Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ML-SPAs: Fortifying Healthcare Cybersecurity Leveraging Varied Machine Learning Approaches against Spear Phishing Attacks

Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Jouf University, Sakaka, 72341, Aljouf, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Saad Awadh Alanazi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 4049-4080. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057211

Received 10 August 2024; Accepted 23 October 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Spear Phishing Attacks (SPAs) pose a significant threat to the healthcare sector, resulting in data breaches, financial losses, and compromised patient confidentiality. Traditional defenses, such as firewalls and antivirus software, often fail to counter these sophisticated attacks, which target human vulnerabilities. To strengthen defenses, healthcare organizations are increasingly adopting Machine Learning (ML) techniques. ML-based SPA defenses use advanced algorithms to analyze various features, including email content, sender behavior, and attachments, to detect potential threats. This capability enables proactive security measures that address risks in real-time. The interpretability of ML models fosters trust and allows security teams to continuously refine these algorithms as new attack methods emerge. Implementing ML techniques requires integrating diverse data sources, such as electronic health records, email logs, and incident reports, which enhance the algorithms’ learning environment. Feedback from end-users further improves model performance. Among tested models, the hierarchical models, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) achieved the highest accuracy at 99.99%, followed closely by the sequential Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) model at 99.94%. In contrast, the traditional Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) model showed an accuracy of 98.46%. This difference underscores the superior performance of advanced sequential and hierarchical models in detecting SPAs compared to traditional approaches.Keywords

The healthcare industry’s transformation through digital technology has significantly improved patient care and data management. However, this digital evolution also brings forth serious cybersecurity challenges, especially Spear Phishing Attacks (SPAs). These attacks are particularly sophisticated, utilizing emails that mimic legitimate sources to steal sensitive information, such as login credentials and financial details. The prevalence of these attacks is notably high in the healthcare sector due to the abundance of sensitive personal and medical information [1–3]. As these threats become more common, healthcare organizations are increasingly relying on Machine Learning (ML) to detect and prevent them, showcasing the dual-edged nature of technological advancement in healthcare [4,5].

ML in healthcare is primarily employed to analyse large volumes of data to identify patterns that may indicate potential SPAs. Traditional ML models, however, often lack transparency in their decision-making processes, which can be a significant barrier in regulated industries like healthcare [6]. These models need to provide understandable and interpretable results to ensure that healthcare professionals can trust and effectively use the technology. Without transparency, the adoption of ML in sensitive environments would be limited, underscoring the need for models that healthcare workers can interpret and validate.

The application of ML extends beyond mere identification of threats. It includes developing features that can detect signs of SPAs and employing models that healthcare staff can easily understand. For example, ML can analyse email metadata, content, and user behaviour to identify unusual patterns [7]. Furthermore, using interpretable models like Decision Tree (DT) or rule-based systems enhances the transparency of the analytical process, allowing healthcare providers to trust and effectively act on the insights provided by the models [8].

Another innovative application of ML in this field is user profiling. This technique involves analysing historical data on how users interact with emails and the internet. By understanding normal behaviour patterns, ML models can flag actions that deviate from the norm, potentially identifying malicious attempts before they cause harm [9]. Additionally, integrating threat intelligence with ML models provides up-to-date information on current SPAs and malicious domains, further enhancing the model’s accuracy and reliability [10].

Lastly, the continuous learning aspect of ML is crucial for adapting to the evolving nature of cyber threats. By integrating feedback mechanisms, healthcare organizations can continuously refine their ML models. This ongoing improvement helps the models stay effective against new and changing SPAs, ensuring that the healthcare industry can maintain a robust defence against these targeted attacks [11]. Through these comprehensive strategies, ML not only strengthens cybersecurity in healthcare but also builds a foundation for future advancements in protecting sensitive patient data.

SPAs have become highly sophisticated, posing a substantial threat to the healthcare sector by targeting employees to extract sensitive information [12]. Although ML presents a promising solution by learning to detect and mitigate these threats, the lack of transparency in these models raises significant concerns, particularly in a sector as sensitive as healthcare [13]. To address these challenges, several research gaps have been identified that align with the aims and objectives of enhancing healthcare defence:

• Development of Transparent Machine Learning Models: There is a pressing need to develop ML models that are not only accurate but also transparent, providing clear explanations for their decisions within the healthcare context.

• Contextual Analysis of Spear Phishing Attacks: It is critical to conduct in-depth analyses of SPAs specific to healthcare, considering the unique vulnerabilities and social engineering techniques that could be exploited.

• Compliance with Regulatory Requirements: Research should focus on creating ML solutions that adhere to strict privacy regulations like HIPAA, ensuring that the interpretability of these models does not compromise patient confidentiality.

1.2 Research Aims and Objectives

The research aims to fortify the healthcare industry’s defence against SPAs through strategic data analysis and ML innovations. SPAs pose significant threats to healthcare data security, prompting the need for advanced detection systems that are both effective and understandable to those who operate them. The specific objectives to achieve this goal are:

• Dataset Collection and Pre-processing: Gather and refine a comprehensive dataset of SPAs aimed at the healthcare sector, ensuring data quality through standardization and noise reduction.

• Feature Selection and Engineering: Identify and engineer key features from the dataset that effectively distinguish between legitimate and SPAs within the healthcare context.

• Model Development and Interpretability: Develop accurate ML models that not only detect SPAs efficiently but also incorporate methodologies that enhance the interpretability of model decisions, making it easier to understand and trust the system’s predictions.

This research enhances defence mechanisms against SPAs in the healthcare industry using ML to tackle complex security challenges. The key contributions are:

• Enhanced Défense against Spear Phishing Attacks: The proposed solution significantly outperforms traditional security measures, reducing the prevalence and success of SPAs in healthcare environments.

• Improved Transparency and Interpretability: The ML techniques provide healthcare professionals with insights into the system’s decision-making process, ensuring understandable and verifiable alerts and actions using diverse performance measures.

The structure of this study is carefully organized to ensure a clear understanding of the research. Section 2 presents the Related Work, establishing the background necessary for understanding the field. Section 3 describes the Methodologies used for detecting SPAs. Section 4 offers a detailed Performance Analysis, assessing how the proposed model stacks up against existing benchmarks. Section 5 discusses the significance of the proposed techniques and their advantages over previous methods. Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing the main findings and contributions, addressing any limitations, and suggesting avenues for future research.

This literature review critically examines the advancements in SPAs detection, initially focusing on traditional ML models before delving into the application of neural network-based sequential models. The review further explores innovative techniques that enhance the detection capabilities, offering a comprehensive overview of current methodologies and their effectiveness in identifying and mitigating SPAs. This thorough analysis aims to identify gaps in current research and suggest directions for future studies to improve SPAs defence mechanisms.

2.1 Vulnerability of Healthcare to Spear Phishing Attacks

The healthcare sector’s rapid digital transformation has significantly increased its vulnerability to cyber-attacks, particularly SPAs. These attacks target healthcare facilities due to the rich, sensitive data they manage, including patient records and financial information. The researchers in [14] pointed out that such data is highly valuable on the black market, making healthcare institutions prime targets. The risk is compounded by the sector’s need to maintain continual access to critical information, making downtime caused by SPAs particularly damaging. As healthcare continues to integrate more digital technologies, the potential entry points for cyber-attacks multiply, necessitating robust defence to protect patient privacy and maintain institutional integrity. An efficient privacy-preserving model for Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) was proposed to enable secure data sharing between devices [15].

Healthcare organizations are increasingly vulnerable to SPAs, which exploit personal information to create targeted, deceptive messages [16]. These SPAs pose significant threats to patient data and healthcare systems [17]. Research has identified several factors that increase susceptibility to phishing, including personality traits like conscientiousness and gender, with women being more likely to respond. The availability of personal information about targets can significantly increase vulnerability, with high information availability making users nearly three times more susceptible [16]. Healthcare professionals often have limited awareness of these threats, emphasizing the need for robust cybersecurity infrastructure and mandatory staff training. While many employees are aware of phishing risks, ongoing education across the spectrum of cybersecurity is crucial, particularly regarding information leakage on social media platforms [18].

2.2 Machine Learning as a Défense Mechanism

ML offers promising solutions to enhance defence against SPAs in healthcare. According to [7], these technologies can effectively identify and mitigate threats by learning from the vast amounts of data generated in healthcare settings. ML algorithms can detect anomalies in email communications that may indicate SPAs. However, the often-opaque nature of these algorithms can be a significant barrier in environments that require high levels of trust and regulatory compliance. The inability to understand or interrogate the decision-making process of these models can hinder their acceptance and deployment in sensitive environments like healthcare.

ML has emerged as a powerful tool in both offensive and defensive cybersecurity strategies, particularly against SPAs. On the offensive side, ML algorithms can automate data extraction from open-source intelligence to create personalized phishing emails, achieving up to 99.69% accuracy in predicting attack success [19]. Defensively, ML techniques are employed in threat detection, malware classification, and network risk scoring [20]. To combat SPAs specifically, various ML algorithms have been evaluated, including Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression, and Ensemble methods. The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model has shown exceptional performance, achieving 99.2% accuracy in phishing detection [21].

2.3 Traditional Machine Learning Models in Spear Phishing Attacks Detection

This literature review begins by exploring the foundational role of traditional ML models in detecting SPAs. Techniques such as LR, DT, and SVM have been widely used due to their effectiveness in classifying emails based on features derived from content and metadata [22]. Research by [23] highlights how these models apply pattern recognition to differentiate malicious from benign communications effectively. However, while these methods provide a solid base, they often struggle with the dynamic nature of SPAs, which continuously evolve to bypass static filters and detection rules.

Traditional machine learning models have shown promising results in detecting spear phishing attacks. Various classifiers have been employed, with Naïve Bayes reaching 95.15% accuracy for phishing email detection, and Random Forest (RF) attaining 96.80% accuracy for phishing website detection [24]. A combination of stylometric, forwarding, and reputation features, along with an improved SMOTE algorithm, yielded high performance in distinguishing spear phishing emails, with a maximum recall of 95.56% and precision of 98.85% [25]. Another study utilized a hybrid approach combining Naïve Bayes (NB) and DT algorithms, validated against RF and LR [26]. A more recent study proposed a hybrid algorithm using SVM and LR, achieving 99.69% accuracy in predicting phishing attack success [19]. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of ML in combating SPAs.

2.4 Advancements with Neural Network-Based Sequential Models

The review progresses to examine how neural network-based sequential models, like Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) offer advancements in handling the sequential nature of text data in emails. Studies such as [27] demonstrate that these models capture temporal dependencies and nuances in email communication that traditional models might overlook. This ability makes them particularly suited for detecting sophisticated SPAs that employ subtle cues and context manipulation.

Recent advancements in neural network-based sequential models have significantly improved the detection of spear phishing attacks via email. Reference [28] proposed a dynamic evolving neural network using reinforcement learning, achieving high accuracy 98.63% and adaptability to new phishing behaviours. Reference [29] developed a model that learns character and word embeddings directly from email texts, attaining 99.81% accuracy on common datasets. Reference [30] demonstrated the effectiveness of neural networks for phishing email detection and classification. To address personalized filtering, Reference [31] introduced a Stackelberg game model for calculating optimal thresholds in sequential attack scenarios, outperforming existing approaches.

2.5 Leveraging Hierarchal Models for Enhanced Detection

Further, the review assesses the integration of hierarchal techniques, which have significantly improved SPAs detection’s accuracy and adaptability. For instance, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) have been adapted for text classification by extracting spatial hierarchies of features from textual data, as discussed by [32]. These models are noted for their ability to discern complex patterns in data, offering a more nuanced understanding of the content, which is crucial for identifying highly targeted SPAs.

Recent research has focused on leveraging CNN for enhanced phishing email detection. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CNNs in analysing email text content, achieving high accuracy, precision, and recall rates [33]. CNNs have shown promise in extracting meaningful features from email headers, text, and attachments, enabling the detection of both known and emerging phishing attacks. Further improvements have been achieved by augmenting one-dimensional CNN models with recurrent layers such as LSTM, Bi-LSTM, GRU, and Bi-GRU [34].

2.6 Adapting to Evolving Threats

Adaptability is another critical aspect of ML in combating SPAs. The studies [35–37] highlighted the importance of ML systems being capable of evolving in response to new and emerging SPAs. As attackers continuously refine their strategies, ML models must also adapt to identify and counteract these evolving threats effectively. This continuous learning approach helps maintain the relevance and efficacy of cybersecurity measures in a landscape where threat vectors swiftly change.

2.7 Integration into Healthcare Cybersecurity Protocols

The integration of ML into healthcare cybersecurity protocols offers a proactive approach to managing SPAs. Another research [38] emphasized the importance of not just reacting to threats as they occur but anticipating and preventing them through advanced threat detection systems. These systems, powered by ML, can significantly enhance the security posture of healthcare organizations by providing timely and accurate detection of SPAs, thereby reducing the risk of data breaches and ensuring the protection of sensitive patient information.

2.8 Challenges and Future Directions

Despite these advancements, the review identifies key challenges that persist in the field. The primary concern is the black-box nature of many advanced ML models, which limits their interpretability—a critical aspect in healthcare and other sensitive sectors, where understanding decision-making processes is vital. As per the findings of [39], there is a growing need for models that not only predict accurately but also provide insights into their predictions to ensure trust and compliance with regulatory standards.

In conclusion, this literature review synthesizes current research on ML’s role in SPAs detection, highlighting significant progress and outlining persistent challenges. The evolution from traditional models to more sophisticated neural network approaches marks a substantial advancement in the field. However, as SPAs become more refined, future research must focus on developing models that balance predictive power with transparency and adaptability to maintain efficacy in an ever-evolving threat landscape.

This section details the methodology used to enhance SPAs detection in healthcare through the application of interpretable ML techniques. The methodology is structured to address the key research objectives and fill identified gaps, focusing on dataset collection, feature engineering, model development, and testing into healthcare systems as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Proposed model for Machine Learning-Spear Phishing Attacks (ML-SPAs) detection

3.1 Dataset Collection and Pre-processing

This study compiled a comprehensive dataset of email communications, both legitimate and malicious, specifically targeting healthcare organizations. This dataset was curated from various sources and augmented with simulated SPAs. Pre-processing involved cleaning the data, standardizing email formats, and anonymizing sensitive information to comply with privacy regulations.

For the mathematical modelling of the dataset collection and pre-processing phase in this study, considers the following equations to formally represent the data handling processes:

The entire dataset

The augmented dataset

3.1.3 Dataset Cleaning and Anonymization Process

The pre-processed dataset

The standardized feature

These equations collectively model the transformation of raw email data into a structured, standardized, and secure format suitable for further analysis with ML techniques. This mathematical framework ensures clarity in the methodological steps involved in preparing this dataset for effective SPAs detection.

3.2 Feature Selection and Engineering

Features were carefully selected and engineered to capture the nuances of SPAs. This included analysing email metadata, the linguistic style of the body text, and patterns of user interaction with previous emails. Advanced natural language processing techniques were employed to extract and quantify these features, which were then scaled and normalized to prepare them for model training.

For this phase study can model the process mathematically on SPAs detection using ML by defining equations that encapsulate feature extraction, scaling, and normalization. These processes are crucial for preparing data inputs for efficient and effective ML model training.

Extract features

where

Quantify the extracted features

where

Scale the quantified features

where

Normalize the scaled features

where

3.3 Model Development and Interpretability

Several traditional ML models (Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), XGBoost, Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), MLP, and AdaBoost), sequential models (RNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU), and hierarchal model (CNN) were deployed and trained. Each ML model was evaluated for its accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score and sequential and hierarchal models were evaluated with Epochs, Time, Loss, Accuracy, Validation Loss, Validation Accuracy. Special emphasis was placed on interpretation of models to provide insights into the decision-making processes of the models.

In this phase study, formalized the approach and evaluation criteria for the various ML and sequential and hierarchal models using mathematical equations. These equations can encapsulate the training, evaluation, and interpretability of the models.

The training of various ML models is represented mathematically by Eq. (9):

where

3.3.2 Model Evaluation for Machine Learning Models

The evaluation metrics for ML models are defined as follows in Eqs. (10)–(13):

3.3.3 Model Evaluation for Sequential and Hierarchal Models

For sequential and hierarchal models, the following metrics shown in Eqs. (14) and (15) are utilized to evaluate the models’ training and validation performance:

3.4 Continuous Learning and Adaptation

The deployed models were equipped with mechanisms for continuous learning, allowing them to adapt to new and evolving SPAs. Feedback loops were established to refine the models based on the latest threat intelligence and real-world detection outcomes.

Now SPAs detection using ML can be mathematically modelled using the adaptation processes that allow deployed models to dynamically learn and evolve over time. This process involves updating the models periodically with new data, refining their parameters based on feedback, and ensuring they remain effective against the latest SPAs.

The model shown in Eq. (16) is updated iteratively based on new data and feedback to adapt to new and evolving SPAs:

where

3.4.2 Feedback Loop Incorporation

Feedback from the model’s performance is processed to refine and improve its parameters as shown in Eq. (17):

where

Adjustments to the model’s parameters or structure are made using a continuous learning function shown in Eq. (18), enhancing predictive accuracy over time:

where

3.4.4 Adaptation to New Threats

A decision rule evaluates whether the model needs further adaptation to address the dynamically changing threat landscape as shown in Eq. (19):

where

This methodology ensures a robust, adaptable, and transparent approach to SPAs detection, leveraging the latest advancements in ML while addressing the unique challenges faced by the healthcare industry. The whole process is summarized concisely in Algorithm 1:

This research evaluates the effectiveness of proposed models in detecting SPAs, using a rigorous testing strategy that compares them against state-of-the-art models. The primary data source for this evaluation is the publicly available “Phishing Email Detection” dataset from Kaggle, specifically chosen for its relevance to SPAs detection tasks. This choice ensures that the testing environment is both broad and challenging, accurately reflecting the real-world complexities involved in processing various email types and contexts.

In this research, the proposed model undergoes rigorous testing through systematic comparisons against established benchmarks and cutting-edge developments in neural network models. The evaluations extend beyond basic ML metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, and support scores, delving into the models’ capabilities to assimilate and interpret linguistic and thematic nuances across various email categories. These categories, such as 0 and 1, help in assessing the accuracy, macro average, and weighted average of each model. This comprehensive approach allows for a detailed understanding of how each model processes and responds to the complex data characteristics typical of SPAs. Such in-depth analysis ensures the proposed model’s efficacy and adaptability in real-world scenarios, providing a robust framework for advancing cybersecurity measures.

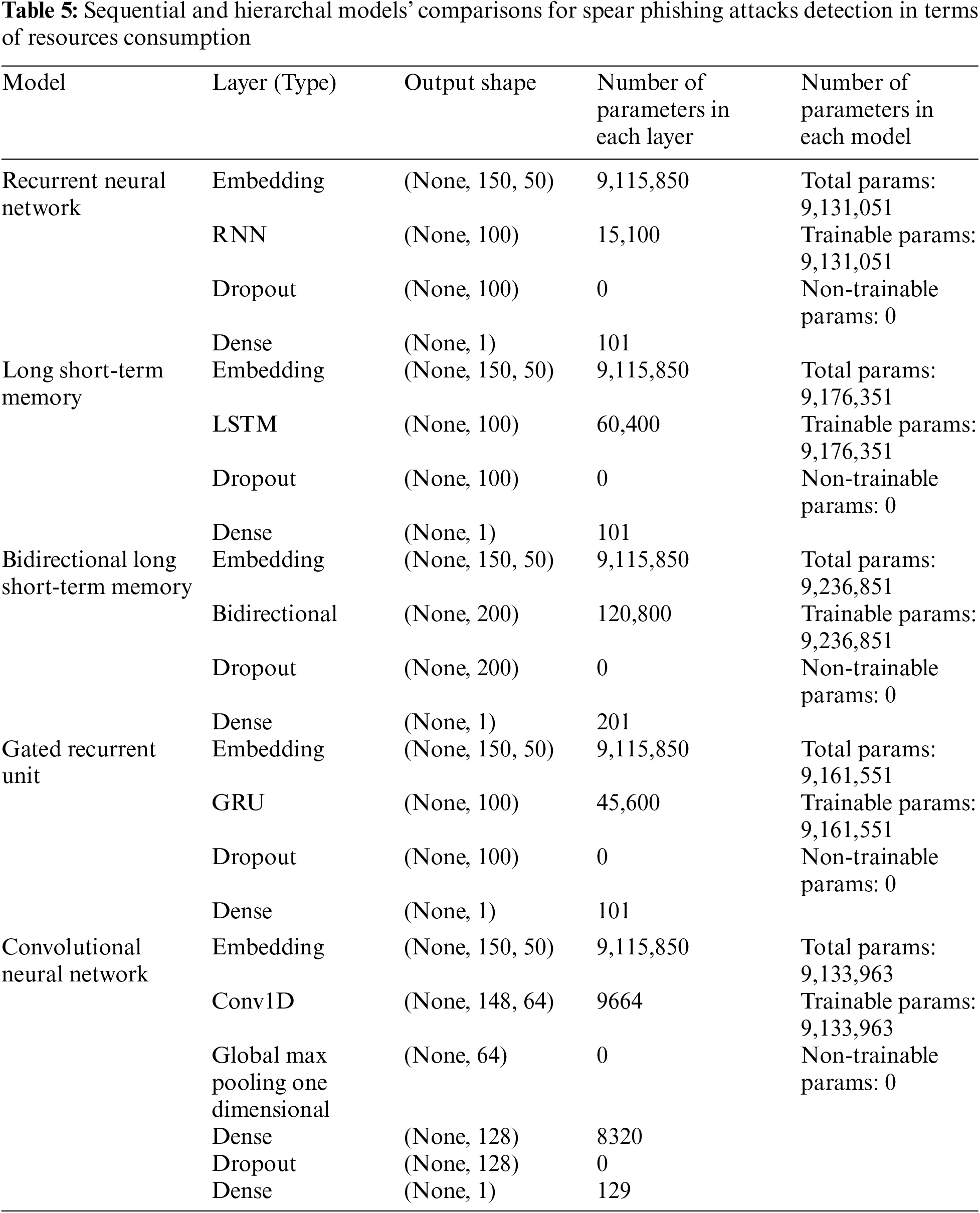

For sequential and hierarchal models, performance metrics include Epochs, Time, Loss, Accuracy, Validation Loss, and Validation Accuracy, further measuring how effectively these models can assimilate and analyse information. This comprehensive analysis extends to different email categories, providing insights into the models’ operational effectiveness under varied conditions. Moreover, this study involves a detailed examination of the models’ configurations, including layers, output shapes, parameters, total parameters, trainable parameters, and non-trainable parameters for DL models. This review highlights the bespoke nature of the proposed models, tailored specifically to tackle SPAs amidst contemporary advanced threats. The meticulous evaluation framework employed ensures that the findings are robust, offering definitive evidence of the proposed models’ superiority over existing methods. This approach not only confirms the models’ efficacy in real-world applications but also showcases their innovative use of advanced neural network techniques and adaptability to complex cybersecurity challenges in the healthcare sector.

4.1 Dataset Description and Selection Rationale

The dataset titled “Phishing Email Detection” on Kaggle [40] provides a robust framework for training ML models to detect SPAs, a significant threat leading to data breaches and financial losses in various sectors, including healthcare. This dataset comprises two main features: ‘Email Text’ and ‘Email Type.’ The ‘Email Text’ contains the body of the emails, which is crucial for identifying and analysing the linguistic and thematic elements associated with SPAs. ‘Email Type’ classifies each email as either ‘Phishing’ or ‘Safe,’ facilitating the training of models through supervised learning techniques.

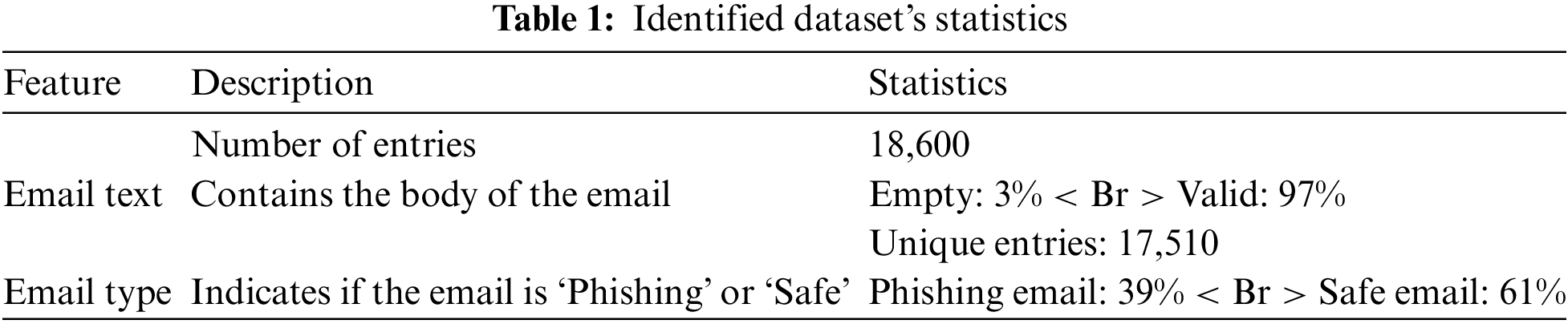

The dataset statistics reveal that it includes a total of 18,600 email entries, with 3% of the emails marked as ‘empty’ under the ‘Email Text’ feature, indicating missing content. This aspect underscores the importance of robust pre-processing steps to handle missing or incomplete data effectively. Moreover, the distribution between ‘Safe’ and ‘Phishing’ emails shows that 61% of the emails are safe, while 39% are SPAs. This balance provides a realistic scenario for training detection models, reflecting the frequent exposure to both legitimate and malicious emails in real-world settings.

The use of this dataset enables the deployment of various ML techniques, including NB, LR, and more complex models like RF and Neural Networks, to discern and predict SPAs accurately. By leveraging such a detailed and representative dataset, researchers and cybersecurity professionals can enhance detection algorithms, improving their ability to safeguard sensitive information against sophisticated cyber threats. The relevant statistics for the benchmark dataset are outlined in Table 1.

The dataset summary highlights key aspects crucial for effective ML model development. Specifically, the ‘Email Text’ field reveals that 3% of the entries are empty, necessitating pre-processing steps such as filling in or removing these entries to ensure optimal model training. Meanwhile, the ‘Email Type’ field shows a balanced distribution between safe and phishing emails, providing an ideal setup for training classification models. This balance is essential for accurately learning the distinguishing features that differentiate phishing from non-phishing emails, enhancing the effectiveness of the predictive models.

The dataset was specifically selected for its relevance and challenge in SPAs detection, as well as its established use in prior research, which facilitates direct comparisons with state-of-the-art models. This methodical evaluation framework ensures that the performance of the proposed model is benchmarked against the highest industry standards. It emphasizes the model’s innovative capabilities and effectiveness in accurately identifying and responding to SPAs, highlighting its potential to advance current cybersecurity measures in this critical area.

4.2 System Configuration and Implementation Settings

The proposed system configuration employs a high-performance Lenovo Mobile Workstation, ideal for processing complex datasets involved in SPAs detection. It features a 12th Generation Intel Core i9 processor, 128 GB of DDR4 memory, a 4 TB solid-state drive (SSD), and an NVIDIA RTX A4090 graphics card. Running on Windows 11 with Python version 3.12.0, this setup enables rigorous testing of the proposed model across various challenging datasets, ensuring robust analysis and performance benchmarking.

For data pre-processing, the system implements routines to clean the dataset by dropping duplicates and null values, essential for maintaining data integrity and model accuracy. The dataset predominantly comprises emails classified as ‘safe’ over those tagged as ‘Phishing.’ This imbalance informs a pre-processing strategy where suspected SPAs, potentially mislabelled or underrepresented, are carefully scrutinized and, if necessary, removed to enhance the training process. This approach helps in minimizing noise and focusing the model’s learning on truly representative features of SPAs.

This sophisticated system configuration combined with meticulous pre-processing practices supports advanced ML operations. It ensures that the models developed are not only accurate but also capable of handling real-world data efficiently. This setup underscores a commitment to leveraging cutting-edge technology and methodological rigor to enhance the detection capabilities against SPAs, thereby significantly boosting cybersecurity measures in sensitive environments like healthcare and finance.

The pie chart titled “Categorical Distribution” provides a visual breakdown of email categories within a SPAs dataset. The chart shows that 62.6% of the emails are classified as “Safe Email”, represented by the blue segment, while 37.4% are labelled as “Phishing Email”, depicted in orange. This visualization highlights the distribution of emails, emphasizing a higher prevalence of “Safe Emails” compared to “Phishing Emails”. This proportionate representation in Fig. 2 is crucial for understanding the dataset’s composition and assists in evaluating the effectiveness of ML models trained on this data. The chart effectively communicates the ratio of Safe to Phishing emails, providing essential insights for further analysis and model training.

Figure 2: Proportional distribution of email categories in phishing detection dataset

In the realm of text pre-processing for ML, particularly for natural language processing tasks like SPAs detection, several crucial steps are undertaken to refine the dataset for optimal model performance. The first step, integer encoding, involves converting textual data into numerical format so that ML algorithms can process the information. This is essential because models inherently understand numbers, not text.

Further pre-processing includes the removal of hyperlinks, punctuations, and extra spaces from the email texts. This cleansing process helps in reducing the noise within the data, ensuring that the algorithms focus solely on meaningful content. Hyperlinks and punctuation can introduce biases or irrelevant features that might mislead the model, while extra spaces could affect the structure of the data fed into the model.

Another vital pre-processing step is the creation of a word cloud of available stop words. Stop words are common words like “and”, “the”, “a”, which typically do not contain important significance and are removed from the text. Visualizing these stop words in a word cloud can help in understanding their frequency and distribution within the dataset. Removing these stop words further cleans the data, allowing the focus to remain on the crucial elements of the texts that contribute more significantly to the understanding and detection of SPAs. Together, these pre-processing steps refine the dataset, preparing it for effective and efficient analysis and classification by ML models.

This word cloud visually represents the most frequently occurring words in a dataset of email communications. The prominence of words like “the”, “of”, “to”, “and”, “in”, “for”, “you”, “with”, and “be” indicates their high usage in typical email texts. Such word clouds are instrumental in identifying common stop words—words that are usually filtered out before processing text data due to their minimal contribution to the overall meaning. This graphic illustrates not only the commonality of these words but also emphasizes the linguistic patterns that could be crucial for tasks like sentiment analysis, topic modelling, or spam detection where understanding text content is essential. By analysing this distribution in Fig. 3, researchers can better tailor their algorithms to focus on more meaningful and less frequent terms that might indicate specific behaviours or intentions within the emails.

Figure 3: Analysis of common words in word cloud of email communications

This word cloud shown in Fig. 4 visualizes the most frequently occurring words in a dataset of email communications, providing insights into common language usage within emails. Words like “time”, “information”, “people”, “use”, “work”, “need”, and “make” are prominently displayed, highlighting their prevalence in daily email interactions. The size of each word indicates its frequency, with larger words appearing more often in the dataset. This visualization helps identify key themes and terms that are typically used in emails, which can be crucial for tasks such as email categorization, sentiment analysis, and spam detection. By understanding these patterns, organizations can better tailor their communication strategies and improve email filtering algorithms.

Figure 4: Linguistic patterns analysis in email communication using word cloud of unique words

Pre-processing text data for ML applications typically involves converting text into a numerical format that algorithms can interpret. This process starts with using techniques like the Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer. The TF-IDF vectorizer quantifies the importance of a word in a document relative to a collection of documents or corpus, thereby transforming text into a set of vectors. This vectorization reflects how important a term is in the context of a document, which is pivotal for models to understand textual data.

Once text data is converted into vectors, it is essential to split the dataset into training and testing sets. This division allows the model to learn patterns from the training set and then validate its performance on the unseen test set. This method helps in assessing the generalizability of the model when faced with new data, which is crucial for its deployment in real-world applications.

After splitting the data, various algorithms can be applied to train on these vectors. Each algorithm, whether it be a traditional ML model like NB or LR, or more complex models like RF or Neural Networks, has its strengths and weaknesses in processing and learning from textual data. By applying different algorithms, one can evaluate which model performs best for the specific task of text classification or prediction, ensuring the most effective approach is used in practical scenarios.

This section of the study thoroughly analyzes the performance of various ML models on the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset, particularly for detecting SPAs. The evaluation is segmented into four parts. The initial segment assesses traditional baseline models including NB, LR, GBM, XGBoost, DT, RF, MLP, and AdaBoost. Subsequently, the study explores the efficacy of advanced sequential models like RNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, GRU, and CNN, which are specifically tailored for enhanced detection of advanced SPAs. This structured analysis helps in comparing the strengths and weaknesses of each model in a realistic setting.

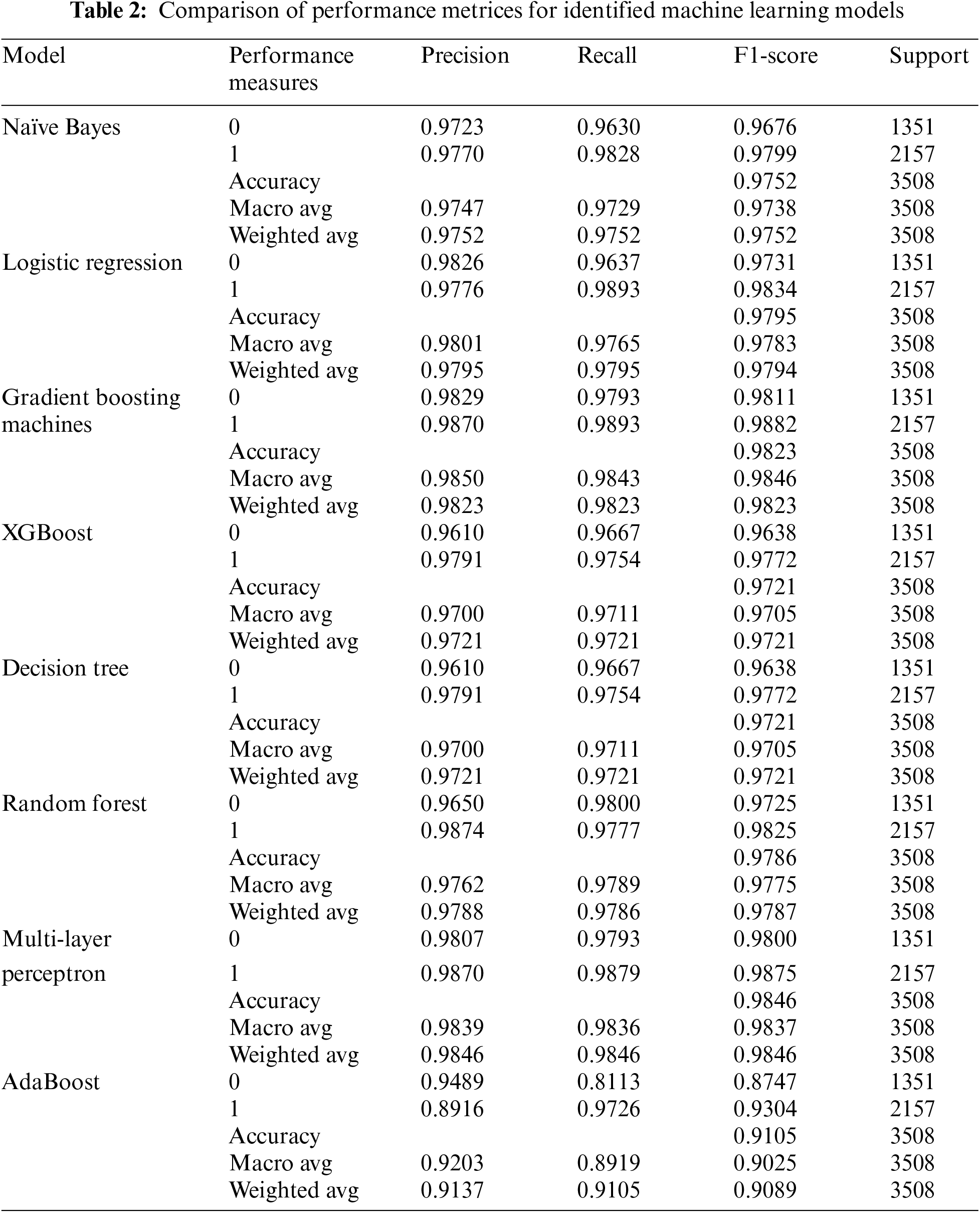

4.3.1 Overview of Spear Phishing Attacks Detection Model Performance

The overview provided in Tables 2 and 3 of the study details the performance metrics of various ML models applied to the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset for SPAs detection. These metrics include precision, recall, F1-score, and support scores, all crucial for evaluating the efficacy of the models in differentiating between SPAs and legitimate emails. Additionally, the study examines the DL models’ performance in terms of Epochs, Time, Loss, Accuracy, Validation Loss, and Validation Accuracy, offering a deeper insight into how well these models process and analyse data under varied conditions.

Furthermore, the study provides a detailed analysis of the models’ configurations, focusing on aspects such as layers, output shapes, parameters, total parameters, trainable parameters, and non-trainable parameters. This level of detail helps in understanding the structural and operational nuances of each model, particularly the DL models, and their adaptability to the complex requirements of SPAs detection. This comprehensive evaluation not only benchmarks the models against each other but also highlights their strengths and limitations in practical scenarios.

4.3.2 Performance Insights on Spear Phishing Email Detection Dataset Using Machine Learning

The detailed performance evaluation shown in Table 2 from the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset reveals significant insights into various ML models’ effectiveness in SPAs detection. The analysis categorizes the performance across two main types of email: ‘0’ and ‘1’, utilizing metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, and support for detailed assessment.

For category ‘1’, the MLP exhibits standout performance with the highest precision of 0.9870 and an F1-score of 0.9875, demonstrating its capability in handling complex patterns associated with SPAs effectively. This makes MLP the best-performing model in this category, optimized for accuracy and reliability. Conversely, the AdaBoost model registers lower metrics, with a precision of 0.8916 and an F1-score of 0.9304, highlighting areas for improvement and making it the least effective model for this category.

In category ‘0’, the GBM shows superior performance with impressive scores—particularly a precision of 0.9829 and an F1-score of 0.9811—indicating its high accuracy and balanced detection capability. On the other end, the AdaBoost, with a lower precision of 0.9489 and an F1-score of 0.8747, falls short compared to other models, underscoring the need for further tuning.

This granular evaluation not only identifies the strengths and weaknesses of each model but also provides a clear benchmarking framework that can guide future improvements and selections in ML deployments for SPAs detection.

The provided Fig. 5 showcases the confusion matrices for various ML models applied to the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset. Each matrix represents the performance of models including NB, LR, GBM, XGBoost, DT, RF, MLP, and AdaBoost in classifying emails as either ‘Phishing’ or ‘Safe’.

Figure 5: Performance comparison using confusion matrices for identified machine learning models

In these matrices, the x-axis typically represents the predicted categories and the y-axis the actual categories. The values within the matrix show the count of predictions falling into each category (True Positives, True Negatives, False Positives, False Negatives). These metrics are crucial for assessing the effectiveness of each model in correctly identifying and categorizing emails, providing insights into both their strengths and weaknesses.

From the arrangement and results depicted, it can be discerned that some models may exhibit higher false positives or false negatives, which could significantly impact their usability in real-world scenarios. For example, a model with a high number of false positives might frequently misclassify safe emails as phishing, leading to unnecessary alerts. Conversely, models with low false positives and negatives would be ideal as they maintain a balance, reducing the risk of overlooking actual phishing attempts and not overburdening the system with false alerts.

By analysing these matrices, stakeholders can make informed decisions on which models might require further tuning or optimization and which models are performing well under the current testing conditions. This form of evaluation is essential for continuous improvement in SPAs detection systems.

The confusion matrices provided for various ML models clearly show their performance in classifying emails within the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset. Notably, the AdaBoost model exhibited one of the weakest performances with 1096 true positives and 59 false negatives for SPAs, but significantly, 255 false positives and 2098 true negatives for safe emails, indicating a higher misclassification rate of safe emails as SPAs. Conversely, one of the best performances was observed in the model represented in the MLP confusion matrix, which achieved 1321 true positives and only 26 false negatives for phishing emails, along with 30 false positives and 2131 true negatives for safe emails, demonstrating a high accuracy and a balanced approach in detecting both categories effectively. These insights are crucial for refining the models to enhance their detection capabilities.

The Fig. 6 shows a bar chart titled “Performance of the models”, which visually represents the accuracy of various ML models applied to the “Phishing Email Detection” dataset. The chart displays the accuracy rates for each model, including NB, LR, GBM, XGBoost, DT, RF, MLP Classifier, and AdaBoost. Each model’s performance is indicated by a green bar, with the height of the bar corresponding to its accuracy percentage. Notably, the MLP Classifier shows the highest accuracy at 98.29%, while AdaBoost shows the lowest at 91.05%. This graphical representation provides a clear and immediate comparison of the effectiveness of each model in detecting SPAs.

Figure 6: Comparative accuracy analysis of machine learning models in spear phishing attacks detection

4.3.3 Performance Insights on Spear Phishing Email Detection Dataset Using Sequential and Hierarchal Models

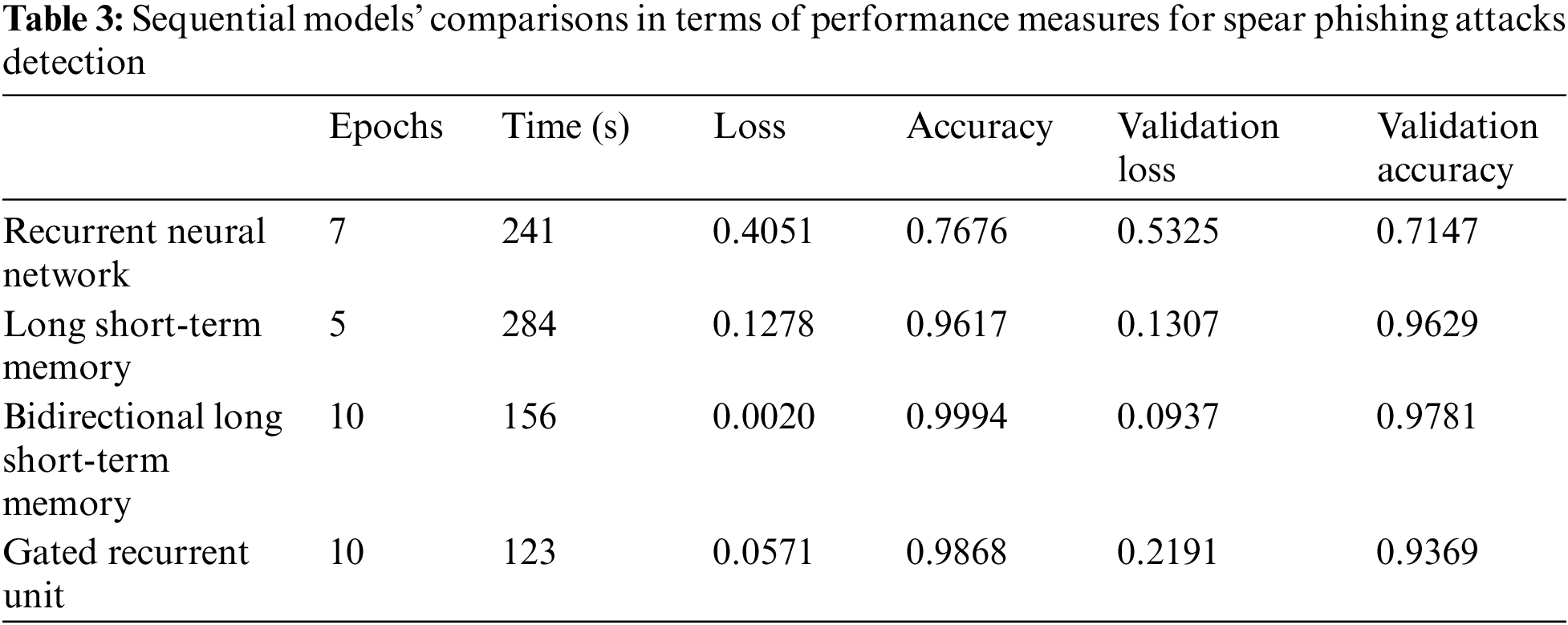

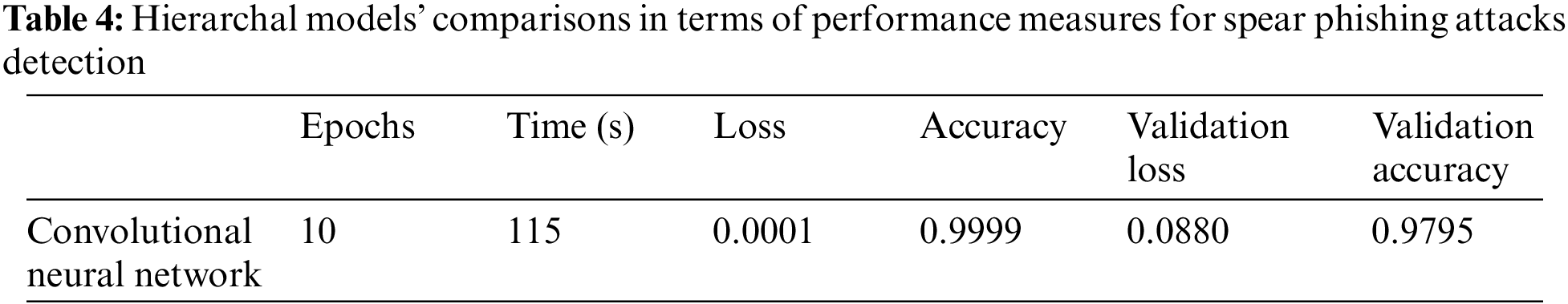

The performance insights from the sequential and hierarchal models as shown in Tables 3 and 4 on the SPAs detection dataset reveal significant variations in efficacy across different types of neural networks. The dataset results, presented in a comparative table, include measurements across Epochs, Training Time, Loss, Accuracy, Validation Loss, and Validation Accuracy.

The LSTM network shows excellent performance with an accuracy of 96.17% and a remarkable Validation Accuracy of 96.29%, coupled with low loss values (0.1278 training and 0.1307 validation), making it one of the best performers for this dataset. On the other hand, the basic RNN trails with notably lower performance metrics—76.76% accuracy and 71.47% Validation Accuracy, alongside higher loss values (0.4051 training and 0.5325 validation), indicating its relative inadequacy in handling this specific task.

Other models like the BiLSTM, GRU, and CNN also showcase strong performances with accuracies exceeding 98%. Specifically, the BiLSTM model achieves nearly perfect accuracy at 99.94% with a Validation Accuracy of 97.81%, and the CNN impresses with a Validation Accuracy of 97.95%.

These insights highlight the effectiveness of advanced neural network architectures in accurately detecting SPAs, with LSTM, BiLSTM, and CNN models providing robust solutions thanks to their ability to efficiently process and learn from complex data patterns inherent in email communications.

4.3.4 Comprehensive Evaluation and Implications

The analysis in Figs. 7 and 8 encompasses a range of sequential and hierarchal models tailored for SPAs detection, illustrating their performance through detailed graphs and confusion matrices. The models evaluated include RNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, GRU, and CNN. Each model’s performance is depicted through training accuracy trends, loss measurements, and confusion matrices that display true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives.

Figure 7: Sequential models’ comparisons for spear phishing attacks detection using diverse graphs

Figure 8: Hierarchal models’ comparisons for spear phishing attacks detection using diverse graphs

Starting with the RNN, it shows a steady improvement in training accuracy, reaching around 72%, yet it struggles with relatively high numbers of false negatives and positives, indicating a need for further refinement in terms of model precision and recall. The LSTM model, however, excels in its training, with accuracy soaring to 99%. It also records low training and Validation Loss, demonstrating robust learning capabilities. Its confusion matrix confirms its effectiveness, showing a significant number of true positives and very few false negatives, marking it as a top performer.

The BiLSTM maintains stable and high training and Validation Accuracy, with minimized losses after initial fluctuations. Its confusion matrix indicates a strong true positive rate, with very few false negatives, underscoring its efficiency. Similarly, the GRU model showcases high accuracy, above 98%, and low losses, with a confusion matrix that highlights its ability to accurately identify SPAs.

The CNN emerges as the most accurate model, achieving nearly perfect training accuracy and maintaining low loss levels. This is mirrored in its high Validation Accuracy and its confusion matrix, which shows an impressive count of true positives with minimal false negatives. This model’s performance suggests it has the best capability in the line-up for accurately detecting SPAs.

The overview highlights the distinct capabilities of each model, with the CNN and LSTM models showing particularly high effectiveness in accurately detecting SPAs. This is characterized by their high true positive rates and low false negatives. In contrast, the RNN, despite being useful, shows lagging performance due to higher misclassifications. These insights are vital for ongoing adjustments and optimization, aiming to enhance the reliability and efficiency of SPAs detection systems in cybersecurity applications. This comparative analysis underscores the importance of selecting the right model architecture to address the specific challenges of SPAs detection.

The Table 5 details the architecture of various sequential and hierarchal models used in SPAs detection, emphasizing the configuration and complexity of each. The table includes models like RNN, LSTM, BiLSTM LSTM, GRU, and CNN, each outlined with layer types, output shapes, parameter counts, and total parameters, highlighting the scale and intricacies of their design.

The RNN is relatively straightforward with fewer trainable parameters compared to others, indicating a simpler model structure that might impact its ability to capture complex patterns in data. In contrast, the LSTM model includes multiple layers such as embedding, LSTM layers, and dense layers, culminating in a significant number of trainable parameters which enhance its ability to learn from large and complex datasets effectively.

The BiLSTM doubles the parameter count of the LSTM by processing data in both forward and backward directions, offering a more nuanced understanding of input sequences. This is advantageous for tasks like email classification where contextual relationships in text can be pivotal.

The GRU model simplifies the gating mechanisms found in LSTMs while still maintaining a considerable number of parameters, allowing it to perform efficiently with less computational overhead. Meanwhile, the CNN uses one dimensional convolutional layer to capture spatial dependencies and patterns in data, which can be crucial for identifying textual features in email data. The detail configurations of one dimensional CNN are given below those produces optimized results:

Input Layer: Embedding

• Input Dimension: The input to the network is a sequence of integers (tokens), with each sequence having a maximum length of 150 (defined by max_len).

• Output Dimension: The embedding layer transforms each token into a 50-dimensional vector. Hence, the output dimension from the Embedding layer is (150, 50) for each sample, where 150 is the sequence length and 50 is the embedding size.

• Parameters: The number of parameters in the Embedding layer is the product of the number of unique tokens (len(tk.word_index) + 1) and the output dimension (50).

Convolutional Layer: Conv1D

• Input Dimension: Accepts the output from the Embedding layer, which is (150, 50).

• Kernel Size: The convolution operates using a kernel of size 3. This means it looks at 3 consecutive elements in the input data at a time.

• Filters: The layer uses 64 filters, meaning it will produce 64 different feature maps.

• Output Dimension: Each filter produces an output of size 148 (assuming ‘valid’ padding where no padding is applied). Thus, the output dimension of this layer is (148, 64).

• Parameters: Each filter has parameters for each element in the kernel for each input channel (depth). Here, each filter has 3 × 50 parameters, and there are 64 such filters, resulting in 3 × 50 × 64 = 9600 parameters.

Pooling Layer: GlobalMaxPooling1D

• Input Dimension: Accepts the output from the Conv1D layer, which is (148, 64).

• Output Dimension: This layer performs global max pooling over the entire length of each feature map, reducing the dimension to just the number of feature maps, i.e., (64).

Dense Layer

• Input Dimension: Accepts the output from the GlobalMaxPooling1D layer, which is (64).

• Units: 128 neurons in this layer.

• Output Dimension: (128).

• Parameters: Each neuron in this layer is connected to every input. Hence, the total parameters are 64 × 128 + 128 (for biases) = 8320.

Dropout Layer

• Purpose: Randomly sets input units to 0 at each step during training time, which helps to prevent overfitting. Dropout rate is 0.5.

• Input/Output Dimension: Does not alter the dimension, so it remains (128).

Output Dense Layer

• Input Dimension: (128).

• Units: 1 neuron (for binary classification).

• Activation: sigmoid to output probabilities.

• Output Dimension: (1).

• Parameters: 128 × 1 + 1 (for bias) = 129.

These models’ configurations suggest a deliberate design choice to optimize learning capabilities and computational efficiency. The detailed breakdown of each model’s architecture provides insights into how sequential and hierarchal models can be effectively applied to the problem of SPAs detection, leveraging complex structures to achieve high accuracy and robust performance in real-world applications. Each model’s setup is tailored to balance between depth of learning and operational demands, ensuring they can adapt and respond to the evolving tactics employed in SPAs.

4.3.5 Highlighting the Innovation and Contribution of the Proposed Model

The CNN model represents a significant innovation in the field of SPAs detection. This model stands out due to its complex structure that includes multiple layers such as convolutional layers, pooling layers, and dense layers, each contributing to a highly refined processing capability. The convolutional layers effectively capture spatial and temporal dependencies in email text data, allowing for the detection of nuanced patterns that simpler models might miss. The inclusion of global max pooling and multiple dense layers further enhances the model’s ability to consolidate learned features into precise predictions. This sophisticated architecture not only improves the accuracy of SPAs detection but also showcases the model’s ability to handle large-scale data, adapting to new threats as they evolve. This makes the CNN model a pivotal development in cybersecurity measures against SPAs, highlighting its potential to significantly reduce the risk of email-based security breaches.

Table 6 provides an overview of comparative analysis of various ML models for detecting SPAs reveals significant performance disparities among the classifiers. The MLP stands out with the highest accuracy at 98.29%, proving exceptionally capable in complex phishing scenarios. In contrast, AdaBoost, despite its robustness, shows the lowest accuracy at 91.05%. This study aligns with findings from recent research, such as Tesfom et al. [41], where NB markedly underperformed with a 66.0% accuracy rate. Meanwhile, LR and XGBoost demonstrated strong capabilities with accuracies of 96.3% and 97.27%, respectively. Notably, RF topped other models with a 97.98% accuracy, underscoring its effectiveness in phishing detection. This variance underscores the critical importance of selecting the right model based on the specific requirements and complexities of phishing detection tasks.

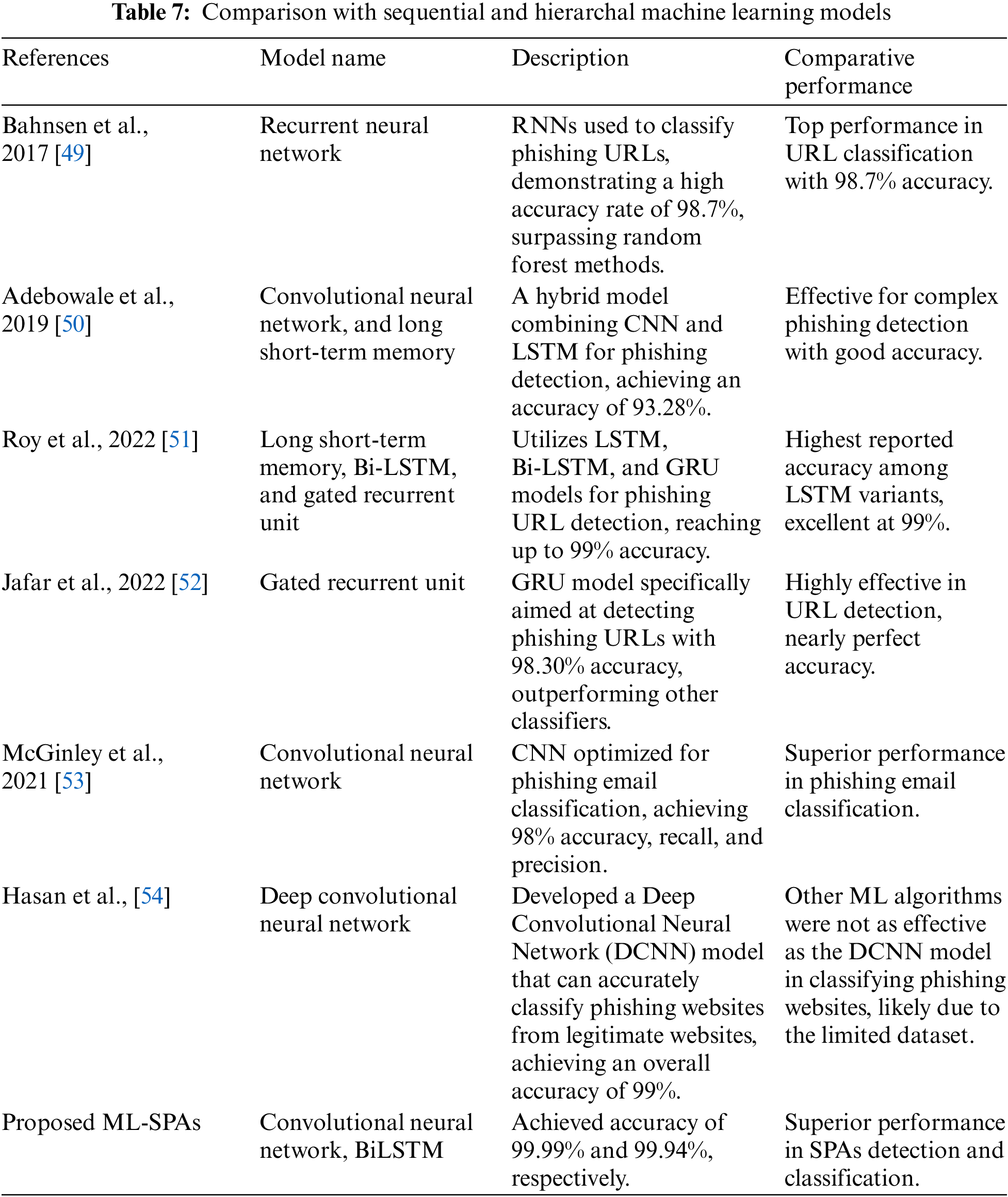

Table 7 presents the analysis of various sequential and hierarchical models for SPAs detection demonstrates considerable variability in performance, highlighting the specialized capabilities of each model. The BiLSTM model excels, achieving a nearly flawless accuracy of 99.94% and a validation accuracy of 97.81%, showcasing its profound efficiency in handling dynamic and complex phishing scenarios. Similarly, the CNN model also performs impressively, registering a validation accuracy of 97.95%. This analysis underscores the effectiveness of sophisticated neural architectures in SPA detection, with both BiLSTM and CNN providing highly robust solutions. Additional models like RNN, GRU, and the hybrid CNN-LSTM further reinforce the potential of hierarchal models in enhancing cybersecurity measures, with their respective high Accuracy rates demonstrating strong suitability for SPAs detection tasks, as evidenced in the performance metrics reported across recent studies.

The comparisons drawn with both single and multi-document models, including HDSG, GRETEL, and SgSum, underscore proposed model’s enhanced capabilities in both thematic depth and structural coherence. The proposed model’s architecture leverages advanced neural network techniques to dynamically adapt to the intricacies of the text, setting new standards in extractive summarization. This place proposed research at the forefront, pioneering next-generation summarization solutions that effectively address both the granularity of content and the coherence of summaries.

6 Conclusion, Limitations and Future Work

This study has demonstrated the effectiveness of various traditional, sequential, and hierarchical ML models in detecting SPAs with high accuracy. Among the models evaluated, BiLSTM and CNN exhibited outstanding performance, achieving near-perfect accuracy rates 99.99%. The application of these advanced neural network architectures substantially improves the detection and mitigation of phishing threats in healthcare environments, proving vital for protecting sensitive healthcare data from sophisticated cyber-attacks. This highlights the importance of adopting advanced ML techniques to enhance cybersecurity in critical sectors like healthcare.

Despite the promising results, this study has limitations. The primary constraint is the dependency on large and diverse datasets for training the models, which might not be readily available or could be biased towards specific types of phishing attacks.

Future research will focus on addressing this limitation by exploring methods to improve model transparency. Efforts will also be made to augment datasets with more varied and complex phishing scenarios to ensure robustness across different attack vectors. Furthermore, integrating these models into real-time detection systems and assessing their performance in live environments will be crucial to validate their practical applicability and efficiency in real-world settings.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to my institute who supported me throughout this work.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under Grant Number (DGSSR-2023-02-02513).

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study is publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. S. S. Bhuyan et al., “Transforming healthcare cybersecurity from reactive to proactive: Current status and future recommendations,” J. Med. Syst., vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 1–9, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10916-019-1507-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. D. Bera, O. Ogbanufe, and D. J. Kim, “Towards a thematic dimensional framework of online fraud: An exploration of fraudulent email attack tactics and intentions,” Decis. Support Syst., vol. 171, 2023, Art. no. 113977. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2023.113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. F. Ahmad, A. Kanta, S. Shiaeles, A. Naeem, Z. Khalid and K. Mahboob, “Enhancing ATM security management in the post-quantum era with quantum key distribution,” in 2024 IEEE Int. Conf. Cyber Secur. Resil., 2024. [Google Scholar]

4. M. I. Malik, A. Ibrahim, P. Hannay, and L. F. Sikos, “Developing resilient cyber-physical systems: A review of state-of-the-art malware detection approaches, gaps, and future directions,” Computers, vol. 12, no. 4, 2023, Art. no. 79. doi: 10.3390/computers12040079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. S. Shahzadi et al., “Machine learning empowered security management and quality of service provision in SDN-NFV environment,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 2723–2749, 2020. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2021.014594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. K. M. Mohi Uddin, N. Biswas, S. T. Rikta, S. K. Dey, and A. Qazi, “XML-LightGBMDroid: A self-driven interactive mobile application utilizing explainable machine learning for breast cancer diagnosis,” Eng. Rep., vol. 5, no. 11, 2023, Art. no. e12666. doi: 10.1002/eng2.12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. C. Catal, G. Giray, B. Tekinerdogan, S. Kumar, and S. Shukla, “Applications of deep learning for phishing detection: A systematic literature review,” Knowl. Inf. Syst., vol. 64, no. 6, pp. 1457–1500, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10115-022-01672-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. H. Riggs et al., “Impact, vulnerabilities, and mitigation strategies for cyber-secure critical infrastructure,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 8, 2023, Art. no. 4060. doi: 10.3390/s23084060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. M. Hasal, J. Nowaková, K. Ahmed Saghair, H. Abdulla, V. Snášel and L. Ogiela, “Chatbots: Security, privacy, data protection, and social aspects,” Concurr. Comput., vol. 33, no. 19, 2021, Art. no. e6426. doi: 10.1002/cpe.6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. S. Samtani, M. Abate, V. Benjamin, and W. Li, “Cybersecurity as an industry: A cyber threat intelligence perspective,” in Palgr. Handbook Int. Cybercrim. Cyberdevian., T. Holt and A. Bossler, Eds, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, pp. 135–154. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78440-3_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. M. Moor et al., “Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence,” Nature, vol. 616, no. 7956, pp. 259–265, 2023. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. W. Priestman, T. Anstis, I. G. Sebire, S. Sridharan, and N. J. Sebire, “Phishing in healthcare organisations: Threats, mitigation and approaches,” BMJ Health Care Inform., vol. 26, no. 1, 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2019-100031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. K. E. Henry et al., “Human-machine teaming is key to AI adoption: Clinicians’ experiences with a deployed machine learning system,” npj Dig. Med., vol. 5, no. 1, 2022, Art. no. 97. doi: 10.1038/s41746-022-00597-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. R. Alabdan, “Phishing attacks survey: Types, vectors, and technical approaches,” Future Internet, vol. 12, no. 10, 2020, Art. no. 168. doi: 10.3390/fi12100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. C. Li, M. Dong, X. Xin, J. Li, X. -B. Chen and K. Ota, “Efficient privacy-preserving in IoMT with blockchain and lightweight secret sharing,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 24, pp. 22051–22064, 2023. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3296595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. T. Xu, K. Singh, and P. Rajivan, “Personalized persuasion: Quantifying susceptibility to information exploitation in spear-phishing attacks,” Appl. Ergon., vol. 108, 2023, Art. no. 103908. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. K. Sushma, C. Viji, N. Rajkumar, J. Ravi, M. Stalin and H. Najmusher, “Healthcare 4.0: A review of phishing attacks in cyber security,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 230, no. 10, pp. 874–878, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2023.12.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. F. Rizzoni, S. Magalini, A. Casaroli, P. Mari, M. Dixon and L. Coventry, “Phishing simulation exercise in a large hospital: A case study,” Digit. Health, vol. 8, 2022, Art. no. 20552076221081716. doi: 10.1177/20552076221081716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. A. M. Hegde, S. B. Kumar, R. Bhuvantej, R. Vyshak, and V. Sarasvathi, “Spear phishing using machine learning,” in Int. Conf. Adv. Comput. Data Sci., 2023, pp. 529–542. [Google Scholar]

20. M. Rege and R. B. K. Mbah, “Machine learning for cyber defense and attack,” in The Seventh Int. Conf. Data Anal., 2018, pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

21. Y. -H. Chen and J. -L. Chen, “Machine learning mechanisms for cyber-phishing attack,” IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst., vol. 102, pp. 878–887, 2019. [Google Scholar]

22. N. Alshammari et al., “Security monitoring and management for the network services in the orchestration of SDN-NFV environment using machine learning techniques,” Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng., vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 363–394, 2024. doi: 10.32604/csse.2023.040721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. C. Yan, X. Han, Y. Zhu, D. Du, Z. Lu and Y. Liu, “Phishing behavior detection on different blockchains via adversarial domain adaptation,” Cybersecurity, vol. 7, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 45. doi: 10.1186/s42400-024-00237-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. S. P. Ripa, F. Islam, and M. Arifuzzaman, “The emergence threat of phishing attack and the detection techniques using machine learning models,” in 2021 Int. Conf. Automat., Control Mech. Indus. 4.0 (ACMI), 2021, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

25. X. Ding, B. Liu, Z. Jiang, Q. Wang, and L. Xin, “Spear phishing emails detection based on machine learning,” in 2021 IEEE 24th Int. Conf. Comput. Support. Cooperat. Work Des. (CSCWD), Dalian, China, 2021, pp. 354–359. doi: 10.1109/CSCWD49262.2021.9437758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. B. Espinoza, J. Simba, W. Fuertes, E. Benavides, R. Andrade and T. Toulkeridis, “Phishing attack detection: A solution based on the typical machine learning modeling cycle,” in 2019 Int. Conf. Computat. Sci. Comput. Intell. (CSCI), 2019, pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

27. E. N. Crothers, N. Japkowicz, and H. L. Viktor, “Machine-generated text: A comprehensive survey of threat models and detection methods,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 70977–71002, 2023. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3294090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. S. Smadi, N. Aslam, and L. Zhang, “Detection of online phishing email using dynamic evolving neural network based on reinforcement learning,” Decis. Support Syst., vol. 107, pp. 88–102, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2018.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. N. Stevanović, “Character and word embeddings for phishing email detection,” Comput. Inform., vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 1337–1357, 2022. doi: 10.31577/cai_2022_5_1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. N. Moradpoor, B. Clavie, and B. Buchanan, “Employing machine learning techniques for detection and classification of phishing emails,” in 2017 Comput. Conf., 2017, pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar]

31. M. Zhao, B. An, and C. Kiekintveld, “An initial study on personalized filtering thresholds in defending sequential spear phishing attacks,” in Proc. 2015 IJCAI Workshop Behav., Econ. Computat. Intell. Secur., 2015, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

32. E. A. Aldakheel, M. Zakariah, G. A. Gashgari, F. A. Almarshad, and A. I. Alzahrani, “A deep learning-based innovative technique for phishing detection in modern security with uniform resource locators,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 9, 2023, Art. no. 4403. doi: 10.3390/s23094403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. R. Alotaibi, I. Al-Turaiki, and F. Alakeel, “Mitigating email phishing attacks using convolutional neural networks,” in 2020 3rd Int. Conf. Comput. App. Inf. Secur. (ICCAIS), 2020, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

34. N. Altwaijry, I. Al-Turaiki, R. Alotaibi, and F. Alakeel, “Advancing phishing email detection: A comparative study of deep learning models,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 7, 2024, Art. no. 2077. doi: 10.3390/s24072077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. D. Samanta, S. H. Islam, N. Chilamkurti, and M. Hammoudeh, Data Analytics, Computational Statistics, and Operations Research for Engineers: Methodologies and Applications, 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, 2022, pp. 203–234. doi: 10.1201/9781003152392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. M. M. Ud Din et al., “InteliRank: A four-pronged agent for the intelligent ranking of cloud services based on end-users’ feedback,” Sensors, vol. 22, 2022, Art. no. 4627. [Google Scholar]

37. M. Shabbir, F. Ahmad, A. Shabbir, and S. A. Alanazi, “Cognitively managed multi-level authentication for security using fuzzy logic based quantum key distribution,” J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 34, pp. 1468–1485, 2022. [Google Scholar]

38. E. Frumento, “Cybersecurity and the evolutions of healthcare: Challenges and threats behind its evolution,” M_Health Current Future App., pp. 35–69, 2019. [Google Scholar]

39. S. Zhuo, R. Biddle, Y. S. Koh, D. Lottridge, and G. Russello, “SoK: Human-centered phishing susceptibility,” ACM Trans. Priv. Secur., vol. 26, pp. 1–27, 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. C. Subhadeep, “Phishing email detection,” 2023. Accesed: Jul. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/phishingemails/data [Google Scholar]

41. B. Tesfom, F. Belay, S. Daniel, R. Salem, and S. Otoum, “Phishing detection using deep learning and machine learning algorithms: Comparative analysis,” in 2023 IEEE Int. Conf. Depend., Autonomic Secur. Comput., Int. Conf. Pervas. Intell. Comput., Int. Conf. Cloud Big Data Comput., Int. Conf. Cyber Sci. Technol. Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech), 2023, pp. 684–689. [Google Scholar]

42. S. Mittal, R. Agarwal, M. L. Saini, and A. Kumar, “A logistic regression approach for detecting phishing websites,” in 2023 Int. Conf. Adv. Comput., Commun. Inf. Technol. (ICAICCIT), 2023, pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

43. S. R. Abdul Samad et al., “Analysis of the performance impact of fine-tuned machine learning model for phishing URL detection,” Electronics, vol. 12, 2023, Art. no. 1642. [Google Scholar]

44. H. Musa, A. Gital, F. U. Zambuk, A. Umar, A. Umar and J. Waziri, “A comparative analysis of phishing website detection using XGBOOST algorithm,” J. Theoret. Appl. Informat. Technol., vol. 97, pp. 1434–1443, 2019. [Google Scholar]

45. A. A. Fazal and M. Daud, “Detecting phishing websites using Decision Trees: A machine learning approach,” Int. J. Electron. Crime Invest., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 73–79, 2023. [Google Scholar]

46. M. F. Ab Razak, M. I. Jaya, F. Ernawan, A. Firdaus, and F. A. Nugroho, “Comparative analysis of machine learning classifiers for phishing detection,” in 2022 6th Int. Conf. Inf. Computat. Sci. (ICICoS), 2022, pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar]

47. A. Subasi and E. Kremic, “Comparison of adaboost with multiboosting for phishing website detection,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 168, no. 2, pp. 272–278, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2020.02.251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. P. F. Akinwale and H. Jahankhani, “Detection and binary classification of spear-phishing emails in organizations using a hybrid machine learning approach,” in Artificial Intelligence in Cyber Security: Impact and Implications. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, T. Holt and A. Bossler, Eds, Cham: Springer, 2022, pp. 215–252. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-88040-8_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. A. C. Bahnsen, E. C. Bohorquez, S. Villegas, J. Vargas, and F. A. González, “Classifying phishing URLs using recurrent neural networks,” in 2017 APWG Symp. Electron. Crime Res. (eCrime), 2017, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

50. M. A. Adebowale, K. T. Lwin, and M. A. Hossain, “Deep learning with convolutional neural network and long short-term memory for phishing detection,” in 2019 13th Int. Conf. Softw., Knowl., Inform. Manag. Appl. (SKIMA), pp. 1–8, 2019. doi: 10.1109/SKIMA47702.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. S. S. Roy, A. I. Awad, L. A. Amare, M. T. Erkihun, and M. Anas, “Multimodel phishing URL detection using LSTM, bidirectional LSTM, and GRU models,” Future Internet, vol. 14, no. 11, 2022, Art. no. 340. doi: 10.3390/fi14110340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. M. T. Jafar, M. Al-Fawa’reh, M. Barhoush, and M. H. Alshira’H, “Enhancеd analysis approach to detect phishing attacks during COVID-19 crisis,” Cybern. Inf. Technol., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 60–76, 2022. doi: 10.2478/cait-2022-0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. C. McGinley and S. A. S. Monroy, “Convolutional neural network optimization for phishing email classification,” in 2021 IEEE Int. Conf. Big Data (Big Data), 2021, pp. 5609–5613. [Google Scholar]

54. K. Z. Hasan, M. Z. Hasan, and N. Zahan, “Automated prediction of phishing websites using deep convolutional neural network,” in 2019 Int. Conf. Comput., Commun., Chem., Mater. Electron. Eng. (IC4ME2), 2019, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools