

Eq. (28b) indicates that each MEC server can only be assigned to one vehicle task, and similarly, a vehicle task can only be assigned to one MEC server. The assignment relationship between the

Eq. (28c) shows that there is a cost to completing the task, the Price-Performance Ratio (PPR) is used to measure the fairness between the cost and the allocation of computing resources. If

Eq. (28d) indicates that the time to complete a task cannot be indefinitely long. The total time required for a task from offloading to computation completion is

Eq. (28e) is the passive phase shift constraint matrix.

P1 is represented in a complex non-convex form. To solve this problem, the original problem P1 is decomposed into two manageable subproblems, i.e., phase shift optimization and power optimization, and solve the subproblems iteratively to finally obtain the near-optimal solution. The subproblem-solving and the corresponding algorithm design are described in detail in the next section.

3 Problem Solution and Algorithm Design

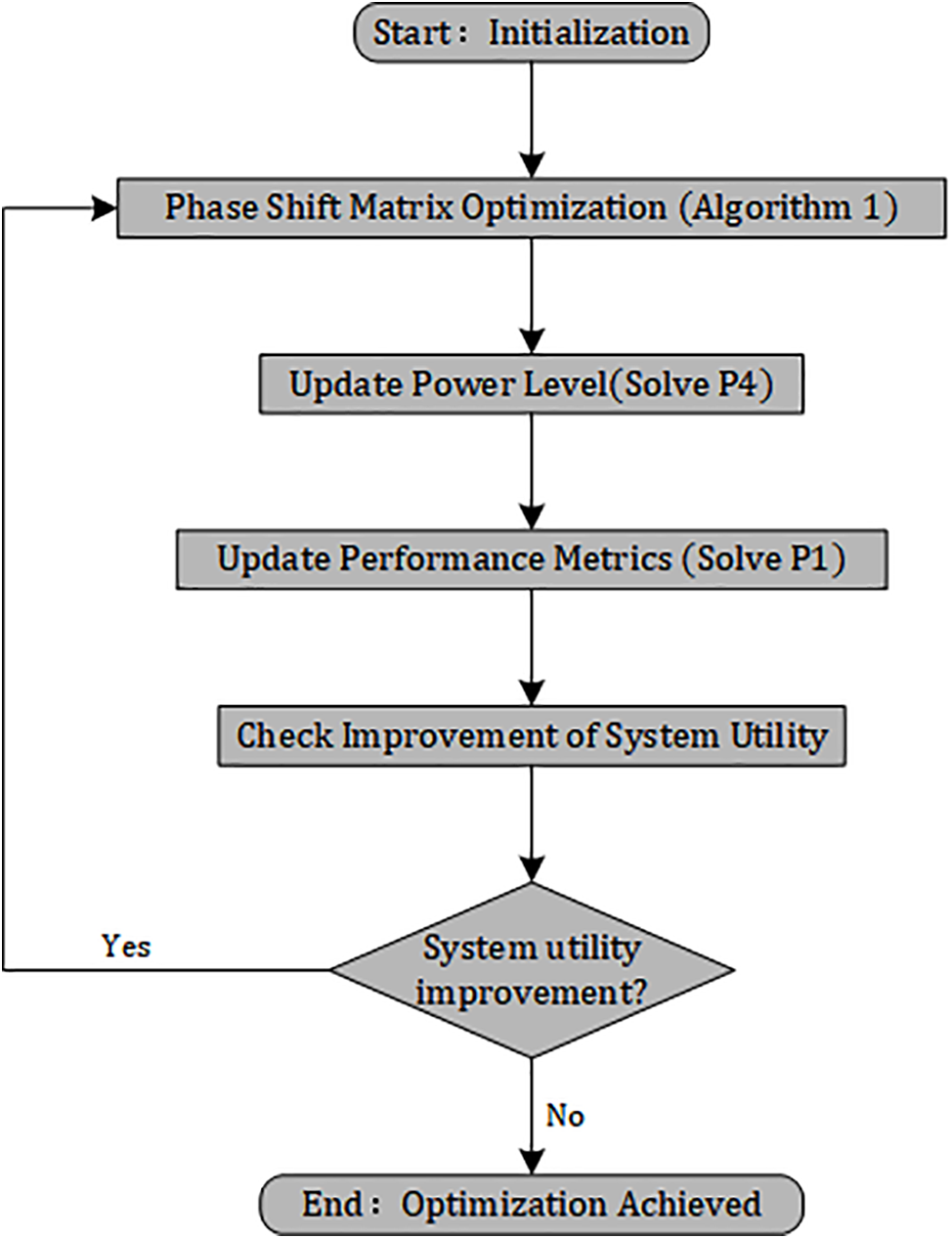

In this section, an algorithm framework is proposed to improve system utility by optimizing the phase shift matrix and power allocation. To demonstrate the optimization process more clearly, Fig. 2 summarizes the algorithm design and implementation process in this section. Fig. 2 illustrates the specific steps of initializing parameters, performing phase shift matrix optimization, updating power, and iteratively optimizing system utility indicators. In each iteration, the algorithm continuously optimizes the phase shift matrix and power until the system utility value no longer significantly improves, ultimately achieving the goal of system optimization.

Figure 2: Workflow of the optimization process in Chapter 3

3.1 Phase Shift Optimization of IRS

From Eq. (26), the total delay and energy consumption decrease as

s.t. (28e).

The objective parameter

where

The minus of the objective in P2 is expressed as a function concerning

The constraint (28e) is defined by a complex circle manifold [45], which is given by the following formula:

where

P3 is regarded as a complex circle manifold optimization problem. Similar to [37], the Riemannian gradient descent algorithm is used to find

where

Similar to the Euclidean space, there is one tangent vector with the steepest increase of the objective function, called the Riemannian gradient. As the complex circle manifold

In Riemannian gradient descent, the direction of the next point of

Typical retraction functions are normalization functions, i.e.,

where

Since the second-order derivatives of

Complexity analysis. To meet the convergence condition, the conjugate-gradient descent algorithm requires

3.2 Power Solving and System Optimization

The previous solution, it is equivalent to the phase shift matrix and parameters are given. So the objective of P1 could be rewritten into P4 as follows:

s.t. (28a),

After defining the objective function P4, the analytic method is used to search for the optimal value of the objective function by measuring the key performance metrics of the system, such as secrecy rate, time delay, and energy consumption, subject to constraints. These constraints include device power limits and delay limits.

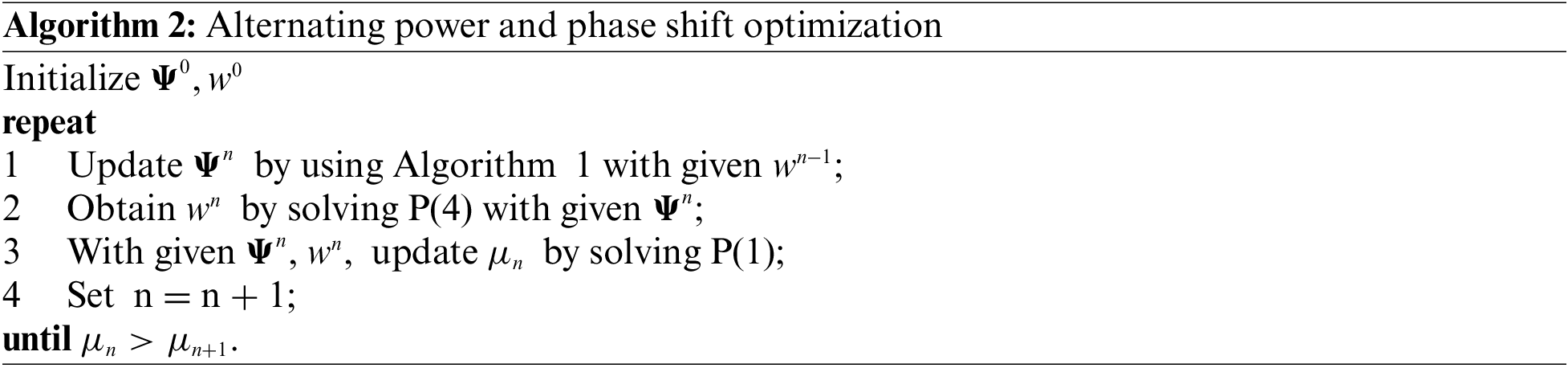

The alternating power and phase shift optimization algorithm performs the optimization by initializing the phase shift matrix

Complexity analysis. The loop runs until

4 Task Offloading Scheme Considering Gas

This chapter introduces a resource allocation plan that considers Gas fees. To ensure that the ratio of the cost paid for each vehicle to the computing resources obtained for the corresponding task of the vehicle is not less than the threshold, i.e.,

Figure 3: Bipartite graph generation with the dissatisfaction degree constraint

Based on the above information, a matching matrix

s.t. (28b).

where

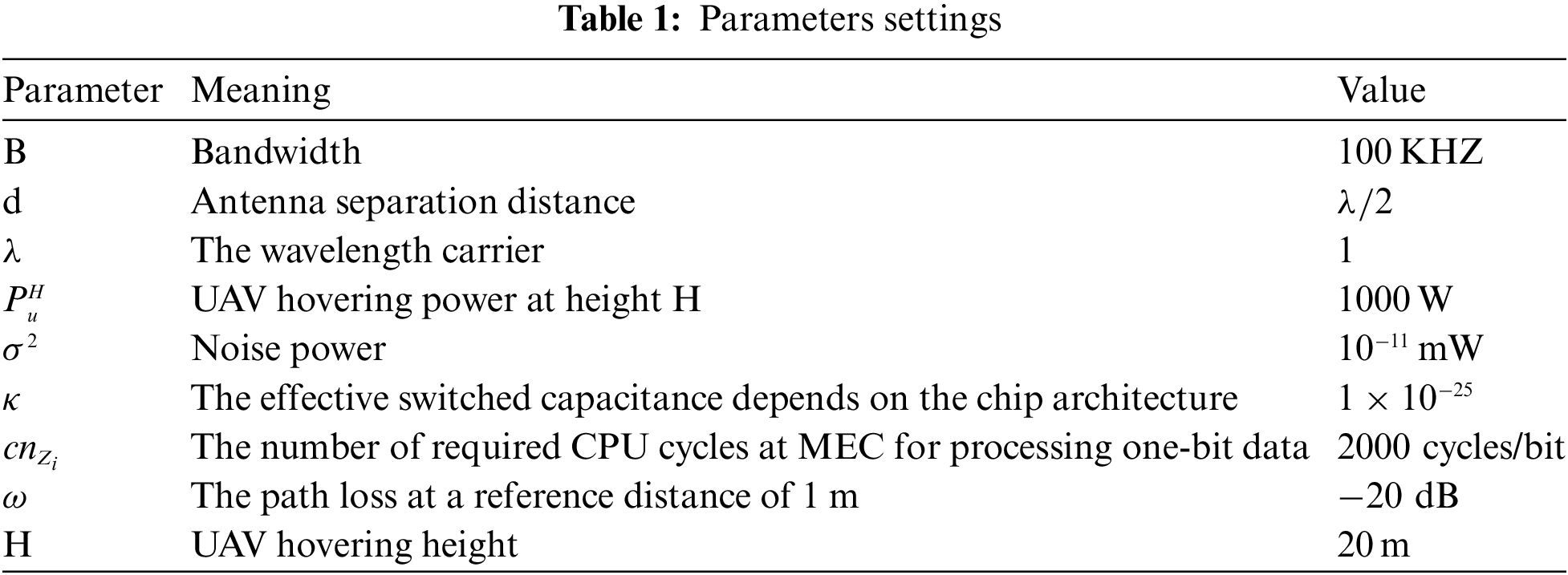

To evaluate the performance of the method proposed in this paper, detailed simulation experiments are conducted. By analyzing these experimental results, we can comprehensively understand the performance of the method in different scenarios and parameter settings, thus verifying its effectiveness and advantages. A series of specific simulation parameters during the experimental process are presented in detail in Table 1.

Specifically, the following aspects are considered in the experiments. All experiments are conducted in the presence of an Eve. Regarding the communication channel, this paper adopts the common V2X communication channel model to simulate the actual wireless propagation environment. Another thing is the number of IRS reflector units, which directly affects the signal quality and coverage, and this paper tests the effect of different numbers of reflector units on the system performance. There is also the number of vehicles, which evaluates the performance of the intelligent optimization method in multi-user scenarios.

According to Fig. 4, the horizontal coordinate represents the number of iterations, and the vertical coordinate represents the system’s weighted utility value. The proposed method’s approach is effective, and the system-weighted utility value gradually increases and levels off as the number of iterations increases.

Figure 4: System utility value

The method proposed in this paper with the power-only optimization and phase-shift-only optimization methods are compared, and the rest of the parameters are the same. The results in Fig. 5 show that the proposed method outperforms the remaining two methods. The effect of iterative optimization is followed by an increase in the weighted total utility value of the system and its eventual convergence. Moreover, our proposed method’s system weighted total utility value is maximum compared to the two methods without power optimization and phase shift optimization. This is also validating the validity of the methodology of this paper.

Figure 5: Different optimizations methods

The reason that the method of optimization without phase shift in Fig. 5 presents a straight line is that the optimal power value has been found in the first optimization. Without any other variables changing, the value found the first time is the optimal value, and the value presented by another iteration is the same as the previous one, that is why, it presents a straight line.

Fig. 6 compares the change in the system utility value for different numbers of IRS components. We can see that when the number of IRS components changes, the system-weighted utility value also changes. As shown in Fig. 5, when the number of IRS components is 20, the system-weighted utility is the smallest, followed by the number of IRS components is 40, the system-weighted utility value is in the middle, and when the number of IRS components is 30, the system-weighted utility value is the largest, this is because the change of the number of components affects the magnitude of the data transmission rate, which in turn is related to the secrecy rate, the time delay, and the energy consumption. This explains that it is not the more or less number of components that makes the system utility value greater, but it is necessary to find a suitable number of components that makes the system utility maximum.

Figure 6: Different elements of the IRS

The number of vehicles in the system is not static, and to verify whether the change in the number of vehicles affects the stabilized type of the method in this paper, different numbers of vehicles are set up for comparison. As shown in Fig. 7, the final utility value of the system changes slightly under different numbers of vehicles. This also shows that the stability of the system is not affected by the change of the number in vehicles, which proves the stable type of the method.

Figure 7: Different numbers of vehicles

Next, the relationship between the parameters affecting the utility of the system and the utility itself will be presented. From Fig. 8, the results show that the system-weighted utility value and the secrecy rate have the same trend and show an increasing state at the same time after applying the method of this paper. On the contrary, the energy consumption and time delay have the opposite trend to the system utility value, showing a decreasing state. Among them, it is worth noting that the time delay curve. Although the graph presents an approximate straight line. However, after optimization, the total value of delay decreases by 0.038191 s, which is a small change, and that is why it presents the state in the figure.

Figure 8: Link between secrecy rate, delay, and energy consumption and system utility value

Finally, to observe the effect of the Gas fee on the system, a set of comparison tests with a fee of 100 times the normal Gas fee was set up. Fig. 9a shows the difference between the weighted utility value of the system with a normal Gas fee and the weighted utility value of the system with 100 times of Gas fee for the case of the number of vehicles 5. It can be observed that the difference between the two increases significantly as the number of iterations rises, indicating that the utility value of the system with a high Gas fee is lower than that of the system with a normal Gas fee. Fig. 9b shows the difference between the normal Gas fee and the weighted system utility value of high Gas for the number of vehicles 5 as well as 20. It can be observed that the higher the number of vehicles, the more pronounced the effect of Gas.

Figure 9: Impact of Gas fee

From Fig. 10, it can be observed that when the UAV height is 120 m, the system utility value rises rapidly, reaches the highest value, and remains at a high level. The system utility values for UAVs at heights of 180 and 60 m are relatively low. This indicates that excessive height leads to increased signal loss, which negatively impacts utility. On the other hand, too low a height results in limited signal coverage, thus affecting the utility value. At a height of 120 m, the balance between signal coverage and path loss is achieved.

Figure 10: Comparison of different UAV height

This paper investigates a blockchain-enabled UAV-assisted multi-object offloading scheme in V2X systems, which enhances communication performance and system flexibility by deploying IRS on UAV while addressing the Eve problem in both ground and air channels. To address the problem of ignoring the Gas cost and MEC computation cost of computational offloading in existing computational offloading schemes, this paper designs a cost-oriented computational offloading scheme that ensures the balance between cost and resources, and achieves the optimization of energy consumption, delay, and communication secrecy rate through the alternation of phase shift optimization and power optimization, and finally achieves the maximization of the overall weighted utility of the system. The IRS-assisted computational offloading model proposed in this paper, combined with the phase-shift matrix adjustment scheme of flow shape optimization and the computational resource allocation method via two-part graph matching, significantly improves the system’s weighted total utility and resource utilization. The algorithms utilized in this study enhance the overall global optimization performance. The combination of the Alternating Optimization and KM algorithms effectively mitigates the risk of converging to unexpected local optima, while the global search capabilities of the Manifold Optimization algorithm contribute to achieving the global optimal solution. However, the KM and Manifold Optimization algorithm may require additional mechanisms to handle resource fluctuations and dynamic optimization demands in changing environments. This is an area that requires improvement in our future work. Specifically, future work aims to develop approaches to better adapt to dynamically changing environments, enhance the system’s real-time responsiveness and overall optimization performance, and achieve more robust and flexible resource management. Extensive simulation and performance evaluation results demonstrate the potential and effectiveness of the scheme in real-world telematics applications. This article considers fixed-price Gas fees, but their prices fluctuate. Therefore, future work will investigate the impact of fluctuating Gas fees on resource allocation.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank editors and reviewers for their valuable work.

Funding Statement: This work is supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant 2022YFB3104503; in part by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant 2024M750199; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62202054, Grant 62002022 and Grant 62472251; in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant BLX202360.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ting Chen, Xin Fan; formula derivation: Shujiao Wang; data collection: Xiujuan Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Chuanwen Luo, Yi Hong; draft manuscript preparation: Ting Chen, Shujiao Wang, Xin Fan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Readers can access the data used in this study by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1Gas fees are used to pay for the computational resources needed to execute a transaction or smart contract. Gas fees are incentives for miners or validators to process and validate transactions. The price of Gas is usually expressed in units of Gwei, and the unit price of Gas used in this document has been converted to units.

References

1. L. Brehon-Grataloup, R. Kacimi, and A. L. Beylot, “Mobile edge computing for V2X architectures and applications: A survey,” Comput. Netw., vol. 206, no. 4, 2022, Art. no. 108797. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2022.108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Y. L. Cong, K. Xue, C. Wang, W. X. Sun, S. X. Sun and F. Y. Hu, “Latency-energy joint optimization for task offloading and resource allocation in mec-assisted vehicular networks,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 72, no. 12, pp. 16369–16381, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TVT.2023.3289236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. H. B. Zhang, X. Y. Liu, Y. J. Xu, D. Li, C. Yuen and Q. Xue, “Partial offloading and resource allocation for MEC-assisted vehicular networks,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 1276–1288, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TVT.2023.3306939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. C. F. Liu, M. Bennis, M. Debbah, and H. V. Poor, “Dynamic task offloading and resource allocation for ultra-reliable low-latency edge computing,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 4132–4150, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TCOMM.2019.2898573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. G. Li, M. Zeng, D. Mishra, L. Hao, Z. Ma and O. A. Dobre, “Latency minimization for IRS-aided NOMA MEC systems with WPT-enabled IoT devices,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 14, pp. 12156–12168, 2023. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3240395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. E. Villar-Rodriguez, M. A. Pérez, A. I. Torre-Bastida, C. R. Senderos, and J. López-de-Armentia, “Edge intelligence secure frameworks: Current state and future challenges,” Comput. Secur., vol. 130, no. 3, 2023, Art. no. 103278. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2023.103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Z. Y. Guan, H. Z. Lyu, D. W. Li, Y. M. Hei, and T. C. Wang, “Blockchain: A distributed solution to uav-enabled mobile edge computing,” IET Commun., vol. 14, no. 15, pp. 2420–2426, 2020. doi: 10.1049/iet-com.2019.1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. W. J. Xu, W. Wang, Z. G. Li, Q. H. Wu, and X. B. Wang, “Joint task allocation and resource optimization for blockchain enabled collaborative edge computing,” China Commun., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 218–229, 2024. doi: 10.23919/JCC.fa.2022-0748.202404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. L. T. Qin, H. C. Lu, Y. A. Chen, Z. J. Gu, D. Zhao and F. Wu, “Energy-efficient blockchain-enabled user-centric mobile edge computing,” IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1452–1466, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TCCN.2024.3373624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. E. T. Michailidis, K. Maliatsos, D. N. Skoutas, D. Vouyioukas, and C. Skianis, “Secure UAV-aided mobile edge computing for IoT: A review,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 86353–86383, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3199408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Y. L. Wu, H. N. Dai, and H. Wang, “Convergence of blockchain and edge computing for secure and scalable IIoT critical infrastructures in industry 4.0,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 2300–2317, 2020. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.3025916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. J. A. Alzubi, O. A. Alzubi, A. Singh, and T. M. Alzubi, “A blockchain-enabled security management framework for mobile edge computing,” Int. J. Netw. Manag., vol. 33, no. 5, 2023, Art. no. e2240. doi: 10.1002/nem.2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. F. Xiong, C. Xu, W. Ren, R. Y. Zheng, P. S. Gong and Y. Ren, “A blockchain-based edge collaborative detection scheme for construction internet of things,” Autom. Constr., vol. 134, no. 1, 2022, Art. no. 104066. doi: 10.1016/j.autcon.2021.104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. X. X. Dai, Z. Xiao, H. B. Jiang, and J. C. S. Lui, “UAV-assisted task offloading in vehicular edge computing networks,” IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 2520–2534, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2023.3259394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. M. S. Bute, P. Z. Fan, G. Liu, F. Abbas, and Z. G. Ding, “A cluster-based cooperative computation offloading scheme for C-V2X networks,” Ad Hoc Netw., vol. 132, no. 6, 2022, Art. no. 102862. doi: 10.1016/j.adhoc.2022.102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. L. J. Wang et al., “Joint phase shift design and resource management for a non-orthogonal multiple access-enhanced internet of vehicle assisted by an intelligent reflecting surface-equipped unmanned aerial vehicle,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 5, 2024, Art. no. 188. doi: 10.3390/drones8050188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. C. Chen et al., “Joint design of phase shift and transceiver beamforming for intelligent reflecting surface assisted millimeter-wave high-speed railway communications,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 6253–6267, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TVT.2022.3233066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Z. X. Huang, L. P. Zhu, and R. Zhang, “Intelligent surfaces aided high-mobility communications: Opportunities and design issues,” IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 122–128, 2024. doi: 10.1109/MCOM.003.2300213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. D. Dampahalage, K. B. Shashika Manosha, N. Rajatheva, and M. Latva-aho, “Intelligent reflecting surface aided vehicular communications,” in Proc. 2020 IEEE Globecom Workshops, 2020, pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1109/GCWkshps50303.2020.9367569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. M. Firdaus and K. H. Rhee, “On blockchain-enhanced secure data storage and sharing in vehicular edge computing networks,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 1, 2021, Art. no. 414. doi: 10.3390/app11010414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. L. Vishwakarma, A. Nahar, and D. Das, “LBSV: Lightweight blockchain security protocol for secure storage and communication in SDN-enabled IoV,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 5983–5994, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TVT.2022.3163960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Z. J. Lu, Q. Wang, G. Qu, H. C. Zhang, and Z. L. Liu, “A blockchain-based privacy-preserving authentication scheme for vanets,” IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst., vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 2792–2801, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TVLSI.2019.2929420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. C. Lin, X. Y. Huang, and D. B. He, “EBCPA: Efficient blockchain-based conditional privacy-preserving authentication for vanets,” IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 1818–1832, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TDSC.2022.3164740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. E. T. Michailidis, N. I. Miridakis, A. Michalas, E. Skondras, D. J. Vergados and D. D. Vergados, “Energy optimization in massive mimo uav-aided mec-enabled vehicular networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 117388–117403, 2021. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. H. Wang, H. C. Ke, and W. J. Sun, “Unmanned-aerial-vehicle-assisted computation offloading for mobile edge computing based on deep reinforcement learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 180784–180798, 2020. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3028553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. P. P. Chen et al., “Secure task offloading for MEC-aided-UAV system,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 3444–3457, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TIV.2022.3227367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Z. Y. Zhai, X. H. Dai, B. Duo, X. Wang, and X. J. Yuan, “Energy-efficient UAV-mounted RIS assisted mobile edge computing,” IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett., vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 2507–2511, 2022. doi: 10.1109/LWC.2022.3206587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. D. W. Wang, Y. Zhao, Y. Lou, L. N. Pang, Y. X. He and D. Zhang, “Secure NOMA based RIS-UAV networks: Passive beamforming and location optimization,” presented at the 2022 IEEE Global Commun. Conf., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Dec. 4–8, 2022. [Google Scholar]

29. H. Hu, Z. C. Sheng, A. A. Nasir, H. W. Yu, and Y. Fang, “Computation capacity maximization for UAV and RIS cooperative MEC system with NOMA,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 592–596, 2024. doi: 10.1109/LCOMM.2024.3357752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Y. Xu, T. K. Zhang, Y. X. Zou, and Y. W. Liu, “Reconfigurable intelligence surface aided UAV-MEC systems with NOMA,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 26, no. 9, pp. 2121–2125, 2022. doi: 10.1109/LCOMM.2022.3183285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. X. K. Song, Y. L. Zhao, Z. L. Wu, Z. T. Yang, and J. Tang, “Joint trajectory and communication design for IRS-assisted UAV networks,” IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett., vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1538–1542, 2022. doi: 10.1109/LWC.2022.3179028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. H. Q. Lu, Y. Zeng, S. Jin, and R. Zhang, “Aerial intelligent reflecting surface: Joint placement and passive beamforming design with 3D beam flattening,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 4128–4143, 2021. doi: 10.1109/TWC.2021.3056154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. S. Xu, J. J. Liu, and Y. R. Cao, “Intelligent reflecting surface empowered physical-layer security: Signal cancellation or jamming?” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1265–1275, 2021. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3079325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. K. W. Qi, Q. Wu, P. Y. Fan, N. Cheng, W. Chen and K. B. Letaief, “Reconfigurable intelligent surface aided vehicular edge computing: Joint phase-shift optimization and multi-user power allocation,” 2024, arXiv:2407.13123. [Google Scholar]

35. X. T. Qin, Z. Y. Song, T. W. Hou, W. J. Yu, J. Wang and X. Sun, “Joint optimization of resource allocation, phase shift, and UAV trajectory for energy-efficient RIs-assisted UAV-enabled MEC systems,” IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1778–1792, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TGCN.2023.3287604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. X. Z. Li, Z. Li, Z. Y. Zhu, D. W. Zhang, L. Liu and M. Atiquzzaman, “Secrecy rate maximization for intelligent reflecting surface assisted MIMO systems in vehicular networks,” IEEE Internet Things J., 2023. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3332896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Y. L. Liu, Z. Su, and Y. T. Wang, “Energy-efficient and physical-layer secure computation offloading in blockchain-empowered internet of things,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 6598–6610, 2022. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2022.3159248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. M. Asim, M. ELAffendi, A. A. A. El-Latif, “Multi-IRS and multi-UAV-assisted MEC system for 5g/6g networks: Efficient joint trajectory optimization and passive beamforming framework,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 4553–4564, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2022.3178896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. B. Duo, M. L. He, Q. Q. Wu, and Z. X. Zhang, “Joint dual-UAV trajectory and RIS design for ARIS-assisted aerial computing in IoT,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 22, pp. 19584–19594, 2023. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3288213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. X. B. Zhou, S. H. Yan, Q. Q. Wu, F. Shu, and D. W. K. Ng, “Intelligent reflecting surface (IRS)-aided covert wireless communications with delay constraint,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 532–547, 2021. doi: 10.1109/TWC.2021.3098099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Q. Tang, L. X. Liu, C. Y. Jin, J. Wang, Z. F. Liao and Y. S. Luo, “An UAV-assisted mobile edge computing offloading strategy for minimizing energy consumption,” Comput. Netw., vol. 207, no. 3, 2022, Art. no. 108857. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2022.108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. J. Sun, X. M. Yao, S. P. Wang, and Y. Wu, “Blockchain-based secure storage and access scheme for electronic medical records in IPFS,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 59389–59401, 2020. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2982964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. R. Kumar, R. Tripathi, N. Marchang, G. Srivastava, T. R. Gadekallu and N. N. Xiong, “A secured distributed detection system based on IPFS and blockchain for industrial image and video data security,” J. Parallel Distr. Comput., vol. 152, no. 2, pp. 128–143, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jpdc.2021.02.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. M. Naz et al., “A secure data sharing platform using blockchain and interplanetary file system,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 24, 2019, Art. no. 7054. doi: 10.3390/su11247054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. X. H. Yu, D. F. Xu, and R. Schober, “Miso wireless communication systems via intelligent reflecting surfaces (invited paper),” presented at the 2019 ICCC, Changchun, China, Aug. 11–13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

46. P. A. Absil, R. Mahony, and R. Sepulchre, Optimization Algorithms on Matrix Manifolds, Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools